Introduction

Idrija, in central Slovenia, prospered as a mining town following the discovery of mercury ore at the end of the fifteenth century (Bevk et al. Reference Bevk, Kavčič and Leskovec1993). Under Habsburg control, Idrija became the second largest mercury mine in the world and an important economic and technological centre in Early Modern Europe (c. AD 1500–1800) (Valentinitsch Reference Valentinitsch1981). In 2012, the site was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in a joint listing with Almadén in Spain.

Here, we report the results of excavations and surveys in 2019 carried out on mercury-production sites surrounding the mine. Until the middle of the seventeenth century, mercury was produced in the forest outside the town using ceramic vessels. So far, 21 production sites are recognised around Idrija (Čar & Terpin Reference Čar and Terpin2005; Gosar & Čar Reference Gosar and Čar2006) (Figure 1), identified by large accumulations of plain pottery sherds. The technique of using ceramic vessels to extract mercury from ore was documented by Georgius Agricola in his 1556 book De re metallica (Hoover & Hoover Reference Hoover and Hoover1950: 427). Agricola describes the use of either paired or single vessels, with the former mainly used at Idrija (Figure 2). The upper part of the vessel (the lid) is described as flask-shaped, tapering towards the rim; the lower part (the body) is cup-shaped with upright walls (see inset illustration from De re metallica in Figure 1). To extract the metal, crushed mercury ore was placed in the lid, which was then sealed with moss and combined with the body before the combined pottery was buried in the ground and a fire built around the lid. The mercury would evaporate from the ore heated in the lid and the vapours would cool in the body, leading to the accumulation of liquid mercury in the body.

Figure 1. Distribution of early mercury production sites around Idrija: top right) illustration from De re metallica; inset photographs) excavated sites 1, 5 and 10, and surveyed site 9. (figure by authors).

Figure 2. Mercury ore roasting pottery: 1–3) Idrija Municipal Museum; 4) Škofja Loka Museum; 5–9) seals excavated at Trate (figure by authors).

Fragments of mercury-producing pottery of a shape similar to those illustrated in De re metallica and examples exhibited in the Idrija Municipal Museum have been collected as surface finds or from stream-eroded cross-sections around Idrija by local researchers and collectors. However, the dating and shape differences of the pottery have not previously been studied in detail. To explore the early mercury-production process, we excavated four sites in the forest around Idrija and collected pottery sherds from stratified deposits for further study.

Results

Trate

The Trate site is the closest to the town of Idrija. A 1 × 1m excavation unit placed on a terrace by the stream beside the site revealed a 0.3–0.4m-thick layer of artefacts under the topsoil. Most pottery sherds were small and the soil contained burnt and carbonised materials. A large number of ring-shaped clay objects (Figure 2 nos. 5–9), possibly used to seal the joint between the lid and body, were also found. Clay seals have not previously been reported, so their identification in an archaeological context at Trate is a significant discovery.

Padarjeva grapa

Located in relatively open terrain beside a stream, a mound cut by a passage or small path occupies the central part of this site. A black soil deposit is observed in the cross-section (Figure 3), possibly indicating the presence of mercury, but carbonised material is also observed in the soil. The wall of the passage was cleaned and partially excavated. The pottery is characterised by thin walls and a high sand content. Ring-shaped clay objects were also excavated. Beneath the black soil layer lies a 50mm-thick layer of slightly heat-hardened, grey clay and a 170mm-thick horizontal layer of brown clay, possibly the result of land preparation work for the hearths. A possible linear arrangement of large limestone boulders was also observed.

Figure 3. South profile of the mound at Padarjeva grapa (figure by authors).

Prenštat

A 1 × 1m test pit was excavated where geomagnetic survey indicated a thick pottery accumulation. Below a layer of topsoil and broken pottery fragments (80mm thick) was a 0.3m-thick layer consisting almost entirely of pottery sherds (Figure 4: left). Several nearly complete vessels were excavated in a row at the bottom of this pottery layer (Figure 4: right). These vessels are all cylindrical (morphologically similar to the vessels in Figure 2), and their colour and clay composition are uniform, suggesting that they were produced over a limited period of time. The absence of carbonised material or burnt clay suggests that firing did not occur in the excavated area.

Figure 4. Test pit at Prenštat revealing an accumulation of pottery sherds (left) and the nearly complete vessels at the base of the pottery layer (right) (figure by authors).

Pod Rovtom

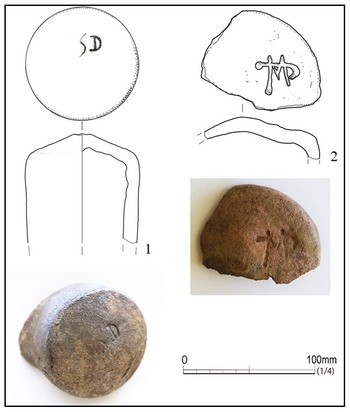

Large pottery fragments were collected in a surface survey of the sloped topography of this site. Lids with inscribed letters, such as ‘SD’ and ‘M/TM’ (Figure 5), were found. Such inscriptions have not been reported at other sites and careful observation of the material is necessary.

Figure 5. Lids with inscriptions found at Pod Rovtom (figure by authors).

Conclusions

At least two types of vessels can be identified from the sherds found at the four sites: those with round-bottomed flask lids or lids with bulging tops (Type A) and those with cylindrical lids (Type B). These two types are also seen in the collections of the Idrija Municipal and Škofja Loka museums. Variation in cross-sectional shape and size of ridges permit further sub-categorisation (Figure 6). The fabric of the vessels also differs in the quantity of sand temper and the presence or absence of mica, which, together with the differences in shape, could indicate differences in age and between pottery workshops.

Figure 6. Schematic chronology of the pottery from sites around Idrija. See Figure 1 for site numbers (figure by authors).

The archaeological study of mercury-producing pottery provides important information on the development of mercury production in the Early Modern period. Our research helps clarify a part of the mercury-production process with the identification of clay seals that prevented the escape of vaporised mercury and of inscribed lids not previously reported. Further analysis of the ceramic chronology and changes in site distribution will help elucidate not only the technological development of mercury production, but also wider issues of landscape use, land ownership and deforestation, that have received attention in recent research on mining history (e.g. Hrubý Reference Hrubý2024). The development of mercury mines was closely linked to the production of precious metals, a factor that both stimulated economic development in the Early Modern period and also had enormous negative impacts on the environment and human health (Pfeifer Reference Pfeifer1989; Bavec et al. Reference Bavec, Biester and Gosar2018). In Idrija, the soil at mercury-production sites still contains mercury, previously estimated at 40 tonnes altogether (Gosar & Čar Reference Gosar and Čar2006). Investigation of these sites is necessary to prevent further spread of mercury in the natural environment, which is vital for both the local community and the management of this World Heritage Site.

Acknowledgements

We thank Danielle Miller-Beland, Claudio Pelloli, Daiichigosei Co. Ltd and Avgusta d.o.o. for their support with the excavations, and Gearh d.o.o. for the geomagnetic survey. Idrija Municipal Museum and Škofja Loka Museum kindly gave us the chance to study their pottery.

Funding statement

The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) partially funded the research.

Author contributions: CRediT Taxonomy

Takamune Kawashima: Conceptualization-Equal, Formal analysis-Equal, Investigation-Equal, Methodology-Equal, Project administration-Lead, Resources-Equal, Writing - original draft-Lead, Writing - review & editing-Equal. Janez Rupnik: Conceptualization-Equal, Data curation-Equal, Funding acquisition-Equal, Investigation-Equal, Methodology-Equal, Project administration-Equal, Resources-Equal, Supervision-Equal, Visualization-Equal, Writing - review & editing-Equal. Junzo Uchiyama: Conceptualization-Equal, Funding acquisition-Equal, Investigation-Equal, Supervision-Equal, Writing - review & editing-Equal. Mark Hudson: Conceptualization-Equal, Formal analysis-Equal, Investigation-Equal, Methodology-Equal, Project administration-Equal, Supervision-Equal, Writing - review & editing-Equal.