Introduction

UK politics had a rather tumultuous year. Dominated by a referendum on membership of the EU, events in 2016 had significant consequences for domestic and international politics. In addition to voting to exit the EU, the country has witnessed leadership elections, the selection of a new prime minister and cabinet, a new London Mayor and key policy decisions on the country's nuclear deterrent and infrastructure.

Election report

The electoral report is dominated by the referendum on membership of the EU that took place on 23 June 2016. This vote, promised in a manifesto commitment made by the Conservative Party in 2015, asked voters ‘Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?’. The result saw 52 per cent of the population voting to leave the EU, defying the predictions of YouGov, ComRes and IpsosMori polls (UK Polling Report 2016). In addition to having seismic implications for the future of British politics, the vote also revealed the presence of a deep-seated attitudinal divide within the population.

Clear divisions can be found within the disaggregated data. While the leave campaign won more than 50 per cent of the vote in the majority of counting regions, there were notable exceptions with London, Scotland and Northern Ireland voting to remain. Within many cities, communities and families the issue was highly divisive and produced polarised results. The motivation for people's votes was undoubtedly connected to growing Euroscepticism, yet data also reveals economic and social drives at play. In the towns where the vote for Brexit reached its peak – such as the northern cities of Hartlepool, Stoke-on-Trent and Doncaster – economic deprivation was high and levels of education low. In contrast, in areas with high levels of support for remain – such as the London boroughs of Lambeth and Islington and the city of Cambridge – voters had university degrees, professional jobs and higher median income. Attitudinal differences could also be found, with leave voters voicing more socially conservative outlooks, particularly with regards to immigration and national identity, than their remain counterparts. Importantly for British politics, these attitudes transcended usual party voting lines, meaning that those voting for Brexit were a majority in most Conservative and Labour-held seats (Hanratty Reference Hanratty2016).

The two campaigns launched for the referendum combined economic, social and attitudinal messages in attempts to win appeal. The remain campaign was led by Prime Minister David Cameron (Cons) and had high profile contributions from Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon (SNP), and former British Prime Ministers Tony Blair (Lab) and John Major (Cons), while the leave campaign was fronted by former Mayor of London Boris Johnson (Cons), UKIP leader Nigel Farage and Labour MP Gisela Stewart. Both campaigns therefore spanned traditional party divides, but they also both struggled to distil the implications of the vote. Whilst Remain argued that EU membership would deliver 790,000 extra jobs by 2030, the Leave campaign argued that the £350 million sent each week to the EU could be spent on national services such as the NHS. These competing claims led 28 per cent of respondents to argue that they did not have enough information to be able to make an informed decision about how to vote in the referendum (Electoral Commission 2016a: 45).

Following the result, David Cameron resigned as prime minister and leader of the Conservative Party, arguing that the country required fresh leadership. On the same day Britain's currency slumped to a 31-year low, bringing about considerable change in the dynamics of UK politics.

Table 1. Results of the referendum on Membership of the EU in the United Kingdom in 2016

Source: Electoral Commission (2016a).

Other elections

In addition, elections took place for the Mayor of London, the London Assembly, devolved administrations in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, and local government in England on 5 May. Following Boris Johnson's resignation as Mayor of London a high profile campaign was fought between Sadiq Khan (Lab) and Zac Goldsmith (Cons), resulting in victory for the Labour candidate. Khan gained 57 per cent of the vote, surpassing Boris Johnson's 52 per cent vote share in 2012. The Assembly elections saw similar success for Labour, with the party retaining a total of 12 seats of the 25 available. Elections also occurred within the Scottish Parliament, Welsh and Northern Ireland Assemblies. In Scotland the SNP saw its majority reduced, losing six seats compared to the 2011 election. The Conservatives made the most notable change, becoming the second largest party in Scotland and beating Labour into third place (BBC 2016a). This was the first Scottish Parliament election at which 16 and 17 year olds were entitled to vote. Approximately 80,000 registered, accounting for 2 per cent of the electorate (Electoral Commission 2016b: 4). In Wales, Labour retained its dominance, but UKIP notably gained 7 seats, recording 13 per cent of the vote. In Northern Ireland there was limited change, with the nationalist parties the SDLP losing 2 seats and Sinn Féin 1 seat, to the People before Profit Alliance and the Green Party (BBC 2016b).

In addition, elections were also held on 5 May for some local councils, for Police and Crime Commissioners (PCC) and, in some cases, for elected mayors. Turnout was notably low, with 27 per cent for the PCC elections and 34 per cent for English local government elections. At the PCC elections, 72 per cent reported knowing not very much or nothing at all about the elections, perhaps explaining these results (Electoral Commission 2016c: 22). At the local elections, both Labour and the Conservatives lost seats, but the Conservatives lost control of only one council – to the Liberal Democrats – resulting in minimal change.

Cabinet report

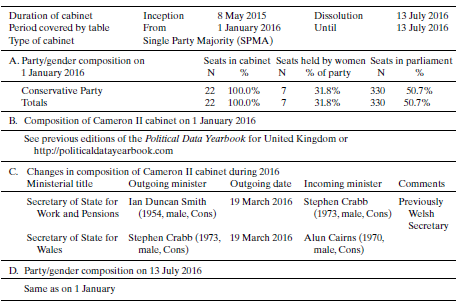

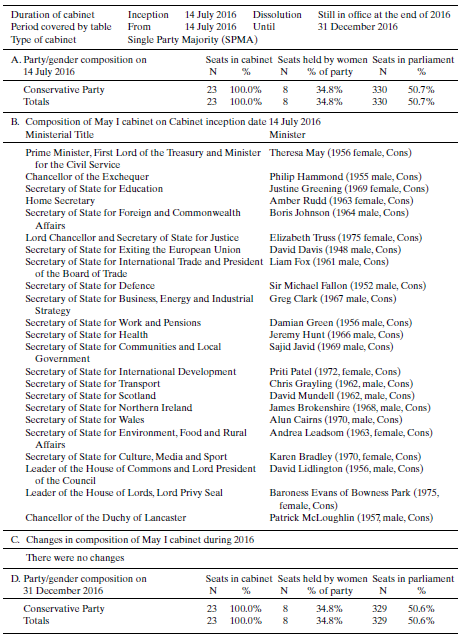

The election of Theresa May in 2016 bought an end to the Cameron era and invited significant change in the cabinet. Her new cabinet reflected the outcome of the EU referendum vote. New posts of Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union and Secretary of State for International Trade and President of the Board of Trade were created. The previous Ministry of Energy and Climate Change was also abolished, with competencies for energy combined within the portfolio of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. The key international posts of Foreign Secretary and International Trade Secretary were awarded to Boris Johnson and David Davis, respectively, both high profile Brexit campaigners. Gender composition changed fractionally, with 35 per cent of posts filled by women in a newly expanded cabinet of 23 posts.

Table 2. Cabinet composition of Cameron II in the United Kingdom in 2016

Source: UK Parliament (2016).

Parliament report

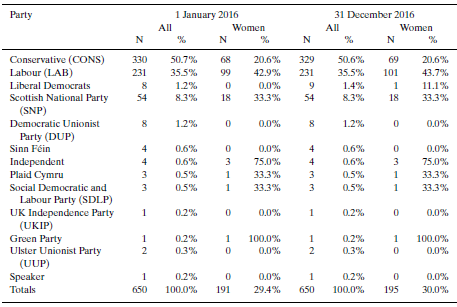

There were seven by-elections during 2016. The most notable was that triggered by the resignation of Zac Goldsmith in Richmond Park (who contested the London mayoral election) from the Conservatives following the decision to build a third runway at Heathrow airport. The seat was gained by the Liberal Democrats, who overturned a 23,015 majority.

Table 4. Party and gender composition of the lower house of parliament (House of Commons) in the United Kingdom in 2016

Source: UK Parliament 2016b.

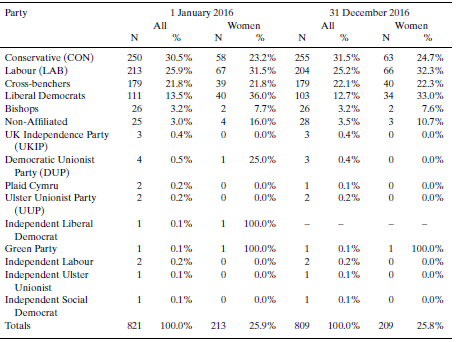

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the upper house of parliament (House of Lords) in the United Kingdom in 2016

Source: UK Parliament (2016b).

Political party report

Political parties across the spectrum have witnessed leadership changes or challenges in 2016. Most prominently, Theresa May replaced David Cameron, becoming the UK's second female prime minister. The referendum also prompted the resignation of UKIP leader Nigel Farage, leading to the election of first Diane James, who resigned after 18 days, and then Paul Nuttall. The Labour Party also conducted another leadership election. Owen Smith challenged Jeremy Corbyn for the leadership after mass resignations from Labour's front bench. Smith was, however, unable to win, with Corbyn securing 62 per cent of the vote (Labour Party 2016).

Institutional change report

In the wake of the Brexit referendum the ‘Exiting the EU Select Committee’ was created to scrutinise the work of the new government department. Chaired by Hilary Benn, the committee constituted 21 members, making it larger than other committees in parliament. The government also announced proposals for electoral boundary reform that will be implemented in 2018. The proposals detail plans to reduce the number of MPs from 650 to 600 (Boundary Commission 2016).

Issues in national politics

Alongside the omnipresent referendum debate, British politics was preoccupied with debates around renewal of the country's nuclear deterrent, infrastructure investment, grammar schools and the future of the union.

In July, MPs voted on the renewal of the country's nuclear deterrent Trident. The decision to invest around £31 billion in the scheme was backed by 472 to 117 MPs following extensive public debate and pronounced opposition from the Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn. The government also announced plans in October for further investment in a third runway at Heathrow airport. After years of equivocation, and substantial debate within the Conservative Party, ministers announced plans to expand airport capacity at the site. The Conservative Party was also beset with debate following Theresa May's announcement of an end to the ban on new grammar schools. This ended decades of cross-party consensus on education policy, enabling the creation of new selective schools.

Debate also re-emerged over the future of the union. Following the outcome of the referendum, and in particular Scotland's unanimous support for EU membership, the First Minister of Scotland Nicola Sturgeon, raised the prospect of a second referendum on Scottish independence. Initial polling in July suggested that 53 per cent of respondents said they would vote for Scotland to remain in the UK (Khomami Reference Khomami2016), but the SNP have continued to raise this possibility.