Introduction

Nonprofit organizations (NPOs) contribute to the functioning of cities in manifold ways: they support administrations and communities in meeting societal challenges (Grønbjerg & Paarlberg, Reference Grønbjerg and Paarlberg2001). They further urban cohesion by fostering social relations among individuals and between citizens and organizations (McQuarrie & Marwell, Reference McQuarrie and Marwell2009), strengthening the social order in urban communities, contributing to city governance, and addressing ecological and societal challenges, such as integration and inequality (Vermeulen et al., Reference Vermeulen, Minkoff and van der Meer2016a, Reference Vermeulen, Laméris and Minkoff2016b).

Extant scholarship has typically considered the effects of social capital on local community development (e.g., Hishida & Shaw, Reference Hishida, Shaw and Shaw2014; Hommerich, Reference Hommerich2015; Hwang & Young, Reference Hwang and Young2022; Krishna, Reference Krishna2002; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998). Although NPOs have been acknowledged in their capability to produce social capital (e.g., Mutz et al., Reference Mutz, Burrmann and Braun2022), the literature has overlooked NPOs’ capacity to link citizens with institutional actors beyond the immediate bonding within their community and the bridging between different communities (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000; Sampson, Reference Sampson1999; Trigilia, Reference Trigilia2001). However, as Brandtner and Laryea (Reference Brandtner and Laryea2021) argue, NPOs contribute to urban cohesion by engaging in two distinct forms of integration: social and systemic integration. The former refers to the fostering of bonds among citizens, the latter to the intermediation of individuals with institutional resources. Both forms of integration represent cornerstones of urban cohesion as they enhance organizational survival and a resilient social order (Vermeulen et al., Reference Vermeulen, Minkoff and van der Meer2016a, Reference Vermeulen, Laméris and Minkoff2016b; Wang & Vermeulen, Reference Wang and Vermeulen2020).

Despite the richness of scholarship on urban NPOs explaining their prevalence (Bielefeld, Reference Bielefeld2000; Van Puyvelde & Brown, Reference Van Puyvelde and Brown2016) and their contributions to social inclusion (e.g., Shier et al., Reference Shier, Handy and Turpin2022; Vandermeerschen et al., Reference Vandermeerschen, Meganck and Seghers2017), the full range of systemic integration has not yet been thoroughly considered (Marwell & Morrissey, Reference Marwell and Morrissey2020; Marwell et al., Reference Marwell, Marantz and Baldassarri2020). Particularly our knowledge of ‘how’ and ‘where’ NPOs contribute to both forms of integration remains scarce. We therefore augment Brandtner and Laryea’s (Reference Brandtner and Laryea2021) model of NPOs’ engagement in urban integration by analyzing how NPOs’ location and organizational practices relate with integration modes.

For one, location has substantial effects on how NPOs operate, as they often serve constituents in their immediate vicinity and depend on resources provided by local stakeholders (Wolpert, Reference Wolpert1993). In consequence, their contributions to urban cohesion vary across neighborhoods (Wu, Reference Wu2019; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Guo and Paarlberg2014), which can reinforce neighborhood disadvantages (Sampson & Graif, Reference Sampson and Graif2009).

In addition, NPOs’ engagement in integration is also shaped by organizing practices (Suykens et al., Reference Suykens, Maier and Meyer2022). In European cities, especially in those with a social democratic tradition, NPOs build on a long legacy of democratic forms of organizing based on participatory practices, volunteering and a strong membership base (Maier et al., Reference Maier, Meyer and Terzieva2022). However, with NPOs’ organizational practices shifting towards professional management (Hwang & Powell, Reference Hwang and Powell2009), NPOs’ capacity to integrate socially is being called into question (Eikenberry & Kluver, Reference Eikenberry and Kluver2004).

Distinguishing between managerialist and democratic forms of organizing (Maier & Meyer, Reference Maier and Meyer2011), we investigate their effects on NPOs’ engagement in social and systemic integration, and ask: (1) How do urban NPOs engage in social and systemic integration? (2) How does this engagement in social and systemic integration relate to characteristics of the local neighborhoods (per capita income, share of immigrant population, and organization density)? (3) How does this engagement relate to managerialism and organizational democracy? To test these effects, we use a unique dataset of NPOs from the city of Vienna, combining representative survey data of NPOs (n = 459) with geographically fine-grained administrative data at the level of the statistical grid unit (250 × 250 m).

Our study contributes in a twofold way. First, by addressing both the social and systemic integration of NPOs in urban contexts, we extend the understanding of the role of NPOs in creating social cohesion and neighborhood vitality beyond the provision of social capital (e.g., Hwang & Young, Reference Hwang and Young2022). We thereby also add to the scholarship on social and systemic integration (Archer, Reference Archer2007; Brandtner & Laryea, Reference Brandtner and Laryea2021; Esposito, Reference Esposito2020). Second, by zooming into the local context of NPOs, we illuminate the interplay between neighborhoods and NPOs’ contribution to urban cohesion. In addition, our study has also implications for urban policies concerned with promoting urban cohesion, e.g., in urban planning, urban development, and social service provision.

Theory and Hypotheses

Nonprofits’ Contributions to Social and Systemic Integration

In their role as drivers of urban cohesion, NPOs provide the space and practices to build social capital (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000) and nurture the development of local communities (Cagney et al., Reference Cagney, York Cornwell and Goldman2020; Klinenberg, Reference Klinenberg2015; Small & Adler, Reference Small and Adler2019). “‘Social capital’ refers to features of social organization, such as networks, norms, and trust, that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit” (Putnam et al., Reference Putnam, Leonardi and Nanetti1992: 6f), thereby constituting a necessary condition for community development (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998), providing the glue that makes collective action possible (Krishna, Reference Krishna2002). Social capital thus strengthens community identity and its welfare by enabling cooperation and the pursuit of common objectives (Putnam, Reference Putnam1995). For example, Hwang and Young (Reference Hwang and Young2022) showed the effects of social capital on local philanthropic engagement. Others highlighted the importance of social capital in disaster recovery by bringing NPOs and volunteers together (Hishida & Shaw, Reference Hishida, Shaw and Shaw2014; Kaltenbrunner & Renzl, Reference Kaltenbrunner and Renzl2019).

Research has distinguished bonding from bridging social capital (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000; Woolcock & Narayan, Reference Woolcock and Narayan2000). The first refers to the cohesion of social networks of homogeneous groups of people. This type of social capital enables collective agency, congregational unity, personal connections, and furthers a desire for homogeneity (Leonard & Bellamy, Reference Leonard and Bellamy2015). Especially in poor neighborhoods, close-knit ties allow communities to ‘get by’ (de Souza Briggs, Reference de Souza1998). The second concept–bridging–refers to the connections between socially heterogeneous groups, which is argued to help local communities to ‘get ahead’ (Barr, Reference Barr1998). Therefore, both bridging and bonding aspects of social capital contribute to social integration of neighborhood communities. However, as Sampson (Reference Sampson1999) noted, even if communities exhibit strong interpersonal ties, they might still lack institutional ties. This refers to a third facet of social capital, i.e., the linking of people with institutions, which corresponds to systemic integration (Small, Reference Small2009; Small et al., Reference Small, Jacobs and Massengill2008).

By creating bonding, bridging, and linking forms of social capital, NPOs are essential drivers of the social and systemic integration of communities. Social integration concerns face-to-face interaction and interpersonal exchange, and relates to membership and volunteering in local NPOs (Ruiz & Ravitch, Reference Ruiz and Ravitch2022). In contrast, systemic integration refers to impersonal mechanisms, e.g., bureaucratic rules or money (Marwell and McQuarrie, Reference Marwell and Gullickson2013), which characterize collaboration among organizations. These two concepts draw on Ferdinand Tönnies’ distinction between Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft (Tönnies, Reference Tönnies1887). Social integration concerns Gemeinschaft, i.e. the private sphere constituted by individual action, whereas systemic integration refers to functional systems such as politics and economy (Bohnen, Reference Bohnen1984; Habermas, Reference Habermas1981). Both spheres build an intertwined fabric of institutions typical for modern societies. However, as systemic integration is usually underpinned by power and money, Habermas (Reference Habermas1981: 267ff) warns that this may lead to reification and colonialization of the lifeworld.

In urban contexts, the interlocking of system and Lebenswelt yields a co-evolution of local communities and their organizations (Marquis & Battilana, Reference Marquis and Battilana2009; Walker & McCarthy, Reference Walker and McCarthy2010). As spaces are both “socially produced and simultaneously socially producing” (Dale & Burrell, Reference Dale and Burrell2008: 6), NPOs and their environment are mutually constitutive: NPOs rely on external resources, while local communities often depend on the services provided by NPOs (Bielefeld, Reference Bielefeld2000; Wu, Reference Wu2019). For example, areas with a low level of nonprofit engagement often suffer from low political participation (Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Robichau and Alexander2022; Hum, Reference Hum2010), poor community health (Joassart-Marcelli et al., Reference Joassart-Marcelli, Wolch and Salim2011), poor educational outcomes, and high crime rates (Sampson, Reference Sampson2012; Sampson & Graif, Reference Sampson and Graif2009). Therefore, neighborhoods exhibit specific needs and resources that determine NPOs’ capacity to integrate socially and/or systemically. Likewise, factors such as age distribution, immigrant population, and wealth may affect the prevalence and activities of NPOs (Grønbjerg & Paarlberg, Reference Grønbjerg and Paarlberg2001; Lu, Reference Lu2017). For example, Gilster et al. (Reference Gilster, Meier and Booth2020) showed that higher levels of neighborhood needs and organizational resources relate to more volunteering. Hence, in poorer neighborhoods NPOs often fulfill specific functions, which are connected to service provision and community building (Katz, Reference Katz2014; Peck, Reference Peck2007). We therefore theorize:

H1a

A low level of average income of citizens in a neighborhood has a positive effect on NPOs’ social integration.

Besides, the share of immigrants is likely to affect NPOs’ engagement in social and systemic integration. Vermeulen et al., (Reference Vermeulen, Minkoff and van der Meer2016a, Reference Vermeulen, Laméris and Minkoff2016b) found that a high immigrant population is negatively associated with the density and survival of voluntary leisure organizations. In contrast, the number of specific neighborhood foundations is higher in migrant neighborhoods due to demands of various ethnic groups (Vermeulen et al., Reference Vermeulen, Tillie and van de Walle2012), being confronted with specific needs and challenges such as financial pressure, settling and integrating in a new place (Joassart‐Marcelli, Reference Joassart-Marcelli2013; Vermeulen et al., Reference Vermeulen, Tillie and van de Walle2012). Apart from informal social networks of friends and family, NPOs are key providers of immigrant services and social integration (Schrover & Vermeulen, Reference Schrover and Vermeulen2005). Given that social integration builds upon interpersonal ties based on trust to reduce the social distance within the neighborhood (Hansmann, Reference Hansmann1987; Ray & Preston, Reference Ray and Preston2009), we theorize:

H1b

A higher share immigrant population in the neighborhood has a positive effect on NPOs’ social integration.

The nonprofit sector can be supplementary, complementary, or adversarial to a governmental agenda (Young, Reference Young2000). As the scope and scale of public services cannot be sufficiently addressed by governmental organizations alone, partnerships among multiple actors with various resources are required to tackle complex social issues and promote better public relations (Chisholm, Reference Chisholm1992; Gray, Reference Gray1989). Therefore, governmental organizations are inclined to partner with NPOs (Brinkerhoff, Reference Brinkerhoff2002; Huntoon, Reference Huntoon2001; Salamon, Reference Salamon1999). This is particularly true for corporatist countries like Austria, where public authorities tend to outsource welfare domains to NPOs (Salamon & Anheier, Reference Salamon and Anheier1998). Similarly, local businesses can help build connections between local communities and external parties (Ansari et al., Reference Ansari, Munir and Gregg2012). Finally, a high density of NPOs may result in higher specialization and increased inter-organizational collaboration (Baum & Oliver, Reference Baum and Oliver1996). We therefore hypothesize agglomeration effects between NPOs and other organizations for inter-organizational collaboration and thus systemic integration.

H1c

A high density of organizations has a positive effect on NPOs’ systemic integration.

Organizational Practices and their Effects on Social and Systemic Integration

The tendency of NPOs to apply business-like practices is well documented (Hersberger-Langloh et al., Reference Hersberger-Langloh, Stühlinger and von Schnurbein2021; Hwang & Powell, Reference Hwang and Powell2009). For instance, NPOs hire professionals and managers to meet institutional demands (Maier et al., Reference Maier, Meyer and Steinbereithner2016). NPOs become more business-like across several dimensions (e.g., structurally, rhetorically, in their goal formulation) to varying degrees. Some authors refer to this phenomenon as hybridity (see e.g., Brandsen et al., Reference Brandsen, van de Donk and Putters2005). We speak of configurations of organizational practices, considering the different instantiations of hybridity, some leaning more towards managerialism, some more towards organizational democracy.

Managerialism refers to mimicking the corporate model, i.e., adopting organizational forms, management knowledge, and practices (Alexander & Weiner, Reference Alexander and Weiner1998; Horwitz, Reference Horwitz1988; Hvenmark, Reference Hvenmark2013). Managerialism implies a shift towards market orientation, consumerism, and commodification (Maier et al., Reference Maier, Meyer and Steinbereithner2016). While consumerism reshapes the relation between NPOs and beneficiaries, funders and volunteers (Yngfalk & Yngfalk, Reference Yngfalk and Yngfalk2020: 344), commodification relates to the activities and outputs (e.g. Logan & Wekerle, Reference Logan and Wekerle2008) and echoes the Habermasian reification of social relations (Habermas, Reference Habermas1981: 267ff; Jütten, Reference Jütten2011). Additionally, we assume that organizations prefer interactions with similar organizations. Together with the reification of social relations due to managerialism, the theory of organizational homophily (Sapat et al., Reference Sapat, Esnard and Kolpakov2019; Spires, Reference Spires2011) leads to our H2a:

H2a

Managerialism has a positive effect on NPOs’ systemic integration

In contrast, practices of organizational democracy require a high level of participation of members, employees and volunteers. Such participatory routines, sometimes on a grassroot level (Enjolras, Reference Enjolras2009; LeRoux, Reference LeRoux2009), relate with more social integration of various individual actors. Typically, business-like forms of organizing leave little room for such democratic practices based on consensus-seeking and organizational openness (Eizenberg, Reference Eizenberg2012; Maier & Meyer, Reference Maier and Meyer2011), workplace participation and service quality (Baines et al., Reference Baines, Cunningham and Fraser2011; Keevers et al., Reference Keevers, Treleaven and Sykes2012). Due to these inherent characteristics of organizational democracy, we hypothesize:

H2b

Organizational democracy has a positive effect on NPOs’ social integration

Data Collection and Research Approach

Data and Research Setting

We use data from the Civic Life of Cities Lab,Footnote 1 an international research project investigating NPOs in urban regions across the globe. For this study, we draw on survey data from the metropolitan region of Vienna, Austria, which encompasses 2.6 million inhabitants. More than 20,000 NPOs operate in this area. In accordance with the guidelines by Salamon and Sokolowski (2016), we included self-governed private organizations with a limited profit-distribution requirement and non-compulsory participation in our sample, whereas purely grant-making foundations were excluded. Data was collected from Nov 2019 to Dec 2020.Footnote 2

We drew a random sample of 1,304 organizations from the Austrian Register of Associations, the Austrian Companies Register and a company database provided by the data provider Herolds. After removing inactive NPOs, a total of 1,117 executives of organizations (e.g. directors or presidents) were invited to participate in the survey. In total, 593 respondents completed the survey (53% response rate). Eighty percent of respondents completed the survey online, twenty percent requested a telephone or in-person interview. Respondents could choose between a German and an English questionnaire. For this study, we concentrated on the 459 NPOs located in the city of Vienna.

For neighborhood characteristics, we relied on administrative data at the level of the statistical grid unit, which was retrieved from the Austrian Central Statistics Office. The statistical grid separates the whole Austrian territory into standardized grid cells, each of which covers an area of 250 × 250 m. The city of Vienna is divided into 7,840 grid cells, which among other demographic data include per capita income, population count and the foreign population. These data were matched with information about the density of business activities, public organizationsFootnote 3 and NPOs.Footnote 4

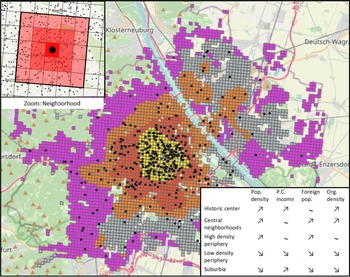

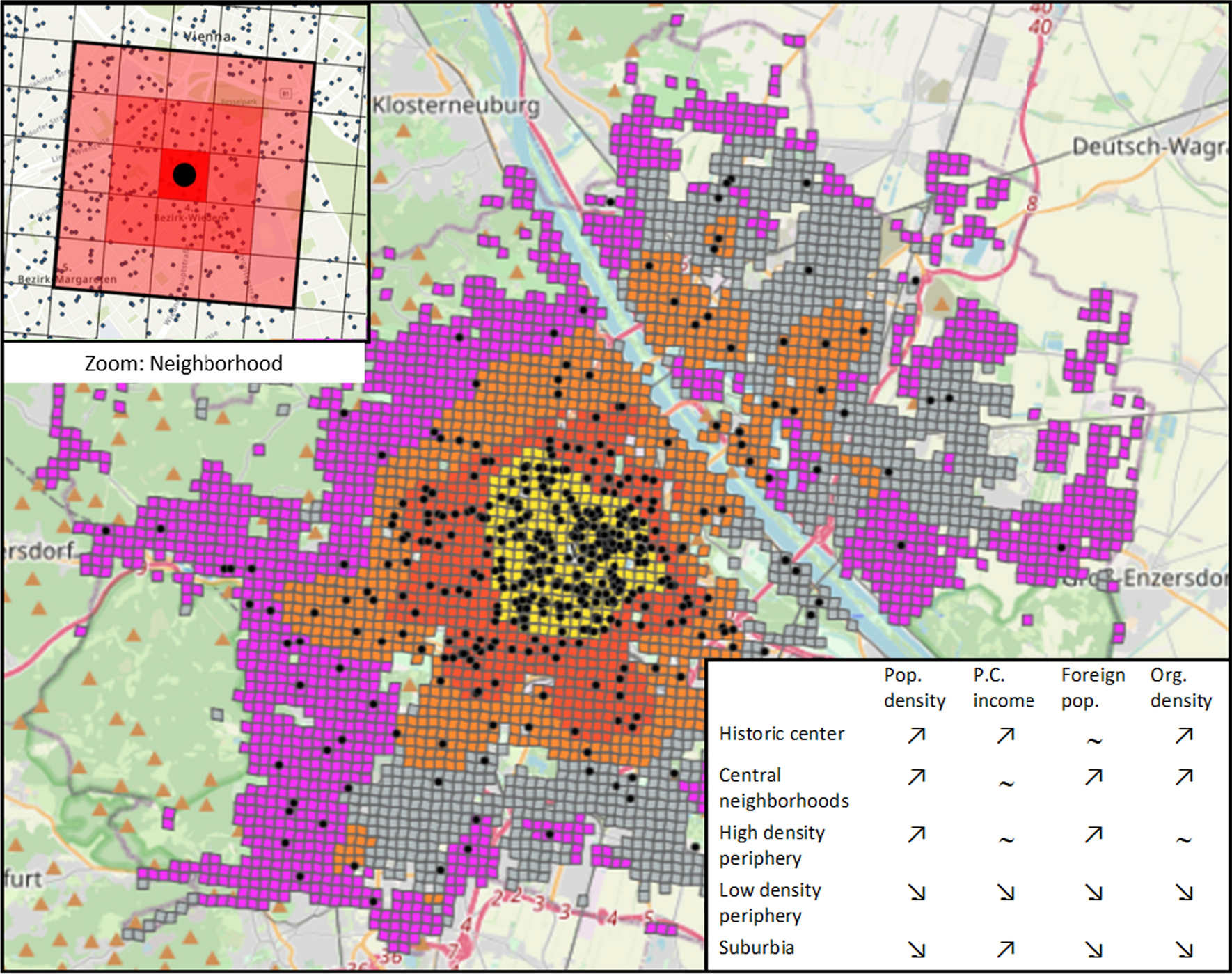

Figure 1 shows the city of Vienna covered by the statistical grid. Sample NPOs are indicated by black dots. The map illustrates different types of neighborhoods in Vienna in different colors, resulting from a K-means cluster analysis based on population density, per capita income, organization density, and share of immigrant population. Like many European capitals, Vienna’s neighborhood structure reveals a circular pattern: Central neighborhoods are characterized by a high population- and organization density. Income levels are highest in the historic center and the suburbs, while the share of immigrants is particularly high in the central neighborhoods around the historic core and in the densely populated peripheral areas, Vienna’s traditional working class districts. Almost half of the NPOs in our sample are located in the historic center (n = 204), twenty-five percent are located in the surrounding central neighborhoods (n = 112), and another quarter of NPOs are scattered across the three peripheral neighborhoods (high density periphery n = 68, low density periphery n = 24, and suburbia n = 36).

Fig. 1 Grid cells and neighborhood types in Vienna

Measures and Analysis

Local Neighborhood

As illustrated in the upper left corner of Fig. 1, we defined a neighborhood as the central grid cell of 250 × 250 m in which an NPO is located, plus its first order neighbors (i.e. the eight cells neighboring the NPO’s direct environment) and its second order neighbors (i.e. the 16 cells neighboring the first order neighbors). In sum, a neighborhood consists of 25 grid cells, which corresponds to a geographic area of about 1.56 km2.

This approach has three major advantages: First, each NPO is in the center of a relatively small neighborhood area, which is consistent with studies showing that many urban NPOs have a small radius of action (Pennerstorfer & Pennerstorfer, Reference Pennerstorfer and Pennerstorfer2019; Wolpert, Reference Wolpert1993). Second, the defined neighborhoods of all NPOs have exactly the same geographic size and are independent of political boundaries (e.g., districts). Third, the statistical grid units allow us to account for distance decay, which has been shown to be particularly relevant for NPOs (Bielefeld et al., Reference Bielefeld, Murdoch and Waddell1997; Peck, Reference Peck2007). We thus assume that neighborhood characteristics in the immediate vicinity of an NPO have a stronger influence on the organization than geographically more distant variables. Therefore, we discounted the first order neighbor variables by a factor of 0.33, and the second order neighbor variables by a factor of 0.66.

We included the following neighborhood-level variables: Population density is the total number of individuals living in a neighborhood (as control variable). Per capita income is measured by the average income of citizens in a neighborhood. Share of immigrant population is measured by the percentage of inhabitants who were not born in Austria or Germany.Footnote 5 We then included an index for organization density, which is the sum of standardized values of the number of NPOs, public organizations, and business units in a grid cell.

Organizational Practices

The two configurations of practices, managerialism and organizational democracy, have been extracted by a factor analysis of a multitude of variables measuring practices of organizing. Managerialism is measured by a composite of variables indicating whether or not an NPO is characterized by management positions, a mission statement, a budget plan, a strategic plan, is externally audited, performs quantitative performance evaluation, and has recently invested in management training.

To measure organizational democracy, we asked NPOs about participatory practices within the organization. The following variables built the organizational democracy factor: The involvement of volunteers and members in the development of services, the appointment of management positions, and the NPO’s online-appearance. Furthermore, we asked if the organization’s constituents have the possibility to participate in meetings, view meeting minutes, and become members of the organization.

Social and Systemic Integration

Our measures for social and systemic integration are inspired by Brandtner and Laryea (Reference Brandtner and Laryea2021:19–20). For social integration, we used items measuring the relevance of community building for the organization, namely building trust among citizens, promoting interaction among citizens, and creating a sense of belonging for their constituents. Respondents were asked how relevant they consider these activities for their organization: not relevant (value ‘0’), supporting tasks, side benefit (value ‘1’), and very relevant for organization (value ‘2’).

For systemic integration, respondents were asked about their organization’s collaboration with for-profit organizations, other NPOs, foundations, and governmental organizations. Furthermore, we included a sum index of eight items (values 0–8) measuring the involvement of NPO’s paid staff in strategic and operational decisions, a dummy variable for public events (e.g., conferences, rallies, charity events, public meetings) organized by the NPO, and a sum index (values 0–12) of four items (values 0–3) measuring the organization’s engagement in advocacy. Respondents were asked about the frequency of their organization’s involvement in policy processes. We constructed an index of social integration and one of systemic integration after performing an exploratory factor analysis.Footnote 6

Controls

First, we controlled for an NPO’s size by including annual budget and member size. Second, we controlled for NPO’s geographic outreach by differentiating between locations of their primary beneficiaries: Within the district (value ‘1’), the city of Vienna (value ‘2’), Austria (value ‘3’), and beyond (value ‘4’). Third, we controlled for NPO’s primary field of activity by including three dummy variables for recreational, representative and human service organizations. Based on ICNPO categorization scheme (Salamon & Anheier, Reference Salamon and Anheier1996: 7), we considered group 1 (culture and recreation) as recreational, groups 2, 3 and 4 (education and research, health, social services) as human services, and groups 5–12 (environment; development and housing; law, advocacy and politics; philanthropic intermediaries and voluntarism promotion; international; religion; business & professional associations, unions; not elsewhere classified) as representative. Finally, we controlled for population density of an NPO’s neighborhood. The characteristics of the independent and control variables are reported in the supplementary material. To test the effect of organizing practices and neighborhood characteristics on NPOs’ engagement in social and systemic integration, we conducted multiple linear regression analyses.

Results

Descriptives

Tables 2–4 in the supplementary material show descriptives, plus a few remarkable findings. With regard to systemic integration, the descriptives indicate high levels of engagement in various forms of collaboration: More than 77% of NPOs collaborate with other NPOs, 56% with public organizations, 50% with for-profit organizations, 16% with foundations, and about 43% of NPOs organize public events. Descriptives of social integration show that activities such as trust-building among people and promoting interaction amongst them are prevalent.

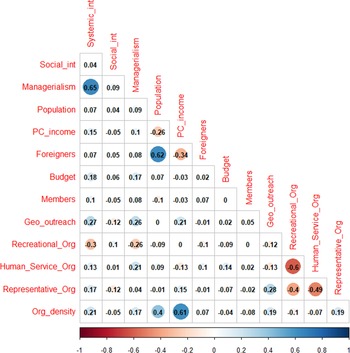

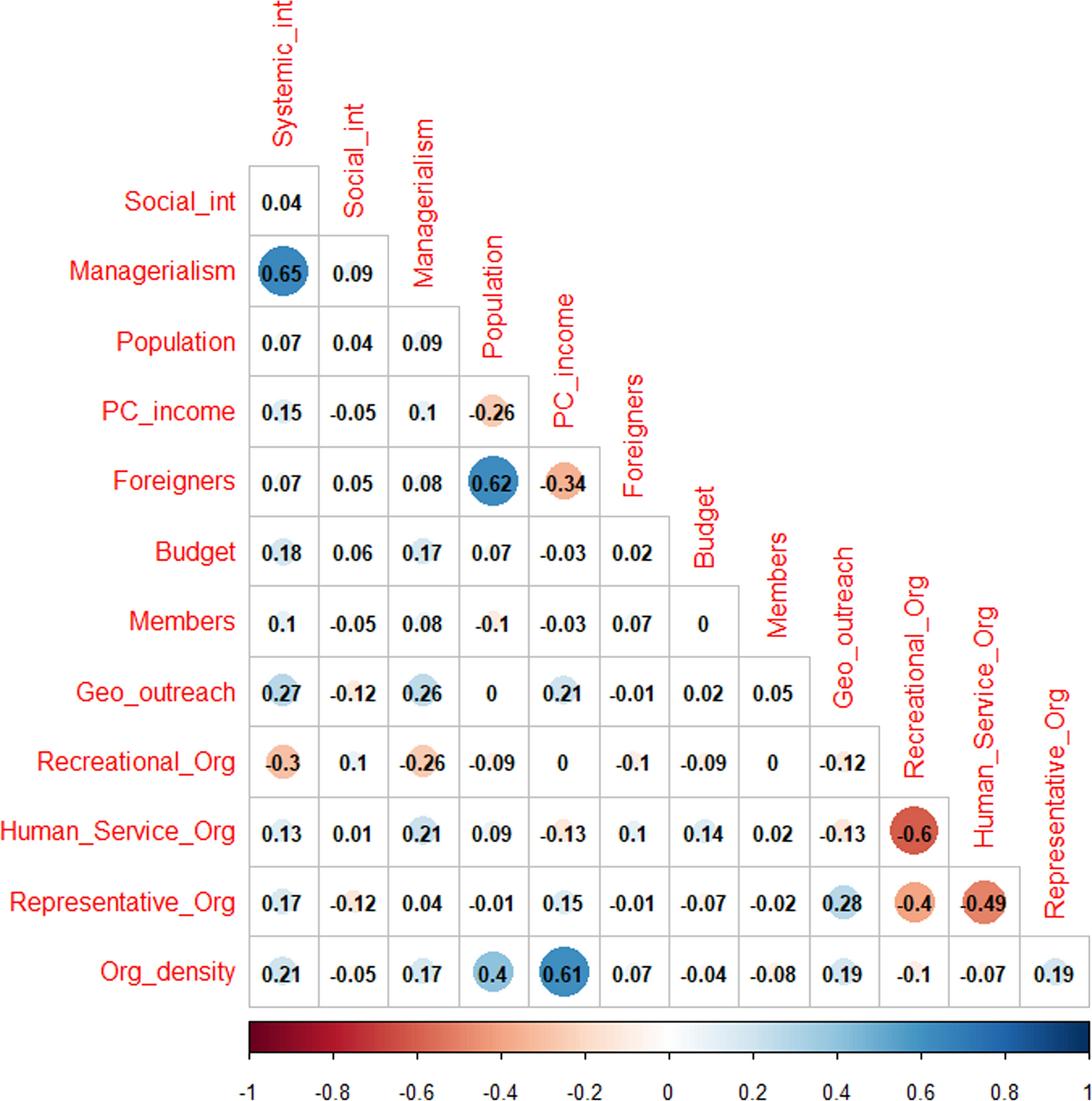

Correlations are consistent with the theoretical expectations (see Fig. 2). Within correlations, we see no support for colonialization respectively crowding out of social by systemic integration. Systemic integration strongly correlaties with managerialism (r = 0.65). Within neighborhood variables, organization density and per capita income (r = 0.61) show a high correlation. Likewise, the share of foreigners correlates with population density (r = 0.62). To check for multicollinearity, variance inflation factor (VIF) tests were performed. The mean VIF of both models is below 1.9, the maximum VIF is 3.6, thus not indicating multicollinearity.

Fig. 2 Correlation matrix

Regression Models

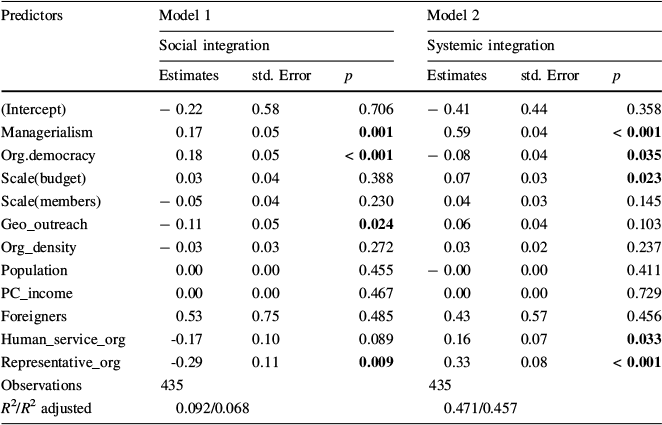

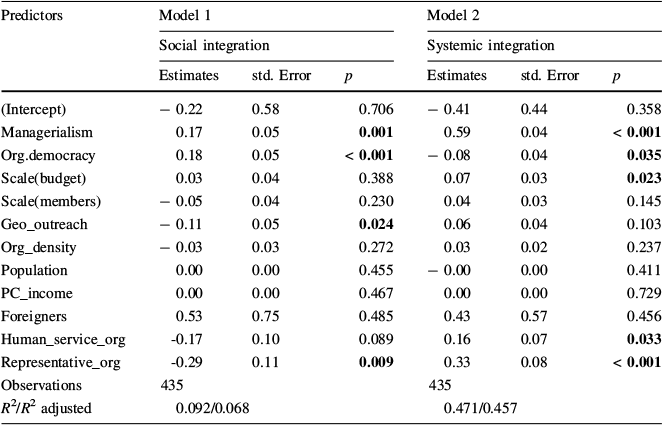

We conducted two regression analyses (model 1 and model 2) to test H1a-H1c and H2a-2b (Table 1). Whereas the adjusted R 2 for social integration is only 0.068 (model 1), it is 0.457 for systemic integration (model 2). First, we tested whether neighborhood characteristics explain variation in social and systemic integration. H1a assumes a positive effect of low per capita income on social integration. The results, however, indicate no significant relationship, thus not confirming H1a. Similarly, neither H1b (immigrant population) and H1c (organization density) are supported by the results. Thus, all three hypotheses about the effects of neighborhood characteristics on social and systemic integration are not supported by our results.

Table 1 Regression results

Predictors |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Social integration |

Systemic integration |

|||||

Estimates |

std. Error |

p |

Estimates |

std. Error |

p |

|

(Intercept) |

− 0.22 |

0.58 |

0.706 |

− 0.41 |

0.44 |

0.358 |

Managerialism |

0.17 |

0.05 |

0.001 |

0.59 |

0.04 |

< 0.001 |

Org.democracy |

0.18 |

0.05 |

< 0.001 |

− 0.08 |

0.04 |

0.035 |

Scale(budget) |

0.03 |

0.04 |

0.388 |

0.07 |

0.03 |

0.023 |

Scale(members) |

− 0.05 |

0.04 |

0.230 |

0.04 |

0.03 |

0.145 |

Geo_outreach |

− 0.11 |

0.05 |

0.024 |

0.06 |

0.04 |

0.103 |

Org_density |

− 0.03 |

0.03 |

0.272 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.237 |

Population |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.455 |

− 0.00 |

0.00 |

0.411 |

PC_income |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.467 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.729 |

Foreigners |

0.53 |

0.75 |

0.485 |

0.43 |

0.57 |

0.456 |

Human_service_org |

-0.17 |

0.10 |

0.089 |

0.16 |

0.07 |

0.033 |

Representative_org |

-0.29 |

0.11 |

0.009 |

0.33 |

0.08 |

< 0.001 |

Observations |

435 |

435 |

||||

R 2/R 2 adjusted |

0.092/0.068 |

0.471/0.457 |

||||

*p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001

Second, we tested for effects of organizational practices on social and systemic integration. H2a predicts a positive relationship between managerialism and NPOs’ engagement in systemic integration (model 2). H2b assumes a positive relationship between organizational democracy and the NPOs’ engagement in social integration (model 1). The results of both models show positive and significant effects, thus supporting H2a and H2b.

Regarding the control variables, the results indicate that geographic outreach has a significant negative effect on social integration. Organizational size in terms of budget has a modest significant positive effect on systemic integration, while the member base has no effect in neither of the models. Finally, the results confirm our assumptions about the effects of NPOs’ primary field of activity: Compared to recreational NPOs (the reference category), NPOs operating in human services and representative organizations exhibit significantly higher levels of systemic integration. For the representative category, the results are even highly significant.

Discussion

We analyzed the influence of neighborhood characteristics and organizational practices on NPOs’ engagement in social and systemic integration in the context of the city of Vienna. By considering how NPOs engage in both forms of integration, we advance scholarship on how NPOs create social cohesion and neighborhood vitality (e.g., Hwang & Young, Reference Hwang and Young2022; Lichterman & Eliasoph, Reference Lichterman and Eliasoph2014; Marwell & Gullickson, Reference Marwell and Gullickson2013). We thereby add to scholarship on social capital by highlighting the organizational perspective of NPOs in enhancing urban cohesion. Particularly, we extend the understanding of the systemic aspect of urban cohesion. Our study thus provides a nuanced picture and shows that NPOs mostly engage in both forms of integration.

Concerning neighborhood effects, our findings suggest that NPOs’ engagement in social and systemic integration does not depend on neighborhood characteristics. However, at the city level, social and systemic integration vary as NPOs concentrate in central, affluent neighborhoods. As the overall density of organizations is highly correlated with the per capita income (0.61), we see an uneven distribution of overall NPOs’ integrative activities across neighborhoods. These results are consistent with previous research suggesting agglomeration effects (e.g., Bielefeld and Murdoch, 2004; Katz, Reference Katz2014).

Concerning the effects of organizational practices on the different forms of integration, our study shows a positive effect of organizational democracy on social integration and a positive effect of managerialism on systemic integration. The model for social integration is weak but shows a significant influence of organizational practices; but neither neighborhood characteristics, fields of activity, nor organizational size explain how much NPOs engage in social integration. This is surprising and calls for further research.

In line with the theory of organizational homophily (Sapat et al., Reference Sapat, Esnard and Kolpakov2019; Spires, Reference Spires2011), we find that managerialist organizations interact more with other organizations, independent of whether it concerns NPOs, businesses, and public organizations. Further, organizational size positively relates to systemic integration. Hence, NPOs concentrating on inter-organizational collaboration are characterized by managerial practices and larger budgets and tend to be located in central and more affluent neighborhoods.

Warnings of the collateral damage of managerialism in NPOs (Baines et al., Reference Baines, Cunningham and Fraser2011; Keevers et al., Reference Keevers, Treleaven and Sykes2012; Maier et al., Reference Maier, Meyer and Steinbereithner2016) are not justified when it comes to social integration: our study shows that the managerial practices do not harm NPOs’ engagement in integration. Even organizational size has no negative influence on social integration. We thus suppose that managerial practices have pervaded NPOs, but obviously their adjustment to managerialism has mitigated colonization effects, e.g. the crowding out of social by systemic integration.

In a nutshell, our findings deliver a nuanced picture of NPOs’ engagement in integration, challenging the one-sided impression coined by prior qualitative research. There are indeed single NPOs that work in disadvantaged neighborhoods, providing neighborhood communities with networks, resources, and social capital. Yet, our study shows a lower density of NPOs in poor neighborhoods. Thus, the NPOs’ location decisions do not necessarily follow citizens’ needs. Instead, NPOs tend to concentrate in neighborhoods that are already endowed with a lively and strong organizational infrastructure.

Our study has several limitations. First, our findings are context specific. Our conclusions are bound to the particularities of a specific type of European city. Hence, studies should replicate the research design in other urban contexts to scrutinize the local embeddedness of NPOs and the differences in their engagement in social and systemic integration.

Second, due to the cross-sectional character of our data, we can show relations between organizational practices and forms of integration but no causality in a strict sense. Managerialism forwards social and systemic integration, and organizational democracy forwards social integration, yet the reverse causality is plausible too. Furthermore, our low R 2 for the social integration model demands caution, whereas the results for systemic integration allow us to paint a much sharper picture.

Third, our measures of social integration aim at NPOs’ goals, whereas our measures of systemic integration aim at NPOs’ actual activities, providing a further argument why our results for systemic integration are stronger. Fourth, our location data only covers NPOs’ headquarters. For larger NPOs with many branches, this might still yield a bias towards inner-city locations. It is remarkable that smaller grassroot-NPOs located in the outskirts and poorer neighborhoods do not compensate for this bias. However, as social integration negatively relates with geographical outreach, there is no direct evidence that branches and subsidiaries of inner-city NPOs compensate for this structural deficit.

Finally, there are implications for urban planning and policymaking. Our results suggest strong agglomeration effects that aggravate differences in service provision and infrastructure even in an affluent city like Vienna with low social segregation (Kohlbacher & Reeger, Reference Kohlbacher and Reeger2020; Ranci & Sabatinelli, Reference Ranci and Sabatinelli2020). Assuming that NPOs deliver relevant contributions to urban cohesion, urban planning should consider the impact of placing public organizations like schools, hospitals, and kindergartens. The same applies for the public support of local business activities. Similarly, the location of NPOs matters. Offering affordable office space for NPOs in public premises or subsidizing rents for NPOs in vulnerable urban neighborhoods could contribute to a more effective spatial outreach of civil society and thus foster urban cohesion.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Vienna University of Economics and Business (WU).

Declarations

Ethical Approval

The material is the authors’ own original work, which has not been previously published elsewhere. The study is based on statistical- and survey data. All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with national and institutional ethical standards. We have not received any third-party funding and have no actual or potential conflicts of interest to disclose.