According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a disaster is “a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society at any scale due to hazardous events interacting with exposure, vulnerability, and capacity conditions, leading to 1 or more of the following: human, material, economic and environmental losses and impacts.”1 The Guidelines for Evaluation and Research in the “Stein Style” defines a disaster as “serious disruption of the functioning of society, causing widespread human, material or environmental losses which exceed the ability of affected society to cope using only its resources; the result of a vast ecological breakdown in the relations between man and his environment, a serious and sudden event (or slow as in drought) on such a scale that the stricken community needs extraordinary efforts to cope with it, often with outside help or international aid.”2 Otherwise, DM is “a discipline consisting of a combination of studies in emergency health services, emergency medicine, disaster management, and public health.”Reference Ciottone3

Improving communities’ and countries’ resilience and health security requires comprehensive disaster risk management, which involves the health workforce’s preparedness, readiness, and response to disasters.Reference Hung, Mashino and Chan4

Having a trained health care workforce is critical in countries at high risk of disasters, especially in rural areas where specialists may not be available. In these contexts, recent graduates and final-year students are often the first to respond to emergencies,Reference Sreeram, Nair and Rahman5 assisting health care teams in triage, basic life support, and initial stabilization of patients. Their preparedness directly contributes to both hospital readiness—by ensuring a pipeline of competent professionals who can integrate seamlessly into emergency response efforts—and community safety, by extending medical support to underserved populations during crises. Strengthening their disaster medicine training through simulation-based education enhances their ability to function effectively in high-pressure situations, ultimately improving overall emergency response capacity.

Health sciences education aims to improve the preparedness of professionals and the whole health workforce. Virtual Simulation (VS) in deliberate practice programs has proven to be an effective tool for preparing health professionals. It allows them to practice critical skills in a controlled and immersive environment, significantly improving their confidence, knowledge acquisition, and hospital preparedness for disasters.Reference Jung6 Deliberate practice, a key principle in acquiring expert performance using simulation, is understood as “a structured, goal-oriented approach to skill development that emphasizes intentional habit modification, immediate feedback, and iterative refinement to enhance performance.”Reference Ericsson7

In disaster preparedness, adopting a multidisciplinary approach that integrates organizational, human, and technological factors is vital to optimizing the training of health professionals in critical situations.Reference Kim, Poncelet, Lee, Rodríguez, Donner and Trainor8

These areas allow for a better understanding and management of the complexities present in emergencies, highlighting the importance of preparation and the development of response capacities.Reference Hung, Lam and Chow9 Although undergraduate disaster preparedness training increases theoretical knowledge, it does not ensure adequate preparation to act in real scenarios. Hence, integrating clinical simulation into the curriculum becomes essential to provide students with the necessary skills and guarantee an effective response in disaster situations.Reference Hung, Lam and Chow9

VS has shown promising results in enhancing disaster preparedness, confidence, and performance among nursing students.Reference Andreatta, Maslowski and Petty10, Reference Shujuan, Mawpin and Meichan11 Additionally, VS improves disaster response by strengthening decision-making abilities, situational awareness, and coordination in high-stress scenarios, while also fostering interdisciplinary collaboration.Reference Farra, Miller and Timm12 Evidence also suggests that VS positively impacts self-efficacy and preparedness of participants in handling mass casualty incidents after simulation-based training.Reference Padilha, Machado and Ribeiro13 Still, more scientific evidence is needed to understand its long-term effectiveness in real-world disaster response, its role in fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, and its potential impact on improving community safety.Reference Magi, Bambi and Iovino14

The need to understand how VS in all these forms (augmented reality, mixed reality, or computing simulation) has been used to train undergraduate health students in DM led us to our research question: How has VS been implemented as a teaching method in the training of competencies in DM in undergraduate health sciences students?

Methods

The research team comprised 6 researchers from 3 countries (Portugal, The Netherlands, and Chile). Five had training as simulation educators and participated in simulation teaching undergraduate programs, 1 had been serving as part of Médecins sans Frontières and Red Cross in Africa and Middle East, and 1 had been responsible for training programs to prepare health care providers to respond in cases of radiation and chemical accidents. One has been in charge of firefighter preparedness for natural and chemical disasters. The team includes physicians, nurses, and firefighters. All the team members had content expertise related to the modalities of VS analyzed, and 4 had experience conducting scoping reviews. A librarian assisted the team in developing the definitive search strategy.

The research team conducted a preliminary search to identify reviews related to teaching DM in undergraduate settings in the literature. Using the general terms “disaster medicine,” “virtual simulation,” and “undergraduate student,” we searched the Scopus database but found no existing reviews in the literature focused on this population. The existing literature justifies the need for a scoping review. The team followed the 6-step approach described by Mak to conduct Scoping Reviews,Reference Mak and Thomas15 aimed at analyzing various forms of VS used in the undergraduate education of health professionals.

Step 1: Identifying the Research Question

Based on the preliminary literature search, educating undergraduate students is crucial for enhancing health care systems’ and countries’ preparedness to respond effectively to disasters using available resources. Given the potential of VS as a tool for teaching and assessing knowledge and competencies in clinical decision-making within health professions, we formulated the research question: How has VS been implemented as a teaching or assessing method in training DM competencies in undergraduate health students?

Step 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

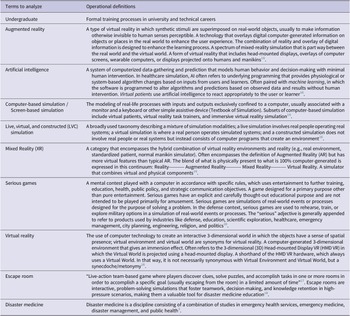

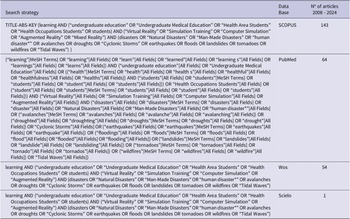

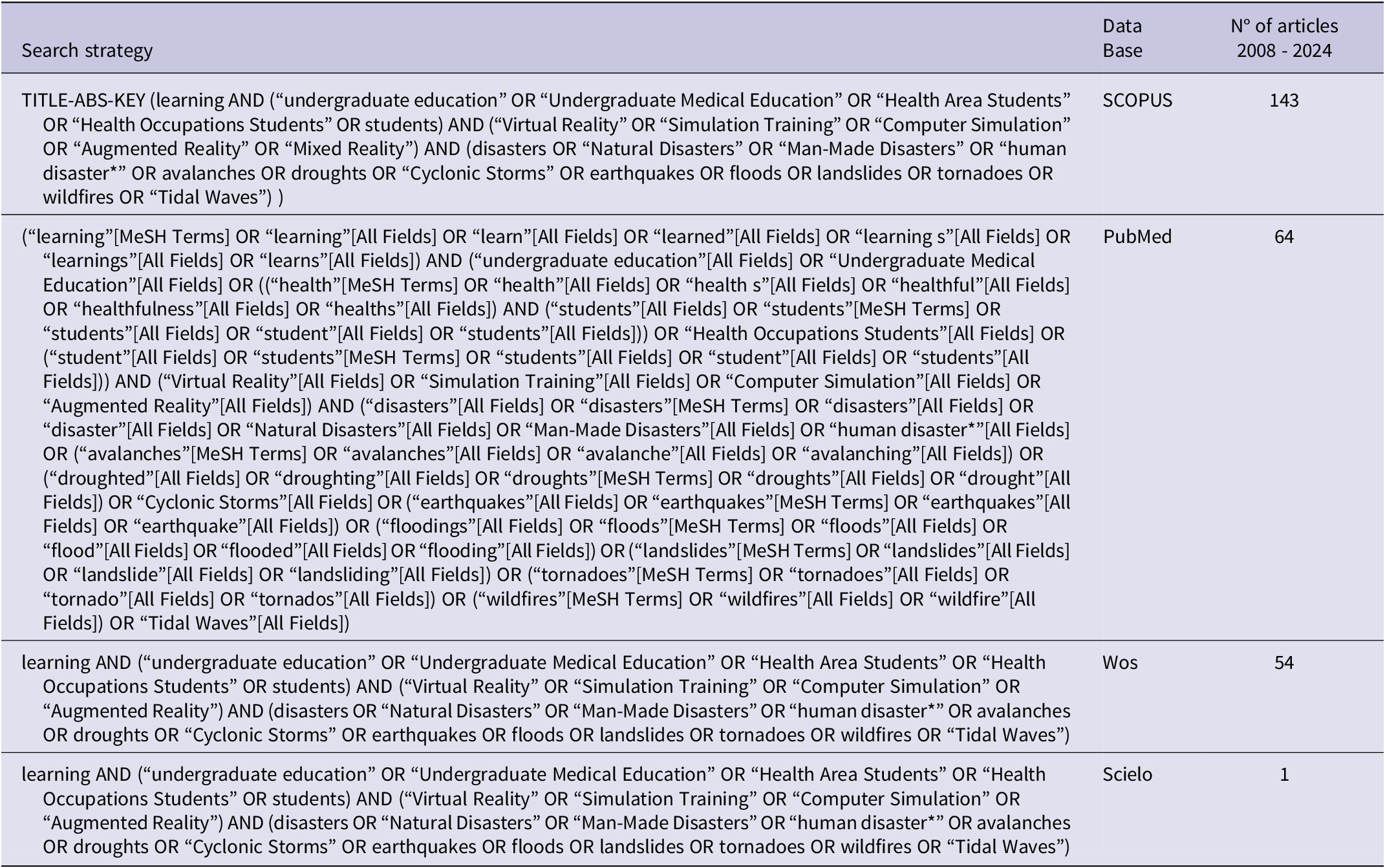

A librarian assisted in developing the search strategy. After 2 meetings dedicated to understanding the operational definition of disaster medicine,Reference Ciottone3 virtual simulation modalities,Reference Lioce, Lopreiato and Downing16 and the research team’s suggestions and considering that the field has specific expressions not covered by Medical Subject Headings, we defined the search terms (Table 1) and the search strategy (Table 2). For the inclusion criteria, we included only articles that report curricular activities using virtual simulation in any of their modalities to teach disaster medicine to undergraduate students. The exclusion criteria considered using any other simulation modality (high fidelity, low fidelity simulation, and simulated patients). No language filter was applied. We searched SCOPUS, WOS, Scielo, and PubMed databases for articles published up to March 2024. This review was not registered with PROSPERO, as the platform does not accept reviews categorized as scoping, literature, or mapping reviews.19

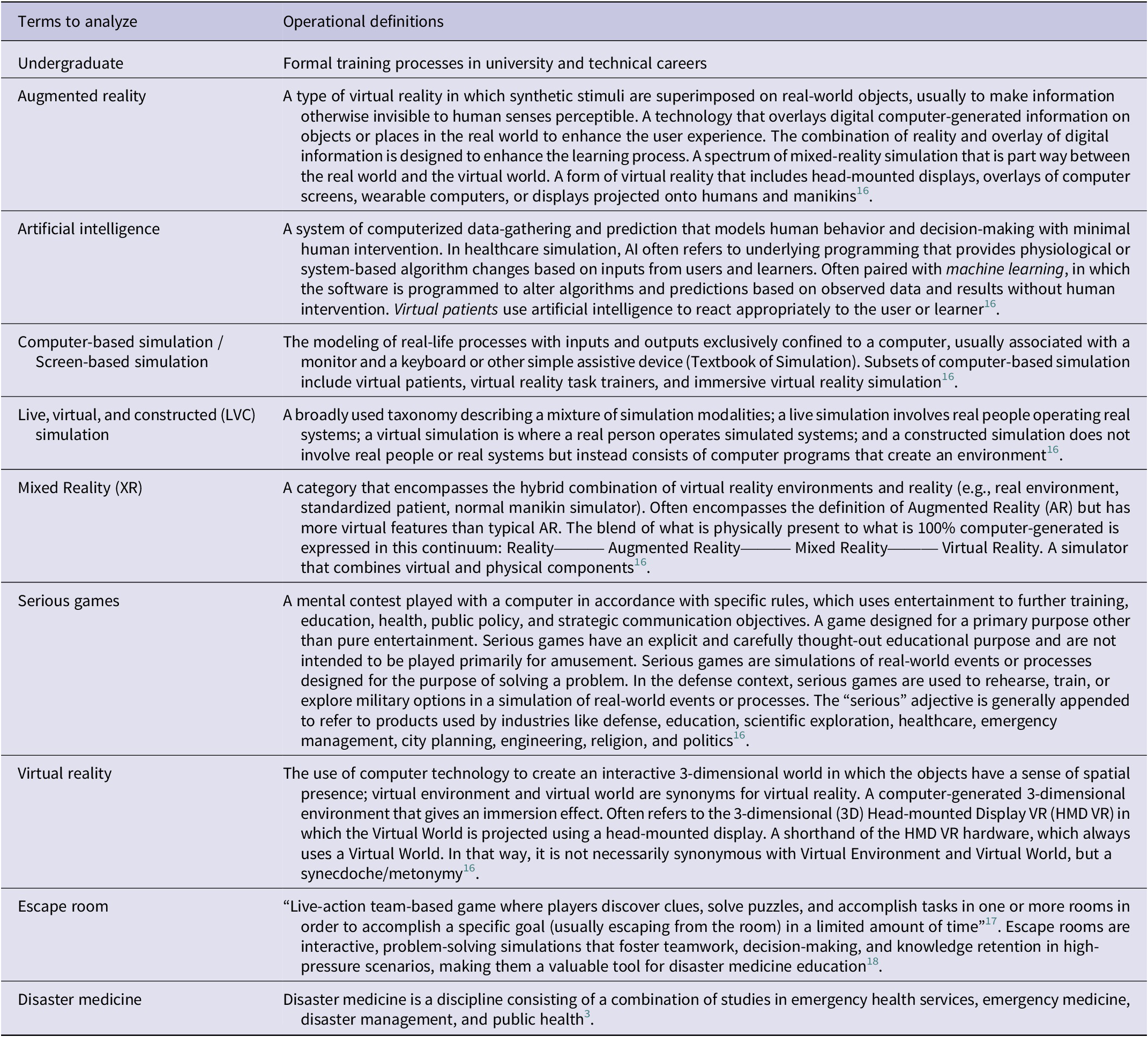

Table 1. Operational definitions for terms used in the literature appraisal

Table 2. Search strategy

Step 3: Selecting Studies to be Included

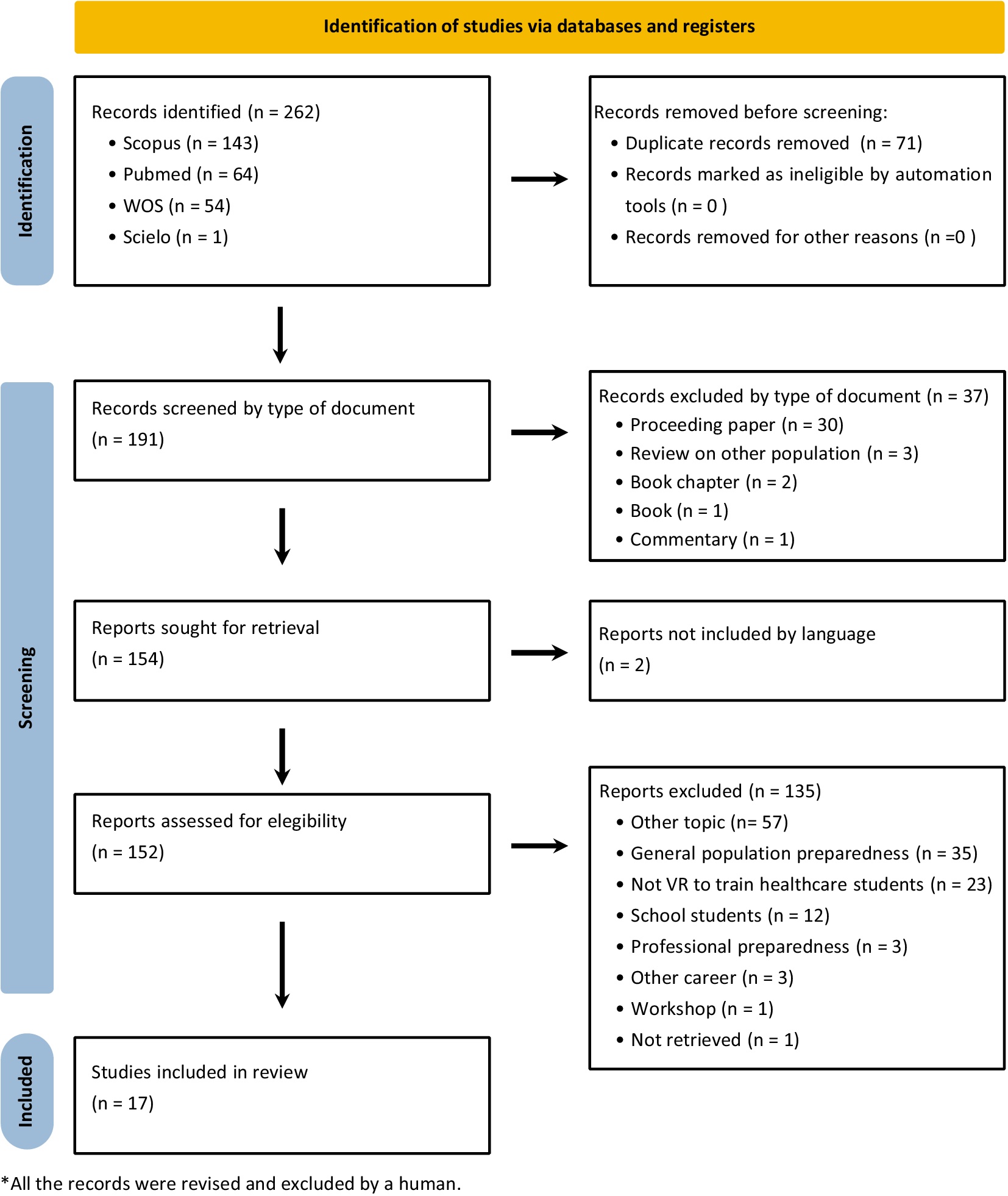

The search strategy led to the extraction of 262 abstracts (143 from Scopus, 64 from PubMed, 54 from WOS, and 1 from Scielo). One researcher (SA) removed duplicates (71), resulting in a corpus of 191 abstracts for the initial review. These titles and abstracts were reviewed and filtered by an expert (SA), eliminating proceeding papers, books, book chapters, commentaries, and articles written in languages not managed by the authors (Chinese and German). Through this process, 39 articles were excluded. A total of 152 abstracts were appraised independently by 2 reviewers (SA, DT) to determine if they met inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria considered articles reporting data from curricular simulation activities involving undergraduate health students and focused on VS training programs implemented until March 2024. Exclusion criteria included non-curricular simulation activities (such as experiences in congresses or workshops), experiences using high fidelity with mannikin, low fidelity or simulated patients, and programs focused on non-undergraduate students and other populations. Dissensus was discussed and agreed upon by both reviewers. Finally, a corpus of 17 articles was included in the analysis phase. The reasons for exclusion are summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Prisma Flow Chart.

Step 4: Charting the Data

The team collaboratively developed the data extraction form (SA, DT, GN, SV) and defined the extraction categories. The automatic bibliometric elements extracted from the databases and included in the analysis were keywords and years. The manually generated extraction categories included the type of institution (university or technical), the career field in which the program was implemented, the course or program level (ranging from 1-7), the number of locations where the program was implemented (within the same or across different institutions), the year, type, and the duration of the intervention (total hours and general timeline), the simulation modality, the organization of the participants, the format of intervention (on-site or remote), the profession of the instructors, and their simulation training and experience.

Given the final sample size, the 17 selected articles were analyzed by 1 expert in the specific field (firefighter, emergency medicine, or nuclear/chemical disasters) and 2 researchers with expertise in simulation. Discrepancies were resolved through a consensus agreement between 2 researchers (SA, DT).

Step 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

The research team conducted numerical and thematic analyses using the data extracted from all papers. At each step, at least 2 independent researchers performed the analysis. Through a reflective and collaborative process, they refined the initial coding based on predefined operational definitions and discussed the relations between the identified themes. The report was prepared following the PRISMA-ScR checklist.Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt20

Step 6: Consulting Stakeholder

To enhance the rigor and relevance of the discussion, the research team consulted a stakeholder expert in critical patient care and simulation training. This expert provided an independent critical review of the findings, offering insights on key discussion points and helping to identify potential gaps in the literature based on their professional experience. Their role was advisory and did not involve direct participation in data collection or analysis. Instead, their input contributed to refining the interpretation of results and ensuring that relevant perspectives from the field were considered.

Results

Bibliometric Characterization

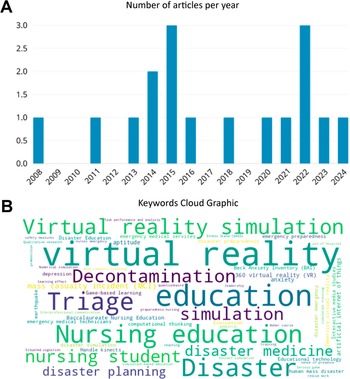

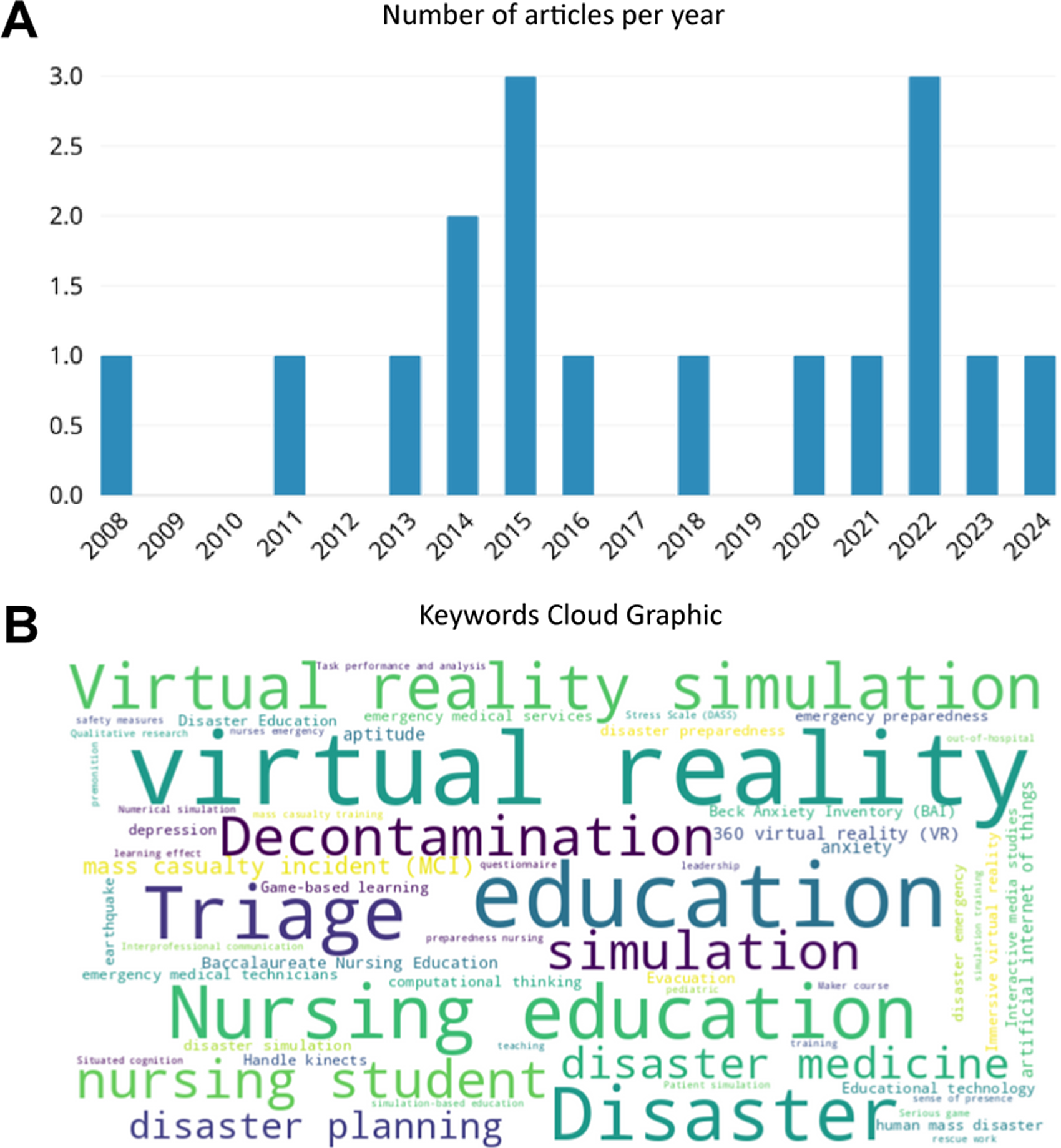

The studies range from 2008-2024, with peak publication years in 2015 and 2022 (17.65% each) and consistent reporting over the last 5 years. Across the 17 articles, 56 different keywords were used, with only 5 appearing in 4-5 articles (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Bibliometric characteristics of the selected articles.

A: Number of articles per year.

B: Keywords Cloud graphic.

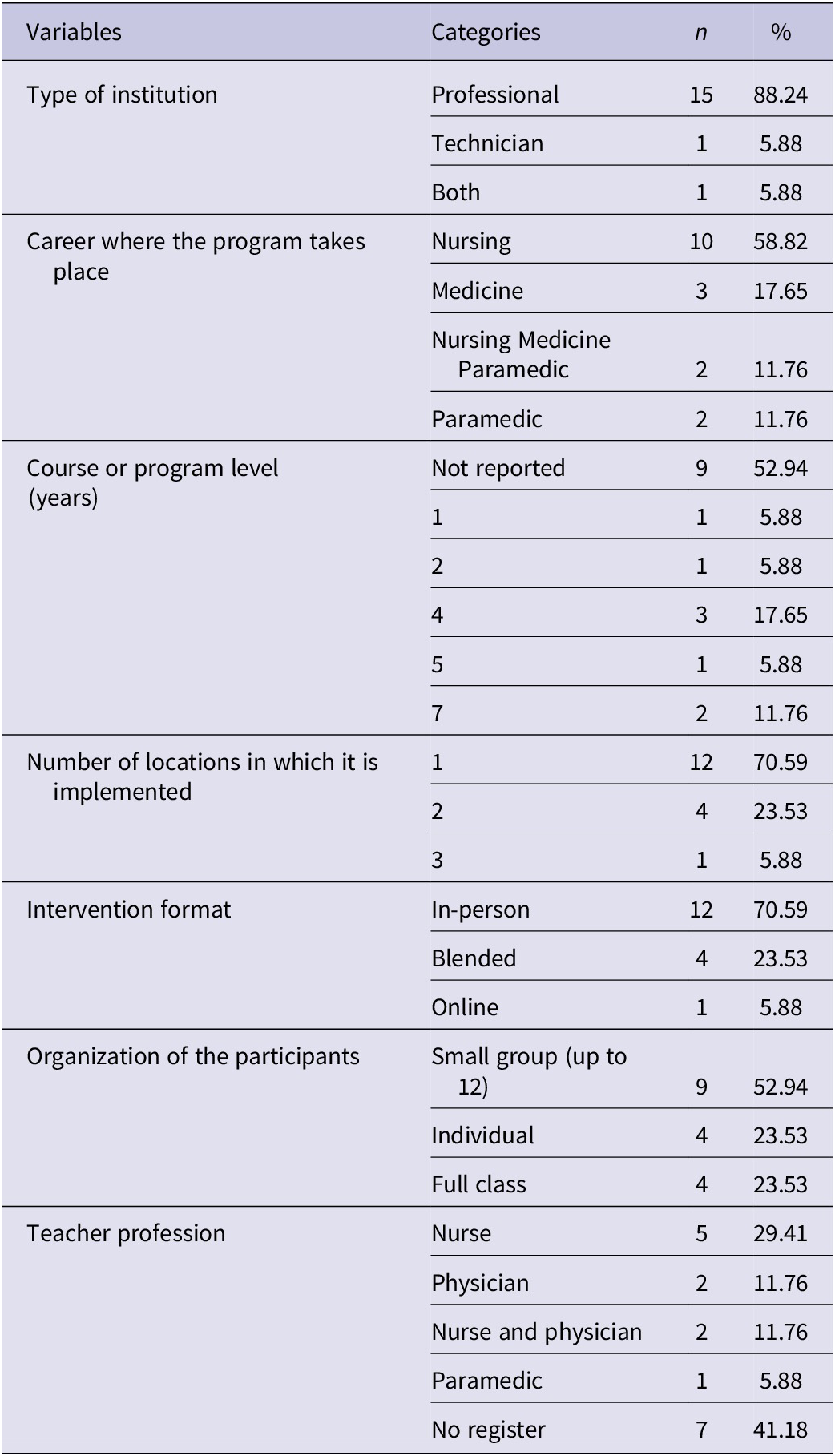

Descriptive characteristics of programs

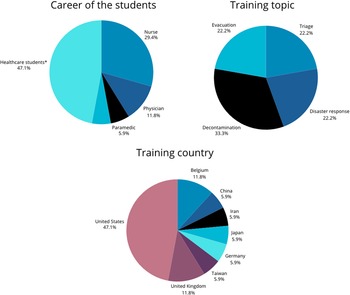

A significant portion of the studies (47.06%) did not report the year of intervention, limiting the ability to analyze temporal trends on implementation. Among the studies that did report the year, an increase in implementation was observed starting in 2015. However, the limited reporting of intervention years restricts the ability to analyze temporal trends. Most interventions were conducted at universities (88.24%), with the majority focusing on nursing programs (58.82%), followed by medical programs (17.65%). Notably, a single institution in the US accounted for 6 reports (35.29%) on decontamination training for nursing students. The remaining studies concentrated on other training areas, including triage (23.53%), disaster preparedness (23.53%), and evacuation (17.65%). The programs were implemented across the US, Europe, and Asia (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Characteristics of the programs implemented.

Most of the interventions (70.59%) were conducted at a single location and delivered face-to-face, with 94.12% of the reports describing 1-time events (single interventions). Various instructional approaches were employed, with 47.06% of the studies incorporating multiple simulation methodologies and 17.65% using Problem-Based Learning, including VS as a teaching tool. Regarding the modality of VS, 82.35% of the reports focused on virtual reality (VR), without components of augmented reality (AR) or mixed reality (MR). However, only 47.06% of the instructors had formal simulation training (Table 3). Four key training areas were identified, and the analysis of these areas is detailed in the following section (Figure 3).

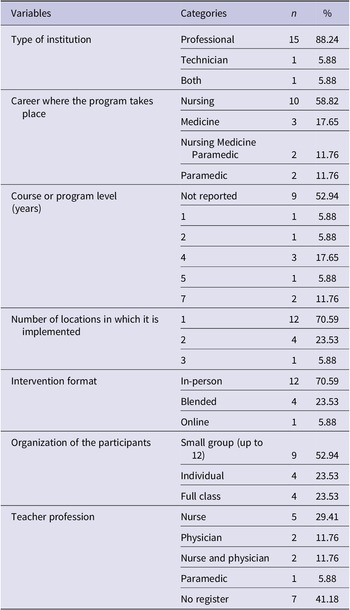

Table 3. Descriptive characteristics of the programs implemented

Triage. In 4 studies focused on triage training (23.53%), VR was used as an innovative educational tool, with different approaches to its implementation. These included pre-selected scenarios,Reference Vincent, Sherstyuk and Burgess21 collaborative creation of simulations,Reference Farra, Nicely and Hodgson22 and comparisons between triage systems.Reference Cone, Serra and Kurland23 The target population was medical,Reference Vincent, Sherstyuk and Burgess21 nursing,Reference Farra, Nicely and Hodgson22 and paramedic students,Reference Cone, Serra and Kurland23, Reference Harada, Suga and Suzuki24 but none of the studies involved interprofessional training. The number of participants reported ranged from 20-Reference Vincent, Sherstyuk and Burgess2170,Reference Harada, Suga and Suzuki24 and the interventions involved triaging between 5-Reference Vincent, Sherstyuk and Burgess2125 victims simultaneously.Reference Cone, Serra and Kurland23 All the courses were conducted in person.

The main findings of these studies indicated that VR training improves participants’ speed, accuracy, and self-efficacyReference Vincent, Sherstyuk and Burgess21, Reference Cone, Serra and Kurland23 and enhances interprofessional communicationReference Farra, Nicely and Hodgson22 through iterative exposure, structured feedback, and enhanced decision-making opportunities.Reference Vincent, Sherstyuk and Burgess21, Reference Cone, Serra and Kurland23, Reference Harada, Suga and Suzuki24 However, the outcomes varied depending on the study design (number of cases included and repetitions) and the VR platform used. Specifically, repeated VR scenarios led to significant reductions in triage completion time,Reference Vincent, Sherstyuk and Burgess21 while structured, algorithm-based training improved triage accuracy and reduced undertriage errors.Reference Cone, Serra and Kurland23 Moreover, platform design and study methodology influenced learning outcomes, with interactive and immersive VR environments fostering greater engagement and skill acquisition.Reference Harada, Suga and Suzuki24 Overall, the studies demonstrate that VR, with lectures and high-fidelity simulation, provides an excellent opportunity to develop triage decision-making skills. However, the effectiveness of VR training depends on factors such as scenario repetition, feedback mechanisms, and the level of immersion provided by the platform.Reference Vincent, Sherstyuk and Burgess21, Reference Harada, Suga and Suzuki24

Disaster preparedness. Four studies used VR simulation to train disaster preparedness (defined by United Nations as “The knowledge and capacities developed by governments, response and recovery organizations, communities and individuals to effectively anticipate, respond to and recover from the impacts of likely, imminent or current disasters”26) but employed different methods. Two studies focused on mass disasters: 1 used full immersive simulation based on a bus accident to assess sense of presence with virtual simulation and correlates that with decision-making and stress during massive disaster,Reference Paquay, Goffoy and Chevalier25 and another utilized 3D simulation in a longitudinal comparative design, focused on assessing changes in knowledge after disaster simulation were the participant’s trained triage, and first aid to victims of radioactive and explosive events.Reference Farra, Miller and Timm12 The remaining studies explored non-technical performance (decision-making styles assessed using the Rational-Experiential Inventory) in controlled environmentsReference Chevalier, Paquay and Goffoy27 and hybrid simulation using web resources.Reference Shannon28 The target populations included only nursing studentsReference Farra, Miller and Timm12, Reference Shannon28 and interprofessional groups of medical, nursing, and paramedic students.Reference Paquay, Goffoy and Chevalier25, Reference Chevalier, Paquay and Goffoy27 Participants ranged from 40-Reference Farra, Miller and Timm1283.Reference Paquay, Goffoy and Chevalier25, Reference Chevalier, Paquay and Goffoy27 The augmented reality interventions featured a single scenario with multiple victims.Reference Paquay, Goffoy and Chevalier25, Reference Chevalier, Paquay and Goffoy27, Reference Shannon28 Overall, VR training improved disaster preparedness performance and non-technical performance, as measured through pre- and post-tests,Reference Farra, Miller and Timm12 performance metrics,Reference Farra, Miller and Timm12 and evaluations of decision-making and teamwork.Reference Chevalier, Paquay and Goffoy27 Self-reported confidence and perceived readiness further supported its effectiveness in enhancing both technical and non-technical competencies.Reference Shannon28 However, immersion in the scenario was not always a decisive factor for performance. On the contrary, perception of the environment and familiarity with the technology significantly influenced the results.Reference Paquay, Goffoy and Chevalier25, Reference Chevalier, Paquay and Goffoy27 Studies using 3D VR demonstrated superior knowledge retention compared to traditional methods.Reference Farra, Miller and Timm12

Evacuation. Three studies focused on the health students’ preparedness to respond to earthquakes and evacuations, with 1 study specifically addressing participants’ psychological responses, measuring anxiety control using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) in a pre-post VS earthquake training.Reference Rajabi, Taghaddos and Zahrai29 The other 2 studies focused on practical learning, such as evacuation management and computational thinking, and assessed knowledge retention using theoretical pre- and post-intervention tests, as well as CPR practical skills.Reference Chen, Lai and Lin30, Reference Hu, Lai and Li31 The target populations were medicalReference Rajabi, Taghaddos and Zahrai29, Reference Chen, Lai and Lin30 and nursing students.Reference Hu, Lai and Li31 Participant numbers ranged between20-Reference Rajabi, Taghaddos and Zahrai29167.Reference Hu, Lai and Li31 These studies compared VR with traditional training methods and found that VR enhanced knowledge retention and practical skills. Topics covered included fire extinguishing, earthquake debris protection and evacuation, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation during evacuations.Reference Hu, Lai and Li31 Participants consistently reported higher satisfaction with VR training, with significant improvements in decision-making in CPR management and self-confidence in their abilities in disaster scenarios, compared with traditional teaching methods.Reference Rajabi, Taghaddos and Zahrai29–Reference Hu, Lai and Li31 VR simulations also improved anxiety control in disaster situations, particularly earthquake training contexts.Reference Rajabi, Taghaddos and Zahrai29

Decontamination. The most represented topic was the task of decontamination, with 6 articles from the same research group focusing on preparing nursing students to select and use appropriate personal protective equipment when caring for patients exposed to biological, chemical, or radiological hazards that pose risks to health care workers.Reference Ulrich, Farra and Smith32–Reference Smith, Farra and Hodgson37 All studies used VR as an educational tool, with immersion and teaching method variations. Some studies compared VR to traditional methodsReference Smith, Farra and Ulrich35 or other simulations,Reference Smith, Farra and Hodgson37 while others explored how different levels of VR immersion affect learning outcomes.Reference Smith, Farra and Ulrich36 One study assessed movements in specific tasks, registering motions and self-efficacy in emergency preparedness competency dimensions using the Emergency Preparedness Information Questionnaire (EPIQ). This tool includes items related to leadership, belonging to the dimension of the Incident Command System, which is considered disaster leadership training.Reference Smith, Farra and Dempsey34 The studies that reported participants ranged between 76-Reference Smith, Farra and Dempsey34197.Reference Smith, Farra and Ulrich36

The studies generally agree that VR enhances student satisfaction and provides an immersive experience. However, results on its effectiveness for long-term performance and retention are mixed. Some studies suggest that VR is superior for retention,Reference Smith, Farra and Ulrich35 while others indicate that traditional methods may still outperform VR regarding immediate post-intervention accuracy.Reference Smith, Farra and Dempsey34 VR simulations also effectively taught leadership skills related to emergency preparedness. Leadership aspects include assessing site safety for oneself, co-workers, and victims during large-scale emergency events (Item 6) and recognizing tasks that should not be delegated to volunteers (Item 8). VR simulation training improves students’ self-confidence in disaster environments.Reference Smith, Farra and Dempsey34

Limitations

Although the research team had content expertise and relevant experience in disaster medicine and simulation, including only 1 reviewer for the initial exclusion of abstracts may have introduced selection bias. Additionally, while the final thematic analysis involved field experts and simulation experts, discrepancies were resolved through consensus rather than blind assessment by multiple reviewers. This approach could have affected the objectivity of the findings. Furthermore, the review excluded non-English studies due to the language limitations of the team, potentially missing insights from non-English-speaking regions, thus limiting the generalizability of the results to these regions. None of the studies analyzed in this review declare that they adhere to deliberate practice principles, which could be considered a limitation. This gap presents an opportunity for future implementations and research.

Discussion

This scoping review has identified a limited number of publications on the use of VS for teaching disaster medicine to undergraduate health sciences students, despite a growing interest in recent years driven by technological advancements and the global shift toward virtual learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic.Reference Salehi, Ballen and Bolander Laksov38

The findings suggest that, while VS shows promise, its implementation has been largely isolated and concentrated in specific regions, mainly focusing on nursing education. Songwathana and Timalsina highlighted the urgent need for training nurses in developing countries, emphasizing the importance of education and training in improving readiness for disaster situations.Reference Songwathana and Timalsina39 Some institutions have acknowledged that technological innovations like VS offer significant potential for advancing nursing education, particularly in disaster preparedness.Reference Ulrich, Farra and Smith32–Reference Smith, Farra and Hodgson37 VS facilitates experiential learning by immersing learners in high-pressure disaster scenarios, allowing for scenario repetition, structured assessments, and immediate feedback, which enhances skill acquisition and decision-making under stress.Reference Jung6, Reference Magi, Bambi and Iovino14 The ability to measure performance through data analytics enables personalized learning pathways and targeted skill reinforcement.Reference Sreeram, Nair and Rahman5 Incorporating these tools into nursing training programs is essential for equipping nurses with the skills and competencies to respond effectively to emergencies and disasters.Reference Tussing, Chesnick and Jackson40

All the studies on triage training suggest that VR can be an effective tool for increasing triage completion speed, accuracy, and self-confidence among participants through scenario repetition and structured feedback.Reference Vincent, Sherstyuk and Burgess21, Reference Cone, Serra and Kurland23, Reference Harada, Suga and Suzuki24 Additionally, VR enhances interprofessional communication by improving coordination, role distribution, and information sharing among health care teams during triage scenarios.Reference Farra, Nicely and Hodgson22 VR has proven effective in teaching various skills to both medicalReference Sattar, Palaniappan and Lokman41 and nursing students,Reference Kim and Park42 particularly by fostering engagement, reinforcing decision-making under pressure, and improving emotional control through immersive, high-stress simulations.

VS has demonstrated benefits in knowledge retention and emotional control under pressure during earthquake evacuation exercises.Reference Rajabi, Taghaddos and Zahrai29, Reference Chen, Lai and Lin30, Reference Hu, Lai and Li31 These positive results are consistent across various types of training, from evacuation management to developing computational thinking skills in emergency contexts. Globally, Emergency Medical Systems are often unprepared for effective responses to major emergencies and disasters.Reference Beyramijam, Farrokhi and Ebadi43 Key strategies for improving hospital disaster response include staff training and collaboration with external partners.Reference Khirekar, Badge and Bandre44 Because students are part of the hospital community, their training should also be integrated into these preparedness strategies.

Decontamination skills were the focus of 6 training programs developed between 2014 and 2022 at a single US institution.Reference Ulrich, Farra and Smith32–Reference Smith, Farra and Hodgson37 Over time, the program has evolved and increased its training capacity, becoming more comprehensive. Managing trauma patients exposed to biological, chemical, or radiological agents is a low-frequency, high-risk scenario requiring specific skills, and VS has emerged as one of the most effective training options for this purpose.Reference Sauter, Krummrey and Hautz45 However, nurse experiences in this area indicate that further efforts are needed to improve training and preparedness.Reference Schieman, Cowles and Hoeve46

Studies generally agree that VR enhances student satisfaction and offers an immersive learning experience. However, the evidence on its long-term effectiveness and retention is mixed. Some research suggests that VR leads to better retention,Reference Smith, Farra and Ulrich35 while other studies indicate that traditional methods may still outperform VR regarding immediate post-intervention accuracy.Reference Smith, Farra and Dempsey34 Additionally, VR simulations have proven effective in teaching leadership skills, boosting students’ confidence in managing disaster scenarios.Reference Smith, Farra and Dempsey34

Some of the early studies in this review emphasize the positive impact of VR on critical skills training and knowledge retention while also noting the technological limitations and high cost of large-scale implementation.Reference Farra, Miller and Timm12 Although these initial studies suggest that VR may not be superior to other methods unless it is well integrated with experiential learning theory,Reference Farra, Miller and Timm12, Reference Shannon28 this perspective evolves. One of the later studies on general disaster preparedness concludes that the perception of the learning environment, including realism and control, is a key factor in the effectiveness of simulation.Reference Farra, Miller and Timm12 While VR has shown promise as an educational tool for disaster preparedness, its superiority over traditional methods depends on several factors. Studies on triage training indicate that VR improves speed, accuracy, and self-efficacy, but its effectiveness varies based on scenario repetition, structured feedback, and platform design.Reference Vincent, Sherstyuk and Burgess21, Reference Cone, Serra and Kurland23, Reference Harada, Suga and Suzuki24 For disaster preparedness, 3D VR simulations demonstrated superior knowledge retention, while familiarity with technology and environmental perception significantly influenced outcomes.Reference Farra, Miller and Timm12, Reference Paquay, Goffoy and Chevalier25, Reference Chevalier, Paquay and Goffoy27 Evacuation training studies highlighted VR’s role in improving anxiety control and decision-making, but practical skill acquisition depended on the training structure.Reference Rajabi, Taghaddos and Zahrai29, Reference Chen, Lai and Lin30, Reference Hu, Lai and Li31 In decontamination training, VR effectively taught leadership and emergency preparedness skills, although traditional methods outperformed VR in immediate post-intervention accuracy.Reference Smith, Farra and Dempsey34-Reference Smith, Farra and Ulrich36

Recent studies show an increase in the number of VS interventions,Reference Harada, Suga and Suzuki24, Reference Paquay, Goffoy and Chevalier25, Reference Chevalier, Paquay and Goffoy27, Reference Rajabi, Taghaddos and Zahrai29 participants,Reference Smith, Farra and Ulrich36 and the adoption of interprofessional formats in disaster education.Reference Paquay, Goffoy and Chevalier25, Reference Chevalier, Paquay and Goffoy27 This suggests an expanding interest in VS applications, likely driven by technological advancements. However, the literature remains limited and lacks longitudinal studies assessing long-term effectiveness and standardized implementation. While VS presents an opportunity to enhance disaster preparedness training, further research is needed to confirm its impact and scalability across educational settings.

Our results underscore the importance of expanding the scope and consistency of these educational interventions. Previous studies have shown that the effectiveness of simulation in improving technical and decision-making skills depends on the use of deliberate practice programs.Reference McGaghie, Barsuk and Wayne47 However, none of the studies analyzed in this review implemented these principles, which could be considered a limitation. This gap presents an opportunity for future implementations and research.

A recent review found that in disaster-prone countries, nurses often lack adequate knowledge and skills to respond to critical situations, including emotional relief during disasters.Reference Labrague and Hammad48 Despite this, there is still a significant gap in integrating disaster medicine training at the undergraduate level, particularly in disaster-prone countries. Strengthening preparedness among professionals, health care students, first responders—including firefighters—and civilian volunteers is crucial for improving coordinated disaster response and emergency medical care to improve community safety. Virtual simulation (VS) has emerged as an effective tool to bridge this gap by providing immersive, risk-free training environments that enhance decision-making, communication, and teamwork,Reference Farra, Nicely and Hodgson22, Reference Smith, Farra and Dempsey34 and specific skillsReference Vincent, Sherstyuk and Burgess21, Reference Cone, Serra and Kurland23, Reference Harada, Suga and Suzuki24 in undergraduate students, and it could be extensive for other civilians. This review focuses exclusively on undergraduate health care students’ training for disaster response, with no data on firefighters, volunteers, or civilians. However, health care students often serve as volunteers in emergencies, playing a critical role in disaster response efforts. Their training is not only essential for professional readiness but also for strengthening the broader response ecosystem, as they act as a vital link between medical teams and civil society. Large-scale mass casualty simulations have demonstrated valuable lessons in disaster response, reinforcing the role of simulation-based training in strengthening community preparedness.Reference Winters, Lund and Sylvester49

The Organization of American Firefighters, which represents 13 countries and, through them, more than 1.5 million volunteers, paid, military, and police firefighters, is actively working on implementing and updating its training curriculum for firefighters’ training by incorporating VR technology for specific tasks such as victim search and rescue.Reference Ríos Jerez, Bonet Papell and López Morales50 One opportunity to expand the use of VS is to use the same resources to train firefighters and students in high-pressure situations,Reference Farra, Miller and Timm12 or to practice complex scenarios repeatedly, improving their performance and response capabilities during large-scale emergencies.Reference Chevalier, Paquay and Goffoy27 Civil society plays a crucial role in disaster response, and VS has the potential to enhance community-based training by providing scalable, immersive learning experiences, to respond effectively.Reference Shannon28 The Community Emergency Response Teams (CERT) program, developed by the Los Angeles Fire Department, analyzed the participation of untrained volunteers in the 1985 Mexico earthquake, where untrained volunteers rescued 700 people but tragically lost 100 of their own during the rescue efforts.Reference Flint and Brennan51 In collaboration with the Emergency Management Institute of the Federal Emergency Management Agency of the United States, CERT designed a training program for civilians focused on disaster-first responses, including the training of CERT instructors. The program includes mass casualty events and rescue simulations, though it has not yet incorporated VS as a training tool.Reference Nicholson17 Given its scalability and accessibility, VS could be a valuable complement to CERT training, enabling broader participation and standardized disaster preparedness experiences. By immersing students in realistic, high-pressure scenarios, VS helps cultivate critical thinking and decision-making - key skills for health care professionals in stressful situations. Integrating VS into community disaster training could optimize costs, enhance engagement, and improve overall emergency response capabilities on a larger scale.

As health care systems face growing challenges, particularly in natural disasters and public health emergencies, the need for effective training solutions like VS becomes even more apparent. This approach underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary framework in disaster preparedness. Ultimately, incorporating VS into training not only strengthens health care teams but also enhances disaster response capacity by integrating undergraduate students into high-pressure realistic scenarios.Reference Jung6 In many countries, final-year nursing and medical students actively engage in emergency care, playing crucial roles in triage and basic life support.Reference Hung, Lam and Chow9 Moreover, comparisons with the training of professional nurses and physician residents suggest that VS facilitates the early acquisition of critical competencies, supporting a smoother transition into effective clinical practice.Reference Magi, Bambi and Iovino14

Technological advancements, particularly VS, offer significant potential for improving the preparedness of health care professionals for disaster scenarios. Integrating such innovative tools into disaster response training frameworks is essential to enhance the capacity of health care workers to manage emergencies more effectively.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this scoping review highlights the increasing use of VS in disaster medicine education for undergraduate health sciences students, as reflected in the rising number of interventions, participants, and adoption of online or blended training formats. Despite its promise, VS adoption is still limited to certain regions and mainly focuses on nursing education. Integrating VS into disaster preparedness training is particularly crucial for developing countries, where health care professionals are often underprepared for emergency response. While studies demonstrate the effectiveness of VS in improving triage decision-making, anxiety control, and practical disaster response skills, its effectiveness depends on factors such as scenario repetition, structured feedback, and platform design, and challenges such as high implementation costs and the absence of deliberate practice-based programs remain.

The authors suggest that expanding VS to include a broader range of health profession students and interdisciplinary settings could improve preparedness and optimize resource usage. Virtual simulations offer a valuable opportunity to develop technical skills, critical thinking, and resilience in health care teams by immersing students in realistic, high-pressure scenarios. While resilience is a broad concept, our findings suggest that VS contributes to psychological preparedness by improving anxiety control, self-confidence, and performance under pressure, as evidenced by studies assessing anxiety management in earthquake training scenarios. Future implementations should incorporate deliberate practice principles and extend to non-health care first responders to fully harness its potential, creating a comprehensive and cost-effective disaster preparedness strategy.

Author contribution

D.T. and S.A. developed the study ideas and formulated research goals. D.T., S.A., G.N. S.V., E.H. designed the methodology and created models. S.A. handled programming, software development, implementation, and testing of code components. All authors contributed to performing experiments and data collection. D.T., S.V., and S.A. provided study materials, reagents, samples, and analysis tools. D.T., S.A., S.V. managed data annotation, cleaning, and maintenance. All authors were involved in drafting the initial manuscript and in critical review and revision. S.A. was responsible for data visualization. D.T. and S.A. oversaw research planning and execution, including mentoring and coordination.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Claudia Martinich, Reference Librarian for Clinical Fields at Universidad San Sebastián, Chile.

Competing interests

Authors 1 and 3 are employed at Unidad de Simulación e Innovación en Salud, Universidad San Sebastián, Chile.

Author 2 is employed by Universidad del Desarrollo.

Author 4 is employed at Serviço de Anestesiologia, Unidade Local de Saúde de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro (ULSTMAD) and Centro de Simulação Interprofissional de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro (iSIMTAD).

Author 5 is employed at the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).