Introduction

Dementia, a progressive and incurable disease, has become a critical and rapidly growing public health concern, impacting developed and developing countries (Ferri et al. Reference Ferri, Prince and Brayne2005). For patients in the advanced stages of dementia (Alzheimer’s disease [AD]), the final year of life is marked by persistent and severe disability. A dementia diagnosis is a significant predictor of reduced survival, with a median survival ranging from 8.7 to 10.7 years (Dewey and Saz Reference Dewey and Saz2001; Taudorf et al. Reference Taudorf, Nørgaard and Waldemar2021). In patients with end-stage dementia, the median survival is reduced to 1.3–5.5 years (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Hsu and Chou2018; Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Teno and Kiely2009). Because these patients are often unable to communicate their preferences for end-of-life care, approximately 90% of such decisions are made by family caregivers (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Takemura and Chau2022; Dignam et al. Reference Dignam, Brown and Thompson2021).

Issuing a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order involves ethical, medical, and personal factors, including patient autonomy; communication between patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers; and ensuring that care aligns with the patient’s values (Luna-Meza et al. Reference Luna-Meza, Godoy-Casasbuenas and Calvache2021). In Taiwan, elderly patients with chronic illnesses sign advance directives at rates between 8.1% and 40.2%, which are much lower than the 94.9% among patients with cancer (Shih et al. Reference Shih, Chang and Lin2018). Non-cancer patients are also more likely to receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or respiratory support during their final hospitalization, reducing their chances of receiving palliative care (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Lien and Tsai2024a).

The inability to predict disease progression (Kuehlmeyer et al. Reference Kuehlmeyer, Borasio and Jox2012), combined with the patient’s inability to express their wishes (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Takemura and Chau2022), decision-making pressures, moral conflicts, and lack of professional support (Pagani et al. Reference Pagani, Giovannetti and Covelli2014; Symmons et al. Reference Symmons, Ryan and Aoun2023), often leads to patients with AD receiving unnecessary emergency treatments at the end of life. Studies have revealed that family caregivers’ medical decisions are often accompanied by conflict, regret, and emotional distress, significantly increasing their stress (Hickman et al. Reference Hickman, Daly and Lee2012; Wendler and Rid Reference Wendler and Rid2011).

Although many studies have explored family caregivers’ DNR decision-making, most have focused on patients with cancer (Al-Shahri et al. Reference Al-Shahri, Sroor and Ghareeb2024), families already receiving palliative care (Chiang et al. Reference Chiang, Chang and Fan2021), and decisions made before the patient’s death (Tseng et al. Reference Tseng, Huang and Hsu2018).

In Taiwan, advance care planning (ACP) for patients with dementia has gained increasing attention, particularly after the enactment of legislation promoting patient autonomy. Nevertheless, effective engagement in ACP remains limited due to the progressive cognitive decline associated with dementia, which often impairs patients’ decision-making capacity (Fazel et al. Reference Fazel, Hope and Jacoby1999). Additional barriers include avoidance of end-of-life discussions, prioritization of immediate crises, difficulty accepting future deterioration, cultural taboos surrounding death, insufficient knowledge of ACP and treatment options, and feelings of guilt among surrogates, who may perceive refusal of treatment as abandonment (Chan and Woo Reference Chan and Woo2025). As a result, family caregivers are frequently required to make urgent end-of-life decisions, such as DNR orders, without clear knowledge of the patient’s preferences (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Takemura and Chau2022; Dignam et al. Reference Dignam, Brown and Thompson2021; Kuehlmeyer et al. Reference Kuehlmeyer, Borasio and Jox2012). These challenges highlight the need to understand caregivers’ decision-making experiences to inform culturally sensitive approaches that promote timely ACP discussions and improve palliative care planning in dementia care. This study therefore explored the experiences and challenges faced by bereaved family caregivers during the DNR decision-making process, aiming to improve the quality of palliative care provided to patients with AD and their families.

Methods

Research design

A descriptive exploratory qualitative study was conducted using face-to-face semi-structured interviews to explore the decision-making experiences of caregivers of patients with AD regarding DNR orders for end-of-life care. Grounded in pragmatism, this study focused on clearly defined research questions and practical outcome-oriented processes, incorporating multiple perspectives (Morgan Reference Morgan2014). A qualitative approach was adopted to explore the complex, emotionally sensitive, and culturally influenced nature of DNR decision-making among caregivers. This methodology allows for in-depth understanding of subjective experiences that are not easily captured by quantitative tools (Denzin and Lincoln Reference Denzin and Lincoln2011). An exploratory-descriptive design was chosen for its flexibility and suitability in studying under-researched phenomena without imposing rigid theoretical assumptions (Hunter et al. Reference Hunter, McCallum and Howes2019). Semi-structured interviews facilitated open dialogue while enabling the emergence of unanticipated themes. Data were analyzed inductively using thematic coding to ensure that interpretations closely reflected participants’ lived experiences.

Participants and settings

The study was conducted in central Taiwan using purposive sampling to recruit participants. Cases were referred by directors or case managers from three long-term care facilities: 2 in urban areas and 1 in a rural area. This approach ensured coverage of patient populations from different regions. The participant inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) individuals serving as the primary caregiver or decision-maker in the last 6 months of patients diagnosed with dementia who were bedridden for at least a year before death; (2) individuals aged >20 years who were able to communicate effectively and experienced in making end-of-life decisions. These criteria ensured participants had extensive caregiving experience and were directly engaged in the DNR decision-making process. The 1-year immobility threshold was used to reflect advanced dementia and high caregiving burden, increasing the likelihood of encountering critical care decisions. The 6-month post-bereavement window was selected to reduce recall bias while allowing sufficient time for emotional reflection.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) caregivers of patients with terminal cancer, those who had received palliative care, or those with an “advance decision”; (2) caregivers who could not communicate or those diagnosed with mental illness or cognitive impairment. Cases with advance decisions were excluded to focus on participants who directly experienced the dilemmas of real-time DNR decisions. In such contexts, caregivers serve more as patient advocates than as decision-makers, fundamentally changing the nature of their involvement (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Lu and Liu2020; Symmons et al. Reference Symmons, Ryan and Aoun2023).

Ethics approval and consent

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fengyuan Hospital (IRB No.: 112031). All participants provided written informed consent, and data were anonymized. Completed documents were securely stored, and audio recordings and electronic files were password-protected on the researcher’s computer.

Data collection

Data were collected from March 2022 to July 2023. The research team comprised experienced palliative care, gerontology, and long-term care and qualitative research experts (Ph.D.), with the interviews conducted by a registered nurse who has 16 years of experience in long-term care. Five team meetings were held to design strategies, refine the interview guide, and support participant engagement. The interviewer completed a 36-hour qualitative research course and passed the examination. Under the supervision of the research team, formal data collection began only after confirming the interviewer’s proficiency in communication skills, interview techniques, and self-reflection. Additionally, semi-structured pilot interviews were conducted to test the research questions. The participants’ informed consent and sociodemographic data were collected, followed by semi-structured interviews based on a pretested guide (Appendix 1). The interviews, conducted in the participants’ homes, were recorded and lasted for approximately 30–40 min. The interviewer also kept observational notes and reflections.

Data analysis

Three female researchers (H.-H.S., C.-Y.L., and K.-C.L.) coded the data using content analysis. Rigor was ensured by coding based on open-ended questions and participant-identified key areas and by applying Lincoln and Guba’s qualitative research criteria (Lincoln Reference Lincoln1985). Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim on the interview day, followed by repeated checks for accuracy. Transcripts were reviewed multiple times, with notes taken to capture categories, and significant words were marked for preliminary analysis. Themes were identified using an inductive process that examined meanings, similarities, and relationships. Although 22 interviews were initially planned, data saturation was achieved after 46 interviews, following Francis et al.’s (Reference Francis, Johnston and Robertson2010) method.

The interviewer had no formal relationship with the participants but had previously provided care to these patients for approximately 3–10 years and was well-acquainted with the subjects. To ensure content accuracy, interview transcripts may be returned to participants for their feedback and/or corrections. Observational notes and reflections were used to verify the data analysis results, thereby enhancing credibility. The strict inclusion/exclusion criteria ensured homogeneity of data, while objectivity during data collection and analysis improved transferability. A research log was used to document the auditing methods and decisions. Twelve discussions were held to ensure consistency in evaluating the process and outcomes. Data were repeatedly reviewed to ensure accuracy and improve dependability. Reflective thinking helped identify and minimize bias, and detailed records ensured confirmability. This study was conducted according to the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research guidelines (Tong et al. Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007) (Appendix 2).

Results

Participants

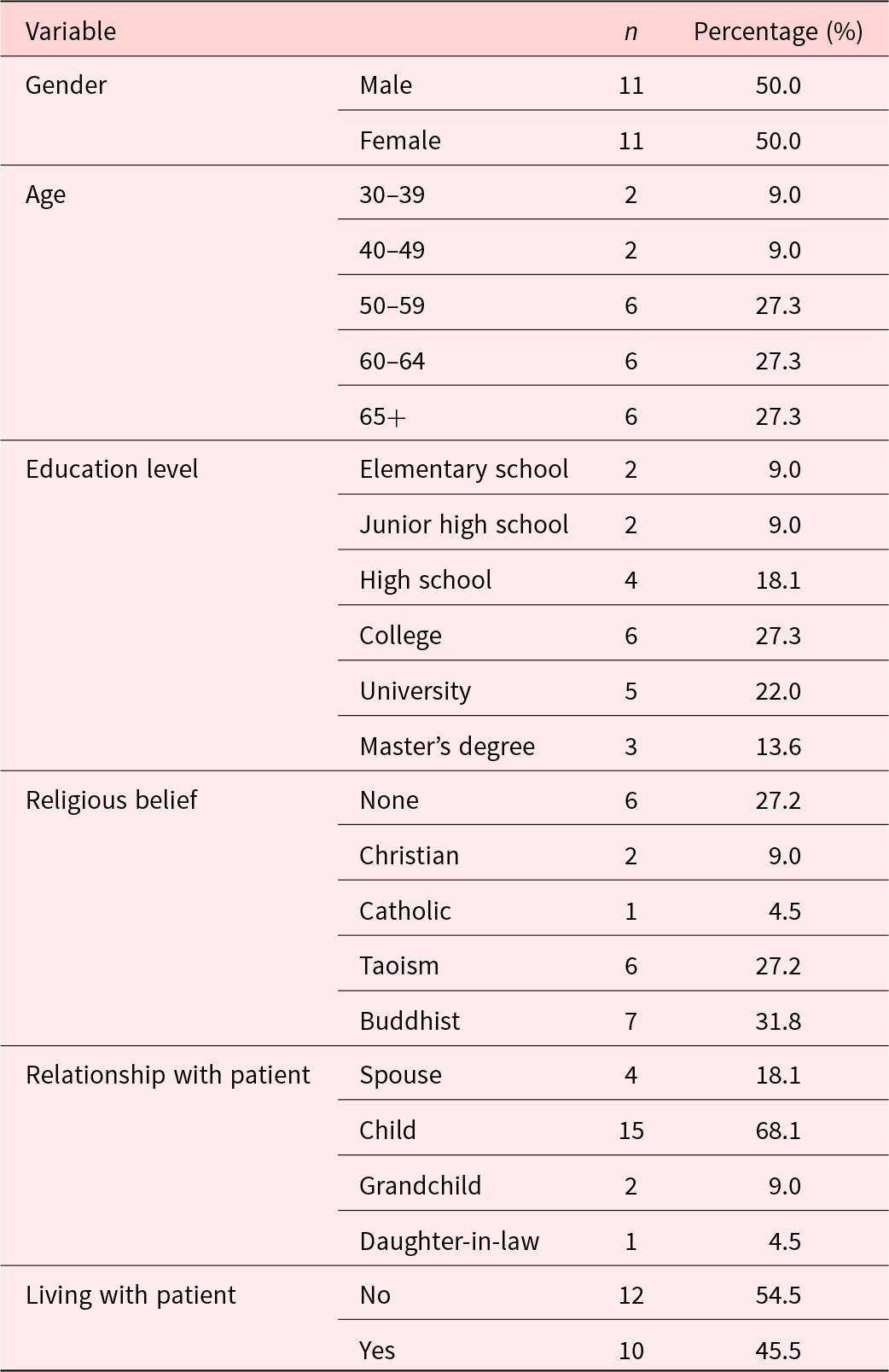

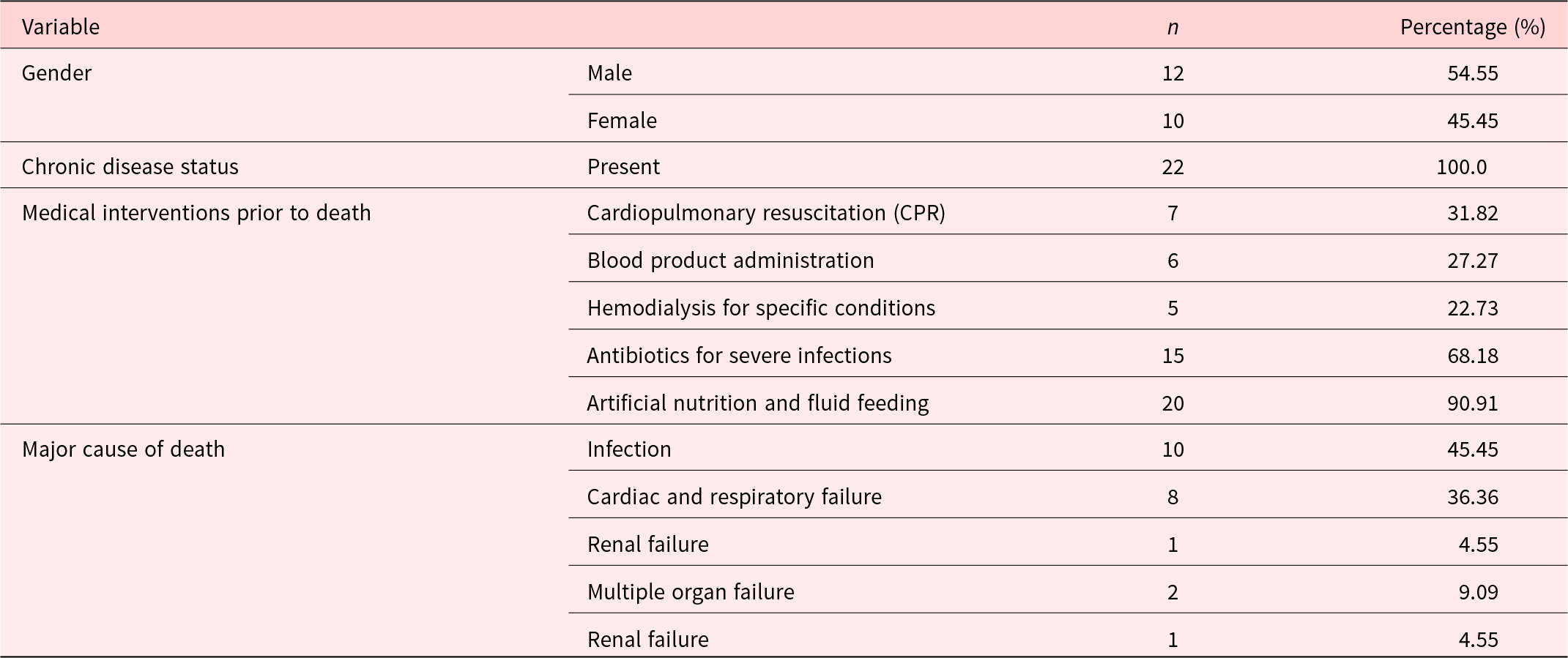

The study included 24 participants; however, 2 declined to participate in the interviews, resulting in a final sample of 22 participants. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the caregivers. The participants had an average age of 50.22 years (range: 30–75 years); 68.1% were the children of the patient, 77.2% served as primary decision-makers, and 45.5% lived with the patient. Most of the deceased patients were male, with 31.82% receiving CPR, 68.1% receiving antibiotics, and 90.91% receiving artificial nutrition at the end of life. The primary causes of death were infection and heart failure (Table 2).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of caregivers (N = 22)

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of patients (N = 22)

Main findings

Themes

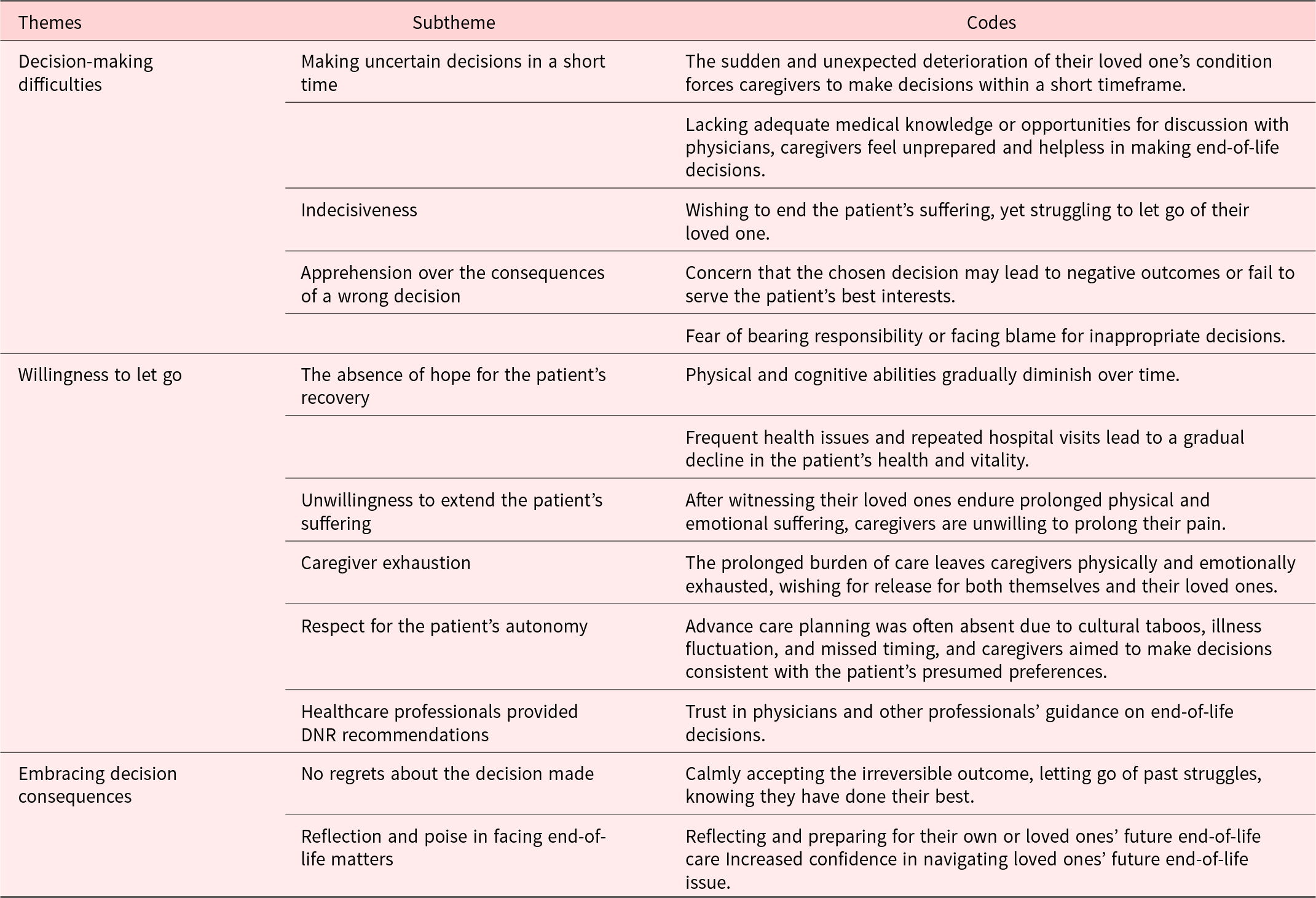

From the interviews, three major themes emerged regarding DNR decision-making: “decision-making difficulties,” “willingness to let go,” and “embracing the consequences of the decision” (Table 3)

Table 3. Theme, subtheme and codes obtained from the family caregivers’ experiences

Theme 1: Decision-making difficulties

When their loved ones faced life-and-death situations, the caregivers experienced significant pressure to make decisions quickly, often feeling unprepared, indecisive, and anxious about making the wrong choices. With repeated hospitalizations and unexpected deterioration, the caregivers were required to make urgent medical decisions within a limited timeframe. Lacking sufficient medical knowledge and time for thorough discussions with healthcare professionals, they struggled with decision-making, feeling hesitant and concerned about mistakes while fearing accountability from other family members.

Making uncertain decisions in a short time

Although the patient’s condition was critical during each hospitalization, similar DNR decision-making situations had previously occurred, with healthcare professionals offering brief explanations. However, the caregivers struggled to understand medical terminology and feared that asking frequent questions could disrupt the medical staff or cause displeasure. This lack of time for thorough discussions left the caregivers feeling unprepared and helpless in making end-of-life decisions. They expressed the need for physicians to explain treatments in an accessible language and provide adequate time for discussion.

“My father’s condition deteriorated so quickly that I didn’t even fully grasp what was happening. There was not enough time to talk to the doctor, and I was afraid that asking too many questions would upset him. There was no conversation—just pressure to decide quickly. So, we made the decision… but at that moment, I really didn’t know what to do. It was extremely difficult, and I wished someone could give me a clear sign.” (Male gender, age 45, son)

“In the last six months of my mom’s life, she was in and out of the hospital a lot. Each time, she managed to come back home. But that final time, we thought she was doing okay. Then suddenly, the doctor wanted us to make a quick decision. We really didn’t know what was coming next. How were we supposed to handle that?” (Female gender, age 36, daughter)

Indecisiveness

The caregivers, torn between logic and emotion, struggled to let go despite not wanting their loved one to endure more suffering.

“Before he (father) passed, I had always thought I wouldn’t want him to suffer, and that when the time came, I’d let him go peacefully. But when that moment arrived, I just couldn’t let go. I couldn’t accept his passing, so when asked whether to resuscitate him, it was incredibly hard. My logic and emotions were in constant conflict.” (Female gender, age 55, daughter)

Apprehension over the consequences of a wrong decision

The caregivers feared making the wrong decision, worrying that it could shorten their loved one’s life or lead to regret. Even after a unanimous family decision, the pressure of accountability weighed heavily on the decision-maker.

“I was very worried about making the wrong decision. What if my mother could have lived longer? Did I, in a way, shorten her life? Was I responsible for her death?” (Male gender, age 56, son)

“Even though they all told me they accepted my decision, I kept wondering—why was I the one who had to sign the DNR? I still felt a lot of pressure. What if, later on, they blamed me for the decision I made? At that time, I really thought about it a lot.” (Male gender, age 56, son)

Theme 2: Willingness to let go

When recovery was no longer possible, the caregivers, exhausted by prolonged caregiving and witnessing their loved one’s suffering, found it easier to agree to a DNR, particularly when the patient’s wishes were known or healthcare professionals recommended it.

The absence of hope for the patient’s recovery

As the patient’s health declined, the caregivers recognized that recovery was impossible and believed it was better for the patient to pass peacefully rather than live without dignity.

“It’s been over six years like this, with a foreign caregiver taking care of him. He doesn’t know, and he can’t move. His body has grown thinner, shriveled. We all know as a family that living like this has no meaning.” (Male gender, age 55, son)

Unwillingness to extend the patient’s suffering

Witnessing the discomfort caused by life-sustaining interventions, such as suctioning, nasogastric tubes, tracheostomies, or oxygen therapy, the caregivers found it unbearable to see their loved ones continue to suffer.

“You know, the nasogastric tube has to be replaced every month. He kept coughing, and when they pulled it out, I saw how long it was. I can’t imagine how painful that must be. I really couldn’t bear to see him live like that.” (Female gender, age 66, spouse)

Caregiver exhaustion

Long-term caregiving left the caregivers physically and emotionally drained, making them question their ability to continue. They hoped for relief for both themselves and their loved ones.

“I’ve been caring for him for 10 years, and I’m tired, and so is he. I really hope he can pass peacefully. I’m not sure how much longer I can keep this up. I just hope we can all find relief.” (Male gender, age 66, son)

Respect for the patient’s autonomy

Participants noted the absence of ACP, which was often attributed to cognitive decline, limited awareness of disease progression, or cultural reluctance to discuss death.

In our family, talking about death is something we just don’t do. It feels like we’re cursing someone if we bring it up — like speaking bad luck. So by the time we realized we needed to talk about it (preparing for death), he could no longer express himself. His illness kept changing — sometimes he seemed better, sometimes worse. We really didn’t know when would be the right time to ask, or how to even start the conversation.” (Female gender, age 55, daughter)

Although many patients with AD could not express their end-of-life wishes, the caregivers prioritized respecting previously expressed wishes for autonomy.

“My father was hard of hearing, and it was not easy to communicate with him. I never had a discussion with him about resuscitation, so I didn’t know what he wanted. If he had told me, I think the pressure of making decisions would have been much less.” (Male gender, age 56, son)

Healthcare professionals provided DNR recommendations

The caregivers trusted healthcare professionals and were inclined to follow their recommendations regarding DNR decisions.

“The doctor said not to resuscitate her, to make her comfortable. We believed the doctor knew better than we did, as we really didn’t understand much. Of course, we followed the doctor’s advice.” (Female gender, age 66, spouse)

Theme 3: Embracing and accepting the consequences of the decision

The caregivers reflected on the outcomes of their end-of-life decisions, feeling acceptance, regardless of whether the results were positive or negative. They did not regret their choices, believing that they had done their best. Furthermore, the caregivers began considering doing similar situations in the future, expressing a desire to prepare themselves and their families for end-of-life decisions. Through this experience, they felt more confident in handling future situations.

No regrets about the decision made

Looking back, the caregivers felt a sense of relief and acceptance, having come to terms with their decision. They no longer dwelt on the struggles they faced.

“At the time of the decision, I was really torn, but once it was made, I felt the pressure lift. Since it was done and irreversible, I figured I might as well relax.” (Female gender, age 58, daughter)

Reflection and poise in facing end-of-life matters

After going through the decision-making process, the caregivers felt more prepared for their own end-of-life care and more confident in handling similar situations.

“Walking this path has been a great learning experience for me. At the very least, I now have some ideas about my own end-of-life plans.” (Female gender, age 66, spouse)

“I still have an elderly father, but next time, I’ll have the experience. I’m thinking ahead now and understanding things better, so I won’t panic.” (male gender, age 60, son)

Discussion

This study explored the experiences of family caregivers of patients with AD when making end-of-life medical decisions during critical health conditions and their impact on these individuals. Three major experiences were identified in this process: difficulty in making decisions in the moment, willingness to let go, and acceptance of the outcomes of medical decisions. Patients with AD often experience frequent hospitalizations due to acute events such as pneumonia and urinary tract infections, which are common causes of death in this population (Cao et al. Reference Cao, Wang and Li2020; Jiao et al. Reference Jiao, Li and Wu2021). Although some conditions may initially appear treatable, their rapid progression and unpredictability often force caregivers to make repeated and urgent DNR decisions under significant time pressure, complicating the end-of-life decision-making process (Kuehlmeyer et al. Reference Kuehlmeyer, Borasio and Jox2012).

Consistent with previous findings, caregivers in this study, despite anticipating the patient’s eventual death, frequently experienced indecision when making DNR choices. This indecision arose from the conflict between respecting patient autonomy, navigating moral considerations, and confronting medical realities. Caregivers often struggled to reconcile the desire to relieve suffering with the emotional burden of accepting the patient’s death (Chiang et al. Reference Chiang, Chang and Fan2021; Tsai and Lai Reference Tsai and Lai2024). The act of signing a DNR order frequently evoked complex emotions, including guilt, uncertainty, and significant decision-making pressure, even as caregivers prioritized the patient’s best interests.

Cultural factors significantly shaped DNR decision-making, a finding consistent with previous research (Chiang et al. Reference Chiang, Chang and Fan2021; Tseng et al. Reference Tseng, Huang and Hsu2018). In Taiwan’s family-centered care model, traditional Chinese norms often position the eldest son as the primary decision-maker, sometimes with greater influence than the patient’s spouse. This cultural emphasis on filial piety and obedience frequently creates ethical dilemmas for adult children, potentially leading to guilt, mutual blame, or accusations of unfilial behavior during DNR decisions. These cultural pressures occasionally influence families to pursue life-sustaining treatments due to fear or perceived moral inadequacy.

The findings further revealed that caregivers were more inclined to agree to DNR decisions when patients had no prospect of recovery, experienced prolonged suffering, or when caregivers themselves faced significant emotional and physical exhaustion. Key factors influencing these decisions included patients’ physical decline, cognitive deterioration, and poor overall prognosis (Ding et al. Reference Ding, Jin and Lan2021; Hickman et al. Reference Hickman, Daly and Lee2012). While DNR discussions were often challenging when the patient’s condition appeared stable, caregivers became more receptive as the patient approached death or when major interventions were deemed necessary (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Ho and Lin2024b; Fan and Hsieh Reference Fan and Hsieh2020).

In situations where patient recovery was deemed impossible, caregivers often perceived CPR as both physically harmful to patients and emotionally distressing for families (Chiang et al. Reference Chiang, Chang and Fan2021; Ding et al. Reference Ding, Jin and Lan2021). Witnessing prolonged patient suffering frequently led caregivers to view CPR as futile and even cruel. Consequently, the decision to forgo CPR was ethically justifiable, grounded in the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence.

This study also emphasized the substantial burden that long-term caregiving for patients with AD places on families, encompassing physical, emotional, and financial strains (Isac et al. Reference Isac, Lee and Arulappan2021). Factors such as the patient’s functional dependency, comorbidities, and cognitive decline exacerbated this burden, leading caregivers who doubted their capacity to continue providing care to favor DNR decisions. Although financial pressures were less influential among caregivers with adequate insurance, they still contributed to decision-making stress for families facing economic hardship (Ding et al. Reference Ding, Jin and Lan2021; Miljeteig et al. Reference Miljeteig, Sayeed and Jesani2009). Consistent with previous studies, many caregivers in this study, similar to findings from Taiwanese nursing homes, were unaware of their loved ones’ end-of-life preferences (Tseng et al. Reference Tseng, Huang and Hsu2018). In contrast, research from China indicated that critically ill elderly patients often explicitly communicated their wishes while cognitively intact (Ding et al. Reference Ding, Jin and Lan2021). The progressive and prolonged cognitive decline characteristic of AD likely hindered similar discussions in our cohort, contributing to greater uncertainty during decision-making.

Unlike Kuehlmeyer et al. (Reference Kuehlmeyer, Borasio and Jox2012), whose study revealed that caregivers of patients in a vegetative state often based decisions on emotions and personal interpretations rather than the patient’s prior wishes, caregivers in this study emphasized the importance of honoring the patient’s previously expressed end-of-life preferences. These caregivers believed that clear guidance would have alleviated the decisional burden. Research consistently demonstrates that advance directives enhance the alignment between caregiver decisions and patient intentions (Chuang et al. Reference Chuang, Shyu and Weng2020), and that early communication and the promotion of ACP can substantially reduce conflicts (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Lu and Liu2020; Symmons et al. Reference Symmons, Ryan and Aoun2023). Therefore, the early promotion of patient autonomy is essential, particularly for individuals facing progressive cognitive decline (Kuehlmeyer et al. Reference Kuehlmeyer, Borasio and Jox2012).

Although many caregivers felt prepared to engage in end-of-life discussions as death approached, most lacked prior experience with such conversations (Yeh et al. Reference Yeh, Newman and Main2021). This gap likely stems from the difficulty in predicting disease progression and the gradual decline characteristic of AD, which often delays the establishment of advance directives (Wen et al. Reference Wen, Chou and Hou2022). Therefore, effective, proactive guidance by healthcare professionals is critical, emphasizing the importance of initiating early discussions and fostering collaborative decision-making (Engel et al. Reference Engel, Kars and Teunissen2023; Hall et al. Reference Hall, Lugton and Spiller2019). Such communication can improve treatment adherence and strengthen patient–provider relationships (der Velden Nca et al. Reference der Velden Nca, Meijers and Han2020; DiMatteo et al. Reference DiMatteo, Giordani and Lepper2002). To better prepare caregivers for decision-making, physicians are encouraged to proactively assess overall care needs, rather than solely responding during crises (Lavrijsen et al. Reference Lavrijsen, Van Den Bosch and Koopmans2005). Following bereavement, reflecting on DNR decisions may also assist caregivers in processing their experience and mitigating lingering guilt (Kim and Kang Reference Kim and Kang2011).

Finally, after completing the decision-making process, most caregivers in this study reported accepting the outcomes, regardless of their perceived positivity or negativity. This acceptance may reflect Confucian cultural values that emphasize balance, future orientation, and tolerance for human imperfection (Yao Reference Yao2021). Caregivers expressed a sense of having done their best, which mitigated regret and fostered resilience. Moreover, consistent with findings from studies of caregivers of terminally ill patients (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Liu and Kang2024), caregivers expressed greater confidence in handling similar situations in the future and began considering end-of-life preparations for themselves and their families.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the study was limited to family caregivers in long-term care facilities in central Taiwan, limiting the generalizability of the findings and potentially missing perspectives from other regions or cultural contexts. Second, interviews conducted after the patient’s death may have been subject to recall bias, with caregivers’ memories possibly affected by time, leading to forgotten or distorted details. Furthermore, only primary caregivers or decision-makers were included, thereby excluding input from other family members, which may have resulted in an incomplete view of the family decision-making process. Despite these limitations, this study offers valuable insights into the needs of caregivers of patients with AD during end-of-life decision-making. Future research should include more diverse regions and cultures and explore the multilayered dynamics of family decision-making to better understand end-of-life processes.

Conclusion and practical recommendations

This study explored the experiences and challenges faced by family caregivers of patients with AD during end-of-life decision-making. Key factors such as emotional conflict, lack of knowledge, cultural pressures, and respect for patient wishes were identified in DNR decisions. Caregivers often had to make difficult choices quickly and showed a strong need for medical information and emotional support. This study highlighted the importance of healthcare providers taking an active role by initiating early end-of-life discussions, providing clear medical information, and supporting caregivers within a culturally sensitive framework. Caregivers expressed acceptance and relief after making decisions, highlighting the need for emotional support afterward. Therefore, the following practical recommendations are proposed:

1) Proactive support for informed decision-making: Healthcare providers should discuss medical decisions with families of patients with progressive, irreversible diseases before crises arise. Clear explanations and sufficient discussion time reduce anxiety and decision pressure and help families prioritize patient well-being.

2) Assisting against emotional conflict: Culturally sensitive counseling and psychological support can help families navigate conflicting emotions and make decisions aligned with the patient’s best interests.

3) Post-decision support: After a DNR decision, caregivers require ongoing support due to physical and emotional exhaustion. Healthcare providers can help caregivers reflect on and accept their decisions, promoting emotional healing and long-term well-being.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951525100424.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Fengyuan Hospital for granting official clearance to access the patients’ households. We also acknowledge the efforts of the long-term care case managers who obtained the initial consent and assisted the interviewer in recruiting caregivers for data collection. Our gratitude also extends to the bereaved caregivers of dementia patients who generously provided information.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: C.-Y.L., H.-H.S., and K.-C.L. Investigation: C.-Y.L. and K.-C.L. Methodology: K.-C.L., S.-H.L., and P.-C.L. Analysis and interpretation of data: C.-Y.L., H.-H.S., and K.-C.L. Supervision: K.-C.L. Writing the original draft: K.-C.L. and H.-H.S.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Science and Technology Council (MOST 111-2314-B-039-015-MY3).

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Appendix 1. Research questions

1. Can you describe what happened with your loved one’s health as they approached the end of life?

2. What treatments did your loved one receive in their final days, and what factors influenced your decision to pursue these treatments?

3. How did you feel when the doctor asked you to make a decision regarding a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order?

4. What factors facilitated or hindered your decision-making process regarding the DNR?

5. If you could revisit the moment of deciding on the DNR, would your choice remain the same?

6. What personal impact did making the DNR decision for your loved one have on you?

Appendix 2. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ): 32-item checklist