Introduction

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct populations with continuous ancestral histories predating colonisation and deep connections to their territories and natural resources. They live in more than 90 countries, representing an estimated 476 million individuals – roughly 6% of the world’s population, but 19% of those living in poverty. While they own, occupy, or use about one quarter of the Earth’s land surface, they are also central to the stewardship of approximately 80% of the planet’s remaining biodiversity (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Social Inclusion, 2016; World Bank, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, International Development Association, 2023).

Globally, Indigenous peoples experience substantially lower life expectancy – up to 20 years less than non-Indigenous populations – and higher burdens of maternal and child mortality, undernutrition, infectious and respiratory diseases, chronic conditions (e.g., cardiovascular disease and diabetes), mental-health disorders, substance use, and exposure to violence. Access to timely, culturally appropriate care is often constrained by geographic remoteness, language barriers, poverty, inadequate sanitation, and fragile health-service networks (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Social Inclusion, 2016). In Brazil, despite a specific national health policy for Indigenous peoples, persistent structural barriers continue to limit the equitable reach and quality of services (Brazil, Ministry of Health, National Health Foundation (FUNASA), 2002; Brazil, Ministry of Health, Secretariat of Indigenous Health (SESAI), 2024).

Understanding the primary health challenges facing Indigenous communities is crucial for informing effective public health policies and allocating resources appropriately. Yet, national-scale temporal analyses contrasting Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations remain scarce, and no study has comprehensively examined mortality trends over more than a decade using nationwide data. Addressing this gap, the present study analyses mortality rates and proportional mortality trends in Brazil’s Indigenous population from 2010 to 2022, disaggregated by sex, age group, and ICD-10 disease categories, and contrasted with non-Indigenous populations to identify where disparities concentrate across the life course and to inform targeted, evidence-based interventions.

Methods

This ecological time-series study used open-access administrative datasets from the Brazilian government (Brazil, Ministry of Health, 2024; Brazil, Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), 2023a). The study covered Brazil between 2010 and 2022, corresponding to the period between the last two national demographic censuses (IBGE, 2023b). Demographic denominators were obtained from IBGE’s SIDRA Statistical Tables, and mortality data were obtained from the Mortality Information System (SIM) via TABNET – Vital Statistics (Brazil, Ministry of Health, 2024).

Brazil also maintains the Indigenous Health Information System (SIASI), which compiles demographic and health data from Indigenous communities served by the Indigenous Health Subsystem (SASI). While SIASI is a critical source of health monitoring data in Indigenous territories, its data are not publicly accessible and pose limitations for nationwide comparability. Therefore, consistent with previous national-level studies, open-access IBGE and DATASUS sources were used to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and comparability of results (Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Scatena and Santos2007; Brazil, Ministry of Health, Secretariat of Indigenous Health (SESAI), 2024).

The Indigenous group comprises individuals who self-identified as Indigenous in IBGE sources, while the non-Indigenous group aggregates those identifying as White, Black, Yellow (Asian), or Brown (Pardo) (IBGE, 2023a; IBGE, 2023b). Residence inside or outside Indigenous lands was considered for descriptive purposes (SESAI, 2024). Age was categorised as <1 year, 1–4, 5–9, and 10-year bands from 10–19 to ≥70 years, following IBGE and Ministry of Health conventions (Brazil, Ministry of Health, 2024). The primary contrasts were age-stratified; age-standardised overall rates were not computed because of the small absolute number of Indigenous deaths in some age groups, which could generate unstable rates. Therefore, differences in crude levels across populations with distinct age structures should be interpreted with caution (RIPSA, 2008).

Deaths were classified by sex (male, female), age (using the same categories as in the demographic data), and race/skin colour (Indigenous versus non-Indigenous). The place of death was also categorised as occurring inside a health facility (hospital or health service) or outside (home, public road, or other). Records with ‘ignored’ values in key variables were excluded from the analysis. Because race/skin colour in SIM may be recorded by health professionals or relatives rather than through self-identification, misclassification between Indigenous and non-Indigenous categories is possible; this limitation is addressed in the Discussion (Coimbra et al., Reference Coimbra, Santos and Welch2013; Santos et al., Reference Santos, Guimarães and Simoni2019).

Two dependent variables were analysed. (1) The mortality rate, defined as the number of deaths in Indigenous or non-Indigenous populations divided by the total population of each group and multiplied by 10,000 (RIPSA, 2008). (2) Proportional mortality was defined as the proportion of deaths among Indigenous peoples relative to total deaths from the same cause in the overall population, stratified by sex and ICD-10 disease group, and expressed as a percentage, based on data from the SIM (Brazil, Ministry of Health, 2024). Underlying causes of death were classified according to ICD-10 chapters (World Health Organization, 2019). Chapters VII (eye) and VIII (ear) were excluded due to very low annual counts in Indigenous populations, and Chapter XVIII (symptoms and abnormal findings) was excluded because it does not represent specific disease groups.

Mortality rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations in 2010 and 2022 were compared using Pearson’s chi-square test with a significance level of 5% (Minitab LLC, 2021). Analyses were performed in Minitab® version 19.2020.1. Temporal trends in proportional mortality were assessed with the Joinpoint Regression (JR) program, version 5.0.2 (National Cancer Institute (NCI), 2023). Models used log-linear specifications so that segment slopes could be interpreted as Annual Percentage Change (APC). In this study, the parameters used in the JR program were as follows: proportion-type dependent variable; annual interval as the independent variable; constant variance (homoscedasticity) assumption for error variance; first-order autocorrelation error structure estimated from the data; number of joinpoints set between 0 and 3; model selection by permutation test (4,499 permutations with a global significance level of 0.05); and parametric method (t-test and confidence interval) (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Fay and Feuer2000; NCI, 2023).

The JR program identifies inflexion points and calculates the APC for each segment. The Average Annual Percentage Change (AAPC) summarises the average APCs over multiple years. The null hypothesis states that the AAPC equals zero, suggesting no change in the variable’s trend over time. If the AAPC is significantly different from zero (p < 0.05), the trend is interpreted as increasing (positive AAPC) or decreasing (negative AAPC) (NCI, 2023; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Fay and Feuer2000).

Publicly available, de-identified data were used, without direct involvement of human participants or animals. The study protocol received ethics approval from the appropriate institutional committee, which waived the requirement for informed consent.

Results

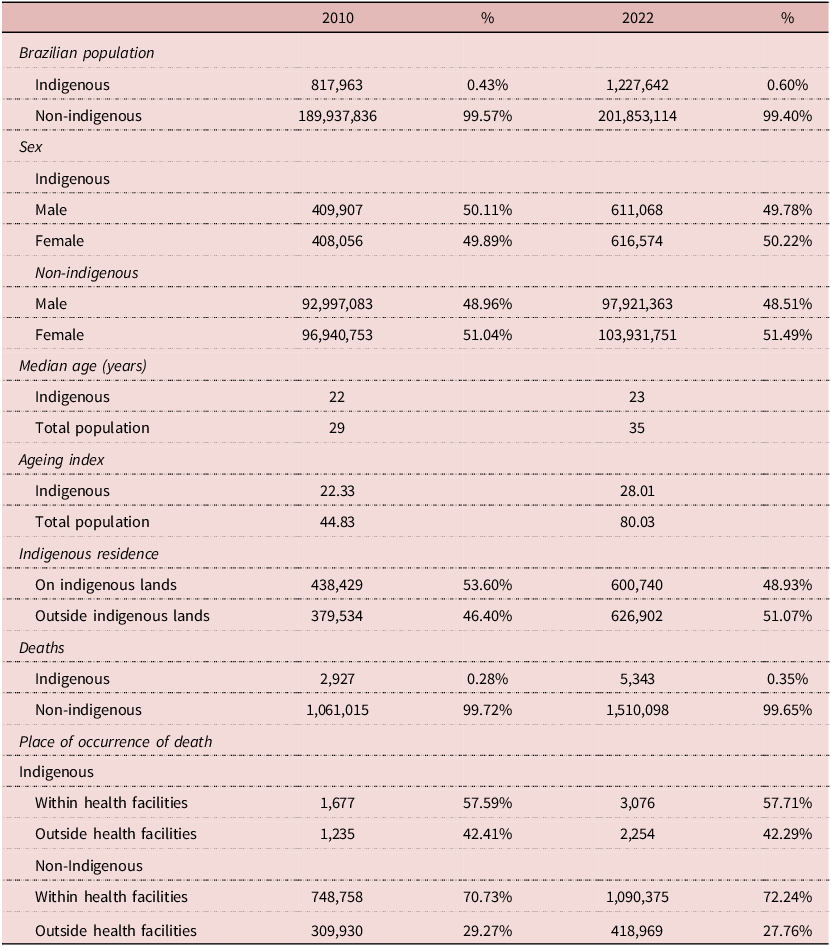

In 2022, Indigenous peoples comprised approximately 0.6% of the Brazilian population, representing a nearly 50% increase from 2010 (Table 1). The Indigenous population remained younger than the non-Indigenous population, with a lower median age (23 versus 35) and ageing index (28 versus 80) in 2022. The share of Indigenous peoples residing on Indigenous lands declined over the period, and by 2022, most lived outside these territories. Deaths among Indigenous peoples increased in absolute numbers from 2,927 in 2010 to 5,343 in 2022 (82.5% growth), compared with a 42.3% increase among non-Indigenous populations. In both years, more than 40% of Indigenous deaths occurred outside health facilities, versus fewer than 30% among non-Indigenous populations (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Brazilian Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Populations, 2010 and 2022

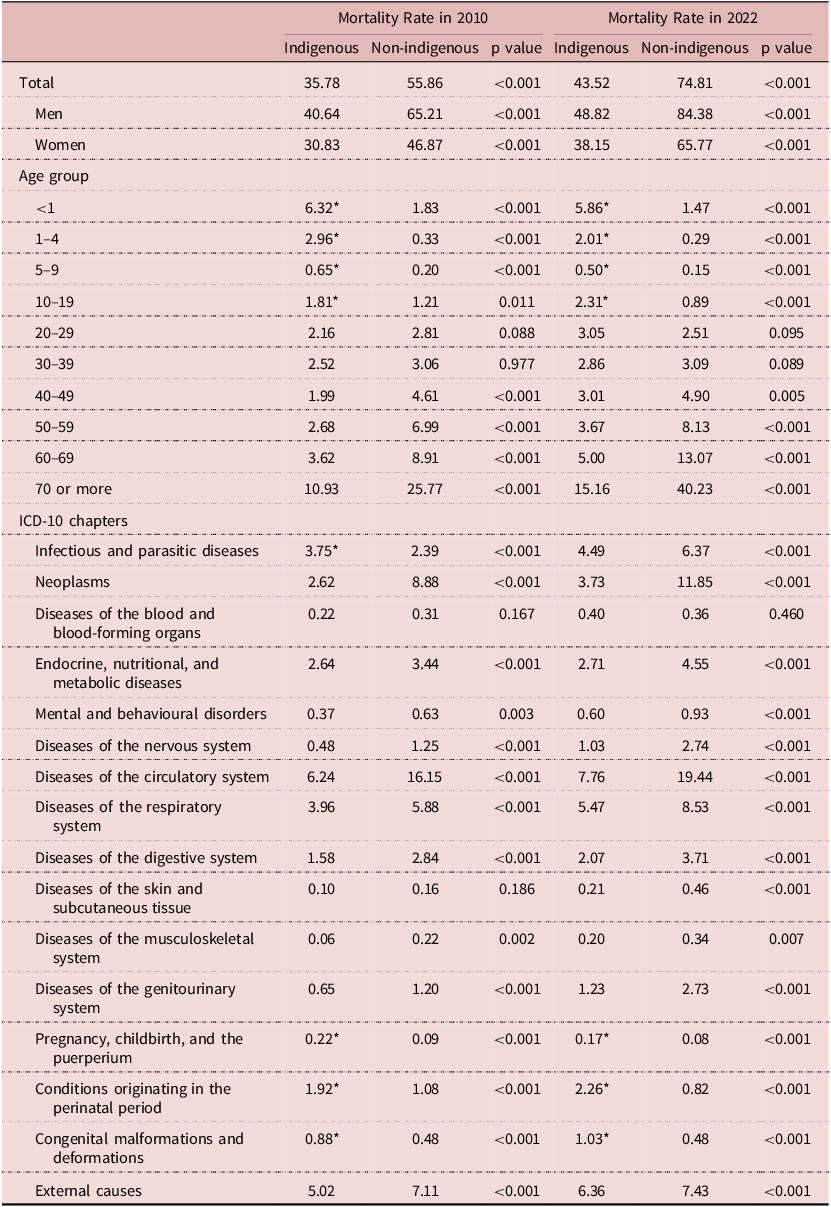

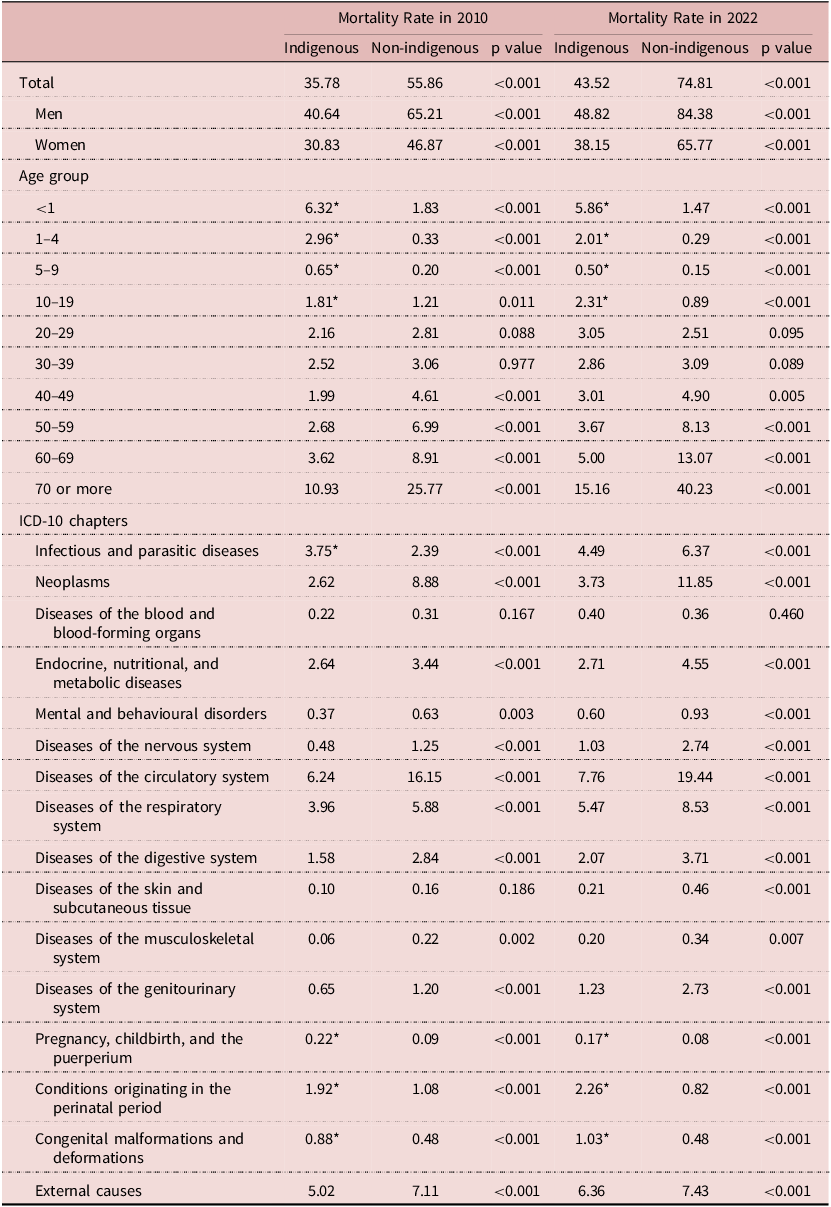

Crude mortality rates increased in both populations between 2010 and 2022, but remained consistently lower among Indigenous peoples (2010: 35.8 versus 55.9; 2022: 43.5 versus 74.8 per 10,000 population) (Table 2). Within each population, mortality was higher in males than in females. Differences in mortality rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations were statistically significant in both years (p < 0.05). Age-specific analyses showed marked contrasts: mortality was higher among Indigenous children and adolescents (0–19 years: 11.7 versus 3.6 per 10,000 in 2010; 10.7 versus 2.8 in 2022), while among adults aged ≥40 years, rates were lower in Indigenous than in non-Indigenous populations (19.2 versus 46.3 in 2010; 26.8 versus 66.3 in 2022; all p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2. Mortality Rates (per 10,000) among Indigenous and non-Indigenous Populations in Brazil by Sex, Age Group, and ICD-10 Disease Group, 2010 and 2022

Abbreviations: ICD-10 (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision).

Notes: Data from the 2010 and 2022 Brazilian Demographic Censuses (IBGE, 2023a; 2023b) and the Mortality Information System (SIM) via DATASUS (Brazil, Ministry of Health, 2024). Mortality rates are per 10,000 population. Chi-square tests were used to compare Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups (p < 0.05). *Indicates significantly higher mortality among Indigenous peoples compared with non-Indigenous populations.

In 2022, the leading causes of death among Indigenous children aged 0–9 years were perinatal conditions (278 deaths; 27.0%), respiratory diseases (177; 17.2%), infectious and parasitic diseases (146; 14.6%), congenital malformations (114; 11.0%), and external causes (76; 7.4%). Among adolescents aged 10–19 years, external causes predominated (155 deaths; 54.5%), with self-harm (34.2%), assaults (23.8%), and traffic accidents (14.2%) as the main contributors. In adults aged ≥40 years, circulatory diseases accounted for 27.0% of deaths (primarily stroke, acute myocardial infarction, and hypertension), followed by respiratory diseases (13.3%), neoplasms (11.3%), external causes (7.2%), and endocrine/metabolic conditions (7.1%). Within neoplasms, the most frequent were lung (45 deaths), prostate (39), cervical (38), and stomach cancers (35). Breast cancer mortality was comparatively low (21 deaths; 5.6% of all neoplastic deaths), whereas cervical cancer remained the leading neoplastic cause of death among Indigenous women. These age-specific distributions, although not presented in tables, are reported to highlight variations in leading causes of death across the life course.

According to Table 2, mortality rates in 2022 were significantly higher among Indigenous peoples for maternal causes (0.17 versus 0.08 per 10,000), perinatal conditions (2.26 versus 0.82), and congenital malformations (1.03 versus 0.48). These differences were already present in 2010, indicating persistently elevated Indigenous mortality in these categories across the study period. Other leading cause-of-death groups, such as circulatory diseases, neoplasms, external causes, respiratory diseases, and endocrine/metabolic conditions, also ranked highest in both populations, though with higher rates among non-Indigenous peoples.

JR analyses identified heterogeneous proportional mortality trends across ICD-10 chapters (Figures 1–2). In Figure 1A, infectious and parasitic diseases exhibited a significant decreasing trend (AAPC −6.6%; 95% CI −11.6 to −1.4; p = 0.014). By contrast, respiratory and digestive diseases showed significant increasing trends, with APCs of 2.1% (95% CI, 1.0 to 3.1; p = 0.001) and 3.2% (95% CI, 1.8 to 4.7; p < 0.001), respectively. In Figure 1B, circulatory diseases, neoplasms, and endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases all exhibited increasing trends, with statistically significant AAPCs (p < 0.05).

Figure 1. Segmented Trends in Proportional Mortality among Indigenous Peoples in Brazil, 2010–2022. (A) Infectious and Parasitic, Respiratory, and Digestive Diseases. (B) Circulatory Diseases, Neoplasms, and Endocrine/Metabolic Diseases. Abbreviations: APC = Annual Percentage Change; AAPC = Average Annual Percentage Change; CI = Confidence Interval. In the figures, APC_n refers to the n-th regression segment, with estimates presented as value (95% CI), p-value. Notes: Disease groups correspond to ICD-10 chapters. Proportional mortality represents the percentage share of deaths among Indigenous peoples, stratified by sex and ICD-10 disease group. A significant AAPC or APC (p < 0.05) indicates an increasing (positive) or decreasing (negative) trend.

Figure 2. Segmented Trends in Proportional Mortality among Indigenous Peoples in Brazil, 2010–2022. (A) External Causes and Injury/Poisoning, Mental Disorders, and Musculoskeletal Diseases. (B) Perinatal Conditions, Pregnancy/Childbirth, and Congenital Malformations.

Abbreviations: APC = Annual Percentage Change; AAPC = Average Annual Percentage Change; CI = Confidence Interval. In the figures, APC_n refers to the n-th regression segment, with estimates presented as value (95% CI), p-value. Notes: Disease groups correspond to ICD-10 chapters. Proportional mortality represents the percentage share of deaths among Indigenous peoples, stratified by sex and ICD-10 disease group. A significant AAPC or APC (p < 0.05) indicates an increasing (positive) or decreasing (negative) trend.

In Figure 2A, external causes presented an increasing trend (AAPC 5.0%, 95% CI 1.2 to 9.0, p = 0.001), while mental and musculoskeletal disorders were stable. In Figure 2B, proportional mortality increased for perinatal conditions (AAPC 6.4%, 95% CI 5.1 to 7.7, p < 0.001) and congenital malformations (AAPC 5.5%, 95% CI 4.4 to 6.5, p < 0.001), whereas pregnancy and childbirth-related conditions were stable. Of the remaining ICD-10 groups (neurological, haematological, genitourinary, and skin diseases), most showed stable proportional mortality, except haematological diseases, which increased significantly (AAPC 3.7%, 95% CI 1.6 to 5.9, p = 0.002) (Table 2).

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of mortality trends among Indigenous peoples in Brazil between 2010 and 2022. The Indigenous population grew by nearly 50% during this period, yet persistent inequities remained: mortality was higher among children and adolescents, lower among older adults, and a larger share of deaths occurred outside health facilities. Mortality rates for maternal, perinatal, and congenital conditions were consistently higher in Indigenous populations. JR revealed heterogeneous proportional mortality trends, with increases in nine disease groups (circulatory, neoplasms, endocrine/metabolic, external, perinatal, congenital, digestive, haematological, and nervous system diseases), a decline in infectious and parasitic diseases, and stability in others. These findings highlight both enduring disparities and evolving shifts in the mortality profile of Indigenous peoples.

Mortality among Indigenous children aged 0–9 years remained consistently higher than among non-Indigenous children. Leading contributors were perinatal conditions, respiratory and infectious/parasitic diseases, congenital malformations, and external causes. These findings align with previous studies documenting a disproportionate burden of infant and child mortality in Indigenous communities, often associated with preventable causes such as diarrhoea, pneumonia, and malnutrition (Lima et al., Reference Lima, Silva and D’Eça Júnior2020; Rebouças et al., Reference Rebouças, Goes and Pescarini2022). The prominence of congenital malformations is noteworthy and may plausibly relate to disparities in prenatal care, genetic predispositions, or limitations in diagnostic and certification practices. This pattern warrants further investigation to determine whether it reflects true epidemiological differences or persistent inequities in healthcare access and quality.

Among adolescents aged 10–19 years, external causes were the leading contributors to mortality, with suicide accounting for 34.2% of deaths. This pattern aligns with previous studies identifying suicide as a major cause of premature mortality among Indigenous youth (Souza et al., Reference Souza and Bonfim2020; Paiva de Araújo et al., Reference Paiva de Araujo, Fialho and Oliveira Alves2023). Suicide rates in these populations have consistently been reported at two- to threefold higher levels than the national average, contributing substantially to years of life lost. Multiple structural and social factors – including poverty, historical marginalisation, erosion of cultural identity, and limited future opportunities – are associated with this elevated risk (Souza et al., Reference Souza and Bonfim2020; Paiva de Araújo et al., Reference Paiva de Araujo, Fialho and Oliveira Alves2023). At the same time, potential underreporting and inconsistencies in death certification may bias recorded mortality estimates. These findings highlight the critical importance of implementing culturally safe and community-driven strategies to strengthen mental-health support and suicide prevention among Indigenous adolescents. However, sustainable progress also requires safeguarding Indigenous rights, territories, and self-determination, which are essential to strengthening cultural identity, reinforcing community cohesion, and improving overall mental well-being.

Among adults aged ≥40 years, crude mortality rates were lower among Indigenous (26.8 per 10,000 in 2022) than non-Indigenous populations (66.3 per 10,000). Similar findings have been reported elsewhere (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Ladeia and Marques2018; Lima et al., Reference Lima, Silva and D’Eça Júnior2020), but this pattern should be interpreted cautiously, as it may reflect differences in age structure, survival bias, and underreporting in remote areas rather than an actual lower vulnerability to chronic diseases. Circulatory diseases were the leading cause of death among Indigenous adults, followed by respiratory diseases, neoplasms, external causes, and endocrine/metabolic conditions – a pattern consistent with the broader national transition towards non-communicable diseases. Previous research has shown that urbanisation and lifestyle changes have increased the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in Indigenous populations (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Ladeia and Marques2018; Souza et al., Reference Souza and Bonfim2020), with Indigenous urban residents experiencing higher risks of obesity and cardiovascular mortality (Sardinha et al., Reference Sardinha, Lima and Ferreira2021). The observed increase in proportional mortality from circulatory diseases is consistent with these epidemiological shifts, although limitations in data quality and completeness constrain precise quantification of this trend.

In 2022, cancer was the second leading cause of death among non-Indigenous populations but ranked fifth among Indigenous peoples. This lower ranking should not be interpreted as reduced vulnerability, as diagnostic gaps, underreporting, and inequities in access to timely treatment are likely to contribute to these patterns. A study from Acre found that cancers linked to social vulnerability, including cervical, stomach, and liver cancers, represented nearly half of cancer deaths among Indigenous peoples (Borges et al., Reference Borges, Koifman and Koifman2019). Consistent with this, the present findings indicate persistently high cervical cancer mortality among Indigenous women, in contrast to comparatively low breast cancer mortality (Freitas Junior et al., Reference Freitas Junior, Soares and Gonzaga2015; Melo et al., Reference Melo, Silva and Santos2024). The overall rise in proportional mortality from neoplasms underscores the growing relevance of this disease group for Indigenous populations. Although the present analysis did not assess temporal trends by subtype, cervical cancer remained the leading neoplastic cause of death among Indigenous women. These findings reinforce the need to expand HPV vaccination and screening programmes and to improve equitable access to cancer diagnosis and treatment in Indigenous communities.

Maternal conditions remain a significant cause of preventable mortality among Indigenous peoples. National data show that maternal mortality has historically been at least twice as high among Indigenous women compared with non-Indigenous women (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Nogueira and Paiva2017). In the present analysis, absolute mortality rates due to pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period decreased between 2010 and 2022, yet proportional mortality in this category remained stable. This pattern may be related to improvements in maternal health services alongside demographic changes, yet absolute rates remain higher among Indigenous women. These findings underscore the importance of expanding access to prenatal, delivery, and postpartum care that is both effective and culturally sensitive.

Infectious and parasitic diseases have historically been among the leading causes of death in Indigenous populations (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Social Inclusion, 2016). In 2010, mortality rates from these conditions were higher among Indigenous peoples, but by 2022, they were higher in non-Indigenous populations. Several factors may help explain this apparent shift. The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected Indigenous peoples in 2020, with higher mortality compared with non-Indigenous groups (Soares et al., Reference Soares, Jamieson and Biazevic2022), especially among older adults with pre-existing conditions (Sardinha et al., Reference Sardinha, Lima and Ferreira2021; Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Nazima and Castilho-Martins2022). Although Indigenous peoples were prioritised in Brazil’s vaccination campaign beginning in early 2021, coverage remained uneven, which may have moderated – but not eliminated – the impact (Machado et al., Reference Machado, Ferron and Barddal2022). In addition, demographic expansion of the self-declared Indigenous population between 2010 and 2022 may have influenced denominator estimates, while long-standing challenges with underreporting and misclassification, especially in remote areas, persist. Taken together, these elements suggest that the apparent reversal in rates should be interpreted with caution: infectious and parasitic diseases remain important causes of death for Indigenous peoples, but structural inequities, demographic shifts, and data limitations likely contributed to the observed patterns in 2022.

The disparities observed in mortality among Indigenous peoples should also be interpreted in light of broader structural determinants. Brazil has a dedicated Indigenous Health Information System (SIASI), which collects health data from communities covered by the Indigenous Health Subsystem (SASI). However, these data are not publicly accessible and have limited comparability for nationwide analyses, contributing to the underrepresentation of Indigenous health in official statistics (Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Scatena and Santos2007). Similarly, the Mortality Information System (SIM) faces long-standing challenges in recording race/skin colour. Because classification is often reported by health professionals or relatives rather than self-identified, systematic misclassification of Indigenous peoples persists (Coimbra et al., Reference Coimbra, Santos and Welch2013; Santos et al., Reference Santos, Guimarães and Simoni2019).

An additional caveat concerns the substantial increase in the self-declared Indigenous population between the 2010 and 2022 censuses. This rise reflects not only demographic growth but also greater recognition and self-identification of Indigenous identity, refinements in census methods, and sociopolitical dynamics that encouraged self-declaration. Such changes directly affect denominator estimates for mortality rates. As a result, some of the lower crude rates observed in 2022 may partly reflect demographic reclassification rather than genuine improvements in health outcomes. This issue is particularly relevant for conditions where disparities have historically persisted, such as violence and chronic diseases. These dynamics reinforce the need for cautious interpretation of temporal trends and highlight the importance of triangulating census data with Indigenous-specific health information systems (e.g., SIASI). Importantly, these limitations extend beyond technical aspects and reflect structural racism and institutional barriers that continue to constrain the capacity to monitor and address health inequities affecting Indigenous peoples in Brazil (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Guimarães and Simoni2019).

This study has methodological limitations inherent to the use of secondary mortality data. Death certificates may be incomplete or inaccurate, and the Mortality Information System records only one underlying cause of death per certificate, restricting the analysis of multimorbidity. Some conditions may overlap across ICD-10 chapters, limiting comparability between categories. Underreporting remains a challenge, particularly in remote areas with weaker surveillance infrastructure. Moreover, race/skin colour in SIM is not always based on self-identification, introducing potential misclassification between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations (Coimbra et al., Reference Coimbra, Santos and Welch2013; Santos et al., Reference Santos, Guimarães and Simoni2019). Finally, crude rather than age-standardised mortality rates were analysed because of the small absolute number of Indigenous deaths in some age groups, which would yield unstable standardised estimates.

The findings of this study have important implications for Indigenous health policy. Many of the leading causes of death are preventable, particularly those affecting children, adolescents, and women during pregnancy and childbirth. Strengthening primary healthcare, ensuring broad vaccination coverage, improving prenatal and perinatal care, and addressing malnutrition remain essential priorities. Suicide prevention and expanded mental-health support should be urgently targeted to Indigenous youth. In parallel, strategies to prevent and manage non-communicable diseases – especially cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain cancers – must be scaled up in Indigenous communities, with an emphasis on culturally safe, community-driven approaches. However, beyond the health sector, achieving sustainable improvements in Indigenous health also depends on broader structural determinants. The health and well-being of Indigenous peoples are inextricably linked to the recognition and protection of their collective rights, ancestral territories, and cultural autonomy. International evidence underscores that safeguarding Indigenous lands, self-determination, and governance structures constitutes a foundational determinant of health equity and community resilience (Redvers et al., Reference Redvers, Celidwen and Schultz2022).

In conclusion, between 2010 and 2022, mortality among Indigenous peoples in Brazil remained characterised by inequities compared with the non-Indigenous population, with higher rates at younger ages and persistently elevated mortality in maternal, perinatal, and congenital conditions. A substantial share of Indigenous deaths continued to occur outside health facilities, underscoring barriers to timely access to care. These patterns highlight the persistence of preventable mortality and the urgent need for integrated and culturally appropriate strategies, developed in partnership with Indigenous communities, to expand healthcare access, strengthen surveillance, and address the structural determinants of health. Ensuring Indigenous peoples’ rights to land, cultural integrity, and self-determination is fundamental to achieving sustainable improvements in health and mortality outcomes, representing the ethical and structural foundations of Indigenous health in the context of historical colonisation and persistent social inequities.

Data availability statement

All datasets used in this study are publicly available through official Brazilian government platforms. Demographic data were obtained from the SIDRA Statistical Tables Bank (https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/pesquisa/censo-demografico/demografico-2022/universo-quilombolas-e-indigenas-por-sexo-e-idade; accessed May 2024). Mortality data were obtained from TabNet – Vital Statistics – Mortality (https://datasus.saude.gov.br/informacoes-de-saude-tabnet/) and from the Mortality Information System (SIM) (https://opendatasus.saude.gov.br/dataset/sim; accessed May 2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors have no acknowledgements to declare.

Author contributions

A.H. contributed to conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, original draft writing, and visualisation. E.S.M.C. contributed to conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, review and editing, visualisation, supervision, and project administration. S.C.K. contributed to conceptualisation, methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, review and editing, visualisation, supervision, and project administration.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity, or not-for-profit organisation.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work complied with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Health Sciences Sector, Federal University of Paraná (CAAE 51438521.2.0000.0102), which waived the requirement for informed consent.