Introduction

Recent research shows that the welfare rights of immigrants vary across European countries and over time (Koning, Reference Koning2019; Sainsbury, Reference Sainsbury2012). Although the rights of European union citizens have been harmonised to some extent across the EU (Pennings & Seeleib‐Kaiser, Reference Pennings and Seeleib‐Kaiser2018), governments have more power to alter the welfare rights of third country nationals. Governments can directly expand or retrench rights by granting immigrants access to welfare based on their residence status and length of stay (Koning, Reference Koning2013, p. 23), or by attaching consequences to benefit receipt (Römer, Reference Römer2017). Such reforms create a ‘dualised’ welfare state with different levels of protection for citizens and non‐naturalised immigrants. Reducing immigrant welfare rights may allow states to reduce social expenditure without reducing labour immigration (Afonso & Devitt, Reference Afonso and Devitt2016), but evidence suggests such dualism also leads to an increased risk of immigrant poverty and marginalisation (Morissens & Sainsbury, Reference Morissens and Sainsbury2005). Given the politicisation of immigration in recent years, the question of why certain governments choose to extend, and others retrench, is highly relevant (Hutter & Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2021).

A growing scholarship studies the role that political parties play in explaining the expansion or retrenchment of immigrant welfare rights across European democracies. ‘Welfare chauvinism’, or the notion that welfare benefits should be reserved for the ‘native’ population only (Andersen & Bjørklund, Reference Andersen and Bjørklund1990), has received much attention as a dominant policy agenda for parties on the populist‐radical‐right (PRRP; Lefkofridi & Michel, Reference Lefkofridi, Michel, Banting and Kymlicka2017) and to a certain extent the mainstream right (Schumacher & van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and Kersbergen2016). In particular, when governing coalitions between PRRP and mainstream right parties exist, cuts to immigrant welfare rights are most likely (Chueri, Reference Chueri2021). However, the effect of left‐wing parties on such policy reforms remains theoretically and empirically puzzling. Scholars have queried whether left‐wing parties, as classical defenders of the welfare state, promote the extension of welfare rights also to outsiders, or reject the incorporation of diversity into the welfare state (Kymlicka, Reference Kymlicka2015; Reeskens & van Oorschot, Reference Reeskens and Oorschot2012). Empirical studies on policy reforms have produced contradictory findings, with case study evidence showing that left‐wing parties put in place more generous rights (Sainsbury, Reference Sainsbury2012), as well as negative (Schmitt & Teney, Reference Schmitt and Teney2019) and non‐significant associations in larger N studies (Chueri, Reference Chueri2021).

In this paper, we seek to explain these inconsistent findings more systematically. First, the European ‘left’ is not homogenous, but is composed of at least three sub‐families – social democrats, greens and the far left – who face varying ideological and electoral incentives to retrench or expand immigrant rights. The core focus of this paper is social democratic parties, because they are the most likely to participate in government, and in the post‐war era have been the largest left‐wing party across Western Europe (in terms of votes and membership). Second, we argue that because of cross‐cutting electoral and ideological incentives, social democratic parties’ decisions to expand or retrench immigrant welfare rights is highly context dependent.

We scrutinise two contextual time variant factors, namely, political competition from the left and fiscal and labour market pressures. We hypothesise that retrenchment is less likely when social democrats share power with or are electorally challenged by other left parties, because greens and far‐left parties promote redistributive and multicultural policies (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Röth & Schwander, Reference Röth and Schwander2020) that lead them to promote expansive immigrant welfare rights. Second, we expect social democrats to be more likely to retrench immigrant welfare rights when fiscal pressures and unemployment are high, because this allows them to retrench without affecting their core electorate, while simultaneously signalling that they are willing to curb immigration.

We test our hypotheses using a novel dataset that measures immigrant welfare rights across 14 European countries for the years 1980–2018, and find support for our hypotheses, although the effect of left party competition only holds for far‐left parties, not the greens. High levels of unemployment on the other hand make social democrats more likely to retrench immigrant welfare rights. Overall, the results contribute to the literature in a number of ways; first, they suggest that future studies should recognise party heterogeneity in their analysis of left‐wing partisan effects; second, the socio‐economic context parties function within also matters. Finally, the paper uses novel and established datasets, and provides the first analysis of left partisan effects on immigrant welfare rights up to 2018.

‘The left’, social democrats and immigrant welfare rights

The empirical and theoretical literature to‐date has provided contrasting accounts of the left's policy making on immigrant welfare rights. Sainsbury (Reference Sainsbury2012) showed that social democratic governments were instrumental in defending immigrant welfare rights in Sweden, France and Germany in the twentieth century. Yet using cross‐national data on immigrant welfare access, Schmitt and Teney (Reference Schmitt and Teney2019) find a negative effect of left parties. Chueri (Reference Chueri2021) shows that, compared to centre‐right governments, left‐wing governments are more restrictive towards immigrants, but this finding is not significant (p. 7). Römer (Reference Römer2017) performs regressions on time‐series‐cross‐sectional data and also finds no significant relationship between left‐partisanship and changes in immigrant welfare rights.

We argue that the question of left‐wing‐partisan effects should be revisited, because these studies conceptualised, operationalised and measured the left differently, and therefore it is difficult to compare their results. Sainsbury (Reference Sainsbury2012) distinguishes between different left‐wing parties, mainly focusing on the social democrats in her case studies. Schmitt and Teney (Reference Schmitt and Teney2019) use the combined cabinet share of social democratic and communist/socialist parties, whereas Chueri (Reference Chueri2021) and Römer (Reference Römer2017) use measures of left partisanship which compile the share of all ‘left’ partiesFootnote 1; namely, social democrats, far‐left (communist/socialist) and green parties. Combining left parties as such is used commonly as a measure of left partisanship, spanning from immigration policy (Abou‐Chadi, Reference Abou‐Chadi2016; Koopmans & Michalowski, Reference Koopmans and Michalowski2017) to welfare state policy reforms (Engler & Zohlnhöfer, Reference Engler and Zohlnhöfer2019; Gingrich & Häusermann, Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015; Röth et al., Reference Röth, Afonso and Spies2018; Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2016; Vis, Reference Vis2009)Footnote 2.

To solve the puzzle how left‐wing parties affect immigrant welfare rights, however, it is paramount to disentangle the three parties commonly referred to as ‘left’ for at least two reasons. First, these three parties differ in regard to their relative political importance. Green and far‐left parties mostly form coalitions as minority partners in left‐wing administrations, whereas social democratic parties more often dominate cabinet seat‐share and lead governments (Döring & Schwander, Reference Döring and Schwander2015, p. 181). In line with this, social democrats are often at the centre of scholarly debates regarding left‐wing ideological divides over questions of welfare (Schwander, Reference Schwander2019) and immigration (Bale et al., Reference Bale, Green‐Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010). Furthermore, social democrats, greens and the far left differ in regard to their electoral and ideological incentives to promote policies on immigrant welfare rights. The remainder of our theoretical section thus outlines social democratic parties’ policy positionsFootnote 3 in regard to immigrant welfare rights, and conceives cabinet participation of far‐left and green parties as a contextual factor for social democratic policy making.

Social democrats’ unstable position

To date, scholarship has described social democrats’ relationship to immigration and the welfare state as rather ‘torn’. This inner conflict stems from a number of reasons. Immigration and immigrant welfare rights are a complicated issue for social democrats from an ideological perspective. Social democrats’ ‘class orientation’ should lead them to support the rights of all workers, including immigrants (Goldthorpe, Reference Goldthorpe and Goldthorpe1984). However, immigration ‘into’ welfare states has been problematised and depicted as undermining the fiscal and social viability of social security arrangements – constituting a welfare ‘burden’ (Spies, Reference Spies2018). Social democratic parties are therefore confronted with a so‐called ‘progressives’ dilemma’ between striving for equality in the universal sense (including diverse populations and immigrants), or for a selective, nationalist understanding of equality – ‘protecting’ the welfare state for nationals only (Eger & Kulin, Reference Eger, Kulin and Crepaz2021; Kymlicka & Banting, Reference Kymlicka and Banting2017).

This dilemma is intensified given social democrats’ divided electorate. Social democrats have typically been associated with the development and expansion of welfare states across Europe, provided to their cornerstone electorate, the blue‐collar working class (Esping‐Andersen, Reference Esping‐Andersen1990). These voters have been shown to be the most likely to support welfare chauvinism due to their anti‐immigration preferences and perceptions of resource competition (Kitschelt & McGann, Reference Kitschelt and McGann1997; Mewes & Mau, Reference Mewes and Mau2013). Social democrats can, in line with this, use cuts in immigrant rights to attract certain working‐class voters (Schmitt & Teney, Reference Schmitt and Teney2019). Furthermore, studies of vote choice have shown that strong immigration concerns are likely to cause working class voters to shift to vote for the PRRP (Abou‐Chadi & Krause, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Krause2020; Kitschelt & McGann, Reference Kitschelt and McGann1997). Cuts to immigrant rights could signal to working‐class voters a certain ‘accommodation’ of PRRP policies, and thus prevent shifts in voting preferences (Abou‐Chadi & Wagner, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Wagner2020; Hjorth & Larsen, Reference Hjorth and Larsen2020).

This is bolstered by notions of ‘welfare tourism’ increasingly gaining momentum in the public debate (Blauberger & Schmidt, Reference Blauberger and Schmidt2014, p. 2). Traditionally, organised labour has been more critical of open entry policies than equal rights policies, because the former increases labour‐market competition, whereas the latter decreases it (Afonso et al., Reference Afonso, Negash and Wolff2020; Boräng et al., Reference Boräng, Kalm and Lindvall2020). However, if rights and entry are equated, as the ‘welfare tourism’ argument suggests, this support structure across labour organisations and working‐class voters may shift in favour of restricting not only entry, but also the rights of those already residing.

However, the electoral base of social democrats has changed over time. Middle‐class voters increasingly dominate the social democratic electorate and determine their success (Gingrich & Häusermann, Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015). These voters are less welfare chauvinist (Mewes & Mau, Reference Mewes and Mau2013; Oesch, Reference Oesch2008) and authoritarian in their perceptions of welfare beneficiaries’ deservingness (Attewell, Reference Attewell2020; Häusermann & Kriesi, Reference Häusermann and Kriesi2015) than working class voters. By expanding social rights to immigrants, social democratic parties may signal a willingness to supply culturally left constituencies with pro‐immigrant policies. Thus, immigrant welfare rights, and immigration policies more broadly, have proved electorally challenging for many social democratic parties due to divergent preferences within their voter‐constituencies.

Finally, there is yet another perspective regarding how social democrats might approach immigrant welfare rights. The rise of third‐way social democracy in the 1990s has also led some social democratic parties away from their classical connection to the welfare state, and closer to market solutions for economic policy (Horn, Reference Horn2020). Under this third‐way logic, liberal immigrant entry policies promise to compensate for labour shortages or reify comparative advantage within political economies (Afonso & Devitt, Reference Afonso and Devitt2016). Combined with reluctance to expand welfare provision in general (Bremer & McDaniel, Reference Bremer and McDaniel2020), it is likely that while supporting liberal immigration policies, third‐way factions within social democratic parties are opposed to increasing benefit access for migrants.

Ultimately, social democrats’ policy making in regard to immigrant welfare rights is thus tied‐up with complex and loaded public and internal‐party debates regarding what constitutes equality and which social, labour market and immigration policies are best suited to achieve it.

The importance of context

The electoral and ideological divides described in the previous section hinge on the mixed composition of social democrats’ electorates. Different to welfare state reforms that affect citizens, however, we do not expect immigrant welfare rights to be an issue that is central for voters. Instead, cuts or expansions in immigrant rights could be used instrumentally under certain conditions to appease different interests in the divided electorate. Therefore, rather than assessing whether the electorate tilts towards working or middle‐class voters (see Gingrich & Häusermann, Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015; Engler& Zohlnhöfer, Reference Engler and Zohlnhöfer2019, we explore two types of factors with regard to political and socio‐economic context. Our first hypotheses introduce the role of other left‐wing parties – the greens and the far left – who we theorise have a progressive influence on social democrats (a) when sharing cabinet power and (b) when they are successful at elections.

The party that most clearly represent a pro‐immigrant electorship are the greens, who emerged as a result of the prominence of new social movements in Europe in the 1960s. Next to fighting climate change, they tend to promote pro‐European, internationally solidarious and pro‐social justice policies (Dennison, Reference Dennison2017). In turn, their voters are disproportionately middle‐class, with open, cosmopolitan views (Attewell, Reference Attewell2020, Reference Attewell2021; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüst2012). Furthermore, they have been shown to reject welfare chauvinism the most strongly of all groups, and demand equality between natives and immigrants (Enggist, Reference Enggist2020). Therefore, to retain their core group of voters, green parties are likely to support the extension of immigrant welfare rights. Indeed, other studies have shown that green parties in coalition governments are likely to promote open immigration policies (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018) and middle‐class welfare policies (Fagerholm, Reference Fagerholm2016; Röth & Schwander, Reference Röth and Schwander2020). We extend this to immigrant welfare rights, and expect that green party coalition partners will prevent restrictive immigration reforms and will promote the extension of rights.

The progressive influence from green parties mainly stems from their culturally left politics, whereas far‐left parties mobilise voters through strong positions on economic politics and their commitment to anti‐capitalism and representation of workers (Visser et al., Reference Visser, Lubbers, Kraaykamp and Jaspers2014). In line with this, welfare politics and social justice are more salient in far‐left politics, matching the preferences of their voters, who demand changes to market‐dominated capitalism above all else. Importantly for these parties, fair representation of workers does not equal anti‐immigrant politics: Evidence from party manifestos shows very little use of anti‐immigrant sentiment at elections (Burgoon & Schakel, Reference Burgoon and Schakel2022), and survey evidence proves that far‐left voters are no more anti‐immigrant than the average (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Zaslove and Spruyt2017; March & Rommerskirchen, Reference March and Rommerskirchen2015). Although studies have evidenced nuanced positions regarding immigrant entry (e.g., Krings, Reference Krings2009), far‐left parties tend to promote equal working conditions for all members of the proletariat (Edo et al., Reference Edo, Giesing, Öztunc and Poutvaara2019)Footnote 4. It follows, that any retrenchment of the welfare state, be it to immigrants or citizens, would have the potential for electoral penalty, and also runs counter to the ideological positions of the far left.

We derive the first hypotheses regarding cabinet sharing between social democrats and other left parties, as minority‐coalition partners have the potential to represent their voters’ needs and affect policy direction (Röth et al., Reference Röth, Afonso and Spies2018; Röth & Schwander, Reference Röth and Schwander2020)Footnote 5.

H1a: Social democratic parties in government are less likely to retrench immigrant welfare rights the higher the cabinet share of far‐left or green parties.

This moderating effect may not only occur through shared government participation, however. Previous studies show that the policies pursued by social democratic‐led governments are in fact a function of the structure of electoral competition on the left itself (Manow, Reference Manow2008; Watson, Reference Watson2008). The electoral pressure on social democrats to keep core groups of voters increases when viable competition emerges to the left and right (Abou‐Chadi & Immergut, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Immergut2019). Thus, the more votes (and more often than not, seats) other left parties gain at elections, the higher the risk that mainstream left parties will suffer electoral losses from culturally left voters (to the greens) and pro‐welfare voters (to the far left). In both of these eventualities, retrenchment of immigrant welfare rights results in a signalling effect to these voters, who may shift elsewhere. H1b follows:

H1b: Social democratic parties are less likely to retrench immigrant welfare rights when far‐left or green parties gained votes at the previous election.

Avoiding blame and claiming credit in times of pressure

The second step in our theoretical framework is to outline when social democratic governments will be likely to attend to electoral calls to restrict welfare rights of immigrants. As mentioned above, retrenchment of immigrant welfare rights may signal a willingness to curb immigration to working‐class voters, a crucial constituency of social democratic parties, who are most likely to perceive immigrants as threats to labour‐market security (see also Consterdine & Hampshire, Reference Consterdine and Hampshire2014; Hainmueller & Hiscox, Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2010) and who are also most likely to support welfare chauvinism.

Drawing from political economy research, we expect that the need to attend to these voters is conditional on economic context. Although in times of economic prosperity and growth, labour demand is high and liberal immigration policies are more popular (Natter et al., Reference Natter, Czaika and Haas2020; see also Afonso et al., Reference Afonso, Negash and Wolff2020, p. 529; Massey et al., Reference Massey, Arango, Hugo, Kouaouci, Pellegrino and Taylor1993), when unemployment rises, immigrants can be perceived as threatening to jobs and wages, particularly for working class groups (Boräng, Reference Boräng2018). Given that poor socio‐economic conditions have been shown to lead voters to shift to PRRPs (Stockemer et al., Reference Stockemer, Halikiopoulou and Vlandas2021), we argue that particularly in times of fiscal pressure and high unemployment, cuts to immigrant welfare rights are more likely for social democratic governments.

Beyond electoral pressure, this argument is in line with research on welfare retrenchment in the twentieth century, which illustrates that social democrats were forced to retrench under conditions of austerity. Indeed, left‐wing governments were responsible for a number of retrenching reforms – particularly in the ‘third way’ governments of the 1990s and 2000s onwards, that introduced conditions and sanctions to welfare receipt as well as following the Great Recession in 2008–2010 (Bremer, Reference Bremer2018). New Labour in the United Kingdom and the Schröder government in Germany, for example, scaled back classical programmes of unemployment benefits and social assistance (Horn, Reference Horn2020). Nevertheless, as argued by Pierson (Reference Pierson1996), retrenchment in any form can be construed as unpopular, and still requires careful framing and policy signalling.

Using Pierson's terminology, by targeting immigrants, social democratic governments can decrease expenditures (‘credit claiming’, as budgetary responsibility is praised in times of crisis), while at the same time ‘avoiding’ blame, because the broader electorate are not materially affected by cuts to immigrant rights. Even altruistic voters who oppose the retrenchment of immigrant welfare rights due to positive attitudes towards immigrants are more likely to support welfare chauvinism in times of high economic insecurity where their material insecurity may be threatened (Magni, Reference Magni2020). Thus, in addition to the electoral incentives vis‐à‐vis working‐class voters, cuts targeted towards immigrants are more favourable to vote‐seeking social democrats when unemployment and financial deficit is high than in times of economic stability. Given that fiscal pressure and unemployment are likely to affect the government, workers and general population in different ways, we formulate two separate hypotheses here:

H2a: Social democrats are more likely to retrench immigrant welfare rights in times of high fiscal pressure than in times of low fiscal prosperity.

H2b: Social democrats are more likely to retrench immigrant welfare rights in times of high unemployment than in times of low unemployment.

Research design: Data and methods

To test our hypotheses, we use data on immigrant welfare rights in 14 Western European countries for the years 1980–2018. The selection of countries ensures differentiation among uniformity: They are all democratic, capitalist welfare societies, that are members of the EUFootnote 6, yet differ substantially in regard to the strengths of left parties in general, social democrats in particular, and the contextual factors outlined in the hypotheses. We use country‐years as the unit of analysis, although cabinets are used in the robustness checks following calls that government ideology variables are biased in country‐year model specifications (Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2016)Footnote 7. For a full explanation of the cabinet periodisation and models, see Section B of the Appendix in the Supporting Information. Our final sample contains 439 country‐year observations, or 179 cabinet observations.

Dependent variable

Data used for the dependent variable immigrant welfare rights come from the IMPIC and Migrant Social Protection (MigSP) datasets, both of which collect data using surveys with legal experts. IMPIC collected data on immigration policy including policy on immigrant welfare rights for 33 OECD countriesFootnote 8 for the period 1980–2010 (Bjerre et al., Reference Bjerre, Helbling, Römer and Zobel2016; Helbling et al., Reference Helbling, Bjerre, Römer and Zobel2017). For the years 2011–2018, we rely on new data collected under the remit of the MigSP dataset (Römer et al., Reference Römer, Henninger, Harris and Missler2021). Both data sources conceptualise immigrant welfare rights as a relative measure that depicts to what extent immigrant welfare rights differ from the rights of citizens, for example, through additional eligibility requirements and/or specific consequences that are attached to benefit receipt for immigrants.

The data cover four dimensions of immigrants’ social rights in nine items: eligibility conditions (three items), type of benefits (one item), consequences of benefit receipt (three items) and ‘preventive measures’ (two items) and differentiates between the rights of permanent and temporary labour migrants, asylum seekers, recognised refugees and family reunification. The final index of immigrant welfare rights is the unweighted average of the four dimensions and ranges from 0 to 10, with higher scores denoting more rights for immigrantsFootnote 9 (for more details on construction, see Appendix A in the Supporting Information and Römer et al., Reference Römer, Henninger, Harris and Missler2021).

Main explanatory variables

The core independent variable in our analyses is government participation of left parties. First, as we are interested in differentiating between sub‐types within the ‘left’ we include three variables that measure the cabinet share of social democrats, far‐left parties and green parties. The coding of parties follows the ParlGov dataset (Döring & Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2019). We construct a variable for the cabinet share relative to total cabinet posts held by social democrats, far‐left and green parties, weighted by the number of days in office in that given year. To test H1a, we interact the measures of cabinet shares in separate models, that is, we include an interaction between the cabinet share of social democrats and the cabinet share of green parties and an interaction between the cabinet share of social democrats and the cabinet share of far‐left parties.

To test H1b, we include models which interact the social democratic cabinet share with the electoral success of greens and far‐left parties at the previous election. Instead of using seat share in the legislature, which could bias against majoritarian or two‐step electoral systems, we choose vote‐share at the previous election to gauge the popularity of different parties.

To test H2a and H2b, we include an interaction of cabinet share of social democrats with two fiscal variables; the absolute rather than harmonised unemployment rates to incorporate even short‐lived spikes or dips in the level of unemployment, and a variable indicating budget deficit. Appendix C in the Supporting Information provides an overview of sources for the indicators used.

Control variables

Previous studies have highlighted the importance of a number of variables which should be controlled for as they are associated with both the core independent and dependent variables. First, generous welfare states with high levels of spending have been shown to lead to greater inclusion of immigrants into the welfare state (Schmitt & Teney, Reference Schmitt and Teney2019), as well as reinforce the strength of left parties (Huber & Stephens, Reference Huber, Stephens and Pierson2001). We therefore include a measure of social expenditure as a percentage of total GDP, as well as controlling for GDP per capita to correct for richer and poorer statesFootnote 10. Migration levels are also linked to welfare chauvinism and party competition in the literature, although the evidence remains ambiguous (Natter et al., Reference Natter, Czaika and Haas2020). We thus also include yearly measures of the size of the foreign‐born population (OECD, 2017), which serves as an indicator of the stock of migrants in a country. The standard definition of foreign‐born is ‘all persons who have ever migrated from their country of birth to their current country of residence’ (OECD, 2017). All models also include the unemployment rate as a control. PRRPs in government have been shown to conduct cuts in immigrant welfare rights (Chueri, Reference Chueri2021), and there is also evidence that parties may shift to the right on immigration when PRRPs are present (Schumacher & van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and Kersbergen2016). Our analytical focus is on government participation, of which there is no cabinet in our sample with PRRP and social democrat partners. We thus, in all models, include PRRP electoral gains as a control variable.

Estimation strategy

We pursue a two‐tier empirical strategy, including both models that rely on country‐years as well as cabinets as the unit of analyses. In the main text, we focus on the results of the country‐year analyses. To fully exploit the time series nature of our data, we employed an ordinary‐least‐squares regression with panel corrected standard errors and a first‐order autocorrelation correction (OLS‐PCSE AR1; Beck & Katz, Reference Beck and Katz1995). All models include a lagged dependent variable. Country fixed effects are included to account for cross‐sectional heterogeneity of the intercepts and omitted variable bias, controlling for time‐invariant, country‐specific aspects. The model specification in the main text is presented in levels. All explanatory variables are lagged 1 year.

For sensitivity analysis in the country‐year specification, other panel methods were used as well and are shown in Section E of the Appendix in the Supporting Information. Table AII of the Appendix in the Supporting Information shows the results for the models including generosity instead of social expenditures. When testing the dependent variables for stationarity, a number of panels have a unit root but not all. Accordingly, Table AIII of the Appendix in the Supporting Information presents a model using changes as the dependent variable as a robustness check. Third, including the lagged dependent variable alongside fixed effects may result in Nickell bias (Nickell, Reference Nickell1981) which causes an inflation of standard errors. We thus also included a specification without a lagged dependent variable, which is shown in Table AIV of the Appendix in the Supporting Information. In Table AV of the Appendix in the Supporting Information, we also include a model that includes both country and year fixed effects. Year fixed effects allow to control for period specific effects, but two‐way fixed effects models make strong assumptions about pooled time‐series cross‐sectional datasets (see Kropko & Kubinec, Reference Kropko and Kubinec2018), which can make interpretation more difficult.Footnote 11

The remainder of the tables in the Appendix of the Supporting Information show the results for the second set of robustness checks using cabinet level data (Tables AVI–AVIII). Given that we are interested in the partisan effect of cabinets, some literature argues that using cabinet units rather than country‐years is more suitable, because the core independent variable of interest does not change yearly but rather as a new government comes into power (Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2016). A full explanation of the cabinet periodisation process can be found in Section B of the Appendix in the Supporting Information. All models include the level of the dependent variable in the last year of cabinet of the sample. Table AVI of the Appendix in the Supporting Information depicts the results for robust standards errors and period fixed effects, whereas Table AVII of the Appendix in the Supporting Information shows the model using OLS standard errors and country dummies. Table AVII of the Appendix in the Supporting Information finally uses OLS standard errors and includes period dummies and country dummies. In addition, Table AIX of the Appendix in the Supporting Information shows a summary of re‐estimated models 1–7 of Table 1 dropping one country at a time. With small exceptions, the results were consistent, though effect sizes and significant levels varied.

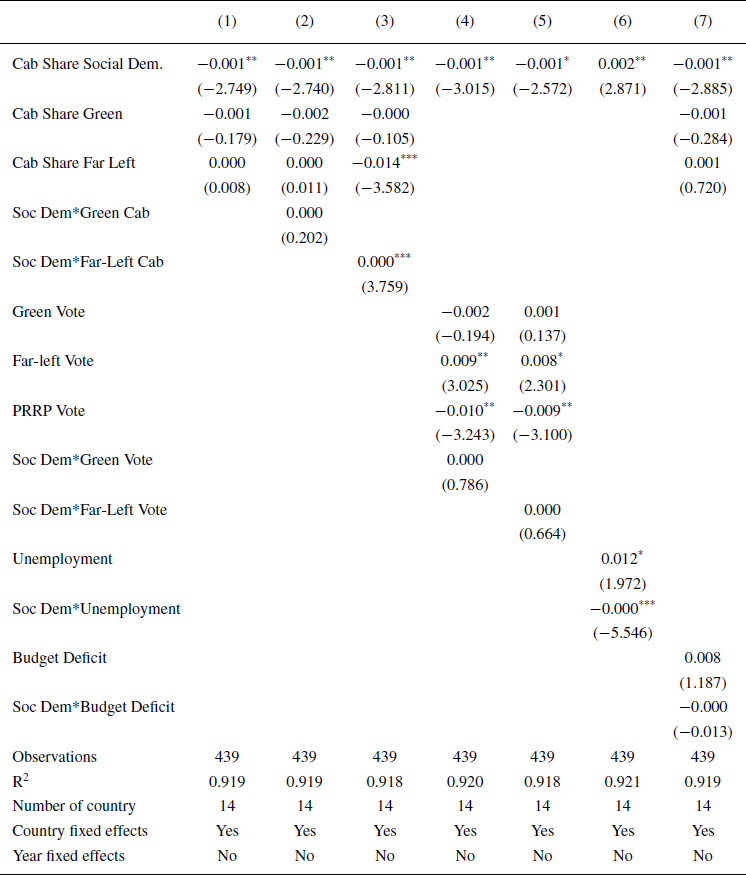

Table 1. Results for main model specification, DV = immigrant welfare rights

Note: z‐Statistics in parentheses. ***p < 0.001;

**p < 0.01;

*p < 0.05; +p < 0.1. Panel corrected standard errors are shown in parentheses.

Results

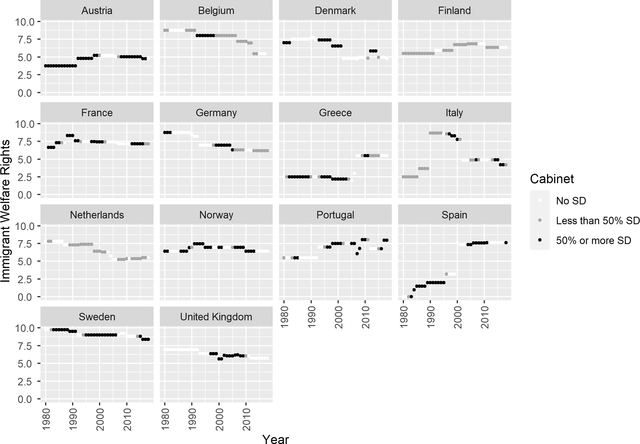

Figure 1 presents the changes to immigrant welfare rights that social democratic parties in power took part in across 14 Western European countries from 1980 to 2018. The figure shows that even though countries differ, all countries in the sample grant at least some rights to immigrants. In the whole time period, no country grants immigrants the equivalent rights of citizens (which would amount to a 10 on the immigrant welfare rights scale).

Figure 1. Social democratic parties in power and immigrant welfare rights, 1980–2018.

Note: SD = social democrat. For more information on scoring of rights, see Appendix A in the Supporting Information.

Although an overall trend towards restrictiveness can be observed over time in Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom, there are notable increases in rights in the Southern European countries Italy, Portugal and Spain. Second, the figure shows that, at the aggregate level of our analyses, left‐wing governments are responsible for both cuts and expansions of immigrant welfare rights. Although in Spain, for example, increases in rights in the late 1980s and mid‐2000s were the responsibility of social democratic governments, the Portuguese case in the 2000s, and France in the 1980s, shows that both increases and decreases occurred under the mainstream left. In the following empirical part, we test whether cabinet composition and economic pressures explain these patterns.

Table 1 presents the results for our main model specification, including panel‐corrected standards errors, a lagged dependent variable and country fixed effects (for full table including control variables, see Appendix AI in the Supporting Information). We report unstandardised coefficients. As was outlined in the theory section, we are interested in possible differences between left parties. Model 1 therefore differentiates between social democrats, green and far‐left parties. The results show that although on average social democrats are negatively associated with immigrant welfare rights, neither greens nor the far left are significantly associated with changes in immigrant welfare rights. These findings suggest that the negative effects of the left reported by previous studies are driven by the social democrats.

More substantially, the results indicate that holding every other variable at their mean, a 1 per cent increase in social democrat cabinet share is associated with a score of immigrant welfare rights that is roughly 0.001 lower. This means going from a cabinet with no social democrats to a cabinet that is fully social democratic amounts to a decrease in immigrant welfare rights of about 0.1. While this may seem like a small difference at first, recall that ‘immigrant welfare rights’ are represented by an index. The extreme values of 0 and 10 are the theoretical maximum/minimum, which empirically, especially in a sample of Western European countries, are unlikely to occur. Numerically small changes in the aggregate are however still indicative of rather momentous policy changes. A change of 0.1 is equivalent to, for example, the policy change that occurred in France in 1993, when it was specified that immigrants that relied on social benefits did not qualify for family reunification.

While the negative association between social democratic government share and immigrant welfare rights confirms the findings of some previous studies, in this paper we were mainly interested in whether and how contextual factors condition the relationship between social democrats and immigrant welfare rights. In models 2–7, we thus introduce a number of interaction terms to explore ‘contextual’ chauvinism. First, we assess whether the composition of cabinets (models 2 and 3) and competitive divisions on the left at elections (models 4 and 5) mediate the relationship between social democrats and policies on immigrant welfare rights as outlined in H1a and H1b.

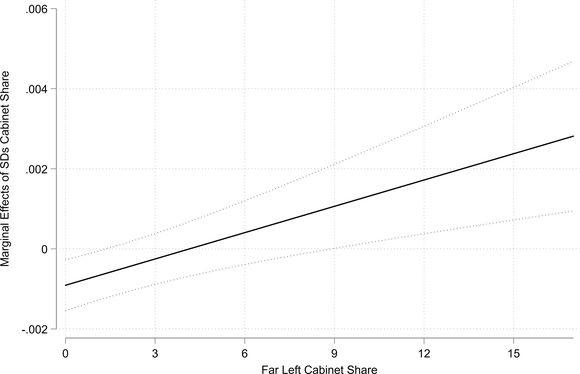

Model 3 shows that there is no evidence that green parties moderate social democrats in power – there are no significant interaction effects, also in robustness checks. A positive interaction effect was however found for far‐left cabinet share and social democrats in cabinet. This also held up in robustness checks, and thus lends support for H1a: when they share power, far‐left parties seem to push social democrats towards more generous policies on immigrant welfare rights. Recall that in the table we report unstandardised coefficients. As the cabinet shares of far left and social democrats are continuous variables, the interaction term has a wide range, and the coefficient for the interaction is not very informative. Figure 2 thus depicts the marginal effect of an increase in social democrat cabinet share across far‐left cabinet share. Although in cabinets with a far‐left share of zero, a 10 per cent increase in social democrats’ cabinet participation leads to a decrease of about 0.01 in immigrant welfare rights, at 15 per cent of far‐left cabinet share, a 10 per cent increase in social democrat cabinet share is associated with an increase of about 0.02. Again, while these may seem like small‐sized effects, the aggregate nature of the index masks that such small changes are equivalent of, for example, a change in the number of permanent permits that do not impose sanctions such as loss of residence permit in case of benefit receipt.

Figure 2. Effect of social democrats on immigrant welfare rights at various levels of far‐left cabinet share.

Note: As the frequency distribution of the far‐left cabinet share variable is strongly right skewed (with the majority of observations being 0) as a robustness check we estimated the models using a binary measure of far‐left cabinet participation. Results remained unchanged (see Figure AXA and Table AX in the Appendix of the Supporting Information).

It should be noted that in the analyses using country‐years as unit of analysis there is no significant evidence for an indirect effect of any of the parties through vote share at the previous election. This finding was however not corroborated in the cabinet models, where the cabinet share interaction between social democrats and far left was found to be not significant, but there was a significant positive interaction between far‐left vote share at the previous election and social democratic cabinet share (see OAV1). While the results are thus sensitive to the operationalisation of far‐left strengths, overall, the findings support that there is a mediating effect of the far left.

It is useful to reflect on the qualitative evidence from our sample to expand on these results. Far‐left parties often form small minorities in larger, fragmented cabinets. In Denmark in 2011, the minority coalition government led by the Social Democrats, with the Social Liberals and Socialist People's Party (and support of the Red‐Green Alliance), began their premiership by rectifying the retrenchments put in place by the right‐wing government in 2002 that imposed a work/residence requirement of 2.5 years from the last 8 to access social assistance (Jørgensen & Thomsen, Reference Jørgensen and Thomsen2016). Although the coalition differed on the economic dimension and the Socialist People's party eventually left the government in 2013, they were pivotal in unifying the cabinet on issues such as immigration, integration and justice when the coalition agreements were written (Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen2020). Another example is the Prodi‐led cabinet of Italy from 2006 to 2008, in which different left parties and some Christian conservative parties ruled together, pushing through the Decree 251/2007 which set minimum standards for the social and economic rights that refugee and asylum seekers can accessFootnote 12(Finotelli & Sciortino, Reference Finotelli and Sciortino2008, p. 4). These examples show that across different welfare state regime types, and economic contexts, sharing power with the far‐left leads to expansions, rather than restrictions.

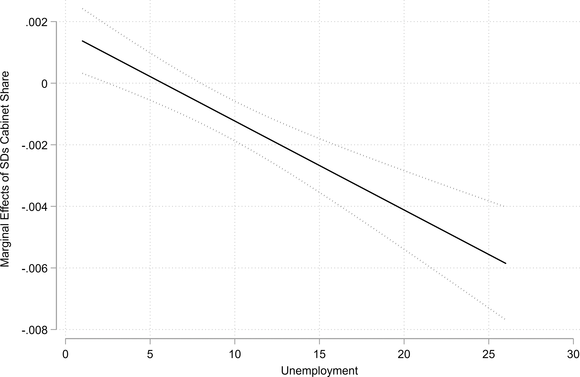

Turning now to H2a and H2b, models 6 and 7 include interactions between the social democrats’ cabinet share and unemployment levels and budget deficit, respectively. Although no significant association was found for the budget deficit interaction (H2a), the unemployment interaction was found to be negative throughout all model specifications (H2b). Again, the unstandardised coefficient reported in Table 1 is not substantially informative. Figure 3 thus illustrates the relationship at play.

Figure 3. Effect of social democrats on immigrant welfare rights at various levels of unemployment.

Note: As the frequency distribution of the unemployment variable is right skewed, as a robustness check we estimated the models using the natural log of unemployment. Results remained unchanged (see Figure AXB and Table AX in the Appendix of the Supporting Information).

The figure shows that although in times of low unemployment, increases in social democratic cabinet share are associated with even more rights, the relationship is reversed as unemployment increases. An example in point are Portuguese immigration and welfare reforms. In the 1990s, when unemployment was low, and labour shortages high, the Socialists (the comparable party to social democrats or the mainstream left in this case) in government liberalised labour migration – which was repealed by the centre right 1 year later (Law Decree 4/2001, Law Decree 34/2003). Following the financial crisis, when unemployment was high, the Socialists reformed the conditions to apply for the social assistance which excluded some migrants from accessing it (European Commission, 2015, 18). In other countries, there is some evidence that unemployment leads to welfare reform, in general, in social democratic‐led governments, which can include restrictive eligibility clauses and thus retrenchment in immigrant welfare rights. For example, in the Netherlands, both the Lubbers and Kok governments in the late 1980s and 1990s restructured immigrant benefits, following increases in unemployment and increased social assistance uptake (Koning, Reference Koning2019, p. 167).

The significant and robust effect in our models suggests that above all other conditions, the socio‐economic context in which social democratic governments find themselves has an influence on reforms to immigrant welfare rights. That unemployment seems to explain more variance in social democratic policy making than deficit levels, reifies the relevance of electoral arguments: The perceptions of scarce resources – jobs – has been tied directly to working‐class voters (Hainmueller & Hiscox, Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2010), and our results ultimately suggest that cutting immigrant welfare rights could be used by the mainstream left to ‘claim credit’ from these voters.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that, all things equal, social democrats are negatively associated with immigrant welfare rights, but that this is conditional on a number of factors. By introducing a comparative research design and interaction effects, we can show that contextual factors matter: Low unemployment and the electoral and government success of smaller left parties drive differences in social democrats’ policy making. This story of ‘contextual chauvinism’ further tabs into the ideological and electoral ambiguity of social democrats which previous work, such as the ‘progressives’ dilemma’ scholarship, has mooted. It can also help explain the contradictory findings across antecedent research designs, and we encourage future research to build on this contextual logic for understanding parties’ positions and policy‐making decisions.

Our findings furthermore contribute to the literature in three ways. First, we move away from the standard welfare chauvinism literature, and show that other party families – not only PRRPs – are important factors to consider when explaining how welfare chauvinist sentiment is translated into policy realities. Our analyses does, however, include PRRP vote share as a control, which is negative and significant in almost all robustness checks, thus corroborating the finding of previous studies that PRRP success has politicised welfare chauvinism and may have policy repercussions (Chueri, Reference Chueri2021). Second, our paper highlights the analytical strengths gained by assessing different types of immigration policies to understand the ‘progressives’ dilemma’. Previous studies have certainly done this too, differentiating between immigration control and integration policies, for example, and showing that the left is generally associated with more liberal integration policies than the right (Givens & Luedtke, Reference Givens and Luedtke2005; Lutz, Reference Lutz2019). However, our paper demonstrates the utility of even further separating immigrant welfare rights from other integration policies to understand left‐wing partisan effects. Finally, we contribute empirically to the literature on partisanship and welfare chauvinism, by providing an analytical measure of welfare chauvinism (or its opposite) in policy reforms. Until now, the welfare chauvinism scholarship comprises mostly of either attitudes or party competition data, and this paper continues the recent trend of analysis of policy reforms themselves, which remain under‐researched in comparison.

There are, however, a number of shortcomings as well as avenues for further research that should be addressed in the future. More attention could be paid to other contextual factors such as welfare state and immigration regimes, which due to the country fixed effects in our models were difficult to unpick. It is likely that these factors shape the arsenal of strategies parties have at their disposal. Furthermore, although party competition on the left was used to approximate the electoral threat facing the mainstream left, future studies could better integrate the actual class‐composition of party electorates to assess whether progressive voters form the majority (see Gingrich & Häusermann, Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015; Engler & Zohlnhöfer, Reference Engler and Zohlnhöfer2019). Finally, and potentially most importantly, although our quantitative methodology is useful for drawing out patterns, and enlisting some evidence from a couple of cases where we also found qualitative support for our hypotheses, a core limitation of the study remains the lack of in‐depth evidence to specify mechanisms at play. Interviews with policy makers and comprehensive analyses of individual reform processes could fully elucidate in which ways politicians used cuts or expansions to rights to avoid blame from the electorate, or to appease far‐left cabinet members. In this vein, future studies could use IMPIC and MigSP data to distinguish between different migrant groups, and assess to what extent labour migrants, family reunification migrants and asylum seekers are treated differently by policy makers. On balance, this paper lays the groundwork for more granular approaches to understand the immigration‐welfare politics of left‐wing parties.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of the paper profited from the close reading and feedback of Bastian Becker, Romana Careja, Jakob Henninger, Alexander Horn, Johanna Kuhlmann, Philip Manow, Elias Naumann, Carina Schmitt, Arndt Wonka and Reimut Zöhlnhofer, and other participants at workshops at the Nordwel Summer School (2019), ESPANET Annual Conference (2019) and the Centre for European Studies at Harvard (2020). Excellent research assistance was provided by Marcus Boehme, Franziska Missler, Linh Phuong and Kevin Wang. Finally, we thank the editors at European Journal of Political Research and three anonymous reviewers for their detailed comments and useful feedback. All mistakes and omissions are our own.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data Availability Statement

The Migrant Social Protection (MigSP) Database data used to complete this research are currently under an embargo period for the central research team and for the experts involved in the data collection effort. This embargo period will be lifted in late 2022 and the data will be freely available for use. IMPIC data (1980–2010) are already available to download from http://www.impic‐project.eu/data/

Funding Information

Eloisa's research has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska Curie Grant Agreement No. 713639. Both researchers and the data collection were funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Projektnummer 374666841 – SFB 1342 ‘Global Social Policy’ at the University of Bremen.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

There are no conflicts of interest or breaches of ethical conduct. The author confirms that this paper has not been published elsewhere nor is permission required to replicate material from other sources.