Introduction

Malaria and its impact

Malaria was likely the most deadly human disease throughout premodern periods, and its impact on the course of human events has drawn increasing attention from historians in recent research. The disease is astonishingly complex, and its protean nature presents much opportunity for varying clinical manifestations, coinfection and misdiagnosis (Faure, Reference Faure2014).

Malaria is caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium introduced to the host during blood meals by the vector, female Anopheles mosquitoes. The inoculated sporozoites make their way to the liver where asexual reproduction develops hepatic schizonts, which rupture to release merozoites into the bloodstream where they invade red blood cells. Cyclic release of reproduced merozoites from lysed erythrocytes produced the periodic fevers characteristic of the disease. Three species of malaria infected humans of the Mediterranean world in antiquity: Plasmodium malariae, P. vivax and P. falciparum. The asymptomatic hepatic phase varies between them from 5.5 days for P. falciparum, to 8 days for P. vivax, and 15 for P. malariae; with corresponding incubation periods of about 12, 15 and 28 days. With P. vivax, some of the hepatic phase parasites become sleeping hypnozoites and remain inert in the liver, where they can awaken and cause relapses weeks or months later. Distinct periodic fever patterns were recognized and named by ancient physicians accordingly. Thus, P. malariae produced quartan fever (paroxysm on the fourth day), P. vivax and P. falciparum rendered tertian fever (paroxysm on the third day), with the latter often never completely waning and thus called semitertian. Fevers synchronized to a daily spike were deemed quotidian. These identifying periodicities are often not observable early in infections, become irregular or continuous due to multiple inoculations or coinfection, and are rarely observed today (Sinden and Gilles, Reference Sinden, Gilles, Warrell and Gilles2002; Cunha and Cunha, Reference Cunha and Cunha2008; White, Reference Farrar, Hotez, Junghanss, Kang, Lalloo, White and Garcia2024).

Because of its perceived ‘perniciousness,’ Falciparum malaria has received the lion’s share of attention in modern discussion of malarial danger to life. Its recurrent fever was branded ‘malignant tertian’, while that of P. vivax received the label ‘benign tertian’. Recent studies, however, have recognized and highlighted P. vivax’s potential for severe disease and fatal outcomes (Baird, Reference Baird2013). Dormant hypnozoites of P. vivax are effectively activated by other febrile infections, including malaria itself, causing relapse and inevitable coinfection, thus extending and heightening morbidity and mortality (Shanks and White, Reference Shanks and White2013; White NJ, Reference Farrar, Hotez, Junghanss, Kang, Lalloo, White and Garcia2024).

A form of immunity to malaria, preventing harm but not infection itself, is gained in stages through survival of multiple inoculations. This ‘premunition’ is species and strain specific and is easily lost with time; lack of inoculation/reinfection can leave an individual again fully susceptible. A mobile person with gained immunity for strains within a locality is still vulnerable to strains in other regions. This feature of malaria is a critical issue for highway travellers. They are particularly at risk without immunity for new regions they enter; and if infected elsewhere, they can introduce strains for which locals have no immunity (Sallares, Reference Sallares2002; Carter and Mendis, Reference Carter and Mendis2002b; White NJ, Reference Farrar, Hotez, Junghanss, Kang, Lalloo, White and Garcia2024). Travellers thus both are at greater risk and represent risks themselves.

Malaria in Anatolia

It remains unclear as to when malaria species affecting humans arrived in Anatolia (Map 1). Emerging paleogenetic evidence suggests that P. falciparum is no less than 100 000 years old, and the species underwent a major expansion around 10 000 years ago, concurrent with the expansion of human populations in the Neolithic period (Sallares et al., Reference Sallares, Bouwman and Anderung2004). At Neolithic Çatalhöyük, in central Anatolia, a high prevalence of porotic hyperostosis in skeletons provides evidence of persistent anaemia, a possible sign of endemic malaria, though this not the sole explanation for this phenomenon (Angel, Reference Angel1966, Reference Angel1978; Ledger et al., Reference Ledger, Anastasiou, Shillio, Mackay, Bull, Haddow, Knüsel and Mitchell2019).

Map 1. Anatolia/Asia Minor, with elevation, provincial names and roads.

Recent aDNA data confirm that P. vivax was present in Europe from at least the Bronze Age, long before the earliest textual references. Genetic detection of P. falciparum compliments the first descriptions of its symptomology in classical Greek sources (Michel et al., Reference Michel, Skourtanioti, Pierini, Guevara, Mötsch, Kocher, Barquera, Bianco, Carlhoff, Coppola Bove, Freilich, Giffin, Hermes, Hiß, Knolle, Nelson, Neumann, Papac, Penske, Rohrlach, Salem, Semerau, Villalba-Mouco, Abadie, Aldenderfer, Beckett, Brown, Campus, Chenghwa, Cruz Berrocal, Damašek, Duffett Carlson, Durand, Ernée, Fântăneanu, Frenzel, García Atiénzar, Guillén, Hsieh, Karwowski, Kelvin, Kelvin, Khokhlov, Kinaston, Korolev, Krettek, Küßner, Lai, Look, Majander, Mandl, Mazzarello, McCormick, de Miguel Ibáñez P, Murphy, Németh, Nordqvist, Novotny, Obenaus, Olmo-Enciso, Onkamo, Orschiedt, Patrushev, Peltola, Romero, Rubino, Sajantila, Salazar-García, Serrano, Shaydullaev, Sias, Šlaus, Stančo, Swanston, Teschler-Nicola, Valentin, Van de Vijver, Varney, Vigil-Escalera Guirado, Waters, Weiss-Krejci, Winter, Lamnidis, Prüfer, Nägele, Spyrou, Schiffels, Stockhammer, Haak, Posth, Warinner, Bos, Herbig and Krause2024, 126; Sikora et al., Reference Sikora, Canteri, Fernandez-Guerra, Oskolkov, Ågren, Hansson, Irving-Pease, Mühlemann, Holtsmark Nielsen, Scorrano, Allentoft, Valeur Seersholm, Schroeder, Gaunitz, Stenderup, Vinner, Jones, Nystedt, Sjögren, Parkhill, Fugger, Racimo, Kristiansen, Iversen and Willerslev2025, 1015). Despite the present dearth of conclusive physical evidence for malaria in early Anatolia, it seems highly likely that some form of Plasmodium was present there from the Neolithic period onward, with confidence for P. vivax and P. falciparum rising to near certainty by the Bronze Age and classical periods, respectively.

Recent translation of an iron age Hieroglyphic-Luwian inscription (c. 800 BCE) discovered at the village Çineköy (Figure 1) apparently references a local king draining marshes known for their unhealthiness (Oreshko, Reference Oreshko2019). This is especially noteworthy, as Çineköy is located south of Adana in the region of Cilicia Pedias (southeastern Anatolia, modern Türkiye), which became the most consistently malarial area of Anatolia/Asia Minor and thus the focus of this study.

Figure 1. Statue from Çineköy of the Luwian weather god Tarhunza on a cart-like base with an inscription apparently celebrating the draining of unhealthy swampland.

The evidentiary picture develops significantly from the classical period onward. The medical writings of Hippocrates of Cos (4th century BCE) and Celsus (1st century CE), both well acquainted with Anatolia, show a keen awareness of a typology of intermittent fevers (quartan, tertian, semitertian), reflecting different malaria species, as well as recognizing that swampy environments and the heat of late summer/autumn create greater risk of infection (Sallares, Reference Sallares2002; Nicovich, Reference Nicovich2025). Dioscorides, a 1st-century medical writer and native of Tarsus, also in Cilicia, included numerous herbal remedies specifically aimed at alleviating intermittent fevers in his De Materia Medica (Pedanius Dioscorides, 2005).

Cilicia Pedias and Malaria

Cilicia Pedias, or ‘flat Cilicia’ – as distinct from Cilicia Trachea, or ‘rough Cilicia’ to the west – was formed by the silting action of several watersheds emanating out of the Taurus mountains. The resulting river systems and their alluvial floodplains, the Cydnus (modern Berdan), Sarus (Seyhan) and Pyramus (Ceyhan), give the region its name. Loamy soils characterize the geology of the plain, creating an ideal setting for large-scale agriculture and human settlement. This agricultural potential and attendant urbanism made Cilicia an important region in its own right, but the same geology also allowed for substantial water infiltration, the development of large wetlands and the propagation of disease-bearing mosquito species. As for the latter, at least 2 able and adaptable malaria vectors, Anopheles superpictus and An. sacharovi, were and remain native to the region (Sinka et al., Reference Sinka, Bangs, Manguin, Coetzee, Mbogo, Hemingway, Patil, Temperley, Gething, Kabaria, Okara, Van Boeckel, Godfray, Harbach and Hay2010; Browning, Reference Browning2021). Thus, Cilicia Pedias became a Plasmodium hotspot, quite like the better-documented malarial landscapes of the Roman Campagna and Pontine Marshes of Italy (Sallares, Reference Sallares2002; Reilly, Reference Reilly2022; Browning, Reference Browning2023).

References to seasonal fevers in Cilicia appear in the Roman period. Tiro, Cicero’s famous slave-secretary, fell behind his master when returning from Cicero’s governorship of Cilicia in November 50 BCE due to fever, a reflection of the lagging morbidity common to autumnal malaria infections. Tyro’s illness resulted in several panicked letters from Cicero regarding his condition (Cicero, Letters to Friends 121–127).

Early Christian hagiography also reflects the insalubrious nature of the Cilician landscape. A corpus of saints’ lives details several 4th century ‘unmercenary’ (or ‘silverless’, i.e., unpaid) Christian physicians, including Zenaida and Philonilla, Sozon of Cilicia, Thallaleus of Aigai (Aegeae) and the sibling healers Zenobius and Zenobia of the same city (Sozon of Cilicia, 1868; Zenaida and Philonilla, Reference Zenaida and Philonilla1868; Zenobius and Zenobia, Reference Zenobius and Zenobia1888; Thallalaios of Aigai, Reference Delehaye1902). By far the most famous cult was that of Ss. Cosmas and Damian, also associated with Aegeae, traditionally presented as twin brothers who became physicians and eventually martyrs during Diocletian’s reign (c. 300 CE). As with the other ‘unmercenary’ saints, the brothers healed a wide variety of ailments, specifically including semitertian fevers indicative of P. faliciparum, and their relics became known for curing the whole host of intermittent fevers (Cosmas and Damian, Reference Cosmas and Damian1867). Miraculous healing is a common trope across Christian hagiography, but the confluence of tales regarding physician-saints in late-Roman Cilicia exposes the severity of the regional disease landscape.

By the medieval period, transhumance in the region had adapted to the malaria season, with both rural shepherds and urban populations removing themselves to the Taurus Mountains during the summer months to avoid infection. The 13th-century Old French Continuation of William of Tyre describes the seasonal movement:

For the Cilician plain is hot and disease-ridden in summer, while the mountains are fresh and healthy. Accordingly, the inhabitants of the land have their dwellings in the mountains, and because of the heat they live there from the beginning of June until the middle of September; then they come down to the plain because the land is cooler and less unhealthy. (Continuation of William of Tyre, 97)

This strategy continued in Cilicia Pedias until the modern period (Barker, Reference Barker1853; Gratien, Reference Gratien2017; Gratien, Reference Gratien2022) and reflects similar patterns of transhumance in malarial landscapes elsewhere in the Mediterranean (Sallares, Reference Sallares2002).

As in the classical period, intermittent fevers remained so prevalent in Cilician Armenia that the 12th-century physician Mkhitar Heratsi produced a work specifically devoted to them, On the Relief of Fevers (Hacikyan, Reference Hacikyan2000).

Early modern travellers consistently remarked on the pestilential nature of the Cilician landscape. C. R. Cockerell visited the area in June 1817, before sailing for Malta. Intermittent fevers set in thereafter, plaguing him for several weeks after his arrival in Valletta (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell and Cockerell1903, 200-202). William Burckhardt Barker, an early English explorer of Cilicia, regarded the area around Tarsus as especially dangerous due the extensive local marshes and ‘putrid and intermittent fevers’ that raged in July and August, clear recognition of the spatio-temporal character of malaria risk (Barker, Reference Barker1853, 114). Barker further noted the ‘innumerable mosquitoes’ encountered in the region, though he makes no connection between the insect and the disease (Barker, Reference Barker1853, 277). At the turn of the 20th century, not long after scholars like Charles Laveran and Ronald Ross had made the critical connection between the mosquito vector and the plasmodial parasite they carried, biblical scholar W. M. Ramsay declared that Tarsus and its hinterlands were a ‘useless marsh … breeding fever and insect pests’ (Ramsey, Reference Ramsey1903, 365).

The arrival of diagnostic tools in the early 20th century allowed for epidemic malaria to be actively quantified for the first time, as reflected in records from the First World War. German troops crossing the Cilician Gates in 1916 found themselves exposed to P. falciparum for the first time, with different units reporting anywhere from 25% to 83% infection rates (Engels, Reference Engels1978). The French-led Armenian Medical Mission in Cilicia recorded more than 3000 malaria cases among refugees in July and August 1919, 35% of all patients treated in that period, far more than any other illness (Gratien, Reference Gratien2016). High levels of endemic malaria remained problematic in Republican Turkey following the First World War, with considerable spikes throughout the country during the Second World War, a consequence of extensive migrant activity during the period. Indeed, despite the widespread use of antimalarial prophylaxis and DDT, epidemics recurred through the 1990s in certain regions, including Çukurova province, which includes Cilicia (World Health Organization, 2013).

The foregoing examples show the consistently endemic malarial nature of Cilicia Pedias and the heightened threat it posed in the late summer and autumn. Numerous additional anecdotes from the classical and medieval periods suggest the presence of malaria on the Cilician plains. The vast majority of such references, with varying spatial specificity, involve travel through the region and are treated under the ‘Discussion’ section.

The peril on roads through Cilicia Pedias

Cilicia Pedias sat astride a nexus of routes connecting the civilizational centres of the Near East. The central Anatolian plateau lay just beyond the Taurus range to the north, while east sat the headwaters of the Euphrates and the Tigris, tying Cilicia into the larger Mesopotamian world. Across the Amanus range to the southeast, the Levantine coastline stretched towards Egypt. Cilicia’s ports, like Aegeae (Ayas), connected the region into the main trade lanes extending to the wider Mediterranean world.

Cilicia thus hosted itinerant merchants, pilgrims and military forces passing through the region, many of whom were immune-naïve to the species or strains of malaria endemic to the area. Consequently, locally endemic malaria could easily escalate to epidemic levels within groups of new arrivals and higher disease incidence for travellers exposed during their passage.

To cite 1 illustrative example of the latter, in the summer of 333 BCE Alexander the Great’s army marched through the Cilician gates and encamped at Tarsus, on the way to encounter Darius III at Issus later that fall. Alexander bathed in the famously cold, snowmelt waters of the Cydnus, and swiftly took ill with oscillating fevers and chills, delaying his march against Darius by some weeks (Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander 2.3.7-10; Plutarch, Alexander 19; Quintus Curtius, 3.5). Indeed, Engels (Reference Engels1978) argues that Alexander’s eventual death at Babylon in 323 may have resulted from a recrudescence of malaria from this previous exposure in Cilicia.

Goals and objectives

This study correlated historical accounts of apparent malarial infection in travellers through Cilicia Pedias with a quantitative measure of malaria risk, and the goal of providing a tool for assessing the impact of malaria on major events. These events often involved large scale military incursions, mass-population movement, or transit to intended activities elsewhere, for which malarial morbidity or mortality influenced outcomes with repercussions for the region and beyond.

Materials and methods

Correlation of a quantitative measure of malaria risk with historical accounts of malaria infection requires 2 data-preparation efforts:: (1) creation of a malaria risk model for the premodern world, and (2) identification and evaluation of sources describing likely malarial infections or outbreaks with sufficient spatial certainty for application of the model. All geoprocessing, including that described for previous efforts, was conducted using ArcGIS Pro 3.5.

Malaria risk model

Assessing malaria risk for antiquity

Malaria risk modelling is an important and ongoing task in the contemporary world, as the disease remains a significant health burden in many areas. Typical models utilize geographic information system (GIS) software in a multi-criteria evaluation design (Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Mappin, Dalrymple, Bhatt, Cameron, Hay and Gething2015) with many variables, as necessitated by the complexities of malarial epidemiology and ecology. Often, they incorporate near real-time remote sensing components as predictors of pending risk for the sake of needed prevention efforts. Validation of such models remains problematic and usually involves comparing predicted results with observed outcomes (MacLeod et al., Reference MacLeod, Jones, Di Giuseppe, Caminade and Morse2015). A malaria risk model for the premodern world must be somewhat simpler, since anthropogenic risk factors like land use cannot be known with spatial certainty and remote sensing data is not possible for antiquity. Even for a simpler model, validation remains the major difficulty.

To meet these challenges, Browning (Reference Browning2021, Reference Browning2023) developed a GIS-based malaria risk model for the Mediterranean in antiquity, using a pre-eradication era map of malaria endemicity in Italy for calibration and validation. The map, Carta della Malaria dell’Italia (Torelli, Reference Torelli1882), represents the best possible combination of modern cartography and a record of malaria endemicity just prior to identification of the vector cause of the disease. An original paper publication of this map (hereafter ‘Torelli Map’) showing 4 discrete levels of endemicity was scanned, georeferenced and converted to a GIS layer of its malarial zones as a baseline for creation of the risk model (Browning, Reference Browning2023).

Model development identified geographic risk layers that can be reasonably known for antiquity. Each potential layer was rescaled from its native data range to a continuous 0–3 range to find the closest correlation to the discrete 0–3 scale of the Torelli Map. Calibration employed an iterative process for ranges of rescaling variables and comparison of the results against the endemicity zones in a ‘selected’ portion of the Torelli Map. The calibrated layers were then combined in varying percentages using a nested iterative process within the same ‘selected’ area to calculate malaria risk on the continuous 0–3 scale. Each combination was compared to the Torelli Map risk zones for verification. The best performing combinations were then repeated with the same nested iterative process for validation against a ‘withheld’ area of the map. Refinements to the original model resulted in the most recently published version, with 4 risk layers at the following values: elevation 62.1%, precipitation 29.4%, temperature 7.1% and topical wetness index 1.4% (Browning, Reference Browning2023, 6–9, with online supplemental material). With this GIS-based model, historical sources with spatial certainty and evidence for malarial infection can be analysed against calculated risk in that location or locations.

Support for model validation comes from excavated skeletal DNA confirmation of P. falciparum malaria at 3 Italian sites from the Roman (1st–2nd centuries CE) and late antique (mid-5th century CE) periods, in or quite near to the ‘withheld’ area of Italy. Additional support for validity derives from copious anecdotal evidence from textual sources that extend confidence in the model to other periods (Browning, Reference Browning2023, 9–11). The model performs well in application to other regions of the Mediterranean, as shown by Nicovich (Reference Nicovich2025), in part for the region of focus here. Thus, Browning’s malaria risk model for the Mediterranean in antiquity served as the basis for quantitative assessment.

Modelling risk on roads

The goal of providing a tool for assessing the impact of malaria on ‘major events’ in Cilicia Pedias creates the need for modelling risk specifically on roads, as the vast majority of such events involve travellers, invaders, or armies enroute to campaigns. It is also the case that road building itself often contributes to malaria risk by blocking drainage so as to increase the vector capacity immediately adjacent to the road (Sallares, Reference Sallares2002, 181; Marciniak et al., Reference Marciniak, Herring, Sperduti, Poinar and Prowse2018, 220).

Currently available datasets of Roman/medieval roads for GIS use are derived from the last great print atlas of classical antiquity, the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World (Talbert, Reference Talbert2000). Unfortunately, digitization of features from its excellent maps transferred weaknesses of the print form into electronic datasets.

Evidence for the actual path of known routes varies from the certainty of archaeological remains to mere speculation where physical evidence is completely absent. Often, text sources reveal that a road connected certain cities or other points, but no trace of an ancient path is extant. A theoretical line indicating a road between those known points is sufficient for the purposes of small-scale maps such as those found in print atlases. But, digitization of them causes disconnects and spatial inaccuracies that hinder large-scale GIS application and compromise results. While not as severe in Britain and Italy, the datasets for areas like Asia Minor are especially unsuitable. This situation dictated the creation of a new road dataset for Cilicia Pedias and, indeed, a new methodology for doing so.

Details of a methodology for establishing a more accurate ancient road dataset are tangential to this study. Therefore, full documentation is under preparation by Browning for publication elsewhere, and a brief summary provided here. The following general steps were followed in creation of a road dataset for Cilicia Pedias:

1) Attested road points were identified from textual sources and accurate GIS-level locations established for them. These include named cities, road stations and major obstacles like mountain passes.

2) Archaeological remains that mark known path points, such as extant stretches of ancient road, bridges, territorial arches and in situ milestones, were identified and accurately geolocated.

3) Gaps between the above attested and known points were filled in by an iterative process using the GIS ‘least cost path’ (LCP) technique with multiple variables. Ranges of LCP results were carefully evaluated against other potential road evidence such as long-serving historic roads visible on older satellite imagery that likely overlay the ancient path, distance data from surviving milestones and details of now-lost roads commented on by early modern travellers.

4) The resulting GIS-capable polyline dataset of major roads is divided into segments by major stopping points; each with attributes identifying source, accuracy and correlation with previous scholarly works.

During the review process for this study, a new and much-improved dataset of ancient roads for the entire Roman world was published and became available for GIS use: Itiner-e (de Soto et al., Reference de Soto, Pažout, Brughmans, Vahlstrup, Á, Bongers, Christoffersen, Crépy, Johansen, Lewis, Manière, Massa, Møller, Redon, Renda, Şahin, Sobotková, Spatzek, Verhagen and Weissova2025). The process briefly outlined above is quite similar to that used to construct the Itiner-e dataset (de Soto et al., Reference de Soto, Pažout, Brughmans, Vahlstrup, Á, Bongers, Christoffersen, Crépy, Johansen, Lewis, Manière, Massa, Møller, Redon, Renda, Şahin, Sobotková, Spatzek, Verhagen and Weissova2025, 2-6), with the extra elements of LCP analysis and more attributes defining source and accuracy for road segments.

In order to assign malaria risk to travel on specific roads, the created road layer must be combined with risks calculated by the model. This was achieved with the following sequence of geoprocessing using ArcGIS Pro 3 tools. The one-dimensional polyline road layer was first converted to a two-dimensional layer using the Buffer tool. A buffer distance of 542 m was chosen; the average flight range for genus Anopheles mosquitos (Verdonschot and Besse-Lototskaya, Reference Verdonschot and Besse-Lototskaya2014, 72). Flight ranges certainly vary between species and local terrain; and much greater distances have been measured with wind assistance (Le Prince and Griffitts, Reference Le Prince and Griffitts1917). Nevertheless, this figure represents a reasonable one that provides a local average exposure, avoids potential overreach and somewhat mitigates remaining uncertainty about precise road location (Browning, Reference Browning2021, 81). The resulting polygon layer, representing a 1084 m wide road path, was overlaid with the malaria risk model layer. The Zonal Statistics tool calculated risk statistics for each buffered road segment, with mean risk as the primary assessment metric.

Historical sources

Identification of malaria in historical sources

Retrospective diagnosis of premodern disease is fraught with difficulty as the ancient sources, when they speak of disease at all, are ignorant of germ theory, lack modern diagnostic tools and possess only a limited lexicon of symptomology with which to describe an illness. This leads some scholars to regard diagnoses utilizing modern scientific definitions as pointless, as all we can recover from a text is a social understanding of the disease, not the disease itself (Arrizabalaga, Reference Arrizabalaga2002; Cunningham, Reference Cunningham2002; Phillips, Reference Phillips2017). This ‘social diagnosis’ approach, however, unduly dismisses the testimony of our contemporary sources, which, while limited in their perspective, can provide incomplete but broadly accurate observational data. Indeed, classical and medieval writers consistently demonstrate an awareness of spatio-temporal risk profiles, consistently identifying greater pathogenic risk in swampy/marshy spaces, especially during the late summer/early autumn. Hence the long-standing association of the rise of Sirius, the ‘Dog Star’ in late July with increasing episodes of disease (Celsus, 3.3.2-3.8.2; Galen, A Method of Medicine to Glaucon 1.9-10; Hippocrates, Humors 12.8-10; Airs, Waters, Places 7.28; Epidemics 1.3). While premodern sources lack accurate knowledge of the causal agent behind these infections, they are keenly aware of a correlation of space and time with rising risk of infection, morbidity and mortality (Grmek, Reference Grmek1989; Sallares, Reference Sallares2002; Nicovich, Reference Nicovich2025).

Additionally, while the surviving textual evidence from the premodern Mediterranean varies widely in its description of disease, many classical and medieval sources provide direct reference to the kinds of intermittent fevers indicative of various malarial species (quotidian, tertian, quartan, etc.), providing strong evidence for malaria in those instances. However, most ancient writers use more ambiguous language, instead describing more general symptoms, like ‘fevers’, ‘dysenteries’ and ‘disease of the head’, that can refer to any number of illnesses. Often they explicitly tie the disease to the local environment, citing the proximity of ‘marshes’, ‘swamps’ or other wetlands or the ‘insalubrious’ or ‘unhealthy’ nature of a place. Classical miasma and humoral theory are pervasive causal explanations for illness in the premodern Mediterranean, and in the face of modern germ theory these ancient models fall apart. Yet ancient writers are correct in observing the spatio-temporal risk of infection present in low-lying areas around the Mediterranean, a reflection of the habitat and life cycle of the vector species propagating in these lowlands. Despite the inaccuracies inherent to the surviving source materials, they still capture the accurate realities, that certain environments, in certain annual climatic conditions, support and promote endemic species of malaria and, in turn, higher risk of infection, morbidity and mortality. Some scholars disregard ancient references to such ‘unhealthy’ environments, viewing them as simply a vestige of discredited miasma theory. This can lead to cautious approaches, such as Newfield’s study of malaria in Merovingian Francia, which regards only specific diagnostic language related to intermittent fevers as reliable indicators of malaria. Yet, by his own admission, this only establishes a minimal baseline and certainly underestimates the overall impact of malaria on given populations (Newfield, Reference Newfield2017, 51–54).

In approaching the extant source material, in regions well-known for harbouring pestilential wetlands, and during the warmest months of the summer and early fall, any reference to febrile diseases or disease specifically attributed to environmental factors has a high prospect of involving some species of malaria. Therefore, this study follows the approach of Piers Mitchell, who utilizes a more expansive model of inquiry, combining current pathological science with critical assessment of the surviving sources, with a view to identifying infectious diseases within the understood limitations of the source material (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Anastasiou and Syon2011; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2011a, Reference Mitchell, Glaze and Nance2011b; MacLeod et al., Reference MacLeod, Jones, Di Giuseppe, Caminade and Morse2015). No doubt other diseases were present within these environments, with enteric fevers offering a similar spatio-temporal risk profile. As such we cannot positively state, with scientific precision, that the references noted in this study are absolute evidence of malaria; that is impossible given the noted limitations of the textual evidence. At the same time, the known spatio-temporal association of endemic malaria in these environments, along with the immunologically vulnerable character of many travellers crossing the regions, makes the risk of malaria infection a significant prospect in these contexts. In the summer and early fall, when temperatures are warmest and mosquito propagation at its height, any mention of febrile symptoms or illnesses directly attributed to spatial and/or climatic factors has a high probability of involving some species of malaria. Comorbidities, especially gastro-intestinal and respiratory infections, were also quite likely in these circumstances, especially in the crowded, unsanitary conditions found in military camps. Scholars have recently coined the term syndemic to refer to the synergistic interaction of multiple epidemic diseases within a common socio-environmental context, and this emerging concept is highly relevant in regions of endemic malaria. Much recent scholarships notes how malaria rarely occurs in isolation from other pathogens, and such syndemic interactions only heighten overall morbidity, mortality and the social impacts that follow (Faure, Reference Faure2014; Singer et al., Reference Singer, Bulled, Ostrach and Mendenhall2017; Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Mendenhall, Trostle and Kawachi2017; Newfield, Reference Newfield2022; Perry and Gowland, Reference Perry and Gowland2022). The tendency towards comorbidity made malaria a fulcrum, tipping an epidemic from causing widespread morbidity towards becoming a syndemic, resulting in mass mortality.

Map 2: Anatolia/Asia Minor, with modelled malaria risk.

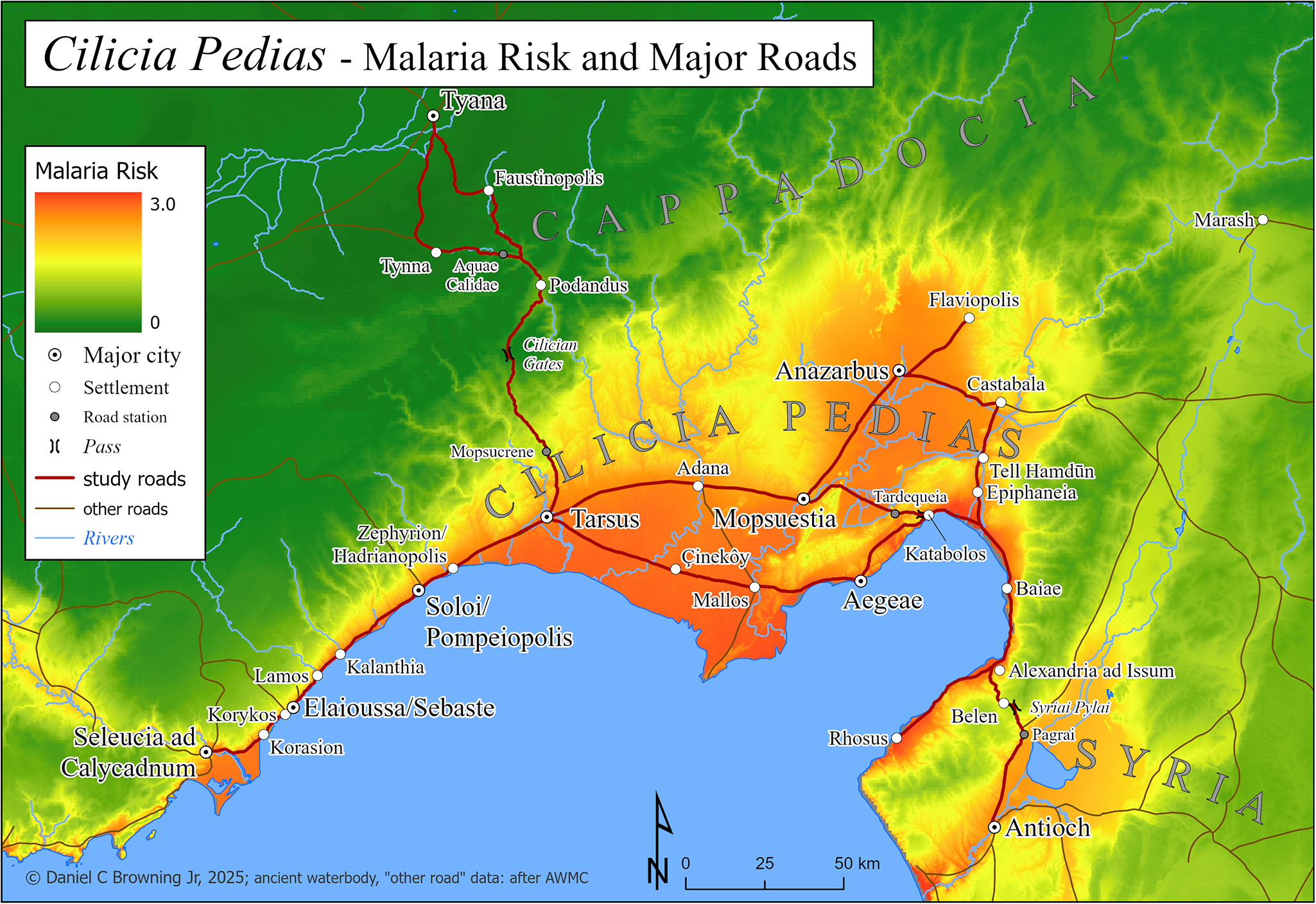

Map 3: Cilicia Pedias, with modelled malaria risk, major roads and road stations.

In following this approach, source material for periods up to the effective eradication of malaria in Anatolia/Asia Minor, especially Cilicia Pedias, were examined for reasonable descriptions of possible outbreaks, including specific references to fevers, as well as references to disease events specifically tied by the source to the local environment and/or season. These were collated by date into 3 categories: (1) references to outbreaks or symptoms in the region without spatial specificity; (2) references to symptoms in a specified location; and (3) references to apparent infection related to an itinerary through the region. The study was limited to Cilicia Pedias for lack of convincing evidence for travel-related infection elsewhere in Asia Minor.

Integration of source material with malaria risk model output

For textual accounts of malarial symptoms within the region of Cilicia, and in category 1, maps of modelled risk provide general correlation, but quantification of that risk was not possible without location specificity. For the historical sources with spatial certainty – that is, categories 2 and 3 – malaria risk, as determined by the model, was calculated for the given locations. These results were collated into table form.

For category 2, where potential malaria is indicated at a particular location, modelled risk was calculated as the mean within set radiuses from the centre of the given place. This was accomplished in ArcGIS Pro by creating buffers of 1, 2 and 5 km from the centres of the established locations. These buffers were virtually overlaid with the malaria model layer and statistics calculated via the Zonal Statistics as Table tool.

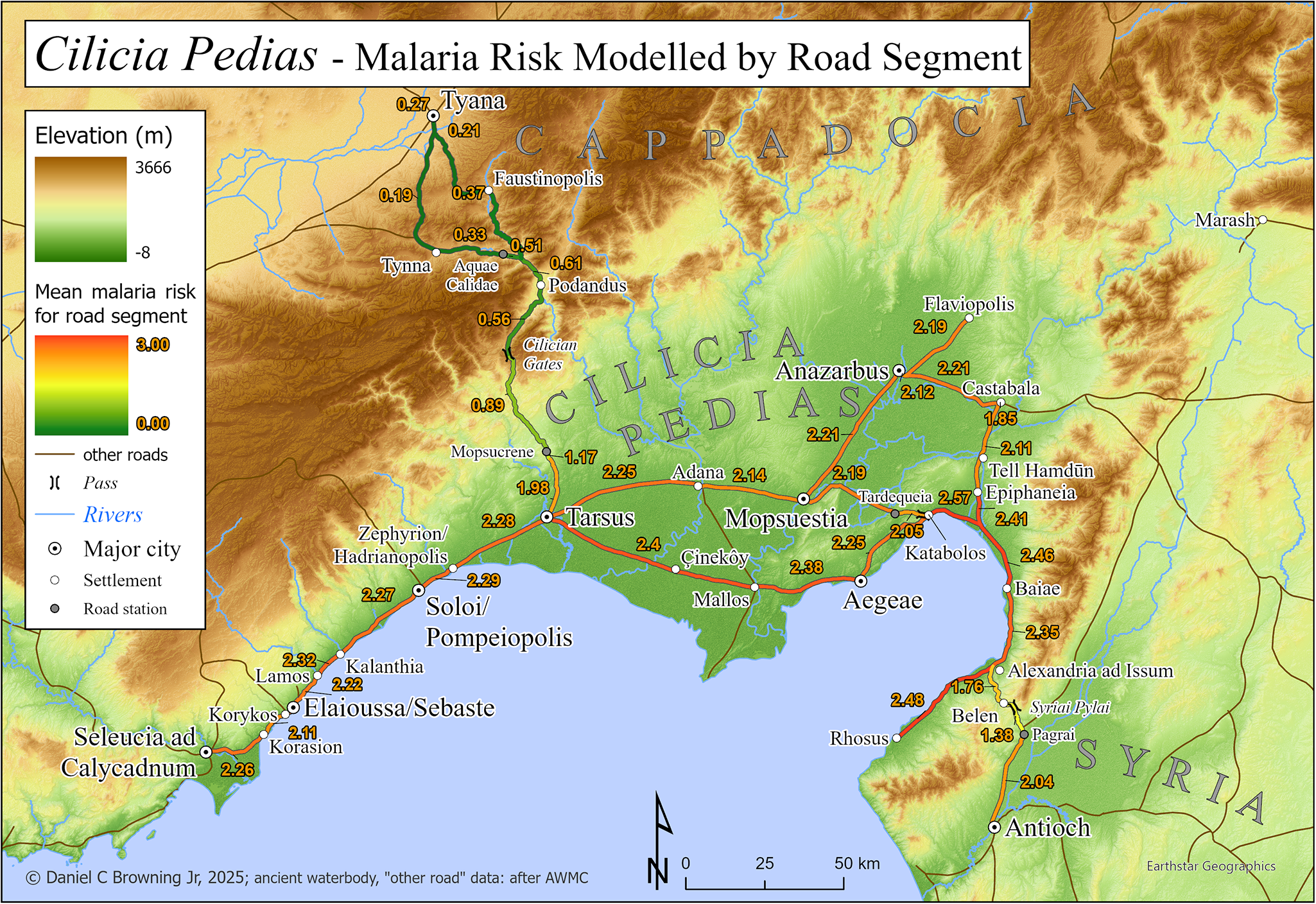

For category 3, where itineraries are given by the sources, risk for the given journey was assigned using the same concept. In this case, malaria risk was calculated for each road segment with the 542 m vector flight distance buffer, as described above. The Zonal Statistics as Table tool produced maximum, minimum, and mean risk calculations for each segment. These figures provide a metric for evaluating risk along roads when coupled with the distance travelled for each segment. They were assembled in tabular form below and illustrated by Map 4. For each historical incident in this category, itineraries were determined from the sources and individual road segments combined into the full path. Zonal statistics calculated for the entire buffered itinerary, including minimum, maximum and mean modelled risk, serve as metrics for evaluation.

Results: map and tables

Map 2 depicts Anatolia/Asia Minor with a basemap of the malaria risk model, showing calculated risk on a continuous scale of 0–3. A box below centre shows the extent of the following maps of Cilicia Pedias.

Calculated malaria risk for Cilicia Pedias is the basemap for Map 3, which shows locations indicated by sources and cited in the text, as well as the major roads for which improved paths were created and malaria risk was calculated. Other minor or uncertain roads, including those leading away from the region, are also depicted.

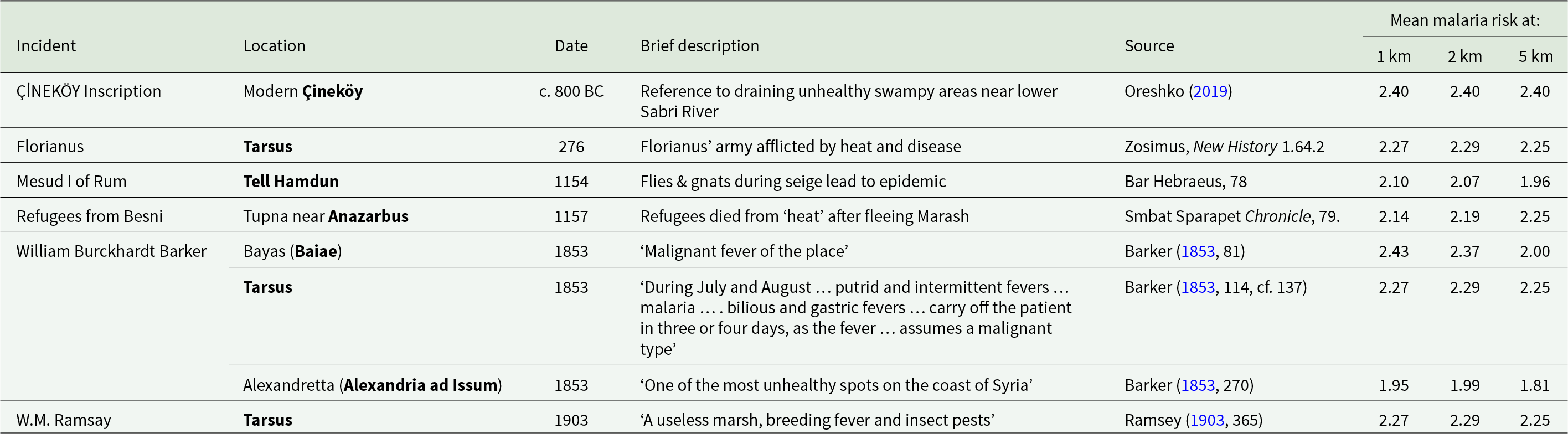

Table 1 presents historical sources containing reference to apparent malaria infection at specific locations by date; with columns for location, date/season, brief description, source citation and mean malaria risk at set radiuses from the location centre.

Table 1. Historical references to apparent malarial conditions at specific locations in Cilicia Pedias, with modelled mean risk around central location point

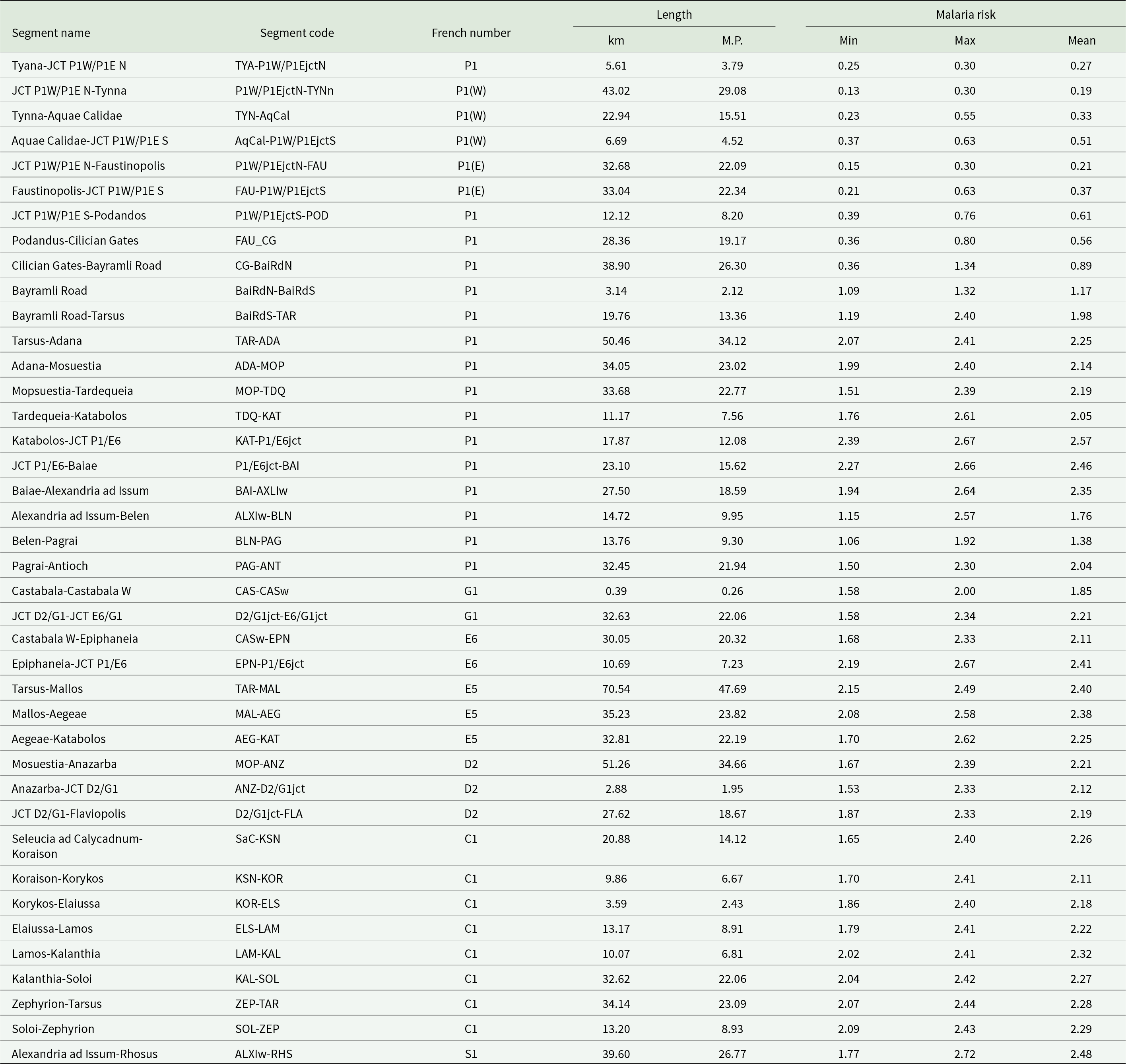

Table 2 presents the refined Roman road segments, per the above method, as divided between significant known road points and junctions. The arrangement is by the numbering system established by French (Reference French2016), and geographically from NW to SE. Each segment is named by its endpoints and accompanied by its code designation, length in km and Roman miles (mille passus = M.P.) and diagnostic malaria risk statistics. The latter were calculated with the Zonal Statistics tool for overlays of the 542 m buffered path of each section with the malaria risk model. Risk numbers are provided for the minimum, maximum and mean for each segment.

Table 2. Malaria risk for buffered Roman road path segments, arranged NW to SE by the numbering system established by French (Reference French2016)

Map 4 has the same extent as Map 3, with elevation as the basemap, showing the major roads and their mean calculated malaria risk for each significant segment from Table 2.

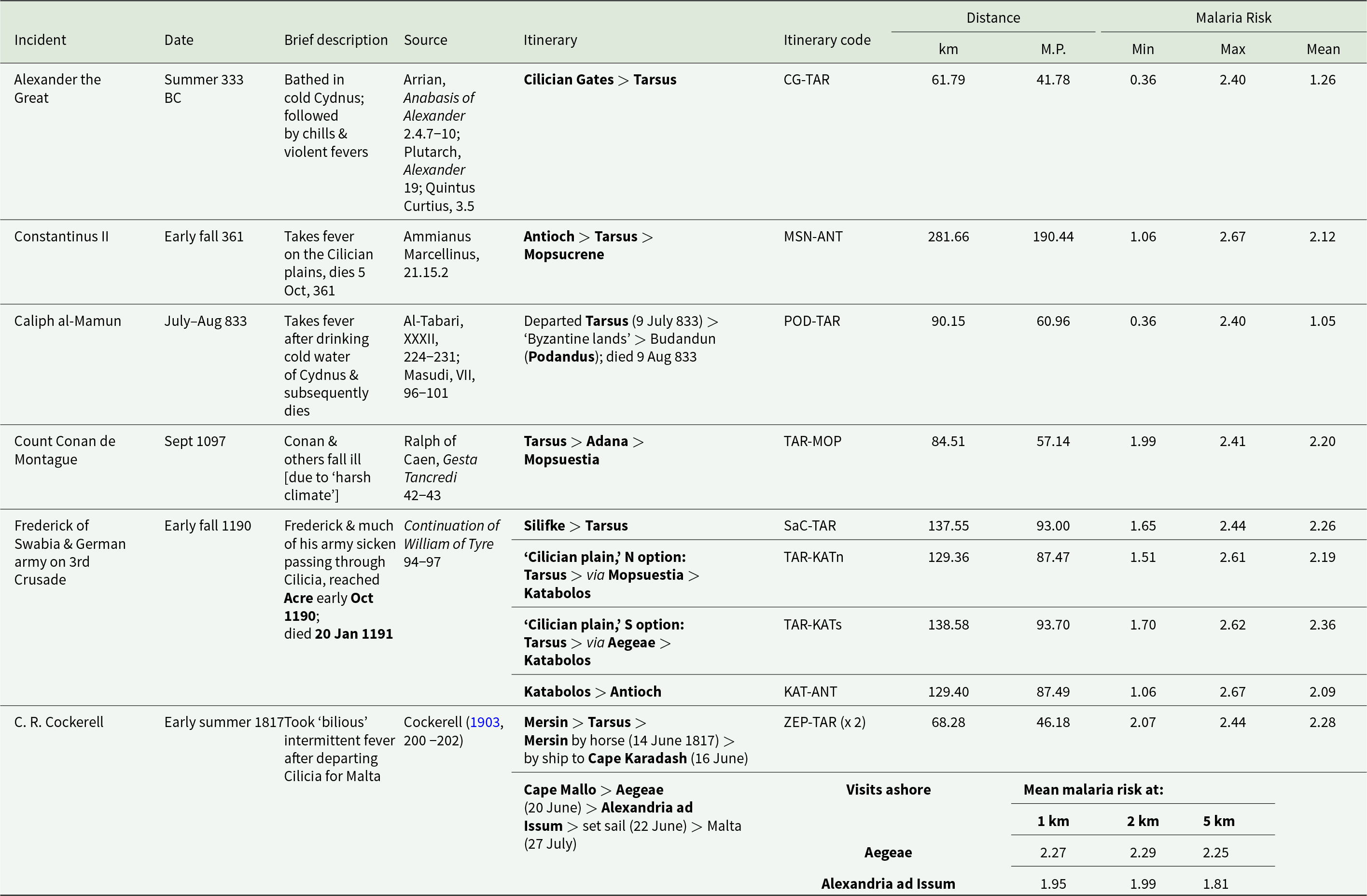

Table 3 presents historical sources containing reference to apparent malaria infection relating to a stated or clearly implied itinerary. Incidents are arranged by date (including season or months if known), with brief description, relevant itinerary points in and around Cilicia Pedias, source citation and calculated data for malaria risk along the full itinerary path. This includes: distance travelled in km and Roman miles (M.P.) and modelled malaria risk figures for the maximum, minimum and mean within the buffered path of the listed itinerary.

Table 3. Historical references to apparent malarial infections related to travel through Cilicia Pedias, with minimum, maximum and mean malaria risks along the full itineraries, and distances of exposure

Discussion

Malaria risk in Cilicia

Map 2 graphically demonstrates that one of the most extensive and severe high-risk areas in the Asia Minor lies in Cilicia, particularly Cilicia Pedias (Map 2, extent indicator inset), the region of interest. The larger scale Map 3 extends that demonstration to the local level within Flat Cilicia and confirms the high malaria risk in the immediate vicinities of places associated with primary sources for fevers, their treatment and tales of miraculous healing thereof.

Malaria-like incidents at specific locations in Cilicia Pedias

The Çineköy inscription

Table 1 shows the close correlation between the modelled risk found in Map 3 and historical references to premodern fever/disease episodes in the region at specific sites, often at critical transit nodes along the roads crossing the area. The 9th century BCE bilingual inscription, in which the Luwian king Warika reports the draining of unhealthy swampland, was recovered at modern Çineköy south of Adana. The mean modelled risks within 1, 2 and 5 km are the same high figure of 2.40.

The nondescript alluvial plain around Çineköy has a high water-table today, and 1 interpreter opines that the statue of the god Tarhunza and inscribed base (Figure 1) ‘seems never to have reached its intended destination but to have been abandoned’ (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins, Heffron, Stone and Worthington2017, 214–215). This conclusion must result from the lack of any substantial settlement remains at the find spot. However, the reconstructed road path between Tarsus and Mallos, using the LCP-directed process described above, passes quite close to Çineköy, as seen in Maps 3 and 4. Since ancient roads continued in use from one era to the next, it is reasonable to suppose that this monument was purposely established on the main highway through the lands ‘reclaimed’ from the swamps by Warika’s efforts. As Tarhunza was a storm god – and thus a fertility deity that controlled crop yields – his ox-cart shaped base (bearing the inscription) may have symbolized the movement of crops along the roads from the renewed fields to their city markets.

Tarsus and Florianus

Tarsus, the principal Cilician metropolitan centre through much of antiquity, also exhibits high mean risk scores within a 5 km (2.25) radius around the city, making any visit there in the summer and fall dangerous. Such danger was on display during the Roman civil wars of the 3rd century CE, when the Roman general Florianus led several European legions into Cilicia to oppose Probus and his Syrian legions in 275 CE. While encamped at Tarsus and ‘unaccustomed to the heat’, a reference to the pestilential nature of Cilician summers, much of the army fell sick and many died. Subsequent unrest led to a mutiny and Florianus’s death (Zosimus, 1.64.2). It is unlikely that the Danubian legions accompanying Florianus were suffering from mass heat-stroke, given that healthy, active adults such as soldiers or athletes are known to naturally acclimatize to increased heat within 10 days (Malgoyre et al., Reference Malgoyre, Siracusa, Tardo-Dino, Garcia–Vicencio, Koulmann, Epstein and Charlot2020). Rather, one should reasonably view this as an environmental reference to the pestilential nature of Tarsus’ environs.

Map 4: Cilicia Pedias, with elevation and modelled malaria risk for road segments.

Endemic malaria continued to be a serious problem in Tarsus into the modern era; the Orientalist travel writer William Burckhardt Barker and the noted biblical scholar W.M. Ramsay both regarded Tarsus as a thoroughly unhealthy place, with Ramsay directly associating the region’s propensity to produce fevers with its swarms of insects (Barker, Reference Barker1853, 114; Ramsey, Reference Ramsey1903, 365).

Mesud I of Rûm and Refugees from Besni

The eastern portion of the Cilician plains exhibited similarly high rates of disease burden. Malaria-like epidemics plagued the military camps of the Seljuk Turks in eastern Cilicia during the 12th century CE, as evidenced in medieval Armenian sources. In 1154, Mesud I, Sultan of Rûm, raided first around Anazarbus and then camped by Tell Hamdun (Smbat Sparapet, 78), both locales scoring in the upper third of risk profile as shown in Table 1. Bar Hebreaus reports, ‘the Lord smote them with a plague of gnats and flies which was like unto that of the Egyptians in the days of Moses the Great,’ the only direct reference to insects in any of the extant ancient sources. An epidemic accompanied the swarms of insects; ‘And in these days the air which they breathed became foul and stinking, and they and their horses became sick. And when they saw that the plague had begun among them, they abandoned all their treasure and fled’ (Bar Hebraeus, 321).

Shortly thereafter, in 1157, refugees from Besni, in the mountains above modern Adiyaman, were resettled at Tupna on the plains near Anazarbus. Many of the settlers quickly ‘died from the heat’, likely reflecting the lack of acquired immunity among the mountain dwellers to the malaria species endemic in the plain (Smbat Sparapet, 79). The model risk numbers at Anazarbus increase with higher radiuses from the center (from 2.14 at 1 km, to 2.25 at 5 km) because the dramatic and safer heights of the city’s acropolis give way immediately to the surrounding flat alluvial plain.

The southeastern reaches of Cilicia, in shadow of the Amanus mountains, also harboured significant danger of infection, attested both by the risk model and modern travellers. Alexandria ad Issum (modern Iskenderun) marked Alexander the Great’s victory over the Persians at nearby Issus (333 BCE) and remains a significant port even to the present. But it sits in wet, unhealthy lowlands, and Barker regarded it was one of the worst spots for disease in the entire region (Barker, Reference Barker1853, 270), an assertion born out by its high score in the model. The looming Amanus range causes a slight decrease of risk at 5 km, converse to the situation at Anazarbus. Bayas (Baiae), 20 km north of Iskenderun, fared no better in the model or in the regard of Barker, who refers to the ‘malignant fevers’ present there, likely eliciting the presence of P. falciparum, the deadliest of the malaria species (Barker, Reference Barker1853, 81).

Malaria associated with itineraries in or through Cilicia Pedias

Data produced by the road risk model also conform with the anecdotal evidence, a testament to the perilous nature of the disease landscape travellers encountered while traversing Flat Cilicia. This is clear when comparing known itineraries with the risk differentials travellers faced during their transits.

Alexander the Great

By far the most famous tale of infection in Cilicia is that of Alexander the Great. Alexander and his army crossed the Cilician Gates and descended into the plains in the summer, 333 BCE (Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander 2.4.3-6). The full itinerary from the Gates to Tarsus has a relatively low mean risk of 1.26, as shown in Table 3. Table 2, however, demonstrates that the risk increases as one moves south from the Cilician Gates to the foothills of the Taurus near Mopsucrene (segment codes CG-BaiRdN and BaiRdN-BaiRdS). The segment from just south of Mopsucrene to Tarsus (BaiRdS-TAR), an expected full day of travel, shows significantly higher exposure risk. The story of Alexander sickening after bathing in the cold waters of the Cydnus (Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander 2.4.7-10; Plutarch, Alexander 19.1-5; Quintus Curtius, 3.5), likely reflects the malarial nature of the approach to Tarsus or the already demonstrated threat of the city environs itself.

Constantinus II

The outcome of a civil war in the Late Roman period was determined by the Cilician environment. In early fall 361, Emperor Constantius II abandoned his planned campaign against Sassanian Persia to face the rebellion of his Caesar Julian, who was quickly marching down the Danube towards Constantinople. Constantius moved his army from Edessa in upper Mesopotamia to Antioch, and crossed the Amanus into Cilicia Pedias via the Syrian Gates. From Alexandria ad Issum, Constantius had to cross the length of the Cilician plain to Tarsus, turning north there towards the Cilician Gates. The Cilician portion of his trip, totalling more than 280 km, is the longest in the current dataset, also featuring the highest modelled risk score in this study (2.67).

Given the lengthy journey through such an ‘unhealthy’ region, during the most dangerous time of year, it is little surprise that Constantius fell ill with a fever somewhere on the plain. The emperor’s illness worsened as they travelled, and his army only made it as far as Mopsucrene, the final station on the Via Tauri between Tarsus and the Cilician gates. Constantius finally succumbed to his fevers there on 3 November, 361, leaving Julian as sole emperor (Ammianus Marcellinus, 21.15.2-3).

Caliph al- Ma’mun

The Abbasid Caliph al-Ma’mun campaigned in Byzantine Anatolia in the summer of 833. He departed from Tarsus on 9 July and made an initial foray into Cappadocia before returning to Podandus, the first major station north of the Cilician Gates, to await word from envoys. The chronicler al-Tabari reports that while al-Ma’mun’s court picnicked beside the clear mountain stream, the Caliph and his party drank from the frigid waters and soon thereafter they fell ill with fevers. Al-Masudi adds details of ague; chills, shivering and profuse sweating. Al-Ma’mum died of his fevers on 9 August, 833 (al-Tabari, XXXII, 224-225; Masudi, VII, 96-101), and the planned campaign against Byzantium was abandoned.

The Caliph’s route from Tarsus through the Cilician Gates to Pondandus is clear, and has a relatively low mean risk of 1.05. His movements in the ‘Byzantine lands’ of Cappadocia are not detailed, but almost certainly focused on the areas around Tyana, where his son al-‛Abbas was constructing a military camp (Treadgold, Reference Treadgold1988, 279-281). As Map 4 shows, the 2 road options from Podandus to Tyana have near-equally low risk segments, and the Cappadocian hinterland would be similarly safe. In this case, however, al-Tabari provides the date for al-Ma’mun’s departure from Tarsus and the date for this death; a 1-month span during the malarial season which must include the Cappadocian foray, the onset of fever back in Podandus, his illness and eventual demise. Al-Tabari further informs us that when his illness worsened, al-Ma’mun sent for his son, who arrived and ‘stayed with his father for some days’ (al-Tabari, XXXII, 225). As Tyana was normally a 2-day journey, the onset of symptoms must be appreciably more than ‘some days’ before the Caliph’s death. These details and the Plasmodium incubation periods suggest that al-Ma’mun’s itinerary after leaving the environs of Tarsus was much less a malaria risk than was his period in Tarsus itself or transit to that city from Syria – which was probably identical to the high risk path of Constantius I, above. As with Alexander more than a millennia before, the cold Cilician stream waters were tacitly blamed for the caliph’s illness but the modelled risk exposure and timing make malaria infection the likely culprit.

The first Crusade

During the height of the Crusader era in the 11th–13th centuries, Cilicia was a core transit zone for multiple crusades, as well as a centre of geopolitical contention between Byzantines, Turks, Armenians and Crusaders (Nicovich, Reference Nicovich2025). A large part of the army of the First Crusade passed through Cilicia in September 1097, crossing the Cilician Gates down to Tarsus, and then eastward on the Tarsus – Adana – Mopsuestia road, encountering high mean malaria risk (2.20) along the way. Many crusaders were ‘afflicted by weakness’ as a result the harsh climate (Ralph of Caen, 42).

Frederick of Swabia and the German army on the third Crusade

The most notable Crusade disease event in Cilicia occurred in the summer of 1190. Frederick Barbarossa’s crusading army had successfully crossed Anatolia, only for the emperor to drown while crossing the Saleph River near Silifke on 10 June. His son, Frederick of Swabia, led the remaining German forces from Silifke across Cilicia towards Antioch. The exact route is not given, but Table 3 lists all options and their relative risks. The initial stage of the journey, from Silifke to Tarsus clearly followed the old Roman coastal highway for over 135 km, with a high mean risk score (2.26) the entire multi-day journey. From Tarsus Frederick could have taken a northern route via Adana to Kastabolos, or a southerly path along the coast via Aegae to Kastabolos, both of roughly similar length (130–140 km), and exhibiting similar mean infection risk scores (2.19–2.36). The final stage from Kastabolos to Antioch is only marginally less risky (2.09) according to the model.

The total time and length of transit across the plains, combined with the high modelled risk of infection, make it unsurprising that a major epidemic broke out among the German force, afflicting even its commander: ‘Frederick … was severely weakened by illness when he arrived in the plain of Cilicia, and he could not climb up into the mountains, so weak was he from the sickness that afflicted him.’ Frederick had to be carried into Antioch, by which time much of his army had fallen ill with high mortality: ‘so the knighthood of Germany began to diminish’ (Continuation of William of Tyre 89; Johnson, Reference Johnson, Wolff and Hazard1969). Medieval German armies often campaigned in malaria-ridden Italy (Reilly, Reference Reilly2022, 78–92), developing some level of acquired immunity among survivors, but Barbarossa’s forces had not campaigned there in the 15 years prior to the Third Crusade. The younger Crusaders in Frederick of Swabia’s remaining army thus possessed little exposure to endemic malaria. Frederick eventually arrived at Acre in October 1190, but he remained severely ill, likely including secondary or comorbid infections, leading to his death in January 1191.

C. R. Cockerell

A more modern example of infection on Cilicia roads and ports illustrates the complex interplay of risk along interconnected terrestrial roadways with regional maritime networks. In June 1817, the British archaeologist C. R. Cockerell took a brief detour through southwestern Cilicia, by ship. Desiring to visit Tarsus, he journeyed there and back by horseback from Mersin over 3 days (14–16 June), a total journey of about 70 km across a landscape with a mean risk score of 2.26. From Mersin he sailed eastwards along the Cilicia coast, going ashore at Cape Mallo, Ayas and Iskenderun, before departing by sea for Malta on 22 June. Cockerell arrived in Malta on 18 July ill with a self-described ‘bilious’ fever and suffered intermittently for several weeks (Cockerell, Reference Cockerell and Cockerell1903, 200–202). Given the varying incubation periods for Plasmodium species, it seems most likely that Cockerell contracted either P. vivax or P. malariae on the Mersin-Tarsus Road, or in one of the Cilician ports subsequently visited, all with high modelled risk scores.

Conclusions

Extan historical data suggest that Plasmodium species, while likely present earlier, were widespread in Cilicia Pedias from the classical periods until modern eradication. The GIS-based malaria risk model correlates strongly with textual evidence for malarial infection generally as well as at specific named locations in the region. Endemic strains of P. malariae, P. vivax and P. falciparum obviously impacted the native populations of the Cilician plains, including lifestyle choices evidenced at certain periods.

This malarial landscape posed a greater potential threat to persons from beyond its confines and not previously exposed to the local strains of Plasmodium. Such immune-naïve persons were especially vulnerable to malaria when crossing Cilicia Pedias by roads which exposed them to long stretches of endemic territory. The peril was especially acute during the high-risk ‘Dog Days’ of summer and autumn. A GIS-based technique for more accurate reconstruction of the ancient and medieval road network in the region permitted extension of the malaria risk model to quantify the exposure dangers for travellers on those paths. The model again provides a strong correlation between predicted malaria risk and textual evidence for infections related to itineraries.

Particularly notable is the impact on military forces and their leadership, whether Macedonians under Alexander, the legions of Florianus or Emperor Constantius II, the Muslim army of al-Ma’mun, or medieval German crusaders. Though separated by many centuries and fighting entirely different conflicts, each of these faced an additional and invisible enemy. Thus, P. vivax and P. falciparum inflicted high levels of morbidity and mortality on these forces which no doubt influenced or, in some cases, effectively decided outcomes of their campaigns.

By extending an existing GIS model for malaria risk in antiquity to Cilicia Pedias, and particularly its ancient roadways, this study provides a replicable model for quantification, visualization and assessment of properly identified historical sources providing textual evidence for malarial infection. It also serves as a case study for examination of malaria risk in an ancient environment, and its impact on outcomes for those moving through it. The approach is viable for application to other regions of the Mediterranean, and similar methods should be useful in other regional contexts.

Author contributions

DB and MN conceived and designed the study as an extension and collaboration of earlier work. DB created the ancient road dataset for the study area and extended the existing malaria risk model to produce risk on roads, as well as the resulting data. JMN researched and identified historical sources with probable references to malarial infection as established the criteria for evaluating them. While each initially wrote the sections pertaining to the foregoing tasks, both JMN and DB coauthored and edited the final article text.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.