Introduction

A crucial aspect of modern democracy concerns the degree to which different political elites – such as top bureaucrats, politicians and interest group leaders – share similar career experiences and shift across different elite positions. When the Danish Minister for Business leapt to a position as chief executive officer (CEO) of the Chamber of Commerce in 2018, it attracted widespread attention and many criticized that he moved directly into a lobbying organization working within the jurisdiction of the former ministry (Bruun, Reference Bruun2018). There are similar examples of remarkable elite transfers from other European parliamentary systems. Stefan Löfven chaired the metal workers’ union before becoming the prime minister of Sweden. Franz Walter Steinmeier, the President of Germany, began his career as a civil servant, then served as a political adviser to the chancellor, only to become a state secretary and, later, federal minister. In the United Kingdom, former transport secretary Patrick McLoughlin was appointed chairman of Airlines UK in 2021. Examples like these raise concerns that elected politicians may serve the interests of possible future employers rather than voters (Egerod, Reference Egerod2022; Shepherd & You, Reference Shepherd and You2020) and that some lobby groups may gain unfair advantages by recruiting from other elite sectors (Blanes i Vidal et al., Reference Blanes i Vidal, Draca and Fons‐Rosen2012), and that the political elite constitutes an exclusive inter‐connected group of people (Mills, Reference Mills1956). Still, this is anecdotal evidence as we lack systematic analyses of intersectoral mobility and career similarity within the political elites of parliamentary systems.

The questions of elite similarity and interconnectedness are central to classic and present‐day studies of political elites (Best & Higley, Reference Best, Higley, Best and Higley2018; Dahl, Reference Dahl1958; Mills, Reference Mills1956; Pareto, Reference Pareto1901/1968). Elite scholars have focused both on the initial attainment of elite positions and the degree of openness in recruitment patterns and on the connections between elites and mobility across different positions (Christiansen & Togeby, Reference Christiansen and Togeby2007; Ellersgaard et al., Reference Ellersgaard, Lunding, Henriksen and Larsen2019; Mills, Reference Mills1956; Ruostetsaari, Reference Ruostetsaari2021). A significant ‘revolving door’ literature describes how widespread transfers between elite positions are. Most of these studies focus on a single elite group and investigate where they go when they leave their elite positions (Askim et al., Reference Askim, Karlsen and Kolltveit2020; Baturo & Arlow, Reference Baturo and Arlow2018; Blach‐Ørsten et al., Reference Blach‐Ørsten, Willig and Pedersen2017; Byrne & Theakston, Reference Byrne and Theakston2015; Claessen et al. Reference Claessen, Bailer and Turner‐Zwinkels2021; Claveria & Verge, Reference Claveria and Verge2015; Dörrenbächer, Reference Dörrenbächer2016, Hjelmar et al., Reference Hjelmar, Pedersen and Pedersen2021; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Buhmann‐Holmes and Egerod2021).

We aim to contribute to this important literature by studying career similarity and elite transfers within and across different parts of the political elite. Specifically, we ask the following question: To what extent do parliamentary, bureaucratic and interest group elites have similar or distinct career trajectories – and to what extent are they recruited from elite positions in other sectors? In other words, how many ‘revolvers’ – such as the prominent examples mentioned above – are found in the political elite at a given time, and how similar are the career paths of elite individuals across and within political elite groups? By including different elite groups, we are able to provide a more encompassing analysis than the previous literature and to identify whether some types of shifts between elite positions are more common than others.

We define the political elite as individuals capable of affecting societal outcomes because of their possession of top leadership positions in influential organizations (Ruostetsaari, Reference Ruostetsaari2021, p. 2) and operationalize this as politicians elected for office in national legislatures, bureaucrats holding top positions in the central administration and leaders of interest groups that are privileged in the political decision‐making process. We argue that because of varying recruitment criteria and reputational cargo, career trajectories are sector dependent and the presence of revolvers moving between elite positions across political sectors is consequently limited. We use the concept of reputational cargo to describe how the reputation of elite members acquired mainly through the possession of elected elite positions may affect the level of transfers across elite sectors. Elite sectors with strict recruitment criteria and low appreciation of reputational cargo will be relatively close to transfers from other elite sectors. However, elite individuals from within such sectors will be better equipped to transfer into other elite sectors, where their acquired reputation can be turned into a career asset.

We investigate the plausibility of our argument using unique data on the yearly post‐educational employment of 574 individuals who held an elite position in Denmark in 2018. We identify these individuals using the positional approach by which the elite is defined by their possession of formally powerful positions in society (Hoffmann‐Lange, Reference Hoffmann‐Lange, Best and Higley2018; Ruostetsaari, Reference Ruostetsaari2021, p. 2). We focus on two elite groups central to formal political power, politicians and bureaucrats and two groups central to civil society, elected interest group chairs and appointed interest groups CEOs. We investigate (1) how similar the career trajectories of these elite individuals are and (2) how many of them have previously held elite positions in other elite sectors. We add to the existing literature on political elites by including four distinct elite groups and by combining detailed mappings of elite career trajectories with analyses of intersectoral elite recruitment (Christiansen & Togeby, Reference Christiansen and Togeby2007; Ellersgaard et al., Reference Ellersgaard, Lunding, Henriksen and Larsen2019; Ruostetsaari, Reference Ruostetsaari2021).

Our analyses of career trajectories find relatively distinct career paths of elite individuals in the different sectors. In particular, individuals occupying a top position in the administration follow a narrow administrative career trajectory, and they seldom come from an elite position in a different sector. While the analysis does not provide a formal test of our arguments, the identified patterns suggest that there are important limitations to elite transfers, dampening the concern of inter‐elite exclusiveness highlighted in the literature so far. Moreover, our findings suggest that while the remarkable examples of elite revolvers are conspicuous, they are not very representative for the Danish case. In fact, only 4 per cent of the elite actors are revolvers in the sense that they have previously occupied an elite position in one of the other sectors. However, these few individual cases may be of significant political importance.

How recruitment criteria and reputational cargo shape elite career track similarity and transfer

The issue of elite interconnectedness plays a prominent role in classic as well as modern elite theory and research. Scholars such as Reference ParetoPareto (1901/1968) and Mills (Reference Mills1956) were concerned with the degree of openness in elite recruitment and the level of circulation across different elite positions, which is crucial for democratic plurality (Dahl, Reference Dahl1989; Higley, Reference Higley, Best and Higley2018; Higley & Moore, Reference Higley and Moore1981; Mills, Reference Mills1956).

Two conflicting perspectives on elite interconnectedness are advanced in the literature. First, a number of studies have pointed to increasing similarity in elite recruitment and transfers across elite positions. Across modern democracies, politics has become more professionalized with a stronger emphasis on professional political communication and academic credentials marketable across elite sectors (Blach‐Ørsten et al., Reference Blach‐Ørsten, Willig and Pedersen2017; Bovens & Wille, Reference Bovens and Wille2017 Gulbrandsen, Reference Gulbrandsen2017, pp. 170−171;). The revolving door literature builds on this idea, and several studies find that transfers from one elite position to another are common (Askim et al., Reference Askim, Karlsen and Kolltveit2020, Reference Askim, Bach and Christensen2022; Baturo & Arlow, Reference Baturo and Arlow2018; Byrne & Theakston, Reference Byrne and Theakston2015; Claessen et al., Reference Claessen, Bailer and Turner‐Zwinkels2021; Claveria & Verge, Reference Claveria and Verge2015; Dörrenbächer, Reference Dörrenbächer2016; Egerod, Reference Egerod2022; Eggers & Hainmueller, Reference Eggers and Hainmueller2009; Lazarus et al., Reference Lazarus, McKay and Herbel2016).

Second, other studies paint a more sobering picture of elite circulation in modern democracies. Theoretically, scholars emphasize how recruitment to elite positions in different sectors is shaped by different dynamics and how barriers to recruitment may limit the options for passing through the revolving door (Coen & Vannoni, Reference Coen and Vannoni2016; Hjelmar et al., Reference Hjelmar, Pedersen and Pedersen2021; Ruostetsaari, Reference Ruostetsaari2021). Empirically, studies of elite careers have found relatively distinct trajectories for obtaining positions in different domains (Ellersgaard et al., Reference Ellersgaard, Lunding, Henriksen and Larsen2019), and mappings of transfers across elite domains find mixed evidence, particularly outside of the United States context (Blach‐Ørsten et al., Reference Blach‐Ørsten, Willig and Pedersen2017; Coen & Vannoni, Reference Coen and Vannoni2016; Hjelmar et al., Reference Hjelmar, Pedersen and Pedersen2021; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Buhmann‐Holmes and Egerod2021). Most notably, a study of Finnish elites over four decades finds little and decreasing mobility across elite positions (Ruostetsaari, Reference Ruostetsaari2021).

Most of these studies focus on single elite groups – most often on members of parliament or ministers – and their career trajectories either after leaving their previous elite position (e.g., Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Buhmann‐Holmes and Egerod2021) or prior to attaining their position (e.g., Blondel & Thiébault Reference Blondel and Thiébault1991; De Almeida & Pinto Reference De Almeida and Pinto2009). This is crucial information as prospects of post‐electoral elite positions may influence the behaviour of elected officials when they hold office, the recruitment of a former politician may benefit the organizations or firms hiring (Blanes i Vidal et al., Reference Blanes i Vidal, Draca and Fons‐Rosen2012; Egerod, Reference Egerod2022; Shepherd & You, Reference Shepherd and You2020) and prior experience may influence performance in elite positions (Vodová, Reference Vodová2021). We aim to contribute to this perspective by investigating career similarities and transfers across different political elite groups. This is an important perspective as it allows us to describe career similarity and transfers across elite groups and evaluate to which extent revolvers occupy top positions in other elite sectors at a given time.

We argue that variation in recruitment criteria across different elites and reputational cargo associated with elected positions constitute barriers to elite career similarity and transferability. The significance of such barriers varies depending on the specific context and institutional setting, but, across parliamentary democracies, they are likely to dampen overall elite interconnectedness – and to affect the relative likelihood of different types of transfers between elite positions. In other words, recruitment criteria and reputational cargo influence how likely doors are to revolve between different political elite groups.

We conceptualize elites as individuals capable of affecting societal outcomes because of their possession of top leadership positions in influential organizations (Ruostetsaari, Reference Ruostetsaari2021, p. 2). We focus on four political elite sectors distinguished by (1) whether obtaining the position requires election or appointment and (2) whether their source of power relates to the formal state apparatus or civil society. Elected politicians and top bureaucrats are among the most crucial elite groups because of their powerful positions in the formal delegation of political authority (Strøm et al., Reference Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008). We also include the most important organized interests based on their level of inclusion in policy‐making. In parliamentary systems with a corporatist legacy, interest groups have particularly prominent political positions (e.g., Christiansen et al., Reference Christiansen, Nørgaard, Rommetvedt, Svensson, Thesen and Öberg2010; Jochem & Vatter, Reference Jochem and Vatter2006; Mailand, Reference Mailand2020).Footnote 1 In the interest group sector, we distinguish between individuals possessing the highest level of elected office in groups, namely interest group chairs and those appointed as CEOs of the organizations as we argue that this affects the distinctiveness of recruitment criteria and the associated reputation.

Recruitment criteria define the requirements for entering an elite position in a given elite sector. Obtaining an elite position is usually the result of a long and multi‐phased selection process (Norris, Reference Norris1997; Prewit, Reference Prewit1970) in which designated gatekeepers in different phases choose between alternative candidates from specific criteria. In some settings, this process may be characterized by relative openness and mobility, whereas other settings may exhibit more closed career systems (Ruostetsaari, Reference Ruostetsaari2021). We argue that variation in recruitment criteria influences openness and, thus, the diversity of the career trajectories of elite sectors. If recruitment criteria are highly distinct and similar within an elite sector, individuals recruited to elite positions in the sector will have followed similar career trajectories. If recruitment criteria are distinct and similar across elite sectors, elites across sectors will hold skills of relevance to move across elite sectors. This line of reasoning reflects the idea of skill transferability across elite sectors that has inspired the revolving door literature (Egerod, Reference Egerod2022; Eggers & Hainmueller, Reference Eggers and Hainmueller2009; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Buhmann‐Holmes and Egerod2021; Shepherd & You, Reference Shepherd and You2020). However, as we will elaborate below, such transferability varies depending on the elite sector in focus.

Reputational cargo relates to the political brand carried by especially elected positions in politics or civil society (Hjelmar et al., Reference Hjelmar, Pedersen and Pedersen2021). Such reputations may be a relevant political ballast. For instance, serving as chair of a trade union will result in valuable skills and positive political branding as a Member of Parliament (MP) candidate for a social democratic party, but they may also be an unwanted load hindering transfer into elite positions in organizations with opposing political brands or in elite sectors where partisan neutrality is valued. As such, reputational cargo may be a valuable asset for elite transfer in some cases but a liability in others.

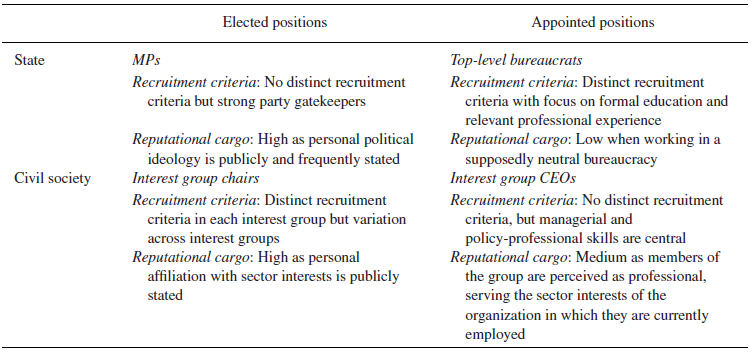

Table 1 illustrates how our argument plays out for the different groups, which we detail in the following.

Table 1. Recruitment criteria and reputational cargo across political elite groups

The parliamentary elite

For the parliamentary elite – elected politicians in national legislatures – the recruitment criteria are formally loose but politically restrictive. There are no formal qualifications for a parliamentary career except that candidates need to have citizenship and hold the right to vote at a national election. In practice, however, political parties guard access to Parliament. Candidate selection procedures vary across political systems and parties (Lundell, Reference Lundell2004), but the gatekeepers – most often party members and party delegates – tend to prefer party‐loyal candidates who can attract votes to the party (Dodeigne et al., Reference Dodeigne, Meulewaeter, Lesschaeve, Vandeleene, De Winter and Baudewyns2019). This results in a dual‐party strategy where many candidates are recruited after serving the party for years, while others are ‘parachuted’ into politics to attract volatile voters ( Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Kaldahl and Pedersen2020; Ohmura et al., Reference Ohmura, Bailer, Meiβner and Selb2018; Svallfors, Reference Svallfors2016, p. 65).

Some MPs move into even more powerful positions within the parliamentary elite by being appointed cabinet ministers. These are typically elected by voters and appointed by the prime minister (and the leaders of coalition parties), but in some systems, ministers may also be appointed without being MPs. Ministers thus constitute a special category within the parliamentary elite.

Because of the lack of distinct recruitment criteria (see Table 1), the parliamentary elite is likely to be relatively open to revolvers from other elite sectors. Individuals with a top position in another sector may already have a public profile that will help them attract votes to the party. However, because of the strong gatekeeper function of political parties, we may also expect elected politicians to be political professionals and pursue similar within‐sector careers fostering parliamentary expertise.

Since elected politicians’ campaign and seek public visibility to be re‐elected (Mayhew, Reference Mayhew1974), they are publicly and personally associated with specific political attitudes and values. The parliamentary elite, therefore, carries significant reputational cargo. This may limit the likelihood of MPs to revolve into other elite sectors. For instance, governmental officials may be quite cautious in recruiting people for top positions if they have an explicit political profile even if appointments to positions such as permanent secretary and agency head are political at‐will decisions ( Krause et al., Reference Krause, Lewis and Douglas2006; Svallfors, Reference Svallfors2016). However, if the reputational cargo of a politician is valuable to the receiving sector, transfers are possible. This is especially likely for transfers between party MPs and interest groups promoting similar political interests. In sum, in cases with no distinct recruitment criteria (but strong party gatekeeping) and high reputational cargo, we expect the following:

H1a: Career track similarity within the parliamentary elite is medium compared to other elite sectors.

H1b: More revolvers are found in the parliamentary elite than in other elite sectors.

H1c: When revolving, MPs are most likely to transfer to like‐minded interest groups.

The administrative elite

The administrative elite is very different from the parliamentary elite. Recruitment criteria are highly distinct. To qualify for a position in the administration, there are specific requirements focusing on relevant education and professional merits. A university degree is practically a conditio sine qua non simply because such an education is a formal requirement for appointment (Christensen, Reference Christensen, Peters and Pierre2004). Top positions in the administration are likely to equip the elites with additional qualifications such as political skills and process expertise that are relevant for recruitment particularly to appointed positions in interest groups (Svallfors, Reference Svallfors2016).

Recruitment and promotion patterns vary across countries depending on whether systems are mainly merit based or politicized (Askim et al., Reference Askim, Karlsen and Kolltveit2020, Reference Askim, Bach and Christensen2022). In a purely merit‐based system, administrative careers are clearly separated from political careers. This implies that reputational cargo associated with employment in the administrative sector is limited. Top bureaucrats are likely to be recruited based on their professional merits as documented by a career within the bureaucracy. Experience at the top level from other elite sectors – particularly those that come with reputational cargo – is more likely to be seen as a liability because this might challenge the partisan neutrality cultivated by a pure merit bureaucracy. In more politicized systems, (a small) part of the civil service is recruited on the basis of political criteria (Engelstad, Reference Engelstad, Best and Higley2018). This implies alternative recruitment channels for some top civil servants. In cases with distinct recruitment criteria and low reputational cargo (see Table 1), we expect the following:

H2a: Career track similarity within the administrative elite is high compared to other elite sectors.

H2b: Fewer revolvers are found in the administrative elite compared to other elite sectors.

H2c: The administrative elite is more likely to revolve than the other elite groups.

The interest group elite: Chairs

Most interest groups are democratic organizations in which the leadership is elected by members or representatives of the membership. The chairs of interest groups, therefore, share with the parliamentary elite that their position presumes a formal election (Albareda, Reference Albareda2020). In contrast to the parliamentary elite, most interest groups represent specific societal groups (e.g., business firms, workers in specific sectors, or patients) and election for political positions is only open to individuals who belong to the group that the organization represents (Halpin, Reference Halpin2014).Footnote 2 Therefore, recruitment criteria in each group are highly distinct, while they vary across the range of different interest groups (Table 1). For instance, many of the most important groups represent either employees or firms and, as such, top positions in private businesses or employment in specific sectors may lead to elite positions as interest group chairs (Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2015). We, therefore, expect multiple career trajectories to lead to a position as interest group chair but also few revolvers among interest group chairs.

The position as interest group chair is associated with reputational cargo because they serve as representatives of the group members by election (Table 1). They are elected based on not only their perceived professional skills but also their familiarity and identification with the kind of people they represent and with the organization. As such, they are associated with this group and their stated and perceived interests, which results in significant reputational cargo. As for the parliamentary elite, such cargo may be perceived as a relevant ballast for elite positions promoting similar interests or as unwanted weight for elite positions promoting conflicting interests or valuing neutrality. We, therefore, expect the following:

H3a: Career track similarity among interest group chairs is low relative to other elite sectors.

H3b: Fewer revolvers are found among interest group chairs relative to other elite sectors.

H3c: When revolving, interest group chairs are most likely to transfer to like‐minded party positions in the parliamentary elite.

The interest group elite: CEOs

Contrary to their political chairs, interest group CEOs are not necessarily recruited among the members of the organization. The presence of many different groups suggests that recruitment criteria may vary across organizations. However, the most powerful interest groups are likely to value professional qualifications related to politics in a broad sense (Albareda, Reference Albareda2020; Klüver & Saurugger, Reference Klüver and Saurugger2013). Most notably, previous experiences obtained during careers within the organization in question or relatively similar organizations are likely to be seen as qualifying for obtaining these positions (Table 1). Reputational cargo associated with CEOs is smaller than for elected positions, as CEOs do not represent a specific group or political position as explicitly as interest group chairs and MPs do (Table 1). Consequently, CEOs should be more capable of revolving into other elite sectors that value their political skills and process expertise, and positions as CEO should also be more open to revolvers holding relevant policy‐professional skills. We, therefore, expect the following:

H4a: Career track similarity among interest group CEOs is medium relative to other elite sectors.

H4b: More revolvers are found among interest group CEOs compared to other elite sectors.

H4c: Interest group CEOs are more likely to revolve than interest group chairs.

Data and analytical approach

We investigate the expectations derived from our theoretical framework using data on elite actors holding an elite position around 2018 in Denmark. As with any country, Denmark constitutes a specific political context relevant for recruitment criteria and reputational cargo. Parallel to the situation in many other countries, Danish politics has become increasingly professionalized, and the role of interest groups has changed towards less emphasis on institutionalized contacts and more on media lobbyism (Binderkrantz & Christiansen, Reference Binderkrantz and Christiansen2015) and towards weaker connections between specific parties and organizations (Allern et al., Reference Allern, Aylott and Christiansen2007). This may have led to increased elite mobility over time, particularly for recruitment to positions as interest group CEOs. On the other hand, the Danish bureaucracy is a clear example of a merit bureaucracy, and we, therefore, expect the barriers to move into the administrative elite to be particularly pronounced compared to more politicized systems. As a case, Denmark, therefore, provides substantial variation in recruitment criteria and reputational cargo across elite sectors for exploring the relevance of the theoretical ideas.

We operationalize elite positions as (1) holding a seat in the national Parliament (MPs) or being appointed as minister, (2) leading national administrative units (permanent secretaries and agency heads), (3) leading influential interest groups as a chair, or (4) as CEO. Influential interest groups are operationalized as interest groups taking a seat on at least two government boards or committees – that is, interest groups with privileged and institutionalized access (Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Pedersen and Beyers2017). While interest groups dominate the lobbying community in Denmark, parallel studies in other countries might include other lobbying actors, such as corporations or lobbying firms.

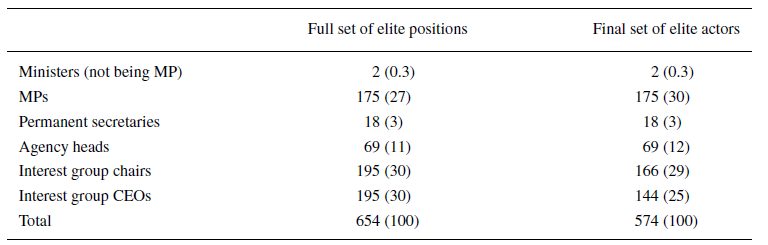

Table 2 illustrates the sample of elite actors. In Parliament, we focus on 175 MPs elected in the 2015 general election (excluding four North Atlantic MPs) and two ministers who were appointed after the election without being elected to Parliament. MPs and ministers are easy to identify on the parliamentary website (ft.dk). In the administration, we identified the persons holding positions as top civil servants in the central administration in late 2018 (two obtained their position on 1 January 2019). There were 18 permanent secretaries and 69 agency heads. These are also easily identified from governmental websites. Finally, from a list of members of governmental boards and committees (from 1 January 2015), we identified all interest groups that were represented as members of at least two boards or committees and then found their chair and CEO from the websites of the organizations – a very time‐consuming process. This elite sector is relatively difficult to map, and of the 195 interest groups with at least two seats on government boards and committees, we were able to identify and map the careers of 166 chairs and 144 CEOs.

Table 2. Number of elite actors in the relevant positions (percentages)

Abbreviations: CEOs, chief executive officers; MP, Member of Parliament.

In total, we collected data on 574 elite actors. Table A1 in the online Appendix presents descriptive information about the demographics and levels of education for the different elite groups. The parliamentary elite is the most gender balanced (with 37 per cent women), and MPs are, on average, also younger than members of the other elite groups. With respect to education, 95 per cent of the top bureaucrats and 85 per cent of the appointed CEOs of interest groups have a university master's degree, while this is the case for about half the members of the other two elite groups.

Career track similarity and elite transfers (revolvers)

We analyse career track similarity as sequences of employment until 2017. This deviates from traditional recruitment studies focusing on employment until obtaining a given elite position. As we are interested in possible elite position transfers or maintenance, we code every position until the year of our elite population (2018). In this way, we capture if an individual stays in a specific elite sector for years or has moved between elite sectors during his/her career.

We use sequence analysis, which takes into account the stages, their order and the duration of the individual career trajectories (Jäckle & Kerby, Reference Jäckle, Kerby, Best and Higley2018). This allows us to investigate the career data with respect to its different partitions and keep a holistic view of the complete sequence. To do this, we need to (1) collect and code information about their career on a year‐to‐year basis, (2) calculate distances between sequences and (3) perform a cluster analysis to identify the different types of elite career paths.

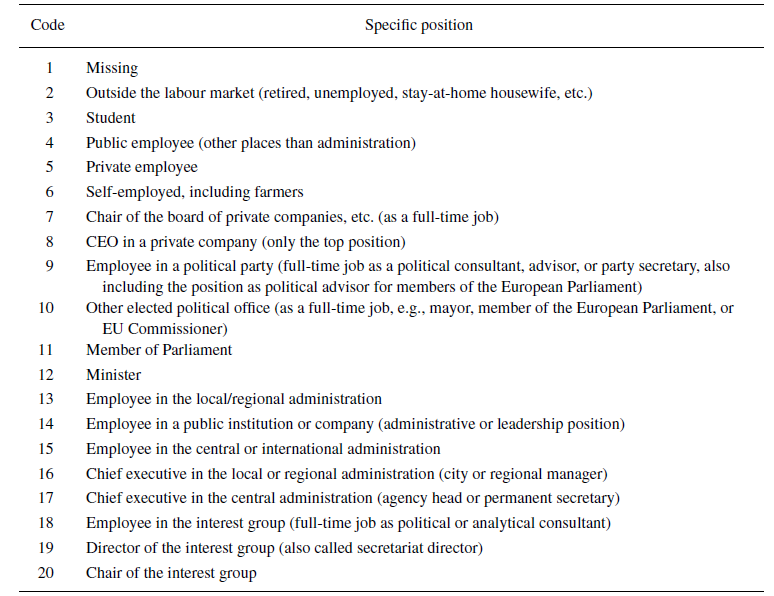

In order to perform the first step, we have coded the post‐educational careers of the 574 elite actors on a year‐to‐year basis until 2018 using biographical data obtained from various sources, such as parliamentary biographies, Who is Who, LinkedIn, portraits in the media, and websites. Hence, for every year after completing their first education (e.g., an MA degree in law), we code employment, for instance, in private businesses, municipal administration, or national administration. The coding process began with recording the name and location of the employer and a short description of the job function. We used these records to code employment in accordance with the coding scheme shown in Table 3. The coding scheme should balance analytical manageability and empirical detail. We use 20 codes that allow us to distinguish between different sectors of employment, that is, public, private, political, administrative and interest groups (elected or CEO), and between levels of positions, that is, employee or manager, local, regional or national. Hereby, we provide detailed mappings of the career tracks of our elite actors, including passage through non‐political sectors.

Table 3. Coding scheme for career paths

The second step is to calculate the distances between the various elite career sequences. We use the optimal matching algorithm (Gauthier et al., Reference Gauthier, Bühlmann, Blanchard, Gauthier, Bühlmann and Blanchard2014) to do this. This algorithm calculates the distance between two sequences as the cost of transforming one into the other by considering the insertion, deletion and substitution of career positions (Gabadinho et al., Reference Gabadinho, Ritschard, Mueller and Studer2011). We end up with a matrix including all the pairwise distances we need to perform the third step: the cluster analysis.

The purpose of the clustering analysis is to identify different types of elite career paths with the biographical data. We use Ward's hierarchically ascending clustering procedure to cluster similar sequences into groups. This procedure minimizes the total within‐cluster variance (Ward, Reference Ward1963). There is a trade‐off between opting for the lowest level of clustering and having analytically meaningful groups. Thus, different solutions are possible (Jäckle & Kerby, Reference Jäckle, Kerby, Best and Higley2018). We inform our choice by calculating the average silhouette width (ASW), which measures the coherence of the cluster assignment (Studer, Reference Studer2013). An eight‐cluster solution is associated with the highest ASW (0.25), indicating that this solution has the highest within‐cluster similarity and across‐cluster heterogeneity (statistics are provided in the online Appendix, Figure A1).

Elite career similarity is highest if elite actors from different sectors are distributed equally across these eight clusters of career trajectories, while it is lowest if elites in different sectors exclusively follow the same career trajectories. From the eight‐cluster solution, we can already tell that at least more than one career trajectory exists for our four elite groups.

We measure elite transfers or revolvers as individuals who have held an elite position in another sector during their career. This could, for instance, be an MP who has previously chaired a privileged interest organization or an interest group CEO who has previously served as head of a governmental agency. The following procedure was used to identify individuals moving between elite positions in different elite sectors:

-

(1) All individuals among the 574 elite actors who occupied at least two different positions as MP, chair, or CEO of an interest group, or as permanent secretary or agency head at any point of time in their career were identified.

-

(2) Positions as CEO or chair of interest groups not holding at least two seats on government boards or committees were excluded to include only elite positions as defined in the study.

-

(3) Individuals where more than 10 years had passed since their possession of an elite position in another elite group were removed.

This operationalization of revolvers is exclusive because we focus on shifts between elite positions. For instance, an MP may shift into a lower position in an interest group rather than become a CEO, which would not be seen as an instance of revolving according to our operationalization. We are interested in shifts across elite positions because of their crucial democratic relevance. However, as described above, our analysis of elite careers enables us to identify sector shifts at lower levels and across more sectors (e.g., the economic sector).

Elite career track similarity and elite sector transferability

The analysis is divided into two parts. First, we focus on career track similarity of the individuals in the four elite groups. Second, we analyse the extent to which elite actors transfer between elite positions in different sectors. With respect to career tracks, we first describe the eight career clusters identified in our full elite population and subsequently analyse which of these career tracks are most common for each of the four distinct elite groups. This allows us to map similarity in career tracks within and across elite groups.

In the interpretation of the career clusters, it is important to keep in mind that we include all positions after completed education until 2018. This means that long‐held elite positions may dominate the career track and influence the clustering analysis. We, therefore, cannot use this analysis to determine, for example, whether elite individuals hold the same educational or original occupational background as would have been of interest from an elite recruitment perspective. Rather – and key to our research question – we can use the analysis to determine whether elite individuals tend to occupy the same elite sector over time, specializing in political work of one political elite sector, or rather switch between political elite sectors, gathering general and transferable political skills and insights.

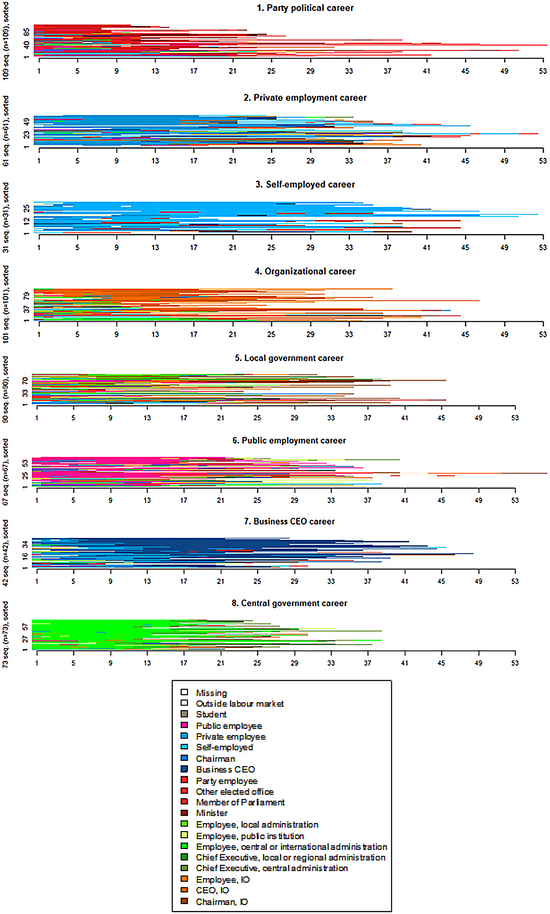

Figure 1 displays eight clusters of elite careers. The figure shows the career trajectory of each individual included in the specific cluster. These trajectories begin with the position obtained immediately after education and finish in 2018 (x‐axis). The trajectories are sorted according to how typical they are for the relevant cluster (y‐axis). In the online Appendix, we include a larger version of the figure (Figure A2) to allow for a closer visual inspection of the individual career trajectories. Based on the dominant positions held by individuals in the different clusters (as illustrated with the colour coding), it is evident that the clusters differ in significant ways:

-

(1) Party political career: Predominantly individuals who have been engaged in party politics – red coloured bars (N = 109).

-

(2) Private employment career: Predominantly individuals with a background as employees in a private company before ending in an elite position – blue colour (N = 61).

-

(3) Self‐employed career: Predominantly individuals with self‐employment on their way into the political elite – light blue colour (N = 31).

-

(4) Organizational career: Predominantly individuals employed in an interest group (but typically not in a top position) on their way to the political elite – orange colour (N = 101).

-

(5) Local government career: Mixed cluster with many colours. These individuals have typically spent a large part of their career in local government. Afterwards, they predominantly acquire elite positions as interest group chairs or MPs (N = 90).

-

(6) Public employment career: Predominantly individuals employed in the public sector before entering their elite position – pink colour (N = 67).

-

(7) Business CEO career: Predominantly individuals with a CEO background in a private business before entering an elite position – dark blue colour (N = 42).

-

(8) Central government career: Predominantly individuals who spent most of their career in central government – bright green colour (N = 73).

Figure 1. Career tracks of the Danish political elite, 2018. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

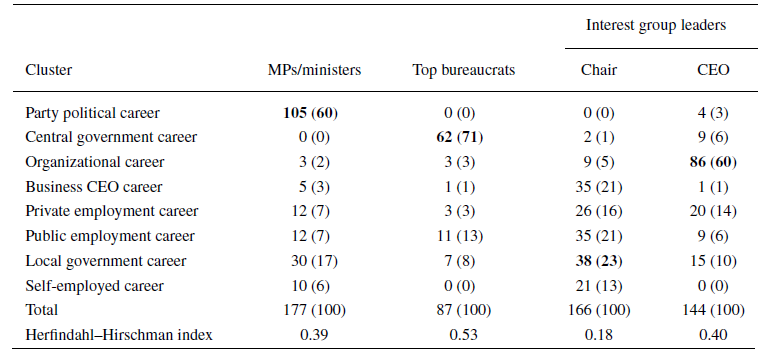

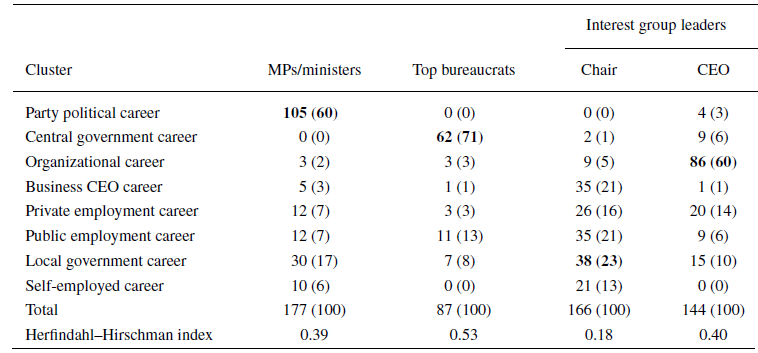

The eight clusters already indicate that individuals in the political elite do not follow the same career tracks. Table 4 shows the distribution of these career paths across the four elite groups. Bold numbers in the table show the most common career paths for the given elite group. The table also reports the Herfindahl–Hirschman index, which provides an overall metric for the level of diversity across the eight different clusters within each elite group. According to the expectations (H1‐4a), we expect the most career path similarity within the administrative elite, the least in the interest group chair elite, and medium similarity within the interest group CEO and parliamentary elites. The patterns revealed in Table 4 match these expectations.

Table 4. Career tracks across elite positions (percentages)

The Herfindahl–Hirschman index is the highest (0.53) for the administrative elite. Seventy‐one per cent of all top bureaucrats have followed a central government career, and other common careers involve public employment or experience from local government. Administrative experience mainly in the central government is thus close to an absolute requirement to reach top positions in ministries.

For MPs and interest group CEOs, the Herfindahl–Hirschman indexes are medium (0.39 and 0.40), which reflects highly similar career paths, although less ‘deterministic’ than for the administrative elite. Sixty per cent of all MPs follow a party‐political career, followed by 10 per cent in the local government career, illustrating the importance of political parties and parliamentary experience for this elite sector. Similarly, 60 per cent of the interest group CEOs followed an organizational career, suggesting that in a Danish context, public affairs skills are mainly obtained through interest organizations. A moderate share of CEOs (14 per cent) has gained experience from the private sector during their career.

Finally, the interest group chairs display the least career track similarity with a Herfindahl–Hirschman index score of only 0.18. Most noticeably, interest group leaders do not follow the careers common among other elite groups but, rather, gain experience from various parts of society, including both the private and public sectors. Among interest group chairs, we also find the strongest connection to the economic elite as 21 per cent have followed a business CEO career – reflecting the relatively high number of business groups where leadership is elected among the represented firms. Hence, interest group chairs are crucial for bringing diversity into the political elite, and even though this group of elite actors represents more diversity in career trajectories, their trajectories do not overlap with the more distinct trajectories of other elite sectors.

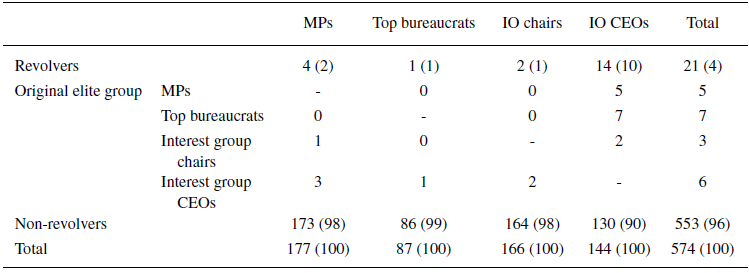

Turning to elite transfers and the prevalence of revolvers, we expected (H1‐4b) the number of revolvers to be relatively high among MP and interest group CEOs (no distinct recruitment criteria and reputational cargo an asset rather than a burden) and low among top bureaucrats (distinct recruitment criteria and reputational cargo mostly a burden) and interest group chairs (distinct recruitment criteria within groups). Table 5 shows the number of revolvers across elite groups and from which elite group the revolvers are recruited. The total number of revolvers is low (21), but the patterns can be seen as indicative with respect to the theoretical arguments. Still, most revolvers move into positions as interest group CEOs, where 10 per cent have passed through revolving doors from other elite groups.

Table 5. Individuals moving through revolving doors across elite sectors. N (%)

Abbreviations: CEOs, Chief executive officers.

We find only one revolver who moved from one of the other elite sectors into a top position in the bureaucracy. This particular revolver moved from a position as CEO for Danish regions, the organization representing the regions that manage the public hospitals sector. Having served in this capacity, he did not carry any reputational cargo and, thus, did not compromise the principles of pure merit cultivated within the civil service. In this way, the low number as well as the characteristics of this particular revolver support the idea of reputational cargo as an important hindrance to transfer into non‐partisan or neutral elite sectors.

The number and share of revolvers are also low for MPs and interest group chairs, indicating that the party‐gated recruitment for the parliamentary sector may be as distinct and restrictive as for interest group chairs. In the parliamentary sector, we have 21 ministers, two of whom are not recruited among MPs. One is recruited from a position as manager of a private elderly home, thus not being a member of the political elite. However, the other was clearly a revolver as he moved from a position as interest group CEO for The Confederation of Danish Employers to become minister of employment. He is thus a single but highly politically influential revolver among ministers.

Finally, we expected (H1‐4c) that most revolvers would come from the administrative sector or from positions as interest group CEOs who carry less reputational cargo, while transfers of MPs and interest group chairs should mainly take place when political interests and values match. The right‐hand column in Table 5 matches our expectations. Among the 21 revolvers identified in the political elite, six come from positions as interest group CEOs and seven from the administrative elite. Most interest group CEOs transfer into parliament or interest group chair positions, employing their political professional skill more publicly to promote a specific cause or ideology. The top bureaucrats have all revolved into positions as interest group CEOs. This indicates that the political neutrality and policy‐relevant skills acquired in a top position in the administration are valuable assets in the interest group sector. It is also remarkable that the position as interest group CEO stands out as central for elite transfer – in fact, only one person has made a shift that did not involve this position.

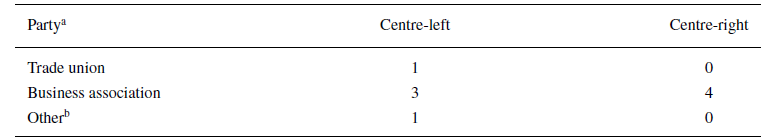

We can explore the theoretical mechanism further by investigating the political match of the nine transfers between the interest group and parliamentary sector as illustrated in Table 6. These matches must be interpreted with caution taking the low number of observations into account. According to the logic of reputational cargo, transfers should be most common between MPs from centre‐left parties and trade unions and MPs from centre‐right parties and business associations, respectively. This is only partly what we find. For the MPs associated with the centre right, there is a clear pattern – all transfers are to or from traditional business groups, such as associations of firms in the car manufacturing or agricultural sectors. For the centre‐left politicians, the pattern is less clear, with only one transfer from a trade union, three involving business associations and one to another type of group. However, it is notable that only one of the transfers involving a business group is a clear exception to our logic. The two others involve a transfer from the Socialist People's Party to an association of firms promoting more environmentally friendly technology and a shift from being a Social Democratic MP to a CEO position in a group organizing local distance heat and power stations, which are typically organized as user‐controlled organizations. These results support the relevance of the idea of reputational cargo and the associated importance of political matches but cannot be seen as conclusive evidence in light of the low number of revolvers.

Table 6. Political matches for revolvers between the interest group and parliamentary sectors (N = 9)

a Centre‐left parties: Red‐Green Alliance, Socialist People's Party, Social Democrats, Social Liberals, and the Alternative. Centre‐right parties: Liberals, Conservatives, Liberal Alliance, Christian Democrats, and the Danish People's Party.

b Other types of interest groups include public interest groups such as environmental groups, identity groups such as associations for patients and organizations of public institutions such as associations of universities.

Overall, these patterns of career similarity and elite transfers fit our theoretical ideas regarding limitations to elite interconnectedness. Generally, we find high career track similarity within and distinct career tracks across elite groups, and we only find 21 (4 per cent of our political elite individuals) revolvers. This means that by far, most individuals in the Danish political elite have held a top position only within their present elite sector. Moreover, the patterns of career track similarity and elite transfers fit our theoretical arguments regarding recruitment criteria and reputational cargo as two important mechanisms for hindering or promoting doors to revolve between elite sectors. It is particularly notable that we find very few shifts into most elite groups and that the lion's share of revolvers substitutes a position in politics or the bureaucracy with a position as interest group CEO.

Discussion

The political elite in democratic societies consists of distinct groups or sectors. A fundamental democratic question is the degree to which members of these different elite groups are intertwined. Do they move across elite sectors, promoting one unified and highly similar elite, or do they stay within distinct elite sectors, obtaining specialized and different political skills?

Political science and sociology have been preoccupied with the elite issue for more than a century. We contribute to the existing literature by investigating and theorizing about elite career track similarity and inter‐elite sector transfers for a given elite. We study this within an exclusive political elite of top bureaucrats, elected politicians and civil society lobbyists, mapping their careers from when they complete their education to 2018 – the year of our identification of the elite. We take a different perspective than usual for the elite recruitment literature and the revolving door literature, as we focus on describing the sitting elite at a given point in time. We include the time they spent in the elite (in contrast to the recruitment literature), and we study transfers across multiple elite sectors (in contrast to most of the revolving door literature).

Focusing on multiple elite groups, we argue that distinct recruitment criteria together with a reputational cargo in the form of reputational assets or liabilities limit both career track similarity and transfers across elite groups. Our investigation of 574 political elite individuals in Denmark concludes that the patterns of career similarity and elite transfer lend support to our suggested theoretical mechanisms and limit the overall number of revolvers found among the Danish political elite. These findings are the basis of two points of reflections: implications for Danish democracy and generalizability of the theoretical argument and empirical findings.

Regarding democratic implications, the systematic evidence provided in our analysis is more promising than the remarkable examples highlighted in the introduction. First, the administrative elite is effectively guarded against revolvers from other sectors within the political elite. This is seen as essential to upholding the image of a pure merit civil service resting on the values of partisan neutrality and re‐employability after political changes (Askim et al., Reference Askim, Bach and Christensen2022). Second, revolvers typically fit political demarcation, meaning that individuals may exercise influence from different positions but most commonly for the same cause. Third, the overall number of revolvers is limited, which means that the political elite is far from dominated by highly integrated elite actors moving back and forth between elite sectors.

However, the results also raise some concerns. First, even though 21 revolvers are not many, they might be highly influential given our strict definition of the political elite. Moving directly between a position as minister to a position as interest group CEO, leading major lobby efforts, can have important policy implications. As revolvers are an exclusive part of the elite actors, they may be an even stronger asset for actors striving to maximize their political influence. Second, the limited elite transfer may also indicate a risk of ending in a 'golden cage’ (Svallfors Reference Svallfors2016) when engaging in politics. If reputational cargo hinders future career prospects, as our results suggest, talented potential candidates may shy away from (elected) elite positions. In this way, the small number of revolvers may have positive as well as negative democratic implications.

Regarding the generalizability of the theoretical argument and empirical findings, the Danish case provides limitations as well as possibilities. Danish democracy rests on a long institutional history marked by a parliamentary system with tightly organized political parties and a merit‐based bureaucracy, effectively setting up barriers to party political appointments into the civil service and disincentives for civil servants to enter political careers. Its century‐long corporatist traditions also mean that major interest groups have developed their own strong administrative structures that offer career opportunities for both elected leaders and professional staff. Other European countries share some of these traits. However, they are radically different from especially the American presidential system, described by Heclo (Reference Heclo1977) and Lewis (Reference Lewis2008) as a government of strangers with presidential appointees moving in and out of the federal government with the political tide. Even among Western European countries, recruitment criteria and reputational cargo vary. On the one hand, British parliamentarism has a formal separation of parliamentary and administrative careers, while, on the other hand, French politics foster tight connections between the parliamentary elite and the bureaucracy. As with any country, Denmark is unique, and generalization requires more comparative investigations. However, the theoretical mechanisms of reputational cargo and recruitment criteria can be applied across countries, taking the specificities of elite groups into account. Our theory predicts that elite transfers and career track similarity will be higher when recruitment criteria are not distinct for relevant elite groups and reputational cargo is considered a ballast rather than a burden. These theoretical mechanisms are relevant for the understanding of elite interconnectedness across elite sectors in a given country as well as across countries.

[Correction added on 9 October 2023, after first online publication: The data files have been uploaded in this version.]

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Online Appendix

Dataset