Highlights

-

Lingual seizures manifest as hyperkinetic tongue movements due to epileptogenic activity and typically present as focal motor seizures with preserved awareness.

-

Lingual seizures may be isolated or involve other muscles, often linked to acute cerebral lesions.

-

EEG findings are often inconclusive, but movement characteristics and imaging provide valuable diagnostic insights.

Introduction

Involuntary lingual movements can arise from various underlying causes. These movements frequently occur alongside multi-organ movement disorders, including Wilson’s disease, Reference Liao, Wang, Kwan, Kong and Wu1 tardive dyskinesia, Reference Zivković, Costa, Bond and Abu-Elmagd2 encephalitis and epilepsy. Reference Lundberg, Frylmark and Eeg-Olofsson3 Hyperkinetic tongue movements – whether isolated or accompanied by dyskinesia in other body regions – represent a spectrum of differential diagnoses. Epileptic conditions provide a context where lingual hyperkinetic movements may result from motor cortex involvement. Neurofunctional studies have identified the location of motor neurons responsible for tongue movements within the motor homunculus, situated on the inferior side near the lateral fissure. The first description of lingual movements linked to focal epileptic seizures was provided by Holtzman et al. in 1984 in a patient with a convexity meningioma in the post-central gyrus. Reference Holtzman, Mark, Wiener and Minzer4 Since then, additional cases have been reported, although instances of isolated lingual or lingual seizures with other body parts remain rare.

Lingual seizures, whether occurring in isolation or alongside epileptic cranial muscle contractions, represent a rare and intriguing aspect of seizure semiology. These movements may serve as the initial manifestation of epileptic seizures with Jacksonian progression, Reference Neufeld, Blumen, Nisipeanu and Korczyn5 making their identification clinically significant. Despite their rarity, lingual seizures have been documented in a limited number of case reports, often evaluated on a case-by-case basis using clinical, radiological and electroencephalographic (EEG) assessments. While EEG findings in isolated lingual seizures are usually inconclusive, cerebral imaging frequently reveals associated structural lesions. In this study, we move beyond individual cases to analyze a cohort of patients, aiming to provide a comprehensive understanding of lingual seizures. Our objective is to characterize their clinical features, associations with other body regions, underlying causes and ictal and interictal EEG findings, along with cranial imaging results. By doing so, we seek to underscore the importance of recognizing and understanding this rare and often underappreciated ictal phenomenon, highlighting its clinical, electrophysiological and imaging characteristics.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed hospital records to identify patients with isolated lingual seizures or those accompanied by movements in other body regions between 2014 and 2023. Patients with bilateral tongue movements, a diagnosed movement disorder or a history of antipsychotic medication use were excluded from the study. Demographic details, including age and sex, prior epilepsy diagnoses, seizure characteristics, ictal and interictal EEG findings, cerebral imaging results and underlying etiologies, were systematically analyzed. Seizures were classified as focal motor seizures with or without awareness, following the ILAE 2017 classification. Reference Fisher, Cross and French6

Focal motor seizures with awareness were classified as epilepsia partialis continua (EPC) if they persisted for at least 1 hour. Reference Mameniškienė and Wolf7 Seizures that did not meet this criterion but occurred multiple times a day were categorized as frequent seizures. EEG recordings were performed using surface electrodes following the International 10–20 system. All patients underwent video-EEG monitoring, with each session lasting approximately 30 minutes. These recordings were meticulously reviewed to identify cases of isolated lingual seizures or lingual seizures combined with movements of other body parts. Based on the affected body regions associated with epileptic lingual movements, patients were classified into three groups: those with isolated lingual seizures, those involving both lingual and cranial muscles and those involving lingual, cranial and extremity muscles. In cases where muscle activity was recorded using surface or needle electrodes during polygraphic video-EEG sessions, muscle twitches were assessed in correlation with EEG discharges. The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Ege University (Approval Number: 2024-3237).

Results

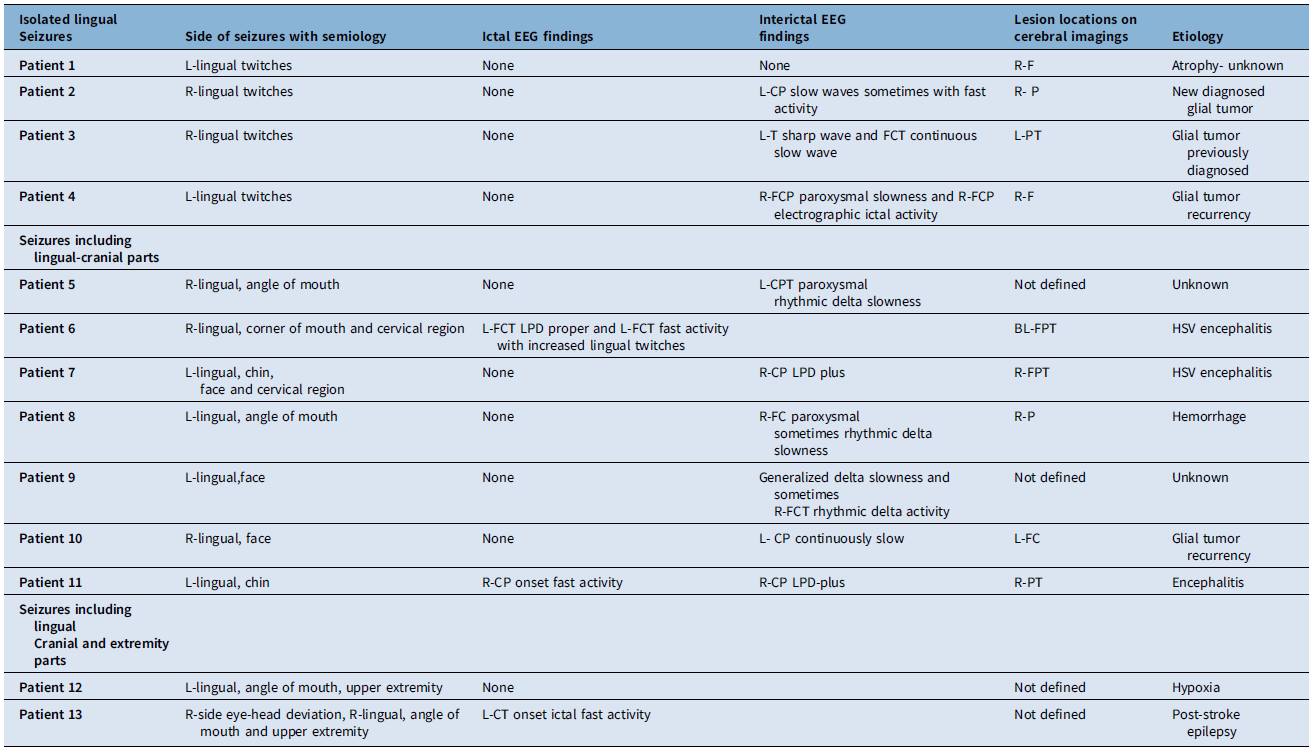

Thirteen patients (five females, eight males; mean age 57 years, range 31–89) were identified, six of whom had a prior diagnosis of epilepsy linked to chronic cerebral lesions from glial tumors or gliosis. All patients experienced their first epileptic lingual movements, with seizures occurring on the left side in six and on the right side in seven patients. Isolated lingual seizures were marked by uncontrollable tongue movements, while others also exhibited additional symptoms, such as twitching of the face, mouth or extremities, as reported by patients or witnessed during unconsciousness in the hospital. Most evaluations took place within one week of symptom onset. Seizures were confined to the tongue in four cases, involved cranial muscles in seven and extended to cranial and upper extremity muscles in two, with no involvement of the lower extremities. Twitching at the mouth corner on the same side as the lingual movements was the most common observation, followed by unilateral facial twitches. Ipsilateral chin and neck twitches occurred less frequently but were often accompanied by mouth and facial muscle twitching, as recorded in video documentation.

Among the 13 patients, 11 experienced focal-aware seizures, one had focal-unaware seizures and awareness could not be assessed in one case due to cerebral hypoxia following cardiac arrest. All patients with isolated lingual seizures or those involving lingual and cranial muscles exhibited focal-aware seizures, while one patient with seizures affecting lingual, cranial and upper extremity muscles had motor seizures with impaired awareness. Seven patients were diagnosed with EPC, including two with isolated lingual seizures and five with seizures involving lingual and cranial muscles. Frequent seizures were observed in five patients, including two with isolated lingual seizures, two with lingual and cranial muscle involvement and one with lingual, cranial and upper extremity involvement. Demographics, affected body regions and seizure classifications are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic findings, patient groups depending on the affected body part and seizure classification

EPC = epilepsia partialis continua; 1*; this patient was unaware during seizures, but it was not related to ictal activity. He had hypoxic brain injury after cardiac arrest. He had continuous one-sided lingual, mouth and upper extremity twitching. F = female; M = male.

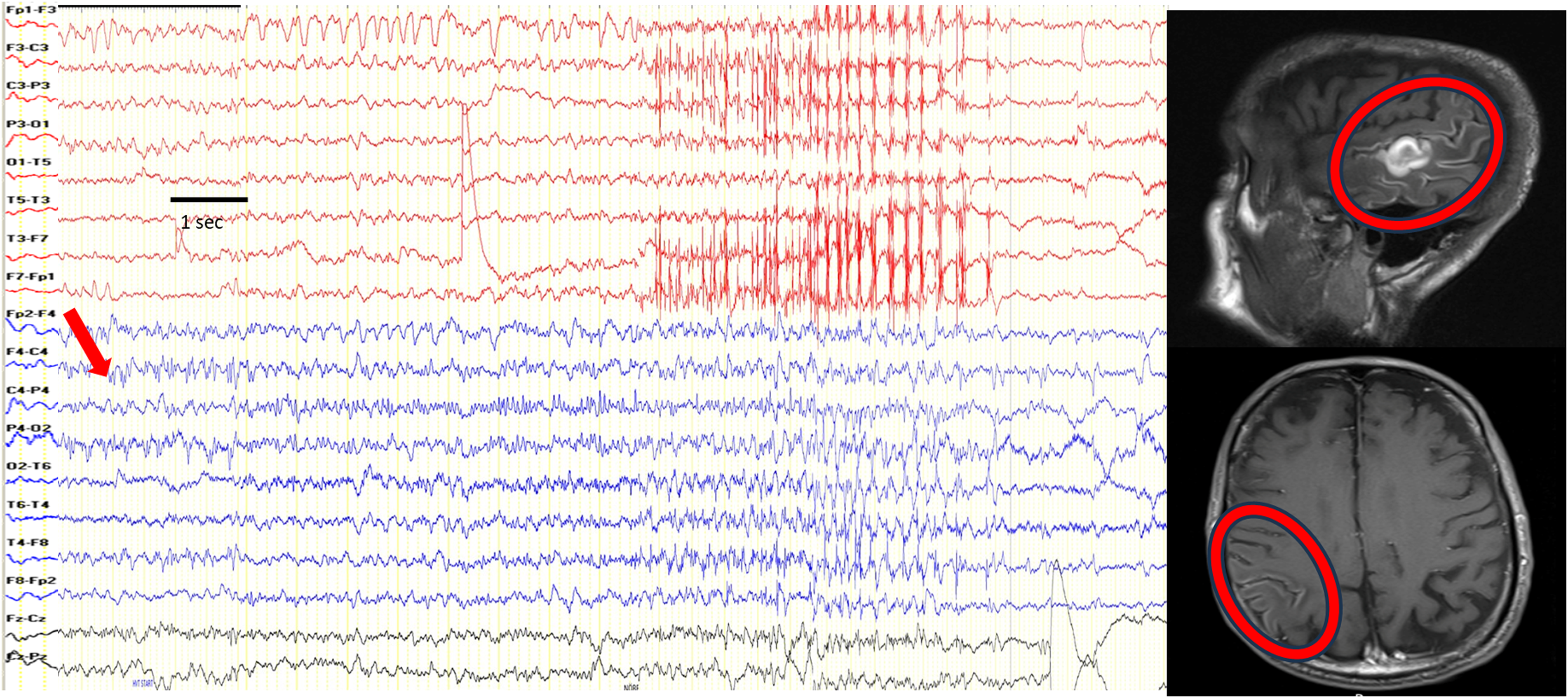

Ictal EEG recordings were obtained from 12 patients, while 1 patient had only interictal EEG data due to the absence of clinical seizures during the recording session. Both ictal and interictal EEG consistently showed involvement of the hemisphere contralateral to the lingual twitches. Among the four patients with isolated lingual seizures, three had ictal EEG recordings (two diagnosed with EPC and one with frequent seizures), and one had interictal findings. Lingual twitches were recorded using either needle or surface electromyography (EMG) electrodes; however, no ictal electrographic activity was detected in these cases. In one patient, positron emission tomography–MRI (PET–MRI) identified a hypermetabolic area responsible for seizures despite a normal ictal EEG (Figure 1). The other two displayed distinct patterns: one demonstrated paroxysmal sharp waves in the centroparietal (CP) region, sometimes accompanied by fast activity, and the other exhibited continuous slow waves in the frontocentroparietal region. The patient with interictal EEG findings showed frontocentroparietal paroxysmal slowing and electrographic seizure activity (Figure 2). Ictal EEG recordings were obtained for all patients with seizures involving lingual and cranial muscles, with five diagnosed with EPC and two experiencing frequent seizures. Lingual twitches were recorded using surface electrodes in the submental region for three patients, while facial twitches were captured using electrodes on the twitching corner of the mouth in one patient. The ictal electrographic activity was observed in two cases: one with EPC showed frontocentrotemporal lateralized periodic discharges (LPD)-proper activity accompanied by progressively intensifying fast activity (Figure 3), and another with frequent seizures demonstrated CP-onset fast activity that built up and ended with slowing (Figure 4). In the remaining patients, ictal EEG revealed continuous or paroxysmal slowing in various regions, including CP and frontocentrotemporal, but these patterns were not classified as electrographic ictal seizure activity. One patient exhibited CP LPD-plus activity during clinical seizures without simultaneous muscle twitch recordings. In the group of two patients with seizures involving lingual, cranial and upper extremity muscles, one patient with EPC exhibited CP LPD-plus discharges that persisted despite intravenous diazepam and could not be conclusively classified as ictal. This patient also had a history of cerebral hypoxia following cardiac arrest. The second patient demonstrated electrographic seizure activity originating in the centrotemporal region, which spread to the frontocentroparietal area. The seizure began with staring and head and eye deviation to the right, followed by right-sided mouth and tongue twitching, which progressed to involve the right face, arm and abdomen in a march-like pattern.

Figure 1. A patient with isolated lingual seizures presenting as epilepsia partialis continua. Lingual twitches were seen on the left side, submental needle electrode on the left side recorded muscle twitches on channels X3-X4. It is seen that lingual twitches occur once per second (black arrow). Electroencephalography did not show any ictal electrographic seizure activity. Cranial MRI showed right frontal atrophy (red circle), and PET–MRI showed a hypermetabolic focus on the atrophic brain region (red arrow). Note: Longitudinal bipolar montage; high-cut filter, 35 Hz; low-cut filter, 1.6 Hz. Sensitivity: 7 µV/cm, 10 seconds/page. For muscle activity recording, channels X3-X4; high-cut filter, 120 Hz; low-cut filter, 53 Hz. Sensitivity: 30 µV/cm.

Figure 2. A patient with frequent isolated lingual seizures. Lingual twitches were observed on the left side. During electroencephalography (EEG) recording, clinical seizure did not occur, but electrographic seizure activity was seen on the right frontocentroparietal region (red arrow). Cranial MRI revealed the right frontal lesion (red circles). Note: Referential montage to ipsilateral ears, high-cut filter, 35 Hz; low-cut filter, 1.6 Hz. Sensitivity: 7 µV/cm, 10 seconds/page. The EEG is formed by combining two consecutive pages.

Figure 3. A patient with seizures, including lingual and cranial muscles, presenting as epilepsia partialis continua. Muscle twitches were seen on the right side of the tongue, angle of the mouth and cervical region. Facial twitches were recorded with surface electrodes positioned on the corner of the mouth, seen on channel X1-X2 (asterisk). EEG showed left frontocentrotemporal lateralized periodic discharges (LPD) activity (black thin arrows) coinciding with muscle twitches once per second. When the muscle twitches intensified (thick blue arrow), as seen twice per second, frontocentrotemporal fast activity appeared (red arrow). Cranial MRI showed a left frontoparietotemporal lesion (red circles). Note: Referential montage to central electrode, high-cut filter: 35 Hz; low-cut filter: 1.6 Hz. Sensitivity: 7 µV/cm, 20 seconds/page. For muscle activity recording, channels X1-X2; high-cut filter, 120 Hz; low-cut filter, 53 Hz. Sensitivity: 15 µV/cm.

Figure 4. A patient with frequent seizures including lingual and cranial muscles. During the seizure, his lingual and chin muscles were twitching to the left side. At the same time, ictal centroparietal-onset fast activity (red arrow) progressively built up and ended with slowing on the EEG. Cranial MRI showed right parietotemporal lesion (red circle). Note: Longitudinal bipolar montage, high-cut filter: 35 Hz; low-cut filter: 1.6 Hz. Sensitivity: 7 µV/cm, 20 seconds/page. The EEG is formed by combining four consecutive pages.

Cranial imaging was conducted in 13 patients, including CT in 3 cases and MRI in 10 cases. MRI could not be performed in two patients due to the presence of a cardiac pacemaker and a metallic prosthesis. Additionally, one patient underwent only cranial CT. Cerebral lesions were identified in 9 out of 13 patients. Subgroup analysis revealed that MRI detected lesions in all four patients with isolated lingual seizures and in five out of seven patients with seizures involving both lingual and cranial muscles. In the two patients with seizures involving lingual, cranial and upper extremity muscles, cranial CT did not reveal any abnormalities. Furthermore, in one patient with seizures involving lingual and cranial muscles, cranial CT showed evidence of cerebral hemorrhage. In terms of lesion locations, the frontal region was affected in two patients, the parietal region in two patients, the parietotemporal region in two patients, the frontoparietotemporal region in two patients and the frontocentral region in one patient. The underlying etiologies were identified in 10 patients, with glial tumors (4 patients), encephalitis (3 patients), intracerebral hemorrhage (1 patient), ischemic stroke (1 patient) and hypoxic brain injury (1 patient) as the main causes. Cerebral lesions were localized to the hemisphere contralateral to the observed twitches in the tongue and other body parts, consistent with the ictal and interictal EEG findings. A summary of the EEG findings, lesion locations and underlying etiologies is provided in Table 2. Levetiracetam, phenytoin, lacosamide and topiramate were used as anti-seizure medications for treatment.

Table 2. Seizure semiology with ictal-interictal EEG findings, lesion locations on cerebral imaging and etiology

R = right; L = left; F = frontal; P = parietal; T = temporal; CP = centroparietal; FCP = frontocentroparietal; FC = frontocentral; PT = parietotemporal; CT = centrotemporal; FCT = frontocentrotemporal; CPT = centroparietotemporal; FPT = frontoparietotemporal; LPD = lateralized periodic discharges; EEG = electroencephalography.

Discussion

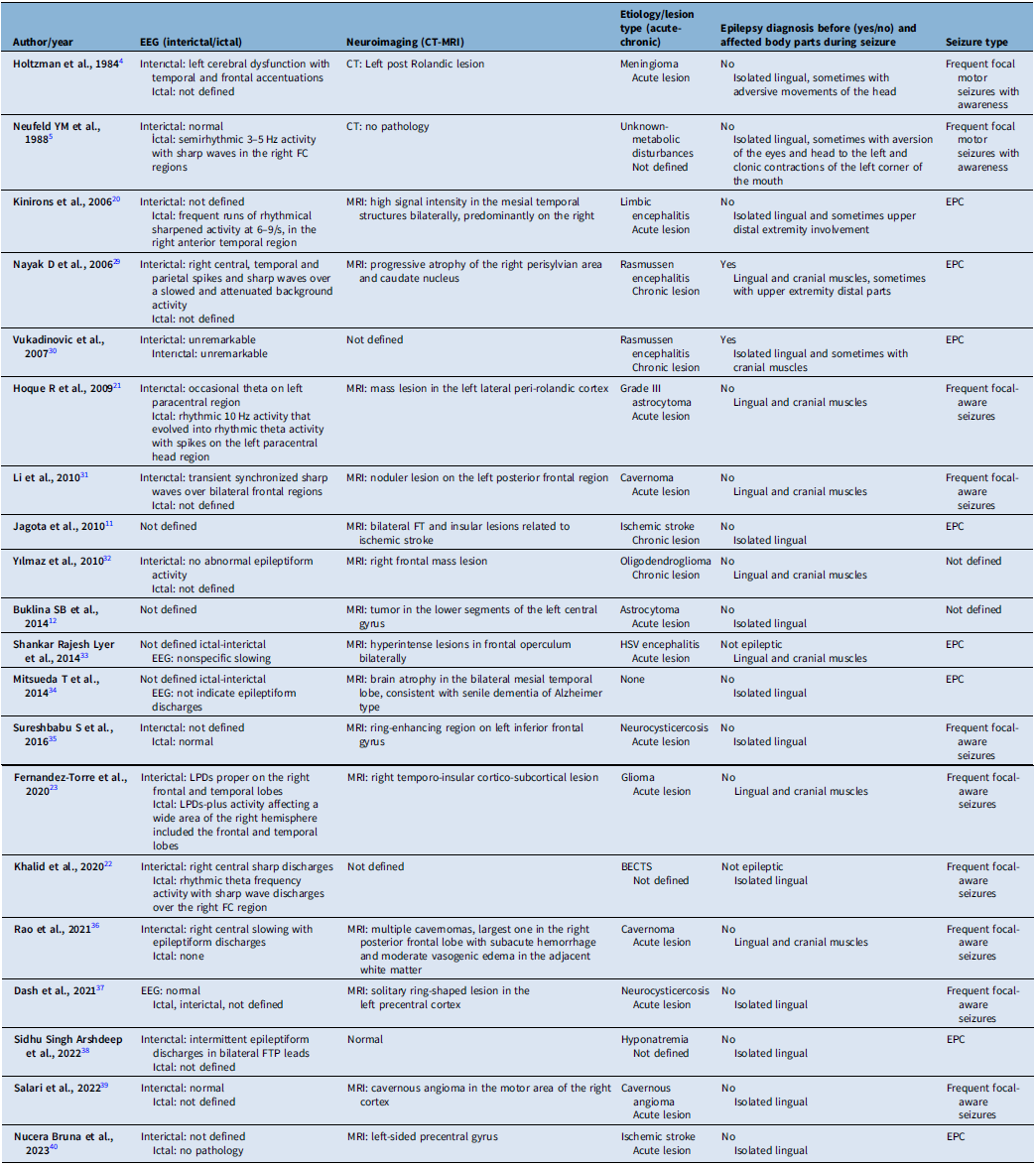

In this study, we tried to characterize the clinical, electrophysiological and etiological features of lingual seizures, whether isolated or occurring alongside cranial and extremity muscle involvement. In most cases, the synchronous involvement of other cranial regions, particularly the face or the upper extremities, suggests a cortical origin for these movements. However, focal motor status epilepticus (SE) or seizures confined to one side of the tongue are rare and pose significant diagnostic challenges. Seizure semiology, neuroimaging and video-EEG findings – despite limitations caused by muscle artifacts and the absence of clear EEG abnormalities – can assist in distinguishing epileptic lingual seizures from non-epileptic conditions, such as lingual myoclonus. Non-epileptic conditions like essential myoclonus often present with rhythmic and symmetrical tongue movements, Reference Bettoni, Bortone, Chiusi, Tortorella, Zanferrari and Mancia8–Reference Kulisevsky, Avila and Grau-Veciana10 whereas jerky, non-rhythmic and stimulus-sensitive movements typically characterize cortical myoclonus. Reference Jagota and Bhidayasiri11 Notably, exacerbating lingual twitches during tongue movements can further help differentiate isolated epileptic movements from non- epileptic phenomena. Reference Buklina, Pronin, Zhukov, Pilipenko and Maryashev12 A review of the literature, which is shown in Table 3, highlights that most cases of epileptic lingual movements are associated with cranial muscle twitches, followed by isolated lingual seizures. Upper extremity involvement is the least common (Table 3). Consistent with these findings, our study observed that 31% of cases presented with isolated lingual seizures, 54% involved seizures affecting both the tongue and cranial muscles, and 15% included seizures involving the tongue, cranial muscles and upper extremities. In isolated lingual seizures, unilateral, jerky and non-rhythmic tongue movements were the most frequent presentation. However, it remained difficult to determine whether these movements exacerbated the jerking of the tongue. All patients in our cohort demonstrated either cranial lesions or EEG findings consistent with epileptic lingual movements. Among patients with cranial muscle involvement, the facial muscles were most frequently affected, particularly the ipsilateral corner of the mouth. In cases with upper extremity involvement, movements predominantly affected the distal parts, such as the hands and fingers. These findings align with the existing literature, which also identifies facial muscles as the most commonly affected cranial muscles and distal regions as the most frequently involved parts of the upper extremities (Table 3). Importantly, no cases of lower extremity involvement have been reported, and our study similarly did not observe any lower extremity involvement. Although the precise relationship between specific facial muscle movements and motor cortex regions is not entirely understood, the distribution of affected body parts in our study aligns with the somatotopic organization of the motor cortex. The motor map of the primary cortex, as first described through cortical stimulation studies by Krause, Reference Krause13 Penfield, Reference Penfield and Boldrey14,Reference Penfield and Jasper15 and Jasper, Reference Penfield and Jasper15 places the tongue and lips near the

Table 3. Defined cases in the literature in terms of EEG, neuroimaging findings and seizure types

EEG = electroencephalography; EPC = epilepsia partialis continua; BECTS = benign partial epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes; FC = frontocentral; FTP = fronto-temporo-parietal; FT = fronto-temporal.

Sylvian fissure, followed by the thumb, fingers, arm and trunk along the central sulcus, with the leg, foot and toes represented on the mesial surface. Movements of the face, including the tongue, are associated with widespread areas of the precentral gyrus, with significant overlap between the regions controlling tongue and lip movements. Reference Roux, Niare, Charni, Giussani and Durand16

Our study found that lingual seizures predominantly presented as focal-aware motor seizures. All patients with isolated lingual seizures or those involving lingual and cranial muscles were classified as having focal-aware seizures. Among the two patients with seizures affecting lingual, cranial and upper extremity muscles, one experienced a loss of awareness, while the other’s awareness could not be evaluated. These findings suggest that lingual seizures, whether isolated or accompanied by cranial muscle involvement, are typically focal-aware, consistent with existing literature (Table 3). In our cohort, 54% of patients were diagnosed with EPC, while 38% experienced frequent seizures. Half of the patients with isolated lingual seizures had EPC, with the remaining exhibiting frequent seizures. Among those with lingual and cranial muscle involvement, 71% were diagnosed with EPC, and 29% experienced frequent seizures. These results emphasize the significant cortical representation of the tongue, which plays a key role in focal motor seizures, particularly in EPC. EPC, a rare form of SE, primarily affects limb muscles, while isolated involvement of the tongue is exceptionally rare. Reference Mameniškienė and Wolf7 The face, shoulder, arm and hand are the most frequently affected body regions, with a notable predilection for distal muscles. In contrast, lower limb involvement is less common and less clearly documented. This distribution likely reflects the proportional cortical representation of various body parts. Interestingly, the cortical representation of the tongue is at least as extensive as that of the hand. Reference Roux, Niare, Charni, Giussani and Durand16 Though a temporal relationship between lingual, cranial and upper extremity twitches was not consistently documented, co-occurrence was observed, aligning with previous reports (Table 3). Jacksonian progression in lingual seizures is rare; however, our case involving lingual, cranial and upper extremity twitches showed progression from head and eye deviation to twitching of the tongue, face and upper extremities, suggesting lingual twitches may occur at varying stages of seizure evolution.

In our study, ictal EEG activity associated with clinical seizures was primarily observed in patients with seizures involving both lingual and cranial muscles, as well as those affecting the upper extremities (33% of such cases). In contrast, no corresponding ictal EEG changes were detected during unilateral lingual twitches in cases of isolated lingual seizures presenting as EPC or frequent seizures. These findings align with existing data, which also highlight that ictal EEG abnormalities are most commonly identified in seizures involving lingual-cranial muscles and upper extremities (Table 3). This may be explained by the limited cortical activation of the tongue area, which might be too small to be effectively captured by scalp electrodes. Reference Brigo17 Moreover, earlier studies on EPC have shown that ictal surface EEG is unable to detect abnormalities in about one-fifth of patients. Reference Mameniškienė and Wolf7,Reference Pandian, Thomas and Santoshkumar18 This limitation arises from seizure activity involving at least 10 cm2 of cortical tissue to produce a detectable pattern on scalp EEG. Reference Tao, Ray, Hawes-Ebersole and Ebersole19 By contrast, interictal EEG recordings in our cases of isolated lingual seizures revealed slow-wave activity over the hemisphere contralateral to the lingual twitches, specifically on frontocentral or CP electrodes in three patients. We interpret this slow-wave activity as being associated with underlying cerebral lesions, as all patients with isolated lingual seizures exhibited lesions in the frontal or parietal regions, corresponding to the interictal EEG abnormalities. Additionally, interictal electrographic seizure activity was observed in one patient over frontocentral electrodes. However, the literature does not define findings related to long-term EEG monitoring in similar cases. In one of our patients, the presence of defined electrographic seizure activity underscores the potential importance of EEG monitoring in identifying ictal features in such presentations.

In our cases, ictal EEG findings included LPD in one patient and fast activity in two patients. The most defined ictal activity in the reported cases is rhythmic activity intermixed with spike or sharp wave discharges. Reference Neufeld, Blumen, Nisipeanu and Korczyn5,Reference Kinirons, O’Dwyer, Connolly and Hutchinson20–Reference Khalid, Ilyas and Abdelmoity22 In only one patient with lingual and cranial muscles involved seizures, LPD-plus activity is defined as an ictal activity. Reference Fernández-Torre, Lucas, Urdiales-Sánchez, Fernández-Lozano, Martínez-Dubarbie and Hernández- Hernández23 This patient also had LPD-proper interictally due to glioma detected on cranial MRI. It is known that the most common causes of LPDs are stroke, infection, tumor and hemorrhage. Reference Lin and Drislane24 The classification of LPDs as ictal activity remains debated, particularly in cases involving acute cerebral lesions. However, when focal twitching or movements are time-locked to the discharge, LPDs are generally considered ictal. Reference Brenner and Schaul25 At this time, video-EEG recording coupled with EMG polygraphy is essential to detect the relationship between focal twitching and discharges. Moreover, a study by Sen-Gupta et al. found that LPDs with motor manifestations are more likely to arise from central head regions. Reference Sen-Gupta, Schuele, Macken, Kwasny and Gerard26 Although we did not record in all of our cases, we used this technique to understand in the recorded ones if there were any ictal findings and the relation between the ictal findings and muscle twitches. In one patient, we could classify LPD as an ictal activity with the help of simultaneous muscle recordings. This activity was seen on the centrotemporal electrodes in the EEG. Although the clinical presentation was consistent with EPC, and LPD-plus activity was detected in two patients, it could not be definitively classified as ictal activity. The presence of acute lesions complicated the identification of LPD as ictal activity. In these patients, despite obtaining video-EEG recordings, muscle activity associated with LPD could not be documented. So, the lack of simultaneous muscle recordings with LPDs with the acute cerebral lesions prevented us from confirming it as ictal. The LPD-plus activity was seen on CP electrodes in both patients. We speculate that the LPD-plus activity in these cases could reflect ictal activity. LPDs can be classified into two types based on their morphology: “LPDs plus,” which involve rhythmic discharges, and “LPDs proper,” which lack these rhythmic features. Reference Reiher, Rivest, Grand’Maison and Leduc27 Seizures and SE are significantly more common in patients with LPDs plus (74%) compared to those with LPDs proper (6%). Reference Reiher, Rivest, Grand’Maison and Leduc27 This was confirmed in a multicenter study of 4,772 patients undergoing continuous EEG, which showed that patients with LPDs plus had a higher association with seizures. Reference Rodriguez Ruiz, Vlachy and Lee28 Moreover, the ictal and interictal surface EEG predominantly revealed abnormalities in the CP and frontocentral regions contralateral to the side of the tongue twitching in our cases. This finding also aligns with most reported cases in the literature (Table 3).

A possible mechanism for lingual seizures is the excitation of the opercular motor cortex; however, the mechanisms through which different etiologies trigger this excitation remain unclear. Lesions associated with lingual seizures have been reported in cases of glial tumors, infectious or autoimmune encephalitis, cavernomas and ischemic stroke (Table 3). These lesions are predominantly located in the frontal, parietal, temporal and peri-insular regions and are often observed as newly developed cerebral lesions (Table 3). In our study, cerebral lesions were identified in 69% of cases, with the affected regions including the frontal, parietotemporal, frontoparietotemporal and frontocentral areas. The frequency of lesions across these regions showed no significant variation. Notably, the cerebral lesions consistently corresponded to the same side as the pathological EEG findings. Glial tumors were the most frequently observed lesions (31% of cases), followed by encephalitis-related lesions (23% of cases). Newly developed lesions were detected in 54% of cases: three cases of encephalitis-related lesions, one case of cerebral hemorrhage, two cases of recurrent glial tumors and one newly diagnosed glial tumor. These findings suggest that lingual seizures are frequently associated with newly developed cerebral lesions and represent a distinct seizure semiology in patients with lesion-related epilepsy. Additionally, lingual seizures may occur as a unique manifestation of new-onset focal epilepsy in individuals with no prior history of epilepsy.

Our study has several limitations. First, the data were collected retrospectively. Moreover, we were unable to perform follow-ups with the patients, leaving the drug responsiveness of these seizures unknown. Although we re-evaluated the video-EEG recordings for all patients, muscle twitches were not consistently recorded using surface or needle electrodes, as would have been possible with video-EEG recording coupled with EMG polygraphy. This limitation is particularly critical for detecting ictal LPD activity in patients with concurrent acute cerebral lesions. Additionally, we relied exclusively on surface scalp EEG findings and did not conduct long-term EEG monitoring, which may be especially important for detecting abnormalities in cases of isolated lingual seizures with otherwise normal EEG findings.

Conclusions

This study examined lingual seizures in terms of clinical features, etiology, EEG findings and cranial imaging results. Our results indicate that lingual seizures, though rare, can present with hyperkinetic tongue movements as epileptic manifestations. When isolated, EEG findings are often inconclusive, but movement characteristics and imaging provide valuable diagnostic insights. In non-isolated cases, seizures frequently involve facial muscles and, less commonly, the upper limbs. Typically, these seizures present as focal motor seizures with preserved awareness and are associated with new-onset cerebral lesions. To improve the detection of ictal activity, especially in acute cases, integrating muscle twitch recordings during EEG may enhance the characterization of ictal LPDs associated with these seizures.

Author contributions

All authors participated in study conception and design and interpretation of results. All the co-authors contributed to the project implementation and data collection. The first author analyzed data and drafted the first version of the manuscript. The last author supervised the whole process. All authors revised and approved the manuscript before submission and take responsibility for the contents of the article.

Funding statement

There is no financial support.

Competing interests

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.