Highlights

-

Geographic and population modelling were conducted to determine access to endovascular therapy (EVT).

-

In total, 13.57% and 42.66% of the Canadian population do not have access to EVT within 6 and 3 hours.

-

A door-in-door-out time (DIDO) time of 45 minutes can ensure that an additional 6.0 million people have access within 3 hours.

Introduction

Endovascular treatment (EVT) is proven to be highly efficacious for ischaemic stroke patients with a large vessel occlusion. Reference Goyal, Demchuk and Menon1,Reference Goyal, Menon and Van Zwam2 Additionally, the effectiveness of EVT has been shown to be highly dependent on time Reference Menon, Sajobi and Zhang3,Reference Saver, Goyal and Van der Lugt4 with every 10 minutes of earlier treatment resulting in a gain of 39 days of disability free life. Reference Kunz, Hunink and Almekhlafi5 Furthermore, there are considerable cost savings to the health system with every 10 minutes of earlier treatment resulting in $10,593 in health care value. Reference Kunz, Hunink and Almekhlafi5 This makes timely access to EVT one of the most significant factors to ensure good outcomes and health system cost avoidance. EVT is offered at stroke centres that are typically located in urban areas due to the specialised expertise and equipment that are required. Patients that arrive at a stroke centre that is only capable of intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) treatment need to be transferred to an EVT-capable stroke centre.

Canada has a vast geography with a population that is dispersed across large areas. Canada has 205 stroke centres, of which 178 are only capable of providing IVT and 27 are EVT-capable hospitals. Reference Adewusi, Demchuk and Stotts6 This includes small urban locations that are a considerable distance from large urban centres and rural populations. This geography makes access to EVT particularly challenging, as eligibility for EVT declines with time, and access within 6 hours is critical to ensure access to EVT and optimal outcomes. Even more challenging is access to EVT within the golden 3 hours from onset for acute stroke, given Canadian geography. Although the Canadian population is largely centred in urban cities that are located along the southern regions of Canada, the population that cannot access EVT within 6 and 3 hours is not known.

EVT access for populations that are not within the catchment area of the EVT stroke centre must rely on efficient transfer from an IVT-only centre. Transfer efficiency is typically measured using door-in-door-out (DIDO) time, which is the time from when a patient arrives at the IVT-only stroke centre to when they leave that centre. Fast DIDO times are being increasingly scrutinised and improved to ensure optimal outcomes for patients eligible for EVT. Reference Stamm, Royan, Giurcanu, Messe, Jauch and Prabhakaran7– Reference Royan, Stamm, Giurcanu, Messe, Jauch and Prabhakaran14 Canadian data show that median DIDO times are currently as high as 155.5 minutes (IQR: 127.0–173) in Atlantic Canada Reference Kamal, Cora and Alim15 and 100 minutes (IQR: 73–144) in Alberta. Reference Kamal, Jeerakathil and Demchuk16 However, the data from Alberta were a small sample of less than 100 patients and may not represent actual performance.

This study aims to conduct geographic modelling to determine what areas and size of population do not have access to an EVT-capable centre within 6 hours and 3 hours from onset. Geographic modelling has been conducted in Ontario previously, but it did not consider transfer times from IVT-only centres. Reference Kapral, Hall and Gozdyra17 Therefore, this will be the first known study that will identify areas of poor access and quantify the population size without access to EVT in Canada. This modelling study includes the entire population of Canada and all regions of Canada.

Methods

Geographic modelling was conducted to provide visuals and quantification of access to reperfusion treatment with both IVT and EVT for all potential pick-up locations across Canada. The first step for the geographic modelling was to place all stroke centres on a map with their treatment capability: IVT-only or EVT-capable. All areas of Canada were then divided into small grid sections that were dependent on the total area of the province or territory, and constrained by performance and hardware limits. Due to the large size of Canada, each province or territory was divided separately; for each grid section, the population was retrieved, drive times were obtained from each grid section to the closest stroke centre, and the drive time from each IVT-only centre to the EVT-capable centre was also obtained. Cross-border transfer was allowed for all three territories, and PEI, since there is no EVT-capable centre in these provinces/territories. Specifically, the two IVT-centres in PEI, Queen Elizabeth Hospital and Prince County Hospital, transfer to Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre in Halifax for EVT; Stanton Territorial Hospital in the Northwest Territories transfers to University of Alberta Hospital in Alberta; Qikiqtani General Hospital in Nunavut transfers to The Ottawa Hospital; and Whitehorse General Hospital in the Yukon transfers to Vancouver General Hospital. It should be noted that the transport time between these hospitals used air travel time. Although there are some cross-border transfers permitted in Canada, health care is delivered at the provincial level, and transfers are typically limited to within the province. Due to the difference in sizes of the provinces/territories, the size of each grid section was dependent on the size of the region due to the computing limitation required to collect all the population and drive time data for all the grid sections. All attempts were made to make the smallest size of the grid sections that could reasonably be executed by the hardware constraints. A grid size of 3x3 km would have a drive time from the centre of the grid section to the hospital; therefore, the drive time to travel ±1.5 km (typically 1 minute) to the edge of grid is the error that this size of the grid (3x3km) would result. Regions under 75,000 km2 (Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick) were divided into 3x3 km grid sections. Regions between 400,000 and 700,000 km2 (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Newfoundland and Labrador) were divided into 5x5 km grids. Although Yukon’s area (∼480,000 km2) falls in that range, it was given 10x10 km grids because of its sparse infrastructure and road network. Regions of about 900,000–1,000,000 km2 (Ontario and British Columbia) used 7x7 km grids. Larger regions of 1,300,000–1,550,000 km2 (Quebec and the Northwest Territories) also used 10x10 km grids. Finally, Nunavut, at over 2,000,000 km2 and spread across numerous islands with minimal road access, required 30 km2 sections. A total of 89,240 grid sections were created. Drive times from the centre of each grid section to all stroke centres in the province, and from each IVT-only centre to all EVT-capable centres were obtained through Open Street Map’s Application Programming Interface (OpenStreetMap Foundation, Cambridge, UK), which uses Open Source Routing Machine to calculate drive times from road distance, speed limits, road type and turn restriction. For grid sections where OpenStreetMap and ArcGIS returned null for drive times and population, respectively, these areas were not considered for any additional calculations, and they are denoted with grey sections on the map. Further validation was conducted to ensure that remote communities were included in the study by random selection of key communities that have been identified by the Government of Canada as remote communities, Reference Canada18 and it was found that the computation methods described above include these remote communities, including fly-in communities, which are displayed as isolated spots on the maps. The population within each grid section considered was obtained from the ArcGIS GeoEnrichment Service (ESRI, Redlands, California, USA), which uses population data from Statistics Canada 2021 Census.

Access to IVT was conducted by calculating the onset to needle time from each grid section. The onset to ambulance arrival time was assumed to be 30 minutes, the ambulance on-scene time was assumed to be 30 minutes, and the door-to-needle time at the stroke centre was set to 30 minutes. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by adding 30 minutes to the EMS response time for an onset to ambulance arrival time of 60 minutes was also conducted; however, the door-to-needle time is incorporated in the DIDO times, so there was no sensitivity analysis done for door-to-needle time. The onset-to-needle time for each grid section was calculated using the following formula where t is time.

$${t_{onset{\rm{ - }}needle}} = {t_{onset{\rm{ - }}Ambulance}} + {t_{on{\rm{ - }}scene}} + {t_{travel:grid{\rm{ - }}hospital}}\\+ {t_{door{\rm{ - }}needle}}$$

$${t_{onset{\rm{ - }}needle}} = {t_{onset{\rm{ - }}Ambulance}} + {t_{on{\rm{ - }}scene}} + {t_{travel:grid{\rm{ - }}hospital}}\\+ {t_{door{\rm{ - }}needle}}$$

If the time from onset to needle is greater than 4.5 hours for any grid section, this area was considered to have no IVT access, which is consistent with the current Canadian best practice guidelines.

Access to EVT was conducted by calculating the onset to arrival at EVT centre from each grid section. Once again, the onset to ambulance arrival time was assumed to be 30 minutes, and the ambulance on-scene time was assumed to be 30 minutes. The onset-to-EVT-centre arrival for each grid section where the closest hospital is an EVT-capable centre was calculated using the following formula where t is time.

$${t_{onset - - EVT - centre}} = {t_{onset - - Ambulance}} + {t_{on - scene}} \\+ {t_{travel:grid - - EVT - Centre}}$$

$${t_{onset - - EVT - centre}} = {t_{onset - - Ambulance}} + {t_{on - scene}} \\+ {t_{travel:grid - - EVT - Centre}}$$

The onset-to-EVT-centre arrival for each grid section where the closest hospital is an IVT-only centre was calculated using the following formula.

$${t_{onset - - EVT - centre}} = {t_{onset - - Ambulance}} + {t_{on - scene}} \\+ {t_{travel:grid - - IVT - Centre}} + {t_{DIDO}} \\+ {t_{Travel:IVT - - EVT - Centre}}$$

$${t_{onset - - EVT - centre}} = {t_{onset - - Ambulance}} + {t_{on - scene}} \\+ {t_{travel:grid - - IVT - Centre}} + {t_{DIDO}} \\+ {t_{Travel:IVT - - EVT - Centre}}$$

There were two scenarios run: a suboptimal scenario and an optimal scenario. In the suboptimal scenario, the DIDO time was set to 150 minutes (2.5 hours), and in optimal scenario, the DIDO time was set to 45 minutes. Poor and suboptimal EVT access regions were determined if the time to EVT-capable centre from each grid section was greater than 6 hours or 3 hours.

The population for all grid sections with poor access for all the scenarios run was summed to determine the total population without access. All visualisations and computations were generated by DESTINE Health software (DESTINE Health, Calgary, Alberta, Canada). Ethic approvals were not required as no patient-level data were used in this modelling study.

Results

The population density across Canada, along with the location of all IVT-only and EVT-capable centres, is shown in Figure 1. Thrombolysis access within 4.5 hours of onset across Canada from each grid section to the closest stroke centre is shown in Figure 2. The map visualisation shows that there is good reach in access, with the majority of regions accessing thrombolysis through an IVT-only stroke centre. The areas of no access are limited to very remote rural areas. The population analysis shows that 0.63% of the Canadian population, or 239,401 people, do not have access to thrombolysis within 4.5 hours.

Figure 1. Location of all IVT-only and EVT-capable stroke centres with a heatmap of population across Canada. Yellow indicates high population density, pink indicated medium population density and blue indicates low population density. Legend: IVT - Intravenous Thrombolysis; EVT: Endovascular Treatment.

Figure 2. Thrombolysis access within 4.5 hours from onset. Legend - IVT = Intravenous Thrombolysis; EVT = Endovascular Treatment; BC = British Columbia; AB = Alberta, SK = Saskatchewan; MB = Manitoba; ON = Ontario; QC = Quebec; NB = New Brunswick; PE = Prince Edward Island; NS = Nova Scotia; NL = Newfoundland & Labrador.

Access to an EVT-capable stroke centre within 6 hours of onset across Canada from each grid section for both the suboptimal DIDO time of 150 minutes and optimal DIDO time of 45 minutes is shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. The map visualisations show that the majority of access is for those areas where the EVT-capable centre is the closest, with some closer IVT-only centres being accessed first; however, the access to EVT through IVT-only centres increases considerably with an efficient DIDO time of 45 minutes. Large areas that are more distant from the EVT-capable centres do not have access to EVT-capable centre within 6 hours, especially in the suboptimal scenario.

Figure 3. EVT-capable stroke centre access within 6 hours from onset for suboptimal DIDO time of 150 minutes. Legend - DIDO = Door-in-door-out; IVT = Intravenous Thrombolysis; EVT = Endovascular Treatment; BC = British Columbia; AB = Alberta; SK = Saskatchewan; MB = Manitoba; ON = Ontario; QC = Quebec; NB = New Brunswick; PE = Prince Edward Island; NS = Nova Scotia; NL = Newfoundland & Labrador.

Figure 4. EVT-capable stroke centre access within 6 hours from onset for optimal DIDO time of 45 minutes. Legend - DIDO = Door-in-door-out; IVT = Intravenous Thrombolysis; EVT = Endovascular Treatment; BC = British Columbia; AB = Alberta; SK = Saskatchewan; MB = Manitoba; ON = Ontario; QC = Quebec; NB = New Brunswick; PE = Prince Edward Island; NS = Nova Scotia; NL = Newfoundland & Labrador.

Access to an EVT-capable stroke centre within 3 hours of onset across Canada from each grid section for both the suboptimal DIDO times of 150 minutes and optimal DIDO times of 45 minutes is shown in Figures 5 and 6, respectively. The map visualisations show that the only way to access the EVT-capable centre within 3 hours in the suboptimal DIDO scenario is in those areas where the EVT-capable centre is the closest centre. This improves when the DIDO time is reduced to 45 minutes, with some access through IVT-only centres allowing the EVT access within 3 hours. Most areas outside of the cities do not have access to EVT-capable centre within 3 hours, especially in the suboptimal scenario.

Figure 5. EVT-capable stroke centre access within 3 hours from onset for suboptimal DIDO time of 150 minutes. Legend - DIDO = Door-in-door-out; IVT = Intravenous Thrombolysis; EVT = Endovascular Treatment; BC = British Columbia; AB = Alberta; SK = Saskatchewan; MB = Manitoba; ON = Ontario; QC = Quebec; NB = New Brunswick; PE = Prince Edward Island; NS = Nova Scotia; NL = Newfoundland & Labrador.

Figure 6. EVT-capable stroke centre access within 3 hours from onset for optimal DIDO time of 45 minutes. Legend - DIDO = Door-in-door-out; IVT = Intravenous Thrombolysis; EVT = Endovascular Treatment; BC = British Columbia; AB = Alberta; SK = Saskatchewan; MB = Manitoba; ON = Ontario; QC = Quebec; NB = New Brunswick; PE = Prince Edward Island; NS = Nova Scotia; NL = Newfoundland & Labrador.

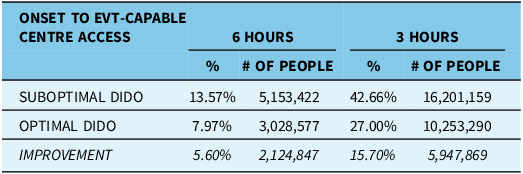

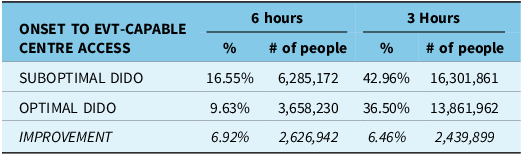

Assessment of the population that does not access within 6 and 3 hours for both scenarios is summarised in Table 1. In the suboptimal scenario, 13.57% of the population or 5.15 million people do not have access to an EVT-capable centre within 6 hours of onset, and this can be reduced to 7.97% or 3.03 million people, if DIDO time was reduced to 45 minutes. Even more stark is access within 3 hours of onset; 42.66% or 16.20 million people do not have access in the suboptimal scenario, which can be reduced to 15.70% or 10.53 million people if the DIDO time were reduced to 45 minutes. The sensitivity analysis with an extended time for ambulance arrival to 60 minutes from onset, from 30 minutes, showed that within 6 hours, optimal DIDO times result in greater improvements of 6.92%; however, this improvement is not apparent with 3 hours, but DIDO still remains a significant variable in improving access to EVT (Table 2).

Table 1. Summary of population that does not have access to an EVT-capable stroke centre within 6 hours and 3 hours from onset for both the suboptimal DIDO time of 150 minutes and optimal DIDO time of 45 minutes. Both the percent of the total Canadian population and the number of people are shown. (Assumption: Onset to ambulance arrival time of 30 minutes)

Legend – DIDO: Door-in-door-out.

Table 2. Summary of population that does not have access to an EVT-capable stroke centre within 6 hours and 3 hours from onset for both the suboptimal DIDO time of 150 minutes and optimal DIDO time of 45 minutes. Both the percent of the total Canadian population and the number of people are shown. (Assumption: Onset to ambulance arrival time of 60 minutes)

Legend – DIDO = Door-in-door-out.

Discussion

This modelling shows the importance of efficient DIDO times for patients that are transferred for EVT from a stroke centre that only provides IVT. However, there are also other strategies that can also be employed to ensure access to EVT. The use of prehospital large vessel occlusion screening tools such as RACE (Rapid Arterial oCclusion Evaluation) and LAMS (Los Angeles Motor Scale) can be used to bypass IVT-only stroke centres in favour of EVT-capable centres. Reference Kamal, Jeerakathil and Demchuk16– Reference Zhao, Pesavento and Coote22 However, the results from the recent RACECAT trial Reference de la Ossa, Abilleira and Jovin23 and modelling of patient outcomes Reference Holodinsky, Williamson and Demchuk24 show that the decision to bypass an IVT-centre is dependent on geography and hospital efficiency. However, in urban areas where an IVT-centre is close to an EVT-capable centre, the use of an LVO-screening tool to bypass an IVT-centre is another strategy to reduce delays for the start of EVT.

In addition to improving transfer efficiency, further geographic and population modelling should be done to determine the potential location of additional EVT-capable centres. Canada currently has approximately 0.7 EVT-capable centres per million people, with some provinces with more and some with less. Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) has 1.81, and Alberta has 0.4 EVT-centres per million people. This is not to say that one is more optimal than others, as NL has a larger rural population, and no other option to access an EVT-capable centre location. The decision to add EVT-capable centres needs to be made with consideration of geographic areas with poor access, while ensuring that their catchment is large enough to ensure there will be sufficient volume.

This modelling study does have some limitations. Only road transport was considered for transfer with the exception of inter-provincial transfers between Prince Edward Island and the three territories as described in the methods section. However, IVT-centres that are located 3 or more hours from the EVT-centre are typically transferred using air ambulance when weather and resource availability permit. Although the DIDO times to arrange air transport are longer, they do have significantly shorter transport times. This was not considered in this study, and future modelling studies should take air transport into consideration. The reason for not including air transport in this study is due to the extensive additional investigation that would be required for each IVT-only centre; each region and centre has highly variable resource availability as well as differences in air transport modality that include fixed-wing transport for some very remote regions that require ground transport to and from each airport; these region-specific nuances with air transfer for EVT have been investigated showing its complexity making the inclusion of air transport the focus of a future study. Reference Wheaton, Fok and Holodinsky25 Furthermore, best-case values for onset to ambulance arrival (30 minutes) and door-to-needle time (30 minutes) were used to show the optimal population that has access; further sensitively analysis can be conducted in future studies to show the impact of delayed ambulance arrival and extended thrombolysis treatment times. Furthermore, the drive times did not consider changes due to seasonal variation and rush hour congestion, which can be the subject of future studies.

A median DIDO time of 45 minutes may seem too aspirational with consideration of current performance. However, this paper shows the imperative to improve this critical measure, especially for rural and remote communities. The sensitivity analysis also shows the importance of initial rapid ambulance response times, especially for access to an EVT centre within 3 hours. Additionally, prior to 2015, a door-to-needle time of 20 or 30 minutes seemed out of reach, but it was shown to be achievable. Reference Meretoja, Strbian, Mustanoja, Tatlisumak, Lindsberg and Kaste26,Reference Kamal, Jeerakathil and Stang27 Therefore, improvement work across Canada needs to begin to reduce DIDO times. Improvements in DIDO times were successfully achieved in ST elevation myocardial infarction through efforts in adopting process care changes across many centres. Reference Glickman, Lytle and Ou28 DIDO times are dependent on multiple factors, from the organisation of the hospital, rapid communication to the EVT-capable centre, urgent organisation of transfer transport, and pre-hospital notification. There is growing evidence of strategies to reduce DIDO times including: (1) holding the ambulance crew at PSC until decision to transport Reference Ng, Low and Andrew8,Reference Choi, Tsoi and Pope9,Reference Gaynor, Griffin and Thornton12,Reference Wong, Dewey and Campbell13 ; (2) performing CTA (computed tomography angiogram) right after the non-contrast CT Reference Choi, Tsoi and Pope9,Reference Kuc, Isenberg and Kraus10,Reference Prabhakaran, Khorzad and Parnianpour11–Reference Royan, Stamm, Giurcanu, Messe, Jauch and Prabhakaran14,Reference McTaggart, Yaghi and Cutting29 ; (3) immediate access to CT images Reference Ng, Low and Andrew8,Reference Choi, Tsoi and Pope9 ; (4) no air transport for shorter distances Reference Wong, Dewey and Campbell13–Reference Gangadharan, Lillicrap and Miteff30 ; (5) early and standardised communication to transfer team and EVT centre Reference Ng, Low and Andrew8,Reference Choi, Tsoi and Pope9,Reference Kuc, Isenberg and Kraus10,Reference Prabhakaran, Khorzad and Parnianpour11,Reference Royan, Stamm, Giurcanu, Messe, Jauch and Prabhakaran14–Reference McTaggart, Yaghi and Cutting29 and (6) no need for advanced life support transport with Tenecteplase. Reference Putaala, Saver, Nour, Kleindorfer, McDermott and Kaste31,Reference Warach, Dula and Milling32 These strategies would be in addition to door-to-needle reduction strategies that have been previously published. Reference Kamal, Smith, Jeerakathil and Hill33

Conclusion

Canada’s vast geography presents significant challenges in access to reperfusion treatments for acute ischaemic stroke patients. Our current stroke system has excellent access to thrombolysis within 4.5 hours, with 99.37% of the population having access within this timeframe. However, 13.57% and 42.66% do not have access to EVT within 6 and 3 hours, respectively. An additional 5.60% (2.12 million people) and 15.70% (5.70 million people) can have access within 3 and 6 hours, respectively, if we reduced our DIDO times to 45 minutes.

Author contributions

NK and AD designed the study. NK wrote the initial draft. JB developed the software models and code. NK, B B-N and JKH conducted the data analyses. DS provided key discussion points. NK, B B-N, JB, B B-N, JKH, DS and AD provided editorial input into the manuscript. NK holds the funds to conduct the study.

Funding statement

Funding for this work is provided by an NSERC Alliance grant, (Title: Designing and Deploying a National Registry to Reduce Disparity in Access to Stroke Treatment and Optimise Time to Treatment, PI: Noreen Kamal) this include funding support from Medtronic.

Competing interests

NK and JKH are co-founders and part owners of DESTINE Health Inc. JB has received consultancy payment from DESTINE Health Inc. NK and AMD report unrestricted grant from Medtronic for OPTIMISING ACCESS study to measure and improve stroke workflow within Canada. AMD reports royalties with Circle CVI, receiving consulting fees with Hoffman LaRoche, receiving honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, participation on Data Safety Monitoring Board or advisory board with Philips and Lumosa, chair for the Board of Directors for the Canadian Stroke Consortium, and stocks in Circle CVI.