I say among my friends that Narcissus who was changed into a flower, according to the poets, was the inventor of painting.… What else can you call painting but a similar embracing with art of what is presented on the surface of the water.

There was a pool, limpid and silvery.… The boy lay down, enchanted by the quiet pool … as he drank he saw before his eyes / a form, a face, and loved with leaping heart / A hope unreal and thought the shape was real. Spellbound he saw himself, and motionless / lay like a marble statue staring down.… How often in vain he kissed the cheating pool / and in the water sank his arms to clasp.… You simple boy, why strive in vain / to catch a fleeting image? What you see is nowhere.… You see a phantom of a mirrored shape / Nothing itself; with you it came and stays / With you it too will go.…

In Leon Battista Alberti’s Della pittura of 1435–36, the Florentine architect and art theorist elaborated a paradigm for painting as a mirror reflection of the visible world.1 For this he drew on classical precedents, both Platonic and Aristotelian, in conceiving of art as mimesis, or imitatio in its Latinate form. A close cognate to ‘image’ etymologically, Alberti understood imitatio as the imitation of the visible world and the artistic means by which to do so.2 Those means comprised the methods of pictorial illusion through which to render the fiction of space and volume on the flat surface of a picture plane. Borrowing from the ancient poet Ovid as from Pliny to write the first theory of Renaissance painting, Alberti traced the mythical inauguration of this art in the reflective pool of Narcissus.3 Indeed, Alberti recast Ovid’s poetry of Metamorphoses into the historical origins of art:

I say among my friends that Narcissus who was changed into a flower, according to the poets, was the inventor of painting. Since painting is … the flower of every art, the story of Narcissus is most to the point. What else can you call painting but a similar embracing with art of what is presented on the surface of the water of the fountain?4

Thus Alberti projected the mythological origin of the imago as a mirror reflection onto the surface of Ovid’s silvered pool, ad fonte. This ‘fount’ was conceived as the source of art. In so saying, Alberti adumbrated an analogy between painting and mirroring as the foundations of a mimetic image. His analogy forms the subject of this book.

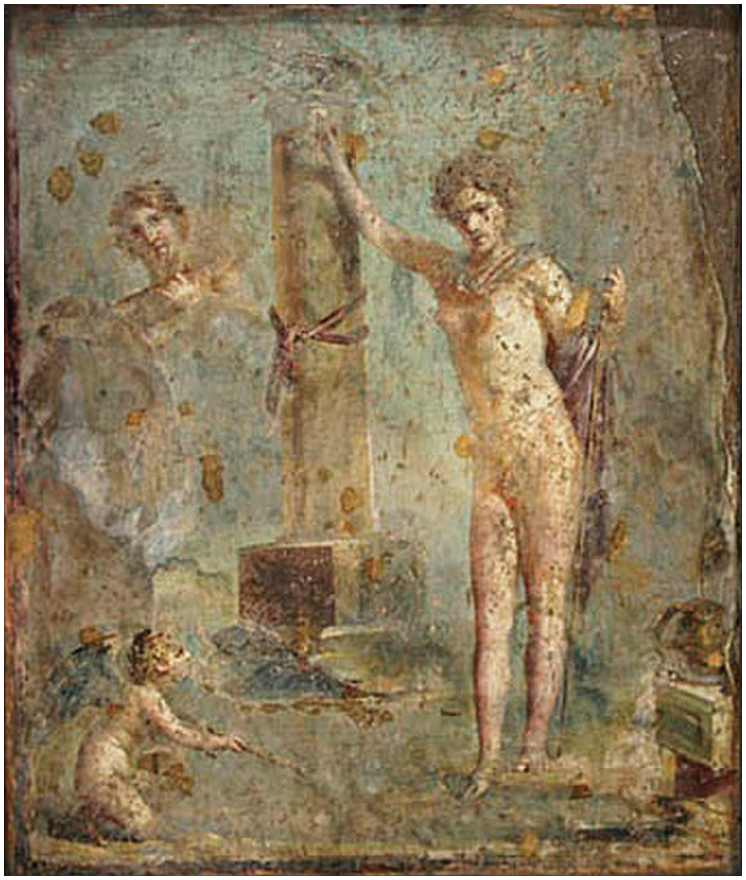

Writing from his position as humanist theorist of the arts, Alberti was heir to those cultures of classical revival patronised by the Medici that shaped a nascent Renaissance paradigm of art within a matrix of paragone, or comparison, inherited from Pliny, Horace, and Plutarch. Alberti’s entirely new conception of painting’s origins in the watery pool of Ovidian myth made art the counterpart not only to the mirror reflection but also to poetry, within the paired equivalence of the Horatian dictum, ut pictura poesis.5 In Ovid’s account, while Narcissus is transformed into a mirror reflection and so the flower of art, the woodland nymph Echo who desires him becomes the voice of poetry (Fig. 1). In a linked Latinate etymology, both are reflections, word and image conjoined, and so metaphors of love’s longing return.6

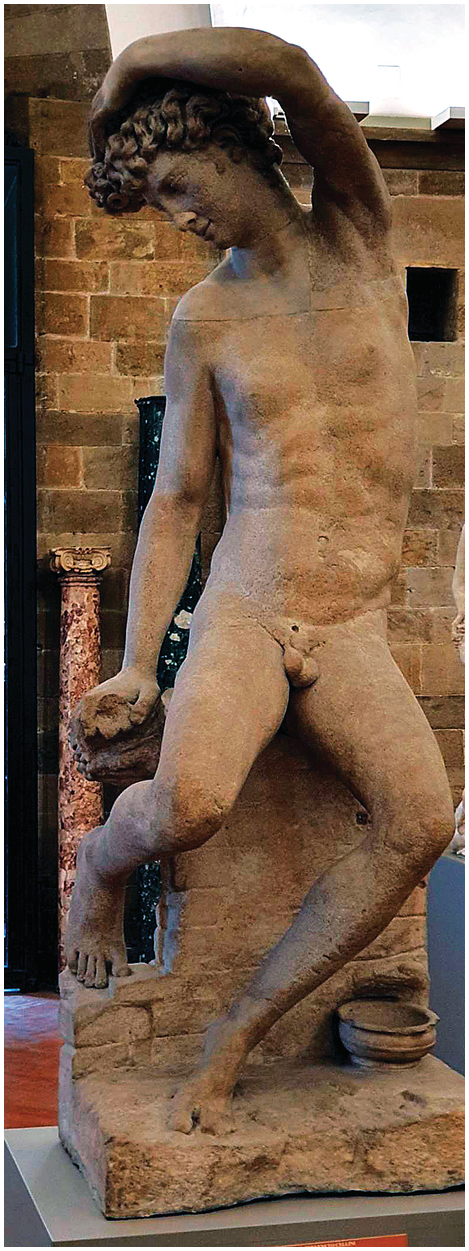

In the ancient Philostratus’ subsequent representation of the Narcissus myth in his Eikones or Imagines (1:23), each poetic ‘image’ of this mythic pool contained within it an infinite historical cascade of inset figurative imagery, like so many mirror reflections of Ovid’s verse.7 Much translated across the Renaissance, as with Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Philostratus’ Imagines was a literary art gallery that configured the (fictive) painted image as suffused with both poetic and pictorial recollection, each one a history of art within itself. In the sixteenth-century sculptor Benvenuto Cellini’s reiteration of Alberti’s specular conceptualisation of the painted image within the further context of an Ovidian paragone: ‘Painting is nothing other than, say, a tree or a man, or anything that is reflected in a fountain’s pool. The difference between sculpture and painting is great, like that between a shadow, and the thing that causes shadow to fall.’8 Alongside this Cellini sculpted his own marbled Narcissus who casts his shadow into a fountain’s pool while gazing down at his watery reflection (Fig. 2).9 The Venetian painter Paolo Pino similarly theorised painting as the formless figurations of a specular mimesis like the shadowy reflections in Ovid’s pool: ‘our art is like the effects of a mirror’.10 In both word and image, Alberti had understood art’s defining characteristic as the power to ‘make the absent seem present’, by which he meant its illusionistic capacity of imitation to render the semblance of life where there is none.11 As with the evocations of poetic language, art’s mimetic force may cause the viewer, like Ovid’s Narcissus, to love a mirrored reflection, ‘nothing itself’, such is the power of its veristic illusions.

Elsewhere in his Della pittura, Alberti described the art of painting as ‘an open window, through which I see what I want to paint’.12 This was to invoke a conceit of pictorial imitation within the optics of perspective as equivalent to vision itself. Alberti’s reflexive conception of painting as both a mirror and a window view, in his further elaboration, comprised the optical as well as the conceptual means by which to render the image as the fiction of life, like the watery reflection that Narcissus sought to embrace on the surface of the poetic pool. Alberti’s elision of the mirror-image with the window view surely derived from their shared Latin etymologies as speculum and specularia, as well as the cognate of speculation as a figure of thought. Vision, Alberti knew, had been likened to ‘a living mirror’ within classical and medieval optical theory. Similarly, the mirror was, Alberti argued, ‘the true judge’ of painting. Thus, resemblance to the mirror reflection, like Ovid’s mythic pool, was the just measure of the painter’s art.

While Alberti was theorising the art of painting under the sign of the mirror as specular mimesis (1434–36), in Bruges Jan van Eyck was painting the celebrated tondo mirror of his Arnolfini double portrait (1434) (Fig. 3). In this painting, which has come to define the inauguration of Northern Renaissance art, its inset mirror-image is the pictorial emblem of that claim. The painted reflection mirrors back the room in which it is set to show the couple within it seen from behind, the stone-mullioned window to the side, as well as a further projection of the room ‘in front’ of the picture plane. Van Eyck’s mirror represents an illusionistic fusion of painting and mirroring, exactly as Ovid had imagined, by analogy with an Albertian ‘window’ of painted spatial projection. This specular pictorialisation of the art of painting was enhanced by van Eyck’s highly refractive use of oil paint to heighten the capacity for optical reflection, through the application of glistening light-filled glazes suspended in translucent coloured oil. As in Alberti’s text, van Eyck’s lustrous mirror theorises the art of painting as a mimetic illusion like the shimmering reflection of Ovidian myth. Thus painting and mirroring were held to be commensurate forms of the Albertian ‘window view’ of art.

***

This book argues that the key pictorial development of Renaissance art was a new conceptualisation of painting as a mirror reflection of the visible world. In effect, the mirror became painting’s sign of optics as an instrument of light and its reflection, and so of all forms of visual representation. As the emblem of vision itself, the mirror became the rebus of the painter’s art. The book’s temporal frame opens with the inauguration of the perspectival ‘mirror-window’ of painting in early fifteenth-century Italian art theory. Elaborated by Alberti, the science of perspective was demonstrated by the architect Filippo Brunelleschi by means of a mirror reflection of the view through the door of the Florentine cathedral. Alongside arose the pictorialised optical mirrors of early Netherlandish oil paint initiated by van Eyck. The book then follows the specular conceptualisation of Renaissance art in the sixteenth-century rise of the easel painting as an independent work of art, in which each framed image represented in itself an Albertian ‘window view’ of mirroring mimetic illusion. It considers new Renaissance genres of art whose development was specifically bound to the mirror-image. This comprised self-portraiture, made by means of a mirror as its instrument, and the rise of the painted female nude with a mirror as the reigning pictorial emblem of High Renaissance art’s beauty. These painted inset mirror reflections have long been acknowledged to reach a ‘Baroque’ apogee in the art of Velazquez, notably in his Rokeby Venus and Las Meninas. In effect, Las Meninas draws together the long Renaissance pictorial history of the embedded mirror-image as the allegory of painting itself. The Hall of Mirrors at Versailles concludes this book’s account of the historical relationship between Renaissance painting and mirroring in its specular juxtaposition of mirrors, windows, and painting, just as van Eyck and Alberti had adumbrated. The example of Versailles, like Las Meninas, is thus the culmination of the early modern relationship between painting and mirroring that this book traces, offering in nuce its major themes. In sum, the book debates what defined Renaissance painting, in both artistic theory and art practice, to argue that its newly formulated techniques of optical illusion were conceived in relation to the mirror-image as the model of art’s visual mimesis.

While the disciplinary centre of this book concerns art-historical questions pertaining to an early modern conceptualisation of painting as specular, the range of contextualising histories within which to understand a Renaissance analogy between picturing and mirroring extends across the literatures and sciences too. Thus the book offers an interdisciplinary account of the mirror’s multiple cultural roles as an instrument and metaphor of light and vision, as of knowledge itself, within which to situate its particular address to the history of early modern art. As Hans Belting, Victor Stoichita, and Michael Fried have variously argued, this relationship between painting and mirroring is bound up with the early modern architectural development of the picture gallery, and so with the historical emergence of easel painting. As a newly independent and ‘self-aware’ kind of painting, the gallery picture is, in this analysis, now able to signify its own ontological status as ‘art’. In such a consideration, the early modern gallery painting is understood to address within itself the nature of pictorial representation as both mimesis and illusion, like Philostratus at the poetic pool of Narcissus, or Alberti’s window view. Broadly, Belting’s argument concerns the historical separation of ‘art’ from the medieval icon or cult object wrought by religious Reformation, resulting in the nascent status of the image as a work of art in its own right. Now judged in terms of its powers of mimesis and narrative or poetic invention, rather than its resemblance to an iconic prototype as the matrix of devotional efficacy, painting was newly theorised as specular. To quote from Stoichita and Fried in turn, early modernity marks the advent of ‘painting in itself’, of which mirroring was its ‘core modality’.13 As such, art now reflected on itself, in theory as in practice.14

In the title to his book, The Self-Aware Image, Stoichita further invoked the term métapeinture, or metapainting, as the subject of his enquiry. As other scholars have noted, until Stoichita’s book first appeared in 1993, ‘metapainting’ rarely entered the critical terminology of early modern art-historical analysis, if at all. Since then, its historical configuration continues to be productively extended – and contested – by both modernists and medievalists who also claim its theoretical mantle.15 While this book is written in acknowledgement of the rich scholarship that Stoichita’s metapainting, or image-within-the-image, has produced, its scope is configured otherwise, in its singular focus on the mirror reflection. As other scholars have argued, metapainting justly includes any pictorial device used to signal art’s status as illusion. This has centred above all on inset framing devices and embedded images. In effect, together they encapsulate the double-sided aspect of Alberti’s claim: that mimetic painting is both a window view and a mirror reflection. Distinctively, therefore, this book argues that the inset mirror-image is the acme of an early modern metapainting, as the very image of painting in itself.

The term surely derives from ‘metatheatre’, the analysis of which is generally given to Lionel Abel’s Reference Abel1963 book of this title. Predominantly concerned with modernist adaptations, yet Abel acknowledged its historical issue within early modernity. Centred on the study of enacted speech, Abel’s study noted Elizabethan theatre’s use of the dialogic aside or soliloquy, for example, in which actors momentarily ‘broke’ the illusion of the proscenium arch through direct address ‘beyond’ the confines of the play to comment on its significance.16 The ready conflation of theatre’s proscenium arch with painting’s picture frame(s) that Stoichita’s study intimated thus opened the way to read painting’s self-aware details as ‘metapainting’. Here visual art could similarly ‘break’ the picture plane to stage its own ontological status as illusion.

As a twentieth-century structuralist scholarship had earlier argued, the early modern inset mirror-image or picture-within-the-painting such as configures the Arnolfini portrait or, later, Velazquez’ Las Meninas may be understood as the pictorial emblem of ‘painting within itself’. That is to say, the reflexive mirror-image within and of this art functions as both imitation and illusion. As such, this book’s greatest intellectual debts within the scholarship are to André Chastel’s ‘Le tableau dans le tableau’, Daniel Arasse’s ‘Les miroirs de la peinture’, and the rich issue of art-historical literature arising from their studied observation of the ‘mirror-image’ in early modern painting.17 Such analysis rests on a matrix of word-image relations encapsulated within historical analogies of the inset mirror-image, further defined as a form of mise-en-abyme.

The early modern inset painted mirror-image was, in Chastel’s words, an abrégé du tableau, or an abridged pictorial motif of painting’s reflective art within itself. Identifying the perspectival ‘rupture’ of the picture plane with the Albertian illusion of a window-like optical recession, this conception of the early modern inset mirror-image as the emblem of painting has, in its twentieth-century scholarship, also been further theorised in relation to modernism’s claim to the condition of ‘art’.18 As Lucien Dällenbach famously argued in a widely influential study of the specular double in twentieth-century literature, Le récit spéculaire: essai sur la mise-en-abyme of 1977, the painted inset mirror-image in early modern art may be understood as a representation of the art of painting within itself.19

***

Distinct from a modernist account, this book instead offers a fully historical consideration of early modern painting’s inset mirror-image as mise-en-abyme, as both a term and a concept, within Renaissance cultures of word and image. For, while the critical projection of mise-en-abyme onto modern art and literature has greatly expanded the theoretical valence of the term, this has tended to occlude its historical specificity within the cusp of the Renaissance. Its earliest – and defining – pictorial application was within late medieval heraldry, to denote the inset imagery at the centre of an armorial shield.20 For this reason it retained its identification with the centre point of any image, and so with the perspectival centre point of Renaissance painting, and thus with the ‘abysm’ of spatial recession. From its armorial exodus, within early modern arts and letters alike, mise-en-abyme also came to connote the concept of any inset image or text, now likened to the inset imagery of heraldry, which was manifest across cultural genres.

Again, its prevailing matrix lay within theatre. In the Shakespearean ‘play-within-the-play’ of Hamlet or A Midsummer Night’s Dream, inset dramatic interludes acted as emblematic commentary or ‘mirror reflections’ on the play proper. From Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s La vida es sueño, and Thomas Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy to Paul Scarron’s Roman comique, or Pierre Corneille’s Illusion comique, the prevailing early modern prototype was of the play-within-the-play, as an embedded ‘mirror-image’ within and of itself.21

Within Renaissance literature, mise-en-abyme also became an allegory of memory and so of time, or the cascading temporal reach of historical knowledge into the past represented pictorially by the optics of perspectival recession. In this regard the Albertian theory of painting as both a window and a mirror configures both temporal-spatial recession into unfathomable depth, and its specular recollection or return on itself. Thus Shakespeare’s Prospero asked Miranda of her life before the storm: ‘what seest thou in the … abysm of time?’ (The Tempest, Act 1, scene 2).22 Such a configuration of memory was perceived as boundless in its capacities of projection and retrospection. Like the pictorially unlimited regress of perspectival spatial illusion, or an infinite cascade of inter-facing mirror reflections, memory was conceived as immeasurable. Linked to the furthest reach of time and memory, the figure of mise-en-abyme became the sign of knowledge itself. For this reason, it was also elided with religious conceptions of the ineffable divine, and the incommensurability of God’s love. In medieval encyclopaedic texts such as Isidore of Seville’s seventh-century Etymologies, the ‘abyss’ had a further ancestry from ancient Greek translations of the Hebrew bible, manifest above all in water as the fount of life’s genesis, and used to signify the unfathomable source of the divine.23 In the words of the early modern intellectual philosopher and educator John Comenius, also a theologian, the immeasurable recollective capacities of the mind are, in the image of the divine, also like an ‘abysm’. Defined as a mirror, the mind reflects all that surrounds it, able to fathom into the depths of all things, to penetrate infinite space ‘even to the heavens’. More broadly, Comenius argued for the pedagogic primacy of visual forms of knowledge, which he understood the mirror-image to represent. 24 As twentieth-century literary scholars of early modernity such as Georges Gusdorf and Herbert Grabes have also argued, along with historical philosophers such as Richard Rorty and Rodolphe Gasché, across Renaissance arts and letters the mirror became the emblem of reflection and so of knowledge tout court.25

Within Renaissance art theory, painting’s perspectival abysm or recession of illusionistic depth was perceived as a mirror-image of the visible field. The specular inset motif within early modern painting was therefore understood as an encapsulation or pictorial metaphor of art’s mirroring mimesis. Further, the emblematic figure of ‘abyme’ or abysm was likened to the infinite illusionistic depth of perspectival recession, so conflating the inset image with the image proper, as an allegory of itself. Analogically, perspectival recession was conceived as a visual metaphor of chronological recession. That is to say, the temporal cast of mise-en-abyme as the figure of memory was, in pictorial terms, approximated to the optical configuration of spatial recession. In this way, ut pictura poesis, painting could rival literature in its claim to represent all forms of knowledge across time. Mirror-like, painting represented the knowledge of the world through the mathematics of optical recession, concluding in a centre point of infinite spatial regress to represent the infinitude of knowledge, en abyme. With the development of a window-like perspectival method for painting, as Alberti had promulgated, each image was itself both a fiction and a truth. Thus its pictorial representation of the visible field was one of conceptually infinite illusionistic depth – perspectivally ‘in abysm’.

Hence in Filippo Parodi’s great Narcissus mirror for the long gallery at the Durazzo Villa Faraggiana, this artist of Bernini’s impress and Alberti’s conception put on display the pictorial eloquence of art’s mimetic illusion as specular. As the gold-carved youth bends to look at his reflection in the depths of poetry’s mirroring source, yet it is the viewer’s own image that is represented there, albeit as ephemeral as Ovid’s account of the pool of Narcissus (Fig. 4).26 If the perception of infinite spatial recession within the geometry of Renaissance perspective was a pictorial illusion, like metaphorical mirrors of cultural memory in the depths of time, yet its fictions were those of a demonstrable optical verity. The mirror reflection was understood as the sign of the image, while the mirror itself connoted the optics of both vision and light as the modus of the visible.

Fig. 4 Filippo Parodi, Mirror Frame and Console Table with the Figure of Narcissus, c. 1667, gilt wood, 450 × 170 × 70 cm, Galleria delle Stagioni, Villa Durazzo Faraggiana (Albissola Marina).

***

Such a historical account of early modern art’s mirroring intent offers a radically historicised reframing of Ernst Gombrich’s celebrated if greatly critiqued Art and Illusion. As Svetlana Alpers and Norman Bryson have argued in turn, Gombrich’s story of art as a progress in perception towards an increasingly precise ‘matching’ of painting with ‘natural’ vision must be recast.27 Thus Erwin Panofsky’s conceptualisation of Renaissance perspective as ‘symbolic form’, rather than Gombrich’s psychology of perception, instead brilliantly understood the Albertian ‘window view’ – as the conceptual and instrumental means by which Renaissance painting was perceived to resemble a mirror – as one of historical convention. In so saying, Panofsky opened the door to a historicised reading of Renaissance art’s mimesis.28 Similarly, Alpers’ address to the optical instruments of mirror magnification for the purposes of topographic illustration, from cartography to astronomy and microscopy, shaped early modern visual cultures of recording that were, in her analysis, the aegis to a newly powerful mimetic ‘art of describing’. In both cases, they argued for a historical analysis of the early modern mimetic image.

Yet the subsequent wrestling of our scholarship with any chronological or geographical account of the early modern mimetic image remains unresolved notwithstanding myriad endeavours to map its development. While we recognise an increasingly diverse ‘play’ with the artistic deployment of the mirror-image motif, from its early fifteenth-century definition in van Eyck to the cascade of pictorial reflections at work in Las Meninas, as at the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, precise temporal delineation of this pictorial development remains both open and diffuse. This book does not, therefore, attempt to map a definitive chronology of art-historical change in the theory or practice of the early modern mirror-image. Nor does it trace a history of the Renaissance mirror as directly coterminous with that of the history of painting, although it does evidence a pervasive early modern perception of an equivalence between painting and mirroring within such an account. Instead, it offers a series of thematically orchestrated chapters concerned with contextualising analyses of different aspects of the mirror’s early modern pictorial manifestations. While the chapters are placed in broadly chronological order, their collective ambition is not, directly, to trace a historical progress of the early modern relationship between painting and mirroring. Rather, they take up those contexts – be they social, cultural, practice-based, scientific, literary, or intellectual history – that offer a heightened or intensified apprehension of the early modern elision between painting and mirroring. As such, the chapters can be read collectively and independently.

The temporal arc of the book runs from Brunelleschi’s demonstration of geometrical perspective’s visual accuracy by means of a mirror reflection at the door of the Florentine cathedral in the early 1400s to the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles in the 1680s; from the Arnolfini portrait to Las Meninas. In this it broadly follows longstanding art-historical convention in the periodisation of early modernity sequentially as Renaissance to Baroque. While acknowledging earlier examples of painted mirror reflections in late medieval/Renaissance manuscript illuminations, this book concerns the inset-mirror motif within the history of painting proper, independent of the illuminated page. There is no endeavour to make this a comprehensive account, for the historical examples of Renaissance ‘mirror paintings’ vastly exceed the scope of a single book.29 Their quantity, in itself, testifies to the powerful historical significance of the motif as the defining metaphor of a mimetic Renaissance art. This book’s concern is to analyse the broader cultural and intellectual reasons for the centrality of the mirror motif.

***

While centred in the study of painting, the book is also concerned with broader cultural interests in the mirror-image. That is to say, it offers an expanded definition of art history as a discipline bound to the study of visual culture in manifold forms, from the decorative arts of the mirror as an ornamental artefact to the scientific use of optical mirrors in the development of the Galilean telescope and the early modern box cameras that presaged the nineteenth-century advent of photography.30 Within the sciences, it is much concerned with the documentary image, or what has become known as the epistemic image, whose purpose was mimetic ‘mirror’ accuracy in the representation of visual knowledge.31 It also traces the broader cultural relationships between the significance of the mirror analogy within early modern painting and the literary arts, from theatre to poetry and philosophy, to demonstrate the central place of the mirror as the sign of the reflective intellect across myriad cultural domains.

Also at stake in the discussion that follows is the interweaving of artisanship with artistic theory in the Renaissance pursuit of visual imitation. As Alpers argued in her celebrated study of the ‘art of describing’, early modern scientific vision, as also painting’s mimesis, was predicated on artisanal modes of viewing, from ocular lenses to the draughtsman’s topographic drawing-frames and mirrors.32 Before the advent of photography, the documentation and circulation of all forms of visual knowledge depended on the draughtsman’s skill, for which the mirror was the model and the instrument. Across the pictorial arts, the mirror thus constituted the paradigm and the practice-based conduit for recording all forms of visual knowledge, comprising architecture, engineering, and science no less than painting. Eliding any neat separation between visual concept and material instrumentation, or its more familiar art-historical designations of theory and practice, this book argues that the artist’s mirror was both technē and logos, at once the technical means and the exemplary model of the Renaissance mimetic image. In practice, the mirror reflection was the workshop means of translating the three-dimensional world into the two-dimensional frame of the painter’s canvas or the draughtsman’s page. Part of a craft knowledge of picture-making as much as the sign of Renaissance image theory, the mirror thus prevailed over the intersections between workshop technologies and patterns of visual thought. Between practice and concept, artisanal know-how and artistic theorisation, the draughtsman’s mirror was both mechanical and epistemic in the production of the mimetic image, and so of Renaissance visual knowledge tout court. This demands our further analysis in several overlapping ways.

On the one hand, in Michel Foucault’s far-reaching history of early modern thought, which he called an archaeology of human knowledge, this intellectual historian studied the vast transition between medieval and modern mentalities as epistemic shifts that structured all aspects of speculation and enquiry. Famously, he discerned a fundamental difference between Renaissance thought, which he characterised by conceptual paradigms of analogy or resemblance configured in the sign of the mirror; to an emerging ‘modern’ episteme of analytical distinction marked by the taxonomic classification of similarities and differences. Within such a historical construct of an emblematic Renaissance episteme, the figure of the inset mirror as mise-en-abyme was analogical. That is to say, and as Foucault brilliantly posited in opening Les mots et les choses with the painted inset mirror of Las Meninas, the early modern image-within-the-image was intended to signify metaphorically as an allegory of itself.33 If the temporal boundaries of Foucault’s differentiation between analogical and analytical patterns of thought may be productively questioned, in the interests of a more fully pluralist historical account, yet the reach of his analysis in its attention to a history of systems of intellectural cogitation is manifold. Thus, in Rorty’s study of early modern epistemology construed as ‘the mirror of nature’, the figure of the speculative mirror or ‘looking glasse’ is considered the very emblem of thought itself. Similarly, Gasché argued that early modernity’s defining metaphor of intellectual process was reflection, which he understood as the mind’s mirroring return of speculative ‘light’.34 Thus the mirror-image was a rebus of mimesis and reflection as the pictorial sign of knowledge and thought.

At the same time, recent scholarship best represented in the work of Pamela H. Smith has turned our attention to Renaissance forms of craft or artisanal knowledge, and above all its material- and practice-based methods of enquiry.35 Across the thousands of pages of Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks, this artist’s central tenet was that the wisdom of books at the centre of Renaissance humanism must be measured by the knowledge of practical experience. In this regard, as Smith has argued for the history of early modern science, the artist’s view was a determining one for the inauguration of modern scientific method, in its accord with the primacy of visual or demonstrable forms of knowledge. In Smith’s terms as in Leonardo’s, this workshop know-how founded in artisanal cultures of experiment, dependent on technē or ‘how-to’ memory over the scholastic logos of books, drove vast epistemic shifts in early modern scientific thought and understanding. It was the rising artisanal knowledge of glass-making that led the development of precision-cut lenses and optical mirrors, for example, which Galileo would both make himself and use in his telescope, so recasting a nascent scientific modernity within the practice-based conduct of early modern optical manufactures.

Smith’s argument lends weight to a material or technological historical determinism in the formation of the new scientific observational methods of early modernity. From the artisanal philosophy of Leonardo to René Descartes’ celebrated encomium of ‘mechanical knowledge’, or the central place of the experimental method in the advancement of all forms of enquiry, what was at stake is what we now recognise as the emergence of modern scientific methods over a medieval scholasticism. Across myriad domains of enquiry, the mirror became the sign of the probing intellect or the light of the mind. A material allegory lost to us today, it signified the artefactual function of the mirror as the locus of reflected light for the purposes of all forms of study in a pre-electric age, as historians of the decorative arts and domestic interiors have best elucidated.36 In the work of intellectual historians such as Debora Shuger, following Gusdorf and Grabes in an analysis of textual references to mirrors pertaining to her larger study of Renaissance ‘habits of thought’, the burgeoning fifteenth-century technology of the glass mirror as the material emblem and instrument of a new-found source of light and so reflection may weigh as significantly in the constitution of ‘Renaissance’ cultures as a Burckhardtian ‘individualism’ or the economic determinism of a Weberian proto-capitalism.37 It has been literary scholars and intellectual historians of early modernity who have most fully acknowledged the fecundity of the mirror metaphor as the sign of light, vision, reflection, and so of thought itself, framed in the figure of the ‘imago’. As this book discloses, the metaphor of the mirror-image is suffused throughout the painting and visual culture of early modernity, to acknowledge the centrality of this figurative paradigm. In Foucault’s celebrated description of Velazquez’ painted mirror-image, Las Meninas, it was words and things, books and mirrors, epistemes and mechanics, logos and technē, theory and practice together, which marked the transition to an emerging modernity. It is within this historical web that the Renaissance mirror – as artisanal object, conduit of light, optical sign, emblematic analogy, and, as argued here, reflected image – took on the wealth of cultural significations that made it into early modernity’s central allegory of vision, and so of painting, as of knowledge itself.

***

Tracing the cultural, material, and artistic history of the early modern mirror, the interdisciplinary facets of this book’s enquiry have determined its prismatic delineation into a sequence of chapters that consider its critical valence within Renaissance cultures variously: as an ornamental artefact, a technology of light, a workshop tool, an instrument of science, a pictorial rebus of illumination and reflection, and a model to the painter’s brush. Thus Chapter 1, ‘Halls of Mirrors’, offers an over-arching discussion of the mirror’s early modern conceptualisation as both a material artefact and a metaphor of illumination. To prise open early modernity’s perception of an analogy between painting and mirroring, the chapter begins with the concluding monument of the book, the Grande Galerie des Glaces at Versailles. The example of Versailles elucidates the book’s analysis of its subject as the relationship of painting to the mirror-image side by side. The chapter traces the early modern conceptualisation of the mirror ranging from princely magnificence and the science of light, the illuminative emblem of all forms of intellectual enquiry, and a metaphor of the soul or psyche within folklore, poetry, theatre, and faith. It further outlines the major contours of the early modern mirror motif across science, literature, philosophy, painting, and decorative art to give a full consideration of the broad parameters of this book’s subject within larger intellectual and cultural histories of the period. Offering an artefactual history of the mirror as object, it maps a typology of early modern glass mirrors as variously decorative, scientific, industrial, and instrumental, marked by their ever-increasing quantity, scale, and clarity of vision, from the hand-held leaded blown-glass spheres of the early Renaissance to full-length quick-silver crystalline pier glass at the close of the seventeenth century. Further, the chapter observes the mirror’s longer history from archaic usage in metallic forms, and the full cultural spectrum of its many metaphorical associations accrued over such a broad arc of time. It charts widespread developments in early Renaissance glass production, making mirrors newly prolific and so readily available across the fifteenth century as never before, as well as possessed of an ever-more brilliant reflective clarity to become the modus of light itself. Acknowledging what intellectual historians such as Gusdorf, Grabes, Shuger, Rorty, and Gasché, following Foucault, have termed an early modern ‘Mirror Age’, it traces the rising technology of the glass mirror as the instrument of light and reflection across all domains of enquiry. Further, it suggests the mirror’s brilliant materiality was perceived to usher in the heightened recognition of an equivalence between the mirror and the image that was foundational to historical development across the arts and sciences alike, so constructing the Renaissance definition of painting as mimesis.

Chapter 2, ‘Armorial Mirrors’, takes up the inset-mirror motif within early Netherlandish painting in the ambit of van Eyck. The insistent and symbolic representation of inset-mirror reflections in works by Petrus Christus, Metsys, and Memling in emulation of van Eyck indicate a considered artistic theorisation of the image as specular. Bound up with nascent definitions of a ‘Netherlandish school’ of art as founded in the manner of van Eyck, as Rudolf Preimesberger has argued, the inset mirror-image may be linked etymologically to the old Dutch term for painting as ‘schild’, or shield.38 This elision between painting and the armorial shield, as a specular surface of reflection like a metal mirror, suggests a heraldic cast to the painted inset mirror’s historic configuration of fifteenth-century Flemish art in its image. Thus the rebus-like composition of armorial imagery within the painted pageant shield may represent the structuring matrix of the earliest definition of Netherlandish art as a mirror-like mise-en-abyme, and its pictorial manifestation in the painted inset-mirror motif inaugurated by the Arnolfini portrait.

Chapter 3, ‘The Artist’s Mirror’, considers the early modern artist’s use of mirrors, along with other visual aids, in both art theory and artistic practice. A field of art-historical analysis brought to prominence by David Hockney’s acclaimed if highly controversial book, Secret Knowledge (2001), this entails the study of early modern optical or mirror-based artistic technologies as a mechanism for translating the visible field of three dimensions into the two-dimensional plane of painting.39 Such devices were broadly used in all forms of land and architectural survey drawing, from military reconnaissance to early modern cartographic science and the subsequent astronomical ‘mapping’ of the heavens. Early Renaissance treatises on art recommended the use of mirrors as painters’ aids in the accurate ‘mapping’ of illusionistic spatial recession, from Filarete’s description of Brunelleschi’s methods of perspectival rendering to Leonardo’s full consideration of the mirror within painting as the ‘master of art’. The mirror reflection became an acknowledged method of Renaissance artistic training precisely because it united theory with practice, just as Leonardo had argued. This is nowhere more self-evident than in what Joseph Koerner has termed ‘the moment of self-portraiture’ c. 1500.40 Tellingly, this new genre of art was not known as self-portraiture until the nineteenth century; instead, it was identified in terms of the self-reflective manner of its making: ‘eim spighel’ or ‘allo specchio’, by means of the mirror. This intellectual firmament of artistic theory in practice reaches its fullest expression in Velazquez’ Las Meninas, as a mirror-image portrait of the artist in the act of painting.

Chapter 4, ‘Specular Sciences’, analyses the relationship between specular ‘truth’ and optical ‘illusion’ in the scientific domain. It considers the new-found status of optical imagery within the observational sciences of early modernity, defined by the advent of its instruments of lens- and mirror-magnified vision, the telescope and the microscope. Just as Galileo upended the surveyor’s field telescope to chart the heavens, Robert Hooke unveiled the highly detailed imagery of the microscope’s magnified view. As the visible proof of scientific discovery, the mirror-image similarly laid new claims to a demonstrable verity. The chapter brings together the observational antecedents to the closely related development of the telescope and the microscope in a range of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century specular or lens-based optical instruments of vision that reconfigured artistic as well as scientific sight. The new-found vision of the optical image paved the way to an ever-greater artistic instrumentation of mimetic accuracy, but also to its ‘mirror-image’ double, in the extreme perspectival distortions of ‘trick imagery’ such as anamorphosis. This configured all manner of ludic perspectival imagery alongside trick mirrors, from the mirror-display cabinetry of the Wunderkammer and the Dutch perspectyfkas to the anamorphic picture-puzzle of Holbein’s Ambassadors, in an early modern emblematics of optical ingenuity as pictorial wit.

Chapter 5, ‘The Mirrors of Venus’, considers the closely intertwined pictorial relationship between the painted representation of the mirror reflection and the female nude in High Renaissance art, from Giorgione’s bella donna at her toilet to the Rokeby Venus. From sixteenth-century Venice to Madrid as to Rome, Paris, and Fontainebleau, across Germany and Flanders, depictions of inset mirror-images were both accompaniments to and metaphors of the perceived artistic beauty of the female form. Together, the female nude and its reflection in the mirror allegorised a newly conceived theorisation of art in terms of visual beauty. As a consequence, the mirror reflection was linked to depictions of love and desire of all kinds, from the venereal to the marital. A metaphor of beauty within the social rituals of courtship and marriage, it was displayed within painting and print as well as myriad domestic decorative arts. Yet within this imagery lay a paradoxical conceit. As in a mirror reflection, the beauty of youth was transient and fleeting, as evanescent as the passage of time. Thus the representation of love, youth, and beauty as mirror-like became a pictorial metaphor of vanitas, or the spiritual passing of all worldly things, like the illusionistic image of Narcissus in Ovid’s shimmering pool. If, on the one hand, the allegorical relationship between the female nude and the mirror reflection was an emblem of art’s beauty, yet the sign was a fully bivalent one that also contained within it the presentiment of its fleeting evanescence.

The book’s conclusion draws together the cultural trope of pictorial reflection to adumbrate the future history of the early modern mirror-image within painting through modernism’s refractive lens. As the ocular model for the camera obscura, the mirror as the figure of vision compasses an intellectual history that spans not only the subsequent development of photography but, taking a leaf from Jonathan Crary, the instrumentation of early modern visuality more broadly.41 At the same time, the Conclusion traces a radical shift in the conception of the mirror motif as the paradigmatic early modern sign of the intellect in Cartesian mode that Stoichita posited. In the wake of the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, the subsequent rise of the early eighteenth-century Rococo decorative mirror interior instead suggested new contiguities between painting and mirroring as inter-related forms of pictorial ornament. The mirror was not only the matrix of eighteenth-century painting, but fully its equivalent, with the introduction of large-scale halls of mirrors that could seemingly ‘replace’ painting entirely.

Collectively, the chapters offer a fully interdisciplinary consideration of the mirror-image as the figurative representation of the early modern visual field. Together they address the analogy between painting and mirroring as it was argued in Renaissance art theory, demonstrated in art practice, and represented in painting itself. The book takes up a double focus, between art-making and art-viewing, to argue that an early modern conceptual elision of the picture plane with the mirror reflection conflated the surface of painting with the instrument of its own mimesis. The contextualising histories advanced across the different chapters elucidate an early modern conceptualisation of the mirror metaphor as the instrument of all forms of knowledge. This is to enable a deeper analysis of the specular configuration of painting and its emblematic manifestations in literature, science, and art. Tracing the mirror-image through a range of cultural contexts, it concludes with the artist’s mirror as the very image of ‘art’ itself. Both in the studio and in artistic representation, it argues, the mirror reflection was the method and the definition of Renaissance painting. It is the early modern conception of a perceived equivalence between painting and mirroring, manifest across all domains of visual knowledge, that forms the subject of this book.