Introduction

The prevalence of semi-presidential regimes has increased from a few European cases in the 1920s (France and the Weimar Republic) to a multitude of examples worldwide. With an increasing number of cases, the research on semi-presidential regimes has expanded the many new semi-presidential regimes in a post-colonial or post-communist context that enabled studies of institutional effects on, first and foremost, the challenges of democratisation. One driving condition for this expansion of studies has been the comparative databases providing data on semi-presidential regimes for various research designs. However, discrepancies in conceptualization and the lack of updates and transparent coding present a challenge for future studies about semi-presidential regimes. Therefore, we introduce the Comparative Semi-Presidential Database (CSPD) in this article.

The CSPD identifies semi-presidential regimes among all independent states from 1900 to 2021. Our database offers four advantages over existing databases on semi-presidential regimes. First, the database identifies semi-presidential regimes along with the two subtypes (premier–presidential and president–parliamentary regimes) commonly used in empirical analyses. Second, inspired by the multi-conceptual approach of Coppedge et al. (Reference Coppedge2020), the CSPD offers classifications based on alternative concepts due to the ongoing debate on the definition of semi-presidentialism. Third, the CSPD’s classifications are made with transparent rules for coding and aggregation, allowing for the control and application alongside other sources. Fourth, we have designed the database to enable regular and less time-consuming updates. The latter is a critical factor for future studies as some of the existing databases are not regularly updated.

The article is organised into six sections. The following section presents an overview of the existing databases, including their advantages and limitations. The third section focuses on definitions of semi-presidentialism and the debates resulting in the database's conceptual schema. In the fourth section, we demonstrate how we have measured this conceptual schema along with the database structure. In the fifth section, we present descriptive analyses of the database that illustrate the development of semi-presidential regimes and compare them with the alternative concepts and databases. In the final section, we discuss future work with the database.

Existing databases

For comparative research on semi-presidential regimes, there are three available datasets with global reach. First, Elgie (2018) developed a dataset based on his own definition of semi-presidentialism (Elgie Reference Elgie and Elgie1999) as a popularly elected president with a fixed-term president that exists alongside a prime minister and cabinet responsible to parliament.Footnote 1 As this definition has become seminal in the field, the database has significantly shaped research on semi-presidentialism. The database identifies semi-presidential regimes from 1900 to 2016 but suffers from two limitations. First, the database has not been systematically updated since 2016, which makes it less relevant over time. Second, its coding and aggregation principles are not completely transparent, making controls and updates difficult for external projects.

Second, the extended version of Democracy and Dictatorship (Cheibub et al. Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010) offers a classification of political regimes that includes semi-presidential regimes (‘mixed regimes’). The classification covers all independent states from 1945 to 2007. The definition used is similar to Elgie’s. Both include the criteria of an elected president and the opportunity for the parliament to dismiss the cabinet, but Cheibub et al. (Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010) add democracy as a criterion. Although the principles for coding and aggregation are more transparent for Democracy and Dictatorship than for the Elgie database, this database has not been updated since 2007.

Third, Anckar and Fredriksson (Reference Anckar and Fredriksson2019) have developed a regularly updated database on political regimes built on transparent principles of coding and aggregation that covers independent states from 1800 or the year of independence. The database classifies political regimes into subcategories, including semi-presidential regimes. The criteria of Anckar and Fredriksson differ from those of the previous datasets. First, they regard semi-presidential regimes as democratic regimes and exclude the criterion of a popularly elected president. Instead, they require that executive power be shared by the prime minister and the head of state, which means at least one of the following criteria: The president (a) has the power to chair cabinet meetings, (b) is in charge of foreign policy, (c) has a central role in government formation (and/or dissolution) or (d) has the ability to dissolve the legislature at will. However, their concept of semi-presidential is different from the conventional definition in the field, which emphasises a popularly elected president with a fixed term and does not always have democracy as a criterion. Anckar and Fredriksson are aware of these differences and offer a possibility within the dataset to add an elected president as a component.

These three databases have enabled comparative research and studies on semi-presidential regimes. However, they suffer from shortcomings such as lack of updating, unclear principles for coding and aggregation, limited case coverage and unconventional definitions. Additionally, all three databases work with only one definition, which either prevents studies with other definitions from using the database or forces them to make conceptual adjustments due to access to data.

Semi-presidentialism as a political category

Duverger (Reference Duverger1980) developed a definition that provided the conceptual foundation for early studies on semi-presidential regimes. According to this definition, semi-presidential regimes have a president with considerable powers who is elected by universal suffrage. Opposite the president is a cabinet with a prime minister with executive power who can stay in office only if the parliament does not oppose them.Footnote 2 Duverger’s definition dominated studies for over a decade. However, in the 1990s, the conceptual debate intensified as the number of semi-presidential countries increased. One scholar who criticised the definition was Sartori (Reference Sartori1994), who developed his own definition. According to Sartori, semi-presidential regimes have a dual authority structure in which the cabinet and prime minister are independent of the president but subject to parliamentary confidence. The president is popularly elected for a fixed term, is independent of the parliament but cannot govern independently of the government and shares executive power with the prime minister. This duality allows for shifts in the balance of power within the regime. Sartori’s definition has, together with his definitions of parliamentary and presidential regimes, received attention in comparative studies and contributed to conceptual debates on semi-presidential regimes.

Another critique came from Elgie (Reference Elgie and Elgie1999). Elgie argued that the component of considerable presidential power introduced an element of subjective judgement into empirical analyses. Therefore, he formulated a similar definition that excluded the aspect of presidential power. According to his definition, semi-presidential regimes have a popularly elected president with a fixed term who exists alongside a prime minister and cabinet responsible to parliament. The definition has only two components and a less complex structure than the definitions of Duverger and Sartori. It became seminal for theoretical works and empirical studies of semi-presidential regimes.

Later, Cheibub et al. (Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010) revised Elgie’s definition to develop their database on political regimes. They define semi-presidential (or mixed) regimes as a democratic government system where the head of state is elected for a fixed term in office, and the cabinet is accountable to a parliament able to remove the cabinet from office. Compared to Elgie’s dataset, Cheibub et al. follow Elgie in excluding the component of presidential powers but add a component of democracy specifying that the cabinet’s parliamentary dependence includes the ability of the parliament to remove the cabinet from office. Shugart and Carey (Reference Shugart and Carey1992) focused on the lines of representation and accountability among the key actors: The president, the cabinet and the parliament. They emphasised the differences between semi-presidential systems and the identified two subtypes: The premier–presidential system and the president–parliamentary system. In a premier–presidential regime, the president is elected by a popular vote for a fixed term in office; the president selects the prime minister, who heads the cabinet; and the parliament has the exclusive authority to dismiss the cabinet. In a president–parliamentary system, the president is elected by a popular vote for a fixed term in office; the president appoints and dismisses cabinet ministers; and the prime minister and cabinet ministers are also subject to parliamentary confidence (Shugart Reference Shugart2005; Shugart and Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992). The critical differentiator between these two subtypes is whether the president has the discretion to dismiss a prime minister/cabinet. In their refined definition, Shugart and Carey captured aspects of presidential powers in relation to the dual authority structure of semi-presidential regimes, similar to both Sartori (Reference Sartori1994) and Anckar and Fredriksson (Reference Anckar and Fredriksson2019).

Although Elgie’s definition became standard in the field, scholars have criticised the exclusion of presidential powers as well as the strong focus on a popularly elected president. For example, according to Elgie’s definition, semi-presidential regimes include systems with presidents who, while elected, have only symbolic functions and minimal presidential power (Anckar and Fredriksson Reference Anckar and Fredriksson2019; Siaroff Reference Siaroff2003).Footnote 3 The critique targets both the reasoning behind including figurehead presidents and the fact that the definition blurs the distinction between parliamentary and semi-presidential systems. As previously mentioned, Anckar and Fredriksson (Reference Anckar and Fredriksson2019) define a semi-presidential regime as a system in which prime minister and president share executive power in a way that meets at least one of the following criteria: the president (a) has the power to chair cabinet meetings, (b) is in charge of foreign policy, (c) has a central role in government formation and/or dissolution or (d) has the ability to dissolve the legislature at will. This definition does not stipulate that a popularly elected president is essential for the semi-presidential regime; instead, presidential power is. They argue that classifications that focus on the presidential elections, blur “the distinction between parliamentary and semi-presidential systems” because otherwise, the difference between the two “boils down to how a (powerless) head of state is selected” (Anckar and Fredriksson Reference Anckar and Fredriksson2019: 89). We agree that the distinction between parliamentary and semi-presidential regimes should not exclusively rest upon the election of the president, but instead of removing the election of the president as a criterion, we address the dilemma by adding a component already present in Shugart’s (Reference Shugart2005) definition of the premier-presidential and president–parliamentary subtypes, namely that the president can appoint the prime minister or cabinet. We argue that a popularly elected president with such appointment capacity is substantially more than a mere figurehead. Even if the president’s appointment follows the results of parliamentary elections, the powers of appointments may make the president a more influential actor than if not having those powers.

Another difference between the definition of Elgie (Reference Elgie and Elgie1999) and the later alternatives is the specification of semi-presidential regimes as democratic government systems. In their classifications, Cheibub et al. (Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010) and Anckar and Fredriksson (Reference Anckar and Fredriksson2019) explicitly designated semi-presidential regimes as democratic subtypes. While Shugart and Carey were more implicit about the democracy component, Shugart (Reference Shugart2005) defines the character of semi-presidentialism as separate from that of parliamentary and presidential democracy. Parliamentary democracy fuses the origin and survival of the government with the parliament as “the government survives in office only so long as it does not lose the ‘confidence’ of the majority” (Shugart Reference Shugart2005, p. 325) while presidential democracy separates the origin and survival of legislature and executive. For the semi-presidential regime, the key feature of definitional meaning is the duality of the executive, that the president’s origin and survival are separate from the legislature while the government “has its survival fused with the assembly majority” (Shugart Reference Shugart2005, p. 327). In that, the characteristic feature of semi-presidentialism rests upon the existence of a parliament whose majority has, at least a potential, say for the survival of the government. In an authoritarian regime fully concentrating powers on the president, the constitutional ability of the parliament to influence the cabinet has lost its meaning and also its semi-presidential character. Such regimes can be semi-presidential in its executive and legislative institutional setup but not in any real duality of the executive–legislative institutions. As Stykow (Reference Stykow2019) later noted studies that exclude the criteria of democracy risk overstretching the concept of semi-presidentialism, reducing its analytical meaning and precision and increasing the risk of including non-relevant cases. Therefore, our dataset regards semi-presidential regimes as democratic regimes but offers the possibility of viewing them as formal arrangements with assumed relationships between institutions.

In sum, a definition of a semi-presidential regime should consider the dual authority structure between the president and parliament, which requires the specification of presidential power and the inclusion of a democratic component. Furthermore, the definition should include the premier–presidential system and the president–parliamentary system as subtypes. With this foundation, we developed a modified concept of semi-presidentialism as the basic category for the database. We define semi-presidential regimes as a democratic government system with (a) a popularly elected president with a fixed term who (b) has the power to appoint the prime minister or the government as a whole and (c) exists alongside a prime minister and cabinet who are accountable to parliament and d) a parliament that either exclusively or, along with the president, has the authority to dismiss the cabinet. In premier–presidential systems, the parliament has the exclusive authority to dismiss the cabinet. In contrast, both the parliament and the president of the president–parliamentary system have the authority to dismiss the cabinet.

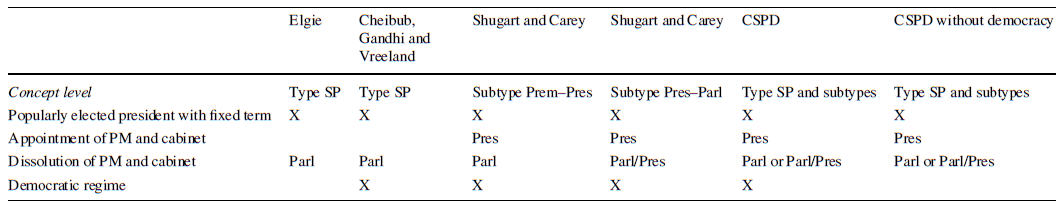

In addition, as there is still no scholarly consensus on the definitional components, the database holds a multi-conceptual approach. This approach means that the database centres on our operationalized definition but also includes categories derived from alternative definitions as a service to different groups of scholars. Including other definitions is both a service to scholars of the semi-presidential field as well as to scholars in the larger comparative field. Ultimately, this approach facilitates the comparison of classifications based on different definitions and may serve to settle disputes between them through future studies. As the definition by Elgie (Reference Elgie and Elgie1999) has become conventional in the field, just as the definition of Cheibub et al. (Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010) is frequently used in the field of comparative studies, we have included these two alternative categories according to their definitions. As our definition is built on the work of Shugart and Carey, the main category provides opportunities to identify the two subtypes (Shugart Reference Shugart2005; Shugart and Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992). The definition by Anckar and Fredriksson (Reference Anckar and Fredriksson2019) is not used in the database as it is updated frequently, but we include their classification of cases. In addition, we are aware of the fact that many scholars in the field of semi-presidentialism treat semi-presidential regimes irrespective of the democratic component. We, therefore, offer operationalisations disregarding the democracy criterion. Again, our intention is twofold, to offer updated versions of the common definitions of semi-presidentialism and to offer an operationalization that resolves two of the common controversies of the current definition; how to make sure that semi-presidentialism is not blurred with parliamentarism and that there is not a discrepancy between the general container of semi-presidentialism and the commonly used subtypes of semi-presidentialism. Table 1 summarises the included definitions and highlights the similarities and differences between them.

Table 1 Definitions included in CSPD

SP, semi-presidential regime; Prem–Pres, premier–presidential system; Pres–Parl, president–parliamentary system; Pres, President; Parl, Parliament; Parl/Pres, both parliament and president have the opportunities

Structure of database: measurement and materials

Figure 1 presents a framework for systematically identifying semi-presidential regimes (and their subtypes) in five steps according to our definition. A critical aspect of both the definition and the framework is that the parts are related with conjunctions (‘and’) to identify semi-presidential regimes and distinguish its subtypes as the last step. This logical structure results in two categories of semi-presidential regimes, one for each subtype. As there are institutional variations between the two subtypes, the separation allows researchers to test if the subtypes have different determinants and consequences, but also identify shifts between them. Together, these two categories identify the core category of semi-presidential regimes. Additionally, the structure enables the identification of semi-presidential regimes according to other definitions. For example, researchers who disagree on the necessity of democracy can ignore the first step and start with the second step.

Fig. 1 Steps for classification of semi-presidential regimes

The database uses material from two databases to identify semi-presidential regimes with the framework: The Comparative Constitutional Project (CCP) and Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem). CCP is a database project that codes characteristics of national constitutions since 1789. We used version 4.0 of the database, including all independent states to 2021 and data for 14,299 country–year observations (Elkins and Ginsburg 2022). The V-Dem database offers data on democracy and political institutions. The structure is multidimensional and disaggregated to reflect the complexity of concepts. The database covers the years from 1789 and provides country–year observations for more than 600 variables. We used version 13, which covers the years up to 2022 (Coppedge et al. 2023).

The rationale for our use of these databases is manifold. The databases are internationally recognised and used in comparative studies. Both databases have transparent coding and aggregation principles that closely follow the conceptualisation. Additionally, the comparability of temporal and spatial aspects is high, which is critical for constructing new comparative variables. Finally, the databases have extensive coverage of countries and years, as the teams behind the databases both update the databases frequently and work with historical data.

Most variables in our database come from CCP and concern constitutional attributes that are relevant according to the definition: an elected president with a fixed term, parliamentary dissolution of prime minister/cabinet and presidential dissolution of prime minister/cabinet ministers.Footnote 4 However, two components in our definition require using variables from V-Dem. First, there are variables about democracy in the CCP database, but these variables indicate whether constitutions refer to democracy and how many times they do so. To obtain a more reliable and valid definition, we have used the variable Regimes of the World from V-Dem. This variable classifies political regimes into four categories: closed autocracy, electoral autocracy, electoral democracy and liberal democracy. The minimal conditions of democracy, according to the modified definition of semi-presidentialism, correspond to the category of electoral democracy; meaning de facto, free and fair elections with competition between several parties and institutional prerequisites for polyarchy.Footnote 5 We have, therefore, categorised electoral democracy and liberal democracy as democratic regimes while we consider closed autocracy and electoral autocracy as autocratic regimes. Second, we also capture whether the head of state (i.e. the president) appoints the head of government (i.e. the prime minister) in practice based on the V-Dem dataset. While the appointment power of the president is central for semi-presidential regimes, it is not included in the CCP dataset.

The codebook of the database presents a more detailed description of how we used information from the two databases to identify semi-presidential regimes according to the definition (see Supplementary file 1). The unit of analysis in the database is country–year observations. To identify independent countries, we relied on information offered by Gleditsch and Ward (Reference Gleditsch and Ward1999; 2021), which CCP and V-Dem also use with minor modifications.

A first glance at the database

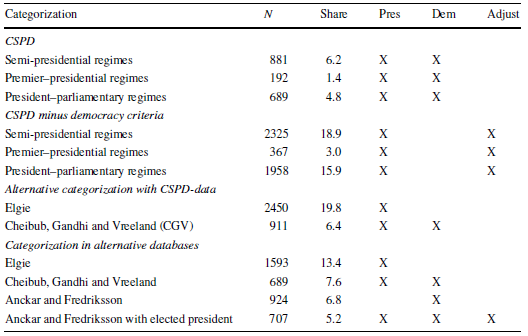

The database consists of 14,280 country–year observations covering 201 independent states from 1900 to 2021. With the framework of Fig. 1, the classification identifies 881 cases of semi-presidential regimes (6.2 per cent). As seen in Table 2, if we exclude the criteria of electoral democracy, the numbers increase to 2325 cases (18.9 per cent). The increase illustrates the significance of the democracy criteria. Furthermore, the database offers opportunities to identify cases of the semi-presidential subtypes. There are 192 cases of premier–presidential regimes (1.4 per cent) and 689 cases of president–parliamentary regimes (4.8 per cent). When we use the categorisation that excludes the democracy criteria, the number of subtype cases increases to 367 (3.0 per cent) and 1958 (15.9 per cent). The sharp rise of president–parliamentary regimes without the democracy criterion illuminates the difference in the distribution of the subtypes as part of democratic and autocratic regimes. There are 1444 cases of semi-presidential institutions (12.7 per cent), 175 observations of premier–presidential institutions (1.6 per cent) and 1269 cases of president–parliamentary institutions (11.1 per cent) in autocratic countries.

Table 2 Classifications of semi-presidential regimes

N=number of semi-presidential cases; Share=per cent of semi-presidential cases of all cases; Pres=elected president as criteria; Dem=Democratic regime as criteria; Adjust=definition and classification adjusted from original

Additionally, the database includes categorisations of country database along two alternative definitions. First, we have categorised countries according to Elgie’s definition (1999). This categorisation identifies 2450 cases of semi-presidential regimes (19.8 per cent). Second, we have used the definition offered by Cheibub et al. (CGV) for categorisation. According to this categorisation, there are 911 cases of semi-presidential regimes (6.4 per cent). Considering total numbers and shares, our classification is the most restrictive but close to the CGV classification. The categorisation based on Elgie is the most extensive. However, the CSPD minus the democracy criterion (CSPD II) also results in a relatively high number of shared country cases.

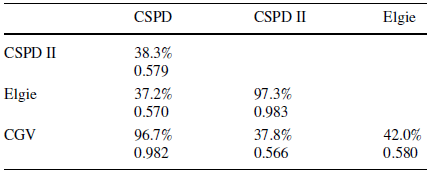

To further compare the categorisations in the database, we conducted pairwise calculations on the overlapping of semi-presidential cases and the correlation between categorisations. Table 3 presents the outcomes of these analyses. Less than 40 per cent of CSPD’s cases overlap those of CSPD II and Elgie, while the overlapping share with CGV is almost 97 per cent. For example, for the year 2016, Austria is not termed semi-presidential due to its lack of a fixed term for the president that may be deposed by a popular referendum, and neither is Ireland where the president’s capacity to nominate a prime minister or cabinet is too restricted by either the lower chamber or by the prime minister. When the democratic criteria are left out (CSPD II), the overlapping shares with Elgie and CGV become the reverse, with the share of overlapping between CSPD II and Elgie higher than between CPSD II and CGV. Finally, the classifications based on Elgie and CGV have 42 per cent overlapping cases of semi-presidential cases. From these comparisons, it becomes clear that the democracy criteria play a critical role in the similarities between the classifications. Classifications that use the criteria have a high share of overlapping cases (CSPD and CGV), while classifications that do not use the criteria have a high share (CSPD II and Elgie) but a lower share of overlapping cases with the democratic-based classifications.

Table 3 Comparison between categorizations in the CSPD

Share of overlapping cases as semi-presidential regimes and correlation coefficient (tau-b). All coefficients are significant (<0.001). N=12,272 for all cells. CPSD II is CPSD without the democracy criteria

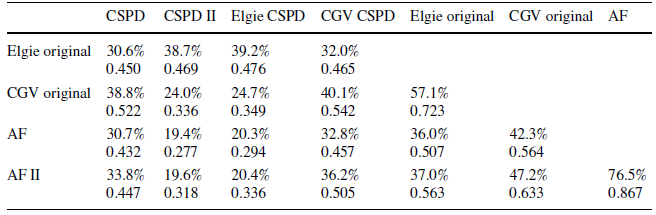

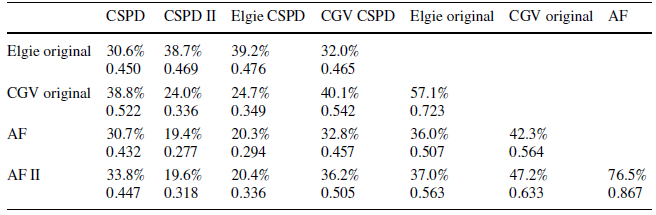

Comparing classifications from different datasets is challenging for several reasons. For example, there are differences in their cases and years, materials, measurements and missing cases. Nevertheless, Table 4 presents share of overlapping cases and correlations between alternative databases. First, the share of overlapping cases is around one-third between the CSPD and alternative databases. The highest percentage is with CGV, but it is still under 40 per cent. Second, CSPD II has more diverse shares of overlapping. The lowest share of overlap is below 20 per cent (with Anckar and Fredriksson [AF] and AF II), while the highest is 38 per cent (with Elgie). Third, the two classifications in the CSPD that are based on definitions that guide alternative databases (Elgie CSPD and CGV CSPD) have only around 40 per cent of overlapping cases with these databases. Fourth, Table 4 also indicates noteworthy differences between existing classifications. The classifications provided by AF have fewer overlapping cases with the two other databases, but the differences between Elgie CSPD and CGV CSPD are also considerable.

Table 4 Comparison between CSPD and alternative databases

Share of overlapping cases as semi-presidential regimes and correlation coefficient (tau-b). All coefficients are significant (<0.001). N=13,665 − 7642

AF, Anckar and Fredriksson; AF II, Anckar and Fredriksson with elected president

The conclusion that can be drawn from the comparisons is that the CSPD presents an updated and new classification of semi-presidential regimes that distinguishes it from alternative databases. The number of identified regimes is lower than in alternative databases (Table 3), while there are differences between alternative classifications as well. The share of overlapping cases, as well as the correlations, is relatively low (Table 4). These differences are not surprising, as the databases and their classifications have different conceptualisations and measurements. In particular, there are considerable differences between conceptualisations that include and exclude the democracy component. At the same time, the comparisons between different conceptualisations of semi-presidentialism highlight how critical the matter of definition and operationalisation is for empirical studies. Given that the selection may affect results and conclusions, there is a rationale for conducting robustness tests to explore the effect of selected classifications, regardless of the variables employed in descriptive or explanatory analyses (Neumayer and Plümper Reference Neumayer and Plümper2017).

Conclusion

The semi-presidential regime has become an alternative to the parliamentary and presidential regime and, as such, an object of conceptual debate and empirical studies. A challenge for comparative studies of semi-presidential regimes is access to updated data that reflects the conceptual development of the field. This article introduces the CSPD, which offers updated data on semi-presidential regimes and subtypes. We have constructed the database to reflect conceptual developments by introducing a modified definition of semi-presidential regimes. Additionally, we offer classifications on both type (semi-presidentialism) and subtype (premier–presidential or president–parliamentary) levels. Moreover, the database includes classifications based on other definitions, including those seminal in the field. This multi-conceptual approach allows for the comparison of definitions and selection of categorisations based on the different conceptualisations of semi-presidentialism.

The database offers considerable promise in answering both new and old research questions. For example, our dataset can be used to describe developments and explore determinates and consequences of semi-presidential regimes, as well as to compare subtypes and conduct robustness tests with different definitions. As such, we hope that the CPSD will prove useful to future research endeavours.

However, we recognise that our database is not perfect or final. Although studies will use the CSPD for future research about semi-presidential regimes, we emphasise the need for further work. For example, the database uses material collected from databases that do not have a specific focus on semi-presidential regimes. An avenue for further development would involve refining the process of material collection and coding with a specific focus on semi-presidential regimes. Also worth considering is offering classifications according to different levels as well as different definitions. For good reason, the database currently offers classification on the formal level (de jure). We do not argue that only formal rules matter, but that formal rules matter, while often, in turn, affected by the influence of contextual variables. For example, Moestrup and Sedelius (2023) trace the combined effects of formal and contextual factors for explaining presidential activism in Cabo Verde and São Tomé e Principe. In that, our updated dataset enables future studies to trace the effects of formal powers as well as their effects combined with informal powers or contextual conditions. A final suggestion for future studies is the development of a new typology that incorporates the categories of semi-presidential regimes with categories of other government regimes. Such work could result in the revisions of existing categories or the development of new categories.

The article presents the conceptual and methodological contributions of the new database, but the empirical analyses also provide a critical contribution to future research. The analyses show considerable differences between classifications offered by existing databases. In many cases, the share of overlapping cases is low, with weak correlations between classifications. Studies must consider these differences in their choice of database as they may affect empirical results. A recommendation for future studies is to conduct robustness tests with alternative classifications to specify the effects of the choice of classification on results, which the CSPD allows researchers to do more easily than before.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-024-00499-0.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Örebro University.

Data availability

The dataset and updated versions of it will be available in Harvard Dataverse https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NPI32D.