Introduction

Elasmobranchs (sharks, skates, and rays) host a remarkable diversity of symbiotic and associated species, both externally and internally, contributing significantly to the overall marine biodiversity (Caira and Healy, Reference Caira, Healy, Caira and McEachran2004; Zaragoza-Tapia et al., Reference Zaragoza-Tapia, Pulido-Flores, Gardner and Monks2020). In the Mediterranean Sea, this group includes 49 species of sharks and 36 species of rays (Bradai et al., Reference Bradai, Saidi and Enajjar2012), representing approximately 7% of the world’s cartilaginous fish species (Compagno, Reference Compagno1984a, Reference Compagno1984b; FAO, 2018; Last et al., Reference Last, Naylor and Manjaji-Matsumoto2016; Serena, Reference Serena2005; Séret and Serena, Reference Séret and Serena2002).

Concerning elasmobranch populations in the Algerian basin, data from the relatively limited ichthyological literature (Dieuzeide et al., Reference Dieuzeide, Novella and Roland1953; Lalami, Reference Lalami1971) and coastal observations indicate that large pelagic and solitary species are captured only sporadically (Hemida, Reference Hemida2005). Within this group, the genus Raja Linnaeus represents one of the most important elasmobranch lineages, comprising six species native to the Mediterranean Sea (Hemida, Reference Hemida2005). Among these, Raja asterias Delaroche (starry ray) and Raja radula Delaroche (rough ray) are considered typically Mediterranean species (Relini et al., Reference Relini, Orsi, Puccio and Azzurro2000; Serena et al., Reference Serena, Mancusi and Barone2010) and are regarded as relatively common in the region (Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Bauchot and Schneider1987). They play a vital role in benthic ecosystems (Fatimetou and Younes, Reference Fatimetou and Younes2016) and represent essential components of marine food webs due to their diet, which primarily consists of teleosts and molluscs (Capapé, Reference Capapé and Quignard1977; Fatimetou & Younes, Reference Fatimetou and Younes2016; Romanelli et al., Reference Romanelli, Colasante, Scacco, Consalvo, Grazia Finoia and Vacchi2007; Tai et al., Reference Tai, Ramdani, Benchoucha and Yahyaoui2011; Yemişkenet al., Reference Yemışken, Forero, Megalofonou, Eryilmaz and Navarro2018). These benthic species typically inhabit shallow waters with muddy or sandy bottoms, generally at depths of up to 150 m.

Beyond their ecological role in benthic habitats, these elasmobranchs are apex species in marine trophic hierarchies, playing a crucial role in maintaining the balance, stability, and resilience of marine ecosystems (Bustamante Diaz, Reference Bustamante Diaz2014). At the same time, they serve as hosts to a wide diversity of parasites, particularly helminths (Zaragoza-Tapia et al., Reference Zaragoza-Tapia, Pulido-Flores, Gardner and Monks2020). Among these, tapeworms represent the most significant group infecting elasmobranch fishes (Caira et al., Reference Caira, Healy and Jensen2017a; Haseli et al., Reference Haseli, Malek, Palm and Ivanov2012).

Globally, numerous studies have concentrated on the taxonomy, systematics, geographical distribution, and host specificity of tapeworms parasitizing elasmobranchs (Alexander, Reference Alexander1963; Caira and Jensen, Reference Caira and Jensen2017; Caira et al., Reference Caira, Healy and Jensen1999; Euzet, Reference Euzet1959; Jensen, Reference Jensen2005; Randhawa and Burt, Reference Randhawa and Burt2008; Ruhnke, Reference Ruhnke2011; Tyler, Reference Tyler2006; Williams, Reference Williams1966, Reference Williams1968, Reference Williams1969). However, research efforts remain geographically uneven, and the global species inventory of these parasite groups is still far from complete (e.g., Caira and Jensen, Reference Caira and Jensen2017; Caira et al., Reference Caira and Jensen2017, Reference Caira, Jensen, Ivanov, Caira and Jensen2017b; Randhawa and Poulin, Reference Randhawa and Poulin2010a, Reference Randhawa and Poulin2020). For example, only a limited number of studies have investigated the parasite fauna of elasmobranch fishes along the Algerian coast (Benmselem et al., Reference Benmeslem, Randhawa and Tazerouti2019; Tazerouti, Reference Tazerouti2007; Tazerouti et al., Reference Tazerouti, Kechemir-Issad and Euzet2009).

The present study focuses on the genus Acanthobothrium Blanchard, 1848, in R. asterias and R. radula off the Algerian coast, which represents the most diverse genus of flatworms reported as parasites of the spiral valve in Elasmobranchii (Caira and Jensen, Reference Caira and Jensen2001, Reference Caira and Jensen2017; Campbell and Beveridge, Reference Campbell and Beveridge2002; Maleki et al., Reference Maleki, Malek and Palm2015; Randhawa & Poulin, Reference Randhawa and Poulin2010b). There are 215 valid Acanthobothrium species parasitizing elasmobranchs as adults (Irigoitia et al., Reference Irigoitia, Franzese, Alarcos, Arredondo and Timi2025; Rodríguez-Ibarra et al., Reference Rodríguez-Ibarra, Adán-Torres, Ruiz-Escobar and Torres-Carrera2024; Zaragoza-Tapia et al., Reference Zaragoza-Tapia, Pulido-Flores, Gardner and Monks2020) and exhibit a strong specificity to their definitive host (Caira and Jensen, Reference Caira, Jensen, Waeschenbach, Olson and Littlewood2014; Williams, Reference Williams1966). Furthermore, this genus is recognized as an excellent model for future studies of host parasite co-speciation (Zaragoza-Tapia et al., Reference Zaragoza-Tapia, Pulido-Flores, Gardner and Monks2020).

Raja asterias hosts a diverse cestode fauna in the Mediterranean Sea, including the rhinebothriid Echeneibothrium variabile Van Beneden, Reference Van Beneden1850 (Van Beneden, Reference Van Beneden1850); the diphyllideans Echinobothrium typus Van Beneden, 1849 (Joyeux and Baer, Reference Joyeux and J-G1936), E. affine Diesing, Reference Diesing1863, E. harfordi McVicar, 1976, and E. brachysoma Pintner, 1889 (Tazerouti, Reference Tazerouti2007); as well as a single representative of Acanthobothrium, i.e., A. minus Tazerouti, Kechemir-Issad, & Euzet, Reference Tazerouti, Kechemir-Issad and Euzet2009 (Tazerouti et al., Reference Tazerouti, Kechemir-Issad and Euzet2009). Raja radula also harbours several cestode species, including E. typus (Azzouz-Draoui, Reference Azzouz-Draoui1985), E. affine (Azzouz-Draoui, Reference Azzouz-Draoui1985; Benmselem, Reference Benmeslem2021; Diesing, Reference Diesing1863; Tazerouti, Reference Tazerouti2007), E. harfordi (Benmselem, Reference Benmeslem2021), E. brachysoma (Azzouz-Draoui, Reference Azzouz-Draoui1985), and Echeneibothrium beauchampi Euzet, Reference Euzet1959 (Benmselem, Reference Benmeslem2021).

This parasitological survey focuses on A. minus, aiming to fill the existing knowledge gap through a comprehensive morphological re-description combined with a molecular characterization of the species since its first record in the Algerian Mediterranean Sea (Tazerouti et al., Reference Tazerouti, Kechemir-Issad and Euzet2009). Moreover, this study provides the first record of this parasite in R. radula, expanding its known host range in the Mediterranean region.

Material and methods

Host and parasite collection

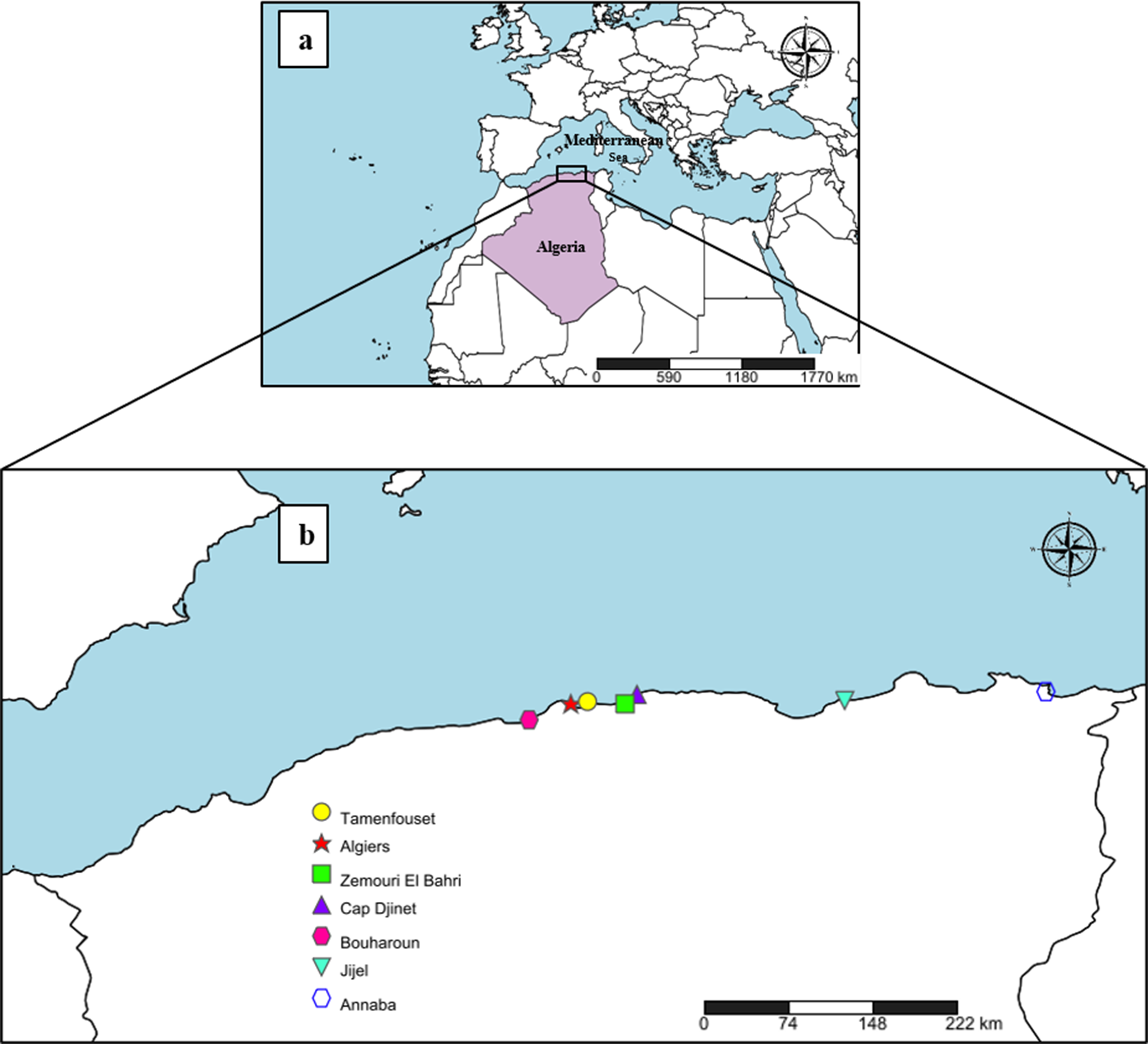

Between October 2023 and August 2025, 45 fresh specimens of R. asterias (19 males and 26 females) and 14 specimens of R. radula (4 males and 10 females) were examined. Samples were collected by bottom trawling along the Algerian coast, across various localities Fig.1 (coordinates correspond to the ports where skates were purchased from fishermen): Tamentfoust (36.805545° N, 3.229776° E), Algiers (36.785000° N, 3.065278°E), Zemmouri El Bahri (36.783333° N, 3.600000° E), Cap Djinet (36.875833° N, 3.717500° E), Bouharoune (36.625556° N, 2.653611° E), Jijel (36.816667° N, 5.766667° E), and Annaba (36.904167° N, 7.751944° E) (Fig 1), through the use of gill nets or small bottom trawls, in cooperation with local fishing communities. The specimens were promptly transported on ice in a cooler to the laboratory, where they were identified using FAO identification keys (FAO, 2009; Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Bauchot and Schneider1987). These identifications were confirmed via barcoding using the NADH2 gene. The total length and sex of each host specimen were recorded. Sex determination was performed by examining the claspers near the pelvic fins, with their presence indicating a male and their absence indicating a female.

Figure 1. (a) Geographic position of Algeria in the Mediterranean region; (b) collection sites of Raja asterias and Raja radula along the Algerian Mediterranean coast corresponding to ports where skates were purchased from fishermen (Created with https://www.simplemappr.net).

Morphological methods

The spiral intestines were injected with 8% formalin and preserved in 5% formalin. After several days of fixation, each spiral intestine was placed individually in a Petri dish filled with tap water. Under a stereomicroscope (Carl Zeiss™Stemi™2000 Stereomicroscope, Germany), the spiral valves were opened by following the turns of the spires to reveal the internal surface of each chamber. Using a probe, the surface of the mucosa was scraped gently and examined by performing several dilutions with tap water. The parasites were collected, counted, washed in physiological saline, and transferred to 70% ethanol, stained with acetic carmine, and dehydrated through an ethanol series (70%, 96%, and 100%). The parasites were cleared using clove oil (eugenol) and mounted onto glass slides in Canada balsam. Drawings were created using an Axioskop 50 microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a drawing tube, then scanned and refined using Adobe Illustrator CS5. Cestodes were identified using published identification keys (Euzet, Reference Euzet1959; Goldstein, Reference Goldstein1967; Rees and Williams, Reference Rees and Williams1965). Slides are deposited with the Natural History Museum (London, UK), under accession numbers NHMUK2026.1.19.1–11.

Hook measurement follows Euzet (Reference Euzet1959) and Ghoshroy and Caira (Reference Ghoshroy and Caira2001), and the designation of proglottid apolysis was done according to Caira et al. (Reference Caira, Healy and Jensen1999) and Franzese and Ivanov (Reference Franzese and Ivanov2018). The categorical assignment of Acanthobothrium according to Ghoshroy and Caira (Reference Ghoshroy and Caira2001) and Fyler and Caira (Reference Fyler and Caira2006) was used to facilitate comparisons among species recorded in the Mediterranean Sea. Prevalence, intensity of infection, and abundance were calculated according to Bush et al. (Reference Bush, Lafferty, Lotz and Shostak1997).

Of note, scanning electron micrographs are not provided. A single scolex was available for scanning electron microscopy and was smaller than the mesh associated with the holders for the critical point dryer available to us. We decided not to process this scolex for fear of losing the material. Furthermore, collecting additional material has proven to be challenging due to logistics and the low abundance of the parasite in both host species.

The molecular study

To confirm identification of host and cestodes, we extracted genomic DNA from 10 specimens of A. minus from the fresh spiral valve of the two skates, along with a piece of the host muscle tissue, and both were fixed in 100% ethanol. Host tissue samples from two skates identified as R. asterias and two as R. radula were used to confirm our morphological identification of these host species. The parasites were carefully divided into three parts: (1) the anterior part, containing the scolex; (2) the posterior part, containing the reproductive organs, were used for morphological study and/or to serve as hologenophores (sensu Pleijel et al., Reference Pleijel, Jondelius, Norlinder, Nygren, Oxelman, Schander, Sundberg and Thollesson2008); and (3) the median part was retained for molecular analysis.

For DNA extractions, a volume of 15 μL consisting of 2 μL of Milli-Q water (MQH₂O), 2 μL of Proteinase K, 10 μL of fish buffer (Devlin et al., Reference Devlin, Diamond and Saunders2004), and 1 μL of 20% Tween 20 was added to each sample tube. The tubes were gently flicked to mix the contents and briefly centrifuged. They were then incubated on a hot block at 65°C for 2 hours, with mixing and brief centrifugation every 20 minutes. After digestion, the temperature was increased to 95°C for 10 minutes to deactivate the Proteinase K. The samples were then cooled to room temperature for at least 20 minutes before being transferred to a freezer (<–20°C) for storage.

For cestodes, the 28S rDNA (large subunit ribosomal DNA) was amplified via PCR; 25 μL final volume PCR mix consisting of 0.35 μL of each specific primer (50 nM), i.e., T16 (forward) and T30 (reverse) or T01N (forward) and T13N (reverse) (Harper and Saunders, Reference Harper and Saunders2001) with a target length of approximately 750 and 1850 bp, respectively, 12.50 μL of MyTaq 2X Master Mix (New England Biolabs) (containing MgCl2, dNTPs, and Taq DNA polymerase), and 11.30 μL of MQH₂O. Subsequently, 0.5 μL of DNA template was added to each tube. For skate tissue, the NADH2 gene marker (target length of approximately 1100 bp) was targeted for amplification using primers ILEM (forward) and ASNM (reverse) (Naylor et al., Reference Naylor, Caira, Jensen, Rosana, White and Last2012) according to the same protocol as described above.

The prepared tubes were then loaded into a thermal cycler and subjected to amplification under an amplification protocol including an initial denaturation step of 4 minutes at 94°C, followed by 38 cycles of 30 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at 50°C (annealing), and 2 minutes at 72°C (extension), with a final extension at 72°C for 7 minutes (Beer et al., Reference Beer, Ingram and Randhawa2019; Harper and Saunders, Reference Harper and Saunders2001). Upon completion of the PCR, the amplified products were stored at 4°C until further analysis. PCR products were visualized under UV light following electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Ten microliters (10 μL) of each successful amplification product were purified using 2 μL of ExoSAP-IT (Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The purified PCR products were sequenced bidirectionally via Sanger sequencing at Microsynth (Germany), using the original PCR primers (20 nM). For cestode samples amplified using T01N and T13N, internal primers (20 nM) T16, T30, and SPF1 (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Jorge, Poulin and Randhawa2019) were sequenced as well. Sequences are available under Genbank accession numbers PX833960 to PX833962, while hologenophores are deposited with the Natural History Museum (London, UK) (NHMUK2026.1.19.9 and NHMUK2026.1.19.11).

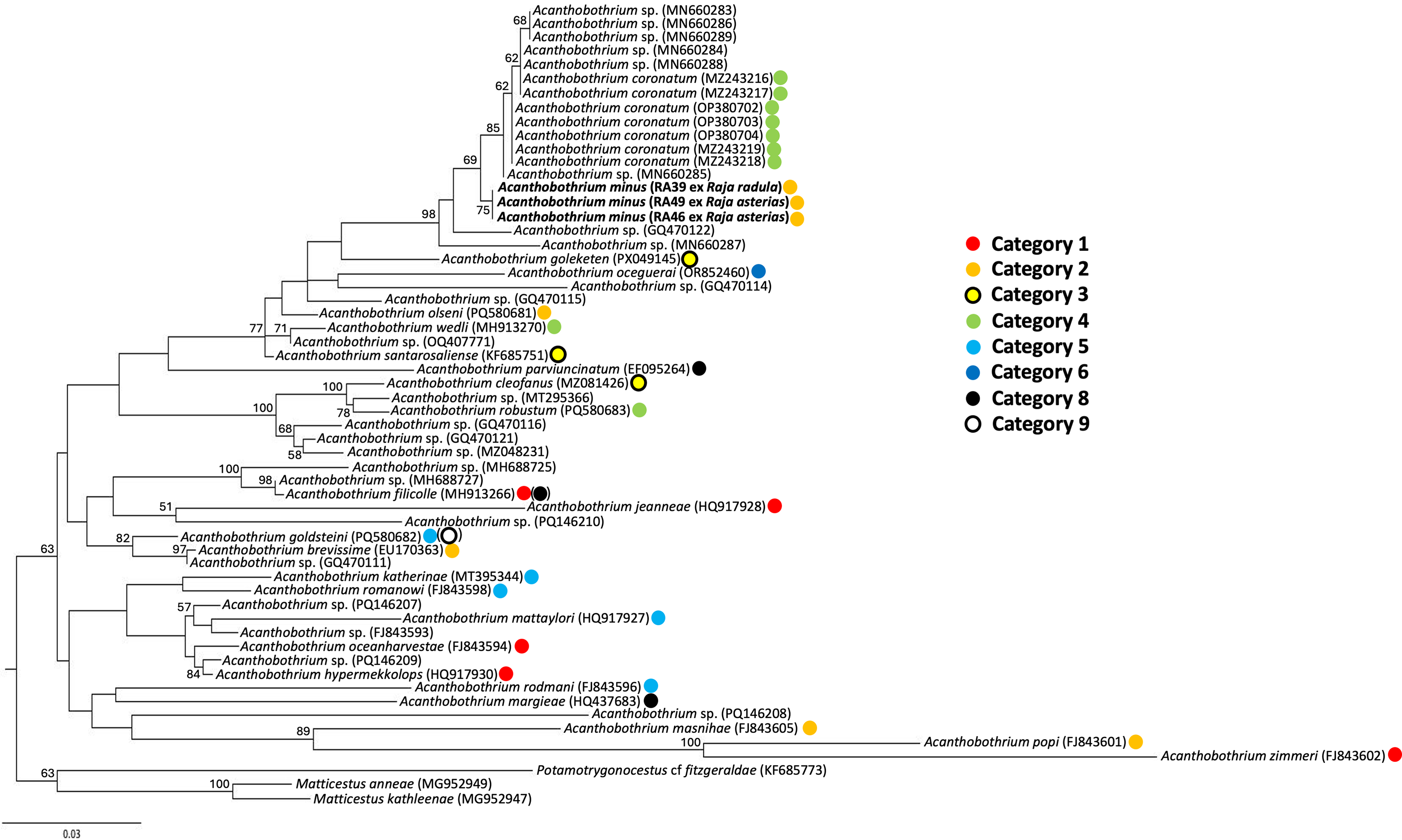

Sequences were edited manually using Sequencher 5.4.6 (Gene Codes Corporation) and screened for orthology with sequences from other Acanthobothrium species (28S rDNA) and Raja species (NADH2) using BlastN (McGinnis & Madden, Reference McGinnis and Madden2004). A phylogenetic approach using other Acanthobothrium sequences from Genbank (Table 1) was used to provide a framework within which to compare our sequences to previously published ones. These were aligned using MacClade 4.07 (Maddison & Maddison, Reference Maddison and Maddison2005). The automatic model selection – Smart Model Selection (Lefort et al., Reference Lefort, Longueville and Gascuel2017) – function in PhyML 3.0 (Guindon et al., Reference Guindon, Dufayard, Lefort, Anisimova, Hordijk and Gascuel2010) was used to determine the best nucleotide-substitution model for the sequence data. The Generalised Time Reversible model (GTR) with gamma distribution (G; estimated at 0.351) provided the best-fit to the data according to Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The alignment was analyzed by maximum likelihood (ML) in PhyML 3.0 with 100 bootstrap replicates.

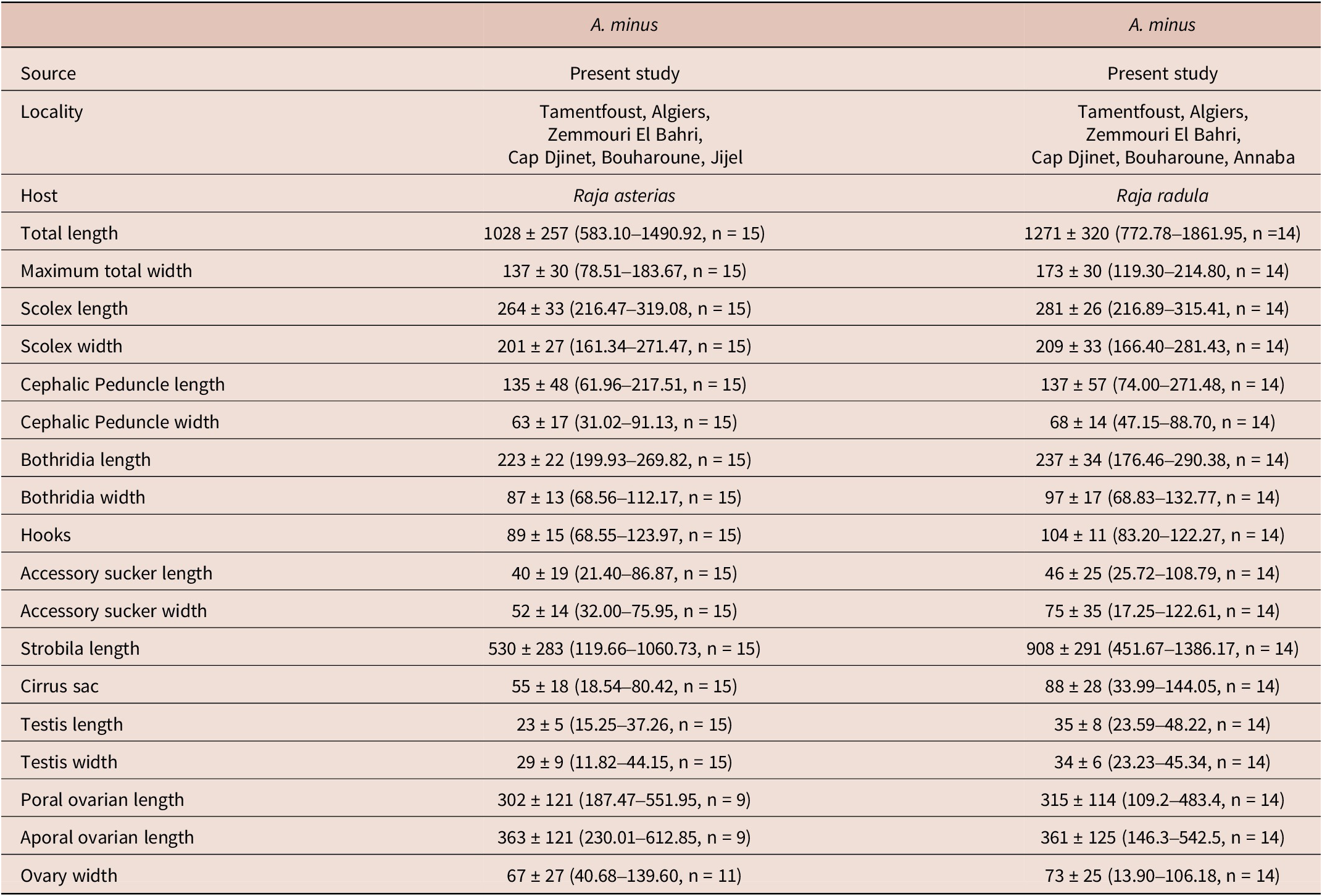

Table 1. List of taxa included in the phylogenetic analysis for Acanthobothrium, including host, locality, Genbank Accession number (GA No.), and reference for each sequence.

Entries in bold indicate sequences generated as part of this study

Results

The two NADH2 sequences generated for R. asterias (1089 and 1103 bp, respectively; Genbank accession numbers PX842716 and PX842717) were 99.57 to 100.00% similar to R. asterias sequences KY949160–KY949167 in Genbank (Ramírez-Amaro et al., Reference Ramírez-Amaro, Ordines, Picornell, Castro, Ramon, Massutí and Terrasa2018). The two NADH2 sequences generated for R. radula (738 and 1094 bp, respectively; Genbank accession numbers PX842718 and PX842719) were 99.23 to 99.57% similar to R. radula sequences KY909761–KY909763, KY909765, and KY909769 in Genbank (Vella et al., Reference Vella, Vella and Schembri2017).

Of the 45 Raja asterias specimens examined (total length: 30–60 cm), 19 were males (30–50 cm), and 26 were females (35–60 cm). Among these, 14 individuals were found to be infected with Acanthobothrium minus. In addition, 14 Raja radula specimens (total length: 30–47 cm), four were males (32–45 cm), and ten females (30–47 cm) were examined, of which six were infected with A. minus. This species is re-described below.

Taxonomic Summary

Family: Onchobothriidae Braun, 1900.

Genus: Acanthobothrium Blanchard, 1848

Acanthobothrium minus Tazerouti, Kechemir-Issad, and Euzet, Reference Tazerouti, Kechemir-Issad and Euzet2009

Type-host: Raja asterias Delaroche

Type locality: Cap Djinet (36°52′25″ N, 3°42′53″)

Additional localities: Tamentfoust (36.805545° N, 3.229776° E), Algiers (36.785000°, N 3.065278°E), Zemmouri El Bahri (36.783333° N, 3.600000° E), Cap Djinet (36.875833° N, 3.717500° E), Bouharoune (36.625556° N, 2.653611° E), and Jijel (36.816667° N, 5.766667° E)

Microhabitat: spiral valve, anterior and middle parts.

Material examined: 45 specimens.

Prevalence: 31.11% (14/45)

Intensity of infection: 1.5 A. minus per infected R. asterias

Abundance: 0.46 A. minus per sampled R. asterias

Additional hosts: Raja radula Delaroche

Additional localities: Zemouri El Bahri (36.783333° N, 3.600000° E) and Annaba (36.904167° N, 7.751944° E).

Material examined: 14 specimens.

Prevalence: 42.85% (6/14)

Intensity of infection: 3.0 A. minus per infected R. radula

Abundance: 1.28 A. minus per sampled R. radula

Description

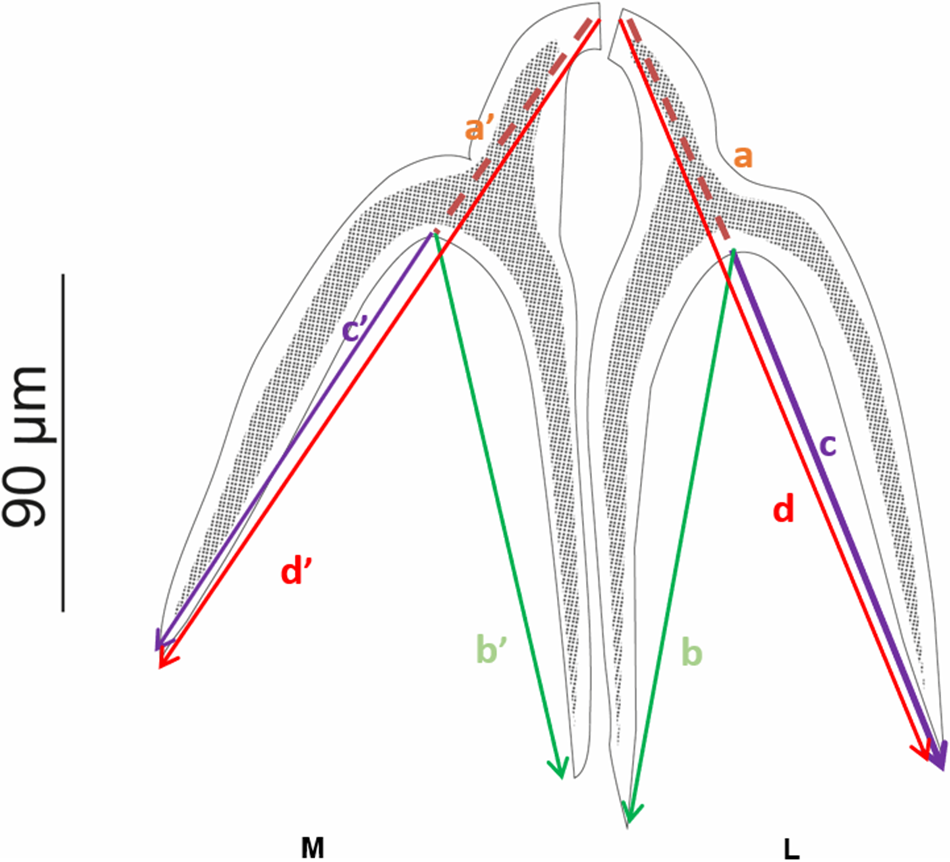

Measurements are based on 29 specimens, including 15 from R. asterias and 14 from R. radula, reported in micrometres (μm) and do not differ between specimen infecting R. asterias and R. radula (Table 2). These are presented as the mean, followed by the range ± standard deviation, with the number of specimens measured indicated in parentheses.

Table 2. Morphometric comparison of Acanthobothrium minus from Raja asterias and Raja radula. All measurements are in μm and are represented by the mean ± standard deviation (range, number of measurements).

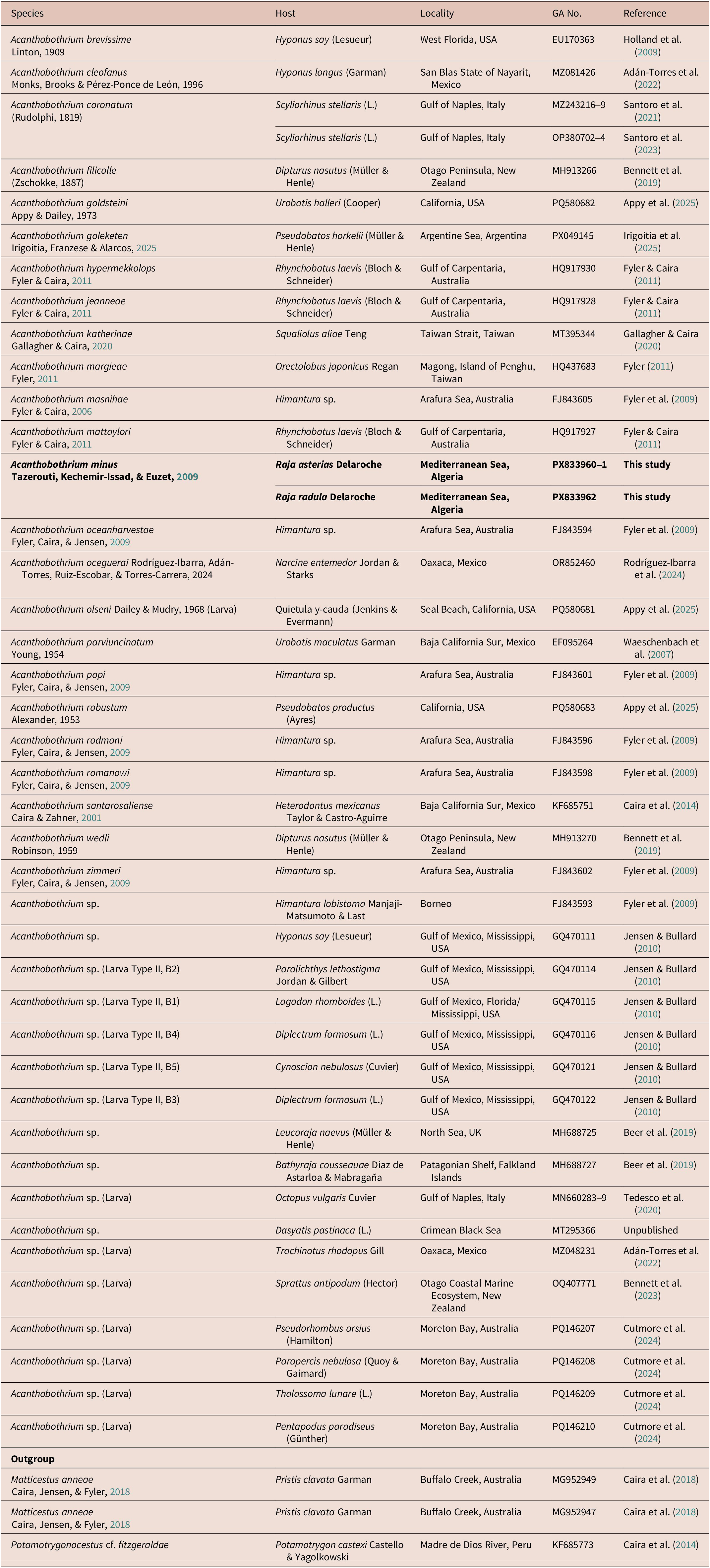

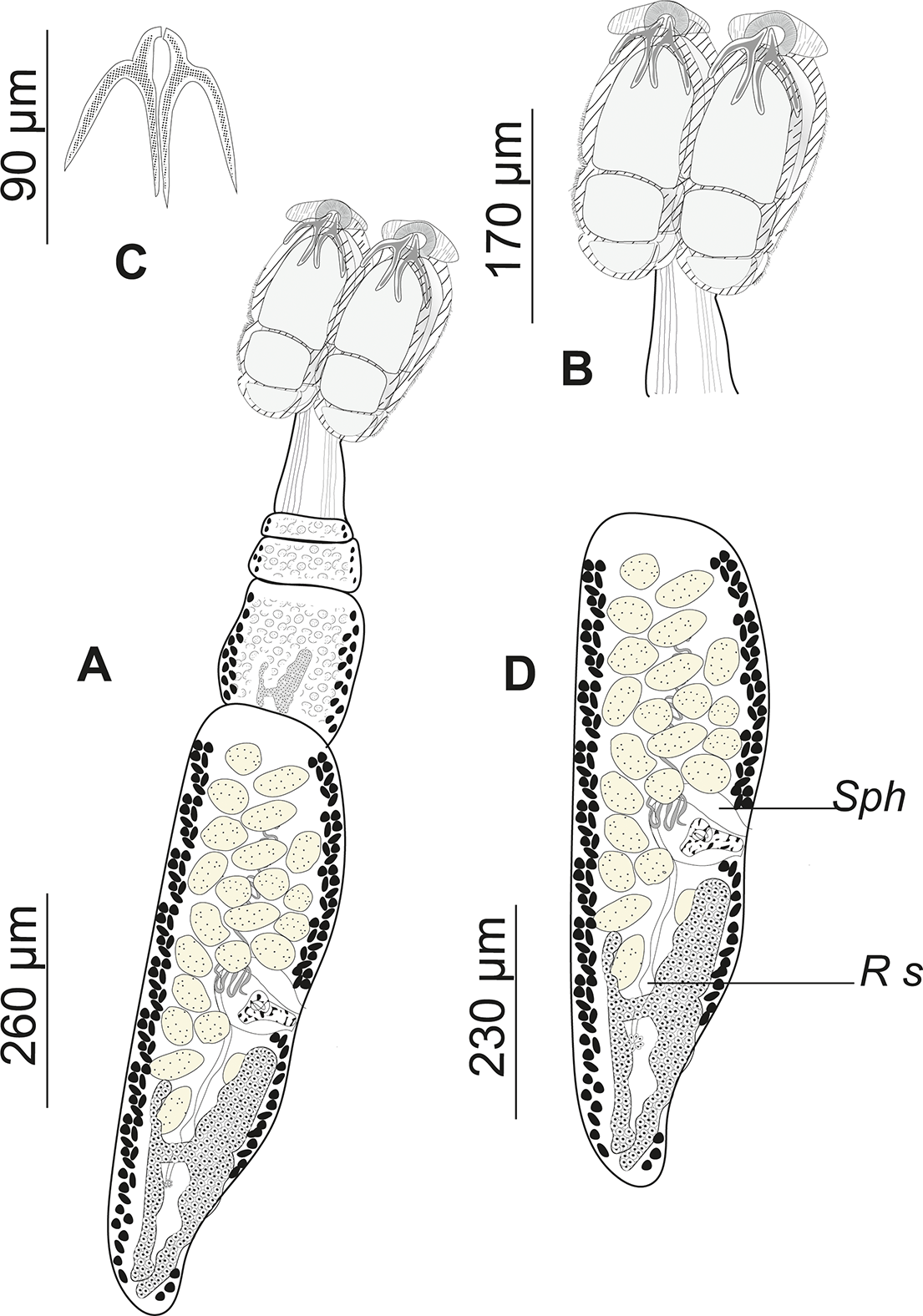

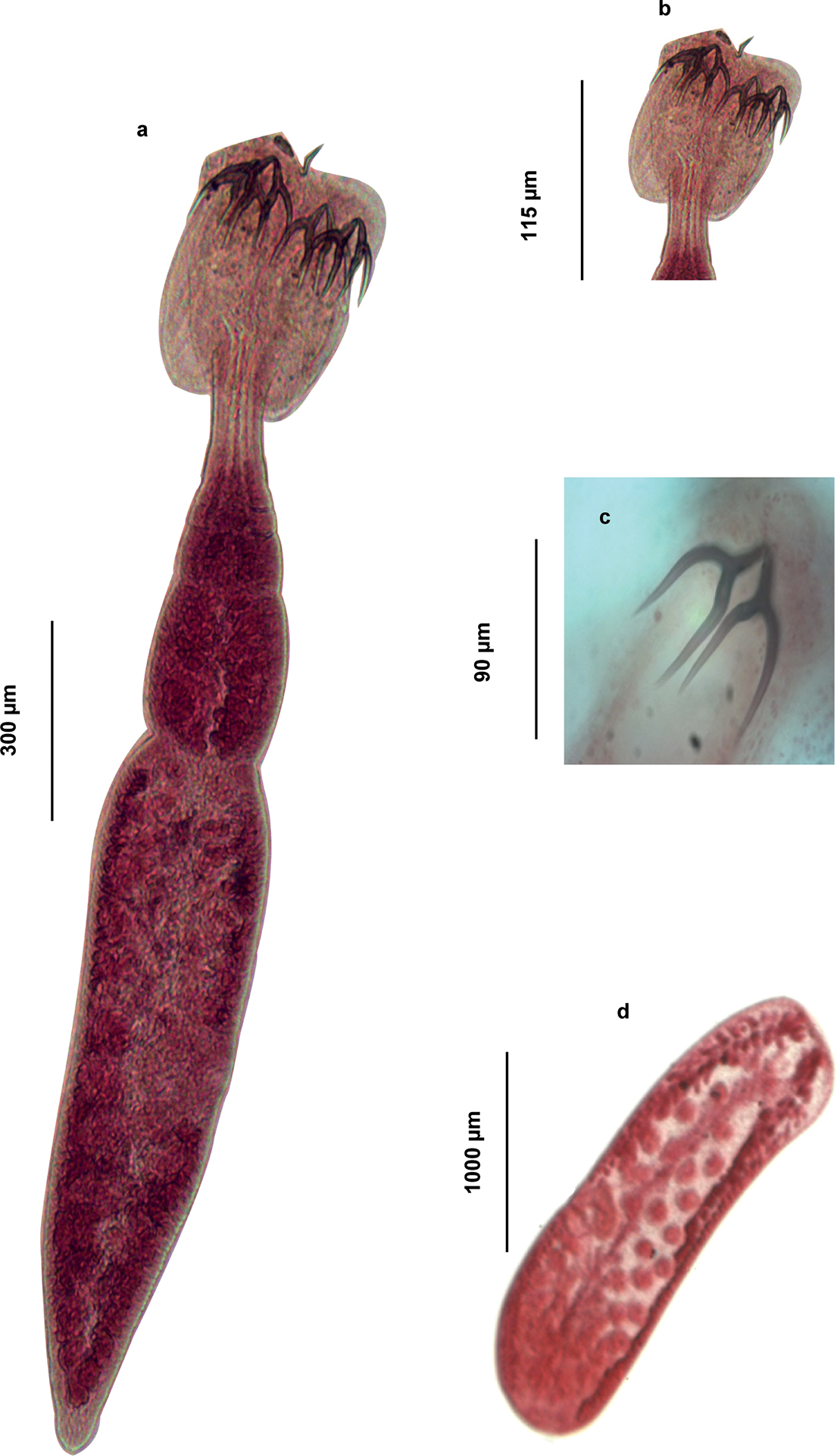

Adult worms (Fig. 3–4), very small. Body 1145 ± 310 (583.10–1861.95, n = 29) long, greatest width 155 ± 35 (78.51–214.80, n = 2). Scolex elongate 272 ± 31 (216.47–319.08, n = 29) long, 205 ± 30 (161.34–281.43, n = 29) wide. Scolex bears four sessile trilocular oval-shaped bothridia (Figs. 3 and 4) 229 ± 29 (176.46–290.38, n = 29) long, 92 ± 16 (68.56–132.77, n = 29) wide, two dorsal and two ventral. Proximal surface of each bothridium covered with microtriches. Bothridium subdivided into three loculi: anterior loculus measuring 128 ± 26 (88.53–189.04, n = 29), median loculus 51 ± 10 (35.47–85.92, n = 29), and posterior loculus 48 ± 11 (30.01–78.3, n = 29) long. Each bothridium is topped with a muscular plate 85 ± 65 (30.46–211.70, n = 29) long, 141 ± 70 (27.52–237.81, n = 29) wide, which includes an accessory sucker 43 ± 22 (21.40–108.79, n = 29) long, 63 ± 29 (17.25–122.61, n = 29) wide. Additionally, a pair of inverted Y-shaped hooks (Fig. 2) is present (n = 29). The hook measurements were taken and are presented following the formula of Euzet (Reference Euzet1959).

Figure 2. Measurements and nomenclature of the hooks of Acanthobothrium according to Euzet (Reference Euzet1959). L: lateral hook; M: median hook; a and a′ = length of the handle; b and b′ = length of the axial prong; c and c′ = length of the lateral prong; d and d′ = total length.

Figure 3. Drawings of Acanthobothrium minus ex Raja asterias (slide number NHMUK2026.1.19.5): (a) Complete fixed mature specimen; (b) scolex detail; (c) Y-shaped hooks; (d) terminal mature proglottis. Sph, sphincter; Rs, seminal receptacle.

Figure 4. Light micrographs of Acanthobothrium minus ex Raja asterias (slide number NHMUK2026.1.19.5): (a) Complete fixed mature specimen; (b) scolex detail; (c) Y-shaped hooks; (d) terminal mature proglottis.

Lateral hooks

![]() $ \frac{a=33.43\left(25.2-40.21\right)\hskip0.24em b=63.97\left(42.22-93.33\right)\hskip0.24em c=54.11\left(36.65-86.3\right)}{\mathrm{d}=90.55\left(68.55-123.97\right)} $

$ \frac{a=33.43\left(25.2-40.21\right)\hskip0.24em b=63.97\left(42.22-93.33\right)\hskip0.24em c=54.11\left(36.65-86.3\right)}{\mathrm{d}=90.55\left(68.55-123.97\right)} $

Median hooks

![]() $ \frac{a^{\prime }=37.32\left(\;26,61-46.65\right)\hskip0.24em b^{\prime }=63.01\left(37.23-96.84\right)\hskip0.24em c^{\prime }=61\left(39.57-95.63\right)}{\mathrm{d}^{\prime }=93.65\left(62.38-123.17\right)} $

$ \frac{a^{\prime }=37.32\left(\;26,61-46.65\right)\hskip0.24em b^{\prime }=63.01\left(37.23-96.84\right)\hskip0.24em c^{\prime }=61\left(39.57-95.63\right)}{\mathrm{d}^{\prime }=93.65\left(62.38-123.17\right)} $

Cephalic peduncle short 136 ± 51 (61.96–271.48, n = 29) long, 65 ± 15 (31.02–91.13, n = 29) wide. Strobila 699 ± 359 (68.56–1386.17, n = 29), euapolytic, consists of 4 (3–7) acraspedote proglottids, which elongate rapidly. The last proglottid is three to four times longer than it is wide. Immature proglottids 171 ± 91 (20.06–387.74, n = 29) long, 118 ± 40 (27.57–236.15, n = 29) wide. Mature proglottids 621 ± 268 (179.32–1166.94, n = 29) long, 142 ± 47 (11.85–214.80, n = 29) wide. Terminal proglottis 492 ± 199 (122.87–866.70, n = 29) long, 152 ± 35 (78.51–214.80, n = 29) wide. Genital pore lateral, alternating irregularly, and opening in the middle third of each proglottid. Its aperture is surrounded by a delicate muscular sphincter. In the male reproductive system, there are 23 (14– 27) spherical and globular testes of unequal size, 29 ± 9 (15.25–48.22, n = 29) long and 31 ± 8 (11.82 – 45.34, n = 29) wide, with the anterior ones being the smallest. Cirrus sac, arched backward 71 ± 29 (18.54–144.05, n = 29) long and 68 ± 32 (28.45 – 137.43, n = 29) wide, containing a highly coiled and everted cirrus. Ovary located in the posterior third of the proglottids, measuring 71 ± 26 (13.90–139.60, n = 25) long. Ovary H-shaped located in the posterior third of the proglottids, measuring 71 ± 26 (13.90–139.60, n = 25) long; anterior lobes longer than the posterior ones; anterior lobes asymmetrical, with the poral lobes being shorter 166 ± 84 (49.00–363.14, n = 25) than the aporal lobes 188 ± 85 (53.07–387.5, n = 25). Genital atrium present. The vagina opens into the atrium anterior to the cirrus sac. It is surrounded by a sphincter muscle near its atrial opening. The vaginal duct initially runs horizontally, bends at the median plane of the proglottis, and then descends dorsally to the ovarian isthmus, where it sometimes enlarges into a seminal receptacle. Vitelline follicles are arranged in two lateral bands, interrupted dorsally and ventrally at the level of the vagina and the cirrus sac. Eggs were not observed.

Remarks

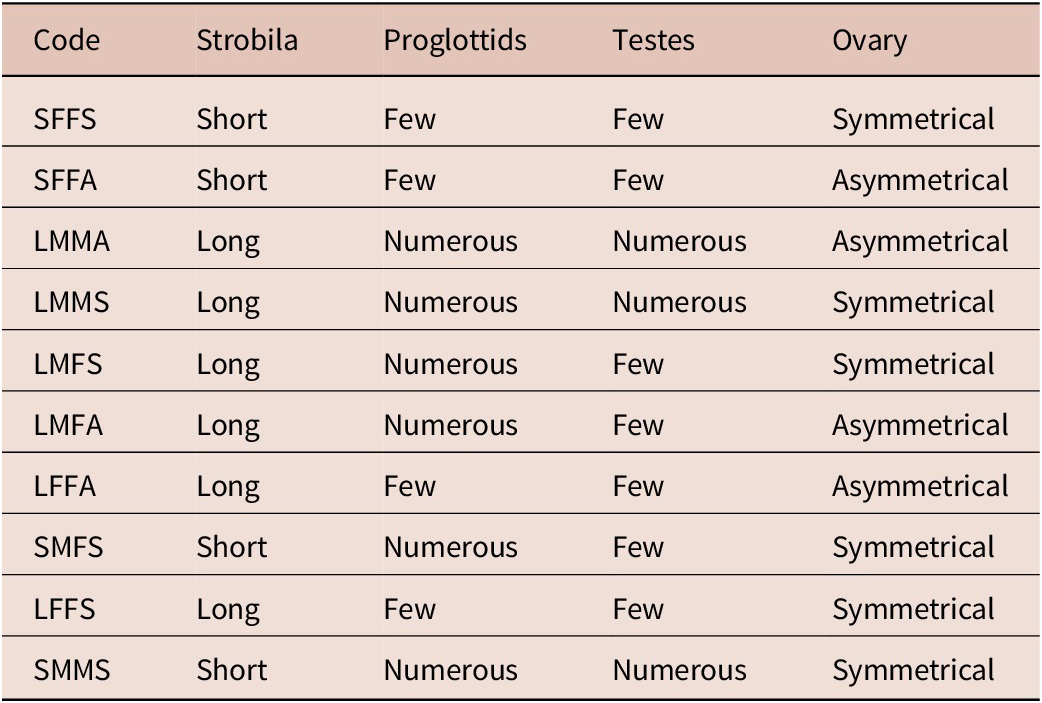

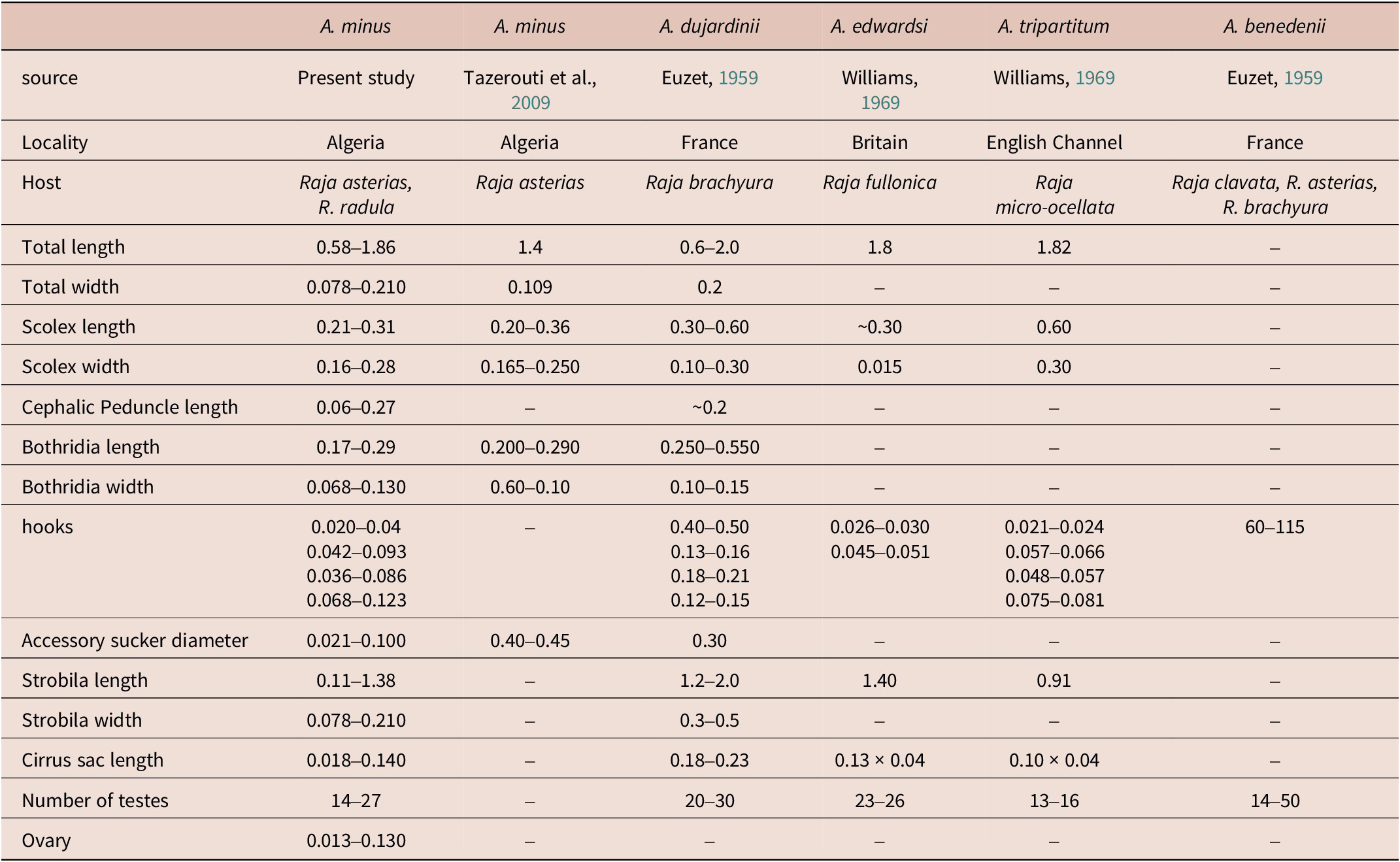

Tazerouti et al. (Reference Tazerouti, Kechemir-Issad and Euzet2009) classified A. minus as Category 2 (SFFA) (Table 3). According to the checklist by Zaragoza-Tapia et al. (Reference Zaragoza-Tapia, Pulido-Flores, Gardner and Monks2020), 44 Acanthobothrium species fall within this category. Among them, four species have been reported from the European coasts and the Mediterranean Sea: (1) A. dujardinii Van Beneden, Reference Van Beneden1850 ex R. brachyura Lafont; (2) A. benedenii Lönnberg, 1889 ex R. clavata; (3) A. edwardsi Williams, Reference Williams1969 ex Leucoraja fullonica (L.); and A. tripartitum Williams, Reference Williams1969 ex R. microocellata Montagu (Zaragoza-Tapia et al., Reference Zaragoza-Tapia, Pulido-Flores, Gardner and Monks2020). Based on Tazerouti et al. (Reference Tazerouti, Kechemir-Issad and Euzet2009), A. minus can be distinguished from other parasites belonging to the same category by a set of well-defined morphological characteristics, as well as by its host specificity and geographical distribution (Table 4). It differs from A. dujardinii in the absence of the distinctive bothridial morphology described by Baer (Reference Baer1948), which is characterized by a marked step between the edge of the median loculus and that of the posterior loculus; a feature not observed in A. minus. Furthermore, A. benedeni differs in the size of the hooks, the number of testes, and their arrangement characters that, in A. minus, exhibit consistent and well-defined values. Acanthobothrium edwardsii also shows notable differences: its hooks are smaller (78 vs. 100 μm in A. minus), and their morphology differs, with the axial prong being clearly longer than the lateral one, whereas in A. minus, the two prongs are subequal (Williams, Reference Williams1969). Finally, A. tripartitum is clearly distinguishable from A. minus by the complete absence of testes in the postporal field, a region that is well developed in A. minus (Williams, Reference Williams1969). Taken together, these features clearly differentiate A. minus from other Category 2 species reported in Rajidae of the Atlantic and Mediterranean, notably by its markedly smaller size (1–2 mm), reduced number of proglottids (3–7), and the distinctive morphology and dimensions of its hooks (97–100 μm).

Table 3. Character states used in the classification of Acanthobothrium species according to Ghoshroy and Caira (Reference Ghoshroy and Caira2001)

Table 4. Morphometric comparison between Acanthobothrium minus from the present study and other Acanthobothrium species (Category 2) from the Mediterranean.

All measurements are presented in mm.

Molecular data

Orthology of sequences obtained from Acanthobothrium specimens infecting R. asterias (n = 2; sequence length of 1757 bp) and R. radula (n = 1; sequence length of 747 bp) showed close affinity with other Acanthobothrium sequences, specifically with A. coronatum (Rudolphi, 1819) infecting Scyliorhinus stellaris (L.) from the Gulf of Naples, Italy (Genbank accession numbers MZ243216–MZ243219 in Santoro et al., Reference Santoro, Crocetta and Palomba2021; OP380702–OP38704 in Santoro et al., Reference Santoro, Bellisario, Fernández-Álvarez, Crocetta and Palomba2023) and larvae of an unidentified Acanthobothrium species recovered from Octopus vulgaris Cuvier from the Gulf of Naples, Italy (MN660283–MN660289, Tedesco et al., Reference Tedesco, Caffara, Gustinelli, Fiorito and Fioravanti2020) (99.06–99.53% sequence similarity) (Fig 5). The alignment consisted of 59 sequences (53 ingroup and three outgroup) and 606 bp.

Figure 5. Consensus tree based on Maximum Likelihood majority-rule inference for the genus Acanthobothrium Blanchard, 1848, showing our samples for Acanthobothrium minus Tazerouti, Kechemir-Issad & Euzet, Reference Tazerouti, Kechemir-Issad and Euzet2009, from both Raja asterias Delaroche and Raja radula Delaroche in bold. Nodal support is based on 100 bootstrap replicates with values <0.5 not shown.

Discussion

The genus Acanthobothrium Blanchard, 1848 currently comprises 215 species, making it the most species-rich, diverse, and widely distributed genus within the order Onchoproteocephalidea (Caira and Jensen, Reference Caira and Jensen2017; Maleki et al., Reference Maleki, Malek and Rastgoo2018; Rodríguez-Ibarra et al., Reference Rodríguez-Ibarra, Violante-González and Monks2023). Its hosts are predominantly batoids, approximately 15% of which (98 out of 637 species) are parasitized by these tapeworms, particularly within the families Rajidae and Dasyatidae (Caira et al., Reference Caira, Jensen, Ivanov, Caira and Jensen2017b; Rodríguez-Ibarra et al., Reference Rodríguez-Ibarra, Violante-González and Monks2023; Zaragoza-Tapia et al., Reference Zaragoza-Tapia, Pulido-Flores, Gardner and Monks2020). A recent metadata analysis further revealed that 14.9% of ray species have been reported as hosts to date (Zaragoza-Tapia et al., Reference Zaragoza-Tapia, Pulido-Flores, Gardner and Monks2020). It is also worth noting that it is very rare for Acanthobothrium species to parasitize more than one host species (Caira et al., Reference Caira, Jensen, Ivanov, Caira and Jensen2017b; Franzese and Ivanov, Reference Franzese and Ivanov2018; Fyler et al., Reference Fyler, Caira and Jensen2009; Golfetti, Reference Golfetti2018; Santoro et al., Reference Santoro, Crocetta and Palomba2021, Reference Santoro, Bellisario, Fernández-Álvarez, Crocetta and Palomba2023; Williams, Reference Williams1969). Together, the studies of Santoro et al. (Reference Santoro, Crocetta and Palomba2021, Reference Santoro, Bellisario, Fernández-Álvarez, Crocetta and Palomba2023) provide robust molecular and ecological evidence that A. coronatum displays a marked host specificity among Mediterranean elasmobranchs. By linking genetically identical larval and adult stages across different hosts, these studies support the involvement of intermediate or paratenic hosts and clarify trophic transmission pathways. Overall, they significantly enhance our understanding of the parasite’s infection dynamics, life cycle, and host associations within the Mediterranean ecosystem. However, it is common to find several species of Acanthobothrium in the same host (Fyler et al., Reference Fyler, Caira and Jensen2009; Maleki et al., 2013, Reference Maleki, Malek and Palm2019; Reyda and Caira, Reference Reyda and Caira2006), exhibiting essentially oioxenous specificity (sensu Euzet and Combes, Reference Euzet and Combes1980; Caira and Jensen, Reference Caira and Jensen2001). Their great diversity, combined with their marked morphological resemblance, makes their distinction challenging. Until now, this distinction has primarily been based on the analysis of morpho-anatomical characteristics, definitive hosts, and their localities (Goldstein, Reference Goldstein1967; Williams, Reference Williams1969). More recently, Ghoshroy and Caira (Reference Ghoshroy and Caira2001) established a method for grouping Acanthobothrium species based on a combination of morphometric criteria. This approach was developed using the 56 known species at the time, specific to elasmobranchs along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of North America. The system is based on the combination of four key morphological features (Table 3).

The combination of all these characteristics highlighted ten morphologically distinct categories of Acanthobothrium (Ghoshroy and Caira, Reference Ghoshroy and Caira2001) coded with four letters (Table 3). Focusing exclusively on morphology-based studies makes the identification of Acanthobothrium species increasingly challenging. This is because of the high diversity in this genus and the morphological similarities among different species within this genus are often indistinguishable. For instance, classifications based solely on ovarian symmetry may be unreliable, as this characteristic can vary within a single species (Franzese and Ivanov, Reference Franzese and Ivanov2018).

Several studies have further demonstrated that some taxa exhibit striking morphological similarities. For instance, A. cairae Vardo-Zalik & Campbell, 2011, and A. cleofanus Monks, Brooks & Pérez-Ponce de León, 1996, share comparable bothridial dimensions, as well as similar proportions of the scolex and peduncle. Both also present a relatively high number of proglottides, which places them within closely related taxonomic categories as outlined by Ghoshroy and Caira (Reference Ghoshroy and Caira2001). Despite these similarities, their diagnostic features reveal important distinctions. For instance, A. cairae possesses a significantly greater number of proglottides (approximately 268–491 in the original description) and exhibits larger anterior loculi/bothridia. Conversely, A. cleofanus is smaller in overall body length and contains fewer proglottides and testicles (Adán-Torres et al., Reference Adán-Torres, Oceguera-Figueroa, Martínez-Flores and García-Prieto2022). Therefore, molecular tools provide the most reliable and accurate means of confirming the identity of these parasites.

Moreover, 18 species of Acanthobothrium have been reported from 12 of the 23 valid species of Raja (Global Cestode Database, 2025); only five species have been recorded from Rajidae in the Mediterranean Sea, namely: (1) A. coronatum in Dipturus batis (L.); (2) A. dujardinii and (3) A. benedeni in R. clavata L.; (4) A. rajaebatis (Rudolphi, 1810) in D. batis; and (5) A. minus in R. asterias. Of these, A.benedenii, A. dujardinii, and A. edwardsi are Category 2 species that can be distinguished from A. minus (Table 4). Acanthobothrium rajaebatis is a Category 5 species (Zaragoza-Tapia et al., Reference Zaragoza-Tapia, Pulido-Flores, Gardner and Monks2020) and differs from A. minus in being much larger (50 to 60 mm long vs. 0.58 to 1.86 mm, respectively) with a larger scolex (1 to 1.5 mm vs. 0.21 to 0.31 mm long, respectively, and 0.8 to 1 mm vs. 0.16 to 0.28 mm wide, respectively), larger bothridia (1 to 1.2 mm vs. 0.17 to 0.29 mm long, respectively, and 0.4 to 0.5 mm vs. 0.068 to 0.130 mm wide, respectively), larger hooks (244 μm vs. 91 μm, respectively), more numerous testes per proglottis (58 to 85 vs. 14 to 27, respectively), more numerous proglottids (80 to 120 vs. 4 to 7, respectively), and a larger cirrus sac (300 to 325 μm vs. 0.018 to 0.140 μm, respectively) (Euzet, Reference Euzet1959; Table 4). Acanthobothrium coronatum is a Category 4 species (Zaragoza-Tapia et al., Reference Zaragoza-Tapia, Pulido-Flores, Gardner and Monks2020) and differs from A. minus in being much larger (96 to 148 mm long vs. 0.58 to 1.86 mm, respectively) with a larger scolex (0.89 to 1.22 mm vs. 0.21 to 0.31mm long, respectively, and 0.77 to 1.05 mm vs. 0.16 to 0.28 mm wide, respectively), larger bothridia (0.63 to 0.97 mm vs. 0.17 to 0.29 mm long, respectively, and 0.30 to 0.47 mm vs. 0.068 to 0.130 mm wide, respectively), larger hooks (238 μm vs. 91 μm, respectively), more numerous testes per proglottis (88 to 112 vs. 14 to 27, respectively), more numerous proglottids (312 to 373 vs. 4 to 7, respectively), and a larger cirrus sac (365 to 674 μm vs. 0.018 to 0.140 μm, respectively) (Santoro et al., Reference Santoro, Crocetta and Palomba2021; Table 4).

The phylogenetic results presented herein (Fig. 5) placed A. minus in a well-supported clade (bootstrap nodal support of 98) which includes other Acanthobothrium 28S sequences from the Mediterranean, i.e., those from A. coronatum and larvae recovered from O. vulgaris (Santoro et al., Reference Santoro, Crocetta and Palomba2021, Reference Santoro, Bellisario, Fernández-Álvarez, Crocetta and Palomba2023; Tedesco et al., Reference Tedesco, Caffara, Gustinelli, Fiorito and Fioravanti2020). The clade includes also a sequence for an undescribed species recovered as a larva infecting Diplectrum formosum from the Gulf of Mexico (Jensen and Bullard, Reference Jensen and Bullard2010). However, low nodal support (<50) suggests that its true placement might lie outside of this clade. The regional grouping of these sequences from relatively distantly related definitive hosts (the shark S. stellaris and the skates R. asterias and R. radula) supports evolution of this elasmobranch-Acanthobothrium association in the Mediterranean through host switching due to shared ecological features of the hosts, followed by speciation by isolation (see Beer et al., Reference Beer, Ingram and Randhawa2019). However, confirming this hypothesis would require sequence data for the other Acanthobothrium species from the Mediterranean.

Consistent with Rodríguez-Ibarra et al. (Reference Rodríguez-Ibarra, Adán-Torres, Ruiz-Escobar and Torres-Carrera2024) but conversely to Santoro et al. (Reference Santoro, Crocetta and Palomba2021) and Irigoitia et al. (Reference Irigoitia, Franzese, Alarcos, Arredondo and Timi2025), our phylogenetic results do not include A. wedli Robinson, 1959, A. santarosaliense Caira & Zahner, Reference Ghoshroy and Caira2001, and the two larval Acanthobothrium spp. within the well-supported clade which includes A. coronatum, A. minus, and larvae recovered from the common octopus (Fig. 5). These inconsistent results are most likely attributable to the relatively few Acanthobothrium species for which molecular data are available (11% of described species) with the possibility that published phylogenies for the genus may not reflect the evolutionary history of the genus. The remarkable species richness of the genus contrasts sharply with the limited molecular data available for most of its members (Adán-Torres et al., Reference Adán-Torres, Oceguera-Figueroa, Martínez-Flores and García-Prieto2022). To date, only 24 named species have associated molecular sequences: three with both 28S and 18S genes, 20 with only 28S sequences, and one with the cox I gene (Acanthobothrium cf. terezae Rego & Dias, 1976; unpublished data). Additionally, molecular data exist for 15 unnamed Acanthobothrium species. There is a paucity of studies on the multiple congeners observed within each host (Ghoshroy and Caira, Reference Ghoshroy and Caira2001). However, the few that have, which included molecular data, suggest that these congeners infecting a common host represent more than one clade (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Jorge, Poulin and Randhawa2019; Fyler and Caira, Reference Fyler and Caira2011; Fyler et al., Reference Fyler, Caira and Jensen2009). The absence of a current phylogenetic framework encompassing most Acanthobothrium species prevents determining whether these are exceptions rather than the norm.

Furthermore, consistent with Rodríguez-Ibarra et al. (Reference Rodríguez-Ibarra, Adán-Torres, Ruiz-Escobar and Torres-Carrera2024), no pattern was observed regarding the taxonomic categories outlined in Ghoshroy and Caira (Reference Ghoshroy and Caira2001). In fact, the closest relative to A. minus (Category 2) in our phylogenetic framework was A. coronatum (Category 4) (Fig. 5). This might reflect the paucity of sequence data due to a lack of depth in taxonomic sampling for Acanthobothrium. Alternatively, this might simply reveal that these taxonomic categories are a useful guide for morphological comparisons between taxa by focusing on similarities in combinations of morphological characters and are not correlated with true phylogenetic relationships (Ghoshroy and Caira, Reference Ghoshroy and Caira2001).

In conclusion, future studies should integrate both molecular and morphometric data when describing or re-describing species. Combining these complementary approaches enhances the accuracy and robustness of taxonomic identifications, facilitates reproducibility, and allows for more comprehensive assessments of biodiversity. Furthermore, deposition of voucher specimens, e.g., hologenophores sensu Pleijel et al. (Reference Pleijel, Jondelius, Norlinder, Nygren, Oxelman, Schander, Sundberg and Thollesson2008), in reputable and accessible repositories is strongly encouraged, ensuring that material is preserved for future examination and verification. Such practices strengthen the reliability of species descriptions, support ongoing and future research, and contribute to the long-term integrity of taxonomic knowledge (e.g., DiEuliis et al., Reference DiEuliis, Johnson, Morse and Schindel2016; Harmon et al., Reference Harmon, Littlewood and Wood2019; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Leslie, Claar, Mastick, Preisser, Vanhove and Welicky2023).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the assistance of Elísabet Guðmundsdóttir for supporting SO with DNA extractions and PCR. We thank two anonymous reviewers for providing constructive feedback to improve this manuscript.

This research was supported by Direction Générale de la Recherche Scientifique et du Développement Technologique (DGRSDT, Algiers, Algeria).

Financial support

This study was supported indirectly through a grant to HSR by the Eggerts Fund (Eggertssjóður), hosted at the University of Iceland, and the University of Iceland Contribution to Teachers’ Research Fund to HSR.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standard

Fish utilized in this were sourced from commercial landings, hence no ethics protocols were required.