Introduction

Interest group networks are a key feature of European Union (EU) lobbying and policymaking. The formation and structure of these networks are essential for the dynamics of interest representation in a system of governance in which interest groups perform a key role in functional and geographic (national) interest intermediation as well as engage in multi‐venue lobbying as members of multiple policy communities and networks (Beyers Reference Beyers2002). The extent to which organisations remain embedded in national networks or manage to build supranational ones confronts a fundamental question of European integration: to what extent has the EU interest group system been Europeanised and in what way has it adjusted to the complexities of a two‐level game of shared competences and decision‐making (Kohler‐Koch & Friedrich Reference Kohler‐Koch and Friedrich2020)?

Despite the importance of interest group networks, the literature is still short of research similar in scope and focus to landmark studies examining organisational networks in US politics and policymaking (Laumann & Knoke Reference Laumann and Knoke1987) and across different national settings (Knoke et al. Reference Knoke, Pappi, Broadbent and Tsujinaka1996). The handful of studies examining EU networks focus on one policy area (Pappi & Henning Reference Pappi and Henning1999; Chalmers Reference Chalmers2013; Bunea Reference Bunea2015), analyse a limited number of organisations and decision‐makers (Beyers & Kerremans Reference Beyers and Kerremans2004) or focus on one type of organisational actor (Beyers & Donas Reference Beyers and Donas2014). We, therefore, lack a systematic comparison of the networks formed by numerous and diverse organisations across EU policy domains.

In the absence of such a study, key questions about EU interest group networks remain unaddressed. Are networks more likely to be formed based on country of origin or based on the interest type represented? For example, are French business groups more likely to form ties with French NGOs or with German business groups? To what extent does privileged access to decision‐makers matter in network formation? For instance, is BusinessEurope used by other organisations as an important information source because it meets European Commission high‐level officials more often than others? Lastly, how do these relations vary across policy areas? Does country of origin, interest type and policy insiderness matter more or less in the single market policy compared to regional, foreign and security, or migration policies?

We address this gap and propose an investigation of what explains the formation of interest group information networks across EU policy domains. Theoretically, we build on the literature concerning information networks and EU integration and interest groups. We develop an explanation of network tie formation that considers informational and reputation logics that typically structure information networks, as well as key characteristics of the institutional and policymaking context in which these networks are formed. We argue that organisations are more inclined to form ties with actors that are more likely to be reliable sources of information: these are usually actors that share their policy goals (based on shared country of origin or interest type represented) and have a reputation for being well‐informed sources by virtue of enjoying privileged access to decision‐makers (i.e., policy insiders). The extent to which these organisational similarities and policy insiderness are key drivers of tie formation in interest groups’ networks varies across policy domains, depending on key institutional features such as overall level of interest groups’ access to decision‐making and the degree of centralisation of decision‐making in the hands of supranational institutions (Mazey & Richardson Reference Mazey and Richardson2015).

We test our argument on a new and original dataset capturing ties between interest groups on social media. We examine who follows whom on Twitter and explain the formation of ties between 7,388 organisations across 40 EU policy domains with the help of Exponential Random Graph Models (ERGMs). We find that organisational similarities and policy insiderness are important drivers of tie formation, but their importance varies significantly across policy domains. While shared country of origin is the strongest predictor of tie formation across different types of policy domains, shared interest type and policy insiderness are less relevant for tie formation in areas in which decision‐making is primarily supranational, but more relevant in areas with more intergovernmental policymaking and more limited access to decision‐makers. Our findings attest to the importance of institutional features such as decision‐mode and institutional access opportunities for the formation of networks and provide further evidence of an integrated but not yet supranationalised EU interest group system.

Examining organisational networks is crucial for understanding EU integration, policymaking and interest representation. First, these networks contribute to the creation of a European public sphere amongst its members and offer valuable insights into the structuring of the aggregate policy choice space described by organisational preferences, across policy issues. The extent to which interest groups managed to create and maintain supranational networks or continue to communicate mainly with national counterparts provides important insights about the extent to which the process of European integration resulted in an integrated supranational system of interest representation (Beyers & Kerremans Reference Beyers and Kerremans2012). Second, the structuring of networks is highly informative regarding the structuring of policy conflicts and the emergence of cleavage lines that facilitate the emergence of various constellations of lobbying coalitions and policy sides (Heaney & Leifeld Reference Heaney and Leifeld2018). Third, information networks are essential in shaping policy outcomes (Leifeld & Schneider Reference Leifeld and Schneider2012), lobbying resources and policy influence (Heaney & Strickland Reference Heaney, Strickland and Victor2017). They provide essential information about structural conditions reinforcing or alleviating inequalities in interest representation, influence and power structures. Fourth, the contextual empirical analysis of networks across policy domains provides valuable insights into how the variation in institutional conditions (varying levels of integration, distribution of competence, policymaking modes) structures policy networks (Börzel & Heard‐Lauréote Reference Börzel and Heard‐Lauréote2009) across policy domains and facilitates their comparative examination and understanding.

We contribute to the literature on EU integration and interest groups, the emerging and sparse literature on lobbying and social media (van der Graaf et al. Reference Van der Graaf, Otjes and Rasmussen2016; Ibenskas & Bunea Reference Ibenskas and Bunea2021) and the well‐established research on policy and political networks (Leifeld & Schneider Reference Leifeld and Schneider2012; Box‐Steffensmeier et al. Reference Box‐Steffensmeier, Christenson and Craig2019; Brandenberger et al. Reference Brandenberger, Ingold, Fischer, Schläpfer and Leifeld2020). Theoretically, we build a nuanced argument that recognises the importance of the informational and reputational logics underpinning informational networks and contextualises them in light of key institutional features regarding the system of governance in which they form. Empirically, we present one of the first analyses of information ties between EU interest groups on a truly large scale based on a new and original dataset. We systematically examine the effects of actor, network and policy characteristics on the formation of ties, which allows us to capture important EU systemic features and provide one of the very few comparative analyses of policy domains and organisational networks (Grossmann Reference Grossmann2012: 67).

Information, interests and ties in the EU polity

Lobbying and information networks in a complex policy environment

Across polities, interest groups provide decision‐makers with key information about the feasibility of policy options, technical expertise and political intelligence regarding levels of societal opposition/support for different policy choices. Information represents the hard currency shaping groups’ coalition building, access to decision‐making and ability to determine policy outcomes (Weiler et al. Reference Weiler, Eichenberger, Mach and Varone2019). Monitoring the policy environment and gathering information about other organisations and policymakers are essential for lobbying success (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Esterling and Lazer2003: 414). Research shows that ‘what you know depends upon who you know, and how you are positioned’ in networks (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Esterling and Lazer2003: 411). Informational and reputational logics drive actors’ behaviour in information networks (Ingold & Leifeld Reference Ingold and Leifeld2016). Therefore, interest groups pay considerable attention and time gathering, processing and exchanging relevant information.

In the EU, information is crucial for meeting the high and complex informational demands of supranational decision‐makers (Bouwen Reference Bouwen2004) and for navigating the diverse and densely populated system of organisations in search for coalition partners and policy influence. Possessing reliable and high‐quality information is particularly valuable because information overload (rather than information scarcity) is an important challenge for organisations and decision‐makers (Chalmers Reference Chalmers2013: 488). Successful lobbying requires organisations to participate in networks in a rational and purposeful manner, underpinned by cost–benefit considerations and a concern for maximising the quality of information acquired.

We argue that Twitter, as a communication, information and social media platform, provides organisations with a useful and (mostly) cost‐efficient tool to monitor the policy and lobbying environment and gather relevant information for lobbying activities (Obar et al. Reference Obar, Zube and Lampe2012). Twitter allows organisations to learn in a timely fashion about policy initiatives; estimate the salience of policy issues for other actors; identify their policy positions, preferred outcomes and ‘compromise bandwidths’; identify lobbying camps and potential coalition partners; assess levels of public visibility and the network influence (power) of other organisations; and assess other actors’ chances of lobbying success, given the aggregate distribution of preferences amongst decision‐makers and organisations (van der Graaf et al. Reference Van der Graaf, Otjes and Rasmussen2016). The platform offers important incentives to use it as part of lobbying strategies and coalition‐building activities (Lovejoy & Saxton Reference Lovejoy and Saxton2012).

However, Twitter also implies costs related to information processing and public reputation. It requires managing a high‐traffic online platform and increases significantly the challenge of information overload. Given that Twitter activity is public, organisations may incur reputation costs because of the substantive content of their communications or for following some actors and news feeds over others. We argue thus that organisations are both rational and purposeful in their Twitter usage and contact making (Chalmers & Shotton Reference Chalmers and Shotton2016).

Forming ties: The role of shared goals and policy insiderness

Building on the EU lobbying literature, we argue there are two considerations informing interest groups’ decisions about which groups are useful sources of reliable information: organisations are more likely to form ties with organisations with whom they are likely to share policy goals and those that have privileged access to decision‐makers. We discuss each in turn.

As strategic, yet resource‐constrained, actors active in a complex environment, organisations are confronted with an important choice: include in their networks like‐minded organisations supporting similar policy options; make contact with organisations representing different interests and advocating different, even opposing policies; or pursue a mixed strategy of following both. Research suggests the first scenario predominates: interest groups prefer to exchange information and collaborate with ‘birds of the same feathers’ (Chalmers Reference Chalmers2013; Beyers & de Bruycker Reference Beyers and De Bruycker2018). Like‐minded policy friends are more likely to share high‐quality and reliable information, coalition building is more probable and fruitful (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Esterling and Lazer2003), and the benefits of information sharing are higher because this helps a shared cause. This is consistent with a fundamental insight of social network research: actor homophily is a key driver of tie formation across different types of networks, including information networks (Leifeld & Schneider Reference Leifeld and Schneider2012).

In the EU, organisations perform a dual representation function. On the one hand, they represent constituencies of interests defined within the boundaries of national Member States, performing a territorial (national) representation function. On the other hand, they represent societal or economic constituencies within and across countries, performing a functional representation role. This implies that the country of origin and the type of (functional) interest represented are fundamental for organisational identities and participation in supranational policymaking. They are therefore relevant predictors of tie formation. Being embedded in the same national policy communities may be a source of shared interests in supranational governance and may encourage information exchanges and collaboration (Dür & Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2015). The type of interest represented (particularly the distinction between business and non‐business interests) represents a fundamental source of shared policy goals and lobbying coalitions in the EU (Beyers & de Bruycker Reference Beyers and De Bruycker2018).

Furthermore, this literature emphasises the importance of policy insiders (i.e., organisations enjoying privileged access to decision‐makers) in supranational policymaking. Their presence reflects the elitist tendencies of the pluralist EU interest group system (Eising Reference Eising2007) and constitutes an important systemic feature shaping tie formation. Due to their access, policy insiders are in a privileged structural and informational position relative to decision‐makers and other organisations (Leifeld & Schneider Reference Leifeld and Schneider2012; Weiler & Brändli Reference Weiler and Brändli2015). The latter can use insiders as reputable information sources that they would like to be associated with by other actors. This taps into the logic of maximising information quality and enhancing the reputation of being a credible information source because the actor monitors and uses well‐informed sources. Actor's A decision to follow actor B on Twitter depends on whether actor B simultaneously satisfies two conditions: (1) it is a well‐informed, credible source and (2) it is in a structurally meaningful position that bestows reputational benefits to whoever else is using it as an information source (Ingold & Leifeld Reference Ingold and Leifeld2016). We contend thus that privileged access to decision‐makers highly recommends an organisation as an important information source that merits Twitter following.1

Building on this, we derive three baseline hypotheses:

H1: Organisations sharing country of origin in EU policymaking are more likely to establish an information tie on Twitter.

H2: Organisations representing the same functional interests in EU policymaking are more likely to establish an information tie on Twitter.

H3: Organisations are more likely to form a tie with organisations that enjoy privileged access to decision‐makers.

Forming ties across policy areas: The impact of uneven integration and pluralism

The EU lobbying literature highlights important variations in the system of interest representation across policy areas to the extent that ‘it is dangerous to suggest one typology of EU interest intermediation’ (Coen & Richardson Reference Coen and Richardson2009: 346). Theories of integration and supranational policymaking indicate there are important differences across areas in decision‐making modes and policy styles (Wallace & Reh Reference Wallace, Reh, Wallace, Wallace and Pollack2015). This has important consequences for interest representation and participation in policymaking (Berkhout et al. Reference Berkhout, Carroll, Braun, Chalmers, Destrooper, Lowery, Otjes and Rasmussen2015). Therefore, while we expect that organisational similarities and policy insiderness shape tie formation, we also contend that their relevance varies across areas. To formulate our theoretical expectations regarding this variation, we draw on theories of European integration and interest representation.

Theories of integration acknowledge interest groups as important actors in the design and functioning of the EU and inform our expectations about the importance of shared country of origin in tie formation across policy domains.

The neo‐functionalist, supranational governance and multi‐level governance theories suggest that supranational institutions have policymaking autonomy and important decision‐making power. They represent important access points for groups aiming to shape supranational decision‐making (Beyers Reference Beyers2002).2 According to the supranational governance theory, integration occurs first and foremost in areas where ‘non‐state actors engage in transactions and communications across national borders, creating a need for European‐level rules and dispute‐resolution mechanisms through supranational governance' (Stone Sweet & Sandholtz Reference Stone Sweet and Sandholtz1997: 306–308). As such rules and mechanisms emerge, they increase cross‐border transactions and demand for further integration. Single market policies are most susceptible to such integration processes due to the increasing trade and investment within the EU (Stone Sweet & Sandholtz Reference Stone Sweet and Sandholtz1997: 308). Thus, sharing country of origin should be least relevant for tie formation in regulatory policies related to the internal market, because here (primarily economic) groups from different countries share an interest in the further development of the European common market. Conversely, weaker supranational governance in other policy domains reflects greater fragmentation of groups’ preferences across country borders. For example, ‘[t]here is minimal social demand for integration’ in the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) since ‘few societal transactors find its absence costly’ (Stone Sweet & Sandholtz Reference Stone Sweet and Sandholtz1997: 308). Thus, sharing the country of origin is expected to be more relevant in tie formation regarding policies beyond the core single market policies:

H1a: Organisations sharing the country of origin are less likely to establish an information tie in regulatory single market policies relative to other policy areas.

We note that the supranational governance theory argues that transnational alliances leading to integration in regulatory single market policies were formed primarily between business actors (Stone Sweet & Sandholtz Reference Stone Sweet and Sandholtz1997). This suggests that shared interest type might be a stronger predictor of tie formation in these areas. Despite this, it is not clear that shared interest type matters more for tie formation in regulatory single market policies than in less integrated areas since, in the latter, shared interest type may be equally relevant. Take, for example, the case of welfare policies: they are significantly less integrated than the single market ones but witness the mobilisation for lobbying businesses and trade unions, which usually have opposing and strongly held views. This pattern of mobilisation means that in these areas shared interest type is likely to be an equally strong predictor of ties as it is in regulatory single market policies. We therefore consider theories of integration less informative in developing expectations about the effect of shared interest type on tie formation.

Instead, we turn to the literature on pluralist systems of interest representation to gain further insights about the importance of shared country, shared interest type and policy insiderness for tie formation across policies. An important assumption of the classic pluralist model of interest representation is that decision‐making institutions are unbiased and act as a mediator between competing groups. Multiple, diverse organisations can access them. While significant research challenges these pluralist assumptions across political systems (including the EU; cf. Eising Reference Eising2007), we argue that EU policy domains with a higher centralisation of decision‐making (i.e., characterised by greater ‘depth’ of European integration; cf. Börzel Reference Börzel2005) are more likely to meet this pluralist assumption. Broadly speaking, the depth of integration is higher in regulatory and distributive areas. Conversely, the power of supranational institutions in foreign policies (especially those covering core state matters that go beyond economic issues) is significantly more limited. Interior policies, despite the application of the ordinary legislative procedure in most areas post‐Lisbon, have also continued to be ‘laced with intergovernmentalism’ (Uçarer Reference Uçarer, Ripoll‐Servent and Trauner2018: 323) as a result of the sovereign sensibilities of Member States.

Compared to foreign and interior policies, regulatory and distributive policy domains are more likely to meet the pluralist assumption of fairly equal and broad organisational access to decision‐making for several reasons. First, supranational institutions (the Commission, EP and ECJ) are more powerful in domains with greater integration depth. These institutions are also more open to receiving interest group feedback and offering them access to decision‐making than the Council (Coen & Richardson Reference Coen and Richardson2009). Second, opportunities for access by different organisations are enhanced by the very existence of several (three) supranational institutions. Third, in areas characterised by more intergovernmental decision‐making, supranational institutions are less open to input from interest groups: for example, the Commission's dialogue with organisations in CFSP is more informal and less institutionalised than in regulatory areas (Shapovalova Reference Shapovalova, Dialer and Richter2019). Interior policies have been characterised by ‘intergovernmentalism and relative secrecy, making it difficult for NGOs to remain effectively plugged into the process’, and even after the ‘communitarisation’ of these policies they are seen as ‘too sensitive for full NGO inclusion’ (Uçarer Reference Uçarer, Ripoll‐Servent and Trauner2018: 461).

The variation in levels of decision‐making competence and institutional opportunity structures across areas has important implications for how shared country, share interest type and policy insiderness shape the probability of tie formation across domains. We discuss first the implications for the effect of shared country and interest type. In areas where supranational institutions are more powerful, organisations have higher incentives to seek direct access to supranational institutions, lower incentives to cooperate with others and may be less reliant on other organisations for access to relevant, high‐quality information. In these areas, organisations may prefer to influence decisions independently, despite the more competitive nature of the lobbying context. For example, Beyers and de Bruycker (Reference Beyers and De Bruycker2018: 972) find that on 78 EU legislative proposals (covering mostly regulatory and distributive policies), almost half of the organisations chose not to engage in cooperative relations and lobbying coalitions. Given that a large majority of these groups are nevertheless embedded in their national policy communities, this implies that shared country of origin is likely to remain an important consideration in tie formation in regulatory and distributive areas. Conversely, the relatively limited level of cross‐national cooperation between organisations representing the same functional interests implies that shared interest type is significantly less important in tie formation in these domains.

In contrast, limited institutional access to supranational decision‐makers in interior and foreign policies incentivises organisations to collaborate and form of lobbying coalitions. Given the large size of the EU polity, such coalitions tend to be transnational and based on the type of functional interest represented. Research indicates the presence of large‐scale transnational coordination, particularly among NGOs that tend to be the most important actors in interior and foreign policy. Examples include the coordinated effort of more than 600 NGOs to push for the adoption and implementation of an EU code of conduct for arms export (Joachim & Dembinski Reference Joachim and Dembinski2011: 1158), the creation of the NGO Platform on EU Migration and Asylum Policy (Uçarer Reference Uçarer, Ripoll‐Servent and Trauner2018) and the formation of NGO coalitions on issues of visa liberalisation for the EU's Eastern neighbours, EU sanctions on foreign states and CFSP missions (Shapovalova Reference Shapovalova, Dialer and Richter2019: 432). Also, the research on NGOs’ cooperation in international institutions suggests that ‘having access to [international organisations] in order to get and to diffuse information can be a reason for cooperation between NGOs’ (Schneiker Reference Schneiker, Biermann and Koops2017: 326).

The formation of broad and fairly stable coalitions between organisations from different countries that share the interest type represented in interior and foreign policies represents a significant departure from the classic pluralist model of a large number of organisations competing for access and influence in an open political market. Given that such coalitions are formed across countries, we expect that sharing the country of origin matters less for tie formation in interior and foreign policies than in regulatory and distributive policies. Conversely, shared interest type should matter more in foreign and interior policies as coalitions are built among organisations representing the same constituencies of functional interests from different countries. We therefore expect that:

H1b: Organisations sharing the country of origin are more likely to establish a network tie in regulatory and distributive policy areas.3

H2a: Organisations sharing the interest type are less likely to form a network tie in regulatory and distributive policy areas.

We now turn to the discussion of how the extent to which policy domains are close to the pluralist assumption of relatively equal and broad access of organisations to decision‐makers shapes the importance of forming ties with policy insiders. Research emphasises the elite‐pluralist tendencies of EU lobbying and recognises that these tendencies vary across areas depending on the characteristics of the interest group community and of lobbying venues (Eising Reference Eising2007). In domains where organisations have good opportunities for individual, direct access to decision‐making institutions (i.e., regulatory and distributive policies), information from insiders becomes less relevant and valuable. These domains are more plural in the diversity of interests represented, more densely populated and therefore with a higher number of policy insiders. This in turn, may reduce the relative importance and uniqueness of the policy insider status in tie formation. Conversely, when access is limited (i.e., foreign and interior policies), acquiring the status of policy insider is likely to be significantly more difficult and more consequential. Establishing an information tie with an insider in these areas becomes significantly more important than in other areas. We therefore expect that:

H3a: Organisations are less likely to establish information ties with policy insiders in regulatory and distributive policy areas, and, conversely, more likely to establish ties with insiders in foreign and interior areas.

Research design

We use the EU Transparency Register (TR)4 to identify the population of organisations. This constitutes an ideal data source for several reasons. First, it offers the broadest sampling frame to systematically identify organisations participating in EU policymaking. Second, despite existing criticism of its data quality, the Register offers systematic and important information about organisational profiles, domains of policy interest and activity (Ibenskas & Bunea Reference Ibenskas and Bunea2021). Third, the TR is linked to the LobbyFacts.eu dataset,5 which provides key information about the meetings between organisations and high‐level Commission officials. This allows for identifying policy insiders. Fourth, organisations joining the TR indicate which of the 40 EU policy domains they are interested in, allowing one to identify their membership in different networks and explore our argument across policy domains.

We downloaded TR‐data in February 2019. This resulted in a dataset including 11,882 organisations. To identify their Twitter handles, we first conducted an automated search of the first pages of organisational websites with the help of R statistical environment. Links to these websites are available in the TR. Manual checks have then been performed by the authors and research assistants on the Twitter handles identified by automatic searches, as well as for all organisations for which this search did not identify handles. We identified 7,388 with Twitter accounts.

Our dataset includes information about a directed information network, in which actor A (the Ego) follows on Twitter (sends a tie to) actor B (the Alter). The 7,388 organisations in our full network form 27,287,578 organisational dyads. As our network is directed, the number of possible ties is double that value. The outcome variable is dichotomous indicating the presence (1) or absence (0) of a directed tie (A→B). Of these potential ties, 205,288 (0.38 per cent) are actually realised. Low densities are common for large‐scale networks. However, when a tie is formed in one direction (A→B), the likelihood that the tie reciprocated (B→A) is 36.3 per cent. This corresponds to 74,436 dyads in which both actors follow each other. We first evaluate this network as a whole and then subdivide the network into 40 (overlapping) policy domain networks and investigate them separately.

Table 1 in the online Appendix presents key network statistics for the full network and all 40 policy domain networks: they are very sparse, with many organisations within a field being only loosely connected to the network. In line with Cranmer et al. (Reference Cranmer, Leifeld, McClurg and Rolfe2017), we employ ERGMs to model the networks. We use the packages network and ergm in R to implement our analyses.

Explanatory variables

We coded sources of organisational similarity based on TR‐data. We identified eight types of functional interests: business (associations and companies); NGOs; trade unions; professional associations; subnational public institutions; think tanks; consultancies; and academic institutions. We coded countries where organisations have headquarters at the organisation level. We estimate the explanatory variables at the dyad level, indicating whether two organisations share the type of interest represented (1; otherwise 0) and country of origin (1; otherwise 0).

To capture levels of policy insiderness we use a count variable indicating the total number of meetings an organisation had with Commission officials, across DGs and policy domains, between November 2014 (when records started) and February 2019 (when we collected data) based on information available on LobbyFacts.eu website. We use this variable to measure the extent to which the Alter in the organisational dyad is a policy insider.

Control variables: Network and actor‐level characteristics

An alternative explanation for how organisations form ties on Twitter highlights the importance of organisational interdependencies and network features in shaping patterns of contact‐making and tie‐formation (Cranmer et al. Reference Cranmer, Leifeld, McClurg and Rolfe2017). Network structures create interdependencies shaping actors’ choices about whom to trust and with whom to communicate, collaborate and exchange information and resources (Laumann & Knoke Reference Laumann and Knoke1987). They constrain choices, behaviours and communication patterns, which may vary according to levels of network connectivity, transitivity, information transmission efficiency, network prominence and relative position of network members (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Esterling and Lazer2004). We account for network interdependencies in our empirical analyses with the help of ERGMs (Cranmer et al. Reference Cranmer, Leifeld, McClurg and Rolfe2017) and consider a set of variables capturing key structural features of networks and interest groups as network actors (cf. Leifeld & Schneider Reference Leifeld and Schneider2012).

First, we consider a classic network feature: the number of network edges account for the intuition that network density may impact the propensity of tie formation (Scott Reference Scott2017). Second, we account for the effect of reciprocity on tie formation (Leifeld & Schneider Reference Leifeld and Schneider2012): reciprocity is likely to play a role given the need to prevent, adjust and remedy potential informational asymmetries between organisations and their Twitter followers. Organisations have incentives to follow back their Twitter followers to ensure followers do not gain an informational advantage. Third, we account for network transitivity and the importance of local structures (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Esterling and Lazer2004) and shared Twitter friends that may increase the probability of a Twitter‐tie given the importance of trusted and high‐quality information in the EU. This also indirectly accounts for an important Twitter feature: its underlying algorithm may suggest new organisations to follow based on whom an organisation already follows.

Lastly, given the resource‐constraints and cost‐benefit analysis informing the decision of forming a Twitter‐tie, an intuitive expectation is that an organisation is interested in following actors whose accounts provide information about or allow the indirect monitoring of a high number of actors. We control for the possibility that an organisation is more likely to follow other organisations with a high degree of incoming ties. We use the degree of centralisation in the network to capture this. A negative effect indicates a tendency of an increasing number of organisations to follow the same actors, who thus become of particular importance for network structuring and act as bridges between network clusters (Levy & Lubell Reference Levy and Lubell2018).

We include a set of variables capturing the key structural features of networks and organisations as network actors: Edges is a baseline measure for network density; Mutual captures reciprocity; and Gwindegree captures the in‐degree centrality of the organisation receiving a Twitter‐tie (Alter), accounting for the argument that actors with high levels of network popularity are more likely to be followed by others because their privileged network location. Gwesp captures the level of network transitivity (Goodreau et al. Reference Goodreau, Kitts and Morris2009) and accounts for the importance of local structures (Levy & Lubell Reference Levy and Lubell2018).

We also include actor‐level characteristics like controls. We account for the number of Twitter statuses of actors in dyads to control for the possibility that tie formation is driven by actors’ overall Twitter usage. We account for whether the Ego or the Alter is an EU‐level federation. These are preferred dialogue partners for EU institutions that may facilitate policy insiderness, driving others to follow them. Conversely, EU federations know their privileged status comes from being perceived as actors that have a broad, pan‐European representative mandate and speak on behalf of an extensive membership. This augments their informational needs and incentives to actively monitor information on social media and contact others. We use the number of policy interests/areas the actors in the dyad share to control for whether some organisations had more opportunities to interact with each other as part of multiple and overlapping memberships in policy domains.

ERGM analyses of network ties

We test our three baseline hypotheses (H1, H2, H3) with the help of ERGM analyses applied to the full network and the 40 policy domain networks and present the results in this section. In the next section, we continue with a test of our expectations at the policy domain level and H1a, H1b, H2a and H3a.

Due to word‐limit constraints, we present our 41 full ERGM‐results in Online Appendix 1 (Tables 2–4). The results for the three key variables, shared country, shared interest type and insiderness are presented in Figure 1 for the full network and in Figure 2 for the 40 policy domain networks.

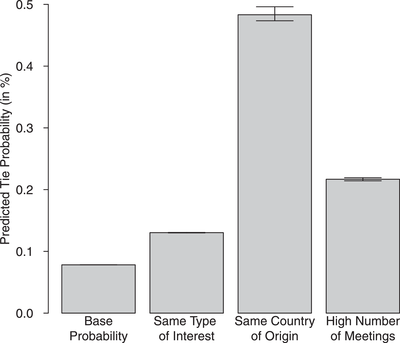

Figure 1. Predicted probabilities of tie formation in the full network.

Note: The computation of probabilities: explained in text.

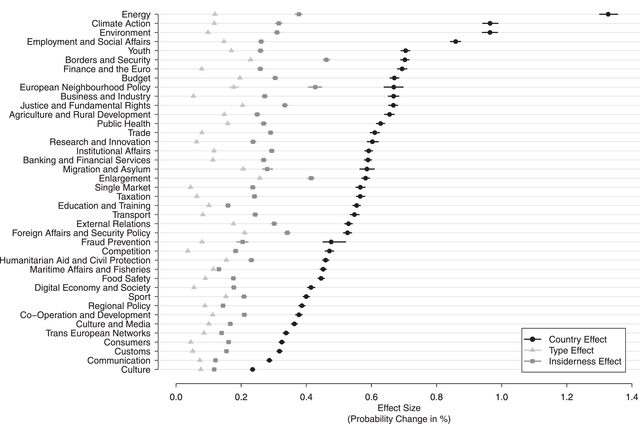

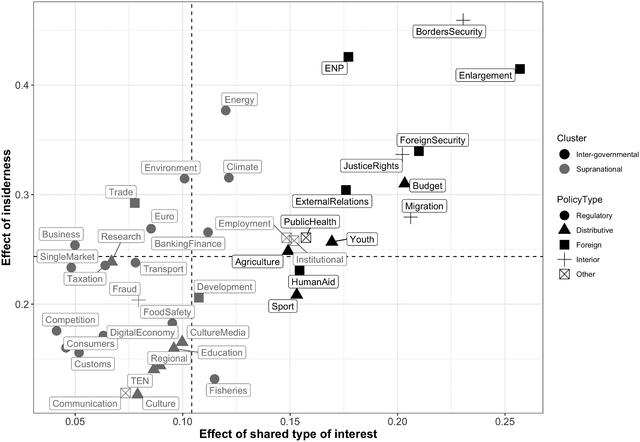

Figure 2. Changes in predicted probabilities for country and interest type homophily and the effect of policy insiderness across 40 policy domains.

Note: Effect sizes are extracted from 40 policy domain‐specific models. Full model estimates in Online Appendix 1.

To ensure our coefficients are comparable across networks, we followed Faust and Skvoretz (Reference Faust and Skvoretz2002) and calculated predicted tie probabilities for all edges in the network based on the models. Then, for all dyads with specified characteristics, we calculate the average tie probability across the network to obtain our predicted values. We use 1000 bootstrap iterations to calculate confidence intervals. For example, in the full model we calculate a base probability of tie formation over all dyads that do not have shared country, shared interest type and for which actors have a policy insiderness (EC meetings for Alter) value of zero. This baseline probability is 0.078 per cent, (first bar in Figure 1) and denotes the likelihood of two groups with the mentioned characteristics forming a tie. Keeping the other characteristics constant, but changing to groups with shared interest type, the second bar in Figure 1 shows that the likelihood of tie formation increases to 0.13 per cent. Thus, the actual effect size is 0.052 per cent. This is the difference between the base value and the predicted tie formation value for shared interest type and represents the increase in the likelihood of tie formation explained by interest type homophily. For country homophily, this effect size in the full model is 0.405 per cent (0.483 per cent – 0.078 per cent). Effect sizes calculated in this way (by subtracting the baseline probability of forming ties from the appropriate probability when changing the value of one focus variable) are shown in Figure 2 for all 40 policy domain networks.

Hypothesis 1 states that organisations sharing country of origin are more likely to form ties. This is strongly substantiated across all models. The country homophily effect is, compared to other variables of interest, substantively stronger and more pronounced across models (Figure 2). In the full‐network model, the country homophily effect size is approximately 0.405 per cent, meaning that dyads from the same country are more than six times more likely to form ties than two randomly selected organisations with different country backgrounds. This very substantial effect is found in all policy networks and ranges from 0.235 per cent in the Culture policy to more than 1.327 per cent in the Energy network. This means a more than seven times increase in the predicted likelihood of tie formation for organisations from the same country in the Energy domain (from 0.217 per cent to 1.544 per cent).

Hypothesis 2 posits that organisations sharing interest type have a higher likelihood to form ties. This is supported across all models. As explained above, in the full‐network model the shared interest type coefficient is 0.46, and the effect size is 0.052 per cent. While this might seem a very small effect, the likelihood that two organisations sharing interest type form a tie is about two‐thirds larger than for organisations not sharing interest type. Across policy domains both the base values and the effect sizes tend to be somewhat larger because these networks have a higher density. The estimates for the effect size of shared interest type range from 0.036 per cent (competition) to 0.257 per cent (enlargement). In the latter case, this represents more than a doubling of the likelihood of tie formation when going from dyads with different interest types to those that share an interest type. While all policy level effects for this variable are highly significant, there is clearly significant variability across policy domains regarding how closely knit information networks are among organisations representing similar interests. Yet, in all cases the effects are substantial, indicating that shared interests make actors more likely to establish a tie.

Hypothesis 3 posits that organisations are more likely to establish a tie with policy insiders. The variable measuring policy insiderness is significant across all models, and the effect is substantive in magnitude. Insiders are highly sought‐after information sources. For one additional meeting with policymakers, the likelihood of being followed by another organisation increases by slightly more than 0.034 per cent in the full‐network. An organisation at or above the 90th percentile of the insiderness variable has 11 or more meetings and is predicted to have a 0.383 per cent higher likelihood to be followed than an organisation without any meetings. This effect size varies across policy domains from 0.117 per cent (Culture) to 0.461 per cent (Borders and security).

We now briefly discuss the effects of controls. Organisations with a higher number of Twitter statuses are better connected in the full network and in all policy networks than less Twitter‐active organisations (incoming and outgoing ties combined). This effect is very substantial in magnitude. EU federations exhibit mixed patterns. While significance levels vary, in many models (full‐network included), these organisations are more active in following others. EU federations are also significantly more followed in 11 networks (full‐network included), but in nine other networks the models show negative significant effects and thus a lower probability of being followed. In the remaining models, the term is insignificant. Together, these findings only weakly support the argument that EU federations are perceived as particularly relevant information sources. The effects of the number of shared interests in policy domains are positive in all but one of our models. This supports the intuition that having more shared policy domain experiences increase the likelihood of tie‐formation (Leifeld & Schneider Reference Leifeld and Schneider2012).

We also observe network effects. The reciprocity measure is positive, statistically significant and large in magnitude across models. The reciprocity coefficient of 3.33 in the full‐network model indicates that if we observe a tie from A→B, the likelihood that B follows back increases by almost 248 times compared to the baseline likelihood. In the policy network with the second smallest value (1.90; Banking), this still translates to a 6.7 times higher likelihood of following back than to follow a random group. The GWindegree effects are also highly significant and exhibit the same direction across models. The consistently negative coefficients indicate a tendency of organisations to follow particularly popular organisations, which are key for network formation.

Transitivity is also significant in all policy domain networks, indicating a high likelihood of triad closure. For instance, in the Regional policy, if A→B, and B→C, then the likelihood of C→A is predicted to increase about 2.6 times. Micro‐structures play an important role in network formation and structuration. However, despite all the positive and significant effects across policy domain networks, the coefficient in the full‐network model is negative and significant. This emphasises the importance of conducting an analysis at the policy domain level: while within given policy fields micro‐structures are important, their significance is flushed out by the noise introduced when observing and analysing all policy domain networks together.

Explaining tie formation in policy context

In this section, we examine the variation in the strength of organisational similarity and insiderness effects on tie formation across policy domains.

Regression analysis of policy domains

We start with the regression analysis as a direct test of H1a, H1b, H2a and H3a. The unit of analysis is the policy domain. The three dependent variables in these analyses are the effect size of the three explanatory variables (shared country, shared interest type and policy insiderness) in the ERGM models conducted for each policy domain and presented in Figure 2. The main explanatory variable in the regression analysis (policy type) differentiates between regulatory (15 domains including Internal market, related market‐corrective policies, Monetary policy), distributive (e.g., Agriculture, Regional policy; 10 domains), interior (4) and foreign (7) policies. Institutional affairs and Communication domains are coded as Other category, which includes Employment and Social affairs and Public health.

We include the number of organisations in policy domain as a control variable and account for the intuition that interest group community size shapes organisational considerations about collaborations and information exchanges. We also control for the share of business in the policy domain community. Beyers and de Bruycker (Reference Beyers and De Bruycker2018) suggest that business, as more powerful and resourceful actors, coalesce less than public interest groups. Sectoral divisions can reduce the propensity to form ties among them. A higher share of business could therefore decrease the importance of shared interest type while increasing the effect of country homophily in tie formation (due to limited cooperation of business across country lines). Business actors are also less dependent on policy insiders for information.

Since linear regression diagnostics (including Cook's distance measure) show the considerable influence of several observations (particularly Fraud prevention) in all models, we fit robust regression models. We opt for MM‐estimator, a commonly employed robust regression technique that is characterised by a high breakdown point and high efficiency (Andersen Reference Andersen2008). Linear regression models on sub‐sets of data excluding outliers lead to similar results.

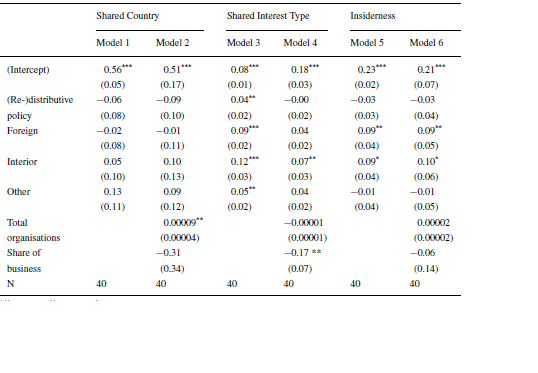

Table 1 presents the estimates of six robust regression models, two for each dependent variable. We contextualise our regression findings using Figures 3 and 4, which plot the estimates from ERGM models (same quantities as in Figure 2), while indicating the policy type for each policy domain.

Table 1. Explaining the effect of organisational homophily and insiderness in policy context

*** p <0.01; **p <0.05; *p<0.1.

Robust regression models with MM‐estimator. Reference category: regulatory policies.

Models 1 and 2 in Table 1 suggest no clear effect of policy domain type on how important shared country of origin is for tie formation. In contrast to H1a, regulatory policies do not display a systematic pattern in which shared country is less relevant for tie formation than in other domains. Regulatory and distributive policies do not display a pattern in which country homophily matters more for tie formation compared to foreign and interior policies. This challenges H1b.

This null finding may result from the partially opposite expectations of H1a and H1b. On the one hand, in regulatory policies country homophily may indeed be a weaker source of shared preferences due to business groups across country borders perceiving the benefits of a well‐developed single market (as per H1a). On the other hand, better access opportunities in regulatory policies reduce the institutional incentives for groups from different countries to collaborate, thus increasing the effect of country homophily (following the logic of H1b).

The variation in the effect of country homophily on tie formation across regulatory policies (x‐axis in Figure 3) corroborates this argument. In this group, three policies with a strong environmental dimension (Environment, Climate and Energy) stand out as displaying a strong effect of shared country of origin on tie formation. This is potentially because the logic of H1a (lower expected effect of country homophily on tie formation due to shared policy preferences across country borders) is less applicable to this subset of policies: organisations from economically more advanced countries are likely to prefer ‘greener’ policies compared to organisations from less wealthy countries. However, the logic of H1b (expecting a higher effect of country homophily on tie formation due to more favourable opportunities for institutional access) is applicable to these policies and consistent with the more prominent role of country homophily in the tie formation we observe in these areas. In contrast, for most other regulatory policies that are mostly concerned with economic regulation, both H1a and H1b apply. Consequently, many of these policies (e.g., Single market) display levels of country homophily effects on tie formation that are close to the median score in the sample.

Our findings provide more support to H2a. Model 3 indicates that in foreign and particularly interior policies, shared interest type plays a more significant role in tie formation than in regulatory and distributive domains. This is consistent with the argument that in policy domains with greater restrictions on access to decision‐makers, organisations have incentives to exchange information based on shared interest type.

Figure 3 (y‐axis) further supports this argument by showing an interesting variation within foreign and interior policies. Economic foreign policies (Trade and Development), characterised by a more supranational mode of governance, display a pattern in which shared interest type is substantially less impactful on the probability of tie formation than in foreign policies with a stronger political dimension and more inter‐governmental decision‐making (CFSP). A similar pattern marks interior policies: interest type homophily matters less for tie formation in policies with stronger economic elements (Fraud) than in the more political interior policies (Borders and Security).

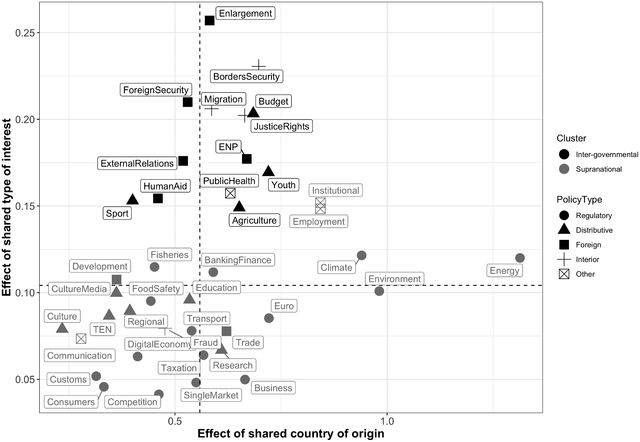

Figure 3. Changes in predicted probabilities for country and interest type homophily by policy type and cluster.

Note: Effect sizes are extracted from 40 policy domain‐specific models.

We find strong support for H3a. The effect of insiderness on tie formation is much weaker in regulatory and distributive policies than in foreign and interior policies. This supports the argument that in policy domains where intergovernmental decision‐making predominates and the ‘depth’ of European integration is limited, organisations are in greater need of information from policy insiders and thus more likely to follow them on Twitter. The variation across individual domains further supports this (Figure 4). Foreign and interior policies that are more ‘political’ and experience more intergovernmental decision‐making (Borders, Migration) are characterised by a stronger effect of insiderness on tie formation than the more ‘economic’ foreign and interior policies (Fraud).

Figure 4. Changes in predicted probabilities for interest type homophily and policy insiderness by policy type and cluster.

Note: Effect sizes are extracted from 40 policy domain‐specific models.

Regarding our controls, Table 1 shows that a larger lobbying community increases the importance of country homophily for tie formation, while a larger share of business decreases the importance of shared interest type. This highlights the importance of interest group community characteristics for tie formation and supranational lobbying across policy domains (Berkhout et al. Reference Berkhout, Carroll, Braun, Chalmers, Destrooper, Lowery, Otjes and Rasmussen2015).

Further context: Clusters of policy domains

To further contextualise our regression analysis, we conduct a cluster analysis for the 40 policy domains and the three dependent variables in Table 1 models. We use the model‐based clustering implemented through Gaussian mixture modelling provided by the mclust package in R (Scrucca et al. Reference Scrucca, Fop, Murphy and Raftery2016). We select the EVE (ellipsoidal, equal volume and orientation) model with 2 clusters. This model was suggested by BIC and ICL criteria. Figures 3 and 4 report the classification of policies into clusters.

The cluster analysis supports the results of the regression models emphasising the differences between more supranational and more inter‐governmental policies. The supranational cluster includes 27 out of 40 policies. This cluster includes all 15 regulatory policies, the majority of distributive policies (6 out of 10) and three foreign and interior policies with a strong economic element (Fraud, Trade, Development). The intergovernmental cluster includes seven foreign and interior policies with a stronger political dimension and four distributive policies.

The two clusters differ significantly regarding the effect of shared interest type and insiderness on tie formation. The average effect of shared interest type in the supranational cluster is 0.09 per cent, but 0.19 per cent in the intergovernmental one. The SD in the effect size of interest type homophily across 40 policy domains is 0.06. The two clusters differ by almost two SDs. The mean levels of insiderness effect on tie formation in supranational and intergovernmental clusters are 0.21 per cent and 0.31 per cent, respectively. This marks a difference of more than one SD (0.08). The two clusters differ less in relation to country homophily effect (0.60 per cent and 0.56 per cent).

Our regression and cluster analyses suggest that decision‐making mode is crucial for understanding interest group information networks in the EU. In more supranationalised policy domains, first and foremost economic‐regulatory policies, tie formation is driven less by shared interest type and insiderness. In more intergovernmental policy domains, interest type homophily and insiderness become more relevant. However, shared country of origin is the most significant driver of tie formation in both clusters.

Robustness checks

Online Appendix 2 presents a robustness check analysis of the results in Table 1 using the ‘depth’ of European integration based on Börzel (Reference Börzel2005) and Leuffen et al. (Reference Leuffen, Rittberger and Schimmelfenning2013) as the main explanatory variable. Although this is a more direct measure (compared to policy domain categories) for testing the logic underpinning H1b, H2a and H3a, its use is limited due to substantial differences in the policy domain categories we use and the EU TR policy categories. Furthermore, the formal decision‐making procedures established in EU primary legislation underpinning the indices of integration depth and the policymaking practice do not always perfectly align.6

We find clear evidence that increased levels of integration depth reduce the effect of interest type homophily and insiderness on tie formation. This reinforces our findings that these two variables were more important for tie formation in the more intergovernmental foreign and interior policies, thus further supporting H2a and H3a. However, these analyses show no effect of integration depth on country homophily effects, thus providing evidence against H1b.

Online Appendix 2 also shows the ERGM models for the full network with interaction effects between our three explanatory variables and the five‐category policy domain variable. The results are substantively similar to those in Table 1.

Conclusions

We examined interest groups’ information networks across EU policy areas using a new dataset and social media data. We argued that in the complex EU polity, organisations prioritise access to trustworthy and high‐quality information coming from partners with shared policy goals. Thus, key organisational similarities such as country of origin and interest type represented, alongside policy insiderness, are fundamental in explaining tie formation in information networks. We further argued that the effect of these factors on network tie formation varies across EU policy domains depending primarily on the extent to which the institutional setting assures fairly equal and broad organisational access to decision‐making. Our findings show that country homophily is consistently a strong predictor of tie formation across policy domains. However, the variation in the effect of shared country of origin on tie formation is challenging to explain, potentially because policy domains vary both in relation to their institutional characteristics and the extent to which shared country of origin is a source of shared policy preferences. Shared interest type and policy insiderness are also strong predictors of tie formation across policy domains but to a lower extent compared to country of origin. The effect of shared interest type and policy insiderness is stronger in the policy areas marked by strong intergovernmental decision‐making and limited organisational access to decision‐makers.

Several implications follow. First, the high importance of shared country of origin on tie formation across policies reiterates the importance of interest group embeddedness in national policy networks that supports and underpins their lobbying at the supranational level. This corroborates what previous studies found when investigating multi‐level lobbying and the Europeanisation of interest groups: organisations lobbying Brussels maintain strong national roots and the national systems of interest representation structure organisational networks at the supranational level (Beyers & Kerremans Reference Beyers and Kerremans2012; Kohler‐Koch & Friedrich Reference Kohler‐Koch and Friedrich2020). Second, our findings indicate the importance of systemic, institutional features on groups’ information networks, attesting once again the efforts made by EU institutions to shape lobbying and interest representation at the supranational level (Eising Reference Eising2007). For example, by deciding who gains access to them, institutions decide which organisations become policy insiders and key sources of information for others (Beyers & Kerremans Reference Beyers and Kerremans2004). When they restrict organisations’ access to them and decision‐making, this motivates organisations to form coalitions based on interest type and, thus, reinforce functional representation in EU policymaking. Third, our findings highlight the contextual nature of supranational lobbying and information networks in line with previous research (Klüver et al. Reference Klüver, Braun and Beyers2015) and emphasise the importance of comparative, cross‐policy analyses of EU lobbying that has been highlighted as a gap in the research on EU interest groups (Bunea & Baumgartner Reference Bunea and Baumgartner2014). Fourth, our findings about the strong effect of country homophily on tie formation underline the continued relevance of the intergovernmental channel of interest representation in the EU, in line with a core assumption of the liberal intergovernmentalist theory of European integration. At the same time, the lack of correlation between the importance of country homophily in tie formation and policy type revealed by our analyses qualifies the assumption made in the supranational governance theory about the higher importance of cross‐national preference similarity in economic regulatory areas when compared to other domains.

While our study contributes to the understanding of EU lobbying and policymaking, it is also marked by a set of limitations that present venues for future research. First, our study captures only formally established information ties on Twitter. EU lobbying may well consist of informal networks that cannot be fully captured by our design. Second, the extent to which information ties translate into coordinated policy coalitions remains an empirical puzzle worthy of further research. Third, our study excludes information about the substantive content of information being exchanged through Twitter‐ties and does not allow the study of bargaining or persuasion networks established between organisations or organisations and policymakers. This goes beyond the scope of our research but constitutes a venue for future inquiry. Lastly, our design does not account for the impact of algorithms used by Twitter to encourage tie formation by making suggestions on whom to follow. Although our network analysis partially accounts for the interdependencies resulting from such algorithms, future research could further investigate the effects of social media algorithms on groups’ lobbying behaviour and social media usage as part of a new form of lobbying strategy.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Elin Haugsgjerd Allern, Vibeke Wøien Hansen, Bjørn Høyland, Carl Henrik Knutsen and the anonymous referees for their excellent comments and feedback. They would like to thank Idunn Johanne Bjøve Nørbech and Soran Hajo Dahl for their excellent research assistance. This research received support from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (ERC StG 2018 CONSULTATIONEFFECTS, grant agreement no. 804288).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supplementary information