Introduction

Classic analyses in political science hold that there is an inherent conflict between democracy and bureaucracy (e.g., Etzioni‐Halevey, Reference Etzioni‐Halevey1985, chapters 1 and 2; Fukuyama, Reference Fukuyama2014, chapter 3; Reference WeberWeber, 1978[1921]). Along the same lines, a wealth of studies points out how increased political competition leads to more clientelism and corruption, particularly in young democracies with less established bureaucratic structures to begin with (e.g., D'Arcy & Nistotskaya, Reference D'Arcy and Nistotskaya2017; Davis, Reference Davis2006; Keefer, Reference Keefer2007; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt2000; Piattoni, Reference Piattoni2001; Povitkina & Bolkvadze, Reference Povitkina and Bolkvadze2019; Shefter, Reference Shefter1977). In fact, under some circumstances, bureaucracy has historically thrived in authoritarian settings, preceding democratization (e.g., D'Arcy & Nistotskaya, Reference D'Arcy and Nistotskaya2018; Ertman, Reference Ertman1997; Geddes, Reference Geddes1994; Grindle, Reference Grindle2012; Haggard, Reference Haggard1990). Nevertheless, several recent studies show statistically that democracy, understood as contested elections with universal suffrage, generally strengthens bureaucratic quality, defined as effectiveness in implementation and autonomy from political pressure (e.g., Adserà et al., Reference Adserà, Boix and Payne2003; Bäck & Hadenius, Reference Bäck and Hadenius2008; Carbone & Memoli, Reference Carbone and Memoli2015; Wang & Xu, Reference Wang and Xu2018).

In this paper, we show that both classic and recent interpretations of the relationship are too simplistic. Our approach differs from previous studies in two fundamental ways. First, rather than assuming that universal suffrage follows contestation, we theoretically and empirically distinguish between contestation and inclusiveness (i.e., suffrage levels) as two separate dimensions of democracy. Second, rather than examining the broader notion of bureaucratic quality, which taps into impartial behaviour sometimes included in the concept of democracy, we focus on explaining the degree of meritocracy in the state administration, that is, the prevalence of skills‐based recruitment, as opposed to political or personal appointments. Meritocracy is the principal driver of bureaucratic quality and a key source of political conflict around bureaucratic reforms (Dahlström & Lapuente, Reference Dahlström and Lapuente2017).

We argue that electoral contestation can be related to higher levels of meritocracy but is likely to be conditional on the level of suffrage. In democracies, politicians seek to maximize their chances of winning the next election by catering to voter demands, and voters sometimes demand public goods, such as education and health care, which require longer‐term investment. By increasing their use of meritocratic employment, politicians will be able to provide better and more public goods. However, as is evident from research on clientelism in democracies (e.g., Hicken, Reference Hicken2011; Stokes et al., Reference Stokes and Dunning2013; see also Charron & Lapuente, Reference Charron and Lapuente2010), poorer voters are more likely to prefer particularistic goods, such as state jobs, allowances and contracts. In turn, when voters are poorer, politicians prefer lower levels of meritocracy since a more politicized bureaucracy will cater better for the provision of particularistic goods. Suffrage is important because voter preferences for public goods, and thus politicians’ incentives to strengthen meritocracy, weaken with lower voter income, which is most directly tied to suffrage rules, that is, the eligibility to vote. In this setting, politicians have incentives to engage in clientelist practices rather than strengthening meritocracy in the hope of winning the votes of the newly enfranchised and poorer voters. We therefore propose that the positive effect of contestation on meritocracy decreases with higher suffrage levels.

As the first of its kind, this paper tests the combined and separate effects of contestation and inclusiveness on a sample covering the entire modern period since the French Revolution. In the first wave of democratization before World War II, suffrage was at first limited to small and very rich segments of the population and then extended to poorer segments at different paces and at different points in time by lifting various socioeconomic restrictions. Thus, when we include the prewar period with substantial variation in suffrage in the analysis, we expect to find that suffrage weakens the positive relationship between electoral contestation and meritocracy. By contrast, after the war, universal suffrage and competitive elections were typically introduced simultaneously. There was thus limited variation in suffrage (Miller, Reference Miller2015; Przeworski, Reference Przeworski2009), which may explain the positive relationship between democracy and bureaucracy found in previous studies relying exclusively on post‐1945 observations.

We operationalize political inclusiveness as de jure rules of suffrage. Yet in order to focus on those rules that directly affect voter income, what we call socioeconomic restrictions, we use an indicator from Bilinski (Reference Bilinski2015) measuring adult male enfranchisement, thereby excluding age‐ and gender‐related suffrage extensions. To approximate electoral contestation, we use a variable on competitive elections from the Lexical Index of Electoral Democracy (LIED) (Skaaning et al., Reference Skaaning, Gerring and Bartusevičius2015), and for meritocracy, we use a variable measuring meritocratic recruitment in the state administration from the Varieties of Democracy (V‐Dem) dataset (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Alizada, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Hicken, Hindle, Ilchenko, Krusell, Lührmann, Maerz and Ziblatt2021a). Finally, to capture incumbents’ decisions on meritocracy in anticipation of upcoming elections, we use electoral spells as unit of analysis.

Our analyses support our propositions. There is a positive relationship between electoral contestation and meritocracy when examined over the entire period of modern democracy and when examined only in the later period, that is, after 1938. Moreover, in the period before World War II, contestation is only significantly related to meritocracy at lower levels of suffrage. In other words, the relationship between contestation and meritocracy is never negative when suffrage levels vary little within and between countries, while it is negative at higher suffrage levels in the period when there is a substantial variation in suffrage.

These results have several implications for the literature on the democracy–bureaucracy nexus. They indicate that electoral contestation is not uniformly positive for bureaucracy. Rather, they suggest that under some circumstances incumbents react to the enfranchisement of poorer voters by engaging in clientelist practices that impede bureaucratic development. This lends support for research pointing out that clientelism is a likely outcome of democracy in settings with a poorer electorate (e.g., Auyero, Reference Auyero2000; Dixit & Londregan, Reference Dixit and Londregan1996; Finan & Schechter, Reference Finan and Schechter2012; Hicken, Reference Hicken2011; Jensen & Justesen, Reference Jensen and Justesen2014; Magaloni, Reference Magaloni2006; Stokes, Reference Stokes2005; Stokes et al., Reference Stokes and Dunning2013). It also suggests that if we equate mean societal income with mean income in the electorate (e.g., Charron & Lapuente, Reference Charron and Lapuente2010), we overlook vital dynamics of the politics around bureaucracy. In short, to understand why democracy sometimes nurtures bureaucracy and sometimes does not, we need to distinguish between democratization as increased competition for political power and enfranchisement of the masses.

Democracy and bureaucracy in previous research

Many scholars argue that since democracy entails greater levels of electoral competition it incentivizes politicians to fight corruption and reduce clientelism, and a substantial amount of large‐N research finds that democracy is positively related to bureaucratic quality. The premises of this research are that the majority of any large electorate serves the collectively rational goal of impartial and clean administration, and that such accountability is effective (e.g., Adserà et al., Reference Adserà, Boix and Payne2003; Carbone & Memoli, Reference Carbone and Memoli2015; Keefer, Reference Keefer2007; Leipziger, Reference Leipziger2016; Wang & Xu, Reference Wang and Xu2018).Footnote 1

Bäck and Hadenius’ (Reference Bäck and Hadenius2008) study takes a mediating position between democracy and autocracy as the more effective promoter of bureaucratic quality. They find a J‐shaped relationship that, however, speaks to the advantage of democracy. Levels of bureaucratic quality are relatively high in full autocracies, low in semi‐democratic or democratizing countries and highest in full democracies. Bäck and Hadenius (Reference Bäck and Hadenius2008, p. 19) further employ ‘turnout’ and ‘newspaper circulation’ as intervening variables in order to examine the effectiveness of citizens’ control from below (and thus accountability) (see also Adserà et al., Reference Adserà, Boix and Payne2003, p. 475).

Charron and Lapuente (Reference Charron and Lapuente2010) propose a more complex theory and test. They argue that poor people tend to value the immediate consumption from clientelist linkages and patronage, while wealthier people value long‐term investment, which requires an efficient bureaucracy. Thus, there will be less demand for bureaucratic quality in poorer democracies than in the wealthier ones. Interacting various regime attributes with GDP per capita, they find the effect of democracy on bureaucratic quality to be positive at high levels and negative at low levels of economic development.

A few other studies focused specifically on merit reforms at the US sub‐national level support the notion that democracy is positive for bureaucracy (Ruhil & Camões, Reference Ruhil and Camões2003; Ting et al., Reference Ting, Snyder, Hirano and Folke2013). They argue that greater electoral uncertainty increases the incentives to strengthen meritocracy since the current incumbent wants to ensure against the use of bureaucracy for patronage and spoils by future oppositional incumbents.

Although the positive effect of democracy on bureaucracy in these studies is a relatively consistent finding, the studies suffer from a series of theoretical and analytical shortcomings. The most serious shortcoming is that they tend to subsume (near) universal suffrage under contestation when using measures from Polity and Freedom House that do not distinguish between these parameters. Indeed, their theoretical arguments are focused on contestation only, or what they sometimes simply term as ‘democracy’. Alternatively, they (e.g., Adserà et al., Reference Adserà, Boix and Payne2003; Bäck & Hadenius, Reference Bäck and Hadenius2008; Wang & Xu, Reference Wang and Xu2018) measure de facto participation as opposed to de jure rules of suffrage and treat this as an intervening variable rather than a separate dimension of democracy. Moreover, by measuring economic development levels rather than socioeconomic restrictions on suffrage, Charron and Lapuente (Reference Charron and Lapuente2010) focus on societal income, which does not equal the preferences of the voters when suffrage is not universal.

A number of classic studies have concluded that democracy is, at least under some circumstances, at odds with a well‐functioning bureaucracy (e.g., Etzioni‐Halevey, Reference Etzioni‐Halevey1985, chapters 1–2; Fukuyama, Reference Fukuyama2014, chapter 3). Indeed, political regime was introduced as an explanatory factor by Reference WeberMax Weber (1978[1921]), who famously identified bureaucracy as originating in 17th–19th century Prussia, a country that underwent various forms of authoritarianism and thus testifies to the different functional logics of bureaucracy and democracy. However, many of the studies that find a negative effect of democracy define democracy in general terms as related to contestation or accountability (e.g., Ertman, Reference Ertman1997; Geddes, Reference Geddes1994).Footnote 2 Also, the vast literature on clientelism in democracies (e.g., Davis, Reference Davis2006; Dixit & Londregan, Reference Dixit and Londregan1996; Hicken, Reference Hicken2011; Jensen & Justesen, Reference Jensen and Justesen2014; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt2000; Stokes, Reference Stokes2005; Magaloni, Reference Magaloni2006) provides highly valuable insights on the risk of contestation resulting in a race for delivering targeted goods, especially for poorer electorates. Nevertheless, none of these studies systematically relate different voter preferences and degrees of clientelism to different suffrage rules.

A second shortcoming is the broad focus on bureaucratic quality or ‘government effectiveness’, which to varying degrees is understood as the (non‐)corrupt or (im)partial behaviour of bureaucrats or politicians. While these concepts and their related measures are standard in comparative analysis, they are conceptually very closely related to the management of clean elections and the protection of civil and political rights (Hartlyn et al., Reference Hartlyn, McCoy and Mustillo2008; Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2011), which are included in common understandings of democracy (e.g., Dahl, Reference Dahl1971).

Theory: Electoral contestation, political inclusiveness and bureaucracy

We focus on meritocratic recruitment (i.e., the hiring and firing of civil servants on the basis of their skills), which is the essential feature of a bureaucratic state administration. Its counterpart, patrimonialism, denotes recruitment based on political or personal connections (Dahlström & Lapuente, Reference Dahlström and Lapuente2017). In any political context, politicians face the choice of strengthening or weakening meritocracy in the state administration. Civil servants are important actors given their interest in preserving organizational privileges and, often extensive, powers to pursue these interests (Nordlinger, Reference Nordlinger1981), and where bureaucracy is institutionalized, norms and laws significantly limit the access of politicians to hire and fire civil servants (Shefter, Reference Shefter1977). However, even here, political incumbents often have de jure and de facto discretionary powers over some hiring and firing decisions (Cooper, Reference Cooper2021); and in most cases, where bureaucracy is less institutionalized, politicians are the primary decision‐makers in these matters. Thus, we see meritocratic recruitment as a political choice made by politicians.

The degree to which politicians choose to use meritocratic recruitment in democracies is mainly a result of what they believe would be a vote maximizing strategy in foresight of the next election. On the one hand, if elected politicians choose to strengthen meritocracy, they will be able to provide more and better public goods (e.g., Lewis, Reference Lewis2008). On the other, they also lose control over the appointment of civil servants. Civil servants that are not politically appointed will be less inclined to use their discretionary power to favour clients of a particular political party. In turn, politicians will be less able to provide particularistic goods to reward clients in exchange for political support, and consequently, they lose a major asset in the fight for political power (Cornell & Grimes, Reference Cornell and Grimes2015; Hicken, Reference Hicken2011; Stokes et al., Reference Stokes and Dunning2013).

Moreover, the incentives for elected politicians to use more or less meritocratic or patrimonial recruitment crucially depend on voters’ demands (Charron & Lapuente, Reference Charron and Lapuente2010, pp. 450–454; see also Piattoni, Reference Piattoni2001). A general and fundamental voter interest is to secure a prosperous living for which voters view political participation as an important instrument (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000; Magaloni, Reference Magaloni2006). Because politics is about distributing scarce resources, democracy is both an opportunity and a source of uncertainty for voters’ future access to those resources.

As suggested by Charron and Lapuente (Reference Charron and Lapuente2010), the types of preferences that matter for meritocracy concern the distinction between public and private or particularistic goods. Poorer people, all things being equal, tend to prefer particularistic targeted goods for immediate consumption, while the richer middle and upper classes have a surplus of resources to focus on public goods that benefit others as well. If the electorate demands more public goods, politicians have incentives to implement meritocratic recruitment to better serve the long‐term investments and impartiality needed for effective public goods delivery. If the electorate demands particularistic goods, politicians may use patrimonial recruitment to target voters directly and with fewer administrative constraints. Thus, voters do not directly demand meritocracy or patrimonialism; indeed, voters typically know little about the inner workings of government. Rather, politicians are attentive to the effects of meritocracy and thus supply the amount needed to satisfy specific voter demands for public or particularistic goods.

Politicians’ choice to implement more or less meritocracy is thus affected by whether they risk losing elections if they do not cater to voters’ demands, but these demands are likely to depend on the characteristics of the electorate. This makes the distinction between electoral contestation and political inclusiveness relevant. We define electoral contestation in Schumpeterian terms as genuine competition for government offices, implying ex ante uncertainty about the outcome of multiparty elections (Skaaning et al., Reference Skaaning, Gerring and Bartusevičius2015, p. 1495). Inclusiveness regards the proportion of the population that has the right to participate in elections, as measured by voting rights. Empirically, contestation and inclusiveness vary independently as contestation has at times been a sole matter for established political elites, whereas inclusiveness concerned the masses’ demands (Dahl, Reference Dahl1971, p. 4; Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Alvarez and Maldonado2008; Miller, Reference Miller2015). Thus, to understand politicians’ inclinations for more or less meritocracy, we need to distinguish between democracy as electoral contestation on the one hand and inclusiveness on the other.

Electoral contestation and bureaucracy

The studies that find a positive relationship between democracy and bureaucracy hold that public goods provision is a highly salient concern on voters’ agenda. In turn, as voter preferences become more important with increasing electoral contestation, politicians are more likely to be punished for clientelist practices because clientelism redistributes resources toward targeted private goods and away from non‐targeted public goods. Conversely, while voters may not perceive changes towards more meritocratic recruitment, voters would reward politicians for the improved delivery of public goods that meritocracy brings (Charron & Lapuente, Reference Charron and Lapuente2010).Footnote 3

Losing incumbent power in a system with a patrimonial administration means losing the possibility to reward supporters through particularistic policies (Ting et al., Reference Ting, Snyder, Hirano and Folke2013). Should the current incumbent lose political power in an upcoming election, he or she would therefore also like to limit the powers of the incoming incumbent. To this end, using meritocratic recruitment becomes an appealing strategy for the current incumbent. For the same reasons, i.e., to mitigate the risk of bureaucratic discrimination in the future and to cater for voter preferences for public goods, opposition parties would likewise support meritocracy, in turn making a pro‐meritocratic parliamentary majority more likely (Lapuente & Rothstein, Reference Lapuente and Rothstein2014).

In sum, we expect electoral contestation to be positively related to the degree of meritocracy. However, the positive effect should mainly regard electorates that prefer public to particularistic goods. We thus need to move beyond contestation in order to explain variation in voters’ demands.

Political inclusiveness and bureaucracy

Political parties tend to adopt clientelistic linkage strategies if the population is relatively poor because poorer people demand goods for immediate consumption (Charron & Lapuente, Reference Charron and Lapuente2010). Clientelist linkage strategies are attractive since delivering particularistic goods to poor voters is less costly than investing in public goods (e.g., Dixit & Londregan, Reference Dixit and Londregan1996; Jensen & Justesen, Reference Jensen and Justesen2014; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt2000; Magaloni, Reference Magaloni2006; Stokes, Reference Stokes2005; Stokes et al., Reference Stokes and Dunning2013; Weitz‐Shapiro, Reference Weitz‐Shapiro2012). Moreover, clientelism is a particularly effective vote‐maximizing strategy among the poor because recipients of targeted goods are likely to develop feelings of reciprocity and a stable commitment to support their political patron (Auyero, Reference Auyero2000; Finan & Schechter, Reference Finan and Schechter2012; see Kao et al., Reference Kao, Lust and Lise2017, p. 4). Some proponents even argue that these conditions make clientelism the default strategy of politicians under conditions of electoral uncertainty (Geddes, Reference Geddes1994, pp. 14–18; Piattoni, Reference Piattoni2001).

Thus, the relationship between electoral contestation and bureaucracy is stronger in wealthier countries (Charron & Lapuente, Reference Charron and Lapuente2010). We argue, however, that the specific composition of the electorate is important since politicians primarily care about people who are eligible to vote. Politicians have much weaker incentives to make policies that target those outside the electorate.

Historically, the composition of the electorate changed as a result of changes in voting rights. Competitive regimes in 19th‐century Europe and Latin America generally excluded poor men (and often all women irrespective of income) from electoral participation. Through the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the inclusiveness of these regimes increased at different paces but typically with the abolishment of socioeconomic requirements, such as property, economic dependence, gross income, tax payments and literacy, which lowered the mean voter income (Przeworski, Reference Przeworski2009).Footnote 4 Suffrage extensions were gradual in countries like the United Kingdom and Sweden and more abrupt in Germany 1918, but few countries with competitive elections granted universal manhood suffrage in one stroke (Dahl, Reference Dahl1971). Thus, suffrage without socioeconomic restrictions was the historical exception rather than the rule.

When suffrage is extended downwards through the income distribution of society, the composition of the electorate changes as the new electorate includes poorer voters. These voters tend to demand goods for immediate consumption, such as jobs and social benefits, or more fundamentally, food and shelter. To be sure, this is not due to a lack of moral virtues among poorer voters, but rather economic necessities. Poorer voters are also interested in public goods. However, poorer voters are, all things being equal, more likely to substitute away from society‐wide economic investments to receive short‐term economic benefits that may secure their income, indeed sometimes their well‐being and survival (Jensen & Justesen, Reference Jensen and Justesen2014; Weitz‐Shapiro, Reference Weitz‐Shapiro2012). This incentivizes politicians to build clientelist linkages with these new voters.

In addition, clientelist linkages are likely to become path‐dependent as these poor voters come to rely on patronage goods to solve everyday problems, and politicians come to rely on the continued support of these clienteles to secure re‐election (Auyero, Reference Auyero2000; Finan & Schechter, Reference Finan and Schechter2012; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt2000; Weitz‐Shapiro, Reference Weitz‐Shapiro2012).

Summing up, the removal of socioeconomic restrictions on suffrage should entail considerable incentives for politicians to deliver targeted goods to the poorer voters by refraining from meritocratic recruitment, implying that higher levels of suffrage are negatively related to the degree of meritocracy. Thus, the positive relationship between electoral contestation and meritocracy should decrease with higher suffrage levels.

Case illustrations

Two often cited cases regarding meritocracy and clientelism, mid‐19th century United Kingdom and early 20th century Argentina, illustrate our propositions. In the United Kingdom, the existence of electoral contestation was essential for fighting the ‘Old Corruption,’ where public offices were systematically distributed as patronage to local constituents. Reform first came on the agenda around the American Independence War as the First Pitt Ministry realized that administrative inefficiencies severely limited public finances (O'Gorman, Reference O'Gorman and Piattoni2001, p. 59). Over the next decades, Pitt, pushed by Whig opposition and emerging upper middle classes (O'Gorman, Reference O'Gorman and Piattoni2001, pp. 70–71), had to deliver what Shefter (Reference Shefter1977, p. 435) terms the ‘rationalizing bourgeoisie’.

Until around 1850, civil servant pensions were cut, and useless offices were abolished, but the norm of patronage‐driven appointment remained intact. The Northcote‐Trevelyan report of 1854, proposing open, competitive examinations and merit‐based promotions, was a response to various previous developments but notably among them was the 1832 Reform Act (e.g., MacDonagh, Reference MacDonagh1977, pp. 198–203). This act installed genuine competition by ending the nobility's control over MP elections and extending suffrage from around 5 to 17 per cent of the total male population (Bilinski, Reference Bilinski2015), enfranchising small landowners, tenant farmers and shopkeepers in the counties (O'Gorman, Reference O'Gorman and Piattoni2001, pp. 61–65). The 1867 Act, which increased suffrage to around 40 per cent of the total male population (Bilinski, Reference Bilinski2015) by enfranchising householders and lodgers and lowering property requirements generally, finally forced the aristocracy to implement the recommendations of Northcote‐Trevelyan, as the new voters demanded public goods such as better roads and trade regulations (Lizzeri & Persico, Reference Lizzeri and Persico2004). Open and competitive examinations were made mandatory for almost all agencies in the British civil service by an order in council in 1870 (MacDonagh, Reference MacDonagh1977, pp. 197–213). Thus, oppositional pressure and increasing voter demands for public goods as suffrage was extended gradually to the middle classes provided politicians with incentives for meritocratic improvement.

Argentina is different in two respects: First, patrimonialism remained dominant throughout the pre‐ and interwar periods, despite the introduction of competitive elections through the Sáenz Peña Law of 1912 (Rock, Reference Rock1972, pp. 233–234). Second, contestation may have failed to strengthen meritocracy because male suffrage had been universal since reforms in 1856 when suffrage was extended to all Argentinean men above the age of 17 (Alonso, Reference Alonso2000, p. 144). Famously, Yrigoyen's Radical Party, dominant in Argentina's first democratic period, based its electoral victory in 1916 on clientelist linkages by promising and later delivering government sector jobs to the new constituencies, who otherwise faced great economic insecurity. After an erosion in popularity following labour strikes in 1919, Yrigoyen saw no other way than to once again inflate bureaucracy to saturate voter demands (Horowitz, Reference Horowitz2008, pp. 65–67; Rock, Reference Rock1972, p. 236).

In sum, whereas legacies of patrimonialism were entrenched in the United Kingdom and Argentina before electoral contestation, the transition to contestation amidst near‐universal manhood suffrage in Argentina reduced incentives to use meritocratic recruitment, instead continuing patrimonialism in the form of clientelism. In the United Kingdom, political competition with piecemeal suffrage extensions to middle class segments gradually strengthened meritocracy. These diverging patterns were partly driven by differences in voter preferences for particularistic versus public goods, and subsequently politicians’ supply of clientelism versus meritocracy.

Research design and data

Our research design and data confront the main problem of the previous literature head on: Since there was a huge variation in suffrage levels before World War II, the relationship between democracy and bureaucratic quality may be weaker than what has been found in previous studies when we include the prewar period in the analysis. Specifically, we examine electoral contestation and political inclusiveness separately and in conjunction from the beginning of the 19th century up until today, and with sub‐samples before and after the advent of World War II (and before and after the end of the war). We focus on this periodic distinction because these periods clearly differ in terms of suffrage variation. Before the war, suffrage rights varied considerably (e.g., Dahl, Reference Dahl1989, pp. 234–239; Miller, Reference Miller2015). In contrast, former colonies and other countries that democratized after the war almost always went from having autocratic regimes with no electoral competition, where suffrage is meaningless, to contestation with universal suffrage. Moreover, by far most of the countries that underwent democratization earlier already achieved full (male) suffrage before the war or shortly after (e.g., Dahl, Reference Dahl1989, pp. 234–239; Miller, Reference Miller2015). Suffrage levels thus varied much less within and between countries in the postwar setting.

Since our argument is based on the choice of more or less meritocratic recruitment made by incumbents during their mandate, we structure our data in spells that run from one election to the next in each country time series. Observations are thus per country election period spells. The first spell for a country starts whenever there is a first election in that country. We only include spells that are shorter than 10 years, since with longer periods we cannot assume that elections are forthcoming. However, robustness tests with different thresholds for length of spells largely confirm our main findings.

We use the indicator ‘Election type’ from V‐Dem (v11.1) (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Hicken, Hindle, Lührmann, Maerz, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Paxton and Ziblatt2021b, pp. 57–58) to code election spells. We choose the election periods for legislative elections as our main data structure since we are then able to include both presidential and parliamentary systems. However, we also perform robustness tests with three additional types of spells for executive elections (for presidential systems) and legislative elections. We thus examine our hypotheses with data structures based on four different types of spells:

Legislative elections in both parliamentarian and presidential regimes (our main models)

Executive elections in presidential systems

Executive elections combined with legislative elections in both types of systems

Legislative elections only counted for parliamentary systems combined with executive elections in other systems

Our dependent variable is the level of meritocracy in the last year of each election period spell. The base model we estimate uses OLS regression and employs country‐fixed effects, which mitigates problems with omitted variable bias in terms of time‐invariant cross‐sectional factors that may be correlated with the two dimensions of democracy and with meritocracy. We also control for the level of meritocracy at the beginning of the spell to mitigate problems with reverse causation and serial autocorrelation, which are present in time series data. In particular, this addresses the notion that the initial strength of bureaucratic norms limits the incumbent's ability to politicize the administration (e.g., Shefter, Reference Shefter1977), and that bureaucratic quality, including meritocracy, strengthens democracy (Andersen & Doucette, Reference Andersen and Doucette2022; Cornell & Lapuente, Reference Cornell and Lapuente2014). Moreover, we use robust country‐clustered standard errors to account for within‐cluster correlation. We also control for the number of election spells a country has experienced before each spell to control for factors related to the electoral history, including the initial level of uncertainty experienced by the incumbent, which could affect incentives to employ more or less meritocratic recruitment. Election spells partly control for country specific time trends. In robustness tests, we control for time trends by including year and decade dummies in our models.

Electoral contestation

To measure electoral contestation, we use the binary indicator of ‘Minimally competitive, multiparty elections for legislature and executive’ from LIED, corresponding to level four on the index which is based on a qualitative assessment of the existence of genuinely competitive, multiparty elections for the executive and legislative offices (Skaaning et al., Reference Skaaning, Gerring and Bartusevičius2015). This indicator captures the Schumpeterian notion of democracy, which aligns with our definition of electoral contestation, and does not include any suffrage criteria.

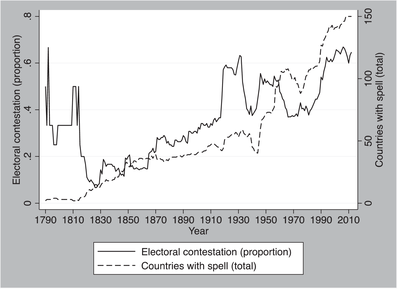

Figure 1 shows the development in electoral contestation over time with the proportion of countries classified as having electoral contestation in a given year according to the LIED measure. Developments over time are, however, hard to compare directly since the number of countries with elections changes, for example with decolonization after World War II. The figure therefore also tracks the total number of country election spells. We can see that the proportion of countries with electoral contestation varies both over time and between countries, even as the number of countries with elections increases.

Figure 1. Proportion of countries with electoral contestation, 1790–2012.

Note: Based on data from Reference Skaaning, Gerring and BartusevičiusSkaaning et al. (Reference Skaaning, Gerring and Bartusevičius2015). Legislative election spell sample.

Suffrage levels

Most indicators of suffrage simply measure the percentage of the population with the right to vote. For instance, V‐Dem's ‘Share of population with suffrage’ indicator provides us with the overall population share and not the exact number of enfranchised people related to specific types of extensions (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Hicken, Hindle, Lührmann, Maerz, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Paxton and Ziblatt2021b, pp. 60–61). Instead, we use data from Bilinski (Reference Bilinski2015), who has coded the share of enfranchised adult males above the minimal voting age. In effect, we exclude suffrage extensions due to gender or age, which constitute the most frequent types of extensions unrelated to socioeconomic conditions (Przeworski, Reference Przeworski2009). Bilinski only codes suffrage levels in countries with elected institutions. This aligns with our theory since suffrage makes little conceptual sense in the absence of elections. At the same time, the mere existence of elections is insufficient for electoral contestation as we define and measure it, which means that our suffrage indicator does not exclude relevant variation in contestation.

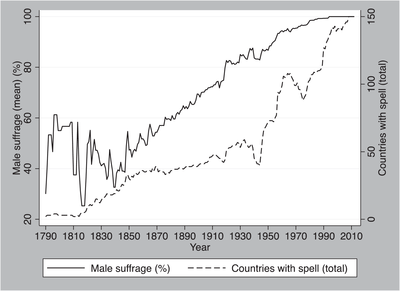

Figure 2 shows the global mean share of enfranchised male adults over time using the Bilinski measure as well as the total number of country election spells. We see the expected pattern of an increasing trend in suffrage levels before World War II, reflecting the gradual lifting of socioeconomic suffrage restrictions. The steepest increase happened immediately after World War I, coinciding with the well‐known mass democratizations following in its aftermath. The curve rises again from around 1950, but the increase is not as steep and takes off from a 90 per cent level of male suffrage, that is, close to universal suffrage. Compared with the sharp increase in the sample size around this time, this is evidence that most suffrage extensions occurred before World War II. In our statistical models, we use the same suffrage data but scaled as proportions (0–1) rather than percentages (0–100).

Figure 2. Suffrage levels, global averages, 1790–2012.

Note: Based on data from Bilinski (Reference Bilinski2015). Legislative election spell sample.

Meritocracy

Recent large‐N studies on the postwar period rely on measures of bureaucratic quality with poor temporal coverage. The ‘Weberianness Scale’ from Rauch and Evans (Reference Rauch and Evans2000) as well as the measures from the World Bank (e.g., Bäck & Hadenius, Reference Bäck and Hadenius2008; Charron & Lapuente, Reference Charron and Lapuente2010) and the Political Risk Services Group ICRG (e.g., Adserà et al., Reference Adserà, Boix and Payne2003; Bäck & Hadenius, Reference Bäck and Hadenius2008; Charron & Lapuente, Reference Charron and Lapuente2010; Leipziger, Reference Leipziger2016) are limited to the post‐1980 period, and Hanson and Sigman's (Reference Hanson and Sigman2021) extension only goes back to the 1960s (e.g., Wang & Xu, Reference Wang and Xu2018). The indicator of ‘Basic administration’ from the Bertelsmann transformation index (e.g., BTI, 2010) provides an even shorter time span, with scores from 2006, 2008 and 2010 (e.g., Carbone & Memoli, Reference Carbone and Memoli2015).

In addition, the World Bank and ICRG measures suffer from serious validity issues (Hanson & Sigman, Reference Hanson and Sigman2021; Saylor, Reference Saylor2013). For example, the ICRG measure lacks transparency and accuracy in noting that bureaucracy should be ‘somewhat autonomous from political pressure’ (ICRG, 2014, p. 7) and is also low in validity since it equates bureaucratic quality with ‘strength and expertise to govern with drastic changes in policy or interruptions in government services’ (ICRG, 2014, p. 7). Indeed, output stability may imply the exact opposite of an impartial and meritocratic administration.

To mitigate these problems, we employ the expert‐coded indicator ‘Criteria for appointment decisions in the state administration’ from V‐Dem, which covers a broad sample of countries from 1790 up until today. The exact question wording is: ‘[T]o what extent are appointment decisions in the state administration based on personal and political connections, as opposed to skills and merit?’ (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Hicken, Hindle, Lührmann, Maerz, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Paxton and Ziblatt2021b, p. 189). This question directly taps into the degree of meritocratic recruitment in the state administration. Rather than measuring impartiality, the indicator focuses on the key organizational feature of Weberian bureaucracy. For the questions coded by experts, the V‐Dem team mitigates reliability and measurement biases by assigning five experts to code each country and then aggregating coding decisions into point estimates employing Bayesian item response theory (IRT) modelling techniques. Assuming that the point estimates are latently interval, inter‐coder reliability checks and uncertainties are used to convert the ordinal into an interval scale. The point estimates for pre‐1900 observations, with only one expert per country, are based on anchoring vignettes with hypothetical coding scenarios and extended coding by the historical expert for the 1900–1920 period that is then compared with the equivalent coding by the contemporary experts (Knutsen et al., Reference Knutsen, Teorell, Wig, Cornell, Gerring, Gjerløw, Skaaning, Ziblatt, Marquardt, Pemstein and Seim2019, p. 444; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt, Tzelgov, Wang, Krusell and Miri2021).

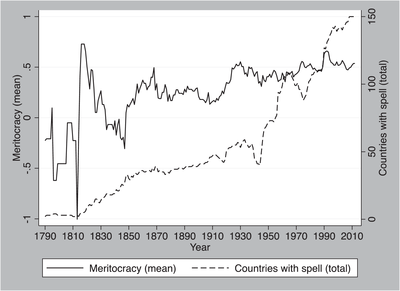

Figure 3 plots the global mean of meritocracy using the V‐Dem measure and the total number of country election spells over time. The extreme year‐to‐year changes in the early decades of the 19th century are due to the low number of countries. As the sample increases, the changes flatten. We see much fluctuation, but also a much less clear, positive trend compared with the developments in contestation and suffrage. The most pronounced increases occur from around 1910 to 1930, a short period in the 1970s, and around 1990, the latter of which plausibly relates to the breakup of the Soviet Union. Meritocracy levels then drop in the 1990s. The overall stasis and pattern of deepening and quick recessions of meritocracy reflect established findings in the literature on bureaucracy and corruption (e.g., Fukuyama, Reference Fukuyama2014; Olsen, Reference Olsen2008).

Figure 3. Meritocracy levels, global averages, 1790–2012.

Note: Based on the indicator ‘Criteria for appointment decisions in the state administration’ from V‐Dem (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Alizada, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Hicken, Hindle, Ilchenko, Krusell, Lührmann, Maerz and Ziblatt2021a). Legislative election spell sample.

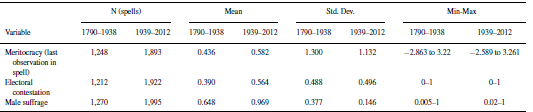

In sum, the indicators we use capture the most common trends seen in research on democratization and bureaucratization. Table 1 further shows the sharp differences between the periods before 1939 and after 1938. The differences are particularly pronounced for male suffrage with a much lower standard deviation in the later period. Thus, the variation in suffrage levels is much larger in the earlier period.

Table 1. Contestation, suffrage and meritocracy: Summary statistics comparison between time periods

Note: Sample based on legislative election spells of less than 10 years.

Control variables

The analyses include a battery of confounders, measured at the beginning of each election spell. Scholars have traditionally connected bureaucratization with war, the size of the economy and human capital (e.g., Ertman, Reference Ertman1997; Rauch & Evans, Reference Rauch and Evans2000). In the base models, we include economic development measured with GDP per capita (logged) based on the Maddison data (Bolt & van Zanden, Reference Bolt and van Zanden2020), including robustness tests with an imputed version (Fariss et al., Reference Fariss, Crabtree, Anders, Jones, Linder and Markowitz2017). We include the number of previous election spells since a longer electoral history may decrease politicians’ propensity to shift to clientelism (Dahl, Reference Dahl1971), and since there is a strong path dependence in the development of meritocracy (Shefter, Reference Shefter1977), we also control for the level of meritocracy in the first year of each spell. Our use of country‐fixed effects likewise addresses these concerns, but also puts severe restrictions on the data. In sum, all our models constitute hard tests of the effects of democracy.

In another set of models, we add controls for the instance of inter‐state war from the Correlates of War dataset (Sarkees & Wayman, Reference Sarkees and Wayman2010) and the level of human capital measured by the average years of education for persons above the age of 15 from Clio Infra (van Leeuwen et al., Reference van Leeuwen, van Leeuwen‐Li and Foldvari2018). Descriptive statistics for all variables in the different time periods are reported in the Supporting Information Appendix, Table A1.A.

Results

In this section, we first run regressions to examine the general relationship between contestation and meritocracy. Because suffrage only varied considerably and should thus only condition contestation before WWII, we run separate models for the pre‐1939 and post‐1938 periods as well as the whole period. Table A1.B–D report the countries included in the different samples. As a robustness test, we also apply a 1945–1946 cutoff as an alternative to capture pre‐ and postwar differences.

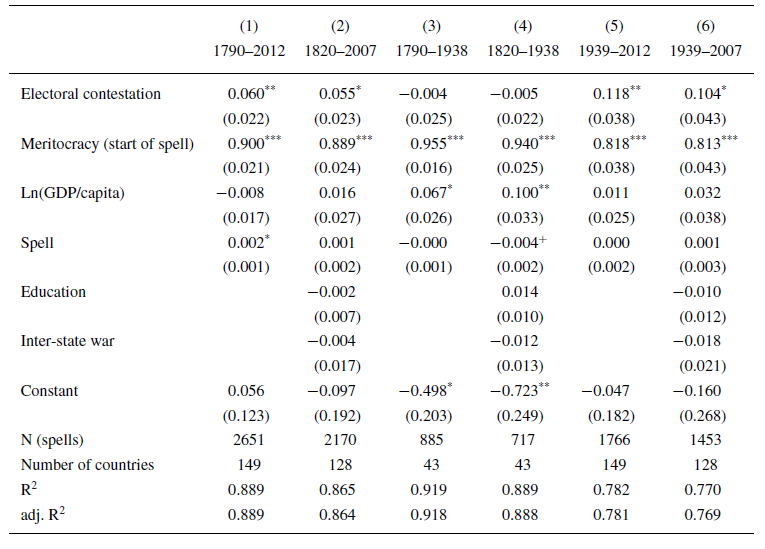

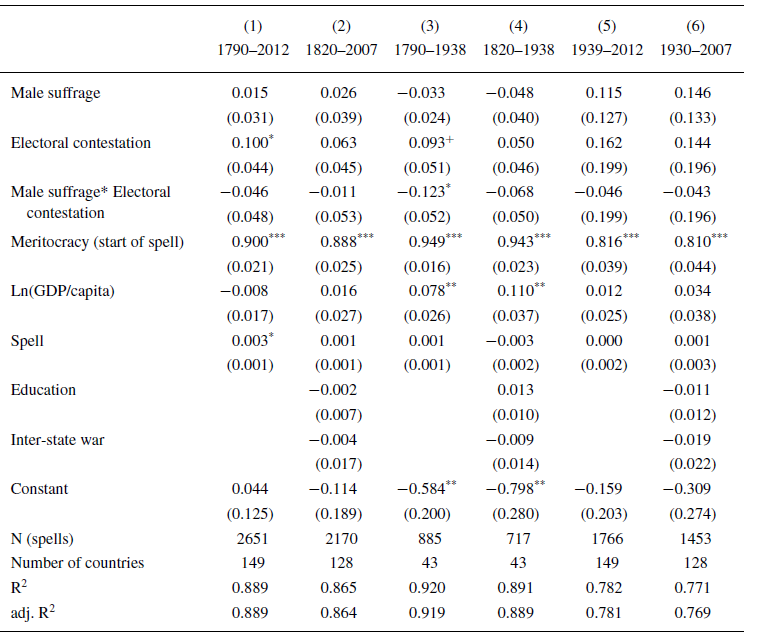

Table 2 reports results showing a positive relationship between electoral contestation and meritocracy for the models with the whole period and the model with the later period. However, there are no significant associations between the two variables for the models in which only the earlier period is included.

Table 2. Country‐fixed effects regression: Contestation and meritocracy

Note: Dependent variable: Meritocracy by the end of the spell. Clustered standard errors in parentheses. Spells of less than 10 years included in the analysis. All control variables measured at the start of the spell. Time period denotes first year in the spell. +p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Table 3 shows the predicted values for meritocracy with and without electoral contestation from the models with significant results. The substantial effects of moving from no contestation to contestation are quite small, but larger for the later period (Models 5 and 6) than for the whole period (Models 1 and 2).

Table 3. Adjusted linear predictions for meritocracy: Electoral contestation

Note: Based on models from Table 2. Calculations using margins in Stata. All other variables are set at their mean or as balanced.

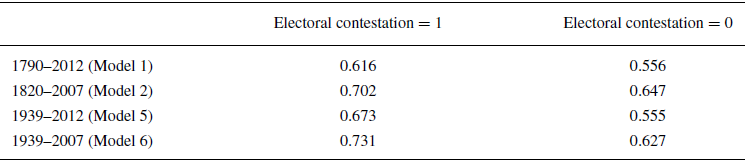

In Table 4, we use the same sample, but replace electoral contestation for male suffrage. We can see that male suffrage is insignificant, except in the earlier period in which there is a significant, negative relationship between suffrage and meritocracy (Model 3). Once we add the additional controls, the relationship remains significant at p < 0.1 (Model 4).

Table 4. Country‐fixed effects regression: Suffrage and meritocracy

Note: Dependent variable: Meritocracy by the end of the spell. Clustered standard errors in parentheses. Spells of less than 10 years included in the analysis. All control variables measured at the start of the spell. Time period denotes first year in the spell. +p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

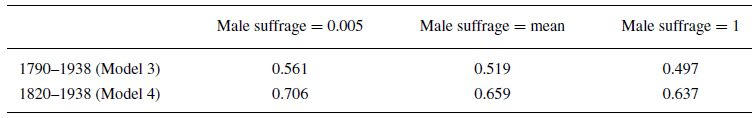

Table 5 shows the predicted values for the two models with significant results. Again, the effects are quite small, but as expected, the predicted value of meritocracy is lowest at high levels of male suffrage. For Model 4, with the full set of controls, the predicted value is 0.637 at the highest level of suffrage in the sample whereas the predicted value is 0.706 at the lowest level.

Table 5. Adjusted linear predictions for meritocracy: Suffrage

Note: Based on models from Table 4. Calculations using margins in Stata.

Running the analysis with male suffrage and contestation in the same model does not change the results for either of the factors (Supporting Information Appendix, Table A2). Electoral contestation remains significant in the models for the whole time period and for the later period, and male suffrage remains significant in the earlier period. Also, the coefficient and effect sizes are similar for the models with significant results on these two variables.

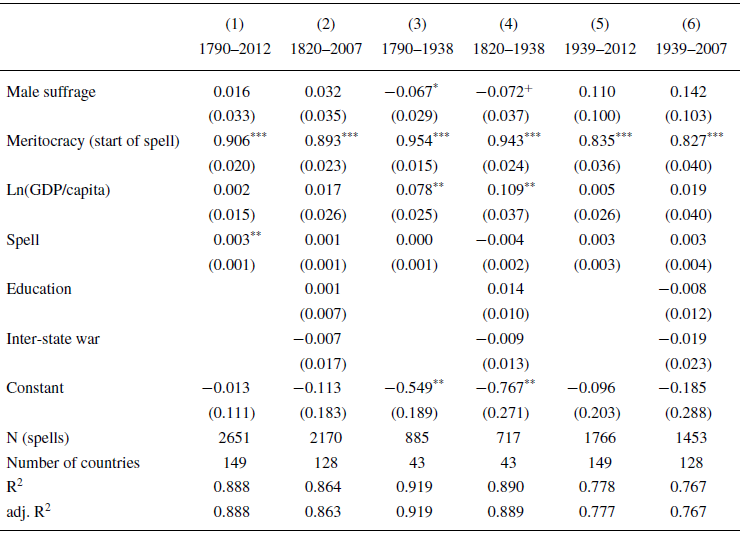

Table 6 shows the results from analyses of the conditional relationship. Again, the results clearly differ between the two periods. In the models with the whole period and the later period, there is no significant interaction. Yet in the models with the earlier period, there is a significant and negative interaction (at p < 0.05) in the base model (Model 3). In the model with additional controls, the coefficient for the interaction term is in the same direction, but smaller and insignificant.

Table 6. Country‐fixed effects regression: Conditional relationship

Note: Dependent variable: Meritocracy by the end of the spell. Clustered standard errors in parentheses. Spells of less than 10 years included in the analysis. All control variables measured at the start of the spell. Time period denotes first year in the spell. +p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

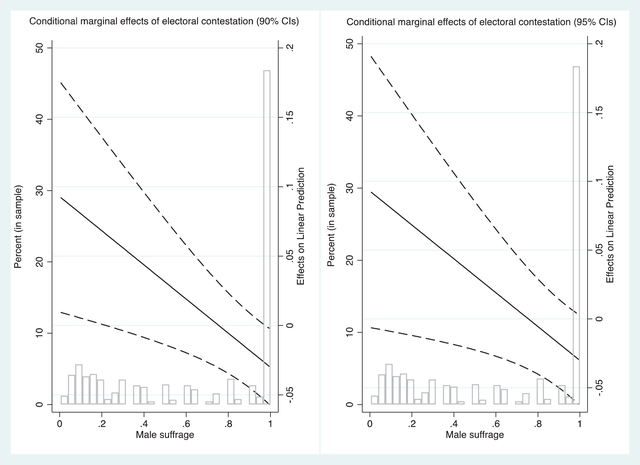

Figure 4 illustrates the significant, conditional relationship in the earlier period (Model 3, Table 6) by plotting the conditional marginal effects of contestation at different levels of suffrage. Histograms show the distribution of country spells across levels of male suffrage in the sample. The conditional marginal effect of contestation is only significant and positively related to meritocracy at lower suffrage levels, approximately below 21.5 per cent, and is increasingly more negative with higher levels of suffrage. Approximately 23 per cent of the spells in this sample have suffrage levels below 21.5 per cent.

Figure 4. Conditional marginal effects of electoral contestation on meritocracy at different levels of suffrage, pre‐1939. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: The figures are based on Model 3, Table 6. All other variables are set at their mean or as balanced. Left panel shows 90 per cent confidence intervals; the right panel 95 per cent confidence intervals.

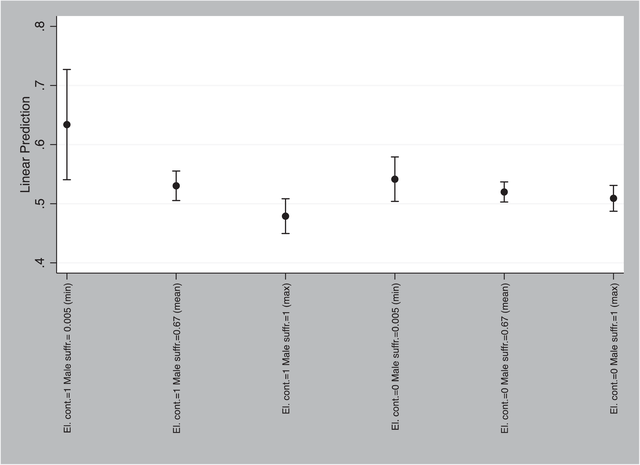

Figure 5 provides the adjusted predicted values of meritocracy for different combinations of suffrage levels and electoral contestation, again based on Model 3 (Table 6). Although the effects remain small, they do exist. Moreover, the effect of contestation when going from minimum to maximum suffrage level (0.48 to 0.63, i.e., 0.15) is larger than the comparable, separate effect of suffrage (0.497 to 0.561, i.e., 0.064) and contestation (0.556 to 0.616, i.e., 0.06). This suggests that an important aspect of the democracy‐effect on bureaucracy relates to the conditional impact of suffrage on contestation. Moreover, as expected, there is not much variation in the predicted values for the different combinations of suffrage levels when there is no electoral contestation.

Figure 5. Adjusted linear predictions for meritocracy at different values of contestation and suffrage, pre‐1939 (95 per cent confidence intervals).

Note: The figure is based on Model 3, Table 6. All other variables are set at their mean or as balanced. Calculated using margins in Stata.

Robustness tests

In the Supporting Information Appendix, we report results from several robustness tests that mitigate biases in the models.

First, we further address time trends by including year dummies and decade dummies in the models. For models testing the direct effects of contestation and suffrage separately, the results substantially stay the same, except that in the base model, suffrage is no longer significant in the earlier period with year dummies (Tables A3–A4). In the models with the interaction of contestation and suffrage (Tables A5–A6), the interaction term stays significant (at p < 0.1) in the base model for the earlier period (Model 3).

Next, since we lose quite some observations with some of our controls, we run the same models with an imputed version of the most important control variable, GDP per capita (Tables A7–A9). We use the variable constructed by Fariss et al. (Reference Fariss, Crabtree, Anders, Jones, Linder and Markowitz2017), which is based on a range of sources, including the Maddison data. The results basically remain the same, although suffrage becomes insignificant in the base model for the pre‐1939 period (Table A8, Model 3). Nevertheless, the conditional relationship in the pre‐1939 model becomes stronger (Table A9, Model 3). Figure A1 illustrates this with marginal conditional effects of contestation at different levels of suffrage in the pre‐1939 period, and Figure A2 shows the adjusted predicted values for meritocracy at different values of contestation and suffrage.

Arguably, we set an arbitrary threshold at spells shorter than 10 years, and our results could be driven by certain spell lengths. We thus run the interaction models for the pre‐1939 period with different thresholds as well as with no threshold (Table A10). The conditional marginal effects of electoral contestation in models with different thresholds are plotted in Figure A3. The slope is in the right direction, and the interaction is significant in all models, except for the one with the shortest period comprising a maximum of 4‐year spells. Obviously, this is the model in which we lose most observations since many spells in the earlier period are longer than 4 years. Our results are thus largely robust to different thresholds.

Also, as there are spells that end and start in the same year, we exclude those observations and rerun the analyses (Tables A11–A13). The results remain unchanged.

Tables A14–A16 report results for models with an alternative 1945–1946 cut‐off. The results for the interaction do not change. However, while significant in the base model, the negative relationship between suffrage and meritocracy in the early period (pre‐1946) weakens. This may be due to the inclusion of warring years when the usual democratization and bureaucratization dynamics froze. Suffrage is, moreover, positively (significant at p < 0.1) related to meritocracy in the period post‐1946, but only in the model with the full set of controls.

We also run analyses substituting contestation for freedom of expression and legislative constraints on the executive, respectively measured using V‐Dem's ‘Freedom of expression and alternative sources of information index’ and ‘Legislative constraints on the executive index’ (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Hicken, Hindle, Lührmann, Maerz, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Paxton and Ziblatt2021b). Although freedom of expression and legislative constraints are largely endogenous to contestation (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Alvarez and Maldonado2008), they vary independently of contestation to some extent (e.g., Lauth, Reference Lauth2015) and may yield separate impacts on meritocracy (e.g., Leipziger, Reference Leipziger2016, p. 8). No interactions between freedom of expression and suffrage reach significance, and the interaction between legislative constraints and suffrage is only significant at p < 0.1 for the later period with additional controls (Tables A17–A18). When employing the more plausible indices multiplying contestation with either freedom of expression or legislative constraints, exploiting variations in these conditions within regimes with contestation, we find similar conditional relationships as shown in our main results (Tables A19–A20). This reassures us that the contestation–suffrage interaction is not an artefact of other democracy‐aspects related to contestation.

Next, we run analyses only on executive election spells. These analyses show quite different results, but it should be noted that the number of countries included in some of the analyses is cut in half (Tables A21–A23). Adding all executive elections to the original legislative elections set naturally increases the number of observations. However, it also means that spells become very short in presidential systems. Reassuringly, the results are similar to the ones presented with only legislative elections (Tables A24–A26). This remains the case when we use the Fariss et al. (Reference Fariss, Crabtree, Anders, Jones, Linder and Markowitz2017) GDP per capita data, which increases the number of observations (Table A27).

To get a more accurate estimation of how governments are appointed, we combine executive and legislative elections, but only include spells on the basis of legislative elections if approval of the legislature is necessary for the appointment of the head of government (Tables A28–A30). We use the indicator ‘HOG selection by legislature in practice’ from V‐Dem for deciding whether this is the case (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Hicken, Hindle, Lührmann, Maerz, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Paxton and Ziblatt2021b, p. 131). The result for the interaction (pre‐1939), plotted in Figure A4, is similar to the main result. Using the Fariss et al. (Reference Fariss, Crabtree, Anders, Jones, Linder and Markowitz2017) data on GDP per capita strengthens the conditional relationship for the earlier period in the base model (at p < 0.05), and it even becomes significant (at p < 0.1) with additional controls (Table A31).

In sum, higher suffrage levels are negatively related to meritocracy and weaken the positive relationship between contestation and meritocracy before World War II when variation in suffrage was large. It should be noted that across our models, suffrage and contestation lose significance as additional controls are added, which indicates the importance of traditional factors such as human capital and international warfare.Footnote 5 Contestation and suffrage are not the only factors that may explain meritocracy levels. However, even in our highly restricted models, the diverging relationships of suffrage and contestation with meritocracy are evident. This is evidence that different dimensions of democracy stand in different relationships with bureaucracy. Further, as the results hold when controlling for GDP per capita, they provide indicative evidence of our mechanism that mean income of the median voter rather than the population drives politicians’ decisions to increase clientelism.

Conclusion

This paper engages with a large literature, which has shown disparate findings on the relationship between democracy and bureaucracy. Our paper reconciles these findings by disaggregating democracy. Rather than equating democracy with electoral contestation, we add the dimension of inclusiveness. We argue that contestation makes politicians more responsive to demands from the electorate rather than the population at large, and that voters’ demands vary depending on the degree of socioeconomic restrictions on suffrage. As poorer people are enfranchised, the electorate is more likely to demand particularistic goods. Therefore, in contexts of electoral contestation, higher suffrage levels incentivize politicians to engage in clientelist practices, which is detrimental to bureaucratic development.

The paper uses new data on the degree of meritocracy together with data on contestation and male suffrage, from different sources, to examine the impact of the two dimensions of democracy on bureaucratic development in different time periods. The results support our theory, showing that male suffrage is negatively related to meritocracy and decreases the positive relationship between contestation and meritocracy before World War II, whereas contestation is only positively related to meritocracy after 1938. This suggests that we need to examine also time periods when suffrage varied substantially within and between countries in order to fully appreciate the relationship between democracy and bureaucracy.

The results are robust to including previous levels of meritocracy, which partly remedy reverse causality. Although bureaucratic development is likely to be path dependent and positively affect democracy, our results still show that suffrage levels weaken the positive relationship between contestation and meritocracy in the pre‐1939 period.

The results do not only provide a historical corrective, but also deepen our general understanding of the relationship between democracy and bureaucratic development. Supporting long‐held theories, our analysis suggests that clientelism is a likely result of democracy with a poor electorate. Future research should therefore distinguish between democratization as competition for political power and democratization as enfranchisement of the masses. To this end, future research would benefit from case‐studies providing more detailed accounts of the impact of socioeconomic suffrage extensions on bureaucratic development.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for valuable comments from the three anonymous reviewers, the editors of the European Journal of Political Research, Svend‐Erik Skaaning, Jan Teorell, Hanna Bäck, as well as participants at the STANCE lunch seminar, Department of Political Science, Lund University, September 16, 2020; the workshop on “The Progress and Decline of Democracy outside the West” at NOPSA's XVIII 2017 Political Science Congress, August 8‐11, 2017, University of Southern Denmark; the panel on “Consequences of Democracy” at the V‐Dem Academic Research Conference May 28‐29, 2018, University of Gothenburg; and the STANCE workshop, August 24‐25, 2017, Lund University.

Funding Information

Riksbankens jubileumsfond, Grant Number: M14‐0087:1 (Agnes Cornell).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supplementary material