1. Introduction

The effects of fiscal policy on the economy are a topic of continuing disagreements among Keynesian and neoclassical economists, as well as policymakers. In contrast to monetary policy, the macroeconomic effects of fiscal policy are relatively more controversial. During the global financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic fiscal stimulus moved center stage. However, high inflation in the post-pandemic period raises questions about the impact of fiscal stimulus packages. The commonly used measure of fiscal policy effectiveness is the fiscal multiplier. It describes the effect of an exogenous change in a fiscal policy instrument, be it an unexpected government spending or tax change, on real GDP. The literature on empirical fiscal multipliers is extensive. Multipliers generally range in value from 0.6 to 2 for government spending and -5 to 0 for tax changes (Ramey, Reference Ramey2019, Table 1, p. 102, and Table 2, p.105, respectively). Multipliers may also depend on the state of the economy.

In regards to the identification of fiscal shocks in structural vector-autoregressive (SVAR) models, there are several common approaches in the empirical literature. The seminal study of Blanchard and Perotti (Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002), as well as further work by Perotti (Reference Perotti2004), rely on imposing contemporaneous restrictions on the structural coefficient matrices in an SVAR. Such restriction are based on externally calculated elasticities of government spending and taxes with respect to output and other variables included in the VAR.Footnote 1 More recently, several authors have relied on identification through sign restrictions with penalty function (Mountford and Uhlig, Reference Mountford and Uhlig2009), the use of narrative fiscal shocks derived from outside the SVAR (Ramey, Reference Ramey2011; Romer and Romer, Reference Romer and Romer2010), or on narrative shocks used as external fiscal and non-fiscal instruments in so-called proxy-SVARs (Mertens and Ravn, Reference Mertens and Ravn2014; Caldara and Kamps, Reference Caldara and Kamps2017; Angelini et al. Reference Angelini, Caggiano, Castelnuovo and Fanelli2023).

The crucial point for our study is that the values of contemporaneous fiscal elasticities play a critical role for the size of the multipliers in the SVAR literature. Mertens and Ravn (Reference Mertens and Ravn2014) use a proxy-SVAR with narratively identified unanticipated tax shocks. They compare result from such a proxy-SVAR to a standard SVAR with externally imposed elasticities as in Blanchard and Perotti (Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002). Mertens and Ravn (Reference Mertens and Ravn2014) show that the tax multiplier in standard SVARs can range from an absolute value near one (Blanchard and Perotti, Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002) to values of around two or three, depending on the size of the output elasticity of tax revenues. They argue that lower tax multiplier values in previous studies can be explained by an imposed output elasticity of tax revenue value that is contradicted by empirical evidence. Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017) demonstrate that the differences in fiscal multiplier estimates in SVARs can be analytically accounted for by different assumptions for the systematic response of tax and spending policies to output. Different fiscal rules lead to different identification schemes and different empirical multipliers. They propose instead a proxy-SVAR that uses non-fiscal external instruments to directly identify and estimate the parameters of alternative fiscal rules, without imposing external elasticities. Furthermore, Angelini et al. (Reference Angelini, Caggiano, Castelnuovo and Fanelli2023) also use a proxy-SVAR and show the set of instruments used can crucially affect multiplier, as is the case for imposing or not imposing an orthogonality assumption between tax shocks and their factor productivity shock. Also, external instruments in proxy-SVARs may be weak (Stock and Watson, Reference Stock and Watson2018), or altogether not valid (Nguyen, Reference Nguyen2025).

Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2015, Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2018, Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2019) develop a new approach for identifying structural relationships in a VAR model. The identification of structural shocks requires prior information about underlying economic relationships that are external and supplementary to the VAR model itself. Their methodology employs Bayesian priors to account for a researcher’s uncertainty around imposed identifying assumptions. The traditional and most commonly used approaches to identifying structural shocks in SVARs are to impose zero restrictions on contemporaneous relationships among structural shocks, specific values for variables’ elasticities to shocks, and/or sign restrictions. Instead of imposing such identifying restrictions as if they were know with certainty, Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2015) propose to explicitly account for the degree of uncertainty surrounding a researcher’s prior information. As outlined in Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2019), their approach allows for imposing varying degrees of a priori uncertainty about identifying values imposed, as well as for setting sign restrictions. In addition, it can deal with structural instability by assigning different weights to observations from different time periods. So far, the methodology has been applied to quantify the impact of monetary policy shocks in the U.S. economy (Baumeister and Hamilton, Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2018) and to evaluate the elasticities on the U.S. oil and natural gas markets (Baumeister and Hamilton, Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2019; Rubaszek, et al. Reference Rubaszek, Szafranek and Uddin2021). To the best of our knowledge, this framework has not been exploited to broaden the understanding of U.S. fiscal policy and pin down precisely fiscal elasticities.

We contribute to the existing literature across several margins. First, our model specification produces sensible estimates that allow us to assess the effects of fiscal policy while controlling for monetary policy for the U.S. economy. We estimate the level of fiscal multipliers. Second, we provide estimates of posterior short-term elasticities by applying Baumeister and Hamilton’s methodology. Third, we present a number of robustness checks where we change the prior assumptions the lag length, and we include post-Covid-19 observations.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. In Section 2 we briefly review the related literature. Section 3 presents the Bayesian econometric model. Section 4 is dedicated to the data and the empirical specification, along with the choice of specific prior distributions. Empirical results are discussed in Section 5 and their sensitivity to modifications in the baseline model is explored in Section 6. Finally, Section 7 concludes the analysis.

2. Literature review of closely related fiscal SVAR models

Blanchard and Perotti’s (2002) widely cited study forms the foundation for most subsequent empirical research on fiscal multipliers. In their approach fiscal shocks are identified by using institutional information about the tax and transfer systems to specify the automatic response of taxes and spending to economic activity and, then, by imposing externally calculated elasticities. Blanchard and Perotti (Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002) use a trivariate SVAR model: the logarithms of quarterly government spending, GDP, and taxes, all in real and per capita terms.Footnote 2 Their main findings are the following. Government spending increases cause output to increase, while tax increases cause output to decrease. Spending multipliers are close to one and they depend on different components of output, meaning that private consumption increases following a government spending increase, while private investment is crowded out to some degree.

Mountford and Uhlig (Reference Mountford and Uhlig2009) and Mertens and Ravn (Reference Mertens and Ravn2014) apply similar data as in Blanchard and Perotti (Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002) but use a different methodology. Mertens and Ravn (Reference Mertens and Ravn2014) use a proxy-SVAR with unanticipated narrative tax shocks as an external proxy (instrument variable) and they allow for measurement error in the narrative tax shocks. On the other hand, Mountford and Uhlig (Reference Mountford and Uhlig2009) set instead sign restrictions on VAR impulse responses to achieve identification. They use a so-called penalty function approach, that rewards large impulse responses in the right directions more than small responses and penalizes responses of the wrong sign. Their sample covers the period from 1955 to 2000 for U.S. data. Mountford and Uhlig (Reference Mountford and Uhlig2009) consider three scenarios: deficit-spending, deficit-financed tax cuts and a balanced budget spending expansion.Footnote 3 They find that deficit-financed tax cuts are the most effective among the three scenarios with the largest present value multiplier equal to five after five years. Mountford and Uhlig (Reference Mountford and Uhlig2009) also find that deficit spending weakly stimulates the economy, more precisely, it crowds out private investment but without interest rate increases and without real wage increases.

The two papers that are most closely related to ours are Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017) and Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2008). They use a VAR model with five equations, as we do, including in addition to the three variables used by Blanchard and Perotti (Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002) inflation and an interest rate.Footnote

4

Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2008) is a comparative study on using different approaches for fiscal shock identification in VAR models and in our view can be seen as an extended introduction to Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017). Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017) argue that the differences in fiscal multiplier estimates can be analytically accounted for by different assumptions for the systematic response of tax and spending policies to output (

![]() $\alpha _{ty}$

and

$\alpha _{ty}$

and

![]() $\alpha _{gy}$

, respectively). This is an important finding in the context of our analysis. It means that assumptions on

$\alpha _{gy}$

, respectively). This is an important finding in the context of our analysis. It means that assumptions on

![]() $\alpha _{gy}$

and

$\alpha _{gy}$

and

![]() $\alpha _{ty}$

should strongly affect our results. Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017) apply a proxy-SVAR model with various non-fiscal instruments. Their results show a positive and large systematic response of taxes to output (

$\alpha _{ty}$

should strongly affect our results. Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017) apply a proxy-SVAR model with various non-fiscal instruments. Their results show a positive and large systematic response of taxes to output (

![]() $\alpha _{ty}$

), and a small but negative systematic response of government spending to output (

$\alpha _{ty}$

), and a small but negative systematic response of government spending to output (

![]() $\alpha _{gy}$

). They note that the implied government spending multipliers tend to be larger than government tax multipliers. Mertens and Ravn (Reference Mertens and Ravn2014), however, find the opposite.

$\alpha _{gy}$

). They note that the implied government spending multipliers tend to be larger than government tax multipliers. Mertens and Ravn (Reference Mertens and Ravn2014), however, find the opposite.

Mertens and Ravn (Reference Mertens and Ravn2014) and Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017) agree on the crucial importance of the output elasticity of tax revenue. In their approach the short-term elasticities are estimated and no prior information for them is needed. Also Angelini et al. (Reference Angelini, Caggiano, Castelnuovo and Fanelli2023) present a wide range of possible elasticities of government spending and tax responses to output, for fiscal and non-fiscal instruments in a proxy-SVAR. The output elasticity of government spending for detrended data ranges from

![]() $-0.32$

to

$-0.32$

to

![]() $0.00$

and the output elasticity of tax revenue ranges from

$0.00$

and the output elasticity of tax revenue ranges from

![]() $2.15$

to

$2.15$

to

![]() $4.40$

, depending on the set of instruments used and whether imposing orthogonality between the tax shock and factor productivity shock (cf. Table A2 in Angelini et al. Reference Angelini, Caggiano, Castelnuovo and Fanelli2023). Angelini et al. (Reference Angelini, Caggiano, Castelnuovo and Fanelli2023) use the sample between 1950Q1 and 2006Q4, which makes their results comparable with the study of Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017) and enables them to use the publicly available proxies form Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017), but it prevents full comparison with our study.

$4.40$

, depending on the set of instruments used and whether imposing orthogonality between the tax shock and factor productivity shock (cf. Table A2 in Angelini et al. Reference Angelini, Caggiano, Castelnuovo and Fanelli2023). Angelini et al. (Reference Angelini, Caggiano, Castelnuovo and Fanelli2023) use the sample between 1950Q1 and 2006Q4, which makes their results comparable with the study of Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017) and enables them to use the publicly available proxies form Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017), but it prevents full comparison with our study.

Carriero et al. (Reference Carriero, Marcellino and Tornese2024) extend the proxy-SVARs and sign/narrative restricted SVARs to using additionally heteroskedasticity for identification purposes. They assume that the variance of structural shocks follows a regime-switching process. It is further assumed that regime changes are either known or can be determined with change-point specifications, however, the contemporaneous shock-impact matrix is assumed to be time invariant. They apply, among other examples, a blended proxy-SVAR with narrative U.S. personal and corporate income tax shocks as external instruments to data spanning 1951Q1 to 2006Q4. Median responses in a proxy-SVAR with heteroskedasticity are largely similar to those with homoskedasticity. But, importantly, heteroskedasticity produces narrower confidence intervals and hence more precise estimates.

3. Methodology

In this section we outline the methodology for Bayesian estimation of parameters of the fiscal structural VAR, which will be specified in the next section. The form of the model is:

In this notation

![]() $\mathbf{y}_t=(y_{1t}, \ldots , y_{nt})'$

is an

$\mathbf{y}_t=(y_{1t}, \ldots , y_{nt})'$

is an

![]() $n\times 1$

vector of endogenous variables,

$n\times 1$

vector of endogenous variables,

![]() $\mathbf{A}$

is an

$\mathbf{A}$

is an

![]() $n\times n$

matrix containing contemporaneous structural relationships,

$n\times n$

matrix containing contemporaneous structural relationships,

![]() $\mathbf{x}_{t-1}$

is a

$\mathbf{x}_{t-1}$

is a

![]() $k\times 1$

vector,

$k\times 1$

vector,

![]() $k=mn+1$

, consisting of

$k=mn+1$

, consisting of

![]() $m$

lags for

$m$

lags for

![]() $\mathbf{y}_t$

and a constant,

$\mathbf{y}_t$

and a constant,

![]() $\mathbf{x}_{t-1}^{\prime}= (\mathbf{y}_{t-1}^{\prime},\dots ,\mathbf{y}_{t-m}^{\prime},1)'$

,

$\mathbf{x}_{t-1}^{\prime}= (\mathbf{y}_{t-1}^{\prime},\dots ,\mathbf{y}_{t-m}^{\prime},1)'$

,

![]() $\mathbf{B}$

is an

$\mathbf{B}$

is an

![]() $n \times k$

matrix of parameters of lagged variables,

$n \times k$

matrix of parameters of lagged variables,

![]() $\mathbf{u}_t$

is an

$\mathbf{u}_t$

is an

![]() $n \times 1$

vector of uncorrelated structural shocks and

$n \times 1$

vector of uncorrelated structural shocks and

![]() $\mathbf{D}=\mathop {\mathrm{diag}}(d_{11},\ldots ,d_{nn})$

represents a diagonal matrix of size

$\mathbf{D}=\mathop {\mathrm{diag}}(d_{11},\ldots ,d_{nn})$

represents a diagonal matrix of size

![]() $n\times n$

. We denote

$n\times n$

. We denote

![]() $\mathbf{a}_i$

row i of

$\mathbf{a}_i$

row i of

![]() $\mathbf{A}$

.

$\mathbf{A}$

.

We estimate the parameters of model (1) with Baumeister and Hamilton’s (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2015, Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2019) Bayesian methodology. The key appealing feature of this approach is that it allows us to formulate identifying assumptions of the structural VAR in a very flexible fashion. We can set prior distributions for each parameter in

![]() $\mathbf{A}$

matrix separately and we identify the shocks by setting a number of sign and zero restrictions. In what follows, we shortly describe the methodology. We refer the reader to the source articles by Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2015, Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2019) for the detailed description and discussion. For the sake of transparency, we keep our notation almost identical to that in the source articles.

$\mathbf{A}$

matrix separately and we identify the shocks by setting a number of sign and zero restrictions. In what follows, we shortly describe the methodology. We refer the reader to the source articles by Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2015, Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2019) for the detailed description and discussion. For the sake of transparency, we keep our notation almost identical to that in the source articles.

Prior. We start by eliciting the prior for all unknown parameters included in model (1). The prior is decomposed into three parts:

The prior for the covariance matrix,

![]() $p(\mathbf{D|A})$

, can be expressed as a product of priors for its elements:

$p(\mathbf{D|A})$

, can be expressed as a product of priors for its elements:

\begin{equation} \begin{split} p(\mathbf{D|A}) & = \prod _{i=1}^{n}p(d_{ii}|\mathbf{A}) \\ d_{ii}^{-1}|\mathbf{A} & \sim \Gamma (\kappa _i,\tau _i(\mathbf{A})), \end{split} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{split} p(\mathbf{D|A}) & = \prod _{i=1}^{n}p(d_{ii}|\mathbf{A}) \\ d_{ii}^{-1}|\mathbf{A} & \sim \Gamma (\kappa _i,\tau _i(\mathbf{A})), \end{split} \end{equation}

with

![]() $x\sim \Gamma (\kappa ,\tau )$

, following a Gamma distribution with the shape and rate parameters

$x\sim \Gamma (\kappa ,\tau )$

, following a Gamma distribution with the shape and rate parameters

![]() $\kappa$

and

$\kappa$

and

![]() $\tau$

, respectively, where

$\tau$

, respectively, where

![]() $E(x)=\kappa /\tau$

and

$E(x)=\kappa /\tau$

and

![]() $Var(x)=\kappa /\tau ^2$

; and

$Var(x)=\kappa /\tau ^2$

; and

![]() $d_{ii}$

is the

$d_{ii}$

is the

![]() $(i, i)$

element of

$(i, i)$

element of

![]() $\mathbf{D}$

. The above notation stresses the fact that the rate parameter depends on the value of matrix

$\mathbf{D}$

. The above notation stresses the fact that the rate parameter depends on the value of matrix

![]() $\mathbf{A}$

.

$\mathbf{A}$

.

The prior for the matrix of parameters of lagged variables,

![]() $p(\mathbf{B|A,D})$

, is a product of priors for its individual rows

$p(\mathbf{B|A,D})$

, is a product of priors for its individual rows

![]() $\mathbf{b}_{i}$

:

$\mathbf{b}_{i}$

:

\begin{equation} \begin{split} p(\mathbf{B|A,D}) & = \prod _{i=1}^{n}p(\mathbf{b}_{i}|\mathbf{D,A}) \\ \mathbf{b}_{i}|\mathbf{A,D} & \sim N(\mathbf{m}_{i}, d_{ii}\mathbf{M}_i), \end{split} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{split} p(\mathbf{B|A,D}) & = \prod _{i=1}^{n}p(\mathbf{b}_{i}|\mathbf{D,A}) \\ \mathbf{b}_{i}|\mathbf{A,D} & \sim N(\mathbf{m}_{i}, d_{ii}\mathbf{M}_i), \end{split} \end{equation}

with

![]() $N(\mu ,\Sigma )$

representing the multivariate normal density function with the location and scale parameters

$N(\mu ,\Sigma )$

representing the multivariate normal density function with the location and scale parameters

![]() $\mu$

and

$\mu$

and

![]() $\Sigma$

.

$\Sigma$

.

Last, we set the prior for the contemporaneous relations matrix

![]() $p(\mathbf{A})$

. By design, it should reflect the economic structure of the analyzed economic system. We will discuss in detail our approach towards eliciting

$p(\mathbf{A})$

. By design, it should reflect the economic structure of the analyzed economic system. We will discuss in detail our approach towards eliciting

![]() $p(\mathbf{A})$

in Section 4.

$p(\mathbf{A})$

in Section 4.

Posterior. We turn to explaining how observations collected within

![]() $\mathbf{Y}_{T}$

,

$\mathbf{Y}_{T}$

,

![]() $\mathbf{Y}_{T}=(\mathbf{y}_1',\mathbf{y}_2',\ldots , \mathbf{y}_T')'$

affect our prior beliefs about unknown parameters

$\mathbf{Y}_{T}=(\mathbf{y}_1',\mathbf{y}_2',\ldots , \mathbf{y}_T')'$

affect our prior beliefs about unknown parameters

![]() $\mathbf{A, B}$

and

$\mathbf{A, B}$

and

![]() $\mathbf{D}$

. We follow Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2019) and divide the full sample into

$\mathbf{D}$

. We follow Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2019) and divide the full sample into

![]() $T_1$

initial observations, labeled pre-sample, and

$T_1$

initial observations, labeled pre-sample, and

![]() $T_2$

last observations, labeled as the main sample, with

$T_2$

last observations, labeled as the main sample, with

![]() $T_1+T_2=T$

. In this way we downweight the impact of pre-sample observations on the posterior by a factor

$T_1+T_2=T$

. In this way we downweight the impact of pre-sample observations on the posterior by a factor

![]() $0\leq \mu \leq 1$

. In order to derive the posterior distribution, it is decomposed into three parts:

$0\leq \mu \leq 1$

. In order to derive the posterior distribution, it is decomposed into three parts:

The posterior of

![]() $\mathbf{A}$

is estimated using a Metropolis-Hastings algorithm with

$\mathbf{A}$

is estimated using a Metropolis-Hastings algorithm with

![]() $M$

draws from the posterior distribution after initial

$M$

draws from the posterior distribution after initial

![]() $M^{*}$

burn-in draws (

$M^{*}$

burn-in draws (

![]() $M=M^{*}=5e5$

), while the posteriors of

$M=M^{*}=5e5$

), while the posteriors of

![]() $\mathbf{B}$

and

$\mathbf{B}$

and

![]() $\mathbf{D}$

are their respective natural conjugates.

$\mathbf{D}$

are their respective natural conjugates.

First we present the equations for the contemporaneous relations matrix posterior,

![]() $p(\mathbf{A|Y}_T)$

, using the covariance matrices of the VAR model residuals estimated for the two subsamples, as well as their weighted average. The posterior marginal distribution for

$p(\mathbf{A|Y}_T)$

, using the covariance matrices of the VAR model residuals estimated for the two subsamples, as well as their weighted average. The posterior marginal distribution for

![]() $\mathbf{A}$

is:

$\mathbf{A}$

is:

\begin{equation} p(\mathbf{A|Y}_T) = k_T p(\mathbf{A}) \left [ \det (\mathbf{A}\mathbf{\widetilde {\Omega }}_T\mathbf{A}') \right ]^{T^{*}} \prod _{i=1}^{n} \frac {\left [\tau _i(\mathbf{A})\right ]^{\kappa _i}}{\left [\tau _i^{*}(\mathbf{A})/ T^{*}\right ]^{\kappa _i^{*}}}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} p(\mathbf{A|Y}_T) = k_T p(\mathbf{A}) \left [ \det (\mathbf{A}\mathbf{\widetilde {\Omega }}_T\mathbf{A}') \right ]^{T^{*}} \prod _{i=1}^{n} \frac {\left [\tau _i(\mathbf{A})\right ]^{\kappa _i}}{\left [\tau _i^{*}(\mathbf{A})/ T^{*}\right ]^{\kappa _i^{*}}}, \end{equation}

with

![]() $T^{*} = (\mu T_1 + T_2)/2$

and

$T^{*} = (\mu T_1 + T_2)/2$

and

![]() $k_T$

a constant, ensuring that

$k_T$

a constant, ensuring that

![]() $p(\mathbf{A|Y}_T)$

is a proper density function that integrates to unity.

$p(\mathbf{A|Y}_T)$

is a proper density function that integrates to unity.

Next, the posterior for the covariance matrix,

![]() $p(\mathbf{D|A,Y}_{T})$

, is expressed as a product of the posterior for its diagonal elements:

$p(\mathbf{D|A,Y}_{T})$

, is expressed as a product of the posterior for its diagonal elements:

\begin{equation} \begin{split} p(\mathbf{D|A,Y}_T) & = \prod _{i=1}^{n}p(d_{ii}|\mathbf{A,Y}_T) \\ d_{ii}^{-1}|\mathbf{A,Y}_T & \sim \Gamma (\kappa _i^{*},\tau _i^{*}(\mathbf{A})). \end{split} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{split} p(\mathbf{D|A,Y}_T) & = \prod _{i=1}^{n}p(d_{ii}|\mathbf{A,Y}_T) \\ d_{ii}^{-1}|\mathbf{A,Y}_T & \sim \Gamma (\kappa _i^{*},\tau _i^{*}(\mathbf{A})). \end{split} \end{equation}

The posterior for the matrix of parameters of the lagged variables,

![]() $p(\mathbf{B|A,D,Y}_T)$

, is written as the product of the posterior for its individual rows:

$p(\mathbf{B|A,D,Y}_T)$

, is written as the product of the posterior for its individual rows:

\begin{equation} \begin{split} p(\mathbf{B|A,D,Y}_T) & = \prod _{i=1}^{n}p(\mathbf{b}_{i}|\mathbf{D,A,Y}_T) \\ \mathbf{b}_{i}|\mathbf{A,D,Y}_T & \sim N(\mathbf{m}_{i}^{*}(\mathbf{A}), d_{ii}\mathbf{M}_i^{*}). \end{split} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{split} p(\mathbf{B|A,D,Y}_T) & = \prod _{i=1}^{n}p(\mathbf{b}_{i}|\mathbf{D,A,Y}_T) \\ \mathbf{b}_{i}|\mathbf{A,D,Y}_T & \sim N(\mathbf{m}_{i}^{*}(\mathbf{A}), d_{ii}\mathbf{M}_i^{*}). \end{split} \end{equation}

Let

\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{\widetilde {\Omega }}_1 & = (T_1)^{-1} \left ( \sum _{t=1}^{T_1} \mathbf{y}_t \mathbf{y}_t' - \left (\sum _{t=1}^{T_1} \mathbf{y}_t \mathbf{x}_{t-1}'\right ) \left (\sum _{t=1}^{T_1} \mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mathbf{x}_{t-1}'\right )^{-1} \left (\sum _{t=1}^{T_1} \mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mathbf{y}_t'\right ) \right ) \\ \mathbf{\widetilde {\Omega }}_2 & = (T_2)^{-1} \left ( \sum _{t=T_1+1}^{T} \mathbf{y}_t \mathbf{y}_t' - \left (\sum _{t=T_1+1}^{T} \mathbf{y}_t \mathbf{x}_{t-1}'\right ) \left (\sum _{t=T_1+1}^{T} \mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mathbf{x}_{t-1}'\right )^{-1} \left (\sum _{t=T_1+1}^{T} \mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mathbf{y}_t'\right ) \right )\\ \mathbf{\widetilde {\Omega }}_T & = (\mu T_1 + T_2)^{-1}\left (\mu T_1 \mathbf{\widetilde {\Omega }}_1 + T_2 \mathbf{\widetilde {\Omega }}_2 \right ) \end{split} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{\widetilde {\Omega }}_1 & = (T_1)^{-1} \left ( \sum _{t=1}^{T_1} \mathbf{y}_t \mathbf{y}_t' - \left (\sum _{t=1}^{T_1} \mathbf{y}_t \mathbf{x}_{t-1}'\right ) \left (\sum _{t=1}^{T_1} \mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mathbf{x}_{t-1}'\right )^{-1} \left (\sum _{t=1}^{T_1} \mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mathbf{y}_t'\right ) \right ) \\ \mathbf{\widetilde {\Omega }}_2 & = (T_2)^{-1} \left ( \sum _{t=T_1+1}^{T} \mathbf{y}_t \mathbf{y}_t' - \left (\sum _{t=T_1+1}^{T} \mathbf{y}_t \mathbf{x}_{t-1}'\right ) \left (\sum _{t=T_1+1}^{T} \mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mathbf{x}_{t-1}'\right )^{-1} \left (\sum _{t=T_1+1}^{T} \mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mathbf{y}_t'\right ) \right )\\ \mathbf{\widetilde {\Omega }}_T & = (\mu T_1 + T_2)^{-1}\left (\mu T_1 \mathbf{\widetilde {\Omega }}_1 + T_2 \mathbf{\widetilde {\Omega }}_2 \right ) \end{split} \end{equation}

![]() $\zeta _i^{*}(\mathbf{A}) = \left (\widetilde {\mathbf{Y}}_i'(\mathbf{A})\widetilde {\mathbf{Y}}_i(\mathbf{A})\right ) - \left (\widetilde {\mathbf{Y}}_i'(\mathbf{A})\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i\right ) \left (\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i'\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i\right )^{-1} \left (\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i'\widetilde {\mathbf{Y}}_i(\mathbf{A})\right )$

represents the sum of squared residuals from a regression of

$\zeta _i^{*}(\mathbf{A}) = \left (\widetilde {\mathbf{Y}}_i'(\mathbf{A})\widetilde {\mathbf{Y}}_i(\mathbf{A})\right ) - \left (\widetilde {\mathbf{Y}}_i'(\mathbf{A})\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i\right ) \left (\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i'\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i\right )^{-1} \left (\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i'\widetilde {\mathbf{Y}}_i(\mathbf{A})\right )$

represents the sum of squared residuals from a regression of

![]() $\widetilde {\mathbf{Y}}_i(\mathbf{A})$

on

$\widetilde {\mathbf{Y}}_i(\mathbf{A})$

on

![]() $\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i$

:

$\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i$

:

\begin{equation} \begin{split} \underset {(T+k)\times 1}{\widetilde {\mathbf{Y}}_i(\mathbf{A})} & = \begin{bmatrix} \sqrt {\mu } \mathbf{y}_1'\mathbf{a}_i & \ldots & \sqrt {\mu } \mathbf{y}_{T_1}'\mathbf{a}_i & \mathbf{y}_{T_1+1}'\mathbf{a}_i & \ldots & \mathbf{y}_{T}'\mathbf{a}_i & \mathbf{m}_{i}'\mathbf{P}_i \end{bmatrix}'\\ \underset {(T+k)\times k}{\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i} & = \begin{bmatrix}\sqrt {\mu } \mathbf{x}_0 & \ldots & \sqrt {\mu } \mathbf{x}_{T_1-1}' & \mathbf{x}_{T_1}' & \ldots & \mathbf{x}_{T-1}' & \mathbf{P}_i \end{bmatrix}' \end{split} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{split} \underset {(T+k)\times 1}{\widetilde {\mathbf{Y}}_i(\mathbf{A})} & = \begin{bmatrix} \sqrt {\mu } \mathbf{y}_1'\mathbf{a}_i & \ldots & \sqrt {\mu } \mathbf{y}_{T_1}'\mathbf{a}_i & \mathbf{y}_{T_1+1}'\mathbf{a}_i & \ldots & \mathbf{y}_{T}'\mathbf{a}_i & \mathbf{m}_{i}'\mathbf{P}_i \end{bmatrix}'\\ \underset {(T+k)\times k}{\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i} & = \begin{bmatrix}\sqrt {\mu } \mathbf{x}_0 & \ldots & \sqrt {\mu } \mathbf{x}_{T_1-1}' & \mathbf{x}_{T_1}' & \ldots & \mathbf{x}_{T-1}' & \mathbf{P}_i \end{bmatrix}' \end{split} \end{equation}

![]() $\mathbf{P}_i$

is the Cholesky factor of

$\mathbf{P}_i$

is the Cholesky factor of

![]() $\mathbf{M}_i^{-1} = \mathbf{P}_i\mathbf{P}_i'$

, and

$\mathbf{M}_i^{-1} = \mathbf{P}_i\mathbf{P}_i'$

, and

\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{m_i^{*}}(\mathbf{A}) & = \left (\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i'\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i\right )^{-1} \left (\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i'\widetilde {\mathbf{Y}}_i(\mathbf{A})\right ) \\ \mathbf{M_i^{*}} & = \left (\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i'\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i\right )^{-1}. \end{split} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{m_i^{*}}(\mathbf{A}) & = \left (\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i'\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i\right )^{-1} \left (\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i'\widetilde {\mathbf{Y}}_i(\mathbf{A})\right ) \\ \mathbf{M_i^{*}} & = \left (\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i'\widetilde {\mathbf{X}}_i\right )^{-1}. \end{split} \end{equation}

4. The data and the empirical model

We describe the structural fiscal SVAR model that we apply to the U.S. economy. The choice of endogenous variables entering vector

![]() $\mathbf{y_t}$

is based on the setup considered by Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017), whereas the prior information is elicited based on the survey of the literature on fiscal elasticities provided in Section 2. In what follows, we discuss both the data and the setup of our empirical model in more detail.

$\mathbf{y_t}$

is based on the setup considered by Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017), whereas the prior information is elicited based on the survey of the literature on fiscal elasticities provided in Section 2. In what follows, we discuss both the data and the setup of our empirical model in more detail.

4.1 Data

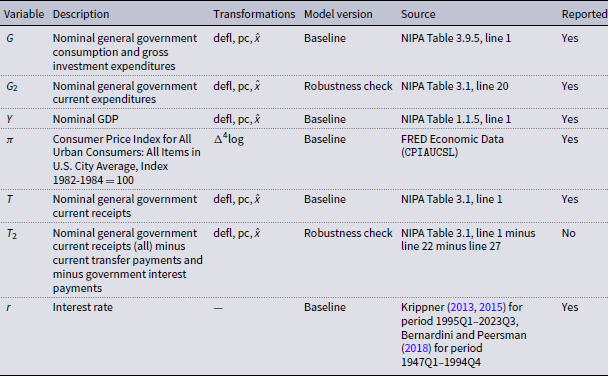

In our baseline specification we consider the joint dynamics of five U.S. variables: real general government consumption and gross investment expenditures (

![]() $G_t$

), real GDP (

$G_t$

), real GDP (

![]() $Y_t$

), inflation (

$Y_t$

), inflation (

![]() $\pi _t$

), real general government tax receipts (

$\pi _t$

), real general government tax receipts (

![]() $T_t$

), and the interest rate (

$T_t$

), and the interest rate (

![]() $r_t$

) (for details see Table A1). We take

$r_t$

) (for details see Table A1). We take

![]() $G_t$

,

$G_t$

,

![]() $Y_t$

and

$Y_t$

and

![]() $T_t$

in nominal, seasonally adjusted values from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis’s National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) tables, deflate all the series with the implicit price deflator for GDP and express them in per capita terms. Next, we log the series

$T_t$

in nominal, seasonally adjusted values from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis’s National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) tables, deflate all the series with the implicit price deflator for GDP and express them in per capita terms. Next, we log the series

![]() $G_t$

,

$G_t$

,

![]() $Y_t$

,

$Y_t$

,

![]() $T_t$

and extract cycle estimates using the modified Beveridge-Nelson filter of Kamber et al. (Reference Kamber, Morley and Wong2025).Footnote

5

In regards to the proxy for inflation,

$T_t$

and extract cycle estimates using the modified Beveridge-Nelson filter of Kamber et al. (Reference Kamber, Morley and Wong2025).Footnote

5

In regards to the proxy for inflation,

![]() $\pi _t$

, we source the CPI index from the FRED database and compute the year-on-year log rate of change. With respect to

$\pi _t$

, we source the CPI index from the FRED database and compute the year-on-year log rate of change. With respect to

![]() $r_t$

, we construct a series based on data from Bernardini and Peersman (Reference Bernardini and Peersman2018) and estimates of the shadow rate from Krippner (Reference Krippner2013, Reference Krippner2015) for periods when the interest rate is near the zero lower bound. Consequently, the vector of endogenous variables is:

$r_t$

, we construct a series based on data from Bernardini and Peersman (Reference Bernardini and Peersman2018) and estimates of the shadow rate from Krippner (Reference Krippner2013, Reference Krippner2015) for periods when the interest rate is near the zero lower bound. Consequently, the vector of endogenous variables is:

where

![]() $\hat {x}$

indicates the cyclical deviation of variable

$\hat {x}$

indicates the cyclical deviation of variable

![]() $x$

from its stochastic trend estimate. All variables entering

$x$

from its stochastic trend estimate. All variables entering

![]() $\mathbf{y}_t$

are expressed in percent. Appendix A provides detailed sources of our data and lists all transformations.

$\mathbf{y}_t$

are expressed in percent. Appendix A provides detailed sources of our data and lists all transformations.

Our sample covers quarterly data from the period 1949Q4–2024Q3.Footnote

6

For the sake of our analysis, we divide the sample into two subperiods. In our setup, the initial

![]() $T_1=149$

observations for the period 1949Q4–1986Q4 are treated as pre-sample observations. This choice is motivated by the fact that the output elasticity of tax revenues has increased after the Tax Reform Act of 1986, according to the studies of Mertens and Ravn (Reference Mertens and Ravn2014) or Follette and Lutz (Reference Follette and Lutz2010).Footnote

7

For the above reasons, the information from this period is downweighted by a factor of 2 (

$T_1=149$

observations for the period 1949Q4–1986Q4 are treated as pre-sample observations. This choice is motivated by the fact that the output elasticity of tax revenues has increased after the Tax Reform Act of 1986, according to the studies of Mertens and Ravn (Reference Mertens and Ravn2014) or Follette and Lutz (Reference Follette and Lutz2010).Footnote

7

For the above reasons, the information from this period is downweighted by a factor of 2 (

![]() $\mu =0.5$

). The subsequent

$\mu =0.5$

). The subsequent

![]() $T_2=151$

observations for the period 1987Q1–2024Q3 are treated as the main sample. Given quarterly data, we set the maximum lag at

$T_2=151$

observations for the period 1987Q1–2024Q3 are treated as the main sample. Given quarterly data, we set the maximum lag at

![]() $m=4$

, which is a frequent choice in the literature (e.g., Mertens and Ravn, Reference Mertens and Ravn2014).Footnote

8

$m=4$

, which is a frequent choice in the literature (e.g., Mertens and Ravn, Reference Mertens and Ravn2014).Footnote

8

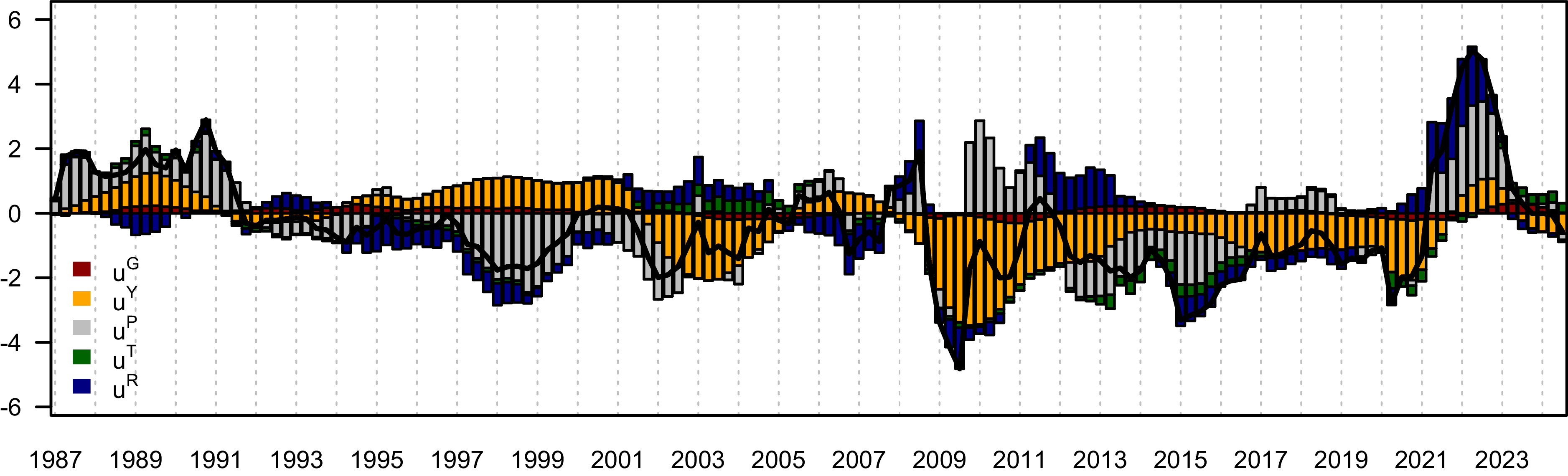

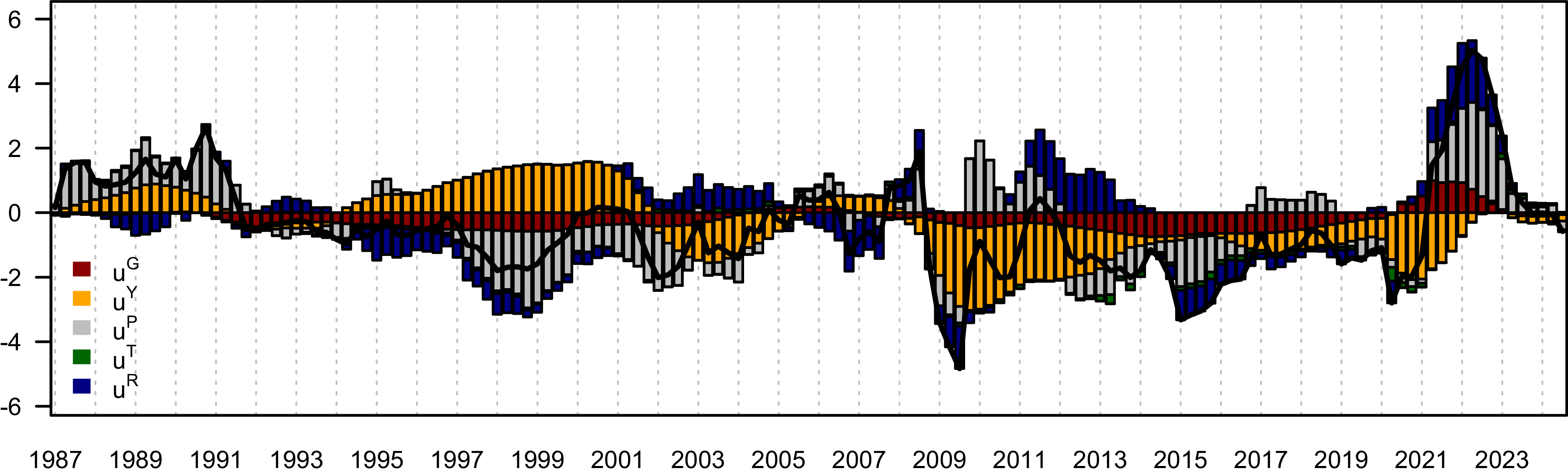

Figure 1 illustrates time series for the dependent variables. Several observations follow. There is a strong cyclical pattern in both real general government consumption and gross investment expenditure,

![]() $\hat {g}_t$

, and in real general government tax receipts,

$\hat {g}_t$

, and in real general government tax receipts,

![]() $\hat {t}_t$

. Moreover, the patterns for both of these variables change markedly in the early 1950s. We note also that

$\hat {t}_t$

. Moreover, the patterns for both of these variables change markedly in the early 1950s. We note also that

![]() $\hat {t}_t$

is much more strongly correlated with

$\hat {t}_t$

is much more strongly correlated with

![]() $\hat {y}_t$

than

$\hat {y}_t$

than

![]() $\hat {g}_t$

, indicating an obvious link in the cyclicality of tax receipts to the tax base. In regards to

$\hat {g}_t$

, indicating an obvious link in the cyclicality of tax receipts to the tax base. In regards to

![]() $\hat {y}_t$

, we observe several downturns, most recently related to the global financial crisis and the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. We explore this issue further in section 6. Next, apart from several high inflation episodes (related to the removal of price controls, supply constraints and pent-up demand after World World II, oil shocks in the 1970s, and most recently the Covid-19 pandemic), the year-on-year inflation rate,

$\hat {y}_t$

, we observe several downturns, most recently related to the global financial crisis and the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. We explore this issue further in section 6. Next, apart from several high inflation episodes (related to the removal of price controls, supply constraints and pent-up demand after World World II, oil shocks in the 1970s, and most recently the Covid-19 pandemic), the year-on-year inflation rate,

![]() $\pi _t$

, evolves otherwise on a moderate level. Finally, following its peak in the 1980s, the nominal (shadow) interest rate decreased substantially and became negative after the global financial crisis and during the Covid-19 pandemic. By the end of the sample, along with a stark increase in inflation, the interest rate picked up considerably and moved away from its zero lower bound.

$\pi _t$

, evolves otherwise on a moderate level. Finally, following its peak in the 1980s, the nominal (shadow) interest rate decreased substantially and became negative after the global financial crisis and during the Covid-19 pandemic. By the end of the sample, along with a stark increase in inflation, the interest rate picked up considerably and moved away from its zero lower bound.

Figure 1. Time series for the endogenous variables.

Notes: The figure presents the endogenous variables used in the baseline model. For variable definitions and their transformations the reader is referred to Section 4.1.

4.2 Specification of the structural VAR model

The structure of contemporaneous relations among the endogenous variables is assumed to be as follows:

In the notation of equation (1) for the structural VAR model, the above system implies the following representation for matrix

![]() $\mathbf{A}$

:

$\mathbf{A}$

:

\begin{equation} \mathbf{A}= \begin{bmatrix} 1 &-\alpha _{gy} &-\alpha _{gp} &-\alpha _{gt} &-\alpha _{gr}\\ -\alpha _{yg} &1 &-\alpha _{yp} &-\alpha _{yt} &-\alpha _{yr}\\ -\alpha _{pg} &-\alpha _{py} &1 &-\alpha _{pt} &-\alpha _{pr}\\ -\alpha _{tg} &-\alpha _{ty} &-\alpha _{tp} &1 &-\alpha _{tr}\\ -\alpha _{rg} &-\alpha _{ry} &-\alpha _{rp} &-\alpha _{rt} &1 \end{bmatrix}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \mathbf{A}= \begin{bmatrix} 1 &-\alpha _{gy} &-\alpha _{gp} &-\alpha _{gt} &-\alpha _{gr}\\ -\alpha _{yg} &1 &-\alpha _{yp} &-\alpha _{yt} &-\alpha _{yr}\\ -\alpha _{pg} &-\alpha _{py} &1 &-\alpha _{pt} &-\alpha _{pr}\\ -\alpha _{tg} &-\alpha _{ty} &-\alpha _{tp} &1 &-\alpha _{tr}\\ -\alpha _{rg} &-\alpha _{ry} &-\alpha _{rp} &-\alpha _{rt} &1 \end{bmatrix}. \end{equation}

Below we discuss equations (14)–(18) and explain the most important short-term elasticities. Equation (14) can be interpreted as the government spending rule, where

![]() $\alpha _{gy}$

is the output elasticity of government spending. Equation (15) describes the aggregate demand equation, where

$\alpha _{gy}$

is the output elasticity of government spending. Equation (15) describes the aggregate demand equation, where

![]() $\alpha _{yg}$

is the government spending elasticity of output. Equation (16) constitutes the short-term Phillips curve, where

$\alpha _{yg}$

is the government spending elasticity of output. Equation (16) constitutes the short-term Phillips curve, where

![]() $\alpha _{py}$

is the short term output elasticity of prices. Equation (17) is the tax rule with

$\alpha _{py}$

is the short term output elasticity of prices. Equation (17) is the tax rule with

![]() $\alpha _{ty}$

being the output elasticity of taxes, and

$\alpha _{ty}$

being the output elasticity of taxes, and

![]() $\alpha _{tp}$

being the price elasticity of taxes. Finally, the last equation, (18), can be interpreted as a short-term Taylor-type rule, where

$\alpha _{tp}$

being the price elasticity of taxes. Finally, the last equation, (18), can be interpreted as a short-term Taylor-type rule, where

![]() $\alpha _{ry}$

is the output elasticity of the interest rate and

$\alpha _{ry}$

is the output elasticity of the interest rate and

![]() $\alpha _{rp}$

is the price elasticity of the interest rate. We discuss the choice for the prior for the elasticities in equations (14)–(18) in the next section.

$\alpha _{rp}$

is the price elasticity of the interest rate. We discuss the choice for the prior for the elasticities in equations (14)–(18) in the next section.

Our system of equations implies that all endogenous variables are allowed to be affected by their past values, included in the vector

![]() $\mathbf{x}_{t-1}$

. The dynamics of endogenous variables is also affected by five structural shocks. The first shock,

$\mathbf{x}_{t-1}$

. The dynamics of endogenous variables is also affected by five structural shocks. The first shock,

![]() $u_t^G$

, can be perceived as an unexpected change in general government consumption and investment expenditures, hence we label it spending shock. The income shock

$u_t^G$

, can be perceived as an unexpected change in general government consumption and investment expenditures, hence we label it spending shock. The income shock

![]() $u_t^Y$

reflects unexpected shifts in aggregate U.S. economic activity. The price shock,

$u_t^Y$

reflects unexpected shifts in aggregate U.S. economic activity. The price shock,

![]() $u_t^P$

, captures unanticipated changes to inflation. The fourth shock

$u_t^P$

, captures unanticipated changes to inflation. The fourth shock

![]() $u_t^T$

accounts for unexpected changes in general government tax receipts, hence we label it tax shock. Finally, we account for the interest rate shock,

$u_t^T$

accounts for unexpected changes in general government tax receipts, hence we label it tax shock. Finally, we account for the interest rate shock,

![]() $u_t^R$

, which reflects unanticipated changes in the monetary policy stance.

$u_t^R$

, which reflects unanticipated changes in the monetary policy stance.

4.3 The prior for the empirical model

Setting the prior distributions is of central importance for our model. In this subsection we describe our choices related to the parameters describing

![]() $p(\mathbf{A,B,D})$

for the empirical model.

$p(\mathbf{A,B,D})$

for the empirical model.

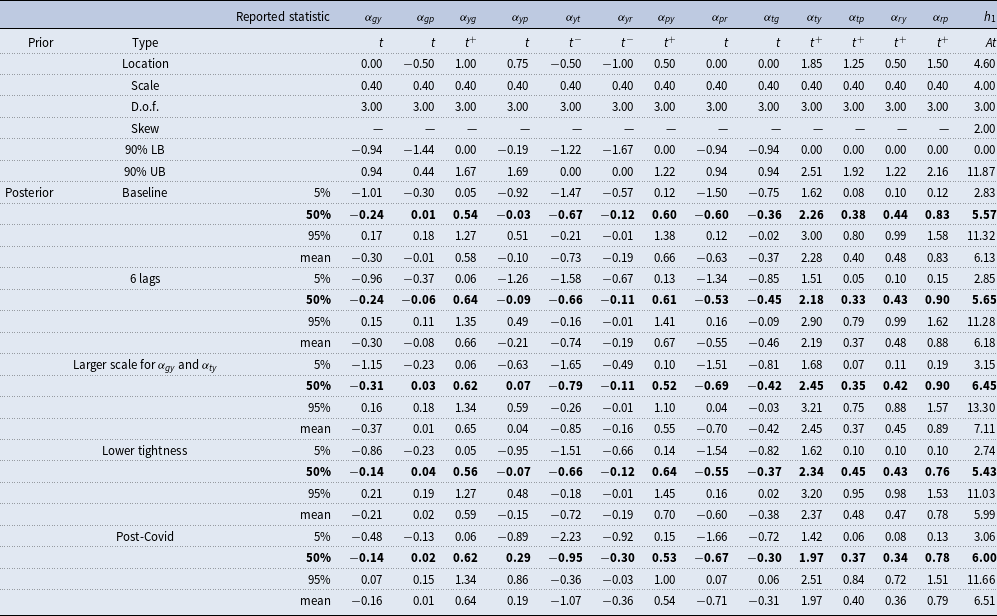

Table 1. Priors and posteriors for contemporeaneous relations matrix

![]() $\textbf{A}$

$\textbf{A}$

Notes: In the table

![]() $t$

denotes a Student t distribution and

$t$

denotes a Student t distribution and

![]() $At$

denotes an asymmetric Student t distribution proposed by Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2018). Signs

$At$

denotes an asymmetric Student t distribution proposed by Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2018). Signs

![]() $+$

and

$+$

and

![]() $-$

indicate that the distribution is truncated to be either positive or negative, respectively. D.o.f stands for degrees of freedom for each distribution. 90% LB and UB denote the lower and upper bounds for the confidence intervals (for truncated distributions, one-sided confidence sets are reported). For the posterior distributions the coefficients for the 5th percentile, the median, the 95th percentile and the mean are reported.

$-$

indicate that the distribution is truncated to be either positive or negative, respectively. D.o.f stands for degrees of freedom for each distribution. 90% LB and UB denote the lower and upper bounds for the confidence intervals (for truncated distributions, one-sided confidence sets are reported). For the posterior distributions the coefficients for the 5th percentile, the median, the 95th percentile and the mean are reported.

Prior for

![]() $\mathbf{A}$

. We start by describing our choices for the contemporaneous relations matrix prior,

$\mathbf{A}$

. We start by describing our choices for the contemporaneous relations matrix prior,

![]() $p(\mathbf{A})$

. The choices are summarized in the upper part of Table 1. We have chosen to use either symmetric or truncated Student t distributions for the elements of the

$p(\mathbf{A})$

. The choices are summarized in the upper part of Table 1. We have chosen to use either symmetric or truncated Student t distributions for the elements of the

![]() $\mathbf{A}$

matrix or restrict them to zero or one. We follow Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2018) for the monetary policy part of the system and introduce additional structure on the fiscal side. In the baseline specification we set all prior scale parameters to

$\mathbf{A}$

matrix or restrict them to zero or one. We follow Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2018) for the monetary policy part of the system and introduce additional structure on the fiscal side. In the baseline specification we set all prior scale parameters to

![]() $0.4$

as they do.

$0.4$

as they do.

First we discuss the government spending rule. The output elasticity of government spending (

![]() $\alpha _{gy}$

) is centered around 0, following Favero and Giavazzi (Reference Favero and Giavazzi2012). A scale parameter equal to

$\alpha _{gy}$

) is centered around 0, following Favero and Giavazzi (Reference Favero and Giavazzi2012). A scale parameter equal to

![]() $0.4$

implies the confidence interval is

$0.4$

implies the confidence interval is

![]() $(-0.94,0.94)$

. Because evidence on the

$(-0.94,0.94)$

. Because evidence on the

![]() $\alpha _{gy}$

value in the literature is sparse, we also test a scale parameter equal to

$\alpha _{gy}$

value in the literature is sparse, we also test a scale parameter equal to

![]() $0.6$

in one of the robustness checks. Further, we restrict

$0.6$

in one of the robustness checks. Further, we restrict

![]() $\alpha _{gt}$

and

$\alpha _{gt}$

and

![]() $\alpha _{gr}$

to zero. This is mostly motivated by the discussion in Blanchard and Perotti (Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002), who explain that it typically takes longer than a quarter for discretionary fiscal policy to react to news at the quarterly frequency. In addition, Favero and Giavazzi (Reference Favero and Giavazzi2012) use as well zero values for

$\alpha _{gr}$

to zero. This is mostly motivated by the discussion in Blanchard and Perotti (Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002), who explain that it typically takes longer than a quarter for discretionary fiscal policy to react to news at the quarterly frequency. In addition, Favero and Giavazzi (Reference Favero and Giavazzi2012) use as well zero values for

![]() $\alpha _{gt}$

and

$\alpha _{gt}$

and

![]() $\alpha _{gr}$

. It is important to underline that, concerning the output and interest rate elasticities of public spending, our definition of spending does not include unemployment benefits and interest payments, but instead focuses on government purchases of goods and services. In regards to the price elasticity of public spending

$\alpha _{gr}$

. It is important to underline that, concerning the output and interest rate elasticities of public spending, our definition of spending does not include unemployment benefits and interest payments, but instead focuses on government purchases of goods and services. In regards to the price elasticity of public spending

![]() $\alpha _{gp}$

we center the prior at

$\alpha _{gp}$

we center the prior at

![]() $-0.5$

following, among others, Perotti (Reference Perotti and Perotti2008) and Favero and Giavazzi (Reference Favero and Giavazzi2012). The estimate is based on dividing spending into a non-wage and a wage components, where the non-wage component is indexed to the price level and the wage component shrinks proportionally to inflation.

$-0.5$

following, among others, Perotti (Reference Perotti and Perotti2008) and Favero and Giavazzi (Reference Favero and Giavazzi2012). The estimate is based on dividing spending into a non-wage and a wage components, where the non-wage component is indexed to the price level and the wage component shrinks proportionally to inflation.

Second, we discuss the aggregate demand curve. Blanchard and Perotti (Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002, Table II, p. 1342) estimate an impact government spending multiplier of 0.96 and 0.99 in their deterministic and stochastic trend specifications, respectively. Moreover, Hall (Reference Hall2009) similarly argues for a value of approximately 1. Consequently, we center the prior for

![]() $\alpha _{yg}$

at 1. The scale parameter, set at

$\alpha _{yg}$

at 1. The scale parameter, set at

![]() $0.4$

, resembles moderate uncertainty around our mode. In regards to

$0.4$

, resembles moderate uncertainty around our mode. In regards to

![]() $\alpha _{yt}$

we assume the prior mode is

$\alpha _{yt}$

we assume the prior mode is

![]() $-0.5$

. The assumed signs for

$-0.5$

. The assumed signs for

![]() $\alpha _{yg}$

and

$\alpha _{yg}$

and

![]() $\alpha _{yt}$

, imposed by using a truncated t distribution, are in accordance with Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2008) and Mertens and Ravn (Reference Mertens and Ravn2014). Hence, our one-sided 90% confidence interval for

$\alpha _{yt}$

, imposed by using a truncated t distribution, are in accordance with Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2008) and Mertens and Ravn (Reference Mertens and Ravn2014). Hence, our one-sided 90% confidence interval for

![]() $\alpha _{yg}$

is

$\alpha _{yg}$

is

![]() $(0.00, 1.67)$

and for

$(0.00, 1.67)$

and for

![]() $\alpha _{yt}$

it is

$\alpha _{yt}$

it is

![]() $(-1.22, 0.00)$

, in line with the elasticity range reported in those studies. We follow Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2018) and set our prior beliefs for

$(-1.22, 0.00)$

, in line with the elasticity range reported in those studies. We follow Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2018) and set our prior beliefs for

![]() $\alpha _{yp}$

as a symmetric Student t distribution centered at

$\alpha _{yp}$

as a symmetric Student t distribution centered at

![]() $0.75$

and for

$0.75$

and for

![]() $\alpha _{yr}$

as truncated Student t distribution with mode at

$\alpha _{yr}$

as truncated Student t distribution with mode at

![]() $-1$

.

$-1$

.

Third, we move to the aggregate supply (Phillips) curve. We use a Student t distribution for

![]() $\alpha _{py}$

, truncated to be positive, with the mode at

$\alpha _{py}$

, truncated to be positive, with the mode at

![]() $0.50$

and the scale parameter at

$0.50$

and the scale parameter at

![]() $0.4$

, which is in line with Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2018). The corresponding one-sided

$0.4$

, which is in line with Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2018). The corresponding one-sided

![]() $90\%$

prior confidence interval

$90\%$

prior confidence interval

![]() $(0.00, 1.20)$

includes also mean estimates from Gagliardone et al. (Reference Gagliardone, Gertler, Lenzu and Tielens2023), Hazell et al. (Reference Hazell, Herreño, Nakamura and Steinsson2022) and Gali and Gertler (Reference Gali and Gertler1999). In turn

$(0.00, 1.20)$

includes also mean estimates from Gagliardone et al. (Reference Gagliardone, Gertler, Lenzu and Tielens2023), Hazell et al. (Reference Hazell, Herreño, Nakamura and Steinsson2022) and Gali and Gertler (Reference Gali and Gertler1999). In turn

![]() $\alpha _{pg}$

and

$\alpha _{pg}$

and

![]() $\alpha _{pt}$

are restricted to zero, so we limit the possibility of fiscal variables affecting inflation on impact. Additionally, we do not have any prior beliefs for

$\alpha _{pt}$

are restricted to zero, so we limit the possibility of fiscal variables affecting inflation on impact. Additionally, we do not have any prior beliefs for

![]() $\alpha _{pr}$

and use a symmetric Student t distributions centered at 0 and set the scale parameter to 0.4.

$\alpha _{pr}$

and use a symmetric Student t distributions centered at 0 and set the scale parameter to 0.4.

Fourth, we look at the tax rule equation. We base our prior beliefs mostly on previous estimates by Perotti (Reference Perotti and Perotti2008), Favero and Giavazzi (Reference Favero and Giavazzi2012), and Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2008). Therefore, our prior belief for

![]() $\alpha _{ty}$

is represented by a Student t distribution, truncated to be positive, with the mode set at

$\alpha _{ty}$

is represented by a Student t distribution, truncated to be positive, with the mode set at

![]() $1.85$

and confidence interval

$1.85$

and confidence interval

![]() $(0.00, 2.51)$

. Favero and Giavazzi (Reference Favero and Giavazzi2012) report updated elasticities for Blanchard and Perotti (Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002), following calculations in Perotti (Reference Perotti and Perotti2008), and use this value. For

$(0.00, 2.51)$

. Favero and Giavazzi (Reference Favero and Giavazzi2012) report updated elasticities for Blanchard and Perotti (Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002), following calculations in Perotti (Reference Perotti and Perotti2008), and use this value. For

![]() $\alpha _{tp}$

, we employ the same distribution, but we set the mode at

$\alpha _{tp}$

, we employ the same distribution, but we set the mode at

![]() $1.25$

, as in Favero and Giavazzi’s (Reference Favero and Giavazzi2012) update, and the one-sided

$1.25$

, as in Favero and Giavazzi’s (Reference Favero and Giavazzi2012) update, and the one-sided

![]() $90\%$

confidence interval to

$90\%$

confidence interval to

![]() $(0.00, 1.92)$

. For

$(0.00, 1.92)$

. For

![]() $\alpha _{tg}$

, we use a rather uninformative, symmetric Student t distribution with mean at

$\alpha _{tg}$

, we use a rather uninformative, symmetric Student t distribution with mean at

![]() $0.0$

and scale parameter at

$0.0$

and scale parameter at

![]() $0.4$

. Thus we assume that the level of government spending may instantaneously affect the level of tax revenues, but not the other way around, in line with Favero and Giavazzi (Reference Favero and Giavazzi2012).

$0.4$

. Thus we assume that the level of government spending may instantaneously affect the level of tax revenues, but not the other way around, in line with Favero and Giavazzi (Reference Favero and Giavazzi2012).

Finally, for the Taylor-type (monetary policy) rule, we follow Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2018) and use a Student t distribution truncated to be positive for

![]() $\alpha _{ry}$

and

$\alpha _{ry}$

and

![]() $\alpha _{rp}$

. The means are set in accordance with Taylor (Reference Taylor1993) and Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2018) at

$\alpha _{rp}$

. The means are set in accordance with Taylor (Reference Taylor1993) and Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2018) at

![]() $0.5$

and

$0.5$

and

![]() $1.5$

, respectively, while the scale parameter is equal to

$1.5$

, respectively, while the scale parameter is equal to

![]() $0.4$

in each case. In regards to the remaining elasticities,

$0.4$

in each case. In regards to the remaining elasticities,

![]() $\alpha _{rg}$

and

$\alpha _{rg}$

and

![]() $\alpha _{rt}$

are restricted to zero to resemble our beliefs that monetary policy does not respond to changes in fiscal policy, at least on impact.

$\alpha _{rt}$

are restricted to zero to resemble our beliefs that monetary policy does not respond to changes in fiscal policy, at least on impact.

Taking into account the above considerations, we set the prior for the individual parameters of

![]() $\mathbf{A}$

as follows:

$\mathbf{A}$

as follows:

\begin{equation} \begin{matrix} & \alpha _{gy}\sim t_3(0.00,0.40) \quad \alpha _{gp}\sim t_3(-0.50,0.40) \quad \alpha _{yg}\sim t_3^+(1.00,0.40) \quad \alpha _{yp}\sim t_3(0.75,0.40) \\& \alpha _{yt}\sim t_3^-(-0.50,0.40)\quad \alpha _{yr}\sim t_3^-(0.00,0.40)\quad \alpha _{py}\sim t_3^+(0.50,0.40) \quad \alpha _{pr}\sim t_3(0.00,0.40)\\ & \alpha _{tg}\sim t_3(0.00,0.40)\quad \alpha _{ty}\sim t_3^+(1.85,0.40)\quad \alpha _{tp}\sim t_3^+(1.25,0.40) \quad \alpha _{ry}\sim t_3^+(0.50,0.40)\\& \alpha _{rp}\sim t_3^+(1.50,0.40). \end{matrix} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{matrix} & \alpha _{gy}\sim t_3(0.00,0.40) \quad \alpha _{gp}\sim t_3(-0.50,0.40) \quad \alpha _{yg}\sim t_3^+(1.00,0.40) \quad \alpha _{yp}\sim t_3(0.75,0.40) \\& \alpha _{yt}\sim t_3^-(-0.50,0.40)\quad \alpha _{yr}\sim t_3^-(0.00,0.40)\quad \alpha _{py}\sim t_3^+(0.50,0.40) \quad \alpha _{pr}\sim t_3(0.00,0.40)\\ & \alpha _{tg}\sim t_3(0.00,0.40)\quad \alpha _{ty}\sim t_3^+(1.85,0.40)\quad \alpha _{tp}\sim t_3^+(1.25,0.40) \quad \alpha _{ry}\sim t_3^+(0.50,0.40)\\& \alpha _{rp}\sim t_3^+(1.50,0.40). \end{matrix} \end{equation}

where

![]() $x\sim t_v(c,\sigma )$

denotes that a variable

$x\sim t_v(c,\sigma )$

denotes that a variable

![]() $x$

follows the Student t distribution with mode

$x$

follows the Student t distribution with mode

![]() $c$

, scale parameter

$c$

, scale parameter

![]() $\sigma$

and

$\sigma$

and

![]() $v$

degrees of freedom, while superscripts “+” and “–” denote that the distribution is truncated to be either positive or negative, respectively. Our choice of

$v$

degrees of freedom, while superscripts “+” and “–” denote that the distribution is truncated to be either positive or negative, respectively. Our choice of

![]() $t_3$

distributions is the same as in Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2019). We summarize the choice of our priors that affect the contemporaneous coefficients in

$t_3$

distributions is the same as in Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2019). We summarize the choice of our priors that affect the contemporaneous coefficients in

![]() $\mathbf{A}$

in the upper part of Table 1.

$\mathbf{A}$

in the upper part of Table 1.

Having set prior distributions for individual parameters of matrix

![]() $\mathbf{A}$

, we also use prior information for their interactions. Additionally, we introduce the prior belief on parameter

$\mathbf{A}$

, we also use prior information for their interactions. Additionally, we introduce the prior belief on parameter

![]() $h_1=\det (\mathbf{A})$

, which governs how strongly endogenous variables react to structural shocks, with

$h_1=\det (\mathbf{A})$

, which governs how strongly endogenous variables react to structural shocks, with

![]() $h_1$

close to

$h_1$

close to

![]() $0$

resulting in substantial reactions of endogenous variables to structural shocks.

$0$

resulting in substantial reactions of endogenous variables to structural shocks.

To this end, we assume that:

where

![]() $x \sim At_v(\mu , \sigma , \lambda )$

means that a variable

$x \sim At_v(\mu , \sigma , \lambda )$

means that a variable

![]() $x$

follows an asymmetric Student t distribution with

$x$

follows an asymmetric Student t distribution with

![]() $v$

degrees of freedom, location

$v$

degrees of freedom, location

![]() $\mu$

, scale

$\mu$

, scale

![]() $\sigma$

and skewness

$\sigma$

and skewness

![]() $\lambda$

(see Baumeister and Hamilton, Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2018, for details). In the case of the prior for

$\lambda$

(see Baumeister and Hamilton, Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2018, for details). In the case of the prior for

![]() $h_1$

, we set the values for the location and scale parameters using the averages from 50 000 draws for

$h_1$

, we set the values for the location and scale parameters using the averages from 50 000 draws for

![]() $\mathbf{\theta }_A=(\alpha _{gy}, \alpha _{gp}, \alpha _{gt}, \alpha _{gr},\alpha _{yg},\alpha _{yp},\alpha _{yt},$

$\mathbf{\theta }_A=(\alpha _{gy}, \alpha _{gp}, \alpha _{gt}, \alpha _{gr},\alpha _{yg},\alpha _{yp},\alpha _{yt},$

![]() $\alpha _{yr},\alpha _{pg},\alpha _{py},\alpha _{pt},\alpha _{pr},\alpha _{tg},\alpha _{ty},\alpha _{tp},\alpha _{tr},\alpha _{rg},\alpha _{ry},\alpha _{rp},\alpha _{rt})'$

, the skewness parameter is set to 2 and the degrees of freedom to 3 as in the Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2019). This choice implies a 95.3 percent prior probability for

$\alpha _{yr},\alpha _{pg},\alpha _{py},\alpha _{pt},\alpha _{pr},\alpha _{tg},\alpha _{ty},\alpha _{tp},\alpha _{tr},\alpha _{rg},\alpha _{ry},\alpha _{rp},\alpha _{rt})'$

, the skewness parameter is set to 2 and the degrees of freedom to 3 as in the Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2019). This choice implies a 95.3 percent prior probability for

![]() $h_1$

being positive.

$h_1$

being positive.

Priors for

![]() $\mathbf{D}$

given

$\mathbf{D}$

given

![]() $\mathbf{A}$

. The values of parameters

$\mathbf{A}$

. The values of parameters

![]() $\tau _i$

and

$\tau _i$

and

![]() $\kappa _i$

from equation (3) are set in line with the standard Bayesian VAR literature (Doan et al. Reference Doan, Litterman and Sims1984; Kadiyala and Karlsson, Reference Kadiyala and Karlsson1997; Sims and Zha, Reference Sims and Zha1998). We choose

$\kappa _i$

from equation (3) are set in line with the standard Bayesian VAR literature (Doan et al. Reference Doan, Litterman and Sims1984; Kadiyala and Karlsson, Reference Kadiyala and Karlsson1997; Sims and Zha, Reference Sims and Zha1998). We choose

![]() $\kappa _i=2$

, which means that the weight of the prior for the posterior is equivalent to two full observations from the sample, as in Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2019). Next, we set

$\kappa _i=2$

, which means that the weight of the prior for the posterior is equivalent to two full observations from the sample, as in Baumeister and Hamilton (Reference Baumeister and Hamilton2019). Next, we set

![]() $\tau _i(\mathbf{A})=\kappa _i \mathbf{a}_i'\mathbf{\widehat {S}}\mathbf{a}_i$

, where

$\tau _i(\mathbf{A})=\kappa _i \mathbf{a}_i'\mathbf{\widehat {S}}\mathbf{a}_i$

, where

![]() $\mathbf{\widehat {S}}=\frac {1}{T_1}\sum _{t=1}^{T_1}\mathbf{\widehat {e}}_t\mathbf{\widehat {e}}_t'$

and

$\mathbf{\widehat {S}}=\frac {1}{T_1}\sum _{t=1}^{T_1}\mathbf{\widehat {e}}_t\mathbf{\widehat {e}}_t'$

and

![]() $\mathbf{\widehat {e}}_t=(e_{it},\ldots ,e_{nt})'$

is a vector of residuals from an autoregressive AR(

$\mathbf{\widehat {e}}_t=(e_{it},\ldots ,e_{nt})'$

is a vector of residuals from an autoregressive AR(

![]() $m$

) models fitted to the series of the

$m$

) models fitted to the series of the

![]() $i$

-th endogenous variable

$i$

-th endogenous variable

![]() $y_{it}$

, using the pre-sample set of observations, i.e.,

$y_{it}$

, using the pre-sample set of observations, i.e.,

![]() $t=1,2,\ldots ,T_1$

.

$t=1,2,\ldots ,T_1$

.

Priors for

![]() $\mathbf{B}$

given

$\mathbf{B}$

given

![]() $\mathbf{A}$

and

$\mathbf{A}$

and

![]() $\mathbf{D}$

. The parameters from vectors

$\mathbf{D}$

. The parameters from vectors

![]() $\mathbf{m}_i$

introduced in equation (4) are set to zero. In regards to the

$\mathbf{m}_i$

introduced in equation (4) are set to zero. In regards to the

![]() $\mathbf{M}_i$

matrices from equation (4), their values are set in a standard way and depend on three hyperparameters usually applied in Bayesian VAR analyses: overall tightness (

$\mathbf{M}_i$

matrices from equation (4), their values are set in a standard way and depend on three hyperparameters usually applied in Bayesian VAR analyses: overall tightness (

![]() $\lambda _0=0.1$

), lag decay (

$\lambda _0=0.1$

), lag decay (

![]() $\lambda _1=1$

), and tightness around the constant (

$\lambda _1=1$

), and tightness around the constant (

![]() $\lambda _3=1000$

). In one of the robustness checks we test the model with overall tightness

$\lambda _3=1000$

). In one of the robustness checks we test the model with overall tightness

![]() $\lambda _0=0.2$

.

$\lambda _0=0.2$

.

4.4 The definition of the fiscal multiplier

We follow the definition of the fiscal multiplier in Angelini et al. (Reference Angelini, Caggiano, Castelnuovo and Fanelli2023). The multiplier is defined as the dollar response of GDP to an effective change in government spending or tax revenues of one dollar. Let

![]() $IRF_{y_h}$

be the response of log-output at horizon

$IRF_{y_h}$

be the response of log-output at horizon

![]() $h$

to a (one-standard deviation) fiscal policy shock; and

$h$

to a (one-standard deviation) fiscal policy shock; and

![]() $IRF_{p_0}$

be the impact of the (one-standard deviation) fiscal policy shock to the corresponding fiscal variable, expressed in logs. The

$IRF_{p_0}$

be the impact of the (one-standard deviation) fiscal policy shock to the corresponding fiscal variable, expressed in logs. The

![]() $h$

periods ahead multiplier

$h$

periods ahead multiplier

![]() $\mathbf{M}_{Ph}$

is then expressed as:

$\mathbf{M}_{Ph}$

is then expressed as:

\begin{equation} \mathbf{M}_{Ph} = \frac {IRF_{y_h}}{IRF_{p_0}}\frac {1}{\frac {\overline {P}}{\overline {Y}}}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \mathbf{M}_{Ph} = \frac {IRF_{y_h}}{IRF_{p_0}}\frac {1}{\frac {\overline {P}}{\overline {Y}}}, \end{equation}

where

![]() $P$

is either government spending or government tax revenues, and

$P$

is either government spending or government tax revenues, and

![]() $\frac {\overline {P}}{\overline {Y}}$

is the so-called scaling factor that converts elasticities to dollars.

$\frac {\overline {P}}{\overline {Y}}$

is the so-called scaling factor that converts elasticities to dollars.

![]() $\overline {P}$

denotes the mean across our sample of fiscal spending or tax revenues (not in logs) and

$\overline {P}$

denotes the mean across our sample of fiscal spending or tax revenues (not in logs) and

![]() $\overline {Y}$

denotes the mean across our sample of the level of output (nominal GDP, not in logs). In our baseline sample the scaling factor is equal to

$\overline {Y}$

denotes the mean across our sample of the level of output (nominal GDP, not in logs). In our baseline sample the scaling factor is equal to

![]() $0.205$

for government spending and

$0.205$

for government spending and

![]() $0.270$

for government tax revenues. We do not discount impulse responses (use present values) as it has only marginal effects on the results. The definition (22) also corresponds to the definition in Blanchard and Perotti (Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002) and the alternative definition in Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017).

$0.270$

for government tax revenues. We do not discount impulse responses (use present values) as it has only marginal effects on the results. The definition (22) also corresponds to the definition in Blanchard and Perotti (Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002) and the alternative definition in Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017).

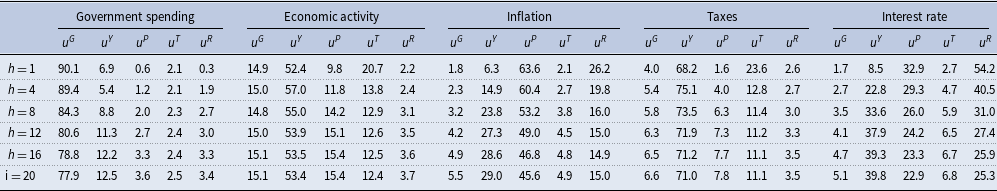

5. Results for the baseline model

This section is devoted to presenting the results. We do it in three steps. First, we investigate the posterior distributions for contemporaneous elasticities. Second, we review the posterior impulse response functions and fiscal multipliers. Third, we quantify short-term and long-term effects of structural shocks on variables considered within our VAR system by calculating forecast error variance decompositions and the historical contributions of these shocks to the percentage deviation of the year-on-year CPI-inflation rate from its long-term mean.

5.1 Posterior of the empirical model

We compare the prior and posterior distributions for the contemporaneous relations matrix

![]() $\mathbf{A}$

. The results are presented in Table 1. We concentrate on the government tax rule and government spending rule. We are particularly interested in the response of fiscal variables to output (

$\mathbf{A}$

. The results are presented in Table 1. We concentrate on the government tax rule and government spending rule. We are particularly interested in the response of fiscal variables to output (

![]() $\alpha _{ty}$

and

$\alpha _{ty}$

and

![]() $\alpha _{gy}$

) that likely strongly affect the value of fiscal multipliers (Blanchard and Perotti, Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002; Caldara and Kamps, Reference Caldara and Kamps2017). We compare the results with those of the papers listed in Table 2. The most important findings are summarized below.

$\alpha _{gy}$

) that likely strongly affect the value of fiscal multipliers (Blanchard and Perotti, Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002; Caldara and Kamps, Reference Caldara and Kamps2017). We compare the results with those of the papers listed in Table 2. The most important findings are summarized below.

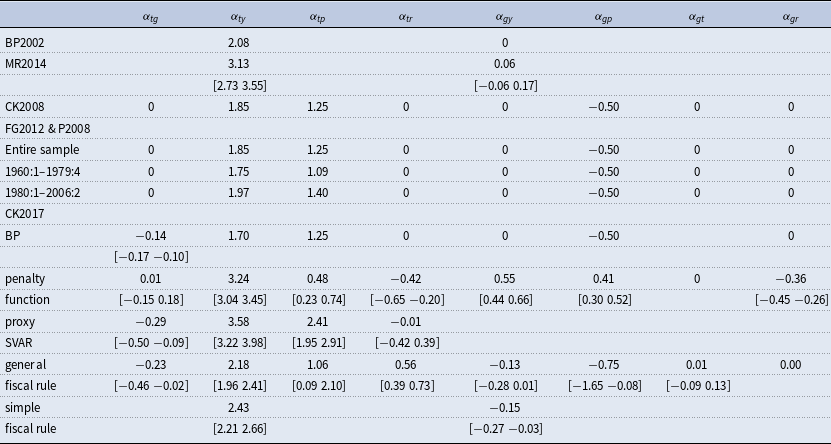

5.1.1 Government spending rule

Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017) state that the size of both tax and spending multiplier hinges critically on the cyclical output adjustment of fiscal variables. They find small and negative systemic response of government spending to output. We confirm this result. We find a negative government spending output elasticity

![]() $\alpha _{gy}$

with a posterior median of

$\alpha _{gy}$

with a posterior median of

![]() $-0.24$

that is not statistically significant. It lies within the range reported in the literature (cf. Table 2). It is similar to the values reported by Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017) for general and simple fiscal rule. Also our estimates lie within the range presented by Angelini et al. (Reference Angelini, Caggiano, Castelnuovo and Fanelli2023), who report a government spending output elasticity between

$-0.24$

that is not statistically significant. It lies within the range reported in the literature (cf. Table 2). It is similar to the values reported by Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017) for general and simple fiscal rule. Also our estimates lie within the range presented by Angelini et al. (Reference Angelini, Caggiano, Castelnuovo and Fanelli2023), who report a government spending output elasticity between

![]() $-0.32$

and

$-0.32$

and

![]() $0$

$0$

Our posterior estimates for

![]() $\alpha _{gp}$

are not statistically significantly different from zero, implying that real government spending does not change contemporaneously with an increase in inflation. Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017), for comparison, report a negative estimate for the contemporaneous response of government spending to inflation (

$\alpha _{gp}$

are not statistically significantly different from zero, implying that real government spending does not change contemporaneously with an increase in inflation. Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017), for comparison, report a negative estimate for the contemporaneous response of government spending to inflation (

![]() $-0.75$

) for their general government spending rule model, but a positive relationship (

$-0.75$

) for their general government spending rule model, but a positive relationship (

![]() $0.41$

) for their penalty function model.

$0.41$

) for their penalty function model.

Table 2. Contemporaneous elasticities for the fiscal policy rules

Notes: The table gathers estimates of contemporaneous elasticities for fiscal policies. Point estimates and confidence intervals (in square brackets) are reported. Abbreviations used: BP2002 – Blanchard and Perotti (Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002), MR2014 – Mertens and Ravn (Reference Mertens and Ravn2014), CK2008 – Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2008), FG2012 – Favero and Giavazzi (Reference Favero and Giavazzi2012), P2008 – Perotti (Reference Perotti and Perotti2008), and CK2017 – Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017). BP refers to Blanchard and Perotti’s (Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002) model specification.

5.1.2 Government tax rule

The output elasticity of taxes is the crucial short-term elasticity estimated in our model. Output represents a base for taxation to a large degree. Mertens and Ravn (Reference Mertens and Ravn2014), among others, establish that it significantly affects the size of tax multipliers. It is often found to be positive and large. In our baseline specification the posterior median for

![]() $\alpha _{ty}$

amounts to

$\alpha _{ty}$

amounts to

![]() $2.26$

and is higher than the assumed prior mode. It lies within our prior confidence interval. However, the median is lower than

$2.26$

and is higher than the assumed prior mode. It lies within our prior confidence interval. However, the median is lower than

![]() $3.13$

, which is the value for which Mertens and Ravn (Reference Mertens and Ravn2014) strongly argue. Angelini et al. (Reference Angelini, Caggiano, Castelnuovo and Fanelli2023) provide a discussion on how sensible the assumption is that the output elasticity of taxes is equal to 3. As we indicate in Table 2, Blanchard and Perotti (Reference Blanchard and Perotti2002) assume the output elasticity of net taxes is equal to 2.08. Perotti (Reference Perotti and Perotti2008), Favero and Giavazzi (Reference Favero and Giavazzi2012), and Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2008) assume a value of 1.85. Caldara and Kamps (Reference Caldara and Kamps2017) prefer a value of 2.18, while Angelini et al. (Reference Angelini, Caggiano, Castelnuovo and Fanelli2023) propose a range from