Introduction

Democracy is backsliding in Europe and around the world as citizens’ trust in elected representatives and institutions wanes (Claassen Reference Claassen2020; Foa et al. Reference Foa, Mounk and Klassen2022; Foa and Mounk Reference Foa and Mounk2017). The bulk of representation theories and studies have been focusing on the representatives: their claims (Saward Reference Saward2010), how they mobilize and construct constituencies (Disch Reference Disch2011; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2003), and what makes them good representatives (Dovi Reference Dovi2007). Considerably less is known about the represented and their perceptions of representation (De Mulder Reference De Mulder2023; Wolkenstein and Wratil Reference Wolkenstein and Wratil2021). We ask: How do citizens perceive political representation? And, crucially, how do these perceptions relate to democratic attitudes?

In this study, we offer a theoretical framework for citizens’ perceptions of representation and test it empirically. Our approach draws from theoretical works in representation that focus on the audience (Rehfeld Reference Rehfeld2006; Saward Reference Saward2010) and the citizen’s standpoint (Disch Reference Disch2015), and from empirical studies on citizens’ preferences, perceptions, and expectations as regards political representation (Best and Seyis Reference Best and Seyis2021; Harden Reference Harden2016; Harden and Clark Reference Harden and Clark2016; Holmberg Reference Holmberg, Rohrschneider and Thomassen2020; Jones Reference Jones2016; Lauermann Reference Lauermann2014). Several studies have established that citizens’ perceptions of being represented (henceforth also representation perceptions or feelings of representation) can increase voter turnout (Blais, Singh, and Dumitrescu Reference Blais, Singh, Dumitrescu and Thomassen2014; Kölln Reference Kölln2016), trust in the parliament (Dunn Reference Dunn2015), and satisfaction with democracy (van Egmond et al. Reference van Egmond, Johns and Brandenburg2020; Weßels Reference Wessels, Alonso, Keane and Merkel2011).

Our paper contributes in two important ways to the growing theoretical and empirical interest in citizens’ perceptions of representation. First, we put forth a framework of these perceptions, anchoring it in the foundations of representation theory: Pitkin’s (Reference Pitkin1967) classic multidimensional concept of representation and Weissberg’s (Reference Weissberg1978) distinction between dyadic and collective representations, where the former pertains to an elected representative and the latter to institutions. We draw on these foundations and move beyond previous studies, most of which investigated one or two of Pitkin’s dimensions at a time and focused mainly on dyadic representation (De Mulder Reference De Mulder2023).

Second, we examine our theoretical framework empirically, contributing to the productive interface between political theory and empirical research (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2003). We developed a theoretically informed set of survey items designed to measure citizens’ perceptions and preferences of dyadic and collective representation along Pitkin’s four dimensions. As a proof of concept, we conduct an exploratory study in Israel, a country where all four dimensions are prominent.

Our results indicate that citizens view representation as multidimensional, contributing to their overall sense of being represented. We also find that citizens prefer to be represented on the formalistic and substantive dimensions, but these are not the dimensions they feel represented on. Furthermore, our results show that citizens perceive dyadic and collective representation differently, and that it is the latter that is largely regarded to be in deficit. Crucially, it is collective representation that relates to their attitudes towards democracy. We conclude by highlighting the importance of developing an agenda for studying citizens’ perceptions of representation in general, and of collective representation in particular.

Pitkinian representation: perceptions and preferences

Hanna Pitkin’s seminal book The Concept of Representation (Reference Pitkin1967) proposes a four-dimensional concept of representation: substantive representation of the public’s policy preferences and interests; formalistic representation of the rules that govern the workings of representative democracy; descriptive representation, which pertains to the resemblance between citizens and their representatives in various social categories; and symbolic representation, which is closely associated with issues of identity. Representation scholars broadly adopted Pitkin’s concept as their point of departure (Wolkenstein and Wratil Reference Wolkenstein and Wratil2021), studying, developing, criticizing, and expanding it (e.g. Politics & Gender 2012).

The literature on the substantive dimension has centred around congruence between policy decisions and constituents’ policy preferences (see Wlezien and Soroka Reference Wlezien, Soroka, Dalton and Klingemann2007 for an overview), while research on the formalistic dimension has focused on electoral systems and procedures, accountability, and authorization (Powell Reference Powell2000; Przeworski et al. Reference Przeworski, Stokes and Manin1999). An influential line of studies relates the formalistic aspect of electoral systems to the substantive or descriptive dimensions (Crisp et al. Reference Crisp, Demirkaya, Schwindt-Bayer and Millian2018; Powell Reference Powell2000). Descriptive representation has been extensively studied in terms of sociological categories (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999; Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967; Verba, Nie, and Kim Reference Verba and NieKim1978), diversity, and inclusion (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Phillips Reference Phillips1995; Young Reference Young2002), and in conjunction with substantive representation (Bailer et al. Reference Bailer, Breunig, Giger and Wüst2022; Celis and Childs Reference Celis2020; Yildirim Reference Yildirim2022). The symbolic dimension was the focus of studies on minority groups’ representation (Lombardo and Meier Reference Lombardo and Meier2016; Marschall and Ruhil Reference Marschall and Ruhil2007; Sheafer et al. Reference Sheafer, Shenhav and Goldstein2011) and has garnered attention in studies on the role of populist politicians in Europe and the USA (Cramer Reference Cramer2016; Reinemann, Matthes, and Sheafer Reference Reinemann, Matthes, Sheafer, Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Stromback and De Vreese2016). Still, most empirical studies of representation have not explored all four dimensions in tandem (but see Krook Reference Krook, Cotta and Russo2020; Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler2005).

The prioritization of the dimensions remains under scholarly debate. Pitkin and a long line of representation studies that followed her prioritized the substantive dimension over the descriptive and symbolic dimensions, relying on her often-quoted definition of representation as ‘acting in the interests of the represented, in a manner responsive to them’ (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967: 209). Pitkin deemed the descriptive and symbolic dimensions, which she labels standing-for representation, as less important for political representation (p. 232), because they depend on ‘the representative’s characteristics, on what he is or is like, on being something rather than doing something’ (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967, 61).

The prioritization of the formalistic dimension in Pitkin’s conceptualization has been less clear. Representation scholars, including Pitkin, have usually associated it with the institutions, rules, and procedures through which representatives are chosen (Krook Reference Krook, Cotta and Russo2020; Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler2005). However, Pitkin acknowledged that, especially in the context of the accountability of a representative government (pp. 57–9, 234–40), this dimension pertains not only to institutions but also to the representative activity they enable: ‘the controls or accountability which they impose on the representative … are merely a device, a means to their ultimate purpose, which is a certain kind of behaviour on the part of the representative’ (p. 57). Some subsequent works have explicitly considered the formalistic dimension in tandem with the substantive dimension. Saward, for example, terms the two aspects of the formalistic dimension—authorization and accountability—as well as substantive representation as ‘three modes of acting-for’ (Reference Saward2010, 10). Rehfeld (Reference Rehfeld2006) links the formalistic and substantive dimensions in his discussion of ‘the standard account’ of democratic political representation. Some empirical studies on the sources of citizens’ sense of representation have shown that the formalistic dimension (the quality of procedures and institutions) is no less, and may be even more, important than substantive representation (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002; Rohrschneider Reference Rohrschneider2002; Reference Rohrschneider2005).

The concept of representation claim-making (Saward Reference Saward2010) has put forth the importance of descriptive and symbolic representation. The vast scholarship on the representation of women and minority groups has emphasized descriptive representation (Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2008; Dovi and Wolbrecht Reference Dovi and Wolbrecht2023; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Phillips Reference Phillips1995; Politics & Gender 2012; Young Reference Young2002). And the symbolic dimension is evident in the growing importance of the political-cultural cleavage that shapes citizens’ political preferences and voting behaviour (Dalton Reference Dalton2018; Shamir and Arian Reference Shamir and Arian1999).

There is little research into the dimensions of representation and their prioritization in the eyes of citizens (but see De Mulder Reference De Mulder2023; Harden Reference Harden2016). Constructivist theorists of representation have taken up Pitkin’s emphasis on representation as a relationship, seeing a pivotal role for the represented in making representation democratic (Brito Vieira Reference Brito Vieira and Brito Vieira2017). However, it is still unclear whether Pitkin’s framework, on all of its dimensions and their prioritization, applies to the public. A multidimensional approach is essential for: (1) Examining citizens’ perceptions of representation—whether they feel represented on some dimensions and not others, and (2) Identifying citizens’ preferences of representation—the dimensions that citizens deem most important for their sense of representation.

Addressing this gap, we examine the Pitkinian prescription in the eyes of citizens and their representational preferences. We formulate citizens’ perceptions of Pitkin’s four dimensions: formalistic—perception of the representative’s accountability in using the authority bestowed on them; descriptive—the commonality of the background and sociological characteristics between the citizen and the representative; symbolic—feelings of belonging elicited by the representative; and substantive—perception of congruence between the citizen’s stances and the laws and policies espoused by the representative.

By advancing an approach that focuses on citizens’ perceptions of representation as multifaceted in terms of substantive, formalistic, descriptive, and symbolic representation, we examine which dimensions citizens prefer, which they deem as more important to them. Next, we implement this framework with regard to two types of representative agents—dyadic representation by an elected representative and collective representation by institutions.

Dyadic and collective representation

Following the pioneering study by Miller and Stokes (Reference Miller and Stokes1963), representation has been customarily studied and theorized as dyadic representation, by an individual politician (see overviews by Dovi 2018; Mansbridge Reference Rohrschneider, Thomassen, Mansbridge, Rohrschneider, Thomassen and Mansbridge2020). Weissberg (Reference Weissberg1978) challenged the dyadic approach and identified another type of representation: collective representation, obtained when ‘institutions collectively [represent] the people’ (p. 535). Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967) acknowledged the importance of representation by institutions, and especially the substantive and formalistic dimensions thereof, in the concluding chapter of her book. Other scholars have also emphasized the importance of political institutions in making representative claims (Saward Reference Saward2010), contributing to substantive representation (Brito Vieira Reference Brito Vieira and Brito Vieira2017), and providing surrogate representation, by legislators one did not elect (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2003).

Collective representation as a ‘systemic property’ (Wlezien and Soroka Reference Wlezien, Soroka, Dalton and Klingemann2007, 801) has received considerably less empirical and theoretical attention, and the existing scholarship focuses mostly on the substantive dimension (Lefkofridi Reference Lefkofridi, Rohrschneider and Thomassen2020; Soroka and Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010). Some of these studies do not place themselves within the representation literature, nor do they explicitly refer to ‘collective representation’ (e.g. Gilens and Page Reference Gilens and Page2014; Page and Shapiro Reference Page and Shapiro1983; Stimson et al. Reference Stimson, Mackuen and Erikson1995). A few comparative studies have focused on the importance of citizens’ perspectives on electoral institutions (Blais et al. Reference Blais, Bol, Bowler, Farrell, Fredén, Foucault and Heisbourg2021) and the influence of these views on citizens’ representational judgements (Rohrschneider Reference Rohrschneider2005) and satisfaction with democracy (Karp et al. Reference Karp, Banducci and Bowler2003). Highlighting the formalistic dimension in collective representation, Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) found that when Americans evaluate their government, they care about process rather than policy, or in Pitkin’s terminology—formalistic, not substantive representation.

Several studies have demonstrated the effect of descriptive collective representation in the US state legislatures on voter turnout and on the sense of external efficacy among underrepresented groups (Atkeson and Carrillo Reference Atkeson and Carrillo2007; Clark Reference Clark2014; Uhlaner and Scola Reference Uhlaner and Scola2016). A few other studies examined the descriptive and substantive dimensions at the collective and dyadic levels and showed that dyadic descriptive representation alone is insufficient to affect substantive-collective representation (Harden and Clark Reference Harden and Clark2016; Rocha et al. Reference Rocha, Tolbert, Bowen and Clark2010).

Our framework encompasses citizens’ perceptions regarding both dyadic and collective representations. The ongoing decline in public trust in representative institutions accentuates the importance of distinguishing between citizens’ perceptions of collective versus dyadic representation. These modalities of representation have been defined and operationalized in the theoretical and empirical literature in a variety of ways, resulting in diverging findings (e.g. Andeweg Reference Andeweg, Rosema, Denters and Aarts2011; Golder and Stramski Reference Golder and Stramski2010; Hurley Reference Hurley1982). We draw on Weissberg (Reference Weissberg1978) for collective representation and look at representation by the parliament. For dyadic representation, we consider the elected representative, which could be a single legislator or a political party, depending on the electoral system (Dalton Reference Dalton1985, 277–79; Wolkenstein and Wratil Reference Wolkenstein and Wratil2021, 866–67).

Empirical implications

The framework we propose in this study comprises citizens’ perceptions and preferences of four representation dimensions, applied to dyadic and collective representation. It informs four empirical implications: First, we examine whether citizens’ perception of being represented is multidimensional, encompassing Pitkin’s four dimensions of representation, or rather relies on the dimension they deem as the most important to them.

Second, we investigate citizens’ preferences of being represented on certain dimensions over others. As discussed above, Pitkin has prioritized the substantive dimension. Other scholars suggested that the formalistic dimension is more important. Still others have emphasized the importance of the descriptive and symbolic dimensions in representation claim-making, for the representation of minority groups, and as part of the cultural cleavage in established democracies. We thus explore which of the Pitkin-dimensions citizens deem more important to them.

Thirdly, we compare the above-mentioned citizens’ perceptions (multidimensional) and preferences (among dimensions) in dyadic and collective representation. We investigate whether the perception of representation is multidimensional in both dyadic and collective representations, and which dimensions citizens deem most important to them in dyadic and collective representation.

Finally, we explore the relationship between citizens’ representation perceptions and their attitudes towards democracy. We examine which has a stronger association with citizens’ democratic attitudes—their perceptions of representation on multiple dimensions or their perceptions of representation on the dimension they prefer most. In addition, since collective representation by institutions is the systemic context for dyadic representation, we investigate if citizens’ perceptions of representation by the parliament is more strongly associated with their democratic attitudes, compared to their perceptions of representation by an elected representative.

The empirical setting

Political representation in Israel

We employ Israel as a proof of concept for our theoretical framework. All four dimensions of representation have always been and still are central for the workings of its political system (Galnoor and Blander Reference Galnoor and Blander2018; Horowitz and Lissak Reference Horowitz and Lissak1989). Therefore, the Israeli case provides us with a strong basis to assess whether these dimensions are also present in citizens’ perceptions of representation of dyadic and collective representation.

Israel is a multi-party system, with a nationwide party-list PR (proportional representation) electoral system and an electoral threshold of 3.25 per cent. Since Israeli voters vote for parties with closed lists, strictly speaking, the dyadic representative is a party, and the collective representative is the Knesset. However, Israel is characterized by high levels of personalization, so much so that voters often see individuals as their representatives (Lavi et al. Reference Lavi, Rivlin-Angert, Treger, Sheafer, Waismel-Manor, Shamir, Shamir and Rahat2022; Rahat and Kenig Reference Rahat and Kenig2018).

This political system was designed to allow descriptive representation to its diverse societal groups (Hazan and Rahat Reference Hazan and Rahat2000; Reference Hazan and Rahat2010). Significant electoral and party reforms have put forward formalistic aspects of representation, while the nexus of descriptive, substantive, and symbolic representation is evident in the profound social rifts, issue-based cleavages, and collective identity dilemmas that shape Israeli politics (Arian and Shamir Reference Arian and Shamir2008; Rahat and Itzkovitch-Malka Reference Rahat and Itzkovitch-Malka2012; Shamir and Arian Reference Shamir and Arian1999). Representation predicaments pertaining especially to women, Arabs, and Mizrahi Jews keep all four dimensions prominent (Herzog Reference Herzog1984; Kook Reference Kook2017; Shamir, Herzog, and Chazan Reference Shamir, Herzog and Chazan2020; Sheafer et al. Reference Sheafer, Shenhav and Goldstein2011).

Our data are based on the April 2019 Israel National Election Study.Footnote 1 The election was held early, which is not unusual in Israeli politics. It was precipitated by a coalition crisis over the government’s policy towards Hamas in Gaza, a controversy regarding the military service of ultra-Orthodox Jews (a long-standing divisive issue in Israeli politics), and the attorney general’s recommendation to prosecute Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu for bribery and breach of trust. Being the first in the series of five elections within the next three and a half years, it preceded the political instability and the democratic crises that have ravaged Israel since.

Data and measurement

We rely on the pre-election wave of the Israel National Election Studies (INES) for the April 2019 election. The sample is representative of the Israeli electorate; interviews were conducted on the phone by Tel Aviv University’s B. I. and Lucille Cohen Institute for Public Opinion Research.Footnote 2

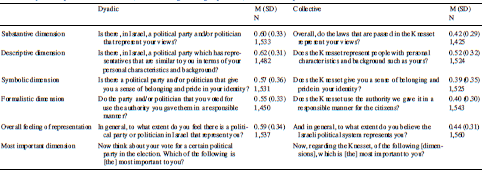

In keeping with our framework, we employed a set of items that we designed to establish and evaluate citizens’ perceptions of the four representation dimensions. These were examined both dyadically, with regard to a politician/party, and collectively, with regard to the Knesset (the Israeli parliament).Footnote 3 The survey comprised of four items for perceptions of dyadic and four items for collective representation, each targeting one of the dimensions. As concerns dyadic representation, respondents were asked to evaluate the extent to which a political party or a politician (1) Represents their views (substantive), (2) Shares their personal and background characteristics (descriptive), (3) Elicits a sense of belonging (symbolic), and (4) Uses the authority bestowed on them in a responsible/accountable manner (formalistic).Footnote 4 The collective representation items were worded similarly but referred to the Knesset. Following Pitkin’s four-dimension concept of representation, we employed these items to create two additive representation scales. The mean score for the dyadic scale is 0.600 (SD = 0.26) and for the collective scale 0.434 (SD = 0.23); Cronbach alpha for the dyadic scale is 0.778 and 0.746 for the collective scale.Footnote 5

Following these eight representation items, we asked the respondents to indicate their preference by asking which dimension is most important to them in dyadic and in collective representation. The collective item referred to the Knesset. The dyadic item was designed to prompt the respondents to think about their vote in the election (prompting the dyadic electoral connection) and to reflect on the dimension which was most important in guiding their vote. In another part of the questionnaire, we posed two general questions about respondents’ overall feelings of being represented, with no relation to any specific dimension: one item asks about overall representation by a political party or politician, and the other—about overall representation by the political system. Table 1 details the full list of the four dimensions and overall representation items and their descriptive statistics.

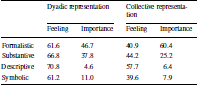

Table 1 Subjective Representation Dimensions, Overall Feeling of Being Represented, and the Most Important Dimension

INES April 2019. The table presents the wording, mean, standard deviation, and N for the representation items. The dimensions items were measured on a 4-point scale and recoded to range between 0 and 1, with higher values denoting a stronger feeling of being represented. The response options were: 1—‘Definitely not’, 2—‘I don’t believe so’, 3—‘I believe so’, 4—‘Yes, definitely / Definitely there is’.

On the overall feeling of representation item, response options were: 1—‘To a great degree’, 2—‘To a certain degree’, 3—‘To a small degree’, 4—‘Not at all’. The order of the responses was reversed, and they were also recoded to range between 0 and 1, with higher values denoting a stronger feeling of being represented

The responses to the dyadic question on the most important dimension (randomized): 1—‘That the party represents your positions on issues that are important to you’, 2—‘That the party has individuals with similar characteristics and background to yours’, 3—‘That the party gives you a sense of belonging and pride in your identity’, 4—`That the party uses the authority you gave it responsibly’. The responses to the collective question (randomized): 1—‘That the laws of the Knesset represent your positions on issues that are important to you’, 2—‘That there is representation of people with characteristics and background like yours in the Knesset’, 3—‘That the Knesset gives you a sense of belonging and pride in your identity’, 4—‘That the Knesset uses the authority we gave it responsibly, for [the benefit of] the public’.

In formulating the survey items, we relied on Pitkin’s definitions and consulted with public opinion and election scholars on the best way to capture citizens’ perceptions in relation to each dimension. We also relied on in-depth interviews with 47 individuals, tapping into the phrasing they used in discussing representation.

To evaluate respondents’ attitudes towards democracy, we created a scale comprising 5 items on satisfaction with the way democracy works, satisfaction with the political system, trust in the government, trust in the parliament and trust in politicians. For each respondent, we summed the scores on these variables and rescaled the values to range between 0 and 1 (Cronbach alpha 0.818). These items were presented to half of the sample (N = 812). The exact wording and descriptive information of these variables is detailed in Table A1 in Online Appendix (henceforth OA).

The following variables were used as covariates in the analyses below: political ideology, gender, age, education, religiosity, nationality (Jewish or Arab), and socio-economic status (by density of living). Our controls do not include winners/losers due to the considerable overlap in Israel between these categories and right/left political ideology. The control variables and sample demographics are detailed in Tables A2 and A3 in the OA.Footnote 6

Analysis: patterns of representation in the eyes of the public

Multidimensional representation

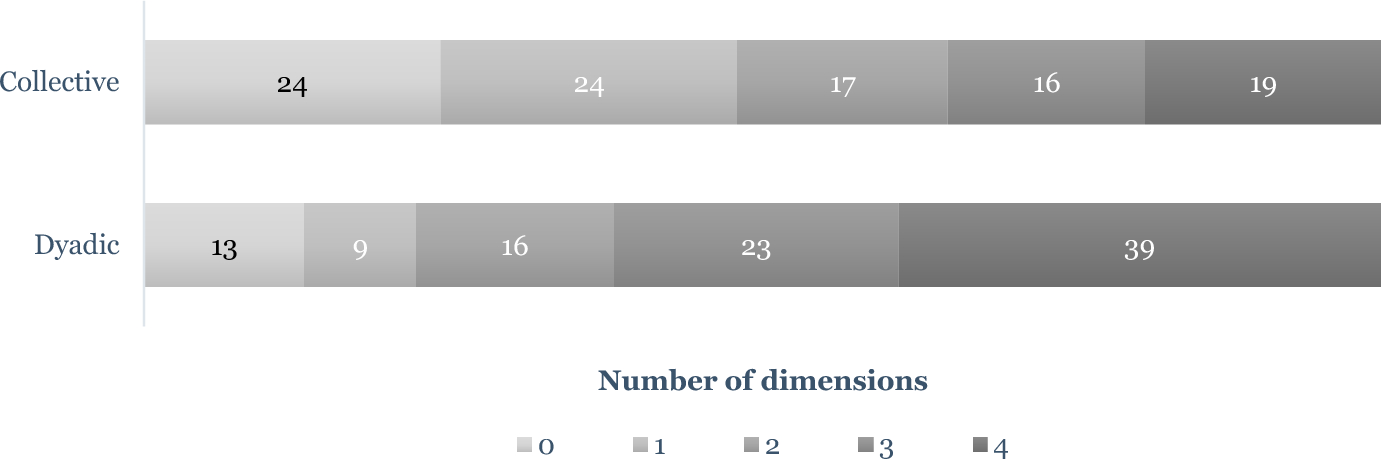

We begin our empirical exploration by looking at citizens’ perceptions of representation, specifically the number of dimensions on which citizens feel represented (Fig. 1). We find that some respondents do not feel represented at all: 24 per cent do not feel the Knesset represents them in any dimension and 13 per cent do not feel there is a party or a politician that represents them. Conversely, other respondents feel represented on all dimensions: 19 per cent in collective representation and 39 per cent in dyadic representation. The rest, 57 per cent in collective representation and 48 per cent in dyadic representation, feel represented on one, two, or three dimensions. This latter group of respondents evidently distinguish between dimensions of representation, as they feel represented in some dimensions but not in others.

Fig. 1 Percentage of respondents who feel represented.

The pattern of interrelationships between the representation dimensions provides another indication that citizens differentiate between dimensions. The correlations vary between 0.403 and 0.518 for dyadic representation, and between 0.350 and 0.516 for collective representation, implying that citizens’ perceptions of representation are comprised of distinguishable dimensions. The Cronbach alphas of the multidimensional scales (0.778 for the dyadic and 0.746 for the collective) indicate that they are coherent measures, bringing together the four dimensions into one overall sense of dyadic and collective representation.

A Principal Component Analysis of the eight representation items tells the same story: The initial results before rotation show that the first (best) factor covers almost half of the variance (45 per cent, eigenvalue 3.619), with all items loading highly and similarly on it, varying between 0.594 and 0.731. This means that there is a general sense of representation incorporating all 4 representation dimensions across both dyadic and collective representations. After (oblique) rotation, the results reveal two representation factors, the dyadic and the collective, each comprising of their four Pitkin dimensions. The two factors are quite strongly related (0.399).Footnote 7

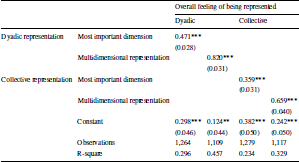

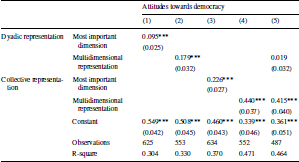

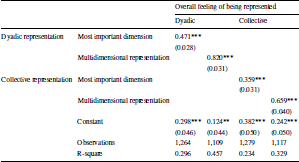

To further examine our first empirical implication, we assess what matters more for our respondents’ overall representation perception: multidimensional sense of representation or feeling represented on one’s most important dimension. We estimate OLS linear regression models, using as the dependent variable the question on the overall sense of being represented by a politician or a party for the dyadic model, and the question on the overall sense of being represented by the political system for the collective model (see Table 2).Footnote 8 The regression results indicate that both the most important dimension and multidimensional representation contribute to citizens’ overall feeling of representation. However, the coefficients for multidimensional representation are almost double the size of those for the most important dimension. It holds for both dyadic and collective representations and is substantial even if we consider that the multidimensional scale is comprised of multiple items. Our findings thus indicate that citizens’ representation perceptions are multidimensional.

Table 2 Perception of Representation and Overall Feeling of Being Represented

INES April 2019. OLS regression models with overall feeling of being represented as the dependent variable. Standard errors in parentheses, *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05

Representation preferences

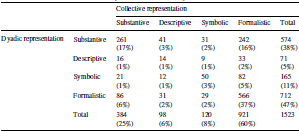

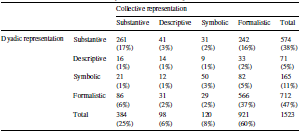

We now move to examine the second empirical implication—respondents’ preferences of representation across dimensions. Table 3 presents crossed frequencies of the most important dimension for respondents in dyadic and collective representation. The frequencies show that citizens prefer to be represented on the formalistic and substantive dimensions. The formalistic dimension is most important to 37 per cent of the respondents, and substantive representation is most important to 17 per cent of the respondents. The most important dimensions for 16 per cent of the respondents are substantive-dyadic and formalistic-collective, while for 6 per cent, these are the formalistic-dyadic and substantive-collective dimensions. Altogether, 76 per cent prefer the formalistic and substantive dimensions at both levels, and 94 per cent prefer one of them at either level. Only 6 per cent prefer the two standing-for dimensions (descriptive and symbolic) at both levels and 24 per cent at either level.

Table 3 Preferences of Dimensions in Dyadic and Collective Representation

INES April 2019. The percentage and number of respondents on the dimension most important for them on the collective and dyadic levels

These findings show that citizens’ preferences square with Pitkin’s low prioritization of the descriptive and symbolic dimensions as well as her emphasis on the substantive dimension for political representation. These preferences also echo previous studies that pointed at the importance of the formalistic dimension (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002; Rohrschneider Reference Rohrschneider2005).

Dyadic and collective representation

The third empirical implication applied citizens’ perceptions and preferences of representation to collective and dyadic representation. We find that in both dyadic and collective representations, citizens hold multidimensional perceptions, but the pattern of these perceptions and citizens’ preferences vary between the two.

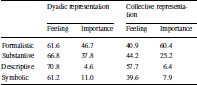

Table 3 shows that respondents clearly distinguish between the dimensions and prefer the formalistic and substantive dimensions over the descriptive and symbolic. However, within this overall pattern, there are notable differences between dyadic and collective representations. In collective representation by the parliament, citizens prefer the formalistic dimension, while the substantive dimension is less important for them by a considerable margin (60 and 25 per cent, respectively). In dyadic representation by a politician or a political party, a similar weight is assigned by the respondents to the two dimensions, with 47 and 38 per cent preferring formalistic and substantive representation, respectively.

We also find different patterns in citizens’ perceptions of dyadic and collective representation. First, in Fig. 1, we showed that 62 per cent feel represented dyadically on three or all four dimensions in contrast with only 35 per cent who feel represented by the parliament. That is, more citizens feel represented in more dimensions dyadically, compared to collective representation.

Table 4 further develops these differences. It presents citizens’ perceptions and preferences of dyadic and collective representation. It shows the share of respondents who feel represented on a given dimension (perceptions) and the share of respondents for whom it is the most important (preferences). In dyadic representation, perceptions of representation are high across the board, with a majority of respondents feeling represented on each of the dimensions (varying between 61 and 71 per cent of respondents who feel represented). In collective representation, perceptions of representation are much lower, ranging between 40 and 58 per cent. A majority of citizens feel represented by the Knesset only in the descriptive dimension, while on the other three dimensions, a minority (of about 40 per cent) does. Thus, citizens consistently feel that they are better represented by a politician or a party than by the Knesset.

Table 4 Perceptions and preferences of representation on each dimension—dyadic and collective representation (%)

INES April 2019. ‘Feeling’ is the share of respondents who feel represented on the respective dimension (perception); ‘Importance’ is the share of respondents prioritizing that dimension as most important to them (preference)

The implications of different patterns of representation perceptions are further clarified when combined with citizens’ preferences of representation (Table 4, right column). The findings show that citizens’ preferences do not match their perceptions of representation. As discussed above, the only dimension on which a majority of citizens feels represented by both the Knesset (58 per cent) and their elected representative (politician or party) (71 per cent) is the descriptive. However, this is also the dimension least important to them at both levels. This is especially consequential at the collective level, where most citizens do not feel represented in any of the other dimensions. In dyadic representation, there are other dimensions citizens feel represented on, resulting in more congruence between perceptions and preferences (the substantive dimension, for example, is second in importance and 67 per cent feel represented on it). In collective representation, by comparison, most citizens do not feel represented in the substantive, formalistic, and symbolic dimensions—all more important to them than the descriptive.

Indeed, the correlations between citizens’ representation perceptions and preferences are very low (see Table B5 in OA). Such low correlations preclude the possibility that citizens may assign more importance to the type of representation that they do not have. It also alleviates the empirical concern that responses to the items reflect an attempt to reduce cognitive dissonance, in the sense that people may prioritize a dimension on which they feel gratified or convince themselves they feel represented on a dimension which they value highly.

To sum, we find that citizens’ perceptions of being represented are multidimensional in both dyadic and collective representations, but that they feel less represented by the Knesset and prefer different dimensions, compared to their dyadic representatives (be it a party or a politician).

Representation and democracy in the eyes of the public

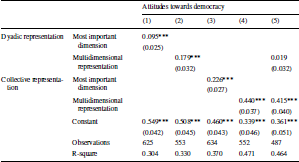

Our fourth empirical implication relates representation perceptions to attitudes towards democracy. Table 5 presents linear regression models of citizens’ attitudes towards democracy on their representation perceptions—multidimensional and the most important dimension. The results present a positive relationship between representation perceptions—especially multidimensional—and attitudes towards democracy. The first four models show higher coefficients for the multidimensional scales, compared to representation on the most important dimension (much like with the overall feeling of being represented, Table 2).Footnote 9

Table 5 Perception of Representation and Attitudes towards Democracy

INES April 2019. OLS models with a scale of attitudes towards democracy as the dependent variable. The scale includes 5 items: satisfaction with the way democracy works, satisfaction with the political system, trust in the government, trust in the parliament, and trust in politicians. These items were presented to half of the sample; therefore, the number of observations in each model is about half the original sample (N = 812). The items in the scale were recoded to range between 0 and 1, with higher values standing for higher assessment, more satisfaction, and more trust, respectively. The exact wording of these variables is detailed in Table A1 in the OA

Standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05

Table 5 establishes another important point with regard to dyadic and collective representation. Comparing between Models 1 and 3, and Models 2 and 4, we find that feeling represented by the parliament, whether on the most important dimension or across all dimensions, is more strongly related with citizens’ attitudes towards democracy than representation by one’s electoral representative (a party or a politician). Model 5 in the last column includes both dyadic and collective multidimensional representations and shows that only the collective scale remains significant. This finding reveals that it is only collective multidimensional representation that is significant in terms of citizens’ attitudes towards democracy.

Conclusion

This article presents a novel framework and an empirical exploration of citizens’ view of representation. Zooming in on the citizens, we find that their perceptions are Pitkinian in the sense that they fit her theoretical formulation of representation: citizens consider different dimensions of political representation and overwhelmingly care less about the descriptive and symbolic dimensions which Pitkin depreciates. These findings call for future studies that will explore individual, group, and country-level variations in representation perceptions and preferences, especially among minority and underserved groups.

We further find that citizens’ representation perceptions and preferences differ along dyadic vs. collective representation and that they are correlated with pro-democratic attitudes. Of the two, it is the multidimensional sense of representation at the collective level that relates to the overall sense of representation and to citizens’ democratic attitudes. Our study thus substantiates Weissberg’s (Reference Weissberg1978, 545–7) surmise that citizens may be more concerned with collective than dyadic representation. Yet, crucially, the findings indicate that citizens perceive this representation to be in deficit. The discrepancy is especially prominent when it comes to descriptive representation. Previous studies, as well as normative theories, have suggested that descriptive representation, especially by institutions, is germane to substantive representation. Our findings challenge this linkage. A majority of respondents felt represented by the parliament descriptively but not substantively, while the former dimension was the least important to them. Our results thus call for more theoretical and empirical attention to collective representation from the citizen’s standpoint, and for its multidimensional make-up.

Our examination of citizens’ perceptions and preferences of representation across multiple dimensions establishes their relevance to citizens’ attitudes towards democracy. Our findings show that the demand for representation is poorly met—citizens feel represented in dimensions that are not important to them. It is therefore not surprising that the correlation between feeling represented on the most important dimension and positive attitudes towards democracy is weaker than that of multidimensional perceptions of representation. A multidimensional approach to representation in the eyes of citizens is thus crucial for understanding the dynamics of democratic legitimacy and backsliding.

The present study is not without limitations. First, it focuses on one election in one country. The Israeli case was chosen as a proof of concept because it is known to encompass all four dimensions, allowing to examine citizens’ perceptions of them. The findings proved robust in another election in Israel. However, in other countries, Pitkin’s dimensions may manifest in other ways and reflect differently in citizens’ views of representation. Israel is surely not the only case in which all dimensions are manifested, but some of our findings—such as the prominence of the descriptive dimension—may be shaped by the characteristics of its political system. Future studies that will take a comparative perspective may examine how different aspects of electoral systems manifest in citizens’ perceptions of representation dimensions.

Second, Israel’s multi-party system may lead to a potential trade-off between fragmentation and representation at the dyadic and collective levels. The large number of parties could increase dyadic substantive representation but could make it more difficult to achieve substantive representation at the collective level, driving the differences we find in dyadic and collective representation. Future comparative studies could highlight whether this trade-off changes under different electoral systems.

Our theoretical framework draws from Pitkin’s classic conceptualization of representation, which has influenced a long line of theories and empirical studies of representation. Recent scholarship challenges Pitkin’s conceptualization and highlights new approaches and concepts, most notably the notion of the audience in the context of representation claim-making. Our framework of citizens’ perception of representation could be further developed in connection with the role of the audience in accepting and rejecting representation claims made by representatives.

In her last account of representation (Reference Pitkin2004), Pitkin ponders the intricate relationship between representation and democracy, observing that ‘the arrangements we call “representative democracy” have become a substitute for popular self-government, not its enactment’ (p. 34). If this is indeed so, the time is ripe to bring the citizens into our theories and studies of representation, especially collective representation by political institutions. The theoretical framework and the empirical examination in this study provide a first step in this direction.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by The Israel Science Foundation (Grant No. 2315/18).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Bar-Ilan University.