Introduction

Family doctors play an important role in motivating patients who smoke to make the decision to stop smoking and to provide relevant treatment, referral, and/or support to do so (Manolios et al., Reference Manolios, Sibeoni, Teixeira, Revah-Levy, Verneuil and Jovic2021, Borland et al., Reference Borland, Balmford, Bishop, Segan, Piterman, Mckay-Brown, Kirby and Tasker2008, Burrows and Carlisle, Reference Burrows and Carlisle2010). Brief advice to patients from their family physician or general practitioner (GP) to stop smoking is effective (Lancaster and Stead, 2004, Zwar and Richmond, Reference Zwar and Richmond2006), however, doctors identify smokers and deliver advice to quit smoking at only modest rates (Papadakis et al., Reference Papadakis, Macdonald, Mullen, Reid, Skulsky and Pipe2010, Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Carey, Sanson-Fisher, Mansfield, Regan and Bisquera2015). Barriers to providing smoking cessation advice include GPs’ beliefs that intervention will not change the patient’s smoking behaviour, competing clinical priorities, and insufficient time, as well as a lack of knowledge and training (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Hersh, Nkoy, Maselli, Srivastava and Cabana2015, Vogt et al., Reference Vogt, Hall and Marteau2005). GPs’ perceptions of patient engagement and patients’ responses to advice about smoking cessation can influence their advice giving (Coleman et al., Reference Coleman, Murphy and Cheater2000, Cunningham, Reference Cunningham2014) as well as a desire to maintain a good relationship with patients (Coleman et al., Reference Coleman, Murphy and Cheater2000, Coleman et al., Reference Coleman, Cheater and Murphy2004, Cunningham, Reference Cunningham2014, Codern-Bove et al., Reference Codern-Bove, Pujol-Ribera, Pla, Gonzalez-Bonilla, Granollers, Ballve, Fanlo and Cabezas2014)

Where smokers report positive experiences with health professionals, they show a willingness to further engage with health providers to help with smoking cessation (Vuong et al., Reference Vuong, Hermiz, Razee, Richmond and Zwar2016). Active referral of smokers to Quitline services appears acceptable to both GPs and their patients (Borland et al., Reference Borland, Balmford, Bishop, Segan, Piterman, Mckay-Brown, Kirby and Tasker2008). On the other hand, concerns persist that patients may express anger at being told what to do by health professionals and resent actions towards attempts at external control by health providers (Burrows and Carlisle, Reference Burrows and Carlisle2010). Highly directive and recurrent, or unwelcome smoking cessation advice, can be counterproductive (Burrows and Carlisle, Reference Burrows and Carlisle2010, Hansen and Nelson, Reference Hansen and Nelson2011, Irvine et al., Reference Irvine, Crombie, Clark, Slane, Feyerbend, Goodman and Carter1999). Interactions with health professionals can serve to reinforce feelings of being judged and blamed for past smoking behaviours, and smokers may be particularly vulnerable to poor patient experience of care and stigma in health settings (Boland et al., Reference Boland, Mattick, Mcrobbie, Siahpush and Courtney2017, Madawala et al., Reference Madawala, Warren, Osadnik and Barton2023c).

Qualitative studies suggest that patient experience is an area of concern for patients who smoke, whose anticipation of stigma in healthcare settings can affect the disclosure of information and effective partnership with healthcare providers, particularly in the context of smoking-related chronic illness or cancer (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Crane, Lafontaine, Seale and Currow2015, Carter-Harris, Reference Carter-Harris2015, Oliver, Reference Oliver2001, Madawala et al., Reference Madawala, Osadnik, Warren, Kasiviswanathan and Barton2023b). Smokers internalizing smoking-related negative stereotypes has been associated with increased resistance to smoking cessation advice and the purposeful non-disclosure of smoking status to healthcare providers (Evans-Polce et al., Reference Evans-Polce, Castaldelli-Maia, Schomerus and Evans-Lacko2015, Halladay et al., Reference Halladay, Vu, Ripley-Moffitt, Gupta, O’Meara and Goldstein2015). Smokers experience stigma in a variety of contexts and these feelings are particularly harmful within healthcare settings where ‘anticipated’ stigma may act as a barrier to accessing health care in the future or delaying seeking care until a crisis point (Earnshaw et al., Reference Earnshaw, Quinn and Park2012, Earnshaw and Quinn, Reference Earnshaw and Quinn2011).

About 10% of smokers in Australia will speak with a GP for help to quit smoking (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2020). Smokers expect to be asked about smoking by their GP and consider it to be both part of their GPs clinical duties as well as showing concern for their health (Papadakis et al., Reference Papadakis, Anastasaki, Papadakaki, Antonopoulou, Chliveros, Daskalaki, Varthalis, Triantafyllou, Vasilaki, Mcewen and Lionis2020, Manolios et al., Reference Manolios, Sibeoni, Teixeira, Revah-Levy, Verneuil and Jovic2021). Large studies of smokers’ experiences of care and ratings of health providers in the USA found that among patients enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare programmes, the frequency of discussions about smoking cessation was positively associated with the overall rating of healthcare providers (Holla et al., Reference Holla, Brantley and Ku2018, Winpenny et al., Reference Winpenny, Elliot, Haas, Haviland, Orr, Shadel, Ma, Friedberg and Cleary2017). Healthcare providers who ‘always’ asked about smoking were rated more highly than those who did not (Winpenny et al., Reference Winpenny, Elliot, Haas, Haviland, Orr, Shadel, Ma, Friedberg and Cleary2017). The rating of Medicaid patients’ physicians increased as they received at least some smoking cessation advice. The rating increased even more when options for smoking cessation medications or other smoking cessation methods were discussed. Both studies concluded that giving smoking cessation advice is not detrimental to the experience of care and may reflect better quality of care among Medicaid and Medicare patient populations.

This study aimed to determine if differences exist in the perceived experience of primary care between a general population of primary care patients who currently smoke or had recently quit smoking and if the frequency of advice to quit smoking from GPs or other healthcare providers at a GP’s practice is associated with ratings of health care of Australian general practitioners.

Methods

Participants and sampling

A cross-sectional, nationwide survey of Australian smokers and ex-smokers was undertaken between December 2019 and January 2020, prior to the introduction of COVID-19 restrictions in Australia. A link to the study survey was promoted on social media using paid adverts on Facebook and Instagram. Two rounds of trial ads were tested using six different combinations of images and text before deciding on three final ads that were run until the estimated minimum sample size (n = 180 per group (smokers/past smokers) had been exceeded. Individuals who clicked on the study advertisement were taken to an online survey in Qualtrics XM software (Qualtrics, Seattle, WA). Respondents completed a set of screening questions to assess eligibility which included age (≥ 35 years old), smoking status (current smoker or ex-smoker who had quit within the last 5 years), living in Australia, and having visited a GP for their own health in the last 12 months. Respondents were offered the opportunity to enter into a prize draw to win one of 12, $25 gift vouchers.

The survey landing page contained brief information about the study and a link to the detailed study Explanatory Statement. Consent was indicated by clicking through to the survey from the survey landing page. The study was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Application No. 17126).

Data collection

Data were collected from a single, online survey (median completion time 9 minutes). Smoking status was determined by a single question that asked, ‘How often do you now smoke cigarettes, pipes, or other tobacco products?’ Current smokers were defined as participants who smoked either daily, at least once a week, or less than weekly. Participants who self-reported they did not smoke at all, at the time of completing the survey, but who reported having been a regular smoker in the past, were defined as ex-smokers. Amongst current smokers, tobacco dependency was assessed using questions from the Fagerstrom nicotine dependence test (Heatherton et al., Reference Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker and Fagerstrom1991).

Questions about quit smoking advice from GPs or other healthcare providers at their GP practice were adapted for an Australian setting from Winpenny et al (Winpenny et al., Reference Winpenny, Elliot, Haas, Haviland, Orr, Shadel, Ma, Friedberg and Cleary2017). We asked, ‘In the last 12 months how often, if at all, were you advised to quit smoking by a GP or other healthcare provider at your GP’s practice?’ Respondents who had been advised to quit smoking were subsequently asked, ‘Did they advise you in a way that made you feel motivated to try to quit?’, ‘did you try to quit smoking?’, ‘how important do you think it is for you to quit smoking?’, and ‘when did you last attempt to quit?’ Ex-smokers were asked, ‘Do you think help from a GP contributed to you quitting successfully?’

Patient experience questions were derived from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Patient Experience Survey (PEx) (General Practice questions sub-set) (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2019) and the Consumer Assessment of Health Care Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey. The ABS PEx survey assesses the experience of health services at a system level. That is, questions are not asked about encounters with individual providers, but with all GPs a patient has seen in the past 12 months. This is particularly appropriate for the Australian healthcare system in which patients are able to choose their primary care provider and do not need to register with a single provider or general practice. They are able to seek and receive care from different healthcare providers within a practice or from different practices.

In addition to the ABS PEx survey questions, questions adapted from the CAHPS survey were used to assess perceptions of the broader clinic environment and overall rating of care. Two questions were asked about patient views on how they were treated by clerks and receptionists in the practice. Overall rating of care was assessed by the question ‘using any number from 0 to 10, where 0 is the worst care possible and 10 is the best care possible, what number would you use to rate the care received from GPs?’

We determined the degree to which respondents ‘anticipated’ experiencing stigma in primary care settings using four items from the Chronic Illness Anticipated Stigma Scale – healthcare provider sub-scale (Earnshaw et al., Reference Earnshaw, Quinn, Kalichman and Park2013) (A healthcare worker will – be frustrated with you; will give you poor care; will blame you for not getting better; will think you’re a bad patient). Each item was scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from very unlikely to very likely. This instrument has been shown previously to have good reliability and validity among people living with chronic illnesses (Earnshaw et al., Reference Earnshaw, Quinn, Kalichman and Park2013). Finally, respondents answered questions about self-perceived health status, demographic, and social circumstances. These questions included age, gender, postcode (from which we determined the relative level of socio-economic advantage and disadvantage) (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2018), highest level of education, availability of social support, employment, and marital status.

Data analysis

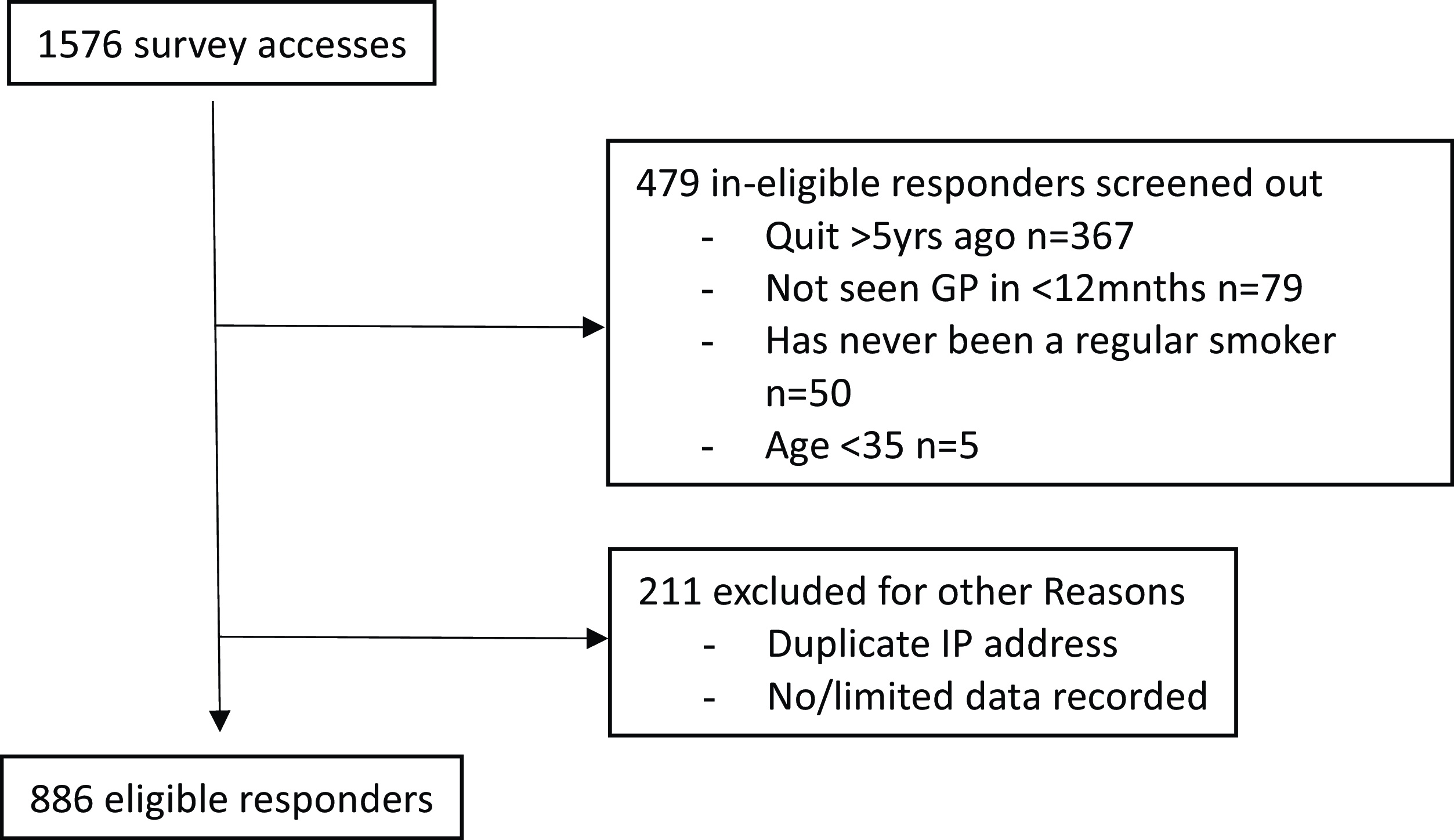

Data were downloaded from Qualtrics to SPSS Version 28 for analysis (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, NY, 2021). We checked the user IP address, and where the same IP address was recorded more than once, we retained data from the first record only for analysis. Respondents who completed the screening questions but did not answer any questions in the main question set were also removed prior to analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram showing the flow of participants into the study and reasons for exclusion.

Differences in socio-demographic characteristics of smokers and ex-smokers were assessed using Chi-Squared tests for categorical variables and independent sample t-tests or One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. Questions concerning the patient experience of primary care were divided into domains that included access to healthcare services, the clinic environment, relational experiences, and overall rating of care from GPs. A small number of current smokers (n = 19, 3.1%) were identified as using ‘only other’ tobacco products and were excluded from subsequent analyses. Logistic regression was used to determine differences between smokers’ and ex-smokers’ experiences of care across each domain of patient experience of care, adjusting for socio-demographic characteristics and self-rated health. Secondly, among current smokers, odds ratios were calculated from logistic regression to determine associations between the binary variables ‘advised to quit smoking’ (sometimes/never vs always/usually), and ‘advised in a way that motivated you to try to quit’ (no/not really vs yes).

P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

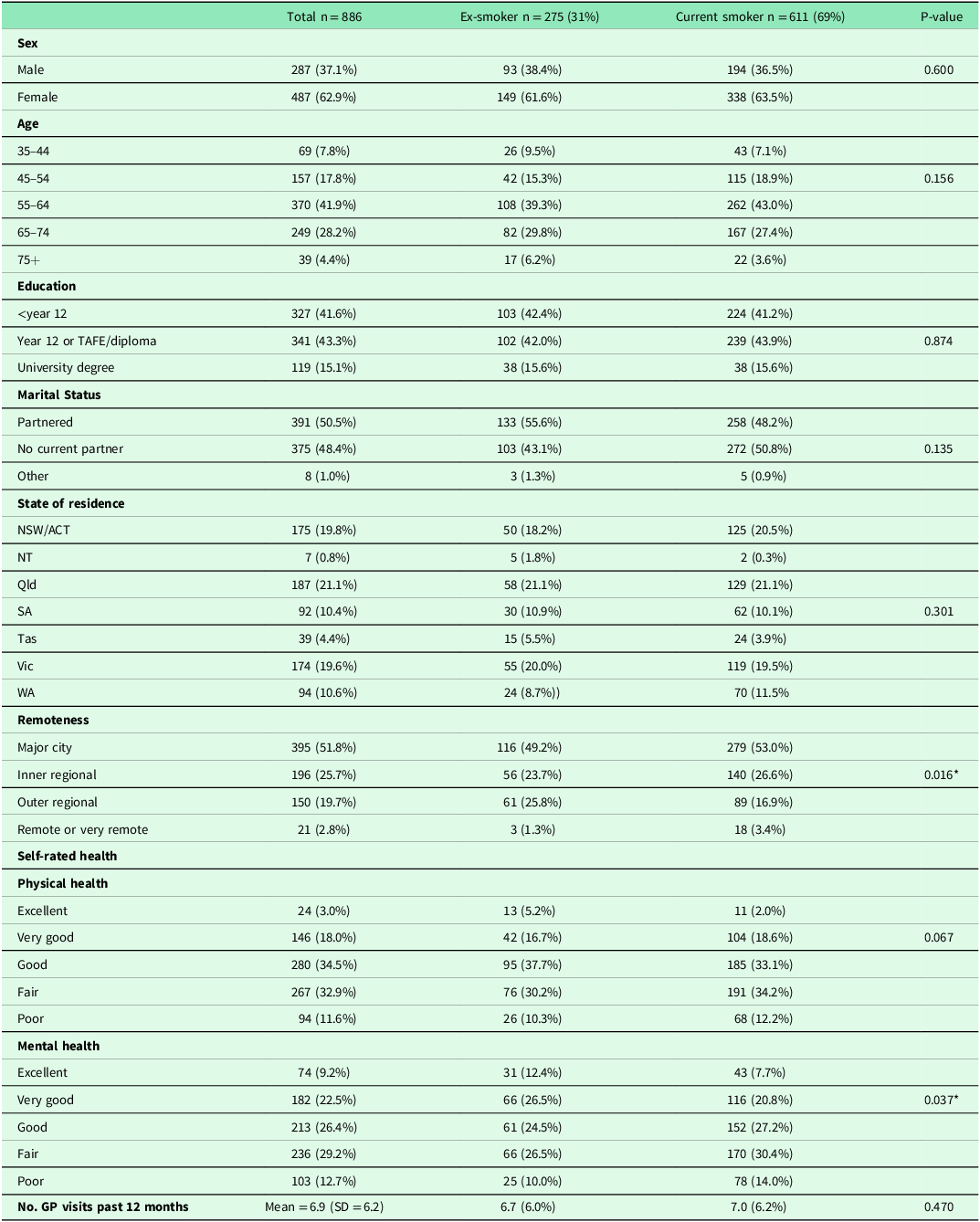

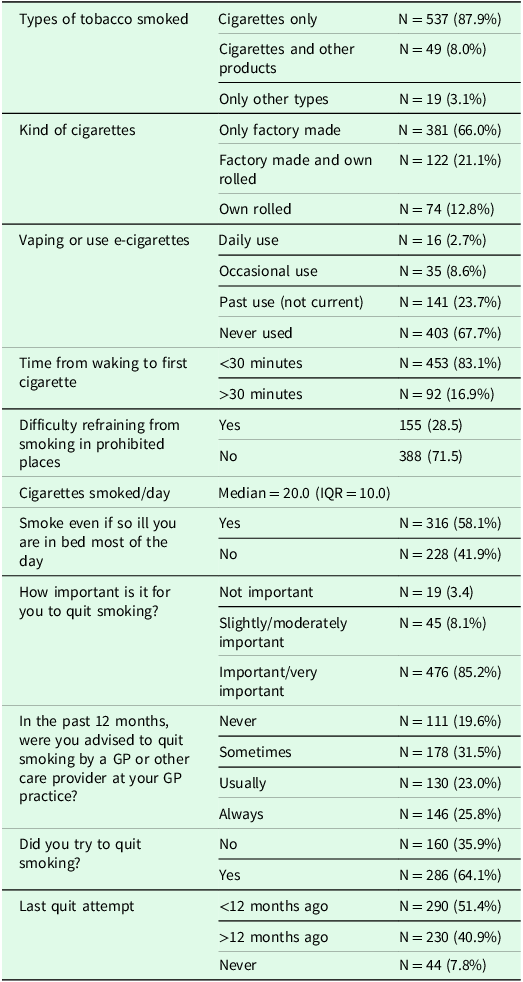

A total of 886 responses were retained for analysis (Figure 1). Respondents were either current smokers (n = 611) or ex-smokers who had quit smoking tobacco cigarettes within the last 5 years (n = 275). Ages ranged from 35 to 83 years and respondents reported a mean of 6.9 visits to a GP in the past 12 months (Table 1). Current smokers were more likely to live in metropolitan areas and had significantly poorer self-rated health than ex-smokers (Table 1). Additional characteristics of smokers are presented in Table 2. Most smoked factory-made cigarettes (66.0%) and 11.3% reported dual use of e-cigarettes. More than four in five reported smoking within 30 minutes of waking (Table 2).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of respondents

TAFE = Technical and Further Education.

Table 2. Characteristics of smokers

Most smokers (85.2%) indicated that it was ‘very important’ or ‘important’ to them to quit smoking and nearly two in three (64.1%) reported they had tried to quit smoking, with more than half (51.4%) having tried to quit smoking within the last 12 months. Despite this, fewer than half (48.8%) recalled being advised to quit smoking (‘usually’ or ‘always’) by their GPs in the last 12 months.

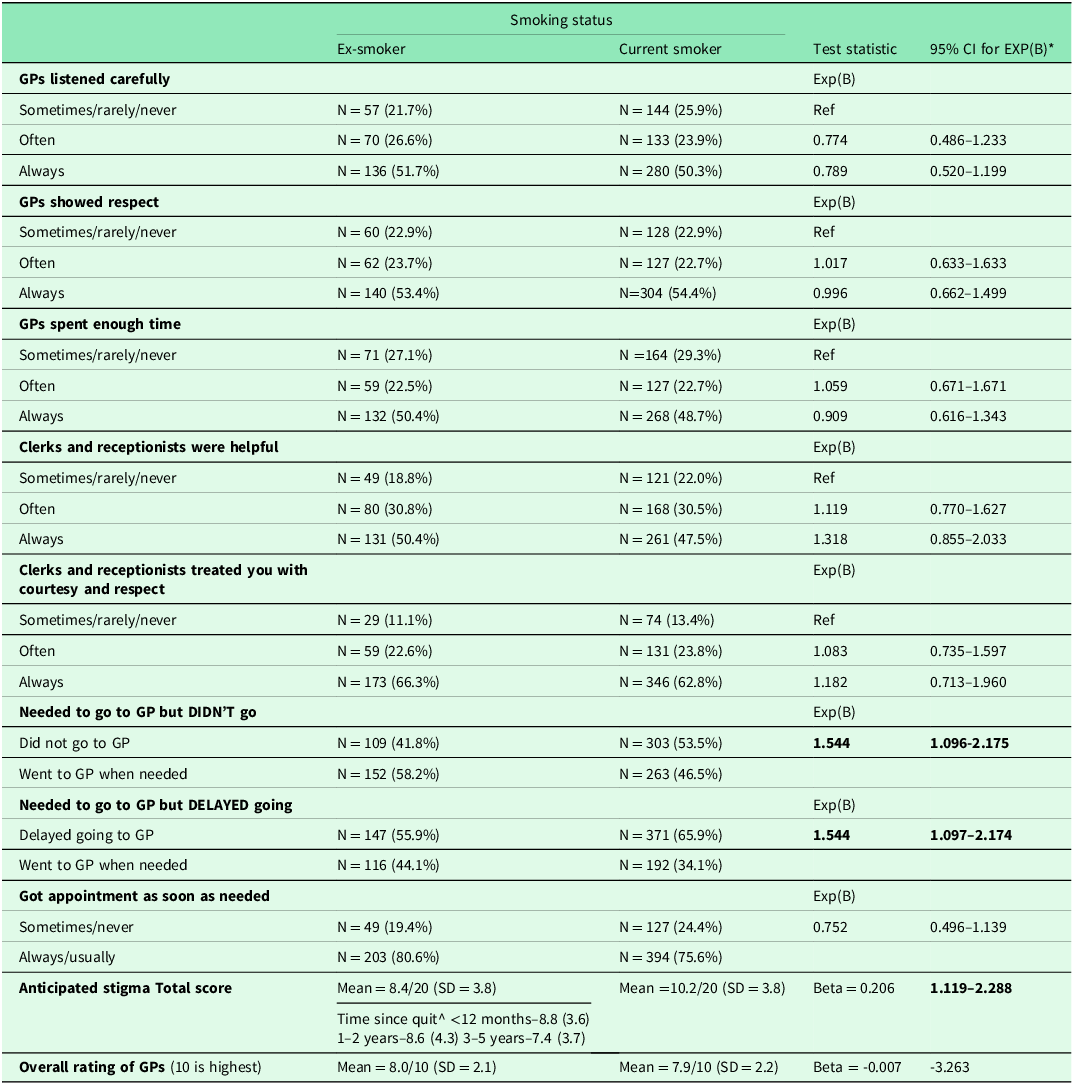

Differences in patient experience between smokers and ex-smokers

Relational experiences of care such as feeling listened to, being shown respect, and having felt GPs spent enough time with them did not differ between smokers and ex-smokers (Table 3). However, current smokers were significantly more likely to delay seeking care or avoid going to a GP when needed (Table 3). Anticipated stigma was significantly higher among current smokers compared to ex-smokers (mean = 10.2 vs 8.4, p < 0.001) and tended to decline the longer a person had quit smoking (Rho = -0.243, p < 0.001). Overall rating of care did not differ between smokers and ex-smokers (mean = 8.0 vs 7.9, p = 0.848).

Table 3. Differences between smokers^ and ex-smokers in experience of care

*Adjusted for age, sex, Socio-Economic Index For Area (SEIFA) decile, education, remoteness, and self-rated health; ^Excludes current smokers who only used ‘other tobacco’ products.

Patient experience and frequency of smoking cessation advice

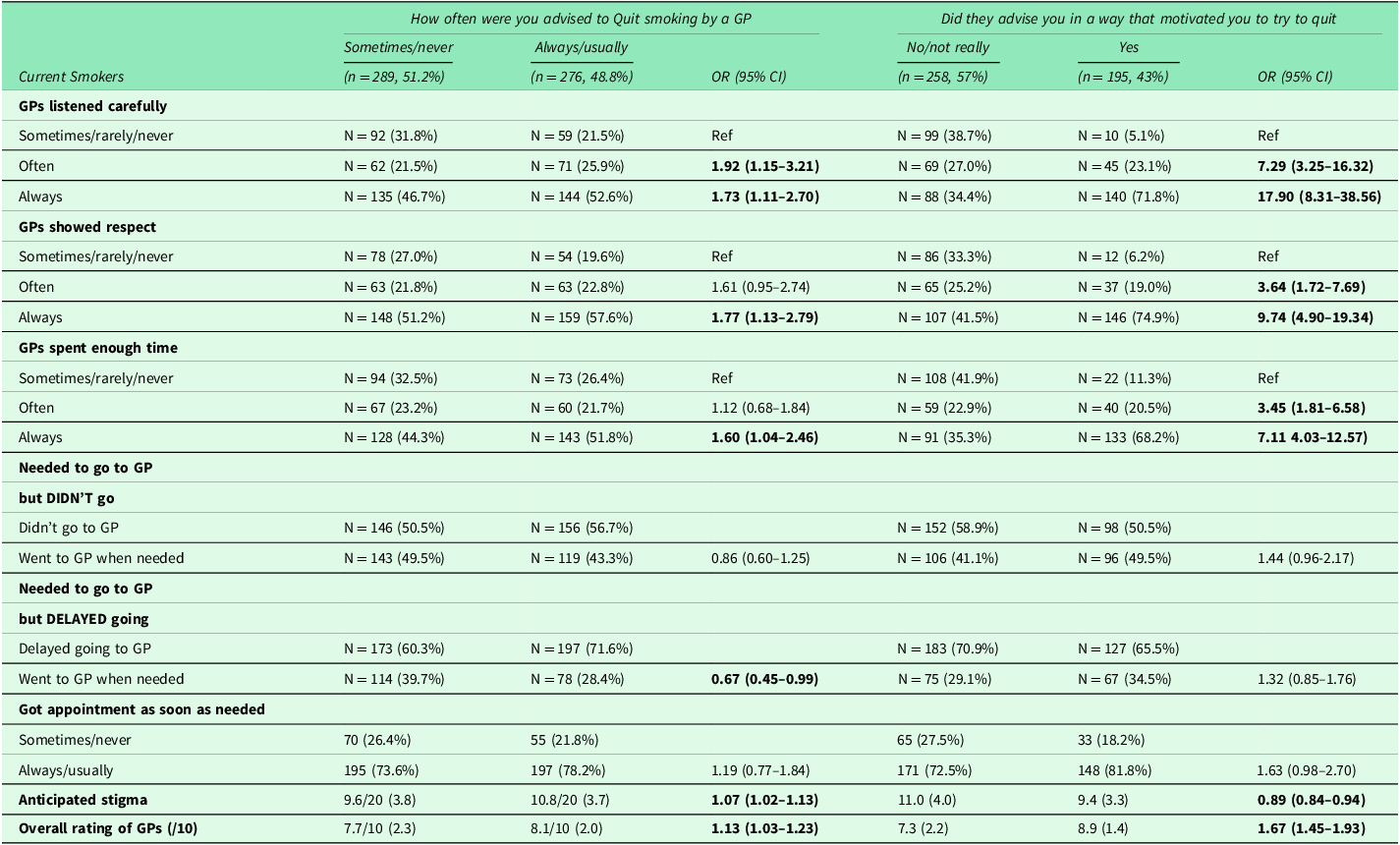

Respondents who reported their GP or other healthcare provider at their GPs’ practices advised them to quit smoking ‘always or usually’ were most likely to report their GPs ‘always’ listened carefully, showed respect, and spent enough time with them (Table 4) and advised them in a way that motivated them to try to quit smoking (Table 4). Overall rating of GPs’ care was higher when respondents reported their GP always or usually advised them to quit smoking and advised them in a way that motivated them to try to quit (Table 4).

Table 4. Logistic regression analyses of patient experience of care by advice to quit smoking

*Adjusted for age, gender, Socio-Economic Index For Area (SEIFA) decile, education, remoteness, and self-rated health.

Conversely, smokers reporting more frequent advice to quit smoking also reported greater anticipation of stigma in health settings (10.8 vs 9.6, p < 0.001) (Table 4), and respondents who always or usually were advised to quit smoking were 33% less likely to go to their GP when they needed (Table 4).

Discussion

The principal finding from this study is that asking patients who smoke about their smoking behaviour did not negatively impact the rating of the care that they received from GPs. It seems that patients realize that GPs have an important role in asking about smoking and this is likely seen as an indicator of high-quality care. Despite this, up to one-third of respondents seemed to dread these questions and reported delaying or avoiding seeking health care when they needed it. Patients who reported they were advised to quit smoking in a way that motivated them to try to quit felt listened to and felt their GPs showed respect and spent enough time with them. Relational experiences of care (feeling listened to, being shown respect, having enough time with GPs) were rated the same between patients who were current smokers and those who were ex-smokers. Of concern, however, was the finding that respondents who were current smokers reported higher scores for anticipation of stigma and were most likely to delay or avoid going to a GP when needed.

Our finding that the overall rating of care received from GPs was perceived to be higher among those who were more frequently advised to quit smoking is consistent with patient experience surveys conducted in the USA (Winpenny et al., Reference Winpenny, Elliot, Haas, Haviland, Orr, Shadel, Ma, Friedberg and Cleary2017, Holla et al., Reference Holla, Brantley and Ku2018), as well as other studies of smokers satisfaction with primary care (Conroy et al., Reference Conroy, Majchrzak, Regan, Silverman, Schneider and Rigotti2005, Barzilai et al., Reference Barzilai, Goodwin, Zyzanski and Stange2001). Together, these findings provide support for recommendations in smoking cessation guidelines that healthcare providers should provide advice to quit smoking ‘at every opportunity’ and that healthcare providers can approach this task with confidence. The combination of higher overall ratings and more positive ratings of relational experiences of care neutralizes concerns that advising smokers to quit smoking may damage the doctor–patient relationship (Coleman et al., Reference Coleman, Murphy and Cheater2000).

However, these messages need to be provided sensitively. One concerning finding was that ratings of patient experience among this sample were substantially lower than those reported for the general primary care population in Australia. In particular, the higher anticipation of stigma in health settings reported by this group was a concern, particularly among the group who were current smokers.

‘Anticipated’ stigma reflects the extent to which people expect to experience stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination directed at them from others in the future (Earnshaw and Quinn, Reference Earnshaw and Quinn2011, Earnshaw et al., Reference Earnshaw, Quinn and Park2012). It can arise from internalized stigma and experiences of stigma but also from fear of discrimination or stereotyping and judgement in the future and is an important predictor of delayed and avoided help-seeking among primary care patients with chronic respiratory illness (Madawala et al., Reference Madawala, Enticott, Sturgiss, Selamoglu and Barton2023a). The concept encompasses the extent to which people think a status is stigmatized in their environment and not just what they personally have experienced (Earnshaw et al., Reference Earnshaw, Quinn, Kalichman and Park2013).

These results are consistent with studies of other stigmatized populations in primary care. The language healthcare providers use in speaking with these patients can be different and unconscious or unintentional bias can result in people being treated differently or unfairly and contribute to experiences of stigma in healthcare settings (Wilson, Reference Wilson2020, Thille, Reference Thille2019) and loss of trust (Kasiviswanathan et al., Reference Kasiviswanathan, Enticott, Madawala, Selamoglu, Sturgiss and Barton2025). Our findings that anticipated stigma is lower once patients quit smoking and tends to slowly decline over time but can persist up to five years from when an individual has quit smoking.

Limitations

This study aimed to reach a general population aged 35 years and over, responding to advertisements on Facebook and Instagram. It is possible that users of these services with more negative experiences may have been more likely to complete the survey, possibly explaining the overall more negative views expressed here about experience of care, compared with representative samples. As such further studies, utilizing representative sampling techniques, are required to confirm the findings presented here. Data collection for the study was completed just prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and so the findings do not reflect any changes in healthcare access and experience in primary care during the pandemic.

Using social media provided an opportunity to recruit a sample from across Australia. Social media has been found to be a viable recruitment method for current and ex-smokers, who can be challenging to reach and recruit into research if they have experienced smoking-related stigma (Carter-Harris et al., Reference Carter-Harris, Ellis, Warrick and Rawl2016, Frandsen et al., Reference Frandsen, Walters and Ferguson2014). We limited participation to individuals aged 35 years and older to allow for a greater range of smoking-related experiences and risk for smoking-related illness. The results should not be generalized to younger smokers and ex-smokers who may have different experiences of care to older adults. Nonetheless, the characteristics of smokers in our sample closely reflect characteristics of smokers reported in Australia’s 2019 National Drug Strategy Household Survey in terms of types of cigarettes smoked, use of e-cigarettes, and the proportion who had tried to quit but were not successful, although our sample tended to smoke more cigarettes per day than the national average.

A further limitation relates to our assessment of patient experience of care. We measured experience by self-report, using items from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Patient Experience Survey. These questions asked respondents about all experiences of care (in general practice) but not about specific episodes of care. As such, our results need to be interpreted as general perceptions of encounters with primary care providers, not specific ones in which smoking was mentioned (if it was in some). We did not ask about the number of different GPs participants had visited or if care was provided by a preferred or regular GP. Ratings of care may be different if a single point of reference was used or if questions were asked about a preferred or usual provider. Lastly, these questions ask about experiences of care in the past 12 months, and there is a risk of recall bias, particularly if care had not been sought recently.

Conclusion

Frequent advice to quit smoking appears acceptable to primary care patients with a smoking history, especially from GPs who provide advice in a way that is motivating to the smoker. This study provides further strength to evidence that the provision of smoking advice at every visit, as recommended by guidelines, does not negatively impact the doctor–patient relationship or ratings of care. In fact, higher ratings of care were given by patients who were asked about smoking cessation more frequently, an outcome that has been linked to better quality of care in general (Winpenny et al., Reference Winpenny, Elliot, Haas, Haviland, Orr, Shadel, Ma, Friedberg and Cleary2017). However, this needs to be balanced with the concerning finding of delayed help seeking, particularly for patients who expect their GP to ask them about their smoking. This emphasizes the importance of asking about smoking and providing advice to quit in a supportive, non-judgemental way, by partnering with the patient, sharing power, and listening to them carefully.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the study was received from the Shepherd Foundation, Victoria, Australia.

Author contributions

The study was conceptualized by CB, JE, JG, and RB who were also responsible for the funding acquisition. CB, MS, SM, JE, JG, and RB contributed to the methodology and investigation. CB, MW, and JE conducted the formal analysis. CB and MS were responsible for project administration and data curation. CB and MW wrote the original draft. All authors contributed to review and editing and approved the final version.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.