Interstate conflict is rare, but, in larger parts, it is not because states strike bargains over disputes and thus avoid the associated costs (Fearon Reference Fearon1995; Gartzke and Lindsay Reference Gartzke and Lindsay2024; Huth Reference Huth1999), but because they have no serious dispute (Acharya and Lee Reference Acharya and Lee2018; Reference Acharya and Lee2022). Among 2,519 “politically relevant” dyads from 1946 to 2001 available in the Issue Correlates of War dataset (ICoW; Frederick, Hensel, and Macaulay Reference Frederick, Hensel and Macaulay2017; Hensel et al. Reference Hensel, Mitchell, Owsiak and Wiegand2025; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2020),Footnote 1 only 1.6% had military conflicts, such as military threats, displays, clashes, and wars. Among 98.4% of the observations with no military conflicts, only 4.0% had disputes in the ICoW dataset, and 96.0% had no disputes.Footnote 2 Apparently, most states did not fight because they had no serious dispute.

These stylized facts highlight a crucial but oft-neglected aspect of peace: the absence of dispute. While many studies have addressed this issue by subsampling to “politically relevant” or contiguous dyads (Braumoeller and Carson Reference Braumoeller and Carson2011; Mitchell and Prins Reference Mitchell and Prins1999; Reed and Chiba Reference Reed and Chiba2010; Senese Reference Senese2005; Vasquez Reference Vasquez1995), other studies have theoretically and empirically analyzed why states dispute in the first place (Acharya and Lee Reference Acharya and Lee2018; Reference Acharya and Lee2022; Frederick, Hensel, and Macaulay Reference Frederick, Hensel and Macaulay2017; Goertz and Diehl Reference Goertz and Diehl1995; Hensel et al. Reference Hensel, Mitchell, Sowers and Thyne2008; Hensel and Mitchell Reference Hensel and Mitchell2005; Toft Reference Toft2014). They examine the roles of power balance (Schultz and Goemans Reference Schultz and Goemans2019), alliances (Gibler Reference Gibler1997), economic interdependence (Lee and Mitchell Reference Lee and Mitchell2012), strategic and economic interests (Lee Reference Lee2024; Schultz Reference Schultz2017), and domestic politics (Altman and Lee Reference Altman and Lee2022; Gibler Reference Gibler2007; Hutchison and Gibler Reference Hutchison and Gibler2007; Markowitz et al. Reference Markowitz, Mulesky, Benjamin and Fariss2020; Tir Reference Tir2010) among many other factors.

Although all those factors are important, the studies tend to dismiss the critical roles of international norms (Forsberg Reference Forsberg1996). While Castile and Portugal claimed the entirety of the Earth and signed the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, the European powers disputed and partitioned Africa in 1884, and similar attempts were made for China in the early twentieth century, those actions are even unimaginable in the present world. Such a drastic change cannot be explained without referring to the emergence of anti-colonialism and territorial integrity norms after the world wars (Altman Reference Altman2020; Altman and Lee Reference Altman and Lee2022; Zacher Reference Zacher2001).

Thus, following the emerging literature on territorial norms,Footnote 3 I ask two questions of claimability; (i) What makes certain territorial claims appropriate while making others inappropriate? (ii) What escalates those potential claims and disputes into militarized interstate conflicts? Although claimability can be defined for any claim, I focus on territorial claims—claims over terrestrial lands and waters. A territory is claimable if a state can claim a territory according to international norms such as international laws, practices, and customs. A territory is disputable if it is claimable by more than one state.

I address question (i) by focusing on three sets of international norms: territorial integrity (i.e., claims over territorial lands; Abramson and Carter Reference Abramson and Carter2016; Reference Abramson and Carter2021; Altman Reference Altman2020; Carter Reference Carter2017; Carter and Goemans Reference Carter and Goemans2011; Reference Carter and Goemans2014; Zacher Reference Zacher2001), self-determination and minority protection (i.e., claims over foreign co-ethnicities; Cederman et al. Reference Cederman, Pengl, Girardin and Müller-Crepon2024; Goemans and Schultz Reference Goemans and Schultz2017; Müller-Crepon, Schvitz, and Cederman Reference Müller-Crepon, Schvitz and Cederman2025; Siroky and Hale Reference Siroky and Hale2017), and sovereignty over marine areas (i.e., claims over territorial water, continental shelves, and exclusive economic zones; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2020; Yüksel Reference Yüksel2024). Based on those norms, I code the geographical extent of the claimable and disputable areas globally from 1946 to 2024.

I demonstrate the usefulness of the new dataset by applying it to the analysis of fuel discoveries and interstate conflict, thereby addressing question (ii). Although claimability reduces subjective costs for making a claim and hence may increase military conflicts as well, not all claims or disputes escalate into military conflicts. Claimability changes only occasionally, and states tend to make claims for years (Frederick, Hensel, and Macaulay Reference Frederick, Hensel and Macaulay2017), but military conflicts occur in specific periods.Footnote 4 Although the timing of escalation can be explained by various factors such as domestic (Tir Reference Tir2010) and systemic instability (Abramson and Carter Reference Abramson and Carter2021), fuel discoveries are particularly illustrative as they have explicit dates and locations, allowing me to analyze when and which states fight for which oil/gas fields.Footnote 5

I thus argue that the presence of disputable areas creates a potential for interstate disputes, and the fuel discoveries in the disputable areas escalate them into military conflicts. Based on theoretical studies, I posit two mechanisms of escalation: tangible and intangible salience (Hensel et al. Reference Hensel, Mitchell, Sowers and Thyne2008; Hensel and Mitchell Reference Hensel and Mitchell2005; Toft Reference Toft2014). First, without resolving potential disputes, states cannot safely utilize the resources in disputable areas. Then, states initiate military conflicts to capture the territories and fully utilize the resources (Colgan Reference Colgan2013; Gent and Crescenzi Reference Gent and Mark2021; Monteiro and Debs Reference Monteiro and Debs2020; Powell Reference Powell2013). Second, even though fuel resources are technically divisible (Goemans and Schultz Reference Goemans and Schultz2017; Hensel and Mitchell Reference Hensel and Mitchell2005), oil and gas are often considered a symbol of invaluable national wealth and can fuel petro-nationalism (Koch and Perreault Reference Koch and Perreault2019; Park, Abolfathi, and Ward Reference Park, Abolfathi and Ward1976; Wilson Reference Wilson2015). This makes disputable territories perceptually indivisible, hindering negotiated settlement (Fearon Reference Fearon1995; Reference Fearon1996; Goddard Reference Goddard2006). Thus, I hypothesize that discoveries of giant fuel resources in disputable areas increase military conflicts, while fuel discoveries in non-disputable areas have no equivalent effects.

I test the hypothesis by combining the claimability dataset with a fine-grained dataset of over 600,000 wildcat drills. For causal identification, I leverage as-if random variation in fuel discoveries conditional on wildcat drills. I further harness the design by integrating the staggered difference-in-differences (DiD) and its recent refinements (Hassell and Holbein Reference Hassell and Holbein2025; Xu Reference Xu, Box-Steffensmeier, Christenson and Sinclair-Chapman2023). The empirical analysis indicates that while fuel discoveries in general did not significantly affect military conflicts, they increased the likelihood of military conflicts by 11.69 percentage points when the oil/gas fields were discovered in disputable areas. The effect persisted for several decades. Moreover, the analyses of causal mechanisms indicate that while fuel discoveries in disputable areas did not increase fuel production or government revenues, they increased the military capabilities of relevant states. These results suggest that the fuel discoveries increased the tangible and intangible salience of disputes, incentivized the states to expand their militaries, and thus triggered military conflicts. I further investigate the mechanisms with the “most similar” case study of two gas fields—Pinghu and Chunxiao—in the East China Sea, highlighting the crucial roles of intangible salience.

These findings advance our understanding of resource conflicts and territorial norms. While ample evidence exists for the effects of oil on intrastate conflicts (Koubi et al. Reference Koubi, Spilker, Böhmelt and Bernauer2014), the evidence for interstate conflicts remains mixed.Footnote 6 Although Colgan (Reference Colgan2010) finds that petrostates are more likely to fight a war when they have revolutionary origins, Jang and Smith (Reference Jang and Smith2021) show that Iran and Iraq drive the results. While Hendrix (Reference Hendrix2017) finds that high oil price is associated with interstate conflict, Blankenship et al. (Reference Blankenship, Hasan, Mohtadi, Overland and Urpelainen2024) find the opposite results. Other studies indicate that the effects vary across resource types (Reuveny and Barbieri Reference Reuveny and Barbieri2014), measurement (Strüver and Wegenast Reference Strüver and Wegenast2018), and locations of oil fields (Caselli, Morelli, and Rohner Reference Caselli, Morelli and Rohner2015).Footnote 7 Reviewing the literature and historical cases, Meierding (Reference Meierding, Van de Graaf, Sovacool, Ghosh, Kern and Klare2016b) even concludes that “there is little empirical support for the idea that countries fight over control of oil fields” (442). One reason for the mixed findings stems from the inattention to claimability. States do not claim every oil and gas field; when international norms permit it, they can claim oil/gas fields. Indeed, Lee (Reference Lee2024) analyzes the effects of oil on territorial claims in South America, suggesting that the effect depends on previous jurisdictions and administrative borders. This study expands her findings and suggests the crucial roles of territorial norms; the effect depends on which states can legitimately claim which fuel resources.Footnote 8

Testing the argument, however, requires a comprehensive measure of claimable areas. To this end, I compile the first globally available and geo-referenced dataset. By doing so, I address the long-lasting concern that Abramson and Carter (Reference Abramson and Carter2021) state: “[l]atent claims have been notoriously difficult for scholars to measure” (122; see also Huth Reference Huth1996). The difficulty partly stems from the fact that claimability must be measured independently of actual claims; otherwise, it is even tautological to argue that states claim territories because they are claimable.Footnote 9 Scholars have addressed this issue by focusing on historical borders (Abramson and Carter Reference Abramson and Carter2016; Reference Abramson and Carter2021; Carter Reference Carter2017; Carter and Goemans Reference Carter and Goemans2014; Huth Reference Huth1996) and foreign co-ethnic minorities (Cederman et al. Reference Cederman, Pengl, Girardin and Müller-Crepon2024; Goemans and Schultz Reference Goemans and Schultz2017; Müller-Crepon, Schvitz, and Cederman Reference Müller-Crepon, Schvitz and Cederman2025; Siroky and Hale Reference Siroky and Hale2017). However, they examine either a particular set of norms or have limited geographical and temporal scopes (e.g., Europe or Africa).Footnote 10 Finally, all of those studies ignore the sovereignty over marine areas (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2020). While Yüksel (Reference Yüksel2024) measures international legal uncertainty in maritime sovereignty, the measure varies only across years with no cross-country or geographical differences.Footnote 11 I address those limitations by integrating extant insights and providing a global geo-referenced dataset of claimable areas.

Moreover, I improve the empirical approaches to identify the causal effects of fuel resources on interstate conflicts. Although earlier studies have naively regressed conflicts on oil dependency (e.g., oil revenues per GDP) and production amounts, it is widely recognized that they are endogenous to confounders and conflicts themselves (Brooks and Kurtz Reference Brooks and Kurtz2016). Recent studies use oil deposits and discoveries as more exogenous predictors.Footnote 12 However, as acknowledged by several authors, oil deposits and discoveries depend on the frequency of wildcat drills (i.e., exploratory drilling of oil and gas fields) and thus are endogenous to investments, energy policies, political regimes, and, potentially, conflicts themselves (Bohn and Deacon Reference Bohn and Deacon2000; Brunnschweiler and Poelhekke Reference Brunnschweiler and Poelhekke2021; Cust and Harding Reference Cust and Harding2020; Meserve Reference Meserve2014). I address those limitations by conditioning on the number of wildcat drills.Footnote 13 That is, given a certain number of wildcat drills, it is as-if random whether a giant oil or gas deposit is discovered. Although this design is widely used in economics and other fields, to the best of my knowledge, it has not been applied to political science (Arezki, Ramey, and Sheng Reference Arezki, Ramey and Sheng2017; Cavalcanti, Da Mata, and Toscani Reference Cavalcanti, Da Mata and Toscani2019; Cotet and Tsui Reference Cotet and Tsui2013a; Reference Cotet and Tsui2013b; Cust et al. Reference Cust, Harding, Krings and Rivera-Ballesteros2023; Lei and Michaels Reference Lei and Michaels2014). I also address biases due to anticipatory behaviors (i.e., the anticipation of oil discoveries may affect conflicts; Basedau, Rustad, and Must Reference Basedau, Rustad and Must2018) by applying the staggered DiD, event study, and their recent refinements (Hassell and Holbein Reference Hassell and Holbein2025; Xu Reference Xu, Box-Steffensmeier, Christenson and Sinclair-Chapman2023).

THEORY: CLAIMABILITY IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

Claimability refers to the appropriateness of making a certain claim. Thus, it sets potential conditions for making a claim. Although appropriateness ultimately depends on policymakers’ subjective evaluations, it also rests on common knowledge (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998; Wendt Reference Wendt1999). Whether one state considers an act appropriate depends on whether other states consider it appropriate. Thus, while admitting the potential roles of leaders’ preferences (Colgan Reference Colgan2010) and domestic politics (Fang and Li Reference Fang and Li2020; Manekin, Grossman, and Mitts Reference Manekin, Grossman and Mitts2019; Zellman Reference Zellman2018), I focus on the international normative aspects of claimability: whether international norms designate particular claims as appropriate or not (Forsberg Reference Forsberg1996). International norms refer to “standard[s] of appropriate behavior” (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998, 891), including international laws, states’ actual practices, and customs.

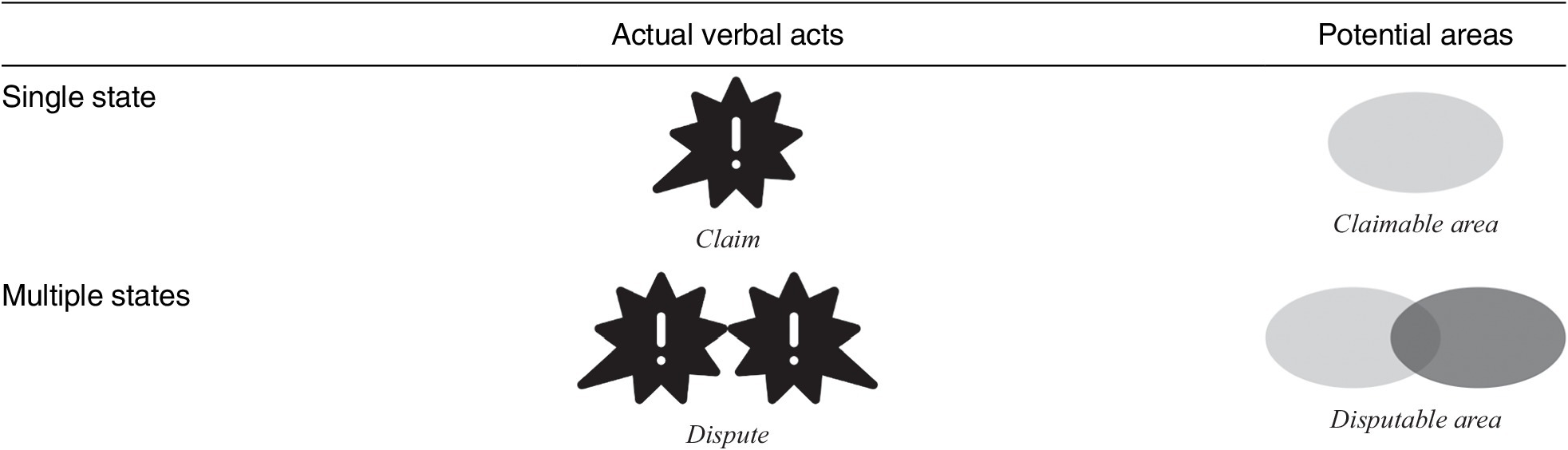

I particularly focus on claimability over territories, including terrestrial lands and waters.Footnote 14 If a state can potentially claim a territory according to international norms, the territory is claimable to the state. If a territory is claimable to more than one state, the territory is disputable to those states.Footnote 15 Importantly, as seen in Table 1, claimability and disputability refer to the potential for claims and disputes and thus conceptually differ from actual claims and disputes. Finally, while a claim and dispute refer to verbal actions and interactions, a military conflict involves military actions such as a threat, force display, clash, and war. The theoretical question that I ask is how claimability links to international military conflicts.

Table 1. Key Concepts

Hypotheses

My answer to the question is twofold; when a territory is claimable to multiple states, it incentivizes the states to claim and dispute over the territory; and fuel discoveries in disputable areas escalate it into military conflicts. The first hypothesis is relatively straightforward; claimability reduces subjective costs for making claims. Thus, ceteris paribus, states are more likely to claim and dispute over territories if the territories are claimable to them. This leads to a supplementary hypothesis that is used to check the construct validity of claimability data:

Hypothesis 0: States are more likely to dispute when they have a disputable territory.

Put simply, when a territory is disputable, states are more likely to dispute it.

Although this hypothesis is unsurprising, a more complex question lies in the escalation into military conflicts. Because military conflicts are costly, states have incentives to peacefully settle disputes (Fearon Reference Fearon1995). Moreover, disputability can only weakly predict the timing of military conflicts; while disputability changes only occasionally and states make claims for years (Frederick, Hensel, and Macaulay Reference Frederick, Hensel and Macaulay2017), they fight in specific time periods. Thus, as Abramson and Carter (Reference Abramson and Carter2021) argue, disputability must be supplemented with a direct trigger of military conflict, such as the discovery of a fuel resource.

The central argument of this paper is therefore that states engage in military conflicts when a fuel resource is discovered in disputable territories.Footnote 16 The main hypotheses are:

Hypothesis 1: States are more likely to engage in a military conflict when a fuel resource is discovered in a disputable territory, compared to when a fuel resource is not discovered in the disputable territory;

Hypothesis 2: Fuel discoveries in non-disputable areas have no equivalent effect.

As I detail below, I posit two mechanisms that support the hypotheses: fuel discoveries increase tangible and/or intangible salience of disputable territories (Hensel et al. Reference Hensel, Mitchell, Sowers and Thyne2008; Hensel and Mitchell Reference Hensel and Mitchell2005).Footnote 17 Although I do not argue that those are the only causes of military conflicts, and the main contribution of this study lies in the concept of claimability, it is imperative to understand why fuel discoveries in disputable areas lead to military conflicts.

Mechanism 1: Tangible Salience

The first possibility is that fuel discoveries in disputable areas increase the tangible, and more specifically, economic salience of the territories. Although states may peacefully divide the territory or resource revenues (Fearon Reference Fearon1995; Reference Fearon1996), the peaceful settlement can result in economic inefficiency (logic of costly peace; Coe Reference Coe2011; Colgan Reference Colgan2013; Fearon Reference Fearon2018; Jackson and Morelli Reference Jackson and Morelli2009; Powell Reference Powell1993). Because no central authority can enforce the settlement, states must retain a certain level of military capability to maintain the settlement. The armament level and thus associated costs are particularly large when states have high stakes in disputable territories.Footnote 18 Then, while states may tolerate the relatively low costs for armament, fuel discoveries increase the required level of armament to the extent that the costs are even larger than the costs of military conflict. This incentivizes the states to fight.

Moreover, unless peaceful settlement eliminates the risks of re-escalation, states cannot safely utilize the fuel resources in disputable areas (logic of hold-up problems; Gent and Crescenzi Reference Gent and Mark2021; Monteiro and Debs Reference Monteiro and Debs2020; Powell Reference Powell2013). The extraction of fuel resources requires a large amount of initial investment, but the facilities are vulnerable to military attacks (Meserve Reference Meserve2014). Thus, unless states are confident that they can maintain the negotiated peace for a long time, they cannot easily make investments. Even worse, stronger states may intentionally delay and hamper the development of fuel fields so that their opponents will not benefit from the resources and thus remain weak (Monteiro and Debs Reference Monteiro and Debs2020). Those opportunity costs incentivize the states to initiate military conflict, completely control the territory, and fully utilize the resources.

Thus, fuel discoveries in disputable areas can create economic inefficiency, which in turn leads to military conflicts. This logic is consistent with the more generic view that fuel discoveries increase the tangible/economic salience of the territory and thus cause military conflicts (Hensel et al. Reference Hensel, Mitchell, Sowers and Thyne2008; Hensel and Mitchell Reference Hensel and Mitchell2005). The economic explanation, however, requires that the economic inefficiency is larger than the costs of military conflicts. Because this requirement may not always hold, it is important to consider another complementary mechanism: intangible salience.

Mechanism 2: Intangible Salience

Fuel discoveries can also increase the intangible salience of disputable territories. Although fuel resources are technically divisible and thus usually classified as tangible goods (Goemans and Schultz Reference Goemans and Schultz2017; Hensel and Mitchell Reference Hensel and Mitchell2005), they are also considered a symbol of national wealth and can incite petro-nationalism (Koch and Perreault Reference Koch and Perreault2019; Park, Abolfathi, and Ward Reference Park, Abolfathi and Ward1976; Wilson Reference Wilson2015). Although people may be concerned about the environmental side effects of fuel production, the majority of people are distant from oil/gas fields and tend to hold nationalistic views about fuel resources (Kim and Mkutu Reference Kim and Mkutu2021; Tanaka Reference Tanaka2016).

The public attitudes, in turn, pressure the government to take hawkish policies. Because even a minor concession can be considered a loss of invaluable national wealth, the issue becomes perceptually indivisible; the satisfactory solution is limited to complete control over the territory and resources. This eliminates bargaining range and hence triggers military conflicts (logic of issue indivisibility; Fearon Reference Fearon1995; Reference Fearon1996; Goddard Reference Goddard2006; Hassner Reference Hassner2003). Furthermore, military conflicts allow national leaders to signal their resolve and interests in newly discovered resources to domestic audiences (Fearon Reference Fearon1994; Goemans and Fey Reference Goemans and Fey2009; Schultz Reference Schultz2005) or other states (logic of signaling; Acharya and Lee Reference Acharya and Lee2018; Reference Acharya and Lee2022). The indivisibility and signaling hamper a peaceful settlement, resulting in military conflicts.

These lines of argument imply that fuel discoveries increase the intangible salience of disputable territories and thus trigger military conflicts. Moreover, unlike tangible salience, the effects may not be limited to military conflicts over disputable territories; the effects can spill over to non-territorial conflicts. Nationalists, for instance, may consider that non-territorial actions (e.g., policy or regime change) are necessary for defending their invaluable territories and resources. Finally, none of the mechanisms can be applied to fuel discoveries in non-disputable areas; a single claimant can safely and fully utilize the resources, and petro-nationalism, if any, can only increase national pride without antagonizing attitudes toward foreign states.Footnote 19

MEASUREMENT: CLAIMABLE AND DISPUTABLE AREAS FROM 1946 TO 2024

Testing the hypotheses, however, raises challenges; I need to measure which states can potentially claim which areas. I address this challenge by focusing on three sets of international norms that emerged after the world wars: territorial integrity (Abramson and Carter Reference Abramson and Carter2016; Reference Abramson and Carter2021; Carter Reference Carter2017; Carter and Goemans Reference Carter and Goemans2011; Reference Carter and Goemans2014), self-determination and minority protection (Cederman et al. Reference Cederman, Pengl, Girardin and Müller-Crepon2024; Goemans and Schultz Reference Goemans and Schultz2017; Müller-Crepon, Schvitz, and Cederman Reference Müller-Crepon, Schvitz and Cederman2025; Siroky and Hale Reference Siroky and Hale2017), and maritime sovereignty (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2020; Yüksel Reference Yüksel2024). Although other norms might be relevant as well, these are arguably the strongest territorial norms since the world wars (see the above citations).Footnote 20 Figure 1 is an overview of the conceptualization and measurement. As I detail below, the international norms are ambiguous and inconsistent, creating multiple claimants for a given territory (the inconsistencies are denoted by double-headed arrows in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptualization and Measurement

Note: The figure maps international norms (left) onto corresponding claimable (center) and disputable (right) areas. A disputable area is an intersection of claimable areas between different countries. The possible intersections are denoted by double-headed arrows, representing inconsistency between or within international norms.

Territorial Integrity

The first and foremost is the norm of territorial integrity, which refers to the states’ rights to defend their borders and their obligations to respect the borders of other states. Obviously, states can validly claim their control over their current territorial lands. The territorial integrity norm emerged after WWI and was established after WWII (Zacher Reference Zacher2001). However, the norm has also been subject to ambiguity. While the norm barred the restoration of historical territories lost before WWII, it remained unclear whether states could claim their territories that were lost after WWII (Murphy Reference Murphy1990). This implies that the integrity of post-WWII territories can potentially belie the integrity of current territories.

Thus, for the period of analysis (1946–2024), I include all current and past territorial lands as claimable areas. The disputable areas are those in which the current territorial lands overlap the past territorial lands of other states. Because the end of WWII marked a new territorial status quo, proscribing the restoration of prewar territories (Altman Reference Altman2020; McDonald Reference McDonald2009; Zacher Reference Zacher2001), I define past territories as lost territories after WWII.Footnote 21 I exclude former colonial lands (e.g., the UK’s claim over British India after its independence), as the norm of anti-colonization barred the restoration of colonial empires.Footnote 22

Self-Determination and Minority Protection

The territorial integrity norm, however, has been challenged by the norm of self-determination: the rights of ethnic or national groups to form their own states (Cederman et al. Reference Cederman, Pengl, Girardin and Müller-Crepon2024; Forsberg Reference Forsberg1996; Goemans and Schultz Reference Goemans and Schultz2017; Müller-Crepon, Schvitz, and Cederman Reference Müller-Crepon, Schvitz and Cederman2025; Siroky and Hale Reference Siroky and Hale2017; Zacher Reference Zacher2001). Although the idea of self-determination is traced back to the French Revolution in 1789, it emerged as an international norm after WWI when Woodrow Wilson announced the 14 Points in 1918. After WWII, the UN Charter referred to self-determination as one of the purposes of the United Nations.

Minority protection—the states’ rights and obligations to protect foreign discriminated groups—emerged as a corollary of self-determination (Pronto Reference Pronto2016; Sellers Reference Sellers2001; Thürer and Burri Reference Thürer and Burri2009).Footnote 23 Legally, the norm is based on argumentum a contrario (i.e., appeal from the contrary) of the 1971 Friendly Relations Declaration, which stipulates that “[n]othing in the foregoing paragraphs shall be construed as authorizing or encouraging any actions which would dismember or impair, totally or in part, the territorial integrity or political unity of sovereign and independent States conducting themselves in compliance with the principle of equal rights and self-determination of people” (UN General Assembly 1971, 124; emphasis added). This passage left the possibility that territorial integrity is compromised when states do not guarantee equal rights. Although no international law justifies forced annexation, states can at least legitimately claim the protection of unrepresented groups. Given the power of nationalism since the twentieth century, I focus on states’ claims over unrepresented co-ethnicities.

Thus, I include lands of unrepresented co-ethnicities in foreign countries as claimable areas for 1946–2024.Footnote 24 The information about the geographical distribution of ethnic groups is derived from the GREG dataset (Weidmann, Rød, and Cederman Reference Weidmann, Rød and Cederman2010). Because the population sizes are not available in the GREG, I use the geographical extents to identify co-ethnic groups of each country. For each country, I identify co-ethnic groups as (i) an ethnic group of the largest geographical extent within the country compared to other groups, or (ii) ethnic groups whose geographical extents are the largest in the country compared to their extents in other countries.Footnote 25 Because minority protection can be justified only for unrepresented groups, I focus on the groups that are powerless, discriminated, self-excluded, or under state collapse in the Geo-EPR dataset (Wucherpfennig et al. Reference Wucherpfennig, Weidmann, Girardin, Cederman and Wimmer2011).Footnote 26 Finally, I limit the claimable areas to those contiguous to the main lands of a country to exclude the claims over distant lands (e.g., lands of overseas Chinese).

Maritime Sovereignty

Finally, although the term “territory” is often used interchangeably with lands, territory also includes water areas (e.g., “territorial sea”; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2020). Even compared to the norms about territorial lands, the maritime norms are ambiguous and inconsistent (Yüksel Reference Yüksel2024). Indeed, territorial water is a relatively new concept (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2020). In the nineteenth century or earlier, different states set different extents of territorial seas, ranging from 4 to 12 nautical miles from the coast, often reflecting the reach of cannons. The interwar period saw several attempts to codify territorial seas (e.g., the 1930 League of Nations Codification Conference), but states failed to agree on the exact extent of territorial seas.

The situation was further complicated in 1945 when President Harry S. Truman unilaterally declared “the exercise of jurisdiction over the natural resources of the subsoil and sea bed of the continental shelf by the contiguous nation” (Reference Truman1945). The Truman Proclamation was a direct challenge to existing practices; while customary laws set territorial seas as areas within a fixed distance from the coast, continental shelves depend on geographical characteristics and can potentially extend to vast areas. While many countries quickly adopted the Truman Proclamation, three Latin American countries—Chile, Ecuador, and Peru—responded differently; they proposed 200 nautical miles of territorial seas (they had long coastlines but no continental shelves). While the 1958 Geneva Convention defined the legal properties of territorial seas, states still failed to agree on the exact extent.

The situation changed in 1982 when 183 states signed the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Territorial seas were defined as 12 nautical miles from the coast. The UNCLOS also defined exclusive economic zones (EEZ) as 200 nautical miles from the coast, granting coastal countries exclusive rights to extract resources. However, even the UNCLOS did not unequivocally define maritime sovereignty (Yüksel Reference Yüksel2024). The UNCLOS did not clearly define how to delimit the border when a country’s continental shelf or EEZ overlaps those of other countries. Although the International Court of Justice (ICJ) referred to the principle of equity, citing various factors such as the length of coastlines, marine geology, and culture and history, there is no universally accepted way to delimit maritime borders.Footnote 27

Given those historical developments, I operationalize claimable seas in the following manner, which accounts for both international laws and states’ de facto practices.

-

(a) Territorial sea: From 1946 to 2024, the claimable areas include the territorial seas of 12 nautical miles from the coast. Even without the UNCLOS, 12 nautical miles have long been the maximum extent of territorial seas.

-

(b) Continental shelf: For the period after the Truman Proclamation (1946–2024), I include continental shelves as claimable areas. I operationalize a continental shelf as a marine area of less than 500-meter depth that is contiguous to the closest coastal country.Footnote 28

-

(c) Exclusive economic zone (EEZ): For the period after the UNCLOS (1983–2024), the EEZs are included as claimable areas. The EEZs are measured as marine areas within 200 nautical miles of the closest coastal country.Footnote 29

Importantly, territorial seas and continental shelves can potentially overlap other countries’ EEZs. The overlapping areas constitute disputable areas, and I call them disputable seas. Footnote 30

Figure 2 presents the extent of claimable and disputable areas in 2012. The claimable areas on land and sea are denoted as light and dark ivory colors, respectively. The disputable areas include the intersections of current and past territorial lands (gray zones), current territorial lands and foreign ethnic minorities (red zones), and territorial seas or EEZs and continental shelves (blue zones). Although disputable seas are rare, there is a modest size of lost lands, especially in the former Soviet region (Altman Reference Altman2020; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2020). Foreign ethnic minorities are more common in Africa, reflecting their artificial national borders (Goemans and Schultz Reference Goemans and Schultz2017; Michalopoulos and Papaioannou Reference Michalopoulos and Papaioannou2016). In the main analysis, I combine lost and co-ethnic lands and disputable seas, and later disaggregate them.

Figure 2. Claimable and Disputable Areas in 2012

Note: The figure shows claimable areas on lands (light ivory) and seas (dark ivory). The land areas of lost territories and unrepresented foreign co-ethnic groups are denoted as Lost Lands and Co-ethnic Lands, respectively (gray and red zones). When a continental shelf overlaps other countries’ territorial seas or EEZs, the area is denoted as a disputable sea (blue zone).

DESIGN: NATURAL EXPERIMENT WITH FUEL DISCOVERIES

To demonstrate the usefulness of the new dataset, I analyze the effects of fuel discoveries on interstate conflict and how the effect differs between fuel discoveries in disputable and non-disputable areas. Fuel discoveries are especially illustrative as they have explicit geographical locations, allowing me to identify disputable and non-disputable discoveries. However, causal identification poses a challenge; fuel discoveries depend on wildcat drills, which are endogenous to investment, energy policies, and conflicts themselves (Bohn and Deacon Reference Bohn and Deacon2000; Brunnschweiler and Poelhekke Reference Brunnschweiler and Poelhekke2021; Cust and Harding Reference Cust and Harding2020; Meserve Reference Meserve2014). I address this problem by conditioning on the number of wildcat drills.

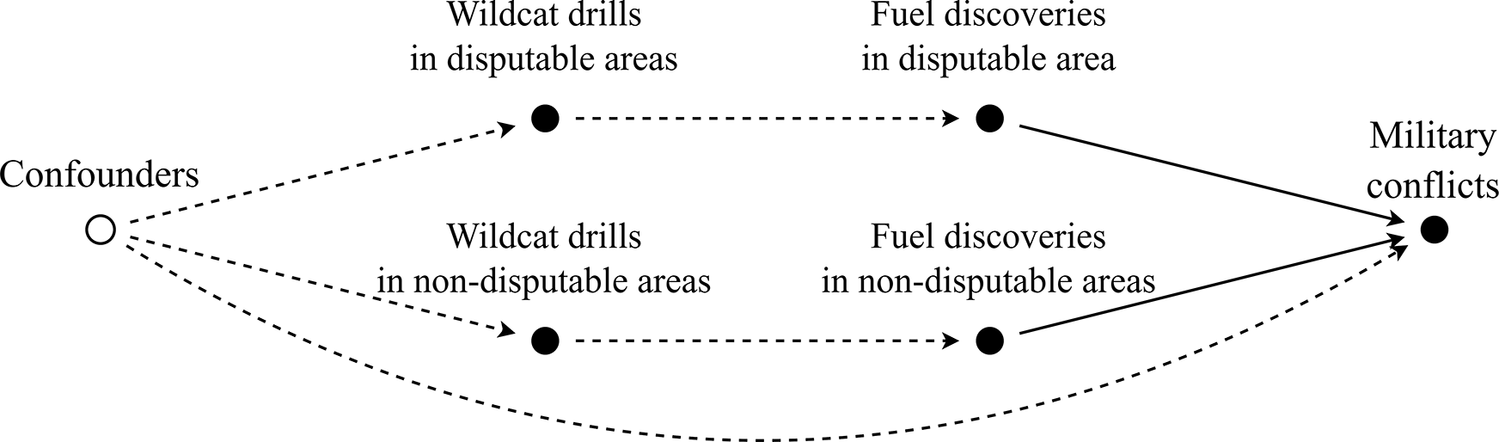

Figure 3 illustrates the research design with a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG).Footnote 31 The quantities of interest are the effects of fuel discoveries in disputable and non-disputable areas on military conflicts (solid lines). The research design does not assume that fuel discoveries are unconditionally exogenous or that the number of wildcat drills is exogenous. It instead assumes that the number of fuel discoveries is exogenous conditional on the number of wildcat drills (dashed lines). Although geological surveys, investments, politics, disputability, and conflicts can affect whether a country conducts or permits wildcat drills, given a certain number of wildcat drills, their results—whether wildcat drills discover giant fuel reserves—are plausibly exogenous. This implies that by “blocking” wildcat drills in Figure 3, fuel discoveries become independent of confounders. This design is valid unless confounders affect fuel discoveries other than their effects through the number of wildcat drills (i.e., no arrows from confounders to fuel discoveries in Figure 3). Because confounders affect fuel discoveries only through their effects on the quantity or quality of wildcat drills, this assumption holds unless confounders affect the quality of wildcat drills (e.g., drilling technologies). In a later validity check, I consider possible violations of the assumption.

Figure 3. Directed Acyclic Graph

Note: The black and white dots are the observed and unobserved variables, respectively. The solid and dashed arrows represent the quantities of interest and causal effects assumed to exist, respectively. For causal identification, confounders should not affect fuel discoveries other than their effects through the number of wildcat drills (i.e., no arrows from confounders to fuel discoveries).

Furthermore, I supplement the natural experiment with the DiD to account for static confounders. Although oil and gas are more likely to be found in areas of certain geological characteristics (Cassidy Reference Cassidy2019; Hunziker and Cederman Reference Hunziker and Cederman2017), those static features cannot explain changes over time. Thus, I compare the changes in the likelihood of military conflicts after giant fuel discoveries. Moreover, the event study describes the changes in the likelihood of military conflicts before and after the treatment, allowing me to check anticipatory behaviors and the common trend assumption. In my setup, the years of fuel discoveries vary across units, and thus the design is a staggered DiD (Goodman-Bacon Reference Goodman-Bacon2021).

Sample and Unit

The unit of analysis is a dyad–year (i.e., a pair of countries

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

in year

$ j $

in year

![]() $ t $

).Footnote

32 The sample includes all contiguous dyads between 1946 and 2012.Footnote

33 There are 30,877 observations comprised of 777 dyads, 197 countries, and 67 years. The summary statistics are available in Table A3-1 in the Supplementary Material.

$ t $

).Footnote

32 The sample includes all contiguous dyads between 1946 and 2012.Footnote

33 There are 30,877 observations comprised of 777 dyads, 197 countries, and 67 years. The summary statistics are available in Table A3-1 in the Supplementary Material.

Outcome Variables

The main outcome variable for testing Hypotheses 1 and 2 is the incidence of military conflicts. The data are derived from the Militarized Interstate Disputes (MID) dataset by the Correlates of War (CoW) project—a standard dataset of interstate conflicts (Sarkees and Schafer Reference Sarkees and Schafer2000). The outcome variable

![]() $ {Y}_{MID, ijt} $

takes 1 if country

$ {Y}_{MID, ijt} $

takes 1 if country

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

entered MIDs in year

$ j $

entered MIDs in year

![]() $ t $

.Footnote

34 About 4.6% of observations experienced MIDs. The MIDs include any disputes involving military actions, such as threats, displays, clashes, and wars. Because fuel discoveries can affect both territorial and non-territorial MIDs (see the discussion about intangible salience), the main outcome variable contains all MIDs. I later analyze each type of MID and check the robustness to different measurements (Braithwaite and Lemke Reference Braithwaite and Lemke2011).

$ t $

.Footnote

34 About 4.6% of observations experienced MIDs. The MIDs include any disputes involving military actions, such as threats, displays, clashes, and wars. Because fuel discoveries can affect both territorial and non-territorial MIDs (see the discussion about intangible salience), the main outcome variable contains all MIDs. I later analyze each type of MID and check the robustness to different measurements (Braithwaite and Lemke Reference Braithwaite and Lemke2011).

The supplementary outcome variable for testing Hypothesis 0 is the presence of disputes. The data are derived from the ICoW dataset (Frederick, Hensel, and Macaulay Reference Frederick, Hensel and Macaulay2017; Hensel et al. Reference Hensel, Mitchell, Owsiak and Wiegand2025; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2020). The ICoW dataset is available only up to 2001, resulting in a smaller sample size (

![]() $ n=\mathrm{15,757} $

). The outcome variable

$ n=\mathrm{15,757} $

). The outcome variable

![]() $ {Y}_{ICoW, ijt} $

takes 1 if there is any dispute over lands, seas, or identity groups between country

$ {Y}_{ICoW, ijt} $

takes 1 if there is any dispute over lands, seas, or identity groups between country

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

in year

$ j $

in year

![]() $ t $

.Footnote

35 Note that, unlike the main outcome variable,

$ t $

.Footnote

35 Note that, unlike the main outcome variable,

![]() $ {Y}_{ICoW, ijt} $

includes both militarized and non-militarized disputes. About 26.37% of the available observations have disputes.

$ {Y}_{ICoW, ijt} $

includes both militarized and non-militarized disputes. About 26.37% of the available observations have disputes.

Treatment and Control Variables

The treatment variable is the discovery of giant oil and/or gas fields in disputable areas. The information about the locations and years of fuel discoveries is derived from two sources: Cust, Mihalyi, and Rivera-Ballesteros (Reference Cust, Mihalyi and Rivera-Ballesteros2022) and Enverus (2024). Cust, Mihalyi, and Rivera-Ballesteros (Reference Cust, Mihalyi and Rivera-Ballesteros2022) extend the dataset of Horn (Reference Horn and Halbouty2003) to 2018. The dataset contains information about the locations and years of giant fuel discoveries (>500 million barrels of oil equivalent). Because this dataset contains only wildcat drills related to giant fields, I supplement it with the industry-standard dataset compiled by Enverus (2024), which contains the records of over 600,000 wildcat drills for the period of analysis.Footnote 36

With those data sources, I calculate the number of giant fuel discoveries and wildcat drills in disputable areas. The main treatment variable

![]() $ discover{y}_{disputable, ijt} $

takes 1 after a giant fuel was discovered in areas that are disputable between countries

$ discover{y}_{disputable, ijt} $

takes 1 after a giant fuel was discovered in areas that are disputable between countries

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

.Footnote

37 This variable takes 1 for all years after a giant fuel discovery until the location of the oil/gas field ceases to be claimable for country

$ j $

.Footnote

37 This variable takes 1 for all years after a giant fuel discovery until the location of the oil/gas field ceases to be claimable for country

![]() $ i $

or

$ i $

or

![]() $ j $

. The control variable

$ j $

. The control variable

![]() $ dril{l}_{disputable, ijt} $

is the cumulative number of wildcat drills in areas disputable for countries

$ dril{l}_{disputable, ijt} $

is the cumulative number of wildcat drills in areas disputable for countries

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

up to year

$ j $

up to year

![]() $ t $

. I use the cumulative number of wildcat drills because the probability of

$ t $

. I use the cumulative number of wildcat drills because the probability of

![]() $ discover{y}_{disputable, ijt} $

depends on the number of all wildcat drills up to year

$ discover{y}_{disputable, ijt} $

depends on the number of all wildcat drills up to year

![]() $ t $

.Footnote

38 I also create corresponding variables for giant fuel discoveries and wildcat drills in all claimable areas for country

$ t $

.Footnote

38 I also create corresponding variables for giant fuel discoveries and wildcat drills in all claimable areas for country

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

(

$ j $

(

![]() $ discover{y}_{all, ijt} $

,

$ discover{y}_{all, ijt} $

,

![]() $ dril{l}_{all, ijt} $

) and areas claimable to either country

$ dril{l}_{all, ijt} $

) and areas claimable to either country

![]() $ i $

or

$ i $

or

![]() $ j $

but not both (

$ j $

but not both (

![]() $ discover{y}_{\neg disputable, ijt} $

,

$ discover{y}_{\neg disputable, ijt} $

,

![]() $ dril{l}_{\neg disputable, ijt} $

).Footnote

39

$ dril{l}_{\neg disputable, ijt} $

).Footnote

39

Finally, I create an indicator variable

![]() $ dis{putable}_{ijt} $

that takes 1 if countries

$ dis{putable}_{ijt} $

that takes 1 if countries

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

possess any disputable areas in year

$ j $

possess any disputable areas in year

![]() $ t $

. Except for those variables, I do not include other covariates (e.g., democracies and GDP per capita) and leave the analysis with additional control variables for a later robustness check. As far as

$ t $

. Except for those variables, I do not include other covariates (e.g., democracies and GDP per capita) and leave the analysis with additional control variables for a later robustness check. As far as

![]() $ discover{y}_{disputable, ijt} $

is randomly assigned conditional on

$ discover{y}_{disputable, ijt} $

is randomly assigned conditional on

![]() $ dril{l}_{disputable, ijt} $

, there is no need to include additional control variables. Indeed, because those variables can be affected by fuel discoveries, controlling for them can induce post-treatment control biases (Angrist and Pischke Reference Angrist and Pischke2009).

$ dril{l}_{disputable, ijt} $

, there is no need to include additional control variables. Indeed, because those variables can be affected by fuel discoveries, controlling for them can induce post-treatment control biases (Angrist and Pischke Reference Angrist and Pischke2009).

Specification

With those variables, I use the two-way fixed-effects (TWFE) model. While acknowledging the problems of TWFE models (Goodman-Bacon Reference Goodman-Bacon2021; Xu Reference Xu, Box-Steffensmeier, Christenson and Sinclair-Chapman2023), I prefer not to rely on particular methods and, instead, show the results with the standard model. I later extensively analyze the recent DiD methods and show their robustness.Footnote 40 The baseline specification is:Footnote 41

$$ 100\times {Y}_{MID, ijt}={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{\alpha}_{ij}+{\mu}_t+\delta\;dis cover{y}_{all, ijt}\\ {}+\hskip2px \beta\;dril{l}_{all, ijt}+\gamma\;dis{putable}_{ij t}+{\varepsilon}_{ij t}.\end{array}} $$

$$ 100\times {Y}_{MID, ijt}={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{\alpha}_{ij}+{\mu}_t+\delta\;dis cover{y}_{all, ijt}\\ {}+\hskip2px \beta\;dril{l}_{all, ijt}+\gamma\;dis{putable}_{ij t}+{\varepsilon}_{ij t}.\end{array}} $$

The parameter of interest is

![]() $ \delta $

, which represents the effect of giant fuel discoveries on MIDs in a percentage point scale.Footnote

42 The model contains the dyad- and year-fixed effects

$ \delta $

, which represents the effect of giant fuel discoveries on MIDs in a percentage point scale.Footnote

42 The model contains the dyad- and year-fixed effects

![]() $ {\alpha}_{ij} $

and

$ {\alpha}_{ij} $

and

![]() $ {u}_t $

as well as the control variables

$ {u}_t $

as well as the control variables

![]() $ dril{l}_{all., ijt} $

and

$ dril{l}_{all., ijt} $

and

![]() $ dis{putable}_{ijt} $

. The control variable

$ dis{putable}_{ijt} $

. The control variable

![]() $ dril{l}_{all., ijt} $

is the cumulative number of wildcat drills, accounting for the non-random variation in fuel discoveries. With the fixed effects,

$ dril{l}_{all., ijt} $

is the cumulative number of wildcat drills, accounting for the non-random variation in fuel discoveries. With the fixed effects,

![]() $ dis{putable}_{ijt} $

accounts for changes in disputable areas (e.g., UNCLOS in 1982).

$ dis{putable}_{ijt} $

accounts for changes in disputable areas (e.g., UNCLOS in 1982).

The baseline specification, however, dismisses an important heterogeneity between oil discoveries in disputable and non-disputable areas. I thus disaggregate Equation 1 into the following model:Footnote 43

$$ 100\times {Y}_{MID, ijt}={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{a}_{ij}+{u}_t+{\delta}_1 discover{y}_{\mathit{disputable,}\ ijt}\\ {}+\hskip2px {\beta}_1 dril{l}_{\mathit{disputable,}\ ijt}\\ {}+\hskip2px {\delta}_0 discover{y}_{\neg \mathit{disputable,}\ ijt}\\ {}+\hskip2px {\beta}_0 dril{l}_{\neg \mathit{disputable,}\ ijt}+\vartheta\;dis{putable}_{ij t}+{\epsilon}_{ij t}.\end{array}} $$

$$ 100\times {Y}_{MID, ijt}={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{a}_{ij}+{u}_t+{\delta}_1 discover{y}_{\mathit{disputable,}\ ijt}\\ {}+\hskip2px {\beta}_1 dril{l}_{\mathit{disputable,}\ ijt}\\ {}+\hskip2px {\delta}_0 discover{y}_{\neg \mathit{disputable,}\ ijt}\\ {}+\hskip2px {\beta}_0 dril{l}_{\neg \mathit{disputable,}\ ijt}+\vartheta\;dis{putable}_{ij t}+{\epsilon}_{ij t}.\end{array}} $$

In this main model, the treatment variable

![]() $ discover{y}_{all, ijt} $

and control variable

$ discover{y}_{all, ijt} $

and control variable

![]() $ dril{l}_{all, ijt} $

are disaggregated to those in disputable and non-disputable areas. The parameters of interest are

$ dril{l}_{all, ijt} $

are disaggregated to those in disputable and non-disputable areas. The parameters of interest are

![]() $ {\delta}_1 $

and

$ {\delta}_1 $

and

![]() $ {\delta}_0 $

, which represent the effects of giant fuel discoveries in disputable and non-disputable areas, respectively. For example,

$ {\delta}_0 $

, which represent the effects of giant fuel discoveries in disputable and non-disputable areas, respectively. For example,

![]() $ {\delta}_1 $

represents the changes in the MIDs after giant fuel discoveries in disputable areas, relative to the corresponding changes after no giant fuel discoveries in disputable areas.

$ {\delta}_1 $

represents the changes in the MIDs after giant fuel discoveries in disputable areas, relative to the corresponding changes after no giant fuel discoveries in disputable areas.

Finally, I test the supplementary Hypothesis 0 by using the following regression:

The model describes whether disputability is associated with actual disputes. That is, it tests whether countries

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

are more likely to have a dispute when an area is claimable for both countries. Unlike Equations 1 and 2, Equation 3 does not identify causality; it instead checks the construct validity of

$ j $

are more likely to have a dispute when an area is claimable for both countries. Unlike Equations 1 and 2, Equation 3 does not identify causality; it instead checks the construct validity of

![]() $ dis{putable}_{ijt} $

.

$ dis{putable}_{ijt} $

.

Following Liu, Wang, and Xu (Reference Liu, Wang and Xu2024) and others, I exclude “always-treated” dyads, where

![]() $ discover{y}_{disputable, ijt} $

is

$ discover{y}_{disputable, ijt} $

is

![]() $ 1 $

for the entire period of the sample (e.g., giant fuel discoveries in disputable areas prior to 1946). I also exclude years after treatment reversal, where oil/gas fields ceased to be disputable for countries

$ 1 $

for the entire period of the sample (e.g., giant fuel discoveries in disputable areas prior to 1946). I also exclude years after treatment reversal, where oil/gas fields ceased to be disputable for countries

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

(e.g., the UK after the independence of its colonies). In the staggered DiD, those observations are inappropriate control units. The treated dyads, for instance, should be compared to the never-treated dyads (i.e., the dyads without any giant fuel discoveries in disputable areas) or the not-yet-treated units (i.e., the dyads before giant fuel discoveries in disputable areas), instead of the always-treated or once-treated units (Goodman-Bacon Reference Goodman-Bacon2021). Across all specifications, the standard errors are two-way clustered by country

$ j $

(e.g., the UK after the independence of its colonies). In the staggered DiD, those observations are inappropriate control units. The treated dyads, for instance, should be compared to the never-treated dyads (i.e., the dyads without any giant fuel discoveries in disputable areas) or the not-yet-treated units (i.e., the dyads before giant fuel discoveries in disputable areas), instead of the always-treated or once-treated units (Goodman-Bacon Reference Goodman-Bacon2021). Across all specifications, the standard errors are two-way clustered by country

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

.Footnote

44 For replication, see Kikuta (Reference Kikuta2026).

$ j $

.Footnote

44 For replication, see Kikuta (Reference Kikuta2026).

RESULTS: FUEL DISCOVERIES DO CAUSE INTERSTATE CONFLICTS

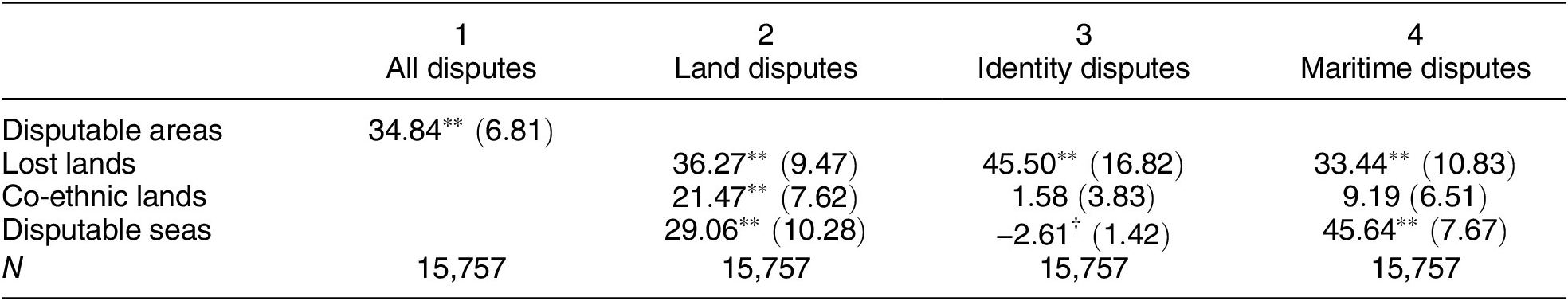

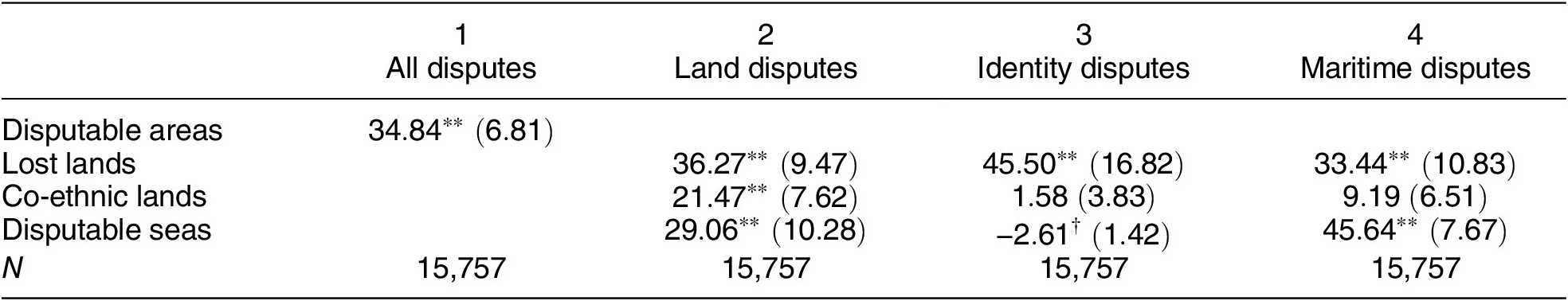

I first test the supplementary Hypothesis 0 by examining whether disputability is associated with actual disputes in the ICoW dataset. Table 2 presents correlations between the presence of disputable areas and that of actual disputes. As shown in column 1, the presence of disputable areas is associated with a higher likelihood of disputes by 34.8% points—a high and sizable correlation.

Table 2. Correlation between Disputable Areas and Actual Disputes

Note: The outcome variables are the presence of land, maritime, and identity disputes in the ICoW dataset. The coefficient values and standard errors are shown in a percentage point scale. The models include no fixed effects. The standard errors are two-way clustered by country

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

.

$ j $

.

![]() $ \ast \ast p<0.01;\ast p<0.05;\dagger p<0.1 $

.

$ \ast \ast p<0.01;\ast p<0.05;\dagger p<0.1 $

.

From columns 2 to 4 of Table 2, I disaggregate disputes into those about lands, identity, and seas, and also disputable areas into those related to lost lands, co-ethnicities, and marine areas. First, lost lands positively correlate with any type of dispute without fixed effects. Dyads with lost lands are usually in hostile relationships due to past disputes (e.g., Russia and Georgia), which should increase all types of disputes. Second, foreign co-ethnic lands positively correlate with land disputes (third row of Table 2). The null effect on identity disputes reflects the fact that identity disputes are extremely rare. Only 0.7% had identity disputes, which is about one-sixth of the land or maritime disputes. Third, disputable seas are associated with land and maritime disputes (fourth row of Table 2). This is consistent with the fact that maritime disputes often involve disputes over remote islands (e.g., the Senkaku/Diaoyudao islands between Japan and China). Moreover, disputable seas are also weakly associated with fewer identity disputes, which reflects the fact that disputable seas concentrate on developed countries, where identity disputes are rare. These results are consistent with Hypothesis 0, indicating the validity of the claimability dataset.Footnote 45

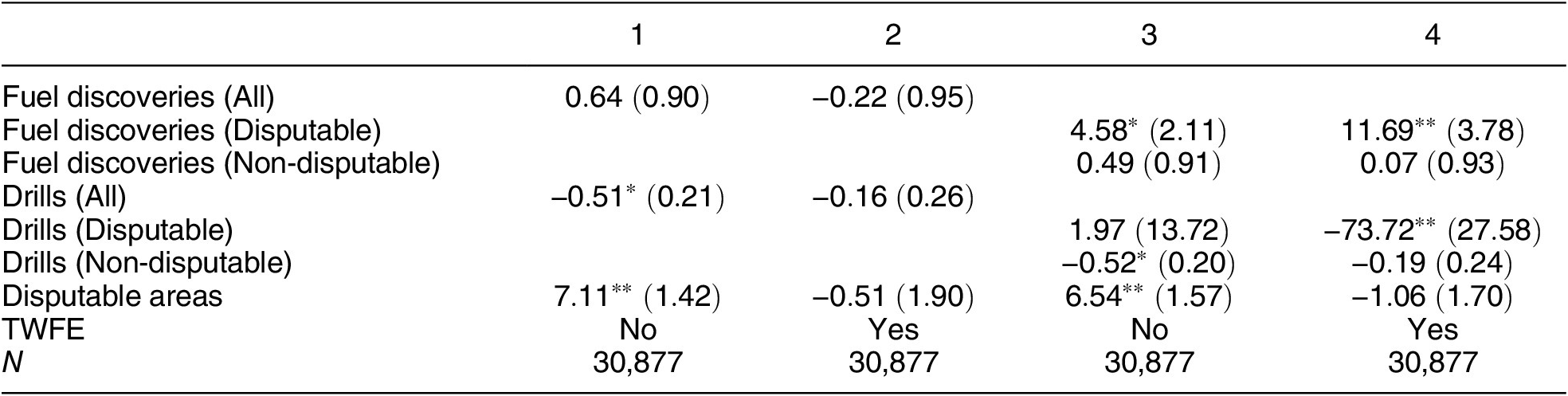

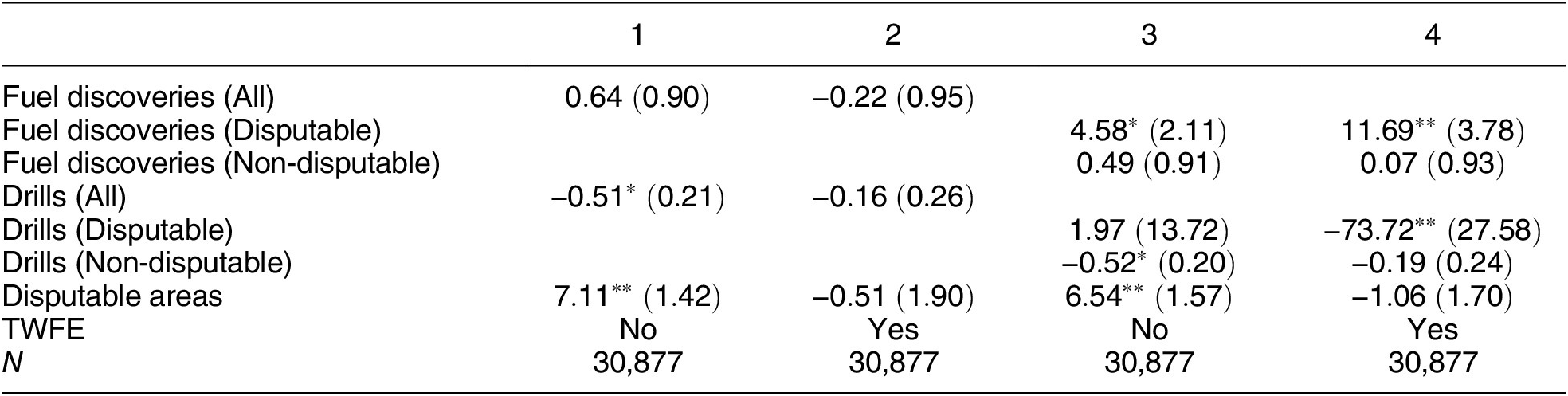

Given the measurement validity, I now turn to Hypotheses 1 and 2. Table 3 presents the results of the main analysis with and without the two-way fixed effects. Only the models with the fixed effects identify the causal effect (columns 2 and 4 of Table 3). Although disputable areas positively correlate with MIDs (column 1), the correlation disappears with the fixed effects (column 2). This is consistent with my argument that disputable areas change only occasionally and thus cannot predict the timing of MIDs. Moreover, I do not find any effect of giant fuel discoveries on MIDs (column 2). Indeed, even with the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval, the effect size is

![]() $ -2.1 $

% points. As I have stated, neither disputable areas nor fuel discoveries alone can adequately predict MIDs.

$ -2.1 $

% points. As I have stated, neither disputable areas nor fuel discoveries alone can adequately predict MIDs.

Table 3. Effects of Giant Fuel Discoveries on MIDs

Note: The outcome variable is the Militarized Interstate Disputes (MIDs). The coefficient values and standard errors are in a percentage point scale. Columns 1 and 3 do not include fixed effects, and columns 2 and 4 include dyad- and year-fixed effects. Only the models with the fixed effects identify the causal effect. The standard errors are two-way clustered by country

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

.

$ j $

.

![]() $ \ast \ast p<0.01;\ast p<0.05;\dagger p<0.1 $

.

$ \ast \ast p<0.01;\ast p<0.05;\dagger p<0.1 $

.

However, when I disaggregate the fuel discoveries to those in disputable and non-disputable areas (columns 3 and 4 of Table 3), an important pattern emerges. As shown in column 4 of Table 3, giant fuel discoveries in disputable areas increased the likelihood of MIDs by 11.69% points compared to the absence of giant discoveries in the disputable areas. This is equivalent to an over 154% increase from the sample average (4.6%). By contrast, discoveries in non-disputable areas lack significant effect, and the point estimate is close to zero. Indeed, the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval is 1.9 percentage points, which is substantively negligible. These findings are consistent with Hypotheses 1 and 2, highlighting the critical role of disputability.

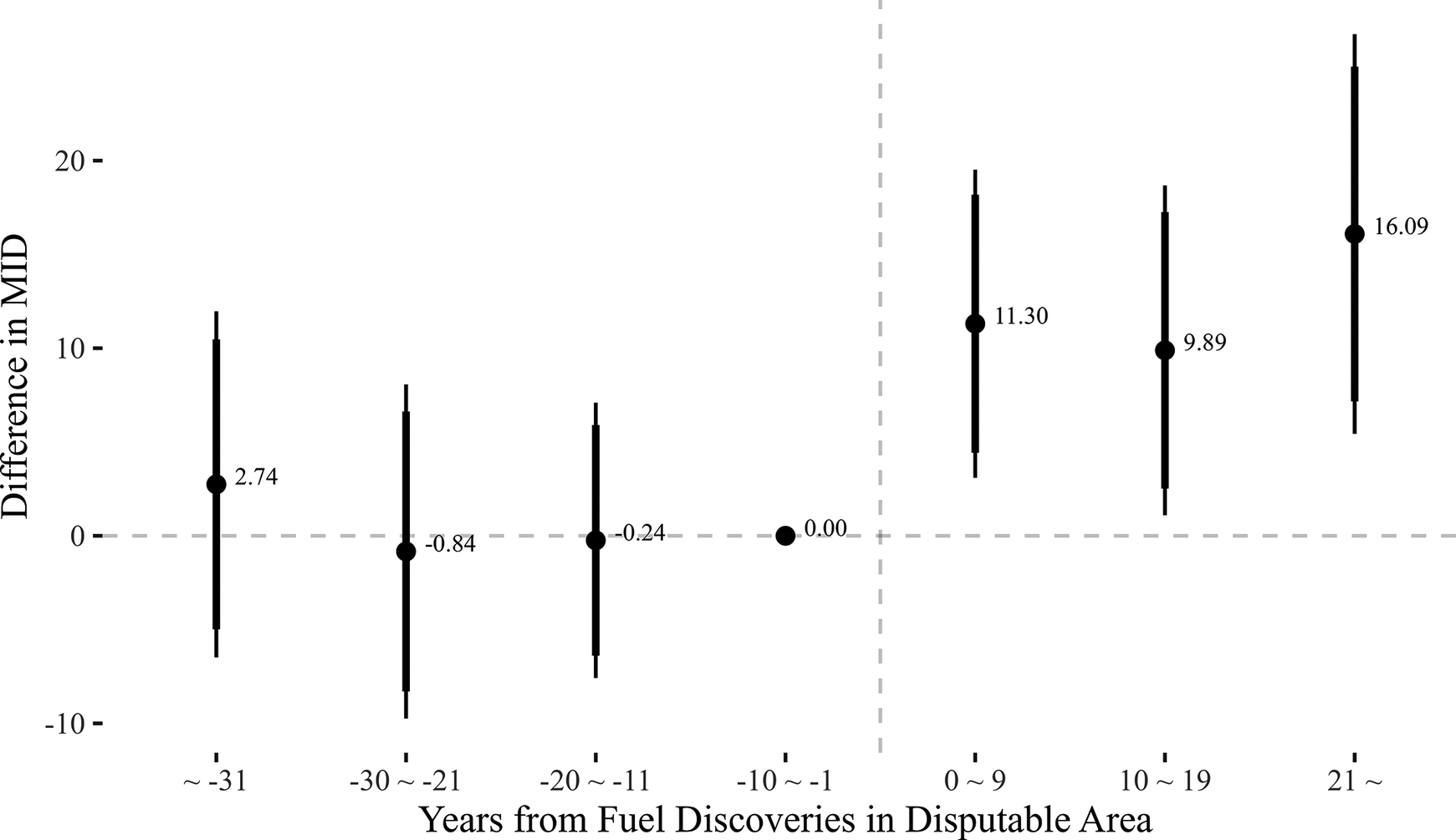

Figure 4 shows the results of the event study. The difference in the likelihood of MIDs between the treated and control dyads is displayed for each decade from giant fuel discoveries in disputable areas.Footnote 46 As seen in Figure 4, the MIDs increased in the treated dyads after disputable fuel discoveries, and the effect persisted for decades. Moreover, there were no significant differences before the treatment, implying that the states’ anticipatory actions were, if any, negligible, and that the common trend assumption likely holds.Footnote 47

Figure 4. Event Study

Note: The figure shows the results of an event study, where the treatment variables

![]() $ discover{y}_{disputable, ijt} $

and

$ discover{y}_{disputable, ijt} $

and

![]() $ discover{y}_{\neg disputable, ijt} $

are decomposed to dummies for each decade from giant fuel discoveries in disputable and non-disputable areas, respectively. A decade before giant fuel discovery is used as a reference group. The coefficient values are in a percentage point scale. The thick and thin vertical bars are 90% and 95% confidence intervals, respectively. The standard errors are two-way clustered by country

$ discover{y}_{\neg disputable, ijt} $

are decomposed to dummies for each decade from giant fuel discoveries in disputable and non-disputable areas, respectively. A decade before giant fuel discovery is used as a reference group. The coefficient values are in a percentage point scale. The thick and thin vertical bars are 90% and 95% confidence intervals, respectively. The standard errors are two-way clustered by country

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

.

$ j $

.

In Table A4-3 in the Supplementary Material, I also analyze the effects of giant fuel discoveries on disputes. While fuel discoveries in non-disputable areas had no noticeable effects, those in lost lands increased land and maritime disputes. In Table A4-4 in the Supplementary Material, I interact

![]() $ discover{y}_{all, ijt} $

and

$ discover{y}_{all, ijt} $

and

![]() $ dis{putable}_{ijt} $

in Equation 1, finding no interactive effects.Footnote

48 This result implies that the locations of fuel discoveries—whether they are discovered in disputable areas—are crucial for understanding their effects on MIDs. Finally, in Table A4-5 in the Supplementary Material, I analyze the intensive and extensive margins of the effects by adding the counts of fuel discoveries in disputable and non-disputable areas to Equation 2. The results indicate that the first discoveries in disputable areas increased MID, while further discoveries in those areas did not have additional effects.

$ dis{putable}_{ijt} $

in Equation 1, finding no interactive effects.Footnote

48 This result implies that the locations of fuel discoveries—whether they are discovered in disputable areas—are crucial for understanding their effects on MIDs. Finally, in Table A4-5 in the Supplementary Material, I analyze the intensive and extensive margins of the effects by adding the counts of fuel discoveries in disputable and non-disputable areas to Equation 2. The results indicate that the first discoveries in disputable areas increased MID, while further discoveries in those areas did not have additional effects.

Validity Checks

I check whether the treated and control dyads exhibit similar trends in the covariate values before the treatment. Because I use the DiD, I only include time-varying covariates, such as alliance (Gibler Reference Gibler2008), military capabilities (Singer Reference Singer1988), democracies, state ownership of the economy, GDP per capita, and population size (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Alizada and Altman2021). As shown in Figure A5-1 in the Supplementary Material, the covariate trends are similar except for long years before the treatment. In later robustness checks, I control the covariates or remove the observations long before the treatment and find similar results.

In Figure A5-2 in the Supplementary Material, I also conduct placebo tests by using failed wildcat drills (i.e., no discoveries of fuel resources) and minor discoveries (discoveries of less than 500 million barrels or unknown amounts) as placebo treatments. Because those placebos are less salient, they should not greatly affect MIDs. The estimates are indeed much weaker. The weak effects on fuel discoveries of unknown amounts also suggest that reporting biases in the oil data are less concerning.Footnote 49

However, there are remaining concerns. Unobserved confounders can affect not only the quantity but also the quality of wildcat drills. For example, restrictions on foreign direct investment may not only reduce the number of wildcat drills, but they may also hamper the use of the latest drilling technologies. I address this concern in three additional analyses. First, in Table A5-1 in the Supplementary Material (column 1), I control the average underground depth of wildcat drills (km) as a proxy of drilling technologies. Second, in Table A5-1 in the Supplementary Material (column 2), I change the estimand to the difference between the effects of giant fuel discoveries in disputable and non-disputable areas (i.e., triple differences; DDD).Footnote 50 The difference cancels out the confounding effects if a country uses similar drilling technologies in disputable and non-disputable areas. Third, in Table A5-1 in the Supplementary Material (column 3), I relax the assumption; given the number of wildcat drills and discoveries of certain amounts of fuel resources, it is random whether those discoveries are small or giant.Footnote 51 This addresses the concern as far as drilling technologies affect the discovery rates but not discovery amounts. The results are robust to any of those changes.

Another and perhaps more important concern is that disputable areas are not randomly assigned. Because disputable areas are often located near national borders, the results might reflect the effect of giant fuel discoveries near national borders. States, for instance, may fight for fuel fields around national borders, because it is tactically easier to conquer those fields (Caselli, Morelli, and Rohner Reference Caselli, Morelli and Rohner2015). I account for this possibility by excluding giant fuel discoveries within 100 km of national borders from the treatment and control variables. As shown in Table A5-1 in the Supplementary Material (column 4), the results are robust to this change.

Similarly, disputable and non-disputable areas may have different geographical and other characteristics. Disputable seas, for instance, concentrate on shallow waters. Foreign ethnic minorities are also more common in ethnically diverse regions. In Table A5-1 in the Supplementary Material (column 5), I alleviate this concern by controlling the indicator of giant fuel discoveries within 300 km of disputable areas (excluding disputable areas). These fields are not disputable, but the proximity implies that their geographical and other characteristics are similar to those in disputable areas. The results remain robust to this change.

Finally, I extensively implement the recent methods for staggered DiD. The TWFE model does not estimate the average treatment effect on the treated when the effects are heterogeneous across units or over time (Goodman-Bacon Reference Goodman-Bacon2021). Recent studies propose alternative estimators that are valid even with heterogeneous effects (see Chiu et al. Reference Chiu, Lan, Liu and Xu2025; Xu Reference Xu, Box-Steffensmeier, Christenson and Sinclair-Chapman2023 for reviews). In Table A6-1 in the Supplementary Material, I implement those methods and find similar results across eight estimators.Footnote 52 These results are consistent with the findings by Chiu et al. (Reference Chiu, Lan, Liu and Xu2025); heterogeneous treatment effects are less concerning than violating more critical assumptions. In Figure A6-1 in the Supplementary Material, I also conduct a sensitivity check proposed by Rambachan and Roth (Reference Rambachan and Roth2023), showing that the event-study estimates (i.e., Figure 4) are robust to minor violations of the common trend assumption.

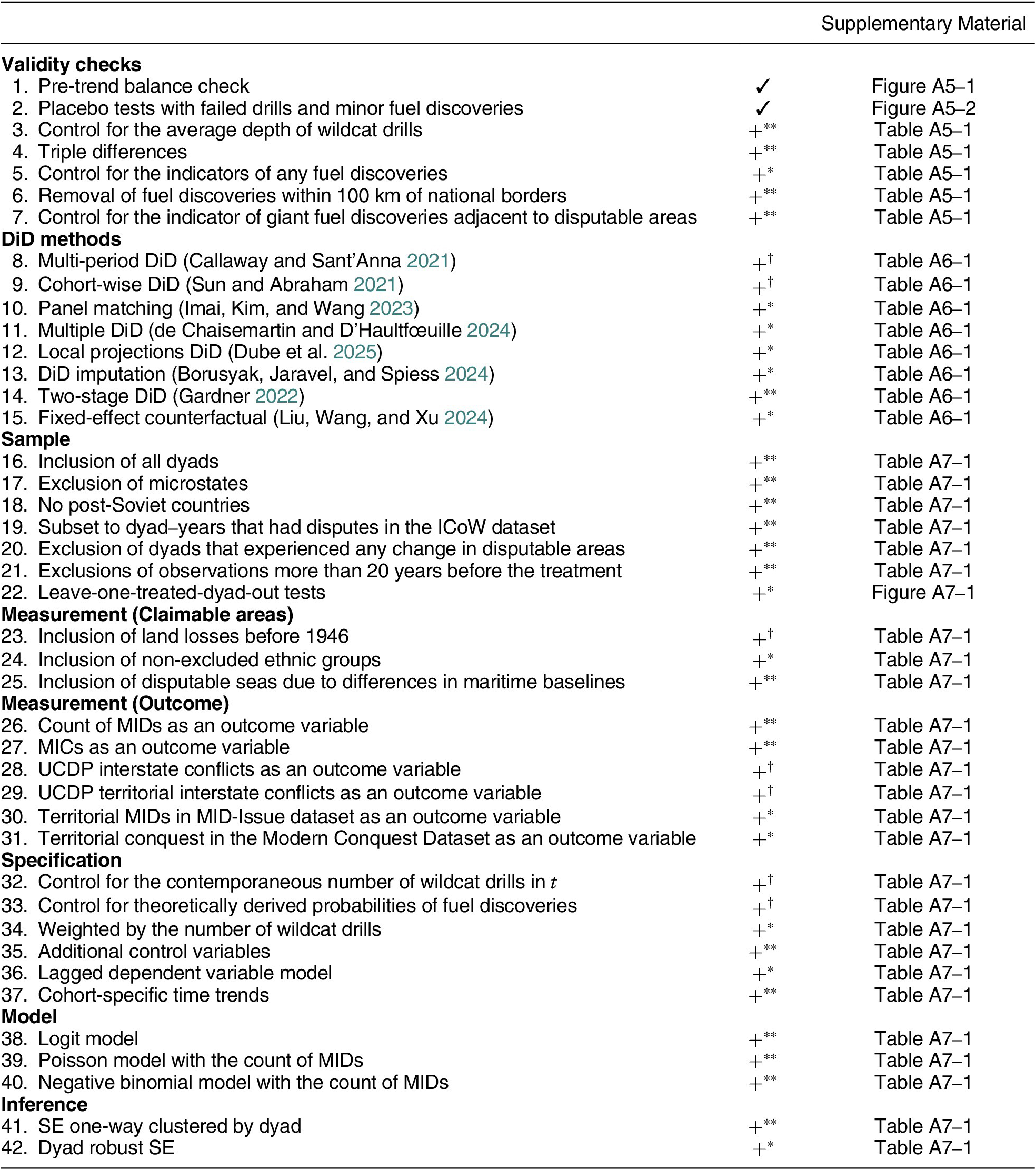

Robustness Checks

I conduct an extensive set of robustness checks, summarized in Table 4 and detailed in Table A7-1 in the Supplementary Material. The main results are robust to the changes in the sample, measurement,Footnote

53 specifications, and standard errors. In Figure A7-1 in the Supplementary Material, I also remove each treated dyad from the sample and estimate

![]() $ {\delta}_1 $

in Equation 2. The main results are robust to the omission of any treated dyad.

$ {\delta}_1 $

in Equation 2. The main results are robust to the omission of any treated dyad.

Table 4. Validity and Robustness Checks

Note: The additional control variables include alliance, relative difference in military capabilities, and the maximum and minimum of democracy indexes, state ownership of the economy, GDP per capita, and population sizes. Summary of validity and robustness checks in the appendix.

![]() $ \ast \ast p<0.01;\ast p<0.05;\dagger p<0.1 $

.

$ \ast \ast p<0.01;\ast p<0.05;\dagger p<0.1 $

.

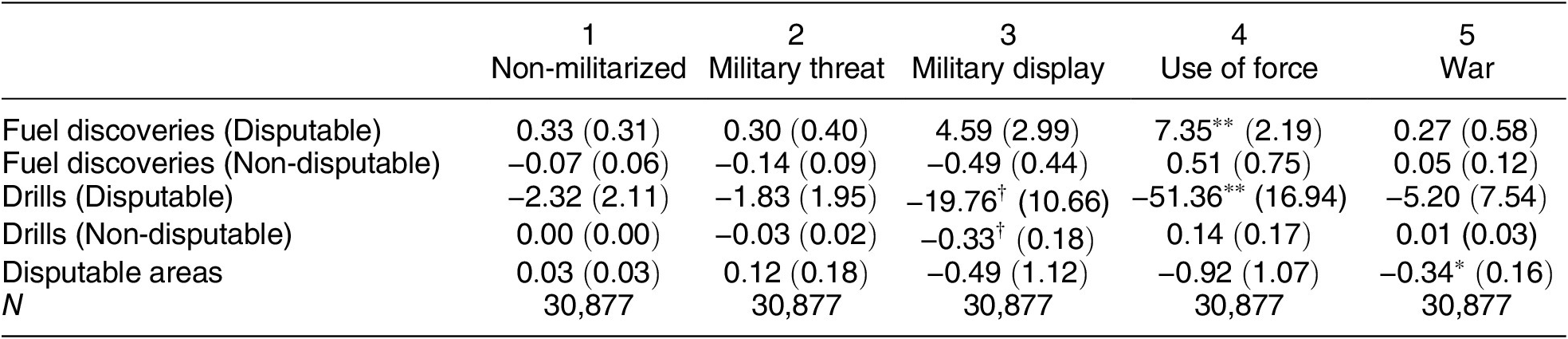

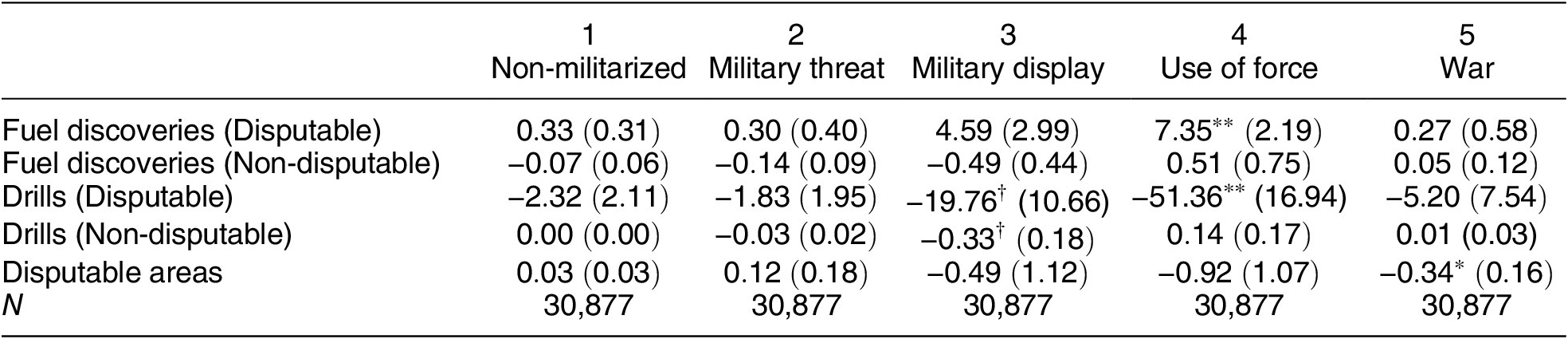

Decomposed Effects

I first disaggregate the MIDs into each type of military action: non-military actions, military threats, displays, use of military forces (i.e., minor clashes), and war.Footnote 54 As seen in Table 5, the main results are mostly driven by military clashes. By contrast, although the point estimate for military display is relatively large, those for non-militarized actions, military threat, and war are close to zero. The null effect on war is consistent with Meierding (Reference Meierding2016a; Reference Meierding, Van de Graaf, Sovacool, Ghosh, Kern and Klare2016b; Reference Meierding2020); fuel resources did not cause war but only caused “oil spats.” The null effect on military threat implies that states did take actual military actions to control fuel resources (i.e., logics of costly peace, hold-up problems, issue indivisibility) or to credibly signal their interests in discovered resources (i.e., logic of signaling).

Table 5. Effects by MID Categories

Note: The outcome variable is each type of Militarized Interstate Disputes (MIDs). The coefficient values and standard errors are in a percentage point scale. The models include dyad- and year-fixed effects. The standard errors are two-way clustered by country

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

.

$ j $

.

![]() $ \ast \ast p<0.01;\ast p<0.05;\dagger p<0.1 $

.

$ \ast \ast p<0.01;\ast p<0.05;\dagger p<0.1 $

.

Second, I also decompose the outcome into territorial and non-territorial MIDs.Footnote 55 As seen in Figure 5, fuel discoveries in disputable areas increased both territorial and non-territorial MIDs. To a lesser extent, Figure 5 also indicates that fuel discoveries in disputable areas first increased territorial MIDs (solid bars in Figure 5) and then increased non-territorial MIDs (dashed bars in Figure 5). This may imply that territorial MIDs spilled over to non-territorial MIDs. As I have discussed, when fuel discoveries flare petro-nationalism, it can justify non-territorial military actions against its opponent (e.g., policy or regime changes).

Figure 5. Effects on Territorial and Non-Territorial MIDs

Note: The figure shows the results of an event study, where the treatment variables

![]() $ discover{y}_{disputable, ijt} $

and

$ discover{y}_{disputable, ijt} $

and

![]() $ discover{y}_{\neg disputable, ijt} $

are decomposed to dummies for each decade from giant fuel discoveries in disputable and non-disputable areas, respectively. A decade before giant fuel discovery is used as a reference group. The coefficient values are in a percentage point scale. The thick and thin vertical bars are 90% and 95% confidence intervals, respectively. The standard errors are two-way clustered by country

$ discover{y}_{\neg disputable, ijt} $

are decomposed to dummies for each decade from giant fuel discoveries in disputable and non-disputable areas, respectively. A decade before giant fuel discovery is used as a reference group. The coefficient values are in a percentage point scale. The thick and thin vertical bars are 90% and 95% confidence intervals, respectively. The standard errors are two-way clustered by country

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

.

$ j $

.

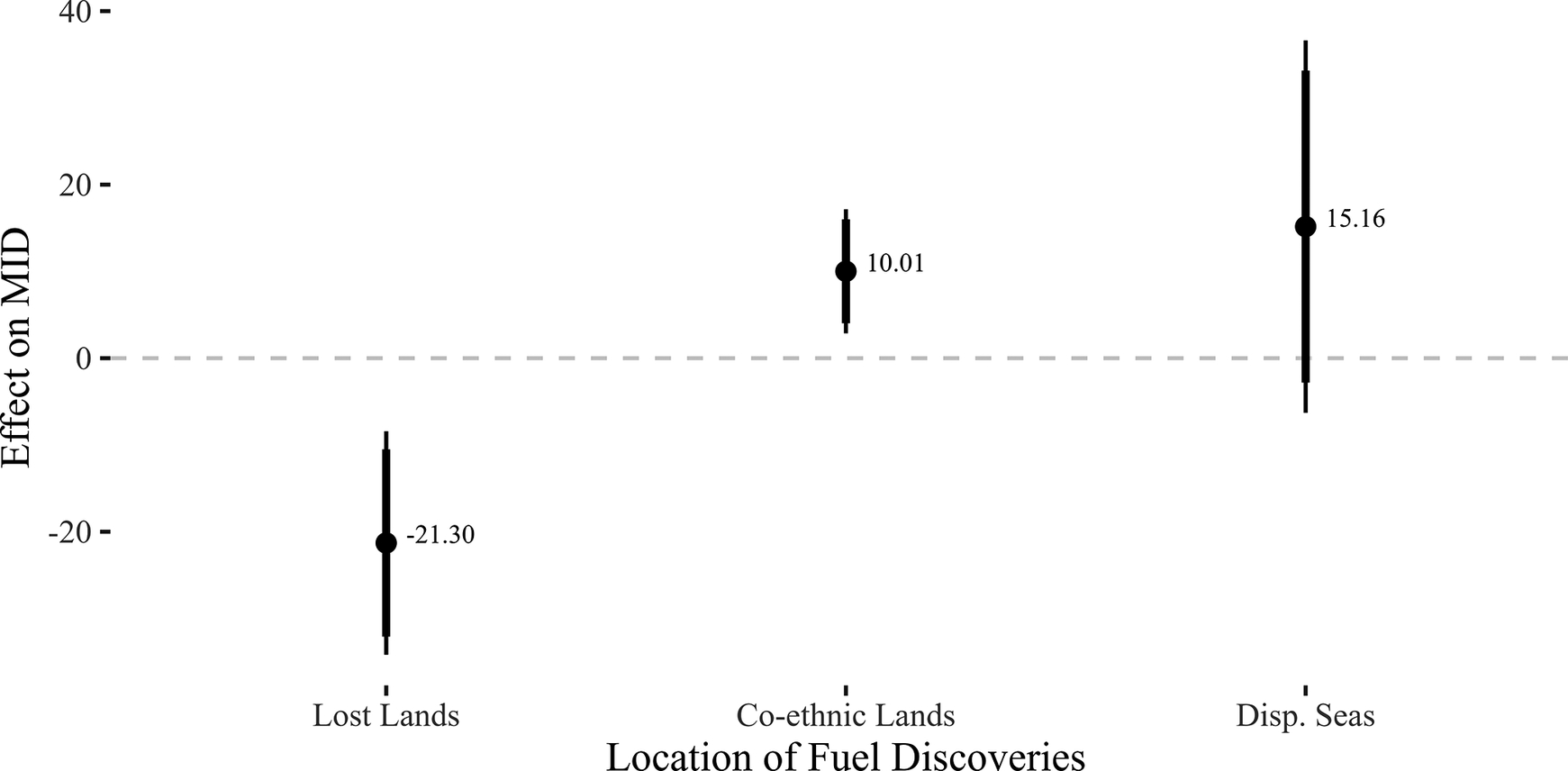

Third, I disaggregate the treatment variable—fuel discoveries in disputable areas—to those in lost lands, foreign co-ethnic lands, and disputable seas. As shown in Figure 6, fuel discoveries in foreign co-ethnic lands increased MIDs. Although the point estimate for fuel discoveries in disputable seas is the largest, the standard error is also large. The sample contains only a few cases of fuel discoveries in disputable seas, resulting in large standard errors. Finally, while fuel discoveries in lost lands increased land and maritime disputes (Table A4-3 in the Supplementary Material), they reduced MIDs (first column of Figure 6). These results imply that even though fuel discoveries reignited disputes over lost lands, states avoided re-escalation, possibly because they learned from their previous experiences of military conflicts that had led to the loss of their territories.

Figure 6. Effects by Disputability Types

Note: The figure shows the effects of giant fuel discoveries in lost lands, foreign co-ethnic lands, and disputable seas on MIDs, respectively. The coefficient values are in a percentage point scale. The thick and thin vertical bars are 90% and 95% confidence intervals, respectively. The standard errors are two-way clustered by country

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

.

$ j $

.

Mechanism Checks

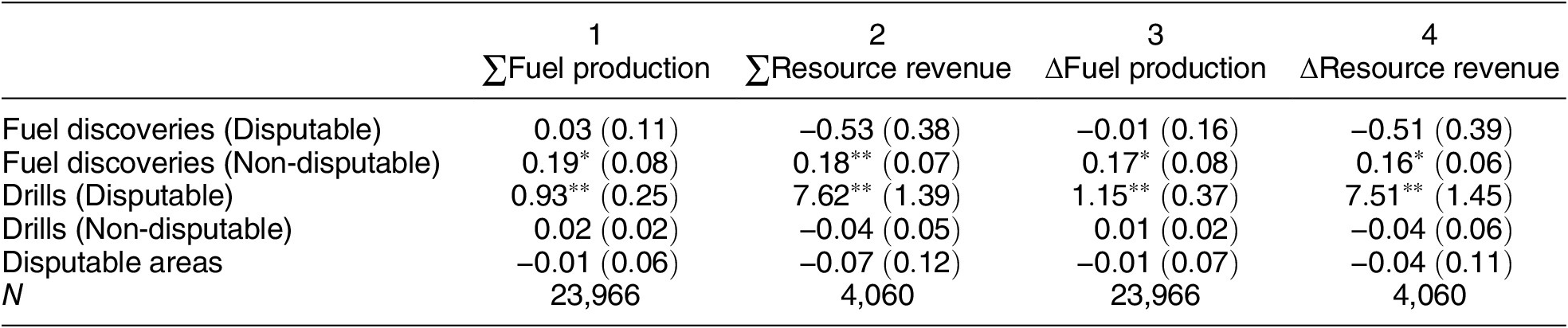

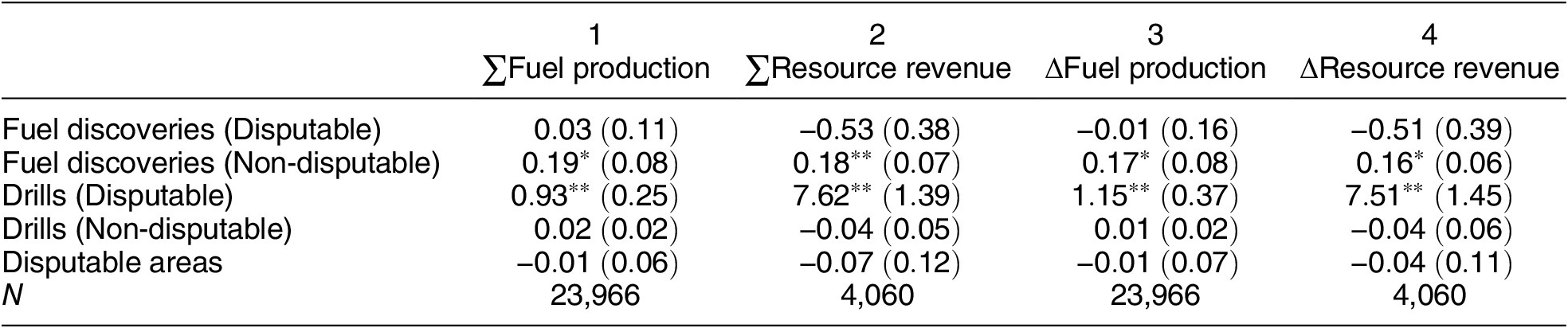

In the theory section, I have postulated two mechanisms: tangible and intangible salience. Although directly testing the mechanisms is difficult, I provide suggestive evidence. First, the tangible salience mechanism assumes that fuel resources are underutilized in disputable areas; this economic inefficiency creates positive incentives for costly conflicts. Thus, fuel discoveries in disputable areas should not increase fuel production or governments’ resource revenues. I thus estimate the effects on fuel production and resource revenue. The data on fuel production and resource revenues are derived from Ross and Mahdavi (Reference Ross and Mahdavi2015) and the Government Revenue Dataset (GRD; McNabb, Oppel, and Chachu Reference McNabb, Oppel and Chachu2023). The GRD is available only in a limited number of countries after 1980, resulting in many missing values. For comparability, I transform both variables into global shares. Finally, because the unit of analysis is a dyad, I use the sum and relative difference within a dyad (denoted by

![]() $ \sum $

and

$ \sum $

and

![]() $ \Delta $

, respectively).Footnote

56 Table 6 indicates that while fuel discoveries in non-disputable areas increased fuel production and resource revenues and widened the gaps in dyads (second row), fuel discoveries in disputable areas had no equivalent effects, and the point estimates are close to zero or even negative (first row). These results suggest that fuel resources are underutilized in disputable areas. Thus, although the evidence is indirect, the results are consistent with the tangible salience mechanisms.

$ \Delta $

, respectively).Footnote

56 Table 6 indicates that while fuel discoveries in non-disputable areas increased fuel production and resource revenues and widened the gaps in dyads (second row), fuel discoveries in disputable areas had no equivalent effects, and the point estimates are close to zero or even negative (first row). These results suggest that fuel resources are underutilized in disputable areas. Thus, although the evidence is indirect, the results are consistent with the tangible salience mechanisms.

Table 6. Effects of Giant Fuel Discoveries on Fuel Production and Revenue

Note: The outcome variables are the dyadic sums (

![]() $ \sum $

) or relative differences (

$ \sum $

) or relative differences (

![]() $ \Delta $

) in the global share of fuel production or resource revenue. The models include dyad- and year-fixed effects. The standard errors are two-way clustered by country

$ \Delta $

) in the global share of fuel production or resource revenue. The models include dyad- and year-fixed effects. The standard errors are two-way clustered by country

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

.

$ j $

.

![]() $ \ast \ast p<0.01;\ast p<0.05;\dagger p<0.1 $

.

$ \ast \ast p<0.01;\ast p<0.05;\dagger p<0.1 $

.

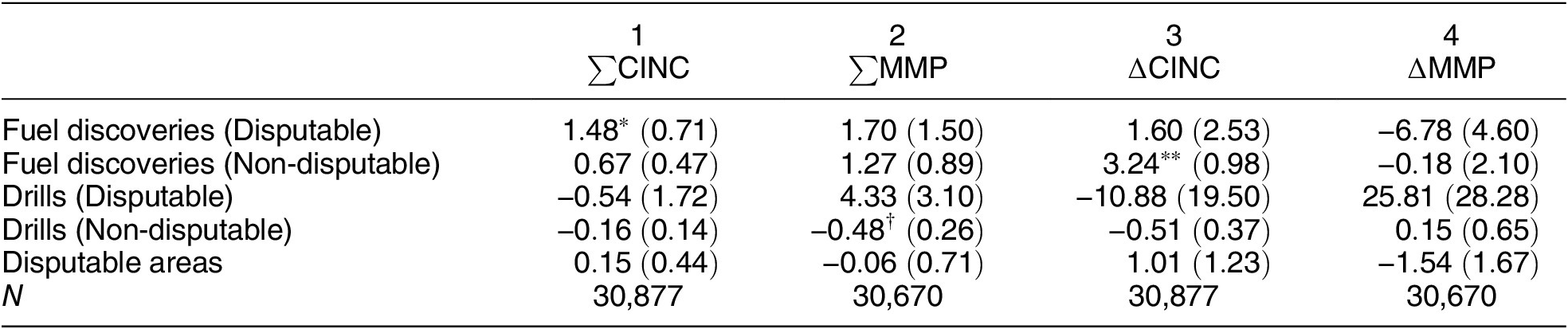

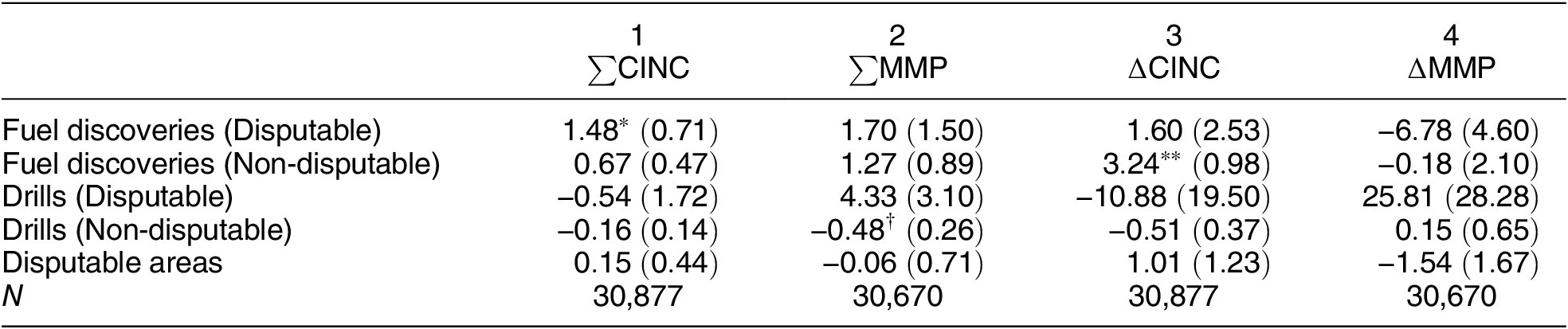

Second, I examine the effects of giant fuel discoveries on military capability. Because fuel discoveries in disputable areas do not substantially change fuel production or government revenues, any effect on military capability can be considered states’ mobilization efforts. The data on military capabilities are derived from the Composite Index of National Capability (CINC) by the CoW and the Material Military Power (MMP) index by Souva (Reference Souva2023).Footnote 57 Similar to Table 6, I transform the variables to global share, calculate the sum and relative difference within each dyad, and multiply them by 100. Table 7 provides suggestive evidence that giant fuel discoveries in disputable areas increased the total amount of military capabilities without entailing substantial changes in their differences. Although the estimates are imprecise with the MMP data, the pattern is similar. Together with Table 6, these results imply that giant fuel discoveries in disputable areas incentivized states to expand their military without financing it. This interpretation is consistent with the tangible and intangible salience mechanisms; higher salience should motivate the states to arm and compete for the resources.Footnote 58

Table 7. Effects of Giant Fuel Discoveries on Military Capabilities

Note: The outcome variables are the dyadic sums (

![]() $ \sum $

) or relative differences (

$ \sum $

) or relative differences (

![]() $ \Delta $

) in the global shares of military capability indexes (CINC or MMP). The coefficients are standardized. The models include dyad- and year-fixed effects. The standard errors are two-way clustered by country

$ \Delta $

) in the global shares of military capability indexes (CINC or MMP). The coefficients are standardized. The models include dyad- and year-fixed effects. The standard errors are two-way clustered by country

![]() $ i $

and

$ i $

and

![]() $ j $

.

$ j $

.

![]() $ \ast \ast p<0.01;\ast p<0.05;\dagger p<0.1 $

.

$ \ast \ast p<0.01;\ast p<0.05;\dagger p<0.1 $

.