Introduction

The year 2017 saw the third early elections in a row, a caretaker government and the third Borissov cabinet (Borissov III) come to power in Bulgaria. This time, Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB) formed a coalition with the nationalist United Patriots (OP) only, making it a reduced version of Borissov II. While both UP constituent parties had been support parties for the cabinet previously, now they officially signed the coalition agreement giving the nationalist wing in Bulgarian politics a major say in the political process in the country. Bulgaria continued to be the poorest country in the European Union (EU), but general socioeconomic indicators demonstrated positive developments. However, personnel issues and personal conflicts within the government made for a relatively unpopular cabinet.

Election report

Parliamentary elections

The year 2017 was no exception of the general election‐rich trend in Bulgaria since 2013 (early parliamentary elections in 2013 and 2014, local elections in 2015, presidential elections in 2016): early parliamentary elections were held on 26 March 2017. They followed Prime Minister Boyko Borissov's commitment that if the GERB nominee for president (Tsetska Tsacheva) failed to win the 2016 presidential elections, he would resign (Kolarova and Spirova Reference Kolarova and Spirova2017).

A total of 23 parties and coalitions took part in the elections. The campaign was marked by a growing controversy on the role played by Turkish citizens and officials in the parliamentary elections. Allegedly, for example, Mehmet Müezzinoğlu, Turkish Minister of Labour and Social Security, and Ambassador Suleiman Gyokche mobilized public opinion in favour of the new political party Association Democrats for Responsibility, Freedom and Tolerance (DOST) (Kolarova and Spirova Reference Kolarova and Spirova2016). In order to minimize the influx of Turkish party sympathizers who traditionally travel from Turkey to Bulgaria to vote in elections, MP candidates from the UP blocked the Turkish–Bulgarian border for days. In addition, old issues from the Communist past resurfaced as is common at election times when the Bulgarian Dossier Commission revealed that 78 of the candidate MPs in the elections had worked for the infamous State Security in the period before 1989.

The elections were held with no major problems or irregularities and returned five parties to Parliament, reducing substantially the number of parties in the National Assembly. The GERB emerged as the plurality winner with a small increase in its vote share. The Socialists also increased their representation, while both the nationalists (UP) and the Turkish minority party Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS) suffered a drop in its support and seat share. Especially for the latter, the 2017 elections marked the first substantial drop in support following the emergence of a competitor (DOST) after more than а decade of a rising share of seats. Another new development was the entry into Parliament of newcomer party Will (Volya). Founded by Vesselin Mareshki, a regional businessman in 2017, the party proclaims itself to be liberal and to fight corruption and over‐bureaucratization and has been in opposition since the elections.

Table 1. Elections to Parliament (Narodno sabranie) in Bulgaria in 2017

Notes: There is an option in the ballot ‘I don't support any of the nominated’, which received 87,850 votes (2.4%).

Source: Central Election Commission (2017).

Cabinet report

Following the election of the For Bulgaria (BSP) presidential candidate Rumen Radev in October 2016, Borissov handed in the resignation of his cabinet (Borissov II). Formally, President Rosen Plevneliev should have, at that point, dissolved Parliament and appointed a caretaker cabinet. However, Plevneliev decided to postpone the task and left it to the newly elected president Radev to do so in January 2017. Therefore, even though Borissov himself pushed for early elections, Borissov II held office until 27 January 2017, when the Gerdzhikov interim government was appointed. Gerdzhikov held office from 27 January to 4 May 2017 and focused on conducting the elections and preparing the country for the EU presidency in 2018.

Following the 25 March 2017 elections, the GERB and UP announced the agreement on the government programme on 13 April, and on 27 April President Roumen Radev gave GERB party leader Borissov a mandate to form a government. The Borissov III cabinet was voted into office on 4 May by the National Assembly.

The cabinet is a smaller and more right‐of‐centre version of Borissov II, with two of the more mainstream partners – Reformers’ Bloc (RB) and Alternative for Bulgarian Revival (ABV) – gone. The problems the alliance with the nationalist UP an alliance of the constituent parts of Patriotic Front and party ATAKA (see Kolarova and Spirova Reference Kolarova and Spirova2017) brings were demonstrated immediately. Only days after his appointment, UP Deputy Minister of Regional Development and Public Works, Pavel Tenev, resigned on 17 May after a scandal broke out because an old photograph appeared on the internet of him giving a Hitler salute to wax figures of Nazi officers in a museum in Paris. Similarly, the appointment of UP co‐chairman and Deputy Prime Minister Valeri Simeonov to head Bulgaria's National Council on Co‐operation on Ethnic and Integration Issues prompted protests among non‐governmental organizations (NGOs). Allegations of corrupt deals brought the Minister of Health down in early October when he was replaced by another GERB nominee.

Further problems emerged due to the personnel style of Prime Minister Borissov, who tends to choose people whom he trusts personally rather than those with political experience and often as a one‐man decision. That approach has dominated politics since 2009. It was demonstrated again in 2017 and led to problems with coalition co‐chair Simeonov, who expressed them publicly in the media, leading to further speculations about the instability of the coalition. Despite all these issues, Borissov remains the most popular politician in the country and his approval ratings remained stable at about 33 per cent through the year (Alpha Research 2017).

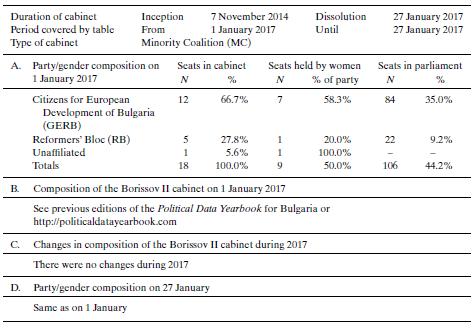

Table 2. Cabinet composition of the Borissov II cabinet in Bulgaria in 2017

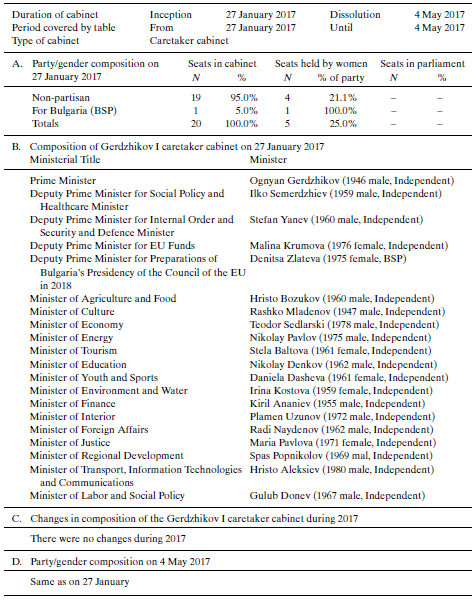

Table 3. Cabinet composition of the Gerdzhikov I caretaker cabinet in Bulgaria in 2017

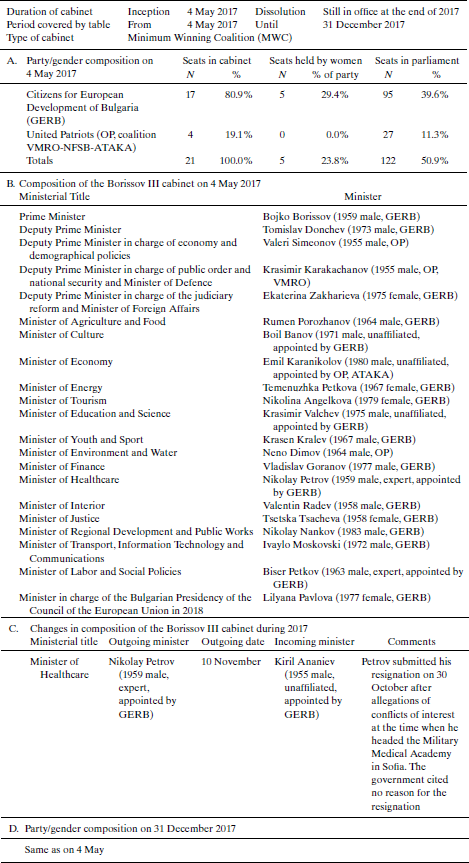

Table 4. Cabinet composition of the Borissov III in Bulgaria in 2017

Source: Council of Ministers (n.d.).

Parliament report

The 43rd National Assembly met for the last time on 11 January 2017 and was then dissolved. The 44th National Assembly convened on 19 April 2017. In terms of composition, one‐quarter of its members are women, and it has a diverse make up with a high percentage of non‐incumbents including a football referee, a model, and many generals and lawyers. Priorities for the Parliament in 2017 remained legislation on anticorruption and further reforms of the judiciary. The new anticorruption bill that environed a large and powerful anticorruption body with a seat in Parliament was passed by Parliament in December, but it provoked a lot of criticism by the opposition, which saw it as a possibility for political clean‐ups. The President threatened to veto the law (Capital Weekly 2017b). In addition, the UP introduced several bills protecting the Bulgarian language and religion. The preparations for Bulgaria's presidency of the EU also remained dominant throughout the year and somewhat dampened political conflict. The parliamentary opposition – the BSP and DPS mostly – promised a much more active opposition in 2018.

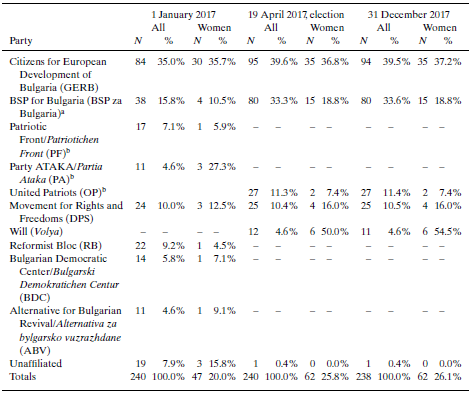

Table 5. Party and gender composition of parliament (Narodno sabranie) in Bulgaria in 2017

Notes. In previous years, the BSP for Bulgaria was named the Coalition for Bulgaria/Koalicia za Bulgaria (KB).

The PF and ATAKA ran together in the election under the name United Patriots (OP). The OP includes ATAKA (seven seats), the Bulgarian National Movement (VMRO) (11 seats) and the National Front for the Salvation of Bulgaria (NFSB) (nine seats).

Source: National Assembly Archive (n.d.).

Political party report

While there were no major changes in the leadership of the parties in Parliament, it is noteworthy that the centre‐right (formerly Reformist Block, a coalition partner in Borissov II) continued its disintegration and split into two different parties in early 2017. None managed to enter Parliament, thus ending the presence in Parliament of the descendants/remnants of the first anti‐Communist parties.

Issues in national politics

The most important issues in national politics in the country during 2017 were national security, the upcoming presidency of the EU in the first six months of 2018 and relations with the Republic of Macedonia (FYROM).

Security and the influx of migrants and refugees continued to be heavily present in the political discourse, especially with the nationalist party in government and despite a major drop in the number of people looking for asylum in Bulgaria (this dropped from 19,418 in 2016 to 3700 in 207, according to the Bulgarian Refugee Agency 2018). In a somewhat provocative decision, the Council of Ministers included the fence built previously and obstacle facilities on the Bulgarian–Turkish border in the list of strategic sites of national security significance, making it illegal for media to broadcast from the spot.

Another major theme in the political life was the upcoming Bulgarian presidency of the EU Council of Ministers in the first half of 2018. This caused a lot of trepidation about whether the country would be able to perform its duties well and speculation that the opposition was keeping things quiet because of this. In November 2017, the European Commission issued the first positive report on the country since the early membership years in which it praised the cabinet but criticized the Parliament for not taking enough action to reform the judiciary and make it more transparent (Capital Weekly 2017a).

In 2017, relations with Macedonia improved as the Bulgarian Parliament adopted a declaration supporting the draft for a good neighbourliness agreement with the Republic of Macedonia; and on 1 August 2017, Bulgarian Prime Minister Borissov and his Macedonian counterpart, Zoran Zaev, signed a Treaty of Good Neighbourliness between the two countries in Skopje. This paved the way for making the EU entry of Macedonia and resolving the issue with its official name a priority for the Bulgarian presidency in 2018.