1. Introduction

The term bilingualism denotes the ability to communicate in more than one language, and following this definition, more than half of the world’s population is bilingual (e.g., Grosjean, Reference Grosjean2010). Yet, bilingualism refers to a complex and graded experience based on factors like age of acquisition of a second language, frequency of use, frequency of code switching, etc. (see, e.g., de Bruin, Reference de Bruin2019; Kałamała et al., Reference Kałamała, Chuderski, Szewczyk, Senderecka and Wodniecka2023; Marian & Hayakawa, Reference Marian and Hayakawa2021). Depending on these factors, bilinguals are rarely completely “balanced,” implying that their first language (L1) is typically dominant relative to a second language (L2; see Treffers-Daller, Reference Treffers-Daller2019). Yet, there is evidence suggesting that in bilinguals, the known languages are typically simultaneously available, so that words are usually activated to some degree also in the nontarget language even in single-language contexts (e.g., Costa et al., Reference Costa, Caramazza and Sebastian-Galles2000; Meade et al., Reference Meade, Midgley, Sehyr, Holcomb and Emmorey2017). This poses particular problems because speaking in L2 thus requires language control processes to overcome competition from the dominant L1 and thus to change the situational language balance in favor of L2 (Green, Reference Green1998). These flexible language control processes in bilingual situations have mainly been examined using the language switching paradigm (see Declerck & Koch, Reference Declerck and Koch2023 for a review).

In the language-switching paradigm, participants are usually asked to name language-unspecific stimuli, such as digits or pictures. In cued language switching, for instance, an explicit language cue, such as a national flag, precedes or is presented simultaneously with the to-be-named stimulus, indicating the current target language. Such studies revealed two general findings. First, reaction times (RTs) and error rates are typically higher in language switch trials, which require a different language as the previous trial, than in language-repetition trials, thus showing switch costs (e.g., Costa & Santesteban, Reference Costa and Santesteban2004; Heikoop et al., Reference Heikoop, Declerck, Los and Koch2016; Meuter & Allport, Reference Meuter and Allport1999; Peeters & Dijkstra, Reference Peeters and Dijkstra2018; Timmer et al., Reference Timmer, Christoffels and Costa2019). Second, even though L1 responses are typically faster than L2 responses in single-language conditions, in mixed language conditions, L1 responses are often generally slower than L2 responses (“L1 slowing,” e.g., Christoffels et al., Reference Christoffels, Firk and Schiller2007; see also Goldrick & Gollan, Reference Goldrick and Gollan2023).

Switch costs are often attributed to the control requirements needed to downregulate activation of the currently not intended language (see, e.g., Declerck & Philipp, Reference Declerck and Philipp2015; Green, Reference Green1998; Green & Abutalebi, Reference Green and Abutalebi2013; Kleinman & Gollan, Reference Kleinman and Gollan2018; Koch et al., Reference Koch, Declerck, Petersen, Rister, Scharke and Philipp2024; Kroll et al., Reference Kroll, Bobb, Misra and Guo2008; Meuter & Allport, Reference Meuter and Allport1999; Philipp et al., Reference Philipp, Gade and Koch2007). A major theoretical account assumes “reactive” inhibition of the nontarget language (Green, Reference Green1998). This account has also been used to explain that switch costs can be larger for the dominant L1 than for the nondominant L2 (Meuter & Allport, Reference Meuter and Allport1999), but there are alternative, noninhibitory accounts (see also Blanco-Elorrieta & Caramazza, Reference Blanco-Elorrieta and Caramazza2021; Finkbeiner et al., Reference Finkbeiner, Almeida, Janssen and Caramazza2006; Koch et al., Reference Koch, Gade, Schuch and Philipp2010; Philipp et al., Reference Philipp, Gade and Koch2007), and this asymmetry of switch costs does not seem to be reliable (see Bobb & Wodniecka, Reference Bobb and Wodniecka2013 for a review; see Gade et al., Reference Gade, Declerck, Philipp, Rey-Mermet and Koch2021 for a meta-analysis).

In this study, we specifically focus on the second major finding in language switching, which is the general L1 slowing effect in mixed language conditions, sometimes also called “reversed language dominance effect” (see Declerck & Koch, Reference Declerck and Koch2023 for a review). These more sustained, general “L1 slowing” effects can be considered representing “proactive” control (see, e.g., Declerck, Reference Declerck2020). Generally, L1 slowing can be explained by an inhibitory control input specifically applied to L1 to facilitate access to L2 representations (i.e., lexical access, lemma activation) in a more proactive, sustained manner across language switch trials and repeat trials in mixed language conditions. Thus, examining L1 slowing represents a promising approach to understand better how bilinguals proactively control their language balance and how they make sure that the usually dominant L1 does not prevail when the target language is actually L2.

However, proactive control can have aftereffects extending into situations where it seems no longer needed. Such aftereffects have been shown in several contexts, differing in terms of their time scale (see Wodniecka et al., Reference Wodniecka, Casado, Kałamała, Marecka, Timmer, Wolna, Federmeier and Huang2020 for a review).Footnote 1 For example, several studies examined aftereffects of L2 on subsequent L1 performance in picture-naming paradigms in single-language contexts, in which the target language remained constant across blocks of trials. For example, Misra et al. (Reference Misra, Guo, Bobb and Kroll2012) asked Chinese-English bilinguals to name pictures, and half of the participants started in their L1 in an entire block of trials, followed by a block of L2 naming, whereas the other participants started with L2 followed by L1. Naming in L2 after L1 showed a general repetition benefit; yet, naming in L1 after L2 did not show a benefit, suggesting that facilitation due to stimulus repetition was offset by a more sustained downregulation of L1 based on the preceding L2 exposure (see also Casado et al., Reference Casado, Szewczyk, Wolna and Wodniecka2022; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Liu, Misra and Kroll2011; van Assche et al., Reference van Assche, Duyck and Gollan2013; Wolna et al., Reference Wolna, Szewczyk, Diaz, Domagalik, Szwed and Wodniecka2024 for similar designs). Similarly, Branzi et al. (Reference Branzi, Martin, Abutalebi and Costa2014) had their participants name picture in three blocks with languages alternating, starting either with L1 followed by L2 and then L1 again or with L2 followed by L1 and L2 again. They found that performance in L1 was worse after L2 exposure in-between, whereas there was no such aftereffect from L1 on subsequent L2 (see also Degani et al., Reference Degani, Kreiner, Ataria and Khateeb2020, Reference Degani, Kreiner and Declerck2024; Ivanova et al., Reference Ivanova, Seanez, Cochran and Kleinman2023).

Hence, while L1 slowing in mixed language blocks demonstrated immediate effects of L2 on L1 in mixed language blocks themselves (i.e., trial-by-trial level), such effects can also be demonstrated on a somewhat longer time scale based on the aftereffect of L2 performance on subsequent L1 performance in single-language conditions. In this study, we aimed at examining the persistence of L1 slowing after preceding mixed language blocks.

This study was inspired by a study of Christoffels et al. (Reference Christoffels, Ganushchak, La Heij and Schwieter2016) reported in a book chapter. In their study, in a pretest, Dutch-English bilinguals named pictures in single-language blocks in their L1 and their L2, with order counterbalanced across participants (i.e., L1 first vs. L1 second), and then performed in mixed language blocks. In the mixed blocks, the target language was indicated by a color cue, which was presented simultaneously with a target picture. Finally, the participants named pictures again in single-language blocks in a posttest. The pretest showed better performance for L1 than for L2; yet, in the posttest, this L1–L2 difference was reversed. This finding represents a different version of L1 slowing (i.e., aftereffect of mixed language blocks on performance in subsequent single-language blocks) and is consistent with a sustained inhibitory bias against L1 that persists even into subsequent language-pure conditions.

However, given the previously reported effects of L1 versus L2 block order (e.g., Branzi et al., Reference Branzi, Martin, Abutalebi and Costa2014; Misra et al., Reference Misra, Guo, Bobb and Kroll2012), it is notable that Christoffels et al. (Reference Christoffels, Ganushchak, La Heij and Schwieter2016) did not focus on the order of the single-language blocks in their study. They report only in a footnote that in their first experiment eight participants started with L1 and ten with L2, but that including block order in the analysis did not show effects of block order. However, this between-subject comparison of block order effects, which was not the focus of Christoffels et al. (Reference Christoffels, Ganushchak, La Heij and Schwieter2016), is limited by small sample sizes and correspondingly limited statistical power.

Importantly, our study goes beyond that of Christoffels et al. (Reference Christoffels, Ganushchak, La Heij and Schwieter2016) by examining order effects of L1 versus L2 in the single-language blocks (L1 first vs. L1 second), using a larger sample (n = 50) of German-English unbalanced bilinguals. Specifically, “premixing single-language (i.e., ‘pure’) blocks” preceded mixed language blocks, which were followed by “postmixing pure blocks.” Generally, we expected the typical switch costs and L1 slowing in the mixed blocks, but our focus was on the pre–post comparison of the pure blocks. We expected a sustained L1 slowing in terms of faster L2 naming than L1 naming in pure blocks even after the mixed blocks. Critically, we also compared pure-block performance immediately after the mixed blocks, which is L1 in the L1 first group and L2 in the L1 second group. Hence, we explored whether the L1 slowing is present in the first postmixing pure block after the mixed language block and whether it would persist even into the second postmixing pure block.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

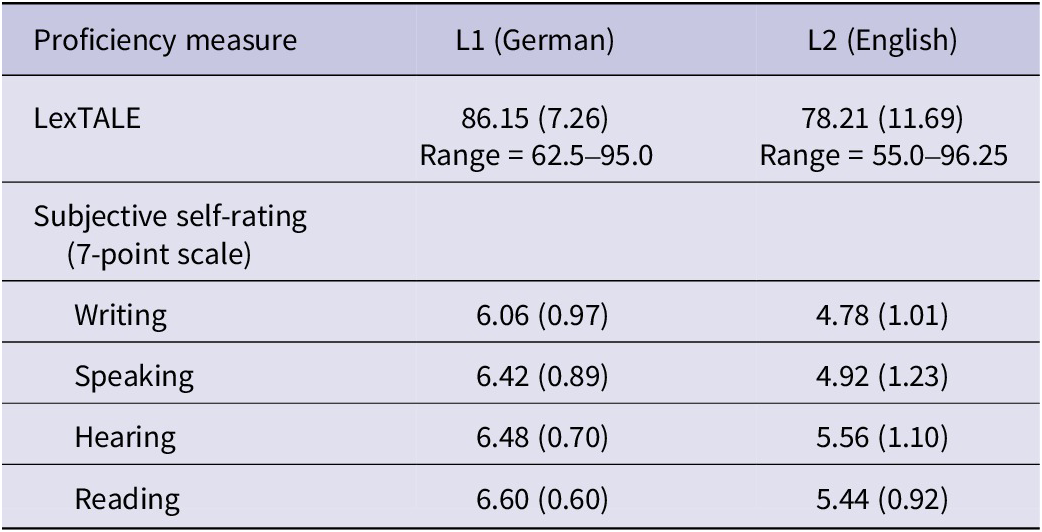

Fifty-four participants aged between 18 and 64 years were tested (M age = 22.72, SD = 7.46, 32 women and 22 men), but data from four participants could not be included in the analyses due to excessive microphone errors (one participant with 13.6% of such trials and three participants with over 50% of all trials), so the final sample size consisted of n = 50 participants (M age = 22.02, SD = 6.54, 18–54 years, 30 women and 20 men). They were mostly psychology students of RWTH Aachen University and participated for partial course credit. They were German native speakers. English is taught in school for all pupils in Germany, and English text reading is often required in psychology university classes. We assessed their proficiency level with subjective self-ratings on a 7-point scale for L2 English with respect to hearing and reading comprehension and speaking and writing ability. As an objective proficiency measure for lexical knowledge, we used a paper and pencil version of the LexTALE for L1 German and L2 English (Lemhöfer & Broersma, Reference Lemhöfer and Broersma2012). Together, the descriptive data show that the sample consists of unbalanced German-English bilinguals with overall good L2 proficiency (see Table 1).

Table 1. Description of language proficiency across L1 German and L2 English (mean [SD])

Note: LexTALE data are only from 49 participants for both L1 and L2 because one participant did not complete the task, but self-report data are from all 50 participants.

2.2. Stimuli and procedure

The stimuli were 20 pictures taken from the MultiPic database (Duñabeitia et al., Reference Duñabeitia, Crepaldi, Meyer, New, Pliatsikas, Smolka and Brysbaert2018). The stimuli were selected so that their names are noncognates in German and English, with an orthographic Levenshtein Distance of at least 4, that they have similar frequency (LogFreq(Zipf) > 4) and have one or two syllables (4–12 letters; see Appendix Table A1 for a complete list). Pictures were presented individually in white on a black background (approximately 6 mm high) at the center of a 17-inch screen (Samsung SyncMaster 740B). The German and British national flags (approximately 25 mm × 38 mm) served as language cues. The cues were surrounded by a white margin to be clearly demarcated from the black background. In each trial, four identical flags were presented 8 cm to the left and right and 5.3 cm above and below the target picture, measured from center to center. The target picture was thus enclosed by the cues. Participants were seated in a sound-insulated cabin. The experimenter sat outside the cabin and could hear the participants via headphones. The onset of the vocal naming responses not only was recorded by a voice key (using RockHouse DM-223 microphone), but was also recorded and offline checked for accuracy.

The study was conducted in November and December 2022 in a laboratory setting. Participants first gave their informed consent and signed a data protection document, indicating that their data would be analyzed in a pseudonymized way. Then, they first filled in the subjective proficiency rating scales for German and English followed by the LexTALE tasks.

Then, the participants were instructed that their task would be to name, as fast and correctly as possible, individually presented pictures in German or English as indicated by the national flags. Following these general instructions, the participants were shown all pictures, and the correct names in German and English were explained to achieve naming agreement.

The actual experiment was programmed in PsychoPy3 (Peirce et al., Reference Peirce, Gray, Simpson, MacAskill, Höchenberger, Sogo, Kastman and Lindeløv2019). In an individual trial, the language cue was first presented for 300 ms (i.e., cue–stimulus interval) followed by the target picture, which both remained on the screen until the participants responded by vocally naming it or until maximally 4000 ms elapsed. There was no error feedback. The subsequent response–cue interval was 1000 ms. The actual experiment began with 20 unrecorded practice trials in the same language as the subsequent first single-language pure block, followed by an L1 and L2 pure block of 40 trials each. Half of the participants started with L1 and the other with L2 (L1 First Group vs. L1 Second Group). Note that participants who started with L1 in the premixing pure blocks had L2 in the second block, whereas those participants who started with L2 had L1 in the second block. These “premixing” pure language blocks were followed by four mixed language blocks with 80 trials each. For these mixed language blocks, trial sequence was randomized with the constraints that both languages, language transitions (i.e., switch vs. repeat trial) and their combination occurred equally often. Moreover, in each block, each picture occurred twice for each language, once in a switch trial and once in a repeat trial. Finally, in “postmixing” pure blocks (i.e., after the mixed language blocks), there were again two pure blocks with 40 trials each, which were presented in the same order as at premixing. Participants had the opportunity for a short break between blocks.

2.3. Design

The main analysis focused on the pure blocks at pretest and at posttest as a function of language order of L1 and L2 testing. The independent variables thus were language (L1 vs. L2), time of testing (pretest vs. posttest) and testing order (first pure blocks vs. second pure blocks). Note that participants who started with L1 in the pure blocks had L2 in the second pure blocks, whereas those participants who started with L2 had L1 in the second pure blocks, so that this represents a between-subject comparison. The main dependent variable was RT. We did not analyze error rates because of the low number of errors (<5%), so that we only present the descriptive data on error percentages.

To estimate statistical power, we based our estimation on a recommendation by Brysbaert and Stevens (Reference Brysbaert and Stevens2018) for mixed effects modeling. They suggested that an experiment should have at least 1600 observations, calculated as the multiplication of the number of participants with the number of observations in each experimental cell for each participant, in order to be sufficiently powered for detecting small-to-medium effects of d ≈ .4. If we take the 40 trials in the pure blocks as number of observations, with our 50 participants this would result in 2000 observations for within-subject effects. However, given that our design includes a between-subject comparison, we assume that our design is at least sufficiently powered to detect larger effect sizes of d ≈ .8.Footnote 2

2.4. Transparency and openness

All procedures contributing to this work complied with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and its newer versions. We report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions, all manipulations and all measures in the study. Data were analyzed using R (R Core Team, 2024). This study’s design and its analysis were not pre-registered. The data are available at https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.15525.

3. Results

For RT analyses, the error trials and trials following errors were excluded. Furthermore, trials with RTs 2.5 SD above and below the grand mean were discarded as RT outliers. Taking these criteria into account, a total of 12.2% of the RT data was excluded from the mixed language block analysis and 10.3% of the RT data from the pure-block analyses. The RTs were analyzed using linear mixed effects regression modeling (Baayen et al., Reference Baayen, Davidson and Bates2008). Both participants and items were considered random factors with all fixed effects and their interactions varying by all random factors (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Levy, Scheepers and Tily2013). We used the following strategy in case of an issue with the fully randomized model (cf. Barr et al., Reference Barr, Levy, Scheepers and Tily2013; Matuschek et al., Reference Matuschek, Kliegl, Vasishth, Baayen and Bates2017): We first excluded random effects for the item-specific random slopes, starting with the higher order interactions. If the issue was not resolved, we moved on to the higher order interactions of the participant-specific random slopes. If this did not resolve the issue, we removed lower order terms, again starting with the item-specific random slopes before moving on to the participant-specific random slopes.

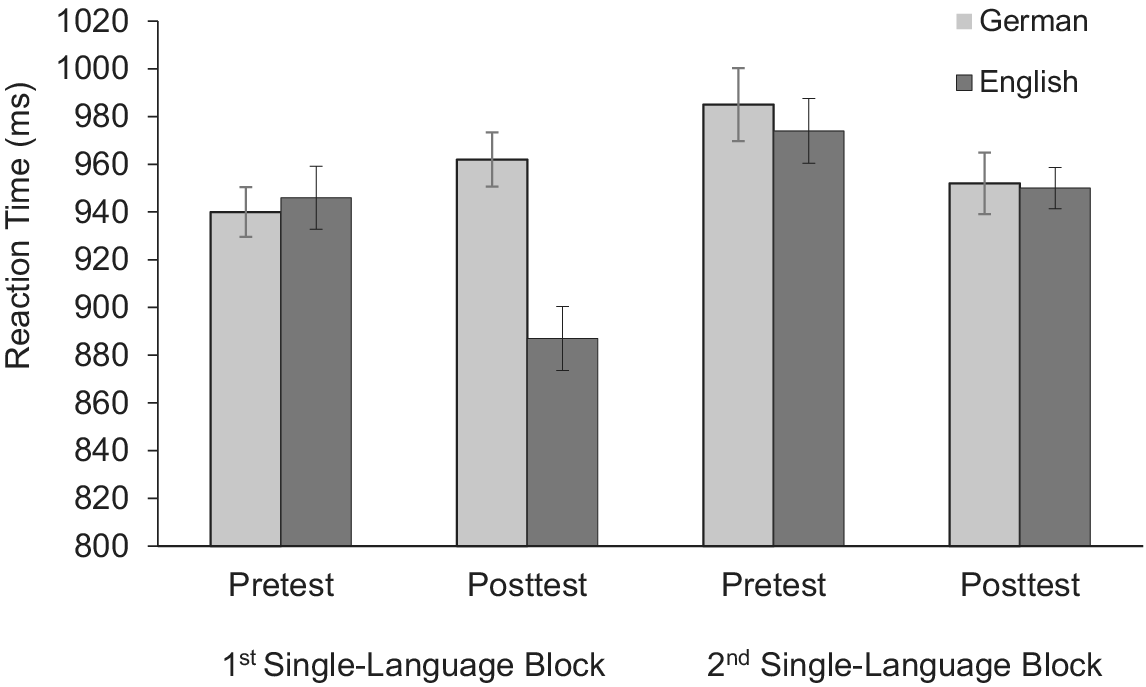

We focused on testing order of the pure blocks, examining the effect of pure blocks separately at pretest and at posttest as a function of testing order (see Figure 1). The independent variables thus were language (L1 vs. L2), time of testing (pretest vs. posttest) and testing order (first pure blocks vs. second pure blocks).

Figure 1. RT data of single-language (pure) blocks based on language (L1 German vs. L2 English), time of test (pretest vs. posttest) and testing order (first single-language block vs. second single-language block). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals (Cousineau, Reference Cousineau2005).

Importantly, the results showed a three-way interaction between the three variables (b = 82.14, SE = 32.67, t = 2.515, p < .05), qualifying all main effects and two-way interactions. Therefore, here we focus on the three-way interaction and decompose it as a function of testing order (i.e., first pure blocks vs. second pure blocks), which represents the critical information about the persistence of the aftereffect of mixed language exposure specifically on L1.

Specifically, in the first single-language blocks of the premixing and postmixing blocks, we found no main effect of Language (b = 33.24, SE = 26.20, t = 1.269, p = .209) and Time of Test (b = 19.55, SE = 11.09, t = 1.763, p = .084), but a significant interaction between Language and Time of Test (b = 77.58, SE = 25.76, t = 3.012, p < .01), with no significant RT difference between L1 and L2 in the first premixing block (940 ms vs. 946 ms for L1 vs. L2; b = 6.43, SE = 31.90, t = 0.202, p = .841) but significantly faster L2 (887 ms) than L1 (962 ms) in the postmixing block, after the mixed language blocks (b = 72.29, SE = 27.12, t = 2.666, p < .05).

In contrast, in the second blocks of the premixing and postmixing single-language blocks, we found a significant main effect of Time of Test (b = 33.06, SE = 10.92, t = 3.027, p < .01), with slower responses in the premixing (980 ms) than the postmixing (951 ms) blocks. Yet, there was no significant main effect of Language (b = 6.17, SE = 27.85, t = 0.221, p = .826) and we no longer found a significant interaction between Language and Time of Test (b = 5.04, SE = 23.08, t = 0.218, p = .828). Hence, the L1 slowing effect diminished in the second postmixing block.Footnote 3

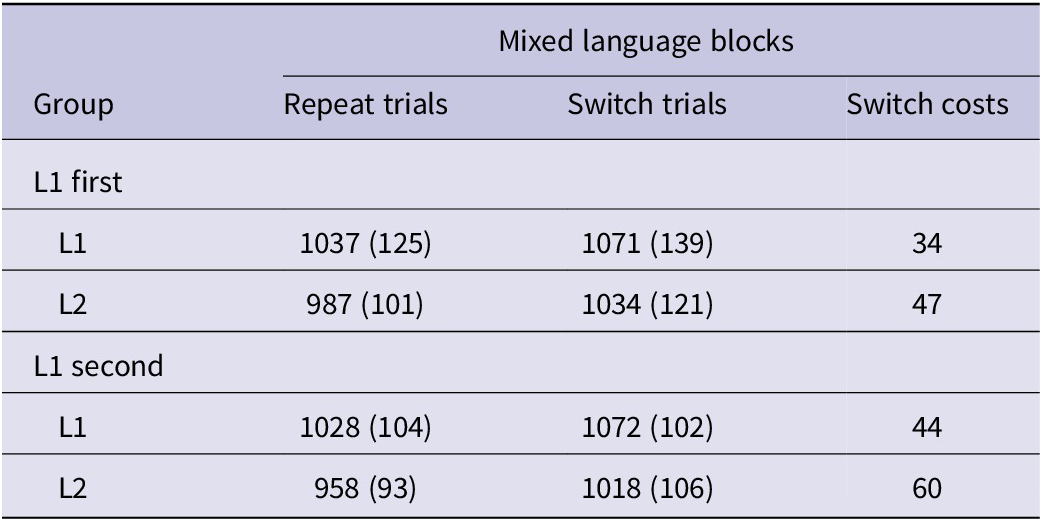

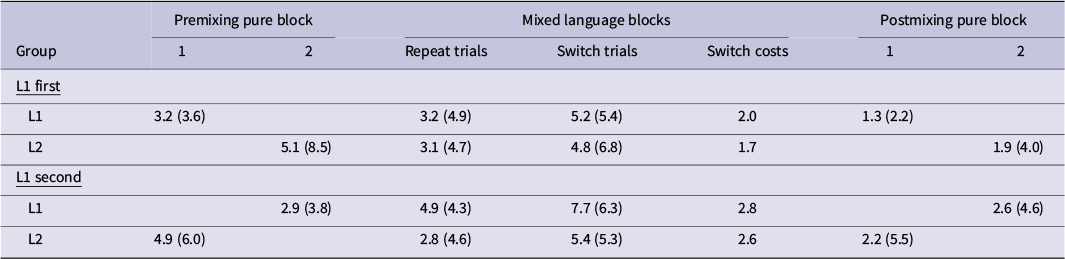

For the sake of completeness, we also analyzed the mixed language blocks as a function of Language (L1 vs. L2), Trial Type (switch vs. repetition) and Order (i.e., group starting with L1 vs. with L2). Note that both groups showed very similar performance in the mixed blocks (see Table 2). There was a significant main effect of Language, b = 51.11, SE = 10.45, t = 4.890, p < .001, with longer RTs for L1 than for L2 (1052 ms vs. 999 ms). This indicates a general L1 slowing effect in the mixed language blocks. There was also a significant main effect of Trial Type, b = 47.01, SE = 5.62, t = 8.362, p < .001, with longer RTs for switches than for repetitions (1048 ms vs. 1002 ms). The interaction was also significant, b = 14.42, SE = 6.48, t = 2.226, p < .05, suggesting slightly smaller switch costs for L1 (39 ms) than L2 (54 ms). While the opposite pattern has been observed across several studies, this specific pattern has also been noted more recently (e.g., Bonfieni et al., Reference Bonfieni, Branigan, Pickering and Sorace2019; Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Roelofs, Erkan and Lemhöfer2020; for meta-analyses, see Gade et al., Reference Gade, Declerck, Philipp, Rey-Mermet and Koch2021; Goldrick & Gollan, Reference Goldrick and Gollan2023). Yet, both groups showed a similar pattern, and the main effect and interaction effects of Order were not significant, p > .117.

Table 2. Mean performance (RT in ms [SD]) of condition L1 first and condition L1 second in mixed language blocks

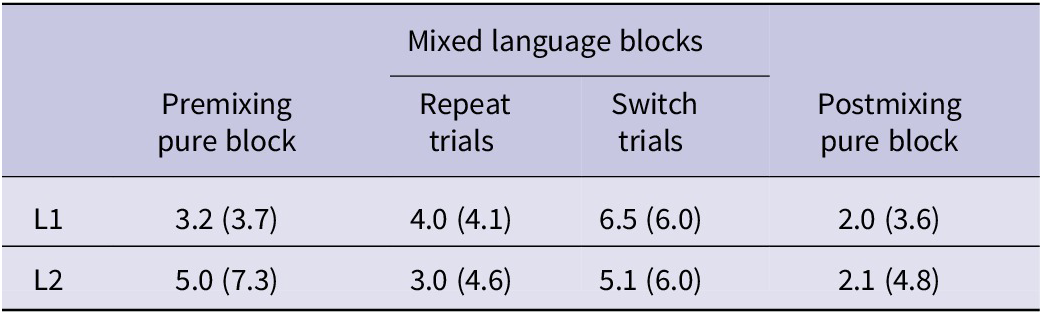

No detailed analyses were conducted on the error data because these were generally low (<5%) and showed a pattern that did not oppose the interpretation of the RT data. Here we only briefly summarize the basic pattern, averaged across the two language order groups (see Table 3), but for completeness we present the full pattern split by order group in Table A2 in the Appendix.

Table 3. Mean (SD in parentheses) error rates (in %) of condition L1 first and L1 second in pure and mixed language blocks averaged across order groups

In the premixing pure blocks the error data showed less errors in L1 than in L2, suggesting generally better performance in L1 than in L2. In postmixing pure blocks, the error rates are fairly similar for L1 and L2, but the reduction from premixing to postmixing was generally larger for L2 than for L1. In the mixed language blocks, error rates are higher in L1 than in L2, but switch costs were fairly similar for L1 and L2 (2.5% vs. 2.1%), so that these effects resemble the pattern of RT data very closely.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine L1 slowing as a measure of proactive language control in cued bilingual picture naming. Specifically, we examined L1 slowing and its persistence from mixed language blocks into subsequent single-language blocks. To this end, using a pretest–posttest design, we first established single-language baseline performance and then examined the aftereffect of subsequent mixed language exposure on final single-language conditions. Moreover, by exploring whether these aftereffects on L1 would appear only immediately after mixed blocks, in the first postmixing pure block, or extend into the second postmixing pure block, we also analyzed how enduring this persisting L1 slowing would be.

In the mixed language blocks, we found language switch costs (which were slightly asymmetric, being larger for L2 than for L1), and, more important for the present purpose, we also found general L1 slowing in both language switches and repetitions. Importantly, in the postmixing pure blocks, there was still L1 slowing, even though this aftereffect diminished in the second postmixing pure block. In the following we first discuss L1 slowing and then turn to its carryover to subsequent pure blocks.

4.1. L1 slowing as a measure of proactive language control

In the mixed language blocks, we found that L1 responses were generally slower than L2 responses, that is, in both switch and repeat trials (L1 slowing, see Christoffels et al., Reference Christoffels, Firk and Schiller2007). Finding this “reversed” language dominance is generally in line with the idea that L2 exposure triggers proactive language control to reduce the accessibility of L1 entries in the mental lexicon in a more sustained way to facilitate performing in L2. This relative downregulation of L1 may be particularly important in contexts that require frequent switches from L1 to L2 and back, such as it is required in mixed language blocks (see also Timmer et al., Reference Timmer, Christoffels and Costa2019). One difficult question refers to the exact mechanism underlying this L1 downregulation. In line with an inhibitory account, it is suggestive to assume that this downregulation is achieved in terms of inhibition of L1. However, given that a functionally similar effect would be achieved when simply increasing the overall activation of L2 (e.g., Blanco-Elorrieta & Caramazza, Reference Blanco-Elorrieta and Caramazza2021; Philipp et al., Reference Philipp, Gade and Koch2007; for discussion), the mere finding of L1 slowing is consistent with an inhibitory account but does not exclude noninhibitory accounts. Therefore, at this point it seems prudent to remain agnostic about the exact mechanism underlying L1 slowing, whether it is sustained L1 inhibition or sustained competition based on heightened L2 activation (see Declerck & Koch, Reference Declerck and Koch2023).

However, it is important to emphasize that L1 slowing in language-switching contexts (i.e., mixed blocks) does not simply represent a short-lived effect of reactive control to overcome language competition in a language switch trial, but that it rather extends to language-repetition trials. In this sense, L1 slowing represents an effect of proactive language control. Yet, repetition trials in mixed language blocks still occur within a time frame of seconds, so that L1 slowing in mixed language blocks might still represent a fairly short-lived effect. Kleinman and Gollan (Reference Kleinman and Gollan2018) found that effects of L1 slowing grow over the course of an experiment, but they used mixed language blocks for their analyses, so that the need for reactive control was probably still very recently required in preceding language-switch trials and therefore the degree of persistence of L1 slowing in the absence of the need for reactive control in language switches remained unknown. In this study, we examined the aftereffect of proactive language control in mixed language conditions by testing the carryover of L1 slowing into subsequent single-language block performance.

4.2. Persistence of proactive control: Carryover of L1 slowing

The present data show that L1 slowing still occurred after the mixed language blocks and thus shows a temporally more extended persistence of proactive language control. These findings critically extend an initial report by Christoffels et al. (Reference Christoffels, Ganushchak, La Heij and Schwieter2016) on the aftereffect of mixed language blocks on subsequent single-language blocks by showing that, in our study, this effect is largely confined to the first postmixing single-language block (40 trials) and diminishes in the second postmixing block.

We found persisting L1 slowing only in the first postmixing pure block, but no longer in the second block. Two issues require consideration. First, we used a relatively small set of 20 pictures that were repeated across the experiment. For example, Misra et al. (Reference Misra, Guo, Bobb and Kroll2012) argued that item repetition would benefit L2 more than L1. In their study, they found this repetition facilitation across repeated items for L2 but not for L1, suggesting that L2-based downregulation of L1 worked against a similar practice-related facilitation in L1. Similarly, in our study, focusing on the first pure blocks, we found that the pretest–posttest performance difference for L1 (in the L1 First group) was negative (i.e., a slight RT increase by 22 ms), while for L2 there was a substantial gain of 59 ms. Critically, while stronger repetition facilitation effects for L2 than for L1 might be expected, this effect alone could not explain why L2 was actually even 75 ms faster than L1 in the first postmixing pure block. This “relative” L1 slowing speaks in favor of a sustained L1 downregulation and cannot be explained simply by stronger repetition effects for L2 alone. This line of argument is also supported by findings of Degani et al. (Reference Degani, Kreiner, Ataria and Khateeb2020), showing that detrimental effects of L2 exposure on subsequent L1 performance occurred in the subsequent test phase both for old items and for new transfer items that were introduced only at the test phase (see also first evidence on that issue reported by van Assche et al., Reference van Assche, Duyck and Gollan2013). Together, the evidence suggests that L1 slowing based on preceding L2 performance is at least to some degree due to “whole-language control mechanisms” (Degani et al., Reference Degani, Kreiner, Ataria and Khateeb2020, p. 173). We would like to note though that L1 slowing and L2 facilitation may represent two sides of the same coin and are thus hard to distinguish, and it is likely that both processes contributed to our findings.

A second issue, intimately tied to the issue of blocked language order, is whether our premixing blocks represent a good “pure” baseline condition. The different (counterbalanced) orders of L1 and L2 seem to have generated already some language order aftereffects. Generally, RT increased slightly from the first to the second block, but this effect was independent of language (i.e., not specific to L1) and thus cannot explain our finding of a large reversed language dominance in the first postmixing single-language block, which we attribute to exposure to the preceding language-mixing context. Moreover, before starting with the actual picture naming experiment, our participants were shown the pictures together with their L1 and L2 names (to ensure naming agreement across participants), and they also performed the LexTALE task, which is a lexical decision task on visually presented words versus nonwords. Thus, some pre-experimental exposure to L2 took place before the actual experiment started, which might have affected language activation. Some researchers suggested to avoid any specific L2 “pretraining” (e.g., Misra et al., Reference Misra, Guo, Bobb and Kroll2012), yet our data seem to suggest that the influence of our naming agreement procedure, if any, did at least not wipe out any systematic aftereffects that we did observe in the course of our subsequent picture-naming experiment. In addition, it is less clear whether a different bilingual task, which was nonspeeded, used visual–verbal stimuli and nonvocal, manual responses, would produce significant transfer effects on a subsequent picture-naming task. Future research could examine whether such cross-task transfer represents a critical issue in cued bilingual picture naming.

As a more general point, given the prevalence of bilingual language inputs in times of smartphones and other Internet-based devices, it will be increasingly difficult to assess a pure, “uncontaminated” baseline for L1 (or for L2) performance, given that typical unbalanced bilinguals, at least in Germany and presumably in many other countries, are exposed to bilingual contexts on an everyday basis, which most likely affects how bilinguals regulate bilingual interference (e.g., Beatty-Martínez et al., Reference Beatty-Martínez, Navarro-Torres, Dussias, Bajo, Guzzardo Tamargo and Kroll2020). Moreover, it might be seen as a potential limitation of this study that we tested only unbalanced German-English bilinguals but no balanced bilinguals, for whom differential aftereffects for L1 and L2 might be less expected. On this background, it is informative to see that the aftereffects of mixed language exposure, in terms of L1 slowing, extended into a subsequent pure block, but it did not persist into the second postmixing pure block. This limit of persistence suggests that 40 trials of picture naming in a single language is sufficient to drive the L1–L2 language balance back into a state in which L1 is again no longer significantly downregulated to favor L2.

In summary, our findings suggest that proactive language control is an important mechanism to reduce the availability of the “dispositionally” dominant L1 to create a current language balance in favor of L2, so that, in the current situation, L2 can become situationally dominant and can, obviously, replace the otherwise dominant L1 as target language. This enables, or at least facilitates, flexible switching and use of more than one language in bilingual speakers. Yet, the reverse side of the coin is that this flexibility is bought at the price of a more enduring bias against L1 which apparently persists across some time (and a good number of trials) even when the proactive bias against L1 is no longer needed. It is interesting to see that this delicate balance of control and interference is similarly discussed in research on nonlinguistic task switching (e.g., Kiesel et al., Reference Kiesel, Wendt, Jost, Steinhauser, Falkenstein, Philipp and Koch2010; Koch et al., Reference Koch, Poljac, Müller and Kiesel2018; Koch & Kiesel, Reference Koch, Kiesel, Kiesel, Johannsen, Koch and Müller2022 for reviews) and suggests that persisting but dissipating aftereffects of control are pervasive across both nonlinguistic task control and bilingual language control.

5. Conclusions

This study showed that performance in mixed language contexts was generally worse for L1 than for L2. This “reversed” language dominance effect suggests the influence of proactive language control to downregulate access to L1 across both switch trials and repeat trials in mixed language blocks in order to facilitate L2 performance. Yet, the most important and novel contribution of this study is that reversed language dominance, as a measure of proactive language control, shows some persistence even into postmixing single-language blocks. Yet, this persistence of L1 downregulation was limited to a first block of 40 trials and did not extend into a second block, suggesting that the bias exerted by proactive control against L1 dissipates within minutes. Hence, language control endows bilingual speakers with remarkable linguistic flexibility, but at the same it seems as if proactive language control can overshoot and produce detrimental aftereffects in L1 performance. That is, language control shows both flexibility and inertia. Future studies will have to examine the time course of proactive language control in more detail in order to get an even better understanding of this delicate balance between flexible control and inflexible temporal inertia of control settings.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in PsychArchives at https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.15525.

Acknowledgements

Parts of these data have been presented at the ESCoP conference in September 2023 in Porto, Portugal. The authors thank Vuslat Karaaslan and Wolfgang Scharke for their help in the study. MD was supported by the Strategic Research Program of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Grant No. SRP88. LMS was supported by the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO), Grant No. FWOTM1127.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Appendix

Table A1. Selection of stimuli

Table A2. Mean (SD in parentheses) error rates (in %) of condition L1 first and L1 second in pure and mixed language blocks