1.1 Don’t Believe Everything You Read!

As you began reading the words on this page, your brain embarked on a complex journey to encode, retrieve, predict, interpret, and maybe even reinterpret their meaning, arriving at an understanding within hundreds of milliseconds. We routinely carry out these mental gymnastics whenever we engage in reading, speaking, and listening to language. The ease and apparent effortlessness with which we produce and understand our native language is a testament to the intricate workings of the human brain. However, it is important to acknowledge that this ability is not without its faults. Errors, blunders, and misunderstandings can occur at any step in this complex process. While some of these errors are immediately noticeable, like an embarrassing slip of the tongue, others are more subtle and can easily go unnoticed. One type of error that has recently received much attention in the field of psycholinguistics involves so-called linguistic illusions, which will be the broad focus of this book.

“Linguistic illusions” is an umbrella term used in psycholinguistics to describe instances in which listeners or readers systematically misunderstand, misinterpret, or fail to notice anomalies in the input despite their linguistic competencies. As we will see in the upcoming chapters, some illusions are characterized by the inability to form a coherent interpretation of what seems to be an otherwise perfectly normal sentence, as in the case of comparative illusions that arise in sentences like More people have been to Russia than I have (the sentence is syntactically well formed and reads just fine, but the comparison is incoherent). Sometimes we fail to notice that a sentence is missing a verb, as in the case of the missing VP illusion, which arises in already cognitively taxing sentences that contain multiple levels of embedding, like The artist who the dealer who the buyer called appreciated the publicity (the subject of the most deeply embedded clause lacks a verb, but this sentence is typically rated as more acceptable than its complete counterpart that has all three verbs).

Importantly, the linguistic illusions discussed in this book are not only common in everyday speech but also readily replicated in laboratory settings, making them a suitable phenomenon for rigorous examination through the conventional methods in psycholinguistics. It is this systematicity that distinguishes illusions from the other random or idiosyncratic errors that occur when we are tired, distracted, or have our mouths full. They are rooted in the fundamental procedures for producing and understanding language. As we will see in the upcoming chapters, thorough investigation of such effects can reveal the mental structures and processes of the human language system.

There are many phenomena that qualify as linguistic illusions, which we will survey in the next chapter. Among these, one particular illusion has garnered significant attention and will be the primary focus of this book as our case study: agreement attraction. Broadly, attraction refers to instances wherein during the course of forming a linguistic dependency between nonadjacent words/phrases in language use (either in production or comprehension), another word/phrase that is not the grammatically specified controller of the dependency misdirects processing. This leads to the formation of a grammatically illicit dependency (i.e., a dependency that violates the constraints of the grammar), which can disrupt processing and degrade the acceptability of well-formed grammatical sentences (an illusion of unacceptability) and facilitate processing and boost the acceptability of ungrammatical ill-formed sentences (an illusion of acceptability). Agreement attraction specifically arises when processing agreement dependencies, such as subject–verb number agreement – a dependency that requires the subject and verb in a sentence to match in number, with singular subjects taking singular verbs and plural subjects taking plural verbs.

To illustrate, compare the sentences in (1). The sentence in (1a) is grammatical, but (1b) is ungrammatical because the verb were does not match its subject noun key in number. (Throughout this book, I will use an asterisk * to indicate ungrammaticality, as is standard in the field of linguistics.)

a. The key to the cabinet was rusty.

b. *The key to the cabinet were rusty.

Native speakers of English reliably judge sentences like (1b) as unacceptable relative to (1a) and experience disrupted processing upon encountering the verb during moment-by-moment reading or listening. But something surprising happens when we make a seemingly innocuous edit to (1b), such as change the noun cabinet from singular to plural, as in (2). This noun cabinet(s) is grammatically irrelevant for the purpose of subject–verb agreement, and the sentence in (2) is ungrammatical for the same reason that the sentence in (1b) is ungrammatical (i.e., the subject noun and verb mismatch in number). But, interestingly, this small change from cabinet to cabinets makes a big difference in how we process the sentence. In particular, this change often makes speakers blind to the agreement error: The presence of the plural noun in (2) boosts the acceptability of the sentence relative to (1b) and reduces the processing disruption associated with the agreement error at the verb (e.g., Pearlmutter et al., Reference Pearlmutter, Garnsey and Bock1999; Wagers et al., Reference Wagers, Lau and Phillips2009). This effect constitutes an illusion of acceptability (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Wagers, Lau and Runner2011) because the plural noun cabinets (dubbed the attractor) creates a temporary false impression that the ungrammatical sentence is acceptable. In the parlance of standard psychology and signal detection theory, we might say that the attractor is a lure or distractor that triggers a false alarm (i.e., the incorrect judgment that the required item, such as a plural subject, is present when it is in fact absent).

(2) *The key to the cabinets were rusty.

It is tempting to dismiss this finding as just another case where we are not paying close attention to the stuffy grammatical rules of language that we were taught to obey back in grade school, especially since we can still understand what the sentence means. You might also be tempted to write this off as some dialectal quirk or a case of variable or incorrectly described grammar. Or maybe it is something idiosyncratic of subject–verb number agreement that does not represent the language as a whole or impact other aspects of language processing.

As we will see, agreement illusions are not like other random mistakes that we make when we are distracted or not paying close attention. They are found in nearly every language that has been tested so far, withstand dialectal variation, and arise in a variety of syntactic configurations (e.g., not just when the plural noun is closer to the verb than the target subject noun). Furthermore, the effect is much more pervasive than we initially thought, generalizing to an ever-growing list of linguistic dependencies. For instance, for each dependency in (3)–(6), speakers show robust sensitivity to the error in the (b) example but often fail to notice the same error in the (c) example (the sentences in (a) are the grammatical counterparts for reference), giving rise to an illusion of acceptability (e.g., Drenhaus et al., Reference Drenhaus, Saddy, Frisch, Kepser and Reis2005; Jäger et al., Reference Jäger, Mertzen, Van Dyke and Vasishth2020; Laurinavichyute & von der Malsburg, Reference Laurinavichyute and von der Malsburg2022; Martin, Reference Martin2018; Parker, Reference Parker2022; Parker & Phillips, Reference Parker and Phillips2017; Vasishth et al., Reference Vasishth, Brussow, Lewis and Drenhaus2008). The dependencies represented in (3)–(6) differ from each other linguistically in important ways. But in each case, the presence of an attractor (relativized to the specific requirements of the respective dependency) tricks us into thinking that the sentence is well formed.

a. The bodybuilder who worked with the trainer injured himself.

b. *The bodybuilder who worked with the trainer injured themselves.

c. *The bodybuilder who worked with the trainers injured themselves.

(4) Negative polarity items (NPIs)

a. No bill that the Democratic senators voted for ever became law.

b. *The bill that the Democratic senators voted for ever became law.

c. *The bill that no Democratic senators voted for ever became law.

(5) Verb phrase (VP) ellipsis

a. Jane recruited for the event that the villagers organized, and John did too.

b. *Jane recruited for the event that the villagers organized, and John was too.

c. *Jane recruited for the event that was organized by the villagers, and John was too.

(6) Subject–verb thematic binding

a. The knife with the handle cuts.

b. *The drawer with the handle cuts.

c. *The drawer with the knife cuts.

As we will see in the upcoming chapters, the attraction effects observed for the dependencies represented in (2)–(6) are similar in direction and magnitude, but they differ in subtle yet significant ways. In particular, we find a pattern of selective fallibility, where seemingly minor changes to the sentence, such as altering morphosyntactic features or the position of the attractor, target, or tail of the dependency, can reduce the magnitude of the effect or even eliminate it altogether. For instance, changing the voice of the ellipsis clause in (5c) from passive to active or swapping in sentential negation for the negative quantifier in the NPI constructions in (4c) can effectively eliminate the respective attraction effects (e.g., Orth et al., Reference Orth, Yoshida and Sloggett2021; Parker, Reference Parker2022). Understanding the scope and variability of these effects is crucial for identifying their underlying cause.

Over the past few decades, the source and scope of attraction effects has become a central debate in psycholinguistics. Is there a homogeneous cause for these effects across dependencies? What are the conditions that do/do not give rise to attraction effects? Can we selectively switch the effects on and off for all dependencies, or is malleability specific to certain dependencies? What does the variability tell us about the underlying cause of these effects? We have some guesses, but we have yet to get to the bottom of the puzzle. We will consider these questions and more in this book.

1.2 Illusions in the Cognitive Sciences

Within the broader cognitive sciences, the systematic investigation of linguistic illusions is a relatively recent endeavor, following the path pioneered by their more famous older sibling, the optical illusion. Both optical and linguistic illusions are defined by a discrepancy between our perception and the actual input, be it visual or linguistic. From a phenomenological perspective, both types of illusions force us to grapple with the fact that our trust in the accuracy of what we see or hear as a true reflection of the external world is often misplaced. They reveal just how easily our perceptions can be deceived. From a methodological perspective, the investigation of optical illusions has been invaluable in deepening our understanding of the visual system’s workings. Similarly, the systematic study of linguistic illusions is crucial for unraveling the intricacies of language processing, including its representations, processes, and mechanisms, as suggested by Phillips et al. (Reference Phillips, Wagers, Lau and Runner2011). This is a central theme in this book.

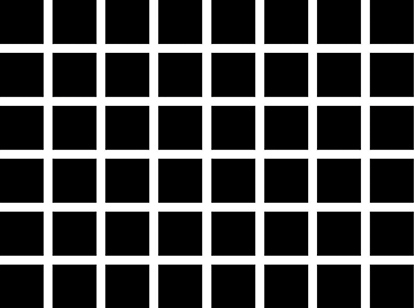

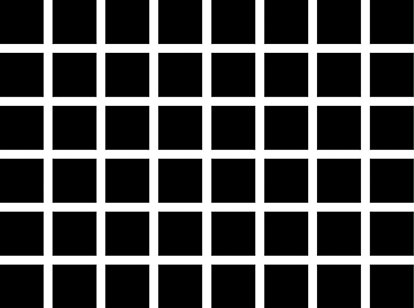

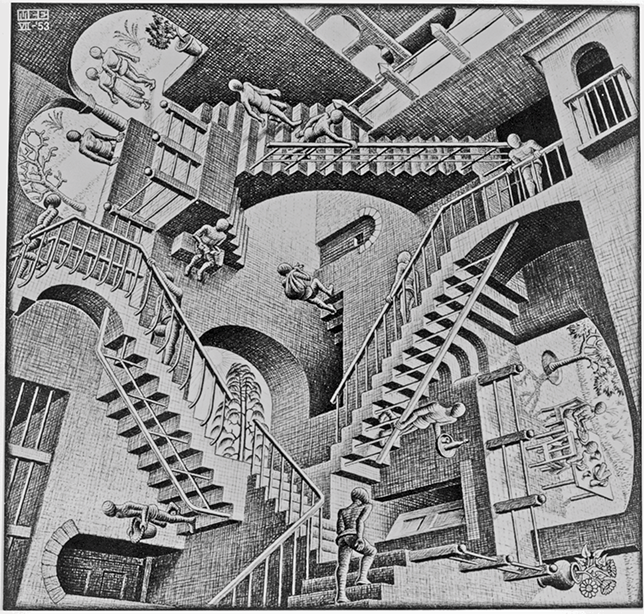

However, it is important to acknowledge that there are fundamental differences between optical and linguistic illusions that limit the extent of their comparison. For example, chief among them is the finding that optical illusions are typically persistent. Even when you know that a visual percept is illusory, you cannot shake the illusory experience. Consider the so-called Hermann grid illusion that arises from the image in Figure 1.1. This illusion, discovered by Ludimar Hermann in 1870, is characterized by gray phantom dots that appear to flicker around at the intersections of the grid, which remains static on the page (Hermann, Reference Hermann1870). Even when you know the image is static, you still experience the perception.

Figure 1.1 The Hermann grid illusion.

By contrast, attraction effects are probabilistic in nature. They do not occur all the time. In the lab, we see their effects only in a portion of trials. There also seems to be an important timing distinction. Whereas optical illusions reflect competing or conflicting visual percepts that arise simultaneously, attraction effects reflect conflicting linguistic percepts at different points in time. Specifically, attraction effects arise in moment-by-moment processing or when participants have to provide a quick judgment while they might still be working out the meaning of the sentence. But attraction effects are substantially weakened or eliminated when participants have ample time to give a more considered judgment. Broadly, attraction is a fleeting perception of acceptability or coherence that mismatches the judgments that form the basis of our grammatical generalizations in formal linguistics.

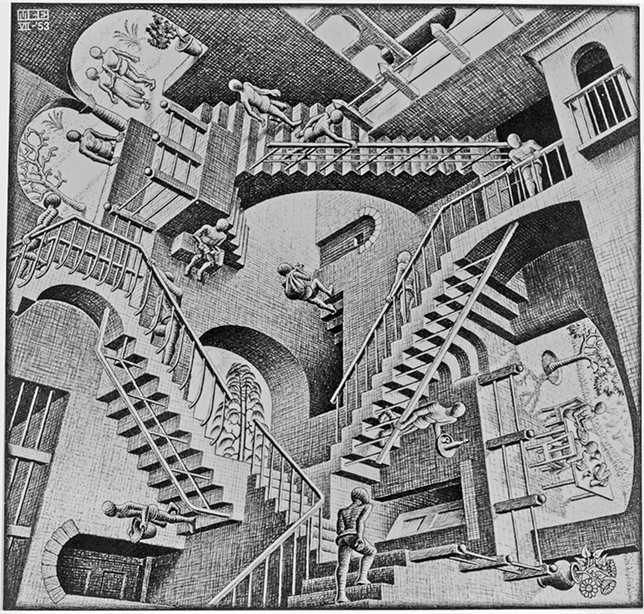

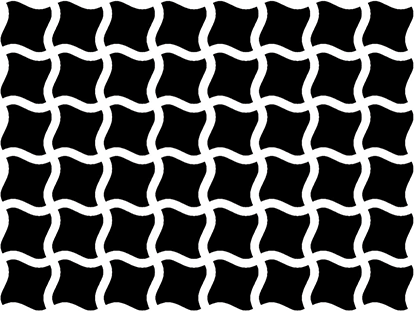

As such, linguistic illusions can be likened to an M.C. Escher drawing, such as the 1953 print Relativity (Figure 1.2). At first glance, the structure depicted in the print appears normal, but closer inspection reveals a surreal blend of competing gravitational sources within a single space, offering different impressions over time depending on where we focus our attention.

Figure 1.2 M.C. Escher’s Relativity.

Despite these differences, the approach to studying illusions is the same across perceptual and cognitive domains. Once an illusion is discovered (often serendipitously), cognitive scientists typically approach the problem by systematically making small changes to the input (whether visual or linguistic) to determine what factors give rise to the illusion. The findings then serve to develop and constrain theories about how the underlying generative system works.

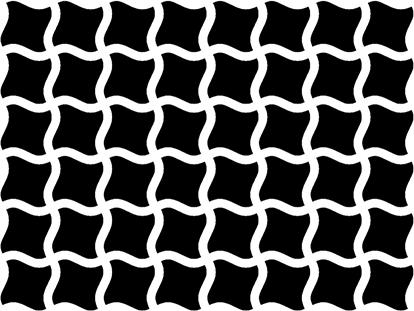

Consider again the Hermann grid illusion in Figure 1.1. Initially, it was thought that the illusory dots were a response of the ON–OFF or OFF–ON receptive fields in the retinal ganglion cells, a theory proposed by Günter Baumgartner in 1960 (Baumgartner, Reference Baumgartner1960). However, nearly fifty years later, János Geier and colleagues showed that a simple distortion to the grid lines, as demonstrated in Figure 1.3, could completely eliminate the illusory dots (Geier et al., Reference Geier, Bernáth, Hudák and Séra2008).

Figure 1.3 The illusory dots observed in the classical Hermann grid disappear when the grid lines are curved.

The finding that we can systematically control susceptibility to the illusion with such a small change was surprising because it is not predicted by Baumgartner’s theory in Figure 1.3. All of the preconditions for the illusion according to Baumgartner’s theory are in place, yet the illusion does not arise. Baumgartner’s original proposal was important because it generated decades of productive research on the visual processing system. However, discoveries such as the one made by Geier and colleagues are equally informative because they constrain the theory in a specific way. In the case of the Hermann grid illusion, the unexpected disappearance of the illusion as a result of a small modification ruled out a prominent theory of how the brain processes visual information.

Research on linguistic illusions follows a similar path. We try to figure out clever ways to make linguistic illusions come and go in a systematic fashion because this process of incremental inquiry provides valuable clues about how and why such effects arise in the first place. Recently, this approach has been accelerated as the result of increasingly detailed explicit computational models of language processing that are used to generate precise quantitative predictions about linguistic behavior and explore the space of hypotheses in a systematic fashion (e.g., Yadav et al., Reference Yadav, Smith, Reich and Vasishth2023). Just as in the vision sciences, the discovery of a small change that can modulate susceptibility to a linguistic illusion is productive because it narrows down the range of possible causes.

1.3 What Is at Stake?

Over the past decade, there has been a surge of interest in linguistic illusions, particularly in attraction effects, from numerous research teams worldwide. The boom in this field partly stems from the fact that linguistic illusions are invaluable tools for addressing key questions in psycholinguistics. These questions concern how we mentally encode, manipulate, access, and interpret linguistic representations. Linguistic illusions also have the potential to inform long-standing debates about the cognitive architecture of language and the role of the grammar in moment-to-moment processing.

The standard view in (psycho)linguistics dating back to the 1960s and 1970s is that the grammar processor and the language processor (the “parser”) are separate cognitive systems, each with a distinct purpose and distinct set of mechanisms and representations (e.g., Bever, Reference Bever and Hayes1970; Townsend & Bever, Reference Townsend and Bever2001). On this view, the parser relies on superficial templates, strategies, or pseudo-grammatical rules to assemble a “good-enough” interpretation in the service of rapid communication (e.g., Ferreira, Reference Ferreira2003; Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Bailey and Ferraro2002; Karimi & Ferreira, Reference Karimi and Ferreira2016). The resulting mental representation of the input may be inaccurate in some ways, but it suffices for communicative needs. Only when an error or misunderstanding becomes apparent does the grammar intervene to provide a more detailed, albeit time-consuming, analysis to fill in the details that the parser initially missed. Attraction effects reinforce this dual-systems view because they reveal a mismatch between the sentence representations that are built during moment-by-moment (“real-time”) processing and those licensed by the grammar.

A closer inspection of linguistic illusions suggests a different account. A growing body of research indicates that attraction effects likely result from the way we encode and access sentence structures in memory, rather than from a uniformly superficial, good-enough parser. On this view, attraction does not reflect a misalignment between the grammar and parser but rather the limitations of domain-general memory encoding and retrieval mechanisms used to implement language-specific computations such as linguistic dependency formation (e.g., Lewis & Phillips, Reference Lewis and Phillips2015; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Wagers, Lau and Runner2011).

From this perspective, researchers have narrowed down the cause of attraction effects to two possible sources. One class of accounts posits that attraction effects arise in the encoding of words and phrases in working memory during sentence comprehension. On this view, the cognitive mechanisms used to encode linguistic structure in working memory during comprehension can erroneously bind grammatical features derived from the input (e.g., plural number) to the wrong item in memory (e.g., the head of the subject noun phrase). It has been hypothesized that in the case of subject–verb agreement attraction, misbinding could occur due to movement (“percolation”) of the offending feature through the syntactic representation encoded in memory (e.g., Franck et al., Reference Franck, Vigliocco and Nicol2002; Vigliocco et al., Reference Vigliocco, Butterworth and Semenza1995; Vigliocco & Nicol, Reference Vigliocco and Nicol1998) or spreading activation (e.g., Eberhard et al., Reference Eberhard, Cutting and Bock2005; Hammerly et al., Reference Hammerly, Staub and Dillon2019), resulting in an equivocal representation of number marking that can mislead agreement computation at the verb. Throughout, I will refer to this class of accounts as the representational-based account, as it attributes the problem to how linguistic representations are encoded in memory.

The other class of accounts locates the source of attraction effects to the retrieval of information from memory for agreement computation. On this view, the encoding of the sentence is generally assumed to be intact and faithful to the input (e.g., features are bound to the right items in memory, modulo repair or reanalysis), but the retrieval processes that are engaged to link the verb to its subject to process agreement can occasionally recover the wrong item if it matches some of the search criteria (e.g., plural number), misleading agreement computation (Wagers et al., Reference Wagers, Lau and Phillips2009). Throughout, I will refer to this class of accounts as the retrieval-based account, as it attributes the problem to the retrieval mechanisms used for dependency formation.

These two accounts make divergent predictions about where we should and should not see attraction, which has sparked a race between research teams to generate the key data points that would settle the debate about which account is “right.” As with any behavioral science, the data are seldom as definitive as our theories would prefer, leaving the issue unresolved. But what both approaches agree on is the value of attraction effects as a tool for investigating how domain-specific grammatical processes, like dependency formation, are implemented using domain-general cognitive mechanisms, such as working memory.

Ultimately, research on attraction effects, and linguistic illusions more broadly, addresses two key questions in psycholinguistics:

Cognitive architecture – what is the relationship between the grammar and parser?

Processing mechanisms – what cognitive mechanisms are used to encode, access, and manipulate linguistic representations during sentence comprehension?

Over the past decade, significant advancements have been made in our understanding of attraction effects and linguistic illusions due to the use of diverse behavioral measures, cross-linguistic investigations, insights from the cognitive neuroscience of memory, and the development of explicit computational models that allow us to explore the space of hypotheses and generate increasingly precise quantitative predictions that can be tested in the lab (Felser et al., Reference Felser, Phillips and Wagers2017). Researchers have even started using linguistic illusions as benchmarks for testing the capabilities of AI systems and large-scale language models (e.g., Lee & Vu, Reference Lee, Vu, Al-Onaizan, Bansal and Chen2024; Linzen & Leonard, Reference Linzen and Leonard2018; Zhang, Gibson, & Davis, Reference Zhang, Gibson, Davis, Jiang, Reitter and Deng2023).

Research on linguistic illusions represents a truly integrative approach to the study of language. It unites theoretical, experimental, and computational approaches, and targets core questions about the cognitive architecture and processing mechanisms. However, despite the attention it has garnered, many significant questions about the source and scope of linguistic illusions remain unanswered. Furthermore, the rapidly expanding volume of publications on linguistic illusions can overwhelm both newcomers and experienced researchers trying to navigate often conflicting findings. While some review articles exist, they are growing dated and are often limited in scope due to the short article format.

With these challenges in mind, this book aims to (i) take stock of what we know and do not know about linguistic illusions, with a focus on agreement attraction; (ii) evaluate and synthesize hypotheses about the source and scope of such effects; and (iii) offer some suggestions for future research.

1.4 Overview of the Book

This book is divided into three parts. The first part of the book provides a brief introduction to the range of phenomena that can be classified as linguistic illusions. Starting in Chapter 2, I provide a broad characterization of linguistic illusions as cases where our perceptions of the linguistic input mismatch reality, in alignment with how optical illusions are characterized in the vision sciences. Phenomena from various levels of linguistic representation are discussed, ranging from phonetic to semantic illusions. The focus then narrows to illusions at the sentence level, classified according to their end effect on comprehension: (i) systematic misinterpretations, (ii) illusory semantic (in)coherence, and (iii) illusions of grammaticality. Each classification includes an up-to-date summary of empirical findings and leading proposals related to the cognitive architecture and processing mechanisms. This review establishes the argument that although many illusory phenomena appear similar on the surface, there is not a homogeneous cause for linguistic illusions, thus precluding a single explanatory account.

The second part of the book narrows the focus of the book to attraction effects. Chapter 3 motivates this shift on both theoretical and methodological grounds. Agreement is a widespread phenomenon across languages and has been extensively investigated in both formal and experimental linguistics. Research in formal linguistics has produced a detailed description of the structural and morphological constraints on agreement, laying a solid foundation for experimental investigation into the cognitive processes that implement agreement computations in real time. A central question in psycholinguistics then is how grammatical constraints, such as the morphological and syntax constraints on subject–verb number agreement, guide moment-by-moment sentence processing. Methodologically, standard experimental measures and paradigms are highlighted for addressing two specific questions about the role of grammar in sentence processing: (i) the timing of agreement constraint application during real-time comprehension and (ii) the accuracy of constraint application. Agreement attraction represents a failure of real-time constraint application and uncovering the cause of these effects is necessary to develop a comprehensive theory of how the grammar is used in real-time sentence comprehension.

I then provide a concise review of the experimental paradigms used to investigate attraction and the resulting behavioral indices (observed profiles in judgments, reading times, etc.), focusing on three key empirical findings reported in the literature:

(i) The grammatical asymmetry: Attraction effects are observed in ungrammatical sentences but generally not in grammatical sentences.

(ii) The markedness asymmetry: Attraction effects occur when the subject noun is in its unmarked singular form (e.g., the key to the cabinets …) but not when it is in its marked plural form (e.g., the keys to the cabinet …).

(iii) The timing asymmetry: Attraction effects are observed in time-sensitive measures but are generally much weaker in untimed measures.

Chapter 3 concludes with a discussion of empirical advancements in research on attraction. I walk readers through the evolution of research on attraction effects. They were initially assumed to be a rather narrow phenomenon limited to subject–verb agreement, but it has since been discovered that attraction is a widespread phenomenon that generalizes to a wide range of grammatical features (e.g., gender, person, animacy), linguistic dependencies (e.g., reflexives, ellipsis), and languages (e.g., Spanish, Russian, Greek, Arabic).

Chapter 4 provides a comprehensive review of the leading accounts of attraction. I first present the class of representational-based accounts, including feature percolation and the spreading activation model. I then present the class of retrieval-based accounts. For each class of accounts, I summarize the key claims regarding the proposed mechanisms, representational assumptions, and linking assumptions.

In Chapter 5, I evaluate the predictions of the leading accounts of attraction against four key sets of empirical findings. Specifically, I evaluate their predictions for (i) the markedness asymmetry, (ii) the grammatical asymmetry, (iii) the timing asymmetry, and (iv) attraction beyond subject–verb number agreement dependencies. I then conclude with a discussion of additional evidence for consideration. Ultimately, the comparison of competing accounts points to the retrieval-based account as offering the broadest empirical coverage. In the remaining chapters, I discuss outstanding challenges that further differentiate the leading accounts.

In Chapter 6, I address a challenge to the retrieval account specifically tied to its unique prediction of a grammatical asymmetry. Recently, it has been claimed that the empirical evidence for a grammatical asymmetry is not as reliable as widely assumed (Hammerly et al., Reference Hammerly, Staub and Dillon2019). To address this concern, I provide a survey of ninety-five experiments published in the literature, demonstrating that the grammatical asymmetry is, in fact, reliable across dependencies, languages, measures, and sample sizes, consistent with the predictions of the retrieval account. I also address an alternative explanation proposed by Hammerly et al. (Reference Hammerly, Staub and Dillon2019), which suggests that the asymmetry reflects a response bias effect within a representational-based framework. Using computational modeling, I demonstrate that this effect can also arise within a retrieval-based framework under a different set of linking assumptions, and therefore, it does not provide compelling evidence against the retrieval account.

Chapter 7 addresses an empirical challenge for both the representational and retrieval accounts: pronouns. Both accounts predict that object pronouns in sentences like *The woman thought that the man defended him should be susceptible to attraction from the grammatically irrelevant noun that matches the pronoun in gender (man) during comprehension. However, previous studies have failed to find such evidence. Through two experiments, I demonstrate that when potential confounds in earlier studies are controlled for, pronouns are indeed susceptible to attraction. Moreover, the specific profile observed across these studies aligns uniquely with the predictions of the retrieval account.

Lastly, in the third part of the book, I summarize the findings, arguing that the data considered throughout the book favor a retrieval-based account. I also highlight gaps in our understanding of attraction, propose directions for future research centered on six “known unknowns,” and offer concluding remarks.