“Every revolution has been preceded by an intense work of criticism, cultural penetration and diffusion of ideas.” (Gramsci, 1916)

Introduction

The consensus over liberal democracy has been fading over the last decade. As underscored by the editors of this issue, we are witnessing an era of dissensus, understood as the expression of conflicts between social, political, and legal actors in different arenas, with the aim of maintaining, restructuring or replacing liberal democracy (see Coman and Brack in this special issue). Political parties from different ideological backgrounds are winning elections with programs opposing liberalism and liberal democratic institutions. Persuasive analyses have revealed how some key tenets of conservatism and illiberalism (Canihac Reference Canihac2022; Laruelle Reference Laruelle2022) have moved from the fringe to the core of the political systems in Europe (Pytlas Reference Pytlas, Herman and Muldoon2019; Herman et al. Reference Herman, Hoerner and Lacey2021), standing against pluralism and multiculturalism and in favor of an ultra-nationalist, Christian, and conservative order. However, rampant illiberalism is not confined to the party systems. Parties challenging liberal democracy, including its norms, institutions, and policies, do not emerge in a vacuum (Buzogány and Varga Reference Buzogány, Varga, Bluhm and Varga2019, Reference Buzogány and Varga2023; Greskovits Reference Greskovits2020; Bill Reference Bill2022; Pirro and Stanley Reference Pirro and Stanley2022; Bohle et al Reference Bohle, Greskovits and Naczyk2023; Coman and Volintiru Reference Coman and Volintiru2023; Jezierska Reference Jezierska2023). Bluhm and Varga (Reference Bluhm, Varga, Bluhm and Varga2019: 7) highlight that “illiberalism might owe its rise not only to the dynamics of political systems, but also to developments in civil society.”

A complex process of change seems to be taking place, intertwining political, social, and cultural transformations. In Hungary and Poland, the Fidesz- and PiS-led governmentsFootnote 1 have engaged in a triple process of changing politics, policy, and polity (Coman and Volintiru Reference Coman and Volintiru2023), contributing to the construction of a new state (Pető Reference Pető2021) with its own organizations and elites (Bill Reference Bill2022; Behr Reference Behr2023). Illiberal governments have established new—and loyal—research institutions, universities, museums, and colleges imperfectly mimicking the traditional ones (Pető Reference Pető2021: 465) to act as central players in this process of deep cultural transformation. As Pető (Reference Pető2021: 461) has argued, illiberal politicians “recognized the importance of educational institutions as sites of knowledge production and transfer, training of loyal supporters, academic authorization, and dissemination of ideas.”

This article examines this process of change from below, focusing on how actors within civil society contribute to the production and dissemination of illiberal ideas (Coman et al. Reference Coman, Behr and Beyer2023), thereby fueling dissensus over liberal democracy. To shed light on this phenomenon, we explore the role of illiberal think tanks in Poland and Hungary, which over the past decade have become fertile ground for the production (Behr Reference Behr and Laruelle2024) and diffusion of ideas against liberal democracy (see Enyedi and Stanley in this issue). Traditionally, think tanks have been portrayed as “the brains” of political parties (Vande Walle and de Lange 2024: 1). Similarly, we argue that illiberal think tanks act as mediators and builders in the emergence of a transnational illiberal field, bringing together political elites, institutions, media and, crucially, a wide range of intellectuals with diverse backgrounds. The actors woven together by think tanks in this transnational field contribute to the production and dissemination of ideas fueling a struggle against liberal democracy.

Following an abductive method as an iterative process between theory and empirics, the article builds on Gramsci’s concept of cultural hegemony combined with Bourdieu’s concepts of field and cultural capital. We argue that illiberal actors engage in a process of cultural hegemony against liberal democracy, leading to the emergence and strengthening of an illiberal transnational field. They do so through the accumulation of cultural capital by organic intellectuals. In addition to the interplay between the Gramscian and Bourdieusian concepts, the article identifies four functions that illiberal think tanks perform in this process.

Empirically, the article focuses on think tanks based in Poland and Hungary, where the current Fidesz and the previous PiS governments have engaged in proactive policy support for the development of illiberal think tanks (Bluhm and Varga Reference Bluhm, Varga, Bluhm and Varga2019; Behr Reference Behr2023; Buzogány and Varga Reference Buzogány and Varga2023). The article traces the online communication (i.e., TwitterFootnote 2 accounts) of a number of think tanks who stand against democracy and its liberal components, rejecting political (e.g., authoritarian constitutionalism) and cultural liberalism (e.g., conservatism) while maintaining an ambiguous attitude toward economic liberalism.

The article is organized as follows: drawing on both Gramsci and Bourdieu, as well as the literature on think tanks, section “The emergence of a transnational illiberal field: the four functions that think tanks fulfill in building an illiberal cultural hegemony” theoretically discusses the emergence of a transnational illiberal field, focusing on the four roles that think tanks fulfill in their counter-hegemonic Footnote 3 stance: mediator, builder, disseminator, and legitimizer of a discourse against liberal democracy. Section “Illiberal think tanks in Poland and Hungary: research design and data collection” presents the research design, discusses the focus on Poland and Hungary as representative cases for the rise of illiberal think tanks, and presents the dataset. Section “Illiberal think tanks as mediators and builders of a transnational illiberal field” illustrates the density and the composition of the emerging transnational illiberal field in which think tanks act as mediators and builders. “Conclusions” focus more specifically on how think tanks act as disseminators and legitimizers of a new cultural hegemony against liberal democracy by drawing on the cultural capital of intellectuals, including academics, journalists, writers, and experts. To conclude, the article presents its contribution to the literature and puts forward new avenues for further research. In so doing, the article adds to the literature on think tanks, whose role is well-explored in liberal democratic countries (e.g., Stone Reference Stone1996; Abelson Reference Abelson2009; Medvetz Reference Medvetz2013) but is largely neglected both in authoritarian (Bacon Reference Bacon2018; Köllner et al. Reference Köllner, Zhu and Abb2018) and autocratizing contexts (Jezierska Reference Jezierska and Laruelle2024, Reference Jezierska2023).

The emergence of a transnational illiberal field: the four functions that think tanks fulfill in building an illiberal cultural hegemony

The critique of liberal democracy is not new—it comes from both the left and the right of the political spectrum (Garrard Reference Garrard, Sajo, Uitz and Holmes2022: 34). Depending on the angles of criticism, a variety of terms have been used to describe it, ranging from anti-liberal ideas (Coman and Volintiru Reference Coman and Volintiru2023) to populism and illiberalism (Sajo et al. Reference Sajo, Uitz, Holmes, Sajo, Uitz and Holmes2022). None of these concepts is hermetically sealed. Just as anti-liberalism (Holmes Reference Holmes, Sajo, Uitz and Holmes2022) and populism cover different realities, illiberalism is also in search of a definition (see Sajo et al. Reference Sajo, Uitz, Holmes, Sajo, Uitz and Holmes2022: xxi). For some, the term defines a regime (Zakaria Reference Zakaria1997); for others, it is instead an ideology (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2022) or a state of mind, or even a cultural style (Rosenblatt Reference Rosenblatt, Sajo, Uitz and Holmes2022: 23). What these approaches, which are often used interchangeably, have in common is an attempt to encapsulate an opposition to liberalism or liberal democracy. While liberalism is used to refer to rights and its intellectual history shows that it brings together a wide range of principles and values, illiberalism refers to the disdain of such rights (Rosenblatt Reference Rosenblatt, Sajo, Uitz and Holmes2022: 28). In the same vein, anti-liberalism is defined by Holmes as an intellectual tradition that blames liberalism for the moral and spiritual degeneration of modern society (Garrard Reference Garrard, Sajo, Uitz and Holmes2022: 35; Holmes Reference Holmes, Sajo, Uitz and Holmes2022). Despite controversy around illiberalism as an emerging concept, it is defined here as the “departure from what might, generally speaking, be a liberal polity,” consisting of a discourse combining non-liberal ideas and values (Freeden Reference Freeden and Gosewinkel2015: 34). Illiberalism covers a gray zone of actors that, even nominally professing themselves as liberal, are often at odds with the tenets of liberalism (Canihac Reference Canihac2022).

The critique of liberal democracy is no longer merely an academic debate rooted in the history of ideas. It is at the core of political battles in different parts of the world taking the form of a growing dissensus over liberal democracy (see Brack and Coman in this special issue). While political parties seek to translate their opposition to liberal democracy into concrete political programs, their search for ideas is supported by a vivid intellectual debate about the failures of liberal democracy, both in the US (Pappin Reference Pappin, Sajo, Uitz and Holmes2022) and in Europe (as examined by Behr Reference Behr2023, Reference Behr and Laruelle2024 and Buzogány and Varga Reference Buzogány and Varga2023). What these political and academic milieus have in common is their stance against liberalism or liberal democracy, which they denounce as hegemonic (Pappin Reference Pappin, Sajo, Uitz and Holmes2022: 44). Whether these political and academic milieus are connected will be examined in this article.

Actors standing against liberalism or liberal democracy have instrumentalized Gramsci’s concept of cultural hegemony. Since the late 1960s, Gramsci emerged as a key reference not only in the social sciences and among left-wing groups, but even in the political circles of the nouvelle droite (Bar-On Reference Bar-On2014). More recently, Gramsci's concepts have been appropriated and instrumentalized by political figures of the far rightFootnote 4 (see Bohle et al. Reference Bohle, Greskovits and Naczyk2023) who seek to combat liberalism or liberal democracy, portrayed as hegemonic.

In his years in prison, Gramsci developed a theory of hegemony understood as “a strategy of power through cultural work” (Urbinati Reference Urbinati1998: 370). Inspired by the Italian context of his time, Gramsci contended that the bourgeoisie exercised not only a political and economic domination over the proletariat and the peasants, but also a cultural one. For Gramsci (2014: 2010), a successful revolutionary movement must aim to build a new cultural hegemony. To start a new revolutionary phase, a revolutionary social group needs to achieve “an intellectual and moral” supremacy. Intellectuals have a crucial role in building a new hegemony by building consensus, mediating the participation of different actors, and legitimizing an emerging social group (Gramsci 2014: 476). The role of intellectuals is key precisely because their cultural “organizational and mediation functions” to legitimize—in eyes of the people—both a given political project and, crucially, its repressive apparatus (Gramsci 2014: 1519). In the Gramscian lexicon (2014: 477–478), organic intellectuals are those linked with a social group aiming to diffuse, mediate, and legitimize a political project. In this respect, we can trace a difference between organic and traditional intellectuals, specifically noting that the organic intellectuals’ conscious bond with a political project leads them to act as “builders, organizers, and permanent persuaders” (Gramsci 2014:1550–1551).

Think tanks play a key role in this process of emergence of a counter-hegemony against liberal democracy. Like their liberal counterparts, illiberal think tanks claim to be laboratories of ideas. Traditionally, think tanks fulfill a variety of functions. Among these, knowledge acquisition and dissemination emerge as principal. Think tanks can conduct their own research or collect, analyze, and translate existing research (Vande Walle and de Lange 2024: 5). Positioned at the intersection of the political, bureaucratic, economic, academic, and media fields (Medvetz Reference Medvetz2013: 3), they not only seek to influence public policy but also to infuse new ideas legitimized by expertise, public visibility, and academic participation and credibility. Think tanks in general engage in a variety of political and public policy activities (Stone Reference Stone1996), with their primary goal being to spread ideas and influence policymaking and the governmental agenda (Ibid.: 3), while portraying an image of “science, detachment and objective expertise” (ibid.: 9).

We argue that illiberal think tanks pretend to fulfill the same functions of liberal ones, as they:

-

1. Act as national mediators and organizers (in the sense of Gramsci) bringing together political actors, media, and intellectuals, but also a more ambiguous and diffuse group of trolls on social media.

-

2. Act as builders of a transnational illiberal field including a variety of both European and American actors from civil society organizations to journalists, academics, and experts. Following Bourdieu, a field is defined as a system of relations in which actors struggle over political authority and control through ideational power (Bourdieu and Wacquant Reference Bourdieu and Wacquant1992: 97).

-

3. Seek to emerge as producers and disseminators of illiberal ideas to fuel the counter-hegemony process against liberal democracy. They “drive the illiberal agenda,” constantly infusing ideas into the national debate (Jezierska Reference Jezierska and Laruelle2024: 14). While Behr (Reference Behr2023) has rightly demonstrated that Eastern European conservative and illiberal intellectuals have become “producers of ideas,” his work shows that the think tank milieu relies on American intellectuals (writers, academics, journalists, experts) who have been active in publishing books and essays about the failures of liberal democracy. Some of these books have been translated into national languages and have been discussed and used by national political actors to support their ideological claims.

-

4. Act as legitimizers of the illiberal project, drawing on the cultural and academic capital of the actors involved. Cultural capital is linked to contextual and cultural knowledge or savoir-faire and specific system structures in academia, as well as social, political, and economic capital, encompassing personal and professional relations or “social ties” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1995). Crucially, different forms of capital can be exchanged and, thus, think tanks’ investment in cultural capital can be translated into a greater form of political, social, and economic influence. As a form of cultural capital, academic capital is associated with the prestige connected with academic authority. Thus, illiberal think tanks (like their liberal counterparts) hire researchers with PhD degrees and use academic style labels to designate their staff and activities, for example, “call[ing] their departments ‘research units,’ their employees ‘researchers’ or ‘fellows,’ their publications ‘research reports’ and ‘analyses,’ and the meetings they organize ‘seminars’ or ‘conferences’” (Jezierska Reference Jezierska2021: 408). They seek to legitimize a process of change and alternatives to liberal democracy by crafting public philosophies or a set of ideas to identify problem definitions and policy solutions (Buzogány and Varga Reference Buzogány and Varga2023: 43).

Illiberal think tanks in Poland and Hungary: research design and data collection

Poland and Hungary represent ideal cases to explore the role of think tanks in fueling dissensus over liberal democracy. From the top, the PiS and Fidesz governments have supported the emergence of a “conservative civil society” (Bluhm and Varga Reference Bluhm, Varga, Bluhm and Varga2019; Greskovits Reference Greskovits2020; Bill Reference Bill2022; Pirro and Stanley Reference Pirro and Stanley2022; Buzogány and Varga Reference Buzogány and Varga2023; Enyedi and Stanley in this issue, Paternotte Reference Paternotte2024) and funded several “polypore institutions” (Pető Reference Pető2021). In both countries, the governments have tailored a beneficial legal and financial environment for a “supportive” civil society that can “reinforce” their political narratives (Bill Reference Bill2022: 120), produce or diffuse their ideas, implement their political agenda, and engage in cultural and scientific activities within society (Bill Reference Bill2022; Behr Reference Behr2023; Bohle et al. Reference Bohle, Greskovits and Naczyk2023; Buzogány and Varga Reference Buzogány and Varga2023). In Hungary, this strategy intensified after 2019 with the introduction of the so called “public interest asset management foundation performing public duty”, further strengthened by the 9th amendment to the Hungarian fundamental law and allowing the government to directly finance supportive think tanks and civil society organizations (Oktatói Hálózat 2021). In Poland, the emerging “alternative” civil society has its roots in the mobilization of active ultra-Catholic groups. After the return of PiS to power in 2015, the government actively marginalized liberal and human rights organizations, infusing resources for the development of illiberal ones through the introduction of the National Freedom Institute, an organization providing financial support to civil society organizations close to PiS. Not only have the Polish and the Hungarian governments contributed to the establishment of these new actors, but they have also proceeded to a process of “elite replacement” in academia and the media (Bill Reference Bill2022; Behr Reference Behr2023), while also taking over existing educational and research institutions (Pető Reference Pető2021: 462).

These new organizations are not independent from politics, neither in terms of funding nor in terms of political allegiance (Jezierska and Sörbom Reference Jezierska and Sörbom2021; Jezierska Reference Jezierska, Kravchenko, Kings and Jezierska2022). They are also diverse in both countries. For the purpose of this analysis, we selected organizations “claiming autonomy, conducting social research and attempting to (directly or indirectly) influence policymaking, regardless of whether they define themselves as think tanks” (Jezierska Reference Jezierska2021:818). Drawing also on previous literature (Buzogány and Varga Reference Buzogány, Varga, Bluhm and Varga2019, Reference Buzogány and Varga2023; Dąbrowska Reference Dąbrowska, Bluhm and Varga2019; Wierzcholska Reference Wierzcholska, Bluhm and Varga2019; Bill Reference Bill2022), we focus on five think tanks and two self-declared universities. The former include the Centre for Fundamental Rights (CFR), the Danube Institute (DI), and the Századvég Foundation (S) in Hungary and Ordo Iuris (OI) and the Sobieski Institute (SI) in Poland (see Appendix 1 for an in-depth description of each organization). The latter include the Mathias Corvinus Collegium (MCC) in Hungary and Collegium Intermarium (CI) in Poland, which emerged as being intertwined with the selected think tanks. The nature of these organizations is still evolving. For instance, the MCC has opened a branch in Brussels explicitly aiming to “influence European policy makers”.Footnote 5 Collegium Intermarium was created as an academic spin-off of Ordo Iuris. In this respect, Collegium represents what, in describing the new trends of contemporary think tanks Weaver (Reference Weaver1989: 564) defined as “universities without students.” Indeed, in 2023 only one student was enrolled by the Collegium (Notes from Poland 2023). What these organizations have in common is not only a set of specific goals and claims targeting the core ideas of liberal democracy in the name of national identity, sovereignty, and Christian social values (see Enyedi and Stanley in this issue), but also their ambition to infuse illiberal ideas into the public sphere, hence their focus on research, publication, education, and dissemination.

Design and data collection

We have developed an original methodology allowing us to scrutinize the Twitter interactions of the seven selected think tanks. In this respect, we combined tools of formal network analysis—already employed in the analysis of think tanks (e.g., the Networked Intellectual Approach introduced by Tchilingirian Reference Tchilingirian, Abelson and Rastrick2021)—with qualitative insights on the nodes of interactions among think tanks, intellectuals, and other elites. In line with the function of think tanks discussed above, we expect that in acting as mediators, think tanks interact with a sizable number of intellectuals. In performing the role of builders of the illiberal field, we would expect think tanks to have the ability to attract elites from different countries and with different professional backgrounds, including political elites. In this framework, in acting as disseminators we expect to see network nodes linking think tanks with key figures in the contemporary intellectual debate over the limits of liberal democracy and illiberalism, coupled with an effort to present this debate to their national public. Finally, when acting as legitimizers within the illiberal field we expect to see elites holding academic credentials, thus strengthening the field by infusing academic capital.

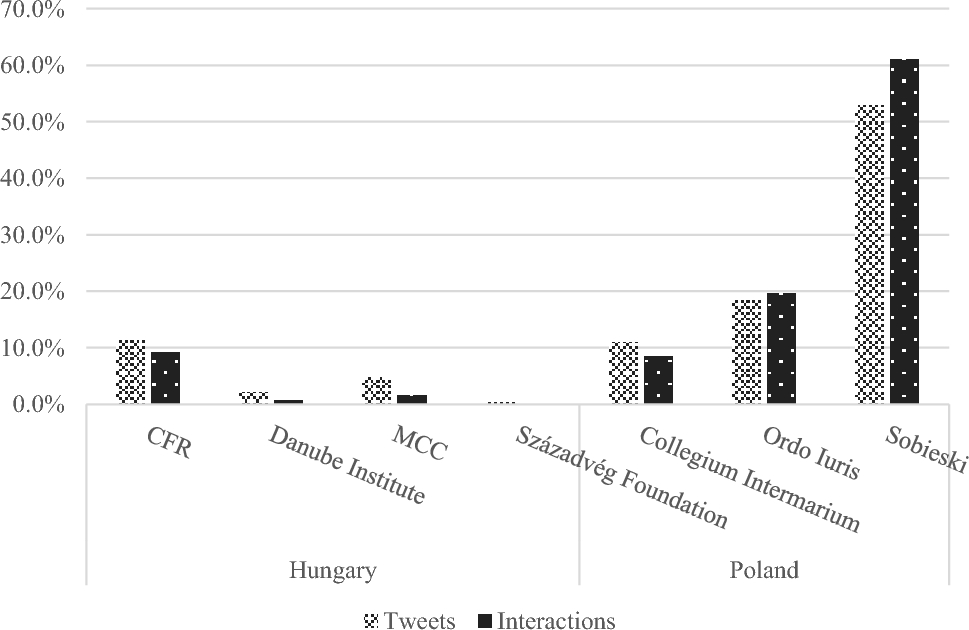

To build our dataset, we listed all the individuals mentioned as experts, analysts, lecturers, professors, and members of the boards across the selected organizations. Matching these names with their Twitter accounts resulted in a dataset of 76 seed accounts (see Appendix A2). We acknowledge that this design does not capture the entire set of members or sympathizers of these think tanks; however, it includes all individuals that they put forward to fulfill the functions discussed in Sect. "The emergence of a transnational illiberal field: the four functions that think tanks fulfill in building an illiberal cultural hegemony." We then scraped all the tweets from these accounts over a one-year period from the 1st of March 2021 to the 1st of March 2022, collecting a total of 91,594 tweets and retweets (Fig. 1). As Fig. 1 shows, the presence on Twitter of these organizations, in terms of interactions, varies, the most active being the Polish Sobieski Institute, Ordo Iuris, and Collegium, followed by the Hungarian MCC, CFR, and the Danube Institute.

Fig. 1 Number of think tanks tweets and interactions from March 1st 2021 to March 1st 2022. Note: Data are expressed as a percentage of the sample (N interactions = 155,251; N tweets = 91, 594 ).

We further added to our data by identifying all the accounts that had been retweeted, quoted, and mentioned by the seed accounts, resulting in 3499 accounts that share at least one connection in time with our original seed accounts. On this basis, we created a matrix indicating the number of interactions that our seed accounts had with each of these 3499 accounts. From here, we classified each of these interaction nodes using several categories to identify distinct accounts. We distinguished between: (i) institutions and government elites, (ii) political parties and political elites, (iii) media, (iv) intellectuals, and (v) anonymous accounts.Footnote 6 Furthermore, we distinguished between national and international accounts to illustrate the degree of internationalization of each network. The number of interactions between a think tank’s official account and its affiliates ranged from 94,509 interactions for the Sobieski Institute to just 86 for the Hungarian Századvég (Fig. 1).

Illiberal think tanks as mediators and builders of a transnational illiberal field

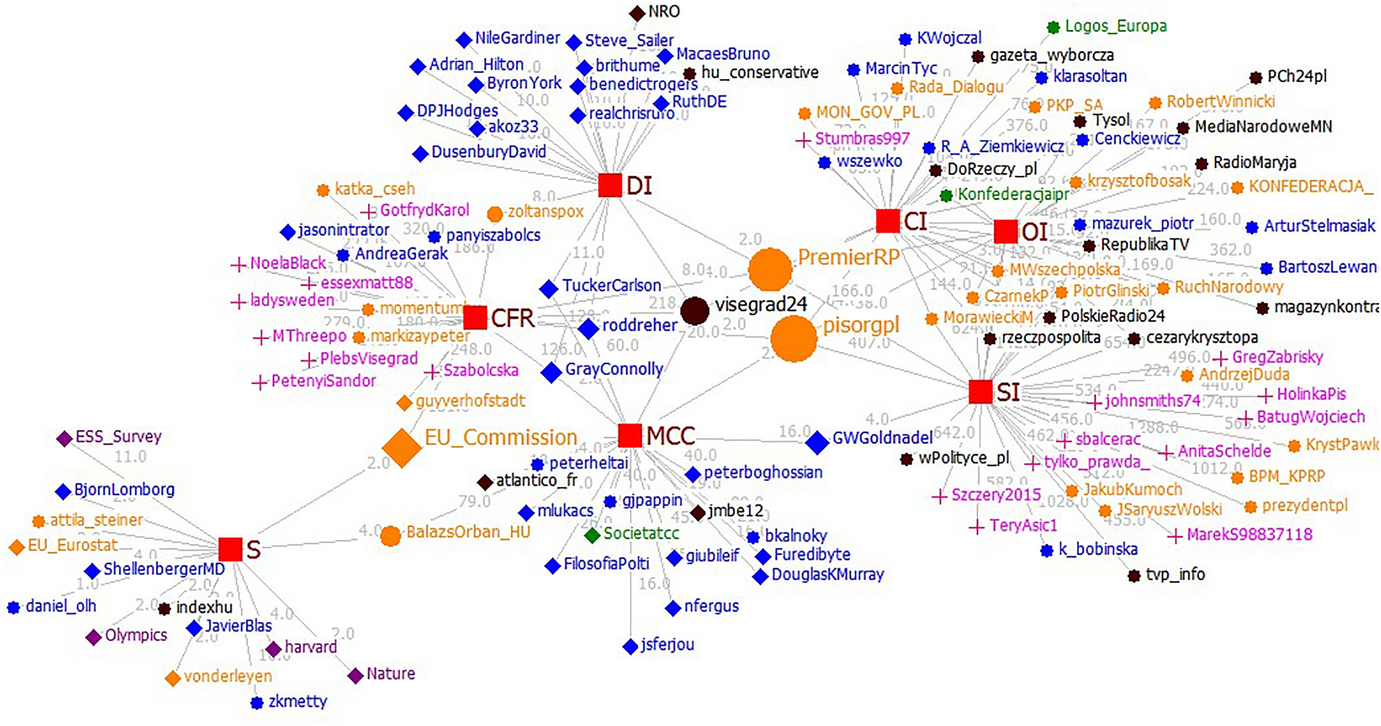

Think tanks act as national mediators bringing together political actors, media, and intellectuals, but also a more ambiguous and diffuse group of actors acting on social media, such as trolls. Our data show that the interactions with these actors vary. Figure 2, which focuses on the 20 accounts that have interacted the most with the analyzed think tanks, illustrates that intellectuals represent the largest category. Figure 2 also shows that foreign intellectuals emerge as predominant in the field of the Hungarian think tanks, in particular the MCC and the Danube Institute, while the Polish organizations’ interactions with intellectual profiles are more limited and mostly directed toward national intellectuals, as illustrated by Ordo Iuris and Collegium Intermarium. All the think tanks interacted with politicians, the media, institutions, and other think tanks. Additionally, the CFR and the Sobieski Institute featured several anonymous and troll accounts among their top interactions.

Fig. 2 Online interactions among the top 20 accounts mentioned by each think tank. Note: Red squares show seeding accounts. As far as target accounts are concerned, circles denote national accounts, diamonds indicate foreign accounts, and crosses indicate accounts that cannot be identified (i.e., anonymous). Blue is assigned to intellectuals; green is reserved for think tanks and associated experts; black indicates media accounts; orange designates political institutions, parties, and elites; pink indicates anonymous accounts and trolls; and lastly, purple designates accounts in the miscellaneous and residual category. The numbers displayed on the ties describe their strength, i.e., how many times the seeding account mentioned the target account over the studied period. Seed accounts and accounts no longer available on Twitter have been removed from the visualization.

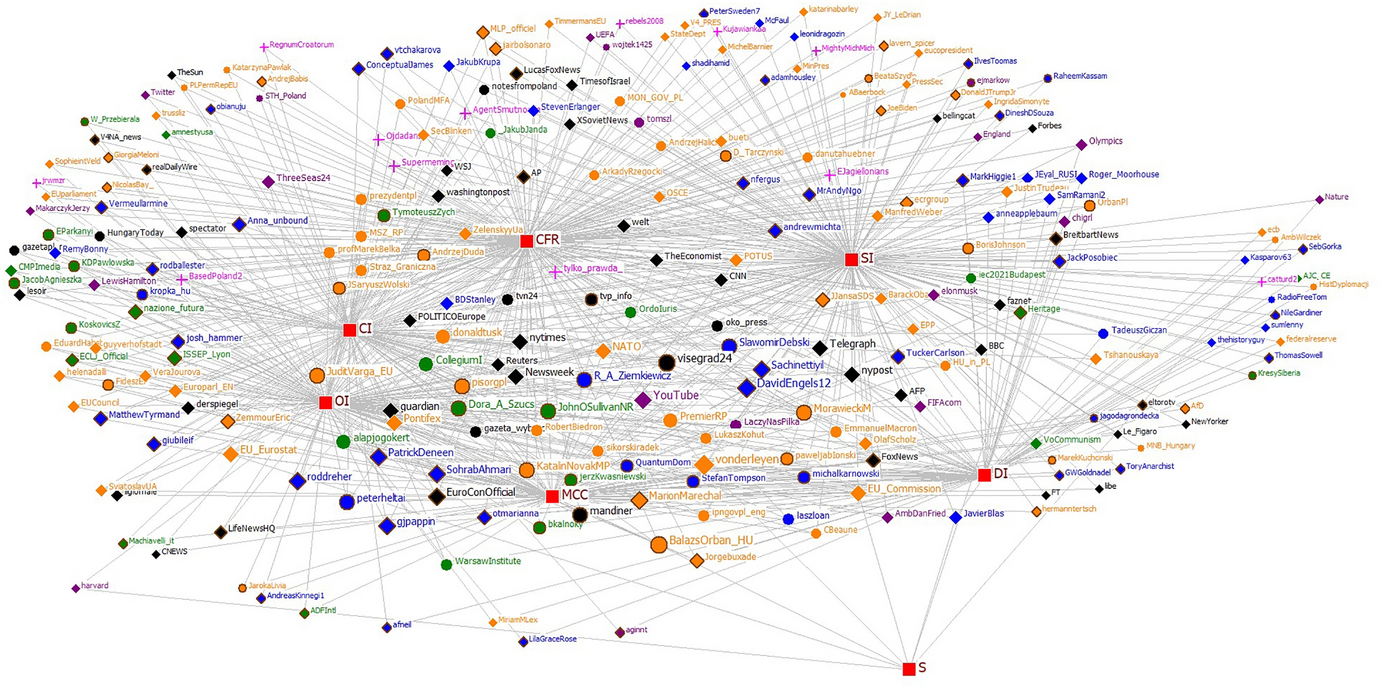

To broaden the focus, in Fig. 3 we illustrate the accounts having at least one interaction with both a Polish and a Hungarian think tank. This figure shows how the analyzed think tanks act as builders of a transnational illiberal field connecting a variety of European and American actors, ranging from civil society organizations, political elites, media, and intellectuals. Intellectuals are the largest category (23% of accounts), strengthening our argument about the centrality of their role within the emerging illiberal field. The selected think tanks interacted with center-left, center-right, and liberal political actors (7.1%), as well as to governmental institutions (22.6%), but also to illiberal elites (6.8%). This emerging field involves European (i.e., Giorgia Meloni, Janez Janša, Eric Zemmour, Nicolas Bay, Marion Maréchal, Marine Le Pen) and international illiberal actors (i.e., Jair Bolsonaro, Donald Trump Jr.), as well as other parties from the far-right sphere, including mentions of Alternative für Deutschland and VOX members of the European Parliament (i.e., Jorge Buxadé and Hermann Tertsch).

Fig. 3 Online interactions of the accounts mentioned by at least one Polish and one Hungarian think tank. Note: Red squares show seeding accounts. As far as target accounts are concerned, circles denote national accounts (31.4%), diamonds indicate foreign ones (64%), and crosses indicate accounts that cannot be identified (i.e., anonymous) (4.6%). Blue is assigned to intellectuals (23.4%); green is reserved for think tanks and associated experts (10.7%); black indicates media accounts (18%); orange designates institutional (22.2%) and political elite accounts (13.4%); pink indicates anonymous/trolling accounts (4.6%); and lastly, purple designates accounts in the miscellaneous and residual category (7.7%). Finally, the nodes that are marked with a brown outline are those associated with an illiberal milieu.

Secondly, think tanks are connected with reliable media (15%) alongside unreliable news outlets (4.5%). The field is diverse, including national, European, and American media outlets. Among them are the US-based LifeNews (self-defined as “a pro-life news outlet fighting abortion”), Breitbart News (the sponsor of Donald Trump and central outlet for the American and international far right), and the Daily Wire (another key American far-right media founded by the conservative intellectual Ben Shapiro, already editor-at-large of Breitbart). A very central node in the Hungarian and Polish field is represented by visegrad24. This account, whose nature is opaque as it does not produce any written articles and its editorial structure is unknown, counts more than 800,000 followers on Twitter and in recent years became one of the most followed news sources in the region. The account has been described as a spreader of disinformation and fake news, and is depicted as being very close to the PiS-led cabinet (OKO Press 2022; Visegrad Insight 2023).

Thirdly, ties also exist with other think tanks and civil society organizations (9%), again including national American organizations such as the Alliance Defending Freedom, which promotes Christian values, and the influential conservative and neoliberal think tank, the Heritage Foundation. Two conservative Italian think tanks are also part of the field: the Centro Studi Politici e Strategici Machiavelli, which is focused on migration issues and is associated with Lega and Nazione Futura, led by Francesco Giubilei (mentioned in the next section), and also associated with Brothers of Italy. Another think tank mentioned by both the Polish and Hungarian organizations is the European Centre for Law and Justice, which is active in promoting legal actions against abortion, gay marriage, and euthanasia and is considered a “fundamentalist Christian organization” (Le Monde 2020). The field also brings into the fold the Institut des sciences sociales, économiques et politiques, founded by Marion Maréchal in 2018 with the aim of attracting conservative intellectuals, which is linked to Eric Zemmour’s political project and has staff linked to the Rassemblement National in France.

Illiberal think tanks as disseminators and legitimizers of the illiberal cultural hegemony

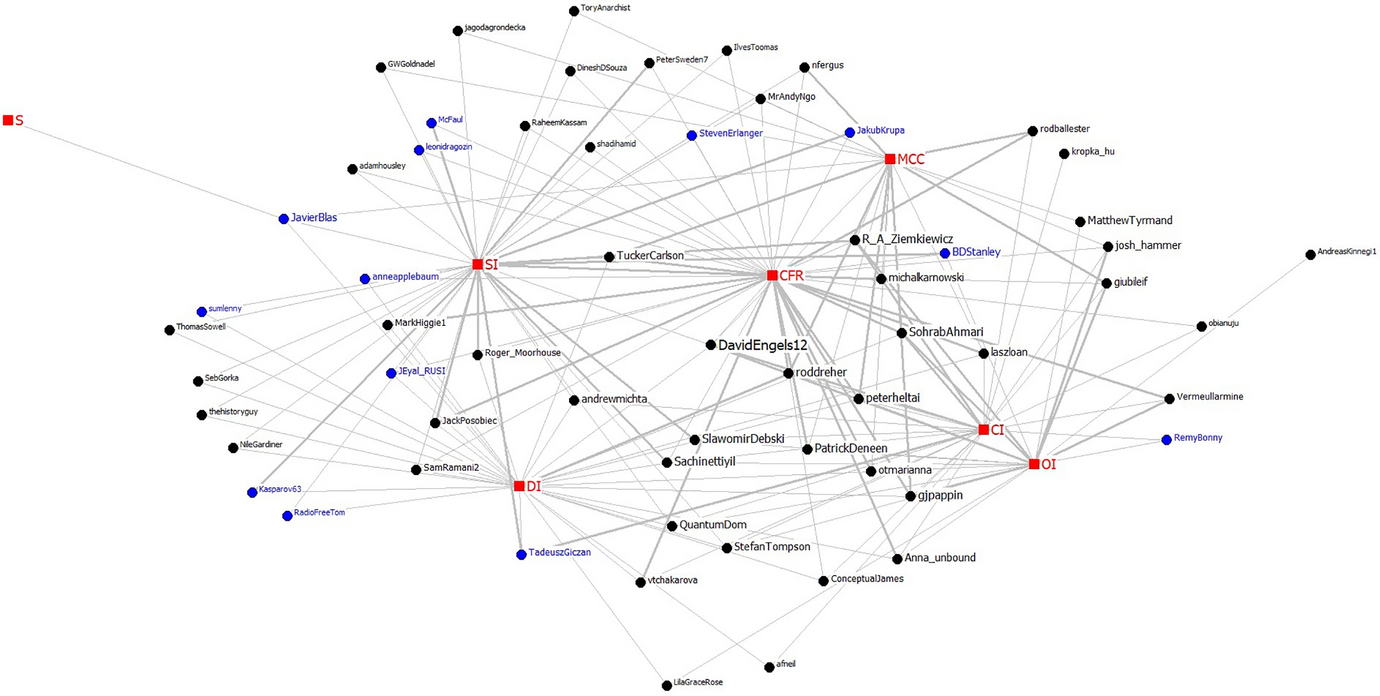

Through their interactions with national, European, and American intellectuals, think tanks serve as disseminators—rather than producers—of illiberal ideas and legitimizers of a new counter-hegemonic project against liberal democracy. To do so, they rely on the cultural capital of journalists, university professors, experts, and lobbyists, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4 Think tank interactions with intellectuals (accounts mentioned by at least one Polish and one Hungarian think tank). Note: Red squares indicate the seeding accounts. As far as target accounts are concerned, black circles denote the intellectuals positively mentioned within the illiberal network, while blue circles show those presenting an antagonistic stance.

While Behr (Reference Behr2023) has shown how Polish conservative intellectuals and political actors have become “producers of ideas” traveling from the periphery to the core, our analysis illustrates that in addition to this trend, American and European intellectuals have also found a space in Central and Eastern Europe to diffuse their ideas, after adopting “a more defensive posture in American politics since 2008” (Pappin Reference Pappin, Sajo, Uitz and Holmes2022: 50). Some have even found new professional opportunities in these countries, as illustrated below. Figure 4 zooms in to show how both the Polish and the Hungarian think tanks disseminate ideas and how American intellectuals contribute to the critique of liberal democracy from different perspectives. Most of the names in Fig. 4 are central conservative and neoconservative intellectual figures, holding university positions and academic degrees and acting as legitimizers of contemporary illiberalism.

Patrick Deneen is an American political theorist, a former professor at Georgetown University now based at the University of Notre Dame and the author of Why Liberalism Failed (Reference Deneen2018). His book, which was acclaimed in conservative circles (Plattner Reference Plattner, Vormann and Weinman2021), is an illustration of the counter-hegemony intellectual movement in which he argues that liberal democracy is defunct and needs to be replaced, while liberalism is accused of creating moral decline and destroying family, traditions, and religion. Outside of academia, Deneen’s work has been a sort of ideological compass for far-right movements looking for an informed intellectual critique of liberalism. His book has been translated into Hungarian and was launched at an event in the country, prior to which Deneen had a meeting with Viktor Orbán. On this occasion, he declared that the Hungarian government represents an example for US conservative circles (Hungary Today 2019) of an intellectual legitimization of politics, in addition to the academic legitimatization of the emerging counter-hegemony. Being invited to lecture at both the MCC and at Collegium Intermarium, through his ideas Deneen connects the Polish and the Hungarian illiberal fields into a transnational one.

Next to Deneen in Fig. 4, we find another American conservative intellectual: Rod Dreher, currently residing in Hungary and listed as an expert at the Danube Institute. He is the former editor-in-chief of The American Conservative and has been published in The European Conservative, a Fidesz-affiliated English-language magazine. He is the intellectual with the highest number of cross-national references. Like Deneen, he is present both in the Polish and the Hungarian national fields, being invited to speak at the MCC and the Polish Collegium Intermarium on multiple occasions. On Twitter, his account has had interactions with CFR, Collegium, Danube Institute, Ordo Iuris, and MCC’s affiliates.

Another example is Gladden Pappin, a political theorist with a PhD from Harvard University who used to be an associate professor at the University of Dallas. He is the director of the Hungarian Institute of International Affairs, a state-owned research institute that provides analyses and advice to the Hungarian government regarding foreign policy.Footnote 7 He was a former visiting fellow at the MCC and an invited lecturer at Collegium Intermarium.

Figure 4 also captures the presence of European academics often invited by both Collegium Intermarium and the MCC: Andreas Kinneging, Professor of law at the University of Leiden; David Engels, former chair of Roman history at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB) and Research Professor at the Instytut Zachodni (Poznań); and the British historian Niall Ferguson, Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, and a senior faculty fellow at Harvard, who was an invited speaker at the MCC’s annual opening ceremony in 2021. Ferguson’s book, Civilization: The West and the Rest (Reference Ferguson2011), about the imminent economic and political rise of the East against the West has influenced the Hungarian political elite, including Prime Minister Orbán (Euronews 2021).

Frank Füredi, Emeritus Professor of Sociology at the University of Kent, is the head of the Brussels branch of the MCC. He accepted the position because “It’s a chance to fight back in the culture wars.” In an interview for Foreign Policy (2023), Füredi directly cited Gramsci’s notion of cultural hegemony, arguing that “the long-term survival of the kind of project that he [Orbán] has requires a degree of intellectual hegemony within society, […] So he [Orbán] needs to create a counter intelligentsia, a counter intellectual elite, if they’re going to be able to create the foundation for a more durable sort of political regime.”

The presence of certain names in Fig. 4 may come as a surprise: The historian Anne Applebaum has repeatedly been accused of “intellectual dishonesty” by CFR affiliates, and the political scientist Ben Stanley was criticized by Jakub Kumoch (affiliated with the Sobieski Institute) for his position on the independence of the Polish judiciary. Others have been endorsed mostly for their positions on the invasion of Ukraine or for economic news reporting (e.g., Gary Kasparov, Javier Blas).

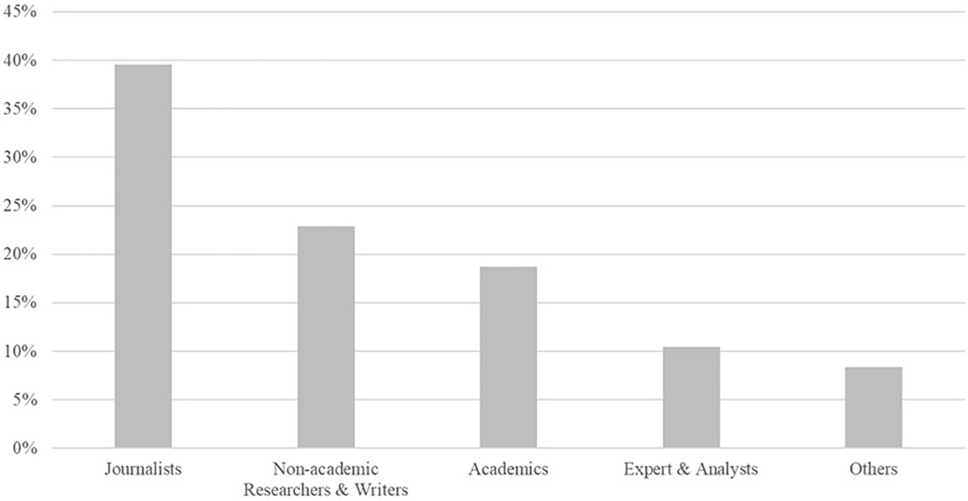

In terms of numbers, as Fig. 5 shows, journalists emerge as more numerous than academics in the emerging transnational illiberal field, followed by non-academic researchers, experts, and analysts. Among the influential American journalists is the far-right anchor-man Tucker Carlson, known for having succeeded in introducing far-right ideas into the mainstream political discourse of American politics. In August 2023, Carlson participated in MCC Fest, and on that occasion interviewed the prime minister, Viktor Orbán. Some of the journalists in Fig. 4 are also authors of books and essays, such as Andy Ngo, an influential right-wing American journalist who published Unmasked: Inside Antifa’s Radical Plan to Destroy Democracy (Reference Ngo2021). His book was published in Hungarian by Századvég and was launched in August 2021 at an event at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw, an institution promoting right-wing artists and heavily financed by PiS (Stasiniski 2023); the event was also attended by other illiberal Polish intellectuals such as Rafał Ziemkiewicz (see below). The field also includes domestic journalists such as Michał Karnowski, the main editor of wPolityce.pl, a right-wing media source that is supportive of PiS, and Mariann Őry, a columnist at the far-right Hungarian journal Demokrata. In addition to covering Hungarian foreign policy for Demokrata, Őry is the editor of Eurasia Magazine, which promotes connectivity between Eastern autocracies and the West.

Fig. 5 Professional backgrounds of actors with academic and cultural capital. Note: N = 48

In addition to academics and journalists, the emerging transnational illiberal field also features the presence of writers, activists, and opinion makers. Rafał Ziemkiewicz is a sci-fi writer who engages in intense activity as a far-right publicist and regularly writes for Do Rzeczy. His works overtly discuss several racist, anti-Semitic, and holocaust-denialist theses (Algemeiner 2021). He has been a lecturer at Collegium Intermarium, and on Twitter he also interacts with CFR, the Danube Institute, Ordo Iuris, and MCC’s affiliates. CFR, Collegium Intermarium, Ordo Iuris, and MCC also share several connections with the Polish-American Matthiew Tyrmand, founder of the right-wing US activist group Project Veritas, which he left in the summer of 2023. He has been invited to give lectures at both MCC and Collegium Intermarium and has collaborated with several Polish and English-language media outlets such us Do Rzeczy, Breitbart, The American Conservative, and The European Conservative. Francesco Giubilei is a young conservative Italian writer and journalist who briefly served as advisor to the Italian Ministry of Culture during the far-right Meloni-led cabinet; he has often been quoted or retweeted by the MCC, CFR, Ordo Iuris, and Collegium Intermarium. Giubilei was a visiting fellow at the MCC and was invited by Collegium Intermarium to be on a panel on “cancel culture.” Another figure with several interactions with CFR, the Collegium Danube Institute, Ordo Iuris, and MCC’s affiliates is Anna Wellisz, a member of the Edmund Burke Foundation and organizer of the National Conservatism conferences. She worked for the Washington PR agency, White House Writers Group, which has received $5.5 million in funding since 2017 to improve the Polish government’s reputation in the US (Politico 2019). Nile Gardiner, the Director of the Margaret Thatcher Centre for Freedom at the Heritage Foundation, has interacted with both Danube and Sobieski Institute affiliates.

Conclusions

Think tanks provide fertile ground for studying actors of dissensus over liberal democracy beyond political parties. This article brings together several empirical and theoretical findings and underscores the value of using field analysis to understand the emergence of a counter-hegemony process.

To begin with, the article maps the rise of an illiberal field in which think tanks play a key role, acting as mediators between different types of actors such as radical right political figures and institutions, media outlets and journalists, and other think tanks, as well as trolls and anonymous accounts linked to far-right movements. This field reveals the centrality of intellectuals, who fuel dissensus over liberal democracy through their critiques and counter-hegemony stance. Diffusing their ideas, think tanks act as legitimizers of the illiberal project by drawing on their cultural capital. While the MCC and the Danube Institute in Hungary, and Ordo Iuris and Collegium Intermarium in Poland are well connected with national, European and American intellectuals, others such as the CFR in Hungary and the Sobieski Institute in Poland exhibit Twitter activity linked to anonymous accounts—often troll accounts that hide behind a mask of anonymity promoting nationalist, xenophobic, supremacist, racist, and sometimes overtly anti-Semitic claims. Overall, the emerging field is permeable to—and in certain cases aims to attract—foreign actors and key intellectual figures of contemporary illiberalism who support political figures in the two countries.

Despite some cross-national commonalities, some key differences distinguish the two cases. Hungarian think tanks display more structured connections with foreign intellectuals and explicit ties to the Fidesz government, while the Polish illiberal field is predominantly based on domestic voices, pundits, and intellectuals (Fig. 2).

It should be noted that the methodology used here entails some limitations, as our analysis relies exclusively on Twitter data. First, a marked imbalance emerged between Polish and Hungarian think tanks, with the former being much more present on Twitter than the latter. Data from the web traffic analysis website StatCounter reveal that during the period under investigation, compared to other social networks Twitter’s market share (measured in terms of access) was almost five times larger in Poland (7.99%) than in Hungary (1.65%).Footnote 8 Thus, further studies should expand our data by exploring other social network platforms. Second, while this article focuses on online activities, think tanks also foster important offline connections, through conferences and events, which are also relevant to capture the emergence of the transnational illiberal field and the functions performed by think tanks in this regard. Further work is needed to ascertain whether the findings of this article are paralleled by the think tanks’ offline activities. Third, although our analysis focused exclusively on Hungarian and Polish think tanks, our results unveil a vaster field of illiberal actors. Broader comparative research is needed to map the spread of the field in countries where illiberal parties have not yet acquired governmental responsibilities. Moreover, further research is needed to explore the resilience of such illiberal fields following changes in government—for example, in Poland after the 2023 election—which may weaken the economic and political sponsorship of illiberal think tanks. Finally, our data set revealed no direct connections with Russia and China. Despite some evidence of the reinforcement of economic ties between Hungary and Russia and a growing sympathy linking Viktor Orbán and the Kremlin (Politico 2024), our study suggests that the illiberal cultural milieu is dominated by American and European voices. This supports Buzogány's argument (Reference Buzogány2017) that Fidesz's illiberalism is neither inspired nor actively and directely supported by Russian actors. To fully map interactions with non-Western actors, further exploration of offline connections is needed.

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-025-00544-6.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Balázs Gaál for his insightful support in clarifying some details of the Hungarian actors. Additionally, the authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their clever remarks and the EPS editors for facilitating a smooth revision process. This publication received funding from the European Union's Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under the Call HORIZON-C12-2021-DEMOCRACY-01 as part of the research project RED-SPINEL (Grant agreement n°101061621), coordinated by Ramona Coman as PI at the Institut d’études européennes of the Université libre de Bruxelles.

Author Contribution

R. Coman and L. Puleo developed the research and theoretical framework and drafted the paper, while E. Paulis and N. Trino primarily contributed to data collection and visualization.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium.