Introduction

In this article, seven presenters from the 2025 Beyond Bunya Dieback Symposium: A powerful gathering for Country,Footnote 1 Culture and Collaboration, along with colleague Robyn Fox, respond to a shared concern about the ongoing Bunya dieback and explore ways we can take meaningful action.

The Beyond Bunya Dieback programme, which has hosted two symposia (in 2024 and 2025), is a community-led initiative developed and self-funded by a family-run business, Brush Turkey Enterprises (www.brushturkey.com.au), based in the Sunshine Coast Hinterland, Queensland, Australia. The programme arose from a strong sense of urgency not only as an environmental response but also as a community movement rooted in education, collaboration, and shared stewardship. It combines science, cultural knowledge, and community involvement to address the growing threat posed by Phytophthora and other soil-borne pathogens to the bunya tree (Araucaria bidwillii) and many other native plant species (Hansen, Reference Hansen2015).

The programme seeks to bring together diverse stakeholders, including First Nations Rangers, scientists, land managers, government organisations, artists, educators, and community members, to exchange knowledge and develop practical strategies to slow the spread of dieback. Through the intentional incorporation of transdisciplinary, community-engaged approaches (Riley & White, Reference Riley and White2019) to address biosecurity threats and environmental issues, the Beyond Bunya Dieback programme aims to foster collective action and the co-creation of knowledge, generating new insights (McMichael, Reference McMichael, Somerville and Rapport2000) to address the complex socio-ecological challenges of dieback. This approach foregrounds relational ontologies, recognising the interconnected impacts on Country, people and culture (Riley et al., Reference Riley, Jukes and Rautio2024), and reorienting postcolonial biosecurity structures that have historically favoured Western knowledge, uniformed approaches and reductivist practices (Finlay-Smits et al., Reference Finlay‐Smits, Ayala, Allen, Grant, Greenaway, MacBride‐Stewart, OBrien and Ehler2025). The Beyond Bunya Dieback programme also highlights how environmental education can act as a catalyst for behavioural change, local stewardship, and cross-sector collaboration in addressing complex ecological issues (Ballard et al., Reference Ballard, Lindell and Jadallah2024; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Bailey, Power and McKenzie2021).

While the initial focus was on the Sunshine Coast, we recognised that our local situation is not unique. In Aotearoa/New Zealand, Kauri dieback is devastating ancient forests (Mattea & Monge, Reference Mattea and Monge2025); in Western Australia, Phytophthora cinnamomi has reshaped entire ecosystems (Harshani et al., Reference Harshani, Erickson, McComb, Burgess and Hardy2025); and in California, Sudden Oak Death has transformed landscapes and communities (Rizzo & Garbelotto, Reference Rizzo and Garbelotto2003). By intentionally connecting with stakeholders in these regions, Beyond Bunya Dieback seeks to learn from those who have been navigating similar crises for decades. This brings together diverse community members to exchange knowledge, strategies, and support, strengthening our programme’s ability to respond locally while contributing to a broader global dialogue on plant pathogen management.

Beyond Bunya Dieback has grown into a collaborative platform connecting people and ideas to foster innovative partnerships and inspire action. The programme is built on the belief that by working together across disciplines, communities, and even continents, we can better protect these iconic species and the ecosystems they anchor.

Bunya trees are among the most culturally, ecologically, and traditionally significant trees in Australia (Cooke et al., Reference Cooke, Ens, Clarke, Chang, Rossetto, Crayn, Turpin and Ferrier2024). Towering over subtropical rainforests and open forests, these living sentinels can reach heights of 40 m and live for more than 600 years (Shuey et al., Reference Shuey, Pegg, Dodd, Manners, White, Burgess, Johnson and Pegg2019) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. A healthy Bunya with cones (Araucaria bidwillii). Jinibara Country. Photo by Kim Herringe.

Yet, Bunya face a silent but devastating threat: dieback caused by soil-borne pathogens such as Phytophthora multivora and Phytophthora cinnamomi (Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, 2021). These microscopic organisms infect the tree’s root system, disrupting water and nutrient uptake until the tree slowly declines and dies. The disease is difficult to detect in its early stages, spreads easily through soil and water movement, and has no known cure once a tree is infected (McDougall et al., Reference McDougall and Liew2024).

This loss is further accelerated by the impacts of climate change (Picone, Reference Picone2015), which weaken ageing trees and disrupt a lineage that has endured for hundreds of millions of years (Pye & Gadek, Reference Pye and Gadek2004). In affected areas, the loss of mature bunyas not only alters ecosystems but also erases an irreplaceable cultural connection to Country (Kerwin, Reference Kerwin2011). For thousands of years, Bunya trees have been central to the cultural practices of the Jinibara, Kabi Kabi/Gubbi Gubbi and Wakka Wakka peoples, particularly the gathering of bunya nuts, which brought communities together for large ceremonial and trading events. Bunya is not only a significant tree to these people but also to the wider First Nations communities who were welcomed from far and wide (Haebich, Reference Haebich2003; Swan, Reference Swan2017). Today, these trees are also treasured for their ecological role, supporting a wide range of native species and shaping the landscapes they inhabit.

Dieback in bunya populations (see Figure 2) is part of a broader environmental challenge. Across Australia and globally, Phytophthora species and other soil pathogens are causing widespread mortality in forests, woodlands, and heathlands (Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Edwards, Drenth, Massenbauer, Cunnington, Mostowfizadeh-Ghalamfarsa, Dinh, Liew, White, Scott, Barber, OGara, Ciampini, McDougall and Tan2021). The ecological, economic, and cultural impacts are profound, yet public awareness remains low, and coordinated responses are often fragmented (Dell et al., Reference Dell, Hardy and Vear2005). This gap between the scale of the problem and community understanding presents both a challenge and an opportunity for environmental educators.

Figure 2. Bunya dieback. Jinibara Country. Photo by Kim Herringe.

By outlining the background of the issue, the programme’s structure, and its outcomes to date, this paper provides insights into how community-led environmental education can address biosecurity threats in inclusive, place-based, and impactful ways. While our focus is on the bunya, the principles and approaches described here have wider relevance for managing plant pathogens and fostering resilient ecosystems across Australia and beyond.

The composite framework approach and an outline of the responses

This composite article adopts and expands on a framework established by Quay et al. (Reference Quay, Gray, Thomas, Allen-Craig, Asfeldt, Andkjaer, Beames, Cosgriff, Dyment, Higgins, Ho, Leather, Mitten, Morse, Neill, North, Passy, Pedersen-Gurholt, Polley and Foley2020), which North et al. (Reference North, Hills, Maher, Farkić, Zeilmann, Waite, Takano, Prince, Pedersen Gurholt, Muthomi, Njenga, Karaka-Clarke, Houge Mackenzie and French2024) and Jukes et al. (Reference Jukes, Fox, Hills, White, Ferguson, Kamath, Logan, Riley, Rousell, Wooltorton and Whitehouse2024) also employed. In those articles, positional statements from specific editorial boards on a pressing issue were collected in response to a prompt or provocation. Following the collection of positional statements, collective propositions were generated to highlight shared visions for enacting or creating change. In this article, we have adapted that framework to gather positional statements from seven presenters and one participant at the Beyond Bunya Dieback Symposium, ensuring to elicit responses from a diverse range of perspectives. This was followed by generating collective prepositions as future provocations and invitations.

Using this emerging composite method of inquiry (Jukes et al., Reference Jukes, Fox, Hills, White, Ferguson, Kamath, Logan, Riley, Rousell, Wooltorton and Whitehouse2024), we sought to foreground the eight authors’ lived experience of bunya dieback through a narrative storytelling lens (Gough, Reference Gough1993; Somerville et al., Reference Somerville, McKenzie, Fuller, Godden, Harrison, Isaacs-Guthridge and Turner2023). Through storied accounts, authors were invited to engage with the complexities of the ecological decline of the Bunya tree and to consider how dimensions of environmental education and community action can inform and enact meaningful change. We asked each author to compose a text of up to 600 words to offer a “snapshot” of perspectives regarding bunya dieback in relation to the following prompt.

We invite you to share your lived experience of witnessing Bunya dieback, how you have responded to dieback through your professional practice, and the actions you have undertaken to alleviate dieback and educate others about the cultural and ecological significance of the Bunya tree.

Below are the responses from each contributing author, offering different perspectives on the prompt. They are arranged to guide the reader from recognising ecological decline and dieback (Oakes et al., Reference Oakes, Ardoin and Lambin2016) to a place of active hope (Macy & Johnstone, Reference Macy and Johnstone2012).

The final section of the paper presents a collection of insights drawn from the author’s contributions as a form of future provocations.

Uniting and harnessing the community to create positive change through environmental education

By Karen Shaw: Brush Turkey Enterprises

The Beyond Bunya Dieback programme emerged not only as an environmental response but as a community movement grounded in education, collaboration, and shared stewardship.

We chose the phrase Beyond Bunya Dieback to reflect a forward-looking, hopeful mindset. Inspired by the Aotearoa/New Zealand approach of Kauri Ora (‘Kauri health’), we wanted our programme’s name to emphasise resilience, action, and possibility, rather than despair (Pomare et al., Reference Pomare, Tassell-Matamua, Lindsay, Masters-Awatere, Dell, Erueti and Te Rangi2023) – a reminder that the story of the Bunya is not only about loss, but also about collective care and renewal.

From its inception, the Beyond Bunya Dieback programme has sought to bridge the gap between science, lived experience, and cultural connection. Our approach has been deliberately inclusive, recognising that tackling environmental challenges of this scale requires more than technical expertise. It requires the power of community voice and collaboration. We saw an opportunity to unite Traditional Custodians, landholders, conservationists, scientists, artists, local government and the broader public in a common conversation, rooted in both respect and action (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. We acknowledge and deeply respect the traditional Custodians of Bunya and Kauri Country. Their generous sharing of knowledge and enduring connection to Country enriches our collective understanding and guides us toward more respectful and effective ways of caring for forests and ecosystems. Photo supplied by Karen Shaw.

The programme’s cornerstone has been its annual Symposium held in Jinibara Country, Maleny, Queensland. These gatherings create an accessible space where leading researchers present the latest findings alongside on-ground practitioners and cultural knowledge holders, with over a hundred people attending each event (Nichols, Reference Nichols2024). The atmosphere is less about formal presentations and more about connection, sharing stories, building trust, and identifying practical steps forward. This model was further strengthened when we invited speakers from Aotearoa/New Zealand, Western Australia, and California, regions already confronting the devastation caused by similar pathogens affecting their iconic trees and ecosystems. By listening to their challenges and learning from their strategies, we were able to position the Sunshine Coast within a global network of shared knowledge and resilience. This cross-regional dialogue has revealed that while pathogens may differ in type and severity, the social, cultural, and ecological stakes are strikingly similar, and that there is immense value in partnering with others who have walked this path before us.

Alongside the Symposium, Beyond Bunya Dieback has hosted public talks, facilitated multi-stakeholder workshops, and curated art exhibitions (Forest Heart EcoNursery, 2025), all designed to connect conservation efforts through conversations that resonate across disciplines. We have intentionally included artistic and cultural elements because art has a unique power to reach people emotionally (Curtis, Reference Curtis2009), translating scientific urgency into personal connection. This has been especially important when discussing sensitive topics such as tree death, cultural loss, and the long-term changes facing our landscapes.

Each event attracts a diverse mix of participants, including Traditional Custodians, Indigenous Rangers, and local landholders, as well as scientists, government representatives, educators, artists, students, and concerned community members. This diversity is one of the programme’s greatest strengths. Each person brings a unique perspective, skillset, and story, enriching the collective understanding of the issue. The result is not just a sharing of information, but a genuine co-learning environment where knowledge moves both ways and everyone leaves feeling part of a growing community of care.

Our self-funding of the programme was both a commitment and a catalyst. It allowed us the freedom to shape the programme’s values and direction without compromise, while also demonstrating to potential partners that this work is worth investing in. That initial investment has since attracted interest from local councils, environmental organisations such as Landcare groups, and research bodies, including the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries’ soil pathology team, who can see the momentum building within the community. We anticipate that as the programme continues to grow, stakeholders will see the value in investing their support and expertise, choosing to be part of this collaborative journey and strengthening the outcomes we can achieve together.

The common thread throughout all these efforts is environmental education as a form of empowerment. By making complex science accessible, by valuing Indigenous and community knowledge alongside academic expertise, and by creating spaces for cross-sector dialogue (Richardson & Lefroy, Reference Richardson and Lefroy2016), Beyond Bunya Dieback has turned awareness into action. Participants leave our events not only better informed but also more connected, knowing who to call for advice, how to report pathogen sightings, and what steps they can take to protect local ecosystems.

In an era when environmental crises can feel overwhelming (Albrecht, Reference Albrecht2020), this model offers a hopeful alternative: one in which education is not just about transferring information but about fostering collective capability. The Sunshine Coast’s situation is not unique – pathogens and dieback are emerging issues in many parts of the world (Simler-Williamson et al., Reference Simler-Williamson, Rizzo and Cobb2019). However, by building networks across borders, grounding our work in community, and fostering a culture of shared responsibility, we demonstrate that local action can be amplified through global connection. In doing so, we hope to inspire and equip others to tackle their own environmental challenges – together.

Significance of the Bunya and traditional ecological knowledge

By Aunty Zeitha Jalamala Murphy: Jinibara/Yinibara Elder

Long before two hundred and fifty or so years ago, the passing of time in the Land of Clans, lived many people, animals, trees and other various plants and freshwater life, all in a pristine space of untainted beauty. Holding the value that all of nature is as one, the laws of nature informed our people of how to live in harmony with the surrounding environment, helping to nourish many life lessons.

The vast rainforest that once existed shrank, with only sporadic remnants remaining, as tree cutters felled some of the majestic giants, including the Bunya, known as ‘Bonyi Bonyi’, which were sacred to our people. Clan members were obligated to protect the various totems they carried. It is this connection with nature that also allowed our people to understand various seasons of food resources growing throughout the land. Having this hands-on relationship with the land further allows us to understand the balance of life and to be skilled, for example, in reading the signs of when the country is sick.

Strong songlinesFootnote 2 were also strengthened by family and bloodlines. Stories were shared through an oral history passed down across generations of knowledge holders, carrying the ways of being and doing.

The people of the clans were also mindful not to deplete what is good by sharing the resources of land and water, thus allowing an abundance for others. With a sustainable mindset and respect for shared spaces, the oneness of caring for an integrated ecosystem of nature, humans and animals, learnt to co-exist, until opposing cultural values tipped, crashed, and thus unbalanced the equilibrium of harmony between the non-Aboriginal man and nature.

Sharing learning from Aotearoa: Kauri protection and the cross-cultural approach to caring for Country

By Mita Harris: Ngāpuhi

Kauri is an intrinsic part of Creation as we know it for Māori, a time that transcends time itself. Our story of the parting of the Mother and the Father by Tane to bring light into the world as we know it today (Ruru, Reference Ruru and Turner2020).

For a time, there was darkness, and the children of the mother and father grew restless, chattering amongst themselves. Io Matua Kore gave the mana, the strength to Tane to part his parents for the allowance of Te Ao Marama, the world of light to reach in (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. The Kauri tree brings light into the world. Photo credit: Mita Harris.

And so, it was done, but not all the siblings agreed, and from that time on, Tane has always been challenged.

The world we live in today is just that – a challenge in every way. It wasn’t supposed to be easy; nothing is. Challenges bring us together to understand and achieve objectives. ‘Mahi Tahi’, work as one.

For Kauri protection, we are focused this year on adopting the view that, by working as one, we will achieve much more than we have in the past. Over the past few years, we have gathered the resources, insights, and practices needed to create a comprehensive toolkit for all involved in Kauri protection. It’s time to put these learnings in motion and deliver respectful protection for our great Tree, Te Kauri!

I work on the notion of Maramatanga (Inspiring Light), which suggests that if this is always in front of what we desire, it will always be granted. However, that doesn’t mean you should lean heavily on this and do nothing at all. You have to work with it to achieve the beautiful inspiration you have conjured deep within yourself.

What’s been outstanding is Māori working in, around and on forested lands administered by the Crown and some private land, including Māori Land. There has been a very strong sense of connection and responsibility (Reihana et al., Reference Reihana, Lyver, Gormley, Younger, Harcourt, Cox, Wilcox, Innes and Calver2023). This builds faith in both People, Forest and Sea; they are so interconnected with a great deal of spirit.

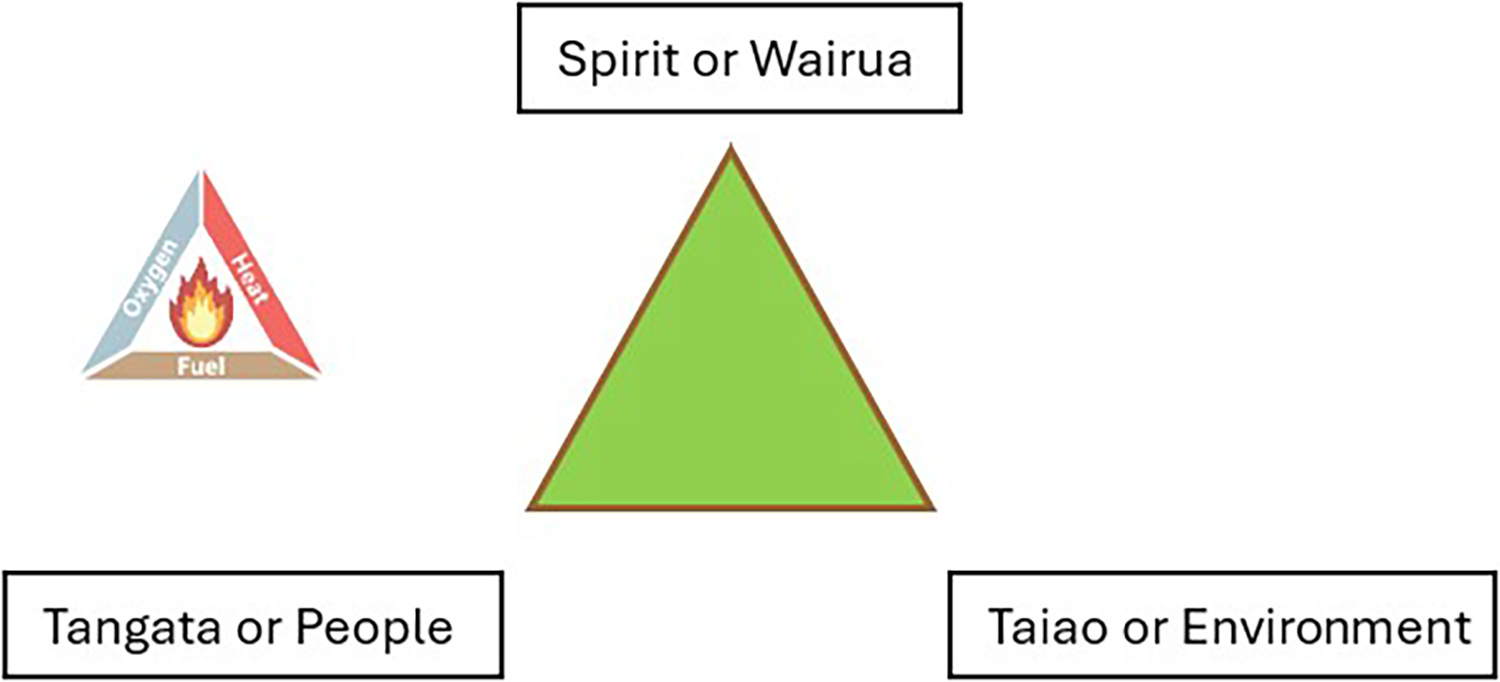

Spirit is all part of the Triangle of Kauri Protection, similar to the fire triangle (see Figure 5). Fire can’t be without Oxygen, Heat and Fuel.

Figure 5. The triangle of Kauri protection. Credit: Mita Harris (Ngāpuhi).

Witnessing landscape degradation and advocating for planetary wellness

By Spencer Shaw: Brush Turkey Enterprises

In writing this, I acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of Bunya Country, the Elders, past, present and emerging and their biocultural connection with this country. This relationship has endured for tens of thousands of years, through ice ages, sea-level rises, and invasions. This connection always was and always will always be.

Bunya (Araucaria bidwillii) is one of twenty surviving species from the family Araucariaceae. This Family is made up of three Genera, Araucaria (e.g. Bunya, Hoop, Norfolk Pine, etc), Agathis (e.g. Kauri’s) and Wollemia (the Wollemi Pine). These trees are one of the oldest surviving families of trees (Picone, Reference Picone2015) and have existed as an evolutionary lineage for at least two hundred million years ago (Hernandez-Castillo & Stockey, Reference Hernandez-Castillo and Stockey2002). Araucaria bidwillii only exists naturally in Queensland, with two small populations in northern Queensland, just inland from Cairns, and a larger population in southeast Queensland (Picone, Reference Picone2015), which extends from Bunya Country on the Blackall and Conondale Ranges and their surrounding catchments in the east, and then to the west on the Bunya Mountains (Smith & Butler, Reference Smith and Butler2002). These are the only ecosystems on earth where the Bunya occurs naturally, a Family of trees that once were widespread across the earth. We who live here are custodians of these iconic trees and the precious remnant rainforest that they are part of.

The condition referred to as ‘dieback’ is generally attributed to the introduction of exotic Phytophthora species. Phytophthora is a genus of Oomycete (water mould) that can become plant pathogens (Cooke et al., Reference Cooke, Drenth, Duncan, Wagels and Brasier2000), particularly in plants that a) have not evolved and developed the necessary resilience to these organisms or b) ecological change has occurred so that plants such as Bunya are more susceptible to suffering disease or mortality caused by these organisms e.g. land clearing, soil degradation, hydrology changes, habitat fragmentation, feral animals, changes in temperature and rainfall (Cahill et al., Reference Cahill, Rookes, Wilson, Gibson and McDougall2008). Phytophthora enters the living tissue of plants, feeds on them, and can potentially kill infected areas of the plants, generally the roots and lower stem. As a result, the whole plant weakens and can die (Hardham & Blackman, Reference Hardham and Blackman2018).

The pathogen-based decline of Bunya trees, now referred to as Bunya dieback, has been observed and monitored in South-East Queensland for nearly two decades (Ballard et al., Reference Ballard, Lindell and Jadallah2024). It was first recorded in the Bunya Mountains. Sadly, their trees, which were up to 600 years old, rapidly succumbed to this disease and died within a year or two, particularly during droughts (Shuey et al., Reference Shuey, Pegg, Dodd, Manners, White, Burgess, Johnson and Pegg2019). Just over five years ago, we began observing and recording dying Bunya on the Blackall Range, Sunshine Coast Hinterland. On the Blackall Range, Bunya trees showing visible symptoms or that have already succumbed to dieback are generally limited to those in highly modified landscapes that have been cleared, e.g., rural or rural residential areas. Bunya have evolved as a forest organism, and although through the lens of Western society we tend to view all organisms as separate entities, they are, of course, intrinsically intertwined with the life they have evolved and cooperate with (Ritter & Dauksta, Reference Ritter and Dauksta2013) in the case of Bunya, over hundreds of millions of years. We know with ourselves that if we are feeling run down or suffering from a poor diet, we may be more susceptible and vulnerable to disease. It’s the same with anything in nature, including trees. Just as we are learning the importance of our gut health, which is crucial to our overall well-being, soil health is equally crucial for plants (Lehmann et al., Reference Lehmann, Bossio, Kögel-Knabner and Rillig2020). So, it is with Bunya that are surrounded by lawn or paddock, that they find themselves in a situation that they have not evolved in; their overall health is reduced, and because of this, they are more vulnerable to disease.

Exploring the potential of fungi in ecosystem restoration

By Pierre Loiseau and Rachael Sanderson: Mycologist and organic farmer at We Forest Earth (https://weforestearth.com.au)

Conventional land management practices worldwide, including those in Australia, have and still rely heavily on chemical use for weed management and bush regeneration (Thompson & Chauhan, Reference Thompson and Chauhan2022). The application of these herbicides has detrimental effects on both human health and ecosystem health (Parven et al., Reference Parven, Meftaul, Venkateswarlu and Megharaj2025). Glyphosate is the primary herbicide used in agriculture (Low, Reference Low2020) and negatively affects the microbial composition of the rhizosphere, plant endosphere and the surrounding soil. It negatively impacts key members of the soil microbiome, including arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, pseudomonas and rhizobia, disrupting key nutrient cycling, decreasing plant health, and increasing the risk of pest pressure (Van Bruggen et al., Reference Van Bruggen, He, Shin, Mai, Jeong, Finckh and Morris2018). Most importantly, the application of glyphosate increases the risk of pathogenic microbes, such as Phytophthora cinnamomum, inhabiting the soil and killing host trees, such as Araucaria bidwillii.

‘Organic’ land care management is the management of land through sustainable ecological systems that promote biodiversity, increase biological cycles, and improve soil activity. Organic land management uses no herbicides, pesticides, or synthetic fertilisers (Northeast Organic Farming Association, 2017), thus preventing the side effects mentioned above. Some techniques used to recreate healthy ecosystems include manual hand removal, chopping and dropping, tree popping, ringbarking, and biological controls (Northeast Organic Farming Association, 2017), and have been used to facilitate the successional advancement of these ecosystems.

We Forest Earth is a not-for-profit based in the Northern Rivers, Australia, focused on organic and ecological land restoration. We Forest Earth is exploring the use of fungi (see Figure 6) as an extra tool in organic land management to turn woody weeds into food and medicine. We believe fungi have the power to restore ecosystems without the use of herbicides like glyphosate. This new approach is called: Mycoregen (noun), the use of endemic mycelium to phase out woody weeds.

Figure 6. Pierre holding an inoculated specimen of Cinnamomum camphora fruiting Tremetes versicolor. A large Cinnamomum camphora can be seen in the background, breaking around the ring bark. Photo by Rachael Sanderson.

Through targeted wounding and inoculation of weed specimens, Mycoregen ensures the effective cultivation of the chosen fungal strain within the host woody weeds’ biomass, whilst keeping both the microbiome and ecosystem intact (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Cinnamomum camphora fruiting Tremetes versicolor eight months post-inoculation. Photo by Rachael Sanderson.

The utilisation of Mycoregen in bush regeneration not only reconnects people with Country through their immersion in nature during the restoration works, but has proven multiple benefits, including:

-

Through ringbarking, the canopy remains intact for longer, creating conditions that support the germination of native understory seeds.

-

Sudden canopy drop results in fast germinating weed species flourishing.

-

The process creates the collection of sugars above the ringbark, providing a food source for local fauna (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Evidence of significant browsing on Cinnamomum camphora post-ringbark highlights the swallow bark, which becomes a food source for local fauna. Photo by Rachael Sanderson.

-

The introduction of fungi fast-tracks nutrient cycling, meaning the weed species is then fed back into the nutrient cycle and distributed to native species much more quickly.

-

The transpiration cycle remains intact, ensuring water is pumped from the soil to the canopy. This process continues to prevent the soil from becoming waterlogged and mitigates the potential for Phytophthora to take hold.

-

The remaining canopy keeps the delicate microbiome intact, allowing for a better transition of successional species. The microbiome, which would otherwise be destroyed or put under considerable stress during the fast canopy drop, due to the increase in direct sunlight to the area.

-

Promotes a circular economy by growing and harvesting gourmet and medicinal mushrooms through targeted inoculation.

In addition to Mycoregen in organic land management, We Forest Earth is exploring an approach of mycoremediation to improve soil conditions, remove toxins and treat infections such as fungi blight, proven by Stamets (Reference Stamets2005) in his work in the United States through the application of endemic species of saprophytic fungi in wood chips in areas in need of remediation. Naturally occurring edible and medicinal species in Australia, such as Pleurotus sp., Tremetes sp. and Psylocibe sp., have all been linked to remediating soil contamination through their application (Stamets, Reference Stamets2005) and can be used in this context.

We Forest Earth recognises the array of gourmet, not yet commercialised, endemic fungi species we have in Australia. The potential of using native fungi in ecosystem restoration highlights a non-invasive possibility to address pathogen-led dieback.

Giving the natural world a voice through art

By Jono Bateman: Environmental artist and bush regenerator

As an environmental artist who has spent the past twenty years working in the Southeast Queensland Hinterland as a forest manager and bush regenerator, I have been privileged (and saddened) to observe firsthand the actions, interactions, and consequences of human-induced changes to our natural environment. As a forest manager and bush regenerator, my role is to assess the impacts of these interactions and implement practical strategies on the ground to help restore ecosystems to their original, natural, and healthy state. As an environmental artist, I aim to involve the public in these environmental observations, using art as a universal language to evoke emotion and imagination and to give meaning to the conversation (Igdalova et al., Reference Igdalova, Nawaz and Chamberlain2025).

It is through this social engagement that real change can occur. Shifting attitudes and behaviours within society to take preventive action to care for our environment is a far more powerful tool than a few people fixing the problem. One constant observation that informs my art is that in nature, nothing ever repeats itself. Patterns and movements of organisms and processes are forever adapting, adjusting and evolving to stay strong. Otherwise, there would be no evolution. Precise repetition, like modern man-made engineering, would just go around and around until it wears out and stops. That is not a world that will fix things like the spread of Phytophthora cinnamomi.

Since nature has refined the art of change to survive, so too must we. My firsthand observations of Bunya dieback in our local Hinterland forests some years back added yet another layer to the long narrative about our relationship with the natural world that informs and motivates my art. To see such an ecologically and culturally significant species suffer to the point of no return due to a simple and totally preventable uninformed agricultural practice is heartbreaking.

It’s a problem caused by people with no connection to the bush, so for a solution to emerge, it’s a story that needs to be shared. My environmental art falls under the category of “representational”, which emphasises visualisation and communication (Miles, Reference Miles2010).

Science communication is a field that continues to expand, especially at a time when we face multiple environmental crises and declining public trust in science, technology, and politics (Bloomfield, Reference Bloomfield2024). Science communication relies heavily on science journalism to bridge the gap between science and society (Mosia, Reference Mosia2025). Yet a bridge suggests there are two sides, implying you are either on one side or the other. Still, it is a valuable step in the right direction.

Then there is art in science. Whilst science journalism builds the bridge, art in science is more like the river that flows under it. In its waters, knowledge and ideas seep into our being as they flow through the social landscape. Art broadens our perspective and brings about new ways of understanding and interconnectedness (Casazza et al., Reference Casazza, Ferrari, Liu and Ulgiati2017). The emotions and imagination inspired by art, in all its forms, influence human behaviour and are the core of system change (Marks et al., Reference Marks, Chandler and Baldwin2016). This is often a great motivator for a groundswell of action and change. Of course, there is no substance nor integrity to the messages and meanings of environmental art, unless it is well informed by sound science. As this powerful partnership between art and science continues to evolve, the strength of social knowledge can only lead to greater engagement with environmental issues, ultimately enhancing the likelihood of positive behavioural change.

My affiliation with the Beyond Bunya Dieback programme has enabled me to draw on a scientific, research-based understanding of Bunya dieback to inform my art. In the painting ‘First Contact’ (see Figure 9 above), which formed part of the recent Beyond Bunya Dieback Symposium in Maleny, the viewer is confronted with a real-life scenario unfolding before them to contemplate.

Figure 9. Jono Bateman’s painting ‘First contact’ showcases the lateral root hairs of the Bunya seed making first contact with the roots in the soil. Photo by Jono Bateman.

In this painting, a germinating Bunya seed at the very beginning of its long journey to becoming a magnificent tree lies in hope, waiting for its fragile root hairs to make first contact with the soil. Is the soil safe? Is it healthy? Can I trust it? The fate of this emerging Bunya pine rests entirely upon the consequences of modern human intervention. Does the title “First contact” stir up other emotions about colonial impacts?

How can these emotions give people real agency in bringing about change?

If art can influence human behaviour, then simply by becoming aware, informed, and open to new ideas, attitudes will change. With new attitudes come new actions. The Beyond Bunya Dieback programme has provided a powerful platform for a diverse range of passionate practitioners to advocate for environmental engagement and change. By engaging with this broad group, the network, like a mycelium web, has great potential to reach far and wide.

Whilst the world’s wonderful scientists and researchers strive for greater knowledge and answers, the world’s artists engage in greater participation and build deeper social knowledge. There is no tool more powerful to stimulate a response than emotion. And when it matters to all of us, let’s hope that art in science puts that powerful tool to work.

Cultivating awareness of the spread of soil pathogens and the importance of soil hygiene practice to the outdoor education sector

By Robyn Fox: Outdoor Environmental Educator

As a participant in the Beyond Bunya Dieback 2025 symposium, I was moved to take action by educating my students about dieback and developing practices and protocols to reduce its impact. This led me to reflect on the following:

Soil hygiene, biosecurity practices, and education should be regarded as essential components of Outdoor Environmental Education (OEE) programmes across Australia. However, to date, no identified research has been conducted on biosecurity protocols and practices within Australia’s OEE sector, and it remains unclear which protocols, if any, are being implemented.

Each week, thousands of OEE activities take place throughout national parks, state parks, and conservation areas across Australia. The large number of students, outdoor equipment and vehicle movement involved in these OEE programmes pose a genuine risk of spreading soil pathogens to new locations (Dolman & Marion, Reference Dolman and Marion2022; Gill et al., Reference Gill, McKiernan, Lewis, Cherry and Annunciato2020).

The OEE threshold concepts (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Grenon, Morse, Allen-Craig, Mangelsdorf and Polley2019) propose that outdoor education graduates from the Australian university sector should be ‘place responsive and see their work as a social, cultural and environmental endeavour’ (p. 176). They should also ‘advocate for social and environmental justice’ (p. 178).

With the OEE university graduates aiming to enact these threshold concepts and strengthen students’ connection to Country through place-based learning (Sutton et al., Reference Sutton, Bellingham and White2023; Wattchow & Brown, Reference Wattchow and Brown2011) and planetary conscious pedagogies (Strachan & Markwick, Reference Strachan and Markwick2025), the landscape and more-than-human worlds can be perceived, felt, and experienced in reciprocal, relational and embodied ways (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Whintors and Bailey2023) rather than as a ‘featureless backdrop’ to outdoor adventure activities (Stewart, Reference Stewart2008, p. 94).

Jukes (Reference Jukes2023) challenges us to pay closer attention to the spatial–temporal specifics of granular stories as we encourage our students to engage in OEE with ‘thinking with a landscape’ (Jukes, Reference Jukes2021) as they grapple with the current precarious times and the implications of climate change in OEE (Fox & Thomas, Reference Fox and Thomas2023).

During a recent field trip walking in the Glass House Mountains in SE QLD, students in the OEE course I teach encountered what they described as ‘a skeleton forest of trees’. We paused to observe. Some students then laid down and looked up through the trees’ lifeless canopies, whilst others silently walked amongst the trees, taking annotated notes, drawings, and observations in their field naturalist journals.

Whilst we stopped for lunch at a lookout that overlooked the ‘skeleton forest’, students were keen to inquire deeper into what they had experienced. Field guidebooks and Google searches soon informed us that the skeleton trees are, in fact, Bunya pines (Araucaria bidwillii), a species that has existed since the Jurassic period and can live up to 600 years (Shuey et al., Reference Shuey, Pegg, Dodd, Manners, White, Burgess, Johnson and Pegg2019). Other discoveries included the significance of the Bunya tree in First Nations culture, the weight of a Bunya cone and the source of the Bunya’s dieback, caused by the spread of the soil pathogens such as Phytophthora cinnamomi, introduced into Australia by an exotic plant.

As we neared the end of our hike, we stopped by a creek, and students reflected on their lived experience of witnessing the Bunya dieback. They chose two reflection prompts. One adapted from Burton (Reference Burton2024) invited them to write and illustrate the dieback, engaging their bodies, minds, and hearts as they explored their eco-emotions. The other was to write a eulogy incorporating the ideas of deep time, intergenerational responsibility (Magnason, Reference Magnason2020), and active hope (Macy & Johnstone, Reference Macy and Johnstone2012) from the perspective of the Bunya tree.

Upon reaching the trailhead, we encountered the soil hygiene station once again. The students methodically scrubbed their boots to remove any debris, took off their gaiters and placed them in a tub for disinfecting and dunked their hiking pole tips into a small screw top jar of disinfectant. In this moment, biosecurity became more than a protocol. It became a relational practice, rooted in respect for Country, the more-than-human world, and future generations.

Cultivating an awareness of the spread of soil pathogens and implementing soil hygiene practices when integrated into OEE programmes can serve as pedagogical tools, inviting students and the OEE sector to engage ethically and attentively in the landscapes they traverse.

Concluding insights: an offering

Using a composite approach, we gathered narratives from eight contributors who responded to prompts about confronting dieback through their unique lived experiences and professional practices, reflecting on the plight of the Bunya tree. From these reflections, we offer the following collectively generated propositions – not as definitive solutions, but as a framework for thinking and acting that may support those navigating tree dieback and advocating for regenerative forest practices.

Honour traditional knowledge and custodianship: The Beyond Bunya Dieback programme demonstrates that genuine progress in environmental education and protection starts with honouring, listening to, and being guided by Traditional Custodians’ philosophies and knowledge (Winter, Reference Winter2021). Indigenous worldviews, intergenerational cultural and ecological knowledge, offer deep-time perspectives on ecosystem health and should be situated at the forefront of guiding current responses to regenerative forest practices and planetary wellbeing (Poelina et al., Reference Poelina, Paradies, Wooltorton, Guimond, Jackson-Barrett and Blaise2023).

Build collaborative networks and capacity to respond to ecological decline: The Beyond Bunya Dieback programme demonstrates that addressing complex ecological issues, such as Bunya dieback, is most effective when intercultural, transdisciplinary, and collaborative approaches are adopted across sectors. This fosters networks of trust and shared responsibility. Through annual symposia, international outreach, and collaboration across regions facing similar crises, the programme has established enduring networks that motivate participants to embrace regenerative land management and forest hygiene practices, advocate for stronger protections, and uphold ethics of care (Rousell & Tran, Reference Rousell and Tran2024). These efforts continue well beyond each event, creating ongoing ripple effects of care, action, and hope.

Leverage art for ecological awareness and action: The Beyond Bunya Dieback symposium deliberately features a parallel art exhibition, inviting both participants and the wider public to view Bunya dieback through an artistic lens. In this way, art acts as a conduit for “another way of seeing” (Grosvenor & Roberts, Reference Grosvenor and Roberts2025, p. 679), offering perspectives that extend beyond scientific discourse. Art can serve as a provocation by fostering emotional connections between people and places (Papavasileiou et al., Reference Papavasileiou, Nikolaou, Andreadakis, Xanthacou and Kaila2021), evoking feelings of empathy, wonder, grief, and hope. It is also a powerful means for artists to express ecological concern through creative expression. In doing so, art is not only a way to respond to ecological concerns and environmental injustices but also a catalyst for social change and environmental activism for both the artist and the viewer.

Empower community and business leadership: The Beyond Bunya Dieback programme demonstrates how small, values-driven businesses can act as catalysts for environmental education and change. Through self-funding and grassroots leadership, local enterprises or businesses can address local issues, shape project direction, mobilise community energy, inspire systemic change and share ownership of outcomes. This enables organisations to act quickly and respond to urgent biosecurity threats whilst developing programmes tailored to community needs, rather than being hampered by bureaucratic timelines and paperwork.

Catalyse awareness into action: The Beyond Bunya Dieback programme emphasises that education is more than just transferring information; it is a relational process that builds shared understanding, trust, and collective social capacity and action. By prioritising reciprocity and cultivating an open, inclusive approach, the programme ensures that everyone recognises their role and feels empowered to act and contribute. Through this lens, the programme frames learning and activism as a participatory practice in which stakeholders co-create solutions, strengthen networks, and develop the skills and confidence needed to respond to dieback and advocate for regenerative forest practices, while providing clear pathways for action.

Tree dieback and breaches in forest biosecurity, although not new issues, require urgent and sustained attention. The dieback and loss of iconic flora, such as the Bunya, signal a broader ecological unravelling threatening biodiversity, forest health, and the resilience of ecosystems (both human and more-than-human). Climate change, with its intensifying rainfall and higher temperatures, coupled with global migration, trade, and expanding transport routes, amplifies the risk of biosecurity breaches and pathogen spread. These pressures should serve as a call to action: to strengthen biosecurity protocols, to deeply listen and observe Country for signs of ecological change, and to engage in reciprocity with the living systems that sustain us.

This article serves as a stimulus for those committed to regenerative ecological practices. May the stories shared by the individual contributors and the collective prepositions derived serve as an inspiration, an impetus, and a framework for guidance, empowering environmental advocacy and action – shifting conversations from reactive problem-solving to proactive stewardship. We invite you to be part of the conversation and provide a voice for forest health in your communities. Bunya trees have existed for millions of years; let us make sure they, along with other species and the cultural and ecological stories they embody, do not disappear on our watch, due to inaction.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the Countries in which we are located. We recognise and honour the Elders, past and present. We also gratefully acknowledge Kim Herringe for generously allowing us to use two of her photographs of Bunya trees in this article. Finally we would also like to thank the AJEE editorial team and article reviewers for their support and guidance throughout the publication process.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical standard

Nothing to note.

Author Biographies

Robyn Fox is an associate lecturer at the University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia, specialising in outdoor environmental education. She is also an active member of the Queensland Association of Environmental Education Chapter and Queensland Outdoor Educator’s Association.

Karen Shaw is an environmental educator and co-director of Brush Turkey Enterprises. She leads the Beyond Bunya Dieback events, encouraging cross-cultural and international collaboration to protect iconic species and the landscapes they inhabit.

Spencer Shaw is a bush regenerator, horticulturalist, consultant, ecological educator, and co-director of Brush Turkey Enterprises, with over 25 years’ experience in ecological restoration. His work emphasises holistic land management, building community connections to Country, and defending ecosystems against emerging threats such as dieback.

Aunty Zeitha Jalamala Murphy is an active and passionate advocate for Caring for Country, focusing on a continued, integrated understanding of not just her people’s cultural values. As a survivor of the Stolen Generation, armed with a Behavioural Science degree, an Elder, and a descendant from the Dalla Clan of the Jinibara/Yinibara nation, her main focus is educating all people about the significant ways of caring for the human mind, as well as the biodiversity and ecological health of our planet.

Mita Harris is a cultural heritage specialist and Kauri protection advocate, working across Aotearoa/New Zealand to protect forests through a kaupapa of “Mahi Tahi” (working as one). He brings deep knowledge of cross-cultural approaches to caring for Country, grounded in traditional Māori perspectives and modern forest protection methods.

Pierre Loiseau is a Founding Director of We Forest Earth and our lead citizen mycologist. Born in Aotearoa, he was motivated by his appreciation of natural processes and awareness of poor land management practices to explore holistic alternatives.

Rachael Sanderson is an organic farmer and bush regenerator passionate about protecting ecosystems and producing organic food. She is the Secretary of We Forest Earth, a Not-for-Profit based in the Northern Rivers, providing chemical-free bush regeneration. She runs Raven Place Farm, an organic and regenerative farm committed to making organic food accessible to everyone.

Jono Bateman is a self-employed environmental artist and bush regenerator in the Sunshine Coast Hinterland. His ecological restoration work informs his art, giving the natural world a voice.