Introduction

Volunteerism has proliferated over the last decades, with sports and cultural institutions as predominant scenarios (Baert & Vujić, Reference Baert and Vujić2016). More specifically, according to the Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building, and Community ([BMI] 2021b), more than 30 million citizens are serving as volunteers in Germany. Voluntary engagement is considered as the “backbone of society” (BMI, 2021a). Volunteering fosters societal integration, welfare, cultural life, stable democratic structures and social relationships. It is considered as enrichment of society. Hence, the government should provide the necessary support to facilitate volunteering (BMI, 2021a). In Germany, the majority of individuals volunteer in sports (13.5%) and culture and music (8.6%), according to the 2019 Volunteer Survey (Simonson et al., Reference Simonson, Kelle, Kausmann and Tesch-Römer2021). These activities have been core areas for volunteers since 1999—the first wave of the German Volunteer Survey—with volunteerism increasing in these areas (Simonson et al., Reference Simonson, Kelle, Kausmann and Tesch-Römer2021).

Volunteering encompasses an array of activities as “in which time is given freely to benefit another person, group, or organization” (Wilson, Reference Wilson2000, p. 215). Volunteers are essential for the sustainability of sport and culture (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Liu and Legget2019; Colibaba & Skinner, Reference Colibaba and Skinner2019; Hallmann, Reference Hallmann2015; Schlesinger & Nagel, Reference Schlesinger and Nagel2013). Hence, more research is necessary on the context in which time is allocated (Bussell & Forbes, Reference Bussell and Forbes2002). The decision to volunteer or not volunteer in a leisure activity is at the core of this study. This study explores whether different forms of volunteering are mutually linked.

Understanding the determinants of volunteering in sports and cultural activities is central as volunteers are an irreplaceable human resource (Schlesinger & Nagel, Reference Schlesinger and Nagel2013; Toraldo et al., Reference Toraldo, Contu and Mangia2016). Though participation rates are high (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Garris and Aldamer2018), nonprofit organizations have traditionally been considered competing for resources (De Clerck et al., Reference De Clerck, Willem, Aelterman and Haerens2019) as individuals can donate their time in diverse environments (Gil-Lacruz et al., Reference Gil-Lacruz, Marcuello and Saz-Gil2019). Thus, substitutability is often assumed as individuals have limited time resources (Becker, Reference Becker1965). While this is assumed, it has not been empirically tested. Volunteering has been studied chiefly separately for various societal areas, such as culture, education, health, or sports (Cantillon & Baker, Reference Cantillon and Baker2020; Misener et al., Reference Misener, Morrison, Shier and Babiak2020; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Menneer, Leyshon, Leyshon, Williams, Mueller and Taylor2020; Wu & Tsai, Reference Wu and Tsai2017). Nonetheless, the relationship between volunteering and other leisure activities has been analyzed (Downward et al., Reference Downward, Hallmann and Rasciute2020; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Dury, Mohan, Stebbins, Smith, Stebbins and Grotz2016).

A potential substitution pattern can be analyzed by simultaneously estimating two dependent binary variables. Therefore, this analysis aims to determine whether volunteering in sport and culture are unrelated decisions or whether they are linked as identified for participation in those activities (Hallmann et al., Reference Hallmann, Artime, Breuer, Dallmeyer and Metz2017). A special feature of the analysis is its assessment of joint probabilities. Thereby, we derive profiles of individuals who volunteer in both areas, only in one of the two areas and in none of the two areas. Hence, the study estimates the relationship between sport and cultural volunteering, including a set of independent variables that determine these decisions. The simultaneous estimation of those decisions is a valuable contribution to research and makes this study original. This analysis can help identify whether the decision to volunteer in sports and culture is related or not as it allows for correlation between unobserved factors affecting both decisions. Though some studies looked at the relationship between sports and cultural activities in general (Hallmann et al., Reference Hallmann, Artime, Breuer, Dallmeyer and Metz2017; Long & Bianchini, Reference Long and Bianchini2019; Muñiz et al., Reference Muñiz, Rodríguez and Suárez2014), the realms of sport and culture were seldom discussed simultaneously (Ekholm & Lindström Sol, Reference Ekholm and Lindström Sol2020).

Therefore, there is a need to understand better the relationship between those areas. Importantly, a joint analysis would be very informative for volunteer managers. Cultural and sport stakeholders could benefit from recruiting and retaining volunteers (Bussell & Forbes, Reference Bussell and Forbes2002). Moreover, policies related to sport and culture could benefit from cooperating as culture and sport have been linked to potential benefits for individuals and society (Ellis Paine et al., Reference Ellis Paine, Allum, Beswick and Lough2020). Subsequently, both fields help facilitate social policy goals.

Theoretical Framework

Volunteering is a complex term that encompasses different types of activities and engagement (Burgham & Downward, Reference Burgham and Downward2005). While no consensus exists on the meaning, four central components have been identified: free choice, no monetary rewards, formal organization, and proximity to recipients (Haski-Leventhal, Reference Haski-Leventhal2009). Theoretically, volunteering has been typically approached from two perspectives. The economic model considers the volunteers as a resource and as unpaid workers. Conversely, the leisure model considers volunteering as a leisure activity. Volunteering is a freely elected participation and can thus be considered a paradigm of choice (Overgaard, Reference Overgaard2019). According to the economic model, the individual’s time can be allocated into four categories: paid work, unobligated free time, obligatory time (e.g., sleeping), and work-related time (e.g., commuting). Consequently, assuming that volunteering results from a leisure time choice, we argue that volunteering can be accounted for by the decision-making framework (Edwards, Reference Edwards2005; Hallmann et al., Reference Hallmann, Downward and Dickson2018; Wicker & Hallmann, Reference Wicker and Hallmann2013).

The theory of time allocation (Becker, Reference Becker1965) has prompted analyzing a range of time allocation decisions. One extension of the time allocation model concerns trade-offs in time use (Clain & Zech, Reference Clain and Zech2008). It can be applied to examining the relationship between volunteering in the sports and cultural sectors. In the simplest model, individuals choose between consuming market goods or time and confront a time-budget constraint by devoting their time to an activity that yields no earnings (Burgham & Downward, Reference Burgham and Downward2005). This model, known as the household production model, is founded on the premise that individuals combine time and goods to produce basic commodities that bring utility to the individual. The time allocation household production model argues that an individual’s time can be allocated to leisure activities, work, and home-based production activities (Govekar & Govekar, Reference Govekar and Govekar2002).

Therefore, this model in which the distinction between “consumption” and “production” is removed has been considered as a feasible approach for serious leisure activities that combine production and consumption (Crouch & Tomlinson, Reference Crouch, Tomlinson and Henry1994). Consequently, the household production theory has been extended to account for volunteering decisions (Vaillancourt & Payette, Reference Vaillancourt and Payette1986). Individuals choose between consuming goods or time and confront a time-income constraint by devoting their time to an activity that yields no income (Burgham & Downward, Reference Burgham and Downward2005). However, not only socioeconomic variables constraint the allocation of time. Socio-demographic, sociocultural, and environmental variables can serve as constraints in a volunteering context, as demonstrated previously (e.g., Burgham & Downward, Reference Burgham and Downward2005; Hallmann et al., Reference Hallmann, Downward and Dickson2018; Wicker & Hallmann, Reference Wicker and Hallmann2013). One extension concerns trade-offs in time use (Clain & Zech, Reference Clain and Zech2008). This paper examines this trade-off in time use by examining the decisions to sport and cultural volunteering simultaneously, which is original.

Literature Review

Few studies compared different types of volunteering (or organizations to volunteer for), though some exceptions (e.g., Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Bredtmann and Schmidt2013; Eimhjellen et al., Reference Eimhjellen, Steen-Johnsen, Folkestad, Ødegård, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018) exist. Sports event volunteering (e.g., Cho et al., Reference Cho, Li and Wu2020; Kerwin et al., Reference Kerwin, Warner, Walker and Stevens2015) and sports club volunteering (e.g., Misener et al., Reference Misener, Morrison, Shier and Babiak2020; Nagel et al., Reference Nagel, Seippel, Breuer, Feiler, Elmose-Østerlund, Llopis-Goig, Nichols, Perényi, Piątkowska and Scheerder2019) have been extensively analyzed. Yet, cultural volunteering (e.g., Bachman et al., Reference Bachman, Norman, Backman and Hopkins2017; Cantillon & Baker, Reference Cantillon and Baker2020; Vinnicombe & Wu Yu, 2020) is less researched. The majority of these studies were cross-sectional. Overall, the literature looked into various aspects of volunteering at the individual, organizational, and environmental levels (see Wicker, Reference Wicker2017 for an overview regarding sport volunteering). However, the studies commonly analyzed either sports or cultural volunteering and not their relationship, the latter being the main contribution of this analysis. We analyze volunteering accounting for several determinants. The analysis is informed by the household production theory and its extensions for environmental and sociocultural variables studying the decision to volunteer (Burgham & Downward, Reference Burgham and Downward2005; Hallmann et al., Reference Hallmann, Downward and Dickson2018; Wicker & Hallmann, Reference Wicker and Hallmann2013).

Socio-demographic Determinants

Findings regarding age were heterogeneous, which might be related to different volunteering contexts. Schlesinger and Nagel (Reference Schlesinger and Nagel2018) did not find an age effect on voluntary commitment in voluntary sports clubs. However, Dawson and Downward (Reference Dawson and Downward2013) and Taylor et al. (Reference Taylor, Panagouleas and Nichols2012) found that the probability of volunteering in sport declines with aging and an inverse u-form relationship was also identified for sport (Eimhjellen et al., Reference Eimhjellen, Steen-Johnsen, Folkestad, Ødegård, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018). Arts and culture volunteers were older than volunteers in other sectors (Deery et al., Reference Deery, Jago and Mair2011; Wymer & Brudney, Reference Wymer and Brudney2000). A priori, we expect the following:

H1

Age is positively correlated with cultural volunteering and negatively correlated with sports volunteering.

In terms of gender, some patterns were evident. Overall, many studies report a gender bias, with females volunteering more than males (Bussell & Forbes, Reference Bussell and Forbes2002). Other studies identified that male gender is positively correlated with overall sports volunteering (Dawson & Downward, Reference Dawson and Downward2013; Eimhjellen et al., Reference Eimhjellen, Steen-Johnsen, Folkestad, Ødegård, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Panagouleas and Nichols2012), though females volunteer more (Burgham & Downward, Reference Burgham and Downward2005; Hallmann et al., Reference Hallmann, Downward and Dickson2018). However, apart from the sports sector, the involvement of women in volunteering is increasing (Boje et al., Reference Boje, Hermansen, Møberg, Strømsnes and Svedberg2019). Volunteering was predominantly female in the cultural industry (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Liu and Legget2019).

H2

Female gender is positively correlated with cultural volunteering and male gender is positively correlated with sports volunteering.

Ethnic background can also shape volunteering as individuals might not be able to engage for reasons related to this background (Amara & Henry, Reference Amara and Henry2010). Hylton et al. (Reference Hylton, Lawton, Watt, Wright and Williams2019) documented that black, Asian, and minority ethnic individuals are underrepresented as volunteers in the UK. This applies particularly to British Asian (Hylton et al., Reference Hylton, Lawton, Watt, Wright and Williams2019). Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Bredtmann and Schmidt2013) revealed that being an immigrant is negatively associated with charitable labor for any leisure activity organization (including sport and culture organizations).

H3

Having a migration background is negatively correlated with cultural and sports volunteering.

A major resource of the household is disposable time. In the theoretical framework of household production, the household’s work will be allocated across the different household members (Freeman, Reference Freeman1997). Subsequently, sharing tasks allows all members to volunteer more time (Nesbit, Reference Nesbit2013). Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Bredtmann and Schmidt2013) revealed that the number of household members was positively correlated with volunteering for leisure organizations. Theoretically, this could be linked to the extension of the household production model that accounts for social interactions (Becker, Reference Becker1976). Thus, socialization with other family members nurtures socialization into activities like volunteering.

H4

Non-single households are positively correlated with cultural and sports volunteering.

The household composition is also associated with volunteering behavior. Married people and those with children were more willing to volunteer (Musick & Wilson, Reference Musick and Wilson2008). Having children is positively correlated with volunteering for sports organizations (Eimhjellen et al., Reference Eimhjellen, Steen-Johnsen, Folkestad, Ødegård, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Panagouleas and Nichols2012), or leisure organizations (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Bredtmann and Schmidt2013). If children or partners are involved in sports and cultural activities, the individual is likely to support volunteering in these activities. However, caring for very young children can result in a major time constraint. Considering the marital status, previous findings vary. Yet, more evidence suggested a positive correlation between being married and volunteering (e.g., Grizzle, Reference Grizzle2015).

H5

Having children old enough to participate in culture and sport activities is positively correlated with cultural and sports volunteering.

H6

Being married is positively correlated with cultural and sports volunteering.

Socioeconomic Determinants

Higher education is commonly related to human capital. Research confirmed that higher education is positively associated with sports volunteering (Dawson & Downward, Reference Dawson and Downward2013; Eimhjellen et al., Reference Eimhjellen, Steen-Johnsen, Folkestad, Ødegård, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Panagouleas and Nichols2012) and other volunteering (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Bredtmann and Schmidt2013; Eimhjellen et al., Reference Eimhjellen, Steen-Johnsen, Folkestad, Ødegård, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018).

H7

Higher education is positively correlated with cultural and sports volunteering.

Employment can constrain volunteering and people who work full time have less time for volunteering (Wicker, Reference Wicker2017). Burgham and Downward (Reference Burgham and Downward2005) found no correlation between full-time employment and sports volunteering but between full-time employment and time allocated to sports volunteering. Similarly, leisure volunteering was positively correlated with being employed (Downward et al., Reference Downward, Hallmann and Rasciute2020). Income was positively correlated with sports volunteering (Eimhjellen et al., Reference Eimhjellen, Steen-Johnsen, Folkestad, Ødegård, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018; Thibault & Scheerder, Reference Thibault, Scheerder, Hallmann and Fairley2018). Research also identified no effect of income on volunteering for leisure activity organizations (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Bredtmann and Schmidt2013), and general volunteering (Eimhjellen et al., Reference Eimhjellen, Steen-Johnsen, Folkestad, Ødegård, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018).

According to the neoclassical framework on decision-making, volunteering is more readily affordable for those with higher incomes as the more affluent would continue earning high levels of income despite the time spent on volunteering. Conversely, higher incomes imply a higher opportunity cost of volunteering, creating incentives for work and discouraging volunteering (Burgham & Downward, Reference Burgham and Downward2005).

H8

Being employed is positively correlated with cultural and sports volunteering.

H9

Higher income is positively correlated with cultural and sports volunteering.

Environmental Determinants

Several studies found that environmental factors matter (Hallmann et al., Reference Hallmann, Downward and Dickson2018; Schlesinger & Nagel, Reference Schlesinger and Nagel2013, Reference Schlesinger and Nagel2018). Sports volunteering and volunteering for leisure activity organizations were more likely in smaller communities (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Bredtmann and Schmidt2013). Ishida and Okuyama (Reference Ishida and Okuyama2015) found no support for the size of the city and charitable giving for civil society organizations, but attachment to the local society was correlated with charitable giving. The positive effect of smaller communities could be related to social capital accruement through volunteering (Chalip, Reference Chalip2006). This is easier to accomplish in smaller communities than in larger and more anonymous regions (Hallmann et al., Reference Hallmann, Downward and Dickson2018). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H10

Smaller regions are positively correlated with sports and cultural volunteering.

Sociocultural Determinants

Religiosity (as a proxy for cultural capital) and participation in a religious group were positively correlated with volunteering (Wilson & Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick1997). The positive relationship of individual church attendance was mostly supported in previous studies as religious practices build social interactions (Prouteau & Sardinha, Reference Prouteau and Sardinha2015). This leads to the following hypothesis:

H11

Belonging to a religious group is positively correlated with sports and cultural volunteering.

Parents often serve as role models for their children to participate in sports and cultural activities (Coleman et al., Reference Coleman, Cox and Roker2008; van Hek & Kraaykamp, Reference van Hek and Kraaykamp2015). The simultaneous parental participation was also significant for cultural participation of children (van Hek & Kraaykamp, Reference van Hek and Kraaykamp2015). Children’s and adolescents’ volunteer participation is also correlated to parental volunteering (García Mainar et al., Reference García Mainar, Marcuello Servós and Saz Gil2015).

H12

Previous parental volunteering is positively correlated with sports and cultural volunteering.

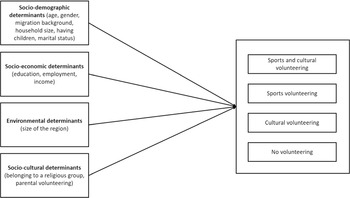

Figure 1 presents the study’s theoretical model informed by the household production theory and various extensions taking a behavioral perspective to decision-making theory applied to volunteering (e.g., Burgham & Downward, Reference Burgham and Downward2005; Hallmann et al., Reference Hallmann, Downward and Dickson2018; Wicker & Hallmann, Reference Wicker and Hallmann2013).

Fig. 1 Theoretical Model

Methods

Measures

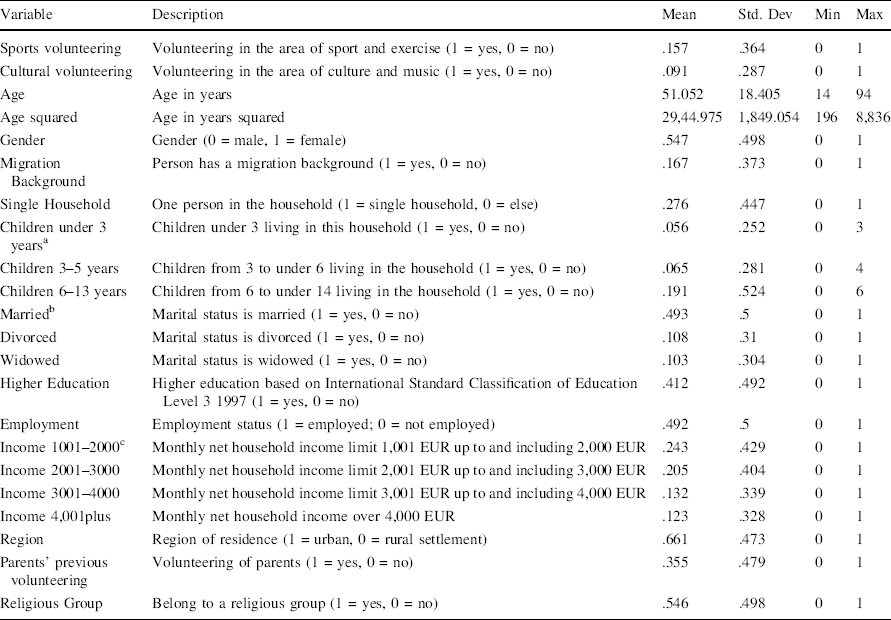

The authors sourced secondary data from the 2014 German Volunteer Survey (Deutsches Zentrum für Altersfragen, 2019). The survey included sports and cultural volunteering questions, queried as dichotomous options (1 = yes). The query related to volunteering in sport and exercise, respectively, culture and music. These two variables served as dependent variables.

The explanatory variables included socio-demographic information. Age and age squared were used to test for potential nonlinear relationships. Moreover, gender, migration background, marital status, household size, and children in various age categories in the household were included. Higher education, employment, and income were included as socioeconomic variables. The variable region (i.e., living in an urban or rural settlement) presented the environmental factor. Finally, the sociocultural variables were parents’ previous volunteering and religious group (see Table 1).

Table 1 Overview of variables and summary statistics (for binary variables, proportions are displayed)

Variable |

Description |

Mean |

Std. Dev |

Min |

Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sports volunteering |

Volunteering in the area of sport and exercise (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

.157 |

.364 |

0 |

1 |

Cultural volunteering |

Volunteering in the area of culture and music (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

.091 |

.287 |

0 |

1 |

Age |

Age in years |

51.052 |

18.405 |

14 |

94 |

Age squared |

Age in years squared |

29,44.975 |

1,849.054 |

196 |

8,836 |

Gender |

Gender (0 = male, 1 = female) |

.547 |

.498 |

0 |

1 |

Migration Background |

Person has a migration background (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

.167 |

.373 |

0 |

1 |

Single Household |

One person in the household (1 = single household, 0 = else) |

.276 |

.447 |

0 |

1 |

Children under 3 yearsa |

Children under 3 living in this household (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

.056 |

.252 |

0 |

3 |

Children 3–5 years |

Children from 3 to under 6 living in the household (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

.065 |

.281 |

0 |

4 |

Children 6–13 years |

Children from 6 to under 14 living in the household (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

.191 |

.524 |

0 |

6 |

Marriedb |

Marital status is married (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

.493 |

.5 |

0 |

1 |

Divorced |

Marital status is divorced (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

.108 |

.31 |

0 |

1 |

Widowed |

Marital status is widowed (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

.103 |

.304 |

0 |

1 |

Higher Education |

Higher education based on International Standard Classification of Education Level 3 1997 (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

.412 |

.492 |

0 |

1 |

Employment |

Employment status (1 = employed; 0 = not employed) |

.492 |

.5 |

0 |

1 |

Income 1001–2000c |

Monthly net household income limit 1,001 EUR up to and including 2,000 EUR |

.243 |

.429 |

0 |

1 |

Income 2001–3000 |

Monthly net household income limit 2,001 EUR up to and including 3,000 EUR |

.205 |

.404 |

0 |

1 |

Income 3001–4000 |

Monthly net household income limit 3,001 EUR up to and including 4,000 EUR |

.132 |

.339 |

0 |

1 |

Income 4,001plus |

Monthly net household income over 4,000 EUR |

.123 |

.328 |

0 |

1 |

Region |

Region of residence (1 = urban, 0 = rural settlement) |

.661 |

.473 |

0 |

1 |

Parents’ previous volunteering |

Volunteering of parents (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

.355 |

.479 |

0 |

1 |

Religious Group |

Belong to a religious group (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

.546 |

.498 |

0 |

1 |

Kausmann et al. (2016) provide a detailed overview about all available variables and their coding. Reference category: a Children from 14 to under 18 living in this household; b Marital status is single/unmarried; c Monthly net household income up to and including 1,000 EUR. n = 27,293

Data Collection

The German Volunteer Survey is a panel (Deutsches Zentrum für Altersfragen, 2019). However, we only worked with 2014 cross-sectional data consisting of 28,690 people. This is because the earlier waves included partly other variables and were collected differently. The survey was based on a random selection of phone numbers (mobile phones and landlines). Interviews were conducted in multiple languages to approach individuals with a migration background (Simonson et al., Reference Simonson, Vogel and Tesch-Römer2016).

Data Analysis

The data included five codes for missing values: 1) refusal, 2) do not know; 3) does not apply; 4) deleted during data exploration, and 5) technical problems. Due to missing values, our sample size was 27,293. We treated the third option ‘does not apply’ as zero. For instance, if a respondent answered ‘No’ concerning whether they had people living in their household aged under 18, the subsequent questions regarding the age of children were not forwarded to the person and turned up as missing value. However, we imputed the value ‘0’ for a no answer in these cases.

A bivariate probit regression model was used to simultaneously estimate sports and cultural volunteering. This type of regression model was selected to evaluate the decision-making process to engage in volunteering. The bivariate probit addresses the simultaneous determinants of volunteering in sports and culture. Consequently, we estimated a two-equation system allowing a correlation among the unobservable factors that affect the dependent variables. In the absence of a correlation, the bivariate probit results would be identical to the estimation of two standard probits. The binary dependent variables took the value ‘1’ when the respondents volunteered in sports, respectively, culture. The model was estimated with robust standard errors to account for heteroscedasticity (White, Reference White1980). The variance inflation factors were also checked, and all values were below the threshold of 10 (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010). The bivariate probit model is nonlinear. Hence, the impact of covariates cannot be directly inferred from the estimated coefficients. The sign and magnitude of the coefficients can be challenging to interpret as they do not capture how each covariate impacts the probability of the occurrence of possible outcomes. However, the partial effects provide the impacts on the specific probabilities associated with specific categories of the dependent variables per unit change in the covariate.

Thus, we calculated the marginal effects and predicted probabilities for the four potential scenarios (i.e., volunteered in sports and culture, volunteered in sports only, volunteered in culture only, did not volunteer in sports and culture).

Results

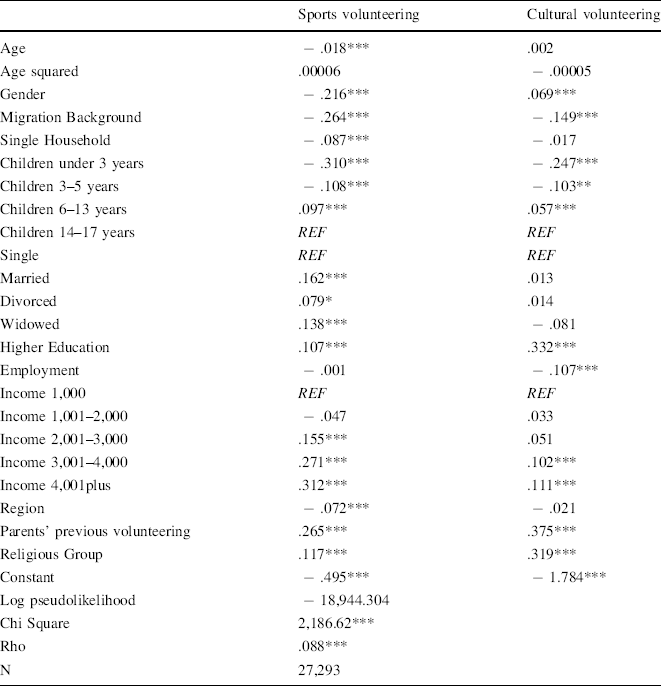

The findings confirmed most hypotheses. As the rho value illustrated, sports and cultural volunteering were complementary activities (see Table 2). Rho depicted the correlation of the error terms of cultural and sports volunteering equations and was significant (ρ = 0.088). Yet, it indicated a small correlation. The significant rho corroborates that estimating a bivariate probit is sound. If rho was not significant, estimating two separate probits would be no problem. This is a major contribution of our study since the estimation of the equations separately would not be accurate.

Table 2 Results of the bivariate probit regression (coefficients are displayed)

Sports volunteering |

Cultural volunteering |

|

|---|---|---|

Age |

− .018*** |

.002 |

Age squared |

.00006 |

− .00005 |

Gender |

− .216*** |

.069*** |

Migration Background |

− .264*** |

− .149*** |

Single Household |

− .087*** |

− .017 |

Children under 3 years |

− .310*** |

− .247*** |

Children 3–5 years |

− .108*** |

− .103** |

Children 6–13 years |

.097*** |

.057*** |

Children 14–17 years |

REF |

REF |

Single |

REF |

REF |

Married |

.162*** |

.013 |

Divorced |

.079* |

.014 |

Widowed |

.138*** |

− .081 |

Higher Education |

.107*** |

.332*** |

Employment |

− .001 |

− .107*** |

Income 1,000 |

REF |

REF |

Income 1,001–2,000 |

− .047 |

.033 |

Income 2,001–3,000 |

.155*** |

.051 |

Income 3,001–4,000 |

.271*** |

.102*** |

Income 4,001plus |

.312*** |

.111*** |

Region |

− .072*** |

− .021 |

Parents’ previous volunteering |

.265*** |

.375*** |

Religious Group |

.117*** |

.319*** |

Constant |

− .495*** |

− 1.784*** |

Log pseudolikelihood |

− 18,944.304 |

|

Chi Square |

2,186.62*** |

|

Rho |

.088*** |

|

N |

27,293 |

*p ≤ 0.1; **p ≤ 0.05; *** p ≤ 0.01; REF = Reference category

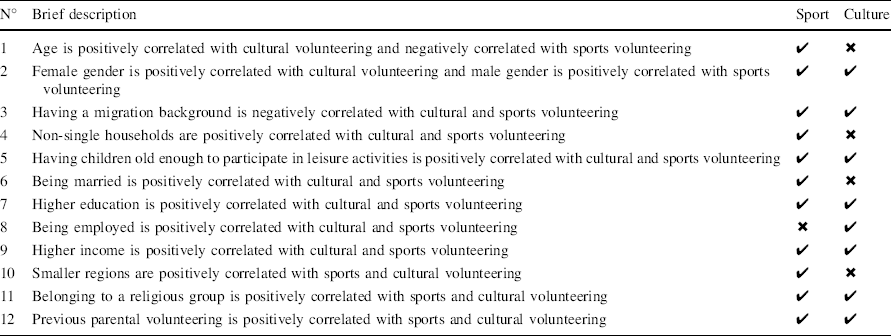

Except for H8 (positive correlation between employment and sports volunteering), all hypotheses were confirmed in the equation estimated for sport. In the equation for culture, H1, H4, H5, and H10 were not confirmed (see Table 3).

Table 3 Overview of the hypothesis testing for sports and cultural volunteering

N° |

Brief description |

Sport |

Culture |

|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Age is positively correlated with cultural volunteering and negatively correlated with sports volunteering |

✔ |

✖ |

2 |

Female gender is positively correlated with cultural volunteering and male gender is positively correlated with sports volunteering |

✔ |

✔ |

3 |

Having a migration background is negatively correlated with cultural and sports volunteering |

✔ |

✔ |

4 |

Non-single households are positively correlated with cultural and sports volunteering |

✔ |

✖ |

5 |

Having children old enough to participate in leisure activities is positively correlated with cultural and sports volunteering |

✔ |

✔ |

6 |

Being married is positively correlated with cultural and sports volunteering |

✔ |

✖ |

7 |

Higher education is positively correlated with cultural and sports volunteering |

✔ |

✔ |

8 |

Being employed is positively correlated with cultural and sports volunteering |

✖ |

✔ |

9 |

Higher income is positively correlated with cultural and sports volunteering |

✔ |

✔ |

10 |

Smaller regions are positively correlated with sports and cultural volunteering |

✔ |

✖ |

11 |

Belonging to a religious group is positively correlated with sports and cultural volunteering |

✔ |

✔ |

12 |

Previous parental volunteering is positively correlated with sports and cultural volunteering |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ = Hypothesis was confirmed; ✖ = hypothesis was not confirmed

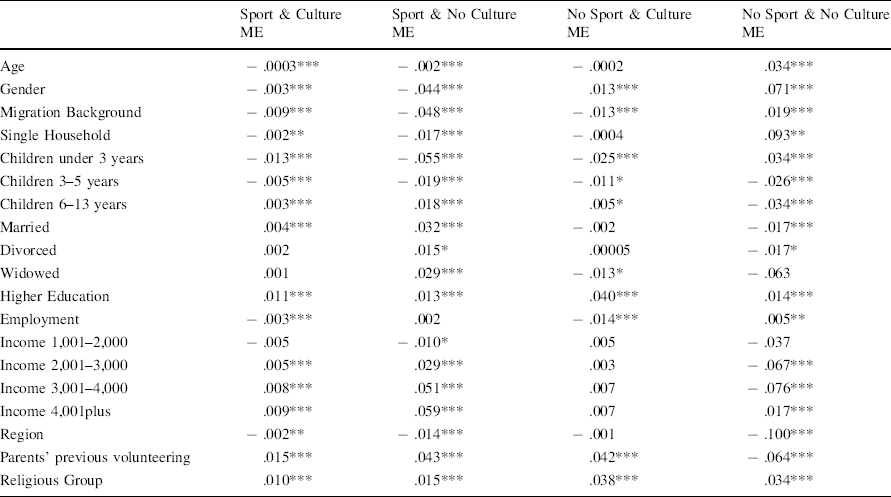

Marginal effects capture the change in the expected value of the dependent variable in each equation in response to a marginal change in an explanatory variable (this change is from 0 to 1 for binary variables). In this calculation, the rest of the covariates remained constant and the mean value was assumed (see Table 4). The first scenario looked at the joint probabilities of volunteering in sport and culture. The change in probability increased by one percentage point for those individuals with a higher educational level. A similar impact happened if the parents were volunteers or if the individual belonged to a religious group. In contrast, the probability was reduced by one percentage point if children under three years were in the household.

Table 4 Overview about joint probabilities

Sport & Culture |

Sport & No Culture |

No Sport & Culture |

No Sport & No Culture |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

ME |

ME |

ME |

ME |

|

Age |

− .0003*** |

− .002*** |

− .0002 |

.034*** |

Gender |

− .003*** |

− .044*** |

.013*** |

.071*** |

Migration Background |

− .009*** |

− .048*** |

− .013*** |

.019*** |

Single Household |

− .002** |

− .017*** |

− .0004 |

.093** |

Children under 3 years |

− .013*** |

− .055*** |

− .025*** |

.034*** |

Children 3–5 years |

− .005*** |

− .019*** |

− .011* |

− .026*** |

Children 6–13 years |

.003*** |

.018*** |

.005* |

− .034*** |

Married |

.004*** |

.032*** |

− .002 |

− .017*** |

Divorced |

.002 |

.015* |

.00005 |

− .017* |

Widowed |

.001 |

.029*** |

− .013* |

− .063 |

Higher Education |

.011*** |

.013*** |

.040*** |

.014*** |

Employment |

− .003*** |

.002 |

− .014*** |

.005** |

Income 1,001–2,000 |

− .005 |

− .010* |

.005 |

− .037 |

Income 2,001–3,000 |

.005*** |

.029*** |

.003 |

− .067*** |

Income 3,001–4,000 |

.008*** |

.051*** |

.007 |

− .076*** |

Income 4,001plus |

.009*** |

.059*** |

.007 |

.017*** |

Region |

− .002** |

− .014*** |

− .001 |

− .100*** |

Parents’ previous volunteering |

.015*** |

.043*** |

.042*** |

− .064*** |

Religious Group |

.010*** |

.015*** |

.038*** |

.034*** |

z-values refer to robust standard errors; ME =Marginal effects; *p ≤ 0.1; **p ≤ 0.05; *** p ≤ 0.01

In the second scenario focusing on “only volunteering in sport,” parents’ volunteering also played an important role. It increased by four percentage points the probability of volunteering in sports activities. Income, being a migrant, and very young children in the household were primary determinants. While higher income increased this probability by five percentage points, the latter two determinants decreased the probability by five percentage points. Being married had a positive effect by increasing the probability by three percentage points. In comparison, this probability decreased by four percentage points for females.

In the third scenario—“only volunteering in culture”—the leading determinants were educational background, parental volunteering, and religion. These factors had a beneficial effect on volunteering in culture by increasing the probability by four percentage points.

Finally, the last scenario demonstrated a logical opposite outcome to the first scenario. Parental volunteering and belonging to a religious group lowered the probability of “not volunteering in either activity” by 10 percentage points and six percentage points, respectively. The presence of minor children increased the probability by nine percentage points. Being a migrant also increased the probability of not volunteering in either activity by seven percentage points. High education and a high-income level decreased the probability by about six percentage points.

Discussion

Most hypotheses were confirmed, particularly in sport. As stated in the hypotheses, we assume that causality flows from the explanatory variables to the dependent variables. We make this assumption since cross-sectional data make it challenging to address causality. The probability of being a sports volunteer is male-dominated and decreases with aging (Dawson & Downward, Reference Dawson and Downward2013; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Panagouleas and Nichols2012). This is alarming as attracting and retaining volunteers has become a challenge partly due to an ageing population (Wicker & Breuer, Reference Wicker and Breuer2013) leading to a supply shortage in the cohort of young volunteers (Burgham & Downward, Reference Burgham and Downward2005). Moreover, sports stakeholders should account for gender as being female led to a decrease of around five percentage points in the likelihood of volunteering in “only sports.”

In contrast, cultural volunteering primarily comprised females (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Liu and Legget2019). Migrants were less likely to volunteer (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Bredtmann and Schmidt2013). This might be related to different cultural perceptions of volunteering (Fairley et al., Reference Fairley, Lee, Green and Kim2013). Though nonprofit organizations are well regarded in their attempts for inclusivity in all areas, the achievements are moderate (Vandermeerschen et al., Reference Vandermeerschen, Meganck, Seghers, Vos and Scheerder2017). Our results aligned with this, reflecting weakness in using volunteering as a means for social inclusion.

In multi-person households, volunteerism in sport was more likely. This supported Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Bredtmann and Schmidt2013) research, which investigated leisure organizations. Social interactions intra-household could be a driver for social interactions beyond the household, including volunteering (Becker, Reference Becker1976). Married people and widowers were also more likely to volunteer in sport. Likewise, households with children aged 6–13 years were more likely to volunteer in sports and culture. This is partly related to the idea that parents are willing to support their children’s sporting and cultural activities with their role as volunteers (Musick & Wilson, Reference Musick and Wilson2008). However, the presence of younger children leads to less voluntary participation. Caring for children demands time allocation that cannot be devoted to other activities.

Being employed decreased participation in cultural volunteering. This is reasonable, as working diminishes the time available for leisure activities (Becker, Reference Becker1965). Though the relationship between employment and sports volunteering was also negative, it was not significant. This could partly be related to the predominance of males in sports volunteering. Even if employment is a time constraint, men may have more available time if childcare continues to be primarily a female responsibility. The absolute value of the marginal effect of younger children was more than double for those who “only volunteer in culture” compared to those who “only volunteer in sport.” Education and income also positively influenced volunteering, confirming previous findings (Eimhjellen et al., Reference Eimhjellen, Steen-Johnsen, Folkestad, Ødegård, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018). While theoretically there was ambiguity about these assumptions, in terms of income our findings suggested that the ‘income effect’ dominates the ‘substitution effect’ and outweighs the opportunity cost of working longer hours.

Living in a rural location contributes to volunteering, but only in the case of sport. This is also an a priori expected finding (Balish et al., Reference Balish, Rainham and Blanchard2018), as smaller communities facilitate social interactions and contribute to social capital accruement (Chalip, Reference Chalip2006). In urban areas, life is more anonymous. There is less sense of belonging to the community than in smaller locations. Consequently, though cities presumably have more sports facilities and nonprofit bodies, volunteering was more prevalent in small communities.

The results suggested that individuals whose parents have been engaged in volunteering are more likely to volunteer, which confirmed the crucial role of parents. This is supported previous research regarding sports and cultural participation (Coleman et al., Reference Coleman, Cox and Roker2008; van Hek & Kraaykamp, Reference van Hek and Kraaykamp2015). Therefore, intergenerational transmission of interest in volunteering is central to guarantee volunteering in the future. Our results also confirmed that belonging to a religious group enhanced volunteering in sport and cultural activities. The majority of religions involve a range of moral responsibilities that imply behaviors aimed at helping underprivileged groups. Therefore, faith-based individuals would be more likely to volunteer to manifest their commitment toward the most vulnerable (Prouteau & Sardinha, Reference Prouteau and Sardinha2015).

Implications

While organizations traditionally competed to attract and retain volunteers, the simultaneous estimation of the decision to volunteer in sport and culture suggested that different volunteering patterns are positively associated. Therefore, the two forms of volunteering are simultaneously determined and mutually reinforcing. Thereby, the relevance of our research is emphasized as a holistic approach from several fields that brings valuable insights into the promotion of volunteering. This is a major theoretical contribution to the field. This study provided evidence for employing the behavioral economic approach to the decision to volunteer or not volunteer. The time allocation model informed it. However, this study’s theoretical framework went beyond a neoclassical approach to decision-making. It integrated additional socio-demographic, environmental, and sociocultural variables (see Fig. 1). Thereby, a behavioral approach to decision-making was confirmed, similarly to in previous studies (e.g., Burgham & Downward, Reference Burgham and Downward2005; Hallmann et al., Reference Hallmann, Downward and Dickson2018; Wicker & Hallmann, Reference Wicker and Hallmann2013).

Volunteering is recognized as a primarily social activity (Toraldo et al., Reference Toraldo, Contu and Mangia2016). While there have been shifts toward more tailored volunteering reflecting individual interests and lifestyles, such as culture or sport, networking remains central (Wang & Graddy, Reference Wang and Graddy2008) as culture and sport are social activities. The opportunity to gain social capital through volunteering in sport or culture emphasizes the complementary relationship between the two areas of volunteering. Managers of nonprofit organizations could profit from these insights.

The marginal effects demonstrated that education and religion are leading sports and cultural volunteering drivers. These factors lead to individuals becoming more sensitive to their civic obligations and the importance of helping others. It is a challenge as religiosity and the educational system have a declining influence on the “teaching” of civic obligations (Son & Wilson, Reference Son and Wilson2012). Moreover, in an increasingly individualistic society, responsibility is understood as individual rather than collective action. However, social responsibility can also emerge inside the family, as the positive effect of parental volunteering demonstrated. Thus, religiosity and education promoted volunteering, but parents can also encourage children’s civic behavior (Nesbit, Reference Nesbit2013). This resonates with the governmental perception that volunteering fosters social relationships and enriches society (BMI, 2021a). However, social integration is not (yet) fostered and individuals with a migration background were less likely to volunteer. These factors can foster generosity, trust, and solidarity and contribute to volunteering (Wang & Graddy, Reference Wang and Graddy2008). Policymakers should promote socialization as a responsibility toward others. As sports and culture are male and female-dominated, respectively, gender diversity inside the institutions should be promoted to contribute to societal outcomes (Nowy & Breuer, Reference Nowy and Breuer2019).

Congruent with previous findings on sports and cultural activities participation, educational and monetary constraints on volunteering in both settings have been identified. Accordingly, it is essential to prevent the social exclusion of vulnerable groups in sports and culture (Hallmann et al., Reference Hallmann, Artime, Breuer, Dallmeyer and Metz2017; Husu & Kumpulainen, Reference Husu and Kumpulainen2020). It is especially relevant in “high culture” where subsidies are granted to a sector in which the elite is predominant. Thus, further actions should be launched as cultural policy traditionally involves a redistribution of resources to the most privileged (Miles & Sullivan, Reference Miles and Sullivan2012).

Limitations and Future Research

One limitation of this study relates to secondary data. We were bound to use the existing variables for the survey. However, the benefit of using secondary data is that the sample size is an asset representing the whole German population. Another limitation refers to the variables and their scale. Most variables were binary and not metric. We utilized binary variables (e.g., income) so that we were able to understand multiple ranges (here income levels) and their relationship with sports and cultural volunteering.

Another limitation is that this study used cross-sectional data, which does not allow evaluating longitudinal effects or for controlling for unobserved individual heterogeneity. Therefore, adding panel data to the study is a fruitful approach for future studies. Finally, although a positive association between sport and cultural volunteering is found, it would be interesting to explore other domains. It would be relevant to ascertain if this complementarity relationship exists in other volunteering domains. Moreover, this study looks at decision-making in terms of being involved in volunteering or not. A future line of research might explore the number of hours devoted to volunteering in each activity. Then, similarities and differences between participation in and frequency for volunteering choices could be identified.

Conclusion

The simultaneous estimation of the decision-making on volunteering in sport and cultural activities suggested a highly significant positive correlation. This result revealed that the two contexts are linked. Promoting volunteering in one of the domains, for example, culture, positively affected volunteering in sport and vice versa.

Considering the significance and the sign of the coefficients, most of the hypotheses previously drawn are valid regarding the impact of the explanatory variables on volunteering behavior, particularly in sport. Parental volunteering, religiosity, and education were positively correlated with both types of volunteering. However, differences in some determinants have also been found. Volunteering in culture was predominantly female, while male, young volunteers who live in multi-person households dominated sports. Working acts as a deterrent to volunteering but only concerning culture. This, linked to female-dominated cultural volunteering, could suggest further time pressures on female volunteers. Volunteering in sport and culture contributed to participation in these activities (Dawson & Downward, Reference Dawson and Downward2013; Orr, Reference Orr2006). Thus, promoting volunteering will be central to developing the array of social impacts that emerge from sports and culture.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.