Introduction

While environmental challenges are high on the public agenda, they have raised many questions concerning the ability of society and politics to cope with them. Much of the attention goes either to government action or to the various forms of people’s reaction, namely protest on the streets and at the voting ballots. Especially liberal democracies, claiming to bridge people’s will and institutional politics, get distressed by the massive challenges of the environmental crisis. The respective routines and institutions of democratic governance, as well as their methods of intermediating between institutional politics and the people, are being subjected to scrutiny. There is a search for more ‘interactive’ forms and proceedings that can mitigate conflict and dissent and facilitate the creation of legitimate and efficient environmental politics. This calls for a relational approach (Evers & von Essen, Reference Evers and von Essen2019 & Reference Evers, von Essen, Evers and von Essen2024), that takes up the roles of civic engagement and civil society actors as part of a wider complex interplay between state (political and administrative institutions), civil society, and economy.

Against this background, our ‘Local Climate Governance’ project has investigated new forms of policy making and administration that have emerged in the area of local climate policy during recent years (2022/2023). Our examination focused on seven larger towns in Baden-Württemberg. Both, the stimulus provided by the debate on democracy, governance, and the place of civil society therein, and the study of concrete local practices led to the central questions of our project: to what extent are new forms of action, of measures and regulations—altered forms of ‘governance’—developing in towns and municipalities?

Given the central role of cities in implementing climate protection measures, the past two to three decades have seen significant research interest in this area (Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Hickmann and Kern2018). Castán Broto and Westman (Reference CastánBroto and Westman2020) identify two principal research trajectories that emerged in the 2010s with regard to climate governance in urban contexts: urban optimism and urban pragmatism. Urban optimism views cities as alternative governance arenas in the light of the failures of international climate regimes. In contrast, urban pragmatism perceives climate governance within cities as part of the broader ‘sub-national’ framework, thereby integrating it into the international climate regime (Castán Broto & Westman, Reference CastánBroto and Westman2020). The pragmatism trajectory is further characterised by a focus on trans-local action (Benz et al., Reference Benz, Kemmerzell, Knodt and Tews2015; Corcaci & Kemmerzell, Reference Corcaci and Kemmerzell2023; Kemmerzell & Tews, Reference Kemmerzell and Tews2014) and the concept of upscaling (Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Hickmann and Kern2018; Kern, Reference Kern2019 & Reference Kern, Rayner, Szulecki, Jordan and Oberthür2023, Corcaci & Kemmerzell, Reference Corcaci and Kemmerzell2023). In the European context, this refers to the embedding of local climate policy within the multi-level governance system (Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Hickmann and Kern2018).

Both urban optimism and urban pragmatism have primarily addressed questions concerning the reasons behind and methods of cities' climate actions. This includes asking how cities can be governed within the framework of international climate regimes, and which forms of injustice, discrimination, or inequality might be addressed by climate protection measures. However, a research gap persists in capturing the everyday realities and experiences of climate protection. This includes understanding the interactions between various measures, policies, and actors within the city (Castán Broto & Westman, Reference CastánBroto and Westman2020; Wang & Ran, Reference Wang and Ran2023).

In order to address this research gap, it is useful to draw on the concept of governance, which will be discussed in greater detail in the following chapter (2). After a short sketch of the methodology of the study (chapter 3), we present (in chapter 4) key developments in local administration and urban society. On this basis, we focus (in chapter 5) on an attempt to classify the central forms of interaction and cooperation that we found—traditional ones revitalised and new ones emerging. In the final sum up (in chapter 6), we will come back to a question raised but not explicitly addressed by our overview and stocktaking: To what degree does a more interactive governance, as we have observed it, also mean a more democratic governance?

Interactive Governance—Cornerstones of an Analytical Concept

Interactivity: The Common Basic Idea of Various Concepts for a ‘new Governance’

When one speaks of governance instead of government, one emphasises the processes of governing, including the various ways actors from the social sphere participate.

The observation and analysis of alterations in governance by increasing ways and new forms of participation—especially but not only—in liberal democratic systems and their political administrations, takes place in the theoretical literature under varying headings. The mention of ‘new governance’ as ‘modern governance’ (Kooiman, Reference Kooiman1993) referred quite generally to altered relationships between state governance and the addressees in society. A central concept was that of cross-sectoral ‘policy networks’ (Marin & Mayntz, Reference Marin and Mayntz1991). In the subsequent international discussion, four terms have become established: ‘collaborative’ governance (Ansell & Gash, Reference Ansell and Gash2007; Hofstadt et al., Reference Hofstad, Sorensen, Torfing and Vedeld2022), ‘intersectoral’ governance (McQueen et al., Reference McQueen, Wismar, Lin, Jones and Davies2013; Gonser & Schmid, Reference Gonser and Schmid2023), ‘interactive’ governance (Torfing et al., Reference Torfing, Peters, Pierre and Sorensen2019), and ‘intermediation’ (Evers & von Essen, Reference Evers, von Essen, Evers and von Essen2024). Despite all the differences in detail, there remains a great affinity between these concepts. The common fundamental idea can be formulated as follows: They understand governance as a question of development and dealing with different forms of mutual influence and coordination between participants from the state sector, civil society, and the economy—their involvement in the preparation of concepts, in decision-making, and in the process of their implementation.

When the term ‘interactive governance’ is preferred in the following, this does not mean to adopt one special string in the governance debate. It is rather chosen because this term expresses particularly well a central challenge for governance in the liberal democracies of today: to find and re-form institutionalised forms of ‘interplay’ and intermediation between the side of political representatives and administrators on the one hand and the spheres of society on the other hand. These forms reach from the various initiatives, organisations, and movements of a civil society over to the advocates of the business sector.

Interactive Governance in a Democracy

The idea of interactive governance is closely linked to questions of appreciating, using, and revitalising the opportunities which can be provided by a liberal democratic order. The question is: how can traditional representative and new participative forms of politics and governance be combined? To what extent are the new ones likely to influence or even displace the old ones? Will combinations of traditional and new elements enable more democracy, possibilities for dealing with the future, and securing citizens' rights?

What is now demanded in the concepts for intersectoral/interactive/collaborative governance is the upgrading of elements that are mostly given lesser importance in the ‘classical’ forms of liberal representative democracy. These elements can be briefly summarised in four points:

• The stronger involvement of participants and interests that are particularly affected in the respective area of a political intervention. The term stakeholder is very often utilised for this.

• Opportunities for citizens to participate in various sectors of services (health, education, and culture) as kind of co-producers (Brandsen et al., Reference Brandsen, Steen and Verschure2018) in their design and functioning—individually and through their own organisations. Ideally, this can take place even before the implementation phase by citizens as co-initiators (Stougaard, Reference Stougaard2021).

• The joint search for situation-specific variants and concepts, which could thereby deviate from sameness in the sense of centrally decreed uniformity without, however, calling into question equal basic rights. There is a close relationship here with the concept of ‘multi-level governance’, which not only functions hierarchically, but also as a reference framework for interactions between local innovations and central impulses (e.g. through social innovations and model programmes) (Evers & Ewert, Reference Evers, Ewert, Loeffler and Bovaird2021).

• While the accent in the debate on interactive governance is on the intersectoral, it is equally important to strive for more interaction within the administrative sector itself. The concern with this task is often debated in terms of challenging the strict separation of different public administrations as ‘silos’ (Scott & Gong, Reference Scott and Gong2021). This leads to coordination problems due to the individual perspectives and priorities of each organisational unit, which do not share this information (Bogumil & Jann, Reference Bogumil and Jann2020; Hustedt & Radtke, Reference Hustedt, Radtke, Sager, Mavrot and Keiser2024). This is particularly evident when a new field of action such as climate politics emerges, challenging already existing goals and routines across policy areas and departments.

• A shift towards a more co-operative style of action requires reorientation and restructuring steps on all sides (Tuurnas et al., Reference Tuurnas, Paananen and Tynkkynen2023)—stakeholders and administrators, citizens and politicians. Political organisations and bodies (local councils and elected officials) as well as administrations need to open up statehood further to stakeholders from civil society and business. Likewise, civil society organisations cannot just simply regard themselves as a ‘counter-power’ limiting itself to organising ‘pressure’ from ‘below’ or from ‘outside’. Within the framework of interactive governance, they have to develop themselves as well as co-responsible participants.

These new approaches often grow alongside traditional forms of governance, ‘in the shadow of hierarchy’ (Mayntz, Reference Mayntz, Benz and Dose2010). However, questions increasingly arise about their connection and blending with traditional forms of governance in liberal democracies. Cities provide a good context for exploring this.

Interactive Governance in Local Climate Policy: Limits of our Stock Taking

Overall, our study is limited to noting different forms and forums of interactive governance in the field of local climate policy with their specificities and references. It does not represent an assessment of the entire fields and processes of an ecological turn that can be found on local levels. The respective limitations of our study may be summed up in three points.

First, by dealing with local climate governance networks, we catch just a part of a wider field of interactions. There is a considerable difference between what is covered by networks of local climate governance and the broad field of environmentalist actions and initiatives in urban society, as, for example, regarding issues of biodiversity, health, and lifestyle. While many of them are not aiming at active participation in governance decisions, they nevertheless still shape some of the socio-cultural fields in which local climate governance must seek some kind of baseline.

Secondly, by focussing on a discussion of policies, we have not fully grasped the wider dimensions of climate challenges for politics. It must be taken into account, that issues relating to climate and environment, with their high public importance and fundamental nature, cannot be viewed solely as a question of a specific field and the administrative body ‘responsible’ for it. Mistrust of the administration as a direct partner can refer to generalised mistrust of ‘those people up there’, to fundamental questions of respect and justice, which go beyond concerns with the quality of a specific policy. Hence, much of the governance-talk has difficulties to grasp basic and general motives on the side of the social counterparts who they want to address (see Evers & von Essen, Reference Evers, von Essen, Evers and von Essen2024).

Finally, with the overall few interviews and the wide field covered, we have only been able to visualise the contours of new forms, platforms, and contours of governance. Our primary aim was to explore emerging trends and new interactive forms of governance, rather than to analyse differences between the seven towns studied. An analytical assessment of stability, mid-term results, and impact as well of differences between the towns will require further work.

Methodology of the Study and Report

The focus of the study is placed on the local level. For this purpose, we selected seven large towns, located in the Federal State of Baden-Württemberg: Freiburg, Heidelberg, Heilbronn, Karlsruhe, Stuttgart, Tübingen, and Ulm. The selection of these medium-sized towns, with a population of between one and six hundred thousand, was mainly based on evidence of particularly advanced local climate policies, such as media reports, participation in national and European model programmes, awards, and high positions in relevant rankings.

We were interested in making visible the basic commonalities of the profile of governance taking shape there. It was not our intention to debate differences between these towns and potential reasons for these in their respective socio-economic profiles.

However, this selection can only be considered representative if it is assumed that these selected towns are signalling a climate policy awakening that is just beginning to emerge in other towns and cities, both large and small.

Our findings are based on two research methods—document analysis and interviews with experts. The document analysis primarily served to obtain an initial insight into the field, but also helped us to prepare the interviews and to ask specific questions about individual participants, events, and measures. Key documents included the seven climate protection plans, which were analysed with a focus on areas where measures are to be implemented. Depending on the town, additional documents such as urban and transport development concepts, energy reports, and heat planning concepts were also reviewed. The homepage of the municipal environmental or climate office was examined for special awards, campaigns, projects, and programmes. Any relevant references, including cooperation partners and initiatives, were followed up on and compiled into a collection of links and documents.

Furthermore, 16 qualitative expert interviews were conducted. We conducted interviews in each of the seven cities with both a public administration official and a representative of a local civil society organisation. In the administration, we spoke to the climate protection manager or, if unavailable, the person responsible for climate protection within the environmental agency. For civil society, we reached out to local groups of Fridays for Future, major German environmental associations, and smaller local groups identified through our initial search. Ultimately, we realised an interview with a civil society representative in each town, with two requests fulfilled in one city, reflecting a true variety of different kinds of organisation. Additionally, we interviewed an employee of a large local research company to gain deeper insights into specific aspects of local implementation.

As we are addressing people in a professional role, we have designed the interviews as expert interviews, which calls for a well-structured guideline that we have developed accordingly (Helfferich, Reference Helfferich2011). This guideline included questions on the implementation of climate protection measures, the role of various stakeholders, intersectoral cooperation, resulting conflicts, and changes in local governance. Before each interview, we informed participants about the study's aim and data handling procedures, provided an information letter, and obtained their signed consent. The interviews were conducted via online video conferencing and the audio was transcribed using simple transcription rules.

The interview data obtained in this way were analysed according to the coding and interpretation scheme developed by Charmaz (Reference Charmaz2010). In the initial coding, we identified emerging themes and patterns without preconceived categories, which gave us a first sense of the different forms of governance practised on the ground. The following focused coding helped us to develop more coherent and analytic categories out of the most significant initials codes and memos. The various codes, formed categories, and memos were used to further condense the categories through team discussions and enrich them with theoretical references. This resulted in various interpretations of the material and preliminary reports, which were fed back to the interview partners and supplemented by them.Footnote 1

As a result of this interactive process of analysing developments in the administration and local urban society, we have come to highlight four condensed forms of cross-sectoral interaction, which guide the structure of the presentation of results in chapter five. Although we mention specific features of individual cities where appropriate, a detailed comparison of town-specific differences was not possible at this stage of our research. The limited number of interviews was mainly used to illustrate the four elements that we consider in chapter five to be the common foundations of a new interactive form of governance.

Politics, Administrations, and Actors From the Urban Society—New Developments on Both Sides

Developments in both areas, in politics and public administration as well as in local urban society, represent the background against which new forms of governance are developing and intertwining with traditional ones.

Politics and Administrations

In the towns, we analysed three features stood out: (1) Climate protection plans of the municipalities have become increasingly important, (2) climate protection has established as a cross-cutting issue in the administration, (3) and politics have a decisive influence on corresponding administrative action at the local, and also up to the federal level.

Through climate protection plans, political authorities on the city level have thereby given a strong mandate to the representatives for environmental and/or climate protection in the local public administration in order to implement measures. This can increase their influence on the larger local administrative body. By the notification of explicit figures on pollution and for CO2 reduction in detailed public plans, activists and the local public can refer to more than vague promises and demand the implementation of concrete steps towards the goals set.

‘That means we can refer to it [...] or other groups can refer to it and say, dear town administration, however it says in the climate protection programme that you want to implement this and that. And that simply gives you a bit more pressure, because it is a measure which can be implemented by 2030. And then it is much easier for us to demand it’ (Interview 8, lines 166-171, all interview quotes were translated by the authors).

The towns we looked at now have climate protection managers, appointed a few years ago, who are responsible for climate protection plans and respective projects. They either have an independent staff position or are embedded in environmental departments. The interviews showed that considerable resources have been built up in this area over the past few years. For instance, new staff positions have been created, and the budgets for climate protection have been increased across the board.

One of the challenging aspects of the position of a climate protection manager is that her/his tasks are cross-cutting issues within the administration. Close collaboration with other departments—such as the building or transport departments—is crucial for the extent and speed of progress. ‘In the end it is difficult to really force through climate governance in all departments, so to speak’ (Interview 2, lines 80–82). Therefore, interviewees often expressed their concern with bureaucratic ‘silos’ and hierarchical structures they would like to dismantle in favour of more cooperative horizontal structures.

Since climate protection is a cross-cutting issue, the administration in the respective core sectors of climate policies must find ways to correspond with local politics and politicians who set a supportive framework and agenda. Effective action for climate protection, therefore, needs to be more than an add-on, as it is ‘simply a topic which is very strongly politically driven by various parliamentary groups’ (Interview 3, lines 360–361). Politicians may promise much to the local public. However, they may show a lack of political support and understanding when it comes to the hardships of implementing controversial measures. And then it is.

‘a bit of a strategy, I would say, on the part of the [politicians] to simply say "OK, we'll decide on [ambitious climate protection targets] now and then we'll have reduced the current pressure for the time being". […] I would say that if we then implement this in really operationalised objectives and it is clear what this means, then the backing that the administration has received from the politicians to actually implement these objectives is actually no longer provided’ (Interview 1, lines 85-92).

As for the role of the local administration, much also depends on the nature of the impact of federal and state policies. They can be important sources of mandates and impulses for local climate policy, facilitating implementation on the ground by using favourable legal and financial incentives from the top down.

In addition to the developments within the administration, municipal companies are seen as central players regarding cooperation and implementation. When it comes to investments, infrastructure and services, public suppliers of energy, transport, and facilities such as housing play an important role. These infrastructure areas are intertwined with organisations and individuals as consumers, creating public issues, and regulatory tasks for politics and administration. Traditionally, the local welfare state focused on hospitals, social services, and education. Now, there is a growing emphasis on cooperation with energy providers and public bodies for traffic and housing. Regulations and services must be both socially fair and ecologically sustainable. The respective tasks meet a critical public of consumers, payers, and citizens.

It is unsurprising that municipal companies, in collaboration with the administration, increasingly prioritise advising and educating citizens on energy, pollution, and mobility issues. Topics once handled behind closed doors now demand public debate, campaigns, and accessible advice through counselling centres. Often, these companies commit to the town's climate protection goals, working closely with environmental and climate offices to promote public–private dialogues. Public bodies may take own initiatives by promoting innovative climate protection projects and taking on a pioneering role in some areas such as energy transition or public transport (Interview 11, lines 253–257). The intensity of these collaborations varies across towns, from occasional partnerships to close cooperation on numerous projects, balancing private interests and public commitments.

‘The problem in this instance, however, is that municipal companies, of course, consider themselves to be companies and want to make a profit. And if, let's say, the goals are so ambitious that they are no longer covered by funding programmes, or not sufficiently, and this goal of making a profit is therefore in danger, then they basically close down completely because they say, "OK, no, we are a company. We have to act entrepreneurially”, so to speak’ (Interview 1, lines 151-158).

Developments Among Actors in the Urban Society

Civil society groups and initiatives, as well as representatives of the business community, play a central role in shaping climate protection measures. In the field of climate protection, a simple internet search reveals a broad diversified plural engagement. Many initiatives in the broader field of environmental concerns, such as biodiversity, sustainability, health, and lifestyle, go beyond the narrower issue of local climate governance. Nevertheless, they are an important part of the wider local network that helps to shape the local political climate and development. In recent years, numerous new initiatives have been founded in this field. Genuine environmental protection organisations such as BUND and NABU, which have traditionally focused on biodiversity issues, increasingly have to deal with climate change and thereby broaden their profile.

Within this wide spectrum of engagement, one organised movement, namely Fridays for Future, stands out. In all the communities surveyed, Fridays for Future is active and present with local organisations and own initiatives, bringing together global thinking and local action.

‘But in fact, in the last three or four years, there has certainly been a momentum in my opinion. The social movement in Fridays for Future was the clear trigger. With all the accompanying sub-groups which have since joined or been formed in parallel, however you want to describe it. And this was triggered by social pressure, which was then reflected in the municipal council through corresponding majorities’ (Interview 7, lines 19-24).

More than others, Fridays for Future has succeeded in building up sustained public pressure, which has helped to give climate protection as part of environmental concerns a much higher status in politics and administration.

Overall, the amendment in the conditions for political and administrative action that we observed (in 2022) resulted from a variety of paths taken by initiatives and organisations: influencing local public opinion, raising awareness through new educational institutions, and learning facilities and direct participation in committees and councils.

Climate alliances: This is the label given to new, loosely organised networks that forge links across policy fields that we found in almost all of the towns. An alliance helps to create a voice, increase visibility, public pressure, and larger joint actions. Civil society initiatives dominate in such networks, but socio-economic actors, associations, and businesses (although rarely) can also be involved. These alliances are not always well defined and membership is partly fluid. Who joins forces with whom depends on the respective subject or action involved.

The multitude of different initiatives illustrates that 'civil society’ is a polyvalent and moving field with various activities and actions. However, such alliances are also less institutionalised than other actors, such as an association or a pressure group.

The business sector: Obviously, commercial enterprises play a major role in climate protection—both as large producers of CO2 and as potential partners whose technology and expertise is needed for energy transition projects. When asked about issues of intersectoral cooperation, the interviewees mentioned in particular two concerns: (1) receiving offers from other parties, such as regulators or business-partners (2) and creating exchange forums where dialogues and change-making can be facilitated, agreed upon, and become more accustomed.

‘For example, the town has initiated a climate alliance with companies, where the town approaches companies and invites them to participate as cooperation partners under the label of "climate protection and CO2 reduction". As companies, they have the advantage of gaining a kind of image. They are also advised in the area of monitoring, for what they can do themselves in the area of climate protection and sustainability, to then also show themselves in this climate alliance’ (Interview 11, lines 408-414).

However, some participants from civil society organisations criticised the fact that the negotiations, which are torn between environmental concerns and corporate interests, give more weight to the latter.

‘Where it's probably lacking in some areas is the fact that there is at least the impression among us in [civil society organisation] that large corporations, large business representations are still often permitted to do what they want based on how they feel’ (Interview 12, lines 38-41).

This points to the general problem of the extent interactive cooperation concerning climate protection are matters of power. The outcome of regulations and bargains depends on the status and reputation of each side.

Basic Forms and Dimension of Cross-Sector Interaction

Governance is a multifaceted issue. Attitudes and strategies for interaction across sectors reach from more conflictive to more consent-oriented approaches; they entail hierarchical elements and various forms of negotiation, public debates, and confidential agreements. This chapter will focus on four basic dimensions and recurrent formats of interactive governance.

• Public participation as citizen participation

• Special arrangements for stakeholder participation.

• Visions and discourses beyond public relations.

• Co-production in designing and organising projects and services

Public Participation as Citizen Participation

Our interviews have revealed a wide variety of forms of public participation. They can range from opinion-forming events such as citizens' assemblies and consultative formats like citizens' councils to proactive participation resembling citizens' petitions. These formats were generally seen as positive and necessary by our interviewees.

Citizens’ assemblies organised by the authorities rarely discuss strategic issues. Instead, the focus is on more practical nature, often with the aim of informing citizens. It is often criticised that discussions are limited to commenting on the details of a plan whose main features have already been decided on, rather than engaging in broader debates on fundamental alternatives. Citizens would like to be involved at an earlier stage, while administrators have repeatedly complained about the complexity of procedures that in reality offer nothing more than a multitude of individual objections and reservations.

Most of the towns we looked at have established climate advisory councils. The participants are selected by the administration or policy-makers in order to act in a consultative capacity with the ‘intent to support the local council as an advisory body regarding the subjects of sustainability and climate protection’ (Interview 13, lines 25–27). The background for their selection is expertise in various respects, e.g. involvement in a civil society organisation or professional activity. The establishment of such an advisory board is thus linked to the hope on part of the political and administrative leaders of obtaining a broader support for getting consent.

Citizens' councils are clearly different in that the central criterion for selecting participants is not expertise, but achieving a composition (usually by lottery), that reflects the social, cultural, and political diversity of the local public. As the often used term 'mini-publics' suggests, the selection of participants should provide a platform for joint opinion-forming and related learning processes, that have an impact on the (local) public opinion and decision-makers at large. The Climate Citizens' Council of the Freiburg Region describes its work on its homepage as follows:

‘The participants subsequently work together in a moderated process in order to develop concrete recommendations on a predefined question point. In addition, they are comprehensively informed by experts. In the citizens' council, schoolchildren sit next to pensioners, immigrants to Germany next to people who have been rooted in the region for a long time. The professor talks with the farmer, the apprentice with the master tailor’ (Bürgerrat, 2022).

Both, these citizens' councils and the aforementioned (climate) advisory councils are about citizen participation: While advisory councils, composed of experts and representatives, add legitimacy to decisions by the town parliament or government, citizens' councils present deliberation results from the urban society, bridging the gap between ‘people's will’ and ‘decision-making by representatives’.

Despite the differences between advisory councils and citizens' councils, the challenge is the same: how much weight should be given to the opinion and advice of such public institutions? In the context of a democracy, the decision-making power should remain with the elected bodies and their representatives. It is, therefore, important to ask whether more interactive arrangements might be able to create a ‘win–win’ situation for both sides, rather than inevitably strengthening or weakening only one of them.

Special Arrangements for Stakeholder Participation

The arrangements outlined above focus primarily on the rights of each individual citizen to speak out and participate in public debate. In addition, liberal and plural democracies have a long tradition of ways and arrangements for involving organised concerns and interests in the processes of political decision-making and administration. Nowadays, it is quite common to find special arrangements for involving organised stakeholders, who are deliberately selected and entitled to cooperate because they are directly concerned, experienced or otherwise involved—‘where really specific issues and solution options are worked on with representatives of the urban society’ (Interview 7, lines 335–336). Stakeholder participation is structured on the basis of subjects or special topics, as the following examples in Fig. 1 illustrate.

Fig. 1 Different areas of cooperation by stakeholder participation

While established policy fields know long-standing and routinised forms of stakeholder participation, the emergence of new fields such as (local) climate politics goes along with the challenge to find respective new procedures and platforms. Formalised formats rarely exist and the respective arrangements for the participation of organised stakeholders varies greatly, reaching from the mere collection of comments to day-to-day collaboration on a single project.

This type of participation has its limits when the stakeholders who are actually needed refuse to participate or when it is not possible to work out specific joint solutions down to detail. Our interviewees from the administration sector saw this kind of stakeholder participation as more resource-efficient than procedures of broad public participation: They often need less time, and the statements come from influential organisations that have a strong stake.

Visions and Discourses Beyond Public Relations

What is often overlooked in climate policy debates is that it is not just the opinions of specific initiatives or actors that matter, but public opinion as a whole. This shapes both (1) electoral outcomes and (2) the daily work of organised actors. The first is traditionally part of local politics and involves informing citizens and gaining their support for policies. The second is about the credibility and attractiveness of local climate policies, which requires more than ‘facts and figures’ and ‘public relations’ strategies—it needs a comprehensive discourse and vision of future development, where details and specific measures make sense.

Either way, it is a challenge to reach out to those who are guided by prejudices about certain projects or technologies ‘and [to] all the others […] who are not in the classic ecological and climate bubble, I think that's the difficulty, to address them. To bring them along’ (Interview 10, lines 274–276). Therefore, both the town administration and local organisations are working on reaching out to the broader public and to influence local opinion.

The administration’s objective is to ‘rais[e] awareness for the area of climate protection and climate adaptation’ (Interview 10, lines 76–77). This entails providing transparent information on costs and efforts through targeted advice. To this end, the administration initiates campaigns, produces informational brochures, and organises events. They put a lot of effort in informing the local population and addressing their concerns.

Local civil society organisations aim to raise awareness of the dangers of maintaining the status quo, highlighting the negative consequences of certain projects and proposing alternatives. Their approach extends beyond presenting facts; they seek to shift mindsets and put forward alternative visions, which may influence political parties. The impact of movements like Fridays for Future exemplifies this effort:

‘It's always about the public. It's always about developing public forces. That you make public statements where politics and administration can't get around it anymore, that one places that correctly’ (Interview 6, lines 397-399).

While the means for getting an impact on public opinion will differ on the side of institutionalised politics and the organisations in the local civil society, the shared concern with winning majorities can also facilitate cooperation.

‘We [as the administration] actually need them [committed citizens] to do public relations work in a completely different sense, because they are our multipliers for certain areas which they can represent well themselves. Irrespective of whether this concerns solar energy, be it sustainable consumption. Everything has something to do with climate protection. It could be raising awareness for renewable energies’ (Interview 10, lines 256-259).

In this context, the role of social media is becoming increasingly important. For instance, a ‘citizens' app’ has been developed in some towns and is now utilised to obtain up-to-date opinions on specific plans and projects.

Finally, the credibility and acceptance of actors (whether politicians, administrators, or lobbyists) depend on their ability to align concerns with a compelling vision of the common good, the city, and its environment. Data on CO2 reduction and related projects must be embedded into a narrative that enhances public impact. Public relations gain value when promoting a clear, comprehensible mission for the town and the urban society. While some municipalities rely solely on abstract CO2 reduction targets, others try to formulate an attractive overall concept, a “Leitbild” for urban development in response to climate change. This provides a narrative that outlines goals and pathways, offering a more comprehensive approach to addressing the challenges posed by climate change. Examples of such a policy are professionally organised urban campaigns such as ‘Tübingen macht blau’ (Getting a blue sky for Tübingen) or ‘Grüne Stadt Karlsruhe’ (Karlsruhe: a greening city).

Co-production in Designing and Organising Projects and Services

Traditionally, much of the negotiation and cooperation between the political administration and the urban society is enacted as ‘corporatism’, involving stable interactions with organisations and interest groups. Stakeholder participation, in contrast, focuses on more targeted cooperation and conflict management with a selected group of organisations. However, both formats depend on the willingness of the individual addressee, consumer and cooperator, networks, and neighbourhoods, to actively engage and cooperate.

Many climate policies require more than corporatist agreements and passive acceptance; they demand active cooperation, often referred to as ‘co-production’ (Loeffler & Boviard, Reference Loeffler and Bovaird2020). This involves ongoing cooperation, often accompanied by co-designing the organisational features and technicalities of measures and projects—through corresponding consumption behaviour or one's own co-investments. Initiatives may come from citizens or authorities, through advice or incentives, as in the case of PV systems and proceedings involving all sides in measures for saving electricity. Their design may be generated by a citizens initiative whose joint project is to green-up their neighbourhood. But it can also be initiated by a public investment programme in new sustainable heating systems, which will only work if and to the extent that citizens are willing to act as co-investors.

Respective advisory offers and information services are diverse. They range from energy-saving brochures to information events about the advantages and challenges of installing solar panels on one's own roof and up to cooperation with community initiatives at neighbourhood level.

Energy agencies play a special role in providing advice and information on possibilities, costs, and subsidies. They not only aim to provide advice to individual households, but also to encourage and support community initiatives at neighbourhood level.

‘In my opinion, milestones to date have been the establishment of the energy agency, which was initiated and implemented almost 10 years ago, yes, 7, 8 years ago, as far as I remember. That's when the whole topic started to expand outwards. I think that is a big milestone. Breaking down the topic of climate protection and energy saving to such an extent that it can be grasped and can also be tangible in the wider population’ (Interview 10, lines 20-24).

The development of a culture of collaboration, co-production, and co-design across sectors also necessitates the inclusion of local businesses and companies. Similarly, the approaches employed are diverse. These range from one-to-one consultations to continuous support in the implementation of individual projects and include company networks for peer exchange.

Interactive Governance in Local Climate Politics. A Conclusive Discussion on Findings and Questions Opening up

The aim of our study was to record the development of local climate governance in seven larger towns in Baden-Württemberg. While these findings are not representative of developments at the local level in general, the examples from the chosen towns can illustrate the opportunities and difficulties inherent to a local policy on climate change. Our interviews revealed a high degree of consensus that local climate governance has become a significantly more prominent issue in recent years. This is not only due to the increased material and human resources available to the administration, but also to the greater involvement of political parties and committees, as well as the various forms of engagement of urban society and business. This holds true even though the overall results of the steps taken so far often fall short of the locally set targets for the scope and timing of 'climate-friendly' development.

It soon became quite clear how much such developments are connected with the impulses of social movements in the field of environmentalism, in particular Fridays for Future. At the time of the study’s inception, the movement had a remarkable impact both in the respective towns and by the degree it influenced the political climate in Germany. In a relatively short time, it has resulted in a wide range of features and formats of exchange, consultation, negotiation, and cooperation/collaboration. The fusion of environment-friendly concerns with interactive proceedings involves opening up politics and administration to the urban society. But it also involves that the citizenry articulate themselves not only through protest, but also through calls for participation and an upgrading of active forms of co-design.

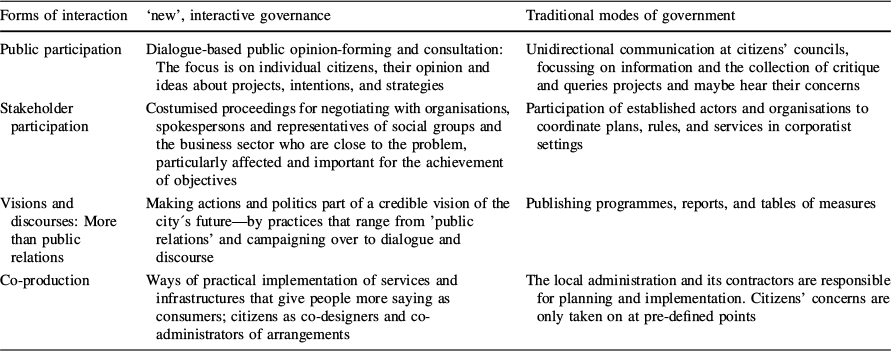

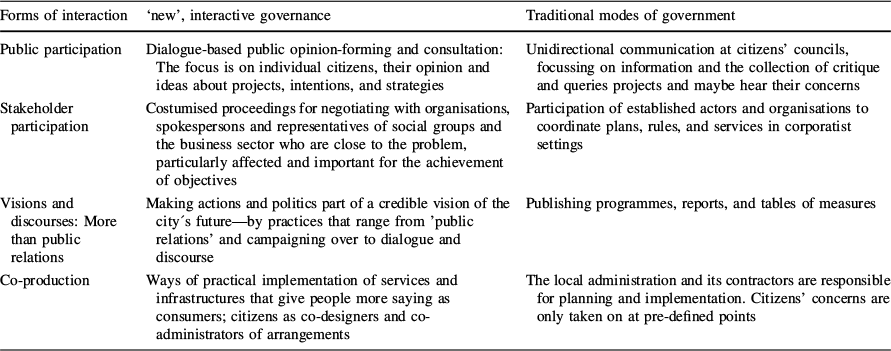

Within the broad field of interaction between institutionalised politics and administrations, business-makers, interest groups, civic organisations, and movements, we categorised four different modes of intermediation. They can be discerned while not being strictly separate from each other, and their impact as parts of interactive governance may vary. Table 1 summarises the four basic changes concerning the interplay between (local) state institutions and the actors in the respective urban societies as we have identified it in the chapters 4 and 5.

Table 1 New modes of interactive governance

Forms of interaction |

‘new’, interactive governance |

Traditional modes of government |

|---|---|---|

Public participation |

Dialogue-based public opinion-forming and consultation: The focus is on individual citizens, their opinion and ideas about projects, intentions, and strategies |

Unidirectional communication at citizens’ councils, focussing on information and the collection of critique and queries projects and maybe hear their concerns |

Stakeholder participation |

Costumised proceedings for negotiating with organisations, spokespersons and representatives of social groups and the business sector who are close to the problem, particularly affected and important for the achievement of objectives |

Participation of established actors and organisations to coordinate plans, rules, and services in corporatist settings |

Visions and discourses: More than public relations |

Making actions and politics part of a credible vision of the city´s future—by practices that range from 'public relations' and campaigning over to dialogue and discourse |

Publishing programmes, reports, and tables of measures |

Co-production |

Ways of practical implementation of services and infrastructures that give people more saying as consumers; citizens as co-designers and co-administrators of arrangements |

The local administration and its contractors are responsible for planning and implementation. Citizens' concerns are only taken on at pre-defined points |

Interactive governance is not a zero-sum game, where more of one thing means less of another, but rather a complex interplay that can influence the democratic substance of politics, the effectiveness of administration, and the scope for action of urban society. Having framed our study on local climate governance accordingly might help to overcome simplifications and to open up questions about the possible meaning and impact of a more interactive governance in the field of climate politics.

What we wanted to overcome by the kind of governance approach we used is the simplification and unclarity entailed in the commonly held debate on more democracy by more civil society participation. Our study has shown that both by tradition and nowadays, trends towards new forms of participation are concerning all actors in society at large, representatives from the business sector as well as from environmental movements or other lobby-groups. By a narrow definition of civil society, its participation is grasping just a part of the challenge to find suitable forms of a more interactive governance. A wide definition of civil society however runs the problem to rate all kinds of participating groups and organisations outside the state in the same positive way.

A consecutive question is about the blend of various forms of participation—such as the right to make decisions through citizens' referenda and the opportunity to exert influence through consultation. What about an appropriate mix of different forms of participation? Should it give priority to strong forms such as referenda? Or, should one give priority to the installing of new forms of consultation and platforms for debate, such as citizen councils, strengthening sensitivity for concerns with the public good among the respective groups and actors?

A final question is concerning the basic status of concepts for reforming governance by making it more interactive. Strengthening interactivity by expanding mutual and sector overarching coordination processes is sometimes traded as the silver bullet for more democracy and more effective administration. However, as Torfing et al. (Reference Torfing, Peters, Pierre and Sorensen2019) have outlined, a modernisation that makes governance more interactive can work both ways, creating gains and risks, more or even less democracy.

With its enclosure of dissent, conflict and protest, changing inherited rules and forms of cooperation, is not per se a way to more democracy and a more efficient climate policy. It is a modernisation of governance, that can work both ways, enhancing or watering down concerns with democracy and climate policy. Therefore, it is all the more important to take an empirical look at the local forms such changes actually take.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Dieter Schwarz Foundation, Federal State of Baden-Württemberg, Robert Bosch Stiftung, Südwestmetall.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

This study was funded by the Federal State of Baden-Württemberg, Robert Bosch Foundation, Dieter Schwarz Foundation and Südwestmetall. The authors declare that they have no financial interests.