Introduction

Species delimitation is a practical methodological approach to identify independent evolutionary lineages that lack gene flow among them (Sites and Marshall, Reference Sites and Marshall2003; De Queiroz, Reference De Queiroz2007). In general, species should be delimited objectively and through rigorous analyses. Currently, various methods support an integrative taxonomic approach, especially for analysing taxonomically complex groups (Padial et al., Reference Padial, Miralles, De la Riva and Vences2010; Carstens et al., Reference Carstens, Pelletier, Reid and Satler2013). These methods should be complemented with other lines of evidence, such as morphology, behaviour and ecology data (Miralles and Vences, Reference Miralles and Vences2013). The main species delimitation methods are subdivided into de novo inference methods (without a priori defined entities) and validation methods (where predefined entities are tested) (Carstens et al., Reference Carstens, Pelletier, Reid and Satler2013). These methods can be classified into three main categories: 1) distance-based methods such as Automatic Barcode Gap Discovery (ABGD) (Puillandre et al., Reference Puillandre, Lambert, Brouillet and Achaz2012) and Assemble Species by Automatic Partition (ASAP) (Puillandre et al., Reference Puillandre, Brouillet and Achaz2021), which analyse pairwise genetic distances among sequences to detect the presence of a barcode gap, 2) network-based methods, such as the REfined Single Linkage (RESL) algorithm, as implemented in the Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD), which employ a graph-based Markov clustering approach to explore connectivity among sequences through random walks in the network (Ratnasingham and Hebert, Reference Ratnasingham and Hebert2007, Reference Ratnasingham and Hebert2013) and 3) model-based approaches, such the General Mixed Yule Coalescent (GMYC) model (Pons et al., Reference Pons, Barraclough, Gomez-Zurita, Cardoso, Duran, Hazzel, Kamoun, Sumlin and Vogler2006; Fujisawa and Barraclough, Reference Fujisawa and Barraclough2013) and Poisson Tree Processes (PTP) model (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Kapli, Pavlidis and Stamatakis2013; Kapli et al., Reference Kapli, Lutteropp, Zhang, Kobert, Pavlidis, Stamatakis and Flouri2017). These methods apply mixture models with two distinct components, distinguishing within-species and between-species variation. PTP employs two Poisson distributions to model branching events, while GMYC combines a coalescent model with a Yule diversification model (Carstens et al., Reference Carstens, Pelletier, Reid and Satler2013). Despite the variety of species delimitation methods, few have been applied to the study of parasites, mainly in trematodes (Martínez-Aquino et al., Reference Martínez-Aquino, Ceccarelli and Pérez-Ponce de León2013; Herrmann et al., Reference Herrmann, Poulin, Keeney and Blasco-Costa2014; Locke et al., Reference Locke, Caffara, Marcogliese and Fioravanti2015; Pérez-Ponce de León et al., Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, García-Varela, Pinacho-Pinacho, Sereno-Uribe and Poulin2016; Gordy et al., Reference Gordy, Locke, Rawlings, Lapierre and Hanington2017; Pinacho-Pinacho et al., Reference Pinacho-Pinacho, García-Varela, Sereno-Uribe and Pérez-ponce de León2018; Vainutis et al., Reference Vainutis, Voronova, Mironovsky, Zhigileva and Zho-khov2023; Fernandez, et al., Reference Fernandez, Beltramino, Vogler and Hamann2024).

Apharyngostrigea Ciurea, Reference Ciurea1927 is a cosmopolitan genus of diplostomoidean digeneans that parasitize birds of the family Ardeidae (herons) (Dubois, Reference Dubois1968). Morphologically, members of this genus are characterized by the absence of a pharynx (Niewiadomska, Reference Niewiadomska, Gibson, Jones and Bray2002). Currently, the genus comprises 20 species distributed worldwide, associated with ardeids (Dubois, Reference Dubois1938, Reference Dubois1968; Pérez-Vigueras, Reference Pérez-Vigueras1944; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Hong, Ryu, Choi, Yu, Cho, Park, Chae and Park2020). However, the validity of many species within the genus Apharyngostrigea remains controversial, mainly due to their high morphological similarity and the lack of molecular data for their corroboration. Particularly in Mexico, two species of Apharyngostrigea have been recorded; A. brasiliana Szidat, 1929 in the Boat-billed heron (Cochlearius cochlearius L.) in Champotón, Campeche from the Gulf of Mexico, and A. cornu (Zeder, Reference Zeder1800) Ciurea, Reference Ciurea1927 in four ardeids species; Great Egret (Ardea alba L.), Green Heron (Butorides virescens L.), Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax L.) and Yellow-crowned Night Heron (Nyctanassa violacea L.), in the states of Veracruz, Gulf of Mexico and Sinaloa, Mexican Pacific (Hernández-Mena et al., Reference Hernández-Mena, García-Prieto and García-Varela2014; López-Jiménez et al., Reference López-Jiménez, González-García and García-Varela2022). However, a recent study based on molecular analyses of nuclear and mitochondrial genes suggests that the records of A. cornu in Mexico correspond to A. pipientis (Faust, Reference Faust1918) and Apharyngostrigea sp., respectively (Locke et al., Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021).

In the present study, we employed an integrative taxonomic approach, combining morphological examination with multiple molecular species delimitation methods to assess species diversity within Apharyngostrigea in Mexico. We generated new molecular data based on mitochondrial and nuclear genes and provided additional morphological information for specimens collected in southeastern Mexico.

Materials and methods

Specimen collection

Birds belonging to the family Ardeidae were collected between 2013 and 2022 from three localities in the Gulf of Mexican slope and seven in the Mexican Pacific slope (Figure 1; Table 1). Ardeids were identified following Howell and Webb (Reference Howell and Webb1995), and the American Ornithologist’ Union (1998) guidelines. Adults were obtained from the intestine and placed in Petri dishes with saline solution. The collected digeneans were relaxed using heat-killed distilled water and preserved in 70% ethanol for molecular and morphological analyses.

Figure 1. Map of Mexico showing the sampling sites for Apharyngostrigea spp. Localities correspond to those listed in Table 1. Sites marked with a triangle indicate those previously sampled by Hernández-Mena et al. (Reference Hernández-Mena, García-Prieto and García-Varela2014) and López-Jiménez et al. (Reference López-Jiménez, González-García and García-Varela2022).

Table 1. Information on the specimens of Apharyngostrigea spp. Sampled in this study. Collection sites (CS); sampled localities; geographical coordinates; host names, tree label, and GenBank accession numbers

Morphological analyses

Some specimens were stained with Mayer’s paracarmine (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, cleared with methyl salicylate and mounted on permanent slides using Canada balsam. Photographs and measurements were taken with a Leica DM 1000 LED compound microscope (Leica Microsystems CMS GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). All measurements were recorded in micrometres (μm) and are presented as ranges with the mean in parentheses. Voucher specimens were deposited in the Colección Nacional de Helmintos (CNHE), Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Mexico City.

Molecular data

To obtain genomic DNA, preserved samples were digested individually in tubes and digested overnight at 56°C in a solution containing 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7·6), 20 mM NaCl, 100 mM Na2 EDTA (pH 8·0), 1% sarkosyl and 0·1 mg mL-1 proteinase K. Following digestion, DNA was extracted from the supernatant using the DNAzol reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The internal transcribed spacers (ITS1-5.8s-ITS2) of the nuclear ribosomal DNA were amplified using the forward primer BD1 (5′−GTC GTA ACA AGG TTT CCG TA−3′) and the reverse primer BD2 (5′−ATC TAG ACC GGA CTA GGC TGT G−3′) (Bowles et al., Reference Bowles, Blair and McManus1995). Partial fragments of domains D1–D3 of the large subunit of nuclear ribosomal DNA (28S) were amplified using the forward primer 391 (5′−AGCGGAGGAAAAGAAACTAA−3′) (Nadler et al., Reference Nadler, Hoberg, Hudspeth and Rickard2000) and the reverse primer 536 (5′−CAGCTATCCTGAGGGAAAC−3′) (García-Varela and Nadler, Reference García-Varela and Nadler2005). A fragment of cox1, approximately 470 bp in length, was amplified using the forward primer AphaF (5′−TATGATTTTTTTYTTTTTRATG−3′) and the reverse primer AphaR (5′−CCAAACYAACACMGACAT−3′) (see López-Jiménez et al., Reference López-Jiménez, González-García, Andrade-Gómez and García-Varela2023). Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were carried out in 25 μL reaction volumes following the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR cycling conditions included an initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 50°C for 28S and ITS and 55°C for cox1 for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min, with a final post-amplification incubation at 72°C for 10 min. Sequencing reactions were performed using ABI Big Dye terminator sequencing chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Boston, MA, USA), and the reaction products were separated and detected using an ABI 3730 capillary DNA sequencer. Contigs were assembled, and base-calling differences were resolved using CodonCode Aligner v.12.0.1 (CodonCode Corporation, Dedham, MA, USA).

Alignment and phylogenetic analyses

The new sequences were aligned with those of other species of the genus Apharyngostrigea available in GenBank (Supplementary material S1). Matrices for each gene were aligned individually using the ClustalW algorithm (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Gibson, Plewniak, Jeanmougin and Higgins1997) with the default parameters in MEGA v.11 software (Tamura et al., Reference Tamura, Stecher and Kumar2021). Nucleotide substitution models for each molecular marker were selected using JModelTest v.2.1.10 (Darriba et al., Reference Darriba, Taboada, Doallo and Posada2012), applying the optimal Akaike information criterion (AIC) (Akaike, Reference Akaike, Parzen, Tanabe and Kitagawa1974). The selected models were HKY + I for the 28S gene, TVM + G for the ITS gene and T1M1 + I + G for the cox1 gene. Individual gene trees and the concatenated dataset (28S, ITS and cox1) were analysed using maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI). The species Strigea magnirostris (López-Jiménez et al., Reference López-Jiménez, González-García, Andrade-Gómez and García-Varela2023) sequences were used as outgroup to root the trees in all analyses (both individual and concatenated datasets). For ML analyses, we used the software RAXML v.8.2.12 (Stamatakis, Reference Stamatakis2006), to generate gene trees based on the substitution model closest to previous estimates, with 1,000 replicates, using the computational resource Cyberinfrastructure for Phylogenetic Research Science Gateway v3.3 (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Pfeiffer and Schwartz2010). Bayesian inference analyses for individual and concatenated trees (28S, ITS and cox1) were conducting using MrBayes v3.2.6 (Ronquist et al., Reference Ronquist, Teslenko, van der Mark, Ayres, Darling, Ho ̈hna, Larget, Liu, Suchard and Huelsenbeck2012), with Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations run for 10 million generations, sampling every 1,000 generations and discarding the first 2,500 samples as ‘burn-in’ (25%). The results were visualized using FigTree v1.4.2 (Rambaut, Reference Rambaut2012). Additionally, we generated individual gene trees under a molecular clock framework to perform the GMYC analysis using BEAST v.2.7.7 (Suchard et al., Reference Suchard, Lemey, Baele, Ayres, Drummond and Rambaut2018). The analysis was conducted under a Yule model and a coalescent model with a constant population size, using both constant and relaxed molecular clocks. A total of 10,000 replicates were run, ensuring that all output parameters had an Effective Sample Size (ESS) >200.

Species delimitation (discovery and validation)

Species delimitation was performed with two different approaches, following the methodology of Carstens et al. (Reference Carstens, Pelletier, Reid and Satler2013). First, four exploratory or discovery methods were applied to identify potential candidate species based on a priori information using single-gene data (28S, ITS and cox1). Two distance-based methods were employed: ABGD (Puillandre et al., Reference Puillandre, Lambert, Brouillet and Achaz2012) with the following parameters–Pmin: 0·01, Pmax:0·1, Steps: 10, Nb bins: 20 and Jukes-Cantor distances (JC69)–and Assemble Species by Automatic Partitioning (ASAP) (Puillandre et al., Reference Puillandre, Brouillet and Achaz2021), which was run with 1,000 replicates under the JC69 genetic distance model. Additionally, two model-based approaches, General Mixed Yule Coalescent model (GMYC) (Pons et al., Reference Pons, Barraclough, Gomez-Zurita, Cardoso, Duran, Hazzel, Kamoun, Sumlin and Vogler2006) and Poisson Tree Processes model (PTP) (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Kapli, Pavlidis and Stamatakis2013), were applied. The trees with Yule clock, coalescent constant and relaxed clock were generated in BEAUTi and BEAST v.2.7.7 (Drummond et al., Reference Drummond, Suchard, Xie and Rambaut2012) executed for at least 20 million MCMC generations, sampling every 10,000 generations. Convergence of the two chains was assessed using TRACER v.1.7 (Rambaut et al., Reference Rambaut, Drummond, Xie, Baele and Suchard2018). GMYC analyses were conducted in R v.4.1.3 (Allaire, Reference Allaire2012) with the ‘splits’ package (Ezard et al., Reference Ezard, Fujisawa and Barraclough2021) for single and multiple threshold GMYC. PTP analyses were executed using the web server (https://species.h-its.org/) (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Kapli, Pavlidis and Stamatakis2013) with default settings: rooted tree, MCMC generations = 100,000, burn-in = 0·1, seed = 123 and thinning = 100.

Candidate species were assessed using two species validation methods based on phylogenetic trees constructed from multilocus data: BPP and PHRAPL. Bayesian species delimitation was executed using BPP (Bayesian Phylogenetics and Phylogeography) v.4.3.8 (Yang, Reference Yang2015), a Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) program designed to analyse multilocus sequence data under the multispecies coalescent (MSC) model. BPP requires sequence data as input and a predefined guide tree topology (Yang and Rannala, Reference Yang and Rannala2014). It can be used for four types of inference problems (Yang, Reference Yang2015). We conducted an A11 analysis (species delimitation = 1 and species tree = 1): which jointly estimates species delimitation/assignment and species tree models (Yang and Rannala, Reference Yang and Rannala2014). The analysis was run for 100,0000 rjMCMC generations with burn-in = 8,000 and sampling frequency of 2. Additionally, Phylogeographic Inference Using Approximate Likelihoods (PHRAPL) was employed to evaluate alternative demographic and evolutionary scenarios underlying the observed genetic patterns. The analysis was conducted using ML gene trees within the PHRAPL framework, implemented in R v.4.1.3 with the ‘phrapl’ package (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Morales, Carstens and O’Meara2017). Four subsamples per gene tree were used, and the grid search was performed by evaluating 10,000 simulated trees. The five best-fitting models were selected based on their AIC values.

Analysis of morphometric data

For these species recognized through the previous delimitation methods, we conducted a principal component analysis (PCA) to explore and describe the patterns of morphological variation in Apharyngostrigea specimens found in Mexico. A total of 24 morphometrics variables were considered from 47 specimens belonging to four species – A. cornu (n = 10), A. pipientis (n = 10), A. simplex (n = 8) and A. brasiliana (n = 10) (measurements obtained by López-Jiménez et al., Reference López-Jiménez, González-García and García-Varela2022) – as well as two undescribed species, Lineage 1 (n = 7) and Lineage 2 (n = 2). The PCA was performed using the ggplot2, ggfortify, cluster, lfda and reader packages implemented in R v.4.1.3 (R Core Team, 2022) (Supplementary Material S2).

Results

Phylogenetic analyses and species boundaries

Phylogenetic analyses were performed for each dataset individually and for the concatenated dataset. The 28S alignment included 60 sequences with 1,157 characters, the ITS dataset included 64 sequences with 1,057 characters and the cox1 dataset included 72 sequences with 371 characters. The concatenated tree of the three genes (28S + ITS + cox1), including a total of 174 individuals (the same individuals for which all three markers were obtained) (Table 1). These sequences were analysed with other species of Apharyngostrigea available in GenBank (Supplementary Material S1). Trees for individual markers are shown in Supplementary Material S3. In general, the individual trees for each marker showed the same topology, highly supported by posterior probability values. Phylogenetic hypotheses generated through Bayesian analyses of the concatenated sequences (28S + ITS + cox1), as well as results from the species delimitation analyses, are shown in Figure 2. Overall, these analyses recognized four nominal species and two candidate species and/or lineages in Mexico (Figure 2). The first clade consisted of four sequences of A. brasiliana (MZ614714, MZ614716–18) collected from the Boat-billed heron in a single locality from the Gulf of Mexico slope. These sequences formed a sister clade with 26 sequences of Apharyngostrigea, including four sequences identified as A. simplex (MK510081, MH777791, MH777789, MN179319) from Brazil and Argentina (López-Hernández et al., Reference López-Hernández, Locke, de Assis, Drago, de Melo, Rabelo and Pinto2019; Locke et al., Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021). The third clade consisted of two sequences of Apharyngostrigea sp. (Lineage 2) collected from the Snowy egret (Egretta thula Molina) in Champotón, Campeche, Gulf of Mexico in the present study. The fourth clade contained seven sequences collected from the Great blue heron (Ardea herodias L.) in two localities, Emiliano Zapata, Tabasco and Villa Tututepec, Oaxaca, from Mexico. This clade was nested with sequences identified as A. cornu (HM064894, JF769449–50, AF184264) from Canada and Ukraine (Tkach et al., Reference Tkach, Pawlowski, Mariaux, Swiderski, Littlewood, Bray, Dtj and Bray2001; Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Lapierre, Johnson and Marcogliese2011). The fifth clade contained two sequences originally identified as A. cornu from Mexico and reassigned as A. pipientis by Locke et al. (Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021) (JX977838–39), along with sequences identified as A. pipientis (MT677870, MT943784–85 and MT943779) from Argentina and Canada (Locke et al., Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021). Finally, the sixth clade contained two sequences identified as Apharyngostrigea sp. (Lineage 1) from the Yellow-crowned Night Heron (N. violacea) collected previously in the Cortadura, Veracruz by Hernández-Mena et al. (Reference Hernández-Mena, García-Prieto and García-Varela2014), in the Gulf of Mexico and Zapotal, Chiapas, Mexican Pacific, in the present study.

Figure 2. Results of phylogenetic analysis and species delimitation. Bayesian majority rule (50%) phylograms based on the concatenated (28S + ITS + cox1) gene sequences of Apharyngostrigea. Black vertical lines indicate that the corresponding genes in the phylogram and their concatenated sequences were recovered by the different species delimitation methods employed: Automatic Barcode Gap Discovery (ABGD); Assemble Species by Automatic Partitioning (ASAP); Generalized Mixed Yule Coalescent method (GMYC); Poisson Tree Processes (PTP); Bayesian Phylogenetics and Phylogeography (BPP); Phylogeographic Inference Using Approximate Likelihoods (PHRAPL).

Species discovery methods based on mitochondrial data tend to estimate a higher number of species compared to those using nuclear genes (such as 28S and ITS), due to the lower genetic variability observed in nuclear markers. For instance, within the A. simplex clade, species delimitation varied depending on the method used: ABGD and ASAP grouped it as a single species, whereas GMYC and PTP methods recognized two and five distinct species, respectively. In contrast, validation methods such as BPP and PHRAPL consistently supported the presence of four nominal species (A. cornu, A. pipientis, A. simplex and A. brasiliana) along with two candidate species and/or lineages were also recovered in Mexico with high posterior probability support values (see Figure 2). Overall, most species delimitation approaches (discovery and validation), whether based on single-locus or multilocus analyses, recognized four nominal species and two candidate species and/or lineages within the genus Apharyngostrigea (Figure 2).

Morphological differentiation

PCA was conducted to corroborate the morphological differences between the species of Apharyngostrigea found in the present study. Morphometric data were obtained from 47 specimens corresponding to four species – A. pipientis, A. cornu, A. simplex and A. brasiliana–as well as two undescribed species (Lineage 1 and Lineage 2). The combined, simultaneous analysis of all considered groups does not enable a distinction between the entities, due to the conservative morphology of the genus. An exception was observed in the morphometrical data of A. brasiliana, which formed a distinct cluster separate from other species (Figures 3 and 4). Based on cumulative variance and eigenvalues, the first five principal components (PCs) were retained for at least 80% of total variation. However, only PC1 and PC2 were statistically significant. According to the loading values, a combination of 10 variables contributed significantly to PC1, which explained 30·1% of the total variation (95% confidence interval; P < 0·001), while a combination of eight variables contributed significantly to PC2, explaining 19·7% of the total variation (95% confidence interval; P < 0·001) (Supplementary Material S4).

Figure 3. Principal component analyses (PCA) of four species and two lineages of Apharyngostrigea were conducted with 24 variables from 47 individuals.

Figure 4. Photographs of specimens from analysed lineages and species of Apharyngostrigea. (A) Lineage 1. Scale bars = 500 μm. (B) Lineage 2. Scale bars = 200 μm. (C) A. cornu. Scale bars = 200 μm. (D) A. pipientis. Scale bars = 500 μm. (E) A. simplex. Scale bars = 500 μm. (F) A. brasiliana. Scale bars = 500 μm.

Morphological redescription

Apharyngostrigea cornu (Zeder, Reference Zeder1800) Ciurea, Reference Ciurea1927

Host: Ardea herodias Linnaeus, 1758 (Pelecaniformes: Ardeidae)

Locality: Emiliano Zapata, Tabasco, Mexico (17°46’29.14’’N, 91°44’24.91’’W)

Site of infection: Intestine.

Voucher material: CNHE 12482

GenBank accession number: 28S: PX620623–629; ITS: PX620571–577; cox1: PX641999–2005.

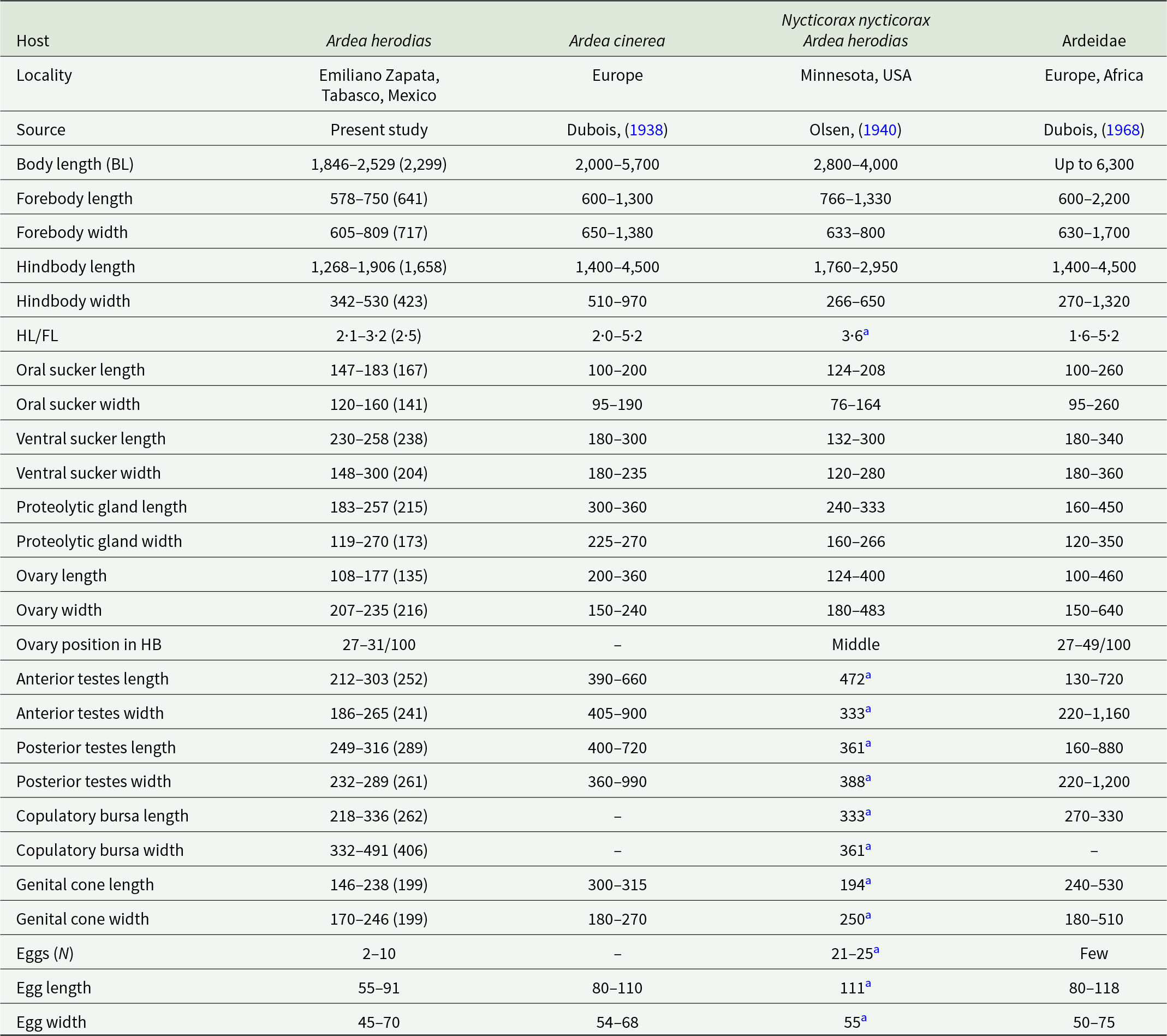

Redescription based on 10 gravid adults (Figure 4C; Table 2). Body distinctly bipartite, 1846–2529 (2299) in total length. Tegument smooth. Forebody caliciform or pyriform, slightly wider than long, 578–750 × 605–809. Ratio of forebody length to body length: 1: 3·1–4·2 (3·5). Hindbody cylindrical, longer than forebody, 1268–1906 × 342–530. Ratio of forebody length to hindbody length: 1: 2·1–3·2 (2·5). Oral sucker subterminal, 147–183 × 120–160. Ventral sucker oval, larger than oral sucker, 230–258 × 148–300. Suckers width ratio: 1: 1·05–1·93 (1·44). Pharynx absent. Holdfast organ has well-developed dorsal and ventral lips. Proteolytic gland well-developed 183–257 × 119–270, situated in the intersegmental region. Testes in tandem are deeply multilobed, and are situated in the second third of the hindbody. Anterior testis 212–303 × 186–265, posterior testis slightly larger than anterior testis 249–316 × 232–289. Seminal vesicle sinuous, postesticular. Ovary oval or reniform, pretesticular 108–177 × 207–235, situated in 27–31/100 of hindbody. Mehlis’ gland and vitelline reservoir in intertesticular region. Vitelline follicles are distributed in both regions of the body, being scarce in the forebody, where they penetrate into the lobes of the holdfast organ, while in the hindbody, they are concentrated in the neck region (preovarian zone), extending dorsally toward the testes and reaching the vesicle seminal or copulatory bursa. Copulatory bursa well developed, 218–336 × 332–491. Genital cone small, 146–238 × 170–246. Relatively few eggs (2–10), oval 55–91 × 45–70. Excretory pore terminal.

Table 2. Comparative measurements of adult specimens of Apharyngostrigea cornu (Zeder, Reference Zeder1800) Ciurea, Reference Ciurea1927

Remarks

Apharyngostrigea cornu was originally described as Distoma cornu by Zeder (Reference Zeder1800), based on specimens found in the intestine of the Grey Heron (Ardea cinerea L.) in Europe. Later, Rudolphi (1809, 1819) transferred it to the genus Amphistoma and subsequently renamed it Monostoma cornu, respectively. Over time, this taxonomic classification became the subject of debate (see Dubois, Reference Dubois1938, Reference Dubois1968). A detailed morphological study of the species was conducted by Ciurea (Reference Ciurea1927). Morphologically, A. cornu is distinguished from its congeners by the presence of abundant vitelline follicles in both parts of the body, a relatively large body size and an ovary situated between 27 and 49/100 of the hindbody (Dubois, Reference Dubois1968). However, our specimens collected from the intestine of the Great Blue Heron (A. herodias) from Emiliano Zapata, Tabasco, in the Neotropical region of Mexico showed a reduced number of vitelline follicles in the forebody compared to previous descriptions (Figure 4C). Additionally, our specimens exhibited some degree of intraspecific morphological variation. For example, they presented lower values in the following characteristics: anterior testes width (186–265 vs 220–1160), genital cone length (146–238 vs 194–530) and egg size (55–91 × 45–70 vs 80–118 × 50–75) (see Table 2). A. cornu has been reported parasitizing primarily ardeid birds in Europe and Africa (Dubois, Reference Dubois1938, Reference Dubois1968; Richard, Reference Richard1964; Olson et al., Reference Olson, Cribb, Tkach, Bray and Littlewood2003). In North America, adult specimens of A. cornu have been recorded in A. herodias and N. nycticorax from Canada and the United States. Additionally, the metacercariae (larval form) have been reported in cyprinid fish such as Catostomus commersonii Lacepède, Notemigonus crysoleucas Mitchill and Pimephales notatus Rafinesque in Canada (Olsen, Reference Olsen1940; Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Lapierre, Johnson and Marcogliese2011).

Apharyngostrigea pipientis (Faust, Reference Faust1918)

Host: Ardea alba Linnaeus, 1758 (Pelecaniformes: Ardeidae)

Locality: Zapotal, Chiapas, Mexico (15°58’20.26’’N, 93°51’23.04’’W).

Site of infection: Intestine

Voucher material: CNHE 12483

GenBank accession number: 28S: PX620632–637, PX620639–652; ITS: PX620578–589, PX620591–98; cox1: PX642031–050

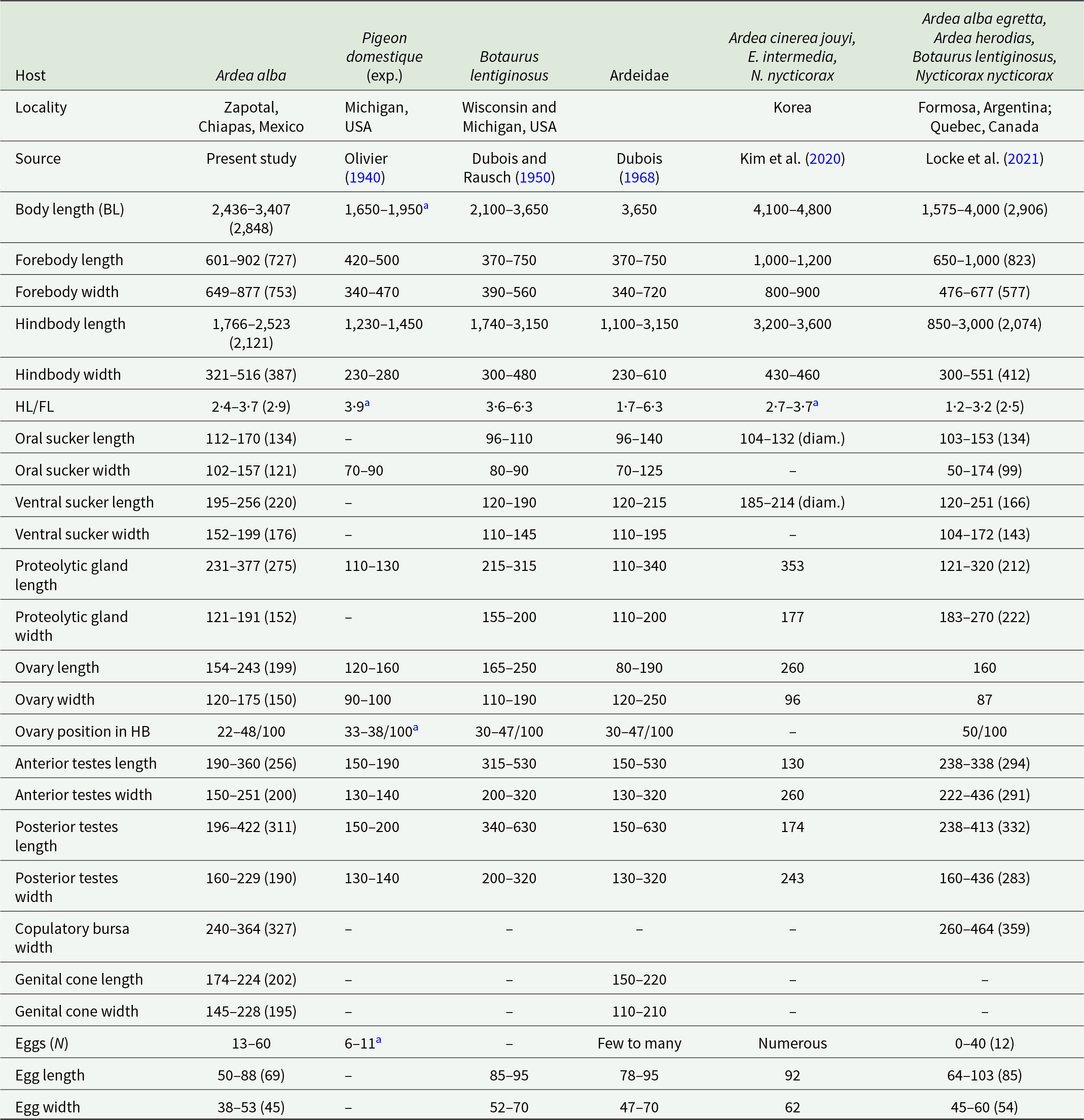

Redescription based on 10 gravid adults (Figure 4D; Table 3). Body virguliform, 2·4–3·4 mm (2·84 mm) in total length. Tegument smooth. Forebody with median opening, 601–902 × 649–877. Ratio of forebody length to body length: 1: 3·4–4·7 (3·9). Hindbody recurved, longer than forebody 1766–2523 × 321–516, with maximum width in testicular zone. Ratio of forebody length to hindbody length: 1: 2·4–3·7 (2·9). Oral sucker subterminal, well developed, 112–170 × 102–157. Ventral sucker, larger than oral sucker 195–256 × 152–199. Pharynx absent. Holdfast organ well-developed dorsal and ventral lips. Proteolytic gland oblongue 231–377 × 121–191, located in the intersegmental region. Testes in tandem multilobed, located in second or third of hindbody. Anterior testis 190–360 × 150–251, posterior testis 196–422 × 160–229. Seminal vesicle long, postesticular. Ovary reniform, pretesticular 154–243 × 120–175, situated approximately 22–48/100 of hindbody. Mehlis’ gland intertesticular. Vitelline follicles occupy the entire length of the hindbody, densely concentrated in the preovarian region, extending dorsally to the testes and reaching the end of the body, with a lower density in the forebody, penetrating into the lobes of the holdfast organ. Copulatory bursa large, 281–388 × 240–364. Genital cone small, 174–224 × 145–228, genital atrium with a small opening. Eggs numerous 13–60 (30), oval 50–88 × 38–53. Excretory pore ventro-subterminal.

Table 3. Comparative measurements of adult specimens of Apharyngostrigea pipientis (Faust, Reference Faust1918)

a Measurements estimated by Locke et al. (Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021).

Remarks

Apharyngostrigea pipientis was described by Olivier (Reference Olivier1940) after experimentally infecting a non-natural host (Pigeon domestique Gmelin) in Michigan, USA. Since then, it has been reported in North and Central America and has been referred to with different names (Dubois and Rausch, Reference Dubois and Rausch1950; Dubois, Reference Dubois1968). Morphologically, A. pipientis is distinguished from its congeners by having an oblong proteolytic gland situated in the upper portion of the hindbody, as well as its virguliform body shape (Dubois, Reference Dubois1968). Our specimens collected from the intestine of the Great Egret (A. alba) in the locality Zapotal, Chiapas, from the Neotropical region of Mexico, are morphologically similar to A. pipientis from previous studies (Figure 4D; Table 3). However, our specimens do not have spines on the tegument as previously reported by Locke et al. (Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021). A. pipientis has been mainly reported parasitizing ardeid birds in the Americas, such as Botaurus lentiginosus Rackett, B. virescens, A. alba egretta, A. herodias, Ixobrychus exilis Gmelin and N. nycticorax from Canada, USA, Cuba and Argentina (Pérez-Vigueras, Reference Pérez-Vigueras1944; Dubois and Rausch, Reference Dubois and Rausch1950; Locke et al., Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021).

Apharyngostrigea simplex (Johnston, Reference Johnston1904) Szidat, 1929

Host: Egretta thula Molina, 1782 (Pelecaniformes: Ardeidae)

Locality: Santa María Cocotepec, Oaxaca, Mexico (15°48’24.56’’N, 97°00’49.79’’W).

Site of infection: Intestine.

Voucher material: CNHE 12484

GenBank accession number: 28S: PX620653–675; ITS: PX620599–621; cox1: PX642008–030

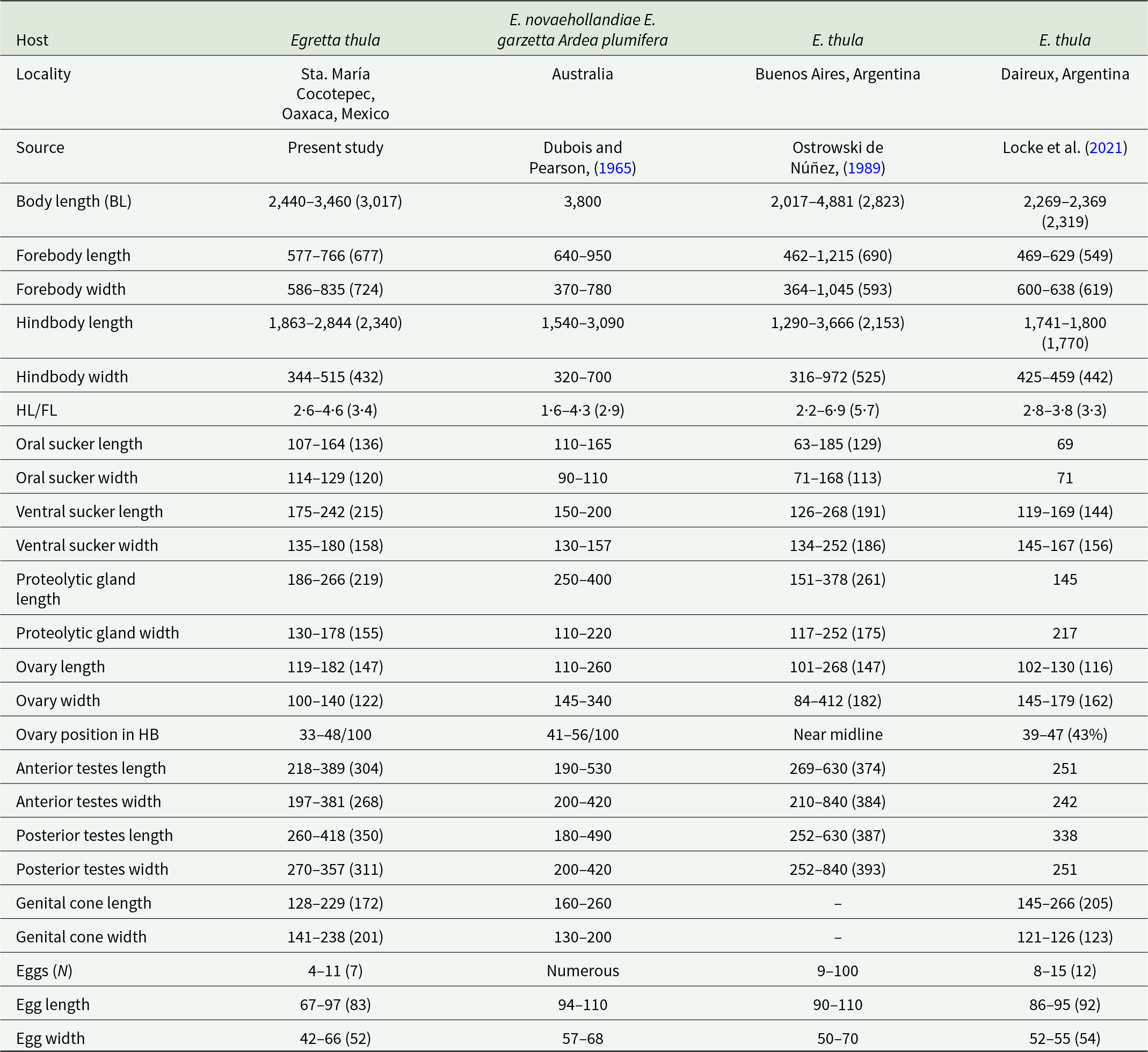

Redescription based on eight gravid adults (Figure 4E; Table 4). Body distinctly bipartite, 2·4–3·4 mm (3·01 mm) in total length. Tegument smooth. Forebody bulbiform, 577–766 × 586–835. Hindbody claviform, longer than forebody 1863–2844 × 344–515. Ratio of forebody length to hindbody length: 1: 2·6–4·6 (3·4). Oral sucker subterminal well developed, 107–164 × 114–129. Ventral sucker oval, larger than oral sucker, 175–242 × 135–180. Pharynx absent. Proteolytic gland is large, 186–266 × 130–178, situated in intersegmental region. Testes in tandem, multilobed. Anterior testis 218–389 × 197–381, posterior testis slightly longer than anterior testes 260–418 × 270–357. Seminal vesicle long, postesticular. Ovary ovoid, pretesticular 119–182 × 100–140, situated approximately 33–48/100 of hindbody. Mehlis’ gland and vitelline reservoir in intertesticular region. Vitelline follicles are densely concentrated in the preovarian region of the hindbody, extending to the posterior margin of the posterior testis; in the forebody, vitelline follicles are sparse and scattered around the with sucker ventral. Copulatory bursa poorly delimited, 227–327 × 222–383, with a slightly developed muscular ring (Ringnapf). Genital cone small, covered with minute spines 128–229 × 141–238. The ejaculatory duct and uterus converge at the base of the genital cone to form the hermaphroditic duct. The genital atrium has a large opening. Uterus with 4–11 (7) eggs, oval 67–97 × 42–66. Excretory pore subterminal.

Table 4. Comparative measurements of adults Apharyngostrigea simplex (Johnston, Reference Johnston1904)

Remarks

Apharyngostrigea simplex was originally described by Johnston (Reference Johnston1904) from the host Egretta novaehollandiae Latham in Australia. Later, Dubois and Pearson (Reference Dubois and Pearson1965) provided a redescription based on individuals collected from other ardeids (E. garzetta and A. plumifera) in Australia. Our specimens, collected from E. thula in the Neotropical region of Mexico, are similar to those described by Ostrowski de Núñez (Reference Ostrowski de Núñez1989) and Locke et al. (Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021) from the same host species in Argentina (Figure 4E, Table 4). However, Locke et al. (Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021) reported the presence of tegumental spines, which in our specimens were observed exclusively on the genital cone, exhibiting a distinct pattern of spination.

Discussion

Species delimitation is a growing area of research in systematic biology (Sites and Marshall, Reference Sites and Marshall2003; Camargo and Sites, Reference Camargo, Sites and Pavlinov2013; Flot, Reference Flot2015). This approach is based on the interpretation of species as independent evolutionary lineages and is in line with the paradigm of integrative taxonomy (De Queiroz, Reference De Queiroz2007). The results of this study, based on four species delimitation discovery methods, such as ASAP, ABGD, GMYC and PTP, and two validation methods, as BPP and PHRAPL, revealed a high diversity within the genus Apharyngostrigea in Mexico. However, the DNA sequence-based approaches using nuclear and mitochondrial genes differed in the number of delimited species for the examined populations of Apharyngostrigea, particularly with GMYC and PTP, which relied on mitochondrial data. This is because species delimitation methods are based on different assumptions to distinguish evolutionary entities among individuals from different populations (Pons et al., Reference Pons, Barraclough, Gomez-Zurita, Cardoso, Duran, Hazzel, Kamoun, Sumlin and Vogler2006; Puillandre et al., Reference Puillandre, Lambert, Brouillet and Achaz2012; Fujisawa and Barraclough, Reference Fujisawa and Barraclough2013; Miralles and Vences, Reference Miralles and Vences2013). In general, the analyses revealed a total of four nominal species (A. cornu, A. pipientis, A. simplex and A. brasiliana) and two candidate species and/or lineages within the genus with high posterior probability support values. Phylogenetic analyses based on nuclear and mitochondrial genes showed that Apharyngostrigea is monophyletic, coinciding with a recent study (see Locke et al., Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021). Additionally, molecular data confirm previous records of A. pipientis in the Americas (Dubois, Reference Dubois1968; Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Bursey and Wong2002; Locke et al., Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021). Our specimens, collected from four ardeid hosts (A. alba, N. nycticorax, B. virescens and Tigrisoma mexicanum Swainson) across seven localities in Mexico, were nested within sequences morphologically identified as A. pipientis from Canada, the United States, Brazil and Argentina (Locke et al., Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021). They are also similar to sequences previously identified as A. cornu from the same hosts in Mexico, which were later reassigned to A. pipientis (Hernández-Mena et al., Reference Hernández-Mena, García-Prieto and García-Varela2014; Locke et al., Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021). This digenean has also been recorded in other ardeid species in Africa and Korea, expanding its distribution range, possibly due to its broad host spectrum (Olivier, Reference Olivier1940; Pulis et al., Reference Pulis, Tkach and Newman2011; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Hong, Ryu, Choi, Yu, Cho, Park, Chae and Park2020). We report for the first time the presence of A. simplex in southeastern Mexico. Our specimens collected from the Snowy Egret (E. thula) are morphologically similar to those reported by Ostrowski de Núñez, (Reference Ostrowski de Núñez1989) and Locke et al. (Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021) from the same host in Argentina. However, A. simplex was originally described by Johnston (Reference Johnston1904) from specimens found E. novaehollandiae and E. garzetta in Australia. Therefore, confirming the presence of this species in the Americas requires molecular comparison with sequences from Australian specimens. Finally, our specimens collected from the Great Blue Heron (A. herodias) in two localities in Mexico (Emiliano Zapata, Tabasco and Villa Tututepec, Oaxaca) clustered with sequences of adult specimens previously identified as A. cornu from the same host, as well as with metacercariae from three cyprinid species in North America (Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Lapierre, Johnson and Marcogliese2011). However, this species was originally described in Europe (Zeder, Reference Zeder1800) from the Great Heron (A. cinerea) and has been reported in several ardeid species in Africa and Central Asia (Richard, Reference Richard1964; Dubois, Reference Dubois1968). Taxonomically, A. cornu exhibits considerable morphological variability, which may be attributed to its wide range of definitive hosts or could indicate a cryptic species complex. Therefore, sequences from European specimens are needed to clarify the status of A. cornu in the Americas (Locke et al., Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021).

Ukoli (Reference Ukoli1967) mentioned the difficulty in distinguishing species of Apharyngostrigea, based mainly on morphological characteristics such as the size and position of organs (e.g. ovary or testes). This variability depends on several factors, including the degree of parasite maturation, the physiological condition of the host, and the contraction or extension of the body during fixation, among others. In this sense, the taxonomic history of Apharyngostrigea is somewhat complex, as many species have been synonymized in various studies due to similar morphological characteristics, further complicating species delimitation (Dubois, Reference Dubois1938, Reference Dubois1968; Mishra and Gupta, Reference Mishra and Gupta1975). In the present study, no distinct morphological differences were observed among the Apharyngostrigea species analysed. PCA did not reveal a clear separation between species of this genus, except for A. brasiliana, which formed a distinct cluster separate from the other species. This analysis also suggests that specimens labelled as Lineage 2 exhibit some characteristics similar to those of A. cornu, and others that bring it close to A. simplex. Further analyses focused on Lineage 2 will allow us to determine whether the observed features result from morphological variation within any of the previously described species for which molecular data are not yet available, or whether this lineage represents a yet undescribed species.

As recently suggested by Cribb et al. (Reference Cribb, Barton, Blair, Bott, Bray, Corner, Cutmore, De Silva, Duong, Duong, Duong, Duong, Duong, Duong, Faltynkova, Gonchar, Hechinger, Herrmann, Huston, Johnson, Kremnev, Kuchta, Louvard, Luus-Powell, Martin, Miller, Perez-Ponce de Leon, Smit, Tkach, Truter, Waki, Vermaak, Wee, Yong and Achatz2025), the recognition of trematode species remains a major ongoing challenge that must be addressed through an integrative approach. As many other genera, Apharyngostrigea includes some well-characterized species and others that are morphologically very similar, suggesting the presence of an unrecognized component of cryptic diversity. The use of molecular markers within an integrative taxonomy framework is crucial for species delimitation, particularly in cases where their taxonomic status is uncertain. The genus Apharyngostrigea currently contains approximately 20 species worldwide, of which six species are reported in the Americas (Ostrowski de Nuñez, Reference Ostrowski de Núñez1989; Hernández-Mena, et al., Reference Hernández-Mena, García-Prieto and García-Varela2014; Locke et al., Reference Locke, Drago, López-Hernández, Chibwana, Núñez, Van Dam, Achinelly, Johnson, de Assis, de Melo and Pinto2021; López-Jiménez et al., Reference López-Jiménez, González-García and García-Varela2022). In this study, four discovery delimitation methods were implemented, such as ABGD, ASAP, GMYC and PTP and two validation methods, BPP and PHRAPL, in combination with morphological data. This study contributes to clarifying certain taxonomic hypotheses regarding species delimitation within this genus, reinforcing the taxonomic status of three species and identifying two lineages that may represent new species. However, further studies incorporating multiple lines of evidence are needed to fully assess the diversity of the genus and to elucidate the phylogenetic relationships among its species. The addition of other congeneric species of Apharyngostrigea from Europe, Africa and Asia Central is imperative to better understand the evolution of this group of digeneans.

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182025101315.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgements

The first author thanks Leopoldo Andrade Gómez and Tonatiuh González García for their help during field work. We are grateful to Laura Márquez and Nelly López for the sequencing service at LaNaBio, UNAM.

Author contributions

A.L.-J., M.G.-V. and R.A.-A. conceived and designed the study. A.L.-J. and M.G.-V. conducted data gathering. A.L.-J. performed phylogenetic analysis. A.L.-J., M.G.-V. and R.A.-A. wrote and edited the article.

Financial support

This research was supported by the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Postdoctoral Program (POSDOC) at Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA-UNAM); and the Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica (PAPIIT-UNAM) IN204425 and Secretaria de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (Ciencia Basica y de Frontera 2025, CBF-2025-I-1433) No 1433 to M.G.-V.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The sampling in this work complies with the current laws and animal ethics regulations of Mexico. Specimens were collected under the Cartilla Nacional de Colector Científico (FAUT 0202) issued by the Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT) to M.G.-V.