Introduction

David Yates’ Reference Yates2007 groundbreaking publication Land, Power and Prestige synthesised the known evidence for lowland Britain, highlighting the extent and scale of settlement and land division in the Middle and Late Bronze Age, which he collectively termed ‘the later Bronze Age’ (1500–700 BC; Yates Reference Yates2007, 1). Perhaps inevitably, given the evidence at the time, the eastern region’s coverage was dominated by the lower river valleys of the western fen edge (the Ouse, Nene, and Welland), where the later Bronze Age is characterised by extensive, largely co-axial, field systems. Forming ‘land blocks’ within bounded landscapes, the systems were complex and coordinated with settlement zones located amongst/within them (Yates Reference Yates2007, 82–100).

Since 2007, the western fen edge has continued to be a focus of Bronze Age studies, with numerous landscape-scale projects in all three of the major river valleys (eg, Evans et al. Reference Evans, Tabor and Vander Linden2016; Knight & Brudenell Reference Knight and Brudenell2020; Richmond et al. Reference Richmond, Francis and Coates2022). Consequently, how field systems and these landscapes are understood and interpreted has also developed considerably. For example, the systems of the Flag Fen Basin are considered by Knight and Brudenell (Reference Knight and Brudenell2020, 206–12) as complex expressions of continued land tenure and land-use or ‘texture’ rather than simply an imposition of a ‘new sense of order’ (Yates Reference Yates2007, 134–5). In addition, increasing evidence of arable cultivation has led Evans and colleagues (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Beadsmoore, Brudenell and Lucas2009, 63–4) to suggest that field systems potentially reflect mixed agricultural regimes rather than a primarily pastoral focus (see Pryor Reference Pryor1996). It is also now accepted that within the region, field systems are a predominantly Middle Bronze Age phenomenon, generally being established after 1600 BC and falling out of use by 1000 BC, if not before (Johnston et al. Reference Johnston, May, McOmish, Arnoldussen, Johnston and Løvschal2021, 195).

In contrast, aside from the area immediately to the north of the Thames Estuary, the remainder of East Anglia has received much less attention. It was covered in Yates’ volume by a single short chapter, and the evidence cited for settlement and land division was often limited. Over the last two decades, however, an increasing number of sites in wider East Anglia have been investigated (Cooper Reference Cooper2018), largely through developer-funded projects. All have been dated to within the period 1600–1150 cal BC and can be considered broadly contemporary with the major field systems of the western fen edge.

Building on this recent work, the primary purpose of this paper is to synthesise and discuss the evidence from two case study areas – South Cambridgeshire and East Norfolk. Both are located on the edge of what are characterised here, comparatively speaking, as the East Anglian uplands: the area south and east of the Fens and north of the Thames Estuary, incorporating wider Norfolk, Suffolk, and northern Essex. The majority of sites discussed are situated between 10 m and 35 m OD (Figure 1). Both case study areas are largely determined and defined by modern development and associated excavations and research projects, mostly undertaken by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit (CAU) and Oxford Archaeology (OA), which in effect provide large-scale sampling of two coherent prehistoric landscapes. In addition to the case study areas, the evidence from the wider region ‘beyond the fens’ is also briefly appraised, followed by a discussion that reflects on how the evidence contributes to a broader understanding of Middle Bronze Age East Anglia and lowland Britain more generally.

Figure 1. East Anglia, highlighting the two case study areas and other landscape zones mentioned in the text.

South Cambridgeshire

Occupying the northern edge of the chalklands that extend from the Chilterns up into East Anglia, the South Cambridgeshire landscape is one of shallow valleys and chalk streams, which feed the River Cam. To the north the landscape opens out into the Cambridgeshire Fens, with the major Bronze Age landscapes of the lower Ouse Valley/western fen edge located within 20 km. Until recently, the area’s Bronze Age has received limited attention, with most focus on the monumental aspects of the landscape (eg, Hinman Reference Hinman and Brück2001). However, within the last 15 years, the area around, and particularly to the south of, Cambridge has seen significant investigation ahead of housing developments, and the expansion of Addenbrooke’s Hospital and the Cambridge Biomedical Campus (CBC). This has in turn transformed both the archaeological record and our understanding of the landscape.

Within this part of the Cam Valley, adjacent Middle Bronze Age settlements excavated at Clay Farm and the CBC (Figure 2), are joined within c. 6 km by further examples of Middle Bronze Age land division and enclosed settlement at Worts’ Causeway, Cherry Hinton, Fulbourn, and Marleigh. These sites occupy a distinct geographical zone, lying between 11 m and 18 m OD on the transition between the rising chalklands to the south, and lower-lying areas of gault clay and river terrace gravels to the north. Beyond this, additional enclosures have been recorded at various sites up and down the Cam Valley (Table 1), providing evidence for an extensively settled and utilised Middle Bronze Age landscape.

Figure 2. South Cambridgeshire study area showing sites mentioned in the text.

Table 1. South Cambridgeshire site summary. * = Approximate area of settlement/enclosures investigated by open area excavation, in hectares. ** = modelled duration (in italics) or number of single dates giving the earliest and latest dates at 95% probability. See Supplementary S1 for further details of dating.

Clay Farm and the Cambridge Biomedical Campus (CBC)

Located at the confluence of the rivers Cam, Granta, and Rhee, three separate enclosed settlement sites at Clay Farm (Phillips & Mortimer Reference Phillips and Mortimerforthcoming) and the CBC (Tabor, with Phillips Reference Tabor and Phillips2024) were situated in a shallow valley on either side of a chalk stream (Hobson’s Brook) (Figure 3). Each of the settlements has produced exceptional artefactual and faunal assemblages, and palaeoenvironmental remains, which, when combined with the scale of the excavation areas (totalling c. 36 ha) offer remarkable insight into Middle Bronze Age occupation and land-use.

Figure 3. Hobson’s Brook Valley, Cambridge.

The earliest evidence of Middle Bronze Age activity comprised a system of strip-like fields extending across Clay Farm and the CBC, which appears similar to the co-axial/rectilinear systems of the western fen edge. It was probably established between 1600–1500 cal BC but only lasted 30–150 years (Healy & Dunbar Reference Healy and Dunbar2024, 105; Hamilton Reference Hamiltonforthcoming), with insubstantial ditches that were evidently not maintained, suggesting a short use life. Evidence of contemporary settlement was limited to an early phase of CBC Site I, which produced Deverel-Rimbury pottery and a mixed animal bone assemblage dominated by cattle, sheep/goat, and pig in fairly equal proportions.

At both Clay Farm and CBC, this early field system was subsequently abandoned and replaced by more discrete complexes of sub-square/sub-rectangular enclosures defined by substantial ditches (generally 2–3 m wide and up to 1.5 m deep) and banks. These complexes represent three individual settlements (Clay Farm Settlement 1 and 2, and CBC Site I/VI) situated within a more open landscape, where enclosure was generally limited to the immediate settlement environs.

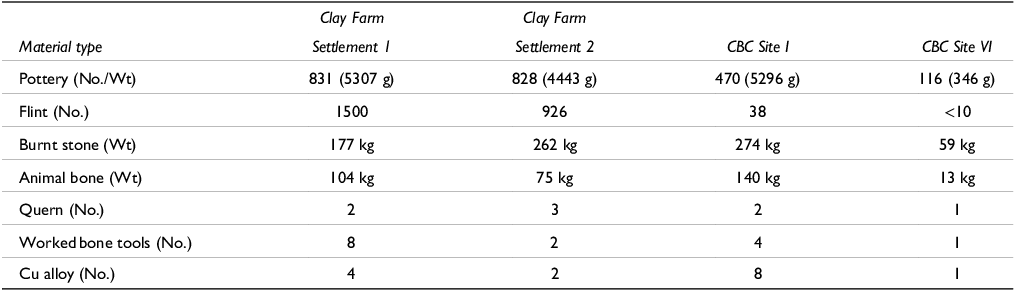

At Clay Farm, neither of the two enclosure complexes were exposed to their full extent; however, it can be estimated that each comprised eight to ten conjoined enclosures/paddocks (Figure 4). Bayesian modelling of radiocarbon dates suggests construction and use between the mid-16th and early 12th centuries cal BC (Hamilton Reference Hamiltonforthcoming; Table 1).Footnote 1 Each complex had evidence of occupation within one or more of its enclosures. In Settlement 1 – the northernmost – occupation waste was spread over several enclosures (Table 2), although much came from the midden-derived fills of a single length of enclosure ditch where the ‘freshness’ of the finds suggests it was dumped directly (Ditch 1; see Figures 4–5). Evidence of four post-built structures was confined to an area some 140 m away from the midden deposits, where there were otherwise scant signs of occupation. Settlement 2, the southern enclosure complex, also produced plentiful occupation waste, once again deposited in middens within ditches – this time nearer structures – as well as more generally throughout the settlement’s features.

Figure 4. Clay Farm, Cambridge. Middle Bronze Age features showing detail of early ‘strip’ field system and enclosures.

Table 2. Finds assemblage summaries for Clay Farm and the CBC sites.

Figure 5. Clay Farm, Cambridge. Settlement 1, Ditch 1 (darker upper fill contained most of the midden material).

At a site-wide level, livestock farming – predominantly cattle and to a lesser extent sheep/goat and pig – appeared to be the main focus at Clay Farm. Supporting this interpretation, well-preserved pollen and insect remains from a waterlogged enclosure ditch in Settlement 1 indicate a siting in or close to grazed open grassland. Charred cereal remains – dominated by hulled wheat grain (emmer wheat with lesser amounts of spelt wheat) – indicate the processing, storage, and consumption of crops within some of the enclosures, although the site’s pollen signature suggests cultivation was not taking place within the immediate vicinity of the settlement.

At the CBC, Site I and Site VI comprised an enclosure complex and a single enclosure respectively (Figures 6–7). Located just 250 m apart and at least in part contemporary, they likely formed separate elements of the same settlement. Both contained occupation waste including large pottery and faunal assemblages (see Table 2). However, whilst Site VI was simple in form and seemingly single-phase, Site I was more complex, with three interlinked compounds/enclosures (A–C) and a series of attached boundaries (Figure 6).

Figure 6. CBC Sites I and VI, Cambridge. Middle Bronze Age features showing detail of early field system and enclosures.

Figure 7. Aerial view of CBC Site I, Cambridge, from the south with Compound A in the foreground (Copyright Suave Air Photos).

On first view, the Site I enclosure complex, particularly its triple-ditched Compound A, appears elaborate and almost monumental; however, this appearance is due in large part to multiple phases of re-working and expansion. Developing from the initial settlement phase (Compound B) associated with the early field system, two further compounds/enclosures (A and C) were added, following the abandonment of the wider field system in the early/mid-15th century cal BC. Compound C remains largely unexcavated beneath the railway line to the west; however, excavation showed that Compound A underwent at least two further phases of development as a double-ditched enclosure was succeeded by a large single-ditched enclosure.

Evidence of occupation was recovered from all phases of the Site I enclosure complex, represented by at least three post-built roundhouses, and assemblages of pottery, faunal remains, and burnt stone (Table 2). The particularly large faunal assemblage recovered from the later enclosure phases also reflects the development of a more specialised site (Tabor, with Phillips Reference Tabor and Phillips2024, chap. 2). Alongside a decline in evidence of occupation, the large quantities of cattle bone (over 70% of the identified faunal remains) compared to sheep and pig suggest an increasingly heavy cattle-focus. As indicated by the kill-off profile – the majority of animals living only to 18–36 months – beef production was probably the primary concern, and the developing layout of the site directly reflects this. The three interlinked compounds appeared well designed for the containment, control, and movement of livestock, whilst the enclosure complex’s funnelled south-eastern entranceway – leading from open land to the south – suggests cattle droving on a potentially large scale, directly into Compound A for sorting, counting, and culling/slaughter.

Combined, the quality of the evidence and the size of the Clay Farm and CBC assemblages afford a valuable and rare opportunity to compare the material culture and economies of neighbouring Middle Bronze Age settlements (see Tabor, with Phillips Reference Tabor and Phillips2024). Whilst all saw occupation to varying degrees, subtle differences provide insight into how the enclosure complexes may have interacted. As CBC Site I became more cattle-focused, Clay Farm, particularly Settlement 1, probably became the main settlement focus for the wider community, with increased processing and consumption of cereals, larger pottery assemblages (including finewares), and contemporary flintworking, all hinting at increased domesticity. In contrast, a smaller pottery assemblage and scant evidence of contemporary flintworking suggests reduced settlement during later phases at CBC Site I. Most likely, the Clay Farm/CBC enclosure complexes functioned as one larger community and linked settlement zone, with each fulfilling a slightly different role.

Determining the precise end date of the settlements is challenging. However, certainly by the turn of the 12th century cal BC all the enclosures were in the process of being abandoned. Limited evidence of Late Bronze Age activity was encountered mainly in the form of small quantities of pottery within the upper fills of certain ditches; however, there is no indication that the enclosures continued to function as settlement sites. Instead, Late Bronze Age midden deposits/surface spreads indicative of occupation have been recorded elsewhere within the immediate landscape (see Evans et al. Reference Evans, Mackay and Webley2008; Tabor, with Phillips Reference Tabor and Phillips2024).

In terms of landscape setting, Clay Farm/CBC clearly occupied a distinct environment, which undoubtedly facilitated the development of such an extensive and seemingly prosperous settlement swathe. Palaeoenvironmental data indicate an extensive and rich area of pasture with abundant natural springs rising from the foot of the chalklands that lie to the south (most notably at Nine Wells). Just to the east, further boundaries/field systems have also been recorded at Bell Language School (Billington et al. Reference Billington, Moan and Phillips2021), Babraham Road (Hinman Reference Hinman and Brück2001, 36–8), and alongside contemporary settlement at Worts’ Causeway (Abrehart Reference Abrehartforthcoming). Here, once again, a two-fold sequence of land division with associated enclosed settlement remains was recorded, although unlike Clay Farm/CBC, the second phase of land division comprised more extensive re-cutting and continuity of the existing ‘early’ field system. Nonetheless, Worts’ Causeway should be considered part of the larger Clay Farm/CBC settlement swathe, which extended for several kilometres across the valley floor (see Figure 3).

The extent and scale of this settlement swathe had led Evans and colleagues (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Lucy and Patten2018, 426) to describe it as ‘a Bronze Age enclave’. However, with an increasing number of broadly contemporary sites now recorded in the Cam Valley, these sites also functioned as part of a much broader community. Indeed, the CBC Site I enclosure has been interpreted as a potential gathering/market place (Tabor, with Phillips Reference Tabor and Phillips2024). The results of an initial isotope study on cattle bone from the enclosure (currently being expanded as part of the Animals and Society in Bronze Age Europe project; < https://ansoc.net/>) support this, with four out of eight individuals raised on non-local soils potentially up to c. 20 km away (Rogers et al. Reference Rogers, Nowell and Montgomery2024). This evidence for trade and/or an extensive community of cattle farmers in the area provides both context for, and the beginnings of, an interpretive framework within which to consider other sites within the wider Cam Valley.

Enclosures and land division in the wider South Cambridgeshire landscape

Some 3.5 km to the north-east of Worts’ Causeway, along the northern edge of the chalklands, investigations at Cherry Hinton have revealed four discrete sub-square enclosures interlinked by linear ditches, which functioned as ‘landscape’ boundaries rather than defining fields (T. Bourne pers. comm.). As the only site where the scale of exposure (c. 25 ha) matches that at Clay Farm/CBC, the absence of a formal/extensive field system is once again significant. Approximately 2 km north of Cherry Hinton, two conjoined enclosures have been recorded at the new Marleigh development (Figure 8). Here again, there was no evidence for a field system; the enclosures were newly established within a previously open landscape. Their location was instead influenced by an Early Bronze Age pond barrow and possible post-ring monument, which was incorporated into the enclosed area (Bourne & Tabor Reference Bourne and Tabor2023). At both Cherry Hinton and Marleigh, the enclosures were defined by substantial ditches, comparable in scale or larger (up to 4.5 m wide and 1.8 m deep) than those at Clay Farm and the CBC.

Figure 8. Comparative Middle Bronze Age enclosures and enclosure systems in South Cambridgeshire.

Two enclosures (plus two possible/partial examples) at North West Cambridge mark the most northerly of the enclosure sites, situated on slightly lower-lying clays and gravels. Both main enclosures were discrete (eg, Figure 8) and defined by ditches c. 2–3 m wide by 0.8–0.9 m deep. Marking the southern extent of the recorded enclosure sites in South Cambridgeshire, New Road, Melbourn was slightly different in character (Ladd Reference Ladd2022). Its main components were a large sub-square enclosure (0.65 ha) with modest ditches (a maximum of 0.62 m deep) and a system of fields and paths defined by postholes (Figure 8). Although unusual in a South Cambridgeshire context, similar Middle and Late Bronze Age settlement-related post architecture is recorded in the wider region (eg, Wallis & Waughman Reference Wallis and Waughman1998; Luke & Barker Reference Luke and Barker2022, 39–44; Luke Reference Luke2016, 125–6). Unfortunately, it was not possible to determine the chronological relationship between the fencelines and ditched enclosure at Melbourn.

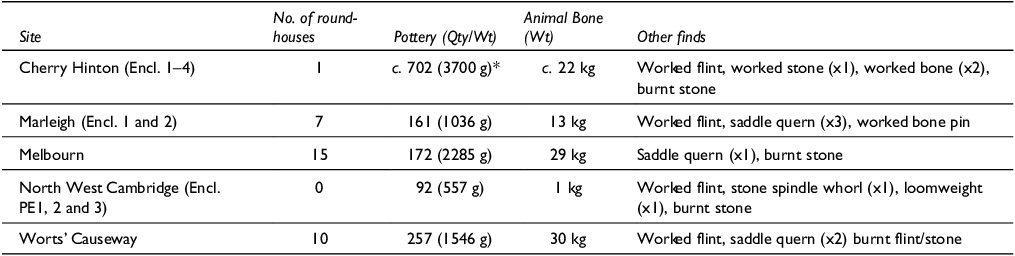

Evidence of settlement was recorded at all of the aforementioned enclosure sites, often in the form of post-built roundhouses (Table 3). Where well preserved, the circular or sub-circular post rings, typically 4–6 m in diameter, sometimes exhibited evidence for the re-cutting or adding of postholes (presumably relating to repair or replacement; Figure 9). In better preserved examples, ‘projecting’ postholes marked east or south-east facing doorways and were the only evidence for the line of the outer wall, indicating that the overall diameter of the roundhouses would have been 8–9 m. Overall, they are of a design and layout that is increasingly familiar and widely recorded at the South Cambridgeshire sites and beyond.

Table 3. Comparative data for other South Cambridgeshire sites (*interestingly a further c. 1000 sherds were recovered from contexts, largely pits, outside of the enclosures).

Figure 9. Comparative plans of selected Middle Bronze Age structures in the two case study areas.

Whilst the structures indicate settlement, at most sites they were not accompanied by large material assemblages, which further highlights the significance of the evidence from Clay Farm/CBC. For example, using Middle Bronze Age pottery totals as a gauge, Worts’ Causeway, Marleigh, and Melbourn all produced modest quantities (Table 3), especially given the number of roundhouses at each. Three of the four enclosures at Cherry Hinton produced a slightly more impressive assemblage, although midden deposits in the ditches were targeted for 100% excavation, skewing the comparative totals. At North West Cambridge, just 92 sherds of Middle Bronze Age pottery were recovered from all enclosures combined. Evans et al. (forthcoming) attribute this, in part, to probable seasonal use of the enclosures. However, at both Marleigh and Melbourn, relatively large numbers of roundhouses suggest either multiple households on a more permanent basis or, if occupied only seasonally, more frequent or long-lasting use. Either scenario would be expected to generate much more occupation-related detritus, and it must be assumed that the majority accumulated as surface middens that have not been preserved. As a result, the surviving assemblages probably represent only a fraction of the sites’ occupation waste. Even at Clay Farm and CBC Site I, where comparatively large assemblages were recovered (see Table 2), it appears to have been the result of rare depositional circumstances, resulting in occupation waste finding its way into specific features through deliberate dumping/back-filling.

Consequently, evidence for farming practices and environment is limited at all sites other than Clay Farm/CBC. Animal bone is present in small quantities, although once again assemblages are mostly dominated by cattle. Paleoenvironmental data are even more limited; evidence for arable cultivation is largely absent and the general environmental signature is dominated by grassland species (plant and mollusc).

In terms of chronology, whilst none of the other South Cambridgeshire enclosures have seen radiocarbon dating and chronological modelling on the scale of Clay Farm and CBC Site I (see Table 1), they all generally date to the period 1500–1200 cal BC. None appear to have seen continuity of occupation into the Late Bronze Age. Indeed, at Cherry Hinton, the Late Bronze Age saw a distinct shift in settlement location and character, whilst at North West Cambridge an ‘open’ Late Bronze–Early Iron Age settlement swathe extended across the infilled ditches of one of the enclosures.

Middle Bronze Age ditches/enclosures have also been partially exposed within more limited excavation areas. These include short sections of enclosure ditches at Harris Road and New Hall, within Cambridge itself (House Reference House2010; Evans & Lucas Reference Evans and Lucas2020) (Table 1; Figure 2). To the south, parts of enclosures have been identified in Sawston (Mortimer Reference Mortimer and Bishop2005; Weston et al. Reference Weston, Newton and Nicholson2007) and Fulbourn (Brown & Score Reference Brown and Score1998), whilst trial trenching (combined with geophysics) at Barrington (Dickens et al. Reference Dickens, Knight and Appleby2006) has singled out a sub-square enclosure situated on a distinct chalk ridge (see Figure 8). It is difficult to determine the degree to which these sites could have been settlement-related, or indeed seasonally used, although they do offer further evidence of an extensively utilised Bronze Age landscape.

Across South Cambridgeshire, various scales of occupation and activity are evident. Some enclosed settlements may have been occupied on a long-term basis, others may have seen only seasonal use or been employed specifically for the control of livestock. All should be considered in the broader context of the open and extensive grasslands/pasture that they occupied, as well as the predominantly cattle-driven local economy (with only a limited arable component). The prevalence and characteristics of enclosures clearly reflect the need to manage and protect herds at different scales. Together with the absence of evidence for wider contemporary field systems, this suggests that livestock may have been largely free roaming and managed differently to those in areas where complex co-axial field systems predominate. Herds were perhaps only gathered periodically for sorting, processing, slaughter at the optimal age for beef, or at times of danger (see Tabor, with Phillips Reference Tabor and Phillips2024, chap. 2). For much of the year, they may have been loosely managed, moving between extensive areas of pasture and potentially venturing further afield seasonally, in a system akin to open range cattle farming.

The burial evidence

In South Cambridgeshire, widespread cremation burial is attested by two large cemeteries – at Clay Farm and Cherry Hinton – and by smaller groups or isolated burials elsewhere. Disarticulated unburnt remains are also well represented, while mixed inhumation and cremation cemeteries focussed around barrows have been found at two sites: Worts’ Causeway and Hinxton (Lewis & Headifen Reference Lewis and Headifen2024).

The Clay Farm cemetery comprised 37 unurned cremation burials and one poorly preserved inhumation placed within the shallow ditch of a round barrow (Figure 10) that is assumed to be of Early Bronze Age date (a central burial, if it existed, lay beyond the limits of excavation). Modelled radiocarbon dates indicate use of the cemetery between 1695–1440 cal BC and 1280–940 cal BC (Hamilton Reference Hamiltonforthcoming, fig. 2.52). The cemetery was directly to the south of Settlement 1, suggesting that the interred individuals were inhabitants of the settlement. At Cherry Hinton, over 50 cremation burials – 19 within Middle Bronze Age urns – and four inhumations were associated with six complete or partial ring-ditches/C-shaped ditches, c. 200 m from the nearest enclosure. The cemetery was only recently excavated and understanding of its chronology is limited; however, it is another large cemetery with a considerable Middle Bronze Age component located near contemporary settlement.

Figure 10. Clay Farm, Cambridge, Settlement 1. Cremation cemetery within barrow ditch.

At Worts’ Causeway, a small ring-ditch/barrow was located directly west of the settlement (Figure 11; Abrehart Reference Abrehartforthcoming). The earliest burials comprised four Early Bronze Age cremation burials (two held in Collared Urns) and a ‘central’ inhumation dated to 1690–1520 cal BC (SUERC-110467). Subsequently, four flexed inhumations were placed in graves in the interior of the ring-ditch, including a young child (1620–1450 cal BC; SUERC-127315) and another four individuals in three graves inserted into the ditch. A further 11 flexed inhumations and one cremation burial encircled the ring-ditch, seven of which have been radiocarbon dated to the Middle Bronze Age, including three ‘transitional’ burials that probably predate 1500 cal BC. Grave goods were rare, but present in two burials, comprising two shale studs and two shale rings or dress accessories (Figure 12) (Sheridan Reference Sheridan and Abrehartforthcoming).

Figure 11. Worts’ Causeway, Cambridge. Plan of barrow and cemetery.

Figure 12. Worts’ Causeway, Cambridge. Skeleton 975 and shale ‘napkin rings’ (dress accessories), SF 120 and SF 121. Artefact photos by Alison Sheridan.

Such a large group of inhumations of this date, when cremation burial dominated the record, is unprecedented for the region, if not nationally (Robinson Reference Robinson2007; Caswell & Roberts Reference Caswell and Roberts2018). However, in South Cambridgeshire there are other examples. Further up the Cam Valley at Hinxton Genome Campus, another barrow/ring-ditch had secondary burials, including three flexed/crouched inhumations cutting through the lower fills of the ring-ditch (Lewis & Headifen Reference Lewis and Headifen2024). Two have been radiocarbon dated to the Middle Bronze Age. Further inhumations and two unurned cremation burials inside the ring-ditch included a cluster of three intercutting burials, the earliest of which dated to 1505–1420 cal BC (SUERC-127836), whilst another was buried with two beads and a shale stud, reminiscent of the Worts’ Causeway grave goods.

There are also examples of ‘isolated’ cremation and inhumation burials, some located within or immediately around settlement enclosures, others in the wider vicinity. At Clay Farm, the crouched inhumation of an adult female (1410–1220 cal BC; SUERC-38250) was positioned almost equidistant between the roundhouses of Settlement 1 and the cremation cemetery/barrow, whilst at CBC Site I, the skeleton of an adult female (1390–1120 cal BC; SUERC-73841) was found in the top of one of the enclosure ditch terminals. In addition, a further four individuals in separate graves outside of the main cemetery at Worts’ Causeway included three positioned along a major, long-running boundary ditch (radiocarbon dates for all four spanning the 15th to 13th centuries BC). Isolated cremation burials are also recorded, most notably at Cherry Hinton, where they include a Middle Bronze Age urn as well as a further 32 undated cremation burials spread across the site, at least some of which are most probably contemporary. Add to this the 11 burials recorded at North West Cambridge – which included a small cremation cemetery associated with a pair of ring-ditches, as well as isolated cremation burials and an inhumation –, and it is clear that a varied burial rite was practiced.

Finally, evidence from the Cam Valley sites suggests that the placing or burying of unburnt disarticulated remains within settlement features – perhaps following excarnation or the exhumation of an individual from elsewhere – may have also been an important form of burial. Clay Farm produced ten such deposits in ditches and pits, particularly skull fragments. It can be assumed that the actual total was much higher. A further four instances – of skull, arm, and leg bones, possibly representing five individuals – derived from the fills of enclosure and boundary ditches at CBC Site I, and there was one mandible in an enclosure ditch at Worts’ Causeway.

East Norfolk

In East Norfolk, the valleys of the Rivers Bure and Yare and its tributary the Wensum dissect varying geologies, all rising in claylands in the central part of the county and flowing east towards the coast. Around Norwich, the rivers cut through glacial sands, heathland, and rich loamy soils before reaching the low-lying Norfolk Broads. Topographically, the landscape is gently undulating, with broad interfluves (30–40 m OD) between the river valleys.

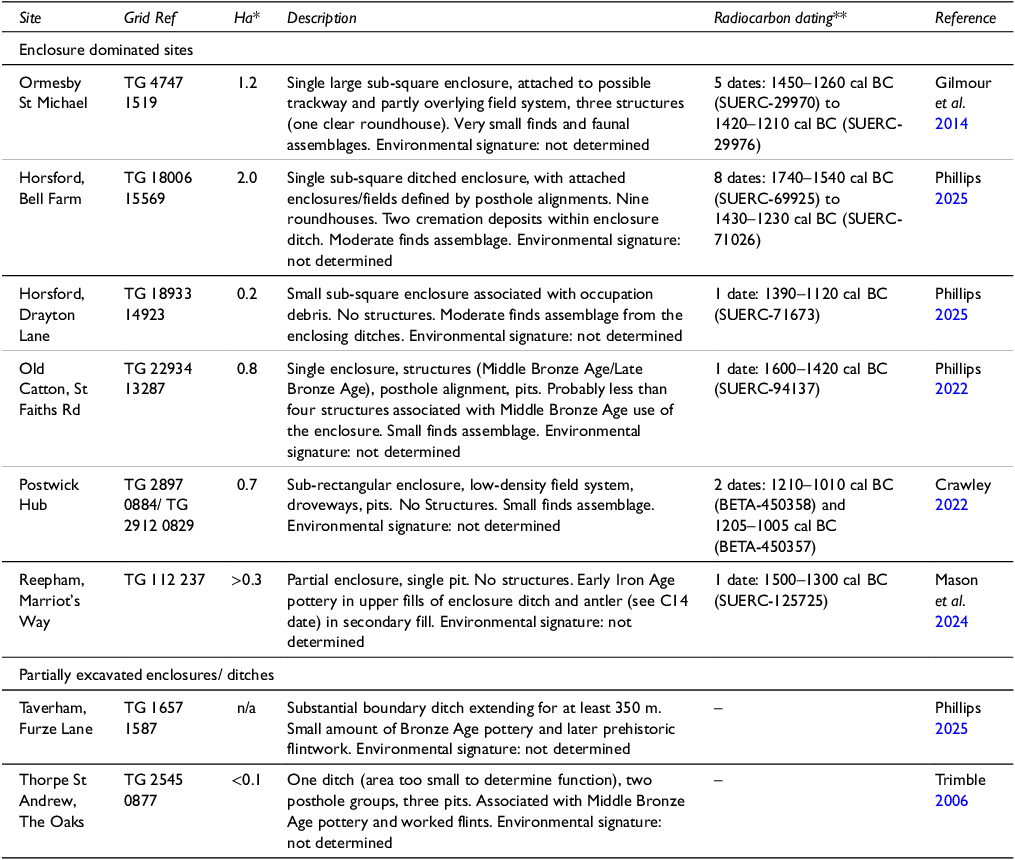

Whilst Norfolk has a rich record of Middle and Late Bronze Age metalwork along the river valleys and coast (Ashwin Reference Ashwin, Ashwin and Davison2005, 21–2), with the exception of a few sites in the west of the county (eg, Mercer Reference Mercer1981, 36–8; Gibson Reference Gibson, Last, McDonald and Murray2004), the settlement record is less well known. Yates (Reference Yates2007, 81) did, however, suggest the coastal area around Great Yarmouth, where the rivers Yare and Waveney meet the North Sea, as a prime location for potential later Bronze Age settlement. Excavated in 2010, the Middle Bronze Age enclosure at Ormesby St Michael in the Broads is located on the northern side of the wider Bure Valley, but broadly speaking within the zone suggested by Yates. After re-appraisal of aerial photographic evidence from a much larger area, examining sites that had previously been dated as Romano-British or medieval, it was argued that Ormesby St Michael represents one of many enclosures and areas of extensive Middle Bronze Age field system (Gilmour et al. Reference Gilmour, Horlock, Mortimer and Tremlett2014). Since then, open area excavations have revealed a cluster of sites in the watershed of the major river valleys to the north of Norwich (Figure 13; Table 4), with enclosed settlements recorded at Bell Farm and Drayton Lane in Horsford, and at Old Catton c. 4 km to the east.

Figure 13. East Norfolk study area showing sites mentioned in the text.

Table 4. East Norfolk site summary. * = Approximate area of settlement/enclosures investigated by open area excavation, in hectares. ** = modelled duration or number of single dates and range at 95% probability. See Supplementary S1 for further details of dating.

The Norfolk enclosures

Land division in the East Norfolk valleys is comparable, but also subtly different to South Cambridgeshire; more sites take the form of discrete enclosures with only one, Bell Farm, that could potentially be described as an enclosure system. The only site where a potential early field system predating any enclosure has been identified is Ormesby St Michael, its long thin strip fields not dissimilar to those at Clay Farm.

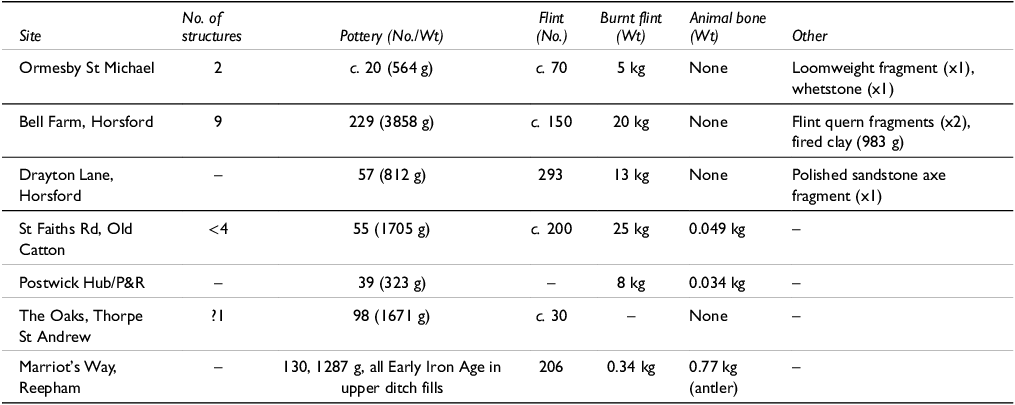

Ormesby St Michael subsequently saw construction of a single substantial sub-square enclosure (c. 1.3 ha) with ditches on average 2.9 m wide and 1.1 m deep, divided along its main axis by a slightly shallower north–south oriented ditch (Figure 14). All other sites in the study area are similarly dominated by single-ditched enclosures with varying degrees of settlement-related activity. Along an elevated ridge of higher ground between the Bure and Wensum Valleys, sub-rectangular enclosures are recorded at Bell Farm and Drayton Lane, Horsford (Phillips Reference Phillips2025), and St Faiths Rd, Old Catton (Phillips Reference Phillips2022) (Figure 14). The Bell Farm and Old Catton enclosures – although of contrasting proportions (0.38 ha and 0.82 ha respectively) – shared the characteristic of being bounded on three sides by ditches (up to 3.2 m wide and 1.6 m deep) with the fourth side defined by a post alignment. Bell Farm also featured an unusual rectilinear system of posthole alignments attached to the ditched enclosure (Figure 15) – potentially screens or elaborate fences defining small plots/enclosures for domestic and working areas. The smaller (0.24 ha) sub-square enclosure at Drayton Lane, 1 km east of Bell Farm, seems small for a settlement compound, but its ditches contained significant domestic debris.

Figure 14. Comparative Middle Bronze Age enclosures in East Norfolk.

Figure 15. Bell Farm, Horsford, showing the post alignments that form a significant part of the settlement’s layout.

In the wider landscape there are hints of associated boundary ditches (Figure 16), but no extensive or complex field system(s). Most are cropmarks, only some of which may be Middle Bronze Age. The notable exception is a sizeable (up to 7 m wide and 1.7 m deep) (Figure 17) boundary ditch excavated at Furze Lane, Taverham (1.4 km west of Bell Farm; Phillips Reference Phillips2025), which contained a small amount of Bronze Age pottery (12 sherds, 155 g) and later prehistoric flintwork (143 items), but importantly, no finds of an obviously later date. Extending for at least 350 m, the Taverham boundary reflects a significant investment of time and labour at a scale beyond that of a typical field ditch. Crossing the interfluvial area between the Wensum to the south and a minor tributary of the Bure to the north (the River Hor), the boundary may have been a way of controlling access through the landscape. This is significant in terms of the character of land division here; it suggests, perhaps, land blocks defined by large landscape boundaries with fewer minor divisions. Within these larger defined blocks, areas of occupation were marked by discrete enclosures.

Figure 16. Middle Bronze Age sites in Taverham and Horsford with selected cropmarks, East Norfolk.

Figure 17. Furze Lane, Taverham. Long-running boundary ditch.

Further potential enclosures have been partially excavated at Postwick, close to the River Yare east of Norwich, and in Reepham (see Figure 14), at the north-western extremity of the case study area. Both are poorly dated. The Postwick enclosure ditch (c. 3 m wide and 1.25 m deep) produced a mixed assemblage of Bronze Age to Early Iron Age pottery (Crawley Reference Crawley2022, 63). Associated with the enclosure was a co-axial arrangement of ditches potentially representing contemporary land division and droveways. The Reepham enclosure was defined by substantial V-shaped ditches (up to 3 m deep). Although not associated with any Middle Bronze Age material culture, its morphology is consistent with a Middle Bronze Age date, and a partial red deer antler from a secondary fill returned a radiocarbon date of 1500–1300 cal BC (SUERC-125725) (Mason et al. Reference Mason, Rogers, Green and White2024).

Like many of the South Cambridgeshire enclosures, Middle Bronze Age settlement evidence within the Norfolk case study area focusses on architecture and settlement-related features rather than artefacts and ecofacts. However, unlike in South Cambridgeshire, some of the Norfolk enclosures did continue into the Late Bronze Age. Bell Farm contained nine Middle Bronze Age post-built roundhouses of varying size and form (Table 5), constructed within both the ditched enclosure and the system of plots defined by the post alignments, as well as six Late Bronze Age structures. At nearby Old Catton, three out of seven structures were conclusively Late Bronze Age; the remainder were undated, but at least some could have been broadly contemporary with the Middle Bronze Age enclosure. In addition, two radiocarbon determinations from the lower and upper fills of the enclosure ditch at Postwick returned almost identical dates between 1210–1005 cal BC (Beta-450357, Beta-450358; Crawley Reference Crawley2022, 63), possibly indicating continued use into the Late Bronze Age. The only other structures in the East Norfolk study area, at Ormesby St Michael, comprised two post-built examples – one of which was horseshoe-shaped with an internal ‘trough’ feature – and a third possible structure formed by two beamslots and another ‘trough’.

Table 5. Comparative data for the East Norfolk sites.

Bell Farm’s Middle Bronze Age pottery assemblage was comparatively large, and struck flint, burnt flint, and fired clay, possibly from an oven, were also recovered. Despite its lack of structures and modest proportions, the enclosure at Drayton Lane also yielded modest midden-derived deposits, as did Old Catton (see Table 5). Elsewhere, Ormesby St Michael had a little pottery alongside a loomweight fragment and a whetstone, while Postwick and Reepham produced very few Middle Bronze Age finds. The lack of faunal remains from the Norfolk case study area (resulting from the acidic soils) makes it difficult to assess the importance of animal husbandry, although it seems likely that much of the land beyond the discrete enclosures was used as pasture. Equally, environmental data are scarce, but pollen analysis at Postwick indicated that the enclosure sat within a cultivated landscape with signs of woodland clearance nearby (Crawley Reference Crawley2022, 63).

In the absence of a local equivalent to Clay Farm/CBC, which in many ways informs the interpretation of the other South Cambridgeshire sites, the context and function of the Norfolk enclosures is hard to interpret. There seems little doubt that Bell Farm, Drayton Lane, Old Catton, and Ormesby St Michael functioned as settlement enclosures. Once again, however, with the exception of Drayton Lane, settlement debris was not being deposited directly into ditches, and thus the full scale of occupation is not reflected by the material assemblages.

Burial evidence

Compared to South Cambridgeshire, the burial record in East Norfolk is very limited and comprises only cremated remains, including two truncated, unurned deposits from the upper fill of the enclosure ditch at Bell Farm, one of which was radiocarbon dated to 1490–1280 cal BC (SUERC-71025). The only other examples relate to older excavation records. The cemetery of East Carleton, on the southern side of the Yare Valley, included five urned and four unurned burials (Wymer Reference Wymer1990). The pottery is dated as ‘later Bronze Age’, but accords well with Middle Bronze Age forms (Wymer Reference Wymer1990, 76–9). At Harford Farm, a single cremation burial within a bucket type urn was inserted between the inner and outer ditches of an Early Bronze Age disc barrow (Ashwin Reference Ashwin, Ashwin and Bates2000, 79). Further upstream along the river Yare, a biconical urn was ploughed out of a barrow at Bawburgh (de Caux Reference de Caux1942), and another bucket urn containing human remains comes from Sprowston (Wymer Reference Wymer1990, 79).

Beyond the case study area, one further cemetery at Earsham in the Waveney Valley (c. 13 km south of Norwich) has been excavated recently. Here, 28 cremation burials (14 in Middle Bronze Age urns) were interred within a ring-ditch only visible as a cropmark (Hogan et al. Reference Hogan, Mundin and Weston2007). Close to the Norfolk coast (c. 25 km north-east of Norwich), two cemetery plots of four and nine burials at Witton included both urned and unurned burials (Lawson Reference Lawson1983, 30–36).

In contrast to South Cambridgeshire there is a dearth of Middle Bronze Age inhumations recorded in East Norfolk. However, as discussed further below, this may be as much to do with poor bone preservation and the lesser scale of excavations and associated radiocarbon dating programmes as it is a genuine absence.

The broader picture (‘beyond the fens’)

Whilst few other areas to the south and east of the Fens have seen the scale of investigation that the case study areas have, there are a growing number of well-dated Middle Bronze Age sites and landscapes elsewhere in East Anglia (Figure 18). Notably, Tom Woolhouse (Reference Woolhouse2024) details a concentration of enclosures/field systems along the Suffolk Coast and reviews the evidence for potential Bronze Age land division across the rest of the county.

Figure 18. East Anglian Middle Bronze Age sites mentioned in the text: 1) Fordham Road, Suffolk; 2) Honington, Suffolk; 3) Leiston, Suffolk; 4) Martlesham, Suffolk; 5) Walton, Suffolk; 6) Trimley St Martin, Suffolk; 7) Pinewood, Suffolk; 8) Grimes Graves, Norfolk; 9) Swan’s Nest, Norfolk; 10) Earsham, Norfolk; 11) Stansted, Essex; 12) Ardleigh, Essex; 13) Brightlingsea, Essex; 14) St Osyth, Essex; 15) Heybridge, Essex; 16) Over/Barleycroft, Cambs; 17) Fenstanton, Cambs; 18) Brampton, Cambs; 19) Witchford, Cambs; 20) Ely, Cambs.

Along the north-western edge of the East Anglian uplands, extending north-east from the Cam Valley, Middle Bronze Age settlement sites are recorded at Fordham Road, Newmarket, Suffolk (Rees Reference Rees2017), and at Grimes Graves and Swan’s Nest in west Norfolk (Mercer Reference Mercer1981, 36–8; White Reference White2022). A probable enclosure complex has also been identified at Honington, Suffolk (Billington & Cox Reference Billington and Cox2021). Finally, a discrete ditched enclosure and settlement remains at Cam Drive, Ely, were situated on what was becoming, by the Middle Bronze Age, an island within the surrounding Fens (Billington & Phillips Reference Billington and Phillips2019).

The Fordham Road site particularly is comparable, morphologically, to the Cam Valley enclosures, whilst Swan’s Nest on the Breckland clays – an impressive double-ditched enclosure containing structures and traces of occupation – is reminiscent of enclosure sites in eastern Norfolk. Grimes Graves is known primarily through the extensive middens that cover large areas of the site, but the context and character of the settlement are poorly understood. The rich artefactual and faunal assemblages, however, suggests that the scale of the middens reflects a site of aggregation (Healy et al. Reference Healy, Marshall, Bayliss, Cook, Bronk Ramsey, van der Plicht and Dunbar2018) reminiscent of the CBC Site I enclosure system in South Cambridgeshire.

With the exception of South Cambridgeshire, the landscape that has seen most recent investigation is the Suffolk Coast. Whilst the area is plagued by poor preservation of occupation-related assemblages, a number of enclosures have been dated to the Middle Bronze Age. At Leiston (King Reference King2023; Clarke Reference Clarke2023), a pattern of enclosures replacing an early field system is recorded, analogous to Ormesby St Michael and Clay Farm/CBC. Recent excavations also provide evidence for enclosures, boundaries, and droveways, potentially forming extensive field systems at Martlesham (Woolhouse Reference Woolhouse2016), Trimley St Martin (Bollen Reference Bollen2024), and Walton, Felixstowe (Meredith & Mortimer Reference Meredith and Mortimer2023), in the Deben and Orwell valleys. Several field systems – Felixstowe particularly – are of more ‘typical’ co-axial form and comparable to those of the western fen edge and much of lowland England.

There is also a wealth of burial evidence from along the Suffolk Coast, much of it recently excavated. Only cremation burial is represented, although once again, very poor bone preservation means that the inhumation rite need not have been absent. Excavated sites include Walton, Felixstowe – where Early–Middle Bronze Age ‘open’ groups of cremation burials within the wider field system occur alongside one cremation group within a ring-ditch – and Pinewood, Ipswich, where there was an open cremation cemetery alongside an individual cremation burial within an Ardleigh-type ring-ditch (Sommers Reference Sommers2011).

The Tendring Peninsula on the Essex coast is well known for its Ardleigh-type ring-ditch cemeteries including St Osyth (Germany Reference Germany2007), Brightlingsea (Clark & Lavender Reference Clarke and Lavender2008), and Ardleigh itself (Brown Reference Brown1999). However, the character of the Middle Bronze Age landscape and the wider settlement context of the cemeteries are poorly understood, including whether land division comprised extensive field systems or discrete enclosures and enclosure systems. That said, just to the south, excavations at Heybridge in the lower Blackwater Valley revealed a discrete Middle Bronze Age enclosure with fencelines and unusual post-built ‘longhouses’ (Cullum Reference Cullum2023).

Finally, what of the uplands themselves, the central, largely clayland, plateau often referred to as the East Anglian Plain? Few well-dated sites are known here, and whilst metalwork finds and barrows/ring-ditches are recorded along the valleys that dissect the plateau, the traditional view is that these areas, with heavy soils, remained wooded throughout the Bronze Age and occupation was therefore much sparser (Martin Reference Martin, Davies and Williamson1999). As such, an enclosure recorded at Stansted (the MTCP Site) on the Essex claylands is an anomaly. Dating to c. 1700–1300 BC and formed by a combination of ditches and fencelines, it was associated with watering holes and pits and produced a substantial finds assemblage including over 2000 sherds of Deverel-Rimbury pottery (Cooke et al. Reference Cooke, Brown and Phillpotts2008). With palaeoenvironmental evidence suggesting widespread pasture and a notable lack of associated field systems, there are clear parallels with the case study areas.

Discussion

The recent combined excavations in South Cambridgeshire and, to a lesser extent, East Norfolk, have not only revealed many individual sites, but in some areas (most notably Clay Farm/CBC) have allowed landscape analysis in a much broader sense, too. Combined with the emerging picture from other parts of the region, most notably the Suffolk coast (Woolhouse Reference Woolhouse2024), this work has shed significant light on the ‘fragments’ of settlement and land division that Yates (Reference Yates2007) included in his gazetteer.

Settlement form and land division in the region is far more diverse than previously thought. In addition to areas of co-axial field system there is now evidence for different forms of ‘landmarking’ (as termed by Johnston Reference Johnston2021), including discrete settlement enclosures, enclosure complexes, post-defined enclosures, and boundaries, sometimes in place of, sometimes alongside, co-axial field systems. Looking beyond the comparatively well-studied sites of the western fen edge and major river valleys we can now consider how communities lived in and farmed different landscape zones, including the region’s uplands, and how people interacted with developing social landscapes. The burial evidence also changes how we understand mortuary practices within the region. Inhumations, often from unusual contexts, have previously been regarded as rare during the Middle Bronze Age (Brück Reference Brück2019, 42). Their increasing number in a variety of contexts, including substantial mixed-rite cemeteries, is therefore significant.

Contrasting landscapes

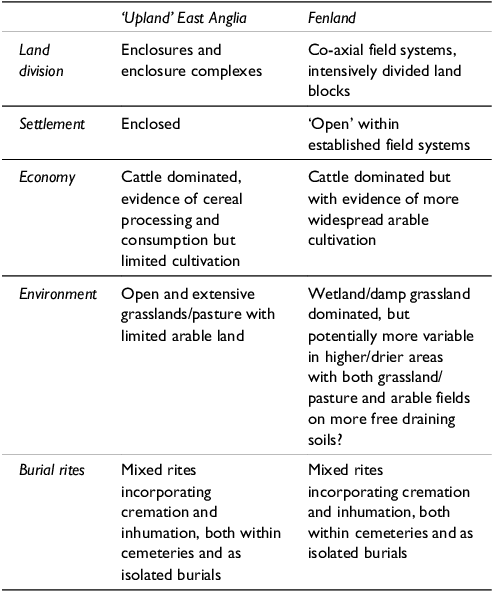

The landscape setting of each case study area differs, but both are located on the edge of the central East Anglian uplands (chalklands and claylands). Whilst also clearly river-focussed – extending along the Cam and the Wensum/Yare/Bure Valleys respectively –, it is this shared upland periphery location that is potentially most significant. Within these transitional zones and in some cases extending into the uplands, Middle Bronze Age land division and occupation is characterised by enclosures and enclosure complexes within largely open landscapes. Furthermore, these enclosures and the wider pattern of land division (or lack of) have proven key to understanding settlement dynamics, farming practices, and the environment. They represent a distinctly different Middle Bronze Age to that of the western fen edge and lower Ouse/Nene Valleys, which have often overly informed interpretations for wider East Anglia and beyond. The contrast can be seen most obviously in land division – enclosure/enclosure complexes compared to extensive co-axial field systems – but also in occupation context and subsistence practices (Table 6).

Table 6. ‘Upland’ East Anglia vs Fenland – key Middle Bronze Age traits.

Addressing firstly land division, there is evidence in South Cambridgeshire – most notably at Clay Farm/CBC – for early phases of co-axial field systems comparable to those of the western fen edge. The early phases of ditches at Ormesby St Michael and perhaps Postwick are also suggestive of a (potentially early) phase of field system in Norfolk. However, where chronology is well understood these early systems were short-lived, abandoned by the early/mid-15th century BC, and quickly replaced by enclosures and enclosure complexes. During this later phase there is a distinct shift towards enclosing specific areas and settlements within an open landscape rather than dividing or enclosing larger landscape blocks. In some respects these later enclosure forms have much in common with the true uplands of Britain, where enclosures and ‘cellular’ fields predominate. Nevertheless, the case study areas were also complex and coordinated landscapes, with networks of sites operating as communities, such as those to the south of Cambridge and around Horsford, Norfolk.

Where economic and environmental reconstruction is possible, the cattle-dominated faunal assemblages indicate specialised farming, whilst environmental evidence suggests that enclosures were set within extensive grasslands. The form and layout of several enclosures – most notably CBC Site I – and contemporary boundaries also reflect the importance of livestock management. In contrast to more open settlements sited amongst field systems elsewhere in lowland England, across the case study areas, settlements were invariably enclosed. They were defined by substantial ditches and banks designed to keep livestock out, and/or for keeping them in – such earthworks would no doubt have been striking landscape features that were easily defendable should the need arise. Many of the smaller enclosures, or individual ‘compounds’ within the larger enclosure complexes, apparently served more specialised functions related to livestock containment and management and may have been used only seasonally. Taken together, these networks of enclosures and associated boundaries suggest the movement of livestock and people as part of regimes that probably included gatherings and markets – at sites such as CBC Site I – at key points in the yearly cycle.

Farming practices are a likely factor in the emerging differences between the upland periphery of South Cambridgeshire and the western fen edge just to the north. Whilst cattle also formed the mainstay of Fenland Bronze Age farming, in contrast to South Cambridgeshire, palaeoenvironmental remains – particularly pollen – suggest that cereal cultivation played an important role as well (eg, Over/Needingworth Quarry; Neil et al. Reference Neil, Timberlake and Evans2017). Alongside the differing patterns of land division and the broader landscape character in each zone, this suggests a clear contrast. On one hand, there are more mixed agricultural regimes within extensive lowland and fen edge landscapes on lighter soils, divided by complex co-axial field systems (see also Evans et al. Reference Evans, Beadsmoore, Brudenell and Lucas2009, 63–4); and on the other hand, cattle-dominated economies operating within expansive upland periphery grasslands, shaped by enclosures, enclosure systems, and landscape-scale boundaries. Certainly, it seems that cattle and livestock were being managed in different ways in the respective zones. The enclosures and enclosure systems of South Cambridgeshire potentially represent a quite different ‘open range’ style of cattle farming, a system that is perhaps less recognisable than the ordered field systems recorded across the western fen edge and much of lowland England (Bradley Reference Bradley2019, 226; Tabor, with Phillips Reference Tabor and Phillips2024).

In the absence of an ‘exceptional’ site with large, well preserved, material assemblages such as Clay Farm/CBC, East Norfolk is more challenging to characterise. However, the similarity in the scales of enclosure, settlement, and land division with those of South Cambridgeshire potentially suggest a similar livestock-oriented economy here. Indeed, as evidence from wider East Anglia continues to grow, it can be argued that the Middle Bronze Age across much of the region is best understood in terms of enclosures and extensive open grasslands, rather than co-axial field system blocks and mixed agricultural regimes. Future work may also prove that the ‘central’ East Anglian Plain, especially its river valleys, were more widely utilised and settled than previously thought.

Naturally, there are exceptions and variation: the Suffolk Coast with its more ‘grid-like’ field systems might have seen significant arable activity and more mixed farming practices (Woolhouse Reference Woolhouse2024). Indeed, multiple forms of land division can coexist in some landscapes (cf. the cellular and rectilinear field systems of Dartmoor; Johnston Reference Johnston2021, 335). In this sense, we must understand the Middle Bronze Age at an individual landscape scale and not merely in terms of broad environmental and economic patterns. Furthermore, recent approaches to the Bronze Age have emphasised land tenure, kinship, and social relationships (Brück Reference Brück2019, 191–8; Johnston Reference Johnston2021, 322–3). As such, the enclosures and enclosure systems of East Anglia also reflect subtly different ways of negotiating social as well as physical landscapes. For example, the Early Bronze Age pond barrow and post-ring monument incorporated into the enclosure at Marleigh, South Cambridgeshire, surely represents re-definition and continuity of kinship and land tenure (see Bourne & Tabor Reference Bourne and Tabor2023). Similarly, the continued importance of earlier barrow monuments at Clay Farm and Worts’ Causeway is demonstrated by their incorporation into Middle Bronze Age land division and their association with settlement (see Cooper Reference Cooper2016a & b). Considering the landscape in this way also adds an extra dimension to the abandonment of early field systems and their replacement by enclosures at Clay Farm/CBC. As Brück (Reference Brück2019) and Johnston (Reference Johnston2021) have discussed, this evidence challenges traditional models of widespread Middle Bronze Age ‘colonisation’ through the establishment of co-axial field systems. Instead, the archaeological record reflects more complex and varied interactions with individual landscapes.

Varied rites

The most compelling recent funerary evidence from the region undoubtedly comes from South Cambridgeshire. The cemeteries at Worts’ Causeway and Hinxton demonstrate that within the Cam Valley, inhumation burial was widely practiced during the Middle Bronze Age alongside cremation burial. A varied tradition included inhumations, some with grave goods, together with urned and unurned cremation burials, occurring both in cemeteries (often focused on earlier Bronze Age barrows/ring-ditches) as well as individually. Burials occur in various contexts both within/close to settlements and across the wider landscape. In addition, disarticulated human bone from settlement contexts represents a further, less tangible, aspect to how the dead were treated.

This emerging pattern is partly shaped by the intensity of fieldwork, the scale of excavations, and the increasing use of radiocarbon dating for burials. Indeed, a similar pattern is apparent from recent work along the western fen edge and lower Ouse Valley. Here, alongside the long-recognised cremation cemeteries and singular cremation burials amongst contemporary field systems (eg, Evans et al. 2013; forthcoming), a growing number of inhumations are now recorded. Two isolated flexed inhumations were found amongst dispersed settlement remains at Over/Needingworth (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Tabor and Vander Linden2016), whilst three inhumations (in two graves) have been excavated as part of a larger Middle Bronze Age cremation cemetery on the river terrace at Fenstanton (Atkins Reference Atkins2024, 11). Further examples occur both in the Ouse Valley (eg, Scholma-Mason et al. Reference Mason, Rogers, Green and White2024, 11; Luke Reference Luke2016, 171–87) and on the Isle of Ely, Cambridgeshire (Phillips & Blackbourn Reference Phillips and Blackbourn2019).

The situation in East Norfolk and much of the rest of East Anglia is less clear. Here, cremation cemeteries take varying forms, from ‘flat’ cemeteries to ring-ditch/barrow associated cemeteries and the distinctive Ardleigh-type ring-ditch cemeteries. Occasional isolated cremation burials are also recorded. However, the degree to which inhumation forms part of the tradition(s) is not known. Furthermore, across much of eastern East Anglia there has simply not been the scale of investigation required to identify many ‘less visible’ burial rites.

In summary, unlike the apparent contrast in land division and settlement context, the region as a whole shares a varied burial tradition, comprising multiple rites and ways of commemorating the dead. Indeed, one of the key findings from recent excavations is the widespread practice of inhumation, as well as cremation, during the Middle Bronze Age. As per the findings from Caswell and Roberts’ (Reference Caswell and Roberts2018) comprehensive survey of Middle Bronze Age cremation burials, this varied rite goes some way to explaining why recorded Middle Bronze Age cemeteries likely represent only a small percentage of the population in any given area. At the same time, evidence from South Cambridgeshire suggests that contrary to Caswell and Roberts’ (Reference Caswell and Roberts2018, 344–5) assertion, cemeteries do occur near settlements and here at least there remains a strong case for the widespread existence of what might traditionally be regarded as community cemeteries. Indeed, forthcoming analysis of bone assemblages, including aDNA and isotope analysis, has significant potential to shed further light on this.

Conclusion

Looking at the wider picture of Middle Bronze Age East Anglia, almost all of the landscapes discussed in this paper – including the two case study areas – were identified by Yates (Reference Yates2007, 78–81) as areas where future work had the potential to reveal Bronze Age field systems and associated occupation comparable to other areas of lowland southern Britain. In many ways, recent work has proven these predictions to be correct. However, these ‘newly discovered’ Bronze Age landscapes are also different from the model of intensively divided landscapes which, in the eastern region, developed following the excavation of the western fen edge sites in the 1980s and 1990s, and it can be argued has perpetuated since. In addition, with the identification of an apparently widespread inhumation tradition forming part of a very varied range of rites, this recent evidence has transformed understandings of the region’s burial practices.

Given the pace of archaeological discovery witnessed in the eastern region/East Anglia over the last two decades, this synthesis is not intended to be exhaustive. Instead, its aim has been to highlight a ‘different’ East Anglian Middle Bronze Age; one that is gradually emerging from several key landscapes, and is changing the way we view the period’s land-use, settlement and farming practices, and burial traditions. As a result, not only do we need updated and more detailed synthesis of what is now a substantial archive, but also a more nuanced consideration of the evidence from the region and beyond.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2025.10075

Acknowledgements

This paper was funded by the CAU and the OA Research and Public Engagement Fund. Much of the fieldwork from the case study areas was carried out by the CAU and OA, and this study would not have been possible without the cooperation and support of the excavation and post-excavation project teams. The authors would particularly like to thank Anwen Cooper (OA) for continued support throughout the writing of the paper and for reading and commenting on various drafts. Nick Overton provided guidance on the recalibrating and presentation of radiocarbon dates. Thanks are also extended to Emma Beadsmoore, Tom Bourne, Matt Brudenell, Chris Evans, Richard Mortimer, Tom Woolhouse, and Lawrence Billington for sharing information and discussing interpretations. Graphics were produced by David Brown and Gillian Greer (OA) and Andrew Hall (CAU).