The case for ground stone tools

Ground stone artifacts are ubiquitous throughout ancient Mesoamerica, yet they are often understudied by archaeologists beyond simple counts, weights, raw material, and form. As Martin Biskowski (Reference Biskowski, Rowan and Ebeling2008:144) lamented,

the category “ground stone” generally lacks cohesion and in practice is often defined negatively as any artifact which is neither ceramic nor obsidian and thus not to be rebagged with those materials. Consequently, ground stone analysis frequently is the analysis of the leftover items which often have little in common with each other.

This general lack of analytical interest may also be related to the commonality of such tools in the houses of many living and recent descendant Maya communities. However, in many ways ground stone tools (GST) in Mesoamerica represent a tangible link between present and past practices (Searcy Reference Searcy2011:1), allowing ethnoarchaeologists to observe first-hand how such tools are acquired and used, and what their broader significances are today, providing strong analogies for interpreting the past.

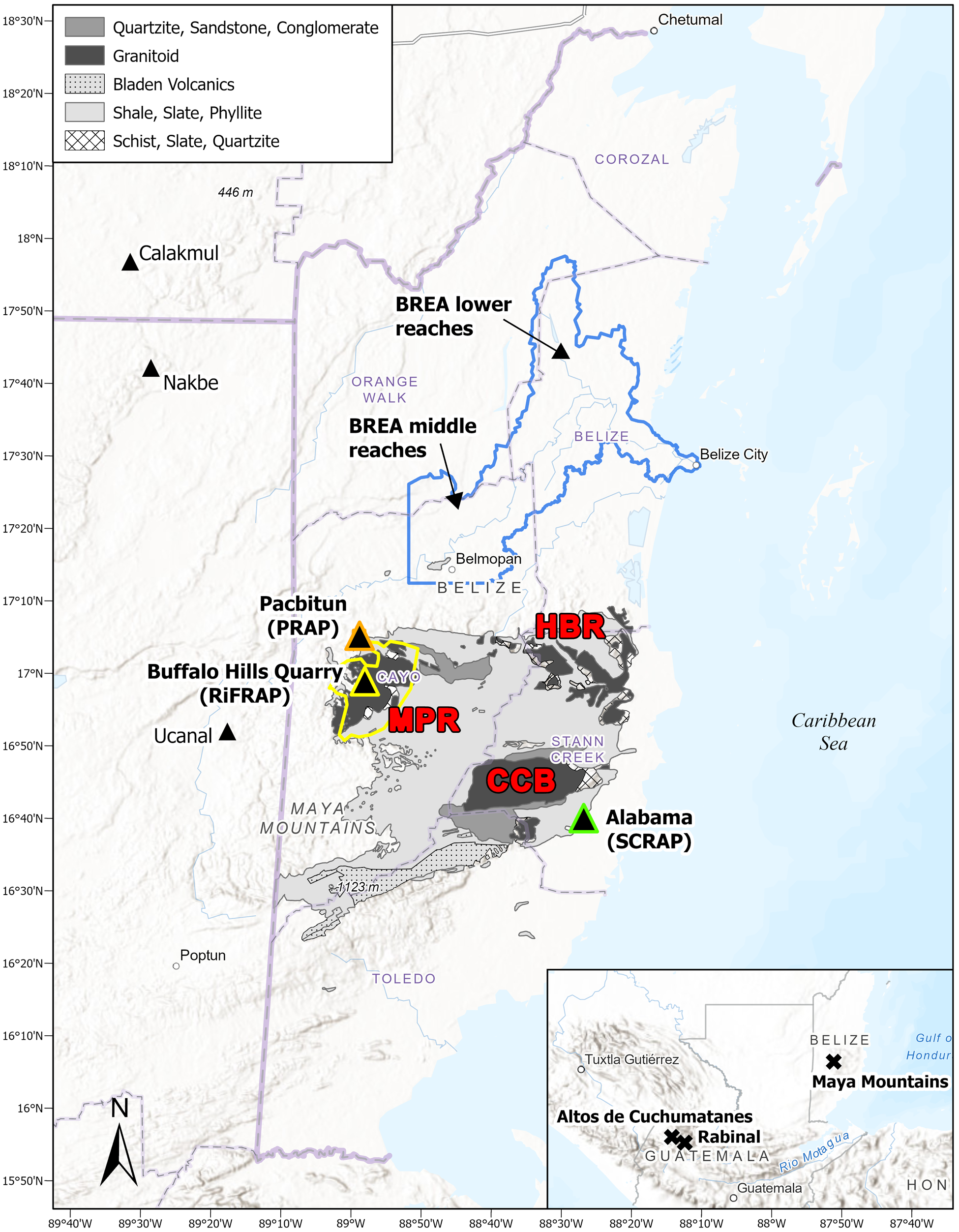

The articles presented in this Compact Section of Ancient Mesoamerica are the result of an organized session led by Jon Spenard during the 87th meetings of the Society for American Archaeology in Portland, Oregon. The original call for proposals asked participants to consider the role of granite GST in ancient Maya society, specifically focusing on how granite was extracted, used, and distributed throughout the landscape of the Eastern Maya Lowlands. The articles presented here approach GST from various points along the life cycle of the tool category, from quarrying of raw granite (Spenard et al., this section) and production of the classic mano and metate set (King and Powis, this section), to the significance of GST distribution, use, and discard patterns for socioeconomic development (Brouwer Burg et al., this section; Peuramaki-Brown et al., this section). They are all related in that handheld, portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) has been used to approximate the provenience of the granite found in the artifact assemblages of these separate projects: the Stann Creek Regional Archaeological Project (SCRAP), the Belize River East Archaeological Project (BREA), the Rio Frio Regional Archaeological Project (RiFRAP), and the Pacbitun Regional Archaeological Project (PRAP; Figure 1). Two summative articles conclude this Compact Section, providing a long-lensed view of GST studies in the Eastern Maya Lowlands (Graham, this section) and the potentialities of studying GST from a broader, hemispheric perspective (Schneider, this section).

Figure 1. Eastern Maya Lowlands showing archaeological projects and sites mentioned in text. CCB = Cockscomb Basin, HBR = Hummingbird Ridge, MPR = Mountain Pine Ridge.

Before getting into the specifics, however, we wish to situate our interest in granite GST, and provide some key definitions. Stone artifacts categorized as “groundstone,” “ground stone,” or “grinding stones” comprise a broad array of objects, all of which have either been worked or modified through the actions of pounding, pecking, grinding, polishing, and abrading (Adams Reference Adams2002:1), and/or are used in such a manner once complete. We recognize the significance in using the technological term “ground stone” rather than the functional term “grinding stone” to describe these specimen. Most of these objects were produced through processes other than grinding, namely pecking, but many of them were used for grinding and pulverizing activities. Nevertheless, since “ground stone” is the term most commonly used in analytical conversations, and following the foundational work of Jenny L. Adams [Reference Adams2002], we retain its use here. We also consider, to a lesser degree, stone that was used to facilitate or accomplish the movements and tasks described above (e.g., a natural stone outcrop used as an anvil or grinding basin; Hayden Reference Hayden1987; Rowan and Ebeling Reference Rowan and Ebeling2008; Spenard et al., this section) or stone that was shaped through these processes and used in building construction (although we recognize that the latter were probably not considered in the same functional category as tools; see Peuramaki-Brown and colleagues, this section).

GST are identified by various characteristics, including raw material type, morphology, surface treatment, and occasionally, the traces of processed residues that remain on their surfaces (e.g., Cristiani and Zupancich Reference Cristiani and Zupancich2021; Dubreuil et al. Reference Dubreuil, Savage, Delgado-Raack, Plisson, Stephenson, de La Torre, Marreiros, Bao and Bicho2015). Unlike chipped stone implements, which require rock that breaks conchoidally (e.g., obsidian, chert, quartz), GST require raw material that crumbles or breaks down around phenocrysts or grain particles during the grinding portion of manufacture (e.g., igneous rock like granite, basalt, and rhyolite, or sedimentary rock like sandstone or limestone; Andrefsky Reference Andrefsky2005:47–59). Production of GST requires both percussive and grinding phases, as Spenard and colleagues discuss in their contribution to this Compact Section. Percussion flaking was employed during the initial stages of reduction after the raw material was extracted, a strategy also documented in northern Mexico (Searcy and Pitezel Reference Searcy and Pitezel2018), and in the U.S. Southwest and California (Schneider Reference Schneider1993a, Reference Schneider1993b, Reference Schneider1996).

The most prevalent GST type from the Mesoamerican archaeological record is the mano-metate set; the metate is a large netherstone upon which substances to be ground are placed and then worked with the hand stone or “mano” (Adams Reference Adams2002:99). Both components are required to accomplish the grinding task (Adams Reference Adams1999:481) and ethnographic research throughout Mesoamerica indicates that manos and metates are often produced as matched sets, meaning a mano is constructed to fit a specific metate, and vice versa (Cook Reference Cook1982:198; Hayden Reference Hayden1987; Searcy Reference Searcy2011). Every household unit would require some form of GST to process milled food products, and perhaps another to grind non-food materials (e.g., lime for washing, pigments for paints; Searcy Reference Searcy2011; Graham, this section). Evidence suggests that in addition to everyday tasks, these tools were also vital to ritual practices (Biskowski Reference Biskowski1997, Reference Biskowski2000, Reference Biskowski, Rowan and Ebeling2008; Clark Reference Clark1988; Cook Reference Cook1982; Hayden Reference Hayden1987; Searcy Reference Searcy2011). Yet, they have regularly been overlooked as subjects of scholarly inquiry, this perhaps being related to their ubiquity in the ethnographic present and archaeological past, and/or to their bulky proportions making them difficult to curate in archaeological labs. While the work of a handful of scholars has attempted to rectify the situation (e.g., Adams Reference Adams2002; de Chantal Reference de Chantal2019; Clark Reference Clark1988; Hansen et al. Reference Hansen, Suyuc, Guenter, Morales-Aguilar, Hernández, Balcárcel, Masson, Freidel, Demarest, Chase and Chase2020; Hayden Reference Hayden1987; Jaime-Riveron Reference Jaime-Riveron2016; Pritchard-Parker and Torres Reference Pritchard-Parker and Torres1998; Rodríguez-Yc Reference Rodríguez-Yc2013, Reference Rodríguez-Yc2018; Rowan and Ebeling Reference Rowan and Ebeling2008; Ruiz Aguilar Reference Aguilar, Laporte, Arroyo and Mejía2005, Reference Aguilar, Elena, Laporte, Arroyo and Mejía2007; Searcy Reference Searcy2011; VanPool and Leonard Reference VanPool and Robert2002)—especially with the application of newer, non-destructive analytical tools like pXRF—there is still much theoretical and methodological development needed to explore the chaîne opératoire of GST within the Eastern Maya Lowlands and beyond.

Below, we describe why we have chosen as a group to focus on granite GST in this Compact Section and set the geological scene for the research discussed herein. Next, we evaluate recent and ongoing work focused on expanding understandings of ground stone extraction, production, exchange, use, and meaning, finishing up with an overview of the research articles contained in this section, and identifying promising areas for future research.

Why granite?

Ancient Maya people made GST from a variety of stone, from the locally available to material that came from far afield (e.g., Brouwer Burg et al. Reference Brouwer Burg, Tibbits and Harrison-Buck2021:Table 1; Graham Reference Graham1987; Halperin et al. Reference Halperin, Lopez, Salas and LeMoine2020). Though studies indicate that raw stone preferences changed over time (e.g. Halperin et al. Reference Halperin, Lopez, Salas and LeMoine2020), an exploration of temporal trends in raw stone usage for GST is beyond the scope of the current Compact Section; however, we stress that this is a research avenue that is yielding important insights, especially with novel, portable instruments like handheld XRF. At sites throughout the Eastern Maya Lowlands, GST made from limestone, quartzite, granite, and basalt are commonly reported (Tibbits Reference Tibbits2016). Across northern Guatemala, limestone and quartzite are the most reported materials used for GST, but at Tikal and Yaxha, granite objects make up approximately 7 percent and 19 percent of the assemblages respectively (Halperin et al. Reference Halperin, Lopez, Salas and LeMoine2020:Table 3). At Ucanal, granite GST make up approximately 35 percent of the Late Classic assemblage (Halperin et al. Reference Halperin, Lopez, Salas and LeMoine2020:Table 2). Though percentages are unreported, granite GST have been recovered from Calakmul (Gunn et al. Reference Gunn, Folan and del Rosario Domínguez Carrasco2020:9–11, 117) and Nakbe, the latter from Middle and Late Preclassic period contexts (Hansen et al. Reference Hansen, Suyuc, Guenter, Morales-Aguilar, Hernández, Balcárcel, Masson, Freidel, Demarest, Chase and Chase2020:329–331).

In northern Belize, local sedimentary rock (e.g., limestone) was commonly used for GST, followed by granite and other non-local materials like basalt. In the Upper Belize Valley, granite originating in the Maya Mountains, mostly from the nearby Mountain Pine Ridge source, was commonly used although tools were also made from locally available limestone, sandstone and non-local basalt (see Brouwer Burg et al. Reference Brouwer Burg, Tibbits and Harrison-Buck2021). Notably, granite from the Mountain Pine Ridge was the most represented non-local material used for GST recovered in the middle Belize Valley, although local stone was also used (see Brouwer Burg et al., this section). In the Sibun Valley and Southern Belize, non-local basalt was commonly used, along with granite and (in the latter case) other local volcanic and volcaniclastic rocks (see e.g., Abramiuk and Meurer Reference Abramiuk and Meurer2006). Unsurprisingly, granite was very commonly used for GST in the Maya Mountains but not to the exclusion of other locally available stone like quartzite and limestone (see Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase2005, Reference Chase and Chase2006, Reference Chase and Chase2008, Reference Chase and Chase2012, Reference Chase and Chase2015, Reference Chase and Diane2016, Reference Chase and Chase2017; Chase et al. Reference Chase, Chase and Chase2019). Even some non-local basalt was brought into the Maya Mountains, despite the local abundance of granite.

Beyond the accessibility of rock, there are various other qualities and characteristics of stone that ethnoarchaeologists and ethnohistorians have determined likely impacted the choice of raw material, which we describe below. For large and heavy tools like GST, however, we cannot help but ask the twin questions of how and why? Mano and metate sets often average between 13.5 and 23 kg (~30 to 50 lb; McBryde Reference McBryde1947:73), so how would they have been produced and, perhaps more importantly, how were they moved around the landscape in a cultural area with no domesticated pack animals? Ethnographic studies of stone workers from highland Guatemala (Nelson Reference Nelson and Hayden1987a, Reference Nelson and Hayden1987b; Searcy Reference Searcy2011) and Mexico (Cook Reference Cook1982) provide some insight into the latter. While contemporary stone workers who make manos and metates (sometimes referred to as metateros) regularly use motor vehicles to transport finished products, loads of up to 45 kg (100 lb—two metates and six manos) were traditionally carried on foot by tumpline (McBryde Reference McBryde1947:73). Reports indicate that some individuals traveled that way to markets over 100 km distant across mountainous terrain (Searcy Reference Searcy2011:69–70). As to why GST were moved such distances, feeding a growing population must have been part of the answer but, as the authors in this Compact Section discuss, broader sociocultural motivators were also likely at play. Otherwise, populations would have used locally available materials rather than importing GST made from distantly sourced raw material.

Setting the geologic scene

In this section, we provide a brief overview of the geology of granite in the Maya Lowlands. We focus on the Maya Mountains as the primary source of granite for the majority of ancient Maya sites in Belize as well as in adjacent areas of Guatemala and Mexico, as noted above. We do not discount the fact that granite from other sources in the Maya highlands might also have been used but, to our knowledge, the relative lack of attention paid to GST in Maya archaeology has left such questions currently unanswerable. One of our primary aims with this Compact Section is to demonstrate the research potential of granite and non-granite GST for Maya archaeology, as well as the analytical potential of portable and non-destructive instruments such as pXRF.

The Maya Mountains, often referred to as the highlands of the Maya Lowlands, represent a region of igneous and metamorphic rocks spread across northern Guatemala and central Belize (Figure 1). It is not the only source of granite occurring in the traditional territory of the ancient Maya—there is also the Rabinal granite source (Ortega-Obregón et al. Reference Ortega-Obregón, Luigi, Keppie, Ortega-Gutiérrez, Solé and Morán-Ical2008) and the Altos Cuchumatanes (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Burkart, Clemons, Bohnenberger and Blount1973; Solari et al. Reference Solari, Ortega-Gutiérrez, Elías-Herrera, Gómez-Tuena and Schaaf2010, Reference Solari, García-Casco, Martens, W. Lee and Ortega-Rivera2013) in the highlands of Guatemala, as well as scattered outcrops in the central cordillera of Honduras (Mills et al. Reference Mills, Hugh, Feray and Swoles1967). Granites have also been reported in the Sierra Madre Mountains in Mexico (Sanchez Montes de Oca Reference Sanchez Montes de Oca1978; Waibel Reference Waibel1946).

Granite in the Maya Mountains is surrounded by a metamorphic areole comprised of early Paleozoic materials (Bateson and Hall Reference Bateson and Hall1977; Dixon Reference Dixon1956). Petrographically, its metamorphic rocks are largely quartzite, slate, and phyllite, with some gneiss (Bateson and Hall Reference Bateson and Hall1977; Dixon Reference Dixon1956; Weber et al. Reference Weber, Scherer, Martens and Mezgerr2012). Outside the Maya Mountains, the Eastern Lowlands’ geology is dominated by Paleozoic sedimentary deposits including limestone and sandstone with locally occurring veins of chert. These sedimentary resources, including chert, limestone, and sandstone, were used extensively for both ground and chipped stone tools.

The degree to which local and non-local materials were utilized over space and time by the ancient Maya is of interest to archaeology; only recently have geochemical techniques like pXRF allowed researchers to conduct provenience studies of stone artifacts without compromising the objects themselves. There are three characteristics of granite that make it an ideal candidate for unlocking questions about production, exchange, use, and meaning: 1) it was a popular rock type used widely by the ancient Maya for GST production; 2) it is geographically restricted in the Eastern Lowlands to the Maya Mountains; and 3) different outcrops within the Maya Mountains have distinct geochemical signatures that can be differentiated by XRF and other provenience analyses (Tibbits Reference Tibbits2016).

Granite forms three distinct plutons within the Maya Mountains: Mountain Pine Ridge, Hummingbird Ridge, and Cockscomb Basin (Dixon Reference Dixon1956; Ower Reference Ower1928). The plutons range in composition from granite to tonalite with quartz porphyries in all plutons and dacitic intrusions reported in Mountain Pine Ridge and Hummingbird Ridge (e.g., Bateson and Hall Reference Bateson and Hall1977; Dixon Reference Dixon1956; Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Duke, Scott, Smith and Wilkinson1995; Ower Reference Ower1928; Shipley Reference Shipley1978; Weber et al. Reference Weber, Scherer, Martens and Mezgerr2012). Here, we describe the petrographic and radiometric differences of the plutons to better situate the following conversations of granite GST production, exchange, use, and meaning.

Cockscomb Basin granite is the least studied of the three plutons, largely related to the difficulty in physically accessing it to obtain samples today. The outcrop lies within a heavily forested, mountainous region of Belize that is protected as part of the Cockscomb Wildlife Sanctuary and Jaguar Preserve. No roads penetrate the wilderness regions. The granite from this source is predominantly light in color and composed of two-micas with plagioclase feldspar and quartz as the dominant minerals (Bateson and Hall Reference Bateson and Hall1977). Potassium feldspar is also present but in lower proportions than plagioclase. Biotite is the dominant mica, though muscovite also occurs in some outcrops (Bateson and Hall Reference Bateson and Hall1977; Dixon Reference Dixon1956).

Hummingbird Ridge granite is more readily accessible via the Hummingbird and Coastal highways of Belize and, consequently, it is relatively well studied. The dominant minerals are plagioclase feldspar and quartz with more potassium feldspar than is reported for the Cockscomb Basin granite. Muscovite mica is more prevalent than biotite mica although ratios of the two vary within the pluton (Bateson and Hall Reference Bateson and Hall1977; Dixon Reference Dixon1956; Tibbits Reference Tibbits2016). Visually discerning Hummingbird Ridge from Cockscomb Basin granite is difficult as both are white to gray with small dark crystals.

Mountain Pine Ridge granite exhibits a wide range of petrographic variation (Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Duke, Scott, Smith and Wilkinson1995). It is most commonly pinkish in color due to high proportions of potassium feldspar. This contrasts with the predominantly white coloration of granites from the Cockscomb Basin and Hummingbird Ridge (though it is worth noting that Cornec Reference Cornec2015 mentions the possibility of pink granite in the Cockscomb Basin). The proportions of micas in the Mountain Pine Ridge are lower than in granites from the other two plutons (Bateson and Hall Reference Bateson and Hall1977; Dixon Reference Dixon1956; Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Duke, Scott, Smith and Wilkinson1995).

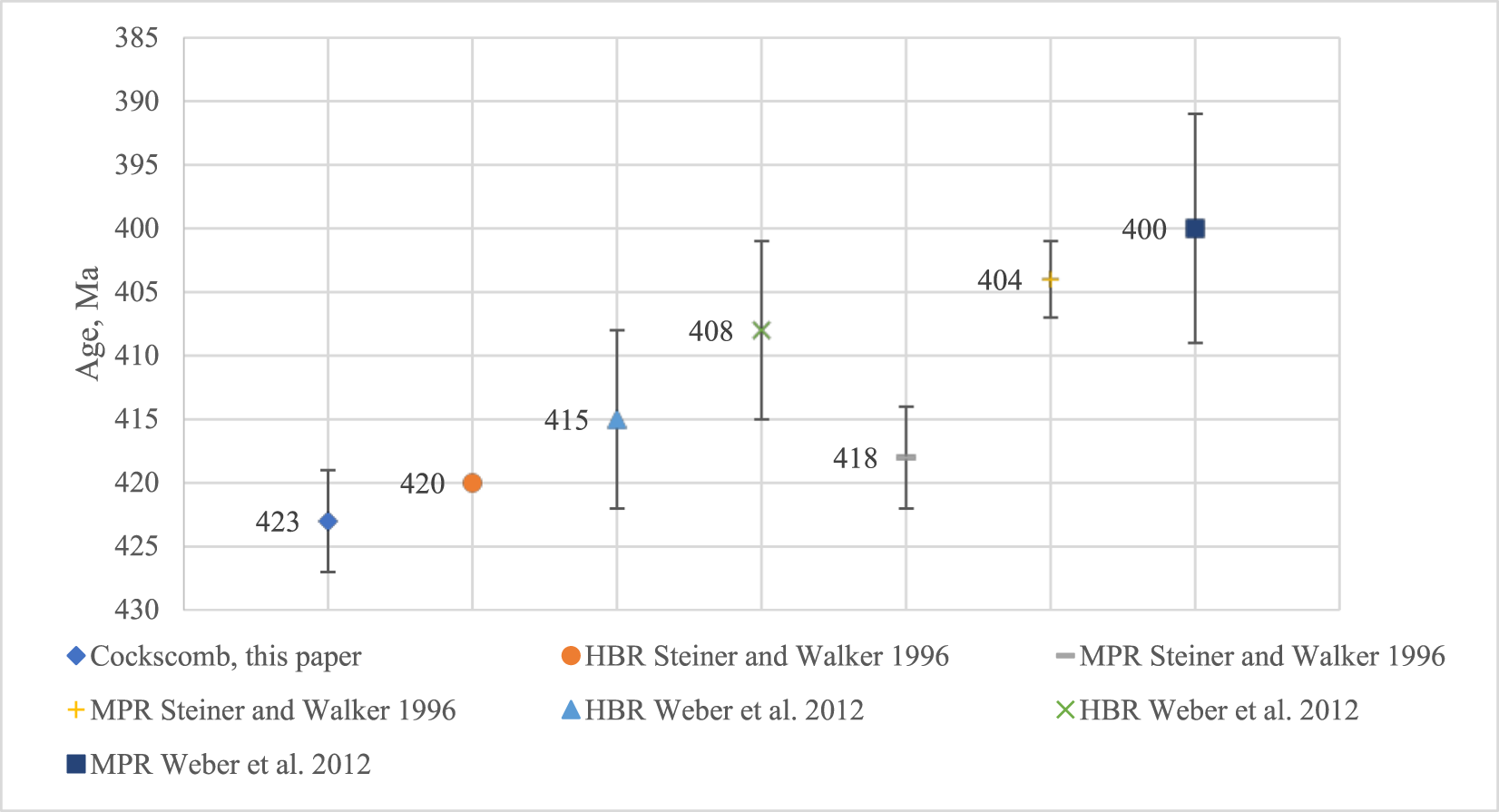

To better understand the chemical differences between the three granite plutons, geologists have attempted to reconstruct the timing and process of their formation. Using U-Pb zircon dating, researchers found that Mountain Pine Ridge granite was most recently formed, with an emplacement age of 400 ± 8 Ma (i.e., the Devonian Period; Martens et al. Reference Martens, Weber and Valencia2010; Steiner and Walker Reference Steiner and Walker1996; Weber et al. Reference Weber, Scherer, Martens and Mezgerr2012); the Hummingbird Ridge granite formed somewhat earlier within the same period, between 408 and 417 Ma (Weber et al. Reference Weber, Scherer, Martens and Mezgerr2012). Tibbits (Reference Tibbits2016) collected granite directly from the Cockscomb Basin and processed hand samples to obtain zircons, which were analyzed for U-Th-Pb isotopes and trace elements using sensitive high-resolution ion microprobe-reverse geometry (SHRIMP-RG) at the Stanford–U.S. Geological Survey Micro-Analysis Center at Stanford University. The results of the analysis yielded a 206Pb/238U weighted mean age of 423 ± 4 Ma for the crystallization of the Cockscomb Basin pluton (Figure 2; Tibbits Reference Tibbits2016). This age is consistent with the established ages of Late Devonian to Early Silurian for the Hummingbird Ridge (408–417 Ma) and the Mountain Pine Ridge plutons (400–418 Ma; Steiner and Walker Reference Steiner and Walker1996; Weber et al. Reference Weber, Scherer, Martens and Mezgerr2012).

Figure 2. Comparison of published ages for the granite plutons in the Maya Mountains. MPR = Mountain Pine Ridge, HBR = Hummingbird Ridge.

The recently obtained date range for the Cockscomb Basin presented here refines the temporal framework of the Maya Mountains and solidifies the age of the Cockscomb Basin granite. We submit that there were at least two major pulses of magmatism that formed the plutonic portions of the Maya Mountains: between 420 and 415 Ma, forming the Cockscomb Basin and Hummingbird Ridge plutons; and again between 408 and 400 Ma, resulting in the Mountain Pine Ridge pluton (see overlap in error bars in Figure 2). Further research into the timing and tempo of the magmatic pulses will have important implications for refining the relationships between the geochemical signatures of the Maya Mountain granite plutons.

We now turn our attention to what can be learned from GST about broader sociocultural processes, with a focus on extraction and production, exchange, use, and meaning. As called for by Wright (Reference Wright, Rowan and Ebeling2008:130), it is imperative that GST as an artifact category be considered more holistically, “in terms of whole systems of organization of such artifacts, from raw material procurement to final abandonment.” If we are to fully understand the importance of GST in past Maya cultures, not only must we give this tool class requisite attention, but we must also refrain from preferencing GST over non-tools (e.g., extraction and production debris, preforms, and failed tools) in order to gain a fuller understanding of the chaînes opératoires (see discussion in Schneider, this section).

Provenience studies

At the core of most GST studies is the basic question: where did these stones come from? The search for meaning within the tools, questions surrounding their movement and exchange, and even discussions concerning mining and production methods cannot be explored fully without first knowing where the parent rock originated (Shott Reference Shott2021). A variety of chemical composition studies have been applied to archaeological assemblages in the last 20+ years, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), lab-based XRF, pXRF, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS), and neutron activation analysis (NAA). Methods for sourcing lithic tools vary by rock type and available equipment. Some rock types are more amenable to specific sourcing techniques given their structure or composition. For example, much research has focused on sourcing obsidian, which makes it an excellent candidate for XRF analysis given its homogenous composition (e.g., Moholy-Nagy et al. Reference Moholy-Nagy, Meierhoff, Golitko and Kestle2013; Nazaroff et al. Reference Nazaroff, Prufer and Drake2010; Simmons et al. Reference Simmons, Stemp, Ferguson and Graham2023; Stroth et al. Reference Stroth, Otto, Daniels and Braswell2019).

Heterogenous rock, such as granite, is more difficult to source using point-and-shoot technologies although robust, lab-tested methods have been developed. Tibbits (Reference Tibbits2016; Tibbits et al. Reference Tibbits, Peuramaki-Brown, Burg, Tibbits and Harrison-Buck2022) developed a method for differentiating between the Maya Mountain granites that requires a minimum of five randomly selected datapoints from a single specimen, which are then averaged to generate a bulk geochemical signature. That process has allowed for XRF sourcing of granite GST with reasonable success at identifying a source pluton. Currently, it is not possible with XRF to differentiate discrete signatures from within plutons.

The benefits and applications of XRF to provenience studies have been well demonstrated for fine-grained (aphanitic) rocks, such as basalt and obsidian (e.g. Biskowski Reference Biskowski1997; Frahm Reference Frahm2012, Reference Frahm and Doonan2013, Reference Frahm2024; Frahm and Doonan Reference Frahm and Doonan2013; Grave et al. Reference Grave, Attenbrow, Sutherland, Pogson and Forster2012; Nazaroff et al. Reference Nazaroff, Prufer and Drake2010; Williams-Thorpe et al. Reference Williams-Thorpe, Potts and Webb1999). The ability to use XRF has also been proven on relatively finer-grained phaneritic and porphyritic rocks, such as dacite (Greenough et al. Reference Greenough, Mallory-Greenough and Baker2004). Provenience studies have the potential to open new avenues of inquiry into GST. With the expansion of field-based XRF and other non-destructive or minimally destructive techniques, questions regarding source location, transportation, economics, and social innerworkings are being explored (e.g., Greenough et al. Reference Greenough, Mallory-Greenough and Baker2004; Palumbo et al. Reference Palumbo, Golitko, Christensen and Tietzer2015; Williams-Thorpe et al. Reference Williams-Thorpe, Webb and Jones2003). We next consider how these analyses are helping to unlock questions about the extraction, production, use, and meaning of GST in the Eastern Maya Lowlands.

Extraction and production

While the quarrying of raw material for GST production has received some attention in other parts of the world (e.g., western North America [Kolvet et al. Reference Kolvet, Deis, Stornetta and Rusco2000; Schneider Reference Schneider1993a, Reference Schneider1996, Reference Schneider, LaPorta, Rowan and Ebeling2008; Schneider and LaPorta Reference Schneider, LaPorta, Rowan and Ebeling2008; Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Lerch and Smith1995]; Southwest Asia/North Africa [Amit et al. Reference Amit, Seligman, Zilberbod, Rowan and Ebeling2008; Harrell and Brown Reference Harrell, Brown, Rowan and Ebeling2008; Peacock Reference Peacock, Peacock and Maxfield1997]), only sporadic research has focused on understanding the extraction of rock for GST production in Mesoamerica (e.g., Cook Reference Cook1973, Reference Cook1982; Rodríguez-Yc Reference Rodríguez-Yc2013; Searcy and Pitezel Reference Searcy and Pitezel2018; Williams and Heizer Reference Williams and Heizer1965). And, while granite GSTs have been found throughout the Eastern Maya Lowlands over the last century of archaeological research, only in the last two years has concrete evidence of ancient Maya quarrying been established in the Mountain Pine Ridge region of the Maya Mountains (see Spenard et al., this section). Furthermore, while the extraction and production of basalt by ethnographically documented Maya groups has been observed (Dary and Esquivel Reference Dary and Esquivel1991; Garcia Chávez et al. Reference Garcia, Ernesto, Montes and Zuñiga2002; Hayden Reference Hayden1987; Searcy Reference Searcy2011; Searcy and Pitezel Reference Searcy and Pitezel2018), only one in-depth study of granite extraction and production has been undertaken in contemporary Mesoamerica (Cook Reference Cook1982) and thus the bulk of our inferences are based upon data gathered from extraction of the former rather than the latter.

A general sequence of production is followed by most ethnographically observed stone workers in Mesoamerica. Large stone boulders are pried or blasted out of the subsurface. Next, blocks are removed from the boulder and taken to a secondary roughing-out area. Initial shaping is conducted at the extraction site and roughed-out forms are typically ferried back to workshop spaces adjacent to homes, located 1–10 km distant (Hayden Reference Hayden1987:21–22; Searcy Reference Searcy2011:34–36; note: a similar spatial relationship has been observed by King and Powis, this section).

The second phase of the process—shaping and finishing—is conducted in home workshops. The GST is finished through fine pecking and abrasion of the surface, a process that produces large quantities of micro-debitage (Nelson Reference Nelson and Hayden1987a). Searcy (Reference Searcy2011) and others (Cook Reference Cook1982; Hayden Reference Hayden1987) emphasize that a variety of tools are used in each step, from long batons and sledges, to varying sizes of metal picks.

As with the technical organization of many quarrying activities, extraction is typically undertaken by a set of individuals who may be patrilineal kin (Cook Reference Cook1982:159; Searcy Reference Searcy2011:64) or part of a craft guild (Hirth Reference Hirth2008:444; Marcus Reference Marcus, Canuto and Yaeger2012). The skills necessary for quarrying and GST production appear to be bundled and passed primarily through apprenticeships, with younger novices learning by watching and experiential practice. Searcy (Reference Searcy2011:50) notes that younger stone workers make the easier mano forms as they learn the intricacies of producing the more difficult metate forms.

Other important topics to consider in the extraction and production of GST involve the selection and perceived quality of the stone used. Both Hayden (Reference Hayden1987) and Searcy (Reference Searcy2011:54–56) found that three key characteristics were sought by stone workers as well as the consumers of ground stone: 1) density of vesicles (holes in the stone created by gas bubbles during emplacement); 2) color (although these are not preferences for literal colors but rather associations of quality with color); and 3) presence of flaws or weaknesses in the stone.

Exchange

We could consider GST similarly to the way Drennan (Reference Drennan1984a) approaches ceramics—they are also heavy, unwieldy, and sometimes breakable, rendering them less than ideal for transport over long distances. However, the geographically restricted nature of granite in Mesoamerica, and analytical techniques permitting researchers to connect geochemical fingerprints between sources and artifacts, is facilitating investigation of a broader range of questions surrounding the exchange of GST.

Granite is a heavy rock; mano-metate (Reference Ishihara2007)sets made from the material can weigh on average about 23 kg (or 50 lb). McBryde (Reference McBryde1947:73) estimated that a standard load for an individual is about 45 kg (100 lb), consisting of two metates and six manos. In his work on transport costs, Drennan (Reference Drennan1984b:105) assumes a standard bearer load of 30 kg; he argues that water transport by canoe, raft, or dory presented a more energy efficient mode of transport. The use of canoes by living and recent Maya groups has been observed as a widespread phenomenon, and Drennan (Reference Drennan1984b:106) works from the premise that a four-paddle dugout canoe could easily manage a one-ton load. Schneider and colleagues carried out a replication experiment for water transport of stone tools and found that 113–181 kg of stone cargo and human paddlers could move 1.6 km per hour in a small (3 m long) tule raft in 50 cm of water (Schneider and LaPorta Reference Schneider, LaPorta, Rowan and Ebeling2008:31).

As Brouwer Burg and colleagues (this section) discuss, there are various models of exchange that were likely at work simultaneously in the ancient Maya world. Their inferences are based in part on observations made of living Maya groups. Mano-metate sets are most often purchased at local markets by consumers following a generalized market-based exchange model (Cook Reference Cook1982; McBryde Reference McBryde1947:81–83; Searcy Reference Searcy2011:66–71). Occasionally, middlemen will purchase metates wholesale from mano-metate makers and then resell them to retailers or in their own stalls at markets (Cook Reference Cook1982:253–254; Searcy Reference Searcy2011:69). Moreover, mano-metate sets will often be gifted directly to newlyweds or as a housewarming gift, a type of gift exchange. Unlike consumable commodities, GST cannot be further subdivided and thus do not make good candidates for traditional down-the-line exchange models. However, GST seem to be key components of intergenerational exchange systems, especially among women. Searcy (Reference Searcy2011:72) notes that 53 percent of the metates he studied were passed down among generations, with 88 percent of those sets being given to daughters. Additionally, GST are often repurposed for a variety of different practical tasks, from those similar to the originally intended use of grinding, to serving as hammerstones, structural fill, and even table supports (for discussion of GST life histories, use, and recycling, see Basgall Reference Basgall, Rowan and Ebeling2008; Fullagar et al. Reference Fullagar, Field, Kealhofer, Rowan and Ebeling2008; Hayden Reference Hayden1987:191; Kadowaki Reference Kadowaki, Rowan and Ebeling2008; Searcy Reference Searcy2011:98–100; Wright Reference Wright, Rowan and Ebeling2008).

Use and meaning

The tool category of ground stone is typically associated with utilitarian and domestic uses; however, ethnographic studies, iconographic depictions, and ethnoarchaeological research focused on understanding the life histories of GST indicate that these objects were used in a much broader array of activities. Relatedly, while the mano-metate set may appear to supply inferential information about female-gendered tasks in the home, new analysis techniques and theoretical developments are challenging researchers to think more deeply and widely about the significances of these tools. We outline these research initiatives below.

The ethnographic evidence from Mesoamerica is helpful in providing correlates for how ancient GST might have been used, and archaeological material studies focused on extracting microbotanical residues from GST, such as phytoliths and starch grains, have bolstered this data (Cagnato Reference Cagnato2018; Piperno and Holst Reference Piperno and Holst1998). The mano-metate set is undoubtedly one of the most important tools in the home used to produce a) masa flour, the dietary foundation in this part of the world; b) other foods like coffee, cacao, chili, garlic, etc. (Searcy Reference Searcy2011:76); and c) other substances including pigments, spices, and salt (Hayden Reference Hayden1987:188). And, even with today’s modern conveniences such as gas-powered metal mills available in many towns, it is remarkable how many Maya women still report using their mano-metate sets daily: among the Q’eqchi’, more than 90 percent of women report using their sets multiple times a day (Searcy Reference Searcy2011:Figure 4.6). Over 50 percent of the Poqomam Maya report using their sets multiple times a day, and over 30 percent report using them at least once a day, for a total of 80 percent in daily usage. The K’iche’ Maya use their mano-metate sets less frequently with about 45 percent reporting rare usage, 25 percent weekly, 25 percent daily, and about 5 percent multiple times a day. Nevertheless, the K’iche’ Maya keep old GST around in case of electrical outages (not uncommon), or to give automated-mill-ground flour a quick final grind (Searcy Reference Searcy2011:76).

Similar to the way in which adolescent males learn how to extract and form GST, adolescent Maya girls may also learn to become efficient metate users by watching and coaching from their mothers (see Isaac Reference Isaac and Isaac1986:16). While observing experienced Hopi women making efficient use of their GST, Adams (Reference Adams2002:68) noted a kind of embodied knowledge in which the body (rather than the mind) led the process. As with other types of embodied knowledge, this information cannot be learned through verbal description alone; the physical practice of achieving the desired result must be experienced and honed by the doer (see “knowledge in the hands” described by Merleau-Ponty 2013 [Reference Merleau-Ponty and Landes1962]; also Tanaka Reference Tanaka, Stenner, Cromby, Motzkau, Yen and Haosheng2011). We assume that ancient Maya women learned to use mano-metate sets in this way. While there is no direct evidence yet to support this assumption from the archaeological record, a scene on page 60 of the Codex Mendoza shows an Aztec mother instructing her daughter in the appropriate body movements and placements for efficient grinding (Searcy Reference Searcy2011:84–85, Figure 4.7). Other important knowledge that was likely passed down between GST users involved the quality of the stone used and methods for resurfacing a metate to improve grinding efficiency (usually achieved through pecking to increase roughness).

The choice of stone to use in the production of a GST is culturally coded. While raw material choice is something that modern-day analyzers might distill down to physical attributes like surface texture, hardness, fracturing properties, and accessibility, Carter (Reference Carter, Rowan and Ebeling2008:67) reminds us that “ancient choices may have been structured by quite different notions of appropriateness, involving the stone’s more esoteric and non-mechanical qualities, such as color, smell, specific place of origin and its associated metaphysical properties” (see also McKenzie 1983) or “the procurer’s rights of access, based on group affiliation, age, and/or gender” (Carter Reference Carter, Rowan and Ebeling2008:67; cf. Hampton 1999:227–228; Torrence Reference Torrence1986:52–57). All of these characteristics are bound up in the social significance of ground stone.

Probing beyond the quotidian uses of the mano-metate set in Mesoamerica, ethnographers have demonstrated the many varied meanings of GST. For example, the sets embody a gender complementarity that runs throughout much of living Maya social life: while men are responsible for the extraction, production, and often exchange of mano-metate sets, “once they have been used by a woman, a man should not touch them out of respect for the stone and the woman” (Searcy Reference Searcy2011:93). To reify the boundaries of appropriate gendered tool use—reflecting the gendered division of labor—there are culturally constructed taboos or awas associated with men who encounter mano-metate sets after their use-life begins. The resulting curse ensures the man will only produce offspring of the opposite gender, which provides significant insight into the value of women in society. It is important to highlight that these gender divisions are further codified in the Popol Vuh, in which the female creator deity, Xmucane, ground the corn that would be mixed with water to form the first four male deities on a metate (Tedlock Reference Tedlock1996:43–44). The above research indicates that GST sets may have been seen in some instances as object-persons with the agency to interact with humans in certain ways.

The idea that stone was alive and had agency is common in Mesoamerican thought. Maya iconography is rife with images of living rocks of all sizes, from mountains to portable objects (Stuart Reference Stuart, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010:288). Mountains and hills, the epitome of rocky things, were considered living entities (Stuart Reference Stuart1997:14) whose cave-mouths exhaled cloudy, rain-filled breath (Brady and Ashmore Reference Brady, Ashmore, Ashmore and Knapp1999; Taube Reference Taube, Fields and Zamudio-Taylor2001). Maya rulers are regularly depicted standing on sprouting, breathing zoomorphic mountains, commonly referred to as the “Kawac Monster” (Taylor Reference Taylor, Robertson and Jeffers1978) or “Witz Monster” (Stone and Zender Reference Stone and Zender2011:139, 169) on stelae, public monuments, and even the facades of structures (Andrews Reference Andrews1995; Fash Reference Fash1991:123; Gendrop Reference Gendrop and Wood1998; Taube Reference Taube2004:79–86, Reference Taube, Luján, Carrasco and Cué2006:154–158, Reference Taube, Hays-Gilpin and Schaafsma2010). The being has been referred to as the “essence of stone” (Schele et al. Reference Schele, Miller and Kerr1986:45–46), but it is used in reference to the cave-filled mountains and hills that make up most of the Maya region, which in the lowlands is primarily limestone.

Manos and metates are commonly reported from ritual cave sites throughout the Maya region (Bassie-Sweet Reference Bassie-Sweet1996; Brady Reference Brady1989; Halperin and Spenard Reference Halperin, Spenard and Bassie-Sweet2015; Ishihara Reference Ishihara2007; MacLeod and Puleston Reference MacLeod and Dennis1978; Morton Reference Morton2015; Moyes Reference Moyes, Brady and Prufer2005, Reference Moyes2006; Pendergast Reference Pendergast1969; Peterson Reference Peterson2006; Prufer Reference Prufer2002; Slater Reference Slater2014; Spenard Reference Spenard2006, Reference Spenard2014; Woodfill Reference Woodfill2007). A unique occurrence of GST in an underground setting comes from the cavern beneath the site of Balankanche, Yucatan. There, archaeologists recorded over 250 miniature mano-metate sets and censers, the latter decorated with the face of Tlaloc, the central Mexican rain deity (Andrews Reference Andrews1970). Unfortunately, little overall theorizing has been done to understand the presence of GST in underground sites, except to suggest they were used for agricultural rituals, to prepare ritual food, or related to rain making. Additionally, GST recovered in cave contexts are often fragmented, which may be related to the releasing or returning of the item’s spirit to the ground, effectively ending its life cycle.

Were granite GST, especially manos and metates, imbued with life essence similar to the other rocks and minerals? Two instances of the objects depicted on vessels were identified in the online Kerr Maya Vase Database. In both cases, the tools are footed and in active use; one is gray and the other covered in black and white speckles, suggesting the items were made from basalt and granite respectively as commonly reported in archaeological literature. Stuart (Reference Stuart2014) has recently proposed a reading of KA’ for the “bent kawak” glyph, meaning metate or grinding stone. As the colloquial name for the glyph suggests, it contains the cluster of grapes motif, a possible reference to the items being made from limestone. One of the examples presented has a zoomorphic component, a head on top of the grinding surface in the position where an accompanying mano (stylized as a human hand) rests in the other examples. Clearly, much more research into the symbolic nature of GST is required.

Organization of this compact section and future avenues for research

This Compact Section’s overall aim is to highlight some of the recent and ongoing work underway on ground stone, yet many questions remain for those interested in probing the significances of ancient Maya granite GST. These can be clustered around the themed areas we describe above. Much remains to be done to further elucidate where raw material for GST were quarried, by whom, and how. Specifically, new field research in granite-rich areas is revealing the first concrete evidence for extraction and production of these manos and metates in the Eastern Maya Lowlands. Spenard et al. (this section) describe dozens of extraction loci that were found surrounded by quarry tailings, extensive reduction debitage, discarded products, and tools for extraction and reduction at the recently identified Buffalo Hills Quarries site. To understand the scope of granite GST production within domestic workshop contexts, King and Powis (this section; see also Skaggs et al. Reference Skaggs, Micheletti, Lawrence, Cartagena, Terry, Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti2020; Ward Reference Ward2013) detail new data from the ancient Maya site of Pacbitun, where there was a community-wide focus on granite tool production. These two articles provide tantalizing glimpses into what could be a well-developed ground stone industry. Trajectories for future research entail problematizing elements of the production process through broader spatial surveys, and persistent questions revolve around understanding how quarrying and production work was organized in both socioeconomic and spatiotemporal levels.

While these contributions shed new light on the scale at which quarrying and production was organized in the Mountain Pine Ridge area, there is currently a dearth of information on the who, when, where, and why of granite resource management among the Hummingbird Ridge and Cockscomb Basin outcrops. The research that stands out is that currently led by Peuramaki-Brown and colleagues (this section) at the site of Alabama, where granite appears to have served as one of the staple resources that facilitated the relatively sudden rise of the town toward the end of the Late Classic (see also Peuramaki-Brown and Morton Reference Peuramaki-Brown and Morton2019). Employing a holistic view of granite use, these authors underscore the need for further research into the multiscale behavioral processes and meanings involved in resource management, which is much more than just an economic endeavor. Furthermore, their work—as a counterpoint to work in the Mountain Pine Ridge—has generated many new questions about different approaches to extraction, production, and exchange that were carried out by ancient Maya groups in the Cockscomb Basin outcrop.

The beauty (and curse) of using XRF is that it provides a neat connection between a granite source and the place where a granite GST was found. For inferential development, however, this tidy connection has proven thorny. In their contribution, Brouwer Burg and colleagues (this section) start with the provenience data (that is, granite found in the middle and lower reaches of the Belize River Watershed has been found to derive primarily from the Mountain Pine Ridge source), and then attempt to puzzle out the various mechanisms by which that granite moved and what that movement signifies. In their heuristic modeling of these questions, they pose a series of questions to cast against the material correlates of the archaeological record, questions that should occupy future researchers for years to come, including how the granite was moved and what that movement could signify about larger sociopolitical relationships and culturally held beliefs.

The last two articles in this Compact Section are intended to provide both a retrospective on ground stone studies in the Eastern Maya Lowlands and a broader comparison of the latter to the trajectories of ground stone studies in other parts of the Americas. Graham is no stranger to the geologic resources of Belize, having published in the late 1980s several articles on resource diversity and stone availability (e.g., Graham Reference Graham1987; Shipley and Graham Reference Graham1987). In this Compact Section, she ponders other uses granite may have satisfied, focusing on granite minerals for paints and slips. Her contribution encourages all scholars interested in this artifact category to expand thinking beyond use to the meanings behind GST more generally. In the final article, Schneider provides a history of the application of the chaîne opératoire to ground stone tool production as she considers the broader contexts in which ground stone functioned in past societies. She couches a commentary to the articles in this section within a consideration of our modern-day conceptualizations of sites, specifically the site-type “ground stone quarry.”

In addition to the two summative works included here, the four research contributions in this Compact Section represent, to our knowledge, the first time that different research projects studying the ancient Maya—some proximate and others further afield—have come together around the subject of granite ground stone in order to answer the many questions we have independently converged upon. In this manner, we are working collaboratively to understand the full life cycle, both materially and spatiotemporally, of the ancient Maya granite ground stone economy, which our collective research suggests was a more complex and widespread system than previously thought. We acknowledge that the articles contained herein are restricted spatially in their focus on Belize. It was not our intent to exclude researchers working outside of Belize on similar questions; rather, the spatial scope of these articles simply highlights where such research is primarily being carried out. We also wish to recognize that additional recent work is being conducted on ground stone outside of Belize in neighboring parts of Guatemala (e.g., de Chantal Reference de Chantal2019; Halperin Reference Halperin2021; Halperin et al. Reference Halperin, Lopez, Salas and LeMoine2020) and Mexico (see Jaime-Riveron Reference Jaime-Riveron2016; Rodríguez-Yc Reference Rodríguez-Yc2013, Reference Rodríguez-Yc2018).

Ground stone studies are not often pursued for many reasons, including the sheer volume of artifacts, the size and weight of the tools that make curation and storage difficult, the wide range of raw materials, and the difficulty of sourcing some rock types. Additionally, ground stone studies rarely warrant the attention of M.A. or Ph.D. level research. By our calculations, only 10 theses have focused concertedly on GST in the Maya region in the last 20 years, six master’s-level investigations (de Chantal Reference de Chantal2019; Delu Reference Delu2007; Duffy Reference Duffy2011; Tibbits Reference Tibbits2012; Turuk Reference Turuk2007; Ward Reference Ward2013) and five Ph.D. theses (i.e., Abramiuk Reference Abramiuk2005; Duffy Reference Duffy2021; Jaime-Riveron Reference Jaime-Riveron2016; Rodríguez-Yc Reference Rodríguez-Yc2013; Tibbits Reference Tibbits2016). This scenario underscores just how little research attention has been focused on this prevalent artifact category by junior researchers, to say nothing of the scant attention from senior scholars. We hope that the studies described herein will help to invigorate renewed research interest on GST assemblages throughout the Eastern Maya Lowlands. Ground stone technology has remained “one of the last bastions of ‘common sense’ interpretation in archaeology” (Carter Reference Carter, Rowan and Ebeling2008:67) for too long. It is time that GST, and specifically granite GST, have their turn in the scientific spotlight.

Data availability statement

No primary data is reported in this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.