Introduction

In electoral authoritarian systems (Schedler Reference Schedler2013), within-system opposition parties face a difficult balancing act. They must grapple with the dilemma of “dual commitment” to both the regime and their voters (Bondarenko Reference Bondarenko2023), professing sufficient systemic loyalty to avoid losing resources and access (Gel’man Reference Gel'man2013; Golosov Reference Golosov2022), whilst expressing enough opposition to retain their niche in the electoral market.

We contribute to a growing body of research that studies the dynamic interactions between regime, systemic opposition, and society (Smyth Reference Smyth2021). Systemic opposition parties can be advantageous to electoral authoritarian stabilisation (Semenov Reference Semenov2017), giving flexibility in ballot management, and additional electoral legitimacy to regimes (Smyth and Turovsky Reference Smyth and Turovsky2018). They can also play a real, if limited, role in providing “early warnings” to the regime: voters are still relatively more likely to vote for opposition parties in regions where they perceive the governing party to be failing (Panov and Ross Reference Panov and Ross2023).

Comparative research on autocratic regimes also suggests, however, that regimes are also keen to avoid too much success for the systemic opposition parties. In the ‘third wave’ of democratisation, for instance, it was often such systemic opposition parties that were at the forefront of regime change, such as in Mexico (Linz & Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996; Ishiyama and Rybalko Reference Ishiyama and Rybalko2023). For both government and opposition, therefore, there is a complex balancing act to be performed between co-option and confrontation.

We contend that during the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020–2022 the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF) fulfilled a stabilising role, pragmatically balancing ‘loyalty’ and ‘voice’ to challenge Covid-19 governance measures. We interpret this as the latest in a series of such oscillations between loyalty and voice that the CPRF has performed over the last two decades.

Concepts and previous analysis

Electoral authoritarian regimes imitate the trappings of liberal democracy, but skew the level playing field (Levitsky & Way 2010). In Russia, aided by frequent electoral reforms, limited media freedom, and a weak opposition, the pro-Kremlin United Russia (UR) party has won a substantial parliamentary majority at every State Duma election since 2007. The stable cartel of other parliamentary parties—the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF), Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) and A Just Russia (For Truth) (AJR-FT), joined from 2021 onwards by ‘New People’ (NP)—represent the “second class, licenced, parties” of which Sartori (2005: 205) spoke. They provide the regime with the appearance of competition without posing a genuine threat. There are, however, recognisable differences between the policy positions and voter perceptions of systemic opposition parties. Compared with the others, the CPRF is less likely to tone down its criticism, and less likely to submit to co-option through patronage than other systemic oppositions parties (Dollbaum Reference Dollbaum2017; Panov and Ross Reference Panov and Ross2023).

We contend that, even in an electoral autocracy, systemic opposition strategically selects stances of “loyalty” and “voice” (in contrast to the “exit” of anti-systemic opposition) (Hirschman 1970; Isaacs 2023). For the systemic opposition, benefits from “loyalty” include continued patronage, state funding and national visibility. When it comes to “voice”, systemic opposition can win more prominence in regions with protest potential. In the period studied here (2020–2022), the CPRF balanced these two stances to its advantage. It forced the Kremlin into a tactical retreat on requiring QR codes to access public locations during the Covid-19 pandemic (Forbes.ru 2021) and in some regions—such as the Republic of Khakassia—cast itself as a radical alternative to the party of power (Kapustin 2023). On the other hand, it acquiesced in repressive legislation that added to the regime’s “menu of manipulation” (Schedler Reference Schedler2002)Footnote 1 and—on the face of it—went against its own interests to retain some rights to dissent and protest.

Key to understanding this pragmatism are two dilemmas. First, the aforementioned “dual commitment” problem means that systemic opposition parties have to balance their roles as co-opted regime stabilisers and mobilisers of opposition to it. Second, the party leadership has to balance the rewards of co-optation with the potential challenge from the party’s activist base if it is too timid in its opposition (Buckles Reference Buckles2019). The moribund nature of the party’s central leadership—Gennadii Zyuganov has been leader of the party for over three decades and is nearly 80—is in stark contrast to its youthful and energetic regional party leaders, who are far more inclined to radical oppositionist stances.Footnote 2

The context: the Kremlin’s pre-epidemic difficulties and the “system reset”.

Vladimir Putin’s comfortable 2018 presidential election victory, in which he won the support of 77.5% of the 67.5% who voted, was quickly soured by unpopular pension reforms announced in the summer of 2018. These led to protests and a decline in the opinion poll ratings of the president and UR (Vedomosti 2019). The CPRF, which voted against the reform in the State Duma, was at the forefront of these street actions (Logvinenko Reference Logvinenko2020), making gains in the 2018 regional elections (Solntseva 2020).

Against this unfavourable backdrop, the Kremlin decided upon a system reset. The first half of 2020 saw sweeping constitutional changes, and new repressive laws were passed in December 2020 that reduced key freedoms of assembly, speech, and association (BBC Russian 2020). The following year saw repression against the non-systemic opposition, mainly against the so-called extremists of Alexey Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation (Tétrault-Farber 2021), but also segments of civil society designated as “foreign agents” or “undesirable organisations”.

The Covid-19 pandemic interacted with and in some cases precipitated these developments. Though the first wave of the pandemic was not devastating in terms of infected and dead, it brought serious economic hardship and delayed the constitutional changes. In 2021, low vaccine uptake and resistance to basic measures taken to stop the spread led to government plans to mandate QR codes across the country, which in turn sparked protests and were dropped before Russia edged towards its war in Ukraine in early 2022.

Each of these developments provided a challenge to the CPRF, which had to balance stances of “loyalty” and “voice”. In general, we argue that its strategic choices not only enhanced its own relative position within the system, but also provided some leeway to the regime itself. In the rest of the article, we examine four particular stances and map out the CPRF’s strategic choices between the two options on each occasion. The material used for this study is a triangulation of news reports, State Duma voting records, official electoral statistics and secondary analysis of the individual-level data from a 2021 national representative survey.

CPRF 2020–2022: loyalty and voice

The constitutional amendments and early Covid-19 measures

Across the first two waves of the pandemic in 2020, the CPRF did not really voice any clear alternatives on pandemic issues and offered only rather muted opposition on the constitutional reforms. The party abstained on the amendments in parliament, and though it later called on its voters to oppose the reforms in the summer 2020 referendum (Interfax 2020a; RBC 2020a; Zyuganov 2020), albeit without much active campaigning to this effect. In other words, whilst stopping short of “loyalty”, it certainly did not forcefully use “voice” as an alternative. Its ambivalence mirrored that of its own supporters. A poll from VTsIOM (2020) showed 43% of CPRF voters would vote in favour, 39% against. More radical opposition would move the party into a dangerously anti-regime stance for little electoral reward. Moreover, the status quo was the 1993 Constitution that the CPRF had spent most of the previous three decades criticising. Outright vocal opposition to the amendments would have been a difficult position to sustain, especially as the regime’s PR campaign for the amendments focused on patriotic and traditional values (Blackburn & Petersson Reference Blackburn and Petersson2021: 298) that were the CPRF’s own flagship policies.

Reaction to protests: Khabarovsk, Belarus, and Navalny

Another key political development in 2020 related to the greatest fear of the Kremlin: social unrest and “colour revolutions”. In July 2020, protests erupted in Khabarovsk over the removal of the popular LDPR governor Sergei Furgal and his arrest on attempted murder charges.Footnote 3 In August 2020, protests in Belarus surrounding the presidential elections briefly opened the possibility of even the Lukashenko regime falling. In addition, the putative leader of the non-systemic Russian opposition, Alexey Navalny, fell seriously ill on a flight from Tomsk to Moscow and was transported to Germany for medical treatment. His team claimed he was poisoned; pro-Kremlin media suggested a Western intelligence operation to blacken Russia’s reputation.

Once again, the CPRF balanced “voice” and “loyalty”, in line with perceived opportunities to capitalise on and dangers to avoid. Zyuganov quickly came out in support of the Khabarovsk protests, which he considered to be caused by the Kremlin’s “brazen policies” of neglect (SV Pressa 2020). CPRF members played an active role in the protests and were among those detained and fined (RBC 2020b). The CPRF sought to capitalise on the difficult situation faced by the LDPR party, whose leader Vladimir Zhirinovsky had decided on “loyalty”—but to the regime, rather than his LDPR colleague, Furgal. The CPRF position on Khabarovsk remained consistent and may have reflected knowledge of polling data showing 43–47% support for the protests across the population (Levada Center 2020).

On the issues of Belarus and Navalny, however, CPRF went to the opposite extreme. On Belarus, Zyuganov declared it an “attempt at state overthrow” by “pro-Western forces” in league with “nationalist elements in Belarussian society” (RBC 2020c). He demanded measures of support for Lukashenko to wipe out this “orange revolution” (Interfax 2020b). Similarly, he dismissed Navalny’s poisoning in September 2020 as an “international provocation” against Russia set up by “Anglo-Saxons”—mirroring the regime’s insult of choice for the Western “other” (RIA 2020). He dismissed Navalny as a “Western product”, trained and in the pay of “globalists” (RLine 2021).

Reacting to repressive new laws

In the winter of 2020, the Kremlin proposed new repressive laws, ostensibly depicted as measures to prevent foreign interference in the upcoming Duma elections (Kremlin.ru 2020). One may have expected stiffer CPRF resistance to these restrictions, but the picture was again mixed. It remained “loyal” on a bill expanding the definition of “foreign agents” to individuals and increasing the punishment to 5 years in jail: only one CPRF deputy asked a technical question, which failed to clarify the muddy waters of how and when the foreign agent law would be applied,Footnote 4 and ultimately it voted in favour. Its opposition to a new law restricting demonstrations and protests was muted,Footnote 5 as also in the passing of a bill on “Internet slander”.Footnote 6 Towards the “voice” end of the spectrum, however, CPRF objections did help alter a bill restricting YouTube and Facebook,Footnote 7 and its resistance was clearer to a controversial bill on education, which the CPRF criticised as vague and likely to be harmful to scientific education. The party voted against it, but could not stop its passage.Footnote 8

These episodes reveal the essential powerlessness of the CPRF in face of a UR majority in the Duma. On the other hand, by strategically choosing which bills to support and which to acquiesce with, it once again was able to profile itself on key issues. Given the lack of radical actions to resist, CPRF deputies perhaps did not believe the new laws would be used against them, but only against anti-systemic liberals. Their lack of opposition to repressive laws—or the regime’s crackdown on Navalny—may have reflected a perceived gain: the liquidation of Navalny’s Fund Against Corruption (FBK) could transfer anti-systemic votes to the CPRF.

Resisting COVID-19 measures in 2021

On Covid-19, the CPRF unambiguously chose “voice”. As another wave of the virus kicked in in early 2021, there were calls for a harder line on taking the vaccine. Some regional authorities made strict rules about using QR codes to certify vaccine status and thus access to public buildings and events (similar to the Covid-19 passports in the European Union). Others mandated employers to ensure the vaccination of their employees. As was the case elsewhere, such measures were controversial. With trust levels in the safety of the relatively new vaccine low (Levada Center 2021d), it relied on compliance in a matter that, previously, would have been considered a matter of individual choice. Here, the CPRF showed strong resistance, in cooperation with Left Front, the Russian Orthodox Church, and the “For a New Socialism” movement, who joined to demonstrate against QR codes in Tyumen as early as March 2021 (Nakanune.ru 2021). This was a paradoxical case of an illiberal opposition uniting to defend the rights of citizens to choose.

The last quarter of 2021 saw a deadly fourth wave of Covid-19 that reinforced the idea that mandated vaccination was the best way to solve the crisis (Comnews.ru 2021). On 12 November, the Russian Government sent two bills to the State Duma to make QR codes mandatory nationwide. The CPRF led the resistance to the bills. Central Committee member Sergey Obukhov claimed the bills would “segregate society”, “violate the constitutional rights of citizens” and represent an “enforced form of what is supposed to be voluntary vaccination” (BBC Russian 2021a). From 15 November, small-scale protests (60–200 people) broke out across many parts of Russia (TJournal.ru 2021). On 19 November, the office of Rospotrebnadzor in Volgograd, the agency pushing the QR law, was stormed (BBC 2021b).

Though some of these individual protests were unsanctioned or unrelated directly to the party, it rode the bandwagon of protest, organising its own protest actions against the codes around Moscow region and elsewhere (CPRF 2021). The CPRF were, from this point on, the clear leaders of the anti-vaccination sentiment in Russian politics. When the QR-code legislation was withdrawn from the Duma’s consideration, it was clear that the CPRF’s “voice” had ridden a wave of anti-government sentiment around Covid-19 governance.

Increasing public support for CPRF during the Covid-19 pandemic

The September 2021 State Duma Election resulted in the CPRF’s second-best result in two decades. Whilst still below its 1990s peaks, its vote share increased from 13.3% in 2016 to 18.9% in 2021. Polling data indicate this increased share was down to two factors: (1) demographic shifts in voting for CPRF; (2) approval of CPRF opposition to Covid-19 governance. These two factors are related, connected through the CPRF’s balancing of “voice” and “loyalty”.

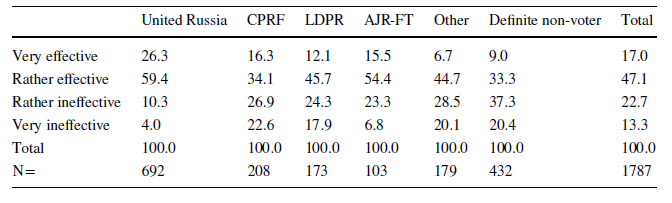

The CPRF had a favourable landscape when it came to mobilising against Covid-19 restrictions. Three months prior to the election, its voters were the most negative in their assessment of how the authorities had handled Covid-19 in summer 2021 (Table 1). In other words, the CPRF was pushing at an open door, tapping into latent anti-authority sentiment that correlated with scepticism about Coronavirus as well as other matters. Its decision to adopt a strategy of “voice” in opposition to mandatory vaccination and QR codes was consistent with its domestic policy stance since 2018: to raise “voice” about issues where the authorities were perceived as having failed, whilst remaining “loyal” on issues over which there was a broad consensus (such as the constitutional amendments, and later the war in Ukraine).

Table 1 How do you assess the effectiveness of the federal authorities (President and the Russian government) in the fight against coronavirus?” (% respondents, excluding “don’t know”)

(Source: Levada Center 2021a)

Continuing a trend seen in other recent elections, the CPRF moved from being the voice of the rural rustbelt to that of urban opposition, where the liberals had previously had their strongest foothold (March 2002: 168–9; Hutcheson Reference Hutcheson2018). Its electorate had a wider age spread than previously, indicating that it moved out of its previous niche as the party of nostalgic pensioners (Levada Center 2021a; Levada Center 2021b; Levada Center 2021c). The CPRF pushed LDPR aside to become the main face of within-system opposition, as vocal advocates for the less prosperous (Panov and Ross Reference Panov and Ross2023) and the party of choice for the protest voter. A key correlate of the CPRF’s increased 2021 vote share was whether a region or city had experienced significant protests in 2018–2019 over the aforementioned pension reform (Zavadskaya and Rumiantseva Reference Zavadskaya and Rumiantseva2022).

This is a pattern seen in other electoral authoritarian regimes: systemic opposition parties often consolidate the protest vote from other opposition movements, rather than taking on the governing party directly (White Reference White2020). As such, they pose no inherent danger to the regime itself, but are able to use strategic balancing of loyalty to the regime and voice against it to benefit from continued patronage, as well expanding their own influence at each other’s expense.

Conclusion

The period of 2020–2022 demonstrated how party politics operated, and how the CPRF could—in peacetime—carve out a role balancing loyalty and opposition. United Russia, the ruling party, showed itself to be inflexible and unwilling to take any risks. The Kremlin’s approach to pandemic governance produced fault lines in the systemic opposition, with the CPRF taking the lead in criticising Covid-19 governance, and the other parliamentary parties staying closer to the government line. In doing so, the CPRF showed the kind of underappreciated influence that systemic opposition can have in guiding and at times moderating decision-making in electoral authoritarian regimes’ domestic politics.

Though the Kremlin’s decision to launch the invasion of Ukraine just as the Covid-19 pandemic was ending makes it impossible to know if the progress made by the CPRF could have led to a longer-term wave of contentious politics in Russia (the party has hitherto been fully “loyal” on all war-related matters), the story of CPRF activities in 2020–2022 shows that systemic opposition exists in a sophisticated symbiosis with the authorities. Opposition can simultaneously be real but also, paradoxically, regime-stabilising, providing channels of feedback and a controlled venting of discontent that are crucial to the preservation of regime stability. Switching between “voice” and “loyalty” in 2020–22 allowed the CPRF to use the actions of the Kremlin and regional governors as a foil against which to mobilise. Moreover, the systemic opposition parties appeal to different segments of the electorate. Thus, our analysis of pandemic politics in Russia allows fresh conclusions not only on the evolution of the Putin regime (2018–2022) but also on the nature of electoral authoritarianism and personalist autocracies in general.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University.