Introduction

When countries export arms, they deliver a very peculiar good: Economically, arms trade nourishes a sizable industry with a global turnover of $361 billion for the 25 largest companies alone.Footnote 1 With respect to security, arms transfers affect both the global balance of power but also the specific security environment of exporting and importing states (García‐Alonso & Levine, Reference García‐Alonso and Levine2007). Normatively, arms are a coercive technology with the potential to kill, employed for ‘just wars’ as well as for aggression or suppression (Bellamy, Reference Bellamy2006). Notably, eight of the 10 largest exporting countries are democracies (Wezeman et al., Reference Wezeman, Fleurant, Kuimova, Silva, Tian and Wezeman2020), but, to our knowledge, research on the institutional and preferential preconditions of democratic accountability for this policy area is lacking.

The heated public debates in NATO countries surrounding weapons transfers to Ukraine before and after the Russian invasion in 2022 provide a case in point. In a prominent example, the German government first opposed such exports categorically but turned its position drastically after the invasion.Footnote 2 At the same time, public opinion flipped – from about two‐thirds opposed to two‐thirds approving the transfers of even offensive weapons (see Online Appendix section A.1).Footnote 3 As Ukrainian president Wolodymyr Selenskyj put it: ‘I gladly notice that the position of Germany moves favourably towards Ukraine. And I think this is absolutely logical, given the majority of the German population supports this move’ (daily video address on 10 April 2022, own translation). Hence, we propose that it is both theoretically worthwhile and practically relevant to understand public opinion on arms transfers. We thereby tie into an ongoing debate in the recent literature, indicating that citizens hold reasoned preferences on foreign policy and that their attitudes matter for government decision‐making (see Online Appendix section A.2).

With this article, we address three core questions: To what extent does opposition ‘per se’ prevail in mass public preferences regarding arms exports? How do citizens weigh strategic, economic and normative factors when deciding on arms exports? Do these considerations vary in two major Western arms‐exporting democracies, Germany and France? Theoretically, we propose that we need to differentiate two fundamental types of preference formation of citizens. First, for some, preferences could be determined by fundamental convictions. With so‐called deontological motivations (Chen & Schonger, Reference Chen and Schonger2022), citizens do not reason under which conditions, but whether at all arms should be traded. Empirical investigations of the presence of deontological preferences are generally rare, but even more so in the field of foreign policy preference formation (see for exceptions Dill & Schubiger, Reference Dill and Schubiger2021; Nincic & Ramos, Reference Nincic and Ramos2011). To our knowledge, only research on a nuclear taboo has systematically investigated whether principled objection structures citizen preferences, with some evidence pointing against (e.g., Dill et al., Reference Dill, Sagan and Valentino2022; Press et al., Reference Press, Sagan and Valentino2013) and other evidence towards (e.g., Rathbun & Stein, Reference Rathbun and Stein2020) principled preferences. We investigate whether deontologist motivations are important for arms trade as a prominent policy decision that directly relates to the use of military force, and where principled arguments are frequently put forward in public discourse. Second, for other citizens, much like governments, arms trade could constitute a multi‐dimensional policy object that combines economic, geo‐strategic and normative aspects, as political economy theories argue (García‐Alonso & Levine, Reference García‐Alonso and Levine2007). These citizens would apply a consequentialist mode of decision‐making, but we do now know how they reconcile potential trade‐offs between these three dimensions in their calculus. Of course, the prevalence and manifestation of these two types of preference formation could differ between countries, constraining governments to differing degrees. We therefore explicitly investigate citizens' preferences in two divergent cases with distinct histories and institutions, Germany and France – both global top‐five exporters of arms, but the latter a nuclear power with high geopolitical ambitions, the former with a posture of a ‘civil power’.Footnote 4

Empirically, we draw on a population‐representative online survey with 6617 (voting‐age) citizens, half from each country, giving us sufficient power to investigate even complex conditional relationships. We triangulate from respondents' replies to experimental rating tasks, open‐ended survey questions, and established survey scales to identify deontologist respondents. Conjoint choice experiments allow us to identify nuanced trade‐offs between economic, strategic and normative aspects of arms transfers. Our theoretical argument, empirical analysis and sample size calculation follow an extensive pre‐registration (see Online Appendix B).

Our results imply that around 10–15 per cent of respondents voice principled opposition to arms trade even under the most favourable context conditions. A majority strongly conditions their support on the economic, strategic and normative characteristics of an arms transfer, with the latter bearing the strongest relative weight. Notably, certain attribute configurations moderate these relative weights. For example, defensive wars attenuate concerns for trade with states in conflict. International supply competition alleviates normative concerns and enhances the relevance of the economic and strategic dimensions. Comparing French and German respondents, we show that the general calculus is similar for both populations, while German respondents are more likely to express principled opposition and give larger weight to unfavourable normative contexts in general.

We hence contribute a public opinion perspective to an otherwise state‐ and elite‐focused literature (e.g., Kinne, Reference Kinne2016; Thurner et al., Reference Thurner, Schmid, Cranmer and Kauermann2019). We identify how different arguments on arms trade in elite‐level political discourse reflect in the distribution of citizen preferences and the weights assigned to the arguments. Theoretically (García‐Alonso & Levine, Reference García‐Alonso and Levine2007) and anecdotally, we would, for example, expect that deontologist preferences are unlikely at the government levelFootnote 5 and that the weights that citizens attach to the economic, geo‐strategic and economic dimensions of arms trade differ from that of governments.Footnote 6

More broadly, our insights relate to a growing literature investigating heterogeneity in the preference formation processes of citizens. On the one hand, our results indicate that deontologist preferences could be an overlooked aspect of public opinion on foreign policy making, at least whenever deadly force is in question. On the other hand, our arguments and results are associated with recent findings in related areas where (domestic) economic benefits, security and normative considerations interact (albeit to varying degrees) – for example, decisions on military interventions (Dill & Schubiger, Reference Dill and Schubiger2021; Tomz & Weeks, Reference Tomz and Weeks2020), provision of foreign aid (Heinrich et al., Reference Heinrich, Kobayashi and Long2018), international trade (Lechner, Reference Lechner2016) or foreign direct investment (Rudolph, Kolcava, et al., Reference Rudolph, Kolcava and Bernauer2023).

In the next section, we delineate a theory of how arms transfer preferences of citizens are formed and how they might differ in two major European exporters. Then, we describe our empirical design including data collection and data analysis. The Conclusion section outlines the results regarding our major research questions. Finally, we conclude the article by highlighting especially its policy relevance.

Citizen's decision‐making on arms exports

Political economy models of state‐level decision‐making on arms exports explain decision‐making primarily on instrumental grounds, that is, they focus on the economic and geo‐strategic aspects of a trade (García‐Alonso & Levine, Reference García‐Alonso and Levine2007; Levine et al., Reference Levine, Sen and Smith1994). Normative aspects of a weapons trade, in particular, legal principles (e.g., the UN Arms Trade Treaty, the EU Council Decision (CFSP) 2019/1560, the German War Weapons Control Act), can additionally constrain exports, for example, to conflict zones or authoritarian regimes. How such legal principles come into being is not explained by these models themselves, and, usually, the relevance of normative aspects is conceived as only indirectly affecting the government calculus (via geo‐strategic interest, e.g., as arms trade can fuel internal conflict (see Pamp et al., Reference Pamp, Rudolph, Thurner, Mehltretter and Primus2018), which might lead to poverty, terrorism or migration flows) (Levine et al., Reference Levine, Sen and Smith1994). At the government level, this triad of aspects entails complex trade‐offs, where economically beneficial deals may be detrimental to a country's strategic objectives (e.g., when trading with unreliable partners) just as normative concerns may stand in the way of economically/strategically beneficial deals (e.g., when trading with human rights violating regimes).

But how do citizens assess the trade of arms? Recent scholarship has transcended the view that citizens' decision‐making is shaped exclusively by materialist considerations and has consequently expanded the foundations on which preferences form. This evolving literature shows, for example, that normative reasoning can shape public support for sanctions or even war (Onderco, Reference Onderco2017; Tomz & Weeks, Reference Tomz and Weeks2020); that the public cares about human rights violations in other countries, sacrificing domestic economic benefits to punish human rights violators (Allendoerfer, Reference Allendoerfer2017); and that citizens take into account non‐economic factors in trade preference formation (Kolcava et al., Reference Kolcava, Rudolph and Bernauer2021; Rudolph, Quoß, et al., Reference Rudolph, Quoß, Buchs and Bernauer2023). However, these findings are mostly motivated by a consequentialist calculus, where citizens form preferences over policies based on the effects they have. But citizens might also form preferences regardless of their consequences, that is, based on deontological motivations (Alexander & Moore, Reference Alexander, Moore and Zalta2021). While both motivations might lead to the same observed preference in any concrete case, their nature is very different – as evident in the contrast between Weberian Gesinnungsethik and Verantwortungsethik as the respective basis for political behaviour (Weber, Reference Weber1926). Hence, we aim to disentangle in the first step the prevalence of deontologist from consequentialist reasoning; only then can we, in the second step, theorize on the concrete trade‐offs that any actual arms trade might have, would it (not) be conducted; and develop, in the third step, arguments about potential differences by country contexts.

Deontological motivations

Take an exemplary trade that substantively raises the domestic economy, supports a strategic partner country and goes to a peace abiding, or even an aggressively attacked state. If the political economy literature has its assumptions right, and geo‐strategic, economic and normative concerns are the core determinants of utility functions, governments, just as well as citizens, should approve such a trade. Irrespective of whether their reasoning focuses on economic, normative or strategic arguments, this trade should be maximizing their utility.

But citizens (and politicians) may be fundamentally opposed to any arms transfer for principled reasons, viewing any transfer of weapons as an unconditional bad.Footnote 7 For example, radical pacifist views would fall in this category (Cady, Reference Cady2010). Radical pacifists would see any violence as inappropriate, that is, as an immoral mean, irrespective of the ends this mean is to support. As any trade of arms would enable such violence, it is rejected. Such motivations are the most plausible source of principled opposition in our case: in (European) political discourse, they are prominently voiced by civil society organizations connected to the peace movement and pacifist advocates (e.g., Holden, Reference Holden2017).

Importantly, pacifism is not the only possible foundation for principled opposition (e.g., isolationists might similarly reject any transfer) and the grounds on which principled opposition is based likely differ by country contexts. Rathbun and Stein (Reference Rathbun and Stein2020) make the compelling argument that morality and egoism should not be conflated with deontological and consequentialist decision‐making – either mode of decision‐making can be based on moral reasoning. But we argue that it is important to know about the size of principled preferences, as such citizens put stronger constraints on governments. Consequentialists support the transfer of arms under specific context conditions – which changes the nature of the game to one of policy design (e.g., Bechtel et al., Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit2017) and persuasion (e.g., Gadarian, Reference Gadarian2010) to bridge potential gaps between elite and population preferences (Smetana & Onderco, Reference Smetana and Onderco2022). A relevant share of deontologists, however, decreases the manoeuvrability of governments (Zhang, Reference Zhang2019). Additionally, we propose that deontologist citizens are likely to attach higher importance to party positions in this area and are hence more likely to hold political parties to account for their policy (Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty and Dowling2011).

So far, the prevalence of fundamental convictions has rarely been invoked to explain the structure of citizens' foreign policy preferences.Footnote 8 As a first goal of this article, we will therefore identify the extent to which opposition ‘per se’ prevails in mass public preferences regarding arms transfers. On the aggregate level, the share of citizens that follow such preferences could thus be indicative of challenges to an instrumentally oriented government strategy for reasons of democratic accountability.

Economic, strategic and normative dimensions of arms trades and their weight in a consequentialist calculus

Citizens that follow a consequentialist calculus attach individually varying weights to the likely consequences of weapon deals for the sending and receiving country. We, therefore, assess, as a second goal of this article, the relative weight of three core dimensions (see also Dill & Schubiger, Reference Dill and Schubiger2021), economic, strategic and normative consequences of an arms trade.

If citizens give large weight to the economic dimension, the welfare consequences of arms exports (job market/income consequences) should strongly determine public preferences. As the immediate welfare consequences of an arms trade are readily observable and have direct positive consequences for the domestic economy, economic attributes of arms trades provide easy‐to‐follow guidance when forming decisions. We propose that utility maximization should entail a strict increase of approval for arms transfers with increasing economic benefits, all else equal.

If citizens give large weight to geo‐strategic interests, they should take into account the potential security implications of an arms deal. Just as in a government's optimization problem, arms deals can be considered harmful or beneficial to a country's long‐term security environment, depending on whether a trade supports allies or adversaries (García‐Alonso & Levine, Reference García‐Alonso and Levine2007). As these security implications are not easily observable, citizens and even political elites have to follow cues provided by attributes of the receiving country. First and foremost, trade with geo‐strategic partners should be considered beneficial, as this trade comes about with positive security externalities for the sending country. If citizens give large weight to this dimension, we should observe higher support for trade with such geo‐strategic partners.

Last, if citizens give large weight to the normative dimension, we propose that the consequences of an arms trade for the receiving country are at the centre stage of considerations.Footnote 9 These normative considerations are steered by legal considerations and moral dilemmas. Contrary to principled opposition, the likely effects of weapons trades are considered. On the basis of hypothetical imperatives, citizens would form preferences over arms trades based on their effects (Chen & Schonger, Reference Chen and Schonger2022). Citizens would differentiate whether arms will likely be used to repress a population (compared to upholding a lawful state monopoly of power) or whether arms are employed for rightful defensive or unlawful offensive purposes (Bellamy, Reference Bellamy2006). Theories of just war (Cady, Reference Cady2010) would argue that the use of violence, and thereby arms trade, may be morally acceptable or even required if it serves rightful ends – three attributes of receiving countries are easily observable for citizens and informative in this respect: the receiving country's regime characteristic, especially if it is a democracy; its human rights situation; and whether it is currently engaged in violent conflict. Arms exports should fall under rightful ends if they support democratic and human rights upholding regimes (as an indication that arms are used to ensure a lawful state monopoly of power rather than to oppress) and should be approved where they support justified violence, particularly defence against terrorists, rebels or foreign state aggression.

We will apply a research design that forces citizens to form decisions that reveal trade‐offs between these three dimensions. Psychological literature points to the ease of attitude accessibility (Krosnick, Reference Krosnick1989) to explain which aspects guide decision‐making: questions of war and peace, human rights violations, or autocratic leadership all relate to fundamental principles of social life and are both easy to understand and important to many citizens. Hence, the normative dimension relates to networks of frequently accessed attitudes in memory; also, such questions of war and peace or human rights directly relate to emotions, which are particularly accessible (Rocklage & Fazio, Reference Rocklage and Fazio2018). High attitude accessibility, in turn, would explain a large weight of this normative dimension in decision‐making. This could also come about as the strategic aspects of an arms trade are not easily observable for citizens, and as the economic aspects are detached from the day‐to‐day life of citizens (leading to low egotropic motivations) – and even if sociotropic motivations were strong (but see Schaffer & Spilker, Reference Schaffer and Spilker2019), these sociotropic motivations are likely discounted due to the low absolute share the arms industry holds in Western economies.Footnote 10

However, we also expect that the weight of economic, strategic, and normative aspects is influenced by the presence or absence of moderators, that is, the relevance of these dimensions can be activated by specific attribute configurations. This relates to the question of how stable the decision calculus of citizens is, and whether the weight of the three dimensions varies by context conditions. Concretely, we investigate how five aspects affect the relative weight of normative, economic and geo‐strategic attributes: first, the influence of international supply competition over market shares, which is a strong determinant of non‐Pareto‐efficient outcomes in political economy models (García‐Alonso & Levine, Reference García‐Alonso and Levine2007); second, economic interests as a mediator for the relevance of normative arguments, as proposed in the foreign aid literature (e.g., Heinrich et al., Reference Heinrich, Kobayashi and Long2018); third, wars of rightful regimes as a use of force more likely to be legitimate compared to wars of oppressive regimes; fourth, higher caution in trade approval when the military equipment to be traded is more lethal (Cady, Reference Cady2010); and fifth, whether exports to geo‐strategic partners find higher approval when these are democracies (who likely are more reliable) (Johns & Davies, Reference Johns and Davies2012). In sum, this will inform on the one hand to what extent the basic citizen calculus differs from standard political economy models directed towards strategic aspects and the economy, by prominently incorporating now a normative dimension. On the other hand, the question on moderators will be indicative of the reactivity of public opinion with respect to arms transfers given particular nuanced side constraints for decision‐making.

German–French differences

As a third goal of our article, we investigate to what extent both deontologist motivations and the consequentialist calculus differ between country contexts. For this, we draw on Germany and France as divergent cases, with an anti‐militarist and restrained foreign policy culture in post‐war Germany following the experience of World War II (Endres, Reference Endres2018, 51ff.), and with French political culture striving for international ‘rang’ (rank) and ‘grandeur’ (greatness) (see, e.g., Krotz, Reference Krotz2015, 68ff.), where the military, the use of military force as well as the national arms production have high legitimacy (Krotz, Reference Krotz2015, 114ff.). We expect that German citizens show relatively less support for weapons deals on average, are more likely to exhibit deontologist preferences and react more strongly to norm‐related dimensions. This would provide a case in point that public opinion constrains governments' arms trade behaviour to a differing extent based on deep societal preferences.

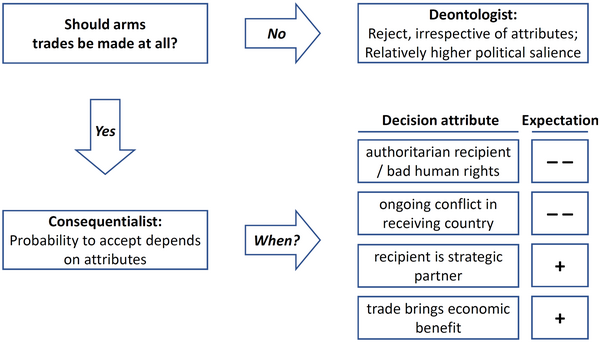

Figure 1 provides a summary of the expectations outlined so far.

Figure 1. Summary of theoretical expectations. + (−−) indicates the expected positive (strong negative) relation between the expression of a decision attribute on a citizen's approval of an arms trade. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Research design

The following section presents our research design. Online Appendix B discusses differences to the pre‐analysis plan.

Data and survey design

Drawing on a population‐representative quota sample of 6617 respondents from Germany (

![]() $N$ = 3250) and France (

$N$ = 3250) and France (

![]() $N$ = 3367) (field time October 2020–January 2021) with Kantar's opt‐in online panel, we fielded standard survey questions as well as conjoint and vignette survey experiments. We set quotas on age, education, gender and region.Footnote 11 Our procedure and the survey instrument were approved by the Ethics Commission of the Social Science Faculty of LMU Munich. Online Appendix section A.3.1 details how we adhered to core Principles for Human Subjects Research.

$N$ = 3367) (field time October 2020–January 2021) with Kantar's opt‐in online panel, we fielded standard survey questions as well as conjoint and vignette survey experiments. We set quotas on age, education, gender and region.Footnote 11 Our procedure and the survey instrument were approved by the Ethics Commission of the Social Science Faculty of LMU Munich. Online Appendix section A.3.1 details how we adhered to core Principles for Human Subjects Research.

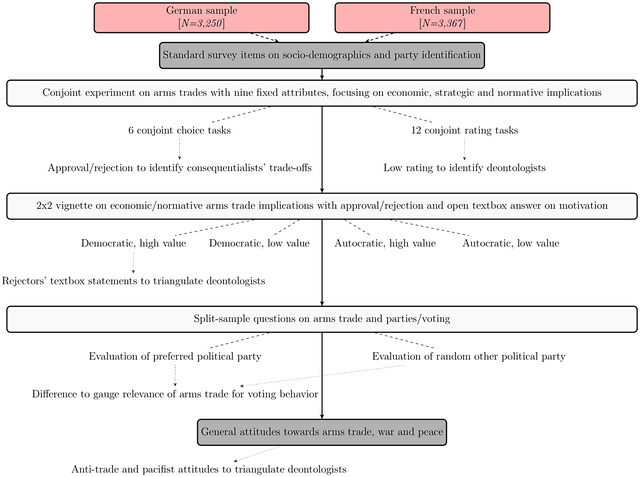

Figure 2 presents the survey flow. Respondents started with standard survey questions on socio‐demographics and political attitudes, before entering the core of our research design, the conjoint experiment. For this, we introduced respondents to a scenario in which they were to assess two hypothetical arms transfers (profiles), taking care to avoid any positive or negative framing effects when introducing the topic. Two profiles were presented in a tabular format, side‐by‐side, differing along nine theoretically chosen attributes with two to five uniformly randomized attribute levels (details on attributes and levels in the next subsection). Respondents then faced six choice and rating tasks (see Online Appendix Figure A.2 for an example). We use the rating task for our first objective – assuming that deontologist respondents rate even the most favourable profile lowly and provide low ratings throughout all 12 rating tasks. We use the choice task for our second objective – to identify the weights and trade‐offs of a consequentialist calculus. We hence work with

![]() $N \cdot 6 \cdot 2=79,404$ observations on the profile level. Extensive pre‐registered power simulations (Schuessler & Freitag, Reference Schuessler and Freitag2020) motivated this sample size.

$N \cdot 6 \cdot 2=79,404$ observations on the profile level. Extensive pre‐registered power simulations (Schuessler & Freitag, Reference Schuessler and Freitag2020) motivated this sample size.

Figure 2. Survey flow. Presented are question blocks used for the analyses in this article. For details, see the pre‐registered survey instrument. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

As low ratings could also be driven by consequentialist rejection, that is, respondents not seeing what they personally would deem a favourable context beyond our choice of attributes and attribute values, or just by random noise, we triangulate deontologist motivations with additional survey items. The key for this is, first, an experimental vignette (Mutz, Reference Mutz2011) focusing on the trade‐off between large/small economic gains and a human rights abiding democracy versus a human rights violating autocracy in a 2 × 2 design. Respondents had to explain their motivation for (dis)agreement with at least two sentences in a text box. Respondents had to enter text to proceed with the survey. We used respondents that rejected a ‘favourable’ vignette (democracy/high value) and traced whether they voice deontologist motivations in their open‐ended justifications. Second, we use replies to a standard survey item battery on general attitudes towards arms transfers, expecting deontologists to perceive arms trade as ‘morally bad’, ‘not permissible’ even under favourable conditions and ‘to be restricted’ in principle. Online Appendix section A.4 provides details. Third, we expect deontologists to have difficulties in the choice task – hence, we investigate whether their choices are attenuated towards zero in the conjoint experiment (see below). Overall, we propose that this triangulation provides a sensible approximation to a hard‐to‐measure subgroup.

In a final experimental question, we also investigate the importance of arms transfers for respondents' voting behaviour with a split‐survey experiment, to assess our expectations that the position of political parties on arms trade is more important for deontologist respondents. Our survey also contained several standard survey items on preferences towards war and peace (Bizumic et al., Reference Bizumic, Stubager, Mellon, Linden, Iyer and Jones2013).

As speeding and satisficing are well‐known issues in online surveys, the survey company excluded respondents faster than 40 per cent of the median survey time during data collection.Footnote 12 Further problematic cases (especially straight‐liners and super‐speeders in standard item batteries or super‐speeders in all conjoint tasks) were also excluded.Footnote 13

Set‐up of the conjoint experiments

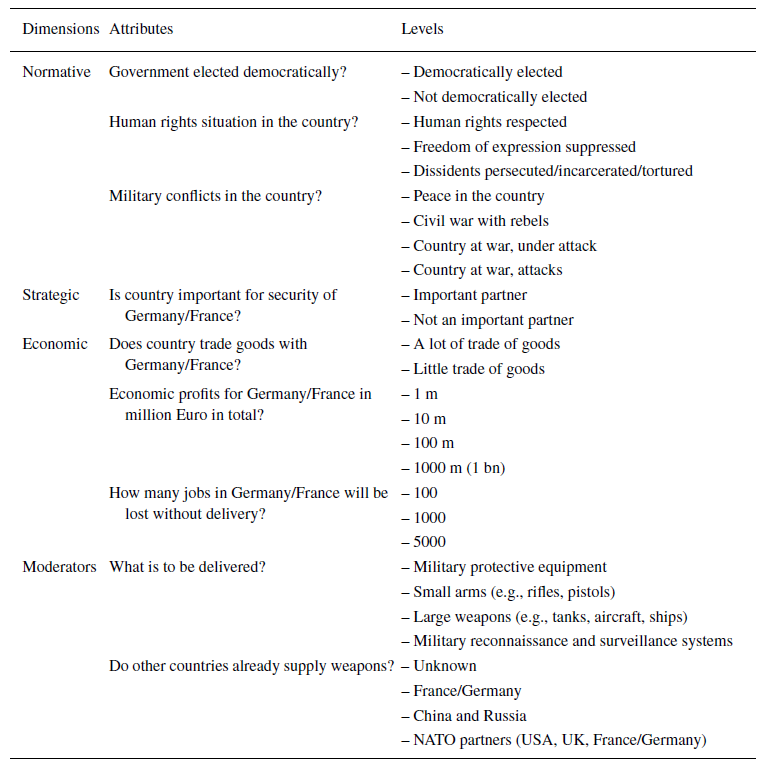

To operationalize the trade‐offs that consequentialist respondents face, we selected nine attributes (summarized in Table 1). These attributes mimic typical aspects present in public discourse; hence, the information is actually available to citizens. This also implies that economic consequences are rather concrete (monetary value/employment benefits), while normative/strategic implications are rather abstract and proxied by target country characteristics. Concerning attribute levels, we focus on the range of observable values for these attributes to present respondents with realistic trade‐offs and to speak to actual arms trade policy.

Table 1. Dimensions, wording of attributes and levels for the conjoint experiment

Note: English translation of the conjoint attributes and levels. For original wording see master questionnaire.

Details are presented in Online Appendix section A.5. In short, we translate the economic dimension into three aspects: gross welfare added (range: observed exports in 2019); employment consequences (negligible to 5000, a medium‐sized firm); exports to an important trade partner (yes/no). We translate the strategic dimension of arms trading to negative/positive security externalities, which link to alliance status. We capture this by a security partnership between seller/target (yes/no). Concerning the normative dimension, global regulatory commitments highlight regime type (democratic vs. non‐democratic), human rights situation ((no) (strong) violation of human rights) and conflict status of the target country (five common types). We present two more attributes as potential moderating factors: the product to be traded (defensive equipment to large‐scale weapons), which also prevents respondents from inferring weapon type and its harm potential from the monetary value of the deal; and international competition (‘unknown’ vs. allies vs. rivals trading). We explicitly stay silent on the country that is to be traded with, to avoid unrealistic profiles and idiosyncratic country perceptions affecting preference formation.

Attributes are presented in block‐random or random order, constant within respondent (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Freitag and Thurner2022). Online Appendix section A.6 provides details on our estimation strategy, which draws mainly on average marginal component effects (AMCEs) (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). This allows us to focus on marginal shifts in overall public opinion with changes in attribute levels. We also estimate marginal means (MMs) and average component effects (ACPs) as suggested by recent methodological research (Ganter, Reference Ganter2023; Leeper et al., Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020).

Results

Deontologist motivations

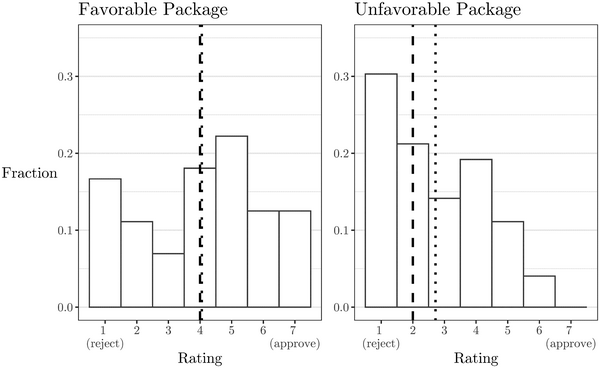

We start with an indication of baseline preferences on arms deals. To this end, we turn to the average ratings of respondents in the conjoint experiment. Over all packages, support on the seven‐point rating scale is at 3.23 with a median of 3. Defining a rating of 4 and above as (tentative) approval, a majority of the arms trades we presented to respondents would therefore be rejected.

However, ratings are very heterogeneous. Particularly, we detect around 10–15 per cent of respondents exhibiting deontologist motivations. As outlined in the Data and survey design section, we derive this estimate with two approaches. First, we identify a highly favourable arms trade package in the conjoint experiment, contrasting this with an unfavourable package. As presented in Figure 3, the distribution of the respective ratings differs starkly. Whereas a favourable package sees a mean of slightly above four, as well as a median of four, an unfavourable package sees a median of two and a mean of 2.7. This implies that the median citizen can become favourable with respect to arms deals in specific situations on an absolute scale. But this also indicates that most arms deals, even if preferred under a forced choice design, see absolute ratings below a median of four, that is, are assessed as unfavourable. Notably, a sizable share of the population (15 per cent) is strictly opposed even in a very favourable scenario, indicating principled opposition.Footnote 14

Figure 3. Distribution of support for an (un)favourable package. N = 72 (left panel)/99 (right panel). The dotted (dashed) line indicates the mean (median). A favourable package is defined with the following attribute levels: democratic; human rights upheld; no (civil) war; trade/security partner; high/medium monetary/employment benefit; defensive weapons traded; NATO/FR/GER also trading. An unfavourable package is the inverse of this list.

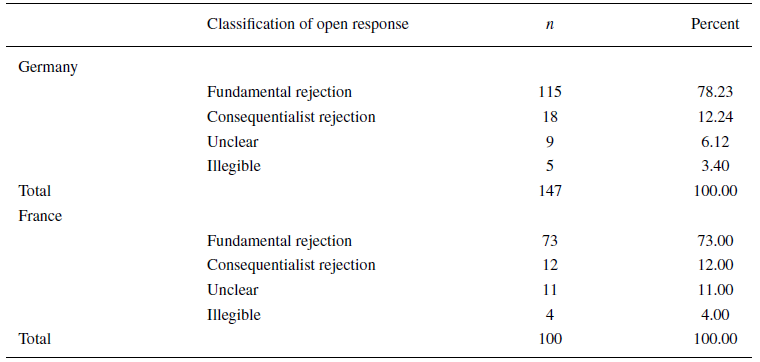

Second, we focus on the set of respondents rejecting all choice tasks, irrespective of attribute configuration, and an additional rejection of arms trades in a favourable textual vignette (15 per cent of respondents, 13 per cent in France and 21 per cent in Germany). We term this group ‘rejectors’. These ‘rejectors’ potentially are an upwardly biased estimate of deontologists respondents might have a threshold for approving arms trades not captured by our scenario or respondents might, randomly, not have seen profiles they would accept. Hence, we triangulate the extent to which these rejectors actually hold deontologist preferences by way of stated motivations in open‐ended survey responses and respondents' general attitudes towards arms transfers and war and peace.

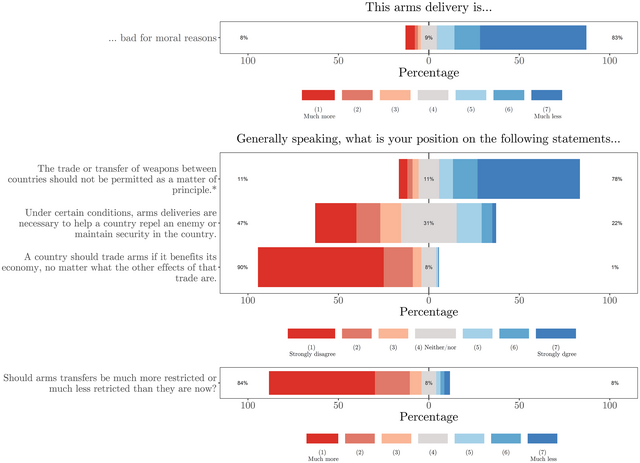

Table 2 indicates that among the 15 per cent of rejectors, around 75 per cent voiced clear deontologist motivations in the open‐ended survey question. Hence, open responses would suggest a lower bound of 188/1654 = 11.4 per cent deontological respondents (9.7 per cent in France and 16.1 per cent in Germany). We might even miss some respondents with principled opposition that respond with unclear statements in the open‐ended question. We further validate this finding by assessing the general attitudes of these respondents towards arms transfers. Figure 4 shows that among rejectors, only a small minority of 1–11 per cent would agree to statements that deontologists should reject. A similar picture emerges from rejectors' replies to a battery of items on general attitudes towards war (see Online Appendix Figure A.3).

Table 2. Classification of open text answers for rejectors

Note: Rejectors defined as respondents with max. rating 3 in all twelve conjoint tasks plus rejection of textual vignette. Experimental subset of respondents who saw a positive vignette used (247/1654 = 14.93 per cent of respondents). Hence, open responses would suggest a lower bound of 188/1654 = 11.37 per cent deontological respondents. When defining rejectors as respondents with max. rating 1 in all twelve conjoint tasks, this lower bound is approx. 7 per cent.

Figure 4. Responses to general attitudes towards arms transfers for rejectors in the conjoint rating tasks. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Overall, this points to a share of deontologist respondents of around 10‐15 per cent, indicating that a substantial part of the population is in fundamental opposition to weapon transfers.

How norms, economic and strategic aspects influence preference formation

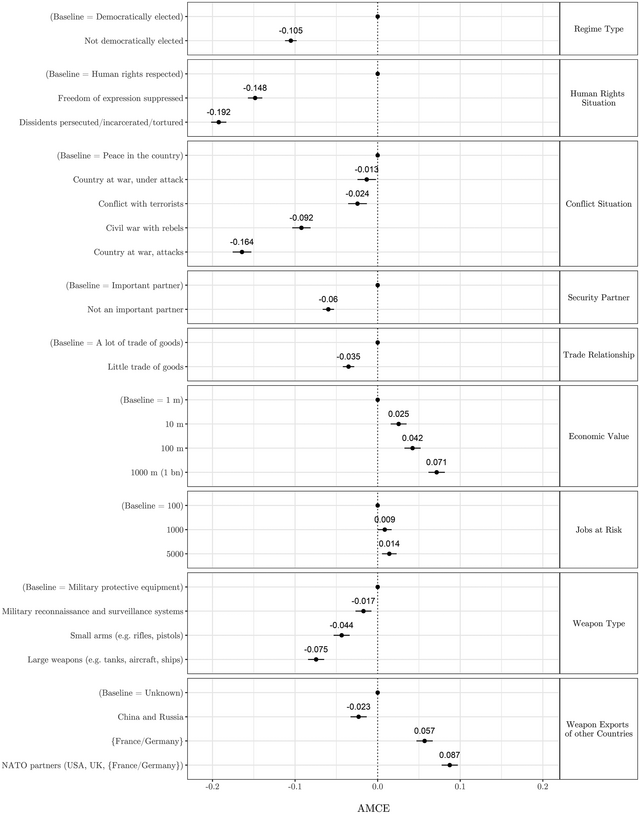

Next, we turn to the causal effect of specific attribute levels on the probability of choice in the choice task using AMCEs.Footnote 15 The counterfactual comparison refers to level changes within a profile (Bansak, Reference Bansak2021). As AMCEs are estimated on the same scale, they are substantively comparable, yet bounded by the number of levels (Ganter, Reference Ganter2023; Leeper et al., Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020). Therefore, inter‐attribute comparisons have to be conducted with some care. As a rule of thumb, one can multiply AMCEs by the number of levels of the attribute

![]() $l$ divided by (

$l$ divided by (

![]() $1-l$). In our case, this does not change interpretations substantially; hence, we can infer the relative importance of attributes directly from the relative size of AMCEs.

$1-l$). In our case, this does not change interpretations substantially; hence, we can infer the relative importance of attributes directly from the relative size of AMCEs.

Figure 5 first presents the attributes of the normative dimension: An arms transfer to an autocratic (compared to a democratic) regime decreases support by

![]() $-0.105$, that is, around 11 percentage points, on average. A similar difference becomes evident for the state of human rights: compared to no violations, (strong) violations cause an average decrease in choice probability of

$-0.105$, that is, around 11 percentage points, on average. A similar difference becomes evident for the state of human rights: compared to no violations, (strong) violations cause an average decrease in choice probability of

![]() $-0.148$ (

$-0.148$ (

![]() $-0.192$), that is, we see a penalty up to 20 percentage points for such unfavourable contexts. Turning to the conflict situation, and compared to a country at peace, an arms export to a country at war that acts aggressively leads to a decrease in the acceptance of such a transfer by around 16 percentage points (

$-0.192$), that is, we see a penalty up to 20 percentage points for such unfavourable contexts. Turning to the conflict situation, and compared to a country at peace, an arms export to a country at war that acts aggressively leads to a decrease in the acceptance of such a transfer by around 16 percentage points (

![]() $-0.164$). For countries at civil war with rebels, the effect is roughly half the size. Although negative in direction, and significant, the effects of countries defending themselves against an aggressor or a terrorist group are, in line with expectations, much smaller. This already indicates that weapons deals are not substantially penalized when used for ‘just’ causes – but notably, we also do not see that respondents take such ‘just’ causes as an indicator that weapons should be traded. Turning to the economic dimension of arms trades (compared to lowest levels), very high monetary values increase support substantially by around 7 percentage points (

$-0.164$). For countries at civil war with rebels, the effect is roughly half the size. Although negative in direction, and significant, the effects of countries defending themselves against an aggressor or a terrorist group are, in line with expectations, much smaller. This already indicates that weapons deals are not substantially penalized when used for ‘just’ causes – but notably, we also do not see that respondents take such ‘just’ causes as an indicator that weapons should be traded. Turning to the economic dimension of arms trades (compared to lowest levels), very high monetary values increase support substantially by around 7 percentage points (

![]() $0.071$). The number of jobs at risk exerts a positive, albeit substantively small effect on the average acceptance of an arms transfer, by around 1.5 percentage points (

$0.071$). The number of jobs at risk exerts a positive, albeit substantively small effect on the average acceptance of an arms transfer, by around 1.5 percentage points (

![]() $0.014$). On average, respondents, therefore, do not seem to give the job argument, oftentimes referenced in public debates, much weight in their calculus. Lastly, respondent support increases more strongly with trade with important trade partners, by around 4 percentage points (

$0.014$). On average, respondents, therefore, do not seem to give the job argument, oftentimes referenced in public debates, much weight in their calculus. Lastly, respondent support increases more strongly with trade with important trade partners, by around 4 percentage points (

![]() $0.035$, compared to not important). Turning to the security dimension of arms trades, respondents also react in a relevant way to trade with important security partners by 6 percentage points (

$0.035$, compared to not important). Turning to the security dimension of arms trades, respondents also react in a relevant way to trade with important security partners by 6 percentage points (

![]() $0.06$, compared to not important). Lastly, we interpret the main effects of two moderators, weapon type and international competition. A change in weapon type from large or small weapon systems to weapon systems with indirect harm potential (surveillance technology/protective equipment) increases average support (the penalty for large weapons systems is around 8 percentage points (

$0.06$, compared to not important). Lastly, we interpret the main effects of two moderators, weapon type and international competition. A change in weapon type from large or small weapon systems to weapon systems with indirect harm potential (surveillance technology/protective equipment) increases average support (the penalty for large weapons systems is around 8 percentage points (

![]() $-0.075$)). Moreover, providing information on which countries already supply weapons (baseline: ‘unknown') increases support with allied states trading (

$-0.075$)). Moreover, providing information on which countries already supply weapons (baseline: ‘unknown') increases support with allied states trading (

![]() $0.084$ with NATO partners) and decreases support with adversaries trading (

$0.084$ with NATO partners) and decreases support with adversaries trading (

![]() $-0.023$).

$-0.023$).

Figure 5. AMCEs for the choice task.

Overall, it becomes evident that arms exports see substantively and significantly higher support when alleviating potential normative concerns, with non‐linear, disproportionate increases in choice probabilities when human rights are fully upheld, and when the fighting context is terrorist combative, defensive or peaceful. While economically and strategically beneficial attribute values also see an increased choice probability, respondents react less strongly to these dimensions. The data hence support our theoretical expectation that normative, economic and security‐related considerations shape preferences for arms trade – but most influential is the normative dimension. Changes in the pattern of ratings are very similar (see Online Appendix Figure A.5). We also reach similar conclusions when interpreting average component preferences that more directly allow for inter‐attribute comparisons of preferences (Ganter, Reference Ganter2023) (see Online Appendix Figure A.6).

Last, we discuss how deontologist versus consequentialist respondents reply to the choice task (see Online Appendix Figure A.7). We expected that deontologists consider information on the implications of arms transfers to a lesser extent (or not at all), hence react less to the conjoint experimental stimuli in the forced‐choice setting, and, if at all, react to the normative dimension. This is also what we find: Choices of deontologist respondents are dampened compared to consequentialists. For economic and strategic aspects they are attenuated to zero or close to zero, for the normative dimension deontologists respond with a comparable, though attenuated pattern. This also implies that all our conclusions for the discussion of AMCEs above hold for consequentialist respondents.

Trade‐offs in the calculus

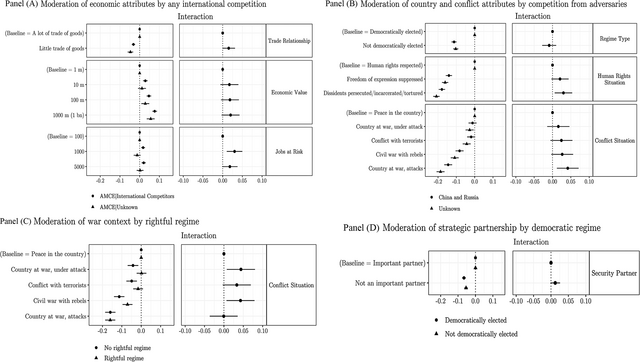

We now turn to the question of whether the specific contextual setting of an arms transfer moderates the observed effects.Footnote 16

Concerning international supply competition, we find that this enhances the weight of economic and strategic arguments. With any other country supplying weapons to the target country (see panel A of Figure 6), transfers to commercial trade partners (p = 0.061), high‐value deals (p = 0.082) and medium‐ to high‐employment deals (p = 0.003/p = 0.066) see higher levels of support. While small in absolute magnitude, interaction effects are around one third of the main effects for trade partnership and monetary value and only seem to show up at all under competition for employment effects. With adversaries supplying weapons to the target country (see panel B of Figure 6), support for arms transfers to unfavourable contexts becomes more likely. While autocratic regime type is assessed similarly negative in both scenarios, moderate (p = 0.083) and severe human rights violations are more likely accepted (p = 0.014), as is intra‐state (p = 0.081) and aggressive inter‐state war (p = 0.006). Again, effects are absolutely small but meaningful in relative terms: we see a reduction of the penalty for human rights violations of around 14 per cent and the penalty for inter‐ or intra‐state war of around 22 per cent. Concerning the question of whether positive economic consequences of arms deals dampen the relevance of adverse normative contexts, we do not find any evidence (see Online Appendix Figure A.8): AMCEs differ only marginally, and war situations (compared to peace) are even more detrimental to choice with high economic value. Concerning the question of whether trade with rightful regimes (defined as human rights upholding democracies) in war is more likely to be supported compared to trade with oppressive regimes in war, we find support. As already discussed above, trade to war contexts see a much higher choice probability if they are defensive compared to offensive, with a substantial difference in choice probabilities of around 15 percentage points. As well, when weapons likely support a rightful state monopoly of power (see panel C of Figure 6), defensive war contexts (p = 0.018) and target countries in conflict with terrorists (p = 0.072) no longer receive a meaningful penalty, while the penalty for civil war contexts decreases (p = 0.020) by 38 per cent. Notably, we observe no change in preferences for aggressive inter‐state wars comparing rightful and unrightful regimes. Last, as can be seen from Online Appendix Figure A.9, respondents become more cautious to approve trade with countries in conflict when the military equipment to be traded is more lethal. Altogether, this indicates that citizens’ decision‐making along the normative dimension is influenced by considerations of just war theory, that is, right cause, right authority and proportionate response (Cady, Reference Cady2010). Finally, we investigate an implication of democratic peace theory: indeed (see panel D of Figure 6), trade with strategic partners exhibits higher choice probabilities (22 per cent of main effect), when these partners are democracies (p = 0.086).

Figure 6. Four tests for interaction effects: AMCEs and AMCIEs for attributes listed by the moderator indicated in panels A–D.

In summarizing these findings, we conclude that relevant moderations of decision attributes appear and that (besides no evidence for economically beneficial contexts alleviating normative concerns) the weight of the economic, strategic and normative dimensions can be activated by contextual factors. This highlights that, even if the normative dimension seems to drive preference formation on aggregate, citizens show a very nuanced calculus concerning arms trade.

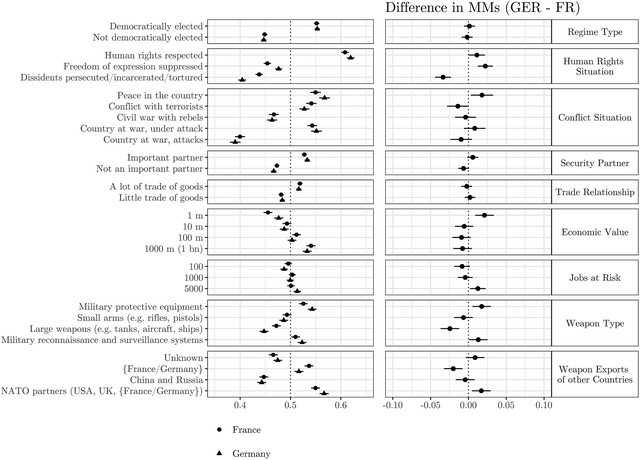

German–French differences and policy relevance

Lastly, we assess whether German and French respondents show different preference structures and discuss why this might be relevant for the decision‐making of governments. To start with, respondents from Germany and France show nuances in their average response to the conjoint experiment. Figure 7 presents MMs by country for the choice task (see Online Appendix Figure A.11 for AMCEs). This reveals first of all that the general pattern of preferences is similar in both countries. Second, however, German respondents take severe human rights situations more strongly into account, have a stronger preference for peaceful contexts (and are less supportive of ‘wars on terror'), react weaker to the monetary value of the deal (although slightly stronger to employment benefits), have a stronger distaste for large weapons and react more strongly to NATO compared to French co‐deliveries. Overall, German respondents, therefore, show, on average, a more sensitive reaction to characteristics of the target country and the nature of the deal (i.e., to ‘good’ vs. ‘bad’ deals for the recipient population) and less reaction to economic co‐benefits. This goes hand in hand with an, on average, more sceptical rating of arms deals in Germany compared to France (see Online Appendix Figure A.10). For all displayed profiles, German respondents assess arms trades with a mean of 3.05 and median of 3 (i.e., rejection), French respondents with a mean of 3.40 and median of 4 (i.e., tentative acceptance). Correspondingly, 29 per cent (21 per cent) of displayed arms trades are vividly rejected by German (French) respondents (rating of 1), and 59 per cent (49 per cent) see a clear rejection with a rating below the scale mid‐point in Germany (France).

Figure 7. Marginal means by country and country difference for all attributes.

Why does this matter? As we argue, the German public seemingly has a different structure of disapproval, making it difficult to find common grounds for arms exports on French terms. To provide an indication for this, we investigate the distribution of ratings for arms trade profiles crossing over a favourable versus unfavourable governance and conflict context and a high versus a low economic value of a trade. As indicated by Online Appendix Figure A.12 (upper four plots), the share of respondents that are fundamentally opposed to an arms trade (rating of 1) is substantially higher in Germany when the trade goes to an unfavourable governance and conflict context: 20 percentage points higher with low economic value, and 7 percentage points higher with high economic value. Similarly, even arms trade to good governance contexts at high economic values see fundamental opposition from around 23 per cent of German, but only 13 per cent from French respondents. Hence, while median support for arms trade aligns in both countries with a good governance and conflict context (at 4), it differs substantively when the governance and conflict situation is bad (by one scale point, 2 in Germany vs. 3 in France). Thus, opposition to bad governance and conflict contexts is much more pronounced in Germany. This consequently reflects in the predicted ratings for specific realistic arms trade scenarios, where France and Germany might have to coordinate government policy. As displayed in Online Appendix Table A.5, with unfavourable governance and conflict situations predicted support is substantively lower in Germany compared to France: around 0.7 rating points with a low‐value transfer (example of Azerbaijan) or around 0.6 rating points with a high‐value transfer (example of Saudi Arabia). Support is only comparable once the governance and conflict situation is positive (see examples of Costa Rica and France/Germany). Hence, public opinion constrains the menu of acceptable arms trades more strongly in Germany compared to France.

Also, the share of deontologist respondents is substantively larger in Germany (14–16 per cent) compared to France (7–10 per cent) (see the results presented in the Deontologist motivations section). This is an additional potentially relevant constraint to the German compared to the French government. We proposed in the theory section that principled opposition should reflect more strongly in citizens’ political decision‐making. To test this empirically, we provide supplementary analyses in Online Appendix Table A.6. We asked respondents about the importance of party positions on arms trade for their election decision, experimentally varying whether they reply for the electoral importance of the position of their (on other grounds) preferred party versus any other party. Respondents that evaluate their preferred party unsurprisingly attach substantively and significantly higher issue importance (around 0.5 points on a five‐point scale). Contrasting replies to this question by deontologist versus consequentialist respondents, we find that deontologists attach even more importance to arms trade in decision‐making (by about 0.2 scale points), with an additional premium if the question concerns their preferred party on other grounds (by about 0.5 scale points). This indicates that deontologists constrain government manoeuvrability not only because of firm policy views but also because they are more likely to hold parties to account for policy diverging from their preferences in practice. Of course, we can expect these constraints to vary by the partisan composition of governments and the respective share of deontologists among these parties' supporters (see Online Appendix section A.7.6 for tentative evidence that deontologist preference structures are more prevalent among respondents with a far‐left or green party vote intention).

All in all, we conclude that German respondents are more caring for the normative context in target countries, react less positively to its economic benefits and that a larger share of German respondents is in fundamental opposition compared to French respondents. Respondents in principled opposition attach higher importance to the policy issue, which implies likely stronger constraints for the German government overall. In a German–French cooperation in the realm of defence, the German population could, hence, prove to be a bottleneck and cooperation might only be possible on German terms – if France is willing to accept these.

Conclusion

If the frequently implored European defence and security policy should ever realize, high up on the EU agenda after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022,Footnote 17 France and Germany are ‘bound to lead’ (Nye, Reference Nye1990) together. This implies that not only the respective EU member states' elites but also their public support such strategic alliances and agree on a common denominator with respect to security policy, including arms exports. The struggle to find common ground concerning arms transfers to Ukraine among EU and NATO countries both before and after the Russian invasion in 2022, accompanied by heated public debates, provides a case in point for the challenges this entails.

In this article, we explored this common ground from a public opinion perspective, focusing on the German and French public. So far, little to nothing is known about mass public preferences for arms exports. Experimental studies on attitudes towards this foreign policy issue do (to our knowledge) not exist for these two countries, nor any other country worldwide. Using conjoint and vignette experiments, we investigated the extent of principled opposition to any arms trade, and the weight of three core dimensions, normative, economic and strategic aspects, for citizens' opinion formation. Respondents in both countries give largest weight to the normative implications of arms exports, while also taking the economic and strategic aspects of a deal into account. Also, respondents react in nuanced ways to side constraints that can further exports (e.g., when supporting defensive wars or trading in a competitive environment), even if a majority of respondents is rather sceptical. However, a larger share of respondents is in fundamental opposition towards arms exports in Germany and exports to autocratic, human rights abusive or conflict‐prone contexts find stronger opposition in Germany compared to France. Hence, we find some signs of a cross‐country divergence in average preferences between the publics. Overall, the German government is likely constrained to a larger extent by its public and joint action seems feasible rather on German than French terms.

These findings have clear policy relevance: the specific circumstances of an arms transfer can induce substantial swings in public support. For example, our experiment indicates (tentative) approval ratings for about 65 per cent of respondents, and opposition for about 35 per cent of respondents in a post‐invasion Ukraine‐type situation (see Figure 3), corresponding closely to what we see in real‐world public opinion polls on the matter (see Online Appendix section A.1). While (tentative) approval to trade in such ‘positive’ scenarios is similarly high in both France and Germany, support in Germany (but not in France) drops strongly if conditions are less ‘positive’ (e.g., comparing a pre‐invasion Ukraine scenario, where the country is at civil war). We take this as an indication that our experiment, fielded in a period of peace in Europe in late 2020, is doing well in identifying a preference structure relevant also for extreme scenarios, and hence has high external validity. Consequently, Online Appendix A.7.2 presents further illustrations of the bounds of support based on predicted ratings, contrasting packages that correspond to concrete country examples. They indicate that a favourable context in the normative as well as strategic and economic realms seems to need to come together for public acceptance of an arms trade on average. Altogether, the upper bound of support for arms transfers appears to be rather low in general and even lower in Germany compared to France. At the same time, our findings are both in line with the assertion of different strategic cultures in Germany and France (Endres, Reference Endres2018; Irondelle et al., Reference Irondelle, Mérand and Foucault2015), and with the anecdotal evidence of a strong public backlash against morally repulsive, even if economically and strategically beneficial, arms deals. Based on the cross‐country differences we observe, it seems plausible that the societal ‘strategic cultures’ of Germany and France differ to an extent that in any cooperation the countries are constrained by their respective publics to a lowest common denominator in arms export policy (Putnam, Reference Putnam1988) – which here is the restrictive German approach to the trade of arms. These results also hold lessons for the feasibility of an EU‐wide arms export control policy and can contribute to explaining why these are ‘in crisis’ (Wisotzki & Mutschler, Reference Wisotzki and Mutschler2021). As arms exports are just one facet of a joint European security and defence policy, our results highlight broader challenges for policy design in this regard: a far‐reaching unified European defence policy seems challenging in the near future.

With respect to theory, our findings tie to a larger recent literature that points to the relevance of deeply rooted values and beliefs leading to well‐structured foreign policy preferences (Kertzer et al., Reference Kertzer, Powers, Rathbun and Iyer2014; Kertzer & Zeitzoff, Reference Kertzer and Zeitzoff2017). While in our case these seem to be primarily centred around the foreign countries' normative context, substantial subsets of the population also attribute weight to a rather strategic and/or economic calculus (Bechtel et al., Reference Bechtel, Genovese and Scheve2019). Even more, we also trace a segment of the population exhibiting deontological preferences (surprisingly large with around 10–15 per cent of respondents, with substantial variation between countries), which seemingly clusters in specific parties (rather on the political left) and is seemingly more attentive to voting along its principles. This mode of decision‐making has largely been overlooked in the literature but is theoretically intriguing: it leads to a wedge between what theory lets us expect for governments' arms trade decision‐making (a consequentialist calculus focused on economic and security implications (García‐Alonso & Levine, Reference García‐Alonso and Levine2007) and citizen preferences (consequentialists putting strongest weight on the foreign countries' normative context; citizens in fundamental opposition rejecting any exporting‐strategy throughout). Given its likely foundation particularly in pacifist motivations in our case, this wedge might be relevant beyond arms exports, for all policies involving questions of war and peace.

We see several important avenues for future research: first of all, future research could extend to other country contexts, particularly the United States and the United Kingdom as important democratic exporters. Second, future research should compare whether the strong normative foundation of arms trade policies is indeed peculiar to the domain of exports in military goods, or whether respondents would despise any trade (so also in non‐military, and particularly elite consumption goods) with dictatorships and human rights violators to a similar extent. Third, future research could explore motivations for deontologist preferences.Footnote 18 Last but not least, our research focuses on the fundamental preferences of the public vis‐à‐vis the export of weapons. But our supplementary analysis indicates that principled opposition to arms exports directly relates to the issue being important for voting. In future research, it would be worthwhile to investigate to what extent the issue affects actual political behaviour, for example, voting decisions, and to what extent these preferences can be politicized, for example, when parties are campaigning for or against far‐ranging policy decisions such as European integration in the defence and security domain. In other foreign policy areas, the literature has already established that the public is both a vigilant observer of foreign policy (e.g., Kertzer & Zeitzoff, Reference Kertzer and Zeitzoff2017) and that its preferences matter for foreign policy‐making (e.g., Goldsmith & Horiuchi, Reference Goldsmith and Horiuchi2012) – for example, for trade policy (e.g., Dür & Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2014) or military force (e.g., Tomz et al., Reference Tomz, Weeks and Yarhi‐Milo2020).

Acknowledgements

Thomas Bernauer, Nicole Bolleyer, Tim Büthe, Andreas Dür, Vally Koubi, Giorgio Malet, Laura Seelkopf, Susumu Shikano, Keith Smith, Jan Vogler, David Weyrauch, colleagues in research seminars at LMU Munich, ETH Zurich and the University of Konstanz, and participants of the 2021 Annual Conference of the European Political Science Association and the 2022 Meeting of the International Political Economy Sections of the German, Austrian and Swiss Political Science Associations provided valuable feedback. We acknowledge financial support by Grant No. FP 02/20 ‐ PS 03/11‐2019 of the Deutsche Stiftung Friedensforschung. The study was pre‐registered, and the pre‐analysis plan is available at https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/FZK52, the survey instrument at https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/RJ89E. The survey was approved by the Ethics Commission of the Social Science Faculty of LMU Munich (GZ 20‐01). Data and replication code are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/C6PTYD and in supplement S2.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure A.1: Polls on arms exports in Germany and France around the Russian invasion of Ukraine in early 2022.

Figure A.2: Survey screen with exemplary display of conjoint experiment (German version).

Table A.1: Realised quotas and target quotas (source: Destatis/INSEE).

Table A.2: Realised regional quotas and target quotas (source: Destatis/INSEE).

Table A.3: Additional respondent characteristics.

Table A.4: Examples of statements from open text box on motivations for rejection of a high‐value arms transfer to a human rights abiding democratic country context.

Figure A.3: Responses to general attitudes towards war for rejectors in conjoint.

Table A.5: Predicted average support for specific arms transfers (rating outcome).

Figure A.4: Marginal means for all attributes.

Figure A.5: AMCEs for the rating outcome.

Figure A.6: ACPs (Ganter Reference Ganter2023) for the forced‐choice outcome and for all attributes.

Figure A.7: CAMCEs and differences in CAMCEs by deontologist vs. consequentialist respondents.

Figure A.8: Interaction of economic value with norm related attributes.

Figure A.9: Interaction of weapon type with norm and economic related attributes.

Figure A.10: MMs by country and country difference for all attributes (rating outcome).

Figure A.11: AMCEs by country and country difference for all attributes (choice outcome).

Figure A.12: Distribution of ratings over different arms trade profiles by country.

Table A.6: Issue importance of arms trade for election decision.

Table A.7: Germany: rejectors and party support.

Table A.8: France: rejectors and party support.

Data S1