Impact statement

Urban water systems are under growing pressure from climate change, ageing infrastructure and increasing demand. This article shows how generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), particularly large language models, can be used to address these challenges, offering tools that can transform how water utilities plan, operate and maintain their assets. The work has wide-reaching implications for the water sector. By integrating GenAI into daily operations, utilities can improve the reliability and efficiency of their services through faster decision-making, predictive maintenance and enhanced communication with customers. GenAI tools can help staff diagnose problems, optimise resources and respond quickly to emergencies, even when data are incomplete or conditions are uncertain. They can also preserve valuable organisational knowledge and deliver tailored training, helping to address skills shortages and support workforce transitions. Beyond operational benefits, the study tackles critical issues of trust, safety and fairness in AI use for essential public services. It identifies risks, such as bias, data security and over-reliance on automated outputs, and offers practical recommendations to ensure that AI is applied responsibly. This guidance is relevant not only for engineers and managers in water utilities, but also for policymakers, regulators and technology developers. The findings have significance outside the water industry, as the lessons on integrating GenAI into complex, safety-critical infrastructure can inform other sectors, such as energy, transport and healthcare. By highlighting both the opportunities and challenges, the study encourages a balanced approach to AI adoption, ensuring that the technology strengthens resilience, reduces environmental impacts and delivers equitable benefits for communities. In short, this research provides a roadmap for safely unlocking the potential of GenAI in managing vital infrastructure, with benefits that extend well beyond the water sector.

Introduction

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), particularly large language models (LLMs), such as well-known ChatGPT, has emerged as a transformative technology across multiple industries. These models, powered by advanced deep learning techniques, can process and generate human-like text, and when integrated with speech recognition and text-to-speech systems, they enable speech-to-speech capabilities through intelligent GenAI-powered voice agents. This allows for automation, decision support and enhanced data analysis (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Acosta and Rajpurkar2025). Initially popular in creative fields and customer service, GenAI is now finding applications in healthcare, finance, legal research and engineering, demonstrating its versatility and potential to revolutionise various sectors.

While this article focuses on GenAI, it is important to distinguish it from agentic AI. GenAI refers to models that create new content, such as text, code, images or audio, with LLMs being a key example specialised in natural language generation and understanding. Agentic AI describes systems that can perceive, decide and act autonomously towards defined goals. These agents can be non-generative, such as reinforcement learning and model predictive controllers, or rule-based automation that performs actions without creating new content. Generative agents, on the other hand, combine decision-making capabilities with the ability to produce new outputs (Schneider, Reference Schneider2025).

In recent years, the capabilities of GenAI have expanded to include real-time data processing, predictive analytics and natural language understanding, making it an invaluable tool for complex decision-making and operational management (Darreddy, Reference Darreddy2025). The integration of AI in infrastructure sectors, such as transportation, energy and water management, is particularly promising, as these fields require efficient, data-driven strategies to address evolving challenges. As urban populations grow and demand for resilient infrastructure intensifies, AI-driven solutions are no longer optional but essential.

Managing urban water systems is a multifaceted challenge, encompassing water supply, distribution, wastewater treatment and flood management. These systems must operate efficiently while adapting to climate change, population growth and ageing infrastructure. Traditional methods of monitoring and maintaining urban water systems often rely on manual inspections, historical data and deterministic models, which can be time-consuming and prone to inaccuracies.

GenAI offers a significant potential to enhance urban water system management through real-time analysis, predictive modelling and automated decision support. By processing vast amounts of data, AI models can identify patterns, predict failures, optimise resource allocation and improve communication between stakeholders. From assisting engineers in developing adaptive water management strategies to providing early warnings for potential disruptions, GenAI has the potential to significantly enhance resilience and efficiency in urban water systems (Taiwo et al., Reference Taiwo, Yussif and Zayed2025).

This article aims to explore the role of GenAI models, particularly LLMs, such as ChatGPT, in the management and operation of urban water systems. It will examine the potential applications of AI in areas such as predictive maintenance, demand forecasting, emergency response and regulatory compliance. Additionally, the article will highlight the benefits of AI-driven approaches, including improved efficiency, cost reduction and enhanced decision-making capabilities.

Nonetheless, the implementation of GenAI in this context is not without challenges. Issues such as data privacy, model reliability and integration with existing water management systems present significant hurdles that must be overcome to fully realise AI’s potential. This article will also discuss these challenges and propose future directions for research and implementation, offering a comprehensive perspective on how GenAI can shape the future of urban water systems.

Current state of urban water systems management

Monitoring

Urban water systems management has traditionally relied on a combination of manual monitoring, supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems and deterministic modelling approaches. SCADA systems allow operators to collect data from remote sensors and control water distribution networks, treatment plants and pumping stations in real time. Additionally, manual inspections and laboratory testing remain essential components of water quality assessment and infrastructure maintenance.

Planning and management

The operation and management of urban water systems typically occur across multiple layers, including strategic planning, operational control and emergency response. Strategic planning involves long-term investment in infrastructure and resource allocation, while operational control focuses on daily monitoring and maintenance activities. Emergency response addresses system failures, extreme weather events and contamination incidents, requiring rapid decision-making and coordination among stakeholders.

Despite advancements in technology, many utilities still depend on historical data and rule-based decision-making processes, which may not adequately address the complexities of modern urban water management. The integration of real-time data analytics and predictive modelling remains limited in many regions, leading to inefficiencies and increased operational risks (Rousso et al., Reference Rousso, Do, Gao, Monks, Wu, Stewart, Lambert and Gong2024).

Ageing infrastructure

Several challenges hinder the effective management of urban water systems, necessitating the exploration of advanced technological solutions. One of the primary challenges is ageing infrastructure, with many water distribution networks and treatment facilities exceeding their intended lifespan. The deterioration of pipes, pumps and storage tanks leads to frequent leaks, water loss and contamination risks, requiring costly repairs and replacements (Sowby et al., Reference Sowby, Hall, Peterson, Dwiggins, Ball and Oldham2025).

Limited resources

Resource management is another pressing concern, particularly in regions experiencing water scarcity and increasing demand. Balancing supply and demand while ensuring equitable distribution presents significant operational difficulties. Climate change further exacerbates these challenges by introducing unpredictable weather patterns, such as prolonged droughts and intense rainfall events, which can overwhelm existing infrastructure (Ferdowsi et al., Reference Ferdowsi, Piadeh, Behzadian, Mousavi and Ehteram2024).

Regulation

Regulatory compliance adds another layer of complexity to urban water management. Utilities must adhere to stringent water quality standards, environmental regulations and reporting requirements, which demand continuous monitoring and documentation. Failure to comply can result in legal penalties, reputational damage and public health risks.

Fragmented data sources

Fragmentation of data across different departments and legacy systems limits the ability of water utilities to develop holistic, data-driven management strategies. Many existing models and tools operate in silos, preventing seamless data integration and cross-sector collaboration (Kee, Reference Kee2025).

These operational challenges highlight the need for innovative approaches, such as GenAI, to enhance decision-making, predictive capabilities and overall efficiency in urban water systems management. The following sections will explore how AI-driven solutions can address these issues and transform the future of urban water management.

Potential applications of GenAI models

Operational support

GenAI models can serve as real-time decision-support tools in urban water system operations. By processing large volumes of structured and unstructured data, these models can assist operators in troubleshooting issues, optimising system performance and generating recommendations for routine and emergency scenarios. AI-powered virtual assistants can guide staff through step-by-step procedures for tasks such as leak detection, pump maintenance and water quality testing, reducing reliance on human expertise and minimising response times. Additionally, AI-based models can integrate with existing SCADA systems to perform inference, enable AI-human interaction, and produce more insightful and interpretable outputs. They can provide automated alerts and insights, enabling proactive decision-making and improving overall system efficiency. For instance, in the event of a sudden drop in reservoir levels, AI can assist in diagnosing causes such as valve failures, unauthorised consumption or sensor errors. In energy-intensive systems, it can recommend adjusted pump schedules based on tariff structures or real-time demand patterns. AI agents can autonomously run simulation models, like Environmental Protection Agency Network (EPANET), based on the current situation or test the system’s reliability against scenarios generated by both agents and human experts. They can also simulate contamination spread following a pipe burst or backflow incident, guiding immediate response actions. The results can then be comprehensively interpreted and communicated using GenAI models, such as LLMs. This capability not only enhances operational preparedness but also supports a more dynamic and adaptive approach to system management.

Data analysis and predictive modelling

Unlike classical Machine Learning (ML) models, which typically require structured inputs and predefined feature sets, GenAI models can interpret both structured and unstructured data. This includes text-based reports, logs and sensor readings. As a result, they can uncover insights and contextual patterns that traditional models may overlook. GenAI can assist in anomaly detection, such as unexpected fluctuations in flow or pressure, by reasoning through natural language inputs or combining diverse data sources. For example, it can cross-reference SCADA readings with recent maintenance reports to detect inconsistencies or flag deviations in water quality trends after a storm event. It can also process inspection logs to identify recurring faults across different asset types or locations. While classical ML excels at precise forecasting based on historical patterns, generative models offer greater flexibility in generating explanatory narratives, proposing hypotheses or supporting decision-making in uncertain or data-sparse scenarios. They can simulate asset behaviour in hypothetical stress conditions or provide risk summaries based on partial data and expert input. However, they may be less transparent in their reasoning and require careful validation, especially when applied to critical infrastructure.

Customer service and communication

Water utilities often handle a high volume of customer inquiries related to billing, service disruptions and water quality concerns. GenAI can streamline customer service operations by providing instant, accurate and consistent responses through chatbots and virtual assistants. For instance, AI can answer queries about water hardness, explain charges on customer bills or guide users through reporting a leak via a self-service portal. AI-driven systems can also assist in drafting notifications and advisories during emergencies, ensuring clear and timely communication with customers. They can automatically generate location-specific boil water notices or service restoration updates based on real-time system data. Continuous monitoring of social media can enable utilities to detect incidents at an early stage, assess customer dissatisfaction and obtain timely feedback. For example, a sudden spike in complaints about discoloured water from a specific postcode on social media can trigger immediate investigation or targeted messaging. By reducing the workload on customer service teams, AI enables human representatives to focus on complex issues requiring personalised attention.

Training and knowledge transfer

Knowledge retention and staff training are critical in the water sector, where expertise is often lost due to workforce turnover and retirements. This challenge is particularly acute in small utilities, such as those in the United States and other countries with a high number of municipally run systems, where limited staffing and technical expertise make effective training and knowledge transfer even more essential. GenAI can function as a knowledge repository, storing institutional knowledge and making it accessible through natural language queries. Training these models on internal documents and open-access publications can further enhance their ability to support utility personnel, enabling quick access to relevant guidance and technical insights. AI-powered training modules can simulate real-world scenarios, allowing new employees to gain hands-on experience in system operations and emergency management. Additionally, AI can generate customised training materials and technical documentation, ensuring that staff remain well-informed about best practices and regulatory requirements.

Benefits of integrating GenAI models in water system operations

Increased efficiency

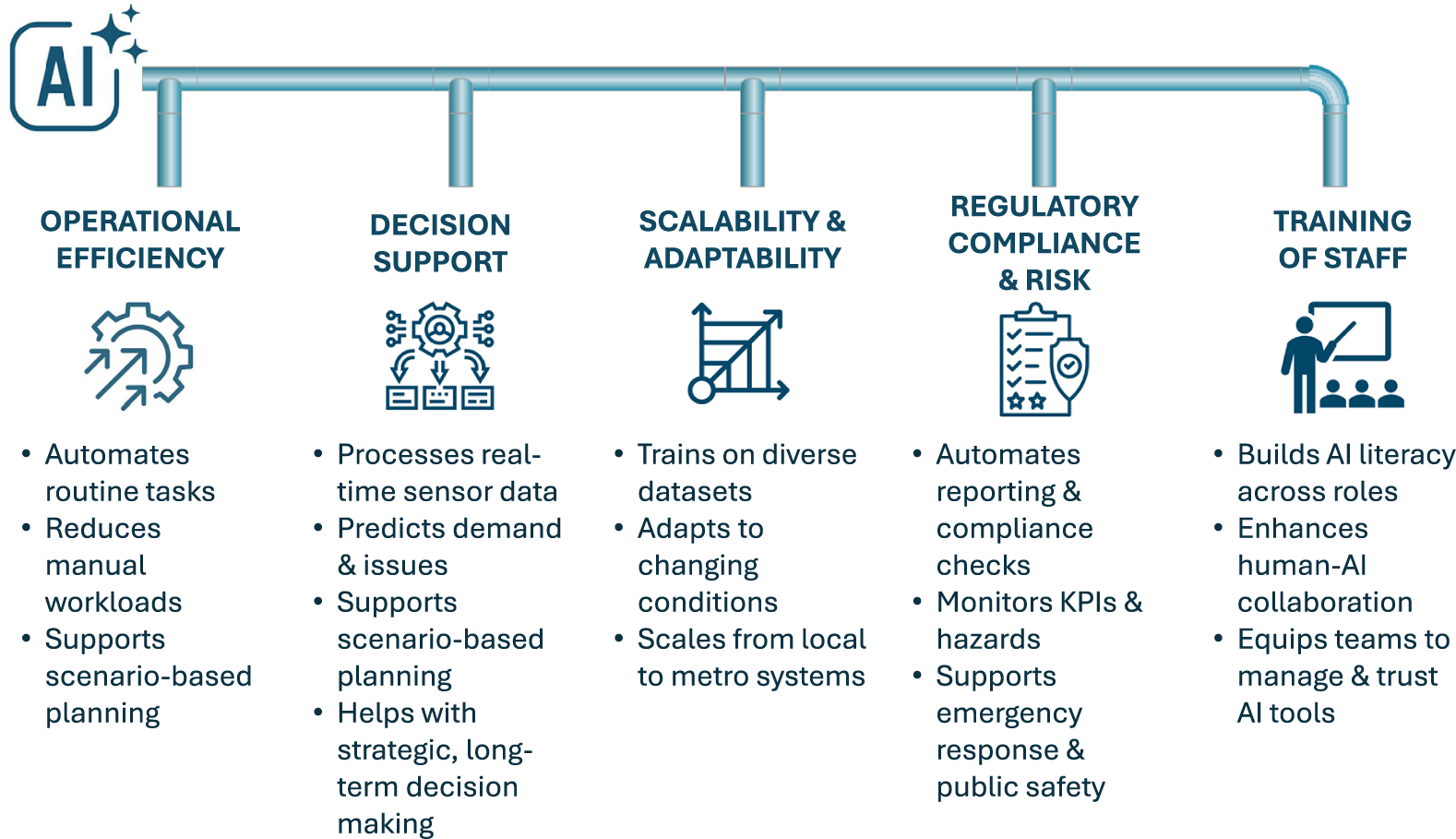

GenAI models can significantly enhance efficiency in urban water system operations by automating routine tasks, reducing manual workloads and optimising resource allocation. By leveraging AI-driven analytics, utilities can streamline data processing, automate report generation and enhance workflow management. This reduces the need for excessive human intervention in repetitive activities, allowing staff to focus on higher-value tasks such as strategic planning and emergency response. Integrating simulation runs with optimisation routines, AI can identify inefficiencies in water distribution networks. For example, it can reduce energy consumption by optimising pump and air compressor schedules in treatment works, as well as addressing water quality problems (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Benefits of integrating GenAI models in water systems.

Autonomous code generation

GenAI also offers a less frequently discussed but highly impactful capability: generating computer code to solve planning and operational problems in water systems. This allows AI to go beyond analysis and decision support by contributing directly to the development of technical solutions. For example, GenAI agents can be applied to optimise pump operations within a distribution network, where the agent autonomously writes and refines code to simulate different operating scenarios or implement energy-saving strategies. This capability significantly reduces development time for modelling tasks, supports rapid prototyping and enables utilities to test and deploy operational strategies more efficiently, particularly in resource-constrained environments.

Improved real-time decision-making

AI-driven models improve decision-making by providing data-driven insights and scenario-based analysis. These models can assist operators by processing real-time data from sensors, identifying patterns and offering predictive recommendations to mitigate potential issues before they escalate. For example, AI can analyse historical trends to anticipate water demand fluctuations, enabling proactive resource allocation. In operational contexts, AI can support dynamic pressure management by adjusting valve settings or pump operations in real time to minimise leakage and energy use. During contamination events or infrastructure failures, AI can simulate different emergency response scenarios to help operators select the most effective course of action. Additionally, in planning scenarios, non-generative AI agents can run simulation models to test the system’s reliability under both anticipated and extreme conditions. These simulations may be initiated autonomously by AI or collaboratively designed with human experts. Decision-makers can also use GenAI recommendations to prioritise capital investments, evaluate alternative network configurations or optimise long-term asset replacement schedules. This level of support enhances both day-to-day operations and strategic planning, increasing system resilience and service reliability.

Improved scalability and flexibility

Urban water systems must adapt to uncertain population changes, climate variability and evolving regulatory requirements. AI technologies, including GenAI and agentic AI, provide both scalability and flexibility, not only in day-to-day operations but also in long-term planning and system design. As physical infrastructure is inherently rigid and slow to adapt, AI can support more agile decision-making by enabling flexible planning and operational strategies. AI offers scalability to meet growing demands, while also allowing water utilities to explore adaptive solutions that account for uncertainty, future growth and long asset lifespans. For instance, reinforcement learning agents can be applied to develop adaptation pathways for water distribution systems that remain robust under a range of future scenarios. This flexibility is particularly valuable when planning infrastructure expected to operate for over a century, where traditional methods may struggle to accommodate deep uncertainty and evolving needs.

Better regulation compliance

Ensuring compliance with stringent water quality and environmental regulations is a critical aspect of urban water management. AI models can support regulatory compliance by automating data collection, monitoring key performance indicators and generating compliance reports. AI can also enhance safety by identifying potential hazards, such as contamination risks or infrastructure vulnerabilities, and providing early warnings to operators. Furthermore, AI-powered risk assessment tools can support emergency response planning, helping utilities develop proactive mitigation strategies to safeguard public health and environmental integrity.

Challenges and risks

The integration of GenAI into urban water systems management brings several challenges and risks that must be addressed to ensure secure and effective implementation. These challenges range from data security concerns to regulatory complexities, each requiring careful consideration and mitigation strategies.

Cybersecurity

One of the primary concerns is data security and privacy. Water utilities handle vast amounts of sensitive information, including operational data, customer details and infrastructure vulnerabilities. The adoption of AI introduces risks related to data breaches, unauthorised access and cyber threats. AI models rely on large datasets for training and continuous improvement, raising concerns about data storage, sharing and compliance with data protection regulations. Without robust cybersecurity frameworks, encrypted communications and strict access controls, the deployment of AI in critical water infrastructure could become a target for malicious actors, jeopardising system integrity and public safety.

Errors and hallucinations

Another key challenge is ensuring the accuracy and reliability of AI-generated outputs. While AI can process large datasets and identify patterns, it is not infallible. Errors, non-sensical or even fabricated results (“hallucinations”) and misinterpretations can occur, leading to incorrect recommendations or flawed decision-making.

Sensor redundancy

A significant challenge in urban water systems is the lack of sensor redundancy, which undermines data reliability and operational resilience. Unlike sectors such as automotive and aerospace, where redundant sensors are standard practice to ensure safety and system robustness, the water industry often relies on sparse sensor networks with limited fallback options. In safety-critical systems, redundancy is essential; if one sensor fails, another should take over to maintain continuity. The absence of such backup increases vulnerability to data gaps, misinterpretation and delayed responses during failures. Improving sensor density and incorporating redundancy would enhance data quality, reduce uncertainty and provide a more reliable foundation for AI-driven decision-making and automation.

Interpretability

A key concern with the use of LLMs in critical infrastructure is their limited interpretability. These models often function as opaque black boxes, where it is unclear how specific outputs or recommendations are derived. This lack of transparency undermines trust in the system, particularly when decisions have safety, financial or regulatory implications. Without clear explanations of the reasoning behind an AI-generated response, operators may struggle to assess its validity or relevance. Improving model interpretability and developing explainable AI tools are essential steps to ensure responsible and trustworthy adoption of generative AI in urban water systems.

Human in the loop

AI-generated insights must be validated by human experts to prevent unintended operational consequences. Additionally, water systems operate in dynamic and often unpredictable environments where real-time conditions may not always align with AI predictions. Over-reliance on AI without human oversight could result in misguided actions, making it essential to implement robust validation mechanisms and integrate AI as a support tool rather than a standalone decision-maker. It is also critical to maintain manual backup options, allowing human operators to intervene when necessary, particularly in high-stakes or emergency situations. As AI becomes more integrated into operations, concerns about job displacement are natural. However, rather than eliminating roles, AI is likely to change them. Staff will require new training to work alongside AI systems, interpret outputs and make informed decisions based on them. This transition underscores the need for workforce development and upskilling programmes to ensure that human expertise continues to guide and complement AI safely and effectively.

Ethics, bias and fairness

The ethical and social implications of AI adoption in urban water management also require careful examination. AI models can unintentionally inherit biases present in training data, potentially leading to inequitable outcomes. For example, if historical investment patterns have overlooked low-income or marginalised communities in flood risk management, AI may perpetuate these inequalities by prioritising areas with more infrastructure or better data availability. This raises important concerns about fairness and social justice in the deployment of AI. Furthermore, the automation of certain tasks may raise concerns about workforce displacement and job security. Water utilities must strike a balance between leveraging AI for efficiency gains and ensuring that human expertise remains integral to operations. Transparent AI governance, ethical guidelines and stakeholder engagement are crucial to addressing these concerns and fostering public trust in AI-driven water management solutions.

Computational cost and sustainability

Training and running AI systems require massive computational resources, leading to high costs and a significant environmental impact. For example, the energy and water consumption of AI and data centres are a growing concern, raising questions about their long-term sustainability.

Framing

Framing plays a crucial role in how new technologies are received, and this is especially true for GenAI in the water sector. Just as companies like Tesla have successfully redefined electric vehicles by presenting them as part of a lifestyle, water professionals must frame GenAI in a way that highlights its tangible benefits. Clearly communicating how AI can improve reliability, efficiency and responsiveness will help build trust among stakeholders and consumers. Using accessible, positive language and real-world examples, professionals can ensure that ratepayers, regulators and utility staff understand the value of digital transformation and feel included in the journey.

AI’s rapid progress versus regulatory gridlock

Regulatory and legal considerations present another layer of complexity. The deployment of AI in urban water systems must align with existing water governance frameworks, environmental regulations and data protection laws. However, AI technologies are evolving rapidly, often outpacing regulatory developments. This creates uncertainty regarding liability in cases of AI-induced errors or failures. Additionally, compliance with international and national water management standards may require utilities to demonstrate AI model transparency, explainability and accountability. Questions around intellectual property and ownership of both input data and AI-generated outputs, particularly when derived from copyrighted or proprietary materials, further complicate the legal landscape. Establishing clear regulatory frameworks, industry guidelines and legal safeguards will be essential to ensuring responsible AI adoption in critical infrastructure sectors.

Addressing these challenges requires a multi-faceted approach, combining technological advancements, policy development and human oversight. While GenAI holds immense potential for transforming urban water systems management, its success hinges on careful risk mitigation, ethical considerations and adherence to stringent security and regulatory standards. This is especially important given the current hype surrounding the technology and the involvement of commercial actors, whose business models may incentivise overstating benefits while overlooking limitations and risks.

Case studies and real-world examples

In operational support, several real-world examples illustrate how GenAI enhances system performance. Veolia and Mistral AI introduced a conversational co-pilot into more than 3,800 drinking water and 3,200 wastewater treatment plants, allowing operators to query site-level data using natural language and improving transparency and responsiveness (Smart Water Magazine, 2023). Siemens’ Industrial Copilot, developed in collaboration with Microsoft, supports SCADA interpretation, maintenance guidance and control code generation. It integrates with platforms such as Siemens Senseye and Xcelerator, and has been adapted to the water sector (Siemens, 2025a, 2025b). Qatium’s “Q” assistant provides operators with step-by-step support for building and managing water network models, enabling scenario analysis and operational planning in real time (Qatium, 2025). Additionally, a recent framework demonstrates the integration of LLMs with EPANET, allowing users to interact with hydraulic simulation models via natural language (Goldshtein et al., Reference Goldshtein, Perelman, Schuster and Ostfeld2025). GenAI is also being proposed for digital twin applications, including three-dimensional environment synthesis and resilience forecasting (Rajendran, Reference Rajendran2024).

For data analytics and predictive modelling, GenAI offers new capabilities for uncovering trends, forecasting outcomes and generating synthetic data. WaterGPT, a bilingual LLM developed specifically for hydrological applications, processes text and image inputs to support modelling and analysis tasks (Ren et al., Reference Ren, Zhang, Dong, Li, Wang, He, Zhang and Jiao2024). Benchmarking by Xu et al. found that WaterGPT significantly outperformed other models on engineering and research challenges (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Li, Yang, Wu, Wang, Tang, Li, Wu, Su, Shi, Yang, Tong, Wen and Ng2025). In regions with limited historical data, generative adversarial networks (GANs) are being used to produce synthetic rainfall and flow records for overflow prediction (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Li, Yang, Wu, Wang, Tang, Li, Wu, Su, Shi, Yang, Tong, Wen and Ng2025). Vassar Labs’ aquaMIND platform combines SCADA integration with AI-driven predictive alerts and contextual analytics for operational risk reduction (AquaMIND, 2025). In the visual domain, Progressive Growing Generative Adversarial Network (PGGAN) has been applied to generate high-resolution river imagery to support hydrological assessments and training (Gautam et al., Reference Gautam, Sit and Demir2022). Smaller utilities are also applying generative models to assist with leak detection, non-revenue water reduction and accessible data querying for non-specialists (Balassiano et al., Reference Balassiano, Gu and Taqi2025).

In customer service and communication, utilities are deploying GenAI to automate and improve engagement with the public. Chatbots developed by SEW and Robofy handle high volumes of customer requests related to billing, service disruptions and water quality. The city of Midland in Texas has implemented Ask Jacky, an AI chatbot that answers resident queries about public services and illustrates how similar tools could be applied in utility contexts (Dias, Reference Dias2025). Qatium has proposed using GenAI to link consumer complaints to operational data. For example, if a customer reports discoloured water, the system can access relevant sensor data to generate a meaningful explanation or alert (Qatium, 2025). UWE Bristol’s Sustain WaterBot aims to help SMEs adopt sustainable practices in response to climate and population pressures (UWE Bristol, 2025).

In training and knowledge transfer, GenAI supports knowledge preservation and workforce development. The Genius platform, developed by (KWR Watercycle Research Institute), enables staff to explore complex hydroinformatics tools through human-centred AI interactions, supporting continuity as experienced personnel retire or move on (Pronk et al., Reference Pronk, Clevers and von Thienen2024). UrbanKGent is another LLM-based system that constructs knowledge graphs from fragmented technical documents, allowing new employees to explore institutional knowledge using natural language queries (Ning and Liu, Reference Ning and Liu2024). Finally, the Arizona Water chatbot, although developed for public outreach, demonstrates how retrieval-augmented models can be adapted to deliver internal training and operational support (WEF, 2025).

Future directions and recommendations

The transformative potential of GenAI in urban water system management is significant, yet its responsible and effective adoption requires continued innovation, informed policymaking and strategic integration. Looking ahead, it is crucial to identify key areas where development efforts should be concentrated, while ensuring alignment with ethical, legal and operational standards.

First, there is a pressing need for further research and development to enhance the performance and reliability of GenAI models in water-related applications. While these models can analyse vast datasets and assist in decision-making, improving their accuracy in specific engineering contexts remains essential. Research should focus on fine-tuning GenAI tools for interpreting hydraulic, hydrological and asset management data, reducing susceptibility to bias and misinterpretation. Additionally, efforts are needed to facilitate seamless integration with existing digital infrastructure, including SCADA systems, GIS platforms and mathematical optimization and hydraulic models. Domain-specific training and benchmarking datasets would help improve contextual relevance, while advances in hybrid AI frameworks could combine the strengths of generative models with physical-based models to enhance trust and applicability in critical scenarios.

From a policy and regulatory perspective, clear and enforceable guidelines are required to support the safe and ethical use of GenAI in urban water systems. Policymakers should establish standards around data governance, AI transparency and accountability. Data protection regulations must be updated to address AI-specific risks, ensuring that customer data, system performance metrics and infrastructure vulnerabilities are securely handled. Additionally, certification schemes or independent audits may be introduced to evaluate the performance and reliability of AI systems used in critical infrastructure, thereby ensuring alignment with public safety and environmental objectives.

To realise the benefits of GenAI, water system managers must adopt thoughtful integration strategies. This begins with pilot projects that allow utilities to test AI capabilities on a smaller scale, assess outcomes and develop institutional experience. Importantly, AI should complement, not replace, human expertise. Operators, engineers and analysts must be trained to work alongside AI tools, interpreting recommendations and applying domain knowledge to make final decisions. Addressing complex and interconnected water challenges requires professionals who are fluent in both water systems and AI. Initiatives like the Centre for Doctoral Training in Water Informatics: Science and Engineering (University of Exeter, 2025; Wagener et al., Reference Wagener, Savic, Butler, Ahmadian, Arnot, Dawes, Djordjevic, Falconer, Farmani, Ford, Hofman, Kapelan, Pan and Woods2021) exemplify the importance of interdisciplinary training, as AI expertise alone is not sufficient to tackle the ‘wicked’ problems facing the water sector. Organisational change management, inclusive training programmes and clear communication about the role of AI will be essential to foster acceptance and adoption. Strategic partnerships with AI developers and academic institutions can also accelerate knowledge transfer and innovation, ensuring that water utilities are equipped to harness the full potential of GenAI in building more resilient, efficient and adaptive urban water systems.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/wat.2025.10008.

Data availability statement

All data used have been presented in the article.

Author contribution

ML, RB and DS contributed to conceptualization. ML and RB were responsible for writing – original draft, while DS contributed to writing – review and editing. ML carried out the visualisation. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support

Dragan Savic has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement number [951424]).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Disclaimer

The literature review above relies primarily on the creators’ claims regarding the capabilities of their solutions, without independent evaluation or validation by the authors.

Comments

Dear Editors,

I am pleased to submit our manuscript entitled “GenAI Models for Urban Water Systems: Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Directions” for consideration for publication in Cambridge Prisms: Water.

This paper explores the transformative potential of generative artificial intelligence, particularly large language models, in the management and operation of urban water systems. We present a comprehensive review of current applications, benefits, and emerging case studies, while also addressing key challenges such as data privacy, interpretability, and regulatory uncertainty. The paper offers forward-looking recommendations for research, policy, and practice, and aims to support the responsible integration of GenAI into urban water infrastructure.

We believe this work is particularly suited to Cambridge Prisms: Water due to its interdisciplinary scope, practical implications, and timely relevance to both digital water innovation and sustainable urban development. The paper is intended to engage researchers, practitioners, and policymakers seeking to understand how advanced AI tools can improve resilience, efficiency, and decision-making in the water sector.

We confirm that the manuscript is original, has not been published previously, and is not under consideration elsewhere. All authors have approved the manuscript and agree with its submission to Cambridge Prisms: Water.

Thank you for considering our work. We look forward to the opportunity to contribute to your journal.

Kind regards,

Ramiz Beig Zali (corresponding author); Milad Latifi; Dragan Savic

Centre for Water Systems, University of Exeter

Rb815@exeter.ac.uk