1. Introduction

Because of the transboundary nature of aviation, states have recognized the need for the international harmonization of the norms relating to international aviation and undertook to comply with the rules of international law with regard to international aviation. On a global level, there are a dozen aviation-specific multilateral treaties,Footnote 1 some of which enjoy virtually universal ratifications. Indeed, the regulatory framework of international aviation consists of a combination of multilateral conventions and bilateral air services agreements (ASAs).Footnote 2 To be sure, there are technical regulations formulated by ICAO, such as SARPs (the focus of this article), Procedures for Air Navigation Services (PANS), Regional Supplementary Procedures (SUPPS), regional air navigation plans and related manuals, circulars, and guidance.Footnote 3 All of them, however, are derived from the 1944 Convention on International Civil Aviation, a multilateral convention with 193 member states.Footnote 4

The 1944 Convention on International Civil Aviation, commonly known as the Chicago Convention, is the primary source of international aviation law. Consisting of 96 articles, the Chicago Convention stipulates, among other matters, the legal regime of airspace and legal principles relating to aircraft and serves as the constituent instrument of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). ICAO was created and empowered by the Chicago Convention to develop principles for international air navigation and facilitate states’ co-operation in the safe and orderly development of international air transportation.Footnote 5 Since the adoption of the Chicago Convention in 1944, ICAO has adopted 19 annexes containing over 12,000 SARPs, many of which are evolving in concert with the latest developments and technological innovations.Footnote 6 These annexes focus, for instance, on personnel licensing (Annex 1), operation of aircraft (Annex 6), airworthiness of aircraft (Annex 8), aircraft accident and incident investigation (Annex 13), and safety management (Annex 19).

Following ICAO’s broad definition of ‘aviation safety’ as the ‘state of freedom from unacceptable risk of injury to persons or damage to aircraft and property’,Footnote 7 SARPs are generally related to aviation safety. A notable exception is Annex 16 (environmental protection), which consists of four volumes; namely, Volume I: Aircraft Noise, Volume II: Aircraft Engine Emissions, Volume III: Aeroplane CO2 Emissions and Volume IV: Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA). Volume III and Volume IV were adopted in 2017 and 2018, respectively, with the goal of reducing the impact of aviation-related carbon emissions on the global climate. The development of Annex 16 will be examined in Section 2.

Bilateral ASAs regulate the international carriage of passengers, cargo, and mail by air and determine the level of aviation market access between states. Before an airline can operate international services to another country, its government must first conclude an ASA with the government of the destination country. One of the earliest ASAs is the one signed between the United States and the United Kingdom in 1946.Footnote 8 This agreement, often referred to as the Bermuda I Agreement, became the prototype for many subsequent ASAs around the world.Footnote 9 It is reported that a complex web of over 4,000 bilateral ASAs with variations in substance and style are in existence today.Footnote 10 Although various global multilateral approaches have been contemplated over time, none of them have been successful.Footnote 11 It is important to note that regional approaches have also been adopted around the world, with the European Union (EU) being an exceptional example.Footnote 12 That said, bilateral ASAs are the principal instruments for regulating market access in international air transportation.

The relationship between the Chicago Convention and ASAs has not been clearly defined in academic literature. A common understanding is that the Chicago Convention and ASAs are two separate branches of international aviation law because ASAs decide the level of market accessFootnote 13 while the Chicago Convention does not deal with market access. However, that understanding does not provide a full picture of their relationship. The focus of this article is the relationship between SARPs under the Chicago Convention and ASAs. Based on a textual and contextual interpretation of SARPs-related articles in the Chicago Convention and a review of 620 publicly available ASAs (from 1946 to 2022), it aims to clarify the interaction between SARPs and ASAs through doctrinal and empirical analyses. Notably, a descriptive quantitative analysis was conducted to supplement the doctrinal analysis in this article. Rather than exploring the relationship between variables, this article provides a descriptive account of the increasing inclusion of safety provisions in ASAs since the 1970s and of environmental provisions in the new generation of ASAs since the 2000s.

This article will show how SARPs on aviation safety are effectively enforced by ASAs and anticipate how SARPs on carbon emissions will gradually follow suit. The article is organized as follows. As a background, Section 2 describes how carbon emissions from international aviation have been (un-)regulated. Section 3 discusses the unique legal status of SARPs on a multilateral level. Based on a review of 620 publicly available ASAs, Section 4 presents the different levels of bilateral mechanisms for ensuring compliance with SARPs on aviation safety. Section 5 introduces a number of new ASAs that have started to cover environmental protection. Section 6 suggests how carbon emissions from international aviation will be regulated by ASAs.

2. International measures to limit the carbon emissions of international aviation

This section introduces the various efforts implemented under the Chicago Convention to limit the climate impacts of international aviation. In doing so, it first sketches out those climate impacts. After briefly covering how the UN climate regime deals with greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the aviation sector, it discusses the development of Annex 16 (Environmental Protection) on climate issues under ICAO’s purview.

2.1. The climate impacts of international aviation

Regulating the climate impacts of international aviation is of particular concern for efforts to mitigate global climate change. In 2018, international aviation produced 604 Mt CO2 emissions, or close to South Korea’s annual CO2 emissions.Footnote 14 A study conducted in 2018 by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reported that international aviation CO2 emissions account for 65 per cent of aviation emissions and 2.4 per cent of global anthropogenic emissions.Footnote 15 Furthermore, CO2 from international aviation has increased steadily and rapidly during the past decades.Footnote 16 The projected doubling of the global fleet in the next two decades means a further increase in CO2 emissions from this sector.Footnote 17

Beyond CO2 emissions, aircraft also produce short-lived climate forces, such as sulphur dioxide and nitrous oxide (NOx) emissions.Footnote 18 Although CO2 emissions are the largest contributor by far among GHG emissions,Footnote 19 the climate forcing of these non-CO2 emissions may be stronger than that of CO2 in some estimates, and accounts for 66 per cent of the net forcing of aviation.Footnote 20 The evolution in scientific understanding of the climate forcing of non-CO2 emissions will further reveal the climate impacts of aviation.Footnote 21 From 2020 to 2022, the COVID-19 pandemic led to an abnormally low level of international air passenger traffic,Footnote 22 corresponding to a sharp drop in CO2 emissions in 2020, around 59 per cent compared to the level in 2019.Footnote 23 After this temporary decline, international air traffic recovered swiftly and almost reached the pre-pandemic level by 2023,Footnote 24 along with the rebound of international aviation emissions.Footnote 25 Due to a continued rise in CO2 emissions from international aviation, there appears to be a need for greater global regulation.

2.2. The UN climate regime on international aviation

Reducing international aviation emissions through the UN climate regime – including the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), its Kyoto Protocol, and the Paris Agreement – has proven contentious.Footnote 26 The UNFCCC lays the legal foundation for climate change governanceFootnote 27 and develops two distinct obligations, procedural and substantial ones, for all parties. For the former, the UNFCCC requires its parties to develop and communicate ‘national inventories of anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of all GHGs not controlled by the Montreal Protocol’ with comparable methodologies agreed by the Conference of Parties (COP).Footnote 28 The COP 1 decided to follow the inventory guidelines adopted by the IPCC.Footnote 29 Accordingly, each party needs to report GHG emissions generated within its territory and, for mobile sources, emissions from the consumption of fuel sold by it, and all these emissions are included in a national total emissions.Footnote 30 As an exception, international aviation emissions should be reported separately and are not included in national totals. Footnote 31

Beyond reporting obligations, parties to the UNFCCC take substantive obligations to formulate and implement ‘programs containing measures to mitigate climate change’.Footnote 32 In contrast to relatively specific reporting obligations, the substantive obligation on climate change mitigation is open-ended. The UNFCCC does not restrict it to limiting and reducing emissions that the parties inventory and report.Footnote 33 In turn, the reporting obligations are not meant to reflect responsibility for controlling those emissions. As a result, whether to fulfil mitigation obligations through addressing international aviation emissions is left to the parties’ discretions.

Further, the reference to ICAO under the Kyoto Protocol incurs questions about the feasibility of regulating international aviation emissions under the UN climate regime. The Kyoto Protocol adopts quantified emissions limitation and reduction commitments for the developed country parties listed in Annex I of the UNFCCC, in the period from 2008 to 2020.Footnote 34 The accounting for quantified commitments follows the methods adopted by the IPCC,Footnote 35 which means the exclusion of international aviation and shipping emissions. To regulate these emissions, the Protocol requires Annex I parties to work through ICAO and the International Maritime Organization (IMO).Footnote 36 This arrangement does not necessarily mean excluding international aviation emissions from Parties’ general mitigation obligations under the UNFCCC. Still, the reason behind this arrangement, the failure to reach a consensus on distributing responsibility for these emissions,Footnote 37 implies to some extent that parties are reluctant to regulate international aviation emissions to meet their general mitigation commitments.

The adoption of the Paris Agreement does not change the status of international aviation under the UN climate regime. It is important to note that, unlike the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement makes no reference to emissions from international aviation.Footnote 38 This omission has led to various interpretations. Truxal noted that this ‘can be interpreted as giving ICAO a “free hand”, or as a vote of confidence in ICAO, or as a failure of ICAO to “step up”’.Footnote 39 Indeed, a former ICAO Council President viewed this as ‘a vote of confidence in the progress ICAO and the aviation community have achieved’.Footnote 40 However, Mayer and Ding argue that ‘no conclusion can be drawn from the absence of any mention of aviation in the Paris Agreement, as this treaty does not contain sector-specific provisions’,Footnote 41 and emphasize that ‘the negotiators discussed, but rejected, a draft provision encouraging the ICAO to regulate emissions from international aviation’.Footnote 42

At the same time, the Paris Agreement requires parties to develop nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and impose obligations on them to ‘pursue domestic mitigation measures’ to achieve mitigation targets in NDCs.Footnote 43 Developed country parties should adopt economy-wide emission reduction targets in NDCs, and developing country parties are encouraged to move toward such targets.Footnote 44 However, neither this Agreement nor the following COP decisions clarify the scope of the ‘economy-wide’ target, which fails to clarify whether that includes international civil aviation. The relevant practices of parties are diverse. For example, the EU has voluntarily included international aviation emissions in its NDCs,Footnote 45 while the UK has explicitly excluded these emissions.Footnote 46 In this sense, whether the parties take obligations to ‘pursue’ mitigation measures addressing international aviation emissions depends on how they define their emission reduction targets in NDCs.

In short, regulating international aviation emissions through NDCs under the UNFCCC or the Paris Agreement is an option. However, the vague mitigation commitments under the UNFCCC and the uncertainties related to the ‘economy-wide’ targets under the Paris Agreement cast doubt on the prospect of decarbonizing international aviation through the UN climate regime. Besides, rather than being subject to substantial decision-making processes under the UN climate regime, regulating international aviation emissions has been continuously addressed by the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technology Advice (SBSTA) based on reports provided by ICAO.Footnote 47 Such co-operation between the UN climate regime and ICAO draws attention to the development of climate initiatives under ICAO’s purview.

2.3. SARPs for addressing environmental protection and climate-related issues

ICAO’s aims and objectives as a UN specialized agency are to ‘develop the principles and techniques of international air navigation and to foster the planning and development of international air transport’.Footnote 48 Even though the Chicago Convention does not explicitly address the environment or environmental protection, that does not necessarily mean that ICAO lacks legal authority in this area.Footnote 49 To the contrary, environmental protection has become an essential component of ICAO’s mission since the 1970s, with the adoption of SARPs included in Annex 16.

Article 37 of the Chicago Convention may be read as implying a mandate of ICAO on environmental protection by providing that ‘the International Civil Aviation Organization shall adopt and amend … international standards and recommended practices … dealing with … such other matters concerned with the safety, regularity, and efficiency of air navigation as may from time to time appear appropriate’.Footnote 50 This open provision gives ICAO the flexibility to adopt SARPs even if the subject matter is not specifically mentioned in Article 37 (a)–(k) of the Chicago Convention.Footnote 51 In fact, ICAO has gone beyond the subjects listed in Article 37 many times.Footnote 52

The origin of Annex 16 (Environmental Protection) had nothing to do with carbon emissions. That annex was first adopted in 1971 to tackle aircraft noise. Realizing the environmental impacts of international aviation, states reached a resolution in the Eighteenth ICAO Assembly in 1971 on ICAO’s responsibility to balance the development of civil aviation and the ‘quality of the human environment’.Footnote 53 Consequently, the ICAO Council has adopted SARPs and designated them in Annex 16, Volume I: Aircraft Noise in 1971.Footnote 54 With a view to developing specific SARPs for aircraft engine emissions, the Committee on Aircraft Engine Emissions was established in 1977 by the ICAO Council and new SARPs for engine emissions were adopted in 1981Footnote 55 in Volume II: Aircraft Engine Emissions.Footnote 56 However, it is important to note that local air quality was considered when Volume II was adopted; the engine certification process entailed therein is based on the landing and take-off cycle, addressing pollutant emissions in the vicinity of airports.Footnote 57

Given growing concerns about climate impacts in the early 1990s, the 29th ICAO Assembly in 1992 decided to incorporate climate issues within the scope of environmental initiatives that should be kept within ICAO’s purview.Footnote 58 In addition to technical solutions that ICAO has continued to emphasize, it has started to consider various forms of market-based measures (MBMs), such as emissions-related levies to emissions trading since 2001,Footnote 59 and taken carbon offset mechanisms into consideration in 2007.Footnote 60

However, ICAO negotiations on climate change mitigation lagged far behind, especially considering the fast expansion of the air transportation market and the market’s increasing climate impacts.Footnote 61 Frustrated by ICAO’s slow progress, the EU decided to extend its emissions trading scheme (ETS) to international flights, including intra-EU flights as well as flights arriving in or departing from airports in the EU in 2008.Footnote 62 This decision aroused both political and legal controversy.Footnote 63 Finally, the EU decided to ‘stop the clock’ and constrain the geographical scope of its ETS to flights within and between states in the European Economic Area in 2013.Footnote 64 Even after such a retreat, the EU’s unilateral action catalysed progress in multilateral negotiations about climate regimes under ICAO.Footnote 65

Since 2010, ICAO negotiations have led to some agreements with substantial impacts on limiting international aviation emissions. The Assembly in 2010 defined the global aspirational goals for climate change mitigation in international civil aviation, including fuel efficiency improvementFootnote 66 and keeping ‘global net carbon emissions from international aviation from 2020 at the same level (CNG 2020)’.Footnote 67 Furthermore, the Assembly set the Council’s working agenda: developing global CO2 standards for aircraftFootnote 68 and exploring the feasibility of a global MBM scheme.Footnote 69

The Council sought to fulfil this mandate by adopting new SARPs on aircraft CO2 certification and designating them as Annex 16, Volume 3: Aeroplane CO2 Emissions in 2017.Footnote 70 These SARPs apply to new types of aircraft from 2020 and to aircraft in production from 2023.Footnote 71 Also, aircraft currently in production that fail to meet relevant standards cannot be produced from 2028.Footnote 72 Essentially, Volume III: Aeroplane CO2 Emissions ensures that aircraft manufacturers engaged in international flights comply with CO2 certification requirements. It aims to have a direct impact by increasing the importance of fuel efficiency in the aircraft design process.Footnote 73 As aircraft manufacturers sell aircraft globally, they are strongly incentivized to comply with ICAO Standards, including Annex 16, Volume III: Aeroplane CO2 Emissions. The direct impact of Volume III is on a limited number of states that are home to major commercial aircraft manufacturers such as Boeing (US), Airbus (EU), Embraer (Brazil) and COMAC (China).Footnote 74

In parallel to adopting these technical standards, the ICAO Council examined various forms of MBMs. Finally, the 2016 ICAO Assembly approved the global MBM scheme CORSIA.Footnote 75 The ICAO Council adopted SARPs on CORSIA as Annex 16, Volume 4: CORSIA in 2018.Footnote 76 This scheme aims to maintain CO2 emissions from international aviation at the 2020 level by requiring airlines to acquire and cancel eligible carbon credits from climate programs elsewhere.Footnote 77

The implementation of CORSIA started with a ‘pilot phase’ from 2021 to 2023, followed by a ‘first phase’ from 2024 to 2026. In these two phases, states’ participation is voluntary. In the second phase, from 2027 to 2035, the scheme applies to all ICAO member states except the least developed countries, small island developing states, and land-locked developing countries.Footnote 78 As of September 2024, 129 states have announced their intention to participate in this scheme.Footnote 79 The Council initially set the average of total CO2 emissions covered by CORSIA in 2019 and 2020 as the baseline.Footnote 80 Due to the abnormally low level of aviation emissions in 2020, using the original baseline would mean 30 per cent more stringent offsetting requirements than the pre-pandemic level.Footnote 81 The additional mitigation burdens was a major concern for the aviation industry, especially considering its priority on recovery from the pandemic.Footnote 82 As a result, the Council adjusted the baseline used in the pilot phase to the value of 2019 emissions, and the 2022 Assembly set 85 per cent of that value as the baseline in the first and second phases.Footnote 83 Indeed, after the three years of hardship (2020–2022), the aviation market has recovered from the pandemic faster than expected.Footnote 84

CORSIA has attracted broad attention from industries and scholars.Footnote 85 On the one hand, it is a milestone in regulating international aviation emissions in a multilateral forum.Footnote 86 As a part of the ‘basket of measures’ adopted by ICAO, CORSIA complements the other measures in the basket by offsetting the amount of CO2 emissions that cannot be reduced through the use of technological improvements, operational improvements, and sustainable aviation fuels.Footnote 87 On the other hand, this scheme has various limitations regarding its design elements, such as the exclusion of non-CO2 emissions and an internal logic that aims to offset the increase in CO2 emissions rather than limiting them fundamentally.Footnote 88

Beyond these technical constraints, the legal force of Annex 16, Volume 3: Aeroplane CO2 Emissions and Annex 16, Volume 4: CORSIA is uncertain due to the ambiguous legal status of SARPs. The key question is about enforcement: what are the consequences if states do not comply with Annex 16? The following sections discuss the legal status and consequences of non-compliance with SARPs.

3. Legal status of SARPs

The Council of ICAO (hereinafter ‘ICAO Council’) has mandatory functions, one of those functions being the adoption of SARPs. Before being officially adopted by the ICAO Council, the development of SARPs follows a multi-stage process involving many technical and non-technical bodies that are either within ICAO or closely associated with ICAO and ICAO member states.Footnote 89 Article 54 (l) of the Chicago Convention states that ‘The Council shall … adopt … international standards and recommended practices; for convenience, designate them as Annexes to this Convention’. Thus, SARPs are grouped into 19 Annexes to the Convention.

The first question that should be addressed is whether those 19 Annexes are an integral part of the Chicago Convention. Although there is a view that this question is ‘largely academic’ as SARPs are highly authoritative in practice,Footnote 90 this is a fundamentally important question, and the author is of the view that the Annexes are not an integral part of the Chicago Convention. First, from the perspective of treaty law, it is a general practice to explicitly provide that the annex is integral to the treaty when a treaty has an annex.Footnote 91 In other words, ‘unless there is an express provision that a particular document or documents are integral to the treaty, the presumption is that they are not’.Footnote 92 There is no such provision in the Chicago Convention and the Annexes. Second, by emphasizing the words of ‘for convenience’ in Article 54 (l), it can be argued that the Annexes are not an integral part of the Chicago Convention but are so designated only for convenience.Footnote 93 Third, the Chicago Convention drafters emphasized the flexibility of the Annexes and their difference with the Convention as below:

In consideration of the recognized need for the utmost flexibility in the adoption and amendment of Annexes, in order that they may be kept abreast of the development of the aeronautical arts, the Convention leaves the Council with a free hand for future action. No Annex is specifically identified in the Convention; and there is no limit to the adoption by the Council of any Annexes which may in future appear to be desirable. On the other hand, and in fact as a necessary consequence of that flexibility, the Annexes are given no compulsory force. It remains open to any State to adopt its own regulations in accordance with its own necessities.Footnote 94

The Annexes can basically be described as associated documents of the Chicago Convention. However, they are not an integral part of the Chicago Convention, and therefore SARPs do not have the same legal force as the Chicago Convention itself. That SARPs do not have the same legal force as the Chicago Convention does not stop the discussion about their legal status.

Essentially, there are three questions in relation to the legal status of SARPs: (i) Is there a legal obligation for states to comply with SARPs? (ii) What are the consequences if states fail to report to ICAO their departure from SARPs? (iii) What are the consequences if states do not comply with SARPs even after agreeing to comply? An analysis of these questions should start with Article 37 of the Chicago Convention (Adoption of International Standards and Procedures). That article stipulates that

each contracting State undertakes to collaborate in securing the highest practicable degree of uniformity in regulations, standards, procedures and organization in relation to aircraft, personnel, airways and auxiliary services in all matters in which such uniformity will facilitate and improve air navigation.

The interpretation of ‘undertakes to collaborate’ is essential to understanding the legal force of these standards and states’ obligation to comply with them. The International Court of Justice’s judgment in the Genocide case is helpful in grasping the meaning of ‘undertake’:

The ordinary meaning of the word ‘undertake’ is to give a formal promise, to bind or engage oneself, to a pledge or promise, to agree, to accept an obligation. It is a word regularly used in treaties setting out the obligations of the contracting parties. It is not merely hortatory or purposive.Footnote 95

Following this reasoning, the ‘undertake’ in Article 37 of the Chicago Convention suggests that states are making a commitment, in contrast with hortatory or purposive language that is completely non-binding.Footnote 96 At the same time, the imperative force of ‘undertake’ in terms of the application of standards is less strong than that of ‘shall’ adopted in other provisions in the Chicago Convention.Footnote 97 Besides, what states have committed to under Article 37 is to ‘collaborate’, rather than to ‘comply with’ standards.Footnote 98 Furthermore, the phrase ‘the highest practicable degree of uniformity’ offers considerable flexibility to states over the domestic application of standards.

Apart from a textual approach of Article 37 of the Chicago Convention, the legal obligation of SARPs should be interpreted together with ICAO member states’ obligation from Article 38 (Departures from International Standards and Procedures). That article allows states to deviate from standards when it is ‘impracticable to comply in all aspects with any such international standard or procedure’. However, in that case, the state in question ‘shall give immediate notification to the International Civil Aviation Organization of the differences between its own practice and that established by the international standard’.Footnote 99 This option of opt-out system with mandatory reporting under Article 38 supports the legal obligation for states to comply with SARPs. In other words, states that do not report that difference are bound to comply with SARPs. As Milde noted, ‘the weak international commitment in Article 37 of the [Chicago] Convention must be complied with in good faith by all [Member] States, and the duty to notify any differences under Article 38 is an unconditional legal obligation’.Footnote 100

This leads to the second question: What are the consequences if states fail to report to ICAO their departure from SARPs? In fact, it has been reported that many states with limited technical and economic resources often fail to notify ICAO under Article 38 of the Chicago Convention of their inability to implement the standards.Footnote 101 However, the Chicago Convention does not have an effective enforcement mechanism for noncompliance with Article 38. A more direct question to the legal power of SARPs is the third question: What are the consequences if states do not comply with SARPs even after agreeing to comply? As an international organization, ICAO does not have procedures for enforcing compliance with SARPs.

ICAO’s lack of power for sanctioning noncompliance with SARPs led to unilateral action in the 1990s. The United States adopted the International Aviation Safety Assessment (IASA) program in 1992,Footnote 102 and the EU launched the Safety Assessment of Foreign Aircraft (SAFA) program in 1996.Footnote 103 Under the IASA program, the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) visits foreign states whose air carriers operate or seek to operate in the United States to assess the state’s ability to comply with SARPs on safety issues, especially Annex 1 (Personal Licensing), Annex 6 (Operation of Aircraft) and Annex 8 (Airworthiness of Aircraft).Footnote 104 Accordingly, states are classified into Category One (those that adhere to SARPs) and Category Two (those that fail to adhere). Air carriers from Category One States can receive operating permissions, while carriers from Category Two States are prohibited from expanding their services or commencing operations.Footnote 105 The EU’s SAFA program focuses on the aircraft’s compliance with relevant safety standards.Footnote 106 EU member states conduct ramp inspections on third-country aircraft that land at their airports.Footnote 107 Ramp inspections are essentially on-site checks to ensure aircraft’s compliance with safety standards. This program was later expanded to the inspections of aircraft under the safety oversight of EU member states.Footnote 108 According to inspection results, EU member states can require aircraft operators to address deficiencies before a flightFootnote 109 or even impose a ban or conditions on the operation of a non-complaint aircraft.Footnote 110

The development of these audit programs served as the impetus for establishing a global audit program under ICAO’s purview.Footnote 111 The 32nd ICAO Assembly in 1998 decided to establish the Universal Safety Oversight Audit Programme (USOAP) ‘comprising regular, mandatory, systematic and harmonized audits’ and directed the Council to bring it into effect from 1 January 1999.Footnote 112 This program applied to all contracting states with their consent.Footnote 113 It aimed to promote global aviation safety by auditing the effectiveness of states’ implementation of safety oversight, determining their conformity with standards, observing and assessing their adherence to recommended practices, and advising states about how to improve their audit capability.Footnote 114

After completing its auditing work, the ICAO audit team deliver final reports containing the findings of non-compliance with regulations promulgated by states or provisions of the Convention, nonconformity with ICAO standards, and non-adherence to recommended practices or other guidance materials.Footnote 115 Since the results of the USOAP audits are made available to all other member states,Footnote 116 ICAO is able to have a ‘name and shame’ effect despite its lack of enforcement measures for SARP noncompliance. Although the USOAP helps raise the level of SARP compliance, the legal force of SARPs is not strong enough on a multilateral level. Bilateral ASAs, however, provide more powerful and effective measures. The analysis in the following sections will examine how ASAs can help implement SARPs, first by focusing on safety provisions in Section 4, then turning to environmental provisions in Section 5.

4. ASA mechanisms for enforcing compliance with SARPs on aviation safety

The purpose of this section is to demonstrate how ASAs provide enforcement mechanisms for SARPs on safety issues. As aviation safety and environmental protections are the core principles of SARPs,Footnote 117 it will offer insights about how ASAs can interact with SARPs on environmental protection, particularly on carbon emissions.

The following section traces this progress by examining 620 publicly available ASAs between different states on a best-effort basis. The timeframe of the 620 ASAs is as follows. There are ten from the 1940s, 11 from the 1950s, 21 from the 1960s, 45 from the 1970s, 42 from the 1980s, 154 from the 1990s, 149 from the 2000s, 168 from the 2010s and 20 from the 2020s. These ASAs have been collected from two main sources: the publicly accessible archives of ASAs in respective domestic departments of transportation or other authorities and the ICAO database of aeronautical agreements and arrangements (DAGMAR) that serves as a registry of ASAs.Footnote 118 Given the fact that most ASAs are not publicly available, these two sources provide meaningful data sets to the best extent possible. To be clear, these data sets are a sample out of 4000+ ASAs. Therefore, it is possible that there are other ASA models that are designed to comply with SARPs on aviation safety. Another important consideration is that many states use Memorandums of Understanding, Annexes, or exchanges of letters as supplementary documents to ASAs that are not published as they are traditionally regarded as being confidential.Footnote 119 That implies that SARPs on safety issues could be included in those supplementary documents rather than in the texts of ASAs. Regardless, since the purpose of this section is to demonstrate that many ASAs interact with SARPs on aviation safety, missing ASAs will not bias the general findings.

The 620 publicly available ASAs (183 countries are a party to at least one of them) were collected as follows: 140 ASAs adopted by the United States from the database of the Department of State;Footnote 120 56 ASAs adopted by the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region from the database of agreements published by the Department of Justice;Footnote 121 58 ASAs adopted by Australia from the database of the department governing transportation;Footnote 122 103 ASAs adopted by India from the data on agreements provided by the Ministry of Civil Aviation;Footnote 123 seven ASAs adopted by New Zealand from the database on all its treaties;Footnote 124 12 ASAs adopted by the United Kingdom from the archives of bilateral treaties;Footnote 125 two ASAs adopted by Iceland from the list published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs;Footnote 126 76 ASAs adopted by China from the database of the Civil Aviation Administration;Footnote 127 31 ASAs adopted by Korea from the database on foreign policy;Footnote 128 six ASAs adopted by the EU from the database of EU legislation;Footnote 129 and 64 ASAs adopted by Canada from the dataset of the Treaty Law Division of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Development.Footnote 130 Other ASAs, including 33 adopted by Singapore, seven adopted by Korea, and 25 adopted by China, were retrieved from DAGMAR.

Safety clauses are incorporated in 58 per cent of the reviewed ASAs. In this review, safety clauses consist of (i) clauses titled ‘aviation safety’ or ‘safety’ in ASAs, (ii) clauses titled ‘airworthiness’ in ASAs specifying that states may hold consultations about safety standards and (iii) clauses titled ‘recognition of certificates and licenses and safety’. In essence, they are clauses that specifically mention safety standards in the text. Although 42 per cent of the reviewed ASAs do not have safety clauses, a vast majority of those ASAs (237 out of 263) were concluded in the twentieth century. Thus, revised ASAs that are not publicly available are also likely to include safety clauses.

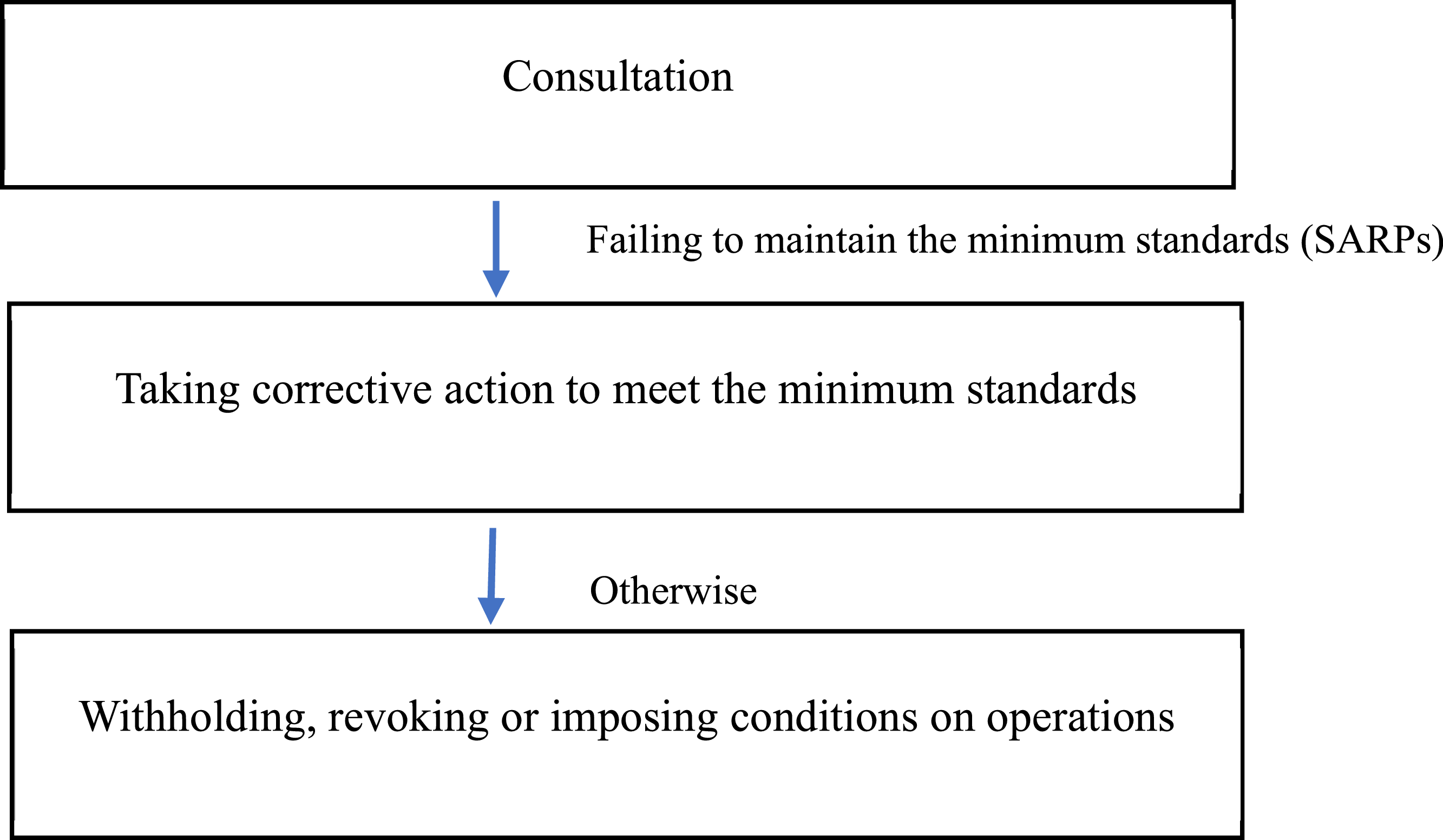

It is important to note that the earliest ASAs, Bermuda I-type Agreements, did not incorporate a safety clause, except for a reproduction of Article 33 of the Chicago Convention on the mutual recognition of certificates and licenses.Footnote 131 Starting in the 1970s, a separate clause on safety issues appeared in some ASAs. A typical example is the new ASA adopted by the United States and the United Kingdom in 1977, often called the Bermuda II Agreement.Footnote 132 The safety provision in this agreement operates in three steps: consultation, requesting corrective actions and withholding operating authorization. Each contracting party can request consultations ‘concerning the safety and security standards and requirements’ maintained by the other party. Further, the requesting party shall notify the other one of findings on its failure to ‘maintain and administer safety and security standards and requirements … that are equal to or above the minimum standards that may be established pursuant to the Convention’, as well as the necessary corrective actions. The other party should take ‘such appropriate action within a reasonable time’; otherwise, the requesting party can withhold, revoke, or impose conditions on operating authorization.Footnote 133 Out of the 58 per cent of the reviewed ASAs that incorporate safety clauses, nearly all these safety clauses take this basic three-tier mode (see Figure 1).Footnote 134

Figure 1. Basic structure of aviation safety enforcement mechanism.

Beyond the three-tier measures, many ASAs show some variations (see Figure 2). Some ASAs allow each contracting party to make ramp inspections,Footnote 135 reproducing Article 16 of the Chicago Convention on the search of aircraft.Footnote 136 When ramp inspection gives rise to serious concerns that an aircraft or its operation does not meet minimum standards or that safety standards are not being effectively maintained, the inspecting party is free to conclude that the other party is failing to meet relevant ICAO standards.Footnote 137 Denying ramp inspections can constitute grounds for the requesting party to freely ‘infer the serious concerns’ and ‘draw the conclusions’ referred to above.Footnote 138 Of the safety provisions in the reviewed ASAs, 53 per cent incorporate the provision of ramp inspections following the three-tier measures, and 36 per cent of them specify the consequences of such inspections. Of safety provisions, 11 per cent require the contracting party to inform the ICAO Secretary General if the other party remains in non-compliance with minimum standards, as well as the subsequent satisfactory solution.Footnote 139 However, these provisions are silent on what the ICAO Secretary General can actually do. In addition to these step-by-step measures, 69 per cent of the safety clauses allow for immediate action. If it is essential to the safety of aircraft operation, contracting parties can immediately suspend or vary operating authorization even before the consultation and the conclusion of the ramp inspection.Footnote 140 A very few ASAs – only two among all the ones reviewed – include all the above measures in one safety clause.Footnote 141

Figure 2. Comprehensive structure of aviation safety enforcement mechanism.

The review of ASAs at different stages shows the broad spectrum of forms that safety clauses take. Even with great variation in wording and detailed measures, the shared logic behind these safety clauses is to ensure that the contracting parties comply with the safety standards established by ICAO in at least three senses. First, the main focus in the consultation procedure is to examine whether other parties ‘effectively maintain and administer safety standards and requirements equal to or above the minimum standards established pursuant to the [Chicago] Convention’.Footnote 142 Such ‘minimum standards established pursuant to the Convention’ are also the benchmark against which one contracting party assesses the ‘validity of the aircraft documents and its crew and conditions of aircraft and its equipment’Footnote 143 during the ramp inspection of another party’s aircraft.

Those safety clauses in ASAs impose obligations on contracting parties to take corrective action to meet the minimum standards.Footnote 144 In contrast to the vague wording in Article 37 of the Chicago Convention (‘undertakes to collaborate in securing the highest practicable level’), the language in ASAs is straightforward. Consequently, if one party finds that the other party does not effectively maintain and administer safety standards, the other contracting party is required to take appropriate corrective action. Such arrangements in ASAs strongly encourage states to comply with SARPs on safety issues.

Most importantly, safety clauses in ASAs specify the consequences of failing to meet such minimum standards; namely, withholding, revoking, or imposing conditions on operating authorization. In 36 per cent of the reviewed ASAs, failure to comply with ICAO safety standards is grounds for revoking or limiting authorization. With this serious economic punishment, the minimum safety standards (that is, SARPs) offer powerful enforcement measures.

Overall, ASAs interconnect with the SARPs adopted by ICAO and together form a net for regulating safety issues in international civil aviation. The safety clauses in ASAs explicitly define the obligations for contracting parties to enforce ICAO’s safety standards, which specify states’ commitments to secure ‘the highest practicable degree of uniformity’ in standards under the Chicago Convention. Further, ASAs offer a wide spectrum of enforcement measures, ranging from the moderate to the serious – that is, from consultation to restricting or even revoking operating authorization.

5. Environmental clauses in ASAs

The well-established mechanism of regulating aviation safety issues by ASAs provides a lesson on the regulation of carbon emissions from international civil aviation. In brief, ASAs can be instrumental in promoting states’ implementation of SARPs on environmental protection despite the weakness of SARPs on a multilateral level. After outlining the environmental provisions in ASAs, this section will evaluate the different nuances of these provisions in addressing international aviation emissions. This section will show that environmental clauses in ASAs are developing from simply including environmental clauses without binding language to having CORSIA-specific clauses that will interact with the ICAO-developed SARPs.

The environment was not a topic in ASAs in the twentieth century, but since the 2000s, some ASAs have started to incorporate the environment. The EU–US ASA adopted in 2007 set a precedent for environmental provisions that was amended by the protocol adopted in 2010. Environmental provisions are included in 20 other ASAs reviewed for this article. Although that number is small, it is very likely that other ASAs contain environmental provisions as well. Not only are there many more ASAs that are not publicly available, but many states use supplementary documents to ASAs (e.g., Memorandums of Understanding, Annexes or exchanges of letters) that are generally confidential.Footnote 145 The environment is an issue that can be included in those supplementary documents. Although this survey on environmental provisions in ASAs is admittedly incomprehensive, various environmental provisions below provide exemplary structures and modalities. Broadly, three categories of environmental clauses have been observed.

5.1. Environmental clause with hortatory language

The first group of environmental clauses derives from the EU’s new ASAs with various countries: namely, the US (2007 and 2010), Canada (2010), Morocco (2006), Jordan (2012), and Israel (2013). The adoption of environment clauses in those ASAs demonstrates one of the objectives behind the EU’s external aviation policy – to ‘ensure overriding public safety and security and environmental goals’.Footnote 146 In the EU–US ASA, the lengthy ‘Environment’ articleFootnote 147 broadly categorizes three environmental measures: aspirational pledges, responses to the aircraft noise issue, and consultation and co-ordination through the joint committee. Aspirational pledges emphasize on environmental protection, calling for parties to ‘work together’ and to consider ‘regional, national, or local’ environmental measures evaluating the adverse effects of environmental measures on exercising economic rights, and exchanging environmental information.Footnote 148 Article 15, Paragraph 3, of the ASA contains binding commitments on the enforcement of environmental standards established by ICAO.Footnote 149 To be clear, this ASA was established before CORSIA, and its focus was aircraft noise under Annex 16, Volume 1: Aircraft Noise. Under this ASA, the joint committee is mandated to develop recommendations to address the ‘overlap’ between national MBMs and avoid duplication. Additionally, the joint committee should assess the legitimacy of national environmental measures upon the parties’ request. Seemingly, such arrangements reflect the history of the EU’s controversial decision to extend ETS to international aviationFootnote 150 and correspond to general guidance on considering ‘regional, national, or local’ environmental measures.

The environmental provision in the EU–Canada ASAFootnote 151 follows the pattern established by the EU–US ASA but with some variations. To be specific, the EU–Canada ASA duplicates the indefinite guidance on environmental protection in the EU–US ASA.Footnote 152 However, neither of the two ASAs mentions the climate impacts of international civil aviation. Rather than requesting an exchange of information, the EU-Canada ASA defines the parties’ obligation to consult each other on various environmental matters.Footnote 153 In addition to enforcing ICAO’s environmental standards, this ASA obliges parties to apply environmental measures ‘without distinction as to nationality’.Footnote 154

There are environmental provisions in the Euro–Mediterranean aviation agreements between the EU and Morocco (2006), Jordan (2012), and Israel (2013). The common elements shared by this group of environmental clauses are the obligation for states to conform with SARPs on aircraft noiseFootnote 155 and the confirmation of their right to apply environmental measures ‘without distinction as to nationality’.Footnote 156 However, they are silent about climate impacts.

As one of the first ASAs that incorporated environmental provisions, the EU–Morocco ASA addresses the issue only briefly.Footnote 157 That shows, however, that there are more details in the confidential annex of the ASA. The EU–Jordan and EU–Israel ASAs incorporate some extra components, such as hortatory provisions on the significance of environmental protection and co-operation between the contracting parties.Footnote 158 The EU–Israel ASA further ‘acknowledges’ the need for ‘effective global, regional, national and/or local action’.Footnote 159

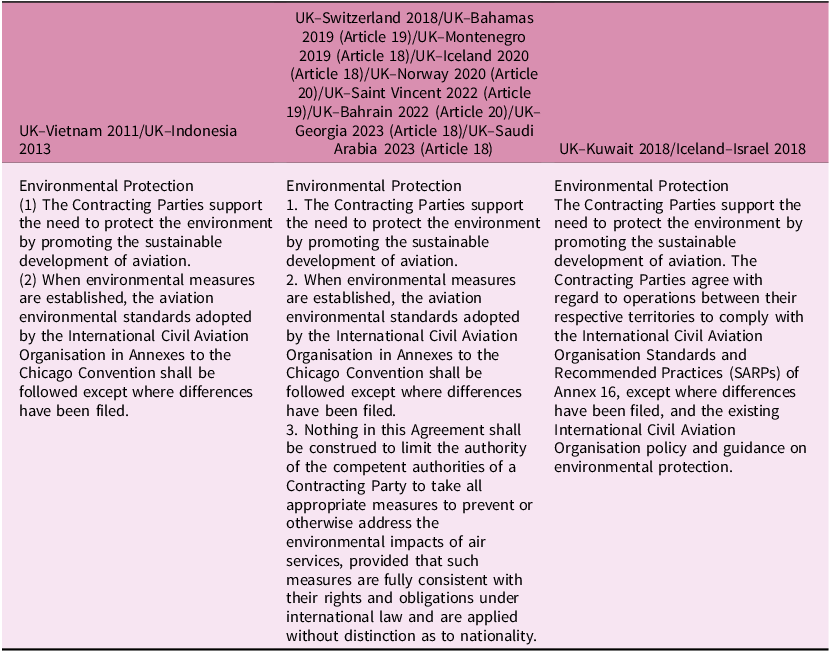

5.2. Environmental clause with obligation to comply with environmental SARPs

The second group refers to environmental provisions in the ASAs reached by the UK, Iceland, and other states. These articles on ‘Environmental Protection’ in this group are remarkably similar (see Table 1). The provision starts with an introductory description of the states’ consensus on supporting ‘the need to protect the environment by promoting the sustainable development of aviation’.Footnote 160 The phrases following this general description set the obligations of the contracting parties to enforce environmental standards adopted by ICAOFootnote 161 and apply appropriate environmental measures without distinction as to nationality.Footnote 162 While this group of environmental articles avoid lengthy wording and hortatory expressions, they do not specifically mention climate impacts. At the same time, it is important to note that most ASAs in this group were concluded after the adoption of Annex 16, Volume 4: Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA). Therefore, it can be assumed that SARPs on GHG are included in those ASAs.

Table 1. Sample environmental clauses with obligation to comply with environmental SARPs.

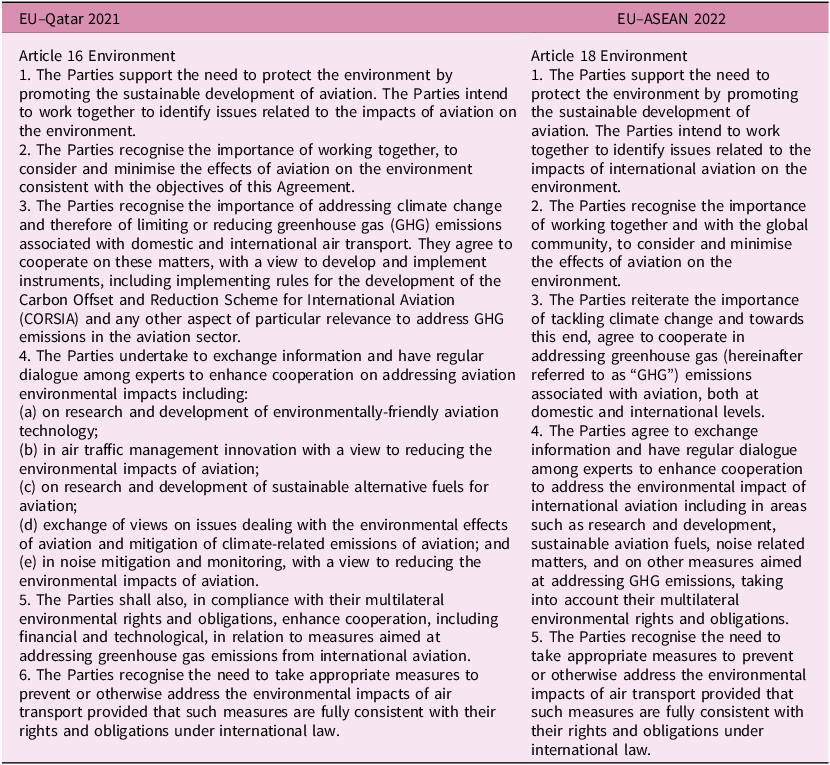

5.3. Environmental clause with reference to GHG emissions

The third group of environmental clauses in the EU–Qatar ASA and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)–EU ASA explicitly introduce a reference to reducing GHG emissions associated with domestic and international aviation (see Table 2).Footnote 163 At the same time, hortatory commitments were used instead of mandating conformity with environmental SARPs. In the EU–Qatar ASA, the contracting parties agree to co-operate on mitigating international aviation emissions ‘with a view to developing and implementing’ CORSIA and exchanging information on environmental impacts and mitigation options.Footnote 164 The EU–ASEAN ASA maintains the arrangement on dialogue and communication of information;Footnote 165 however, it does not specifically mention either ICAO or any SARPs on environmental issues.

Table 2. Sample environmental clauses with a reference to GHG emissions.

6. How carbon emissions from international aviation will be regulated by ASAs

The development of environmental provisions in ASAs, and especially the incorporation of the phrases ‘GHG emissions with aviation’ and ‘CORSIA’ in the EU–Qatar and EU–ASEAN ASAs, raise a significant question about these provisions’ implications for climate change mitigation in international aviation. This question can further be framed as two sub-questions: (i) Can environmental clauses in ASAs function as safety clauses to ensure states’ compliance with SARPs, especially Annex 16, Volume 4: CORSIA? (ii) Will other provisions in ASAs, most importantly those on revoking authorization, affect states’ compliance with SARPs on CORSIA, as they have incentivized action on aviation safety?

A comparative analysis of safety and environmental provisions in ASAs is critical to answering the first question. The examination of environmental provisions in ASAs finds that, even with many changes in form and phrasing, they consistently stress the co-operation between states in aspirational formulations but refrain from introducing legal obligations for environmental protection. The only obligation for environmental protection deriving from the EU–Qatar ASA is to enhance co-operation in mitigating international aviation emissions. The EU–ASEAN ASA does not have any such binding commitments.

Safety provisions in ASAs are distinct from those on environmental issues in two obvious ways. First, although safety provisions differ considerably across ASAs, they share the same message – they obligate states to conform with safety standards adopted by ICAO. Second, those safety provisions are accompanied by a package of enforcement measures, the most serious of which is revoking operating permissions authorized by the ASA. Together with substantial economic loss in the relevant aviation market, revoking authorization generates reputational damage for a state and undermines other states’ confidence in its safe governance, which further constrains its participation in other bilateral aviation markets.Footnote 166 In contrast, the environmental provisions in ASAs featuring hortatory phrases and the absence of enforcement measures have, at present, only a limited role in facilitating states’ conformity with CORSIA to address the climate impacts of aviation.

However, including the environment in ASAs is a growing and unavoidable trend that will only accelerate and expand due to the urgency of climate change. In addition, states that commit to comply with CORSIA would want to introduce the same standards under ASAs. To illustrate the point, if State A complies with CORSIA but State B does not, airlines from State A must comply with various regulatory requirements under CORSIA but airlines from State B do not need to comply. As discussed in Section 3, the Chicago Convention allows the possibility of noncompliance. Assuming that airlines from State A and State B compete in the same international aviation market, airlines from State A would protest about unfair competition as SARPs place a disproportionate burden on them, thereby weakening their ability to compete with airlines from State B. Therefore, State A will likely pressure State B to incorporate CORSIA in their ASA.

The gradual expansion of the scope of revoking authorization has significant implications as well. ASAs usually define the grounds for limiting or revoking authorization as the failure to meet safety standards, conditions about substantial local ownership of designated airlines, and requirements about security issues.Footnote 167 Interestingly, Article 5 of the EU–ASEAN ASA expands the scope of those grounds. It stipulates that this article ‘does not limit the right of any Party to refuse, revoke, suspend, impose conditions on, or limit the operating authorization or technical permissions … in accordance with the provisions of Articles 8, 15, 16, or 25’.Footnote 168 Article 8 of this ASA refers to the fair competition issue.Footnote 169 Accordingly, the failure of one party to fulfil duties pertaining to the provision of fair competition may face the same punishment as failure to maintain safety standards.

Such a development demonstrates a certain level of flexibility about the grounds for revoking operating authorization. It also implies that revocation of that authorization could be prescribed as a consequence of failure to enforce environmental standards, including CORSIA. Such a proposition may be especially feasible in ASAs between states with a strong political will for environmental protection.

Reducing the climate impacts of aviation through ASAs is likely to start with hortatory language in environmental provisions. Goldsmith and Posner note that hortatory wording helps give treaties flexibility, speed up negotiations and facilitate broad participation and effective implementation.Footnote 170 The flexibility inherent in hortatory clauses on environmental issues gives states room to upgrade them into legally concrete clauses with enforcement mechanisms. Thus, hortatory clauses are significant in that they can clarify states’ respective intentions and create common focal points for future co-ordination.Footnote 171 Following this argument, the adoption of hortatory environmental clauses can be interpreted as a stepping stone toward binding environmental provisions.

Another important trend is states’ changing attitude to aviation safety and environmental issues related to aviation in the context of global standards. Although states initially held starkly different attitudes towards adopting and implementing global standards in the fields of safety and emissions reduction,Footnote 172 that situation is changing. Some states have already started to reach a consensus on regulatory co-operation over safety and environmental issues in ASAs. A notable example is found in the EU–Qatar ASA, which groups together provisions on safety and the environment under the title of ‘regulatory cooperation’.Footnote 173 Many of New Zealand’s ASAs with other states prescribe the obligation to exchange information on environmental measures under the provisions of ‘Civil Aviation Safety Cooperation’.Footnote 174 This trend suggests a certain level of convergence in their stances on regulating safety and climate issues. It lays the groundwork for putting lessons learned from addressing safety issues – promoting states’ conformity with SARPs on safety issues through ASAs into regulating GHG emissions from international aviation by ASAs.

7. Conclusion

In his comprehensive analysis of GHG emissions from international aviation in 2015, Piera noted that ASAs make it harder for states to deviate from safety and security standards with the caveat that ‘this is not all the case with climate change’.Footnote 175 Yet he correctly predicted that ‘states could also gradually start introducing amendments to their ASAs to allow for the imposition of operational bans upon aircraft operators of other states to the extent that they are not in compliance with ICAO’s global MBM’.Footnote 176 Piera’s conclusion was based on the view that ASAs have served as ‘additional enforcers’ for ICAO standards.Footnote 177

In 2018, ICAO’s global MBM scheme was adopted in the name of CORSIA and designated in Annex 16 of the Chicago Convention. More and more states are explicitly committing to participate in the global MBM–CORSIA and applying relevant SARPs.Footnote 178 CORSIA will apply to the vast majority of ICAO member states from 2027. Despite its own limitations, CORSIA was the best possible outcome on which states with conflicting interests were able to agree. As the first global market-based measure for a particular sector, CORSIA will contribute to reducing GHG emissions by international aviation. That said, making rules is one thing, and enforcing them is another. Without enforcement mechanisms, CORSIA may not have a meaningful effect on reducing emissions.

Meanwhile, the transformation of ASAs deserves our scrupulous attention. From exclusively dealing with the exchange of commercial rights for international air transport, a new generation of ASAs have started to cover new issues, including the environment. This article ends with the prediction that as more and more ASAs address the environment, they will help effectively regulate GHG emissions from international aviation by enforcing CORSIA. Indeed, that change has already begun.