Introduction

According to a minimal concept of democracy, elections should allow citizens to replace the incumbent government. The accountability model suggests that voters evaluate the performance of governing parties and reward or punish them accordingly. This notion of democracy is simple and requires only that citizens know who was responsible for policy making. Unfortunately, this is no trivial request: Under minority governments, it is also necessary to hold pseudo‐opposition parties, that is, parties supporting minority rule (Hjermitslev, Reference Hjermitslev2022), accountable.

In the field of accountability, minority governments have long been a parenthesis. However, roughly one‐third of cabinets in advanced parliamentary democracies have minority status (Strøm, Reference Strøm1990, p. 59) and this number is increasing as parties across the European continent are struggling more and more to form viable majority governments (Krauss & Thürk, Reference Krauss and Thürk2022). Thus, minority governments are not a peripheral phenomenon, but a regular feature of parliamentary politics, which deserves scholarly attention.

A key component of Strøm's explanation for minority governments is that sometimes rational parties choose to act as support parties because the cost of governing outweighs the benefits. In particular, when the institutional environment enables high parliamentary influence, opposition parties can realize their policy‐seeking goals without actually joining the government (Strøm, Reference Strøm1990). Simultaneously, we know that serving as a junior member of a coalition government is generally associated with substantial electoral costs (Hjermitslev, Reference Hjermitslev2020), so it seems logical that small parties might prefer the role of support party. As Andeweg writes, ‘given the growing electoral risks of government participation, parties may becoming less eager to join the government, and they may come to see pseudo‐opposition as a way of “having your cake and eating it too’” (Andeweg, Reference Andeweg, Müller and Narud2013, p. 109).

Studies on minority governments and political accountability are usually conducted separately. In this study, I bring these topics together to better understand the costs of governing for parties that support the minority government in parliament but are not formally part of the government (hereafter called support parties). The purpose of this article is to explore how the evaluations and electoral fortunes of opposition parties versus support parties are affected by the performance of the government. Do voters acknowledge the responsibility for government policy of the latter?

The results reveal an interesting pattern. Voters who are dissatisfied with government performance tend to dislike the support parties more than they dislike the junior coalition members. This affective response matches recent findings showing that coalition building and cooperation makes supporters of a governing party rate the other parties more positively (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023) and suggests that voters recognize the role of support parties and lump them in with the government. Furthermore, when it comes to voting behaviour, which is presumably what strategic parties care most about, support parties are punished by voters who are dissatisfied with the minority government. In short, support parties are clearly associated with the governing parties and they are suffering the same electoral penalties.

In the next section, I briefly review the existing literature on accountability under power sharing and minority governments, before presenting two hypotheses. I then describe the measurements and data sources and discuss the multilevel structure of my data. Next, I describe findings of both multilevel linear and conditional logit regressions. Finally, I conclude and discuss the implications of my findings.

Accountability under minority governments

In any parliamentary situation where no single party holds a majority of seats, government formation requires coalition building of some sort. However, this does not necessarily imply a governing coalition (Strøm, Reference Strøm1990, p. 24). For a minority government to pass legislation, at least one opposition party has to be involved in a so‐called legislative coalition to form the parliamentary majority. Arguably, these parties share responsibility for government survival and for policy outcomes (Thesen, Reference Thesen2016). Due to their continuous cooperation with and commitment to the government, support parties have a larger influence on government policy than other opposition parties.

The retrospective voting literature has primarily operated with a simple dichotomous division between opposition and government. For instance, Powell and Whitten (Reference Powell and Whitten1993) argued that the clarity of government responsibility can be impaired by certain institutional features such as minority governments. Using economic indicators, they demonstrated that voters are less likely to punish or reward the government when the parties are not clearly and single handedly responsible for the country's economic performance.

Some scholars argue that retrospective voting depends on voters’ perceptions of the policy responsibility among coalition partners: Fisher and Hobolt (Reference Fisher and Hobolt2010) found that within coalition governments, the senior member is held more accountable than the other parties, although not as much as in a single‐party government. However, perhaps the governing parties are not the only ones with influence and responsibility? In particular, formal minority governments strike a deal with support parties, which receive concessions in return for permanent support (Andeweg, Reference Andeweg, Müller and Narud2013, p. 108; Strøm, Reference Strøm1990).

According to Strøm (Reference Strøm1990, pp. 61–62) there are several defining features of a formal support agreement: (1) Parliamentary support should be negotiated prior to the formation of the government, (2) it should make the difference between minority and majority status, and (3) the support party should make an explicit, comprehensive, and long‐term commitment to the policies and survival of the government. This commitment could come in the form of a written contract, as in contract parliamentarianism (Bale & Bergman, Reference Bale and Bergman2006), but it could also be verbal. Regardless of the form, support agreements serve to decrease uncertainty among the parties involved in governing. As a result, formal minority governments are as stable and durable as majority governments (Krauss & Thürk, Reference Krauss and Thürk2022) and perform equally well in terms of legislative agenda control (Thürk, Reference Thürk2022).

Bale and Bergman (Reference Bale and Bergman2006) suggest that support parties hope the arrangement will give them a reputation for being reliable and responsible, that it will be a stepping stone for joining a coalition later, and that voters will recognize their influence on policy. These are rather strong assumptions, which have not been backed by any empirical studies so far. In contrast, the Danish People's Party, which served as the parliamentary support of a right‐wing government for a full decade, represents a prominent example of a party explicitly pursuing the role as support party without any intentions of joining the cabinet. At the 2015 election, where the Danish People's Party came in second ahead of all other right‐wing parties, the party leader described the strategy in the following way: ‘In our assessment, we will not gain the biggest influence by participating in a government [...] but as a hopefully strong support party for the new government’ (Tromborg et al., Reference Tromborg, Stevenson and Fortunato2019).

As Müller (Reference Müller2022) points out, support parties have strong incentives for highlighting their unique party profile and distinguish themselves from the governing parties (see also Müller & König, Reference Müller and König2021; Tuttnauer & Wegmann, Reference Tuttnauer and Wegmann2022). It is thus quite likely that support parties have no ambitions of joining the cabinet but prefer their access to policy influence without being associated with and held responsible for government actions (Strøm, Reference Strøm1990). But can support parties really have their cake and eat it too?

Hypotheses

Tromborg et al. (Reference Tromborg, Stevenson and Fortunato2019) found that the identities of support parties are well known. While some voters perceive support parties as a separate category when given the option, support parties are clearly tied to the government in the minds of voters. Some even think of support parties as part of the government (Hjermitslev, Reference Hjermitslev2022; Tromborg et al., Reference Tromborg, Stevenson and Fortunato2019). Connecting that to recent findings suggesting that partisans have more positive feelings towards out‐parties that are co‐governing with their own party (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023), it seems plausible that a positive evaluation of the government would extend to support parties. This potential affective response is interesting because it reveals whether support parties are seen as credible alternatives to the government – one of the key tasks of opposition parties (Stiers, Reference Stiers2022), or rather as part of the government in‐group.

This leads to the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Voters who are dissatisfied with government performance feel less positively towards external support parties.

While affective responses cast much needed light on how voters understand political alliances, strategic parties should ultimately be concerned with whether a decrease in party sympathy will translate into policy responsibility and electoral punishment. Plescia and Kritzinger (Reference Plescia and Kritzinger2017) explored whether retrospective voting extends to opposition parties. They argued that voters consider the roles and obligations that opposition parties are expected to fulfill: the more satisfied a voter is with a party, the more likely they are to vote for it. Stiers (Reference Stiers2019) extended the analysis cross‐nationally and similarly found that satisfaction with a party significantly increases the likelihood of voting for it. However, these studies rely on general performance evaluations of parties, and it remains unclear whether they are connected to the policy outcomes the support parties were instrumental in bringing about. What type of behaviour are voters expecting from different opposition parties?

Stiers (Reference Stiers2022) argued that voters want opposition parties to scrutinize government action and provide constructive criticism. In contrast, Tuttnauer and Wegmann (Reference Tuttnauer and Wegmann2022) argued that opposition parties should take a conflictual stance and differentiate themselves ideologically. The latter finding suggests that support parties, much like coalition members, have strong electoral incentives to signal distinctiveness especially when elections are approaching (Müller & König, Reference Müller and König2021). Failure to do so will likely cause voters to lump the support parties in with the government and prevent them from representing a credible alternative.

Fortunato et al. (Reference Fortunato, Lin, Stevenson and Tromborg2021) found that voters attribute less policy influence to support parties than to governing parties but more than to opposition parties. Perceiving support parties as having intermediate responsibility is sensible and suggests that voters have a good intuition about policy‐making processes. However, Fortunato et al. (Reference Fortunato, Lin, Stevenson and Tromborg2021) did not test whether these perceptions translate into electoral behaviour. Lastly, Thesen (Reference Thesen2016) also questioned whether support parties could be affected by policy responsibility. His results indicated that the electoral performance of support parties was similar to other opposition parties and thus better than the government's electoral performance. This suggests that support parties are spared the electoral cost of governing, which they would most likely have incurred as junior members of a coalition (Hjermitslev, Reference Hjermitslev2020). However, Thesen (Reference Thesen2016) focused on aggregated election results and did not explore how voting patterns are moderated by perceptions of government performance. Thus, there is still ample room for testing the exact mechanism.

Hypothesis 2: Voters who are dissatisfied with government performance are less likely to vote for external support parties.

It follows from Hypothesis 2 that traditional retrospective voting should be muted under minority governments because the voters not only punish the government but also certain opposition members. Here as well, the existing evidence is mixed. In general, minority governments tend to perform better in subsequent elections (Strøm, Reference Strøm1990), but according to Fisher and Hobolt (Reference Fisher and Hobolt2010) the members of minority governments do not experience less retrospective voting than those of majority governments. An additional contribution of this current project is to shed new light on these contradictory findings.

Methods

To test the hypotheses, I rely on two different dependent variables. The first variable is the sympathy scores for each individual party. The party sympathy, also known as the thermometer score, is measured with the following survey question: ‘After I read the name of a political party, please rate it on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means you strongly dislike that party and 10 means that you strongly like that party.’ The party sympathy measures feelings towards all of the parties and thus constitutes a rich data source that is easy to handle statistically. However, it does not capture the implications for electoral competition directly so, secondly, I use vote choice in the current election which will be included in a conditional logit model, which is appropriate when the choice set varies across elections.

Turning now to the independent variables, I measure subjective perceptions of government performance with a survey item asking respondents to evaluate the incumbent government: ‘Now thinking about the performance of the government in general, how good or bad a job do you think the government did over the past [number of years since last government took office, before the current election] years?’ The exact translation of the survey item will vary by country, but it clearly refers to the incumbent government and not to a potential new government, which has taken office between the election and the time of the interview. I recode this ordinal variable into a dissatisfaction dummy variable taking 0 for ‘good job’ and 1 for ‘bad job’. I also estimated the models with the original variable treated as continuous (higher values indicating more dissatisfaction) – the results are robust and can be found in the online Appendix. All three measures are available in the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) waves 2, 3, and 5. I am including all systems in my sample.

I rely on the data collected by Thürk (Reference Thürk2022) in order to identify support parties. Thürk (Reference Thürk2022) included all parliamentary democracies which had experiences with minority governments in the past 25 years and legislative data for four consecutive terms. Using Strøm's definition of a formal minority government, she identified support parties for more than half of the 97 minority governments. I recode this information into a categorical variable taking one of four values: the party of the prime minister, junior member of the government, external support party, and ‘true’ opposition party. Please refer to the online Appendix for a full overview of minority governments included.

Additionally, I include control variables for the individual voter's perceived ideological distance between the party and the government and between themselves and the party. The latter is a crucial control to include since voters will be more positive towards, more likely to vote for, and more satisfied with the performance of parties that are ideologically close to them. Finally, I control for age, gender and education.

For all analyses, I stack the data such that the unit of analysis is the party‐voter. This pooled dataset has a complex multilevel structure. At the highest level are countries. Elections are then nested within countries, and voters are nested within elections. Voters and parties are crossed such that each voter evaluates multiple parties, and each party is evaluated by multiple voters. Parties are also crossed with surveys, since some but not all parties are competing in multiple elections. In the linear model, I include random effects for each of the relevant levels.

Specifically for the conditional logit model, one can only include ‘alternative‐specific variables’ such as government status and distance between party and voter or party and government. ‘Individual‐specific variables’, such as dissatisfaction, can only be interacted to test whether these might impact the relative preference for the alternative‐specific attributes (Kayser & Peress, Reference Kayser and Peress2012). Similarly, it is not possible to include any socio‐demographic control variables.

Results

Party sympathy

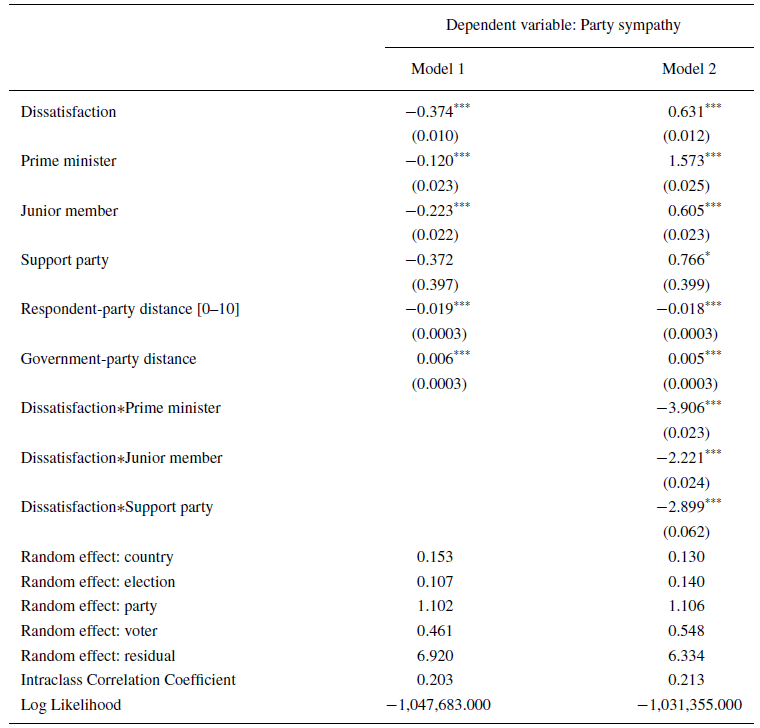

Model 1 includes all predictors but no interactions (see Table 1). Most of the unconditional effects are strong, significant and in the expected direction. Most importantly, there is a significant negative effect for dissatisfaction, meaning that respondents who are dissatisfied with the government are also generally more sceptical and have less sympathy for parties on average. There are small negative unconditional effects of being in the incumbent government and a non‐significant effect of being a support party. Furthermore, respondents tend to like parties that are ideologically proximate and parties that are ideologically further away from the government. Most of the remaining variance at higher levels is located at the level of voters and parties, reflecting that some voters are more positive than others and some parties are more popular than others. About 20 per cent of the variance in party sympathy is located at a higher level.

Table 1. Linear multilevel model

Note: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Next, I include a cross‐level interaction between dissatisfaction (at the respondent level) and role vis‐a‐vis the government (at the party‐election level). This interaction effect directly tests Hypothesis 1. For voters who are satisfied with government performance, there is a large positive effect of being the party of the prime minister but also positive effects of being a junior member of the coalition or a support party. However, for voters who are dissatisfied the effect completely reverses. For dissatisfied voters, there is a significant negative effect of leading, participating in or supporting a minority government.

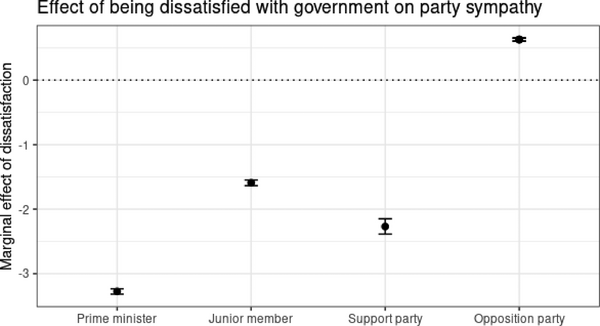

Figure 1 illustrates the marginal effect of being dissatisfied on the party sympathy. For the prime minister's party, there is a negative effect corresponding to a 3.3 unit decrease in party sympathy measured on a scale from 0 to 10. This is a very large effect, suggesting that performance is crucial for the electoral success of the prime minister. For junior members, this effect is −1.6, which is still strong and significant. Surprisingly, the effect of being dissatisfied with support parties is even stronger. At −2.3, the effect is significantly lower than that for junior members, which clearly shows that in terms of party sympathy, serving as an external support party is costly. For opposition parties, there is a very small positive effect.

Figure 1. Marginal effect of dissatisfaction on party sympathy by party role.

Retrospective voting

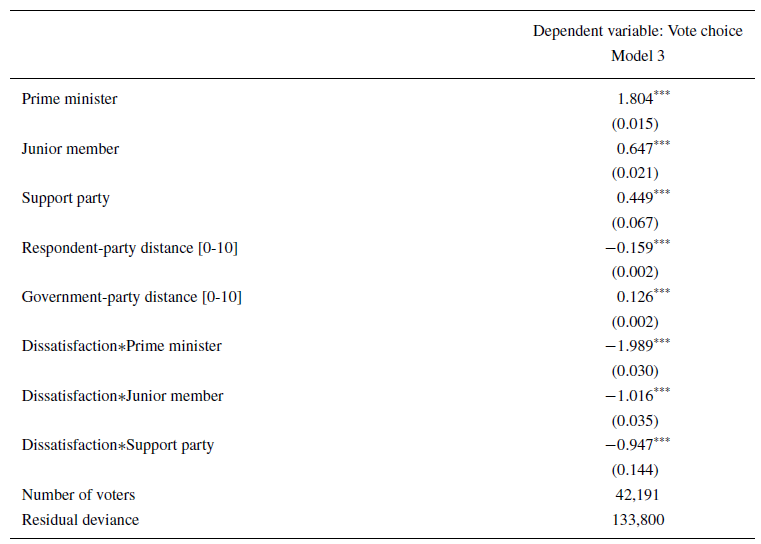

Model 3 uses vote choice as the dependent variable in a conditional logit model (see Table 2). Since dissatisfaction is an ‘individual‐specific variable’, it is not possible to estimate an unconditional effect. Instead, Model 3 includes interactions between dissatisfaction and the role of the parties. Voters who are satisfied with the government's performance are much more likely to vote for the prime minister's party but also for the junior members and the support parties. Keep in mind that this is after controlling for the voters' own ideological proximity to the parties. For dissatisfied voters, the relationship is the opposite. For all parties associated with the government, there is a net‐negative effect of dissatisfaction: meaning that dissatisfied voters are less likely to vote for any of the involved parties than satisfied voters. Interestingly, the marginal effect of dissatisfaction is strong and significant for the support parties. This clearly supports Hypothesis 2 and indicates that support parties are indeed punished for the performance of the government.

Table 2. Conditional logit model

Note: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

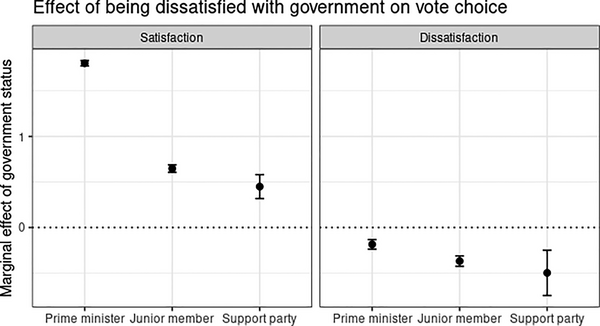

The marginal effects from Model 4 are illustrated in Figure 2. Again, I find that satisfied voters are much more likely to vote for the prime minister's party compared to an opposition party. There are also positive effects of being a junior member or a support party, although they are not as strong. Dissatisfied voters, on the other hand, are less likely to vote for the prime minister's party and much less likely to vote for a junior member or a support party. Interestingly, the likelihood of voting for a junior member or a support party compared to the prime minister's party is significantly lower among both satisfied and dissatisfied voters, which confirms the electorally advantageous position of the prime minister in the coalition (Hjermitslev, Reference Hjermitslev2020).

Figure 2. Marginal effect of government status on vote choice by dissatisfaction.

Overall, the results suggest that support parties can collect both credit and blame for government performance and, thus, that they are in no way exempt from retrospective voting. In line with the findings of Tuttnauer and Wegmann (Reference Tuttnauer and Wegmann2022), I find that when dissatisfied voters have to decide among opposition parties, they prefer opposition parties that confront the government rather than support parties that cooperate.

Robustness checks

Ideological distance

One might question whether the support parties are being punished for their direct affiliation with the government, or whether they are simply punished because they are proposing policies similar to the failed policies of the government. Williams and Whitten (Reference Williams and Whitten2015) showed that when clarity of responsibility for government policy is low, parties that are ideologically proximate to the government are also affected by retrospective voting. They described this as a spatial contagion effect in which voters become unsatisfied with the entire ideological direction the government represents. Thus, it is possible that voters are reacting to ideological proximity rather than shared policy making. To separate the two mechanisms, it is necessary to take ideological positions into account.

In a separate set of regressions, I include the interaction between dissatisfaction and perceived ideological distance between the party and the government. This interaction effect is positive and significant, meaning that for voters who are satisfied with the government performance, ideological distance has a negligible effect, but for voters who are dissatisfied, the ideological distance to the government has a strong impact. This provides strong support for Williams and Whitten (Reference Williams and Whitten2015)'s theory. Dissatisfied voters are indeed more positive towards and likely to vote for parties that are ideologically far from the government.

However, the main results concerning the conditioning effects of dissatisfaction on party roles are surprisingly robust to the inclusion of this additional interaction. The affective and electoral response to support parties is not just a feature of their ideological proximity. The results can be found in the online Appendix.

Political sophistication

Additionally, one might question whether the average voter is even aware of the support parties. Tromborg et al. (Reference Tromborg, Stevenson and Fortunato2019) found that approximately a third were not able to categorize the support parties as such when given the option. This points to considerable heterogeneity in what voters know about the policy influence of parties and the consequential large heterogeneity in their abilities to hold parties accountable. While the CSES does contain some of the classic measures of political sophistication, such as factual knowledge or self‐reported political interest, neither of these survey items was repeated in all waves. Instead, I rely on another proxy for political sophistication, namely education levels.

The results clearly show that there are no large differences across political sophistication. Each education level has marginal effects that are remarkably similar to Figure 1 and Model 2. For all subsamples, there is a significant affective penalty for supporting a minority government that the voter is not satisfied with.

The results for vote choice are not as robust. For dissatisfied voters who have only completed primary or secondary education, there is a significant negative effect of being a support party relative to an opposition party. For dissatisfied voters with post‐secondary or university educations, this effect is insignificant. This suggests that more sophisticated voters are better able to recognize the ambiguous role of support parties.

Single‐party versus coalition governments

The analysis above does not distinguish between coalition and single‐party governments. Having a minority coalition government adds a layer of complexity, thus further impairing the clarity of responsibility (Powell & Whitten, Reference Powell and Whitten1993) because it requires the voter to distinguish between parties within the opposition and the government simultaneously. To explore potential heterogeneous effects, I include a single‐party government indicator in a three‐way interaction in the online Appendix. The results show that dissatisfaction has a much stronger impact on sympathy for the prime minister's party in a single‐party government, while it has a stronger impact on sympathy for the support party of a coalition government. The effects on vote choice are similar. The significant differences between single‐party and coalition governments suggest that responsibility is indeed less clear in the latter case and that this will diffuse penalties away from the prime minister's party.

Conclusion

In this paper, I test whether voters who are satisfied with government performance feel more positively towards and are more likely to vote for external support parties. Using a multilevel linear model and a conditional logit model, I regress party sympathy and vote choice on the interaction between dissatisfaction with government performance and the role of parties vis‐a‐vis the government. My results show that the affective response to dissatisfaction with the government is more negative for support parties than for the junior member, while the effect of dissatisfaction on vote choice is indistinguishable. Thus, the analysis clearly suggests that voters tend to penalize support parties for poor government performance.

Opposition parties often have a substantial influence on policy, and this blurs government responsibility. As a consequence, some members of the opposition cannot fulfil their crucial tasks of scrutinizing and criticizing the government nor represent a credible alternative. According to Andeweg (Reference Andeweg, Müller and Narud2013), it is a challenge to democracy that the distinction between opposition and government is unclear. If voters cannot distinguish between government and opposition, they will no longer feel that they are offered a meaningful choice within their political system. To some extent, the democratic implications depend on voters' ability to recognize and reward or punish support party involvement in government policies.

The results of this paper indicate that voters are quite capable in this regard. Perceived government performance has a systematic effect on how voters feel about support parties. This supports previous findings showing that voters view support parties as tied to the government – and even sometimes part of government (Hjermitslev, Reference Hjermitslev2022; Tromborg et al., Reference Tromborg, Stevenson and Fortunato2019).

In contrast to Thesen (Reference Thesen2016), I find that this affective response translates directly into voting behaviour. If one compares the support parties to junior members, one would find that they do not buy their policy influence at a discount. Since support parties do not ‘fly under the radar’ and thus do not avoid blame for government performance, the established explanations of minority governments, as posited by Strøm (Reference Strøm1990), might need to be revised.

Future research should explore why some parties continue to act as support parties despite being held accountable. First, external support might allow parties to maintain an independent ideological profile, which is necessary to keep backbenchers and activists happy. Second, the study only includes support parties with a ‘comprehensive’ commitment to the government but parties who successfully manage the narrative might be more or less vocal about their support depending on how closely their policy goals align with the government's agenda. Finally, some support parties, especially in systems with strong blocs, cannot credibly threaten to overturn the government and might be making the most of their locked position by formalizing support.

The arguments outlined here have important implications for political systems with consensual traits where the responsibility for policy is less concentrated in the government. Instead, some of the parties in the opposition have a substantial influence on policy and accounts of retrospective voting should reflect this wider notion of responsibility (Plescia & Kritzinger, Reference Plescia and Kritzinger2017). Hopefully, future studies will move beyond a dichotomous distinction between opposition and government and incorporate the full range of parliamentary roles parties can take on.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Maria Thürk for generously sharing her data on minority governments and support parties, Wanda Melina Perner for assisting with data merging, and Maximilian Martin for proofreading. The author also thanks James Adams, Mads Elkjær, Bart Meuleman, Jonathan Polk, and Marco Steenbergen for providing valuable feedback on earlier versions of the article. Finally, the author is grateful for the comments and suggestions of three anonymous reviewers, which have helped in improving the manuscript greatly.

Data availability statement

The dataset is created by merging survey data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (available for free download via https://cses.org/) with data on the composition and status of governments. The government data and all replication files are available on the website of EJPR and the author's personal website.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Dataset.

Online Appendix.