Introduction

The municipal elections measured political parties’ popularity at midterm, preceding the first regional elections, to be held in January 2022 as the culmination of the long-term plan of Finnish governments: the regional and social and health reforms (Palonen Reference Palonen2020). Key politicians were competing for positions, including the mayor. The continuation of the Covid-19 pandemic highlighted disagreement between the health authorities and the ministry responsible for health and other ministers on the matter of restrictions. Most Finns were double vaccinated by the end of 2021, and restrictions lifted in October, only to be put back in place in December with the Omicron wave. Passing the EU Next Generation package was supported by the government parties and most of the National Coalition Party/Kokoomus (KOK) MPs in the opposition.

Among the parties, the transfer of power from Jussi Halla-aho in the Finns Party/Perussuomalaiset (PS) to Riikka Purra sedimented the party line and sought to offer an easier coalition partner in preparation for the general elections in 2024. The local elections were an interparty contestation, where the opposition thrived but did not experience a landslide.

The main divisive issue was measures to tackle the Covid-19 pandemic, where the minister responsible Krista Kiuru from the Social Democratic Party/Sosialidemokraatit (SDP) was for tight reins but the millennial Prime Minister Sanna Marin was demonstrating the need for relaxing the measures. Pandemic scepticism gained political ground. The new party Power Belongs to the People/Valta Kuuluu Kansalle (VKK) reached the necessary support for registration in record time. The decision to purchase US Lockheed Martin fighter jets for the Finnish Army in the autumn made palpable the collaborative relationship with NATO.

Election report

Governing in the pandemic was also visible in the municipal elections postponed from April to June, as the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare believed that many from at-risk groups would be vaccinated by then, and so elections would be safer (Ministry of Justice 2021). The advance voting lasted extraordinarily for two weeks because of the pandemic, from 26 May to 8 June (abroad 2–5 June) (Ministry of Justice 2021). The term in office, starting on 1 August, will be two months short of four years, as the next municipal elections will be organised together with the regional elections in June 2025. The first regional elections in Finland will be held in January 2022. The open-list character of Finnish elections makes them significant for intraparty contest (von Schoultz & Papagergiou 2021). The localness, electoral strategies and dual mandates of the 2021 elections were discussed publicly in Finland, and have also been subject to scholarly analysis (Arter & Söderlund Reference Arter and Söderlund2022). In the interparty contest, they contested popularity of KOK and SDP in the cities, and the viability of the Centre Party/Suomen Keskusta (KESK) in their more rural support areas. They also tested PS, the Green League/Vihreä Liitto (VIHR) and new parties support nationwide.

The municipal elections were won by KOK with 21.4 per cent of the vote at the national level, 1552 seats (+62) and notably the municipal the mayors’ posts in Helsinki, Turku and Tampere. The second most voted party was the SDP, with 17.7 per cent of the vote and 1451 seats, with some urban losses (–246). The contest was a crucial one for KESK, which received 14.9 per cent of the vote and retained its victory over seats, receiving 2445, but also losing more than others (–379). The FP was in its footsteps with 14.5 per cent of the vote and gaining a record number of seats (1351, +581). The VIHR and the Left Alliance/Vasemmistoliitto (VAS) lost seats, but almost reached previous support percentages.

The PS leader, Jussi Halla-aho, was the most popular candidate with 18,843 personal votes, but his party was only the fifth largest nationwide and in Helsinki, where criticism of the city's urban development was partly channelled from VIHR to VAS. In Helsinki, KOK retained its mayoral position, with the nationwide second and third most popular politicians Elina Valtonen (KOK), new to Helsinki, and Juhana Vartiainen (KOK), the successful mayoral candidate. Deputy mayors came from the next successful parties, VIHR, SDP and VAS. In Tampere, Prime Minister Sanna Marin (SDP) received the fourth largest number of votes nationwide (Näveri Reference Näveri2021), but Anna-Kaisa Ikonen (KOK) was elected mayor, as KOK became the largest party by 15 votes. The success of 49 elected councillors nationwide was a surprise for Movement Now/Liike Nyt (LIIK), personified in the Helsinki-based critical politician Harry (Hjallis) Harkimo, formerly of KOK, as it became a vehicle for voicing local concerns beyond dominant parties in many municipalities (Salminen Reference Salminen2021; Valtanen & Kuukkanen Reference Valtanen and Kuukkanen2021).

Cabinet report

In early 2021, the Covid-19 pandemic affected Marin's government's action on a daily level. Even if local actors had already loosened their restrictions, the government maintained their tight policy regarding control of public meetings and national borders. It issued a State of Exception on 1 March as a reaction to the intensive surge of infection rates in February, and on 27 April these were lifted. At the end of March, the government also issued a law amendment to restrict freedom of movement under pandemic conditions, but this was not processed. Covid-19 restrictions aroused disagreements between government partiers and ministers (Luukka Reference Luukka2021). Vaccinations started slower than planned, but in December 2021 more than 82% of those over 12 years old had got their second shot of the Covid-19 vaccine and the third round had already begun (Hallikainen Reference Hallikainen2021). The use of masks was debated, and medical studies based on a Finnish case recommended wearing FFP2 masks (Hetemäki et al. Reference Hetemäki2021). In October, the pandemic restrictions were lifted and a Covid-19 vaccination pass was adopted, but at the end of November restrictions were put in place again due to the Omicron variant wave (Finnish Government 2021a). By autumn there was a clear tug of war between the hard line of Krista Kiuru (SDP), the Ministry of Family Affairs and Social Services from the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, and some of the more pro-relaxing government and the expert organization Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL).

In government, cooperation parties had a hard time while they made decisions on taxation of transport fuels, peat, private land redemption, climate and economic policy. Especially VIHR and KESK locked horns during the eight-day budget negotiations in April and September. Climate issues were raised on the agenda, but concrete decisions were argued to have been meagre (Mansikkamäki Reference Mansikkamäki2021). The government issued reports on human rights, development, defence, surveillance and housing, and the language report due every parliamentary term; these were also documented in the annual report (Finnish Government 2022b).

The purchasing of Lockheed Martin F-35A Lightning II multipurpose fighter systems from the United States was confirmed on 10 December 2021 after a long process of comparing different options. Altogether, the acquisition costs were approximately €8.4 billion. Together with the modernisation of the defence equipment, there were also renewals in intelligence of Finnish defence, control of Finnish territory and the management of defence (Hakahuhta et al. Reference Hakahuhta2021). Multiparty consensus was strong, and Finnish membership of NATO was discussed.

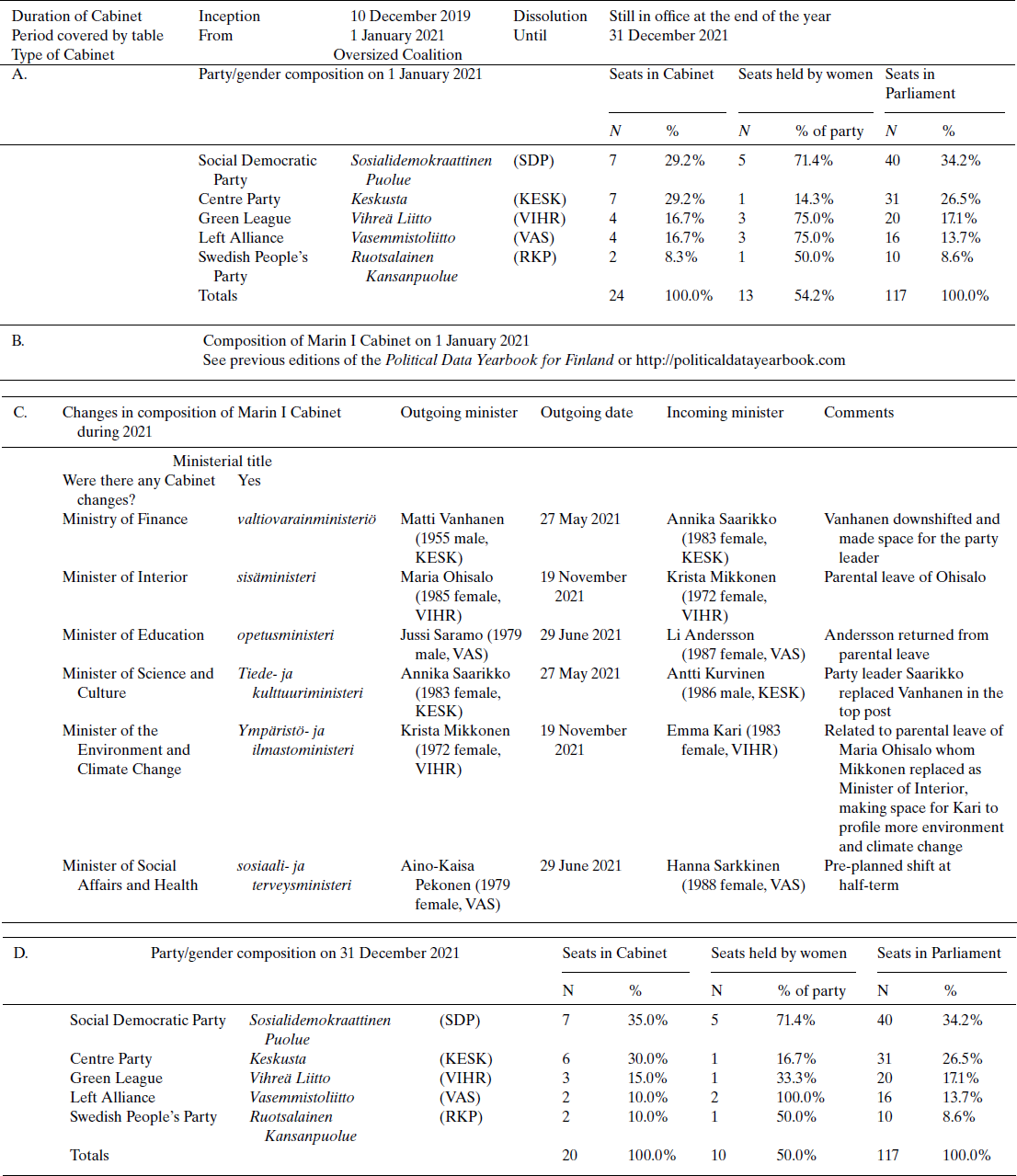

As Table 1 shows, many ministerial shuffles were related to strings of parental leave substitutions that included profiling of the parties’ policies, such as the more visible Green activist Emma Kari (VIHR) as Minister of the Environment and Climate Change, and making space for Krista Mikkonen, with more experience in the Marin I government, as Minister of Interior. Li Andersson (VAS) returned to her post as Minister of Education and Hanna Sarkkinen became the minister of Social Affairs and Health. KESK leader Annika Saarikko (KESK) substituted Matti Vanhanen in a more prominent role of Minister of Finance, making space for a newcomer to ministerial posts. Antti Kurvinen was chosen as Minister of Culture and Science.

Table 1. Cabinet composition of Marin I in Finland in 2021

Sources: Finnish Government (2021b); Forsberg (Reference Forsberg2021); Ovaskainen (Reference Ovaskainen2021).

Parliament report

Eduskunta (Parliament) debated five confidence votes tabled by the main opposition parties KOK and PS (Eduskunta 2021a). In February, Jussi Halla-aho, the chairperson of PS at the time, issued a question on Finland's participation in the European Union (EU) recovery package, also known as Next Generation EU. KOK party leader Petteri Orpo raised issues on public economy and national debt after a government's budget session, and Anna-Kaisa Ikonen (KOK) questioned the confidence of the government when it decided to carry out a reform of the social and health service structure of Finland after almost two decades of preparation process. Riikka Purra, the newly chosen chairperson of PS, raised two questions on immigration policy against the confidence of the government: on the economic costs of humanitarian immigration and family reunification policies, and on hybrid attacks and border transparency after Belarus's actions towards Poland and Lithuania (Eduskunta 2021a).

The Next Generation EU package was approved with 134 votes to 57, but notably 10 MPs from the National Coalition, in opposition, and two from KESK, in government, voted against (Pilke et al. Reference Pilke, Steenroos and Hakahuhta2021). Parliament approved the social and health services reform with 105–77 votes (Eduskunta 2021b), paving way to the long-awaited regional reform. Parliament approved the digital Covid-19 pass in October with 105–33 votes (Eduskunta 2021c), and the F-35 multipurpose fighter system in December.

Parliament also passed new legislation on money collection, completed its National Risk Assessment of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in March 2021, and created an Action Plan for National Risk Assessment of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing 2021–2023 (FATF 2021).

In a case of gross misuse of official position, Parliament fired Tytti Yli-Viikari, Director General of the National Audit Office, accounting for her personal use of Finnair frequent-flyer points accrued in work-related flights, fraud in payment instruments and breach of official duty (Simola Reference Simola2021). In relation to its internal code of conduct, Parliament discussed the case of a threatening tweet by Ano Turtiainen (VKK) to fellow parliamentarians who were for face masks, considered it as a freedom of speech and resolved not to take action against the parliamentarian of the Finns party splinter (De Fresnes Reference Duxbury2021).

There were minor changes in Parliament's composition. The mayors of Helsinki, Juhana Vartiainen (KOK) and Anna-Kaisa Ikonen (KOK), and Deputy Mayor of Helsinki, Paavo Arhinmäki (VAS), left Eduskunta. This paved the way for three new parliamentarians: Jari Kinnunen (KOK), a crisis control expert at the European Expert Action Service on the West Bank and Gaza; Atte Kaleva (KOK), social-media age politician, famous for having been kidnapped in Yemen; and Sultaan Said Ahmed (VAS), a Somali Finn working with human rights and the sans papiers at the Deakoness Foundation (Lehto Reference Lehto2021). Jussi Saramo (VAS), who had substituted Li Andersson as minister, was chosen as the parliamentary group leader to replace Arhinmäki.

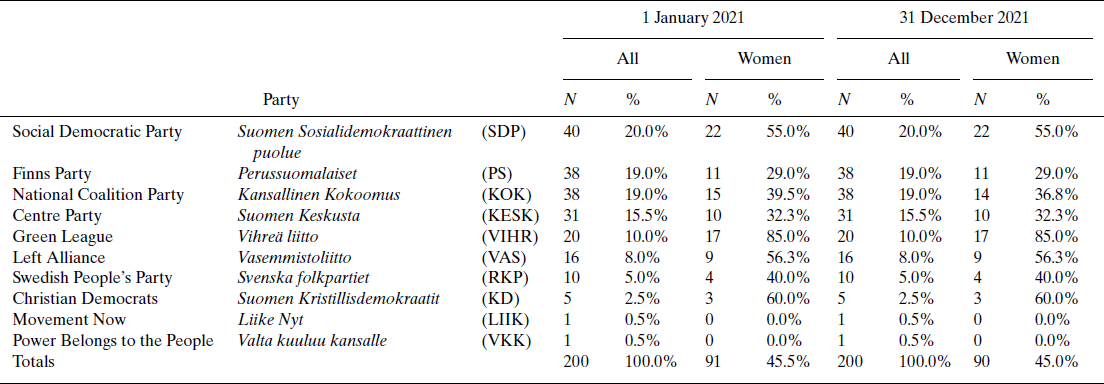

For data on the composition of Parliament, see Table 2.

Table 2. Party and gender composition of the Parliament (Eduskunta) in Finland in 2021

Note: MPs elected to mayors in the local elections in June gave up their parliamentary seats to the next candidate on the party list.

Source: Lehto (Reference Lehto2021).

Political party report

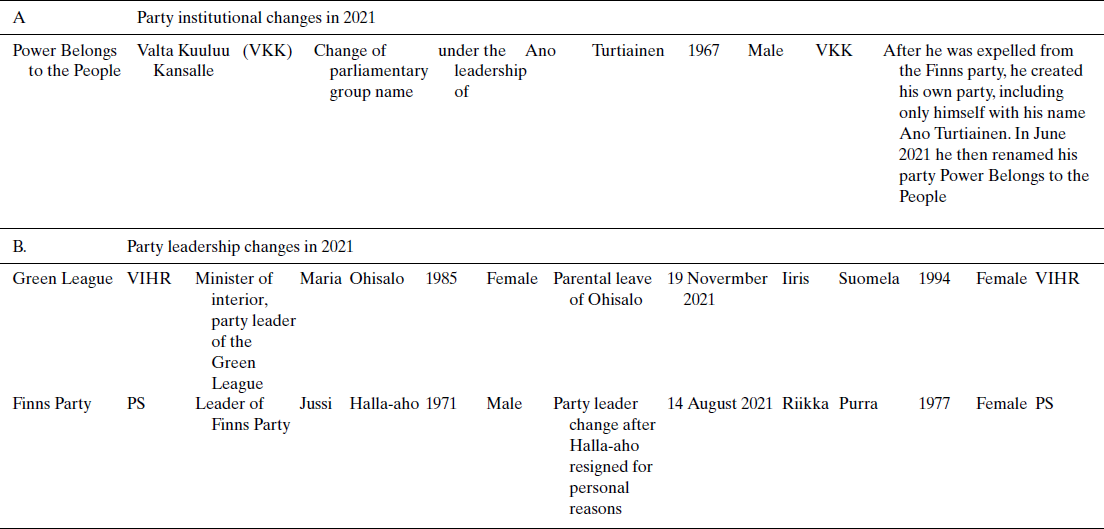

PS party leader, Jussi Halla-aho, who was topping ratings of successful political leaders and had just been most popular in personal votes in the local elections, increasing his party's seats nationwide by 50 per cent, resigned shortly after the local elections. A follower of the Halla-aho's ‘patriotic’ party line, the vice-chair of the party, Riikka Purra, was voted in as the party's chairperson on the 14 August. Halla-aho did not reveal any reasons behind his resignation, but he alluded to a stored secret letter where these were to be kept from the public. Halla-aho's decision was surprising for PS. The party had recovered its popularity, yet the municipal elections were not the landslide they needed to set aside KESK, despite the leadership's effort of canvassing among local groups around the country (Palonen Reference Palonen2021b). The new party leader would have two years to find further strength for the elections. Support rates for Purra's PS at the end of 2021 were the same as before the leadership change.

VKK was registered as a new party in September 2021. The party started as a one-MP parliamentary group in the first week of June 2020, when Ano Turtiainen was expelled from PS due to his racist tweets mocking the murder of George Floyd (Palonen Reference Palonen2021a). On 17 June 2021, Turtiainen renamed his parliamentary group to Power Belongs to the People, to match the newly created association. VKK managed to collect the required 5000 supporter signatures, or ‘cards’, by August 2021 to transform his group into a party, with a speed that even surprised the party leader himself (Liukkonen & Krogerus Reference Liukkonen and Krogerus2021).

The Minister of Interior and VIHR party leader Maria Ohisalo started parental leave on 19 November 2021, and was substituted by Iiris Suomela as party leader. The aim was to direct more attention to the climate, as Ohisalo would return to the post of the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change after her leave (Bjurström & Tikkala Reference Bjurström and Tikkala2021).

For data on party institutional and leadership changes, see Table 3.

Table 3. Changes in political parties in Finland in 2021

Sources: Bjurström and Tikkala (Reference Bjurström and Tikkala2021); Palonen (Reference Palonen2021b).

Institutional change report

The most significant legislative change in 2021 was Parliament's adaptation of the legislation on establishing well-being services counties and reforming the organization of healthcare, social welfare and rescue services in June (Finnish Government 2022a).

The new healthcare and social services model will divide the country into 21 well-being services counties. The social welfare, healthcare and rescue services that municipalities are currently in charge of will be transferred over to these well-being services counties. In contrast with other municipalities, Helsinki will continue to be responsible for organizing its area's healthcare, social welfare and rescue services. In addition, the new Social Services, Health Care and Rescue Services Division will be set up in Helsinki on 1 January 2023. Moreover, the rescue services will be moved from the Urban Environment Division to the new division, where they will form their service entity (City of Helsinki 2022).

Issues in national politics

A major issue to discuss was the Covid-19 pandemic and its handling, where the cultural and event sectors prominently raised their voice. The Covid-19 vaccines became available to everyone, but not all, including health sector personnel, were vaccinated. Political competition took place at the local level around health services and the regional reform as the municipal elections were held in summer 2021. The same discussion continued in the run up to the regional elections in January 2022.

Other discussions revolved around the increasing debt and the EU's recovery package, climate change, police funding and the funding of the judiciary. A major reform, which remained unresolved, addressed the voluntary sector, arts and science was a reform of the funding for the current beneficiaries of the publicly owned gaming and lottery company Veikkaus.

Since the presidential elections were looming at the middle of the second and final term of President Sauli Niinistö (KOK), three names of popular candidates emerged beyond others in the polls: in December, the Governor of the Bank of Finland, Olli Rehn (KESK) and the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Pekka Haavisto (VIHR) held the top post with 19.9 per cent and 14.3 per cent support; and the Prime Minister Sanna Marin (SDP) with 8.7 per cent. At the time of December polling Marin had been subjected to controversy for only having had the parliamentary work phone with her at an evening out in a night club while unknowingly exposed to Covid-19 (Vainio Reference Vainio2021).

Marin had been subjected to controversies already in June under the breakfast gate (aamiaiskohu) for using, monthly, €850 of taxpayers’ money for food bought during the pandemic in the official Prime Minister's residence – a misuse which she was not aware of and was willing to pay retroactively (Strömberg & Piirainen Reference Strömberg and Piirainen2021), the Finnish Prime Ministers not having a full-day catering allowance. In the Prime Minister's summer residence she had also organised a party for the cultural sector a day before funding cuts in October (the cuts were cancelled days later) and a gig after-party for two dozen of her friends in September. Some of this received international attention in the social media and the press (Duxbury Reference Duxbury2021). The pandemic toll on the Prime Minister's personal life has been discussed in the media and among the party elite, where not everyone shares the millennial coping mechanisms and the move from tight-reined leader of restrictions to relaxed openness (Pilke et al. Reference Pilke, Steenroos and Hakahuhta2021). Possibly, the controversies were a way of discussing pandemic conditions and negotiating within the SDP and the wider society whether or not to relax restrictions.