1. Introduction

Gravity currents, also referred to as a density current, is a horizontal intrusion of higher density

![]() $\rho _c$

to an ambient fluid density

$\rho _c$

to an ambient fluid density

![]() $\rho _0 \neq \rho _c$

under gravitational acceleration. Such flows are prevalent in numerous natural phenomena, including sandstorms (Parsons Reference Parsons2000), powder-snow avalanches (Turnbull & McElwaine Reference Turnbull and McElwaine2007) and bushfires (Dold, Zinoviev & Weber Reference Dold, Zinoviev and Weber2006). Extensive reviews of gravity currents in geophysical flows, laboratory studies and numerical simulations are provided by Simpson (Reference Simpson1982) and Meiburg, Radhakrishnan & Nasr-Azadani (Reference Meiburg, Radhakrishnan and Nasr-Azadani2015). In this study, we examine a heavy fluid initially at rest, which is released into a lighter ambient fluid at

$\rho _0 \neq \rho _c$

under gravitational acceleration. Such flows are prevalent in numerous natural phenomena, including sandstorms (Parsons Reference Parsons2000), powder-snow avalanches (Turnbull & McElwaine Reference Turnbull and McElwaine2007) and bushfires (Dold, Zinoviev & Weber Reference Dold, Zinoviev and Weber2006). Extensive reviews of gravity currents in geophysical flows, laboratory studies and numerical simulations are provided by Simpson (Reference Simpson1982) and Meiburg, Radhakrishnan & Nasr-Azadani (Reference Meiburg, Radhakrishnan and Nasr-Azadani2015). In this study, we examine a heavy fluid initially at rest, which is released into a lighter ambient fluid at

![]() $t=0$

. Upon release, the dense fluid collapses, generating a flow characterised by a distinct head region, simulating a lock release. As the gravity current develops, a well-defined shape is recognised, characterised by three distinct regions: a highly turbulent head, a quasi-steady body and a shallower trailing tail (Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Balachandar, García and Bock2008; Zordan, Schleiss & Franca Reference Zordan, Schleiss and Franca2018).

$t=0$

. Upon release, the dense fluid collapses, generating a flow characterised by a distinct head region, simulating a lock release. As the gravity current develops, a well-defined shape is recognised, characterised by three distinct regions: a highly turbulent head, a quasi-steady body and a shallower trailing tail (Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Balachandar, García and Bock2008; Zordan, Schleiss & Franca Reference Zordan, Schleiss and Franca2018).

Over the past few decades, gravity currents have been extensively studied through numerous experiments and numerical simulations. Two commonly used configurations are lock-exchange and lock-release set-ups. In the lock-exchange configuration, heavy fluid and lighter ambient fluid are initially separated by a removable lock gate within a rectangular channel, occupying substantial volumes on either side. Upon gate removal, the fluids interchange due to the density difference, typically producing symmetrical, counter-propagating gravity currents. In contrast, the lock-release configuration (also referred to as a finite-volume release) involves a finite volume of heavy fluid initially confined behind a gate, which, upon release, intrudes unidirectionally into the ambient fluid. This configuration has become a standard framework for investigating the propagation and mixing dynamics of gravity currents. The evolution of gravity currents is typically classified into three primary regimes: the initial acceleration phase, the inertial regime and the viscous regime. Within the inertial regime, two distinct phases can be identified: the slumping phase and the inertial phase. When viscous forces dominate over inertial effects and the viscous term governs the propagation, the gravity current transitions into the viscous regime (Ungarish Reference Ungarish2007, Reference Ungarish2020; Zemach & Ungarish Reference Zemach and Ungarish2020).

Initially, the gravity current undergoes an acceleration phase, during which the gravitational potential energy of the dense fluid is converted into kinetic energy, driving the current from rest to its maximum front velocity. This phase is followed by the slumping phase, characterised by a nearly constant front height and velocity. Subsequently, the gravity current transitions into the inertial phase, where the buoyancy force balances the inertial force. Eventually, the current enters the viscous phase, in which viscous forces dominate over buoyancy forces. The prediction of spreading rates for two- and three-dimensional (3-D) planar gravity currents, as well as axisymmetric and fully cylindrical currents, across both the inertial and viscous regimes, has been extensively documented in Cantero et al. (Reference Cantero, Lee, Balachandar and García2007).

The Froude number,

![]() $ \textit{Fr} $

, characterises the dynamics of gravity currents, particularly during their transition phases. During the slumping phase, the Froude number of the gravity current is expressed as

$ \textit{Fr} $

, characterises the dynamics of gravity currents, particularly during their transition phases. During the slumping phase, the Froude number of the gravity current is expressed as

\begin{align} \textit{Fr} = \frac {u^*_f}{\sqrt {g^\prime H^*}} , \end{align}

\begin{align} \textit{Fr} = \frac {u^*_f}{\sqrt {g^\prime H^*}} , \end{align}

where

![]() $u^*_f$

is the front velocity,

$u^*_f$

is the front velocity,

![]() $g^\prime =g^*(\rho _c^*-\rho _0^*)/\rho _0^*$

is the reduced gravity,

$g^\prime =g^*(\rho _c^*-\rho _0^*)/\rho _0^*$

is the reduced gravity,

![]() $g^*$

is the gravitational acceleration acting in the negative

$g^*$

is the gravitational acceleration acting in the negative

![]() $z$

direction and

$z$

direction and

![]() $H^*$

is the channel height. Note that in this manuscript, variables with asterisks (

$H^*$

is the channel height. Note that in this manuscript, variables with asterisks (

![]() $*$

) denote dimensional variables. Laboratory experiments and numerical simulations aimed to predict the front velocity during the slumping phase are well documented in the open literature (Benjamin Reference Benjamin1968; Huppert & Simpson Reference Huppert and Simpson1980; Shin, Dalziel & Linden Reference Shin, Dalziel and Linden2004; Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Lee, Balachandar and García2007). These studies provide empirical expressions indicating that the Froude number for a full-depth release gravity current in an unstratified ambient is approximately 0.5. For a deeply submerged current with

$*$

) denote dimensional variables. Laboratory experiments and numerical simulations aimed to predict the front velocity during the slumping phase are well documented in the open literature (Benjamin Reference Benjamin1968; Huppert & Simpson Reference Huppert and Simpson1980; Shin, Dalziel & Linden Reference Shin, Dalziel and Linden2004; Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Lee, Balachandar and García2007). These studies provide empirical expressions indicating that the Froude number for a full-depth release gravity current in an unstratified ambient is approximately 0.5. For a deeply submerged current with

![]() $h_{\kern-1.5pt f} \rightarrow 0$

(where

$h_{\kern-1.5pt f} \rightarrow 0$

(where

![]() $h_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

is the dimensionless height of the current body), Huppert & Simpson (Reference Huppert and Simpson1980) reported the Froude number as

$h_{\kern-1.5pt f}$

is the dimensionless height of the current body), Huppert & Simpson (Reference Huppert and Simpson1980) reported the Froude number as

![]() $1.19\sqrt h_{\kern-1pt f}$

, which is higher than

$1.19\sqrt h_{\kern-1pt f}$

, which is higher than

![]() $\sqrt h_{\kern-1pt f}$

predicted by Shin et al. (Reference Shin, Dalziel and Linden2004) but lower than

$\sqrt h_{\kern-1pt f}$

predicted by Shin et al. (Reference Shin, Dalziel and Linden2004) but lower than

![]() $\sqrt {2h_{\kern-1pt f}}$

predicted by Benjamin (Reference Benjamin1968). Recent studies by Lam et al. (Reference Lam, Chan, Sutherland, Manasseh, Moinuddin and Ooi2024c

) employed the stratification scaling reported by Ungarish & Huppert (Reference Ungarish and Huppert2002) and Ungarish (Reference Ungarish2006) to predict the spreading rate of fully cylindrical currents propagating in stratified ambient during the slumping phase. These empirical results show excellent agreement with numerical simulations where the effects of stratification are considered in the empirical predication demonstrating the spreading rate decreases with increasing strength. Other studies on gravity currents propagating into a stratified ambient have been reported in Ungarish & Huppert (Reference Ungarish and Huppert2002), Ungarish (Reference Ungarish2005); Lam et al. (Reference Lam, Chan, Hasini and Ooi2018a

,

Reference Lam, Chan, Hasini and Ooib

); Zhou & Venayagamoorthy (Reference Zhou and Venayagamoorthy2020), Dai, Huang & Hsieh (Reference Dai, Huang and Hsieh2021), Zahtila et al. (Reference Zahtila, Lam, Chan, Sutherland, Moinuddin, Dai, Skvortsov, Manasseh and Ooi2024) and Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Ooi, Thomas, Zahtila and Iaccarino2024).

$\sqrt {2h_{\kern-1pt f}}$

predicted by Benjamin (Reference Benjamin1968). Recent studies by Lam et al. (Reference Lam, Chan, Sutherland, Manasseh, Moinuddin and Ooi2024c

) employed the stratification scaling reported by Ungarish & Huppert (Reference Ungarish and Huppert2002) and Ungarish (Reference Ungarish2006) to predict the spreading rate of fully cylindrical currents propagating in stratified ambient during the slumping phase. These empirical results show excellent agreement with numerical simulations where the effects of stratification are considered in the empirical predication demonstrating the spreading rate decreases with increasing strength. Other studies on gravity currents propagating into a stratified ambient have been reported in Ungarish & Huppert (Reference Ungarish and Huppert2002), Ungarish (Reference Ungarish2005); Lam et al. (Reference Lam, Chan, Hasini and Ooi2018a

,

Reference Lam, Chan, Hasini and Ooib

); Zhou & Venayagamoorthy (Reference Zhou and Venayagamoorthy2020), Dai, Huang & Hsieh (Reference Dai, Huang and Hsieh2021), Zahtila et al. (Reference Zahtila, Lam, Chan, Sutherland, Moinuddin, Dai, Skvortsov, Manasseh and Ooi2024) and Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Ooi, Thomas, Zahtila and Iaccarino2024).

In the inertial and viscous phases, the front velocity of the gravity current has been observed to decay following a power-law behaviour,

![]() $u_{\kern-1pt f} \sim t^{\beta }$

, where

$u_{\kern-1pt f} \sim t^{\beta }$

, where

![]() $\beta$

is a constant reported in various studies. The asymptotic behaviour of gravity currents in both planar and cylindrical releases in an unstratified ambient has been comprehensively studied previously (Fay Reference Fay1969; Fannelop & Waldman Reference Fannelop and Waldman1972; Hoult Reference Hoult1972; Huppert & Simpson Reference Huppert and Simpson1980; Huppert Reference Huppert1982; Rottman & Simpson Reference Rottman and Simpson1983; Marino, Thomas & Linden Reference Marino, Thomas and Linden2005; Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Lee, Balachandar and García2007, Reference Cantero, Balachandar, García and Bock2008).

$\beta$

is a constant reported in various studies. The asymptotic behaviour of gravity currents in both planar and cylindrical releases in an unstratified ambient has been comprehensively studied previously (Fay Reference Fay1969; Fannelop & Waldman Reference Fannelop and Waldman1972; Hoult Reference Hoult1972; Huppert & Simpson Reference Huppert and Simpson1980; Huppert Reference Huppert1982; Rottman & Simpson Reference Rottman and Simpson1983; Marino, Thomas & Linden Reference Marino, Thomas and Linden2005; Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Lee, Balachandar and García2007, Reference Cantero, Balachandar, García and Bock2008).

The propagation of 3-D planar and cylindrical gravity currents propagating in an unstratified ambient has been extensively studied during the slumping and inertial phases. It can be hypothesised that the initial conditions have negligible influence on the long-term dynamics, as the flow tends to ‘forget’ its initial state during the inertial phase regime. In this regime, the effects of three-dimensionality become significant, leading to the breakdown of spanwise and circumferential coherence (Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Lee, Balachandar and García2007). However, the study by Zgheib, Bonometti & Balachandar (Reference Zgheib, Bonometti and Balachandar2014) demonstrates that the initial release shape can influence the evolution of the current well into the inertial phase in the planar or axisymmetric configurations. Laboratory experiments and numerical simulations of the Boussinesq, non-axisymmetric, finite-release gravity current by Zgheib et al. (Reference Zgheib, Bonometti and Balachandar2014) revealed that the initial non-circular shape of the release persists throughout the entire duration of both the experiments and simulations.

Previous literature has investigated the dynamics of planar gravity currents in unstratified ambients, focusing on varying aspect ratios and depth ratios of the heavy fluid on a horizontal plane (or uniform slope). A common approach to accelerate the 3-D development of a gravity current flow is to introduce a small random disturbance to the initial density field, thereby speeding up the transition to turbulence (Härtel et al. Reference Härtel, Kleiser, Michaud and Stein1997; Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Balachandar, García and Ferry2006; Zgheib, Ooi & Balachandar Reference Zgheib, Ooi and Balachandar2016). However, the introduction of random disturbances into the initial density profile may influence the formation and evolution of Kelvin–Helmholtz (K–H) billows due to spatially random density fluctuations. These billows are known to play a critical role in irreversible mixing by promoting reversible stirring of ambient fluid into the current and subsequently enhancing mixing with the heavy fluid (Ottolenghi et al. Reference Ottolenghi, Adduce, Inghilesi, Armenio and Roman2016a

; Lam et al. Reference Lam, Chan, Cao, Sutherland, Manasseh, Moinuddin and Ooi2024a

,

Reference Lam, Chan, Cao, Sutherland, Manasseh, Moinuddin and Ooib

). In this study, we systematically perturb the gravity current flow by introducing sinusoidal perturbations in the spanwise direction where the front of the heavy fluid at

![]() $t=0$

is wavy, which may either disrupt or promote the formation of lobes and clefts, an aspect that has not been extensively examined. This approach increases the frontal surface area of the heavy fluid as the number of repeating waves in the spanwise direction,

$t=0$

is wavy, which may either disrupt or promote the formation of lobes and clefts, an aspect that has not been extensively examined. This approach increases the frontal surface area of the heavy fluid as the number of repeating waves in the spanwise direction,

![]() $k_y$

, increases, while maintaining a constant fluid volume. The motivation for this configuration stems from both natural and practical scenarios in which structured spanwise undulations may arise. These include engineered constraints such as shaped openings, topographically influenced release profiles or flow obstructions. Analogous examples can be found in bushfire smoke or contaminant clouds spreading over complex terrain, or heavy fluid propagating along urban rooftops or vegetated canopies. Understanding how different spatial scales of initial perturbations affect flow evolution and mixing offers valuable insights into the persistence and impact of initial conditions. A planar configuration is adopted to reduce computational cost, and no ambient stratification is imposed to isolate the effects of frontal perturbations on the gravity current dynamics.

$k_y$

, increases, while maintaining a constant fluid volume. The motivation for this configuration stems from both natural and practical scenarios in which structured spanwise undulations may arise. These include engineered constraints such as shaped openings, topographically influenced release profiles or flow obstructions. Analogous examples can be found in bushfire smoke or contaminant clouds spreading over complex terrain, or heavy fluid propagating along urban rooftops or vegetated canopies. Understanding how different spatial scales of initial perturbations affect flow evolution and mixing offers valuable insights into the persistence and impact of initial conditions. A planar configuration is adopted to reduce computational cost, and no ambient stratification is imposed to isolate the effects of frontal perturbations on the gravity current dynamics.

This study aims to investigate the effects of imposed initial spanwise perturbations on the frontal surface of a heavy fluid and their influence on the dynamics of full-depth gravity currents propagating along a horizontal plane. We present results from fully 3-D direct numerical simulations (DNSs) of planar gravity currents propagating in an unstratified ambient with varying number of repeating waves in spanwise direction,

![]() $k_y$

, at moderate Reynolds number,

$k_y$

, at moderate Reynolds number,

![]() $ \textit{Re} $

. A detailed examination of the mixing properties of the gravity currents is conducted, with analysis of density contours used to compare flow structures under different initial conditions and

$ \textit{Re} $

. A detailed examination of the mixing properties of the gravity currents is conducted, with analysis of density contours used to compare flow structures under different initial conditions and

![]() $ \textit{Re} $

. The 3-D structure of the advancing front and the associated mixing mechanisms are compared between the classical planar lock-release configuration (without perturbation) and cases with initial perturbation by varying the number of repeating waves. The paper is organised as follows: § 2 outlines the numerical procedure, including the governing equations, initial and boundary conditions and problem formulation. Section 3 discusses the conceptual framework for determining the mixing properties of planar gravity currents. Section 4 presents the simulation results and accompanying discussions. Finally, conclusions are drawn in § 5.

$ \textit{Re} $

. The 3-D structure of the advancing front and the associated mixing mechanisms are compared between the classical planar lock-release configuration (without perturbation) and cases with initial perturbation by varying the number of repeating waves. The paper is organised as follows: § 2 outlines the numerical procedure, including the governing equations, initial and boundary conditions and problem formulation. Section 3 discusses the conceptual framework for determining the mixing properties of planar gravity currents. Section 4 presents the simulation results and accompanying discussions. Finally, conclusions are drawn in § 5.

2. Numerical set-up

Figure 1 shows the initial configuration of full-depth planar release gravity currents in an unstratified ambient. The streamwise, spanwise and wall-normal directions are represented by

![]() $x^*,y^*$

and

$x^*,y^*$

and

![]() $z^*$

, respectively (herein

$z^*$

, respectively (herein

![]() $^*$

represents dimensional variables). The height of the domain

$^*$

represents dimensional variables). The height of the domain

![]() $L_{z}^{*}=H^*$

is taken as the length scale. The velocity scale,

$L_{z}^{*}=H^*$

is taken as the length scale. The velocity scale,

![]() $U^*$

, time scale,

$U^*$

, time scale,

![]() $T^*$

and

$T^*$

and

![]() $ \textit{Re} $

are defined as

$ \textit{Re} $

are defined as

Figure 1. Sketch of the computational domain for the 3-D planar simulation. The streamwise, spanwise and wall-normal directions are represented by

![]() $x^*,y^*$

and

$x^*,y^*$

and

![]() $z^*$

, respectively. The heavy fluid is located at the upstream end of the domain and has a density of

$z^*$

, respectively. The heavy fluid is located at the upstream end of the domain and has a density of

![]() $\rho _c^*$

. The heavy and ambient fluid has the same height as the height of the domain

$\rho _c^*$

. The heavy and ambient fluid has the same height as the height of the domain

![]() $L_z^*$

. The density of the ambient is homogeneous and has a density of

$L_z^*$

. The density of the ambient is homogeneous and has a density of

![]() $\rho _0^*$

. The initial condition of the heavy fluid with different front surface areas is included in the plot and is coloured grey.

$\rho _0^*$

. The initial condition of the heavy fluid with different front surface areas is included in the plot and is coloured grey.

The computational domain is a rectangular channel with

![]() $L_x^* = 24$

(increased to

$L_x^* = 24$

(increased to

![]() $L_x^* = 40$

for the cases with higher

$L_x^* = 40$

for the cases with higher

![]() $ \textit{Re} $

to mitigate the influence of backward propagating disturbances reflecting off the back wall on the gravity current),

$ \textit{Re} $

to mitigate the influence of backward propagating disturbances reflecting off the back wall on the gravity current),

![]() $L_y^* = 1.5$

and

$L_y^* = 1.5$

and

![]() $L_z^* = 1$

. At time

$L_z^* = 1$

. At time

![]() $t^{*}=0$

, a rectangular lock with a streamwise length

$t^{*}=0$

, a rectangular lock with a streamwise length

![]() $x_0^* = 4/3$

and height

$x_0^* = 4/3$

and height

![]() $H^*=L_z^*$

along the spanwise (

$H^*=L_z^*$

along the spanwise (

![]() $y$

) direction, containing heavy fluid with density

$y$

) direction, containing heavy fluid with density

![]() $\rho _c^*$

, is positioned at the upstream end of the channel. For the initial frontal condition, the surface is perturbed sinusoidally about the mean location,

$\rho _c^*$

, is positioned at the upstream end of the channel. For the initial frontal condition, the surface is perturbed sinusoidally about the mean location,

![]() $x^{*}=x_{0}^{*}$

, with the following form:

$x^{*}=x_{0}^{*}$

, with the following form:

where

![]() $k_y$

is the number of repeating waves in the spanwise direction which varies between 2 to 8 and

$k_y$

is the number of repeating waves in the spanwise direction which varies between 2 to 8 and

![]() $A^{*}$

is the amplitude of

$A^{*}$

is the amplitude of

![]() $A^{*}=0.1$

. The initial volume of the heavy fluid is kept constant for all cases. In the long wave limit of

$A^{*}=0.1$

. The initial volume of the heavy fluid is kept constant for all cases. In the long wave limit of

![]() $k_y \rightarrow 0$

, this becomes the ‘classic’ case of a lock release in a homogeneous ambient. The density of the ambient fluid (

$k_y \rightarrow 0$

, this becomes the ‘classic’ case of a lock release in a homogeneous ambient. The density of the ambient fluid (

![]() $\rho _0^*$

) is homogeneous and

$\rho _0^*$

) is homogeneous and

![]() $\rho _0^* \lt \rho _c^*$

. Details of the 3-D planar simulations are shown in table 1.

$\rho _0^* \lt \rho _c^*$

. Details of the 3-D planar simulations are shown in table 1.

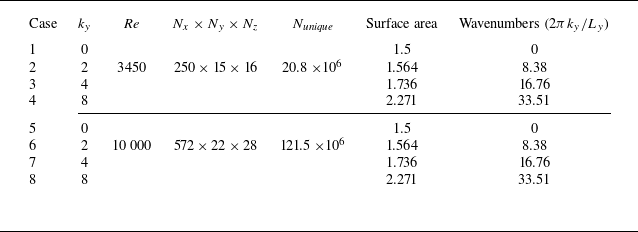

Table 1. Details of the computational mesh. The number of repeating waves in the spanwise direction,

![]() $k_y$

, varies from 0 to 8. The total unique number of grid points in the computational domain is denoted by

$k_y$

, varies from 0 to 8. The total unique number of grid points in the computational domain is denoted by

![]() $N_{\textit{unique}}$

.

$N_{\textit{unique}}$

.

The 3-D, planar release gravity currents have been simulated using Nek5000, a spectral element, incompressible flow solver (Fischer, Lottes & Kerkemeier Reference Fischer, Lottes and Kerkemeier2008) with the Boussinesq approximation used to approximate the effects of gravity. It is hence assumed that the density difference between two fluids is less than

![]() $5\,\%$

(Turner Reference Turner1979) to neglect the influence of density differences in the inertial and diffusion terms and retain only in the buoyancy term. Nek5000 has been widely used in various fields (Lu et al. Reference Lu, Aljubaili, Zahtila, Chan and Ooi2023; Cui et al. Reference Cui, Cao, Yan and Wang2024a

,

Reference Cui, Cao, Yan and Wangb

; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Chan, Zahtila, Lu, Iaccarino and Ooi2025) due to its high accuracy and scalability in simulating complex flow phenomena. The problem is non-dimensionalised, in which variables are denoted without asterisks, by

$5\,\%$

(Turner Reference Turner1979) to neglect the influence of density differences in the inertial and diffusion terms and retain only in the buoyancy term. Nek5000 has been widely used in various fields (Lu et al. Reference Lu, Aljubaili, Zahtila, Chan and Ooi2023; Cui et al. Reference Cui, Cao, Yan and Wang2024a

,

Reference Cui, Cao, Yan and Wangb

; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Chan, Zahtila, Lu, Iaccarino and Ooi2025) due to its high accuracy and scalability in simulating complex flow phenomena. The problem is non-dimensionalised, in which variables are denoted without asterisks, by

where

![]() $\rho$

is the density of the fluid,

$\rho$

is the density of the fluid,

![]() $u_i$

is the velocity for 3-D flow, and the dimensional density scales,

$u_i$

is the velocity for 3-D flow, and the dimensional density scales,

![]() $\rho ^*_0$

, and

$\rho ^*_0$

, and

![]() $\rho ^*_c$

represent the ambient and heavy fluid, respectively. This yields the following non-dimensional governing equations:

$\rho ^*_c$

represent the ambient and heavy fluid, respectively. This yields the following non-dimensional governing equations:

where

![]() $p$

is pressure and

$p$

is pressure and

![]() $e_i^g$

is the unit vector in the direction of gravity. In tensor notation for (2.4)–(2.6), a summation is assumed over a repeated index. The Schmidt number is

$e_i^g$

is the unit vector in the direction of gravity. In tensor notation for (2.4)–(2.6), a summation is assumed over a repeated index. The Schmidt number is

![]() $ \textit{Sc}=\nu ^*$

/

$ \textit{Sc}=\nu ^*$

/

![]() $\kappa ^*$

(where

$\kappa ^*$

(where

![]() $\nu ^*$

is the kinematic viscosity and

$\nu ^*$

is the kinematic viscosity and

![]() $\kappa ^*$

is the molecular diffusivity). Although saline liquid, which is typically used in experiments, has

$\kappa ^*$

is the molecular diffusivity). Although saline liquid, which is typically used in experiments, has

![]() $ \textit{Sc}=700$

, it is found that, when

$ \textit{Sc}=700$

, it is found that, when

![]() $ \textit{Sc}$

is of the order of 1 or larger, there is only a weak scaling with the dynamics of the gravity current and this does not significantly affect the bulk flow results (Härtel et al. Reference Härtel, Meiburg and Necker2000; Necker et al. Reference Necker, Härtel, Kleiser and Meiburg2005; Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Lee, Balachandar and García2007; Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Lee, Balachandar and García2007; Bonometti & Balachandar Reference Bonometti and Balachandar2008; Dai Reference Dai2015; Lam et al. Reference Lam, Chan, Cao, Sutherland, Manasseh, Moinuddin and Ooi2024b

). Therefore,

$ \textit{Sc}$

is of the order of 1 or larger, there is only a weak scaling with the dynamics of the gravity current and this does not significantly affect the bulk flow results (Härtel et al. Reference Härtel, Meiburg and Necker2000; Necker et al. Reference Necker, Härtel, Kleiser and Meiburg2005; Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Lee, Balachandar and García2007; Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Lee, Balachandar and García2007; Bonometti & Balachandar Reference Bonometti and Balachandar2008; Dai Reference Dai2015; Lam et al. Reference Lam, Chan, Cao, Sutherland, Manasseh, Moinuddin and Ooi2024b

). Therefore,

![]() $ \textit{Sc}=1$

is used in the current simulations.

$ \textit{Sc}=1$

is used in the current simulations.

Slip, impermeable symmetry boundary conditions are applied at the two ends of the streamwise domain,

![]() $x=0$

, and

$x=0$

, and

![]() $x=L_x^{*}/H^{*}$

, as well as at the top boundary (

$x=L_x^{*}/H^{*}$

, as well as at the top boundary (

![]() $z=1$

) for both the velocity and density fields. Periodic boundary conditions are used in the spanwise (

$z=1$

) for both the velocity and density fields. Periodic boundary conditions are used in the spanwise (

![]() $y$

) direction. At the bottom boundary,

$y$

) direction. At the bottom boundary,

![]() $z=0$

boundary, a no-slip boundary condition is applied for the velocity field and Neumann zero boundary conditions are used for density field.

$z=0$

boundary, a no-slip boundary condition is applied for the velocity field and Neumann zero boundary conditions are used for density field.

We systematically investigated the effect of spanwise perturbations of the initial release on the dynamics of planar gravity currents propagating in an unstratified ambient at

![]() $ \textit{Re} $

of 3450 and 10 000. In the present study, four perturbations with a different number of repeating waves in the span,

$ \textit{Re} $

of 3450 and 10 000. In the present study, four perturbations with a different number of repeating waves in the span,

![]() $k_y = 0$

, 2, 4 and 8, were considered and simulated. The number of spectral elements employed for planar release simulations at low- and high-

$k_y = 0$

, 2, 4 and 8, were considered and simulated. The number of spectral elements employed for planar release simulations at low- and high-

![]() $ \textit{Re} $

are

$ \textit{Re} $

are

![]() $N_x \times N_y \times N_z = 250\ \times 16\ \times 15$

and

$N_x \times N_y \times N_z = 250\ \times 16\ \times 15$

and

![]() $573 \times 22 \times 29$

, respectively. The grid distribution within the spectral element follows the Gauss–Legendre–Lobatto grid spacing. A seventh-order polynomial is used in this study and the total number of unique grid points is approximately

$573 \times 22 \times 29$

, respectively. The grid distribution within the spectral element follows the Gauss–Legendre–Lobatto grid spacing. A seventh-order polynomial is used in this study and the total number of unique grid points is approximately

![]() $20.8\times 10^6$

and

$20.8\times 10^6$

and

![]() $121.5\times 10^6$

for low- and high-

$121.5\times 10^6$

for low- and high-

![]() $ \textit{Re} $

cases. Grid stretching (geometrical progression with power coefficient of 1.05) is applied along the wall-normal direction (

$ \textit{Re} $

cases. Grid stretching (geometrical progression with power coefficient of 1.05) is applied along the wall-normal direction (

![]() $z$

) where the grid size at the bottom part is finer than at the top. The computational grid has a grid spacing of

$z$

) where the grid size at the bottom part is finer than at the top. The computational grid has a grid spacing of

![]() $0.003 \leqslant \Delta \leqslant 0.02$

for

$0.003 \leqslant \Delta \leqslant 0.02$

for

![]() $ \textit{Re}=3450$

and

$ \textit{Re}=3450$

and

![]() $0.001 \leqslant \Delta \leqslant 0.015$

for

$0.001 \leqslant \Delta \leqslant 0.015$

for

![]() $ \textit{Re}=10\,000$

. We have ensured that our grid resolution is sufficient to resolve all of the turbulent length scales and also meet the requirement of

$ \textit{Re}=10\,000$

. We have ensured that our grid resolution is sufficient to resolve all of the turbulent length scales and also meet the requirement of

![]() $\Delta x = \Delta y = \Delta z \approx (\textit{Re}\textit{Sc})^{-1/2}$

where

$\Delta x = \Delta y = \Delta z \approx (\textit{Re}\textit{Sc})^{-1/2}$

where

![]() $ \textit{Sc} = 1$

, see Dai (Reference Dai2015) and Zahtila et al. (Reference Zahtila, Lu, Chan and Ooi2023). A variable time step is used to ensure that the Courant number is always less than 0.5 and the simulation is run for a total dimensionless time of

$ \textit{Sc} = 1$

, see Dai (Reference Dai2015) and Zahtila et al. (Reference Zahtila, Lu, Chan and Ooi2023). A variable time step is used to ensure that the Courant number is always less than 0.5 and the simulation is run for a total dimensionless time of

![]() $T=100$

.

$T=100$

.

3. Properties of the gravity current

When the body of heavy fluid, initially at rest, is released into a lighter ambient fluid at

![]() $t=0$

, it collapses under the action of gravity, resulting in an intrusion characterised by a distinct head region. Upon formation, the gravity current exhibits a well-defined structure comprising a highly turbulent head, a quasi-steady body and a shallower trailing tail (Middleton Reference Middleton1966, Reference Middleton1967; Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Balachandar, García and Bock2008; Zordan et al. Reference Zordan, Schleiss and Franca2018). This study focuses on the mixing properties of the head and body of the current. In the later stages of evolution, the tail elongates and gradually dissipates into the ambient fluid, becoming negligible in subsequent calculations.

$t=0$

, it collapses under the action of gravity, resulting in an intrusion characterised by a distinct head region. Upon formation, the gravity current exhibits a well-defined structure comprising a highly turbulent head, a quasi-steady body and a shallower trailing tail (Middleton Reference Middleton1966, Reference Middleton1967; Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Balachandar, García and Bock2008; Zordan et al. Reference Zordan, Schleiss and Franca2018). This study focuses on the mixing properties of the head and body of the current. In the later stages of evolution, the tail elongates and gradually dissipates into the ambient fluid, becoming negligible in subsequent calculations.

As the gravity current propagates over long distances, two primary instabilities arise in the head region, where bottom drag and interfacial friction play critical roles in enhancing turbulence. Interfacial friction with the overlying ambient fluid generates K–H billows, which entrain ambient fluid into the current. As the gravity current propagates along the no-slip wall, buoyancy-driven instabilities occur, squeezing the lighter ambient fluid beneath the head. The formation of lobe-and-cleft structures is primarily attributed to the no-slip impermeable boundary condition at the bottom wall (Simpson Reference Simpson1972). Simpson (Reference Simpson1982) postulated that these lobe-and-cleft structures are the result of convective instability, which develops as the gravity current flows over the less dense ambient fluid, producing the characteristic unsteady lobe-and-cleft features.

The body of the gravity current, located immediately behind the head, constitutes the largest portion of the current’s length. This quasi-steady region can be further divided into two distinct layers: a lower layer consisting of a thin, dense fluid near the bottom wall, and an upper layer characterised by K–H billows. These billows form due to shear instabilities at the interface with the ambient fluid, as turbulence develops downstream from the head. The body continuously draws heavy fluid towards the head, sustaining the propagation of the current.

It is important to clarify that while both K–H and lobe-and-cleft instabilities arise naturally in the flow, the present study does not focus on analysing their instability mechanisms. Instead, the primary focus is on the influence of imposed initial spanwise perturbations on the evolution and mixing behaviour of gravity currents. The K–H and lobe-and-cleft structures that emerge during the simulations are discussed where relevant, but their underlying instability dynamics are not the subject of detailed investigation in this manuscript.

3.1. Three-dimensional indicator function

To quantify the mixing properties of planar gravity currents with varying initial perturbations, three methods are employed. The first method focuses on the head of the current, recognised as the most turbulent region. The second method examines the density changes within the gravity current. Lastly, local stirring and mixing rates are computed for both the head and body to evaluate the effects of varying

![]() $k_y$

on the dynamics of the planar gravity current.

$k_y$

on the dynamics of the planar gravity current.

The gravity current head can be captured using the physical height of the gravity current

![]() $h(x,y,t)$

with a 3-D indicator function

$h(x,y,t)$

with a 3-D indicator function

![]() $I(x,y,z,t)$

, following the method proposed by Zgheib et al. (Reference Zgheib, Ooi and Balachandar2016). The indicator function is expressed as

$I(x,y,z,t)$

, following the method proposed by Zgheib et al. (Reference Zgheib, Ooi and Balachandar2016). The indicator function is expressed as

\begin{align} I(x,y,z,t)= \begin{cases} 1, & \text{in the current head if $h(x,y,t) \gt h_{\textit{th}}$}, \\ 0, & \text{elsewhere} \,. \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} I(x,y,z,t)= \begin{cases} 1, & \text{in the current head if $h(x,y,t) \gt h_{\textit{th}}$}, \\ 0, & \text{elsewhere} \,. \end{cases} \end{align}

The gravity current head

![]() $\tilde {h}_{\textit{head}}(x,y,t)$

is defined as the region on the

$\tilde {h}_{\textit{head}}(x,y,t)$

is defined as the region on the

![]() $x{-}y$

plane where the physical height

$x{-}y$

plane where the physical height

![]() $h(x,y,t)$

exceeds a threshold value

$h(x,y,t)$

exceeds a threshold value

![]() $h_{\textit{th}}$

. The corresponding properties of the gravity current head are then computed as

$h_{\textit{th}}$

. The corresponding properties of the gravity current head are then computed as

where

![]() $\tilde {h}_{\textit{head}}$

,

$\tilde {h}_{\textit{head}}$

,

![]() $\tilde {V}_{\textit{head}}$

and

$\tilde {V}_{\textit{head}}$

and

![]() $\tilde {M}_{\textit{head}}$

are the physical height, volume and mass of the head. The density of the head,

$\tilde {M}_{\textit{head}}$

are the physical height, volume and mass of the head. The density of the head,

![]() $\rho _{\textit{head}} = \tilde {M}_{\textit{head}}/\tilde {V}_{\textit{head}}$

, is calculated at every time instance.

$\rho _{\textit{head}} = \tilde {M}_{\textit{head}}/\tilde {V}_{\textit{head}}$

, is calculated at every time instance.

This procedure is taken to define the head of the current is illustrated in figure 2. This method was originally employed by Zgheib et al. (Reference Zgheib, Ooi and Balachandar2016) with a combination of various threshold values for the isosurfaces of density,

![]() $\rho _{\textit{th}}$

, and the threshold height value,

$\rho _{\textit{th}}$

, and the threshold height value,

![]() $h_{\textit{th}}$

, to determine the optimal criteria for defining the head of the current. In the present study,

$h_{\textit{th}}$

, to determine the optimal criteria for defining the head of the current. In the present study,

![]() $\rho _{\textit{th}} = 0.015$

and

$\rho _{\textit{th}} = 0.015$

and

![]() $h_{\textit{th}}=0.3$

are selected based on the sensitivity analysis documented in Appendix A. It is important to note that

$h_{\textit{th}}=0.3$

are selected based on the sensitivity analysis documented in Appendix A. It is important to note that

![]() $\rho _{\textit{th}}$

represents a density or concentration level that captures the profile of the gravity current. This profile includes both the unmixed and surrounding mixed regions.

$\rho _{\textit{th}}$

represents a density or concentration level that captures the profile of the gravity current. This profile includes both the unmixed and surrounding mixed regions.

Figure 2. Methodological framework for determining the head of the gravity current.

3.2. Density analysis

In contrast to the previous method, the 3-D indicator function is not explicitly required in this analysis, as the integration bounds are chosen to encompass the entire gravity current. The cumulative mass of the gravity current along the streamwise direction is determined by integrating the local equivalent height of the current,

![]() $\tilde {h}(x,y,t)$

, over the spanwise and streamwise directions. The local equivalent height of the current is defined as

$\tilde {h}(x,y,t)$

, over the spanwise and streamwise directions. The local equivalent height of the current is defined as

The cumulative mass of the gravity current along the streamwise direction is then given by

where

![]() $\tilde {x}=x_f+0.5L_z$

is an arbitrary chosen position sufficiently downstream of the gravity current front

$\tilde {x}=x_f+0.5L_z$

is an arbitrary chosen position sufficiently downstream of the gravity current front

![]() $x_f$

. This ensures that the integration bounds fully encompass the entire current without requiring an explicit indicator function. Figure 3

$x_f$

. This ensures that the integration bounds fully encompass the entire current without requiring an explicit indicator function. Figure 3

![]() $(a)$

illustrates the cumulative mass,

$(a)$

illustrates the cumulative mass,

![]() $M(x,t=10)$

, along the streamwise direction. At

$M(x,t=10)$

, along the streamwise direction. At

![]() $x=0$

, the cumulative mass equals the initial mass of the released heavy fluid,

$x=0$

, the cumulative mass equals the initial mass of the released heavy fluid,

![]() $M(x=0,t) = M(x=0, t=0)=x_0H\rho _c = 1.333$

. This confirms that mass is conserved using this approach. Note that

$M(x=0,t) = M(x=0, t=0)=x_0H\rho _c = 1.333$

. This confirms that mass is conserved using this approach. Note that

![]() $\overline {h}$

can be thought to be the effective height of the current assuming no mixing has occurred. Figure 3

$\overline {h}$

can be thought to be the effective height of the current assuming no mixing has occurred. Figure 3

![]() $(b)$

shows the spanwise-averaged 2-D density contour of the gravity current with

$(b)$

shows the spanwise-averaged 2-D density contour of the gravity current with

![]() $k_y=0$

at

$k_y=0$

at

![]() $t=10$

. The equivalent height,

$t=10$

. The equivalent height,

![]() $\overline {h}$

, is overlaid as the red dashed line. The tail of the current is identified by determining the location where the mass flux reaches zero, as shown in figure 3

$\overline {h}$

, is overlaid as the red dashed line. The tail of the current is identified by determining the location where the mass flux reaches zero, as shown in figure 3

![]() $(c)$

.

$(c)$

.

Figure 3.

![]() $(a)$

Streamwise profiles of the spanwise-averaged equivalent height

$(a)$

Streamwise profiles of the spanwise-averaged equivalent height

![]() $\overline {h}$

and cumulative mass

$\overline {h}$

and cumulative mass

![]() $M$

.

$M$

.

![]() $(b)$

The 2-D density contour at

$(b)$

The 2-D density contour at

![]() $t=10$

, with the red dashed line indicating

$t=10$

, with the red dashed line indicating

![]() $\overline {h}$

. In

$\overline {h}$

. In

![]() $(a)$

, the solid blue line represents the cumulative mass along the streamwise direction. The white dashed line in

$(a)$

, the solid blue line represents the cumulative mass along the streamwise direction. The white dashed line in

![]() $(b)$

highlights the head region as identified by the indicator function, and the black cross marks the location where

$(b)$

highlights the head region as identified by the indicator function, and the black cross marks the location where

![]() $h_{\textit{th}} = 0.3$

.

$h_{\textit{th}} = 0.3$

.

![]() $(c)$

Mass flux of the current along the streamwise direction, where the vertical red solid line indicates the location of zero mass flux.

$(c)$

Mass flux of the current along the streamwise direction, where the vertical red solid line indicates the location of zero mass flux.

The volume of a gravity current can be obtained by integrating its profile,

![]() $\rho _{\textit{th}}=0.015$

, along the streamwise direction and is defined as

$\rho _{\textit{th}}=0.015$

, along the streamwise direction and is defined as

It is important to note that integrating the profile represents the extent of the boundary and does not directly yield density values. The density of the gravity current is subsequently defined as

Here, the density of the gravity current is denoted by

![]() $\varrho$

to avoid confusion with the density of the fluid,

$\varrho$

to avoid confusion with the density of the fluid,

![]() $\rho$

.

$\rho$

.

3.3. Local statistics

Previous methodologies effectively captured the density of the gravity currents for predicting their mixing behaviour with varying spanwise perturbation. To further investigate the underlying mixing mechanisms, we computed the ‘local’ stirring and mixing components, as well as the mixing efficiency, within both the head and body of the gravity current.

The mechanical energy framework discussed by Winters et al. (Reference Winters, Lombard, Riley and D’Asaro1995) provides a foundation for understanding the ‘global’ energy exchanges in stratified flows. In this framework, the potential energy can be decomposed into two components: available potential energy

![]() $E_a$

and background potential energy

$E_a$

and background potential energy

![]() $E_b$

(also referred to as the minimum potential energy), such that

$E_b$

(also referred to as the minimum potential energy), such that

![]() $E_p=E_a+E_b$

. The available potential energy represents the portion of

$E_p=E_a+E_b$

. The available potential energy represents the portion of

![]() $E_p$

that can be converted into kinetic energy (and vice versa) for motion, whereas the background potential energy increases as a result of irreversible mixing or molecular diffusion (Winters et al. Reference Winters, Lombard, Riley and D’Asaro1995; Peltier & Caulfield Reference Peltier and Caulfield2003; Winters & Barkan Reference Winters and Barkan2013; Ottolenghi et al. Reference Ottolenghi, Adduce, Inghilesi, Armenio and Roman2016a

; Lam et al. Reference Lam, Chan, Cao, Sutherland, Manasseh, Moinuddin and Ooi2024b

). These components are commonly used to distinguish between the ‘stirring’ and ‘mixing’ processes. ‘Stirring’ refers to reversible changes associated with large-scale motion, while ‘mixing’ denotes irreversible changes that involve motions that extend to the smallest scales (Caulfield & Peltier Reference Caulfield and Peltier2000; Peltier & Caulfield Reference Peltier and Caulfield2003; Ottolenghi et al. Reference Ottolenghi, Adduce, Inghilesi, Armenio and Roman2016a

). This study adopts and extends this framework beyond the ‘global’ analysis to investigate ‘local’ energy exchanges.

$E_p$

that can be converted into kinetic energy (and vice versa) for motion, whereas the background potential energy increases as a result of irreversible mixing or molecular diffusion (Winters et al. Reference Winters, Lombard, Riley and D’Asaro1995; Peltier & Caulfield Reference Peltier and Caulfield2003; Winters & Barkan Reference Winters and Barkan2013; Ottolenghi et al. Reference Ottolenghi, Adduce, Inghilesi, Armenio and Roman2016a

; Lam et al. Reference Lam, Chan, Cao, Sutherland, Manasseh, Moinuddin and Ooi2024b

). These components are commonly used to distinguish between the ‘stirring’ and ‘mixing’ processes. ‘Stirring’ refers to reversible changes associated with large-scale motion, while ‘mixing’ denotes irreversible changes that involve motions that extend to the smallest scales (Caulfield & Peltier Reference Caulfield and Peltier2000; Peltier & Caulfield Reference Peltier and Caulfield2003; Ottolenghi et al. Reference Ottolenghi, Adduce, Inghilesi, Armenio and Roman2016a

). This study adopts and extends this framework beyond the ‘global’ analysis to investigate ‘local’ energy exchanges.

As shown by Winters et al. (Reference Winters, Lombard, Riley and D’Asaro1995), the rate of change of potential energy is given by

\begin{align} {\frac {{\rm d}E_p}{{\rm d}t}=-\int _{S} z\rho \boldsymbol{u \boldsymbol{\cdot }n}\ {\rm d}S + \underbrace {\int _{\varOmega } \rho w\ {\rm d}V}_{\text{$\varPhi _z$}} + \frac {1}{\textit{Re}\textit{Sc}} \int _{S} z \boldsymbol{\nabla }\rho \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{n}\ {\rm d}S - \underbrace {\frac {1}{\textit{Re}\textit{Sc}} \int _{\varOmega }\frac {\partial \rho }{\partial z} \ {\rm d}V}_{{\varPhi _i}} \,,} \end{align}

\begin{align} {\frac {{\rm d}E_p}{{\rm d}t}=-\int _{S} z\rho \boldsymbol{u \boldsymbol{\cdot }n}\ {\rm d}S + \underbrace {\int _{\varOmega } \rho w\ {\rm d}V}_{\text{$\varPhi _z$}} + \frac {1}{\textit{Re}\textit{Sc}} \int _{S} z \boldsymbol{\nabla }\rho \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{n}\ {\rm d}S - \underbrace {\frac {1}{\textit{Re}\textit{Sc}} \int _{\varOmega }\frac {\partial \rho }{\partial z} \ {\rm d}V}_{{\varPhi _i}} \,,} \end{align}

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{n}$

is the unit normal vector to the surface

$\boldsymbol{n}$

is the unit normal vector to the surface

![]() $S$

bounding the domain

$S$

bounding the domain

![]() $\varOmega$

, and

$\varOmega$

, and

![]() $\tau$

is the time integration variable. In a closed system, where surface fluxes vanish, the evolution of the potential energy components (

$\tau$

is the time integration variable. In a closed system, where surface fluxes vanish, the evolution of the potential energy components (

![]() ${\rm d}E_p/{\rm d}t = {\rm d}E_a/{\rm d}t + {\rm d}E_b/{\rm d}t)$

simplifies to

${\rm d}E_p/{\rm d}t = {\rm d}E_a/{\rm d}t + {\rm d}E_b/{\rm d}t)$

simplifies to

where

![]() $\varPhi _z$

is the buoyancy flux,

$\varPhi _z$

is the buoyancy flux,

![]() $\varPhi _d$

represents the rate of change of

$\varPhi _d$

represents the rate of change of

![]() $E_b$

due to material changes in density within the domain or irreversible fluid mixing and

$E_b$

due to material changes in density within the domain or irreversible fluid mixing and

![]() $\varPhi _i$

denotes irreversible diffusion. These expressions apply to global analyses in closed systems (Winters et al. Reference Winters, Lombard, Riley and D’Asaro1995). However, to quantify local irreversible mixing, surface flux contributions must be explicitly retained. For clarity, we distinguish between global and local quantities using the notations

$\varPhi _i$

denotes irreversible diffusion. These expressions apply to global analyses in closed systems (Winters et al. Reference Winters, Lombard, Riley and D’Asaro1995). However, to quantify local irreversible mixing, surface flux contributions must be explicitly retained. For clarity, we distinguish between global and local quantities using the notations

![]() $E_{\xi }$

and

$E_{\xi }$

and

![]() $\mathscr{E}_{\xi }$

, respectively, where

$\mathscr{E}_{\xi }$

, respectively, where

![]() $\xi \in \{p, a, b\}$

refers to potential energy, available potential energy and background potential energy.

$\xi \in \{p, a, b\}$

refers to potential energy, available potential energy and background potential energy.

The local rate of change of potential energy,

![]() $\partial \mathscr{E}_p(\boldsymbol{x},t)/ \partial t$

(with

$\partial \mathscr{E}_p(\boldsymbol{x},t)/ \partial t$

(with

![]() $\boldsymbol{x} = (x, y, z)$

), retaining all surface flux components, is expressed as

$\boldsymbol{x} = (x, y, z)$

), retaining all surface flux components, is expressed as

By performing a volume integration over the domain

![]() $\varOmega$

, the divergence terms (first and third on the right-hand side of (3.9)) vanish, and the volume-integrated form recovers the global rate of change of potential energy in a closed system, i.e.

$\varOmega$

, the divergence terms (first and third on the right-hand side of (3.9)) vanish, and the volume-integrated form recovers the global rate of change of potential energy in a closed system, i.e.

![]() $\int _{\varOmega } \partial \mathscr{E}_p/\partial t\ {\rm d}V \rightarrow {\rm d}E_p/{\rm d}t = \varPhi _z + \varPhi _i$

.

$\int _{\varOmega } \partial \mathscr{E}_p/\partial t\ {\rm d}V \rightarrow {\rm d}E_p/{\rm d}t = \varPhi _z + \varPhi _i$

.

Hence, we compute

i.e. the local rate of irreversible fluid mixing is the difference between the local rates of potential energy and available potential energy. The local rate

![]() $\partial \mathscr{E}_b(\boldsymbol{x},t)/ \partial t = \tilde {z}(-\boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }\rho + \boldsymbol{\nabla} ^2 \rho /(\textit{Re}\textit{Sc}))$

(where

$\partial \mathscr{E}_b(\boldsymbol{x},t)/ \partial t = \tilde {z}(-\boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }\rho + \boldsymbol{\nabla} ^2 \rho /(\textit{Re}\textit{Sc}))$

(where

![]() $\tilde {z}$

is the equilibrium position of the fluid parcel at the adiabatically rearranged to the minimum potential energy state) has been validated against a 2-D simulation and shown to be consistent with the right-hand side of (3.10).

$\tilde {z}$

is the equilibrium position of the fluid parcel at the adiabatically rearranged to the minimum potential energy state) has been validated against a 2-D simulation and shown to be consistent with the right-hand side of (3.10).

The ‘local’ available potential energy,

![]() $\mathscr{E}_a$

, also referred to as the available potential energy density by Winters & Barkan (Reference Winters and Barkan2013), represents the spatial mapping of local contributions to global

$\mathscr{E}_a$

, also referred to as the available potential energy density by Winters & Barkan (Reference Winters and Barkan2013), represents the spatial mapping of local contributions to global

![]() $E_a$

. It links local energy exchange to the stirring process and is defined as

$E_a$

. It links local energy exchange to the stirring process and is defined as

The rearrangement process, in which a fluid parcel is relocated from

![]() $z_i$

to

$z_i$

to

![]() $\tilde {z}_i$

, is detailed in Winters & Barkan (Reference Winters and Barkan2013) and has been applied in recent studies (Ottolenghi et al. Reference Ottolenghi, Adduce, Inghilesi, Armenio and Roman2016a

; Lam et al. Reference Lam, Chan, Cao, Sutherland, Manasseh, Moinuddin and Ooi2024a

,Reference Lam, Chan, Cao, Sutherland, Manasseh, Moinuddin and Ooi

b

). This sorting procedure is central to transform the 3-D density field

$\tilde {z}_i$

, is detailed in Winters & Barkan (Reference Winters and Barkan2013) and has been applied in recent studies (Ottolenghi et al. Reference Ottolenghi, Adduce, Inghilesi, Armenio and Roman2016a

; Lam et al. Reference Lam, Chan, Cao, Sutherland, Manasseh, Moinuddin and Ooi2024a

,Reference Lam, Chan, Cao, Sutherland, Manasseh, Moinuddin and Ooi

b

). This sorting procedure is central to transform the 3-D density field

![]() $\rho (\boldsymbol{x})$

at a given time

$\rho (\boldsymbol{x})$

at a given time

![]() $t$

into a 1-D reference density profile.

$t$

into a 1-D reference density profile.

It is important to emphasise that the available potential energy density

![]() $\mathscr{E}_a$

is not a direct measure of local mixing, as stirring may not necessarily result in irreversible changes. The local rate of change of available potential energy,

$\mathscr{E}_a$

is not a direct measure of local mixing, as stirring may not necessarily result in irreversible changes. The local rate of change of available potential energy,

![]() $\partial \mathscr{E}_a(\boldsymbol{x},t) /\partial t$

, is computed by differentiating

$\partial \mathscr{E}_a(\boldsymbol{x},t) /\partial t$

, is computed by differentiating

![]() $\mathscr{E}_a(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

with respect to time. Substituting this result, along with

$\mathscr{E}_a(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

with respect to time. Substituting this result, along with

![]() $\partial \mathscr{E}_p(\boldsymbol{x},t) /\partial t$

from (3.9), into (3.10) yields the local rate of irreversible fluid mixing,

$\partial \mathscr{E}_p(\boldsymbol{x},t) /\partial t$

from (3.9), into (3.10) yields the local rate of irreversible fluid mixing,

![]() $\partial \mathscr{E}_b(\boldsymbol{x},t) /\partial t$

. In this study, we interpret

$\partial \mathscr{E}_b(\boldsymbol{x},t) /\partial t$

. In this study, we interpret

![]() $\mathscr{E}_a(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

as a measure of local stirring, while

$\mathscr{E}_a(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

as a measure of local stirring, while

![]() $\partial \mathscr{E}_b(\boldsymbol{x},t)/{\rm d}t$

quantifies the local mixing rate. It is important to note that

$\partial \mathscr{E}_b(\boldsymbol{x},t)/{\rm d}t$

quantifies the local mixing rate. It is important to note that

![]() $\partial \mathscr{E}_b(\boldsymbol{x},t)/{\rm d}t$

contains both positive and negative local values. Positive regions correspond to irreversible mixing associated with molecular diffusion, whereas negative regions arise from advective and diffusive redistribution of density. When integrated over the entire domain (i.e. in a closed system), the advective and diffusive fluxes vanish, such that

$\partial \mathscr{E}_b(\boldsymbol{x},t)/{\rm d}t$

contains both positive and negative local values. Positive regions correspond to irreversible mixing associated with molecular diffusion, whereas negative regions arise from advective and diffusive redistribution of density. When integrated over the entire domain (i.e. in a closed system), the advective and diffusive fluxes vanish, such that

consistent with Winters et al. (Reference Winters, Lombard, Riley and D’Asaro1995), Ottolenghi et al. (Reference Ottolenghi, Adduce, Inghilesi, Armenio and Roman2016a

) and Lam et al. (Reference Lam, Chan, Cao, Sutherland, Manasseh, Moinuddin and Ooi2024b

). For clarity, only the positive regions of

![]() $\partial \mathscr{E}_b(\boldsymbol{x},t)/{\rm d}t$

are visualised in the isosurfaces plot, as these represent locations of effective irreversible mixing.

$\partial \mathscr{E}_b(\boldsymbol{x},t)/{\rm d}t$

are visualised in the isosurfaces plot, as these represent locations of effective irreversible mixing.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Visualisation of gravity current

4.1.1. Equivalent height

Before examining the propagation in detail, we first analyse the equivalent height and density contours of the gravity current for cases with different

![]() $k_y$

values at

$k_y$

values at

![]() $ \textit{Re}=3450$

and 10 000 focusing on the slumping phase, the most persistent and dynamic stage of the flow evolution. The spanwise-averaged equivalent height of the current in the wall-normal direction (

$ \textit{Re}=3450$

and 10 000 focusing on the slumping phase, the most persistent and dynamic stage of the flow evolution. The spanwise-averaged equivalent height of the current in the wall-normal direction (

![]() $z$

) is defined as

$z$

) is defined as

The temporal evolution of the gravity current dynamics, visualised using spanwise-averaged density contours, is shown in figure 4. The equivalent height of the current,

![]() $\overline {h}$

, is highlighted by the white dashed line. The case with

$\overline {h}$

, is highlighted by the white dashed line. The case with

![]() $k_y=0$

is plotted on the left-hand side, while

$k_y=0$

is plotted on the left-hand side, while

![]() $k_y=2$

is on the right-hand side. These cases were selected to illustrate the disruption of K–H billow formation. During the early times (

$k_y=2$

is on the right-hand side. These cases were selected to illustrate the disruption of K–H billow formation. During the early times (

![]() $t \leqslant 5$

), no significant differences are observed in the overall shape of the current. At

$t \leqslant 5$

), no significant differences are observed in the overall shape of the current. At

![]() $t=5$

, during the slumping phase, the K–H billows begin to develop behind the head of the current. For the

$t=5$

, during the slumping phase, the K–H billows begin to develop behind the head of the current. For the

![]() $k_y=2$

case, these billows begin to diffuse due to spanwise disturbance introduced by the initial perturbation, whereas in the

$k_y=2$

case, these billows begin to diffuse due to spanwise disturbance introduced by the initial perturbation, whereas in the

![]() $k_y=0$

case, the outlines of the billows remains smooth, as indicated by the solid red arrows.

$k_y=0$

case, the outlines of the billows remains smooth, as indicated by the solid red arrows.

Figure 4. Spanwise-averaged density contour of the gravity current at

![]() $ \textit{Re}=3450$

with

$ \textit{Re}=3450$

with

![]() $k_y=0$

(left column) and

$k_y=0$

(left column) and

![]() $k_y=2$

(right column). The white dashed line shows the equivalent height of the gravity current (

$k_y=2$

(right column). The white dashed line shows the equivalent height of the gravity current (

![]() $\overline {h}$

). The red arrows highlight the outline differences of K–H billows between

$\overline {h}$

). The red arrows highlight the outline differences of K–H billows between

![]() $k_y=0$

and

$k_y=0$

and

![]() $k_y=2$

.

$k_y=2$

.

At

![]() $t \approx 10$

, the gravity current begins transition into the inertial phase, the shape and

$t \approx 10$

, the gravity current begins transition into the inertial phase, the shape and

![]() $\overline {h}$

of the current differ significantly. Although the heads of both cases appear similar, a layer of ambient fluid enters and mixes with the head due to high shear and the no-slip bottom boundary condition. The K–H billows in the

$\overline {h}$

of the current differ significantly. Although the heads of both cases appear similar, a layer of ambient fluid enters and mixes with the head due to high shear and the no-slip bottom boundary condition. The K–H billows in the

![]() $k_y=2$

case have disintegrated, whereas the billows in the

$k_y=2$

case have disintegrated, whereas the billows in the

![]() $k_y=0$

case maintain a distinct vortex core structure. The equivalent height,

$k_y=0$

case maintain a distinct vortex core structure. The equivalent height,

![]() $\overline {h}$

, behind the head (

$\overline {h}$

, behind the head (

![]() $1 \leqslant x \leqslant 4$

) for the

$1 \leqslant x \leqslant 4$

) for the

![]() $k_y=2$

case is significantly lower than that of

$k_y=2$

case is significantly lower than that of

![]() $k_y=0$

, attributed to the reduced density from the breakdown of the billows caused by spanwise disturbances. At later times (

$k_y=0$

, attributed to the reduced density from the breakdown of the billows caused by spanwise disturbances. At later times (

![]() $t\gt 15$

), the equivalent height for the

$t\gt 15$

), the equivalent height for the

![]() $k_y=2$

case has a smooth profile with the formation of ‘finger’ structures behind the current. In contrast, the

$k_y=2$

case has a smooth profile with the formation of ‘finger’ structures behind the current. In contrast, the

![]() $k_y=0$

case continues to exhibit K–H billows behind the head, with the profile of

$k_y=0$

case continues to exhibit K–H billows behind the head, with the profile of

![]() $\overline {h}$

containing pronounced undulations.

$\overline {h}$

containing pronounced undulations.

4.1.2. Turbulent structures

Figures 5–7 depict the temporal evolution of the turbulent structures for different

![]() $k_y$

cases at

$k_y$

cases at

![]() $ \textit{Re}=3450$

. The

$ \textit{Re}=3450$

. The

![]() $\lambda _2$

vortex identification criterion, introduced by Jeong & Hussain (Reference Jeong and Hussain1995), is used to visualise the vortical structures in gravity currents under different initial perturbations. The isosurfaces of density (

$\lambda _2$

vortex identification criterion, introduced by Jeong & Hussain (Reference Jeong and Hussain1995), is used to visualise the vortical structures in gravity currents under different initial perturbations. The isosurfaces of density (

![]() $\rho =0.015$

) are plotted alongside of isosurfaces of

$\rho =0.015$

) are plotted alongside of isosurfaces of

![]() $\lambda _2$

which are coloured by the spanwise vorticity,

$\lambda _2$

which are coloured by the spanwise vorticity,

![]() $\omega _y$

. To complement this, the spanwise-averaged density contour is shown adjacent to the isosurfaces, providing a clearer visualisation of the breakdown of turbulent structures caused by spanwise disturbances.

$\omega _y$

. To complement this, the spanwise-averaged density contour is shown adjacent to the isosurfaces, providing a clearer visualisation of the breakdown of turbulent structures caused by spanwise disturbances.

Figure 5. Isosurfaces of density (

![]() $\rho =0.015$

) plotted on top of isosurfaces of

$\rho =0.015$

) plotted on top of isosurfaces of

![]() $\lambda _2 = -0.5$

for the

$\lambda _2 = -0.5$

for the

![]() $ \textit{Re}=3450$

case with

$ \textit{Re}=3450$

case with

![]() $k_y=0$

and

$k_y=0$

and

![]() $\lambda _2=-2$

for other

$\lambda _2=-2$

for other

![]() $k_y$

cases at

$k_y$

cases at

![]() $t=6$

during the slumping phase. Isosurfaces of

$t=6$

during the slumping phase. Isosurfaces of

![]() $\lambda _2$

are coloured by the spanwise vorticity,

$\lambda _2$

are coloured by the spanwise vorticity,

![]() $\omega _y$

. The spanwise-averaged density is displayed adjacent to the isosurfaces.

$\omega _y$

. The spanwise-averaged density is displayed adjacent to the isosurfaces.

Figure 6. Isosurfaces of density (

![]() $\rho =0.015$

) plotted on top of isosurfaces of

$\rho =0.015$

) plotted on top of isosurfaces of

![]() $\lambda _2 = -0.5$

for the

$\lambda _2 = -0.5$

for the

![]() $ \textit{Re}=3450$

case with

$ \textit{Re}=3450$

case with

![]() $k_y=0$

and

$k_y=0$

and

![]() $\lambda _2=-2$

for other

$\lambda _2=-2$

for other

![]() $k_y$

cases at

$k_y$

cases at

![]() $t=10$

during the post-slumping phase. Isosurfaces of

$t=10$

during the post-slumping phase. Isosurfaces of

![]() $\lambda _2$

are coloured by the spanwise vorticity,

$\lambda _2$

are coloured by the spanwise vorticity,

![]() $\omega _y$

. The spanwise-averaged density is displayed adjacent to the isosurfaces.

$\omega _y$

. The spanwise-averaged density is displayed adjacent to the isosurfaces.

Figure 7. Isosurfaces of density (

![]() $\rho =0.015$

) plotted on top of isosurfaces of

$\rho =0.015$

) plotted on top of isosurfaces of

![]() $\lambda _2 = -0.5$

for the

$\lambda _2 = -0.5$

for the

![]() $ \textit{Re}=3450$

case with

$ \textit{Re}=3450$

case with

![]() $k_y=0$

and

$k_y=0$

and

![]() $\lambda _2=-2$

for other

$\lambda _2=-2$

for other

![]() $k_y$

cases at

$k_y$

cases at

![]() $t=20$

during the inertial phase. Isosurfaces of

$t=20$

during the inertial phase. Isosurfaces of

![]() $\lambda _2$

are coloured by the spanwise vorticity,

$\lambda _2$

are coloured by the spanwise vorticity,

![]() $\omega _y$

. The spanwise-averaged density is displayed adjacent to the isosurfaces. All figures are plotted focusing only on the head and body of the current.

$\omega _y$

. The spanwise-averaged density is displayed adjacent to the isosurfaces. All figures are plotted focusing only on the head and body of the current.

During the slumping phase (

![]() $t=6$

), the structures for the

$t=6$

), the structures for the

![]() $k_y=0$

remain coherent along the spanwise direction, with the K–H billows developing behind the head of the current, as shown in figure 5

$k_y=0$

remain coherent along the spanwise direction, with the K–H billows developing behind the head of the current, as shown in figure 5

![]() $(a)$

. In contrast, for the

$(a)$

. In contrast, for the

![]() $k_y=2$

case, the structures behind the head have already started to break down. In particular, the number of spanwise vortices corresponds to the imposed

$k_y=2$

case, the structures behind the head have already started to break down. In particular, the number of spanwise vortices corresponds to the imposed

![]() $k_y$

at

$k_y$

at

![]() $t=0$

, indicating the evolution of initial spanwise perturbations (see movie 1 with the online version of the paper). Interestingly, as

$t=0$

, indicating the evolution of initial spanwise perturbations (see movie 1 with the online version of the paper). Interestingly, as

![]() $k_y$

increases to 4 and 8 (refer to figures 5

$k_y$

increases to 4 and 8 (refer to figures 5

![]() $c$

and 5

$c$

and 5

![]() $d$

), the breakdown of the structures is less pronounced compared with the

$d$

), the breakdown of the structures is less pronounced compared with the

![]() $k_y=2$

case. This is evident in the spanwise-averaged density contour, where the K–H billows are distinctly visible in the

$k_y=2$

case. This is evident in the spanwise-averaged density contour, where the K–H billows are distinctly visible in the

![]() $k_y=0,4$

and 8 cases, but appear more diffuse and less defined in the

$k_y=0,4$

and 8 cases, but appear more diffuse and less defined in the

![]() $k_y=2$

case, as shown in figure 5

$k_y=2$

case, as shown in figure 5

![]() $(b)$

.

$(b)$

.

At

![]() $t=10$

and 20, when the gravity current transitions into the inertial phase, the structures for the

$t=10$

and 20, when the gravity current transitions into the inertial phase, the structures for the

![]() $k_y=0$

case remain coherent and appear to be two-dimensional. In contrast, the structures in the

$k_y=0$

case remain coherent and appear to be two-dimensional. In contrast, the structures in the

![]() $k_y=2,4$

and 8 cases have undergone significant breakdown, as evidenced by the presence of filaments extending in the streamwise direction. The structures for the cases with

$k_y=2,4$

and 8 cases have undergone significant breakdown, as evidenced by the presence of filaments extending in the streamwise direction. The structures for the cases with

![]() $k_y=8$

and 4 appear periodic along the

$k_y=8$

and 4 appear periodic along the

![]() $y$

- direction. During this phase, the evolution of the initial spanwise perturbations persists, with the spanwise structures reflecting the initial imposed number of repeating waves in the spanwise direction. Interestingly, the K–H billows observed in the spanwise-averaged density contour for the

$y$

- direction. During this phase, the evolution of the initial spanwise perturbations persists, with the spanwise structures reflecting the initial imposed number of repeating waves in the spanwise direction. Interestingly, the K–H billows observed in the spanwise-averaged density contour for the

![]() $k_y=8$

case resemble those in the

$k_y=8$

case resemble those in the

![]() $k_y=0$

case. At

$k_y=0$

case. At

![]() $t=20$

(see figure 7), the density of the current head for the

$t=20$

(see figure 7), the density of the current head for the

![]() $k_y=0$

case is significantly lower than that of all other cases, followed by the

$k_y=0$

case is significantly lower than that of all other cases, followed by the

![]() $k_y=8$

case. This suggests that the

$k_y=8$

case. This suggests that the

![]() $k_y=0$

and 8 cases exhibit better mixing than the

$k_y=0$

and 8 cases exhibit better mixing than the

![]() $k_y=2$

and 4 cases.

$k_y=2$

and 4 cases.

Figures 8 and 9 illustrate the temporal evolution of the turbulent structures for different

![]() $k_y$

cases at

$k_y$

cases at

![]() $ \textit{Re}=10\,000$

. A half-width isosurfaces of density is plotted alongside the isosurfaces of

$ \textit{Re}=10\,000$

. A half-width isosurfaces of density is plotted alongside the isosurfaces of

![]() $\lambda _2$

, which are coloured by the spanwise vorticity,

$\lambda _2$

, which are coloured by the spanwise vorticity,

![]() $\omega _y$

. The spanwise-averaged density contour is shown adjacent to the isosurfaces, providing a clearer visualisation of the breakdown of turbulent structures.

$\omega _y$

. The spanwise-averaged density contour is shown adjacent to the isosurfaces, providing a clearer visualisation of the breakdown of turbulent structures.

Figure 8. A half-width isosurfaces of density (

![]() $\rho =0.015$

) plotted on top of isosurfaces of

$\rho =0.015$

) plotted on top of isosurfaces of

![]() $\lambda _2 = -0.5$

for the

$\lambda _2 = -0.5$

for the

![]() $ \textit{Re}=10\,000$

case with

$ \textit{Re}=10\,000$

case with

![]() $k_y=0$

and

$k_y=0$

and

![]() $\lambda _2=-2$

for other

$\lambda _2=-2$

for other

![]() $k_y$

cases at

$k_y$

cases at

![]() $t=6$

during the slumping phase. Isosurfaces of

$t=6$

during the slumping phase. Isosurfaces of

![]() $\lambda _2$

are coloured by the spanwise vorticity,

$\lambda _2$

are coloured by the spanwise vorticity,

![]() $\omega _y$

. The spanwise-averaged density is displayed adjacent to the isosurfaces.

$\omega _y$

. The spanwise-averaged density is displayed adjacent to the isosurfaces.

Figure 9. A half-width isosurfaces of density (

![]() $\rho =0.015$

) plotted on top of isosurfaces of

$\rho =0.015$

) plotted on top of isosurfaces of

![]() $\lambda _2 = -0.5$

for the

$\lambda _2 = -0.5$

for the

![]() $ \textit{Re}=10\,000$

case with

$ \textit{Re}=10\,000$

case with

![]() $k_y=0$

and

$k_y=0$

and

![]() $\lambda _2=-2$

for other

$\lambda _2=-2$

for other

![]() $k_y$

cases at

$k_y$

cases at

![]() $t=20$

during the inertial phase. Isosurfaces of

$t=20$

during the inertial phase. Isosurfaces of

![]() $\lambda _2$

are coloured by the spanwise vorticity,

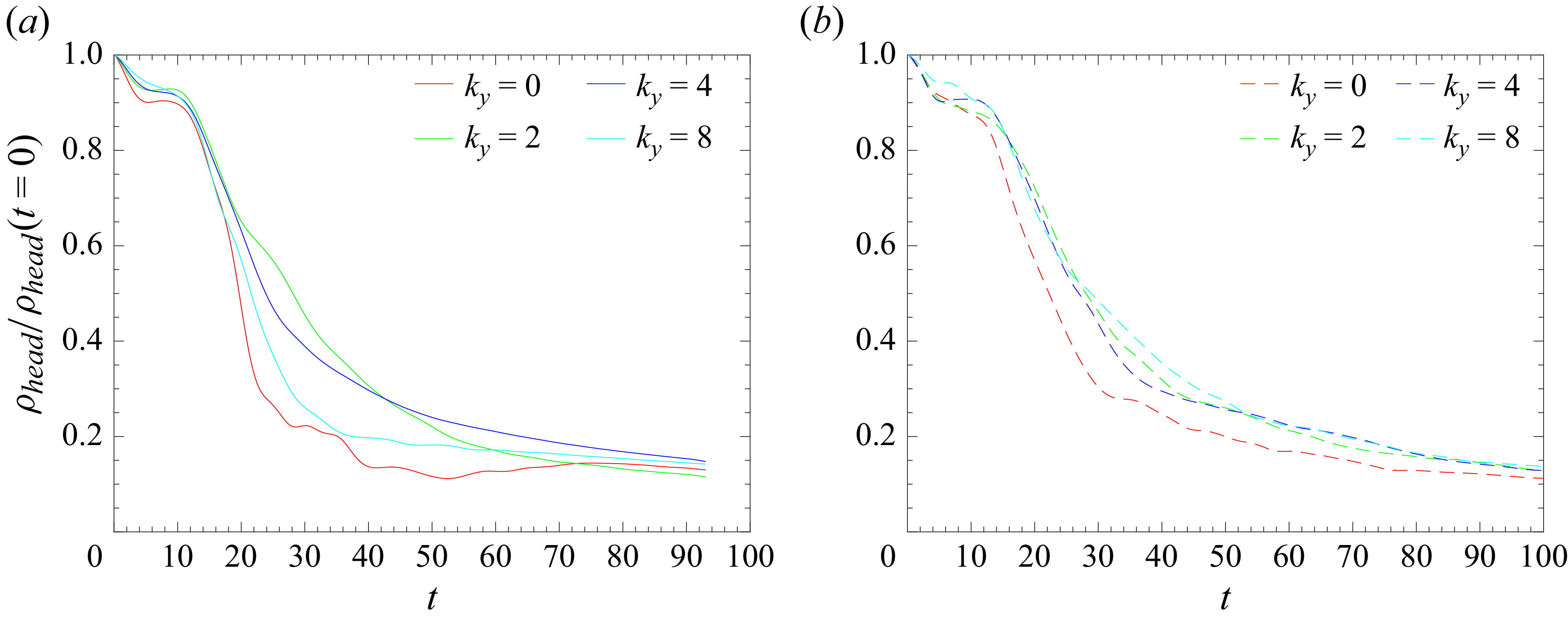

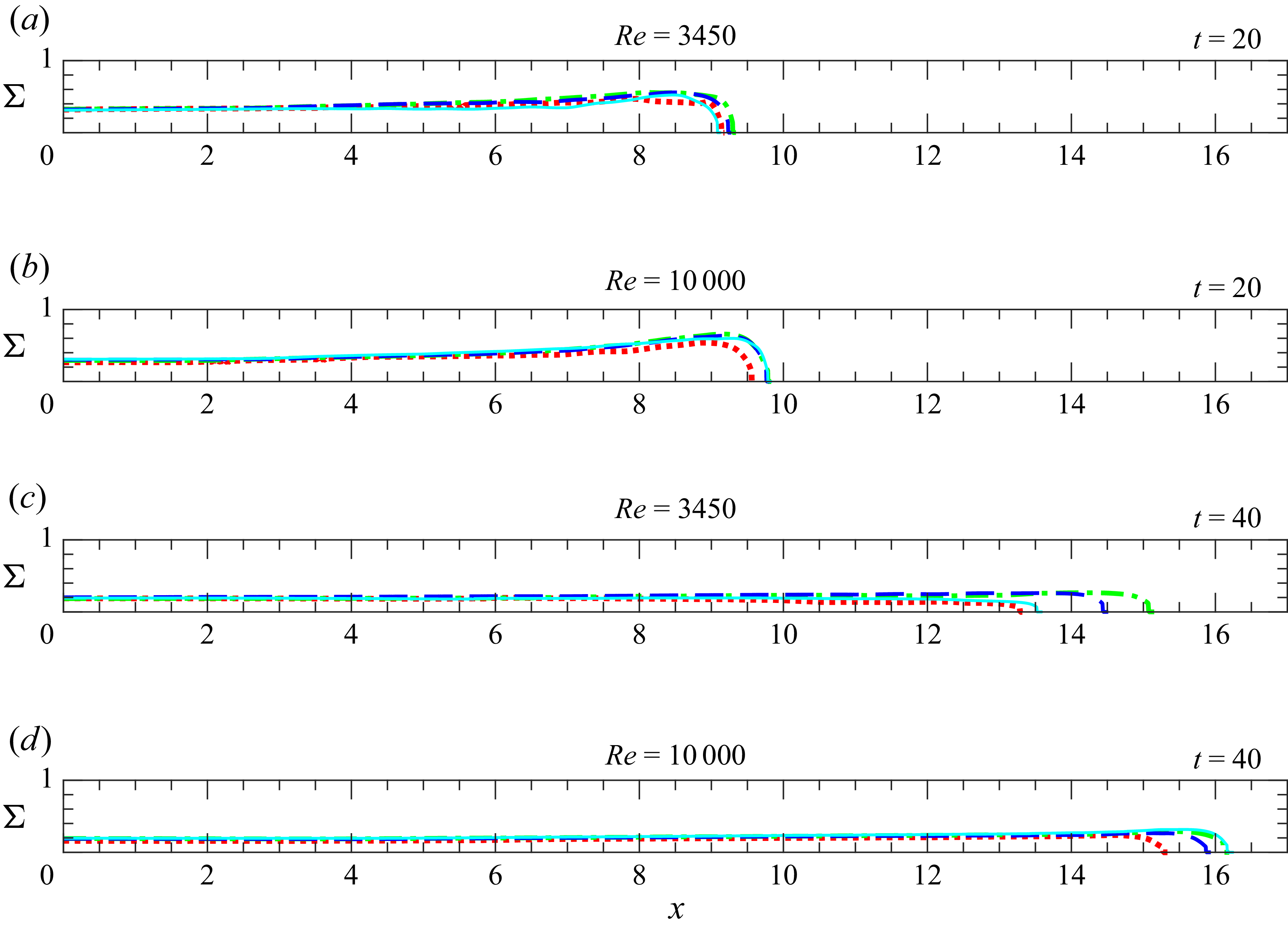

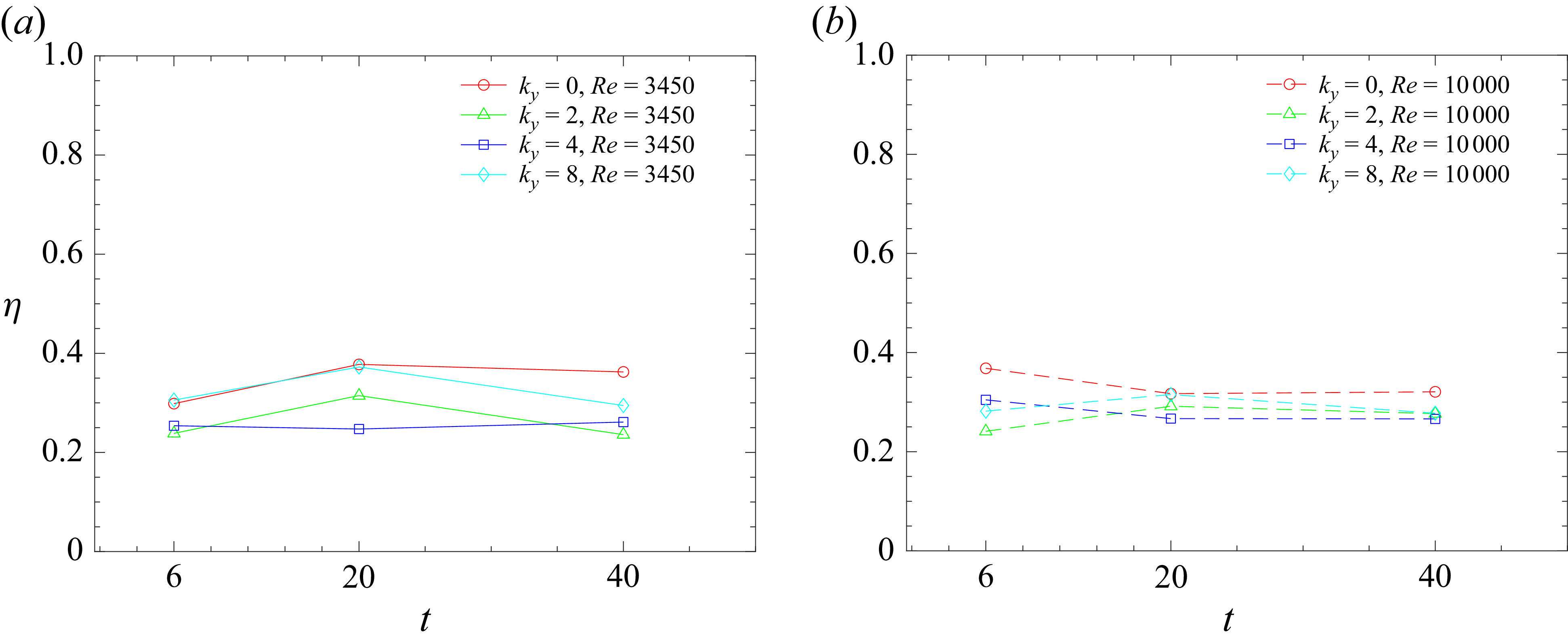

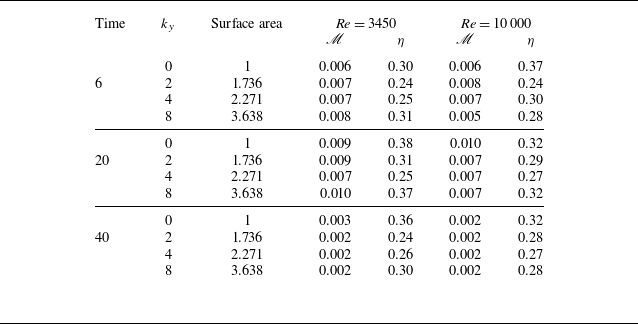

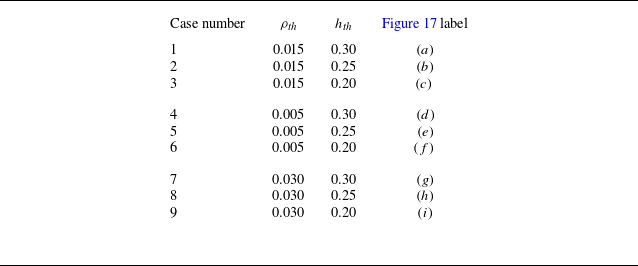

$\lambda _2$