Salt has been extracted by humans since at least Neolithic times in different types of environments around the world. It comes from two main sources—seawater and sodium chloride minerals halite (rock salt) and gypsum/anhydrite—and is found either in dissolved phases (e.g., sea, salt marshes, springwaters) or as solid minerals (e.g., rocks, outcrops, earths, sands, and plants). Today, salt is a principal food staple and seasoning (Adshead Reference Adshead1992; Alexianu et al. Reference Alexianu, Curcă, Weller and Dumas2023; Kurlansky Reference Kurlansky2000), is the main source of sodium and chloride ions, and is a potential source of strontium in the human diet (Fenner and Wright Reference Fenner and Lori2014). In addition to its nutritional and health benefits, in the past salt helped eliminate human dependence on the seasonal availability of food by enabling its preservation and transportation over large distances. In addition to these common uses, salt also has been applied as a medicine, tanning agent, an adjuvant for dairy products, and an essential component in precious metal electrolytes and dye-fixing. Although exploited in different environments worldwide and used in many ways, salt often was difficult to obtain, making it a highly valued exchange item and a form of currency in some past societies (Antonites Reference Antonites2020; D’Ercole Reference D’Ercole2020; Harding Reference Harding2021; Stöllner Reference Stöllner, Bartels and Küpper-Eichas2008).

Archaeological and ethnographic research studies have revealed that Indigenous peoples extracted salt from different environments through solar evaporation, boiling brine (water with a high concentration of salt), and mining rock salt. Some of the earliest evidence of production is in salt springs and salty deposits in the Old World, dating ∼8000 cal BP in Romania (Harding Reference Harding2021; Weller et al. Reference Weller, Dumitroaia, Sordoillet, Dufraisse, Gauthier, Munteanu, Weller, Dufraisse and Pétrequin2008) and China (Chen Reference Chen, Allard, Sun and Linduff2018; Flad Reference Flad2008) and ∼7000 cal BP in Austria (Megaw et al. Reference Megaw, Morgan and Stöllner2000) and Spain (Weller Reference Weller2002). In the Americas, early salt procurement most often is associated with coastal wetlands and sedimentary deposits in the arid highlands of Mexico, Peru, Bolivia, and Chile (e.g., Alonso Reference Alonso and Juan1991; Andrews Reference Andrews1983; Pueyo et al. Reference Juan José, Demergasso, Escudero, Chong, Cortéz-Rivera, Sanjurjo-Sánchez, Carmona and Giralt2021). In these settings, production derived principally from artificially processing brine or from the extraction of salty sediments. Some of the earliest and best-known procurement areas are in Mexico where salt was extracted during the Formative period through solar evaporation of salty deposits in ceramic trays (e.g., McKillop Reference McKillop2021; Williams Reference Williams, Staller and Carrasco2009, Reference Williams2021). Of particular interest here is evidence of the Classic highland Maya producing salt by boiling brine from salt springs in pots. Discarded brine-boiling pots appear to have been uniform in size, suggesting the production of standardized salt cakes and their use as units of exchange and possibly currency in markets (McKillop Reference McKillop2021). In the Andes, the precontact extraction of salt is little known, except for late pre-Inka and Inka societies in the highlands of Peru, Bolivia, and Chile (e.g., Beltran Reference Beltran, Alexianu, Curcă, Weller and Dumas2023; Eerkens et al. Reference Eerkens, Vaughn and Grados2009; Jennings et al. Reference Jennings, Palacios, Tripcevich, Yépez Álvarez, Tripcevich and Vaughn2013). Nonetheless, salt’s social and economic role in early coastal societies has been assessed (e.g., Burger Reference Burger and Donnan1985; Prieto Reference Prieto2018; Quilter Reference Quilter1991).

This article presents an interdisciplinary study of salt exploitation beginning at least ∼5500 cal BP in the littoral of the Chicama Valley on the north coast of Peru (Figure 1). Archaeological research on human and environmental interactions in the area has documented a mixed economy of maritime fishers, shellfish collectors, and small-scale farmers at the public mound sites of Huaca Prieta and Paredones and at outlying domestic sites. Huaca Prieta is a large ritual and mortuary structure built between ∼7200 and 3800 cal BP, located on the south end of a remnant Pleistocene terrace overlooking the Pacific Ocean (Figures 1 and 2a; see Dillehay and Bonavia [Reference Dillehay, Bonavia and Tom2017a] for details on 14C assays for the archaeological and geological sites discussed here). All assays were calibrated using the SHCal20 calibration dataset (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Heaton, Hua, Palmer, Turney, Southon and Bayliss2020). Paredones is situated ∼600 m north of Huaca Prieta and dated between ∼6500 and 4000 cal BP. Numerous small domestic sites in the form of household mounds are scattered throughout the littoral and date from ∼7700 to 4000 cal BP (Dillehay and Bonavia Reference Dillehay, Bonavia and Tom2017b). Two domestic sites are of interest here: BR-1, situated on the north edge of the remnant terrace (Figure 2b), and S-18, located a few kilometers to the north (Rosales Tham and Dillehay Reference Teresa and Dillehay2023).

Figure 1. Location of study area showing Huaca Prieta and BR-1 on the remnant Pleistocene terrace and S-18 farther north. Salt ponds and archaeological sites discussed in the text are located between the ocean shoreline and the inland dark line (image from Google Earth). (Color online)

Figure 2. (a) Huaca Prieta mound; (b) BR-1 domestic mound; (c, d) rectangular-shaped archaeological wells and ponds dating to at least 4000–2500 cal BP and possibly associated with salt extraction. (Color online)

Archaeological evidence reveals salt-storage pits at Huaca Prieta and manufactured salt disks at Huaca Prieta, BR-1, and S-18 (Rosales Tham and Dillehay Reference Teresa and Dillehay2023). Small amounts of amorphous-shaped chunks of salt also were found at these sites and at Paredones. The presence of caches, disks, and chunks suggests that extraction was carried out as part of the technological and economic exploitation of newly available resources (e.g., wetlands, salt) associated with a slow sea-level rise and a reduced rate of coastal environmental change within the littoral after ∼7500 cal BP (Goodbred et al. Reference Goodbred, Beavins, Ramirez, Pino, Oliveira Sawakuchi, Latorre, Dillehay and Tom2017, Reference Goodbred, Dillehay, Gálvez Mora and Oliveira Sawakuchi2020). At that time, slow transgression allowed natural evaporite deposits to form in shallow back-dune ponds and lagoons. The persistence of these coastal environments presented an opportunity for local inhabitants to harvest and process marine salts for local consumption and likely to participate in long-distance exchange for exotic cultigens, minerals, and other resources.

Environmental and Cultural Background

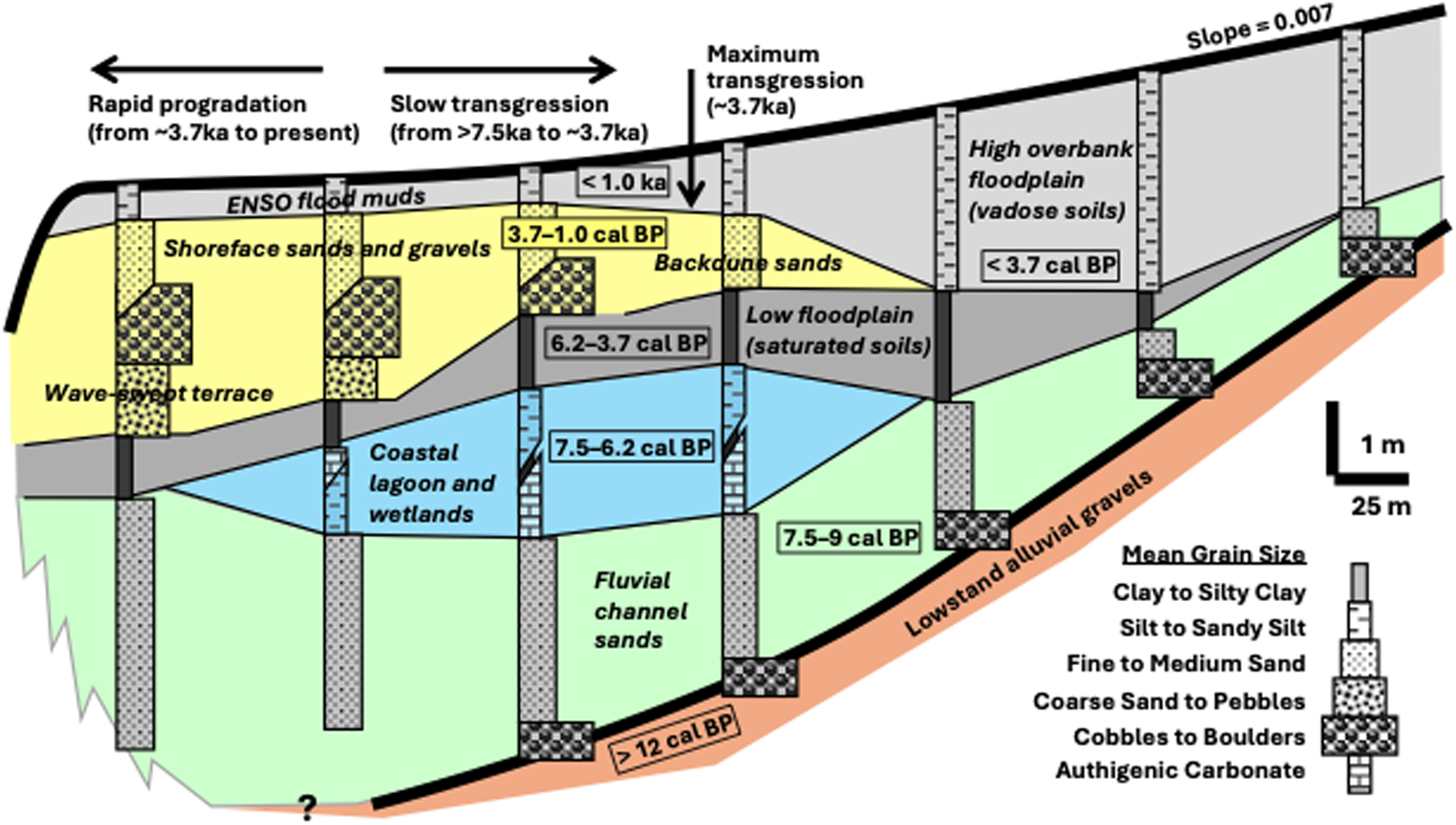

From ∼7500 to 6500 cal BP, rising sea levels and coastal transgression supported shallow, open-water ponds and lagoons behind the gravel shoreface and coastal dune systems (Goodbred et al. Reference Goodbred, Beavins, Ramirez, Pino, Oliveira Sawakuchi, Latorre, Dillehay and Tom2017, Reference Goodbred, Dillehay, Gálvez Mora and Oliveira Sawakuchi2020). Such wetlands and lagoons likely existed before ∼7500 cal BP but would have been persistently transgressed under more rapid sea-level rise at that time (Figure 3). Along the southern coast near the river delta and south of Huaca Prieta, these lagoons were primarily oligohaline (<5 ppt) as reflected by Typha grass peats and biogenic carbonate production from fresh/brackish charophyte algae, Cypridea ostracods, and Lymnaea gastropods (Goodbred et al. Reference Goodbred, Beavins, Ramirez, Pino, Oliveira Sawakuchi, Latorre, Dillehay and Tom2017). These environments were groundwater influenced (i.e., high bicarbonate, HCO3–) with low salinities. They would not have been suitable for salt extraction, and we have not identified any salt deposits south of the river. However, north of the delta along the coast from the remnant Pleistocene terrace up to Punta Malabrigo, the freshwater supply is limited, and shallow lagoons and wetlands are more saline (Figure 1 shows the area within the blackline from the shoreline to the interior). The reduced freshwater input along this reach of the shoreline, coupled with the permeable sand-and-gravel coastal and alluvial sediments, favored the intrusion of seawater into coastal groundwater.

Figure 3. Schematic cross-section of coastal stratigraphy at the Chicama River mouth showing the major depositional settings, general ages of deposition, and corresponding coastal dynamics (image modified after Goodbred et al. Reference Goodbred, Beavins, Ramirez, Pino, Oliveira Sawakuchi, Latorre, Dillehay and Tom2017). (Color online)

In the area today, shallow ponds and wetlands are saline and form thin evaporite beds during arid phases. Some of these near-surface evaporites have been dated to ∼2400 cal BP (see Goodbred et al. Reference Goodbred, Dillehay, Gálvez Mora and Oliveira Sawakuchi2020:Figure S5), but no earlier in situ salt deposits (∼6000–3000 cal BP) have yet been discovered. This absence of older deposits may be a consequence of shoreline transgression, which persisted from the initial phases of marine influence ∼7000 cal BP until at least 3500 cal BP, after which the regional shoreline position stabilized or even regressed (prograded) where there was sufficient sediment supply (Figure 3; Goodbred et al. Reference Goodbred, Beavins, Ramirez, Pino, Oliveira Sawakuchi, Latorre, Dillehay and Tom2017, Reference Goodbred, Dillehay, Gálvez Mora and Oliveira Sawakuchi2020; see Galsa et al. Reference Galsa, Tóth, Szijártó, Pedretti and Mádl-Szőnyi2022). It is estimated that the same relict environments that are exposed along the littoral north of the river today (dating at least 2,500 years ago or older) are similar to those from which the archaeological salts were likely derived between 6,000 and 5,000 years ago.

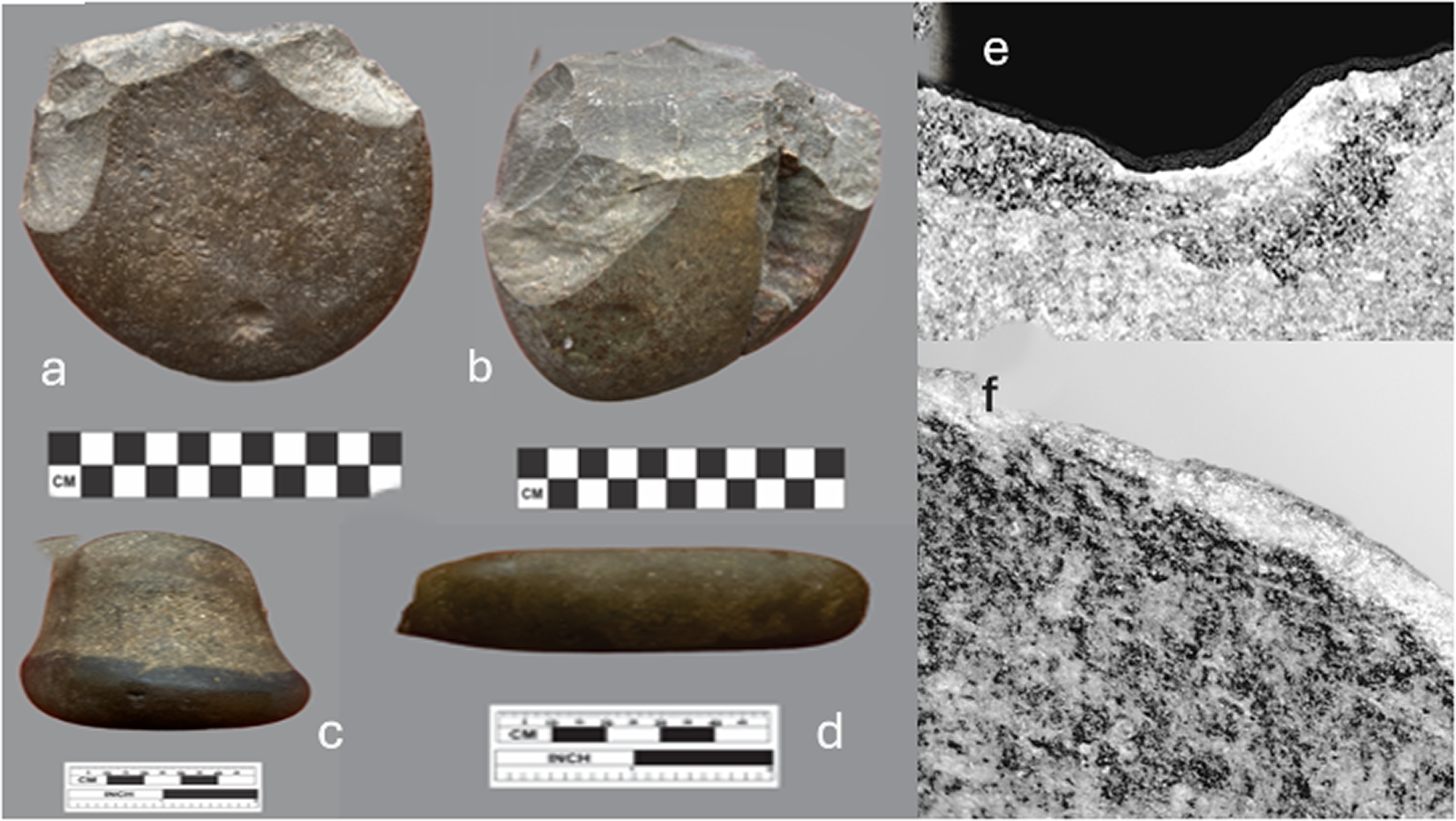

In addition to natural ponds and wetlands, there are artificially constructed ones dating to at least the Late Middle Holocene period (Figure 2c, d; see Parsons [Reference Parsons1968] for a discussion of artificial ponds or mahamaes and their uses and ages on the Peruvian coast). These are roughly rectangular shaped, with sizes ranging from ∼10 × 20 to about 20 × 30 m and from ∼2 to 5 m in depth. The chronology of one geologically cored pond (Figure 2d) is indicated by a radiocarbon date of 3552 ± 26 uncalibrated BP and 3887–3694 calibrated BP (D-AMS 048493 at a 95.4% confidence level) on charcoal from the interior wall of an early diagnostic Guañape ceramic found in a sediment layer stratigraphically located 10 cm above a salt stratum at 2.2 m in depth (Dillehay and Bonavia Reference Dillehay, Bonavia and Tom2017b). The presence of salt incrustations on the interior vessel walls of early Formative (i.e., Cuspisnique) to Late Intermediate period (i.e., Chimu) ceramics (∼3,200–600 years ago) and on the edges of various stone tools (e.g., choppers, axes, grinding stones, large unifacial, primary flakes; see the later discussion) recovered in and around the ponds suggests their use as salt extraction areas. Micro-use wear studies of the worked edges on several stone choppers and large flakes reveal minor hinge fracturing and striae from chopping and scraping, respectively, and thick linear clusters of salt crystals, suggesting their use for salt extraction; on the arid Pacific coast, salt crystals often appear on bone, wood, and other artifacts but not in linear concentrations along only the worked edges of stone tools and in thickly caked layers on only the interior walls of vessels.

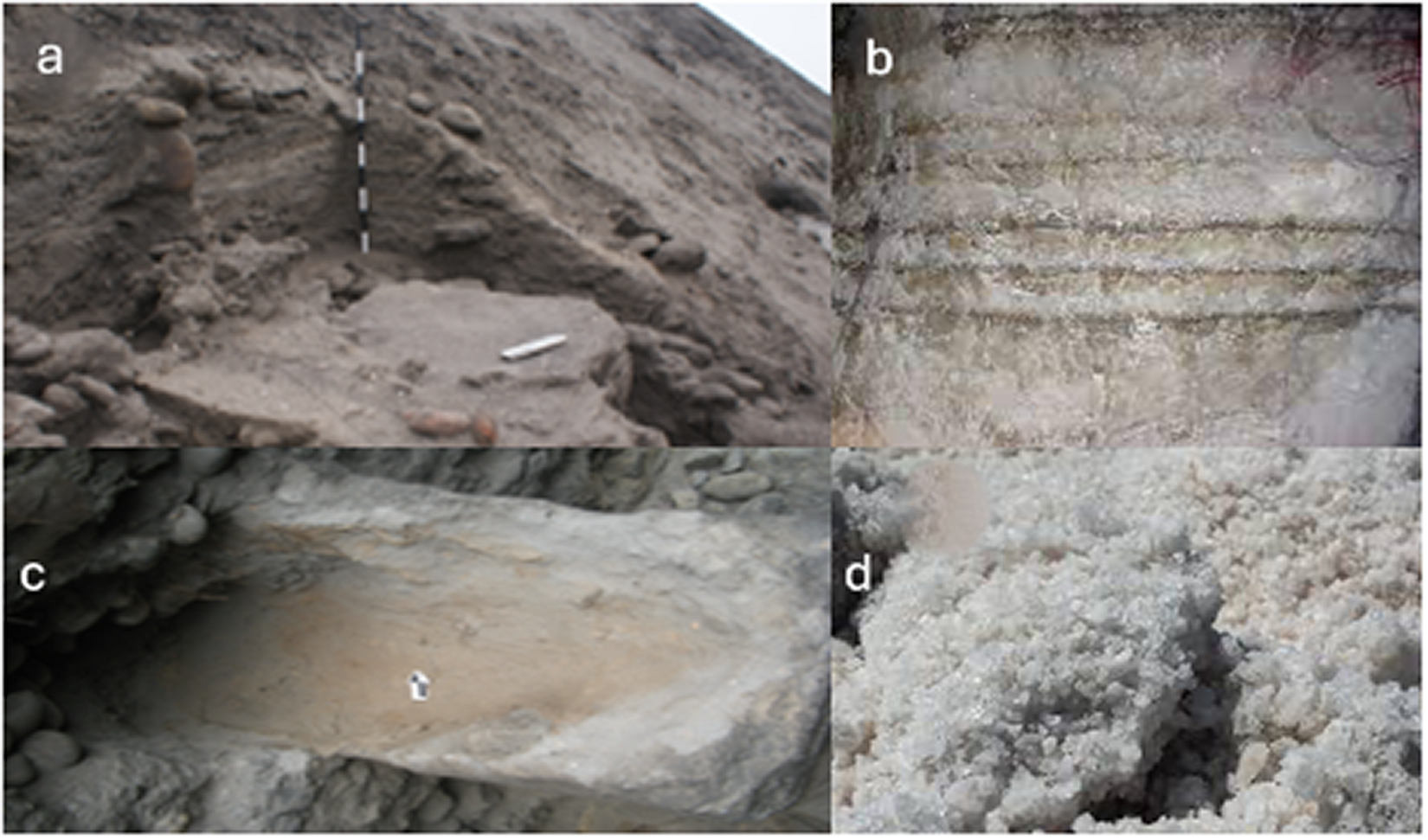

As part of our study, we conducted ethnographic interviews with local fisherfolk to understand how people today procure and use salt. Informants report two techniques to extract salt. One is to excavate below the ground surface by hand or heavy machinery, creating shallow, wet, muddy flats exposed to solar evaporation (Figure 4a–c). The salt usually is soft, wet, malleable, and grainy. People allow the water to evaporate into salt and then harvest it by scraping the salty soil and leaching the material to obtain liquid brine, which they pour into ceramic or metal containers for further evaporation and drying. The other method involves chopping or chipping off hard chunks of salt once the exposed layers are dry. If slightly moist, the chunks are stored temporarily in piles for additional drying (Figure 4d). When asked why salt still is extracted today, given that it can be purchased in local stores, informants claim that sea salt is tastier and more nutritious than commercial salt. Today, a few locals still exchange sea salt with upvalley friends and relatives for fruits and other products. They also state that before motorized vehicles were available, salt and dried fish and shellfish were transported to communities on the western slopes of the Andes by mules and horses in exchange for fruit, potatoes, and other products.

Figure 4. (a–c) Modern-day exposure of flat, low-lying wetlands exposing salt layers; (d) modern-day cache of drying salt chunks chipped from a dried layer. (Color online)

In the Andean worldview, it is recognized that salt, like living beings such as plants and animals, must be grown and cultivated (Espinoza Soriano Reference Espinoza Soriano1984; Tibesar Reference Tibesar1957; Verese Reference Verese2006). In the case of saltwater in natural depressions or artificial ponds, sowing must take time for the liquid brine contained in vessels to complete its maturation and drying, and only then can it be harvested (Miranda Reference Miranda2022; Tibesar Reference Tibesar1950). Although these activities still take place today in parts of the Andes and nearby western Amazonia (Brown and Fernández Reference Brown and Fernández1991; Ochoa Reference Ochoa2016; Petersen Reference Petersen, Craig and West1994, Reference Petersen2010), it is not well known how far back in time they extend. Unlike faunal and floral foods that often are preserved in archaeological sites, salt—if once present—likely dissolved or was consumed, leaving few if any traces (see Brigand and Weller Reference Brigand and Weller2015), especially in the humid Peruvian highlands where preservation is less likely. One of a few highland archaeological salt finds is reported in the vicinity of the Huar Huar salt mine in the Cotahuasi Valley where Jennings and colleagues (Reference Jennings, Palacios, Tripcevich, Yépez Álvarez, Tripcevich and Vaughn2013) found several chunks at looted Middle to Late Horizon tombs (∼1,200–500 years ago). They believe that their presence in tombs suggests the symbolic significance of salt. We know that salt, known as “white gold” to the Inkas, played an important role in their daily lives and economic structure. Harvested from the Maras and other salt mines near Cuzco (Beltran Reference Beltran, Alexianu, Curcă, Weller and Dumas2023; Palomino Meneses Reference Palomino Meneses1985), salt was used by the Inkas not only for seasoning their food but also for preserving it in the high-altitude climate. In the mid-1600s, the Spanish priest Bernabe Cobo (Reference Cobo1964 [1653]:83; our translation) wrote that the people of Peru used salt “since even the cured meat they made and the fish they dried . . . were without a grain of salt.” He remarked that people did not put salt on food but placed a large lump next to their plates, licking it frequently to give more flavor to the palate rather than the food.

Although salt was extracted from the dry playa basins of the high Andes, coastal salt was more prized and regularly exchanged along with dried fish and shellfish, exotic shells, stingray spines, seaweed, and other marine resources for highland exotic minerals, camelid wool dyes, domesticated crops (e.g., quinoa, potato, oca), and other items (see Burger Reference Burger and Donnan1985:276–277; Dillehay Reference Dillehay2001; Murra Reference Murra and de Zúñiga1972; Rostworowski de Diez Canseco Reference Rostworowski de Diez Canseco1977:244–253, Reference Rostworowski de Diez Canseco1981). On the north coast of Peru, Flores-Galindo (Reference Flores-Galindo1981:162) and Glave (Reference Glave1991:504) discuss salt produced by evaporation and early colonial women salting fish for local consumption and exchange, activities that still exist today (see the later discussion). For the Chicama Valley, Ramirez (Reference Ramirez, Prieto and Sandweiss2020:408, 412, 418) refers to early archival materials that reference salt pans located near the sea and to the socioeconomic dynamics between specialized fisherfolks and farmers on the coast.

Archaeological Evidence for Middle Holocene Salt Production

Two caches of salt in the form of semi-rectangular pits were excavated on the southwest base of the Huaca Prieta mound. The stratigraphic context of the pits is associated with intact cultural layers dated between ∼5200 and 5000 cal BP (Dillehay and Bonavia Reference Dillehay, Bonavia and Tom2017a). Amorphous-shaped salt chunks and fragmented disks with curved and rounded edges were also recovered at the site and dated between ∼5500 and 4000 cal BP. BR-1 is a household mound where salt chunks and complete and fragmented disks were dated between ∼5500 and 4000 cal BP. S-18, dated between ∼7000 and 4500 cal BP, also yielded a few salt chunks and disk fragments.

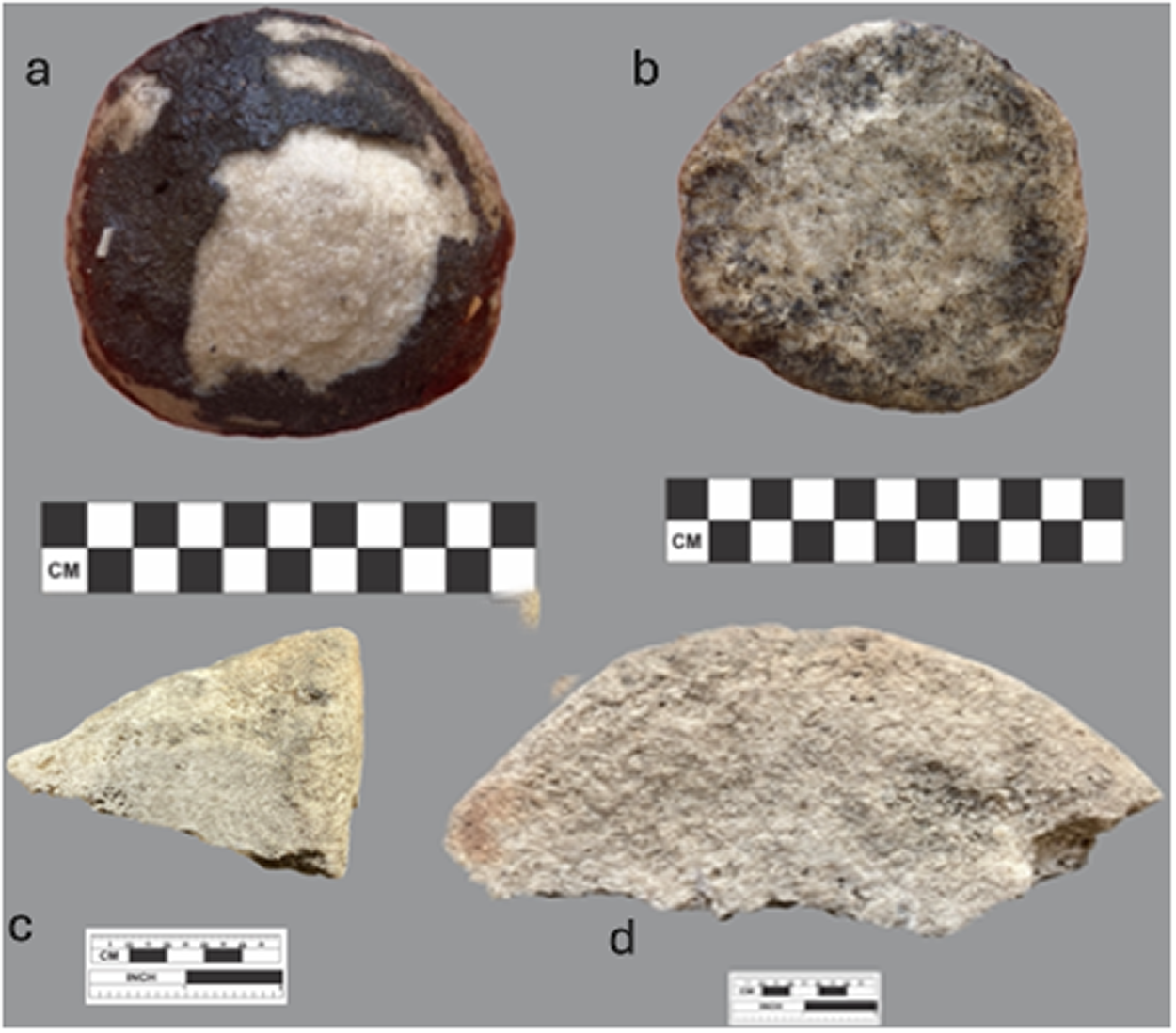

The salt pits at Huaca Prieta measured ∼1.2 × 2.2 × 1.2 m and ∼1.3 × 1.2 × 1.3 m (Figure 5a, b, respectively) and contained wet to moist laminated and unlaminated layers of salt and amorphous-shaped fragments (∼3.0 × 8–10 cm; Figure 5c, d). The wetness of the pits is due to their location on the windward or west side of the mound at the present-day sea level. The Pacific shoreline today is ∼ 70 m from Huaca Prieta. In the past, its distance varied according to sea-level changes but apparently was never more than ∼200–250 m away (Goodbred et al. Reference Goodbred, Beavins, Ramirez, Pino, Oliveira Sawakuchi, Latorre, Dillehay and Tom2017; Pino Reference Pino and Tom2017). Fine screening of cultural deposits throughout the mound yielded small to moderate-size salt chunks (∼1.0 × 3.1 cm to 5.0 × 8.0 cm) and disk fragments (∼2.0 × 4.0 cm and 4.0 × 6.0 cm).

Figure 5. (a, b) Salt storage pits excavated at Huaca Prieta; (c) laminated salt layers; (d) stored, malleable, grainy salt from an unlaminated layer. (Color online)

BR-1 is a small domestic mound characterized by several intact cultural layers, each comprising a series of hardened occupational floors containing an abundance of marine fauna, lithic tools, plant foods (including wild and domesticated species), hearths, wood implements, and fragments of mineralized polychaete tubes (i.e., nest of marine annelid worms). Five complete and large fragments of salt disks were recovered from the lower Levels 13 and 14, the latter dated by hearth charcoal of a short-lived bush (Gossypium sp.) to 4730 ± 29 uncalibrated BP and 5573–5529 calibrated BP (D-AMS 048496 at the 95.4% confidence level). Radiocarbon dates from overlying cultural strata ranged between 5230 and 3540 cal BP (D-AMS 048494, 048497, 048495; Rosales Tham and Dillehay Reference Teresa and Dillehay2023) and were in chrono-stratigraphic sequence with Layer 14. The disks range in size from ∼8.1 to 25.0 cm in diameter and ∼3.2 to 5.0 cm in thickness (Figure 6a–d). Nearly all strata in the site contained small to moderate-size disk fragments (∼1.0 × 3.0 cm to 4.0 × 6.0 cm), stone tools with salt crustations on the worked edges (Figure 7), and amorphous-shaped salt flakes (∼2.0 × 6.0 cm; Figure 8a, b).

Figure 6. Archaeological disks from site BR-1: (a, b) complete disks; (c, d) fragmented disks. (Color online)

Figure 7. (a–d) Various stone tools recovered from the archaeological ponds and the deeper levels at BR-1; (e–f) micro-use wear and salt crystals on the whorled edges of stone flakes recovered from the archaeological ponds and BR-1, presumably used to shape disks. (Color online)

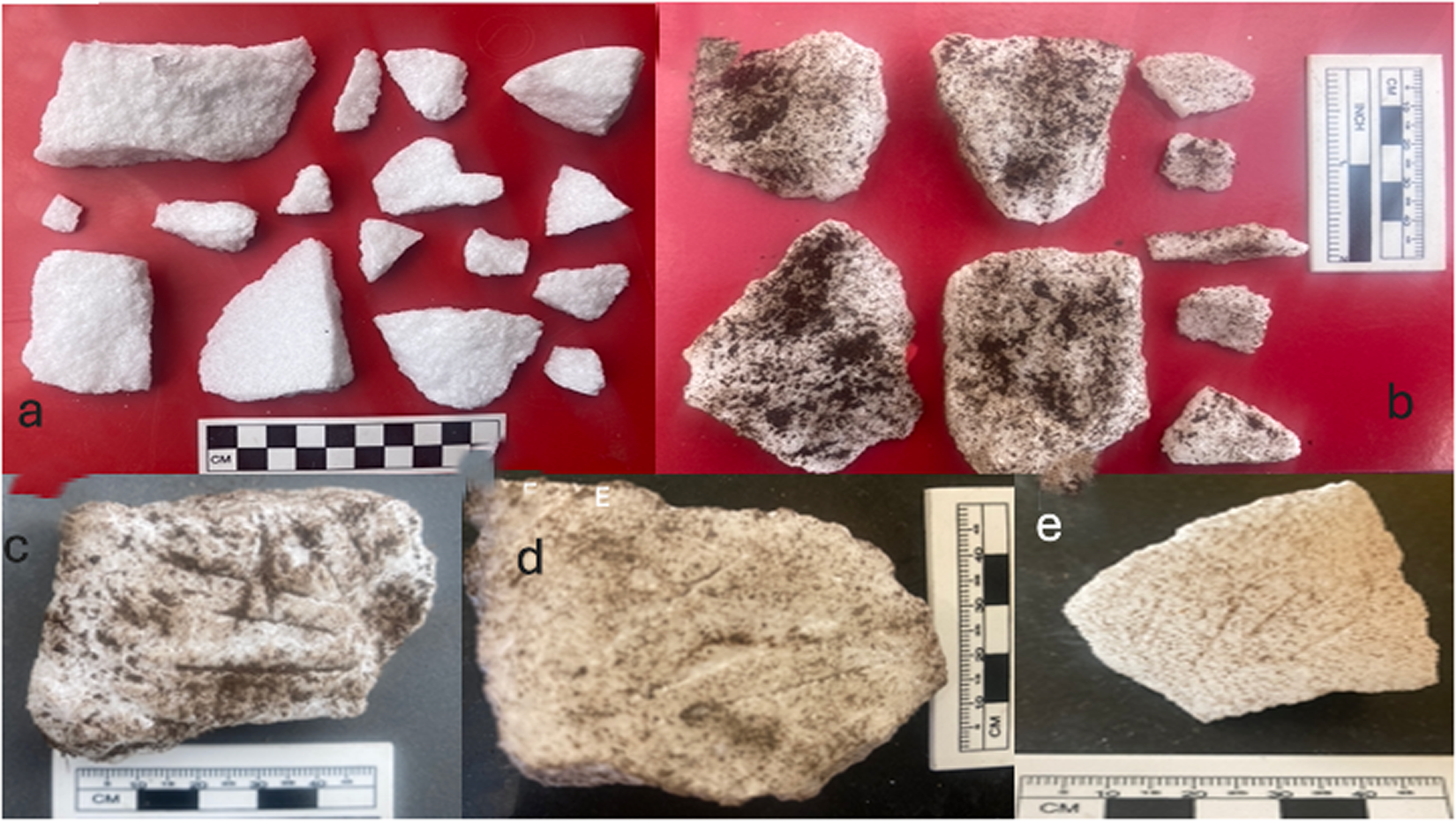

Figure 8. Amorphous-shaped salt chunks: (a) cleaned salt chunks from storage pits at Huaca Prieta, revealing shape and surface characteristics; (b) uncleaned chunks from BR-1 and S-18; (c–e) uncleaned chunks from Huaca Prieta and BR-1 showing flake scars and maker striae. (Color online)

Two complete disks (Figure 6a, b) are double convex and measure approximately 8.1 cm and 10.0 cm in diameter and ∼3.5 cm in thickness, and weigh 712 and 890 g, respectively. Based on their measured circumference, it is estimated that, if complete, their diameters fall into three ranges—7–9 cm, 9–10 cm, and 12–13 cm—perhaps roughly suggesting standard sizes. The large fragment shown in Figure 6d has an estimated diameter of ∼29–30 cm; it is 4.2 cm in thickness. Both the complete and fragmented disks reveal micro-flake scars and striae indicative of deliberate manufacture in variable sizes (Figure 8c–e). The size, curvature, and thickness of the disk fragments range from ∼8.1 to 30.0 cm in diameter and ∼3.2 to 5.0 cm in thickness. Amorphous-shaped flakes are roughly 3.0 × 6.3 cm in size and 2.2–5.3 cm in thickness. There also are numerous small salt fragments (<2 cm) scattered throughout the strata. Micro-use wear and residue analysis of the edges of several large unifacial flakes and choppers reveal the presence of salt crystals like those shown in Figure 7e, f. Given the quantity and diversity of salt forms and the association of stone tools with salt crystals on worked edges, BR-1 likely functioned as both an occupational locale and a salt workshop.

Another domestic site is associated with small salt chunks (<2 cm) and disk fragments (<3.2 cm) but not of the diversity and quantity recorded at BR-1. S-18 yielded eight amorphous-shaped chunks (∼3.1–5.0 cm) and two small disk fragments (<4.2 cm). The deepest stratum (F-15) contained the disk fragments, and it yielded an OSL assay of ∼7000 ± 630 years ago (Chamberlain Reference Chamberlain2019; Dillehay et al. Reference Dillehay, Tham, Vázquez, Goodbred, Chamberlain and Rodríguez2022; Rosales Tham and Dillehay Reference Teresa and Dillehay2023). Wood charcoal from a hearth in the same stratum dated to 7162–6914 cal BP (AA75398; see Dillehay et al. Reference Dillehay, Tham, Vázquez, Goodbred, Chamberlain and Rodríguez2022), suggesting that salt might have been produced earlier. However, the current evidence and sample size from the site are insufficient to substantiate salt extraction before ∼5500 cal BP. As mentioned, salt is a food that likely was consumed completely and is highly dissolvable and nearly invisible archaeologically (Brigand and Weller Reference Brigand and Weller2015). It is not expected to be frequently found at archaeological sites, except perhaps as ritual or tomb offerings or preserved in certain favorable environmental contexts such as those discussed here.

Although salt is a resource for exchange and food preservation and consumption, there currently is no archaeological evidence to confidently assess the social, symbolic, and religious value of salt during the Middle Holocene. Of the project’s 10 excavated public and domestic sites dated to that period, only four contained salt remains. Salt also was not reported at two other Middle Holocene sites in the littoral, Cruz Verde (Shoji et al. Reference Shoji, Flores Vásquez and Rosales2023) and Pulpar (Hirota Reference Hirota2010). Nor have salt offerings been documented in early tombs at sites in the area (e.g., Bird et al. Reference Bird, Hyslop and Skinner1985; Dillehay Reference Dillehay2017). Because salt was not recovered at every excavated site (presuming no sampling bias), it is reasonable to hypothesize that only certain families or communities extracted, produced, and exchanged it. This is a reasonable conjecture, given that specialized fisherfolks and farmers coexisted in the area around 6500 cal BP and thereafter (Dillehay Reference Dillehay2017; Dillehay et al. Reference Dillehay, Tham, Vázquez, Goodbred, Chamberlain and Rodríguez2022; Tung et al. Reference Tung, Dillehay, Feranec and DeSantis2020; for later periods, see Flores-Galindo Reference Flores-Galindo1981:162; Glave Reference Glave1991:504; Ramirez Reference Ramirez, Prieto and Sandweiss2020:408, 412, 418). Given the absence of evidence for salt production at most domestic sites and the specialized dual economies and apparent textile and basketry weaving techniques that existed in the lower valley during the Middle Holocene, it is possible that specialized salt producers operated at the household level and were predominantly women (for discussion of salt in coastal Peru, see Prieto Reference Prieto2018; Quilter Reference Quilter1991; Ramirez Reference Ramirez, Prieto and Sandweiss2020; Rostworowski de Diez Canseco Reference Rostworowski de Diez Canseco1960, Reference Rostworowski de Diez Canseco1977, Reference Rostworowski de Diez Canseco1981; Sandweiss Reference Sandweiss1992, Reference Sandweiss1996).

Salt Disks

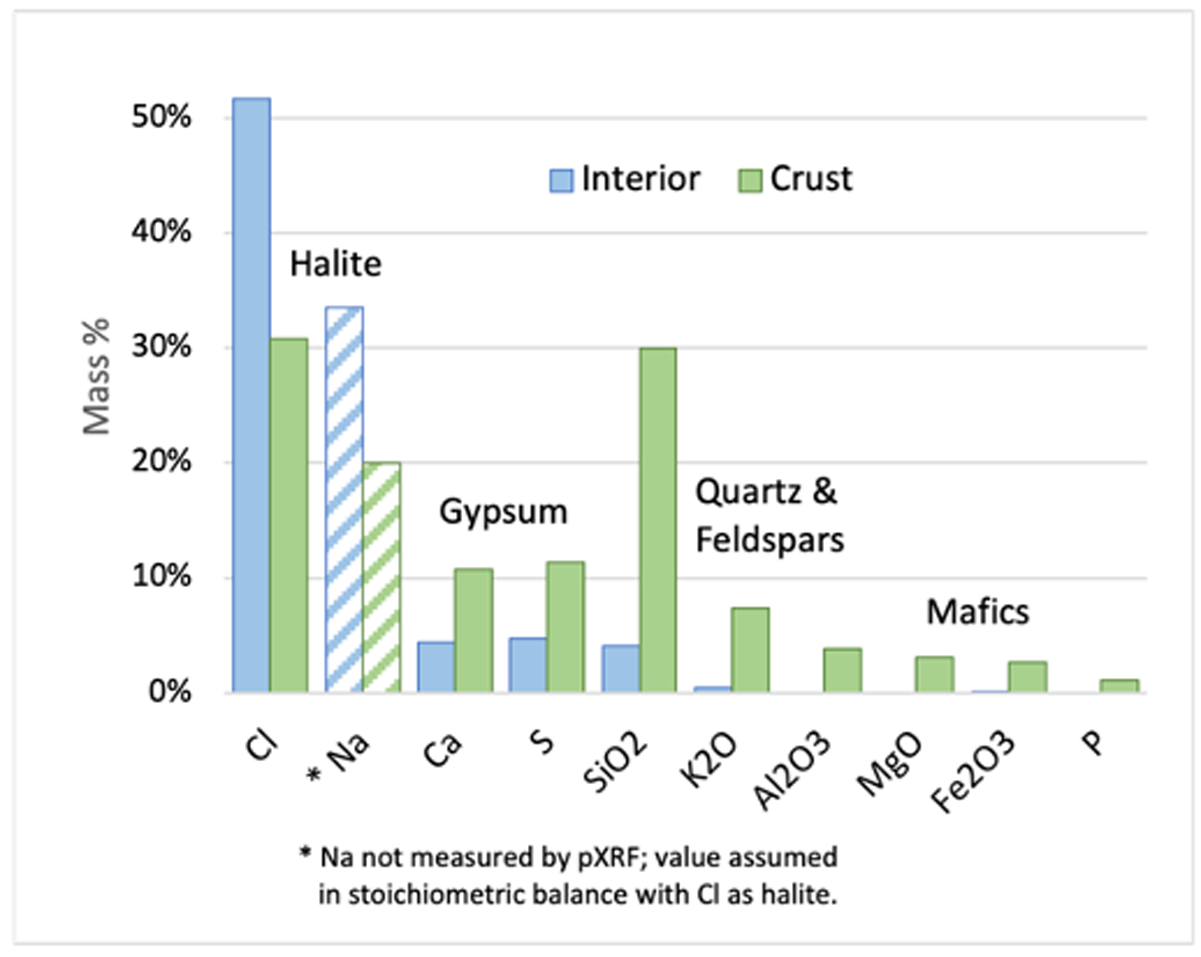

The archaeological salt disks resist dampness well: the hygrometric effect is limited to the surface and does not alter the interior crystals. We analyzed the geochemistry on the salt crust and interior of the disk shown in Figure 6a for two minutes using a portable XRF (ThermoNiton XL3t) calibrated to sediment standard NIST 2709a. The interior disk composition was dominated by Cl with significant proportions of Ca and S (Figure 9). Na cannot be measured on a portable XRF because of atmospheric interference, but it can be assumed to be stoichiometrically balanced with Cl, based on the predominance of halite (NaCl) crystals in the sample. In addition to halite, there are stoichiometrically balanced concentrations of Ca and S that indicate an abundance of gypsum (CaSO4). With NaCl and CaSO4 as the most abundant minerals, the archaeological disks are clearly of seawater origin and not from estuarine or groundwaters that would have had measurable, if not dominant, carbonate minerals relative to seawater-derived gypsum and halite. The crust of the salt disk had a similar composition but a higher concentration of Si and Al. These were in typical ratios for quartz, feldspars, and micas, so the non-seawater contribution seems to be from sands and silts that adhered to the exterior from the surrounding environment.

Figure 9. Results of XRF analysis of archaeological disk from BR-1 shown in Figure 6a. (Color online)

The weights and sizes of the two complete disks shown in Figure 6a, b imply that each kilogram of salt would have required approximately 30 times that mass in seawater to have precipitated each (100 kg × 28.5 = ∼3,000 kg of seawater), assuming typical 33–35 ppt salinities. Therefore, producing tens to hundreds of kilograms of salt (or more) would require tons of seawater, which seems unlikely to have been transported by hand using containers made from animal skins or other materials in the Middle Holocene period. More likely, numerous, shallow, salt-precipitating ponds were episodically connected to the shoreline and allowed repeated infilling and evaporation of seawater. This is plausible given that the regional shoreline continued to slowly transgress landward until ∼3,500 years ago, and the shoreline would have been substantially closer to the evaporative ponds before this time. Shoreline transgression continued at this time due to insufficient fluvial sediment delivery and not sea-level rise, which was relatively slow (Goodbred et al. Reference Goodbred, Beavins, Ramirez, Pino, Oliveira Sawakuchi, Latorre, Dillehay and Tom2017, Reference Goodbred, Dillehay, Gálvez Mora and Oliveira Sawakuchi2020). This trend reversed after ∼3,500 years ago when the coastal sediment supply increased because of enhanced ENSO-related discharge (e.g., Conroy et al. Reference Jessica, Overpeck, Cole, Shanahan and Steinitz-Kannan2008; Moy et al. Reference Moy, Seltzer, Rodbell and Anderson2002). It is also conceivable that these connections were sustained by human action such as digging and controlling seawater ingression via small canals, much as water-diversion structures were used along inland streams for horticulture. However, to date no such structures have been identified in the study area.

In addition to complete disks, 74 disk fragments were recovered from Huaca Prieta, BR-1, and S-18. Some might have been deliberately broken for local consumption or by on-site taphonomic forces such as trampling, diagenesis of sediments, and other mechanical variables. However, it is likely that the small amorphous-shaped salt chips and chunks found at sites were primarily for local consumption, whereas symmetrically produced disks probably were used less for local consumption and more for exchange for highland products. It is unlikely that local manufacture and use would have required disks of different sizes and in consistently rounded and curved forms. Local use would suggest instead a customary manner of scraping and eating salt, which likely would not lead to discarding a symmetrical disk, which seems illogical and unnecessary anyway. Indeed, informants believe that disks were produced only for exchange; one of them claimed that in the early 1900s his grandfather made square salt cakes for exchange with inland coastal and highland people.

It is likely that the form and size of some disks resulted from measured portions of moist, friable salt (i.e., liquid brine) being poured into gourd containers, which had relatively set ranges of dimensions. Some disk fragments have plano-convex surfaces, with the convex side conforming to the curvature of small gourd bases. The base diameters of these gourds range between ∼8.5 and 13.2 cm, which generally conforms to the estimated diameters of complete and fragmented disks. Some gourds excavated at Paredones, Huaca Prieta, and BR-1 also exhibit thick salt incrustations on their interior base walls, suggestive of disk manufacture. Moreover, plano-convex disks rarely reveal reductive chipping flakes and micro-striae resulting from scraping and manufacture (Figure 8a, b). The presence of flaking and scraping marks on double-convex disks suggests that they likely were manufactured by hand and deliberately shaped into disks (Figure 8c–e). Of the present sample of 74 complete and fragmented disks, 48 show flaking and scraping marks. Without more evidence, it is difficult to determine the extent to which these two manufacturing processes were more often used, but it appears that plano-convex disks were shaped by brine evaporation in gourds and double-convex disks were formed by flaking and scraping.

Were salt disks used possibly as a unit of measurement or accounting for long-distance exchange? We know that in late pre-Inka and Inka times various types of metrics were used to produce and exchange resources (e.g., Gudemos Reference Gudemos2011; Lechtman Reference Lechtman1984; Llerena Reference Llerena2003; Rostworowski de Diez Canseco Reference Rostworowski de Diez Canseco1960, Reference Rostworowski de Diez Canseco1981; Urton Reference Urton1997). Because salt has rarely been reported from interior coastal and highland archaeological sites because of the lack of preservation, its archaeological recognition, and the screening of excavated cultural deposits, it is difficult to demonstrate that it was a regular exchange commodity. However, the presence of numerous and diverse exotic resources at Huaca Prieta, Paredones, and domestic sites (Dillehay and Bonavia Reference Dillehay, Bonavia and Tom2017b), including ∼40 cultigens, 15 minerals, and five shells from distant highland and coastal areas, suggests that local marine products, including salt, were exchange items. If salt was exchanged, it is not known whether it had an approximate range of standard measurement. We can ask why product disks were made? If salt was exchanged over long distances, it was probably carried in reed, leather, or cotton containers. The types of chips shown in Figure 8 would fracture and chip easily, if transported long distances. Perhaps their form and the thick, rounded edges of disks made them less susceptible to transport damage.

Did other archaeological indicators exist during the Middle Holocene that suggest the standardized use of numbers, measurements, or proportions? A squarish device with 20 small circular depressions (4 × 5 rows), which was associated with two spheroid stones in the tomb of an adult male at Unit 16 near Huaca Prieta, may have been used as a gaming or counting instrument (Dillehay and Bonavia Reference Dillehay, Bonavia and Tom2017b:453). Also at Huaca Prieta, hundreds of deliberately torn textiles were placed in tombs, in bundle offerings, and on ritual floors, some of which seem to represent a crude unit of measurement, ranging between ∼10–20 cm and 15–25 cm in size (Splitstosser Reference Splitstosser and Tom2017). Most of the textiles are relatively small, which aligns with them having been made on frame looms. A cursory inspection of fabrics with two weft selvages (i.e., those with complete widths), of which only 10 were analyzed in detail, revealed that they tend to range in widths that are multiples of 10 cm. There is less evidence for a standard length, but preliminary data suggest a preference for units of about 8 cm (Jeffrey Splitstosser, personal communication 2024). The use of metrics also is suggested by the presence at Huaca Prieta of imported green schist and skarn cobbles from Ecuador that exhibit either 8 or 10 black or red circles (Dillehay and Bonavia Reference Dillehay, Bonavia and Tom2017b:447) and of ritual offerings of 10 coca leaves placed in tombs and on ritual floors and paths. These devices and offerings date roughly between 6000 and 4500 cal BP. However, further investigation and more evidence are required before any conclusions can be drawn about consistent and formal applications of standardized units of salt and other commodity production and measurement.

Conclusions

During the Middle Holocene, salt was extracted from wetlands along the littoral of the Chicama Valley and made into disks and other forms for local consumption and probably exchange. For this study, we analyzed salt caches, disks, and chunks from several archaeological sites, including two public mounds and two domestic localities. The presence of different sizes of disks suggests that they may represent standardized units of production for long-distance exchange by at least ∼5,500 years ago. The development of standardized disks would not be surprising, given that this was when Huaca Prieta flourished as a centralized public place, with a wide variety of exotics likely resulting from pilgrimages or product exchange with distant coastal and highland groups (Dillehay Reference Dillehay2017); at a slightly later time, new irrigation, weaving, and other technologies and large-scale public monuments and agricultural communities were developing in north coast valleys (Fuchs et al. Reference Fuchs, Patzschke, Yenke and Briceño2009; Vega-Centeno Reference Vega-Centeno and Vega-Centeno2017).

Salt is one of the oldest and most ubiquitous food condiments and tanning agents in the world. The various salt extraction, manufacturing methods, and uses observed worldwide are linked to specific environmental contexts, types of saliferous resources exploited, and the specificities of local economic demand and social contexts. Placed in this broader context, the findings presented here are significant because they contribute to an empirical basis for understanding the early development of salt production and perhaps its long-distance exchange on the northern coast of Peru. They also underscore the usefulness of interdisciplinary analyses related to salt and its economic and social roles in the past.

Acknowledgments

Helpful comments and suggestions from anonymous reviewers are gratefully acknowledged. We thank the Ministerio de Cultura in Lima for granting us permission to carry out archaeological work in the Chicama Valley. We also are grateful to residents of Magdalena de Cao, Cruz Verde, and Milagro for sharing their knowledge of present-day salt production and other topics with us. Unless otherwise noted, all images and figures are courtesy of the authors.

Funding Statement

We thank the National Geographic Society, the National Science Foundation (2039136 and 2015676), Vanderbilt University, and anonymous contributors for funding this research.

Data Availability Statement

Permanent curation of the collection discussed here is the responsibility of the Ministerio de Cultura in Trujillo. The collection is housed at the Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.