In 1901, German education reform association Verein Frauenbildung-Frauenstudium ran a contest to produce a feminist ‘catechism’ which would capture the women’s movement’s doctrinal and historical tenets. The winning entry devoted several questions to the movement in America, and included this call and response:

In what way did the emancipation of negro slaves contribute to the progress of the women’s movement?

The women did not want their rights to stay behind those of a humble race, for whose liberation they had fought themselves. (Wollf Reference Wollf1905, 12)Footnote 1

Compressed to the point of warping, this catechism expressed a genealogical understanding of the relationship between women’s rights and abolition that was widely shared and often restated. This chapter traces how, in the expanding range of histories, instructional texts, articles, and other knowledge production by feminist internationalists, this specifically American story became a foundational myth of the international women’s movement. The consolidation of the ‘antislavery origin myth’, a specially crafted story grounded in indignation and racial animus, as an authoritative, strategic, and emotive origin story was fuelled both by well-documented memory politics among American movement leaders and by a demand for a suitably unifying narrative for the growing phalanx of upper middle-class European campaigners who hoped to convince the public that women’s emancipation was a natural next step in the progress of the age.

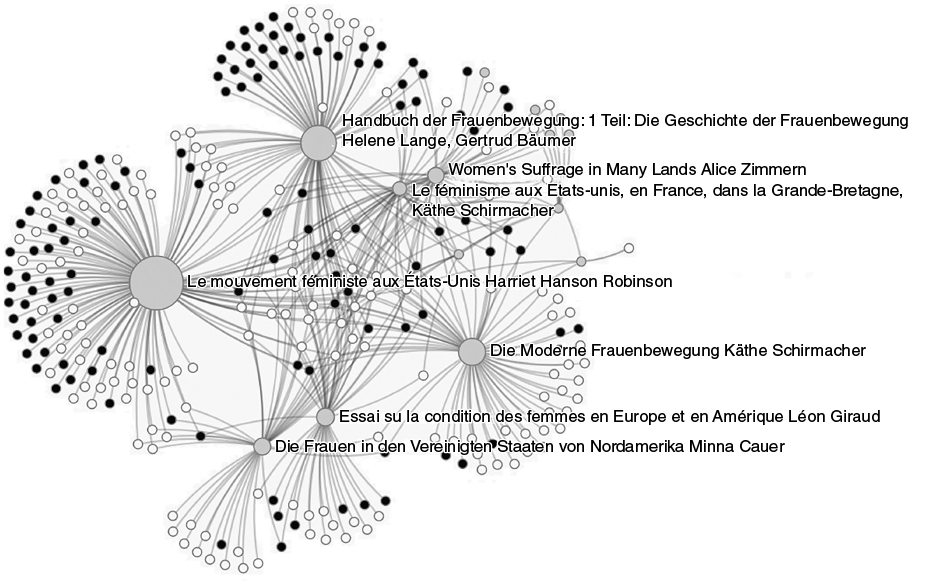

Central to this chapter’s thesis is the genre of the comparative historical survey, of which women’s rights advocates published a number between 1881 and 1914.Footnote 2 Increasingly structured international contact and collaboration, chiefly supported through congresses and associations, paved the way for these collaborative efforts. Instead of reflecting the movement’s diversity, the works became a vehicle for proving that the movement for women’s rights was a uniform world-historical event. Though there was much variety in how ‘feminist internationalists’ (Rupp Reference Rupp1997, 11) made this case, they had in common their emphasis on the importance of the American example and particularly on the centrality of the antislavery origin myth in this history. Figure 5.1, a networked representation of the people and events referenced in these histories, showcases this. Though other overlaps between the histories existed, the only two events referenced across all volumes were: the story of the meeting between Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott at the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840 and Seneca Falls Convention they came to host in 1848.Footnote 3

The story of the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention, first told by Elizabeth Cady Stanton herself, held a powerful imaginative potential both in the US and in Europe. It was formalised in the first volume of the History of Woman Suffrage (1881), a monumental project directed by Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and proliferated into wider circles at home and abroad, percolating up into scientific discourse and trickling down into suffrage pamphlets. This chapter follows the makings of this tale and its later adaptations. Paying close attention to the rhetorical uses the story was put to by different feminist internationalists casts light not just on how the women’s rights campaign oriented itself towards what, at the turn of the century, supporters painted as the rapidly receding prehistory of their own struggle, but also on the different ways in which they used the production of authoritative knowledge to create a highly exclusionary semblance of unity out of increasingly complex international collaborations. Rather than post hoc fact-finding, the evolving discipline of history writing was a powerful medium to do just this, with its claims to having the final word, its intimate alliance with liberal common-sense attitudes regarding historical progress, and the narrative opportunities it afforded to rouse emotion and promote implicit logics, such as the equation of emancipation with the achievement of suffrage. This chapter will turn to the History of Woman Suffrage first, before examining the game of telephone taking place in knowledge production on the other side of the Atlantic, where this book served as a key source. In this way, this chapter will unpick the role of history writing and memory actors such as Stanton in the development of the feminist internationalist aspirations of the era.

The history of woman suffrage

Though different accounts of feminism’s relationship to antislavery existed side by side, the urtext of the antislavery origin myth was the History of Woman Suffrage (HWS). This project, started by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda J. Gage in 1876, would ultimately result in a monumental, three-volume account which, alongside its narrative interpretation, reproduced much of its documentary evidence (1881–1886).Footnote 4 As the preface explained, the editors’ ambition was to create an ‘arsenal of facts’ for future historians out of the individual experiences of movement actors (Stanton et al. Reference Stanton1887, vol. 1, 7). Though the women billed themselves as editors, they composed much of the book themselves, with Stanton and Anthony particularly pruning texts to the needs of their project (Tetrault Reference Tetrault2014, 125–127). They likened collecting first-hand accounts and materials to building a ‘magnificent structure’ out of individual bricks (Stanton et al. Reference Stanton1887, 8) and, with their suggestion that an actor-produced history gets ‘nearer the soul of the subject’ (8), explained the particular merit of their text to future scholarship. With this explanation, in one fell swoop the editors gave two compelling arguments for their account’s lasting authority – apart from the sheer, unparalleled girth their writing would assume. The project was itself part of the arc of the historic progress of women, with its contributors central among those whose untiring labour had fuelled it. The editors also promised to let the actors speak for themselves, without inflecting their words with their own well-known controversies. This was a well-designed, if ultimately untenable, claim of objectivity, sidestepping questions about the team’s credentials as representatives, chroniclers, or, indeed, historians.

Throughout, the editors emphasised that the roots of women’s rights claims lay in their experiences in organised abolitionism, though, as will become clear, they told that story differently to many of their colleagues (Tetrault Reference Tetrault2014, 122). Chapter 3 of the first volume, which begins the historical narrative, described the 1840 World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London. On the first day of this event, Stanton recounted, delegates voted against allowing women attendees to participate in the debates but instead had them follow the proceedings from the spectator galleries. It was on this occasion that young Elizabeth Cady Stanton met veteran advocate Lucretia Mott and, as the story went, commiserating over their outrage at their exclusion, they conceived the idea of organising a women’s rights conference.

As Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton wended their way arm in arm down Great Queen Street that night, reviewing the exciting scenes of the day, they agreed to hold a woman’s rights convention on their return to America, as the men to whom they had just listened had manifested their great need of some education on that question. Thus a missionary work for the emancipation of woman in ‘the land of the free and the home of the brave’ was then and there inaugurated.

This idea became reality in 1848 with the Seneca Falls Convention, which Stanton and Anthony claimed as the birthplace of the women’s rights movement. The events of 1840 were a pivotal point in the history of women’s rights, the editors explained, as ‘[T]he debates in the Convention had the effect of rousing English minds to thought on the tyranny of sex, and American minds to the importance of some definite action toward woman’s emancipation.’ The chapter finally concluded that ‘The movement for woman’s suffrage, both in England and America, may be dated from this World’s Anti-Slavery Convention’ (Stanton et al. Reference Stanton1887, vol. 1, 62).

As later historians have pointed out, the HWS provided a ‘very full account of only half the story’ (Cullen DuPont Reference Cullen DuPont2000, 115; see also Dubois Reference DuBois1998). The project bore the marks of a bitter dispute within the ranks of American feminism. The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, had established birthright citizenship and equal protections of the laws for all ‘persons’, which included African Americans, but it had also introduced the qualification ‘male’ into the Constitution in the section on determining apportionment and the right to vote in states – though it did not specifically enfranchise males, African Americans, or anyone exclusively. This turn of events led to controversy within the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), founded in 1866 to ‘secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color or sex’ (Stanton et al., Reference Stanton1887, vol. 1, 173). Leaders like Lucy Stone and Frederick Douglass considered the compromise necessary to ensure the protection of newly freedmen and women. The faction led by Stanton and Anthony, on the other hand, considered the Fourteenth Amendment a significant setback for the cause of women’s equal rights, which they now prioritised outright. They also denounced their former colleagues’ support for this compromise, which they came to frame as a stab in the back. At the contentious AERA Convention of 1869, disagreements over whether to support the proposed Fifteenth Amendment to extend the suffrage to black men turned increasingly hostile and, soon after, the AERA split into two rival women’s rights organisations: the National Woman Suffrage Alliance (NAWSA), led by Stanton and Anthony, and the American Woman Suffrage Alliance, under the helm of Lucy Stone (Davis Reference Davis2011 [1981], ch. 4; Dudden Reference Dudden2011; Tetrault Reference Tetrault2014, 31ff.). In the decades that followed, each side would point to the other as the renegade. This dissolution, in Angela Davis’ influential estimation, ‘brought to an end the tenuous, though potentially powerful, alliance between Black Liberation and Women’s Liberation’ (Davis Reference Davis2011 [1981], 84).

The HWS justified NAWSA’s side of the story. In addition to whatever tactical concerns Stanton and Anthony brought to the project, this sidedness was exacerbated by the reluctance of former collaborators like Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell to contribute to the project. In her detailed analysis of suffragist memory work and the composition of the HWS, Lisa Tetrault estimates that this was a crucial missed opportunity (2014, 119, 138). The HWS, a sweeping story and unprecedented archival effort all in one, became Stanton and Anthony’s ‘most robust intervention in post-Civil War memory politics’ (Tetrault Reference Tetrault2014, 15). In the story of the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, the HWS launched the American suffrage movement’s ‘first and most enduring master narrative’ (120). The books are still the major gateway for research into this period in the American women’s movement – though they might not have been had Anthony not burned the immense archive of sources the team had amassed over years of labour on the book as she neared the end of her life (Tetrault Reference Tetrault2014, 181).

The HWS used compositional, narrative, and stylistic strategies which marshalled the history of antislavery in ways that supported Stanton and Anthony’s point of view and which had considerable transnational effects as they made their way into later European accounts. In weaving acerbic observations into their factual accounts, the editors of the HWS stylistically signalled that they took up the mantle of the abolitionist hard-liners. The content note at the start of chapter 3, for instance, announced discussions of ‘Bigoted Abolitionists’ and of how ‘James G. Birney likes freedom on a Southern plantation, but not at his own fireside’ (Stanton et al., Reference Stanton1887, vol. 1, 50). The description of Mott and Stanton’s resolution as ‘a missionary work for the emancipation of woman in “the land of the free and the home of the brave”’ was recognisable to English and American readers not just as a play on imperialist discourse, but more specifically as an echo belonging to a well-established tradition of abolitionist rhetoric, which frequently drew on ironic reversals of who and what counted as ‘civilised’ and ‘savage’ persons and countries (see Chapter 2; Bormann Reference Bormann1971, 20ff.; Walters Reference Walters1973; Carey Reference Carey2005, 135ff.; Plasa Reference Plasa2007). In echoing Garrisonian rhetoric, the authors cast their own actions as the spirit of ‘true’ abolitionism. They coupled this with a narrative arc that returned often to the ‘betrayal’ by abolitionists of both women and principle and with their foregrounding of indignation as the emotive force behind critical junctures in the history of women’s rights.

The story of the World’s Anti-Slavery Conference was central to these narrative effects. The events of 1840 were well known among the community of feminist abolitionists both in the US and the UK, with key figures, including Anne Knight, having been personally present. Casting this event as the fulcrum of feminism’s relationship to antislavery, however, and suggesting a sense of competition between abolitionists and women’s rights advocates, was an innovation by the editors. Though Stanton attributed momentous significance to her meeting with Lucretia Mott, Mott’s diary does not suggest that she attached any such special consequence (Sklar Reference Sklar, Yellin and Van Horne1994; Tetrault Reference Tetrault2014, 27). Moreover, when Stanton suggested women’s activism had started in 1840 in personal correspondence, Mott corrected her to suggest that honour instead went to the 1837 National Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women (Tetrault Reference Tetrault2014, 16). The 1840 Convention and subsequent Seneca Falls Convention were made central because that was Stanton’s experience, casting her as a direct foremother of the suffrage movement and developing the broader theme of abolitionists’ betrayal.

Foregrounding the historic significance of women’s exclusion at the Convention contributed powerfully to the theme of betrayal that rings throughout Stanton and Anthony’s account of those early decades. To bolster the impression of 1840 as an instance of disloyalty, the HWS’s opening narration of events presented the rejection of women’s participation as having been unexpected:

The call for that Convention invited delegates from all Anti-Slavery organisations. Accordingly several American societies saw fit to send women, as delegates, to represent them in that august assembly. But after going three thousand miles to attend a World’s Convention, it was discovered that women formed no part of the constituent elements of the moral world. In summoning the friends of the slave from all parts of the two hemispheres to meet in London, John Bull never dreamed that woman, too, would answer to his call.

In reality, the Garrisonian delegation had anticipated the controversy in London. The question of women’s role in the cause had caused a rift among American abolitionists the year before, resulting in the split of the American Anti-Slavery Society between the Garrisonians and the more conventional followers of Arthur and Lewis Tappan, who opposed women’s public advocacy. Moreover, when the London organisers received word that Garrisonians intended to send female representatives to London in February, they immediately sent a statement specifying that only male delegates would be welcome (British and Foreign 1841, 25). Garrison’s correspondence shows he considered it ‘quite probable, that we shall be foiled in our purpose’ (quoted in Sklar Reference Sklar1990, 463). By presenting this event as unpredicted, the HWS emphasised the experience of betrayal at abolitionists’ supposed abandonment of the women’s cause, foreshadowing the conflict of the 1860s. Heightening the pathos of this moment, the writers represented a visceral shared experience of indignation as the springboard for the first women’s rights movement. This decision universalised Stanton and Anthony’s experience to a supposedly movement-wide dynamic.

The indignation of women’s advocates was a frequent motif of the HWS and was described in detail in the discussion of the World’s Anti-Slavery Congress. Moreover, Stanton specified that it was only women who experienced it, providing ammunition for the argument that only women could adequately represent their sex. Even while praising the efforts of Wendell Philips, she reflected on his reconciliatory rhetoric, after the motion to include women delegates had been defeated:

Would there have been no unpleasant feelings in Wendell Phillips’ mind, had Frederick Douglass and Robert Purvis been refused their seats in a convention of reformers under similar circumstances? and, had they listened one entire day to debates on their peculiar fitness for plantation life, and unfitness for the forum and public assemblies, and been rejected as delegates on the ground of color, could Wendell Phillips have so far mistaken their real feelings, and been so insensible to the insults offered them, as to have told a Convention of men who had just trampled on their most sacred rights, that ‘they would no doubt sit with as much interest behind the bar, as in the Convention’? […] [Phillips] might be considered as above criticism, though he may have failed at one point to understand the feelings of woman. The fact is important to mention, however, to show that it is almost impossible for the most liberal of men to understand what liberty means for woman. This sacrifice of human rights, by men who had assembled from all quarters of the globe to proclaim universal emancipation, was offered up in the presence of such women as Lady Byron, Anna Jameson, Amelia Opie, Mary Howitt, Elizabeth Fry, and our own Lucretia Mott.

Extending the insult to the English women present, and not just American delegates, this indignation was presented as a motor of feminism internationally.

Outrage took on still more prominence in the second volume, first published in 1882, which picked up the historical narrative from 1861 to 1876 and narrated the tensions around the Fifteenth Amendment. The increasing conflicts arising from the experience of competition between the interests of black men and suffragists is at times presented as a tragic split, at times as a philosophical question, and at times as a source of righteous anger. Some passages, particularly printed speeches by George Francis Train, the racist Democrat whom Stanton supported much to the Republicans’ dismay, hinge on the blatant stoking of racist sentiments. Other passages, however, reflected on the split more thoughtfully:

It has been a great source of grief to the leading women in our cause that there should be antagonism with men whom we respect, whose wrongs we pity, and whose hopes we would fain help them to realize. When we contrast the condition of the most fortunate women at the North, with the living death colored men endure everywhere, there seems to be a selfishness in our present condition. But remember we speak not for ourselves alone, but for all womankind, in poverty, ignorance and hopeless dependence, for the women of that oppressed race too, who, in slavery, have known a depth of misery and degradation that no man can ever appreciate.

None of the European accounts retained this ambivalence around the tactical question of how to approach rights advocacy. As will be shown, instead the idea of opposition between black men and white women was dramatised and made into a vivid illustration of illiberal dangers the authors saw encroaching on women’s rights progress. Tetrault remarks how the second volume ‘brims with indignation, understandably – but sadly and painfully, it also brims with elitism and racism’ (2014, 130). Looking at the take-up of the antislavery origin myth casts further light on the interplay between these different pillars of the story. Indignation was not just a natural outflow of the historic events, but was powerfully strategic as a transculturally legible motivator, and elitism and racism proved useful handmaidens to this feat of imagination.

Feminist Internationalists and the Antislavery Origin Myth

Though the story of the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention first found its currency in the national context of women’s advocacy in America, Stanton and Anthony were eager to broadcast it internationally. As Mineke Bosch and Leila Rupp have documented, the late nineteenth century was a high point for organised internationalism and Stanton and Anthony had made first efforts towards an international women’s association during their visit to Europe in 1882. In her study of the International Council of Women (ICW, 1888), the eventual outcome of Stanton and Anthony’s ambition, the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA, 1904), and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (1915), Leila Rupp showed how, at the turn of the century, many influential middle- and upper-class feminists prioritised international organisation and used organisational and symbolic means to forge a transcultural identity of ‘universal sisterhood’ (1997, 82–83). This construction was, as many critics have pointed out, less inclusive than it sounded. In their study of IWSA correspondence, Bosch and Annemarie Kloosterman demonstrated how the maintenance of international friendships between leading feminists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Aletta Jacobs, and Rosika Schwimmer, in their ‘prosaic’ organisational and ‘poetic’ rhetorical dimensions, left a lasting mark on women’s political culture and ‘suffrage sisterhood’ (Bosch and Kloosterman Reference Bosch and Kloosterman1990, 21–23). This movement of feminist internationalism was marked by its association with middle- and upper-class leading figures; other internationalisms, such as that among socialists, had different aims and organisational concerns (DuBois Reference DuBois, Daley and Nolan1994; Moynagh and Forestell Reference Forestell2012, 9; Carlier Reference Carlier, Janz and Schönpflug2014; Oesch Reference Oesch2016).

By the 1880s, the United States had become an ineluctable point of comparison for European commentators. As French lawyer and women’s rights advocate Léon Giraud estimated, in civilisational stadial discourse characteristic of this branch of feminist internationalism (Burton Reference Burton1994; Midgley Reference Midgley2007), Americans, with their advanced suffrage campaign, educational, and travel opportunities for women, were as far ahead of Europeans as Europeans were of ‘Orientals’. Having taken an organisational head start, it is little wonder that American ideals and models quickly took on primacy within much feminist internationalism (Offen Reference Offen2017, 235; Gehring Reference Gehring2020, 308ff.). The ICW and IWSA prioritised key American concerns, including American suffragists’ relatively conservative preoccupation with unity, collective identity, and ideological harmonisation at the expense of radicalism and diversity (Rupp Reference Rupp1997, 15–21; Carlier Reference Carlier, Janz and Schönpflug2014). In addition to the use of folkloric symbolism and the forging of a shared language, calling this unity into being involved memory work and this internationalist campaign left distinct marks on early feminist self-historicisation.

The significance of memory in this crystallising vision of international feminism speaks from the inaugural congress of the ICW in Washington DC. International events were an important stage for constructing a unified vision of international feminism and its history and this event was organised in honour of the fortieth anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention. Tireless cultural brokers like May Wright Sewall, Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s émigré son, Theodore Stanton, and French Isabelle Bogelot organised international meetings alongside fairs and exhibitions, including the Paris Exposition of 1889, the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, and the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900 (Offen Reference Offen2018). As Tracey Jean Boisseau suggests, international gatherings and particularly women’s exhibitions, such as the Dutch National Exhibition of Women’s Labour in The Hague, offered an ‘aspirational fantasy’ of what woman’s world might look like, to both domestic and foreign visitors (2018, 248; Grever and Waaldijk Reference Waaldijk, Grever and Dieteren2000; van den Elzen Reference van den Elzen, Paijmans and Fatah-Black2025). Occasions like these, rich in symbolism, broadcast a vision of the world where women’s differences were celebrated and did not mar the general harmony of sisterhood and in which self-actualised women worked to bring peace, progress, and prosperity to their families, their nations, and the world – and had been doing so for decades.

Several American delegates used the platform of the 1888 ICW Convention to tell the story of World’s Anti-Slavery Conference. Stanton opened her speech by describing her experience in London (1888, 322–323). The story also featured in Rev. Annie H. Shaw’s opening sermon before the formal opening on 25 March. Shaw mused:

Who would have dreamed, when at that great meeting in London some years ago the arrogance and pride of men excluded from its body the women whom God had moved to lift up their voices in [sic] behalf of the baby that was sold by the pound, who would have dreamed that that very exclusion would be the key-note of woman’s freedom? […] That out of a longing for the liberty of a portion of the race, God should be able to show to women the still larger, grander vision of the freedom of all human kind?

As Shaw’s speech indicates, by 1888 the antislavery origin myth had gained currency and speakers glossed over the details in order to develop its full dramatic potential, using the humble origin story to point to men’s hypocrisies and the ‘grand’ nature of their movement. As Harriet Robinson put it in her article on American feminism for a French audience, by now there was ‘no doubt that the anti-slavery movement gave the impetus to the movement for the emancipation of women, and that not only in the United States, but perhaps even in England and other countries […]’ (1898, 248).

The editors of the HWS were eager to get their stories, as well as the calf-bound volumes of the work itself, to readers in Europe. Anthony, who was particularly motivated in her quest to circulate the book widely, even if this meant foregoing profits, frequently gave away copies of the expensive work to Congressmen and other influential readers at home and abroad and distributed around 1,000 copies to European and American libraries (Kelly Reference Kelly2005, n.p.; Tetrault Reference Tetrault2014, 143–144). The most important broker for the story in Europe was Theodore Stanton. He promoted the account of the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention on multiple occasions, including in his speech at the 1878 International Women’s Rights Conference in Paris (Stanton Reference Stanton1878, 36–37), where he analysed the ways in which women’s rights advocates had become emboldened by their antislavery activism. The report of this event indicates that French audiences were not necessarily well versed in the particulars of the American story; the compiler referred to Garrison as ‘William Llayd Garnom’ (Stanton Reference Stanton1878, 37). Stanton’s analysis evidently impressed several European delegates and Léon Giraud closely reproduced it in his own history (1883, 303). Theodore, working on a first comparative history of feminism (Stanton Reference Stanton1884), distributed fifty copies of the HWS, fresh off the press, among his collaborators, all eminent women’s rights advocates of their day (Bosch Reference Bosch2009, n.p.). Among European readers the story would soon take on a significance of its own.

Women’s Progress and Women’s History in Europe

Anthony and Stanton’s efforts hit their mark and the HWS became an important source for European students of the history of this big social question of the day. The antislavery origin myth diffused among European women’s rights circles, becoming a key part of the account of American feminism told in the radical press, in pieces like Käthe Schirmacher’s article series on ‘Le féminisme aux États-Unis’ for La Fronde (1898), and Evolutie’s account of the historical importance of Elizabeth Cady Stanton (‘12 November’ 1895, 302), and in popularising studies such as Avril de Sainte-Croix’s Le féminisme and Martina Kramers’ articles in the prestigious Dutch literary magazine De Gids, where it attested to the philanthropic genesis of women’s rights activism (Sainte-Croix Reference Sainte-Croix1907, 99; ‘De plaats der vrouw’ 1907, 259).

When the Paris Law School announced its prestigious annual Rossi constitutional law essay competition for 1891 on the subject ‘The condition of women from the point of view of the exercise of public and political rights: a comparative study of legislation’ (Mossman Reference Mossman2006, 255), the three prize-winning contributions by Giraud, Louis Frank, and Moïse Ostrogorski all used the HWS as their source for data on the US (Giraud Reference Giraud1891; Frank Reference Frank1892; Ostrogorski Reference Ostrogorski1892). These studies were well received (Grasserie Reference De la Grasserie1894, 432ff.) and Ostrogorski’s treatise was translated into English in 1893. Whereas Giraud and Frank were women’s rights advocates, Ostrogorski considered himself neutral on the issue (1892, 192). He nevertheless affirmed the authority of the HWS when he explained:

It was the abolitionist movement which paved the way for Women’s Rights. Claiming for the negro the rights inherent in human nature, the abolitionists insisted on the complete equality of mankind, which rejects every distinction, especially if based upon physical qualities. If white men had not the monopoly of liberty, if blacks too had an equal right, could women be shut out from this?

Ostrogorski’s reproduction of the antislavery origin myth as setting in motion suffragist reasoning attests to the general acceptance of this story not only as objective truth, but as common knowledge.

As the works cited indicate, the late nineteenth century was a fertile time for feminist knowledge production and particularly for women’s history. While academic historians were busy professionalising their discipline as the ‘heroic study of records’ (Lord Acton [1895], quoted in Smith Reference Smith1998, 125), scholars, philosophers, and belletrists met the public fascination with women’s changing social role with ambitious attempts at defining woman’s place in world history. Works like Bachofen’s Mutterrecht und Urreligion (1851), which speculated about the existence of ancient ‘gynecocracies’ (matriarchies), and Jules Michelet’s L’Amour (1859) and La Femme (1860), which sacralised women’s role in the home and suggested women’s power worked counter to linear history (Moses Reference Moses1984, 152ff.; Gaudin Reference Gaudin2006, 48), were widely read and discussed. Other projects, like Olympe Audouard’s unfinished series Gynécologie: La femme depuis six mille ans (1873), tried to tell the story of women’s history since biblical times, tying the rise of modern woman to the rise of Christianity much like the romantic socialists of the 1830s had attempted.

Women’s rights advocates saw an opportunity in the general (amused) fascination with women’s history. As Gisela Bock has pointed out, proponents of women’s rights had different master narratives available to them to legitimate the aspirations of the women’s movement (Bock Reference Bock2002, 117). There was a well-established tradition of examining the question of woman’s genius by way of accounts of the lives of great women in history, which had been the dominant genre until the mid-nineteenth century (Grever Reference Grever1994; DiCenzo Reference DiCenzo2005, 43; Ernot Reference Ernot2007, 167–168; Offen Reference Offen2018, 73ff.). But with five decades of public campaigning under their belt, women’s rights activists now also turned to historical interpretation, and particularly to the fashionable master narrative of progress, to narrate how the first steps towards emancipation, and towards the final break with age-old despotism, were presently being made.Footnote 5 They participated in a major historical trend which would, in the English context, come to be termed the ‘Whig interpretation of history’ (Butterfield Reference Butterfield1965): glossing over factional differences and dead ends, the authors and editors set out to tell a unifying story of women’s part in the ‘progress’ which had become the byword of nineteenth-century reform culture.Footnote 6 The rhetorical power and general popularity of history in this mode inspired several ambitious projects to chronicle the history of the international women’s movement in the same way as Stanton and Anthony had achieved for the American. Initially, authors like Theodore Stanton and Käthe Schirmacher set out to appeal to liberal common-sense attitudes by addressing readers in the non-partisan, scientific register of supposedly universal appeal. Later on, truncated programmatic versions of these histories appeared, promoted especially by the NAWSA to rally their membership. Casting America as the pinnacle of women’s progress, women’s historians were unerringly interested in the relationship between antislavery and the story of feminism. Losing its specific cultural, political, and factional context in the process of translation, however, the antislavery origin myth came to be caught up in European racial anxieties and in a broader structuring mechanism of ‘ethnological order’ that pervaded feminist internationalism (Bosch Reference Bosch2009).

Comparative Histories and the Ethnological Order

The Woman Question in Europe (1884) was the most direct descendant of the HWS and, as Bosch has noted, its representational choices yield insight into how the American perspective was received in Europe (2009). Theodore Stanton organised its composition under his mother’s guidance. The book presented a collection of contributions on the history of the women’s movement in various European countries, written by leading campaigners such as Millicent Garrett Fawcett and accompanied by an introduction by well-known Anglo-Irish reformer Frances Power Cobbe. Bosch has discussed how the idea for the book was first conceived in the process of collecting materials for the HWS (2009, n.p.) and its form closely follows this model. The Woman Question in Europe shared its professed forward-looking perspective to service future scholars, as well as its emphasis on the individual initiative of leading women. Stanton stressed the pains he took to ensure historical accuracy, so that the work could serve as the basis of a later ‘philosophical investigation’ (1884, vii). The eminent standing of all the contributors within the women’s movement is emphasised not only in the introduction, but also in a lengthy biographical note opening each chapter. Stanton downplayed his own role in the volume as a mere compiler, translator, and editor (1884, viii). His many footnoted comments, however, suggest the extent of his editorial control (Bosch Reference Bosch2009, n.p.). They indicate the tension between the desire to conceptualise the women’s movement as a transnational community, expressed in the invitation of different voices into the narrative, and an urgent need to keep tight control over the definition of women’s progress.

This tension also determined the thrust of Cobbe’s introduction. Using the metaphor of a tidal wave, Cobbe described a ‘uniform impetus’ which ‘has taken place within living memory among the women of almost every race on the globe [and] has stirred an entire sex, even half the human race’ (Stanton Reference Stanton1884, xiii–xiv). Thus, stressing that the national initiatives described in the chapters that followed took the same shape, she posited that political franchise would prove the single ‘crown and completion of the progress’ (Stanton Reference Stanton1884, xv). Whereas in previous decades it had been customary for feminist organisers to express solidarity and emphasise similarities between victims of different forms of oppression, Cobbe insisted on keeping emancipation movements for ethnic groups and for women separate, both practically and conceptually. She warned colleagues to distance themselves from what she called ‘experiments fraught with difficulty and danger’, the extension of suffrage to men of ‘alien races’ whom she considered untrained in civil liberty and representative government (Stanton Reference Stanton1884, xv). Despite her initial metaphor and running somewhat at odds with Stanton’s aims, in making this argument she soon reverted to singling out for praise the ‘Anglo-Saxon race’ (Stanton Reference Stanton1884, xv). Cobbe leaned into the master narrative of general progress to argue that including white women in the franchise would represent a next step forward as they would ‘[bring] with them, not an element of weakness and disintegration, but a completer union’ (Stanton Reference Stanton1884, xvii, my emphasis) – and brought none of the dangers of enfranchising ‘rival races, rival classes, rival sects’. Her emphasis on competition with, and even danger from, the groups described as ‘untrained’ and ‘illiterate’ conveyed the tacit assumption that only white, middle-class women partook in the general upward tendency (see also Hamilton Reference Hamilton2001).

Stanton explained that he grouped his chapters in an ‘ethnological order’ (Stanton Reference Stanton1884, vi), presenting certain countries together. His ordering was suggestive and reinforced the narrow, liberal definition of progress his circle had in mind; he opened with ‘Anglo-Saxon’ England (138 pages), followed by Germanic (‘Teutonic’) nations (42 pages), Scandinavian countries, Latin states, ‘Latin-Teutonic’ countries (Switzerland and Belgium), and Slavonic states before ending with a single chapter on the Orient (15 pages). The chapter on the Orient is itself again hierarchically divided; Athens-educated, Greek nationalist contributor Kalliope Kehaya distinguished between Greek women in Greece, Christian Greek women under a ‘foreign yoke’ (Stanton Reference Stanton1884, 458), and Oriental women, among whom she counted Ottomans and Jews. The latter category she not only determined to be irrelevant to this history, but to history in general: ‘I shall say but little concerning these latter races, for their women are in a state of lamentable inactivity which offers almost nothing worthy of record’ (Stanton Reference Stanton1884, 458). Though Stanton did not say so explicitly, this multi-level imaginative ordering identified the movement’s impulse and agency on a gradient, with white, Protestant, middle-class women at the top.

The Woman Question in Europe, so closely connected to the HWS, in turn served as a source for a comparative study by a young German expatriate academic, Käthe Schirmacher’s Le féminisme aux États-Unis, en France, dans la Grande Bretagne, en Suède et en Russie (1898), and the Geschichte der Frauen in Kulturländern by the veteran editors of Die Frau, Gertrud Bäumer and Helene Lange, who had co-founded the IWSA. Le féminisme, published in Paris, sought to portray the women’s movement as a sociological phenomenon which was a natural outflow of societal progress. Schirmacher took pains, however, to emphasise the limited range of her study and to reflect on national differences, ending each chapter by discussing the strengths of the particular national branch of feminism under discussion (see also Gehmacher Reference Gehmacher2024, 256–257). Nevertheless, she offered the tentative conclusion that feminism is an international movement which is in every context born from the same ‘intellectual, moral and economic causes’ (Schirmacher Reference Schirmacher1898, 71), pointing out that early feminists everywhere combined their agitation for women’s rights with concern for other social causes. She also stressed that for countries where women’s rights had not progressed far, it should not be attributed to the women, nor to ‘ethnic differences’, but to insufficient progress of ‘the idea of social justice’ (73). Rather than an exhaustive overview, then, Le féminisme presented the differences between the movement in different national contexts as a resource and source of inspiration. The introduction explains that factual and statistical accuracy, as well as detailed contextualisation when necessary, took precedence over reading pleasure, positioning the work as a resource for historical knowledge rather than as propaganda. Nevertheless, this conception of difference as a resource only extended to middle-class traditions in Western countries. Except for France, Schirmacher contended, no socialist feminism existed (72) and, regarding non-Western traditions, it is indicative that she introduced Russia as a victim of Asian influences to explain Russian women’s domestic confinement: ‘Situated on the borders of Asia, Russia has not been able to elude certain Oriental influences’ (60).Footnote 7 Schirmacher’s account stressed the importance of developing a sufficiently liberal society for women’s rational advocacy to have any success. In accordance with this, she presented a similar ‘ethnological order’ as the Woman Question in Europe, ranging from her favoured example of the United States to Russia, where pioneering individuals had not yet been able to make a dent (Schirmacher Reference Schirmacher1898, 68).

Helene Lange and Gertrud Bäumer’s Geschichte der Frauen in den Kulturländern formed the first part of their four-volume Handbuch der Frauenbewegung (1901). In addition to a 158-page history of the German women’s movement, they collected contributions detailing the history of the movement in 15 European nations, as well as Russia and the US. They hoped that, by providing a handbook, they could unite women’s individual efforts into a larger movement:

So many work industriously on little tasks, without connecting these to the grand goal, which they too help achieve, and some stand at the rudder without having a compass, exploring opportunities for development, where they haven’t learned, from the history of the movement, its developmental laws.

Lange and Bäumer explained they not only wanted to provide women activists with historical knowledge, but also to demonstrate the transnational ‘Gesamtentwicklung’ by prioritising coherence (Einheitlichkeit) over including all details: ‘The expanded propaganda is more prone to lead one astray, than to orient her’ (1901, vi).Footnote 9 Their coherent narratives served to prove, for each national case, that the women’s movement was not an economic side-effect, but originated in women’s social initiative, which they in turn deemed a ‘cultural inevitability’ after the Enlightenment (ix). With this argumentation, they sought to promote moderate, but persistent awareness-raising over more radical approaches they considered publicity stunts ‘geräuschvolle Agitation’ (ix).

Their aim of providing readers with an arsenal to argue for the inevitability of women’s emancipation specifically post-Enlightenment goes some way in explaining their interest in only those countries they considered Kulturländern. As the endpoint to their story, they took national women’s movements’ entrance into international alliance. Colonial contexts were not discussed, as the editors considered that explaining their historical circumstances would require too much space (Lange and Bäumer Reference Lange and Bäumer1901, 286). Geschichte der Frauen aimed to provide feminists with a specific usable past that they could incorporate into their own argumentation, which emphasised the cultural effects of women’s agitation. This aim suffused the volume, even if the editors made substantial efforts to collect detailed, authoritative contributions on the countries they surveyed. Like Stanton and Schirmacher, Lange and Bäumer promoted a stadial view of world history. They encouraged women to affiliate with a transnational sisterhood and even went so far as presenting this as the most advanced stage of feminism. However, they allowed for asymmetry in this affiliation, with the onus primarily on women that were ‘behind’ – and their work on Kulturländern facilitated, and implicitly invited, this unilateral connection.

The three cases so far were presented as scholarly resources. A decade later, however, two popular programmatic comparative surveys appeared which, undisturbed by resilient facts or recalcitrant contributors, further crystallised an asymmetric sisterhood through a unifying narrative of historical progress grounded in racialist logic: Käthe Schirmacher’s Die Moderne Frauenbewegung (1905; second edition 1911; English trans. 1912) and Alice Zimmern’s Woman Suffrage in Many Lands (1909; second edition 1910; French trans. 1911). Both are prime documents of feminist internationalism. They were used as semi-official handbooks by the IWSA (Van Voris Reference Voris1996, 230; Gehmacher Reference Gehmacher2024, 156) and were widely recommended by IWSA’s president Carrie Chapman Catt, who had also written the introduction to Zimmern’s volume. These works built on and cited the more scholarly volumes. However, affiliated as they were with the IWSA, they went further in their urge to unify and homogenise their vision of the international women’s movement, describing it as suffrage-oriented and emphasising how white, middle-class women from the US and Western Europe took a leading role.

Like her earlier work, Käthe Schirmacher concluded her Moderne Frauenbewegung by placing her hope in education: ‘Education is surely a slow process, but it is also “everything to be hoped for”, and once “ideas” will have seized the masses, they will be an irresistible victorious force’ (1905, 130).Footnote 10 But where Le féminisme still positioned itself as a scholarly resource and stressed gradual development, Moderne Frauenbewegung strikes a different tone. Le féminisme explicitly left indeterminacy in its conclusions, suggesting that the study of other national contexts might further enrich the understanding of the women’s movement. Moderne Frauenbewegung instead doubled down on the master narrative of liberal progress, presenting women’s history as a battle between Enlightened liberal progressivism and barbaric backwards attitudes. It attested to the conversion Schirmacher, an indispensable translator for the feminist internationalist movement, had undergone, from being a committed internationalist to a fierce proponent of ethnic nationalism and German expansionism (Gehmacher, Heinrich, and Oesch Reference Gehmacher, Heinrich and Oesch2018, esp. 386ff.; Gehmacher Reference Gehmacher2024, esp. 9–11, 283ff.). Moderne Frauenbewegung cast women’s emancipation as an achievement of Germanic protestant culture, with its ‘more robust training in one’s independence and sense of responsibility’ (Schirmacher Reference Schirmacher1905, 1), in need of protection against a hostile world.Footnote 11

Schirmacher relied on Orientalist and racial othering to concretise this central conflict in the book (Gehmacher, Heinrich, and Oesch Reference Gehmacher, Heinrich and Oesch2018, 386ff.). Die Moderne Frauenbewegung again discussed the progress of the women’s rights movement divided by national context, ordering countries into ethnic groupings. The survey begins with an eighty-six-page section on Germanic countries, in which, unusually enough, she included both her favoured example of the United States and even the UK, and ended with the ‘Orient and Outer Orient’, in a section taking up only nine pages. In the section introduction, Schirmacher explained that the women’s movement had been most successful in Germanic countries because of moral and economic factors, the superiority of Protestant values and education, and the fact that in Germanic countries, women outnumbered men (Schirmacher Reference Schirmacher1905, 1). She suggested that women’s movements in Slavic countries, discussed in the second to last section, had only little success as these countries ‘lack an old and deep Western European culture. Everywhere have oriental conceptions of women’s character left persistent traces’ (108).Footnote 12 Though suggesting any protest against men’s power is ‘women’s movement’, Schirmacher explicitly called on white women to lead organised feminism to global success. In the work’s introduction, which presented the ICW, IWSA, and the World’s Christian Temperance Union (1873) as the high point of the movement, she wrote: ‘Leadership in this movement has fallen to the women of the white race, and among them, to American women’ (iii).Footnote 13

Schirmacher’s brief sections on the Orient, which included Turkey, Egypt, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Persia, India, China, and Japan, served to evoke the sense of an overwhelming oppositional force working directly at odds with liberal progress globally. She attributed women’s rights activity in these regions to individual praiseworthy Western initiatives (Schirmacher Reference Schirmacher1905, 129). She also explicitly identified examples of illiberalism in European countries with ‘barbarism’ in the Orient: ‘Here [in the Orient] woman, nearly without exception, is a mere toy or pack animal, to such an extent that it viscerally affects us Europeans. Of course analogies may be found with us, and these unfortunate backslides into barbary cannot be reprimanded and despised enough’ (120).Footnote 14 She returned to the central theme of a struggle between Enlightened ‘Germanic’ liberal progress and Oriental barbarism in the brief conclusion of the work, opening it by ominously reminding readers of the staggering numbers of unfree women globally: ‘In the greater part of the world, woman is a pack animal or slave [footnote: 825 million inhabitants in Asia, 200 in Africa!] […] Even in a large number of the countries that have European civilisation, woman remains mute and unfree’ (129).Footnote 15 Schirmacher expressed no further expectation of progress outside of the West in the first edition. The second edition ends on a more hopeful remark on the further development of the women’s movement in European countries, and the ‘awakening of women even in the depths of old Oriental civilizations’ (Schirmacher Reference Schirmacher1909, 146).Footnote 16

In the perspective Schirmacher developed, the Germanic West transformed into a progressive bastion against an overwhelming tide of backwardness and barbary. Even though the short section on the Orient contained little historical analysis, it was of structural importance to the book. Schirmacher sought to agitate her readers by painting a picture of embattled Western liberal values, of which feminism was the most progressive and most precarious. This progress was up against an Orient which, rather unlike Europe’s timeless Other (Said Reference Said2006), transformed into an active purveyor of the ‘barbary’ from which Europe only recently distanced itself and into which it may very well ‘backslide’. Where Le féminisme left open the possibility for gradual progress, Moderne Frauenbewegung cast the international movement for women’s rights as an active battlefield into which readers were to be recruited.

English suffragist Alice Zimmern’s booklet Women’s Suffrage in Many Lands (1909) was published to coincide with the fourth congress of the IWSA and quickly received a second printing and French translation. The work is organised in the same chapter-per-country fashion as the others, starting with the US and ending with chapters on South Africa and Australia and New Zealand. Zimmern explains that she had to confine herself to those countries where there was sufficiently organised effort, which meant her selected cases ‘are for the most part members of the [IWSA]’ (1909, iii). Whereas Lange and Bäumer’s Geschichte addressed itself to readers already affiliated with the movement, Zimmern’s account was also meant to extend to a general audience. In her foreword, Carrie Chapman Catt wrote that after a long period of quiet suffrage efforts, ‘now all the world is talking of it, and is asking questions concerning its past, its present, and its future aims. This little book will answer those questions’ (Zimmern Reference Zimmern1909, i). Considering Zimmern’s association with the IWSA, it is little wonder that Women’s Suffrage presented the right to vote as the women’s movement’s ultimate goal and downplayed the importance of other emancipatory claims. Accounts of suffrage activity and internationalisation round out most chapters. Catt’s foreword made explicit the conformity which Zimmern’s survey sought to prove: ‘The history, with change of scene and personality of advocates, is practically the same in all lands; a struggle against similar customs and traditions which have held women in universal tutelage’ (Zimmern Reference Zimmern1909, i).

Like Schirmacher, Catt wrote her foreword in an embattled tone:

[Readers] cannot fail to be impressed with the international character of the movement for the enfranchisement of women. […] The movement represents a universal awakening of women and a universal appeal to the world to recognise that women as well as men are people, with distinctive interests to be protected, and that all representative governments are mere travesties of justice unless they endow women and men equally with the ballot.

Though less steeped Orientalism than Moderne Frauenbewegung, which was a main source for Women’s Suffrage (Zimmern Reference Zimmern1909, ii), Catt similarly pits women’s emancipation against an enemy of backwardness and barbarism. Zimmern’s chapters pruned national histories to represent suffrage and international organising as the state of the art in feminist development and the bar by which individual countries were to be judged.

Whether purporting to be historical reference works or more straightforwardly argumentative, all comparative histories made the case that international women’s rights advocacy enjoyed a uniform development which culminated in suffragism, both explicitly and implicitly. It is little wonder that the early twentieth-century texts, appearing in the heat of the suffrage campaign, were so focused on mobilising their readers with a strong central thesis. On closer examination, however, both the scholarly and the programmatic works substantially regulated the way their readers related to the past. They ultimately portrayed a single transnational movement, arising from the same sources and obeying the same developmental laws. In addition to this fundamental connective strategy, the authors also emphasised explicit analogical developments and instances of transnational cooperation. Zimmern was fond of pointing out historical parallels, like the one between the British Anti-Corn Law movement and antislavery: ‘To many Englishwomen this proved the inspiration which the anti-slavery agitation had been to Americans. It helped them too to realise how closely politics affected their own lives’ (Zimmern 1909, 19, 20). Schirmacher highlighted transnational interconnection by emphasising interpersonal exchanges, mentioning, for instance, that Susan B. Anthony had visited the Berlin international congress in 1904 (Schirmacher Reference Schirmacher1905, 5), and stressing the German influence on American suffragism: ‘It should be emphasised that there was a number of European women who, filled with the ideas of the February Revolution of 1848, had to seek a new home in America (among these was Westfälin Ernestine Rose), who promoted the women’s suffrage movement among American women through their lively propaganda’ (Schirmacher Reference Schirmacher1905, 5).Footnote 17

Each history offered a slightly different, restrictive entrance to an international imagined community, as their stated goals and approach brought along specific omissions, distortions, and excisions. Over the course of the development of this feminist internationalist knowledge production, and most overtly in Zimmern and Schirmacher’s later work, liberal, white middle-class stories were turned into the ‘official’ history of women’s political activism and agency and women’s rights progress was measured by the yardsticks of liberal ideology, organisational impulse, and the prominence of the demand for suffrage. Relying on the popular narrative of liberal progress, and refashioning it to suit their own purposes, they navigated the contradiction between their stated ambition to chronicle different histories and their need to communicate a strong sense of ideological unity. The antislavery origin myth, which proliferated throughout these histories and beyond, was an important site within which these feminist internationalist conceptions were both legitimised and dramatised.

European Lives of the Antislavery Origin Myth

Without fail, the European accounts presented the antislavery–feminism relationship following the basic narrative promulgated in the HWS. Antislavery was presented as the ‘first definite impetus’ for women’s organised action (Zimmern Reference Zimmern1909, 2). Early female orators like Angelina Grimké were invoked to show how the ‘fight became a school’ for women’s rights (Giraud Reference Giraud1883, 303) and readers were told how disagreement over the propriety of women’s active participation and assumption of public functions such as speaking engagements increasingly became a ‘wedge’ in the ‘ranks of the abolitionists’ (Strinz in Lange and Bäumer Reference Lange and Bäumer1901, 460). Key to this narrative, as discussed, was the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention and Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, who, following the ‘great humiliation’ (Schirmacher Reference Schirmacher1898, 7) of their exclusion from the Convention, resolved that ‘they too would summon a congress, but its aim should be the deliverance of women from bondage’ (Zimmern Reference Zimmern1909, 4, my emphasis). This ambition, it is suggested, became reality with the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848.

All authors affirmed the special status of 1840; Robinson wrote that ‘it was then that the fight for the enfranchisement of woman really began’ (1898, 249)Footnote 18 and Giraud described Stanton and Mott’s decision ‘like a new oath of Hannibal’ (1883, 302).Footnote 19 The events of 1840, and the conflicts around the extension of suffrage to black men in 1869–1870, were presented as pivotal moments when female abolitionists realised the injustice, or even hypocrisy, of their own subordination. Both the narrative details and the irony of the original passage found their way into European accounts. Giraud reproduced the detail that Stanton and Mott made their decision during a ‘nocturnal walk in the streets of London’ (1883, 302) and Cauer reimagined the event with dramatic flair:

On the evening of this memorable day two representatives of the female sex walked up and down the foggy streets of London for hours, in a state of deep excitement. They were Lucretia Mott and Mrs. Stanton […]. It was on the pavement of ‘Old England’ that the decision to found an association for women’s rights was made.

Cauer not only changed the staging of the scene; she also replaced the irony of the original with a tone of earnest solemnity when she reports the inception of the idea. Zimmern, on the other hand, reintroduced irony in her retelling of the vignette, telling readers that Stanton and Mott ‘resolved that when they returned home they too would summon a congress, but its aim should be the deliverance of women from bondage’ (1909, 4, my emphasis).

Despite the efforts of Americans like Stanton to embed this particular American narrative into the movement, the adoption of the basic timeline of the HWS and its hostility towards abolitionists into these European histories were choices, not inevitabilities. Other accounts of the history of organised women’s rights advocacy were available, such as Paulina Davis’ History of the National Woman’s Rights Movement for Twenty Years (1871), which took the 1850 Worcester Women’s Rights Convention as the starting point of the movement and had served as a source for the ‘Kurze Übersicht der amerikanischen Frauenbewegung’ which the Frauenanwalt published in 1873; or Harriet Hanson Robinson’s Massachusetts in the Woman Suffrage Movement (1881), which emphasised the role of working-class women in the movement and which she publicised in a French quarterly (1898).Footnote 21 Moreover, on numerous points, the European histories did significantly depart from the HWS. As Figure 5.1 shows, the antislavery origin myth was unique in its centrality and many other stories of American feminism were also told. However, this story held several advantages for European authors, who used it for its powerful legitimising and affective potential and contributed to its consolidation as a key site to promote international sisterhood. It was used to suggest a philanthropic genealogy for the demand for women’s suffrage, to legitimise recasting the women’s movement as one primarily about the right to vote, and was retold in an emotive way to promote affiliative fellow-feeling with the American movement leaders. This utility contributed to European writers elevating the story into a central element of the usable past of middle-class feminist internationalists.

Figure 5.1 Networked representation of the ‘events’ (black) and ‘persons’ (white) mentioned in 7 comparative histories (grey) of American feminism as told in seven comparative histories. There are only four shared nodes between all works: Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, 1840 World’s Antislavery Convention, and the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention.

The antislavery origin myth was used to illustrate and evidence an inextricable relationship between women’s rights advocacy and philanthropy, which legitimised the movement among middle-class readerships. As discussed in the previous chapter, this philanthropic genealogy was useful as it framed traditionally feminine virtues as a proper basis for women’s active citizenship. As a bestselling Dutch feminist novel, Hilda van Suylenburg, put it in 1897:

Women have always passionately participated in all great movements that animated her time: Christianity, the French Revolution, the American emancipation of the slaves, etc., etc., and nowadays, too, there really isn’t a serious movement that does not sport its female champions.Footnote 22

Bourgeois feminists promoted this ideal in their self-historicisation, as the setup of Naber’s Wegbereidsters (1909) and Lange and Bäumer’s systematic survey of German women’s humanitarianism in the second volume of their Handbuch (1901) exemplify. Women’s active citizenship was, they suggested, inspired by their gender’s benevolence and was potentially of great benefit to societal progress.

Linking feminism to a philanthropic conception of antislavery also allowed authors to attach to their cause the cachet of illustrious reformers. While before the Civil War, Garrisonians had a reputation for being dangerous firebrands, by the end of the century they had become the celebrated figureheads of the greatest moral victory America had ever seen. The writers of these European women’s rights histories leveraged the now well-established authority of the abolition movement, highlighting how central figures of that cause, such as Garrison and Irish abolitionist Daniel O’Connell, had been supportive of a greater role for women in society. They even claimed figures who had not in fact been on their side, such as Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose accomplishments they proudly recounted (Giraud Reference Giraud1891; Robinson Reference Robinson1898; Schirmacher Reference Schirmacher1898), to indicate burgeoning feminism within the august antislavery movement. These claims worked to improve the reputation of international suffragism, from a radical fringe cause into that ‘still larger, grander vision of the freedom of all human kind’ (Report 1888, 29).

Some accounts went still further, attributing the genuine philanthropic impulse within antislavery to female rather than male leaders and suggesting that female abolitionists understood the cause at a deeper level than their male counterparts. In her work of 1898, Schirmacher insinuated that it had been women who first started organised antislavery (1898, 6). The forging of this connection is especially clear in suggestions that women’s experience of subjection had led to their agitation in the antislavery cause – or the other way around. Martha Strinz, for instance, suggested:

In the discussions of the lawless state of the Negro they heard about those principles on which they later based their own demands. The women, who saw themselves excluded from men’s work because of their sex, turned the teachings of the rights of the individual, with which the liberation of the Negroes was fought, against their opponents. This way, the first organised rise of women to obtain their rights emerged from the lap of the Anti-Slavery Movement.

In 1905, Schirmacher suggested that women’s agitation against slavery came from their own lived experience. Rather than telling the customary story of the political awakening women underwent within abolitionism, she inextricably linked the two movements:

Because women knew from experience, what oppression and slavery taste like, because they, much like the Negro, strove for the recognition of their ‘human rights’, they belonged to the most zealous opponents of slavery, to the most spirited warriors for ‘freedom’ and ‘equality’.

These patterns elaborated on well-established motifs of antislavery. Women’s heightened sensibility had already been a theme of the 1830s novels, as discussed in Chapter 2, as was the exploration of the supposed similarity between women’s experience and that of the enslaved (which went further than a simple assertion of the woman–slave analogy). Now, however, these established strands were woven into avowed authoritative institutional histories, gaining the force of historical causation rather than pathetic appeal.

The myth was also used to justify the concentration of women’s efforts on suffrage. As Rupp discusses, despite the intentions of initiators like Stanton and Anthony, feminist internationalists were at first reluctant to wholeheartedly embrace the divisive demand for the vote. The ICW did not include it in its agenda until prompted to by the split-off of the IWSA – instigated by two German dissidents who balked when ICW leadership proposed to give anti-suffragists a platform at the 1899 congress (Rupp Reference Rupp1997, 20–22). By the 1910s, however, suffragism had become a unifying frame for feminist internationalists of different backgrounds and ideological priorities. The antislavery origin myth supported this move, as a site where the early women’s movement was rewritten as a rights-oriented, political campaign from the onset (see also Tetrault Reference Tetrault2014). In 1898, Schirmacher suggested: ‘[Stanton] had become convinced that all of woman’s civil disabilities stemmed from her political incapacity. Thus, from the beginning, American feminism assumed a political character, was a suffragist movement, to use a convenient neologism’ (Schirmacher Reference Schirmacher1898, 8).Footnote 25 Moreover, retellings of the antislavery origin myth offered an occasion to explore the congruence between women’s and slave emancipation post-Civil War. The myth was narrated in ways that supported the reconceptualisation of suffrage as the ultimate step of emancipation movements generally. Robinson invoked the parallel when she wrote of the dawning of the idea of women’s rights:

This fact [women’s exclusion at the 1840 Convention] and other similar circumstances taught the abolitionists that there was still another class of human beings in America, besides the Negroes, who had rights that a white man has the duty to respect. And it was then that the fight for the enfranchisement of the woman really began.

Giraud was especially explicit on the relationship between the movements, as he emphasised both feminism’s genealogy from, and its parallels with, antislavery:

We said earlier that the movement for women’s suffrage could take its place, in the facts of modern life, alongside the movement for the emancipation of blacks. It’s not just a simple analogy that unites them, but a community of effort, arguments and timing: so that people engaged in one are almost always won over by the other, and could, if need be, make only one set of congresses in which the words of liberty resounded simultaneously, either for the black men [noirs] or for the white ladies [blanches]. The beginning of the movement [in 1840] is topical in this respect […].

Stressing the equiform development and interconnection of the movements was not just salient in the context of American memory politics, where it was part of a tussle over legitimacy. It also allowed European commentators to rely on the history of abolition and civil rights to make the case for a political rights focus in their own contexts. With the American conflict in mind, to internationalist suffragists both the emancipation of the enslaved and that of women were becoming synonymous with suffrage.

The antislavery origin myth also usefully regulated readers’ emotions, promoting the feeling of indignation as rightly constitutive of the women’s movement. Across the histories, indignation was presented as a potent motivational force and narrated in ways that invited readers to partake. Most European accounts emphasised women advocates’ sense of injustice at the Congressional debates over the Fifteenth Amendment and presented it as a motivator for women’s organising in the 1860s and 1870s. The most vitriolic accounts are given by Schirmacher and Zimmern, who tapped into prejudice and fearmongering to highlight the injustice of women’s exclusion and to stimulate readers’ fellow-feeling with particular American actors. The histories created a narrative arc of ‘double betrayal’, casting the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention and the conflict around the Fifteenth Amendment as two decisive events at which women were let down by abolitionists. Strinz used the events of 1869–1870 to excuse the passion of Stanton and her followers to her more moderate German readers: ‘This mood to an extent explains the sharpness of tone and the ferocity of the agitation, which in the following years came to light and which has so discredited the suffrage movement with the majority of women’ (1901, 473).Footnote 28 Other authors leaned into the melodramatic possibilities of this narrative to elicit an affective response from readers. Describing women’s faithful self-restraint during the Civil War, for example, added further pathos to Robinson’s account:

After the slaves, we will take care of the women, said the main orators: wait, help us to abolish slavery and then we will work for you. And women, patriots like the men, remained quiet, busied themselves in hospitals and in the countryside, sacrificed their children and their husbands […]. And they waited. […] The war was over, the black rights were guaranteed, but thanks to the new amendment, the white woman was more than ever kept in the same state of political slavery.

Robinson emphasised the injustice of the ‘political slavery’ of white woman by lingering on the betrayal of her interests after she had faithfully supported the battle for abolition. This arc is also present in Schirmacher’s pamphlet: ‘the white women, who had so bravely worked for the liberation of the Negroes, remained deprived of their political rights’ (1905, 6).

In addition to structuring their account around two betrayals, some accounts dramatised the strategic disagreement within the AERA. Visualising the conflict in terms of white women and black men sharing a space, they invoked a common nineteenth-century melodramatic contrast to arouse indignation (Brooks Reference Brooks1995; Williams Reference Williams2002; Vaughan Reference Vaughan2005; Meer Reference Meer and Williams2018). Robinson’s reference to white women’s political slavery exploited this melodramatic potential and it is most pronounced in Zimmern’s account. In a section titled ‘The Negro’s Hour’, she visualises the ‘insult to the free-born and patriotic women’ that African American male suffrage was portrayed as, by saying the women were bidden to ‘stand aside’:

When the war was over, and the slaves emancipated, the next step was their enfranchisement. Uneducated, ignorant men of an alien race, untrained and unfit to take up such grave responsibilities, were now to help govern the country; while the women who had worked with all their hearts to promote their emancipation, who had borne their full share in the sufferings of the war and the attainment of victory, were to stand aside to make room for the black voter. […] They were bidden to stand aside and not press their claims. ‘This is the negro’s hour’ was the cry on all sides; ‘let us do our duty by him first, perhaps some day he may help you in return.’

Zimmern condensed a protracted debate within the ranks of the AERA into a single dramatic scene. She warped the phrase ‘negro’s hour’, Wendell Phillips’ common short-hand, into a taunting cry from the assembly. The rest of Zimmern’s quotation suggests a cavalier or even snide attitude on the part of the male abolitionists, an inventive addition that further heightened the pathos of the moment. Ominously concluding that women would have to rely on a dubious alliance with black voters in some unspecified future as their only means of enfranchisement, Zimmern represented the women present at this congress as mute, surrounded by menacing, shouting men – a clear break with Stanton’s truculent self-representation.

A little later on in the story, Zimmern reinvoked this potent image in her discussion of Gladstone’s refusal to have women included in the extended suffrage of the 1883 new Reform Bill. This section of the chapter on England was called ‘Women Thrown Overboard’:

Mr. Gladstone made a speech, of which the main point was: ‘The cargo which the vessel carries is, in our opinion, a cargo as large as she can safely carry.’ Under his orders no less than 104 professed friends to the cause broke their pledges, and helped to ‘throw the women overboard’. […] The enfranchisement of the agricultural labourer was the British equivalent to the enfranchisement of the negro. In each case women were told to stand aside and make room for their intellectual inferiors.

This passage restaged and reinforced the affective work of the discussion of the Fifteenth Amendment. Zimmern visualised a historic parliamentary debate at which no women were present, this time painting the scene of upper-class women and uneducated masses packed together on a small deck. Where the women in the first vignette had to endure being shouted down, here they are ‘thrown overboard’, with political measures visualised as violent attacks and women as helpless victims in mortal danger. This textual parallelism strengthened the case that developments in America and England were similar and the passages roused readers’ indignation in a gesture of affiliative fellow-feeling.

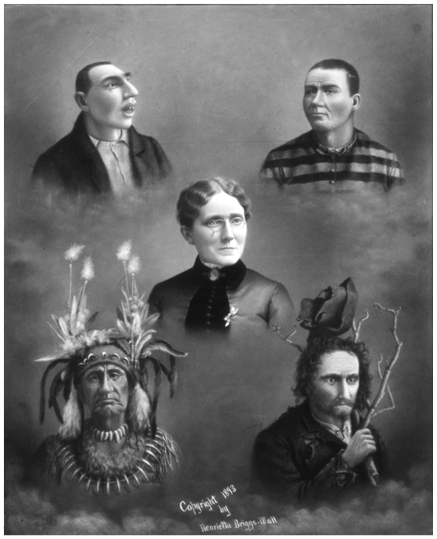

In Zimmern’s account, meek white women are described as in such close proximity to ‘ignorant men of an alien race’ that they had to ‘step aside’ to make space for them. This dramatisation exuded a sense of threat, transforming the optimism of the master narrative of liberal progress into an arena of active struggle and adding a sense of urgency to women’s action. The repeated emphasis on the ‘ignorance’ and ‘alien’ status, and therefore supposedly unpredictable character of non-white or working-class voters, further added to the threat. Robinson’s account made a similar move: ‘[Women] began to wonder why thousands of ignorant, irresponsible men could suddenly become voters, while the women had to remain in the bonds of political servitude’ (1898, 253).Footnote 30 Strikingly, in Moderne Frauenbewegung, Schirmacher invited readers to visualise the opposition between black and white interests by describing a painting she had encountered during her visit to the Chicago Exhibition of 1893:

Heavily and deeply American women felt it, that in the eyes of their lawmakers a member of a lowly race, merely for being a man, was to be placed over the most educated of women. And they expressed their outrage in an image: ‘American Woman and her Political Equals’. There one sees the Indian, the idiot, the lunatic, the criminal – and woman. They all are politically disenfranchised in the United States.Footnote 31

The pastel in question visualised a common refrain about the injustice of women’s continued exclusion from suffrage (Figure 5.2).Footnote 32 In its original form, which circulated both in the Anglo-American world and in Europe, the phrase spoke of ‘criminals, idiots, women, and minors’, but late nineteenth-century preoccupations inspired a racialised update.Footnote 33 Schirmacher incorporated the immediacy of this visual object into her narrative. Asking readers to imagine this image, Schirmacher connected the antislavery origin myth to her wider frame of racial antagonism. By drawing together these cultural materials into a new coherence, Schirmacher communicated a specific logic that went beyond the remit of her research. Independently from her American source materials, Schirmacher invited her German readership’s personal affront not just over the behaviour of abolitionists, but over the American racial order she described and dramatically visualised for her readership.

Figure 5.2 American Woman and Her Political Peers. Commissioned by Henrietta Briggs-Wall in 1892 and exhibited at the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago, 1893.