1. Introduction

Stably stratified (vertical) shear flows, where both the background fluid buoyancy (i.e. the appropriately scaled negative density perturbation) and horizontal flow velocity vary with height, are ubiquitous in geophysical contexts. There has been a very large body of work considering the ways in which such flows behave (as evidenced by a sequence of reviews such as Fernando (Reference Fernando1991), Peltier & Caulfield (Reference Peltier and Caulfield2003), Ivey, Winters & Koseff (Reference Ivey, Winters and Koseff2008), Caulfield (Reference Caulfield2020) and Caulfield (Reference Caulfield2021)), with significant focus on the (possible) existence of turbulence extracting and converting the kinetic energy in the background shear and the associated enhanced (irreversible) turbulent mixing. Understanding (and parameterising) such turbulent mixing of stratified fluids is a key challenge in geophysical flows, as the transport of momentum, heat and other scalars (such as dissolved gases, pollution and microplastics for example) is both a crucial process and a phenomenon of great uncertainty for the description of the world’s climate and environment (see for example the reviews of Wunsch & Ferrari (Reference Wunsch and Ferrari2004), Ferrari & Wunsch (Reference Ferrari and Wunsch2009) and Gregg et al. (Reference Gregg, D’Asaro, Riley and Kunze2018)).

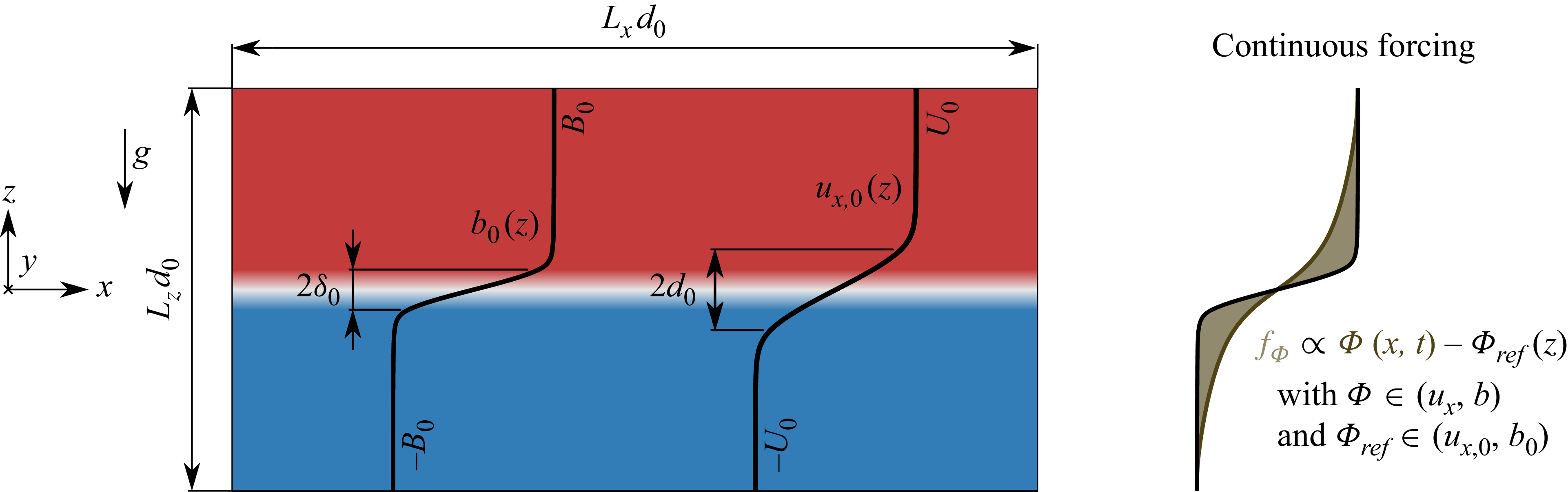

In essence, as shown schematically in figure 1, stably stratified shear flows are characterised by a competition between a stabilising buoyancy and a de-stabilising velocity (or shear) profile. However, gaining an understanding of fundamental aspects of this deceptively simple set-up continues to prove exceptionally complicated. Considering initial-value problems of (initially) laminar velocity and density profiles, it is well known that such flows can be prone to a range of primary flow instabilities (see the review of Caulfield Reference Caulfield2021) that effectively rearrange the strip of spanwise vorticity into trains of elliptical vortices (such as the classic Kelvin–Helmholtz ‘billows’, i.e. the saturated manifestation of the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability (KHI)). As these vortices themselves are prone (at least for sufficiently high Reynolds number) to a ‘zoo’ of secondary instabilities (a nomenclature proposed by Mashayek & Peltier Reference Mashayek and Peltier2012a , Reference Mashayek and Peltierb ), turbulence transition is triggered and mixing as well as dissipation are eventually significantly enhanced.

Such mixing events can extend for a significant length of time – particularly when the flow is prone primarily to the so-called ‘Holmboe wave instability’ (HWI) (Holmboe Reference Holmboe1962), as discussed in detail by Salehipour et al. (Reference Salehipour, Caulfield and Peltier2016, Reference Salehipour, Peltier and Caulfield2018) – and can also be accompanied by the formation of larger-scale emergent structures, especially in sufficiently spatially extended flow domains (Watanabe & Nagata Reference Watanabe and Nagata2021). The particular life cycle of such mixing events can be strongly sensitive to initial conditions, as demonstrated conclusively by Liu, Kaminski & Smyth (Reference Liu, Kaminski and Smyth2022), due to competition between different members of the secondary instability ‘zoo’, especially involving the subharmonic ‘pairing’ instability of neighbouring primary Kelvin–Helmholtz billows. As demonstrated by Mashayek & Peltier (Reference Mashayek and Peltier2013), sufficiently strong stratification can disrupt and hence suppress such pairing (or more precisely ‘merging’) events due to the energetic costs of the inherent vertical motions. Given only finite computational resources, such suppression is often cited as a reason to restrict (the inevitably finite) domains to one (or at most two) wavelengths of the primary instabilities, allowing for higher Reynolds numbers.

However, the horizontal extent of the (numerical or experimental) domain may clearly affect the flow dynamics. As shown by Scinocca & Ford (Reference Scinocca and Ford2000), a rich dynamics can occur in longer streamwise domains, where primary instabilities with close wavelengths (and hence close linear growth rates) can compete as they grow to finite amplitude if the (conventional) imposition of periodic streamwise boundary conditions does not quantise the accessible wavelengths of possible instabilities too severely. Analogous issues also arise in the spanwise direction. Many studies consider relatively narrow domains, in the sense that the spanwise extent is (often significantly) smaller than the characteristic (streamwise) wavelength of the primary instability. Such domains allow many of the (essentially local) secondary instabilities to develop and hence trigger turbulence transition. However, as can be straightforwardly observed in sufficiently wide tilting tank experiments (Thorpe Reference Thorpe1985, Reference Thorpe1987; Caulfield, Yoshida & Peltier Reference Caulfield, Yoshida and Peltier1996; Thorpe Reference Thorpe2002) and sufficiently wide computational domains, as clearly demonstrated by Fritts et al. (Reference Fritts, Lund and Thorpe2022a , Reference Fritts, Wang, Thorpe and Lundb ), inherently three-dimensional ‘knots’, ‘tubes’ and billow ‘defects’ can develop in the spanwise direction on scales of the order of (but typically larger than) the primary instability’s most unstable streamwise wavelength.

Figure 1. Configuration of the forced stratified shear flows considered here. While the initial buoyancy profile

![]() $b_{0}$

is statically stable, the imposed initial velocity profile

$b_{0}$

is statically stable, the imposed initial velocity profile

![]() $u_{x, 0}$

may induce flow instabilities that lead to a transition to turbulence. A continuous forcing

$u_{x, 0}$

may induce flow instabilities that lead to a transition to turbulence. A continuous forcing

![]() $f_{\varPhi }$

may inject the required energy to sustain this turbulence, ensuring statistically stationary dynamics.

$f_{\varPhi }$

may inject the required energy to sustain this turbulence, ensuring statistically stationary dynamics.

Moreover, there will always be an inevitable decay of these reported flow structures unless the underlying driving mechanism (i.e. the shear) is replenished. Although such initial-value-problem mixing events are undoubtedly of geophysical interest and indeed demonstrate the formation of a transient larger-scale dynamics exhibiting the so-called ‘life cycle’ of a shear-driven mixing event, it is important to remember that such initial-value-problem mixing events are really just one end-member class of the possible flows of geophysical interest.

The other obvious end-member class is the class of continuously forced flows, where the ‘background’ velocity and density (or equivalently buoyancy) profiles are driven by some external, quasi-steady forcing. Possible candidate mechanisms for such geophysically relevant forcings include wind, solar radiation and resulting evaporation at the surface of the ocean (Thorpe Reference Thorpe2005), tidal forcing (Laurent, Simmons & Jayne Reference Laurent, Simmons and Jayne2002), active matter living in water (Castro et al. Reference Castro, Pena, Nogueira, Gilcoto, Broullon, Comesana, Bouffard, Garabato and Mourino-Carballido2022) or continuous outflows from rivers (Uncles & Mitchell Reference Uncles and Mitchell2011). While this list is not meant to be complete in any sense, it illustrates that quasi-steady forcings do occur in geophysically relevant situations. An (artificial) volumetric forcing is a particularly convenient way to mimic these natural complex mechanisms in a simplified manner. As visualised on the right side of figure 1, such a forcing may be defined to relax the time-dependent local profiles.

Such a forcing was introduced by Smith, Caulfield & Taylor (Reference Smith, Caulfield and Taylor2021), who demonstrated that – after an initial transient where primary instabilities (either KHI or HWI) develop and (inevitably) break down – the ensuing turbulence could be sustained over arbitrarily long times, thus enabling statistically steady statistics of the flow to be calculated. There is a clear attraction to considering such forced flows due principally to the inherent removal of the confounding effects of the life cycle of the mixing event from the turbulence statistics. Therefore, such flows seem the natural test bed to study the emergent and sustained turbulent self-organisation of the flow on large scales. This endeavour, however, comes necessarily with the challenge of first diagnosing whether or not there is actually an inherent convergence of the resulting depth of the turbulent shear layer, and second, identifying its minimal required extent to enable such statistical convergence (that is unbiased by the extent of the domain).

Given that Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Caulfield and Taylor2021), similar to the initial-value-problem flows discussed above, also considered relatively small computational domains only, it is not at all clear whether or not their statistically stationary flow remained unaffected by the computational domain size. An equivalent question to ask is ‘what are the unconstrained emergent length scales of a forced stratified shear flow?’ Answering that (open) question is the central objective of this paper.

To address this objective, the rest of the paper is organised as follows. In § 2 we present our numerical approach before we list the range of considered control parameters and computational domains at the start of § 3. For simplicity, we focus on one set of parameters that enables a relatively weakly stratified flow which is prone to primary KHI. After briefly identifying some interesting early-time dynamics that may possibly be affected by molecular diffusion due to the choice of control parameters (but is not of principal interest here), we shift our focus to the statistically steady turbulent state that is sustained by the volumetric forcing. We identify emergent, strongly anisotropic length scales which are proven to converge in sufficiently extended domains. We demonstrate conclusively that key statistics of the flow, including in particular those related to irreversible mixing, are sensitive to the large-scale self-organisation of the flow or equivalently the extent of the computational domain. From a practical perspective, we remark that for convergent statistics, perhaps surprisingly, the flow domain may need to be extraordinarily extended (i.e. of order

![]() $100$

times larger) compared with the initial shear layer half-depth. Focusing on the flow physics, in § 4 we propose the dynamical origin of and discuss the implications of the discovered emergent large-scale dynamics. Finally, we draw our conclusions in § 5.

$100$

times larger) compared with the initial shear layer half-depth. Focusing on the flow physics, in § 4 we propose the dynamical origin of and discuss the implications of the discovered emergent large-scale dynamics. Finally, we draw our conclusions in § 5.

2. Numerical approach

2.1. Governing equations

We consider an incompressible flow based on the Oberbeck–Boussinesq approximation with a linear equation of state. The three-dimensional equations of motion are non-dimensionalised using the (dimensional) initial magnitudes of the streamwise velocity

![]() $U_{0}$

and buoyancy

$U_{0}$

and buoyancy

![]() $B_{0}$

, as well as the shear layer half-depth

$B_{0}$

, as well as the shear layer half-depth

![]() $d_{0}$

, as shown in figure 1. Using the advective time scale

$d_{0}$

, as shown in figure 1. Using the advective time scale

![]() $\tau _{\textit{ad}v} := d_{0} / U_{0}$

and the appropriate characteristic pressure scale

$\tau _{\textit{ad}v} := d_{0} / U_{0}$

and the appropriate characteristic pressure scale

![]() $p_{\textit{char}} := U_{0}^{2} \rho _{\textit{ref}}$

, where

$p_{\textit{char}} := U_{0}^{2} \rho _{\textit{ref}}$

, where

![]() $\rho_{ref}$

is a reference density, non-dimensional variables (marked here with a tilde) can be related to the dimensional variables as follows:

$\rho_{ref}$

is a reference density, non-dimensional variables (marked here with a tilde) can be related to the dimensional variables as follows:

Henceforth, we focus on non-dimensional variables, and so drop the tildes from all variables.

As a consequence, the non-dimensional governing equations are

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}$

,

$\boldsymbol{u}$

,

![]() $b$

and

$b$

and

![]() $p$

represent the velocity, buoyancy and modified pressure field, respectively. The precise form of the volumetric forcing terms

$p$

represent the velocity, buoyancy and modified pressure field, respectively. The precise form of the volumetric forcing terms

![]() $f_{u}$

and

$f_{u}$

and

![]() $f_{b}$

will be defined below. The buoyancy

$f_{b}$

will be defined below. The buoyancy

![]() $b := - \rho ^{\prime } g / \rho _{\textit{ref}}$

, where

$b := - \rho ^{\prime } g / \rho _{\textit{ref}}$

, where

![]() $g$

is the acceleration due to gravity, corresponds to the negative of the reduced gravity, so

$g$

is the acceleration due to gravity, corresponds to the negative of the reduced gravity, so

![]() $\rho '$

is the deviation from

$\rho '$

is the deviation from

![]() $\rho _{\textit{ref}}$

. Three non-dimensional parameters naturally emerge from this scaling: the Prandtl number, the initial bulk Reynolds number and the initial bulk Richardson number,

$\rho _{\textit{ref}}$

. Three non-dimensional parameters naturally emerge from this scaling: the Prandtl number, the initial bulk Reynolds number and the initial bulk Richardson number,

respectively, where

![]() $\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity and

$\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity and

![]() $\kappa$

is the buoyancy diffusivity. We restrict our attention to statically stable situations where

$\kappa$

is the buoyancy diffusivity. We restrict our attention to statically stable situations where

![]() $\textit{Ri}_{0} \gt 0$

.

$\textit{Ri}_{0} \gt 0$

.

The volumetric forcing terms

![]() $f_{u}$

and

$f_{u}$

and

![]() $f_{b}$

in (2.3) and (2.4) are a crucial aspect of our configuration. Following Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Caulfield and Taylor2021), we consider

$f_{b}$

in (2.3) and (2.4) are a crucial aspect of our configuration. Following Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Caulfield and Taylor2021), we consider

where

![]() $t_{{r}}$

is the response time while

$t_{{r}}$

is the response time while

![]() $u_{x, 0}$

and

$u_{x, 0}$

and

![]() $b_{0}$

represent the initial streamwise velocity and buoyancy base profiles to which the flow relaxes back under the effect of the forcing, at least in principle. In this context,

$b_{0}$

represent the initial streamwise velocity and buoyancy base profiles to which the flow relaxes back under the effect of the forcing, at least in principle. In this context,

![]() ${R_{0}} := d_{0} / \delta _{0}$

defines the ratio of initial interface half-depths (i.e.

${R_{0}} := d_{0} / \delta _{0}$

defines the ratio of initial interface half-depths (i.e.

![]() $\delta _{0}$

represents the dimensional initial buoyancy interface half-depth) with

$\delta _{0}$

represents the dimensional initial buoyancy interface half-depth) with

![]() ${R_{0}} = \sqrt {{\textit{Pr}}}$

following the diffusive arguments presented by Smyth, Klaassen & Peltier (Reference Smyth, Klaassen and Peltier1988). In essence, these forcing terms are idealised models of geophysically relevant processes (see again our introduction) that tend to restore the initial profiles

${R_{0}} = \sqrt {{\textit{Pr}}}$

following the diffusive arguments presented by Smyth, Klaassen & Peltier (Reference Smyth, Klaassen and Peltier1988). In essence, these forcing terms are idealised models of geophysically relevant processes (see again our introduction) that tend to restore the initial profiles

![]() $u_{x, 0}$

and

$u_{x, 0}$

and

![]() $b_{0}$

, and thus sustain turbulence over arbitrarily long times. In this context, we stress that the response time

$b_{0}$

, and thus sustain turbulence over arbitrarily long times. In this context, we stress that the response time

![]() $t_{{r}}$

quantifies the relative strength (or rather weakness) of these superposed processes. While

$t_{{r}}$

quantifies the relative strength (or rather weakness) of these superposed processes. While

![]() ${t_{{r}}} \rightarrow 0$

implies vigorously enforcing the sharp initial profiles,

${t_{{r}}} \rightarrow 0$

implies vigorously enforcing the sharp initial profiles,

![]() ${t_{{r}}} \rightarrow \infty$

corresponds to the disappearance of the forcing. As shown by Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Caulfield and Taylor2021), the broad sweetspot – to allow for sustained turbulence without prescribing a significant signal of the forcing – lies in between and tends to preserve the primary instability associated with the underlying base profiles. Finally, we remark that, although the included base profiles are time-independent, the resulting rate of momentum or buoyancy injection is typically not constant in space or time.

${t_{{r}}} \rightarrow \infty$

corresponds to the disappearance of the forcing. As shown by Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Caulfield and Taylor2021), the broad sweetspot – to allow for sustained turbulence without prescribing a significant signal of the forcing – lies in between and tends to preserve the primary instability associated with the underlying base profiles. Finally, we remark that, although the included base profiles are time-independent, the resulting rate of momentum or buoyancy injection is typically not constant in space or time.

Hence, the governing (2.2)–(2.4) are fully specified via four control parameters:

![]() $\textit{Pr}$

,

$\textit{Pr}$

,

![]() $\textit{Re}_{0}$

,

$\textit{Re}_{0}$

,

![]() $\textit{Ri}_{0}$

and

$\textit{Ri}_{0}$

and

![]() $t_{{r}}$

.

$t_{{r}}$

.

2.2. Domain, boundary and initial conditions and numerical code

As indicated by figure 1, the volume

![]() $V := L_{x} \times L_{\!y} \times L_{z}$

of the numerical domain is the product of the streamwise, spanwise and vertical extents

$V := L_{x} \times L_{\!y} \times L_{z}$

of the numerical domain is the product of the streamwise, spanwise and vertical extents

![]() $L_{x}$

,

$L_{x}$

,

![]() $L_{\!y}$

and

$L_{\!y}$

and

![]() $L_{z}$

, respectively. Both the midpoint of the shear layer and the midpoint of the buoyancy distribution are located at midplane,

$L_{z}$

, respectively. Both the midpoint of the shear layer and the midpoint of the buoyancy distribution are located at midplane,

![]() $z = 0$

, with a horizontal cross-section

$z = 0$

, with a horizontal cross-section

![]() $A := L_{x} \times L_{\!y}$

. We consider a horizontally periodic domain where any quantity

$A := L_{x} \times L_{\!y}$

. We consider a horizontally periodic domain where any quantity

Additionally, we apply free-slip and no-flux boundary conditions at the top and bottom, so

Our initial condition is given by

The random fluctuations

![]() $- 10^{-3} \leqslant \varUpsilon ( \boldsymbol{x} ) \leqslant 10^{-3}$

‘seed’ the development of primary instabilities.

$- 10^{-3} \leqslant \varUpsilon ( \boldsymbol{x} ) \leqslant 10^{-3}$

‘seed’ the development of primary instabilities.

We solve the coupled governing equations (2.2)–(2.4), subject to these boundary and initial conditions (2.8)–(2.10), using the GPU-accelerated spectral element solver NekRS (Fischer Reference Fischer1997; Scheel, Emran & Schumacher Reference Scheel, Emran and Schumacher2013; Fischer et al. Reference Fischer2022). As the spatial resolution of spectral element methods is determined by the combination of the number of spectral elements

![]() $N_{{e}} = N_{{e}, x} \times N_{{e}, y} \times N_{{e}, z}$

and polynomial order

$N_{{e}} = N_{{e}, x} \times N_{{e}, y} \times N_{{e}, z}$

and polynomial order

![]() $N$

of the spectral expansion within each element (Deville, Fischer & Mund Reference Deville, Fischer and Mund2002; Vieweg Reference Vieweg2023), such methods can – as shown in more detail in Appendix A – accommodate different required spatial resolutions across the domain and are thus well suited to resolving shear flows efficiently. This is particularly important given degrees of freedom of up to

$N$

of the spectral expansion within each element (Deville, Fischer & Mund Reference Deville, Fischer and Mund2002; Vieweg Reference Vieweg2023), such methods can – as shown in more detail in Appendix A – accommodate different required spatial resolutions across the domain and are thus well suited to resolving shear flows efficiently. This is particularly important given degrees of freedom of up to

![]() $N_{\textit{dof}} \approx 3 N_{{e}} N^{3} \sim \mathcal{O} ( 10^{9} )$

and the lengthy flow evolution in our present study.

$N_{\textit{dof}} \approx 3 N_{{e}} N^{3} \sim \mathcal{O} ( 10^{9} )$

and the lengthy flow evolution in our present study.

3. Results

This study considers forced stratified shear flows at

![]() ${\textit{Pr}} = 1$

,

${\textit{Pr}} = 1$

,

![]() $\textit{Re}_{0} = 50$

,

$\textit{Re}_{0} = 50$

,

![]() $\textit{Ri}_{0} = 0.0125$

and

$\textit{Ri}_{0} = 0.0125$

and

![]() ${t_{{r}}} = 100$

in domains of

${t_{{r}}} = 100$

in domains of

![]() $L_{z} = 48$

. As will be shown in more detail in § 3.2, these parameters are associated with the minimum value of the initial gradient Richardson number

$L_{z} = 48$

. As will be shown in more detail in § 3.2, these parameters are associated with the minimum value of the initial gradient Richardson number

![]() $\textit{Ri}_{{g,0}} ( z = 0 ) = \textit{Ri}_{0} {R_{0}}$

, which is sufficiently small to enable the development of primary KHI. We investigate and quantify the emergent dynamics of the flow while varying the horizontal extents of the domain,

$\textit{Ri}_{{g,0}} ( z = 0 ) = \textit{Ri}_{0} {R_{0}}$

, which is sufficiently small to enable the development of primary KHI. We investigate and quantify the emergent dynamics of the flow while varying the horizontal extents of the domain,

![]() $L_{x}$

and

$L_{x}$

and

![]() $L_{\!y}$

. Normally, we consider domains of square horizontal cross-section with

$L_{\!y}$

. Normally, we consider domains of square horizontal cross-section with

![]() $L_{{h}} \equiv L_{x} = L_{\!y}$

ranging from

$L_{{h}} \equiv L_{x} = L_{\!y}$

ranging from

![]() $16$

to

$16$

to

![]() $512$

. Table 1 summarises all our considered domains.

$512$

. Table 1 summarises all our considered domains.

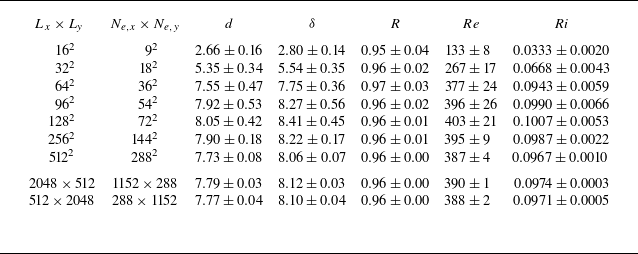

Table 1. Simulation parameters. The Prandtl number

![]() ${\textit{Pr}} = 1$

, initial bulk Reynolds number

${\textit{Pr}} = 1$

, initial bulk Reynolds number

![]() $\textit{Re}_{0} = 50$

, initial bulk Richardson number

$\textit{Re}_{0} = 50$

, initial bulk Richardson number

![]() $\textit{Ri}_{0} = 0.0125$

, response time

$\textit{Ri}_{0} = 0.0125$

, response time

![]() ${t_{{r}}} = 100$

and initial ratio of interface half-depths

${t_{{r}}} = 100$

and initial ratio of interface half-depths

![]() ${R_{0}} = 1$

in a horizontally periodic domain. In the vertical direction, the domain has an aspect ratio

${R_{0}} = 1$

in a horizontally periodic domain. In the vertical direction, the domain has an aspect ratio

![]() $L_{z} = 48$

spanned by

$L_{z} = 48$

spanned by

![]() $N_{{e}, z} = 18$

non-uniformly distributed spectral elements (see Appendix A for more details) together with free-slip and no-flux boundary conditions for the velocity and buoyancy field, respectively. The polynomial order

$N_{{e}, z} = 18$

non-uniformly distributed spectral elements (see Appendix A for more details) together with free-slip and no-flux boundary conditions for the velocity and buoyancy field, respectively. The polynomial order

![]() $N = 6$

. Although the total evolution or run time of each flow

$N = 6$

. Although the total evolution or run time of each flow

![]() $t_{\textit{e}v\textit{o}} = 5\,040$

, this work focuses on the statistically stationary dynamics during the last

$t_{\textit{e}v\textit{o}} = 5\,040$

, this work focuses on the statistically stationary dynamics during the last

![]() $\Delta t = 3,000$

only. For each simulation, this table lists the horizontal cross-sectional areas

$\Delta t = 3,000$

only. For each simulation, this table lists the horizontal cross-sectional areas

![]() $L_{x} \times L_{\!y}$

and corresponding numbers of uniformly distributed spectral elements

$L_{x} \times L_{\!y}$

and corresponding numbers of uniformly distributed spectral elements

![]() $N_{{e}, x} \times N_{{e}, y}$

. Moreover, we include the final emergent shear layer half-depth

$N_{{e}, x} \times N_{{e}, y}$

. Moreover, we include the final emergent shear layer half-depth

![]() $d$

of the streamwise velocity field as well as the buoyancy interface half-depth

$d$

of the streamwise velocity field as well as the buoyancy interface half-depth

![]() $\delta$

, their ratio

$\delta$

, their ratio

![]() $R$

, the bulk Reynolds number

$R$

, the bulk Reynolds number

![]() ${Re}$

, as well as the bulk Richardson number

${Re}$

, as well as the bulk Richardson number

![]() ${Ri}$

, listing both their temporal means and standard deviations.

${Ri}$

, listing both their temporal means and standard deviations.

3.1. Typical evolution of a forced stratified shear flow

Figure 2. Temporal evolution of forced, stratified shear flows. (a–e) The flow is prone to a primary KHI, leading eventually to ‘overturning billows’ and streamwise mergers. A continuous forcing sustains the induced turbulence for arbitrarily long times. During this evolution of the flow, ( f–h) the interface broadens before reaching a statistically stationary depth. Note that, for this relatively small

![]() $\textit{Re}_{0}$

, as shown in (g), molecular diffusion of the shear layer and density interface dominates the development of the primary instability until the depths of the shear layer and density interface have approximately doubled. In this figure,

$\textit{Re}_{0}$

, as shown in (g), molecular diffusion of the shear layer and density interface dominates the development of the primary instability until the depths of the shear layer and density interface have approximately doubled. In this figure,

![]() $L_{{h}} = 128$

while panels (a–e) visualise

$L_{{h}} = 128$

while panels (a–e) visualise

![]() $b ( x, y = 0, z, t )$

with the colour bar matching figure 6(l,p).

$b ( x, y = 0, z, t )$

with the colour bar matching figure 6(l,p).

We first consider the evolution of a typical flow in a domain with a horizontal extent of

![]() $L_{{h}} = 128$

. Figure 2(a–e) shows snapshots of the instantaneous buoyancy field

$L_{{h}} = 128$

. Figure 2(a–e) shows snapshots of the instantaneous buoyancy field

![]() $b ( x, y = 0, z, t )$

in vertical slices normal to the spanwise direction. At early times, the flow is prone to a primary KHI which, driven by the vertical shear, develops into a train of KH billows (panel (c)) that merge subsequently (panel (d)). These primary billows break down, and the buoyancy interface broadens (panel (f)). Note that we use

$b ( x, y = 0, z, t )$

in vertical slices normal to the spanwise direction. At early times, the flow is prone to a primary KHI which, driven by the vertical shear, develops into a train of KH billows (panel (c)) that merge subsequently (panel (d)). These primary billows break down, and the buoyancy interface broadens (panel (f)). Note that we use

![]() $\langle f \rangle _{\varPhi }$

to denote the average value of some flow variable

$\langle f \rangle _{\varPhi }$

to denote the average value of some flow variable

![]() $f$

computed over

$f$

computed over

![]() $\varPhi$

, where the averaging domain

$\varPhi$

, where the averaging domain

![]() $\varPhi$

may be a combination of spatial and temporal dimensions. Here, time averages cover the flows’ last

$\varPhi$

may be a combination of spatial and temporal dimensions. Here, time averages cover the flows’ last

![]() $\Delta t = 3\,000$

, i.e. the time interval associated with the statistically stationary regime of primary interest.

$\Delta t = 3\,000$

, i.e. the time interval associated with the statistically stationary regime of primary interest.

If this was an initial-value problem, turbulence would die out shortly after

![]() $t=270$

due to the combined (and inter-related) effects of enhanced dissipation and broadening of both the shear layer as well as the density interface, eventually leading to an increased (and, according to the so-called ‘Miles–Howard criterion’ (Miles Reference Miles1961; Howard Reference Howard1961), indeed linearly stable) minimum gradient Richardson number. However, volumetric forcing sustains the induced turbulence over arbitrarily long times. This is underlined by panel (e), which shows a snapshot during this late statistically steady turbulent state of the flow. Here, we focus largely on this late, statistically stationary dynamics.

$t=270$

due to the combined (and inter-related) effects of enhanced dissipation and broadening of both the shear layer as well as the density interface, eventually leading to an increased (and, according to the so-called ‘Miles–Howard criterion’ (Miles Reference Miles1961; Howard Reference Howard1961), indeed linearly stable) minimum gradient Richardson number. However, volumetric forcing sustains the induced turbulence over arbitrarily long times. This is underlined by panel (e), which shows a snapshot during this late statistically steady turbulent state of the flow. Here, we focus largely on this late, statistically stationary dynamics.

Across the evolution of the flow, we quantify the associated broadening of the shear layer and buoyancy interface via

respectively, using the approach proposed by Smyth & Moum (Reference Smyth and Moum2000). Together with the initial profiles defined in equations (2.6) and (2.7), these functions yield

![]() ${d} ( t = 0 ) = 1$

and

${d} ( t = 0 ) = 1$

and

![]() $\delta ( t = 0 ) = 1 / {R_{0}}$

(as these non-dimensional lengths

$\delta ( t = 0 ) = 1 / {R_{0}}$

(as these non-dimensional lengths

![]() $\left \{ d, \delta \right \}$

are measured in units of

$\left \{ d, \delta \right \}$

are measured in units of

![]() $d_{0}$

, see again equation (2.1)). Similarly, the time-dependent ratio of interface depths

$d_{0}$

, see again equation (2.1)). Similarly, the time-dependent ratio of interface depths

![]() $R ( t ) := d / \delta$

with

$R ( t ) := d / \delta$

with

![]() $R ( t = 0 ) = {R_{0}}$

. Figure 2(g,h) highlights that both

$R ( t = 0 ) = {R_{0}}$

. Figure 2(g,h) highlights that both

![]() $d$

and

$d$

and

![]() $\delta$

converge after an initial transient of length

$\delta$

converge after an initial transient of length

![]() $\lesssim 10^{3} \tau _{\textit{ad}v}$

to statistically stationary values

$\lesssim 10^{3} \tau _{\textit{ad}v}$

to statistically stationary values

![]() $\left \{ d, \delta \right \} \gg 1$

. In other words, the interfaces have deepened significantly and, remarkably, reached a finite value characterised by a balance between the ongoing forcing (attempting to relax the interfaces back to their original depths) and mixing (tending to deepen the interfaces). We establish the independence of this finite value from the extent of the domain in the subsequent sub-sections and hypothesise a physical reason for this convergence in § 4. Consistently with the fact that the flow remains ‘weakly’ stratified, the ratio

$\left \{ d, \delta \right \} \gg 1$

. In other words, the interfaces have deepened significantly and, remarkably, reached a finite value characterised by a balance between the ongoing forcing (attempting to relax the interfaces back to their original depths) and mixing (tending to deepen the interfaces). We establish the independence of this finite value from the extent of the domain in the subsequent sub-sections and hypothesise a physical reason for this convergence in § 4. Consistently with the fact that the flow remains ‘weakly’ stratified, the ratio

![]() $R \approx 1$

at late times. Here, ‘weakly stratified’ is meant in the specific sense that the turbulent diffusivity of buoyancy closely follows the turbulent diffusivity of the momentum. Equivalently, the turbulent Prandtl number is close to one, and so the buoyancy field is at least in some sense slaved to the velocity field and behaves like a passive scalar (Turner Reference Turner1973). Due to the particular form of the forcing, with shear continually being reinforced, it is also appropriate to consider this flow to be ‘shear dominated’ within the nomenclature of Mater & Venayagamoorthy (Reference Mater and Venayagamoorthy2014).

$R \approx 1$

at late times. Here, ‘weakly stratified’ is meant in the specific sense that the turbulent diffusivity of buoyancy closely follows the turbulent diffusivity of the momentum. Equivalently, the turbulent Prandtl number is close to one, and so the buoyancy field is at least in some sense slaved to the velocity field and behaves like a passive scalar (Turner Reference Turner1973). Due to the particular form of the forcing, with shear continually being reinforced, it is also appropriate to consider this flow to be ‘shear dominated’ within the nomenclature of Mater & Venayagamoorthy (Reference Mater and Venayagamoorthy2014).

We note in passing that, as highlighted in panel (g), the onset of the primary KHI (evidenced by the significant change in the rate of the growth of

![]() $d$

and

$d$

and

![]() $\delta$

around

$\delta$

around

![]() $t\simeq 150$

) appears only after a period of significant diffusive deepening of both the shear layer and the buoyancy interface. As the shear layer half-depth

$t\simeq 150$

) appears only after a period of significant diffusive deepening of both the shear layer and the buoyancy interface. As the shear layer half-depth

![]() $d$

approximately doubles during this initial period of time, the onset of the primary instability triggers a significantly larger wavelength. In other words, the characteristic scales of the delayed KHI are set relative to

$d$

approximately doubles during this initial period of time, the onset of the primary instability triggers a significantly larger wavelength. In other words, the characteristic scales of the delayed KHI are set relative to

![]() $d$

rather than

$d$

rather than

![]() $d_{0}$

. An investigation of this interesting early-time interaction between diffusion and instability onset is beyond the scope of this paper but undoubtedly worthy of further, more detailed consideration.

$d_{0}$

. An investigation of this interesting early-time interaction between diffusion and instability onset is beyond the scope of this paper but undoubtedly worthy of further, more detailed consideration.

Having reached the final, statistically stationary state, the above definition of

![]() ${d} ( t )$

enables the computation of associated time-dependent values of the bulk Reynolds and Richardson number via

${d} ( t )$

enables the computation of associated time-dependent values of the bulk Reynolds and Richardson number via

with, again,

![]() ${{Re}} ( t = 0 ) = \textit{Re}_{0}$

and

${{Re}} ( t = 0 ) = \textit{Re}_{0}$

and

![]() ${Ri} ( t = 0 ) = \textit{Ri}_{0}$

. We stress that, since

${Ri} ( t = 0 ) = \textit{Ri}_{0}$

. We stress that, since

![]() $\langle d \rangle _{t} \approx 8 \gg 1$

at our late times of interest, the final flow has an effective temporal average

$\langle d \rangle _{t} \approx 8 \gg 1$

at our late times of interest, the final flow has an effective temporal average

![]() $\langle {{Re}} \rangle _{t} \approx 400 \gg \textit{Re}_{0}$

and has, thus, become much more turbulent than what one might have expected from the relatively small initial value of

$\langle {{Re}} \rangle _{t} \approx 400 \gg \textit{Re}_{0}$

and has, thus, become much more turbulent than what one might have expected from the relatively small initial value of

![]() $\textit{Re}_{0}=50$

.

$\textit{Re}_{0}=50$

.

Table 1 lists the temporal averages and standard deviations of

![]() $d$

,

$d$

,

![]() $\delta$

,

$\delta$

,

![]() $R$

,

$R$

,

![]() ${Re}$

and

${Re}$

and

![]() ${Ri}$

during the late statistically stationary dynamics of all our simulations. We discuss their trends with respect to the horizontal domain size

${Ri}$

during the late statistically stationary dynamics of all our simulations. We discuss their trends with respect to the horizontal domain size

![]() $L_{{h}}$

in § 3.3.

$L_{{h}}$

in § 3.3.

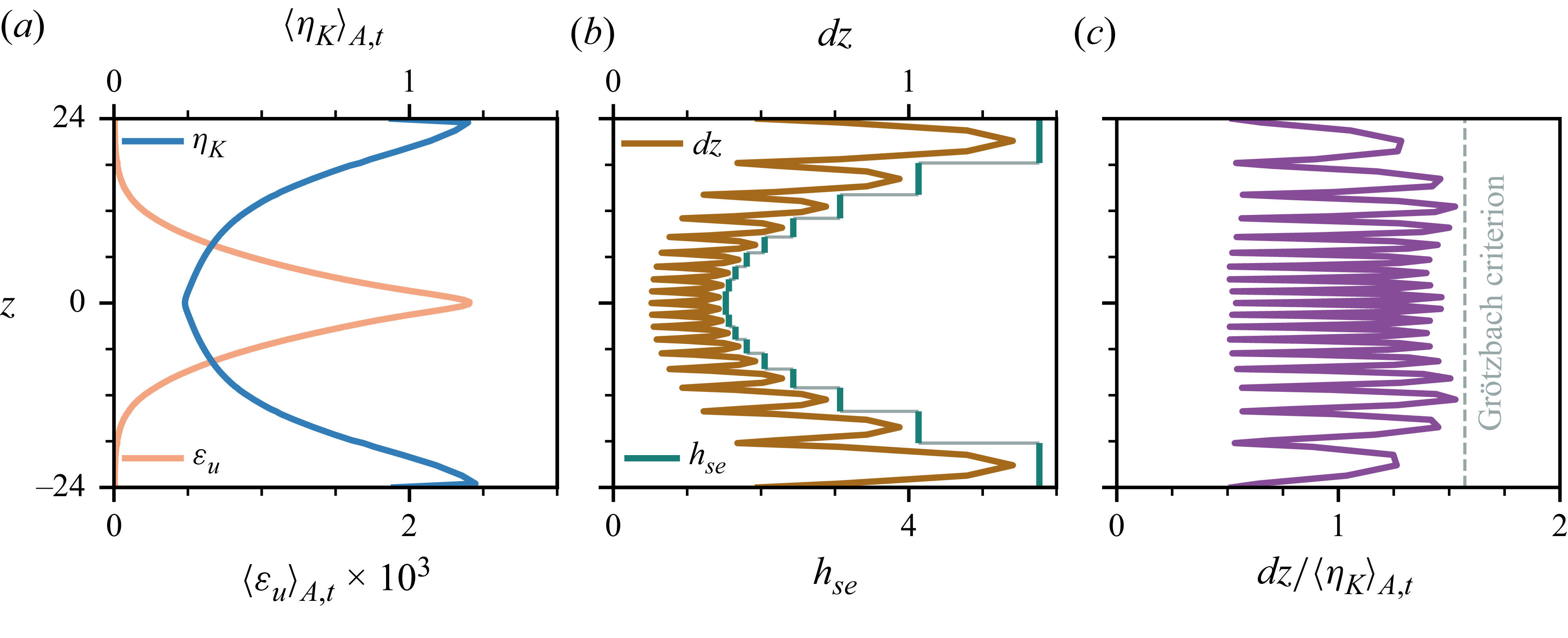

3.2. Sustained turbulent interactions between the two layers

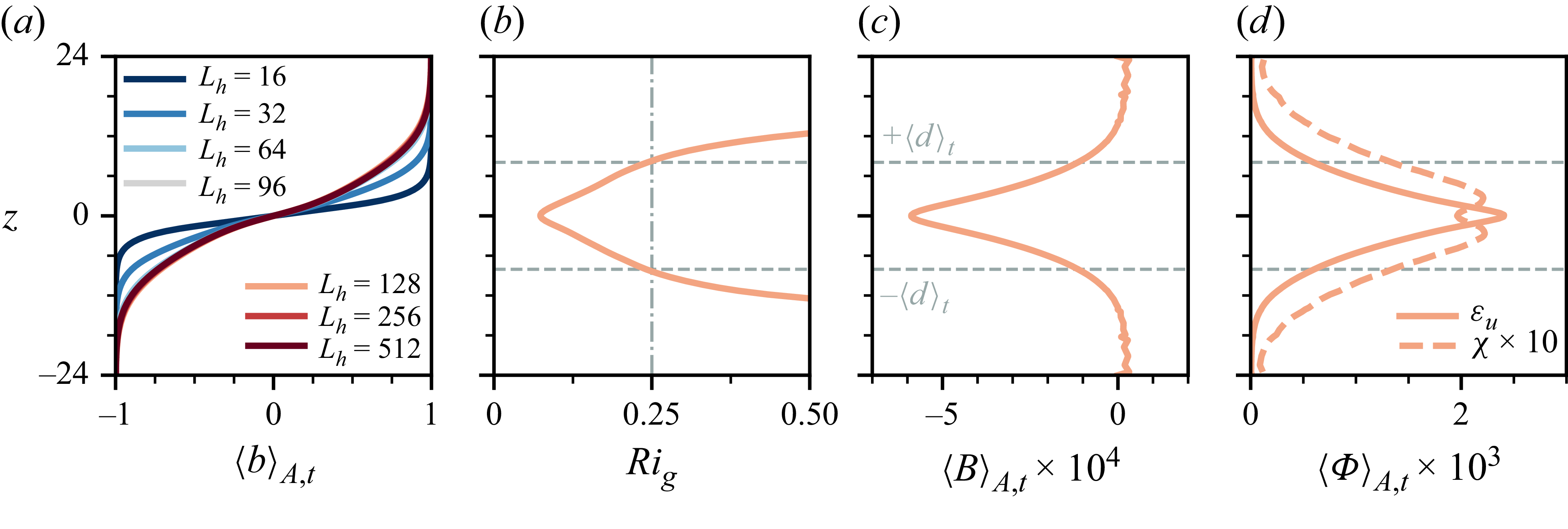

Figure 3. Sustained turbulent interactions. (a) Despite statistical stationarity, the deepening of the density interface can be affected by the horizontal extent of the domain

![]() $L_{{h}} \equiv L_{x} = L_{\!y}$

before it converges eventually. This deepening tends to stabilise the emergent flow, resulting in a significantly increased minimum value of

$L_{{h}} \equiv L_{x} = L_{\!y}$

before it converges eventually. This deepening tends to stabilise the emergent flow, resulting in a significantly increased minimum value of

![]() $0.074$

of (b) the average late

$0.074$

of (b) the average late

![]() $\textit{Ri}_{{g}}$

. Nevertheless, we find

$\textit{Ri}_{{g}}$

. Nevertheless, we find

![]() $\textit{Ri}_{{g}} \leqslant 0.25$

(with this canonical value being marked with a vertical line) throughout the turbulent ‘mixing zone’. The resulting associated mixing in this zone is underlined by high amplitudes in (c) the stabilising vertical buoyancy advection (i.e. the buoyancy flux)

$\textit{Ri}_{{g}} \leqslant 0.25$

(with this canonical value being marked with a vertical line) throughout the turbulent ‘mixing zone’. The resulting associated mixing in this zone is underlined by high amplitudes in (c) the stabilising vertical buoyancy advection (i.e. the buoyancy flux)

![]() $B$

and (d) the dissipation rates of kinetic energy and scaled buoyancy variance,

$B$

and (d) the dissipation rates of kinetic energy and scaled buoyancy variance,

![]() $\varepsilon _{u}$

and

$\varepsilon _{u}$

and

![]() $\chi$

.

$\chi$

.

Even though a continuous forcing allows the existence of a statistically stationary regime, the associated sustained turbulent interactions between the fluid regions above and below the shear layer may yet be impacted by the extent of the domain. In figure 3(a) we plot the mean vertical buoyancy profiles

![]() $\langle b \rangle _{A, t}$

associated with the late-time dynamics of the forced stratified shear flow. We find that these profiles depend strongly on the horizontal extent

$\langle b \rangle _{A, t}$

associated with the late-time dynamics of the forced stratified shear flow. We find that these profiles depend strongly on the horizontal extent

![]() $L_{{h}}$

of the domain. Although

$L_{{h}}$

of the domain. Although

![]() $L_{{h}} = 16 \gg 1$

even for our smallest domain, the interface deepens for increasing

$L_{{h}} = 16 \gg 1$

even for our smallest domain, the interface deepens for increasing

![]() $L_{{h}}$

and a convergence seems to be reached for

$L_{{h}}$

and a convergence seems to be reached for

![]() $L_{{h}} \gtrsim 64$

only. This suggests that the vertical stirring and resultant mixing of buoyancy strongly depends on the horizontal extent of the domain.

$L_{{h}} \gtrsim 64$

only. This suggests that the vertical stirring and resultant mixing of buoyancy strongly depends on the horizontal extent of the domain.

This observed deepening of the buoyancy interface is accompanied by a deepening of the shear layer, both affecting in turn the gradient Richardson number

\begin{equation} \textit{Ri}_{{g}} (z) := \frac {\langle N^{2} \rangle _{A, t}}{\langle S \rangle _{A, t}^{2}} \equiv \left ( \frac {t_{{S}}}{t_{{N}}} \right )^{2} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \textit{Ri}_{{g}} (z) := \frac {\langle N^{2} \rangle _{A, t}}{\langle S \rangle _{A, t}^{2}} \equiv \left ( \frac {t_{{S}}}{t_{{N}}} \right )^{2} \end{equation}

via the buoyancy frequency (for which averaging is typically associated with

![]() $\partial b / \partial z$

) and vertical shear

$\partial b / \partial z$

) and vertical shear

respectively. We remark that it is also possible to associate the initial profiles from equations (2.6) and (2.7) with an initial gradient Richardson number

![]() $\textit{Ri}_{{g}} ( z, t = 0 ) = \textit{Ri}_{{g,0}} := \textit{Ri}_{0} ( \partial b_{0} / \partial z ) / ( \partial u_{x,0} / \partial z )^{2}$

. As shown in figure 3(b), the minimum value of

$\textit{Ri}_{{g}} ( z, t = 0 ) = \textit{Ri}_{{g,0}} := \textit{Ri}_{0} ( \partial b_{0} / \partial z ) / ( \partial u_{x,0} / \partial z )^{2}$

. As shown in figure 3(b), the minimum value of

![]() $\textit{Ri}_{{g}}$

has significantly increased from

$\textit{Ri}_{{g}}$

has significantly increased from

![]() $\textit{Ri}_{{g,0}} ( z = 0 ) = 0.0125$

to

$\textit{Ri}_{{g,0}} ( z = 0 ) = 0.0125$

to

![]() $\textit{Ri}_{{g}} ( z = 0 ) \approx 0.074$

provided

$\textit{Ri}_{{g}} ( z = 0 ) \approx 0.074$

provided

![]() $L_{{h}} = 128$

. Note that, due to the square in the denominator of the definition, the reduction of shear overpowers the simultaneous reduction of buoyancy stratification. As indicated on the right of equation (3.3),

$L_{{h}} = 128$

. Note that, due to the square in the denominator of the definition, the reduction of shear overpowers the simultaneous reduction of buoyancy stratification. As indicated on the right of equation (3.3),

![]() $\textit{Ri}_{{g}}$

can also be interpreted as a ratio of time scales associated with the average shear and stratification, an observation we will discuss in detail in § 4.

$\textit{Ri}_{{g}}$

can also be interpreted as a ratio of time scales associated with the average shear and stratification, an observation we will discuss in detail in § 4.

From this panel (b), it is also apparent that

![]() $\textit{Ri}_{{g}} \leqslant 0.25$

within the region

$\textit{Ri}_{{g}} \leqslant 0.25$

within the region

![]() $ - \langle d \rangle _{t} \leqslant z \leqslant \langle d \rangle _{t}$

. Although the flow is undoubtedly turbulent – and so the Miles–Howard criterion (Miles Reference Miles1961; Howard Reference Howard1961) of (steady) linear inviscid stability theory is definitely not applicable –, such relatively small values of

$ - \langle d \rangle _{t} \leqslant z \leqslant \langle d \rangle _{t}$

. Although the flow is undoubtedly turbulent – and so the Miles–Howard criterion (Miles Reference Miles1961; Howard Reference Howard1961) of (steady) linear inviscid stability theory is definitely not applicable –, such relatively small values of

![]() $\textit{Ri}_{{g}}$

are necessary for turbulence to survive and so we refer to this zone as the turbulent ‘mixing zone’.

$\textit{Ri}_{{g}}$

are necessary for turbulence to survive and so we refer to this zone as the turbulent ‘mixing zone’.

Indeed, this nomenclature is also strongly justified (as shown in figure 3 c,d) by considering the vertical buoyancy advection (frequently called the buoyancy flux)

as well as the dissipation rates of kinetic energy

![]() $\varepsilon _{u}$

and scaled buoyancy variance

$\varepsilon _{u}$

and scaled buoyancy variance

![]() $\chi$

$\chi$

respectively, which naturally emerge in the evolution equations for kinetic energy and scaled buoyancy variance (see for example the review of Caulfield (Reference Caulfield2021) for a derivation). Here,

![]() $\boldsymbol{S}$

represents the strain rate tensor and

$\boldsymbol{S}$

represents the strain rate tensor and

![]() $\varepsilon _{b}$

the (unscaled) buoyancy variance dissipation rate. Note that the scaling via

$\varepsilon _{b}$

the (unscaled) buoyancy variance dissipation rate. Note that the scaling via

![]() $\langle N^{2} \rangle _{A, t}$

results in identical physical units for the associated dimensional dissipation rates. We emphasise this point by the comparison

$\langle N^{2} \rangle _{A, t}$

results in identical physical units for the associated dimensional dissipation rates. We emphasise this point by the comparison

\begin{align} \varepsilon _{b} &= \frac {{B_{0}}^{2} U_{0}}{d_{0}} \, \tilde {\varepsilon }_{b} = \frac {U_{0}^{5}}{d_{0}^{3}} \textit{Ri}_{0}^{2} \, \tilde {\varepsilon }_{b}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \varepsilon _{b} &= \frac {{B_{0}}^{2} U_{0}}{d_{0}} \, \tilde {\varepsilon }_{b} = \frac {U_{0}^{5}}{d_{0}^{3}} \textit{Ri}_{0}^{2} \, \tilde {\varepsilon }_{b}, \end{align}

where we have, for improved clarity, re-introduced tildes for non-dimensional quantities in the above three equations only. This property of identical physical units is particularly helpful when studying the exchange of kinetic and potential energy, as buoyancy variance is closely related to the concept of ‘available potential energy’ as originally introduced by Lorenz (Reference Lorenz1955) and further developed by Winters et al. (Reference Winters, Lombard, Riley and D’Asaro1995); see for example the review of Caulfield (Reference Caulfield2021) for further discussion.

As shown in panels (c–d) of figure 3, all of these quantities exhibit pronounced peaks close to the midplane. However, while the vertical buoyancy advection

![]() $B$

introduces a macroscopic stirring that is generally reversible, it leads to irreversible dissipation via both

$B$

introduces a macroscopic stirring that is generally reversible, it leads to irreversible dissipation via both

![]() $\varepsilon _{u}$

and

$\varepsilon _{u}$

and

![]() $\varepsilon _{b}$

due to the inherent coupling of

$\varepsilon _{b}$

due to the inherent coupling of

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}$

and

$\boldsymbol{u}$

and

![]() $b$

. As

$b$

. As

![]() $\langle B \rangle _{V, t} \lt 0$

, this stirring comes with an overall stabilising effect on the configuration. Furthermore, although enhanced values of

$\langle B \rangle _{V, t} \lt 0$

, this stirring comes with an overall stabilising effect on the configuration. Furthermore, although enhanced values of

![]() $\varepsilon _{u}$

and

$\varepsilon _{u}$

and

![]() $\chi$

extend beyond the mixing zone, it is clear that this mixing zone contains the vast majority of the enhanced dissipation in this regime.

$\chi$

extend beyond the mixing zone, it is clear that this mixing zone contains the vast majority of the enhanced dissipation in this regime.

Hence, the emergent turbulent shear half-depth

![]() $\langle d \rangle _{t}$

– as defined in equation (3.1) – represents an appropriate measure of the mixing zone as a region of strong interactions between the two fluid layers. We discuss further implications of these vertical profiles (including for values of the average flux coefficient) in more detail in § 4.

$\langle d \rangle _{t}$

– as defined in equation (3.1) – represents an appropriate measure of the mixing zone as a region of strong interactions between the two fluid layers. We discuss further implications of these vertical profiles (including for values of the average flux coefficient) in more detail in § 4.

3.3. Convergence of vertical stirring, dissipation and mixing for extended domains

Figure 4. Impact of the horizontal extent of the domain on the mixing. The flow topology – comprising the (a) interface (half-) depths, (b) final emergent (bulk) Reynolds number and Richardson number, as well as averages across the midplane and across the entire mixing zone of (c) gradient Richardson number, (d) buoyancy flux, (e) kinetic energy dissipation and ( f) buoyancy variance dissipation – only converges for horizontally extended domains,

![]() $L_{{h}} \gtrsim L_{\textit{h, crit}} = 96$

. Vertical solid lines indicate the temporal standard deviation. All panels share the same abscissa.

$L_{{h}} \gtrsim L_{\textit{h, crit}} = 96$

. Vertical solid lines indicate the temporal standard deviation. All panels share the same abscissa.

After having introduced important quantities related to the vertical interaction of the velocity and buoyancy field in the previous § 3.1 and § 3.2, in figure 4 we plot their variation as a function of

![]() $L_{{h}}$

. Underlining the conclusions from figure 3(a), figure 4(a) shows that the depths of the streamwise velocity interfaces (i.e. the shear layers) and the buoyancy interfaces indeed converge for sufficiently extended horizontal domains. As the parameters

$L_{{h}}$

. Underlining the conclusions from figure 3(a), figure 4(a) shows that the depths of the streamwise velocity interfaces (i.e. the shear layers) and the buoyancy interfaces indeed converge for sufficiently extended horizontal domains. As the parameters

![]() $\left \{ {{Re}}, {Ri} \right \} \propto d$

, they converge for extended domains, too, as shown in panel (b). Note that both are significantly increased from their initial values. Starting with panel (c), we plot spatio-temporal averages of various quantities where the spatial averages are performed either across the two-dimensional horizontal midplane or across the volume of the entire turbulent mixing zone. Unsurprisingly, given the convergence of the depth of the mixing zone, we observe similar convergence for the gradient Richardson number

$\left \{ {{Re}}, {Ri} \right \} \propto d$

, they converge for extended domains, too, as shown in panel (b). Note that both are significantly increased from their initial values. Starting with panel (c), we plot spatio-temporal averages of various quantities where the spatial averages are performed either across the two-dimensional horizontal midplane or across the volume of the entire turbulent mixing zone. Unsurprisingly, given the convergence of the depth of the mixing zone, we observe similar convergence for the gradient Richardson number

![]() $\textit{Ri}_{{g}}$

as well as the vertical stirring- and mixing-related quantities

$\textit{Ri}_{{g}}$

as well as the vertical stirring- and mixing-related quantities

![]() $B$

,

$B$

,

![]() $\varepsilon _{u}$

and

$\varepsilon _{u}$

and

![]() $\chi$

as shown in panels (c–f).

$\chi$

as shown in panels (c–f).

In summary, we find that the properties of the (predominantly vertical) stirring, dissipation and mixing actually depend strongly on the horizontal extent of the domain

![]() $L_{{h}}$

. However, the associated emergent vertical dynamics of the flow seems indeed to become independent of

$L_{{h}}$

. However, the associated emergent vertical dynamics of the flow seems indeed to become independent of

![]() $L_{{h}}$

once

$L_{{h}}$

once

![]() $L_{{h}} \gtrsim L_{\textit{h, crit}} = 96$

where

$L_{{h}} \gtrsim L_{\textit{h, crit}} = 96$

where

![]() $L_{\textit{h, crit}}$

is a critical extent of the domain.

$L_{\textit{h, crit}}$

is a critical extent of the domain.

Finally, as shown in figure 5, we remark that not only the mean values of of dissipation and mixing rates depend on

![]() $L_{{h}}$

, but also the general structure of their probability density functions (PDFs) depends on

$L_{{h}}$

, but also the general structure of their probability density functions (PDFs) depends on

![]() $L_{{h}}$

as well. Interestingly, we observe a pronounced scaling of the PDF of the (point-wise) local flux coefficient

$L_{{h}}$

as well. Interestingly, we observe a pronounced scaling of the PDF of the (point-wise) local flux coefficient

![]() $\varGamma _{\chi }$

– defined as

$\varGamma _{\chi }$

– defined as

and representing the local ratio between dissipation of scaled buoyancy variance and kinetic energy – for values

![]() $\varGamma _{\chi } \gtrsim 0.2$

, i.e. the canonical value proposed by Osborn (Reference Osborn1980), as indicated in panel (c). We return to a more conventional definition of a (in some sense) global flux coefficient – based on average rather than local quantities – in § 4.

$\varGamma _{\chi } \gtrsim 0.2$

, i.e. the canonical value proposed by Osborn (Reference Osborn1980), as indicated in panel (c). We return to a more conventional definition of a (in some sense) global flux coefficient – based on average rather than local quantities – in § 4.

Figure 5. Statistics of mixing properties at midplane. Statistical distributions of the (a) kinetic energy dissipation rate

![]() $\varepsilon _{u}$

, (b) scaled buoyancy variance dissipation rate

$\varepsilon _{u}$

, (b) scaled buoyancy variance dissipation rate

![]() $\chi$

and (c) local flux coefficient

$\chi$

and (c) local flux coefficient

![]() $\varGamma _{\chi }$

are affected by insufficient extents of the domain but converge eventually. The grey dashed vertical line marks the canonical value

$\varGamma _{\chi }$

are affected by insufficient extents of the domain but converge eventually. The grey dashed vertical line marks the canonical value

![]() $\varGamma _{\chi } = 0.2$

. Note the emergent scaling for

$\varGamma _{\chi } = 0.2$

. Note the emergent scaling for

![]() $\varGamma _{\chi }$

for extreme mixing events, and the marked difference of the high tails of the PDFs of

$\varGamma _{\chi }$

for extreme mixing events, and the marked difference of the high tails of the PDFs of

![]() $\varepsilon _{u}$

and

$\varepsilon _{u}$

and

![]() $\chi$

.

$\chi$

.

3.4. Anisotropy of the emergent large-scale dynamics

While the previous § 3.3 has made clear that vertical aspects of the flow dynamics converge for horizontally highly extended domains (only), § 3.1 has demonstrated that the considered forced stratified shear flows also develop certain characteristic horizontal structures such as the primary Kelvin–Helmholtz billows. Therefore, it is appropriate to investigate whether there are at later times, when such early billows have broken down, emergent horizontally aligned structures in the statistically steady flow as well.

Figure 6 shows both the early and final emergent dynamics present in our most extended square domain of

![]() $L_{{h}} = 512$

. Panels (a–d, i–l) depict the entire horizontal cross-section at midplane,

$L_{{h}} = 512$

. Panels (a–d, i–l) depict the entire horizontal cross-section at midplane,

![]() $\varPhi ( z = 0 )$

, whereas panels (e–h, m–p) depict an associated vertical slice at

$\varPhi ( z = 0 )$

, whereas panels (e–h, m–p) depict an associated vertical slice at

![]() $\varPhi ( y = 0 )$

. Note that the vertical slices of

$\varPhi ( y = 0 )$

. Note that the vertical slices of

![]() $b$

from panels (h, p) are reminiscent of figure 2(c,e) despite the domain now being

$b$

from panels (h, p) are reminiscent of figure 2(c,e) despite the domain now being

![]() $16$

times as large. A video of the evolution of this flow – from

$16$

times as large. A video of the evolution of this flow – from

![]() $t = 0$

to

$t = 0$

to

![]() $t = t_{\textit{e}v\textit{o}}=5040$

– is provided as supplemental movie 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2026.11146.

$t = t_{\textit{e}v\textit{o}}=5040$

– is provided as supplemental movie 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2026.11146.

At the earlier time, as shown in panel (h), the flow is – analogously to the simulation discussed in § 3.1 and shown in figure 2 – clearly associated with the growth of the initial KHI and the subsequent nonlinear formation of overturning billows. Interestingly, as becomes clear via the associated horizontal slice in panel (d), although the initial overturning billows may extend across the entire extended spanwise direction, knots, tubes and defects between these rolls may introduce imperfections to this otherwise regular pattern. This effect has also previously been observed experimentally (Thorpe Reference Thorpe1985, Reference Thorpe1987; Caulfield et al. Reference Caulfield, Yoshida and Peltier1996; Thorpe Reference Thorpe2002) and numerically (Fritts et al. Reference Fritts, Lund and Thorpe2022a , Reference Fritts, Wang, Thorpe and Lundb ) for (in the spanwise direction) sufficiently wide domains. However, these early aspects of the flow dynamics appear (at least superficially) to be absent or smeared out by the sustained turbulence at late times as shown in panels (l, p).

Figure 6. Emergent horizontally extended dynamics. From (a–h) early to (i–p) late times, the size of emergent large-scale flow structures exhibits a strong anisotropy between their (a–d, i–l) horizontal and (e–h, m–p) vertical extensions. This figure shows data from the largest square domain,

![]() $L_{{h}} = 512$

, with

$L_{{h}} = 512$

, with

![]() $z=0$

in (a–d, i–l) or

$z=0$

in (a–d, i–l) or

![]() $y = 0$

in (e–h, m–p). While the distinct streamwise ‘overturning billows’ and spanwise ‘knots’ and ‘tubes’ mentioned in the introduction are prominent at early times, these structures (at least superficially) disappear at later times.

$y = 0$

in (e–h, m–p). While the distinct streamwise ‘overturning billows’ and spanwise ‘knots’ and ‘tubes’ mentioned in the introduction are prominent at early times, these structures (at least superficially) disappear at later times.

As the velocity field, in particular

![]() $u_{x}$

as shown in panels (a, e, i, m), exhibits structures that are very similar to the buoyancy field

$u_{x}$

as shown in panels (a, e, i, m), exhibits structures that are very similar to the buoyancy field

![]() $b$

shown in panels (d, h, l, p), the observations made in the previous sections are further supported. However, we find that both the initial pattern formation as well as the late sustained turbulence within the mixing zone can be recognised more easily from the scalar buoyancy field than from the vectorial velocity field.

$b$

shown in panels (d, h, l, p), the observations made in the previous sections are further supported. However, we find that both the initial pattern formation as well as the late sustained turbulence within the mixing zone can be recognised more easily from the scalar buoyancy field than from the vectorial velocity field.

Independently of the specific point in time, this comparison of vertical slices with the corresponding horizontal midplanes demonstrates the co-existence of apparently quasi-regular dynamics in both the streamwise and spanwise directions. However, these visualisations suggest that the emergent large-scale dynamics exhibits a strong scale separation and, thus, anisotropic associated length scales

![]() $\varLambda$

. More specifically, at least qualitatively the horizontal structures seem to be much, much larger than the shear layer half-depth, i.e.

$\varLambda$

. More specifically, at least qualitatively the horizontal structures seem to be much, much larger than the shear layer half-depth, i.e.

![]() $\left \{ d, \delta \right \} \ll \varLambda _{{h}}$

.

$\left \{ d, \delta \right \} \ll \varLambda _{{h}}$

.

As a first step towards a quantitative consideration of the streamwise and spanwise extension of the emergent horizontal dynamics of the flow, we compute the Fourier (energy or co-) spectra

of various quantities. Here,

![]() $\hat {\varPhi }$

represent the Fourier coefficients corresponding to a transform in either the streamwise or spanwise direction, the asterisk

$\hat {\varPhi }$

represent the Fourier coefficients corresponding to a transform in either the streamwise or spanwise direction, the asterisk

![]() $^{*}$

denotes the complex conjugate and

$^{*}$

denotes the complex conjugate and

![]() $k_{x}$

and

$k_{x}$

and

![]() $k_{\!y}$

are the associated streamwise and spanwise components of the wave vector, respectively. In order to allow for a direct comparability of these spectra with their corresponding terms in the kinetic energy or buoyancy variance equation via Parseval’s theorem, the coefficient

$k_{\!y}$

are the associated streamwise and spanwise components of the wave vector, respectively. In order to allow for a direct comparability of these spectra with their corresponding terms in the kinetic energy or buoyancy variance equation via Parseval’s theorem, the coefficient

![]() $C$

depends on

$C$

depends on

![]() $\varPhi _{1}$

and

$\varPhi _{1}$

and

![]() $\varPhi _{2}$

as follows:

$\varPhi _{2}$

as follows:

![]() $C = 1/2$

for

$C = 1/2$

for

![]() $\varPhi _{1} = \varPhi _{2} \in \left \{ u_{x}, u_{\!y}, u_{z}, b \right \}$

,

$\varPhi _{1} = \varPhi _{2} \in \left \{ u_{x}, u_{\!y}, u_{z}, b \right \}$

,

![]() $C = \textit{Ri}_{0}$

for

$C = \textit{Ri}_{0}$

for

![]() $\varPhi _{1} = u_{z} \wedge \varPhi _{2} = b$

(or vice versa),

$\varPhi _{1} = u_{z} \wedge \varPhi _{2} = b$

(or vice versa),

![]() $C = 2 / \textit{Re}_{0}$

for

$C = 2 / \textit{Re}_{0}$

for

![]() $\varPhi _{1} = \varPhi _{2} = \boldsymbol{S}$

or

$\varPhi _{1} = \varPhi _{2} = \boldsymbol{S}$

or

![]() $C = 1 / ( \textit{Re}_{0} {\textit{Pr}} )$

for

$C = 1 / ( \textit{Re}_{0} {\textit{Pr}} )$

for

![]() $\varPhi _{1} = \varPhi _{2} = \boldsymbol{\nabla }b$

. We summarise the key results in figure 7.

$\varPhi _{1} = \varPhi _{2} = \boldsymbol{\nabla }b$

. We summarise the key results in figure 7.

Figure 7. Magnitude quantification of emergent large-scale dynamics. (a) Emergent flow structures offer pronounced spectral peaks

![]() $\hat {\lambda }$

in the streamwise directions for all variables

$\hat {\lambda }$

in the streamwise directions for all variables

![]() $\{ u_{x}, u_{\!y}, u_{z}, b\}$

. In contrast, (b) only the streamwise velocity

$\{ u_{x}, u_{\!y}, u_{z}, b\}$

. In contrast, (b) only the streamwise velocity

![]() $u_{x}$

exhibits a pronounced peak in the spanwise direction. (c) A systematic comparison of characteristic extensions of emergent flow structures along the streamwise, spanwise and vertical directions highlights a strong anisotropy of the large-scale dynamics. Note that while the coloured lines in panels (a–b) correspond to our largest square domain with

$u_{x}$

exhibits a pronounced peak in the spanwise direction. (c) A systematic comparison of characteristic extensions of emergent flow structures along the streamwise, spanwise and vertical directions highlights a strong anisotropy of the large-scale dynamics. Note that while the coloured lines in panels (a–b) correspond to our largest square domain with

![]() $L_{{h}} = 512$

, grey lines in panels (a–c) are extracted from even more extended but non-square domains (

$L_{{h}} = 512$

, grey lines in panels (a–c) are extracted from even more extended but non-square domains (

![]() $L_{x} = 2048$

and

$L_{x} = 2048$

and

![]() $L_{\!y} = 512$

or

$L_{\!y} = 512$

or

![]() $L_{\!y} = 2048$

and

$L_{\!y} = 2048$

and

![]() $L_{x} = 512$

). Moreover, as the dash-dotted line

$L_{x} = 512$

). Moreover, as the dash-dotted line

![]() $L_{x} = L_{\!y}$

in panel (c) demonstrates that flow structures may clearly be limited or affected by horizontally insufficiently extended domains, only horizontal extents

$L_{x} = L_{\!y}$

in panel (c) demonstrates that flow structures may clearly be limited or affected by horizontally insufficiently extended domains, only horizontal extents

![]() $L_{{h}} \gtrsim 256$

are large enough to resolve the most extended flow structures in the horizontal direction.

$L_{{h}} \gtrsim 256$

are large enough to resolve the most extended flow structures in the horizontal direction.

In figure 7(a), we plot the streamwise energy spectra of

![]() $\left \{ u_{x}, u_{\!y}, u_{z}, b \right \}$

, subject to appropriate spatio-temporal averages. Remarkably, we find that all these flow fields exhibit pronounced spectral peaks at streamwise wavenumbers

$\left \{ u_{x}, u_{\!y}, u_{z}, b \right \}$

, subject to appropriate spatio-temporal averages. Remarkably, we find that all these flow fields exhibit pronounced spectral peaks at streamwise wavenumbers

![]() $\hat {k}_{x} \sim \mathcal{O} ( 10^{-2} )$

. This implies that a certain (narrow range of) streamwise wavelength(s)

$\hat {k}_{x} \sim \mathcal{O} ( 10^{-2} )$

. This implies that a certain (narrow range of) streamwise wavelength(s)

![]() $\hat {\lambda }_{x} = 2 \pi / \hat {k}_{x}$

is particularly energetic. In other words, these pronounced spectral peaks establish the existence of flow structures with a characteristic streamwise length scale

$\hat {\lambda }_{x} = 2 \pi / \hat {k}_{x}$

is particularly energetic. In other words, these pronounced spectral peaks establish the existence of flow structures with a characteristic streamwise length scale

![]() $\varLambda _{x} \sim \mathcal{O} ( 10^{2} )$

in all of these flow fields, thus implying that there is a preferred length scale for the emergent streamwise self-organisation of the large-scale dynamics. We propose a potential dynamical origin of this characteristic scale

$\varLambda _{x} \sim \mathcal{O} ( 10^{2} )$

in all of these flow fields, thus implying that there is a preferred length scale for the emergent streamwise self-organisation of the large-scale dynamics. We propose a potential dynamical origin of this characteristic scale

![]() $\varLambda _{x}$

in § 4.

$\varLambda _{x}$

in § 4.

As shown in figure 7(b), this emergent property of the streamwise spectra is in clear contrast to the behaviour of the spanwise spectra. On the one hand, we find a similarly pronounced spectral peak only for the

![]() $x$

-component of the velocity field in the spanwise direction. Together with

$x$

-component of the velocity field in the spanwise direction. Together with

![]() $\hat {k}_{\!y} \sim \mathcal{O} ( 10^{-1} )$

, this implies again the existence of a characteristic spanwise length scale

$\hat {k}_{\!y} \sim \mathcal{O} ( 10^{-1} )$

, this implies again the existence of a characteristic spanwise length scale

![]() $\varLambda _{\!y} \sim \mathcal{O} ( 10^{1} )$

. On the other hand, the other flow fields do not exhibit such a peak but rather flatten out at small

$\varLambda _{\!y} \sim \mathcal{O} ( 10^{1} )$

. On the other hand, the other flow fields do not exhibit such a peak but rather flatten out at small

![]() $k_{\!y}$

, demonstrating that there is no preferred characteristic length scale for the spanwise self-organisation of the large-scale dynamics in

$k_{\!y}$

, demonstrating that there is no preferred characteristic length scale for the spanwise self-organisation of the large-scale dynamics in

![]() $\{ u_{\!y}, u_{z}, b \}$

. We remark that, even though

$\{ u_{\!y}, u_{z}, b \}$

. We remark that, even though

![]() $E_{u_{\!y} u_{\!y}} ( k_{\textit{y, {min}}} ) \lt E_{u_{\!y} u_{\!y}} ( \hat {k}_{\!y} )$

, this difference is smaller than a factor of two and so we do not consider the associated maximum to be a ‘pronounced’ spectral peak.

$E_{u_{\!y} u_{\!y}} ( k_{\textit{y, {min}}} ) \lt E_{u_{\!y} u_{\!y}} ( \hat {k}_{\!y} )$

, this difference is smaller than a factor of two and so we do not consider the associated maximum to be a ‘pronounced’ spectral peak.

It is natural to ask whether there could be additional spectral peaks at even smaller wavenumbers, i.e. whether the large-scale dynamics might still be biased or limited by the finite domain of

![]() $L_{{h}} = 512$

. For this reason, we have conducted two additional simulations which increase either the streamwise or the spanwise extent of the domain by another factor of four. This results in

$L_{{h}} = 512$

. For this reason, we have conducted two additional simulations which increase either the streamwise or the spanwise extent of the domain by another factor of four. This results in

![]() $L_{x} \times L_{\!y} = 2048 \times 512$

or

$L_{x} \times L_{\!y} = 2048 \times 512$

or

![]() $512 \times 2048$

, respectively. We include the associated energy spectra in figure 7(a,b) as grey solid lines. We find no evidence of such additional spectral peaks. Furthermore, as both the location and amplitude of the peaks from these spectra coincide with the ones from our largest square domain, we are confident that there is strong evidence that these spectral peaks are characteristic of this particular flow and, crucially, independent of the horizontal extent of the domain. This implies that the large-scale dynamics is (at such large

$512 \times 2048$

, respectively. We include the associated energy spectra in figure 7(a,b) as grey solid lines. We find no evidence of such additional spectral peaks. Furthermore, as both the location and amplitude of the peaks from these spectra coincide with the ones from our largest square domain, we are confident that there is strong evidence that these spectral peaks are characteristic of this particular flow and, crucially, independent of the horizontal extent of the domain. This implies that the large-scale dynamics is (at such large

![]() $L_{x}$

and

$L_{x}$

and

![]() $L_{\!y}$

) indeed governed by mechanisms intrinsic to the flow. This is supported by Appendix B, where we show that the energy spectra derived from smaller (yet sufficiently large) domains are also shown to converge with the present ones from the largest domains.

$L_{\!y}$

) indeed governed by mechanisms intrinsic to the flow. This is supported by Appendix B, where we show that the energy spectra derived from smaller (yet sufficiently large) domains are also shown to converge with the present ones from the largest domains.

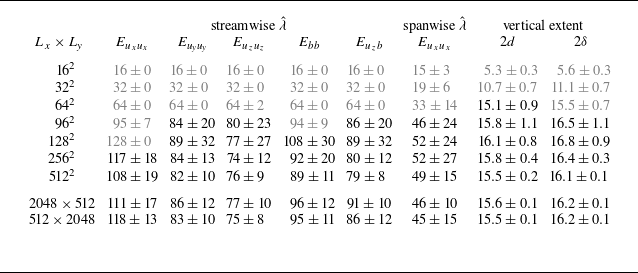

Quantifying characteristic length scales associated with the emergent large-scale dynamics, we extract the wavelengths corresponding to these pronounced spectral peaks (or these spectra’s global maxima) for each simulation and summarise them in table 2. Additionally, figure 7(c) shows this dependence on

![]() $L_{{h}}$

. For small

$L_{{h}}$

. For small

![]() $L_{{h}}$

, as highlighted by the dash-dotted line, these extracted horizontal length scales

$L_{{h}}$

, as highlighted by the dash-dotted line, these extracted horizontal length scales

![]() $\varLambda _{\left \{ x, y \right \}}$

are clearly biased by the extent of the domain. However, this changes once

$\varLambda _{\left \{ x, y \right \}}$

are clearly biased by the extent of the domain. However, this changes once

![]() $L_{{h}} \gtrsim L_{\textit{h, crit}}$

with the critical horizontal extent

$L_{{h}} \gtrsim L_{\textit{h, crit}}$

with the critical horizontal extent

![]() $L_{\textit{h, crit}}$

depending on the solution field (and, thus, the associated final characteristic length scale). While most of the peaks are already properly represented given

$L_{\textit{h, crit}}$

depending on the solution field (and, thus, the associated final characteristic length scale). While most of the peaks are already properly represented given

![]() $L_{\textit{h, crit}} = 96$

, some of them – such as

$L_{\textit{h, crit}} = 96$

, some of them – such as

![]() $\hat {\lambda }_{x} ( E_{u_{x} u_{x}} )$

– may require

$\hat {\lambda }_{x} ( E_{u_{x} u_{x}} )$

– may require

![]() $L_{{h}} = 256$

to be fully resolved. Hence, for the set of control parameters considered here, a full convergence of the characteristic length scales associated with the large-scale dynamics is reached for

$L_{{h}} = 256$

to be fully resolved. Hence, for the set of control parameters considered here, a full convergence of the characteristic length scales associated with the large-scale dynamics is reached for

![]() $L_{{h}} \gtrsim 256$

only. This convergence of finite horizontal scales is, at least qualitatively, consistent with the convergence of the finite vertical depth of the shear layer as addressed in the previous sub-sections.

$L_{{h}} \gtrsim 256$

only. This convergence of finite horizontal scales is, at least qualitatively, consistent with the convergence of the finite vertical depth of the shear layer as addressed in the previous sub-sections.

Table 2. Emergent dynamical length scales. This table quantifies the streamwise, spanwise and vertical extent of the emergent large-scale dynamics via the wavelength associated with the spectral peaks and total depths of the shear layer or density interface. We list values of the temporal mean and standard deviation, the latter of which might be significant due to the discrete nature of wavenumbers. Unreliable values, i.e. those clearly affected by the (insufficiently extended) finite domain, are displayed in grey.

In addition to the characteristic streamwise and spanwise length scales associated with the large-scale dynamics, we include their characteristic vertical extent via the total shear layer depth in figure 7(c). Note that, since

![]() $d \approx \delta$

or

$d \approx \delta$

or

![]() $R \approx 1$

, these data points equivalently show the total buoyancy interface depth. Comparing the characteristic length scales in the three spatial directions (as denoted by different symbol types), there is a clearly apparent anisotropy of the large-scale dynamics. While vertical scales

$R \approx 1$

, these data points equivalently show the total buoyancy interface depth. Comparing the characteristic length scales in the three spatial directions (as denoted by different symbol types), there is a clearly apparent anisotropy of the large-scale dynamics. While vertical scales

![]() $\varLambda _{z} \approx 16$

(circles) and spanwise scales

$\varLambda _{z} \approx 16$

(circles) and spanwise scales

![]() $\varLambda _{\!y} \approx 50$

(upright triangles), streamwise scales (sideways triangles) may extend up to

$\varLambda _{\!y} \approx 50$

(upright triangles), streamwise scales (sideways triangles) may extend up to

![]() $\varLambda _{x} \approx 115$

. Consequently, we find a hierarchy

$\varLambda _{x} \approx 115$

. Consequently, we find a hierarchy

![]() $\varLambda _{z} \lt \varLambda _{\!y} \lt \varLambda _{{x}}$

that spans across one order of magnitude.

$\varLambda _{z} \lt \varLambda _{\!y} \lt \varLambda _{{x}}$

that spans across one order of magnitude.

Having extracted these characteristic scales of the large-scale dynamics, there are two particularly striking observations. Firstly, while

![]() $u_{z}$

and

$u_{z}$

and

![]() $b$

are related to the vertical transport of buoyancy via equation (3.5), their individual scales

$b$

are related to the vertical transport of buoyancy via equation (3.5), their individual scales

![]() $\hat {\lambda }_{x}$

in