Introduction

On March 25th, 2020, the heads of nine European Union (EU) governments sent a collective missive to European Council President Charles Michel. Its content was premonitory: they requested the Union to rapidly engage in common debt issuance to face what they described as the ‘extraordinary’, ‘unprecedented’, and ‘unique’ threat posed by the pandemic (Wilmès et al., Reference Wilmès, Macron and Mitsotakis2020). The ability of these countries to coalesce around these proposals contrasts strongly with the experience of the euro crisis, in which coordination amongst debtor countries was strikingly limited. More than establishing a causal link between this coalition and the ultimate outcome of a new recovery facility funded through common debt in the EU (Ladi and Tsarouhas, Reference Ladi and Tsarouhas2020; Baccaro et al., Reference Baccaro, Bremer and Neimanns2023; Bokhorst and Corti, Reference Bokhorst and Corti2024), this paper takes a broader interest on the politics of interstate coalition formation in the EU and investigates both the conditions for their constitution and their implications for EU economic governance.

Recent literature has pointed out the relevance of crisis construal in the economic responses to the pandemic in Europe (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Ausserladscheider and Sparkes2023; Crespy and Schramm, Reference Crespy and Schramm2024). Another stream of the literature has shown the significance of interstate coalitions in negotiations related to EU economic governance reforms (Fabbrini, Reference Fabbrini2023; Schoeller, Reference Schoeller2021, Reference Schoeller2022; Verdun, Reference Verdun2022). Yet, puzzles remain concerning the processes through which these coalitions are formed and how they articulate common interpretations of crises and shared policy stances. The drivers of these coalitions tend to be associated with shared structural conditions, often along a creditor-debtor cleavage that remained salient from the management of the euro crisis (Matthijs and McNamara, Reference Matthijs and McNamara2015; Moreira Ramalho et al., Reference Crespy, Massart and Moreira Ramalho2024). Creditor countries are expected to converge in their positions – as are debtor countries. This however does not hold when we place this specific crisis in comparative, historical perspective. The euro crisis did not lead to what Fabbrini (Reference Fabbrini2023: 64) termed a ‘solidarity coalition’ amongst southern countries, as the pandemic did. The group of debtor countries was a non-coalition – when not an actively anti-coalition.

During the euro crisis, reigning ideas about contagion propelled each troubled state to distance itself from neighbours, rather than to converge on common demands (Moreira Ramalho, Reference Moreira Ramalho2025). Peripheral countries faced what Mair (Reference Mair, Schäfer and Streeck2013: 159–162) described as a ‘responsibility-responsiveness’ dilemma in economic governance that pitted external commitments against domestic demands (see also Laffan, Reference Laffan2014). This led debtor countries towards a centrifugal process of anti-coalition in which governments sought a discursive, if not economic, dissociation from one another – perhaps best illustrated in the trope ‘We are not Greece’ (Brereton, Reference Brereton2010). On the other hand, the notion of ‘responsibility’ that emerged with the pandemic crisis seems to have operated a rather centripetal effect in these countries. These strategic shifts occurred against the backdrop of relatively stable national ‘preferences’ on EU economic governance across the two crises (Truchlewski and Schelkle, Reference Truchlewski and Schelkle2024). The emergence of a ‘solidarity coalition’ calling for a ‘coronabond’ highlights the contingent character of interstate coalitions, and the critical role of ideas about ‘responsible’ economic government, in processes of crisis-led institutional reform in the EU (Crespy, Moreira Ramalho and Schmidt, Reference Crespy, Moreira Ramalho and Schmidt2024).

This paper analyses the emergence of this coalition through a focus on a series of central analytical questions. How were the interests of these governments formed and articulated discursively? How did the coalition emerge? How was the letter produced? In order to retrace the formation of the coalition and its activities, the empirical strategy comprises two methods. Firstly, a series of semi-structured interviews with European Council Sherpas involved both in the negotiation and formulation of the letter, as well as more long-term negotiations of reforms in EU economic governance. Secondly, the collection and analysis of policy documents and public statements produced by these governments, namely around the Med7 summits that regularly gathered the heads of government of the European South from 2016 onwards.

The paper makes two central contributions. At the theoretical level, through a dialogue with mainstream integration theory, it extends the burgeoning literature on the role and relevance of interstate coalitions in EU economic governance reform. Empirically, the paper traces the understudied processes of coalition (and anti-coalition) formation in the European South and the ways in which these governments have developed agency in the political contention around what ‘responsible’ economic government imposes in the EU. It highlights the long-term consolidation of a coordinated reform agenda in the post-euro crisis period, the importance of entrepreneurship by larger member states (first Italy, then France), and the strategic importance of diplomatic bridges beyond the so-called ‘club Med’. Overall, the paper adds a critical piece to the larger interrogations that still animate our debates on the persistent crises of EU economic governance and the impact of the pandemic in their resolution (Buti and Fabbrini, Reference Buti and Fabbrini2023; Jabko, Reference Jabko2019; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2020b).

The argument is structured as follows. The next section presents a general analytical framework. A short methodological note follows. The empirical analysis retraces how debtor countries progressively coalesced into a coordinated political bloc, in the aftermath of the euro crisis. This analysis is complemented by an in-depth account of the initial stages of the pandemic, when the nine countries of the ‘solidarity coalition’ publicly voiced their support for shared debt issuance. The final section concludes.

Interstate coalitions and EU economic governance

The role of interstate coalitions in EU negotiation processes, especially around economic governance, has been the object of mounting scholarly attention (Ekman et al., Reference Ekman, Stahl and Ryner2025; Fabbrini, Reference Fabbrini2023; Schoeller, Reference Schoeller2021, Reference Schoeller2022; Schoeller and Falkner, Reference Schoeller and Falkner2022; Truchlewski and Schelkle, Reference Truchlewski and Schelkle2024; Verdun, Reference Verdun2022). This literature shares important affinities with Liberal Intergovernmentalism (LI), as it undoubtedly sees member states and their negotiations as a – if not the – driver of decision-making at the EU level. Most of this literature is focused precisely on how these different countries bargain their way through European Councils, Council meetings, or the Eurogroup, and sees those bargaining processes as the cornerstone of whatever route the EU or the EMU take.

Yet, interstate coalitions sit oddly in traditional theories of European integration. They are largely trivial within the framework of neo-functionalism, as the structural constraints of interdependence are seen as the driving force of supranational delegation of authority over sectoral policies. Similarly, the post-functionalist turn emphasizes different drivers of ‘constrained’ integration, namely in mass publics and wide politicization of the EU as a polity (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009). And although intergovernmentalist approaches give greater centrality to member states and their dealings, more or less stable (and opposing) coalitions remain anomalous. For new intergovernmentalists, the Council emerges as an ‘intermediate sphere’ of deliberative consensus-building (Bickerton et al., Reference Bickerton, Hodson and Puetter2015; van Middelaar, Reference van Middelaar2013). For liberal intergovernmentalists, on the other hand, negotiations (or ‘choices’) are studied as ‘static’ (Moravcsik, Reference Moravcsik1998, Reference Moravcsik2018). Each member state comes to the negotiation table with a position that is determined by domestic social preferences. The more ‘issue-specific’ the matter at hand, the clearer the social pressure group that will shape the state’s stance can be. Ekman et al. (Reference Ekman, Stahl and Ryner2025: 791-793) refer to this as the ‘Moravcsik channel’.

Yet, in this world of ‘discrete games’ seen through a rationalistic lens (see Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2015: 184–188), country coalitions formed and sustained in time, in which positions are adopted in and through the articulation of compromises, remain in a theoretical blind spot. These limitations are in part anticipated by LI scholars. The euro and general rules around economic governance have long posed structural challenges to the theory (Moravcsik, Reference Moravcsik2018: 1651, 1667): far from being ‘issue-specific’ and thus affecting a delimited set of actors, these questions have diffuse, all-encompassing, distributional consequences; processes of reconfiguration tend to be recurring and incremental, when not occurring ‘by stealth’ (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2016); they generate and emerge from long, protracted crises in which ‘lessons’ seem to be hard to learn (Matthijs, Reference Matthijs2020); and ultimately they largely depend on shifting consensus and paradigms in economic ideas, as well as on evolving normative discourses around cooperation and solidarity (Miró, Reference Miró2022).

The recent literature on interstate coalitions in the EU provides a stimulating framework to better understand changes in its economic governance. These contributions have mostly focused on how northern ‘small states’ have coalesced towards common positions, typically in order to manage German or Franco-German power (Howarth and Schild, Reference Howarth and Schild2022; Schoeller, Reference Schoeller2018, Reference Schoeller2022). Usually through empirical strategies aiming towards the production of in-depth empirical analysis of the motivations and discourses of actors (discourse analysis, elite interviewing, process-tracing), this body of work has greatly illuminated how the so-called ‘New Hanseatic League’ or the ‘Frugal Four’ coalitions were formed, how they sustained their cooperation, and how they acted collectively.

From these works, we know that Brexit led Northern countries to fear a structural shift away from free trade and limited economic integration, which drove them to make their ties closer. The fear that Germany would move in the French direction over economic governance, especially after the Meseberg declaration of 2018 (Howarth and Schild, Reference Howarth and Schild2022), further motivated these countries to take collective public stances against a deeper fiscal union. The formation of these coalitions heavily depended on the role of ‘entrepreneur’ states, namely the Netherlands, and was nourished by regular informal meetings, often around official EU business. Finally, these coalitions mobilize a mix of collective strategies of bargaining and persuasion (i.e., framing, going public). In all of this, a key instrument of this type of coalition, and usually their defining document, is the public letter, memo, or ‘non-paper’.

The wealth of empirical and theoretical knowledge that has been accumulated about the ‘Hansa’ or the ‘Frugals’ has, however, no parallel when it comes to the southern coalition in the context of the EU response to the COVID-19 pandemic. No systematic empirical assessments of the formation and workings of this coalition have emerged. This is all the more puzzling given that the strategic alignment of these countries’ governments during the pandemic contrasted in important ways with their interactions during the euro crisis.

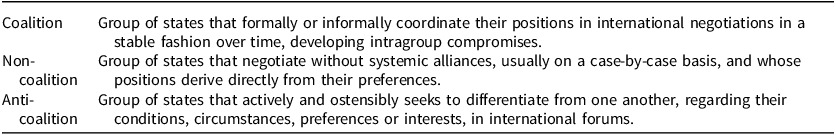

During the euro crisis, the highly salient debtor-creditor cleavage was grounded in structural differences, as well as in a dominant crisis narrative according to which the predicament of debtor countries resulted from lack of ‘responsibility’ in economic policymaking, namely a misalignment between national policies and the ‘rules’ of EU economic governance (Laffan, Reference Laffan2014; Matthijs and McNamara, Reference Matthijs and McNamara2015; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2020a). In this context, Mair (Reference Mair, Schäfer and Streeck2013) famously posited that the euro crisis generated a dilemma for governments, stuck between the imperatives of responsibility and responsiveness. Though this has led to general assumptions regarding a southern ‘bloc’ in debates over EU reform, the countries most affected by the euro crisis did not coalesce around a coordinated agenda. Quite to the contrary, each of these governments was keen on presenting its economic situation as fundamentally different from other crisis countries’, as in-depth studies of the management of the euro crisis in the European South have established (Moreira Ramalho, Reference Moreira Ramalho2025; Moury et al., Reference Moury, Ladi, Cardoso and Gago2021). These works have shown how these countries, far from a coalition, could be described as an anti-coalition (see Table 1). The imperatives of responsibility and credibility at the height of the sovereign debt crises pushed each government to publicly state what they saw as a clear distance from each other.

Table 1. Conceptual framework

The striking puzzle of the ‘solidarity coalition’ seems not to be that it eventually took shape, as structuralist assumptions would lead to the reasonable expectation that these countries, sharing similar stakes in EU economic governance debates, would coalesce. The striking observation is that these governments did not always work in concerted fashion. Interstate coalitions thus cannot be reduced to structural positions or even stable ‘preferences’ (Kassim et al., Reference Kassim, Saurugger and Puetter2020; Truchlewski and Schelkle, Reference Truchlewski and Schelkle2024). Understanding these coalitions requires in-depth empirical assessment of the processes that led these countries to publicly join efforts. The contingent character of these coalitions implies that, rather than focusing on ‘structural’ or ‘material’ conditions as exogenous factors, it is necessary to capture how actors themselves understand – indeed, construct – such conditions (Hay, Reference Hay2016; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2008). This allows for a better grasp of the constitution of preferences regarding policy outcomes, of strategies of interstate coalition-building within the EU, and ultimately of the emergence of dominant ideas regarding adequate pathways of economic governance and reform in response to crises (Crespy, Moreira Ramalho and Schmidt, Reference Crespy, Moreira Ramalho and Schmidt2024).

This paper thus aims to contribute to the literature on coalition-building and preference formation in EU integration processes. It does so by anchoring the analysis on the formation of the ‘solidarity coalition’ of EU governments (Belgium, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Slovenia, and Spain) that co-signed a public letter in March 2020 calling for the mutualization of new debt to tackle the economic consequences of the pandemic. The paper explores how, beyond stable structural conditions, the formation of interstate coalitions is shaped by (and shapes) the ever-contested normative hierarchies of ‘good’ and ‘responsible’ economic government as well as the fundamental principles guiding the equally contested framework of economic governance in the EU (Jabko, Reference Jabko2019; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2020a).

Method

The empirical strategy of the paper aims to retrace the process through which the ‘solidarity coalition’ was formed. It follows the methods found in the literature on interstate coalition-making in the EU (Schoeller, Reference Schoeller2022; Schoeller and Falkner, Reference Schoeller and Falkner2022; Verdun, Reference Verdun2022). Using both primary and secondary sources, the paper traces how these countries moved from an anti-coalition at the height of the euro crisis into a coalition by the time of the pandemic outbreak in 2020. This is done through the analysis of public declarations on EU economic governance and integration, especially formulated around summits of the Med7, formed in 2016. The results of this primary empirical investigation are interpreted considering the extensive literature on the politics and the political economy on the euro crisis and on European economic governance more broadly.

The paper further proceeds to an empirical investigation of how the coalition around ‘coronabonds’ was formed in March 2020. The analysis is based on a set of semi-structured interviews with national actors directly involved in the negotiation of the letter. Initial exploratory contacts with government officials made it clear that the EU Sherpas to the European Council of each government in March 2020 were central to this process. This network of diplomats took the initiative, carried out the talks, and co-wrote the document.

The field of potential interviewees was thus restricted and of especially difficult access. Most of the Sherpas at the time of the pandemic carried on occupying positions of high responsibility, namely in international diplomacy and government. The fieldwork included 7 separate, semi-structured interviews with a total of 8 individuals, including 5 out of the 9 Sherpas involved in the negotiation of the letter. One interview was conducted with two high-level civil servants from one of the countries, and it allowed for useful background knowledge, but also to confirm that the negotiations were done at the ‘political’ level via the Sherpas. One interview was given by a former Sherpa in the period prior to the pandemic. The interviews explored the processes and practices of coalition-making at the EU level, with a specific focus on the specific process leading to the coalition around ‘coronabonds’, including where the initiative to voice collective demands came from; how the letter was written and negotiated; what the antecedents to the coalition were; how countries coalesced (and why these nine); and what explains switching or overlapping coalitions (e.g., Ireland was both a member of the New Hanseatic League and of the solidarity coalition).

To safeguard anonymity – a condition for the securing of the interviews – the paper does not identify the interviewees in any way. The interviews took place between November 2022 and January 2025, in-person (3) and via videoconference (4) with an average duration of roughly one hour.

The realignment of the southern periphery

From centrifugal ‘confidence’…

During the euro crisis, the different ‘debtor’ countries formed what we describe as an ‘anti-coalition’ (Table 1). As the Greek government headed by Papandreou established that a ‘home-made’ crisis was unfolding, in which a mix of unreliable economic data and excessive public spending eroded the country’s trustworthiness (Karyotis and Gerodimos, Reference Karyotis and Gerodimos2015), neighbouring countries were fast in their distancing. Governments in both Portugal and Spain repeatedly insisted on the differences between their own economic situation and the deeper Greek predicament – and when international actors suggested an overall shared problem, opposing reactions from these governments were nearly immediate (Moreira Ramalho, Reference Moreira Ramalho2025: 74–80).

This game of distinction was characteristic of the euro crisis for several years, as recounted in journalistic work and in memoirs (Boland, Reference Boland2015; Brereton, Reference Brereton2010; Varoufakis, Reference Varoufakis2017). It was important, as it were, not to be Greece – even if in time a greater consensus was built on the structural, systemic challenges of the EMU that, at least, exacerbated country-specific economic difficulties (Hall, Reference Hall2014). This distancing was part and parcel of the general, reigning logic of a dichotomy between responsible and responsive government at the time: enacting pre-emptive austerity whilst attempting to discursively perform economic stability (or, maintaining ‘confidence’) were central pillars of what was deemed to be the imperative of responsibility (Crespy, Moreira Ramalho and Schmidt, Reference Crespy, Moreira Ramalho and Schmidt2024; Mair, Reference Mair, Schäfer and Streeck2013; Moreira Ramalho, Reference Moreira Ramalho2020).

The distancing, however, eroded as it inexorably failed. One after the other, southern countries fell under some sort of EU economic support, from explicit bailouts to implicit conditionality, with varying degrees of domestic political consent (Moury et al., Reference Moury, Ladi, Cardoso and Gago2021; Sacchi, Reference Sacchi2016). Forceful opposition from a southern government only occurred in 2015, when SYRIZA won the Greek general elections. The 8-month conflict that followed made the fault lines of EMU governance more visible, in a moment in which the ‘Troika’ bailouts were highly contested – even in the EU institutions. European Commission President Juncker publicly stated that the EU had ‘sinned’ against the Greek people (Juncker, Reference Juncker2015). Yet, despite the high level of politicization, the Greek government ultimately failed to challenge the terms of financial assistance and became increasingly isolated in negotiations – a process perhaps epitomized by the expulsion of Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis from the Eurogroup meeting of June 27th, 2015. The Greek government eventually adopted a third bailout. The remaining peripheral countries had just left or were on the way out from their own bailouts.

The clash over the Greek economic situation revealed that other crisis countries were not publicly aligned with the demands of the Greek government. Portugal and Spain directly opposed any softening of the bailout terms. These centre-right governments had implemented an austerity agenda since the early stages of the euro crisis, and any success achieved by SYRIZA could potentially nourish the rising aspirations of the left-wing opposition in the two countries (Carvalho, Reference Carvalho2022). The centre-left governments in Italy and France at the time also opposed Greece’s demands. The crisis of 2015 revealed the divisions across member states, but also highlighted cleavages within, as Athens became an arena for international political performance. Ahead of the January 2015 election in Greece, political leaders from neighbouring countries in the European South publicly sided with Greek candidates along ideological lines. The stabilization that ensued with the adoption of the third Greek bailout, with the end of other countries’ bailouts, and several shifts in government created the conditions for a realignment of these governments regarding EU economic reform.

To centripetal ‘responsibility’

In the summer of 2016, the Greek government hosted in Athens the first Summit of the Southern European Countries of the EU – often referred to as Med7. It was the first time since the euro crisis that the heads of state of southern Europe gathered to coordinate their stances on central EU debates, namely regarding economic governance reform. Since the 2016 summit in Athens, the heads of government of these seven countries (Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal, and Spain) have met in a rather ceremonious manner more than once a year. The Med7 – turned Med9 in 2021 when Slovenia and Croatia joined the club – have managed to align their positions on several important EU policy areas as the communiqués have made clear throughout the years.Footnote 1

The coordinated formation of policy stances by these governments over the years facilitated their alignment in the very early stages of the pandemic. As put by an interviewee (#7):

It’s the foundation, and it’s the humus. We didn’t know, of course—once again—that there would be this crisis, this need to switch into emergency mode, almost this opportunity to switch into emergency mode as well. But there you have it, that’s part of historical circumstances: plenty of drawbacks to this crisis, but a few benefits too. But yes, it’s the humus, if I may put it that way.

Whereas ten years prior, these countries were quick to differentiate their economic situation from one another, this time around they acted as a bloc. And a rather relevant one: the combined GDP of the coalition was more than half of that of the EMU’s, twice the German, and – in a mix of material and symbolic power – the three largest economies after Germany were clearly aligned in one proposal. Indeed, this was not so much a coalition of small countries as it was a coalition of member states that had had very little bargaining power in matters of economic governance in the EU, precisely due to their position of requiring, rather than providing, solidarity.

Whilst the first summit did not produce direct demands for EMU fiscal instruments, from the 2017 meeting onwards, each communiqué explicitly stated the need for further fiscal integration in the EU: ‘We need… to prepare the discussion on the setting up of a fiscal capacity for the Euro Area’ (Med7, 2017). The bloc’s stance was progressively articulated in a more encompassing project for reform of EU economic governance. As these heads of government stated in Rome, in 2018:

Discussions should be taken forward on the possibility of having a fiscal capacity with an investment and stabilization function within the EMU to foster long term productivity, increase its ability to react to economic shocks and avoid long-term negative effects on our societies. The fiscal framework should provide the right incentives for growth-friendly fiscal policies and continuous reform efforts and achieve the right balance between sustainability and stabilisation. The ultimate objective of an effective EMU should be the progressive convergence of the Member States towards sustainable and socially inclusive growth. (Med7, 2018)

Until the pandemic, however, calls for greater fiscal integration never deviated from the imperatives of the dominant ‘stability culture’, that required any new instrument to incentivise ‘a fiscal policy that enables the right policy mix to ensure sound fiscal consolidation, while supporting investment to strengthen the economic recovery’ (Med7, 2017). This attempt to present a balancing act between common fiscal instruments and a ‘stability culture’ was present already in French President Emmanuel Macron’s famous Sorbonne speech of 2017:

Each one must take their national responsibilities, and that is why in France we enacted unprecedented reforms, which I had announced, and that the government is now implementing. These are reforms of the labour market, of education and training, and of economic financing, which allow for economic growth, creation of employment, and for us to do what we need to do at home. Because we would not be heard if our European ambitions were a mere path towards fixing our domestic problems. That is not our aim, and I will not allow anyone in Europe, given what we are doing in France, to say that we have no legitimacy to make proposals. (Macron, Reference Macron2017)

The realignment of the European South unfolded against the backdrop of substantial reappraisal of the euro crisis and of the virtues of austerity by the European Commission, at least since Jean-Claude Juncker’s presidency (Copeland, Reference Copeland2022; Miró, Reference Miró2021). Already in 2011 and 2012, proposals circulated for the establishment of common fiscal instruments (Van Rompuy et al., Reference Rompuy, Herman, Manuel, Juncker and Draghi2012). A stream of reports articulated the ambition to ‘complete’ the monetary union with some type of fiscal instrument at the central level. The Five Presidents’ Report of 2015 (Juncker et al., Reference Juncker, Tusk, Dijsselbloem and Schulz2015) presented a ‘fiscal stabilisation function’ as a ‘natural development of the euro area in the longer term’. In 2017, Commissioners Dombrovskis and Moscovici (European Commission, 2017b) advanced the need for a European ‘safe asset’, as well as for a ‘dedicated euro area budget’ and a euro area Treasury. The Commission further proposed the establishment of a European Minister of Economy and Finance (European Commission, 2017a). By 2018, in Meseberg, the governments of France and Germany showed shared support for a Eurozone budget, which triggered the formation of the New Hanseatic League (Howarth and Schild, Reference Howarth and Schild2022; Schoeller, Reference Schoeller2021). At the same time, the ECB was itself going through important shifts in policy and discourse (Mugnai, Reference Mugnai2024).

By late 2019, an important reconfiguration in economic ideas and discourses thus seemed to be at work in the EU as a whole. All economic adjustment programmes were over, the southern countries were publicly aligned, and coordinated on the path to economic integration. The EU institutions gave signs of some degree of reappraisal of the causes of the euro crisis and of the consequences of austerity. Moreover, an overall sense that fiscal policy should regain relevance and that a fiscal union was necessary seemed to become increasingly established. It could hardly be argued that there was a consensus over these matters, as important political blocs held on to the ‘stability culture’ that dominated the response to the euro crisis – to the point of very much reducing the scale and significance of any common stability instruments (Schoeller, Reference Schoeller2021). Yet, when the pandemic hit, the political context in the EU seemed to be more conducive for the emergence of a clear ‘solidarity coalition’ focused on fiscal integration, expansion, and on common debt issuance.

The pandemic politics of the southern coalition

When the pandemic of COVID-19 hit Europe, it began its spread from the South. Events in the northern region of Italy, especially in Bergamo, caused shockwaves throughout the EU. Soon, the virus would circulate rapidly in Spain, and images of lockdowns and news of hundreds, when not thousands, of deaths per day would very much dominate the European public sphere. A common thread in the interviews, as seen below, is the sense of urgency and proximity of the human catastrophe that these initial stages generated.

One of the first economic consequences of the early stages of the lockdown was felt in the financial markets, as sovereign spreads began to quickly widen. As an illustration, interest on Greek long-term sovereign bonds was below 1 per cent on the 18th of February, but above 4 per cent on March 18th – a sharp jump in one month. The pandemic was generating a renewed financial panic regarding sovereign debt, which risked unravelling the results of five years of quantitative easing. On March 12th, Lagarde infamously declared that closing down spreads was not the ECB’s task (European Central Bank, 2020b). The backlash, especially from southern governments, was loud and pushed the head of the ECB to backtrack. A week later, the ECB announced its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme: 750 bn euros of new acquisitions of sovereign bonds in the secondary markets were to be expected (European Central Bank, 2020a). This immediately stabilised interest rates.

Yet, stability in the sovereign bond market was seen as insufficient to solve the problem of what appeared to be deeply asymmetrical economic and fiscal consequences of an exogenous, symmetric shock. As put by an interviewee (#2), ‘there was a growing perception that together with the monetary response, we needed a fiscal response’. The dimension and level of coordination of this response was, however, uncertain. The pandemic hit against the backdrop of ongoing debates on the EU budget and in a moment in which ‘so-called frugal member states [had] been driving a very hard bargain and a very hard line’ (Interview #3). Different member states had strikingly different capacities to face a major macroeconomic shock. Moreover, deep uncertainty about the virus and its consequences both for public health and the economy generated strong sovereigntist reflexes which emerged in striking parallel with calls for EU solidarity (de la Porte and Heins, Reference de la Porte and Heins2022; Ekman et al., Reference Ekman, Stahl and Ryner2025).

It was in this context of large uncertainty, combined with the partial rekindling of the cleavages that had structured so much of the debate on EU economic governance debates for a decade, that a group of southern European governments mobilized to influence the economic response to the pandemic. This resulted in a letter to the European Council President on March 25th, 2020.Footnote 2 The following sections discuss the content of the letter, the process that led to its formulation, and its broader significance in debates over economic governance in the EU.

The Letter

It was in this heated context that a group of nine countries sent a public letter to European Council President Charles Michel (Wilmès et al., Reference Wilmès, Macron and Mitsotakis2020). In it, Sophie Wilmès, Emmanuel Macron, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, Leo Varadkar, Giuseppe Conte, Xavier Bettel, António Costa, Janez Jansa and Pedro Sanchez, described the pandemic as an ‘unprecedented shock’ requiring ‘exceptional measures’. The language of ‘emergency politics’ (White, Reference White2019) pervaded the entire text, which was filled with terms such as ‘unprecedented’, ‘unparalleled’, or ‘extraordinary’. Its demands fell into two broad categories. On the one hand, the coordination of national efforts towards curbing the spread of the virus, including the definition of common guidelines and policies, the sharing of information, and the preservation of the common market – as bans on exports of medical equipment had quickly been put in place in some EU countries. On the other hand, the letter directly called for the ‘need to work on a common debt instrument issued by a European institution’. The aim of these funds would be ‘to finance in all Member States the necessary investments in the healthcare system and temporary policies to protect our economies and social model’ (Wilmès et al., Reference Wilmès, Macron and Mitsotakis2020).

As discussed above, calls for common debt were far from new. The EU institutions, especially the Commission, had been pushing for some type of Eurobond for nearly a decade. Each one of these countries had been in favour of a deeper fiscal union and of Eurobonds for several years. The public contributions made by each government for the Five Presidents’ Report of 2015 made this clear, and scholarly research has further shown their stable positions on the matter (Hacker and Koch, Reference Hacker and Koch2017). Contrary to previous proposals, however, this proposal was not presented as a ‘safe asset’ to reinforce the financialisation of the European political economy, or as a basis for an insurance-like stabilization function without permanent redistribution, or a further tool to enforce EU recommendations on national economic policies. The letter proposed shared liabilities at the EU level for fiscal policy goals common to most national economies, namely macroeconomic stabilization and the capitalization of public services under pressure.

Critical to the argumentation was the narration of the crisis as a ‘symmetric external shock, for which no country bears responsibility’ and that ‘we are collectively accountable for an effective and united European response’. There was a total absence of notions such as ‘fiscal consolidation’, ‘structural reforms’, or any discursive elements that could in any way be familiar to the ‘stability culture’ that dominated the previous crisis and that seemed to be a sine qua non condition of each iteration of pre-pandemic proposals for deeper fiscal union.

The debt instrument was presented as a solution for the most difficult challenges of the pandemic in the short-term. Yet, the letter made the case that an agreement on this policy was necessary for long-term prosperity. As such, the horizon of expectation (Koselleck, Reference Koselleck2004) was not merely a short-term fix, but a much more durable solution as ‘buttress[ing] our economies today’ would allow for a ‘rapid recovery tomorrow’. ‘We will also need’, the co-signatories stated, ‘to prepare together “the day after” and reflect on the way we organize our economies across our borders, global value chains, strategic sectors, health systems, European common investments, and projects’. The bond proposed in the letter was part and parcel of an important departure from what had been the dominant discourse of economic governance in the EU, forged at the height of the euro crisis (Moreira Ramalho, Reference Moreira Ramalho2025; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2020a).

The negotiation: moving beyond the ‘Club Med’

The initiative to formulate a letter requesting coordinated action of the EU in the response to the pandemic came in early March 2020, from the Italian government (Interviews #1, #2, #3, and #5). The COVID-19 crisis led Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte to adopt an ostensibly pro-European stance, despite what would be expected given his support from Italian anti-establishment parties (Interview #1). The initial measures proposed by the Commission, namely the suspension of EU fiscal rules and the flexibilisation of state aid, and the monetary intervention coming from the ECB were seen by the Italian government as necessary but insufficient. Yet, the differentiated capacity of member states to use this flexibility was perceived by Italy as well as France as a critical threat to the internal market (Interview #2). In simple terms, Germany was able to materially pursue fiscal stimulus and state aid in a way that had little parallel in the remaining countries. This led the Italian government to bring back the idea of common debt from the ‘drawer’:

This type of discussion on Eurobonds, shared liabilities, etc., is not a new discussion, it is not something that saw the daylight in the context of the pandemic. It was taken back out of a drawer. (Interview #5)

At a first stage, the Italian plan was to publish an op-ed, potentially in the Financial Times (Interview #1), co-signed by different heads of government in favour of a common debt instrument to respond to the pandemic. The creation of the ‘coalition’ or ‘club’ (a term preferred by one of the interviewees) began with the contact of like-minded governments, namely the Spanish and the Portuguese, and France: ‘we never sent it to the full group of 27 [Sherpas]; we targeted, so I made a few phone calls’ (Interview #7). These countries had for years worked on common stances regarding EU economic governance. The importance of French support to the new proposal was perceived as crucial:

As you can imagine we could not even think of a new instrument having France and Germany against it at the same time. But with France on board the idea was perceived as interesting and possible. (Interview #2)

From these early talks, it also became apparent that the proposal could not be a mere reflection of a ‘Club Med’ and that German opposition needed to be diplomatically managed (Interview #2, #7). It was clear that the possibility of success hinged on the capacity of the entrepreneur to garner allies beyond the European South. France was critical not only as a co-signatory but also as a bridge to countries that tend to be ‘on the border’ (Interview #1) between North and South, namely Luxembourg, Belgium, and Ireland. It was ‘key that it was not just Southern countries’ (Interview #1). The initial contacts included ‘all those that could join the effort’ for ‘contacting the others [was] pointless – with them, the game is played at the European Council level’ (Interview #1). The identification of potential allies was based on established networks of political and diplomatic cooperation, which exist across policy sectors in a variety of configurations (Interview #6):

We know each other very well. We do a constant profiling of other member states. We know their basic instincts. We know their presence in previous political coalitions. We have embassies in all these member states that send us reports on how political life works there. So we are basically very well informed. (Interview #5)

The different interviewees indicate a number of contingent factors that allowed for this joint position to be taken in a relatively short period. The dramatic images coming from Lombardy in the Spring of 2020 made it an ‘extremely stressful time’ for decision-makers and made the sense of urgency all the more prominent (Interviews #1, #3). The previous stances taken by Macron regarding deeper fiscal integration, and the political alignment of the governments in Belgium, Ireland, and Luxembourg with the French made the coalition easier to build (Interview #3).

The interviews also reveal how the stringent opposition of the ‘Frugals’ to any solidarity drove a larger wedge with more moderate governments in continental and northern Europe. Historically in favour of deeper integration – and keenly aware of their dependency on the internal market not the least for essential workers during the pandemic – these countries’ governments did not want to be perceived on the side of the ‘hawks’ (Interview #3). Even Ireland, whose stance had in the past been more ambiguous, especially in joining the Hansa coalition, saw the need to be on a pro-EU agenda in the aftermath of Brexit (Interview #3). At the same time, the legacies of the austerity programmes and the Troika (Moreira Ramalho, Reference Moreira Ramalho2020) made the existing instruments of support, namely the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) politically poisonous (Interviews #2 and #3). This was the case even as the ESM created new facilities designed to erode its ‘stigma’, namely connected to the conditionality principles of the previous ESM programmes (Schelkle, Reference Schelkle2021: 47–50). The discussion over the austerity period was central to these negotiations:

I remember that at some point during our conversations the Dutch colleague was present… They know what the financial crisis was, but they do not know what the crisis of 2009, 2010, 2011, and the Troika and all that meant to us. I explained how much we suffered, because people don’t know. Nobody came to see what we endured. (Interview #1)

Moreover, these discussions were unfolding in the immediate aftermath of a European Council meeting on the Multiannual Financial Framework that ‘came to nothing’ (Interview #1). The discussion on the ‘coronabond’ was not ‘held in an isolated manner’ (Interview #5). Finally, there was a sense that the letter to Charles Michel constituted a ‘political message’ or ‘signal’ (Interview #5), but that ‘technicalities’ – and potential reservations of countries such as Belgium and Luxembourg regarding governance – could be ironed out in time (Interviews #3 and #5). Italy and France were thus the two coordinators of the shared effort and formed the bridge between the southern periphery and the remaining member states. This was closely watched by the German government which indicated some exasperation with the scope and pace of the proposal (Interview #3, #7). As an interviewee put it, the German Sherpa was ‘furious’ when he heard about the letter (Interview #7).

An interesting common thread in the accounts provided by the actors involved is the relevance of the personal relationships that were established at the time. The frequency of exchanges and the informality brought about by the communication via Internet channels (e.g., WhatsApp groups) created a form of ‘SMS diplomacy’ (Interview #1) from which ‘very lasting relationships were established’ (Interview #3, #7). As an interviewee put it, ‘We became friends during this negotiation’ (Interview #2). It was ‘the good Europe’, another said (Interview #7). This was observed amongst EU leaders, but also amongst the small group of actors in charge of drafting the letter – mostly composed by each government’s EU Sherpa, many of whom have since been placed in high profile positions in domestic governments or international diplomacy.

The experience of the different interviewees in the negotiation process varied to some extent: the ‘penholder’ made the contacts and negotiations their priority in those weeks, but the different co-signatories did not indicate major cleavages or points of tension in the formulation of the document. Not the least because, as cited above, this was seen as a ‘signal’ whose technical intricacies would be resolved later. Yet, there was keen awareness of the sensitive content of the proposal. For instance, the term ‘Eurobond’ was explicitly removed and replaced by a more nuanced ‘common debt instrument’ (Interview #2, #7) in order to tame conflict in negotiations at the European Council, especially with Germany. Indeed, whereas the initiative for the early proposal was ‘Italo-French’, as the two ‘large’ countries of the South managed to gather support, it soon became ‘Franco-German’ in the negotiation of the deal made public on May 18th. As an interviewee put it, ‘three weeks of intensive negotiations with the Germans… [implied] three years of work beforehand’ (Interview #7). In this regard, the channel of influence of the ‘solidarity coalition’ appears similar to the one identified by previous contributions regarding the ‘Frugals’ or the ‘Hansa’, as its success hinges on its capacity to influence Franco-German compromises (Howarth and Schild, Reference Howarth and Schild2022; Schoeller, Reference Schoeller2018).

A new morality tale

The proposal for a ‘coronabond’ motivated by the letter was kept on the agenda of the European Council’s video summit of March 26th, but ‘the initial reaction was not positive’ (Interview #5). Northern governments were strongly opposed to new instruments (de la Porte and Heins, Reference de la Porte and Heins2022; Ekman et al., Reference Ekman, Stahl and Ryner2025). The rapidly unfolding crisis in southern Europe was in part framed as a problem of unhealthy public finances. Dutch Finance Minister Wopke Hoekstra called for an ‘investigation’ of the fiscal and economic situation of Spain, which resonated with the experience of economic adjustment programmes and permanent surveillance instruments deployed in the 2010s. This time, however, the political reaction of southern Europe was cohesive in comparison to the past. In a rare public clash, Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio Costa decried Hoekstra’s comments as ‘repugnant’ (von der Burchard et al., Reference von der Burchard, Oliveira and Schaart2020).

In the weeks that followed the late March summit, a new morality tale seemed to gain shape in the public debate around governing the pandemic. According to the interviews, it took a short time for the idea of a coordinated response to emerge as consensual and for divisions to emerge on the relative weight of grants and loans: ‘By May everyone agreed that we had to throw money at this’ (Interview #3). Pushed by southern countries, but also by the heads of EU institutions, the crisis was framed not as a result of faulty domestic politics, but as an exogenous, symmetric (if delayed) shock for which, as the letter affirmed, no country could be held responsible. As an interviewee put it:

To phrase it in a very blunt way, as if I was Dutch, it was not their fault. It was not the question of spending on booze and women as Dijsselbloem said back in 2009 or 2010… (Interview #3)

During the pandemic, a consensus emerged that failure of EU coordinated action – and solidarity – would pose an existential threat to the bloc (Ferrera et al., Reference Ferrera, Miró and Ronchi2021), already affected by the long and difficult process of partial disintegration posed by Brexit. As Conte said to the German media in April 2020, ‘we are writing history, not an economics textbook’ (Fortuna, Reference Fortuna2020). Or, as Macron would state to the Financial Times in April 2020:

We are at a moment of truth, which is to decide whether the European Union is a political project or just a market project. I think it’s a political project… We need financial transfers and solidarity, if only so that Europe holds on.

Governments pushing for shared liabilities and solidarity presented themselves as the ‘responsible’ actors, keen on a political strategy that could adequately respond to the short-term drama of healthcare systems pressured beyond capacity, economic stagnation from lockdowns, and of the overwhelming human toll of an uncertain disease. As the communiqué of the Med7 summit that followed the adoption of the recovery programme indicated, the ‘agreement, unimaginable just a few months ago, is an unprecedented and innovative development… It is a strong signal, that of a Europe of solidarity and future-oriented’ (Med7, 2020). In a striking ideational switch, the moral dichotomies that lingered from the euro crisis rapidly eroded, to the point that the new facility was steered towards mitigating some of the harsher legacies of the previous decade of austerity (Armingeon et al., Reference Armingeon, de la Porte, Heins and Sacchi2022).

Conclusion

The letter co-signed by nine countries, in March 2020, symbolically marked an important transformation in EU negotiations over economic governance reforms. Debtor countries, which had in the previous crisis attempted to gain ‘confidence’ through differentiation, found their way into a rapid convergence of positions regarding the appropriate way to respond to the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. In two months, there was an agreement for a recovery programme branded ‘Next Generation EU’, that mobilised 750 bn euros, of which a large share was made up of grants, to be distributed over several years throughout the EU.

The EU recovery programme was financed through a shared coronabond, in line with the demands of the solidarity coalition. However, the new instrument was not used for short-term fiscal stimulus to counteract the pandemic. Most spending aimed at sustaining short-term economic activity and at keeping the healthcare system working remained at the national level, with the support of accommodative monetary policies and a relaxed set of budgetary rules in the EU. The coronabond, ultimately small in comparison to collective spending, was mobilized for ‘reconstruction’, long-term investments, and policy priorities, such as the green transition or digitalization, that remained far from the initial proposal (Crespy, Massart and Moreira Ramalho, Reference Crespy, Massart and Moreira Ramalho2024).

Hence the direct link between the letter and the bond – and what was made of it – is nuanced. The aim of this paper is less to identify the causal mechanisms between the coalition and the outcome, than it is to understand the constitution of such a coalition in the first place. The case of the ‘solidarity coalition’ is especially interesting given the evolving strategies of its members from the euro to the pandemic crises, which cannot be fully explained by their structural or material circumstances (even though these certainly influenced their positions). Moreover, whereas other coalitions of member states in the EU have received considerable and consistent scholarly attention, the southern European grouping remains poorly studied and understood.

The paper shows that the coalition emerged from the entrepreneurship of the Italian government and of the concerted diplomatic efforts of Italy and France, that mobilized EU Sherpas with the intent of shaping the early response to the crisis at the level of the European Council. These diplomatic efforts built on existing and longstanding positions of different countries. The core of the coalition was in southern Europe, but these actors understood that two key conditions for success were (1) the support of ‘larger’ member states, namely France, and (2) the involvement of governments beyond the ‘club Med’, namely in continental and northern Europe. These actors pushed for a discourse on economic governance in the EU that diametrically contrasted with the dominant notions of ‘responsible’ crisis management during the euro crisis (Crespy, Moreira Ramalho and Schmidt, Reference Crespy, Moreira Ramalho and Schmidt2024; Mair, Reference Mair, Schäfer and Streeck2013).

The analysis developed in this paper contributes to our understanding of EU economic governance in critical ways. First, it argues that interstate coalitions, though still underexplored, invite us to revisit traditional integration theory and, relatedly, illuminate remaining blind spots in the process of reform. Secondly, it shows that country preferences (even when stable from crisis to crisis) are insufficient to explain their coordination, which appears contingent on ideational developments as well as on the agency of government actors (including diplomatic relations). Whereas the dominant narratives around the euro crisis led to a centrifugal process of anti-coalition, the response to the pandemic led to a centripetal process of coalition. The paper ultimately shows how the governments of the European South found their way into the formation of a stable negotiating bloc capable of successfully presenting common positions on the most critical aspects of EU economic governance. As put by one of the interviewees (#5), ‘sometimes politicians and human beings in general learn from mistakes of the past’.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773925100295.

Data availability statement

The qualitative interview data generated for this study consist of anonymised elite interviews. Due to the risk of deductive disclosure and the confidentiality agreements with participants, the interview transcripts cannot be made publicly available. An anonymised interview guide and a table documenting the interviews cited in the article are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

The public-access data used in the analysis – including media articles and official government declarations – are available from publicly accessible sources cited in the article. A compiled list of sources used for the analysis is provided in the supplementary materials.

Acknowledgements

I am thankful to the colleagues that read and discussed previous versions of this paper at workshops on EU economic governance reform both at Université libre de Bruxelles and at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies. I am particularly thankful to Amandine Crespy, Vivien Schmidt, Camilla Locatelli, and Vanessa Endrejat. I am also thankful to the interviewees that kindly accepted to discuss their work and contribute to our understanding of interstate coordination in the EU. Final thanks to the reviewers, editors, and staff at EPSR. The usual disclaimers apply.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique under Incentive Grant for Scientific Research [F.4508.20].

Competing interests

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).