Introduction

In 1933, the National Geographic Society published Robert Shippee’s aerial photographs of the ‘Band of Holes’ (Figure 1), a band of thousands of aligned depressions that tracks for more than 1km in the foothills of the Andes and continues to intrigue researchers today. The site, here referred to as Monte Sierpe (‘Serpent Mountain’), is located on the north side of the Pisco Valley in the coastal desert zone of southern Peru, 35km from the Pacific coastline, and includes a 26ha defensive settlement situated 1km east of the depressions. Monte Sierpe is positioned at the intersection of a network of pre-Hispanic roads (GEOCAM 2024) and lies between two Inca administrative centres: Tambo Colorado and Lima La Vieja (Román et al. Reference Román, Tantaleán, Tavera and Stanish2024) (Figure 2). The Chincha Kingdom, a wealthy and centralised polity, controlled the Pisco and neighbouring Chincha valleys during the Late Intermediate Period (AD 1000–1400), before the area fell to the Inca and Spanish empires in the Late Horizon (AD 1400–1532) and the Colonial period (AD 1532–1825), respectively. In the Colonial period, the site became part of the Humay district, incorporating a hacienda that cultivated grapes, and in the eighteenth century, the “famous wine hacienda called Monte Sierpe, in the valley of Humay” was owned by Capitán D. Juan de Robles y Pérez (del Busto Duthurburu Reference del Busto Duthurburu1969: 744), providing historical continuity of the name ‘Monte Sierpe’.

Figure 1. An aerial photograph of Monte Sierpe taken by Robert Shippee and published by the National Geographic Society in 1933 (photograph reproduced courtesy of the American Natural History Museum; AMNH Library negative no. 334709).

Figure 2. The Pisco Valley in southern Peru (figure by J.L. Bongers).

Monte Sierpe is a unique architectural form in the pre-Hispanic Andes (Figure 3): a 1.5km-long, artificial earthen band that follows a ridge from the valley bottom up the side of a hill. The width of the band varies between 14 and 22m, with an average width of around 19m. The band is not continuous but rather segmented into sections or blocks, each containing a series of holes that are 1–2m in diameter and 0.5–1m in depth. The natural surface of the hill is composed of colluvial and likely some aeolian sediments (ONERN 1971). The holes are excavated out of the natural and mounded sediments, and some are lined with partial stone walls.

Figure 3. Monte Sierpe: a–c) aerial photographs of the Band of Holes and its surrounding environment; d) ground-level photograph of the holes (photographs a–c by J.L. Bongers; photograph d by C. Stanish).

Hypotheses regarding the site’s purpose include defence (Vennersdorf Reference Vennersdorf, Eriksen and Rindel2018), storage (Hyslop Reference Hyslop1984: 289), water collection, fog capture, geoglyph construction, gardening, burial and mining. Following a site survey, Charles Stanish and Henry Tantaleán (Reference Stanish and Tantaleán2015) proposed that the holes functioned as accounting and temporary storage devices dating from the Late Intermediate Period and/or Late Horizon. An article on their work published in Archaeology Magazine (Powell Reference Powell2016) widened public awareness of the site, contributing to its prominence among the pseudo-archaeological community as an ‘unexplained mystery’. Monte Sierpe has subsequently appeared in the popular media, particularly in connection with ‘ancient astronaut’ ideology. Though largely disparate from mainstream archaeology and unable to withstand scientific scrutiny, it is essential to challenge such narratives with clear archaeological evidence and reasoning to ensure that local heritage and Indigenous knowledge are accurately represented in academic and public discourse.

Our research builds on previous studies of Monte Sierpe (Wallace Reference Wallace1971; Hyslop Reference Hyslop1984; Engel Reference Engel2010; Stanish & Tantaleán Reference Stanish and Tantaleán2015), integrating high-resolution aerial imagery that documents the numerical patterning of holes in certain sections with the microbotanical analysis of 21 sediment samples to present new insights into the site’s organisation and use. The arrangement of the approximately 5200 holes is structurally reminiscent of at least one locally found khipu, an Inca knotted-string device used for detailed record-keeping (Barraza et al. Reference Barraza, Areche and Marcone2022). Drawing on these archaeological data and information from colonial-era written sources, we propose that Monte Sierpe originally functioned as a barter marketplace and was later used as an accounting device for tribute collection. Our research thus contributes an important Andean case study on how past communities modified landscapes to bring people together and promote interaction, enriching our understanding of Indigenous forms of accounting and exchange, and of their relationship with the built environment, and stimulating wider discussion of these important topics.

The Chincha Kingdom

With territory spanning the Chincha and Pisco valleys, the Chincha Kingdom was one of the most powerful polities on the Peruvian southern coast during the Late Intermediate Period. Colonial-era records yield critical insights into the region. For example, Pedro Cieza de León (Reference Cieza de León and de Onis1959: 344–45) notes that these lands were highly productive and capable of supporting large-scale agriculture. At least 30 000 male tribute payers existed in the area (Rostworowski Reference Rostworowski1970), suggesting an estimated total population of over 100 000 people. Alongside annual renewal of rich alluvium by seasonal rivers, agricultural productivity was likely enhanced by seabird guano (excrement), an effective fertiliser exploited in later periods on islands off the western coast of South America, including the Chincha Islands offshore from the Pisco and Chincha valleys (Curatola Reference Curatola, Varón Gabai and Flores Espinoza1997). Reports of high population estimates (Rostworowski Reference Rostworowski1970) are further supported by the identification of dense Late Intermediate Period and Late Horizon settlement, including defensive sites, administrative complexes, cemeteries (Bongers et al. Reference Bongers, Muros, O’Shea, Gómez Mejía, Cooke, Young and Barnard2023), irrigation canals and cultivation fields, across both coastal valleys. Shippee’s (Reference Shippee1933) aerial photographs of the wider Pisco Valley show an elaborate irrigation system (Figure 4) and archaeological evidence indicates that both population size and agricultural productivity increased during late pre-Hispanic periods.

Figure 4. Aerial photograph of a complex irrigation system in the Pisco Valley c. 1933, located 4km west and below Monte Sierpe (photograph reproduced courtesy of the American Natural History Museum; AMNH Library negative no. 334717).

The Chincha Kingdom was reportedly composed of economic specialists, with at least 10 000 fisherfolk, 10 000 farmers and 6000 artisans and merchants living in distinct parts of the Chincha Valley (Rostworowski Reference Rostworowski1970). Alongside permanent fisherfolk and farming communities, Chincha merchants substantially expanded interregional trade networks and became a valuable source of wealth for the kingdom. Acquiring silver, gold, emeralds and other prestigious items, which they exchanged with lords from the nearby Ica Valley, these merchants also reportedly sailed along the coast in balsa rafts and managed llama caravans for inland trade with highland regions (Rostworowski Reference Rostworowski1970). Local and nonlocal craft specialists included metalworkers, carpenters, herders, potters, tailors and miners; integration of such producer-specialists into a larger political entity—a señorío or kingdom—characterises the economic organisation of the Chincha and other Late Intermediate Period coastal polities.

The Inca brought the Chincha Kingdom under their rule in the fifteenth century, effecting substantial economic restructuring. Yet, Chincha leaders received wide latitude as subjects of the Inca state, retaining a degree of autonomy and status. During the Cajamarca massacre in AD 1532, the Chincha lord was the only other individual carried on a litter alongside the Inca emperor (Pizarro Reference Pizarro and Means1921). The Chincha may have voluntarily assumed seafaring client status to acquire privileged access to the trade in Spondylus princeps (Sandweiss & Reid Reference Sandweiss and Reid2016), while the Inca seized agricultural land and intensified fishing production in Chincha (Sandweiss Reference Sandweiss1992), reorganised the populace into a decimal-based administration and conducted periodic censuses to levy tribute (Crespo Reference Crespo1975).

Methods

Our study aimed to document the layout of Monte Sierpe in more detail than has previously been attempted and to test Hyslop’s (Reference Hyslop1984: 289) hypothesis that the site was used for storing goods. Mapping was conducted using a DJI Mavic 3E drone and the high-accuracy (20–40mm) Trimble Catalyst global navigation satellite system. Sediment was opportunistically sampled from 19 holes, one of which was directly dated (1905-01), with two control samples (C7 and C10) collected from 5–8m outside the band (21 samples total). These samples were collected from across the site and at different elevations, following the removal of the first 50mm of sediment from sampled holes. All sediment samples were analysed for the presence of pollen, phytoliths and starch grains at the Archaeobotanical and Paleoecological Laboratory of the University of South Florida’s Institute for the Advanced Study of Culture and Environment and at the Laboratorio de Palinología y Paleobotánica at the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia in Peru. One radiocarbon date was obtained from the Keck-CCAMS Facility at the University of California Irvine (UCIAMS). See online supplementary materials (OSM) for full details.

Results

Site survey

Recovery of Late Intermediate Period- and Late Horizon-style pottery fragments (Figure 5) from the surface indicates that Monte Sierpe was constructed during the Late Intermediate Period and used through the Late Horizon. Charcoal collected from inside hole 1905-01 (Figure S1) returned a radiocarbon date of 635±15 BP (UCIAMS 223236: AD 1320–1405 at 95.4% probability; modelled in OxCal v.4.4 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009), using the ShCal20 Southern Hemisphere calibration curve (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg2020)). This date is consistent with the wider chronological context of nearby defensive settlements, which are all Late Intermediate Period and Late Horizon in date (Stanish & Tantaleán Reference Stanish and Tantaleán2015: 72).

Figure 5. Late pre-Hispanic ceramics from Monte Sierpe: a, c, d) Late Intermediate Period Chincha-style ceramics from the defensive settlement; b) Late Intermediate Period-style sherd from the Band of Holes; e) Inca-style ceramic from the defensive settlement (photograph a by J. Larios; photograph b by C. Stanish; photographs c–e by J.L. Bongers; figure by J. Osborn).

Detailed drone imagery indicates that Monte Sierpe has approximately 5200 holes, consistent with earlier estimates (Stanish & Tantaleán Reference Stanish and Tantaleán2015). As previously observed (Wallace Reference Wallace1971), the holes cluster into multiple sections separated by empty spaces and differentiated by hole counts and construction styles, such as holes with and without stone walls. Although such distinctions are often clear, defining these sections can be subjective; we identify at least 60 sections from the images.

Distinctive patterns in hole count across various sections demonstrate an underlying intention in structural organisation. For example, section a in Figure 6 has at least nine consecutive rows with eight holes each, while section b has six consecutive rows with seven holes and one row with eight holes, totalling 50 holes. Repetitions in pairs of hole counts are also seen, such as in section c, which has at least 12 rows that alternate between counts of seven and eight.

Figure 6. A digital elevation model overlaid on an orthomosaic of Monte Sierpe reveals layout patterns within sections a, b and c. Black numbers indicate counts of holes from east to west, while the black arrow in section b marks a space between two sections of holes (figure by J.L. Bongers).

Microbotanical remains

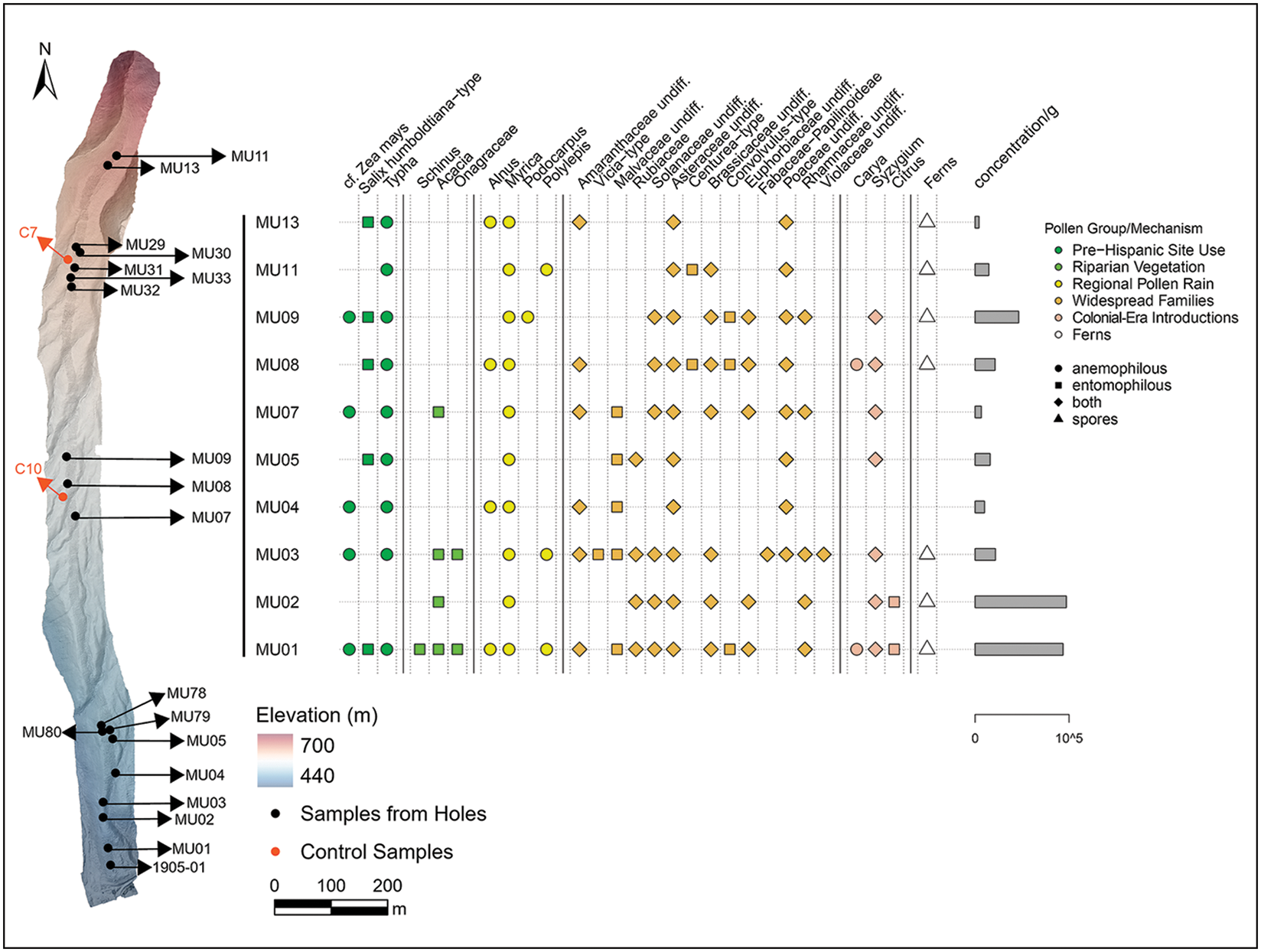

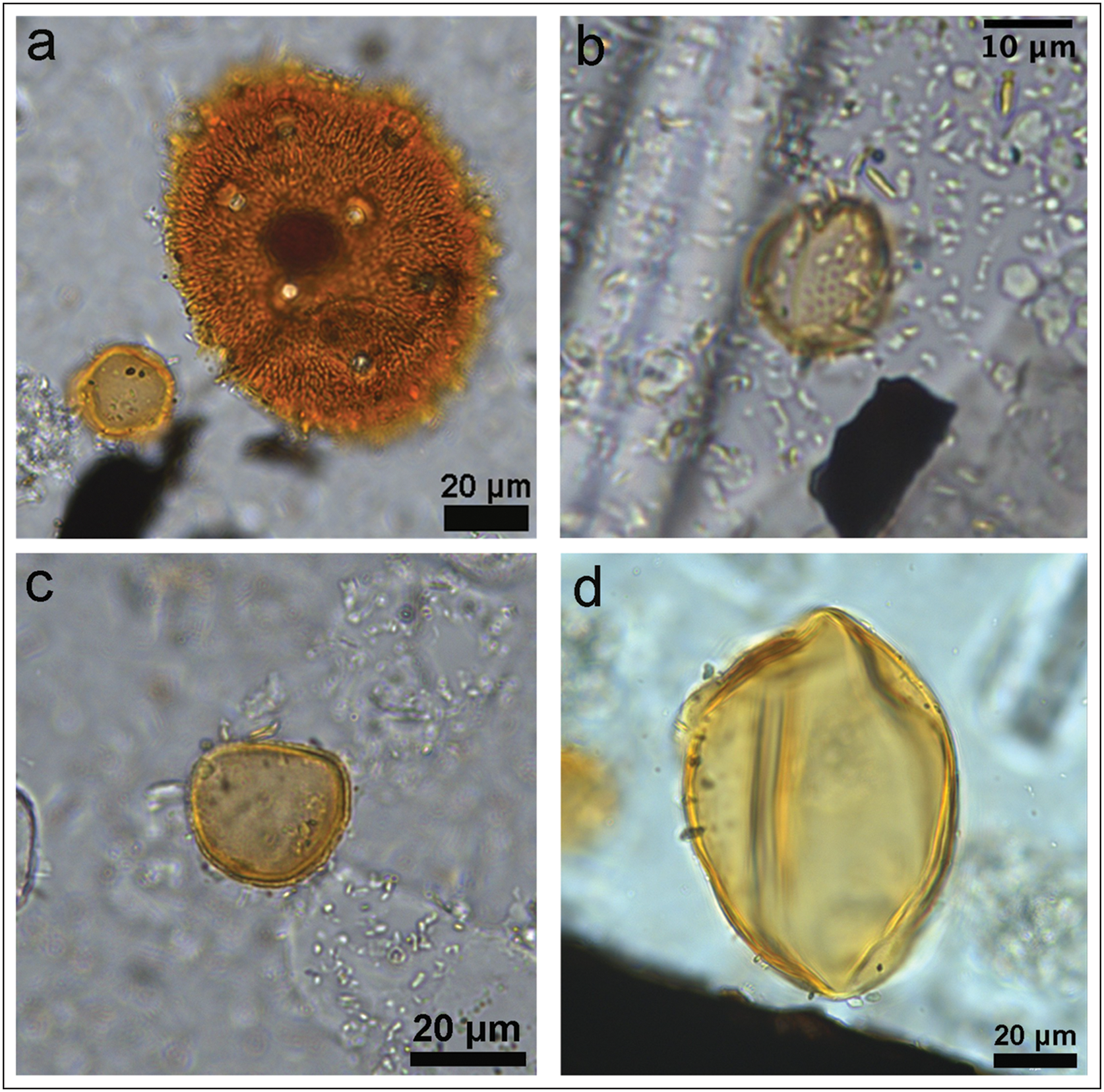

Sediment samples from the holes contain subfossil pollen, phytoliths, diatoms, sponge spicules, spores and starch grains (Figure 7). At least 27 pollen types (see photographs in Figure 8 and OSM) are identified, representing conifers, monocots and dicots. Some pollen types are found across the entire sampled elevation gradient. These include Euphorbiaceae, cf. Zea mays (maize), Rhamnaceae, Salix, Amaranthaceae, Solanaceae, Brassicaceae and Syzygium. Several pollen types were identified in sample 1905-01, analysed in Lima, such as Zea mays, Typha and Poaceae.

Figure 7. Distribution of sediment samples from Monte Sierpe and associated palynological data (figure by J.L. Bongers and C. Kiahtipes).

Figure 8. Select pollen from Monte Sierpe: a) Malvaceae from MU01; b) Salix from MU03; c) Typha from MU03; d) Zea mays from MU03 (photographs by C. Kiahtipes).

Identified pollen types reflect the presence of pre-Hispanic food and industrial crops, notably maize, as well as wind-borne pollen produced by more distant vegetation (e.g. species of Podocarpus, Polylepis, Alnus and Myrica), and from plants almost certainly introduced to the region following the sixteenth-century European invasion (e.g. Syzygium sp., Carya and Citrus) (Figure 7). Diatoms in these samples are likely marine in origin (L. Grana, pers. comm.).

Phytoliths in sample 1905-01 include Pooideae, Panicoideae and Zea mays, and starch grains of Cucurbita (MU79, MU30, MU33) (Figure S37) and Amaranthaceae (MU78, MU79, MU31) are identified in other sediment samples. The control samples do not contain phytoliths, but C7 contains starch grains of Cucurbita. Diatoms and sponge spicules are found in C7, C10 and all but two sediment samples from the holes (Figure S38). For detailed results and discussion of the microbotanical analyses, see OSM.

Discussion

Identification of numerical patterning in hole counts and of microbotanical evidence of crops and wild plants in the holes provides little support for hypotheses connecting Monte Sierpe with defence, water collection, fog capture, burial or mining, though our results cannot rule out the possibility that the site functioned as a geoglyph. In comparing Monte Sierpe and other built features around the world, it is critical to recognise that morphological similarities do not necessarily equate to functional equivalence. For example, bands of shallow holes (hulbæltet) were sometimes constructed to defend Iron Age (500 BC–AD 0) settlements in Europe (Vennersdorf Reference Vennersdorf, Eriksen and Rindel2018), but no evidence of related fortification, nor of attacks or defensive responses, is found at Monte Sierpe, and there is a notable lack of the typical weapons—such as slingstones (bolas)—documented at other fortified Andean sites.

Comparisons have also been drawn with other features worldwide, such as the shallow pits used for grape cultivation in Lanzarote, Canary Islands (Stevenson et al. Reference Stevenson, Naranjo-Cigala, Ladefoged and Díaz2023), or for fog or water capture and as sunken fields (Parsons & Psuty Reference Parsons and Psuty1975) elsewhere in the Andes. These hypotheses lack strong support, not least as rainfall is effectively non-existent at these altitudes in the Pisco Valley and as Andean sunken fields typically rely on groundwater (Parsons & Psuty Reference Parsons and Psuty1975), which is not available on Monte Sierpe’s slope. Located in an area of ephemeral (persisting for less than one week) fog oases (lomas) (Moat et al. Reference Moat2021), the holes could have captured fog (see OSM), but the resulting water would not have been sufficient to grow most of the identified plants at Monte Sierpe in situ. In addition, the nearby Pisco River provides sufficient water for agriculture year-round, without the need for fog capture.

As no human remains were found at the site, aside from a few intrusive tombs at the southern end, and no evidence of copper or silver ores has yet been found, it is unlikely that Monte Sierpe was a burial ground or a mining area.

Monte Sierpe as a node

Monte Sierpe is strategically located near the intersection of one of the most important pre-Hispanic coast-highland trade routes (Wallace Reference Wallace1971; Sandweiss & Reid Reference Sandweiss and Reid2016; Beresford-Jones et al. Reference Beresford-Jones2023) and major north-west to south-east roads that connected the Chincha and Pisco valleys and extended to Lima La Vieja and Humay. These roads also provided a route south to the Ica Valley, likely facilitating trade between Chincha merchants and the Ica lords (Rostworowski Reference Rostworowski1970). Monte Sierpe is in the chaupiyunga, a transitional ecological area between the coastal plain and the highland valleys. Since groups living in these zones typically controlled access to the headwaters of downstream irrigation and to important highland mineral sources, the chaupiyunga became a “focal point for many types of interaction and a prime setting where…coastal, local, and highland groups came together to exchange products and negotiate for access to land, water, and minerals” (Szremski Reference Szremski2017: 86). Monte Sierpe could therefore have provided a location for groups to deposit goods. The site’s sections were kept compact to facilitate movement along its sides above the ridge slopes. Empty areas between the sections likely functioned as ‘crosswalks’ to enable east–west movement across the site (sees Figures 3c & 6b), while the spaces between consecutive holes are large enough to permit movement within sections (see Figure 3d).

The results of our microbotanical analysis support the hypothesis that plants were deliberately placed into the holes during pre-Hispanic times, potentially through periodic lining of the holes with plant fibres, or through bundle-making and basketry. Given the arid hillside location of Monte Sierpe, humans are the most probable means of transmission into the site for self-pollinating plants, such as maize, and likely also for plants with heavy, insect-borne (entomophilous) pollens (Figure 7). Maize produces very little pollen rain (Diethart & Heigl Reference Diethart and Heigl2021) but is present in at least six samples, including two from the centre of the site (MU07, MU09). Salix humboldtiana (Humboldt’s willow) is entomophilous but found throughout Monte Sierpe. It is endemic to coastal riparian vegetation and yields thin, flexible boughs ideal for making baskets and other items for crop transport and storage. Convolvulaceae, Malvaceae and Solanaceae pollens are also predominantly insect-borne and include economic species such as cotton, tomatoes, chilli peppers and sweet potato. Although colonial use of Monte Sierpe cannot be ruled out, there is no documentary evidence for any subsequent use of the site; the presence of these pollens in the holes is therefore most parsimoniously explained by pre-Hispanic activities. The single exception to this reasoning is the identification of the heavy, insect-borne Citrus pollen, a colonial-era introduction, though this pollen is only present in two holes, both at the southern, lower altitude end of the band (Figure 7).

Wind-borne (anemophilous) pollen might have entered the holes naturally or through human activity. For example, the presence of Typha (bulrush) pollen may evidence periodic lining of the holes or the movement of bundled goods to and from them. Although Typha pollen typically travels only 50–100 metres (Ahee et al. Reference Ahee, Van Drunen and Dorken2015), it is almost ubiquitous in the sediment samples from Monte Sierpe (Figure 7). Baskets and mats have been woven from the stems and leaves of bulrushes and reeds (Cyperaceae) for millennia in the Andes (Paredes Reference Paredes2018), including in Chincha (Bongers Reference Bongers2019: 190). Goods may therefore have been transported to Monte Sierpe in baskets and matting, and the movement of plants with soil and sediment still adhering to their roots provides another vector for the transmission of other pollen types. Wind-borne pollens from high-altitude vegetation may have been, and likely still are, blown into the holes over great distances, including Podocarpus, Polylepis, Alnus and Myrica (Weng et al. Reference Weng, Bush and Silman2004). Pollens from colonial-era introductions at Monte Sierpe are also typically wind borne, such as Syzygium and Carya, with the agricultural fields on the valley floor the nearest likely source.

The microfossil assemblage from Monte Sierpe derives from the erosion of the local sedimentary bedrock, anthropogenically modified landscape processes and aeolian movement. Breakdown of local sedimentary rock of Miocene/Pliocene marine origin (ONERN 1971) is likely the primary source of diatoms and sponge spicules, which are present in both the archaeological and control samples.

The function of Monte Sierpe

Barter marketplace

Both the strategic location of Monte Sierpe and the microbotanical assemblage from the holes are consistent with the site serving as a place for exchange under the Chincha Kingdom. Barter markets are found throughout the premodern and non-Western world. These are places where goods are directly exchanged without the use of currency (Stanish Reference Stanish2017: 135). Historical records attest that fairs and markets for exchanging a variety of goods were held in the Andes with great frequency (Langer Reference Langer2004): “Throughout the entire kingdom of Peru…there were large tiangues that are markets where the locals conducted their business” (Cieza de León Reference Cieza de León1984: 376). These markets ranged from extravagant annual celebrations to more humble weekly fairs throughout the countryside and were more than just places to exchange goods. They involved highly ritualised behaviours and encompassed the full range of social activities embedded in the lives of the community. While there is no currency, all barter markets operate with units of equivalency and account. Contrary to the belief that there were few, if any, marketplaces in the pre-Hispanic Andes (Murra Reference Murra1980), social science research has demonstrated that marketplaces existed throughout the region (Hirth & Pillsbury Reference Hirth and Pillsbury2013; Ragkou & Mader Reference Ragkou and Mader2025). A Quechua lexicon compiled by the Dominican friar Domingo de Santo Tomás in 1560 includes words for barter (randini) and marketplace (catu), as well as for vendors or merchants (catu camayoc) (Covey & Dalton Reference Covey and Dalton2025). As founder of the Chincha Dominican monastery c. 1540 (Menzel & Rowe Reference Menzel and Rowe1966), Domingo de Santo Tomás likely had knowledge of economic systems in the Chincha and Pisco valleys.

Identifying barter marketplaces in the archaeological record remains notoriously difficult (Stark & Garraty Reference Stark, Garraty, Garraty and Stark2010). Increasing surplus, population density and economic specialisation set critical foundations for the emergence of marketplaces (Demps & Winterhalder Reference Demps and Winterhalder2019; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Conte, Oh and Park2024), which are often positioned along long-distance trade routes, at the intersection of ecozones and distinct cultural groups, and near associated residential sites (Hirth Reference Hirth1998). These criteria are recognisable in the location of Monte Sierpe, in the chaupiyunga of Pisco and near the contemporaneous defensive settlement. For Chincha society—characterised in the Late Intermediate Period by a burgeoning population, a variety of economic specialists and guano-driven agricultural surplus—a barter marketplace could have provided vital social integration, provisioning distinct communities over a broad area (Sandweiss & Reid Reference Sandweiss and Reid2016: 9). At present, there is no evidence for nonlocal goods at Monte Sierpe, which would suggest that if the site did function as a marketplace, exchanges were limited to locally grown goods, such as maize and cotton, through interactions among neighbouring communities within Chincha and in adjacent regions such as Ica (Rostworowski Reference Rostworowski1970). Balances, which are documented throughout the Chincha Valley, potentially played a role in this barter system (Dalton Reference Dalton2024).

The visual prominence of Monte Sierpe and its proximity to a major trade route intersection may have increased the probability of locating suitable trading partners, drawing together producer-specialists (e.g. farmers and fisherfolk), mobile traders (e.g. llama caravans and seafaring merchants), lords and administrators for periodic exchange. Large numbers of people depositing goods in the holes would give participants information about the quantity of goods available in an ordered way (Blanton & Feinman Reference Blanton and Feinman2024: 7). To help ensure fairness, exchanges would be ritualised, public and structured around customarily fixed equivalences rather than currency (Stanish & Coben Reference Stanish, Coben, Hirth and Pillsbury2013). In such a scenario, the numerous holes would have allowed for a standardised system of equivalencies typical of barter markets.

Accounting device

Following the incorporation of the Chincha Kingdom into the Inca state, Monte Sierpe may have been folded into the Inca system of exchange and tribute extraction, with the site functioning as an accounting device. The nature of tribute and accounting in the Inca state has been extensively investigated (Julien Reference Julien1988). The Inca imposed a labour-tax system known as mit’a, where communities were reorganised into a hierarchical decimal system and expected to take ‘turns’ paying a labour tax or its equivalent in tribute. For example, administrative units of one thousand individuals in Chincha and its neighbouring valleys (e.g. Pisco) provided tribute both in the form of labour and produce. Farmers managed fields of varying sizes, with portions of total yields put in storehouses for later transport to Cusco, Jauja and Pachacamac (Crespo Reference Crespo1975: 101). Knotted-string khipus were used to keep track of census information, tribute and inventory (Barraza et al. Reference Barraza, Areche and Marcone2022).

A discovery in the Cañete Valley at the major Inca administrative centre of Inkawasi provides a potential clue for interpreting Monte Sierpe. Like Tambo Colorado in the Pisco Valley, Inkawasi is a huge administrative site that may once have been part of the Chincha Kingdom (Castillo et al. Reference Castillo, Marcone, Irazabal, Areche, Huerta and Burga2023). A grid-like array of squares found on the floors of two rectangular sorting spaces in the site’s storage complex could represent standardised accounting units for agricultural produce (Urton & Chu Reference Urton and Chu2015: 512). Khipus were also found in the complex, sometimes in physical association with such produce. The regularity of these squares is comparable to the numerical patterns at Monte Sierpe, suggesting a potentially similar purpose: the counting and sorting of different goods. The segmented and regular arrangement of the holes at Monte Sierpe also finds an analogue in a complex Inca-style khipu excavated near Pisco around the turn of the twentieth century (VA16135a/VA16135b in the Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin) (Figure 9). The pendant cords of this khipu are arranged in 80 distinct groups of similar size, with almost all groups consisting of either 10, (most frequently) 11 or 12 cords. The numbers knotted on the cords exhibit an intricate set of arithmetic interrelationships (Medrano & Khosla Reference Medrano and Khosla2024), suggesting that it is a surviving record of the kinds of ‘working’ accounting operations that would have characterised functional activity at Monte Sierpe.

Figure 9. Khipu found near Pisco now held in the Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin: top) VA 16135a; bottom) VA 16135b (© Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, photographs by Claudia Obrocki; made available via CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence; figure by J. Osborn).

As an accounting device, each section at Monte Sierpe could have been linked to a particular social group for the payment of tax and the redistribution of commodities. Numerical patterns in layout and variation in the number of holes across sections may correspond to other local khipus and to sixteenth-century tribute lists in the Andes, reflecting differences in tribute levels and/or the number of taxpayers from specific villages and towns. Kin-based units would have been responsible for building and maintaining the holes and depositing goods, such as maize, into the hole sections through the traditional Inca mit’a system (Julien Reference Julien1988). Each segment might correspond to a social group, whether it was kin-based or location-based. This interpretation coincides with Monte Sierpe’s ideal location for commodity accounting, collection and control between Tambo Colorado and Lima La Vieja.

Conclusion

Our research contributes new data about the organisation and function of Monte Sierpe. Strategically situated at a critical crossroads between the Chincha and Ica valleys, coastal and highland ecological zones, and Inca administrative sites (Tambo Colorado and Lima La Vieja), Monte Sierpe was a place where disparate communities and goods could come together. The site’s accessibility is evident in its design, with gaps between sections, traversable hole edges and a compact layout that maximises space along the sides. Microbotanical remains indicate that the holes were potentially periodically lined with plant materials and goods were deposited inside them, using woven baskets and/or bundles for transport. Numerical patterning in the layout of the holes and the potential parallels found in a local khipu hint at an underlying intention in the site’s organisation. These data support a model in which Monte Sierpe was a localised, Indigenous system of accounting and exchange that dates to at least the Late Intermediate Period. We propose that the site functioned initially as a barter marketplace under the Chincha Kingdom and ultimately became a place to receive and distribute tribute and other goods within the Inca state. This study contributes valuable data to broader debates on Indigenous numeracy, mathematical practices and resource management strategies and how groups structured built environments and interactions. It also raises critical questions about the relationship between Monte Sierpe and khipus, with important implications for enhancing understandings of the origins and diversity of Indigenous accounting practices within and beyond the pre-Hispanic Andes. Our results lay the foundations for future research on Monte Sierpe, including test excavations, additional radiocarbon dating and sediment analyses, and the study of more local khipus. This ongoing and planned work is crucial, not only for further evaluating our model, but also for expanding archaeological datasets to confront the pseudo-archaeological narratives that continue to surround local heritage.

Author contributions: CRediT Taxonomy

Jacob Bongers: Conceptualization-Supporting, Funding acquisition-Supporting, Investigation-Supporting, Methodology-Supporting, Visualization-Supporting, Writing - original draft-Lead, Writing - review & editing-Lead. Christopher A. Kiahtipes: Data curation-Supporting, Formal analysis-Supporting, Investigation-Supporting, Methodology-Supporting, Visualization-Supporting, Writing - original draft-Supporting, Writing - review & editing-Supporting. David Beresford-Jones: Supervision-Supporting, Writing - original draft-Supporting, Writing - review & editing-Supporting. Jo Osborn: Writing - original draft-Supporting, Writing - review & editing-Supporting, Visualization-Supporting. Manuel Medrano: Writing - original draft-Supporting, Writing - review & editing-Supporting. Ioana Dumitru: Visualization-Supporting, Writing - original draft-Supporting, Writing - review & editing-Supporting. Christine Bergmann: Formal analysis-Supporting, Investigation-Supporting, Writing - review & editing-Supporting. José Román: Investigation-Supporting. Carito Tavera Medina: Formal Analysis-Supporting, Writing - original draft-Supporting, Writing - review & editing-Supporting. Henry Tantaleán: Writing - original draft-Supporting, Writing - review & editing-Supporting. Luis Huamán Mesía: Formal analysis-Supporting, Methodology-Supporting. Charles Stanish: Conceptualization-Lead, Investigation-Supporting, Methodology-Supporting, Project administration-Supporting, Supervision-Lead, Writing - original draft-Supporting, Writing - review & editing-Supporting.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Peruvian Ministry of Culture for granting us a permit (000318-2024-DCIA-DGPA-VMPCIC/MC) that allowed us to carry out this study. We are grateful to Jorge Rodríguez for assisting with mapping Monte Sierpe and to Lorena Grana for examining photographs of diatoms.

Funding statement

This research was funded by a Franklin Research Grant, the University of South Florida office of the Dean and the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Data availability statement

All data are available in the main text or the OSM.

Online supplementary material (OSM)

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10237 and select the supplementary materials tab.