Highlights

-

• Examining 108 bilingual speakers’ brain responses to morphologically complex word forms

-

• Testing the same bilinguals in both their native (German) and their second language (English)

-

• Results: striking L1/L2 contrasts within the same bilingual speakers’ ERPs; individuals’ ERPs vary along negativity-/positivity-dominant effects

-

• Novel finding: individual differences limited by linguistic constraints

1. Introduction

Bilingual language performance is marked by considerable variability across individuals. While some bilinguals achieve high-level proficiency not only in their first language (L1) grammar but also in their second language (L2) grammar, others exhibit persistent differences (e.g., Bosch et al., Reference Bosch, Veríssimo and Clahsen2019; Foote, Reference Foote2010; Meulman et al., Reference Meulman, Wieling, Sprenger, Stowe and Schmid2015). Previous research suggests that variability among bilingual speakers’ knowledge and processing of grammar is influenced by factors such as language proficiency, age of acquisition, working memory or verbal fluency (e.g., Grey, Reference Grey2023; Hopp, Reference Hopp2015; Kidd et al., Reference Kidd, Donnelly and Christiansen2018; Veríssimo et al., Reference Veríssimo, Heyer, Jacob and Clahsen2018). But, do these findings mean that variability in a bilingual speaker is entirely shaped by individual experience and cognitive factors, or could it be that there are inherent properties of grammar and/or patterns of stable language processing that resist modulations of individual differences and in this way limit variability in the bilingual’s linguistic performance? The present study addresses this question by examining brain responses to morphologically complex word forms in bilingual speakers’ L1 (viz. German) and their L2 (viz. English), that is, in the same individuals. Using event-related potentials (ERPs), we seek to identify systematic patterns of variability as well as potential constraints on individual variability, with the aim of contributing to a deeper understanding of bilingual language processing.

Recent psycholinguistic research has shown that ERPs provide particularly detailed information about individual profiles of language processing. Tanner (Reference Tanner2019), for example, identified two subgroups of individuals from ERPs in response to violations of subject–verb agreement in L1 English: individuals who displayed a negativity-dominant profile and individuals with a positivity-dominant one. Tanner concluded that there is marked and systematic variability regarding the dominance of two qualitatively different ERP components associated with language processing, the N400 and the P600 component (see also Beatty-Martínez et al., Reference Beatty-Martínez, Bruni, Bajo and Dussias2021; Fromont et al., Reference Fromont, Royle and Steinhauer2020; Hohlfeld et al., Reference Hohlfeld, Martín-Loeches and Sommer2019; Qi et al., Reference Qi, Beach, Finn, Minas, Goetz, Chan and Gabrieli2017; Tanner & Van Hell, Reference Tanner and van Hell2014; Tanner et al., Reference Tanner, Mclaughlin, Herschensohn and Osterhout2013; Vieitez et al., Reference Vieitez, Padrón, Díaz-Lago, de Dios-Flores and Fraga2024 for related research on syntactic and lexical-semantic phenomena). There is also one ERP study that examined individual ERP profiles for morphological processing, namely processing of noun plurals in L1 German (Ciaccio et al., Reference Ciaccio, Bürki and Clahsen2023). The results revealed dissociable patterns of ERP responses to morphological violations, individuals with a negativity-dominant profile (left-anterior negativity [LAN]/N400) and those with a positivity-dominant one (P600), thus replicating previous findings on other linguistic anomalies. As Ciaccio et al.’s (Reference Ciaccio, Bürki and Clahsen2023) study is the only one that examined brain signatures of morphological processing with respect to individual differences, more evidence is needed before any generalized conclusions can be drawn.

The specific linguistic phenomenon we examined in the present study is regular versus irregular verb inflection in English and German. The question of how regular versus irregular inflected word forms are mentally represented, processed and acquired is controversial, with – broadly speaking – two competing viewpoints, dual- and single-mechanism accounts. Dual-mechanism accounts (e.g., Clahsen, Reference Clahsen1999; Pinker & Ullman, Reference Pinker and Ullman2002; Ullman, Reference Ullman2004) hold that irregular forms are directly retrieved from memory, whereas regular forms are composed from their component parts (stem + affix). Single-mechanism accounts hold that regular and irregular inflections employ the same representational and processing mechanisms, either associative patterns or schemas (e.g., Bybee, Reference Bybee1995; McClelland & Patterson, Reference McClelland and Patterson2002) or rule-like operations (e.g., Stockall & Marantz, Reference Stockall and Marantz2006; Yang, Reference Yang2010). There are numerous experimental studies of regular versus irregular inflection using a variety of behavioral tasks and measures (e.g., acceptability judgments, primed and unprimed lexical decision, self-paced reading), but the theoretical interpretation of behavioral studies remains controversial, with some researchers interpreting the results as providing support for the distinctions posited by dual-mechanism accounts (e.g., Clahsen, Reference Clahsen, Hippisley and Stump2016) and others favoring associative-based accounts (e.g., McClelland & Patterson, Reference McClelland and Patterson2002). Similarities and differences between regular and irregular inflections have also been investigated in a number of neurocognitive studies using a variety of brain-related measures (ERP, MEG, fMRI) testing both native and non-native speakers in languages such as English (e.g., Newman et al., Reference Newman, Ullman, Pancheva, Waligura and Neville2007), German (e.g., Penke et al., Reference Penke, Weyerts, Gross, Zander, Münte and Clahsen1997), Spanish (e.g., Linares et al., Reference Linares, Rodriguez-Fornells and Clahsen2006), Italian (e.g., Gross et al., Reference Gross, Say, Kleingers, Clahsen and Münte1998), Catalan (e.g., Rodriguez-Fornells et al., Reference Rodriguez-Fornells, Clahsen, Lleo, Zaake and Münte2001), Finnish (e.g., Leminen et al., Reference Leminen, Leminen, Lehtonen, Nevalainen, Ylinen, Kimppa and Kujala2011) and Russian (e.g., Slioussar et al., Reference Slioussar, Korotkov, Cherednichenko, Chernigovskaya and Kireev2024). On the basis of a detailed review of these and other brain studies of morphological processing, Leminen et al. (Reference Leminen, Smolka, Dunabeitia and Pliatsikas2019, Reference Matuschek, Kliegl, Vasishth, Baayen and Bates37) conclude that ‘most studies seem to support accounts based on dual mechanisms in charge of processing regular and irregularly inflected forms’. Likewise, Royle and Steinhauer’s (Reference Royle, Steinhauer, Grimaldi, Brattico and Shtyrov2023, 59) review leads them to conclude that regular morphological forms elicit different brain signals from irregular forms, a contrast ‘reminiscent of the distinction between lexicon-based and rule-based processing’.

Most of the evidence for neurocognitive signatures of morphological processing comes from studies of L1 native speakers using ERPs. Three key ERP components have been linked to morphology, (i) a LAN, elicited by violations of regular morphological processes (e.g., Penke et al., Reference Penke, Weyerts, Gross, Zander, Münte and Clahsen1997; Schremm et al., Reference Schremm, Novén, Horne and Roll2019), (ii) an N400, elicited by violations of irregular morphology (e.g., Rodriguez-Fornells et al., Reference Rodriguez-Fornells, Clahsen, Lleo, Zaake and Münte2001; Weyerts et al., Reference Weyerts, Penke, Dohrn, Clahsen and Münte1997) and (iii) a P600, elicited for both morphological violations (e.g., Ciaccio et al., Reference Ciaccio, Bürki and Clahsen2023; Lück et al., Reference Lück, Hahne and Clahsen2006). Violations of regular morphology (‘regularizations’) are formed by adding a regular affix to a verb or noun that requires an irregular one (e.g., *speak-ed vs. spoken). The LAN elicited in such cases is reminiscent of the LAN obtained for syntactic violations (e.g., Barber & Carreiras, Reference Barber and Carreiras2005) and indicates that such forms are processed as combinatorial violations, that is, as incorrect pairings of a stem and a segmented regular ending; see Molinaro et al. (Reference Molinaro, Barber and Carreiras2011) for review. By contrast, the N400 for violations of irregular morphology (‘irregularizations’, e.g., *walken), that is, a regular verb (to walk) appearing with an incorrect (irregular) form, suggests that such forms are processed as undecomposed wholes yielding an ERP effect (viz. N400) that is characteristic of lexical violations. The P600 has typically been reported for studies investigating morphological violations in a sentential context (rather than in a word list), suggesting that an incorrectly inflected word form may (also) be processed at the sentence level, that is, repaired or reanalyzed before it is integrated with the rest of the sentence.

To the best of our knowledge, there is only one study (Hahne et al., Reference Hahne, Müller and Clahsen2006) that employed the ERP violation paradigm to examine morphological processing in non-native L2 speakers. Adult L1 Russian speakers with intermediate L2 (German) proficiency were tested with respect to violations of regular and irregular verb and noun inflections. This study yielded mixed results, a bilateral anterior negativity for regularizations of verb (but not of noun) inflection and an enhanced N400-like negativity for irregularizations. In addition, a late P600 effect was reported for both violation types. Hahne et al. (Reference Hahne, Müller and Clahsen2006, 121) concluded from these findings that the two morphological ‘processing routes (lexical storage and morphological decomposition) are also employed by L2 learners’. Note, however, that the L2 learners’ brain responses were more variable and less coherent than those of L1 speakers. While a focal LAN was consistently found for regularizations of both verb and noun inflections in L1 speakers (Ciaccio et al., Reference Ciaccio, Bürki and Clahsen2023; Lück et al., Reference Lück, Hahne and Clahsen2006; Penke et al., Reference Penke, Weyerts, Gross, Zander, Münte and Clahsen1997; Weyerts et al., Reference Weyerts, Penke, Dohrn, Clahsen and Münte1997), L2 speakers presented with a more broadly distributed anterior negativity for incorrect regularized verb forms, which could not be replicated for noun inflection. These differences could mean that L2 processing of morphologically complex words relies less on the decomposition route than L1 processing.

1.1. Participle formation in German and English

We investigated past participle formation in L1 German and L2 English, which have largely similar morphological forms in the two languages and a straightforward contrast between regular – highly productive and internally structured forms – and irregular – lexically restricted whole-word forms. Participle formation in German and English involves two endings, −(e)n for participle forms of so-called strong (= irregular) verbs, and -t (in German) and –(e)d (in English) for participle forms of weak (= regular) verbs. Irregular verbs undergo (phonologically unpredictable) stem changes in both English and German, for example, stehlen (infinitive) – gestohlen (participle) – ‘to steal’ – ‘stolen’. There are about 160 common simplex verbs that fall into the strong (= irregular) class in both languages. In addition, there is a small class of so-called mixed verbs which take the (regular) participle ending, −(e)t in German and –(e)d in English, but also show stem changes in the participle, for example, denken – gedacht ‘to think’ – ‘thought’ – ‘thought’.

There are also some differences between the two languages in this domain. Firstly, −n appears on some irregular verbs in English (e.g., stolen) but on all of them in German. Secondly, unlike German, English has about 60 so-called no-change verbs without any alterations in the past tense or participle (e.g., to cut). Thirdly, German participles are typically augmented with ge-, namely when the verbal stem is stressed on the first syllable. Since German verbal stems are often stressed on the first syllable, the (unstressed) ge- prefix is highly frequent. Fourthly, while past participles in English (together with auxiliaries) explicitly tie past actions or events to the present emphasizing, for example, continuity (e.g., ‘I have lived in England for ten years – and still do.’), the corresponding ‘Perfekt’ in German (Ich habe 10 Jahre in England gelebt) typically describes completed actions without emphasizing their connection to the present. Despite these differences, the formal properties of participles in German and English are highly similar. Crucially for the present study, participles in both languages involve a contrast between morphologically structured, productive (‘regular’) forms and lexically restricted, less productive (‘irregular’) whole-word forms.

While there are (to the best of our knowledge) no previous neurocognitive studies of participle formation for English, there are two ERP violation studies testing German stimuli, which served as a model for the present study (Hahne et al., Reference Hahne, Müller and Clahsen2006; Penke et al., Reference Penke, Weyerts, Gross, Zander, Münte and Clahsen1997). In both studies, correct regular and irregular participles of German were compared with incorrect ones; the latter had -n on verbs that require -t participles (*getanz-en ‘dance-n’) or -t on verbs that require -n (*gelad-et ‘load-ed’). Penke et al. (Reference Penke, Weyerts, Gross, Zander, Münte and Clahsen1997) presented the critical words visually in three different versions to adult German L1 speakers, as part of a simple sentence, in a word list, and embedded in a story. The ERP responses were consistent across the three versions of the experiment: regularizations (*gelad-et) elicited a LAN, while irregularizations led to no differences relative to the corresponding correct forms. Penke et al. (Reference Penke, Weyerts, Gross, Zander, Münte and Clahsen1997) interpreted their findings as supporting a dual-mechanism account of morphological processing. Hahne et al. (Reference Hahne, Müller and Clahsen2006) replicated the ‘sentence’ experiment with a group of 18 adult native Russian L2 speakers of German. Instead of the focal LAN that was consistently found for L1 speakers (Ciaccio et al., Reference Ciaccio, Bürki and Clahsen2023; Lück et al., Reference Lück, Hahne and Clahsen2006; Penke et al., Reference Penke, Weyerts, Gross, Zander, Münte and Clahsen1997; Weyerts et al., Reference Weyerts, Penke, Dohrn, Clahsen and Münte1997), regularizations elicited a broad anterior negativity (and a P600), and irregularizations yielded a (statistically marginal) centroparietal negativity, possibly an N400. Assuming that L1 speakers’ focal LAN signals reliance on morphological (stem + affix) decomposition processes, the L2 speakers’ ERP responses may indicate less reliance on such processes.

1.2. The present study

A number of previous neurocognitive studies (e.g., Ciaccio et al., Reference Ciaccio, Bürki and Clahsen2023; Tanner, Reference Tanner2019; Tanner & van Hell, Reference Tanner and van Hell2014) have shown that complementing standard group-level analyses of ERPs with analyses of inter-individual differences can lead to a better understanding of language-related brain responses. The present study pursues this approach by examining late bilingual speakers’ brain responses to morphologically complex word forms. Our main aim is to determine how individual variability in language-related ERPs is constrained by two linguistic factors, (i) language status, viz. whether a given language is a participant’s native L1 or his/her non-native L2, and (ii) morphological process/representation, viz. whether a given morphological form engages (rule-based) regular or (lexically based) irregular inflectional processes.

We adopted the design of two previous ERP experiments (Hahne et al., Reference Hahne, Müller and Clahsen2006; Penke et al., Reference Penke, Weyerts, Gross, Zander, Münte and Clahsen1997) that compared brain responses to (visually presented) morphological regularizations and irregularizations in German, specifically regular versus irregular past participle forms. To allow for direct comparisons of the same individuals in their L1 German and their L2 English, we adapted the experiment to English, making sure that the design and the materials for the two languages were as comparable as possible. We predicted that our group-level analyses for the L1 (German) would replicate the ERP effects reported in previous L1 studies of morphological processing (Leminen et al., Reference Leminen, Smolka, Dunabeitia and Pliatsikas2019; Royle & Steinhauer, Reference Royle, Steinhauer, Grimaldi, Brattico and Shtyrov2023), namely LAN-type effects for regularizations and N400-like effects for lexically based violations (viz. irregularizations). These ERP effects may be accompanied by a P600 for both types of violation, reflecting later processes when an incorrect word form is integrated with the rest of the sentence. For the L2, the group-level results were expected to yield N400s and/or P600s in response to the violations, but not the focal LAN that was reported for regularizations in participants’ native L1. We also predicted inter-individual variability in participants’ ERP responses to morphological violations for both their L1 and L2, in line with previous ERP research on individual differences (e.g., Ciaccio et al., Reference Ciaccio, Bürki and Clahsen2023; Tanner & van Hell, Reference Tanner and van Hell2014). Specifically, previous studies led us to expect two different types of individuals with different polarity in their ERPs, (i) negativity-dominant individuals showing a large negativity in the LAN/N400 time window (relative to a small or no positivity in the P600 time window) and (ii) positivity-dominant individuals with a predominantly positive ERP effect.

As a specific novel contribution, the present study seeks to determine possible linguistic constraints on individual variability in language processing. We hypothesize that the inherent properties of language and their neural representation that are stable and consistent across different individuals limit variability in participants’ linguistic performance. One such constraint is language status. Following previous research (e.g., Clahsen & Felser, Reference Clahsen and Felser2006, Reference Clahsen and Felser2018) indicating L1/L2 differences, we predicted a focal LAN for (late) bilinguals’ L1 (but not their L2), irrespective of whether an individual is negativity-dominant or positivity-dominant, indicating that the L1/L2 contrast is stable across individuals. The second factor we manipulated concerns the linguistic phenomenon under study. Given previous research indicating neural differences between (rule-based) regular and (lexically based) irregular inflection in L1 morphological processing (e.g., Clahsen, Reference Clahsen and Wunderlich2006), we predicted that regularizations and irregularizations elicit contrasting ERP responses in our participants’ L1, irrespective of whether an individual is negativity-dominant or positivity-dominant, suggesting that neural representations of morphology constrain individual variability.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

We tested 108 L1 German speakers (76 women; 30 men, 2 non-binary; mean age: 25.54 years, SD = 4.17, range = 20–37) in two experiments, one on their L1 (German) and the other on their L2 (English). All participants provided informed consent before participating in the study and received 35 € each for participating. They were all right-handed, had completed the equivalent of German high-school level education, were living in Germany at the time of testing, reported reading in English to some extent in their daily lives and were either university graduates or enrolled as university students at the time of recruitment. All participants learned English after early childhood in a formal school setting, with a mean age of onset of 7.97 years (SD = 2.13, range = 2.5–15) and self-reported to be intermediate to advanced non-native speakers of English. As to be expected from German school leavers, the majority of participants (n = 69) spoke other languages: French: 27, Spanish: 22, Russian: 5, other: 15. To assess their English proficiency, we used a modified version of the Oxford Quick Placement Test (OQPT; Oxford University Press & Cambridge ESOL, 2001), consisting of 60 multiple-choice items and administered through Google Forms. Participants’ mean score was 49.49 (SD = 5.5; range: 35–59), roughly corresponding to a group mean level of C1 of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe, 2001); B1: 6, B2: 30, C1: 51, C2: 21. Recall that a number of recent studies reported bilingual individuals’ N400/P600 ERP responses to be affected by verbal fluency and working memory (e.g., Grey, Reference Grey2023; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Oines and Miyake2018). For the present study, we tested participants’ verbal fluency in English using a semantic fluency task (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Luk and Bialystok2010; Patra et al., Reference Patra, Bose and Marinis2020) with two categories: animals and food. Participants were instructed to name as many items as possible within 60 seconds for each category. The mean number of words named per category, averaged across the two categories, was 18.21 (SD = 4.67, range = 7.0–32.5). Finally, to assess their working memory, the standard digit span backward task (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1997) was administered. Participants’ mean score was 5.55 (SD = 1.55; range: 2–7).

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. German

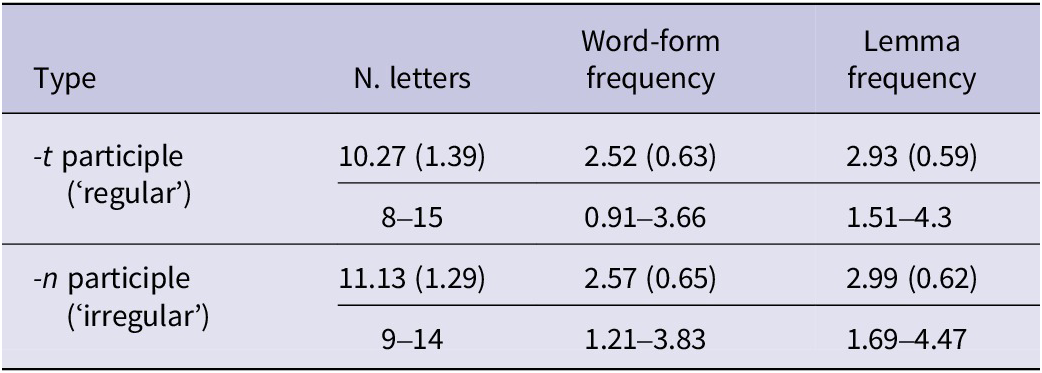

We created materials using the design of those in Penke et al. (Reference Penke, Weyerts, Gross, Zander, Münte and Clahsen1997) as a model. The critical stimuli differed with respect to verb type (weak/regular, strong/irregular) and in the participle endings, −t versus −n. This resulted in a 2×2 design with the factors Participle Type (−t vs −n; between-item) and Correctness (correct vs. incorrect; within-item); see Table 1 for an example stimulus set. Sixty items per Participle Type and Correctness were tested.

Table 1. Example stimulus material (German)

As vowel changes are common among the participle forms of irregular verbs in both German and English, we included both irregular verbs with and without vowel changes in their participle forms. To generate enough critical stimuli, we made use of prefix–verb formation, a highly productive process in German. This process combines a prefix such as durch ‘through’, auf ‘on’, an ‘at’, with a base verb, for example, laden ‘to load’; see Table 1. All critical stimuli consist of such prefix–base verb combinations. The (regular and irregular) verbs chosen for the two participle types were matched as closely as possible for length in letters and for word-form and lemma frequency; see Table 2. Word-form and lemma frequency were extracted from the dlex database (Heister et al., Reference Heister, Würzner, Bubenzer, Pohl, Hanneforth, Geyken and Kliegl2011) and are provided in the Zipf scale, which approximately spans from 1 to 7; values below 3 indicate relatively low frequency, while values above 4 indicate high frequency (van Heuven et al., Reference van Heuven, Mandera, Keuleers and Brysbaert2014). The critical participles were presented embedded in sentences, which contained seven to eight words with the participle as the last word in the sentence (as required in German main clauses).

Table 2. Summary of the German item characteristics (mean, SD and range)

Each of the 60 participles in each of the four conditions was presented three times to each participant in different sentence contexts. This resulted in a total of 360 experimental items each in two conditions (correct/incorrect), distributed across two presentation lists following a Latin-Square design to ensure that no participant encountered the same experimental item in both conditions. Each presentation list included 360 experimental trials, containing half correct and half incorrect participle forms, distributed equally among the two participle types (−t vs. −n).

As the critical participles were always the final words in the sentences presented, we performed an additional materials evaluation test to examine whether the two verb forms (−t vs. −n participles) differed in their contextual predictability. Fifteen adult German native speakers were asked to complete the experimental sentences (e.g., Der starke Wind hat die Wolken schnell …) with a participle form. There were three experimental versions (with five participants each) so that each participant saw only one sentence context for each participle form to be elicited. Participants completed the sentence fragments with the targeted verb form in 59 cases, of which 31 were −t participles and 28 −n participles. The differences in predictability for the two verb types were small and non-significant (two-tailed, p = 0.72).

2.2.2. English

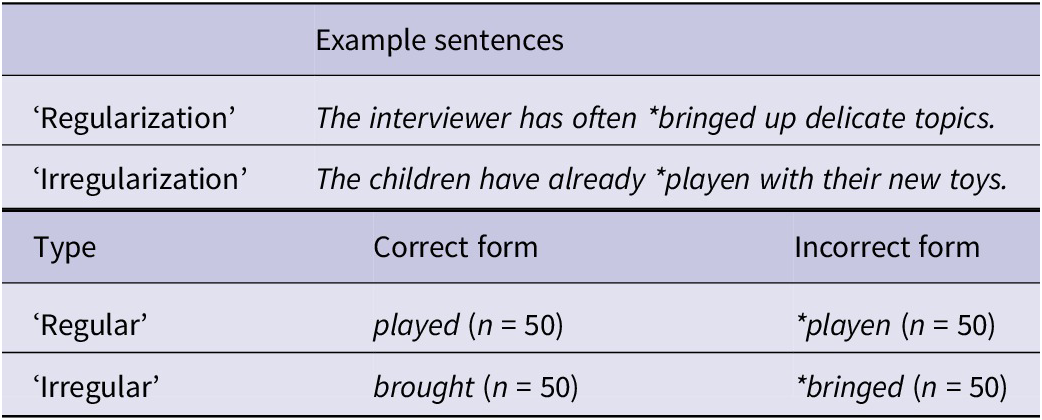

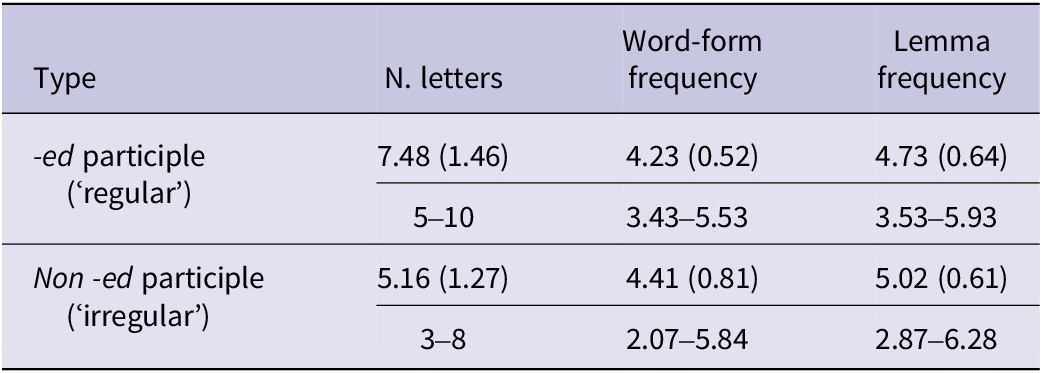

We created English materials parallel to the German ones, varying Participle Type (regular vs. irregular) and Correctness (correct vs. incorrect) yielding 50 items per Participle Type and Correctness; see Table 3 for an example stimulus set. Due to the considerable number of no-change verbs (e.g., to put), there were fewer suitable verbs in English for our experiment than in German, hence the contrast between the number of items for English and German. The verbs for the two participle types were matched as closely as possible for length in letters and for word-form and lemma frequency. Word-form and lemma frequency were extracted from the SUBTLEXus database (Brysbaert & New, Reference Brysbaert and New2009) and are provided in the Zipf scale; see Table 4. The critical participle forms were again embedded in declarative sentences, which contained six to eight words. To make the present perfect sound more natural, all experimental sentences included aspectual/temporal adverbs, such as already, often, just, etc. Each of the 50 participles in each of the four conditions was presented three times in different sentence contexts. This resulted in a total of 300 experimental items each in two conditions (correct/incorrect) distributed equally among two presentation lists following a Latin-Square design ensuring that participants did not encounter the same experimental item in both conditions.

Table 3. Example stimulus material (English)

Table 4. Summary of the English item characteristics (mean, SD and range)

To assess participants’ familiarity with English participle forms before coming to the lab for the ERP experiments, they participated in an online test using Google Forms consisting of 65 multiple-choice items, each presented as a sentence with a missing verb participle. Participants were asked to select the correct participle from three options, of which only one was correct. For example, they were shown the sentence: ‘He has recently __________ me a job’ with the answer choices: offeren, offered, offer. Participants were instructed to complete the test without using dictionaries or other resources. Their overall accuracy scores were high, indicating familiarity with the correct participle forms (mean = 59.77 (91.95%), SD = 6.3; range: 36–65 (55.4% – 100%)).

2.3. Procedure

Each participant was individually tested. Before coming to the lab, participants filled out (i) a biographic questionnaire, (ii) the OQPT distributed to participants via Google Forms, (iii) the English participle test and (iv) the Working Memory Test (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1997). The first three tasks were completed without supervision, whereas the Working Memory Test was administered under controlled conditions. The German and the English ERP experiments took place in a soundproof cabin with each experiment lasting approximately 1 hour. The session, totaling about 150 minutes (including participant’s preparation), included a break between the two language experiments and two breaks within each language experiment. For half of the participants the German experiment and for the other half the English experiment was presented first. Prior to the ERP experiments, participants performed the (above-mentioned) English Verbal Fluency Test in the lab. The materials for the ERP experiments were then presented on a computer monitor using Presentation software (version 16.2, Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc.). Each participant was assigned to one of the two presentation lists.

Each trial began with a blank screen, presented for 700 ms, followed by a fixation cross presented for 3,500 ms. During this time, participants were instructed to blink if needed. Next, the experimental sentences were visually presented word by word in the center of the screen. To allow for longer reading times in the L2 than in the L1, each word remained on screen for 400 ms in the German and for 450 ms in the English experiment, preceded by a 200-ms blank screen. Words at the end of a sentence appeared with a full stop. Presentation times were chosen on the basis of pilot testing with three participants in the two languages, none of whom participated in the main experiments. Following Penke et al. (Reference Penke, Weyerts, Gross, Zander, Münte and Clahsen1997), we assigned a probe verification task to participants. After blocks of 10 experimental sentences, a ‘control’ sentence appeared on screen together with the question whether this sentence was included in the previous block of items. This remained on screen until participants provided a response. Control sentences were included to ensure that participants were actually reading the sentences during the experiment. There were 36 control sentences in the German and 30 in the English experiment, of which half were exact repetitions of one of the sentences presented in the previous block (requiring a ‘yes’ response), and half were a slightly modified version of one of the previous sentences (requiring a ‘no’ response).

Before the ERP experiments, participants received a short training containing three practice sentences. They were informed that they would see a series of sentences presented word by word and that a question would appear after some of the sentences. They were instructed to read all the sentences attentively, to answer the questions as accurately as possible by pressing a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ button and to relax and minimize body and eye movements during the ERP recording. Participants could take a short break after, respectively, one third and two thirds of the experimental trials. The experimental procedure was carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and was accepted by the local ethics committee.

2.4. ERP acquisition and preprocessing

The ERP of participants was recorded using Brain Vision Recorder software (version 1.20.0701) and the amplifier BrainAmp DC (Brain Products, GmbH). A total of 64 electrodes were positioned according to the international 10–20 system using active electrodes (ActiCap; Brain Products, GmbH): FP1, FP2, AF7, AF3, AF4, AF8, F7, F5, F3, F1, Fz, F2, F4, F6, F8, FT7, FC5, FC3, FC1, FC2, FC4, FC6, FT8, FT9, FT10, T7, C5, C3, C1, Cz, C2, C4, C6, T8, TP9, TP7, CP5, CP3, CP1, CPz, CP2, CP4, CP6, TP8, TP10, P7, P3, P1, Pz, P4, P6, P8, P5, P2, PO9, PO7, PO3, POz, PO4, PO8, PO10, O1, Oz and O2. FCz was used as the reference electrode during the recording. The ERP signal was recorded continuously with an online band-pass filter between 0.1 and 70 Hz, with a sampling rate of 500 Hz. Electrode impedances were kept below 20 k Ω (following guidelines for ActiCaps).

Before preprocessing ERP data, we analyzed participants’ scores on the probe verification task. The mean accuracy for German was 79% (SD: 3.19) and 85.6% (SD: 2.19) for English. To ensure that only the ERP data from participants who paid reasonable attention to the task were included in our data analyses, we excluded individuals with an error rate of 40% and above on the probe verification task from any further analysis. We preprocessed the signal using MNE Python (V3.10.5; Gramfort et al., Reference Gramfort, Luessi, Larson, Engemann, Strohmeier, Brodbeck and Hämäläinen2013). The continuous signal was filtered with a zero-phase 0.01–40-Hz FIR band-pass filter. After this, signals were re-referenced offline to the average of the left and right mastoids (TP09 and TP10), and the continuous signal was segmented into epochs of 1,400 ms, from −200 ms before the onset of the critical participles to 1,200 ms after onset, to capture possible late P600 effects. Artifacts related to blinks or horizontal eye movements were automatically identified and corrected using independent components analysis (ICA). Prior to ICA, a small number of channels were removed either due to consistently poor signal quality or because they were not included in the planned analyses. After ICA, the epoched data were also visually inspected for any remaining noisy channels, which were interpolated if showing sudden peaks or excessive noise during the entire recording (mean of channels interpolated by participant = 4.65, range = 0–21). We also excluded epochs that presented a peak-to-peak amplitude exceeding 150 μV. Finally, epochs were then baseline-corrected using a 200-ms window before stimulus onset. At the end of this procedure, we excluded 18 datasets (11 for German and 7 for English) from participants whose remaining number of epochs were below two thirds of the total number of experimental trials. As data preprocessing and cleaning were conducted separately for each language, we ended up with a dataset from 96 L1 German (out of 108) and 100 L2 English (out of 108) participants for the group-level analyses. For the analyses of inter-individual variability, we only included individuals (n = 92) with usable ERP datasets in both languages. The entire preprocessing process, including exclusion of participants, was decided on and performed prior to analyzing any data.

2.5. Data analysis

ERP data analysis involved two steps: a group-level analysis and an analysis of inter-individual variability. Both types of analyses involved the same time windows and regions of interest (ROI) for both languages, L1 German and L2 English. Before conducting any descriptive or inferential statistics on the data, we selected two time windows of interest, an early time window between 300 and 500 ms, and a later time window between 500 and 800 ms, both after stimulus (i.e., participle form) onset. These two time windows were adopted from previous ERP studies on inter-individual variability in this linguistic domain (Ciaccio et al., Reference Ciaccio, Bürki and Clahsen2023; Tanner, Reference Tanner2019; Tanner & van Hell, Reference Tanner and van Hell2014). The ROI were also chosen on the basis of these earlier studies. To test for LAN effects, we selected a left anterior ROI (F5, F7, FC3, FC5, FT7), in which we would expect a significant LAN for regularizations only. We additionally selected a right anterior ROI (F6, F8, FC4, FC6, FT8) to check the lateralization of the LAN. To test for N400 and P600 effects, we used a large, centroparietal ROI at which N400 and P600 are typically maximal (C3, Cz, C4, CP1, CP2, P3, Pz, P4). Average signal amplitudes in the two time windows were computed separately for each electrode in each trial (see Frömer et al., Reference Frömer, Maier and Abdel Rahman2018). We subsequently averaged the signal of the electrodes in each of the ROI, in order to obtain one data point for each participant and trial in each ROI. These data were then used as the dependent variable in the statistical analyses.

For the group-level analysis, we fitted a series of linear mixed-effect models to test for LAN, N400 and P600 effects. For analyses of the LAN, the dependent variable was the average signal per participant and trial in the left-anterior ROI. To inspect the laterality of the effect, we further considered the right-anterior ROI. In the case of the N400 and P600 analyses, the dependent variable was the average signal per trial in the centroparietal ROI in, respectively, the 300–500-ms and the 500–800-ms time windows. All models contained the fixed effects Correctness (incorrect vs. correct forms) plus, when required or applicable, Participle Form (regular, irregular), Language (L1 German, L2 English) and Hemisphere (right vs. left), as well as the interaction terms between all factors.

All models were fitted using the package lme4 (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R (version 4.2.2; R Core Team, 2020). Parameters were estimated with restricted maximum likelihood. We used deviation coding for all the contrasts for the fixed effects (i.e., −0.5, 0.5). As a consequence, the intercept represents the grand mean, and estimates for the predictors represent the mean differences in μV between the levels of the predictor. All models included random intercepts for participants and items. Random slopes by participant and item were step-wise tested for inclusion via likelihood ratio tests (see Matuschek et al., Reference Matuschek, Kliegl, Vasishth, Baayen and Bates2017). We started with the intercept-only model. We tested for inclusion of each relevant random slope separately, by comparing the model with and without the additional slope. The random slope was included only if it significantly improved the model fit. If more than one slope produced a significantly better model, we first added only the one that produced the greatest improvement (as measured by the Akaike information criterion), to prevent convergence issues. With the resulting model, we then repeated the procedure, testing for inclusion of each additional random slope, until no further slope improved the fit. We calculated p-values with the package ‘lmerTest’ (Kuznetsova et al., Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017). More detailed information about each model is provided in the Results section.

For the analyses of individual differences, we used the same time windows and ROI as for the group-level analyses. Adopting the analyses from Tanner and van Hell (Reference Tanner and van Hell2014), we calculated difference scores (= mean amplitude for correct forms minus mean amplitude for incorrect forms) for each individual, separately for the two participle types, within the centroparietal ROI, firstly in the early (300–500 ms) time window and secondly effect sizes (= mean amplitude for incorrect forms minus mean amplitude for correct forms) in the 500–800 ms window. For both scores, the former ‘early negativity score’ and the latter ‘late positivity score’, positive values indicate larger effect magnitudes, and negative values indicate smaller effect magnitudes. Individual early negativity scores and late positivity scores were first submitted to a simple correlation analysis, to determine whether these scores yielded distinct types of participants. Then, we divided participants into groups of ‘positivity-dominant’ and ‘negativity-dominant’ individuals using the Response Dominance Index (RDI; Tanner & van Hell, Reference Tanner and van Hell2014), which is supposed to provide an index reflecting the predominance of negative-going or positive-going ERPs across the two selected time windows:

A negative RDI score indicates that an individual is characterized by a predominance of negative-going ERPs, while a positive RDI score indicates predominance of positive-going ERPs. Based on the RDI, participants were grouped into ‘negativity-dominant’ and ‘positivity dominant’ individuals. This was done separately for each participle type based on the different results we obtained for these two conditions at the group level. Subsequently, we employed the same procedure as for the group-level analyses to examine the ERP responses in the two subgroups of participants and the two languages. For the negativity-dominant participants, the main goal of this analysis was to test for possible LAN effects elicited by the morphological violations in the individuals’ two languages. For the positivity-dominant individuals, we tested for a broadly distributed positivity (P600) in response to morphological violations in the individuals’ two languages. Furthermore, we examined possible links between the individuals’ ERP responses and their working memory, their semantic fluency and their general language skills in English using correlation tests between these measures and the individuals’ early negativity, late positivity and RDI scores.

3. Results

3.1. Group performance

The results of the group-level analyses with the grand mean ERP waveforms and the full statistical model outputs are provided in the Supplementary Material at the following repository: https://osf.io/puaky/?view_only=898ca9ab3ee7479682a5b784ba03ecff.

A number of previous studies reported an enhanced N400 in response to morphological violations. We therefore examined our data for an enhanced N400 in the two languages. A model with Participle Type (regular, irregular), Correctness (correct, incorrect) and Language (L1 German, L2 English) was fitted to the data from the centroparietal ROI in the 300–500-ms time window (Table S1 in the Supplementary Material), which yielded a significant three-way interaction between these factors (b = 0.869, SE = 0.404, t = 2.153, p = 0.032) as well as interactions of Correctness and Language and of Language and Participle Type, suggesting differences in the N400 between the two languages for the two violation types. However, follow-up analyses did not reveal any significant effects, for either the two types of violation or the two languages (Tables S2–S5 in the Supplementary Material), that is, no evidence for or against a modulation of the N400 at the group level.

Previous research found a LAN for regularizations in L1, but not in L2 speakers, indicating less reliance on morphological decomposition in L2 than in L1 processing. Visual inspection of the plots in Figures S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Material suggests a LAN for regularizations in German (Figure S1A in the Supplementary Material) but not in L2 English (Figure S2A in the Supplementary Material). To confirm a difference between the two languages with respect to the LAN, we fitted a model with the factors Language, Participle Type and Correctness to the data of the left-anterior ROI (300–500 ms); see Table S6 in the Supplementary Material. This showed a three-way interaction between all factors (b = 4.218, SE = 0.457, t = 9.239, p < 0.001) as well as interactions between Language by Correctness, and Language by Participle Type, indicating L1/L2 differences in the violation effect for the two participle types within the left-anterior ROI. Next, we examined the two languages separately with respect to LAN effects. For the German L1 data, we fitted a model including Correctness, Participle Type and Hemisphere (left vs. right) as dependent variables to the data from the left and right anterior ROI in the early time window. The model revealed a significant three-way interaction between all dependent variables (b = −9.144, SE = 0.419, t = −21.810, p < 0.001) as well as an interaction between Correctness and Hemisphere (Table S7 in the Supplementary Material). To further test for differences between the two types of violation within the L1, two separate models were fitted on regularizations and irregularizations using the averaged German data from the left-anterior ROI, with Correctness as a fixed effect (Tables S8 and S9 in the Supplementary Material). We found a significant effect of Correctness for regularizations (b = −2.862, SE = 0.342, t = −8.375, p < 0.001) and a smaller effect for irregularizations (b = 1.469, SE = 0.27, t = 5.45, p < 0.01). However, while the negative coefficient for regularizations signals an increased negativity compared to the baseline, irregularizations elicited a more positive waveform relative to the baseline. The topographic plots in Figure 1 illustrate the LAN effect for regularizations in L1 German.

Figure 1. Topographical distribution of the violation effect (subtraction incorrect-correct forms) in the entire participant group’s L1 (German) for the 300–500-ms time window, for the two violation types (left panel: regularizations, right panel: irregularizations).

To examine the L2 data with respect to a LAN, we fitted a model including Correctness, Participle Type and Hemisphere to the L2 data of the entire participant group for the 300–500-ms time window (Table S10 in the Supplementary Material). This model did not yield any significant effects or interactions for either regularizations or irregularizations in either the LH or RH.

Finally, we examined the later time window (500–800 ms) with respect to a P600 for both types of violation in both languages, as several previous studies obtained a P600 in response to morphological violations in both the L1 and the L2. We first fitted a model on the averaged signal from the centroparietal ROI with Participle Type, Correctness and Language as fixed effects. In addition to effects of Correctness, Language and Participle Type, we found two-way interactions of Correctness by Language (b = −1.124, SE = 0.180, t = −6.259, p < 0.001) and Participle Type by Language (b = −0.560, SE = 0.187, t = −2.991, p = 0.003), suggesting differences between the L1 and the L2 in their P600 responses to participle violations; see Table S11 Supplementary Material. To confirm this, we fitted two additional models for the centroparietal ROI and the 500–800-ms time window with Participle Type and Correctness as fixed effects, separately for the L1 and L2 data (Tables S12 and S13 Supplementary Material). The model for the L2 data yielded significant effects for both Participle Type (b = 0.520, SE = 0.145, t = 3.578, p < 0.001) and Correctness (b = 1.215, SE = 0.145, t = 8.394, p < 0.001) without any interactions, indicating an increased positivity (P600) for incorrect participle forms in L2 English. By contrast, the model for the L1 data did not yield any significant results.

Summarizing, the group-level analysis revealed a LAN for regularizations in the L1, but not the L2, and a P600 for both violation types (viz. regularizations and irregularizations) in the L2, but not the L1.

3.2. Inter-individual variability

Previous ERP research reported individual differences in response to syntactic and morphological violations, with some participants predominantly showing an enhanced negativity and others showing a positivity (e.g., Ciaccio et al., Reference Ciaccio, Bürki and Clahsen2023; Tanner & van Hell, Reference Tanner and van Hell2014). Here, we studied individual differences in bilingual speakers’ ERP responses to morphological violations in both their native language and their second language. We first examined potential correlations between participants’ early negativity and late positivity effect magnitudes. These analyses yielded negative correlations for both types of violation in both languages, L1 German (regularizations: r = −0.702, p < 0.00001; irregularizations: r = −0.733, p < 0.0001) and L2 English (regularizations: r = −0.703, p < 0.00001; irregularizations: r = −0.733, p < 0.0001), indicating a negative association between the two ERP responses. Individuals who showed large negativities in the early time window tended to show small P600 effects and vice versa; see Figure 2 for illustration. Given the negative correlations between participants’ early negativity and late positivity effects, we then divided the participants into ‘negativity-dominant’ and ‘positivity-dominant’ individuals (using their RDIs) for the two types of violation. To further determine whether this grouping holds across the individuals’ two languages, we tested whether individuals who came out as ‘negativity-dominant’ in their L1 were also ‘negativity-dominant’ in their L2, and likewise for ‘positivity-dominant’ individuals. Correlation tests on the participants’ RDI scores revealed that this was not the case, for either of the two violation conditions (‘regular’: r = −0.106, p = 0.308; ‘irregular’: r = 0.070, p = 0.5).

Figure 2. Distribution of the participants’ early negativity and late positivity amplitudes in their L1 and L2 for each participle type (left panel: L1, right panel: L2, upper panel: regularizations, lower panel: irregularizations).

Furthermore, some previous studies found correlations between an individual’s working memory and the N400/P600 ERP components (e.g., Kim et al., Reference Kim, Oines and Miyake2018). We therefore examined potential correlations between participants’ working memory scores and the individuals’ ERP measures – their RDI and the magnitudes of their early negativity and late positivity in the two languages. We did not find any correlation, either for the L1 (RDI: r = 0.101, p = 0.166; early negativity: r = −0.105, p = 0.152; late positivity: r = 0.081, p = 0.267) or for the L2 (RDI: r = 0.048, p = 0.506; early negativity: r = −0.041, p = 0.575; late positivity: r = 0.047, p = 0.514). We also examined potential correlations between the individuals’ ERP measures in the L2 and their semantic fluency test scores as well as their general language skills in English (as measured through the QOPT). We found weak to moderate correlations between these variables, positive ones between fluency and RDI (r = 0.222, p = 0.002), fluency and late positivity (r = 0.203, p = 0.005), QOPT and RDI (r = 0.174, p = 0.015), and QOPT and late positivity (r = 0.207, p = 0.004), as well as a negative one between fluency and early negativity (r: −0.207, p = 0.004).

In the following, we present separate analyses of the ERP data from ‘negativity-dominant’ and ‘positivity-dominant’ individuals. The ERP waveforms (Figures S3A–S6B Supplementary Material and the statistical model outputs are found in the Supplementary Material (Tables S14–S24 Supplementary Material).

3.2.1. Negativity-dominant individuals

Recall that some previous studies reported an enhanced N400 in response to morphological violations. To test for an N400 among our negativity-dominant individuals, we fitted a model with Language, Participle Type and Correctness to their data from the centroparietal ROI in the 300–500-ms time window (Table S14 in the Supplementary Material). This model yielded an effect of Correctness (b = − 1.397, SE = 0.142, t = −9.836, p < 0.001) and no interactions, reflecting more negative-going ERP responses to the two violation types (relative to the correct forms) among the negativity-dominant individuals.

The results of the group-level analyses signaled a LAN for regularizations in L1 German, but not in L2 English. To statistically test whether this also holds for the negativity-dominant individuals, we fitted a model with Correctness (incorrect vs. correct), Language (German vs. English) and Participle Type (regular vs. irregular) to the data from the left-anterior ROI (Table S15 in the Supplementary Material). This model shows a Participle Type by Correctness interaction (b = 2.018, SE = 0.388, t = 5.2, p < 0.01) and – more importantly – a significant three-way interaction of Correctness by Participle Type by Language (b = 3.955, SE = 0.716, t = 5.527, p < 0.001), indicating L1/L2 differences for the two violation and participle types with respect to the LAN. We then examined the two languages separately. For the negativity-dominant individuals’ German L1 data, we fitted a model including Correctness, Participle Type and Hemisphere (left vs. right) as dependent variables to the data from the left and right anterior ROI in the early time window. The model revealed a significant three-way interaction between all dependent variables (b = 9.2624, SE = 0.586, t = 15.802, p < 0.001) as well as an interaction between Correctness and Hemisphere (Table S16 in the Supplementary Material). Separate models for the two violation types revealed a significant effect of Correctness for regularizations (b = −1.768, SE = 0.178, t = −9.923, p < 0.001) and a marginally significant effect for irregularizations; see Tables S17 and S18 in the Supplementary Material. In the L2, on the other hand, the corresponding model (Table S19 in the Supplementary Material) yielded an overall effect of Correctness (b = −0.611, SE = 0.144, t = −4.250, p < 0.001) without any effect or interaction with Participle Type, suggesting no differences between the two participle violations. These results indicate clear differences within the negativity-dominant individuals, a LAN for regularizations in the L1 and a widespread (N400-like) negativity for both types of violations in the L2; see also the ERP plots in Figures S3A–S4B in the Supplementary Material for illustration.

3.2.2. Positivity-dominant individuals

Visual inspection of the plots in Figures S5 and S6 in the Supplementary Material suggests a late positivity (P600) for incorrect as compared to correct participle forms in both L1 German and L2 English. To statistically examine these data, we first fitted a model on the averaged signal from the centroparietal ROI with Participle Type, Correctness and Language as fixed effects in the 500–800 ms time window (Table S20 in the Supplementary Material). We found a significant effect of Correctness (b = 1.874, SE = 0.134, t = 14.037, p < 0.01) as well as an interaction of Correctness and Language (b = 0.831, SE = 0.229, t = 3.635, p < 0.01), due to larger P600 magnitudes for incorrect participles in the L2 than in the L1. We then examined the two languages separately. These models showed a significant effect of Correctness in both languages, with a substantially larger effect in L2 English (b = 2.277, SE = 0.165, t = 13.767, p < 0.01) than in L1 German (b = 1.452, SE = 0.209, t = 6.961, p < 0.01); see Tables S21 and S22 in the Supplementary Material. Overall, these results confirm a late positivity (P600) among the positivity-dominant individuals, which is more prominent in the L2 than in the L1.

Recall, finally, that the group-level analysis yielded a LAN for regularizations in the L1 (German) data in the early (300–500 ms) time window. Examining whether this replicates for the positivity-dominant individuals, two models were fitted to their averaged L1 data from the left-anterior ROI, one for regularizations and one for irregularizations, with Correctness as a fixed effect (Tables S23 and S24 in the Supplementary Material). Significant effects of Correctness were found for regularizations (b = −2.133, SE = 0.375, t = −5.695, p < 0.001) and irregularizations (b = 2.101, SE = 0.32, t = 6.561, p < 0.001). Note the negative coefficient of this model’s estimate for regularizations, which confirms a LAN for this violation type. These findings replicate the results of the group-level analyses for both negativity-dominant and positivity-dominant individuals in the L1.

4. Discussion

The main purposes of the present study were to examine (i) variability in late bilinguals, specifically with respect to the processing of morphologically complex words, as well as (ii) L1/L2 differences in this domain. We used ERPs that provide online measures of neural activity during language processing, testing morphological forms (viz. past participles) that are highly similar in the two languages (viz. English and German). Unlike previous studies of morphological processing in bilinguals that tested different speaker groups for the L1 and the L2 (e.g., Coughlin et al., Reference Coughlin, Fiorentino, Royle and Steinhauer2019; Dowens et al., Reference Dowens, Vergara, Barber and Carreiras2010; Hahne et al., Reference Hahne, Müller and Clahsen2006), our study directly compared the same individuals in their L1 (German) and their L2 (English), thereby precluding any confounding effects of the L1/L2 comparison arising from other differences between the two speaker groups. We analyzed the data in two steps, firstly for the entire participant group, separately for L1 (German) and L2 (English), and secondly with respect to individual differences.

4.1. Results of the group-level analyses

We found a clear L1/L2 contrast, notably within the same individuals, namely an early focal LAN for regularizations in the L1, that is, for overapplications of regular inflection to verbs that require irregular forms, and a late positivity (P600) for both violation types in the L2. The LAN observed for the L1 aligns with previous findings on the overapplication of morphological rules (e.g., Lück et al., Reference Lück, Hahne and Clahsen2006; Penke et al., Reference Penke, Weyerts, Gross, Zander, Münte and Clahsen1997; Weyerts et al., Reference Weyerts, Penke, Dohrn, Clahsen and Münte1997). In these studies, the LAN has been interpreted as reflecting processes involved in handling morpho-syntactic or morphological rule violations (Molinaro et al., Reference Molinaro, Barber and Carreiras2011), such as the incorrect pairing of a verbal stem and a regular -t participle ending (*weggeblast ‘blown away’) tested in the current study. According to dual-route models of morphological processing (e.g., Pinker, Reference Pinker1999; Pinker & Ullman, Reference Pinker and Ullman2002), regular -t participle formation in German follows a rule-based pattern, whereas all irregular participle forms are stored and represented as lexical wholes (e.g., Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Brinkmann, Clahsen, Wiese and Pinker1995). Our group-level finding of a LAN for -t regularizations (but not for irregularizations) is consistent with this distinction, as only regularizations engage a combinatorial rule-like mechanism. Irregularizations, by contrast, are better understood as lexical violations. Given this, we might have expected these violations to elicit an enhanced N400, as seen in prior studies (Hahne et al., Reference Hahne, Müller and Clahsen2006; Lück et al., Reference Lück, Hahne and Clahsen2006; Son, Reference Son2020; Weyerts et al., Reference Weyerts, Penke, Dohrn, Clahsen and Münte1997). However, at the group level, no significant N400 modulation was found for this condition in either the L1 or the L2, which could be due to averaging across different types of individuals, as discussed below.

The L2 group-level results yielded a late positivity (P600) for both regularizations and irregularizations and no LAN for any violation type. That morphological violations may elicit a P600, particularly when these are presented in a sentential context (rather than in a word list), has been found in a number of previous ERP studies (e.g., Ciaccio et al., Reference Ciaccio, Bürki and Clahsen2023; Lück et al., Reference Lück, Hahne and Clahsen2006), including Hahne et al.’s (Reference Hahne, Müller and Clahsen2006) study of participle and plural forms in L2 German speakers. Assuming that a P600 response signals late repair/reanalysis processes during sentence processing (e.g., Regel et al., Reference Regel, Opitz, Müller and Friederici2019), the P600 reported in morphological violation studies suggests that incorrectly inflected forms induce sentence-level violation effects, possibly due to the incorrect form being internally repaired before integrated with the rest of the sentence.

4.2. Results of the individual-differences analyses

We adopted the approach of Tanner and van Hell (Reference Tanner and van Hell2014), which (by using an effect size measure) seeks to determine whether an individual’s ERP response to a violation is negativity-/positivity-dominant in a given time window. We found that some individuals indeed responded to the same morphological violation with a more pronounced negativity in the early time window relative to a weaker positivity in the late time window, whereas others showed the opposite pattern, a more pronounced late positivity relative to a weaker negativity. This finding – confirmed by a negative correlation between these two ERP measures – replicates the types of individual profiles found in previous ERP research on both sentence-level (e.g., Tanner, Reference Tanner2019; Tanner & van Hell, Reference Tanner and van Hell2014; Tanner et al., Reference Tanner, Mclaughlin, Herschensohn and Osterhout2013) and morphological violations (Ciaccio et al., Reference Ciaccio, Bürki and Clahsen2023), possibly indicating different neurocognitive processing mechanisms in dealing with grammatical violations. Crucially, however, an individual’s profile in the L1 was not correlated with his/her profile in the L2, which means that individuals’ profiles (as measured in terms of negativity/positivity-dominance) do not generalize across a native and a non-native language. In particular, we found a focal LAN for bilinguals’ L1 but not their L2, regardless of whether an individual is negativity- or positivity-dominant. This way, language status (L1 vs. L2) limits individual variability: L1/L2 differences in language-related ERPs are stable and consistent across otherwise different individuals. We additionally examined a number of potential predictors to determine an individual’s profile (viz. negativity- vs. positivity-dominant). While working memory scores did not turn out to be reliable, L2 proficiency and L2 semantic fluency were correlated with the magnitudes of the ERP effects such that individuals who were more proficient and more fluent in the L2 showed larger ERP effects than those with lower L2 proficiency and fluency.

Our findings from individuals with negativity-dominant ERP profiles reveal a striking L1/L2 contrast, with a LAN observed for regularizations in the L1 and a broad N400-like negativity for both types of violation in the L2. As for the L1, our results replicate the LAN effect obtained by Ciaccio et al. (Reference Ciaccio, Bürki and Clahsen2023) for -s plural regularizations in L1 German for a different morphological phenomenon, viz. participle formation. Both findings challenge the claim by Tanner and van Hell (Reference Tanner and van Hell2014) and Tanner (Reference Tanner2019) that LANs obtained in group-level analyses are due to averaging across different kinds of individuals. In Tanner and van Hell (Reference Tanner and van Hell2014) and Tanner (Reference Tanner2019), a LAN response was found for morpho-syntactic violations in their group-level analyses, but disappeared when inter-individual variability was taken into account. By contrast, our results (as well as those of Ciaccio et al., Reference Ciaccio, Bürki and Clahsen2023) revealed a stable LAN effect for our participants’ L1, not only in the group-level analysis but also when individual profiles were considered using the same methods as Tanner and colleagues. In their L2, however, participants with a negativity-dominant ERP profile presented with an N400-like response to both types of violation. This effect was not seen in the group-level analysis, possibly due to averaging across negativity- and positivity-dominant individuals. Assuming that lexical (word-level) violations elicit N400 responses (Hagoort & Brown, Reference Hagoort and Brown2000), the results from the negativity-dominant individuals suggest that both kinds of morphological violations are processed as undecomposed lexical violations in the L2. By contrast, the LAN elicited by regularizations signals morphological decomposition of such violations in the L1. Taken together, these findings support dual-route models of morphological processing and align with the hypothesis that L2 processing relies more on whole-word storage of complex words and less on morphological parsing than the L1 system (Clahsen & Felser, Reference Clahsen and Felser2018).

Turning to the results from the individuals with positivity-dominant ERP profiles, we found a late positivity (P600) among these individuals, which was more prominent in the L2 than in the L1. Recall that the group-level analysis did not yield a P600 in the L1, which could again be the result of averaging across participants with different individual profiles. In line with the functional interpretation of the P600 effect (Hagoort et al., Reference Hagoort, Brown and Groothusen1993; Osterhout & Holcomb, Reference Osterhout and Holcomb1992), individuals exhibiting a positivity-dominant response (P600) appear to be primarily attuned to sentence-level revision, rather than word-level lexical/morphological properties of the two violation types. That the P600 is larger in the L2 than in the L1 suggests that revision/repair processes of morphological violations are more resource-demanding in the L2 than in the L1. Furthermore, we found the same LAN effect for both negativity- and positivity-dominant individuals in L1 German, indicating the stability and replicability of the LAN for regularizations in L1 speakers.

5. Conclusion

The present study aimed at extending prior ERP research on individual language processing profiles (e.g., Qi et al., Reference Qi, Beach, Finn, Minas, Goetz, Chan and Gabrieli2017; Tanner, Reference Tanner2019; Tanner & van Hell, Reference Tanner and van Hell2014) by showing how language status (viz. L1 vs. L2) and morphological form (viz. regular vs. irregular inflection) constrain variability in individuals’ brain responses. The core finding of the present study is a striking contrast within the same bilingual speakers between their L1 (German) and their L2 (English) with respect to their brain responses to morphological violations. Taking our participants as one group revealed divergent ERP patterns for the two languages, an early focal LAN for regularizations in the L1 and a P600 for the L2 for both violation types. Additional analyses replicated the types of individual profiles found in previous ERP research for our data, with some individuals showing a negativity-dominant response and another one a positivity-dominant response to the same morphological violations. Crucially, the L1/L2 contrast obtained in the all-participants analyses was confirmed for both the negativity- and the positivity-dominant individuals. In their L1, all participants (beyond inter-individual differences) exhibited a LAN, selectively for regularizations, whereas in their L2, the negativity-dominant individuals showed a (broad N400-like) negativity and the positivity-dominant individuals a P600 for both violation types. These findings indicate that linguistic constraints may limit individual variability in language processing. Specifically, the nature of the morphological violation (viz. regularizations vs. irregularizations) and language status, that is, whether the violation is an individual’s L1 or L2, were found to limit individual variability. Contrasting ERP responses for regularizations and irregularizations were obtained for our participants in their L1, indicating neural differences between (rule-based) regular versus (lexically-based) irregular inflection as posited by dual-mechanism morphology (e.g., Clahsen, Reference Clahsen and Wunderlich2006; Pinker & Ullman, Reference Pinker and Ullman2002). Accordingly, the LAN elicited by regularizations such as (*gelad-et ‘load-ed’) in L1 German suggests that such forms are processed as word-internal combinatorial violations, that is, as incorrect pairings of a stem and a segmented regular ending. By contrast, the L2 data did not reveal any regularization-specific ERP responses. Instead, both types of violation elicited either N400-like responses (for negativity-dominant individuals) or a P600 (for positivity-dominant individuals). While the former may signify a lexical violation effect and the latter late sentence-level repair or reanalysis, an ERP signature of word-internal combinatorial processing was only found in the L1 but not in the (same individuals’) L2 data. These findings align well with the view that the L1 and the L2 engage different processing mechanisms (Clahsen & Felser, Reference Clahsen and Felser2006, Reference Clahsen and Felser2018).

Finally, we note that grand mean average ERPs may obscure patterns that are present in smaller participant groups and that additional analyses of the individuals’ ERP profiles may reveal a more nuanced picture. We found this to be the case for the N400 (among negativity-dominant L2 individuals) and for the P600 (among positivity-dominant L1 individuals), none of which became significant in the corresponding group-level analyses. Thus, including analyses of individual differences can lead to a more comprehensive view of ERP datasets.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728926100972.

Data availability statement

All materials related to this study, including experimental items, data and code for the statistical analyses, are available at the repository: https://osf.io/puaky/?view_only=898ca9ab3ee7479682a5b784ba03ecff.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sabia Costantini for her contributions to data collection, construction of experimental materials, experiment setup and data analysis; Friederike Schubert and Marian Jenke for their help with the construction of experimental materials; and Maximilian Krupop and Angelina Lorenz for their help with data collection. We are also grateful to Laura Ciaccio for supporting the experimental setup and commenting on an earlier version of this manuscript and to Claudia Felser for helpful and inspiring input and discussion along the whole project.

Funding statement

This work has been partly funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Project ID 317633480–13 SFB 1287, Project B04 (PIs Clahsen/Felser).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.