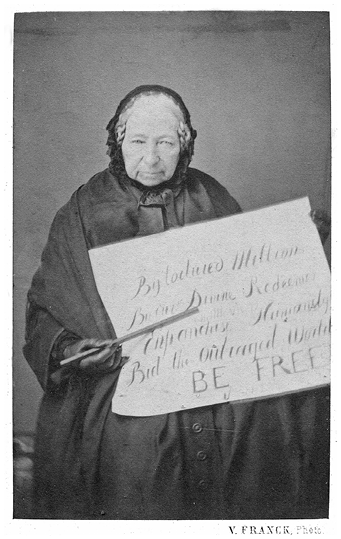

Two known portraits of Chelmsford Quaker Anne Knight mark her evolution from an assiduous but reclusive supporter of the slave’s cause to the swashbuckling suffragist, one of Europe’s first, which she later became. The first, a composite group portrait of the World Anti-Slavery Congress in 1840 by Benjamin Haydon, shows her in profile, blending into a bonneted cohort sitting on the fringes of this seminal gathering. The second is a carte de visite which she sat for in 1855, in the studio of Victor Franck in a small village in eastern France, where she finally settled. Knight’s portrait shows her in her late sixties, clad in the black plain dress customary of Quakers. Other prominent female reformers like Priscilla Bright McLaren, Maria Weston Chapman, or even Harriet Martineau, had themselves portrayed reading or sewing. Knight, however, looks directly into the camera and focuses attention on the placard on her lap (Figure 3.1). She motions as if she is helping the viewer recite her catechism, which reads: ‘By tortured millions / By our Divine Redeemer / Enfranchise Humanity / Bid the Outraged World BE FREE.’Footnote 1

Figure 3.1 Anne Knight in 1855: ‘By tortured millions / by the Divine Redeemer / Enfranchise Humanity / Bid the Outraged World / BE FREE’.

This placard was a distillation of decades of work formulating and publicising historical connections between struggles against different forms of oppression, often in formulaic forms of Knight’s own devising (Chen Reference Chen2023). She afforded the campaign against slavery, and particularly the Garrisonian outlook on abolition, pride of place in her ‘pantheon’ of feminist prehistory (Grever Reference Grever1997). This chapter traces how she worked with an equally outspoken francophone colleague, Jeanne Deroin, to promote a specific conception of what the struggle against slavery, and especially the event of French abolition in 1848, meant for women. Together, they came to demand publicly ‘the complete abolition of all privileges of sex, race, birth, caste and fortune’ (À nos abonnés’ 1849, 1), broadcasting ideas of ‘universal emancipation’ that were closer to American Garrisonianism than to the French Republicanism which they at first welcomed.Footnote 2 A striking case of ‘information politics’, Deroin’s circle used the periodical press, correspondence networks, and public performance to assemble and internationally disseminate an archive of stories and materials from the antislavery campaign, both during the heady days of 1848 and the years of disillusionment that followed (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998).

Jeanne Deroin’s dogged efforts to maintain a periodical publishing venture were indispensable to this work. The titles she published, L’Opinion des femmes and particularly the Almanach des femmes, were more than just a record of her and her colleagues’ viewpoints. In the words of Isabel Hofmeyr, their pages served as ‘intellectual archives’ which invited readers to ‘habituat[e] […] to geographies, old and new’ (Hofmeyr Reference Hofmeyr2013, 91, 107). They also facilitated new infrastructures through the strenuous collaborative process of their creation and circulation (Hauch Reference Hauch and Körner2000, 654; Ferguson Reference Ferguson2014). The widespread practice of ‘writing with scissors’, by which editors recycled and rearranged older texts into new configurations, made periodicals into complex cumulative archives not just of individual texts and data, but also of traces of, and cues about, their previous travels and significance (Ellen Garvey quoted in Hofmeyr and Peterson 2018, 10). What is more, as readers knew, these configurations were not the endpoint of texts – as these could in turn be taken up by others for further circulation.

This chapter will follow the thread of Knight and Deroin’s work through the eventful middle decades of the nineteenth century. Foregrounding Knight and Deroin’s activities and considering their writings in conjunction, it shines a light on one particular pathway for memories of antislavery, but also more generally on the memory work women’s rights circles performed in this period. Knight and Deroin promoted their views of the movement and its history among a variety of groupings, including Chartists, London socialists, Quakers, Republicans and Fourierists in Paris, and the Worcester National Women’s Rights Convention in Massachusetts. Their activities and investments show how, as the fledgling women’s movement moved into repressive and uncertain times, vigorous voices were as concerned with the nature of their initiative, its historical lineage, and the contents of its usable past, as they were with concrete political demands.

Knight and Deroin’s work is also a powerful example of the internationalism in the very fibres of these early initiatives. During this period, circles of women’s rights advocates were intimately connected. Local initiatives kept close eye on each other and correspondents like Anne Knight and Maria Chapman, who were both living in Paris at the time of the upheavals of 1848, served as links between communities. For example, Louise Otto reported on Deroin in her newspaper Frauenzeitung, as did Maria Chapman in Liberty Bell, and Sarah Grimké published a letter to Deroin, praising her almanacs, in The Lily in 1856 (Anderson Reference Anderson1998, 3; Lerner Reference Lerner1998, 116–119; Chambers Reference Chambers2014, 170–171). Conversely, the Almanach featured writings of Margaret Fuller and Anna Blackwell and celebrated the achievements of Harriet Taylor Mill and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Direct and indirect collaborations for the cause were textured not just by proclaimed universals, such as religion and the experience and duties of maternity (Offen, Reference Offen2000, 114; Delvallez and Primi Reference Delvallez and Primi2004), but also by different cosmopolitanisms, including the prophetic encompassing visions of the Saint-Simonians and the bold, border-defying agitation of Garrisonianism (Pilbeam Reference Pilbeam2013; Cole Reference Cole2018). These various physical and imaginative connections have led several scholars to suggest that the wave of women’s rights agitation that welled up in 1848 was in fact a transnational movement, which negotiated a shared ‘language of feminist demands’ (Offen Reference Offen2000, 112; Anderson Reference Anderson1998; 2000; McFadden Reference McFadden1999; Delvallez and Primi Reference Delvallez and Primi2004; Primi Reference Primi2005; Tamboukou Reference Tamboukou2016).

The memories of antislavery Knight and Deroin channelled were accented differently than the fiction of the previous chapter. The earlier works focused on the denigration of women particularly within marriage, and on how this produced certain social ills and gave centre stage to motifs of the sensibility and natural feelings of sisterhood among women and the socially transformative potential of feminine appeals to empathy. By contrast, for Knight and Deroin antislavery was initially a model for political claims-making, as they advocated for a range of rights, from free association to suffrage. During their political exile, the history of abolition came to serve as inspiration for an attitude of steadfast moral absolutism, which they especially associated with Garrisonian abolitionists.

The socialist mother of three, Deroin, and the veteran abolitionist, Knight, started to work together in Paris, in 1848. The formation of their ideas, however, began in the 1830s, when each was trying to get across their vision in relative isolation, in Paris and Chelmsford respectively. This analysis follows their work through different media and in shifting political auspices, from Knight’s international correspondence in the 1830s, through their collaboration on periodicals and letters in the years following 1848, and finally to Deroin’s speech before a socialist assembly in London in 1857. Rather than their failure to achieve concrete political goals, which led contemporary allies to dismiss them as ‘cracked’ and as ‘très impolitique’, this account centres on their success in fostering a transnational memory of antislavery and of Garrisonian radicalism (Stern Reference Stern1862, 36; Anderson Reference Anderson2000, 175). The significance and originality of their efforts becomes clear when these efforts are contrasted with contemporary Parisian intellectual responses to events in 1848, with which they were at odds at several levels. These included the efforts of prominent women’s right advocate Eugénie Niboyet to bring women into the French public sphere, the nationally oriented commemorations of abolition by the French Republican government, and the discussions of abolitionism by the Fourierists.

Biographical Note

Anne Knight and Jeanne Deroin came from different backgrounds but found common ground in their striking outspokenness on the issue of women’s political rights. Knight was twenty years Deroin’s senior, born to an affluent Quaker family that was active in several reform movements, including antislavery. Never married, she devoted her life to her activism against slavery and for women’s rights. She was a zealous organiser, formative in the founding of several societies and, with the London Female Anti-Slavery Society, organised the movement’s largest national women’s petition against slavery (187,157 signatures, Midgley Reference Midgley2004, 58). In 1834, at age fifty, she embarked on a tour of France to collect evidence against slavery, consolidate the network, and occasionally to lecture. This French connection would remain important to her. She took a close interest in French political developments and travelled back and forth between France and the UK between 1834 and 1848. She spent the final years of her life in Waldersbach, near Strasbourg, before she died in 1862.

Knight was an immediatist abolitionist and one among a small number of British women who formed a concrete link between the antislavery campaign and women’s rights agitation, including Elizabeth Pease Nichol, Harriet Martineau, Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, Josephine Butler, and Marion Kirkland Reid (Sklar Reference Sklar, Yellin and Van Horne1994, 304; Midgley Reference Midgley2004). From 1840 onwards, when she met Central American feminist-abolitionists like Lucretia Mott at the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London and experienced first-hand the row over women’s exclusion from the event, she began to agitate for women’s rights in her personal correspondence. She admired Garrison’s uncompromising agitational style, expansive view of social injustice, and cosmopolitan orientation, and she began to make a similarly uncompromising argument that women’s exclusion from politics was the cause of global historical injustices. In a letter to Garrison, she described ‘the monopoly holding all power in the hands of the men’ as the ‘root of the tree’ of all iniquities (Knight, Letter [14 Oct. 1845]).

In her sixties, influenced by her experiences with Parisian women’s rights circles, she became emboldened to take her advocacy public. She became closely involved in the founding of the Sheffield Female Political Association and the Woman’s Elevation League (Schwarzkopf Reference Schwarzkopf1991, 248–254), had several of her letters of complaint to notable figures printed, and even partook in ludic actions. Her language and actions became increasingly radical and she frequently employed the lexicon of physical combat. In her letter to Robert Bartlett, she called herself ‘as true a KNIGHT as ever wore spurs, or brandished a sword in Christendom!’ and described in some detail her public action of demanding in a crowded Council Room to be married to the state (‘Letter to Robert Bartlett’ 1852), a facetious reference to increased political representation.

British suffragists would later come to commemorate Knight as the author of the first pamphlet for female suffrage (‘A Woman’s’ 1884; Blackburn Reference Blackburn1902, 19). In her own time, however, her stridency left her alienated. Knight was frequently exasperated by the reticence and family obligations of her colleagues, while in turn, her tactics and outspokenness frustrated family and friends.Footnote 3 In the 1840s, Knight began to include in her regular correspondence materials on women’s rights and other causes, which she painstakingly collected. She circulated these materials not just as pamphlets, but also had short excerpts printed on coloured labels, which she attached to her letters. Her relations tried to discourage her from doing so and scolded her particularly for a letter she sent to Maria Chapman in 1840.Footnote 4 The letter had been read at the annual meeting of the Boston Female (Antislavery) Society and subsequently printed in the annual report of the Glasgow Emancipation Society. In it, she called women men’s ‘better and wiser half – the being whose clearer and diviner instinct would enlighten, ennoble, and sanctify his counsels and hasten, with the help of divine providence, the renovation of our world’ (‘Appendix’ 1840, 48). Her cousin was infuriated by this ‘arrogant piece of bombast’ and worried for the reputation of both their family name and the cause (Allen, Letter [19 Mar. 1841]). Lucretia Mott, a liberal Hicksite Quaker, regretted that Knight was a ‘bigot’ when it came to denominational, and doubtless, tactical differences of opinion (Mott Reference Mott2002 [1842], 109). Her tone also put off younger generations of women’s rights advocates. When she contacted Barbara Leigh Smith and Bessie Rayner Parkes in 1850, they dismissed her as ‘cracked’ (Anderson Reference Anderson2000, 175). Knight’s stridency found a warmer welcome in Paris, where romantic socialism had paved the way for grander turns of phrase and more dramatic action.

Born to a working-class family in Paris in 1805, Deroin was a seamstress and eventually with much difficulty obtained a licence to work as a schoolteacher in the 1840s (Riot-Sarcey Reference Riot-Sarcey1994; Tamboukou Reference Tamboukou2016, 15). Jeanne Deroin first became actively involved with agitation for women’s rights in the early 1830s. In the ‘profession de foi’ which she submitted to the Saint-Simonian journal Le Globe, she already associated women’s societal position with slavery.Footnote 5 In an image reminiscent of Sand’s Indiana, she graphically likened the custom of women taking their husbands’ surnames to ‘the burning iron which imprints upon the slave’s face the initials of the master’ (Deroin [1831] quoted in Riot-Sarcey Reference Riot-Sarcey1992, 134).Footnote 6 Looking back at the revolution of 1830, she further argued that women’s slavery was an obstacle to historical progress, an idea which she and Knight would come to emphasise again in 1848:

Great political events have followed each other, revolutions have shaken Europe, calls of glory and of triumph have reverberated throughout the universe, liberty and equality have been proclaimed for all. And woman is still the slave of man, and the proletarians are still under the yoke of destitution and ignorance.

Only when emancipated could woman become ‘the angel of peace and reconciliation whose sweet and powerful influence will connect all members of the family in a perfect understanding in a sacred harmony’ (quoted in Riot-Sarcey Reference Riot-Sarcey1992, 139).Footnote 8 Notably, Deroin’s letter also liberally criticised elements of the Saint-Simonian doctrine (Riot-Sarcey Reference Riot-Sarcey1994, ch. 3, esp. fn. 319; Rancière Reference Rancière2012, 176ff.).

Despite her early objections to women’s subjection in marriage (‘Profession’ 1992 [1831]), she eventually married a fellow Saint-Simonian and raised three children, one of whom needed special care (Serrière Reference Serrière1981, 41). Her busy personal life made her activist record intermittent (Tamboukou Reference Tamboukou2016, 15). She was likely anonymously involved with the Tribune des femmes in 1832–1834 and again became vocal in the aftermath of the revolution of 1848, when her agitational, organisational, and editorial activities, particularly her self-proclaimed candidacy for the election of 1849, made her one of the most well-known and targeted women’s rights advocates in Paris.Footnote 9 Soon after her release from a six-month political prison sentence at Saint-Lazare in June 1851, she left for London, where, with her daughter Cécile Desroches, she struggled to make ends meet. Though she receded from visibility, she was involved with several socialist initiatives, and part of William Morris’ orbit (Ranvier Reference Ranvier1908; Baker 1997; Kunka Reference Kunka2014; 2016). She took up correspondence with French liberal feminists again in the 1870s (Dzeh-Djen Reference Dzeh-Djen1934, 53–54; Kunka Reference Kunka2016).

Knight and Deroin began to work together in 1848, when they were both members of the small collectives Comité des droits de la femme and the Société de la voix des femmes.Footnote 10 Theirs were among the handful of signatures on a few petitions on women’s concerns to the provisional government in the spring of 1848 (Riot-Sarcey Reference Riot-Sarcey1994; Tamboukou Reference Tamboukou2016, 167). Knight soon came to act as the greatest defender of Deroin’s controversial tactics. She brought home with her, and carefully preserved, one of the posters Deroin produced for her electoral campaign (1849) and publicised Deroin’s exploits in several of her letters to French and English dignitaries. For instance, she cited part of one of Deroin’s electoral speeches in her letter to Lord Brougham (1849), referring to her as a ‘magnificent creature! […] greater than Brutus, than Boadicea, Joan of Arc, than the Maid of Zaragossa’, and reminded the Sheffield Female Political Association in 1851 to ‘Encourage and strengthen each other, dear sisters, for prison doors are not closing upon you as on our noble Jeanne Deroin and her companion [Pauline Roland]’ (‘The Rights’ 1851; Drinkal 2018). Knight brought Deroin into contact with feminists in Europe and America, including the Sheffield Female Political Association and the Worcester Convention of 1851 (‘Female Political’ 1851, 3). Deroin in turn promoted Knight’s ideas among Parisian women’s rights circles (‘Visites’ 1851; ‘To the editor’, 1853; ‘Lettre d’Anne’ 1854) and counted on Knight’s help when she moved to London (Baker 1997; Pilbeam Reference Pilbeam and Freitag2003; Tamboukou Reference Tamboukou2016, 165).

Knight’s Garrisonian inspiration and Deroin’s Saint-Simonian background contributed to their shared conviction that women had complementary qualities to men and that therefore without her voice political representation was incomplete and ultimately unable to act for the public good. The printed correspondence in the Almanach for 1854, which details their disagreement over the ultimate purpose of female suffrage as a means or an end, indicates a high level of sophistication in their strategizing (‘Lettre d’Anne’ 1854). Besides their intellectual influence on one another, they were important brokers for each other’s work and were indispensable to one another’s efforts to seed an alternative framing of 1848.

Knight’s Garrisonianism

While Deroin spent the early 1830s formulating her ideas among a core group of Parisian women’s rights advocates, such as Suzanne Voilquin and Désirée Véret Gay, and gaining experience in periodical publishing, Anne Knight supported the British antislavery movement. From the 1820s onwards, Knight’s correspondence reflects her admiration for women who dared to engage in public antislavery advocacy and her interest in broadening the sphere of women’s public engagement grew concomitantly with her antislavery work. As was customary for women in the abolition movement, she was part of the supporting forces, fulfilling tasks such as petitioning and sewing for bazaars (Knight ‘Appendix’ 1840, 48; Knight ‘To Richard’ 1850, n.p.). She did not make public appearances for the cause in the UK, but made efforts to publicise the advocacy of other women such as Elizabeth Heyrick.Footnote 11 Her lecture tour in France in 1834, made by necessity as more prominent members were not available to join her (Stephen, Letter [14 Nov. 1834]), acquainted her with public performance and she soon after encountered the ideas of the Saint-Simonians.Footnote 12

In the late 1830s, Knight began building a transnational network of feminist-minded reformers from within the ranks of antislavery and the Chartists (Crawford Reference Crawford2003, 631). In 1838, she asked William Lloyd Garrison to forward a letter to Margaretta Forten, a female African American abolitionist (Knight, Letter [14 March 1838]) and also requested information on other ‘brave Amazons in [his] ranks’ in America (Knight, Letter [14 March 1838]), a request similar to the one she had made George Stephen in 1834 (Stephen, Letter [14 Nov. 1834]). Moreover, she wrote to romantic socialist Catherine Barmby after reading her ‘Demand for the Emancipation of Woman, Politically and Socially’ (1843), starting a dialogue that was eventually printed in the pages of radical papers like Holyoake’s Reasoner and the White Quaker publication Some Account of the Truth (Knight, ‘Catherine’ 1844).

Knight asked colleagues internationally to expand on their ideas and to send her further promotional materials regarding slavery and women’s position. Strikingly, she also enquired after their strategy. In her 1838 letter, she interrogated William Lloyd Garrison about his aggressive rhetorical style, rumoured to be ‘declamatory violence which tended to repel & aggravate rather than persuade’ (Knight, Letter [14 Mar. 1838]). She wished to know ‘what success is given to [his] arms’ (Knight, Letter [14 Mar. 1838]). Knight was particularly interested in the firebrand rhetoric and activities of Wendell Phillips and Garrison, an interest fostered both through correspondence and the reading of American abolitionist publications (Stephen, Letter [14 Nov. 1834]).

The year 1840 proved a pivot in Knight’s activities from antislavery to women’s rights. According to Lucretia Mott, Anne Knight did ‘all she could’ to organise a women’s meeting at the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention of 1840 (Letter [1840] 2002, 79; see also Sklar Reference Sklar, Yellin and Van Horne1994). Knight’s engagement with American antislavery women, as well as her witnessing of Phillips’ defence of women’s political engagement and Garrison’s refusal to participate in the proceedings while women were excluded, further cemented Knight’s identification with the Garrisonian vision of ‘universal emancipation’ (Hogan Reference Hogan2008, 67). After the events of 1840, Knight began moreover to claim that women’s work in antislavery legitimated their claims for political representation (Malmgreen Reference Malmgreen1982).

She also began to air personal exasperation and a sense of injustice at the lack of recognition for women’s efforts in the antislavery movement. She shared these frustrations with other female abolitionists; Maria Chapman had described the midnight toiling and sacrifices made by women for the abolitionist cause ([1843], quoted in Taylor Reference Taylor and Lemire2009, 121) and her sister Lucia Weston recorded that her ‘fingers [were] nearly sewed off’ in preparation for a bazaar (quoted in Gardner Reference Gardner2016, 48; see also Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey1998). In 1840, Knight wrote to Chapman:

we tell them we are not the same beings as fifty years ago no longer ‘sit by the fire & spin’ or distil rosemary & lavender for poor neighbours – appoint committees for them to visit in sickness, old age, maternity, missions [?] Bibles [sic] reporting to the men sitting in their public meetings uniting with them in association committees, then comes our great & mortal conflict; the dreadful monster slavery must be grappled with & who is sent out to do it? not man not the stronger vessel with his nervous & brawny arm & great calibre of his stentorian voice the fierce threatening of his black beard & mustachios & his eye like Mars to threaten and command – not the sons of Mars the sons of thunder Boanergean not them? who then? some fierce dragon more horrible still? no! guess again? Cerberus? no weak slender untrained-for-the-work modest tender woman! & when she appeals to the men against such unheard-of folly & atrocity to the weaker vessel [English abolitionist] James Cropper has said it is no use talking […].

Similar frustrations speak from a later letter to Richard Cobden, in which she spoke of the ‘underground toils’ of women’s philanthropy, riffing on the well-known ‘Song of the Shirt’ (1843) to describe the work of sewing circles: ‘health and mind equally suffer in the ‘stitch, stitch, stitch, till the stars shine through the roof, and sew them on in a dream, & oh, it’s to be a slave’, ever toiling, never to see a Right!’ (Knight ‘To Richard Cobden’, 1850).

In uttering these frustrations, Knight recalled and dramatised the unseen labour of female workers within the movement, which she meaningfully connected both to the cause of antislavery and the nascent cause of women’s rights.Footnote 13 Her concern regarding Benjamin Haydon’s portrait of the 1840 Convention also speaks to the importance she attached the public commemoration of women’s role in antislavery. She advised Lucy Townsend, who had been at the event:

I am very anxious that the historical picture now in the hand of Haydon should not be performed without the chief lady [Townsend] of the history being there in justice to history and posterity the person who established [women’s antislavery groups]. You have as much right to be there as Thomas Clarkson himself, nay perhaps more, his achievement was in the slave trade; thine was slavery itself the pervading movement.

Perhaps Knight already understood women’s role in abolitionism as part of an as yet unwritten history of a women’s movement, a connection which she would continue to promote throughout the 1840s and 1850s. In her letter to Robert Bartlett, she not only maximised women’s importance to antislavery, but also mobilised it as an argument for universal suffrage. Enfranchisement, she suggested, would

be a happy day for the many millions of our nation; & for our world, as many millions as there were thousands of black slaves in the empire; whose chain the Women of our land were the sturdiest toilers to break. Yes! eight hundred millions of our world all awaiting the day of our espousals [enfranchisement]!

In Knight’s rhetoric, commemoration of women’s importance to antislavery and the rhetorical equation of suffrage with abolition went hand in hand.

Knight educated herself on women’s history globally, on different arguments for women’s emancipation, as well as on effective modes of persuasion. Her active study is evidenced throughout her archives and particularly in her political notebook (‘Notebook’, c. 1838–1862), in which she recorded her engagement with literature on the woman question in the 1840s. She copied articles from La Tribune des Femmes, from writings by Claire Démar and Flora Tristan, and from books on women’s history, such as M. de Thorillon’s Idées sur les lois criminelles (1788), a French edition of William Alexander’s History of Women for the Earliest Antiquity to the Modern Time (1782), and the collected La femme jugée par les grands écrivains des deux sexes (1847), compiled by Louis-Nicolas Bescherelle and Louis-Julien Larcher. She also attended Ernest Legouvé’s influential lectures on L’histoire morale des femmes in Paris 1848 (Knight, ‘Woman’, 1850).

One is struck by the cosmopolitan interests that speak from her studies and practices of collection.Footnote 14 Despite being a devout Quaker, unlike many of her contemporaries she did not preclude the possibility of non-Christian cultures having more equitable gender relations, and she expressed anti-imperialist sentiments. One of her printed labels, ‘Missionary Contrast’, stages a sarcastic contrast between imperial self-conception and the British presence as seen through the eyes of the Chinese, by printing two contrasting reports:

God has raised our country to an eminence unparalleled in ancient or modern times. ‘The Mahommedans respect; the Natives of India obey; the Millions of China have been taught to fear.’ Church Missionary Report 1840 – ‘They [Chinese] have deeply deplored that spirit of commercial cupidity, which, by men professing Christianity, and in defiance of the imperial laws, has become the occasion of poverty and disease […].’ London Missionary Society’s Report, 1840.

From her readings in English and French, she recorded sections on foreign or ancient egalitarian customs of, for instance, Hindus or ancient Gauls (‘Notebook’, n.p.). She publicised these facts in her letters and pamphlets (e.g., Knight ‘Appendix’ 1840; ‘To Athanius’ 1850). In a letter to Chapman in 1840, she elaborately drew on this collected historical knowledge:

Tacitus relates that the Germans always called the women to their war-counsels, because they had something divine in them; and do not your Indians have their conferences unitedly? […] surely, if Indian women, if German women, if the women of France may hold colloquy with men, the women of England, not less Christian, and no less qualified than they, must, ere long what is dark illumine.

Knight’s work resulted in a rich archive of materials which destabilised the idea of Western superior civilisation, as well as the notion of a natural order to gender relations. Her references indicate a cosmopolitan, Garrisonian understanding of oppression and emancipation.

Knight’s correspondence also provides a glimpse into her unorthodox interpersonal agitation. She records an attempt to present ‘that great wordy freedom’s man’ Félicité Lamennais with an appendix to his book on popular suffrage (De l’esclavage moderne, 1839; Knight ‘Catherine’ 1844). Written by his radical British translator James W. Linton, the appendix considered the issue of women’s suffrage. To Knight’s frustration, Lamennais merely laughed it off. Two of Knight’s copies of Linton’s ‘Appendix’ survive in her copy of Marion Reid’s A Plea for Woman, with some blasphemous lines carefully blacked out. She had multiple copies of this pamphlet to hand out to significant persons, or to include in her correspondence.Footnote 15 A family member later recalled that she tended to carry ‘a large black silk bag or pocket, suspended from her belt, in which she kept many papers, which she took out when she needed them in conversation’ (Charlotte Sturge quoted in Chen Reference Chen2023).

During the 1840s, Knight repeatedly asked prominent figures like Richard Cobden, Garrison, and Chapman to speak out on the issue of women’s rights,Footnote 16 and she sought to convert prominent reformers on the issue by sending packets of women’s rights pamphlets to those she suspected might be supportive of her cause, such as George Jacob Holyoake and Mrs Ashurst Biggs in 1847 (Blackburn Reference Blackburn1902, 19) and Anne Taylor Gilbert in 1849 (Anderson Reference Anderson2000, 29). She recommended and forwarded materials to American feminists as well and asked them to return the favour, calling on them to follow her example as ‘these things [writings on the woman question] ought to be sent darting off like lightning to all the world if possible’ (1847, quoted in Anderson Reference Anderson2000, 13).

In directing her efforts this way, Knight single-handedly emulated the propaganda model of the antislavery movement, with its reliance on moral suasion though massive cultural production. To achieve this, she often cannibalised her own materials, similar to the ceaseless adaptation of iconic images, poetic lines, and stories within the antislavery movement. One example of this is a fragment she composed and circulated as a coloured label in the 1840s (Figure 3.2).

This text is a rich example of Knight’s memory work. In it, she condenses different registers and historical events into a single saying, measuring only little over an inch of eye-catching coloured paper.Footnote 17 Placing her campaign in this historical context, she framed the cause of women’s rights as worthy, inevitable, and, ultimately, as part of the divine plan. Knight pasted this text as a blue label on a letter to a friend in 1845 (Letter to Mary Clutton [12 Mar. 1845]), elaborated on it in her open letter to Robert Bartlett in 1852, and finally had herself photographed with it for her carte de visite.

Another striking result of Knight’s studies was her French epigram Ce qui est, which she began to send around in the early 1840s (Anderson Reference Anderson1998, 2):

That Which Is

Young women of the Gauls had the right to make laws, they were legislators.

African women have, in some tribes, the right to vote.

Anglo-Saxon women participated, in England, in the legislature.

Women of the Hurons, one of the strongest tribes in North America, formed a council, and the elders followed their advice.

See, in antiquity and with people who have been barely civilised, women enjoyed rights which modern peoples refuse them, in the countries where Christianity reigns, where universal brotherhood is proclaimed, without distinction of sex.

We fight for liberty!Footnote 18

As the simple declarative title indicates, the suggestion that there had been alternative, equitable ways of organising society in other cultures, and their contrast with the subjection of women closer to home, seemed to Knight to have a powerful mobilising force.

Knight avidly circulated materials which drew comparisons between women and the enslaved. She circulated Linton’s ‘Appendix’ with her own added emphases in black ink next to several of the more vigorous woman–slave comparisons, such as Linton’s claim that ‘ancient slavery subsists’ (Linton Reference Linton1840, 29). In one of the copies, she illuminated Linton’s question whether ‘Some men [aren’t], even, inferior to some women?’ with her remark ‘Ah, many!’ (Knight [Annotated] 1843). She also had excerpts of American reformer Samuel J. May’s sermon, ‘The Rights and Conditions of Women’ (1845), printed as a pamphlet, ending for emphasis with this comment:

Can those men feel any proper respect for females, who make them their drudges from morning to night, – or who are willing to pay them the miserable pittances which they do, for labours which consume the live-long day, and oft the sleepless night? Yes, about as much as the slaveholders feel for their slaves.

Knight’s accumulation and circulation of materials that invited comparison between women and the enslaved encouraged a transnational framework of comparison, which had deeper implications than woman–slave analogies in passing remarks and popular aphorisms such as P. B. Shelley’s ‘Can man be free, if woman be a slave?’ (1817, canto 2). This well-known line from the Revolt of Islam served as the motto for Reid’s Plea, and Knight vigorously commented next to it: ‘No! Emancipate her then!’ ([Annotated] 1843, n.p.). Knight invited readers to identify women’s subjection not in the vague terms of the slavery of Antiquity, but in the concrete terms of plantation slavery, and to recognise those frames and methods of abolitionism that might serve their aims.

In the first edition of his Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison famously declared:

I will be harsh as truth, and uncompromising as justice. On this subject, I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. No! no! Tell a man whose house is on fire to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen; – but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. I am in earnest – I will not equivocate – I will not excuse – I will not retreat a single inch – AND I WILL BE HEARD.

Following the Garrisonian example, Knight styled herself as an uncompromising, anti-institutional truth-teller.Footnote 19 Peppered with fiery denunciations and passionate capitalisation, Garrisonian rhetoric had powerful affective potential. Channelling this register, additionally, projected the memory of immediatism into the question of women’s rights. By writing in this manner, as will become even more pronounced in the following sections, Knight bestowed on women’s rights the same urgency and moral implications which slavery had.

Besides strident rhetoric, Knight adopted several key Garrisonian tenets in her advocacy, such as faith in moral suasion, a deep-seated cosmopolitan orientation, and a rejection of gradualism. In her letter to Garrison in 1838, she affirmed his non-compromising maxims in his own register, calling slavery ‘this bosom-sin this intestinal guilt’ and warning Garrison not to compromise, as she regretted her compatriots had: ‘Know what you are doing suffer no apprenticeship no quarter with the foe, never allow the words “safe & satisfactory”, beware of Jesuitism; beware of Hill Coolies; a new species of slavery.’ Knight’s conviction often translated into battle metaphors. In a later letter, Knight asked Garrison how his ‘warring’ went and whether he was directing his ‘battering rams’ effectively ([1845]). In her letter to Catherine Barmby (Reference Barmby1843), Knight used a similar register to profess her belief in the need for Garrisonian-style female defenders: ‘[we need] a few Lady Macbeths […] with a holy seraphic ardour in the strength of “God of might” hacking & hewing right and left with their minds’ best weapons’. In her letter to Robert Bartlett, Knight made her belief in moral suasion explicit in those terms, referring to the ‘sword of justice and moral suasion’ (1852, n.p.).

On 23 March 1848, Knight published ‘Ce qui est’, as well as two of her other labels with quotes from Jeremy Bentham and Talleyrand on women’s exclusion from government, in the newly founded Parisian periodical La Voix des femmes (‘Ce qui’ 1848). Profiling herself as an example of the connection between antislavery and women’s rights claims, she began to introduce memories of antislavery in Parisian women’s rights circles. Her collaboration with Jeanne Deroin in the club culture of Paris, which flourished immediately after the February Revolution of 1848, was crucial to this venture.

French Abolition and Its Republican Commemorations

In the spring of 1848, Republican, nationalist, and democratic agitation was brought to boiling point as a wave of revolutions shook the monarchies of Europe. Revolution broke out Paris in February and insurrectionary activities spread across much of Europe. In Paris, Vienna, and Berlin, revolutionary forces made up of Republicans, nationalists, and socialists demanded democratic reforms, with varying success. In France, the Second Republic and universal manhood suffrage were established. In many contexts, liberalised press laws invited an avalanche of new publications (Sperber Reference Sperber2005, 160–161; Clark Reference Clark2012, 191 ff.); in Paris alone hundreds of new periodical publications appeared in just the few weeks following the liberalisations, allowing working-class readerships to become politically engaged in new ways (Ambroise-Rendu 1999, 35; Bouchet et al. Reference Bouchet2015, ch. 1; Hayat Reference Hayat, Moggach and Jones2018, 128–129). Many of these new titles were ephemeral, however, and even better established newspapers were threatened in the European-wide conservative reaction to the revolutionary fervour.

Amid these developments, long-term abolitionists who had risen to prominence within the French Republican provisional government quickly pronounced the immediate abolition of slavery in the French colonies on 4 March and universal manhood suffrage the day after. Like ‘a bolt of living thunder’, the news of this development travelled through the transatlantic correspondence and print periodical networks of antislavery reformers (Frederick Douglass quoted in Hewitt Reference Hewitt, Sklar and Stewart2007, 272; McDaniel Reference McDaniel2013, 185 ff.). French abolition, ostensibly immediate and presented as an expression of the popular will, came much closer to the ideal that reformers had in mind than the British gradual scheme of 1833, Swedish abolition in 1847, or Danish abolition in 1848. For the brief period that the liberal hopes of 1848 lasted, Garrisonians and Republicans alike hailed French abolition as a powerful auspice of the progress of democratic and egalitarian principles (Anderson Reference Anderson1998, 5–6; Hewitt Reference Hewitt, Sklar and Stewart2007; McDaniel Reference McDaniel2013, 185 ff.; Dal Lago Reference Lago2015, ch. 5; Sinha Reference Sinha2016, 363 ff.).

Though the thorny question of abolition had been a recurrent issue in French parliamentary debates, besides specific reform circles discussed in the previous chapter, French audiences had paid little attention for the plight of the enslaved in the colonies or for organised antislavery (Brion Davis Reference Davis1984; Drescher Reference Drescher1991; 2007; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2000). Abolition had not been part of popular revolutionary demands and other reforms more directly relevant to ordinary life occupied the attention of the Parisian public in 1848. This was reflected by how little attention mainstream French newspapers paid to the development.Footnote 20 In contrast to the UK, abolition was not broadly experienced as a matter of collective interest or pride. Key abolitionist figurehead Victor Schoelcher’s reputation was lacklustre (Drescher Reference Drescher1991) and the topic of slavery and abolition drew ridicule in the popular illustrated press (Grimaldo Grigsby Reference Grigsby2015).

Republicans in government did seek to make French abolition meaningful to the general public (Schmidt Reference Schmidt1994; 1999; 2006; 2012). Several government-commissioned paintings staged the iconic ‘emancipation moment’ in the West Indies, repeating the visual ‘cliché of the slave with broken chains looking gratefully at the abolitionist’ (Brion Davis Reference Davis and Boritt1994; Schmidt Reference Schmidt and Araujo2012, 115).Footnote 21 Like abolitionist pictorial practices in the anglophone world, the paintings emphasised reconciliation between planters, officials, and freedmen and women (Brion Davis Reference Davis and Boritt1994; Wood Reference Wood2010). By picturing the gratitude, and distinct submissiveness, of the formerly enslaved, and the apparent benevolence of white abolitionists and colonials, such images rewrote the history of abolition. These paintings exuded a sense that emancipation had been an unanticipated and emotionally charged event, which would be followed by peace and reconciliation. This emphasis on immediacy hid from view the long transatlantic deliberations, the involvement of both black and white international actors, and any fears of violent insurrection. Joyous, spontaneous scenes dispelled worry about repercussions or unrest as they screened from view discontent among planters and anti-colonial sentiments in the Caribbean.

In these state media, the event of abolition, an ‘attractive symbol for revolutionary idealism’, was also explicitly connected to French Republican values (Sessions Reference Sessions2015, 75). Revolutionary symbols, such as the tricolour or a bust of Liberty, were included prominently in the compositions. In all, these images represented the event of abolition as an augur of the future justice and prosperity of the Second Republic (Schmidt Reference Schmidt1999). In the background of the paintings, metonymies of colonial wealth, such as sugar refineries with smoking chimneys, abound. This iconography also expressed the moral legitimacy of the Second Republic, its fulfilment of revolutionary emancipatory promises, and the power of its revolutionary leadership both in France and in the colonies. Allegoric lithographs of the Republican victories of 1848, made for broader circulation, also made reference to abolition in connection to the values of the Republic. Some featured depictions of black enslaved figures actively resisting a chariot representing progress.Footnote 22 All in all, Republicans sought to promote a triumphant memory of abolition in a narrow French Republican register (Brion Davis Reference Davis1984, esp. 284). They also sought to renew imperial confidence. Abolition was no admission of faltering colonial policy, represented no doubts about the previous course. Instead, these images suggested, the Republic was abolishing slavery both physical and spiritual by spreading essential French values. Maintaining this confidence was indispensable, for Republicans, socialists, and feminists alike; after all, despite growing economic critiques of the utility, France at the time was knee-deep in its aggressive pursuit of cultural hegemony as well as settler colonial projects in Algeria (Zouache Reference Zouache2009; Sessions Reference Sessions2015, 90ff.; Andrews Reference Andrews2018; Eicher 2022, 25).

A Revolutionary Window for Women’s Rights

The eventual outcomes of 1848 disappointed progressive commentators both in Europe and America and inaugurated a decade of conservative rule. Not least among those disappointed were those Forty-Eighters (and female quarante-huitardes, Dyxon-Fyle 2006) who had hoped to see a revolutionary change in women’s rights. In several contexts, women used the opportunity to argue for women’s importance to the success of the revolution and for their rights to increased participation in the public sphere (Anderson Reference Anderson1998; Hauch Reference Hauch and Körner2000; Nemes Reference Nemes2001). Women’s clubs and periodicals were founded in Paris, Berlin, and Cologne, over the course of 1848–1849, and 1848 was also the year of the American Women’s Rights Congress at Seneca Falls (Anderson Reference Anderson1998; Offen Reference Offen2000, 108 ff.).

During the February Revolution, male and female radicals in Paris had been brought together, as women had joined men in processions, protests, and clubs (Lucas Reference Lucas1851; Niboyet Reference Niboyet1863; Riot-Sarcey Reference Riot-Sarcey1992, Reference Riot-Sarcey1994; Cross Reference Cross and Kok-Escalle1997; Hauch Reference Hauch and Körner2000; 2001; Lalouette Reference Lalouette2001). Hopeful that the Second Republic might bring them closer to full citizenship, a band of Parisian women initially relied on a typical quarante-huitard repertoire of political action to voice their claims. Prominent among them were several former Saint-Simonians, including the weathered editor Eugénie Niboyet, Jeanne Deroin, Pauline Roland, and Désirée Gay. The group addressed the provisional government through petitions, deputations, and open letters, the most significant flourish of feminist political activity globally up to that moment (Moses Reference Moses1984, Anderson Reference Anderson1998; Offen Reference Offen2000; Schor Reference Schor2022). They also set up regular meetings, most conspicuously the small Société de la voix des femmes, presided over by Eugénie Niboyet. In May 1848 the society started a public-facing Club des femmes, whose short-lived gatherings were disrupted by thousands of rowdy gawkers but did ultimately achieve the goal of raising enough funds to restart their journal, La Voix des femmes (Schor Reference Schor2022, 165–167). In many ways, La Voix was the crux of these various efforts. As the editors perspicaciously explained, since no other newspapers were covering their activities with any degree of seriousness they needed their own – to publicise, collect, transmit, and record for posterity their actions and their significance (Schor Reference Schor2022, 93–94). When, following the repression of the June Days workers’ uprising, clubs were forced to close and women’s political activities curtailed, La Voix also folded. However, the circle kept trying to make themselves heard through the periodical press. Some friendly media, particularly the Fourierist newspaper La Démocratie pacifique (edited by Victor Considerant, 1843–1851) occasionally included their pieces, but they primarily relied on their own productions. After La Voix (edited by Niboyet, March–June 1848), the torch was passed to the monthly La Politique des femmes (edited by Deroin and Gay, June 1848) and L’Opinion des femmes (edited by Deroin, January–August 1849), and, finally, the Almanach des femmes (edited by Deroin, Reference Deroin1851–1854). The group was far from an intellectual monolith and the journals attest to major philosophical and strategic disagreements. How to relate their cause to international affairs and, specifically, to the unfolding history of antislavery, was one of these.

Critics of women’s social status both in France and beyond had been quick to point out what they saw as the contradiction between the provisional government’s swift action regarding colonial slavery and their lack of interest in changing women’s social position. Well-known literary figure Delphine de Girardin opined that the fact that the Republicans ‘freed the Negroes who are not yet civilized, while leaving women, those […] professors of civilisation, in slavery’ proved that they had not understood the true meaning of the Republic (1861 [1848], 468).Footnote 23 American educational reformer Emma Willard addressed a letter to the head of the provisional government, reproaching him for his ‘oversight’: ‘The men of France are called upon to come forward, and by their representatives frame a constitution which they will thus be pledged to support. All the men are called. The slaves too are kindly remembered – but the women – they are forgotten!’ (quoted in Offen Reference Offen1999, 154). The provisional government received a letter to similar effect from Elizabeth Sheridan Carey, an English poet living in Boulogne (reprinted in Fauré Reference Fauré2004, 302).

Anne Knight was a member of this chorus. At a celebratory dinner with antislavery emissaries in London in 1848, she intervened when the topic turned to whether antislavery organisers could now withdraw from France, seizing the moment to bring the discussion to women’s rights. She later reported her conversation to her friend Elizabeth Pease:

The Blacks are free, but there is still a slavery of the Whites. The French took liberty for all the men, and abandoned the rights of all their sisters. We feel that the rights of all human beings are equal; that women, being subject to all the burdens of the State in taxation and penalty of laws, had equal claim with men to vote for the legislators themselves, and having seen the frightful consequences of men’s actions alone, it was our endeavour to place at his side the help-meet for him.

Knight thought her intervention a success and ‘rejoiced’ at the table’s ‘reluctant assent to a great political truth; indeed the logic of it, simply stated, is irresistible’ (‘Anne’ 1884, 11). In this performance, Knight was actively moulding the significance of French abolition. Rather than merely drawing attention to the contrast between women and emancipated slaves, Knight pointed out the ways in which women’s rights claims flowed from the history of abolition, slavery being, to her, a primary case in point of the ‘frightful consequences of men’s actions alone’. The connection between women’s rights and antislavery was a refrain in her advocacy and she tried to inject this connection into the debates over 1848, both in France and in England.

Knight consistently introduced herself as having come to see the importance of women’s emancipation through her work in antislavery. She also emphasised that her track record lent her thoughts on reform authority. With this double move, she turned herself into an embodied example of the connection between the causes. In an open letter to French elected deputy Coquerel, she implored him to support the women’s cause, explaining that she had ‘fought against the oppression of slavery for twenty years; this question and that of the rights of women are one and the same. I will support them both’ (‘Miss’ 1848, 3; see also ‘La Brebis’ 1848, 2).Footnote 24 When La Voix des femmes introduced ‘Miss Kneght [sic]’ to readers in the ‘Faits divers’ section of its eleventh issue, it gave further platform to Knight’s insistence that her women’s rights philosophy was inspired by her antislavery activities: ‘A first idea guided her to another: the slavery of the negro and the slavery of woman approximate each other at more than one point’ (‘Faits divers’ 1848, 4).Footnote 25

Pronouncing her own experience in abolitionism significant grounds for her political agitation, she invited other women to do the same. She would spell out this imperative most completely in her letter to the Sheffield Female Political Association (printed in Reynolds’s Newspaper), calling on readers to devote to the woman question the same efforts they had to the slave’s cause:

Yes, my country-women, be entreated to persevere earnestly in this good cause; it is the genuine anti-slavery. The black slavery was a very small portion; it was only the anti-black slavery. This is anti-slavery complete, and had we begun with this, insisting on our own emancipation first of all, we should not have had to deplore the imbecility of our parliamentary doings for poor negroes, nor the plunder of our country in compensating 20 millions.Footnote 26 Our very hearts bled over masculine monopolous [sic] legislation, our brothers want us at their sides.

Besides equating women’s subjection to that of the enslaved, Knight intimates that women’s suffrage would have overhauled the antislavery campaign altogether and would have avoided crucial mistakes. Seeking suffrage was, she suggested, in fact the primary way in which women could work for the betterment of society. In her series of public letters to dignitaries (twice to Coquerel in 1848; Lord Brougham 1849; Cobden 1850; Bartlett 1852), Knight consistently propagandised this idea. She wrote to Lord Brougham:

the great hater of the race [Satan] persuades both men and women we have our proper sphere in the domestic merely, and that to go from thence, outstep his charmed circle, nothing but infamy! Ah! we have been taught another lesson, by our idle brothers driving us out into the battle-field to combat slavery and war, and every monster that is grasping the throat of our trampled […] country; taught of other slavery than black! compelled to fight with hands tied these foes to our welfare; and now we see and know the evil, some of us; we are demanding the remedy.

The increasingly negative evaluation of the antislavery movement which Knight broadcast did not just reflect her personal experience, she was also prompting readers to consider the tactical lessons they might draw from the history of antislavery. By 1851, Knight had lost her belief in the efficacy of philanthropic efforts and made the advocacy of suffrage her sole focus. She wrote to her friend E. Rooke that the ‘shoals of philanthropic societies’ would not be necessary if the universal vote was obtained so that women could partake in the ‘dirty work’ of politics to drive out the ‘rapacious hordes’ of current lawmakers (Letter to E. Rooke [20 Jan. 1851]). By this time, British antislavery had for her become a negative example of the inefficient pursuit of social change: she asked Richard Cobden to compare the years of unsuccessful campaigning of British abolitionists in Europe with the fact that in 1848, the ‘People-King [Lamartine] abolished black slavery at a breath’ (‘To Richard Cobden’ 1850). In all, then, Knight tried to move interlocutors to see antislavery as a precursor to women’s rights agitation, a meaningful point of comparison, and a powerful argument against the leadership of men alone. She afforded antislavery pride of place in an unfolding feminist usable past.

In doing this, Knight brought a fresh perspective into the Parisian scene. In addition to joining the ranks of women’s rights societies, she published her views in La Voix des femmes and La Démocratie pacifique (‘Ce qui’ 1848; ‘Faits’ 1848; ‘La Brebis’ 1848; ‘Les femmes’ 1848; ‘Miss’ 1848). The main medium of Parisian women’s rights advocacy, Eugénie Niboyet’s La Voix, had sought to legitimate women’s political activity by closely adhering to the rhythms of daily politics of the French Republic (Bérengère 2015, esp. 108). By contrast, Knight connected women’s mobilisation to a decades-long transnational history of women’s agitation against slavery. With her disregard for the national framework and her Garrisonian register of expression, Knight found herself broadly in line with the working-class Jeanne Deroin, Désirée Gay, and Hortense Wild – but not so with the newspaper’s editor. To massage over these differences, Niboyet printed one of Knight’s letters with an explanation that her demands were difficult to realise and that her statement served simply to showcase the allegiance of religious women to their cause (‘Miss’ 1848, 3).Footnote 27

Knight and Deroin soon began to advocate for the ‘complete and radical abolition of all privileges of sex, race, birth, caste and fortune’ (Knight, ‘Notebook’, n.p.). Despite the phrase’s echoes of earlier French revolutionary writings,Footnote 28 this creed measured current developments by an alternative horizon than Niboyet’s strategic adherence to the contours of Republican politics. Calling attention to women’s subjection, putting it first, and framing it through the Republican diction of ‘privilege’, Deroin and her colleagues emphasised that women’s equality was a precondition for proper governance and worldly progress. The privilege of sex, Deroin explained, was the ‘source’ of all the others, ‘the last head of the hydra’ (‘Mission’ 1849, 3; see also Schor Reference Schor2022, 235). They first encapsulated their idea of universal emancipation in this formula in a public letter to Alphonse Esquiros, co-signed with an unidentified A. François, and repeated it throughout their agitational activity between 1848 and 1849.Footnote 29 The statement’s phrasing recalled the October Constitution of the Constituent Assembly, which prescribed the abolition of ‘all distinctions of birth, class or caste [Sont abolis à toujours tout titre nobiliaire, toute distinction de naissance, de classe ou de caste]’ (République 1848, 14).Footnote 30 Women’s emancipation, Deroin explained, was crucial unfinished business of this document:

The Constitution of 1848 has legally abolished the privileges of race, caste and of fortune by the liberation of black slaves, by the forfeiting of noble titles, by the suppression of the income-based franchise. But the privilege of sex has been maintained in this Constitution, undermining it at its base, because it is the negation of the principles upon which it was founded.

The reworking of Article 10 of the Constitution which Deroin promoted undermined any Republican triumphalism. It not only found the abolition of privileges incomplete, but prefixed it with fundamental questions of race and sex. In invoking race, Deroin and her circle referred both to colonial subjects and to the equality of peoples in Europe. Deroin later clarified that ‘humanity cannot walk with nature in the providential paths of progress and of indefinite perfectibility until united work has guaranteed to each of the members of the human family, without distinction of sex or of race, the complete development and free use of all of their moral, intellectual and physical faculties’ (Almanach, 1851, 11).Footnote 32

These claims bore echoes of the Saint-Simonian search for the mère suprême of twenty years earlier. But their expression through the foregrounding of race was new. Rather than Republican inspiration, it reflected transnational alliances that would become more important to Deroin’s circle as the Second Republic began to be dismantled. Already in 1848, they phrased their claims in cosmopolitan terms, not those of the state: ‘for too long we have been excluded from the assemblies in which the great questions are discussed on which the fate of the world rests; [and this] has produced incomplete systems, egoistical laws, fanatical crimes, civil discord and all the miseries which degrade humanity’ (Knight ‘Notebook’, n.p.; see also Riot-Sarcey Reference Riot-Sarcey1994).Footnote 33 The World’s Anti-Slavery Convention of 1840 had been Knight’s pivotal experience of exclusion and she shared with her Parisian colleagues her conviction of the inseparability of national and colonial questions, the realities of slavery and of antislavery, the potential of international collaboration, and, specifically, the discussions that had come to a head at the 1840 Convention.

Deroin’s Internationalism in France and Abroad

While she received few votes, Deroin’s electoral campaign in April 1849 was a powerful occasion to extend the ideas of her circle beyond the confines of her Opinion des femmes (Moses Reference Moses1984, 147–148).Footnote 34 For weeks, she spoke to different assemblies and hung her campaign posters around the city (Deroin ‘Aux électeurs’ 1849; Stern Reference Stern1862)Footnote 35 and the news of her campaign reached the anglophone world.Footnote 36 As part of an ongoing polemic with prominent socialist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, she stated that her demand to be recognised as an electoral candidate was her ‘duty’, rather than winning any votes (‘Réponse’ 1849, 4).Footnote 37 Her close colleague Hortense Wild would later single out for praise Deroin’s sangfroid in daring to set examples ‘premature to the point of being grotesque’ and ‘play the fool to achieve her aims, to satisfy her thirst for justice’.Footnote 38

As part of her advocacy, Deroin reframed French developments from the cosmopolitan perspective of universal emancipation. This outlook would become crucial to the survival of women’s rights discussions into the 1850s. As political auspices for social democracy darkened over the course of the year (Rowbotham Reference Rowbotham, Ash and Wilson1992; Tamboukou Reference Tamboukou2016; Riot-Sarcey Reference Riot-Sarcey1994), Deroin continued her efforts. With Pauline Roland she convened the Association fraternelle et solidaire de toutes les associations, founded to transform the new family of cooperative movements into a general union.Footnote 39 In 1850, the police raided one of their meetings and arrested its leaders on suspicion of seditious behaviour, and in May, Deroin and Roland were sentenced to six months in Saint-Lazare Prison (Pilbeam Reference Pilbeam and Freitag2003, 286–288). During this period, Deroin relied on Anne Knight to ensure her message was being heard and to make contact both with local circles and new networks abroad. This shift from local politics to a transnational orientation was accompanied by substantial investments in memory work to create from the shambles of 1848 a new, usable past. Part of this effort was to reframe abolition, from a French Republican to a cosmopolitan light, as they expressed in their international communications and, lastingly, in the Almanach des femmes.

After their arrest for illegal organising, Deroin and Roland continued their advocacy for women’s rights in prison, petitioning the government and writing to other women’s collectives nationally and internationally (Thomas Reference Thomas1956, 161; Pilbeam Reference Pilbeam and Freitag2003, 278). These included the Sheffield Female Political Association (SFPA),Footnote 40 which Anne Knight had co-founded, the American Women’s Convention in Worcester, and a group in Limoges (Deroin and Roland Reference Deroin and Roland1852; ‘Female’ 1851).Footnote 41 They urged their colleagues to look towards the means of association and collaboration with working-class organisers to achieve their aims. They also addressed male Chartists in Sheffield to urge their solidarity with women, hoping to convince them that the ‘work of enfranchisement [could] not be complete and durable but by the radical extinction of all privileges of sex, race, caste, birth and fortune’ (quoted in Schwarzkopf Reference Schwarzkopf1991, 253). Knight kept them abreast of political developments abroad and certainly facilitated some of their connections (see also ‘To the Editor’ 1853). With her insistent framing over the previous years, Knight also had her share in formulating the international framework of understanding Deroin and Roland invoked.

The letters to Sheffield and Worcester, which shared much of the same wording, both enacted transnational solidarity and theoretically emphasised its importance. Roland and Deroin opened their letter by giving their ‘Sisters of America’ the encouraging news that their Declaration of the Rights of Woman (1848) had reached them in Saint-Lazare. They asserted that women across the world shared a fate: ‘[w]hether she be born on the banks of the Ganges, the Thames or of the Seine, it is the country of her master; for she ever bears the law imposed on her by man’ (‘Female Political’ 1851, 3). In their letter to America, they stressed the progress of ‘fraternal solidarity’ in Paris and blamed the failings of previous associations they had been involved with on the fact that those had been ‘isolated in the midst of the old world’ (Deroin and Roland Reference Deroin and Roland1852, 34). By using abolition as a master frame, they established common footing across different socio-political circumstances, carving a universalist message out of the complicated history of the events of 1848:

The darkness of reaction has obscured the sun of 1848, which seemed to rise so radiantly. Why? Because the revolutionary tempest, in overturning at the same time the throne and the scaffold, in breaking the chain of the black slave, forgot to break the chain of the most oppressed of all the pariahs of humanity.

‘There shall be no more slaves,’ said our brethren. ‘We proclaim universal suffrage. All shall have the right to elect the agents who shall carry out the Constitution which should be based on the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity. Let each one come and deposit his vote; the barrier of privilege is overturned; before the electoral urn there are no more oppressed, no more masters and slaves.’ Woman, in listening to this appeal, rises and approaches the liberating urn to exercise her right of suffrage as a member of society. But the barrier of privilege rises also before her.

Referring to both women and slaves as chained, and moving from the ‘black slave’ to the ‘slavery’ of the disenfranchised, the writers starkly visualised women’s continued disenfranchisement and braided together the causes of women and the enslaved into a single vision of universal emancipation. Moreover, referring to abolition as fruit of ‘the sun of 1848’ rather than of the French Constitution and its by then beleaguered ‘principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity’, the letters reframed abolition through a world-historical lens – which chimed well with the way news of the provisional government’s decree had first been received by reformers abroad.Footnote 42

After she was released from prison, Deroin turned her attention to producing a series of ‘women’s almanacs’. Three instalments appeared between 1851 and 1854, which were explicitly geared towards both French and English readerships, with the second volume appearing bilingually, with both languages printed side by side. Deroin circulated them among the original readers of the Opinion des femmes and reserved copies for the Phalansterian bookstore in Paris (‘Causeries’ 1851, 4; Pilbeam Reference Pilbeam and Freitag2003, 116–119); they served as a source for women’s rights advocates for decades to come.Footnote 43 In all, the almanacs offered a means of connection and continuity for women’s rights advocates in what had become a sizeable diaspora of Forty-Eighters (Pilbeam Reference Pilbeam and Freitag2003; Aprile Reference Aprile2008; Kunka Reference Kunka2016).

The Almanachs included articles on a wide range of contemporary and historical topics, including women’s achievements at home and abroad, the history of Saint-Simonianism, vegetarianism, non-violence, and the Utopian community of Shakers in the US. To collect her materials, Deroin relied on many former contributors to L’Opinion des femmes, even after she had moved to London. They included Jean Macé, Henriette Artiste (Hortense Wild), and Anne Knight (‘Visite’ 1851; ‘To the Editor’ 1853; ‘Lettre de Miss’ 1854). Besides writings by Angélique Arnaud, Eugène Pelletan, and Caroline de Barrau, the almanacs also contain multiple contributions by Anna Blackwell, who was fluent in French, equally interested in romantic socialist theories, and moved frequently between the US and Europe (Wild Reference Wild1890, 474; ‘Les Résignées’ 1892, 1). Deroin published well-known names, such as the Saint-Simonian poet Pierre Lachambeaudie, as well as anonymous contributors and cuttings from various books and periodicals, including the Démocratie pacifique.

Juxtaposing different international developments, the almanacs allowed readers to immerse themselves in a vibrant transnational reform community. The volumes also invited them to reflect on the interconnections between different movements and causes, nurturing the Garrisonian vision of universal emancipation. Events in world history were presented as the shared past of a transnational movement, within which Deroin explicitly situated herself: ‘Since 1848, societies of Women have been organised in France, in America, and in England – composed of females claiming their political rights, that they may themselves watch the future social wellfare [sic] of their children’ (Almanach 1853, vol. 2, 14).

Produced in a single volume, the almanac format was less sensitive to the changing financial and political circumstances Deroin worked in than her more regular periodical publications had been. The medium allowed her to collect articles from her circle over a longer period and could escape the measures taken to progressively restrict the press after the June Days (Bouchet et al. Reference Bouchet2015, pt. 3, n.p.).Footnote 44 It was also a vehicle for memory work par excellence. Almanacs had long been the dominant medium for spreading factual information across agrarian communities (Lyons Reference Lyons2008, 29), but in the 1830s the genre became politicised, when it became both the main form of ‘documentary compendium’ circulated by the antislavery movement and a genre typical of Republicanism (Gosselin Reference Gosselin1993, 290ff.; Goddu Reference Goddu2020, 35ff.). An article on the ‘history, purpose and use’ of almanacs in the République du peuple of 1851, which Deroin read, traced their political significance from Roman Antiquity until the present day, explaining that they had been far from the trivial genre of astrological and meteorological speculations as they had supposedly been made to appear under despotic rule.Footnote 45 Instead, they were the first vehicles of history and political education, recording those personal and national events which ‘[man] wishes to keep in his memory for his own instruction, and for the teaching of the generations who are required to succeed him’ (‘Des almanacs’ 1851, 18).Footnote 46 The author finally concluded that after the disappointments of 1848, almanacs were once again needed to instruct the people in patriotic and Republican values (21). Deroin’s ‘Introduction’ to her own project, where she explained that ‘Today an almanac no longer needs to indicate merely variations in temperature and the position of the stars, but also the variations and diverse tendencies of the heart, and the progress of those social truths that contain the prophecy of a better future’ (Almanach des femmes pour 1852 1851, 9), echoes the same sentiment.Footnote 47

After 1848, Republican almanacs tended to refer back to the revolution of 1789–1794 in their calendars, titles, and imagery (Gosselin Reference Gosselin1993, 291; see also Chambost Reference Chambost, Moggach and Jones2018, 95–97). Deroin’s almanacs, however, hardly looked to this French legacy at all. Instead, they were important archives of memories of antislavery and particularly of Garrisonianism. They featured several long articles detailing aspects of the history of abolitionism and its connection to women’s rights and made short references to memories of antislavery throughout. Editorial decisions clearly reflected Garrisonian reform ideals of universal emancipation from interconnected forms of oppression. This belief was made explicit in the third volume, in a long article on the Société de non-résistance (1854) founded in 1838 by Garrison and some of his followers. The article reprinted the Declaration of Sentiments of the group, who were described as the ‘pure abolitionists’ (‘Société’ 1854, 40), and explained that the different societies discussed over the several issues of the Almanach each in their own way contributed to the women’s cause and to the ‘transformation of the world’ (‘Société’ 1854, 39).Footnote 48

The first almanac contained the article ‘Abolition d’esclavage’, which reproduced much of the Declaration of William Lloyd Garrison’s National Anti-Slavery Convention (1833) and informed readers of the non-violent strategies of the Garrisonians (‘Abolition’ 1851, 163). It noted that the abolitionists accepted women as equals in their ranks, which for the editor, ‘explained without doubt why the abolitionists felt so naturally attached to all works of independence and high morality’ (‘Abolition’ 1851, 167).Footnote 49 The second almanac treated in depth the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (‘Mrs. Harriet’ 1852; ‘The Women’ 1852; ‘American Reply’ 1852). The editor wrote:

In the great regenerating tournament, [woman] has boldly entered and has clamed [sic] a belligerent and glorious position. One lady for ever illustrious in the annals of America, has conquered amidst the plaudits of an entire universe, the purest of reputations, by the publication of those winning pages which relate the history of Uncle Tom. […] It is when man of the freest countries, absorbed in calculation of oeconomy [sic], are intent upon improving the breed of animals, and of completing machinery whilst, from entirely mercenary interests, grave legislators establish temporising compromises upon the eternal and unchanging liberties of man, this woman at once arises; she has unfurled the standard of emancipation of the slave and has drawn from all mankind in a cry of alarm and pity [sic].

The martial characterisation of Stowe as a ‘belligerent’ standard-bearer is a striking echo of Knight’s diction. Deroin also reported on the Duchess of Sutherland’s initiative to organise an address in the name of English women to the women of America – the ‘Stafford House Memorial’. Presumably because she did not have the original address at hand, she reproduced the American reply to it, its barely veiled hostilities notwithstanding. This episode of antislavery prompted the reflection that ‘The year that is just beginning commences therefore under favourable auspices and as for ourselves, who are humble laboureurs [sic] in the work of general emancipation […] we greet respectfully our sisters of 1852’ (‘The Women’ 1852, 202).

Besides translating and circulating these primary materials, the almanacs also amplified other texts that made the connection. The opening article of the first almanac consisted of a report on and partial translation of Harriet Taylor Mill’s landmark text, ‘The Enfranchisement of Women’.Footnote 50 This essay had appeared in the Westminster Review in July 1851 and raised several key liberal arguments for women’s emancipation which John Stuart Mill, Harriet’s husband, would further elaborate in his The Subjection of Women (1869).Footnote 51 The Almanach reproduced and reinforced, through its textual selection, Taylor Mill’s emphasis on the connections between organised antislavery and the rise of women’s rights advocacy (‘Convention’ 1851). It also specified that the history of women’s involvement in antislavery in the US which Taylor Mill argued was relevant to all. Following her observation that the names of the fiercest adversaries of the ‘aristocracy of colour’ were also among the ‘first collective protest against the aristocracy of sex’, the editors explained:

It was not just to the democracy of America that this reclamation of women of their political and civil equality had been addressed; their pressing appeal was also addressed to the radicals and chartists of the United Kingdom, and to the democrats of Europe who demanded universal suffrage as an inherent right, of which the privation is unjust and tyrannical. Yet with what degree of truth or reason can one say suffrage is universal when one half of the human race is excluded?

Deroin did not just bring these historical and analogical arguments founded on antislavery to her own readership – she also added an extra cosmopolitan dimension by pointing out the connections beyond the transatlantic frame.

There are further brief invocations to the history of abolition throughout the almanacs, as well as comparisons between women’s subjection and conditions of slavery. In his ‘Toast a courage morale’ in the first almanac, for instance, Eugène Stourm sought to comfort readers by reminding them that progressive reformers are often mocked: ‘People have laughed at those who relieved in the equality between the races […] people have laughed at those who have proclaimed that slavery is a crime against humanity […] and at this moment, people still laugh at socialists’ (‘Toast’ 1851, 186–187),Footnote 53 while Jean Macé suggested that ‘when people realise women have a soul, no more nor less than the Negro, they will give, one day, what they have given to the negro, for the reason that he too has a soul, just like them, and that this soul comes with rights attached’ (‘5e Lettre’ 1851, 94; see also ‘Votre feuilleton’ 1851).Footnote 54 Combining with the longer articles, these references stitched together a transnational horizon of moral reform and invited readers to see different injustices as inextricably interlaced in a single vision of universal emancipation. Moreover, Deroin’s circle of contributors drew, repeatedly and to powerful effect, on the power of the ‘abolitionist imagination’ of the lone visionary whose vision of justice has yet to be vindicated.

***

Although little is known about her activities after 1854, when the last volume of the Almanach des femmes appeared, it is clear that Deroin kept broadcasting her vision of universal emancipation.Footnote 55 In 1857, she again tried to convince fellow socialists in London to support women’s political equality, taking the floor to remind them that ‘while the revolution had liberated slaves, it had forgotten women’ (Kunka Reference Kunka2016, 59). The almanacs, especially, were a key undertaking to keep dissenting spirits alive and they attest to the transnational collaborations and cosmopolitan imagination that underpinned hopes of woman suffrage in the mid-nineteenth century.