Introduction

Cave archaeology has been increasingly recognised as providing major contributions to understanding Holocene prehistory in Europe. In particular, the presence of human remains from caves supports our understandings of funerary practice from the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Early Bronze Age (Bergsvik & Skeates Reference Bergsvik and Skeates2012; Dowd Reference Dowd2015; Peterson Reference Peterson2019; Schulting Reference Schulting, Grünberg, Gramsch, Larsson, Orschiedt and Meller2016). In particular, the recognition of a substantial number of burials in caves dating from the Early Neolithic and Early Bronze Age present an alternative to the previous focus on monumental burial and provides a broader understanding of funerary practice in these periods.

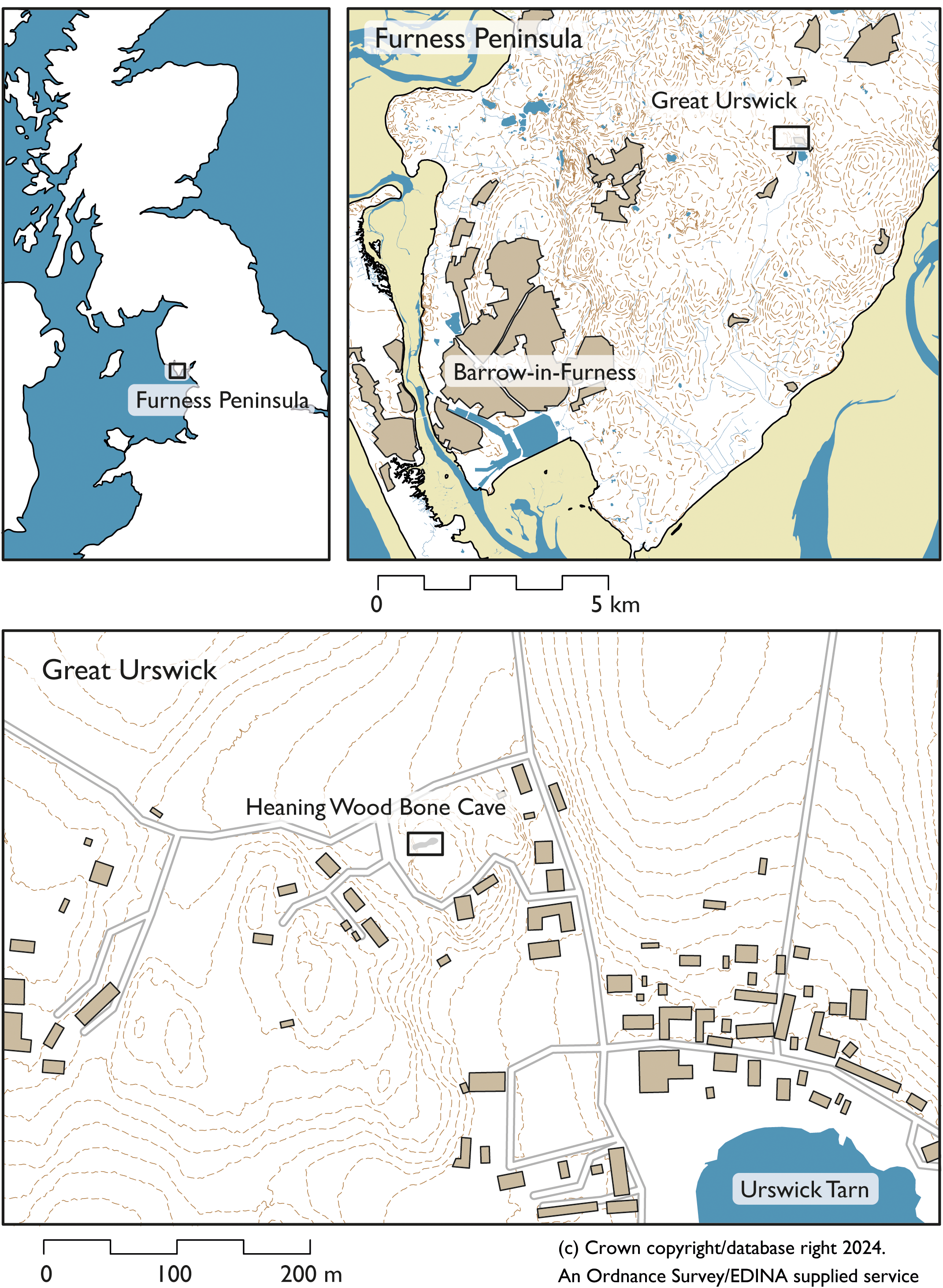

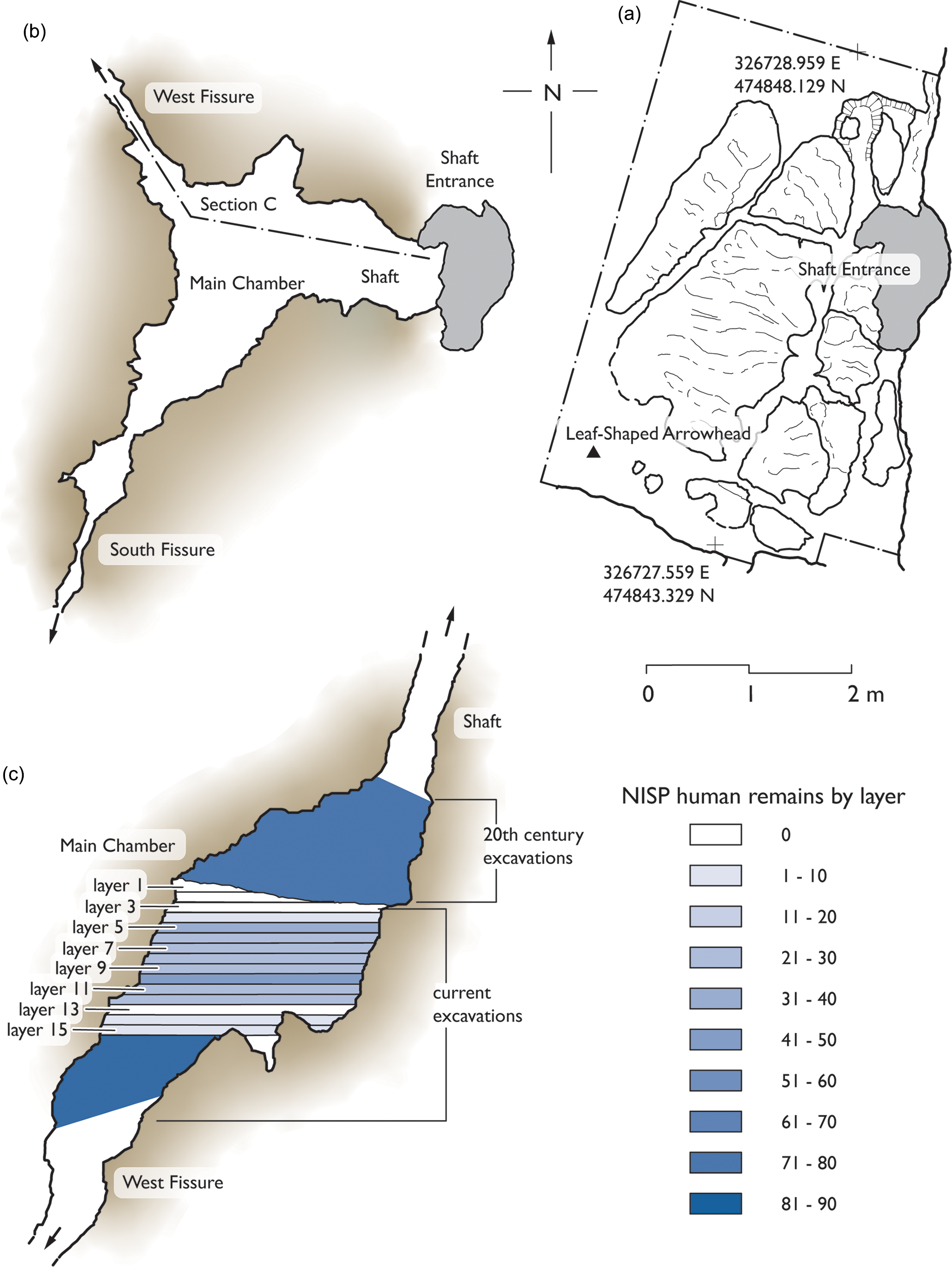

Heaning Wood Bone Cave (NGR SD 2673 7485) is a small cave to the north of the village of Great Urswick on the Furness peninsula, Cumbria, UK (Figure 1). A horizontal entrance leads north-east through an extremely narrow fault-controlled fissure to the main chamber. This is aligned approximately north-east to south-west and is 3.5 m long by 1.5 m wide. The main chamber is around 2.5 m high and on the east side develops into a vertical shaft which ascends a further 5 m to connect with the surface above the cave (Figure 2). The north-west corner of the chamber descends into the narrow vertical west fissure, which produced the deepest material recovered in the current excavation. The system beyond that point has been explored by a caving team but has not produced any further archaeological material. Excavations uncovered human and faunal remains and a small assemblage of material culture from the fill of the vertical shaft, main chamber, and west fissure. This paper describes the results of research on the human remains and material culture; the faunal remains will be reported in a future publication. However, initial assessment has identified the following species in the assemblage: red deer, wild boar, pig, cattle, and sheep/goat, along with a substantial component of small vertebrate remains.

Figure 1. Location of Heaning Wood Bone Cave.

Figure 2. a) plan of the area excavated on the surface around the vertical cave entrance; b) plan of the main chamber; c) section through the main chamber, part of the shaft and the upper part of the west fissure showing the 0.125 m layers recorded during excavation.

The aims of the research were to understand the use of the cave as a place for the deposition of human remains within the wider context of prehistoric human remains from caves in Europe (Bergsvik & Skeates Reference Bergsvik and Skeates2012; Dowd Reference Dowd2015; Peterson Reference Peterson2019) and to investigate the cultural and biological affinities of the people buried at the site. The following objectives were set: to characterise the demography of the human skeletal assemblage from the cave; to provide a comprehensive radiocarbon chronology by attempting to date at least one sample from all the identified individuals; to record and interpret taphonomic traces visible on the remains at a macroscopic scale; to investigate paleogenomic evidence within the assemblage; to investigate evidence from stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen for diet and lifestyle; and to review the existing evidence for the contemporaneous deposition of human remains in caves in Britain, Ireland and north-west Europe.

The name ‘Ossick Lass’, given to the earliest burial, was suggested during the post-excavation process by local archaeologist Martin Stables, who led the excavation of the cave. He was keen that this nationally important discovery should have a distinctive name which reflected the region and the place of discovery. Ossick is the local vernacular pronunciation used for both the villages of Great and Little Urswick, spoken as ‘Gut Ossick’ and ‘Lille Ossick’. Similarly, the term lass, describing a girl or young woman, is used in multiple ways. For example, as a term of affection ‘she’s a good lass’, to describe a family relationship, ‘Joe’s lass’, or, as in this case, a geographical origin. This again is local vernacular. As the first known inhabitant of Urswick, Martin felt that this name would be apt and that locally it would be greatly appreciated.

History of research at the cave

The cave was first explored in 1958 by the Furness Speleological Group who entered the main chamber through the horizontal entrance (Holland Reference Holland1960, 42–3) and removed human and faunal remains, a worked Langdale tuff implement, a sherd of Collared Urn pottery and a bone pin, which had accumulated at the base of the vertical shaft. Further excavations by the Furness Underground Group took place in the spring of 1974 through the horizontal entrance (Peter Burton and Steve Dickinson pers. comm.). They recovered further human and faunal remains and, following this work, the landowner, Mr Peter Redshaw, located the top of the shaft at the surface. He removed the fill of the vertical shaft, encountering human and animal remains throughout the fill and came down onto the bone deposits in the main chamber. At this period the level of the deposits in the cave were marked on the walls in paint (see Figure 3). All material from the 20th century excavations at the site was donated to the Dock Museum, Barrow-in-Furness.

Figure 3. View facing west over the surface of the deposits in the main chamber at the start of the current fieldwork, showing the paint markings made by Mr Redshaw (photo by Martin Stables).

Human and animal remains from this collection were studied by Ian Smith as part of a PhD project at Liverpool John Moores University. Two radiocarbon dates, on cut-marked cattle and pig bones, produced Early Neolithic results, with human remains radiocarbon dated to the Early Bronze Age (Smith Reference Smith2012).

The most recent excavations were carried out by Martin Stables. Sediment was removed in spits of approximately 125 mm depth within the main chamber (Figure 2) and into the west fissure with all deposits sieved through 5 mm mesh sieves to aid recovery of smaller fragments. This work led to the discovery of considerably more human and animal bone, and further prehistoric material culture: including another Collared Urn sherd, lithic artefacts, and five perforated periwinkle shell beads.

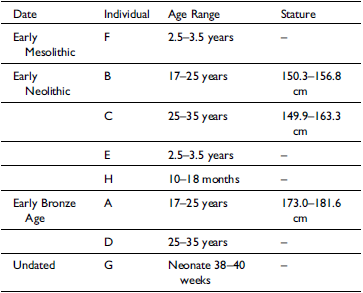

The total number of individual specimens present (NISP) of human bone from all the excavations at Heaning Wood Bone Cave is 423. Osteological analysis of the material indicated a minimum of 8 individuals were present. These were designated as individuals A to H. Summary descriptions of the human remains are provided in Table 2. Full details of the rationale for these assessments are provided in the supplementary online material (Supplementary S1). Seven of these individuals were radiocarbon dated, with neonatal individual G too fragmentary to satisfactorily sample from a single element. In addition, one of the perforated shell beads was sampled.

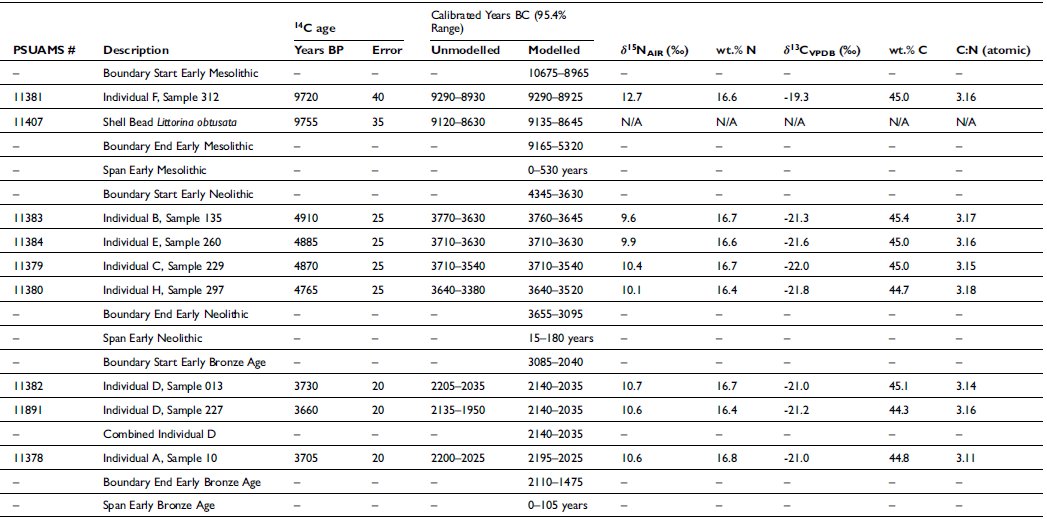

Table 1. Radiocarbon results from Heaning Wood Bone Cave. Bone dates were calibrated using OxCal 4.4 and the IntCal20 calibration curve (Reimer et al. 2020). The shell date was calibrated using the Marine20 calibration curve (Heaton et al. 2020) and a ΔR value of -198 ± 44 obtained from an average of four regional ΔR estimates in the CALIB marine ΔR database (Butler et al. Reference Butler, Scourse, Richardson, Wanamaker, Bryant and Bennell2009; Harkness Reference Harkness, Mook and Waterbolk1983). Boundary commands were used to model the start and end boundaries for the three phases, and the Span command to estimate the longevity of funerary use for each phase at 95.4% confidence

Table 2. Summary demographic data for all individuals from Heaning Wood Bone Cave

Radiocarbon and isotopic evidence

All samples were cleaned and processed to carbon dioxide at the University of Nevada, Reno (UNR) Human Paleoecology and Archaeometry Laboratory, and then sent to the Pennsylvania State University AMS Radiocarbon Laboratory for graphitization and measurement. The shell bead was subjected to a 50% hydrochloric etch before hydrolysing the powdered sample in phosphoric acid under vacuum to produce carbon dioxide. Collagen was extracted from the bone samples and cleaned using a 30 kDa filter. Additional collagen from all eight samples was submitted to the Nevada Stable Isotope Laboratory at UNR for stable carbon and nitrogen isotopic analysis.

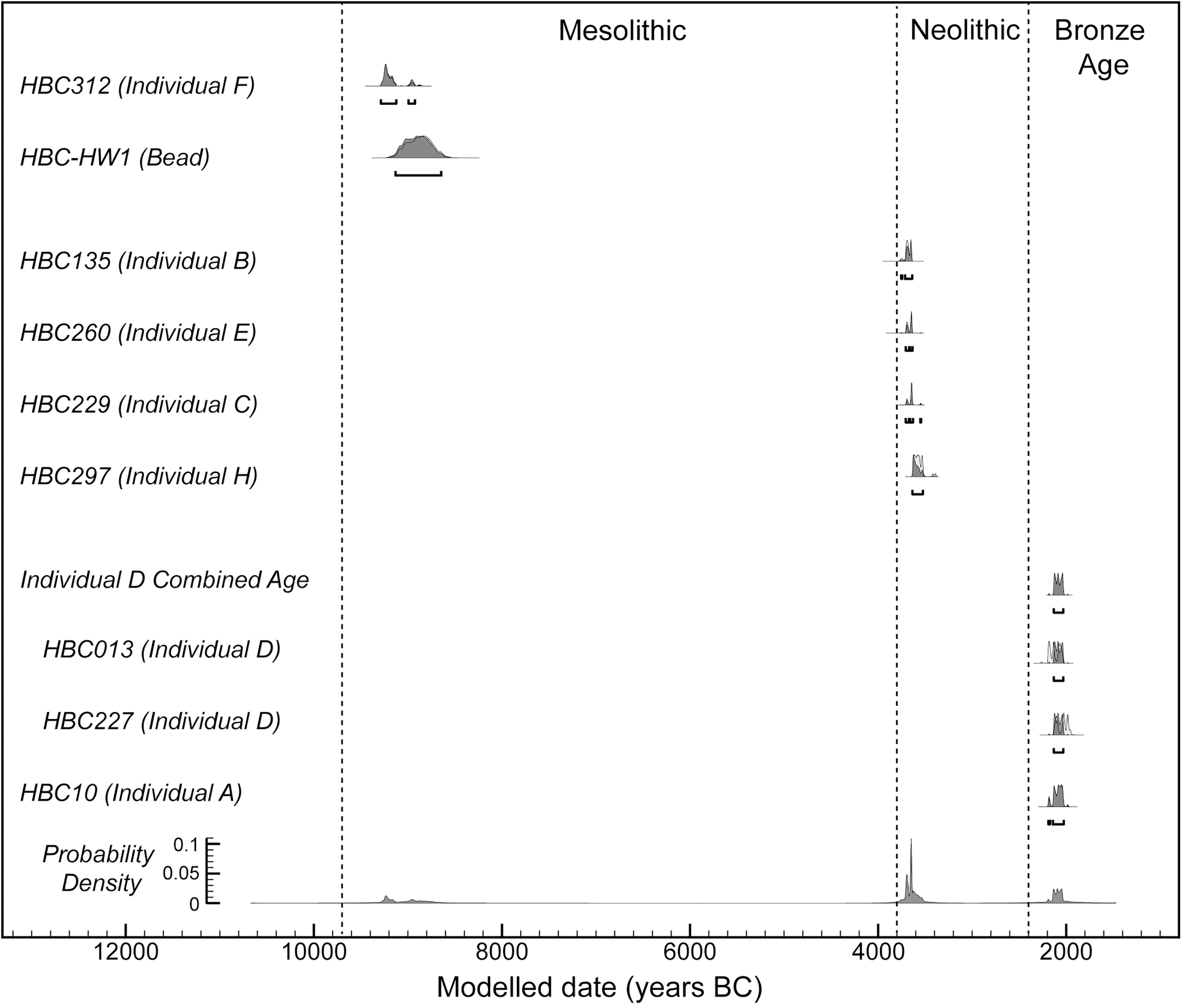

Bone dates were calibrated in OxCal 4.4 using the IntCal20 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer and Grootes2020). The shell date was calibrated using the Marine20 calibration curve (Heaton et al. Reference Heaton and Skinner2020) and a ΔR value of -198 ± 44 obtained from an average of four regional ΔR estimates in the CALIB marine ΔR database (Butler et al. Reference Butler, Scourse, Richardson, Wanamaker, Bryant and Bennell2009; Harkness Reference Harkness, Mook and Waterbolk1983). To generate boundaries for the phases of funerary use, dates were placed within phases as no stratigraphic relationships between them were available (Table 1). Boundary commands were used to model the start and end boundaries for the three phases, and the Span command to estimate the range of use for each phase at 95.4% confidence. The Sum command was used to model a summed probability density curve for funerary use of the cave (Figure 4). This curve was generated from a relatively small number of dates and serves only as a visual device to represent periods of most likely use.

Figure 4. Modelled radiocarbon dates from Heaning Wood Bone Cave. Dates have been placed within phases as no stratigraphic relationships between them are available. OxCal Boundary commands were used to model the start and end boundaries for each of the three phases. The Sum command was used to model a summed probability density curve for funerary use of the cave.

Figure 5. Distribution of fragments from Individual B across the cave.

Radiocarbon dates from Heaning Wood Bone Cave group into three distinct periods (Table 1), corresponding to the Early Mesolithic, Early Neolithic, and Early Bronze Age. Bone collagen from all dated individuals had atomic C:N ratios within the accepted range of 3.1–3.5 (van Klinken Reference Van Klinken1999), suggesting good preservation and therefore allowing us to infer reliable date ranges. The ratios also fall within the more rigorous quality range of 3.1-3.4 proposed by Guiry and Szpak (Reference Guiry and Szpak2021).

Two dates correspond with the Early Mesolithic, Individual F (9290–8925 cal BC; all modelled dates 95.4% probability) and the marine shell bead (9135–8645 cal BC; Table 1; Figure 4). The overlap of these dates and the scarcity of other material in the cave from this time suggests that the bead may have been associated with the burial. Furthermore, Individual F has elevated δ13C (-19.3‰) and δ15N (12.7‰) compared to the other seven individuals identified. This could be for two possible reasons: (1) since this was a young child (Table 2), elevated values may have been the residual product of breastfeeding early in life (Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Fuller, Harris and Hedges2006); or (2) they may have had a non-negligible marine component to their diet. If the latter, that would indicate that the date should be slightly younger than the given date, overlapping more with the calibrated range for the bead. The estimated span of use of the cave in this period is potentially relatively long, between 0–530 years, because there are only two dates associated with that period and there is no other data to constrain that use. Therefore, this suggests that the Early Mesolithic activity was a single event conservatively described at 95.4% confidence by the date from the bead (9135–8645 cal BC).

Four dates correspond with the Early Neolithic, Individuals B (3760–3645 cal BC), E (3710–3630 cal BC), C (3710–3540 cal BC), and H (3640–3520 cal BC), suggesting that at this time the cave was a focus for burial. All four dates overlap at the 95.4% range, therefore interment during the Early Neolithic probably occurred over a short period of time, estimated as between 15 and 180 years. However, all four individuals were unlikely to have died and been buried at the same time (i.e., within less than 15 years) at 95.4% confidence.

Finally, three dates correspond with the Early Bronze Age. Two are from Individual D, which when combined give a date of 2140–2035 cal BC. The calibrated range for Individual A is 2195–2025 cal BC. Overall, the estimated span of use is 0–105 years, indicating that they may have been interred at the same time. δ13C and δ15N measurements of the six burials from the Early Neolithic and Early Bronze Age suggest a consistent diet between the two periods and among the different individuals. They are likely to have had less of a marine contribution than the Early Mesolithic individual.

Taphonomy of the human remains

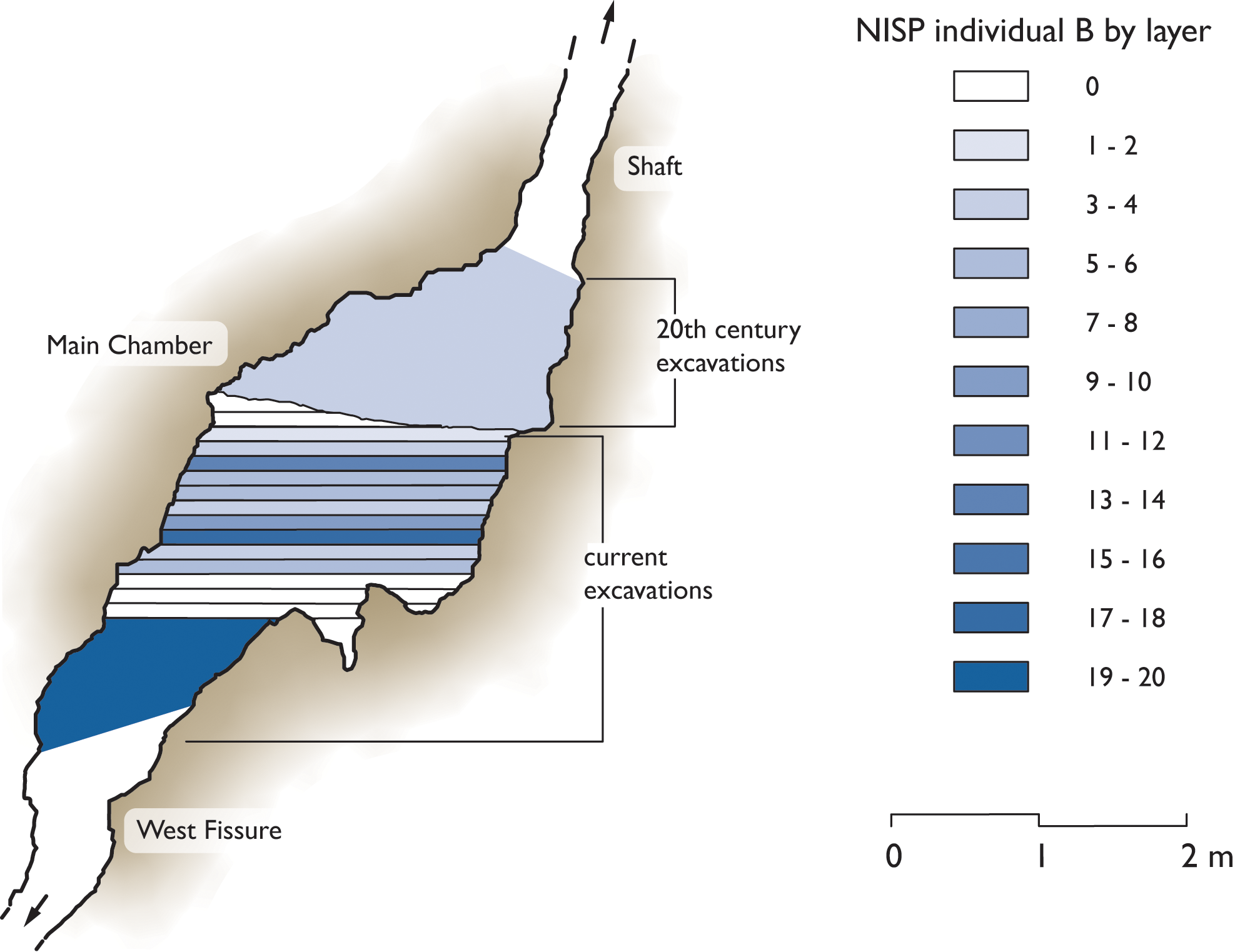

Taphonomic assessments were conducted using macroscopic observations and a Geographical Information System (QGIS) was used to analyse the distribution and frequency of taphonomic changes following the methodology outlined in Warburton (Reference Warburton2023). Spatial information of the fragments was limited to layers of approximately 0.125 m (Figure 2), distributions of elements and taphonomic traces were also analysed (Warburton Reference Warburton2023). The following section outlines key taphonomic findings by period.

Early Mesolithic

Analysis of Individual F was limited by the low number of fragments. All fragments were cranial and were located from Layer 12 down (see Figure 2). The distribution of fragments in these lower layers is consistent with the early date of Individual F. Three fragments were located in the west fissure: a molar tooth crown, a portion of maxilla and the left zygomatic. There was an absence of root embedding, tufa deposits, vertebrate (such as rodent or carnivore gnawing) and invertebrate (such as mollusc or insect) activity for all fragments. There was a single area of mosaic cracking consistent with weathering processes to the left mandible, recovered from Layer 12. All other taphonomy was similar to the rest of the assemblage and was consistent with primary and extended burial in a cave environment. There was no evidence of exposure to mechanisms other than those natural processes occurring within the cave.

Early Neolithic

The destruction and fracturing seen in the Early Neolithic adults and sub-adults was consistent with dry, post-mortem damage, reflecting the destructive processes within a cave environment. There was nothing to indicate perimortem trauma consistent with falling and the element representation for the adults (Individuals B and C) was consistent with primary, whole-body burial. Individual E (2.5–3.5 years) was represented by cranial material and clavicles, and Individual H (10–18 months) was represented only by cranial fragments. The presence of the clavicles which have been assigned by age to Individual E, along with a lack of evidence for exposure at a different burial site make it unlikely that these are curated, cranial deposits. The taphonomy was consistent with the other Early Neolithic depositions and it is considered that element representation is due to loss and destruction within the cave environment.

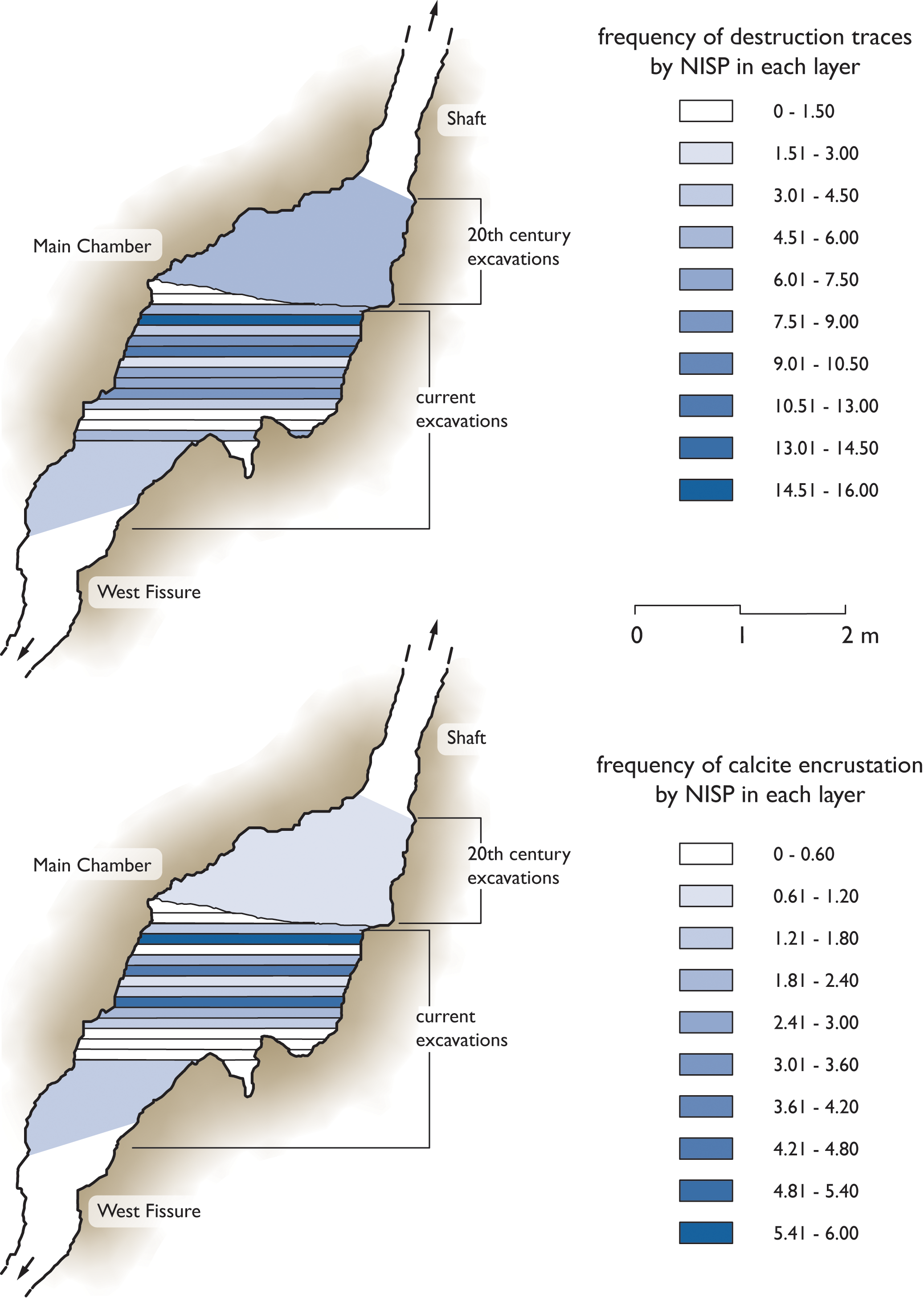

Most fragments had staining consistent with the soils found at Heaning Wood and tufa deposits were limited to flakes or small deposits. The exception to this was the right humerus of Individual B which exhibited a large lump of calcite adhered to the midshaft. This was recovered from Layer 10.

The taphonomic changes to the individuals dated to the Early Neolithic provided no clear evidence of burial position or depositional narrative. While there were some areas of potential increased exposure, the taphonomy was generally homogenous, and consistent with deposition in a cave environment. Analysis of the distribution of taphonomic processes show these were occurring throughout the cave. It is possible that this is a result of fragments moving within the system, however the geology of Heaning Wood suggests that agents of taphonomy are present in all areas. Analysis shows some layers where mechanisms may be more prolific, such as calcite deposits in Layer 10 and increased destruction in Layer 4. The layers described for Heaning Wood are not contexts and should not considered to be fixed surfaces, however, concentrations of some fragments may suggest that Layers 4 and 5 mark the depth of the surface at the time Individual B was deposited. Overall, the modifications occurring to the Early Neolithic individuals are consistent with an extended burial within a cave environment, with episodes of sediment movement and infilling.

Early Bronze Age

All fragments associated to the Early Bronze Age individuals (A and D) had some level of destruction, with most described as ‘exposure of trabecular bone’. There did not appear to be any significant bias to the spread of destruction, either at a body level or spatially. The damage and distribution reflect sediment abrasion common in a cave environment (Fernández-Jalvo & Andrews Reference Fernández-Jalvo and Andrews2016).

Nine specimens from Individual A exhibited crush damage indicative of peri-mortem destruction, with most of the crushing occurring on posterior surfaces. This may be indicative of body position, with the back of the body exposed to falling sediment. Posterior surfaces for Individual D had significantly more cracking than anterior (28.29% compared to 2.63%). This may be indicative of the posterior surface of bones having greater exposure to mechanisms, such as wet/dry cycling, within the cave. A portion of mandible (HBC421) had more cracking than any other fragment. The mandible was recovered from the top area of the cave, and the increased weathering may suggest that it had greater exposure.

Both Individuals A and D had fragments with white deposits, consistent with calcium carbonate. There were also a few deposits that were brown, soil-like build ups. This is consistent with the environment of Heaning Wood cave, which is predominantly an orange-brown silty clay, with some evidence of calcite formation. Distributions of calcite showed a concentration in Layers 4 and 10. This suggests that calcite formation may have been more active in these layers and reflects similar findings for Individual B.

All invertebrate activity was found on bones located in the top area of the cave, namely Individuals A and D. The concentration of invertebrate activity remains in the top area even when the whole assemblage is combined. Terrell-Nield and Macdonald (Reference Terrell-Nield and Macdonald1997) conducted experiments on the effect of decomposing animals on UK cave invertebrates. While they document invertebrate activity at all levels of the cave, including areas beyond light reach, the deeper parts of the cave saw insects playing ‘a lesser role’ (Terrell-Nield & Macdonald Reference Terrell-Nield and Macdonald1997, 62). The variability of temperature and air flow towards cave entrances impacted the type of invertebrates seen to colonise carcasses. It is possible that the patterns seen here are due to varying species of invertebrates accessing remains in different layers. It is also possible that the fragments with invertebrate activity towards the lower layers of the cave are a result of previously modified fragments moving within the cave system. It is clear from the lack of evidence for vertebrate activity that there was limited access to even the upper layers of the deposit.

All taphonomic changes to Individuals A and D were consistent with a primary, whole-body burial, with an extended period in a cave environment. The taphonomic changes to the individuals dated to the Early Bronze Age provided no clear evidence of burial position or deposition narrative. There were some areas, such as weathering and deposits that may indicate differential exposure. The taphonomy was, however, generally homogenous, and consistent with deposition in a cave environment.

The distribution of fragments for both Individuals A and D is consistent with smaller elements such as the hands and feet being more widely dispersed across the cave. Cranial elements and long bones were all located toward the top area of the cave. This is consistent with the date of deposition.

Other

Fragments from Individual G were recovered from several layers, including the top area and west fissure. The presence of fragments in the upper layers may indicate a later deposition, however fragments associated to Early Neolithic individuals were also found in the upper layers of the cave. Taphonomy and bone representation indices suggest a whole-body, primary burial.

The patterns of dispersal and taphonomy are consistent with the other burials at Heaning Wood. The representation of elements from all groups, except for hands, feet, and patellae, is different from the other infants in the assemblage. While both clavicles for Individual E were recovered, the infants were otherwise only represented by cranial fragments. Individual G demonstrates that the recovery of juvenile remains was excellent.

Taphonomic summary

There were some layers with higher frequencies of modifications that suggest concentration of taphonomic agents at particular locations. Layer 4 had higher incidences of destruction per fragment and Layer 10 had increased calcite deposits (Figure 6). These were seen on fragments from burials across different periods.

Figure 6. Layers with higher frequencies of taphonomic modifications.

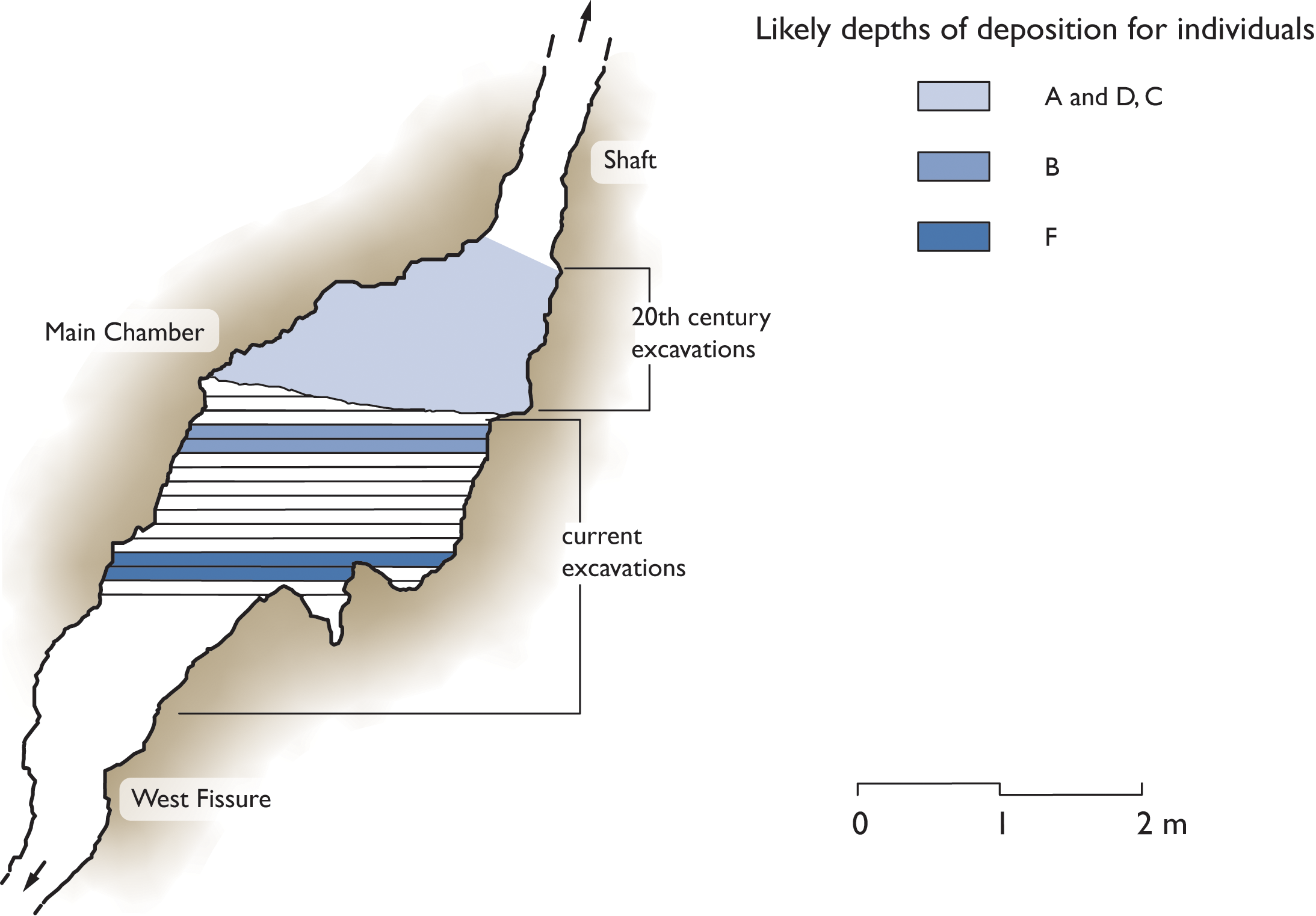

From the spatial and taphonomic analysis of the Heaning Wood assemblage it was possible to identify a possible sequence of deposition for the adult remains (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Sequence of depositions for Individuals A–D and Individual F. Showing the possible existence of a stable horizon for deposition around layer 4 or 5 in the Early Neolithic.

Fragments from the Bronze Age adults (Individuals A and D) were concentrated in the top area, which is consistent with their later deposition. Fragments from Individual C (Early Neolithic) were recovered from the top area but were also distributed further down the cave. While there is some overlap in the date range for the Early Neolithic adults, Individual C is likely to be a later deposition, which would explain the fragments towards the top of accumulation. Concentration of fragments along with higher frequencies of destruction suggest a possible point of deposition towards Layers 4 and 5 for Individual B (Figure 5).

Palaeogenomic evidence

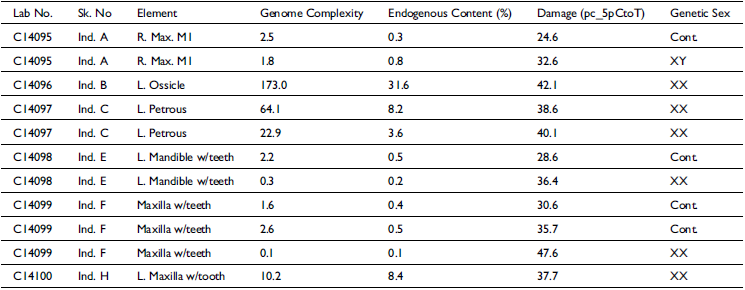

Six human teeth and bone fragments from Heaning Wood Bone Cave were sampled for DNA analysis, following the methodology outlined (Supplementary S2). Preliminary sequencing data generated from the samples allowed for the assessment of DNA preservation and genetic sex (Table 3). Multiple results for individuals represent different micro-fractions of bone or dentine powder. Metrics of DNA preservation suggested that preservation was generally poor. Endogenous DNA content was above 10% in only one sample (Individual B) and above 1% in only two others (Individuals C and H). The samples from Individuals B and C were the only two to come from auditory ossicles/temporal bones, confirming that these elements more often show higher levels of DNA preservation compared to teeth (Gamba et al. Reference Gamba and Pinhasi2014, fig. 1).

Table 3. Summary of the preliminary screening sequencing of samples from Heaning Wood Cave. Genome Complexity reflects proportions of unique DNA sequences within a sample. Endogenous Content is the proportion of DNA sequences which align with the human genome. Damage refers to the proportion of sequencing reads exhibiting ancient DNA-characteristic deamination patterns on the 5’ end, thereby authenticating human sequences as genuinely ancient. We would expect damage to be >10% for genuinely ancient DNA. Assessment of genetic sex/contamination was done via the method outlined in Anastasiadou et al. (2024)

Unfortunately, the DNA from the Early Mesolithic Individual F was particularly poorly preserved. Two of the samples produced an uncertain genetic sex estimate because of possible signals of contamination (Anastasiadou et al. Reference Anastasiadou and Skoglund2024). However, a third sample, while still poorly preserved, produced a reliable sex estimate of female (XX). Genetic sex estimates for the other five skeletons are reliable as defined by Anastasiadou et al. (Reference Anastasiadou and Skoglund2024) and indicate that four out of five were genetic females. Further sequencing of some of these DNA libraries will lead to a more comprehensive assessment of genetic ancestry, close genetic relationships and evidence for infectious disease.

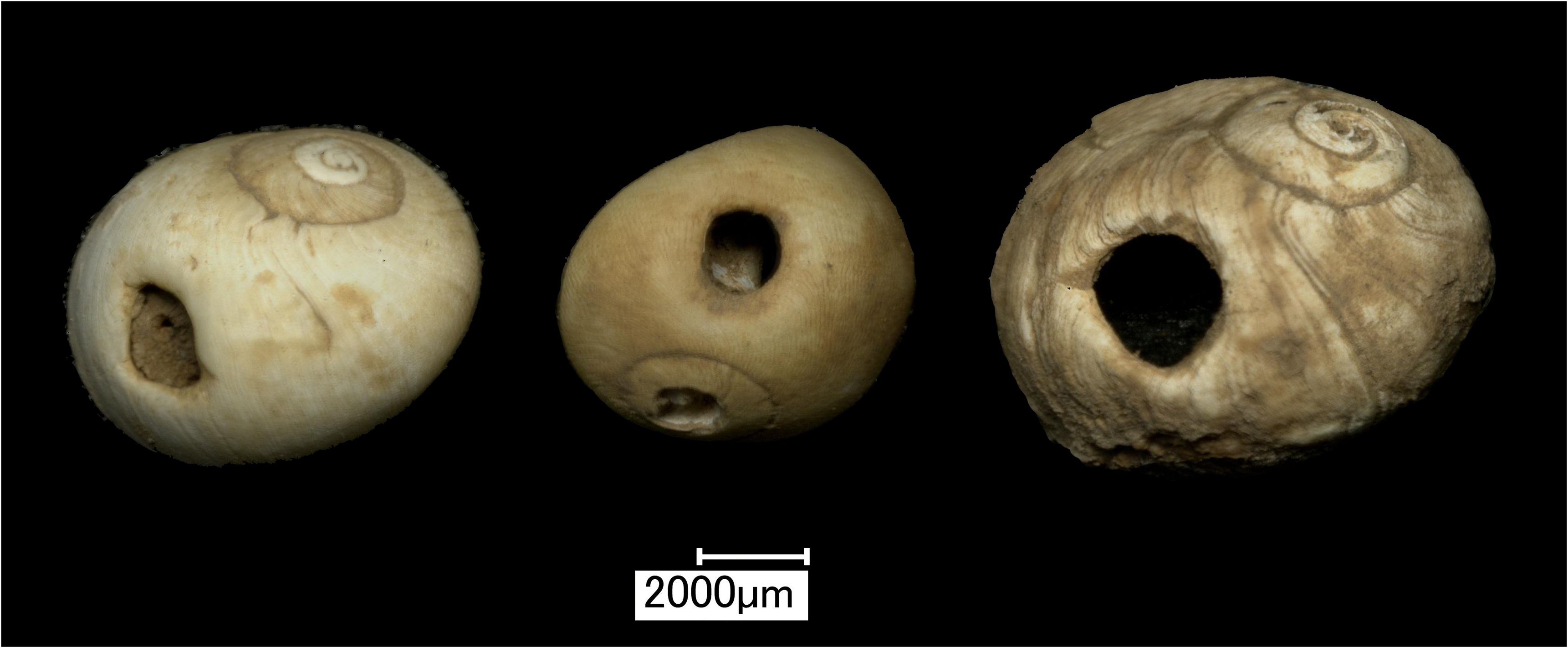

Associated material culture

The associated material culture falls into three phases linked to the absolute chronology established above. The earliest are five perforated periwinkle shell beads, one of which has been directly dated to the same Early Mesolithic phase as Individual F. The Heaning Wood beads are all single-perforated flat periwinkle (Littorina obtusata) shells (Figure 8). Mesolithic shell bead finds in Britain and north-west Europe have been reviewed by Saville (Reference Saville and Saville2010, 200–2) and Barton and Roberts (Reference Barton, Roberts, Ashton and Harris2015). Comparable examples from six other British sites have been ascribed a later Mesolithic date (Barton & Roberts Reference Barton, Roberts, Ashton and Harris2015, table 1). Perforated periwinkle beads are also recorded from known Early Mesolithic burial sites at Aveline’s Hole (Schulting Reference Schulting2005, 181) and Gough’s New Cave, Somerset (Jacobi Reference Jacobi1985, 108). However, in both cases there are multiple phases of activity at each site, and the surviving records are not precise enough to directly link the shell beads to the burials.

Figure 8. Perforated shell beads from Heaning Wood Bone Cave.

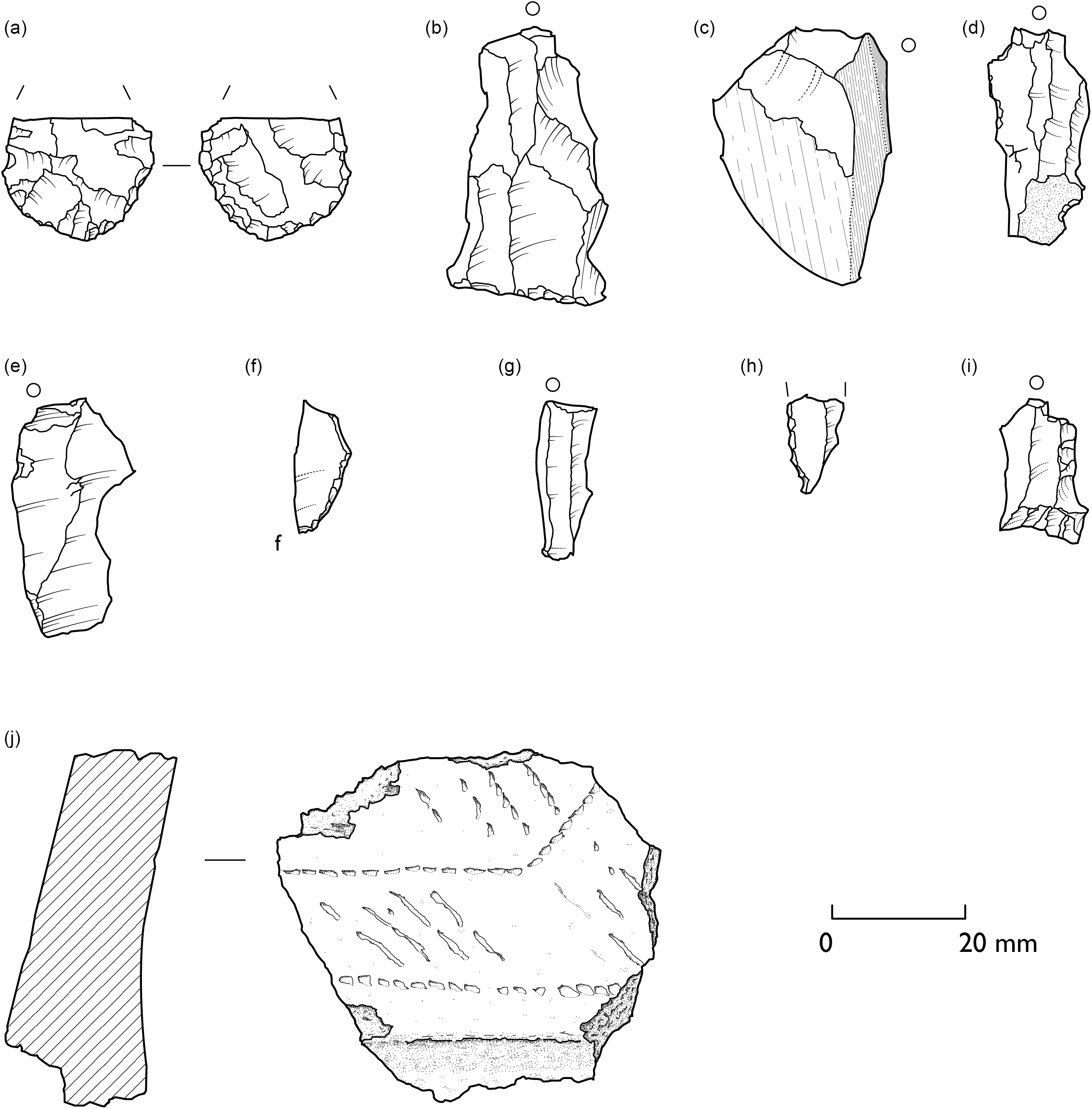

Nineteen pieces of worked stone came from within the cave and the surface around the entrance (Figure 9). There is a single piece of quartz crystal, three flakes of Langdale tuff, six pieces of chert, and nine pieces of flint, all of which are heavily patinated. Mesolithic material is represented by a possible obliquely truncated chert microlith (Jacobi Reference Jacobi and Drewett1978, 16), a chert bladelet, and a flint flake with two burin removals. The bladelet and possible microlith were both recovered from the lowest part of the excavated deposits, in the west fissure. Diagnostically Early Neolithic material includes one of the flakes of Langdale tuff, with traces of the polished surface and side facets of a typical Cumbrian Group VI axe (Manby Reference Manby and Cummins1979, 65), and the lower half of a leaf-shaped arrowhead. The arrowhead was broken in antiquity as the patination extends over the whole of the broken surface. It was discovered in a disturbed context on the surface, close to the vertical entrance to the cave (Figure 2).

Figure 9. Prehistoric material culture from Heaning Wood Bone Cave: a) partial leaf-shaped arrowhead from the surface to the north-west of the shaft entrance, b) flint flake from Layer 11, polished Group VI axe flake (sieve find), d) chert blade (sieve find), e) flint blade from the west fissure, f) chert microlith from Layer 8, g) chert blade from the west fissure, h) broken chert blade from the west fissure, i) chert flake (sieve find), j) Collared Urn sherd (sieve find).

The final phase of material culture from the cave is represented by a single sherd from the collar of an Early Bronze Age Collared Urn. Comparison with the fragment reported from the earlier excavations shows that both sherds are likely to be from the same vessel, although they do not join. This was described and illustrated by Barnes (Reference Barnes1970, 3–5) and placed by Longworth (Reference Longworth1984, 170) within the broader north-western style.

Interpretation

Heaning Wood Bone Cave provides evidence of the use of caves for funerary ritual in three distinct periods: the Early Mesolithic, the Early Neolithic and the Early Bronze Age. Caves and human remains were joined in action as part of funerary practice which can be paralleled at other cave sites in Britain and in the karst landscapes of Europe more widely (Bergsvik & Skeates Reference Bergsvik and Skeates2012; Dowd Reference Dowd2015; Peterson Reference Peterson2019; Schulting Reference Schulting, Grünberg, Gramsch, Larsson, Orschiedt and Meller2016). The discussion of funerary practice below follows the terminology for cave burials established in Peterson (Reference Peterson2019, 56-9) and builds on work by Knüsel (Reference Knüsel2014) and Weiss-Krejci (Reference Weiss-Krejci2012). A primary burial is one in which one or more individuals are interred and left undisturbed in the original burial location. A secondary burial refers to burials which incorporate a substantial intermediary period (Knüsel Reference Knüsel2014, 49–50) with the body, or parts of the body, being moved from one location to another during the intermediary period. Successive inhumation refers to burials which apparently incorporate an intermediary period leading to bodily disarticulation and co-mingling of remains, but the corpses have been left in their original locations and this co-mingling is a result of the successive addition of subsequent bodies (Weiss-Krejci Reference Weiss-Krejci2012, 125). A multi-stage burial is one where it is likely there was an intermediary period with evidence of co-mingling and disarticulation, but the evidence is not sufficiently clear to allow a distinction between secondary burial or successive inhumation.

Early Mesolithic Burial

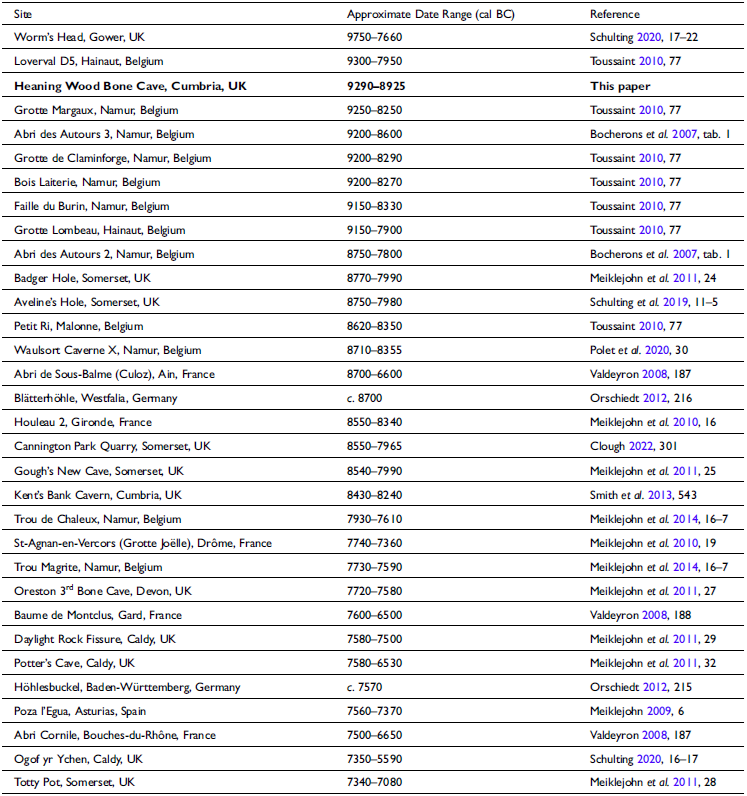

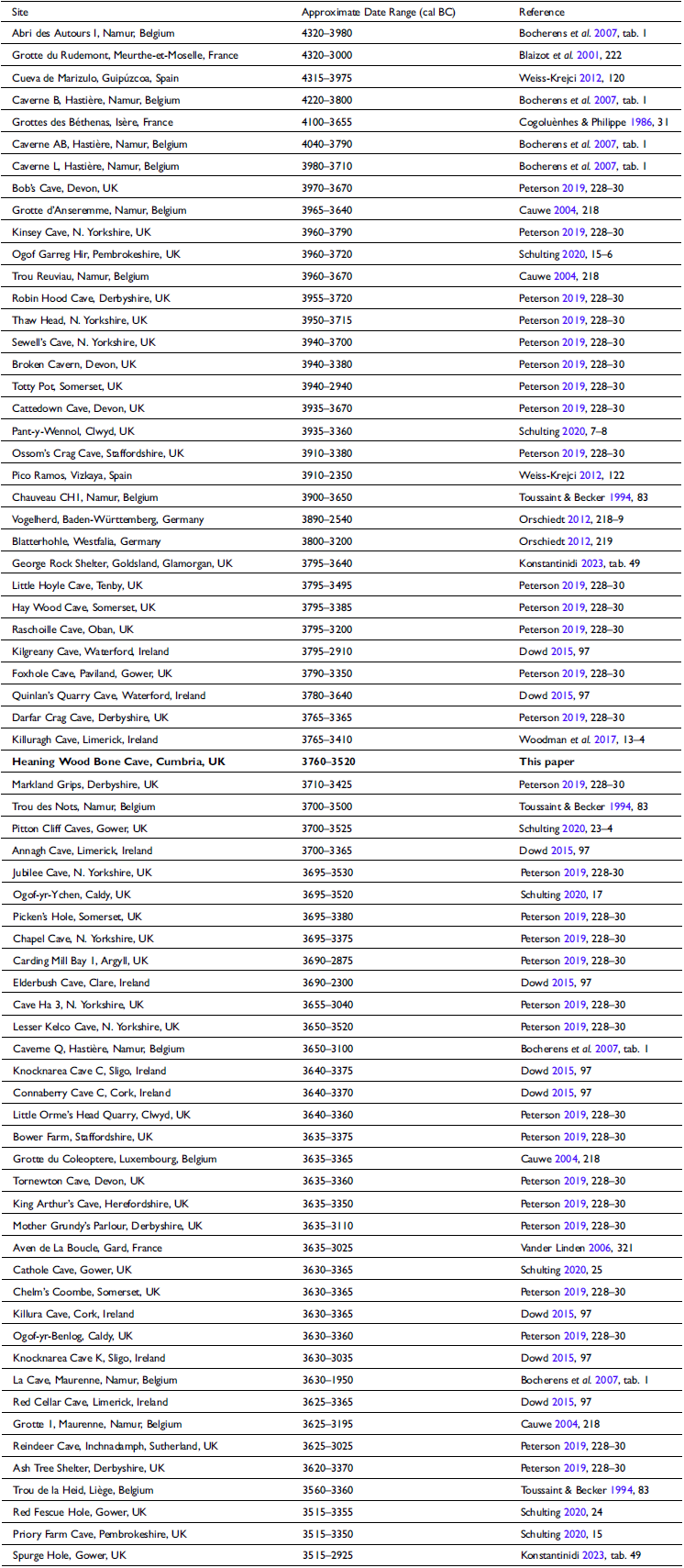

Deliberate deposition of human remains in caves during the early part of the Mesolithic is attested at nine other directly dated sites in the UK (Meiklejohn et al. Reference Meiklejohn, Chamberlain and Schulting2011, 22–34: Smith et al. Reference Smith, Wilkinson and O’Regan2013). These sites form part of a wider group within north-western Europe, including burials in Belgium, France, western Germany and northern Spain (see Table 4). The Heaning Wood burial belongs with the very earliest of these burials, from seven caves in the Meuse river basin, Belgium (Bocherons et al. Reference Bocherens, Polet and Toussaint2007, table 1) alongside the remains from Worm’s Head on the Gower, south Wales (Schulting Reference Schulting2020, 22).

Table 4. Radiocarbon dated Early Mesolithic human remains from caves in north-west Europe where some part of the calibrated date range for burial activity at the cave falls into the period pre-dating 7300 BC. Date ranges and calibrations are those presented in the cited publications. Two sites, Faille du Burin and Grotte de Claminforge, have some published dates which would be regarded as unreliable owing to ultrafiltration problems (Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Higham, Bowles and Hedges2004), in these cases only unaffected dates have been used for the date range

The precise nature of Early Mesolithic funerary practice at Heaning Wood itself is unclear owing to the small number of fragments surviving. However, the results of the taphonomic analysis reported above suggest that the body was deposited whole shortly after death and it is likely that it was accompanied by the shell beads. Of the other early sites discussed above, the Worm’s Head material was discovered co-mingled and cemented in breccia deposits in the cave floor and from a layer above this floor (Schulting Reference Schulting2020, 18). Evidence for funerary practice in the Belgian caves has been reviewed by Toussaint (Reference Toussaint2010). He considered that there was a variety of practices at this date including secondary burial (at Grotte Margaux), primary burial (at Abri des Autours 3), but that at least three caves (Loverval D5, Grotte du Bois Laiterie, and Grotte Lombeau) were likely to have been used for successive inhumations. Early Mesolithic material culture is rare from these caves, except for some worked flint from Grotte Lombeau.

The evidence can also be compared with the wider group of sites using for burial during the 8th millennium BC (see Table 4). The closest of these is Kent’s Bank Cavern (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Wilkinson and O’Regan2013), which is 12.6 km due east of Heaning Wood. From the limited taphonomic information surviving, the three individuals from Kent’s Bank Cavern are best described as multi-stage burials. Parallels for the Heaning Wood burial within this wider group of sites include evidence for successive inhumation from Abri des Autours 2 (Toussaint Reference Toussaint2010, 73), Waulsort Caverne X (Polet et al. Reference Polet, Drucker, Glas, Sabaux, Goffette, Samsel, Jadin, Warmenbol and Villotte2020, 33–5) and from the substantial cemetery at Aveline’s Hole (Schulting Reference Schulting2005, 243–4). Toussaint (Reference Toussaint2010, 78) notes the general lack of material culture associated with burials of this date in Belgium. In Britain, as discussed above, perforated periwinkle shell beads were discovered at Aveline’s Hole and Gough’s New Cave.

Although the Heaning Wood remains are early in the sequence of dated burials in north-western Europe, the ‘Ossick Lass’ is not anomalously early within the wider context of the post-glacial re-occupation of northern Britain. The modelled dates for the introduction of Star Carr type microliths, almost exclusively from sites in northern England, show that this earliest phase of the Mesolithic begins in the mid to late 9th millennium BC (Conneller et al. Reference Conneller, Bayliss, Milner and Taylor2016). Perforated periwinkle shells can now be shown to be directly dated to the Early Mesolithic, supporting the associations previously recorded at Aveline’s Hole and Gough’s New Cave (see above). In each of these cases beads appear to be associated with deliberate burial. In view of the small size and extreme fragility of these beads it is highly likely that the surviving examples are a small fraction of those which were originally deposited. The presence of apparent grave goods associated with the human remains considerably strengthens the argument, made from the taphonomic evidence, that the ‘Ossick Lass’ is a deliberate burial.

Early Neolithic Burial

In north-western Europe there is evidence for a considerable number of cave burials dating to the early part of the 4th millennium BC (see Table 5). In general, in both Belgium and northern France, cave burial is primarily a Later Neolithic phenomenon (Beyneix Reference Beyneix2012, 225–6; Cauwe Reference Cauwe2004, 217–9). The development of cave burial in the British and Irish Early Neolithic is therefore part of a Europe-wide pattern of the increasing deposition of human remains in caves during the first part of the fourth millennium BC. If we treat this burial practice as a single cultural phenomenon which encompasses an area from western Germany to the west of Ireland, then the earliest manifestations of this practice belong to the Michelsberg culture at sites such as Abri des Autours in Belgium (Polet & Cauwe Reference Polet and Cauwe2007, 74–84) and Grotte de Rudemont in France (Blaizot et al. Reference Blaizot, Boës, Lalaï, Le Meur and Maigrot2001). However, the majority of sites in this whole area date to the centuries after 3900 BC in the Seine-Oise-Marne Late Neolithic (in Belgium and northern France) or the contemporaneous Early Neolithic period (in Ireland and Britain). Reviews of the evidence from the three areas with the most evidence, Ireland (Dowd Reference Dowd2015), Britain (Peterson Reference Peterson2019) and Belgium (Cauwe Reference Cauwe2004), have shown that there are examples of caves which are used for a variety of different funerary rites. These include secondary burial and primary burial but, where good taphonomic evidence exists, the majority rite over the whole area is successive inhumation. The taphonomic evidence for the Heaning Wood Early Neolithic human remains discussed above suggests that this site provides another example of the successive inhumation of bodies in caves (Peterson Reference Peterson2019, 142-50).

Table 5. Radiocarbon dated human remains from caves in north-west Europe where some part of the calibrated date range for burial activity at the cave falls into the period between 4000 and 3500 BC. Date ranges, calibrations or estimations are those presented in the cited publications. There are also four sites in south-western France (Beyneix Reference Beyneix2012, 225) which are likely to belong to the Middle Neolithic period (4500–3700 BC) but which do not have any direct radiocarbon dating of human remains and have therefore not been included in this table

Previously known examples of this wider 4th millennium burial practice come from the nearby limestone regions of western Yorkshire, where there is a considerable cluster of caves with remains radiocarbon dated to the Early Neolithic (see Table 5). Cumbria had been identified as an area where there was an anomalous absence of Early Neolithic cave burials (Peterson Reference Peterson2019, 7–8) however, this is clearly no longer the case. Cave burial practice in the Early Neolithic is likely to represent a specific example of a wider set of burial practices. These burial practices are also found in other natural places and, of course, within monuments. It has been suggested (Peterson Reference Peterson2019, 191-6) that a distinctive characteristic of cave burial practice at this date is its extended temporality. Interestingly, Heaning Wood, along with Hay Wood Cave in Somerset (Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Chapman and Chapman2013), appears to be a rare example of a cave with ‘quick’ funerary temporality. The modelled duration for burial practice of 15–180 years is entirely comparable with Early Neolithic burial from monuments, for example 15–75 years at Hazelton North, Gloucestershire (Meadows et al. Reference Meadows, Barclay and Bayliss2007, 54), or 45–145 years at Ascott-under-Wychwood, Oxfordshire (Bayliss et al. Reference Bayliss, Benson, Galer, Humphrey, McFadyen and Whittle2007, 40).

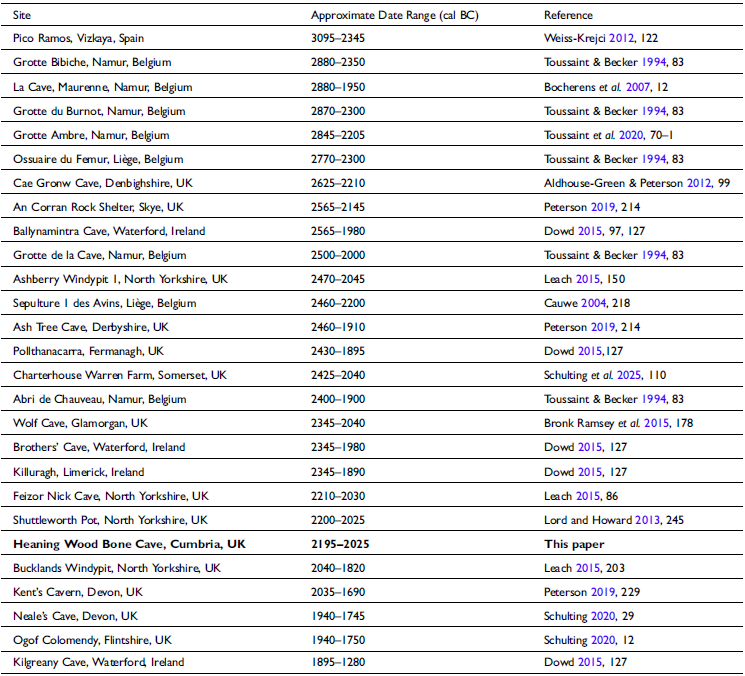

Early Bronze Age burial

There has been less published discussion of Early Bronze Age mortuary practice in caves than for the two earlier periods. However, reviewing the published radiocarbon dates on caves for north-west Europe (see Table 6), shows that there are a significant number of sites used for burial at this date. The geographical spread of these caves is similar to those used for burial in earlier periods of prehistory, with particular concentrations in Belgium, Britain and Ireland. In these areas the Early Bronze Age funerary use of caves appears to be a continuation of practices which were first established in the later Neolithic. In particular, as is the case at Heaning Wood, the funerary rite in the majority of cases in the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age appears to have been successive inhumation. The Irish site of Kilgreany Cave (Dowd Reference Dowd2015, 101, 131–2), for example, includes more fragmentary Early Bronze Age material at a site with evidence for successive inhumation into the later part of the Neolithic. In general, in both Britain and Belgium (Cauwe Reference Cauwe2004, 219–20; Peterson Reference Peterson2019, 168–70) later Neolithic funerary practices in caves emphasise a separateness from the world of the living, either through distance into the cave system or through the creation of physical barriers such as drystone walling within the cave.

Table 6. Radiocarbon dated human remains from caves in north-west Europe where some part of the calibrated date range for burial activity at the cave falls into the period between 2400 and 1800 BC. Date ranges, calibrations or estimations are those presented in the cited publications. There are also at least seven sites in France (Baills & Chaddaoui Reference Baills and Chaddaoui1996; Beyneix Reference Beyneix2012, 231; Laporte et al. Reference Laporte, Jallot and Sohn2011, 315) which are likely to belong this period, but which do not have any direct radiocarbon dating of human remains and have therefore not been included in this table

Some of the best studied Early Bronze Age examples from Britain are specifically associated with Beaker burial practice. At Ashberry Windypit 1 in North Yorkshire, Leach (Reference Leach2015, 150–1) suggests that the dated human remains were parts of individual Beaker-associated burials higher up the system which had become disturbed. The recent re-analysis of the Beaker-associated human remains from Charterhouse Warren Farm, Somerset (Schulting et al. Reference Schulting, Fernández-Crespo, Ordoño, Brock, Kellow, Snoeck, Cartwright, Walker, Loe and Audsley2025) presents a completely contrasting picture. Here, a large number of individuals were deposited following a violent massacre alongside faunal remains and what was probably a complete Beaker. There are also large numbers of cave burials from this period in Belgium (Table 6) and, despite the lack of directly dated examples, in France. Vander Linden (Reference Vander Linden2006, 324) suggests that cave burial was common in southern France and appears to have been an integral part of wider mortuary practice.

However, both the material culture associations and the radiocarbon dates would suggest that the Heaning Wood Early Bronze Age burials are later than the Beaker period. In this case, sites such as Kilgreany (cited above) and Ogof Colomendy, Flintshire (Peterson Reference Peterson2019, 168; Schulting Reference Schulting2020, 12), where there are both later Neolithic and Early Bronze Age dates from the same caves, suggest that we are seeing a continuation of an established Late Neolithic practice. Interestingly these later dates are even less common outside of Britain and Ireland (Table 6).

Conclusions

Overall, Heaning Wood and the ‘Ossick Lass’ provide important evidence which extends our knowledge of the human use of caves in Holocene prehistory. Northern and western England can now be seen to be part of a wider European tradition of the deposition of human remains and associated artefacts in caves in the Early Mesolithic, Early Neolithic and Early Bronze Age. In all three periods there are common practices around death and caves which cover the whole of northern and western Europe. It is also significant that in all three periods there will have been substantial population movement into Britain just prior to the likely time of burial. The Early Mesolithic burial would have taken place during the earliest re-occupation of northern Britian (Conneller et al. Reference Conneller, Bayliss, Milner and Taylor2016). Brace and colleagues (Reference Brace and Barnes2019) have established that there was a substantial population movement into Britain at the beginning of the Early Neolithic. Similarly, aDNA evidence points to another substantial population movement in the centuries prior to the Early Bronze Age burials at Heaning Wood (Olalde et al. Reference Olalde and Reich2018).

This has important implications for the documented continuity of practice between Neolithic and Early Bronze Age burial activity in caves, which is evident at Heaning Wood but also at other Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age sites (Peterson Reference Peterson2019, 182–3). Here we have caves being used in broadly similar ways by populations who were probably not directly ancestral to one another. The key to understanding this apparent paradox lies in the breadth of the wider north-western European cave burial tradition as documented above. The complexities of human mobility and the widespread nature of this tradition mean that even though burials were being carried out by new populations those populations were drawing on a very widely understood way of responding to death which involved the successive inhumation of the dead in natural underground spaces.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the following people. Mrs Lisbeth Redshaw, the landowner, for permission to excavate at the site. Sabine Skae and Charlotte Hawley, Dock Museum, Barrow-in-Furness, for access to the material from the 20th century excavations. Professor Andrew Chamberlain for advice during the early stages of the project. Peter Burton and Steve Dickinson for information on the 1974 excavations. Tony Brown, Richard Mercer, and Alan Speight explored the rift and deeper chamber. Amy Brooks-Cole produced the digital microscope image of the shell beads for Figure 8. Jennifer Jones, David Robinson and two anonymous reviewers read and provided valuable comments on earlier versions of the paper. Radiocarbon sample measurements were carried out by Brendan Cullerton at Pennsylvania State University. The human remains were excavated and studied in line with the conditions set out in Ministry of Justice licence number 17-0022 and the University of Central Lancashire science ethics review panel (reference number Science 0127) with the final place of deposition being the Dock Museum, Barrow-in-Furness.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2025.10077

Funding Statement

Radiocarbon dating and the study of the demography and taphonomy of the human remains formed part of a PhD project funded by the University of Central Lancashire. DNA analysis was funded as part of the Wellcome Trust funded aGB: 1000 Ancient Genomes from Great Britain project.