Introduction

The year 2022 was a year of contradictory developments in terms of political stability in the Netherlands. On August 2, 2022, Mark Rutte of the Liberal Party/Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD) became the longest-serving Prime Minister in the country's history, after 4311 days (almost 12 years) in office. At the beginning of the year, a new government was formed, thereby concluding the longest formation period since the start of parliamentary democracy in 1848. The newly formed government was tasked with steering the country through a tumultuous period. The year was marked by soaring energy prices and rising inflation in the wake of Russia's invasion of Ukraine and a humanitarian crisis surrounding the housing of asylum seekers, as well as large-scale civil unrest in response to the government's plans to reduce nitrogen emissions. The government's inability to resolve the nitrogen crisis gave rise to disruptive farmers’ protests and led to the first ministerial resignation of the new Cabinet.

Election report

There were no major elections or referenda in the Netherlands in 2022.

Cabinet report

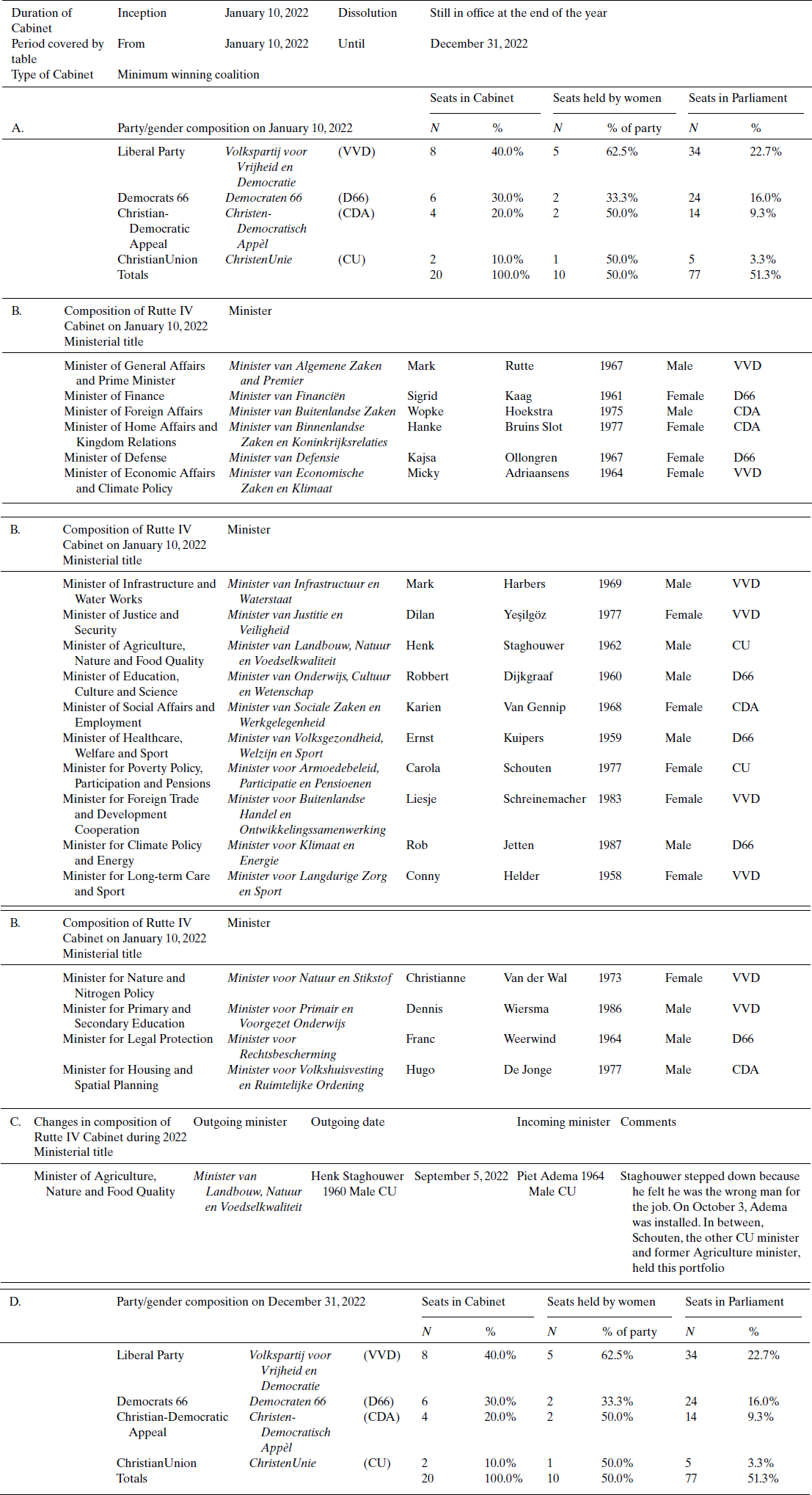

On January 10, 360 days after the resignation of the Rutte III Cabinet, and 299 days after the 2021 general election, the Rutte IV Cabinet was installed by the King (see Table 1). The coalition consisted of the same four parties as the previous government: the conservative-liberal VVD, the social-liberal Democrats 66/Democraten 66 (D66), the center-right Christian-Democratic Appeal/Christen-Democratisch Appèl (CDA), and the Christian-social ChristianUnion/ChristenUnie (CU). The total number of ministers increased from 15 posts in the final days of Rutte III to 20 in Rutte IV. While the ministries in Rutte IV remained unchanged, five new ministerial positions were created, namely, the Minister for Climate and Energy Policy, the Minister for Nature and Nitrogen Policy, the Minister for Housing and Spatial Planning, the Minister for Long-term Care and Sport, and the Minister for Poverty Policy, Participation and Pensions.

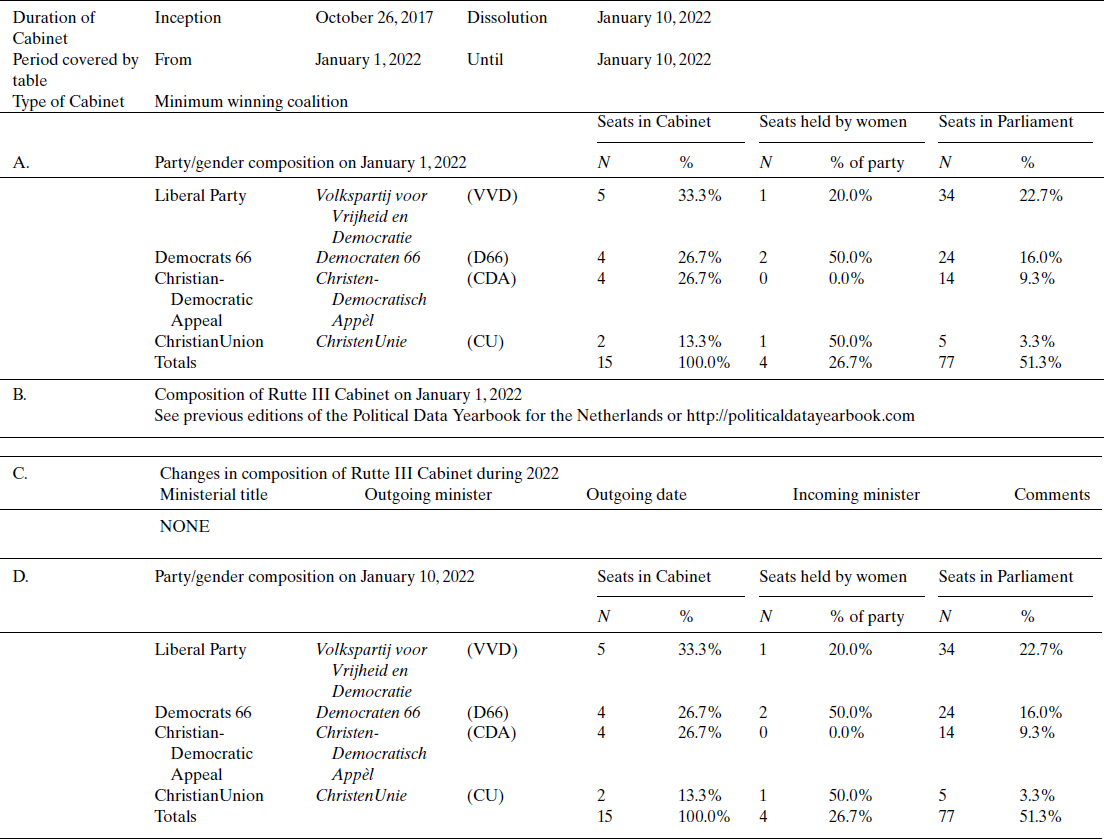

Table 1. Cabinet composition of Rutte III in the Netherlands in 2022

Source: www.rijksoverheid.nl, 2023.

Many ministers of Rutte III returned with a different portfolio in Rutte IV (see Table 2). For instance, former Foreign Minister Sigrid Kaag (D66) was appointed Minister of Finance, while former Finance Minister Wopke Hoekstra (CDA) became Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Carola Schouten (CU) switched her portfolio from Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality to Poverty Policy, Participation and Pensions. While the newly formed government had a majority in the lower house of Parliament (Tweede Kamer or House of Representatives), it did not have a majority in the upper house (Eerste Kamer der Staten-Generaal or Senate). Thus, on legislative and budgetary matters, it effectively functioned like a minority government.

Table 2. Cabinet composition of Rutte IV in the Netherlands in 2022

Source: www.rijksoverheid.nl, 2023.

The new coalition agreement titled “Looking out for each other, looking ahead to the future” had already been presented at the end of 2021. One key concern for the coalition agreement was to restore trust by reassuring citizens that the new government would act as a reliable, just, and accessible servant of the people, in particular, after the scandal surrounding childcare benefits (see Otjes & Hansma Reference Otjes and Hansma2021). To this end, the coalition agreement included a commitment to ensure a clearer separation of powers between Parliament and Cabinet, lower court fees, the introduction of constitutional review, and a fundamental reform of the system of allowances that had led to the childcare benefits scandal. The coalition agreement also contained an explicit goal to combat climate change and tackle the nitrogen pollution crisis. While the Council of State had rejected the existing government policy concerning nitrogen emissions in 2019 (see Otjes & Voerman Reference Otjes and Voerman2020), the Rutte IV Cabinet committed to reducing nitrogen emissions by at least 55 per cent by 2030. To this end, the coalition introduced a 35-billion Climate and Transition Fund to create the required energy infrastructure and make transport more sustainable. The government also announced public investment into education, childcare, housing, infrastructure, culture, and research. Finally, the liberal and Christian parties agreed that a number of medical ethical issues (such as decisions on abortion regulations and end-of-life assistance) would be left to the private conscience of individual Members of Parliament (MPs).

In the fall of 2022, the Rutte IV Cabinet suffered its first ministerial resignation: on September 5, Henk Staghouwer (CU), the Minister of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, stepped down, after concluding that he was the “wrong man for the job.” During his nine-month-long appointment, he had struggled to articulate detailed plans for the agricultural sector that would be in line with the government's targets to reduce nitrogen pollution. Staghouwer was replaced ad interim by his predecessor, Carola Schouten, who concurrently served as Minister of Poverty, Participation and Pensions. On October 4, the post was taken over by Piet Adema, who had served as chairperson of the CU until April 2021.

Parliament report

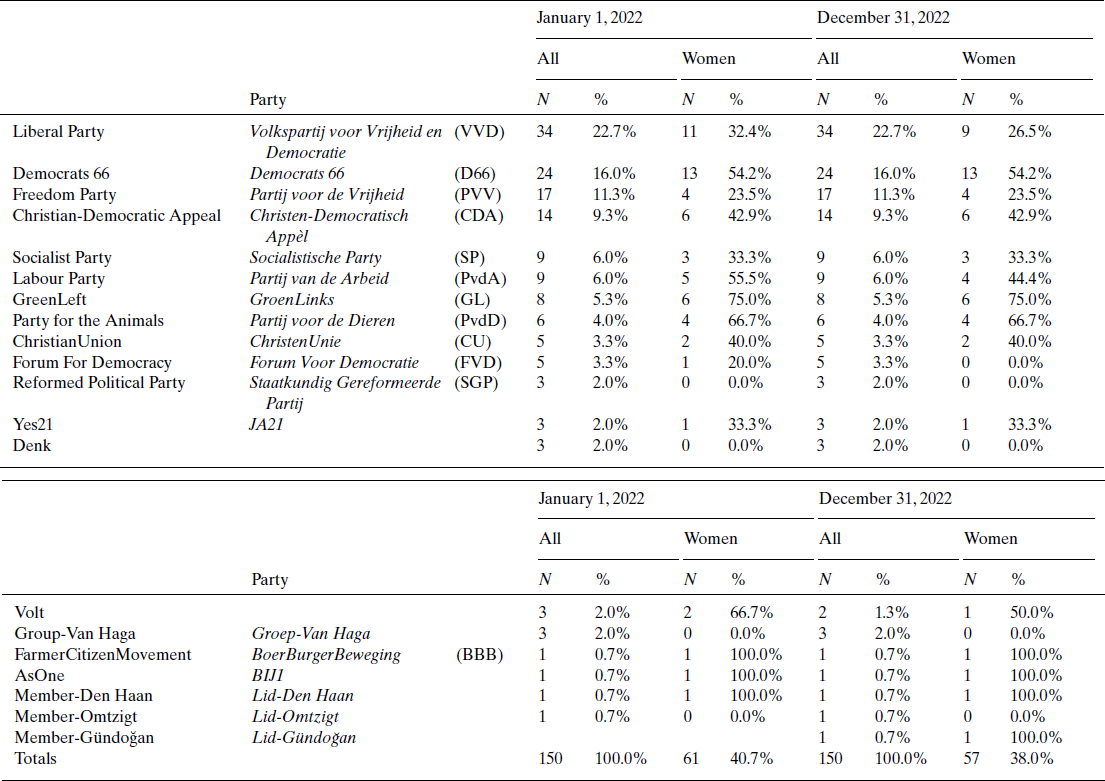

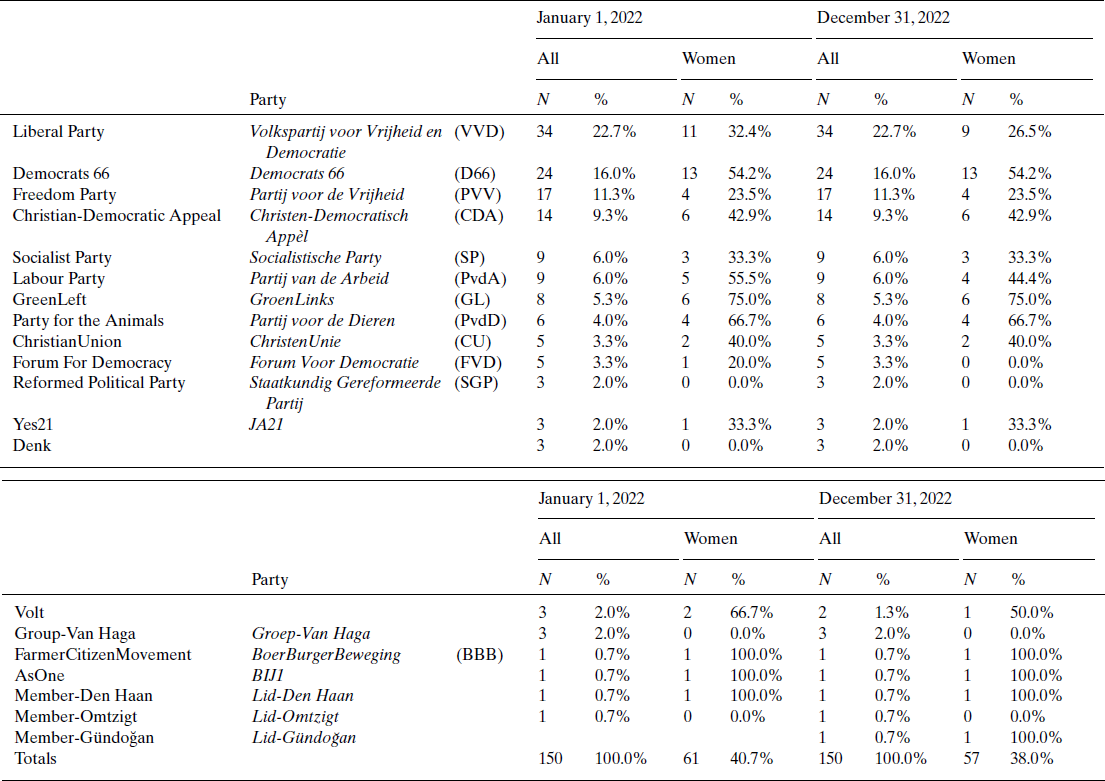

The 2021 election already delivered the most fractionalized Parliament in Dutch history. In 2022, both houses of Parliament further fragmented, resulting in 20 different parliamentary party groups (PPGs) in the lower house (see Table 3). In addition to this fragmentation, two other developments in Parliament are noteworthy: the way Parliament and PPGs dealt with transgressive behavior by MPs, and the radicalization of the far-right Forum For Democracy/Forum Voor Democratie (FvD).

Table 3. Party and gender composition of the lower house of the Staten-Generaal in the Netherlands in 2022

Notes:

1. Denk means “think” in Dutch and “equal” in Turkish.

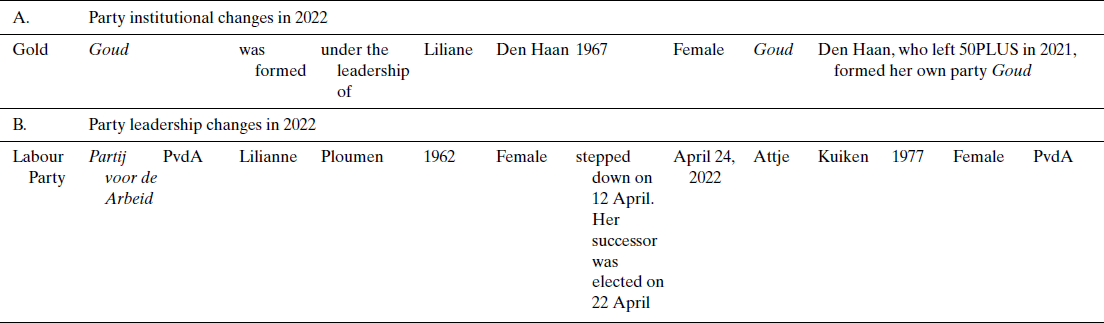

2. Den Haan founded her own party Gold (Goud) in 2022.

Source: www.tweedekamer.nl, 2023.

In 2022, Parliament witnessed several cases of transgressive behavior. Two cases stood out, concerning Nilüfer Gündoğan from Volt and Khadija Arib from the Labour Party/Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA). On February 13, the PPG leader of Volt, Laurens Dassen, announced that Nilüfer Gündoğan was suspended from the parliamentary group, pending an investigation of undesirable behavior, including intimidation and abuse of power. Gündoğan responded by suing her party, Dassen, and the accusers for libel and defamation. On February 26, Gündoğan was expelled from the PPG but proceeded to challenge her expulsion in civil court. On March 9, the court reinstated her, ruling that Volt had not followed proper procedures, and Dassen issued a public apology. This was a far-reaching decision, allowing judges to decide on internal PPG matters. On March 22, Volt appealed the verdict, changed its internal rules, and expelled Gündoğan from both the PPG and the party for suing the people who had reported her transgressive behavior. However, Gündoğan refused to give up her seat and continued to serve as an independent MP, thereby bringing the number of PPGs in the lower house to 20.

A second high-profile case involved Khadija Arib, former Speaker of the House of Representatives and appointed as chair of the upcoming parliamentary committee of inquiry on the government's handling of the coronavirus pandemic. On September 28, her successor as Speaker of the House, Vera Bergkamp, announced that the Presidium of the House of Representatives would start an independent investigation regarding allegations of undesirable behavior against Khadija Arib. The investigation was prompted by two anonymous letters accusing Arib of creating “an unsafe work environment” and an alleged “reign of terror” during her time as Speaker. In response, Arib announced that she felt the investigation was a political reprisal and resigned as MP. A group of opposition MPs voiced their concerns and frustrations, demanding clarification from Bergkamp about the state of affairs surrounding the investigation. The incident resulted in a wave of resignations by top staff in the House, including the Griffier (Clerk of the House),Footnote 1 who felt let down by politicians in the period after the allegations against Arib were revealed.

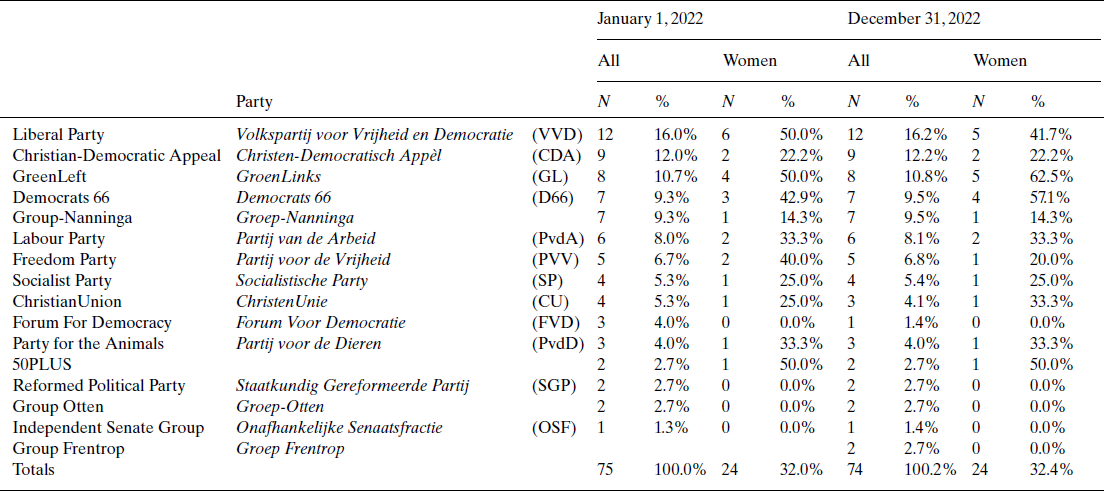

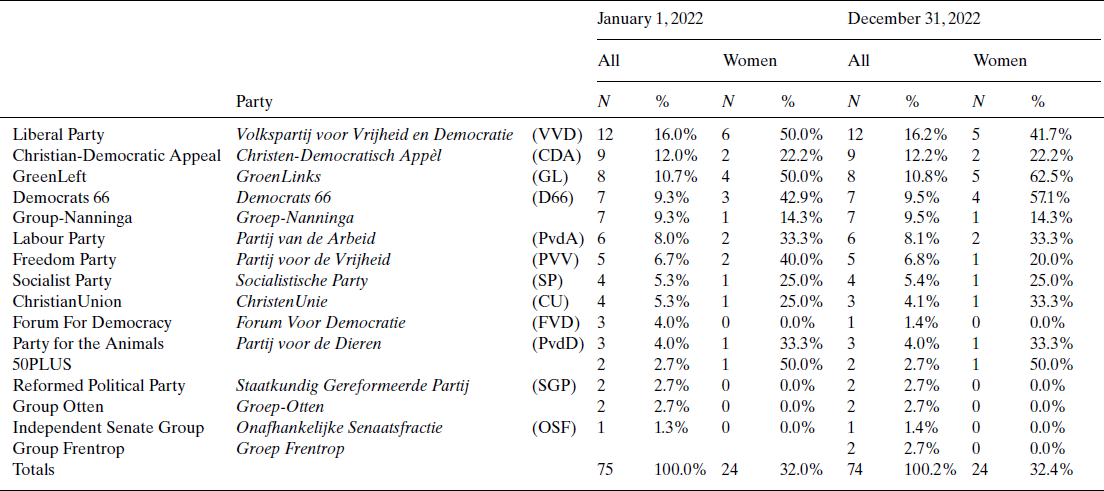

Another key issue that preoccupied MPs in 2022 was the radicalization of FVD, which led to strong normative responses by other parties and politicians. On March 30, two Senators, Theo Hiddema and Paul Frentrop, left the FVD over the fact that their lower house PPG had refused to attend when Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy addressed the Tweede Kamer via video link. Hiddema in particular had been critical of the FVD's pro-Russia stance following the invasion of Ukraine. This resignation left the FVD with just one seat in the upper house. In 2019, FVD had been tied for the most seats after entering the upper house with 12 Senators, but 11 of them left the party between 2019 and 2022. Hiddema and Frentrop decided to hold on to their seats, which brought the total number of PPGs in the upper house to 16 (see Table 4).

Table 4. Party and gender composition of the upper house of the Staten-Generaal in the Netherlands in 2022

Notes: Group-Nanninga is politically aligned with Yes21 in the lower house.

Source: www.eerstekamer.nl, 2023.

During the general budget debate on September 21, FVD-leader Thierry Baudet stated that Minister of Finance, Sigrid Kaag (D66), had studied at St. Anthony's College in Oxford, which, in his words, was “a training institution for Western secret services; in other words, for precisely the globalist elite attempting to plan our lives from behind the curtain.” He thereby insinuated that Kaag had been recruited as a spy by these organizations. In response to this conspiratorial allegation, and in an unprecedented move, the entire Cabinet left the House in protest. The drama around Baudet continued on October 18, when he was suspended from participating in parliamentary debates for seven days for failing to disclose his additional jobs and business dealings in the parliamentary register. Two other FVD MPs, Freek Jansen and Gideon van Meijeren, were reprimanded for the same reason.

Besides these issues pertaining undesirable behavior of MPs and the scandals surrounding FVD, Parliament was preoccupied with organizing three intensive parliamentary inquiries. The first of these inquiries concerned an in-depth investigation into the decision-making process surrounding the extraction of natural gas in the Groningen region, the ensuing man-made earthquakes, and the government's response (or lack thereof) to the damage claims for housing property in the region. The committee, which was chaired by Tom van der Lee from GreenLeft/GroenLinks (GL), was installed before the 2021 elections, and public hearings were held between June and October of 2022. The second parliamentary inquiry concerned fraud policy, with a particular focus on the childcare benefits scandal. The committee, which was chaired by Salima Belhaj (D66), was appointed in February 2022 to conduct research into public service provision and fraud prevention in government services. Public hearings were scheduled to take place in 2023. The third inquiry concerned the government's coronavirus policies. In July 2022, Parliament appointed a preparatory committee, which was led by Khadija Arib. Following her departure, Mariëlle Paul (VVD) took charge.

Political party report

On April 21, Lilianne Ploumen stepped down as MP and leader of the PvdA, explaining that the role did not suit her. Attje Kuiken succeeded her.

On June 11, members of GL (in a referendum) and PvdA (during its party congress) voted in favor of forming a joint group in the Senate after the 2023 provincial elections, thereby deepening the cooperation that the two parties had initiated in 2021. On December 1, they jointly presented their two separate lists for elections. In anticipation of their common PPG in the upper house, the two parties coordinated the compilation of their candidate lists.

On September 13, Liane den Haan, who previously served as the single remaining MP for 50PLUS, but who had left the party in May 2021, announced that she would form her own pensioners’ party called Goud (or Gold in English, with the same reference to the word “old”).

On October 7, Eric Wetzels was elected new chairperson of the VVD. In an internal election, he won two-thirds of the vote against Onno Hoes, who had been put forward by the executive board and the party leadership. Wetzel's election can be seen as a sign of unrest in the governing Liberal Party after the party congress had previously voted down the government's nitrogen policy (see below).

Details of the changes in political parties can be found in Table 5.

Table 5. Changes in political parties in the Netherlands in 2022

Source: See main text.

Institutional change report

A number of constitutional amendments were considered and debated in 2022. On July 5, the upper house accepted six of these. These included extending the right to private communication to all forms of telecommunication, codifying the right to a fair trial; adopting a preamble for the constitution noting that it guarantees democracy, the rule of law and constitutional rights; creating an electoral college that would allow citizens who reside outside of the Netherlands to vote for the Senate; and amending the process of constitutional revision. This marked the most extensive constitutional revision since the 1980s. On July 6, a proposal to introduce binding, citizen-initiated, corrective referenda, failed to reach a two-thirds majority in the lower house in the second reading.

Issues in national politics

The Dutch government faced three major crises in 2022: a nitrogen crisis, a cost of living crisis, and a humanitarian crisis.

Before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, nitrogen had arguably been the biggest and most controversial issue that the government was facing (see Otjes & Voerman Reference Otjes and Voerman2020). In 2019, the highest administrative court had rejected the government's nitrogen regulations, forcing the latter to draw up a new policy that would reduce nitrogen emissions while also allowing for the construction of new homes and roads. An important source of nitrogen emissions is cattle farms, so the government proposed that provinces would need to provide detailed plans that would include buying out livestock farmers in specific areas. This was met with great resistance from farmers, who organized mass protests, blocked roads with farm equipment, and intimidated politicians at their homes. The government's plans were also met resistance from CDA and VVD members. On June 11, the VVD's party congress rejected the Cabinet's proposed policies.

In July, the government appointed Johan Remkes (who had previously served as Cabinet informateur) as independent chair to mediate talks between the government, farmers’ organizations, and environmental groups. During these negotiations, the more radical farmers’ organizations suspended their protests. In August, the Minister of Foreign Affairs and CDA leader, Wopke Hoekstra, noted that, in his view, the commitment in the coalition agreement to cut nitrogen emissions in half by 2030 was “not holy.” The fact that the mediation process that Remkes chaired was unaffected by the resignation of the Minister of Agriculture, Staghouwer, is indicative of how irrelevant this government official had become.

In an effort to mediate between the government and farmers, Remkes presented a report in October 2022, in which he insisted that the government had to close down up to 600 factory farms and other major polluters in order to reduce nitrogen emissions. The report also criticized the government for issuing exemptions for construction projects. In November, the Council of State rejected another government-proposed exemption scheme to circumvent nitrogen regulations (see Otjes & Hansma Reference Otjes and Hansma2021). Taken together, these decisions complicated matters for the acting government. It remains to be seen how Rutte IV will navigate the nitrogen crisis.

The most important geopolitical event of the year was undeniably the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. This inevitably also affected the Netherlands. In 2016, the Dutch voters had rejected Ukraine's association agreement with the European Union (EU) in a consultative referendum (Otjes & Voerman Reference Otjes and Voerman2017). In the ratification process, the Dutch government had asked the EU to put in writing that Ukraine was not a candidate for EU membership. In response to the 2022 invasion, however, the Dutch government quickly dropped its resistance to Ukraine's status as a candidate EU member.

The invasion of Ukraine and the EU's sanctions to the Russian energy sector led to soaring energy prices, which sparked a cost of living crisis in the Netherlands. In 2022, inflation rose to 12 per cent. In May, the government responded by lowering fuel taxes and issuing energy supplements for lower-income families. The government also promised to introduce a temporary price cap on energy bills from January 2023 onward.

The invasion of Ukraine also caused millions of people to flee to neighboring countries and beyond. Over the course of 2021, over 80,000 Ukrainian refugees fled to the Netherlands, which increased pressures on already strained facilities for housing asylum seekers. The central reception center in Ter Apel was no longer able to house all incoming asylum seekers. To be clear, the shortage of refugee housing was mainly the result of prior budget cuts on asylum centers. In the spring and summer, hundreds of people were forced to sleep outside. This created a humanitarian crisis, which culminated in the arrival of Doctors Without Borders to provide emergency medical and psychological care to people in need.

In August, the coalition struck a deal to address the strain on the asylum system: important elements included temporary limits on family reunification applications, a temporary halt on admitting asylum seekers from Turkey (thereby going in against the EU-Turkey deal), and a clause that would enable the central government to force municipalities to house asylum seekers. Even though the VVD held the position of junior minister of Asylum and Migration, the party's parliamentary group was unhappy with the new asylum bill, particularly the law to force municipalities to open up reception locations for asylum seekers. After an intervention by the Prime Minister, the VVD PPG and the VVD congress eventually accepted the deal. In December, the court in The Hague ruled that the government's restrictions on family reunification rules had no legal basis, leaving the deal that the coalition had negotiated up in the air.