Introduction

Populism, beyond its electoral dynamics, has undoubtedly become an ever‐present buzzword in the political arena, on social media, in TV news, and everywhere people discuss politics (Hunger & Paxton, Reference Hunger and Paxton2021). After the ‘party‐gate’ scandal that marred the UK government in early 2022, The Guardian noted that ‘Boris Johnson prepares a populist offensive to save his skin’, criticizing the prime minister's supposedly populist agenda that includes ‘sending in the military to help tackle cross‐Channel migration’ and ‘training schemes for universal credit claimants’ (Stewart, Reference Stewart2022). Similarly, Donald Trump's ‘Save America’ speech on 6 January 2021, and Silvio Berlusconi's recent campaign to become the new President of the Italian Republic were widely described as populist (Damilano, Reference Damilano2022; Viala‐Gaudefroy, Reference Viala‐Gaudefroy2022). If these latter two examples seem easily justifiable, notably in terms of populist tropes such as anti‐elitism and demagoguery, the initial example feels more like a journalistic rhetorical frame.

Scholars of different fields have investigated populism for decades, trying to unveil its nature and describe its characteristics, providing a vast array of diverging definitions. Although academics still disagree on some features of populism, a consensus exists on its core characteristics, namely populism as a ‘thin’ ideology centred on anti‐elite and people‐centric beliefs (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004). This vision somehow contrasts, though sometimes is complementary, to interpretations of populism as mainly a set of rhetorical frames (Jagers & Walgrave, Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007) or a performative style (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2016). Beyond this primary definition, as we discuss below, a set of second‐order features characterize the debate on populism. In particular, studies focused on the link between populism and nationalist, xenophobic attitudes, or leftist, demagogic postures, as well as bad political manners, or even commendable attention to the needs of the people (Caiani & Graziano, Reference Caiani and Graziano2019; De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Reference De Cleen and Stavrakakis2017; Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2017).

Within this variegated framework, populism and those political actors identified as populist, suffer from a normative disadvantage. Populists are often stigmatized by citizens and the media for their alleged demagogic and deceitful approach to politics, their supposed incoherence or incompetence and their more aggressive rhetoric (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2022). Still, positive attributes – charisma, closeness to the average citizen, a more genuine political style free of those ‘politically correct’ norms that render mainstream politics so inefficient – are ascribed sometimes to populists (Canovan, Reference Canovan2005).

Populism, in other terms, is often equated with a wide palette of attributes and can be easily weaponized by its proponents or detractors, depending on the political frame they pursue. Examples of these competing normative frames abound: Casiraghi and Bordignon (Reference Casiraghi and Bordignon2023) showed how in European Parliaments left‐wing politicians are accused of populism more often when the political discussion centres on economic issues, whereas their right‐wing colleagues are attacked more frequently when the debate concerns immigration. Adopting a similar focus, Elmgren (Reference Elmgren2018) demonstrated how the Finnish Rural Party proudly claimed populism as one of its positive characteristics, whereas Casiraghi (Reference Casiraghi2021) showed how the British Conservatives systematically refused to be defined as populist.

Despite this wealth of research, populism remains a fluid concept – ‘a pathology, a style, a syndrome and a doctrine’ (Stanley, Reference Stanley2008, p. 95). Is Boris Johnson a populist? Are Trump and Berlusconi? It is not our aim to answer these questions, and a widespread literature exists already that addresses the matter of classifying populist movements (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019). Yet, these questions – and their answers – shed light on a theoretical and empirical puzzle that has received scant attention so far: What causes voters to perceive a political actor as populist?

Although scholars recently moved the focus from the nature and characteristics of populism to how political actors identify populism (e.g., Casiraghi & Bordignon, Reference Casiraghi and Bordignon2023), no study so far has addressed how citizens perceive populist politicians and attitudes. For sure, studies have analysed the relation between the public and populism, for instance investigating how populist rhetoric influence voters (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Schemer, Corbu, Hameleers, Andreadis, Schulz, Schmuck, Reinemann and Fawzi2020) or what factors increase support for populist parties (Spruyt et al., Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Droogenbroeck2016). From a different perspective, scholars have measured populist attitudes among voters (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014) and linked such postures to various political preferences, like conspiratorial thinking (Balta et al., Reference Balta, Kaltwasser and Yagci2022) and economic policies (Guiso et al., Reference Guiso, Herrera, Morelli and Sonno2017). Hence, although we have evidence about why citizens vote for populist parties and who is more likely to adopt populist attitudes, a gap still characterizes the identification of the factors driving voters to identify a political actor as populist.

We will address this as well as whether there is systematic heterogeneity in the evaluation of candidates among citizens according to their individual characteristics. In particular, we focus on three sets of attributes, which broadly reflect the complexity of their ‘mind’ (Van Hiel et al., Reference Van Hiel, Onraet and Pauw2010): Cognitive characteristics (education, political interest), ideological characteristics (ideological proximity) and attitudinal characteristics (populist attitudes, trust in political institutions). To this end, we report results of a conjoint experiment embedded in a survey administered to a nationally representative sample of Italian citizens. Respondents evaluated different political statements by fictive politicians, of whom we manipulated relevant attributes, and decided whom of the two politicians they would consider more populist. Italy stood out as a relevant case study, as various kinds of populist actors have emerged powerfully in the Italian political arena recently. Overall, our results indicate two trends: (i) more than the profile of politicians, what matters for them to be identified as populists is their rhetoric. (ii) The cognitive and ideological profile of respondents is largely inconsequential; instead, populist voters are substantively less likely to identify populism as such.

The article is structured as follows. The next section lays out our theoretical framework and expectations. The third section presents our data and method, highlighting the details of our survey and analysis. The fourth section discusses our findings, whereas the conclusion offers some implications and sketches avenues for future research.

Populism in the eye of the beholder?

Arguably, different citizens should perceive populism, and populist rhetoric, differently. This does not imply, of course, that such perceptions are exclusively driven by the profile of the observer – rather, the nature of candidates and rhetoric employed is likely to drive perceptions of populism in the first place. With this in mind, we develop our theoretical discussion as a two‐step argument: (i) The characteristics of politicians and their rhetoric are likely associated with them being perceived as populists (our ‘baseline’), and (ii) this differs depending on citizens’ cognition, ideology and political attitudes.

Although we explore a mostly uncharted territory, we also derive our argument from previous studies that investigated the relation between voters and populism. For instance, scholars demonstrated that anti‐elitist, people‐centric attitudes increase support for populist parties (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014) and that populist rhetoric is more appealing to the ‘lower educated and the politically cynical’ (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Van Der Brug and de Vreese2013). Our argument and experimental design resonate with these previous studies, although adopting a new focus and employing an innovative methodological approach. Indeed, we rely on a conjoint framework and we depart theoretically from the issue of how populist are citizens (or when populist messages are effective) to address the conditions under which citizens perceive politicians as populist.Footnote 1

The baseline: Populist rhetoric and candidate characteristics

We argue that the public should perceive populism mainly through the rhetoric employed – the statements that politicians express – considering whether the scope of such rhetoric is demagogic, anti‐elite, people‐centric or politically incorrect, amongst other features (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Schemer, Corbu, Hameleers, Andreadis, Schulz, Schmuck, Reinemann and Fawzi2020). As said regarding populism's core characteristics, we focus on the two crucial components of populist rhetoric: anti‐elitism and people‐centrism (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004). Anti‐elitism is historically associated with populist stances and movements: Casiraghi (Reference Casiraghi2021) showed how since 1970 British parliamentary discourses on populism have highlighted the anti‐elitist character of populism. From a strategic standpoint, this makes sense: Populists tend to stand outside of the political establishment, and the public should identify their oppositional anti‐elitism for what it is (Maurer & Diehl, Reference Maurer and Diehl2020).

Moreover, populism seems to go hand in hand with rhetorical aggressiveness. Across the world, populists seem to take pleasure in displaying ‘bad manners’, a more uncivil and ‘low’ style of politics, and more frequently use an ‘offensive’ discourse ‘filled with invectives, ironies, sarcasm, and even personal attacks’ (Corbu et al., Reference Corbu, Balaban‐Bălas, Negrea‐Busuioc, Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Strömbäck and Vreese2017, p. 328). Indeed, evidence suggests that populists introduce ‘a more negative, hardened tone to the debate’, relying on negative campaigns centred on anti‐elite rhetoric (Immerzeel & Pickup, Reference Immerzeel and Pickup2015, p. 350).

On the other hand, studies demonstrated how people‐centric messages are another fundamental characteristic of populist rhetoric (Canovan, Reference Canovan2005). Here, populist politicians frequently find supporting ideologies and strategic incentives to convey political statements that provide the public with an enhanced level of political relevance (Zaslove et al., Reference Zaslove, Geurkink, Jacobs and Akkerman2021). Hence, politicians who voice statements that clearly employ an anti‐elite or people‐centric rhetoric should be perceived as more populist compared to politicians that express more ‘classic’ political claims.

However, the rhetoric of candidates may not be the only feature that paints them under a populist light. Second‐order features are also important to define what populism is and to investigate which factors should drive citizens to perceive political actors as populist. In particular, the intrinsic characteristics of who they are might play a role. We focus on three factors: first, their ideological profile likely participates in whether voters construe them as populists. Evidence suggests that populism exists on both sides of the political spectrum. On the left, parties have been often accused of populism, from Latin American populism (Weyland, Reference Weyland2001) to more recent examples, such as Podemos in Spain or the Five Star Movement (M5S) in Italy (Caiani et al., Reference Caiani, Padoan and Marino2021). Such accusations, or descriptions, regard most often their attitudes towards economic policies such as opposition to trade openness and anti‐establishment positions (Van der Waal & de Koster, Reference Van der Waal and de Koster2018). Yet, populism seems traditionally associated more tightly with the (radical) right. According to the so‐called ‘populist hype’, the public, the media and political actors alike associate populism with radical‐right, nationalist attitudes (Glynos & Mondon, Reference Glynos, Mondon, Cossarini and Vallespìn2019) – a thesis supported by how right‐wing parties in Europe and beyond have adopted strong, controversial stances on topics such as immigration and European integration (Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2005). Therefore, we expect that right‐wing politicians are more likely than their left‐wing colleagues to be perceived as populist.

Second, which nuances the first point, beyond politicians’ ideological stance their ideological extremism could be associated with the public perceiving them as populists. Here, the extreme–mainstream divide, more than the right‐left cleavage, may be decisive: citizens would identify moderate, mainstream parties as less populist than extreme parties, describing a U‐relation between populism and ideology (Rooduijn & Akkerman, Reference Rooduijn and Akkerman2017). This resonates with recent research on the use of aggressive rhetoric in elections worldwide. For instance, Nai (Reference Nai2020) showed that more extreme candidates, on the left and right, are significantly more likely to ‘go negative’ on their rivals. Similarly, Casiraghi and Bordignon (Reference Casiraghi and Bordignon2023) demonstrated that ‘extreme’ politicians, in particular in the extreme left, are more often accused of populism in parliamentary debates compared to their centrist colleagues.

Third, a case could be made that male politicians are more likely to be labelled as populist than their female counterparts. Evidence exists that citizens ascribe positive or negative characteristics to political candidates also as a function of gender, mostly due to entrenched stereotypes (Bernhard, Reference Bernhard2022; Koch, Reference Koch2000). On populism, its inherent aggressiveness – in terms of greater reliance on hostile rhetoric (Nai, Reference Nai2021) – could be more easily associated with masculine leadership traits. This is in light of the fact that women in politics tend traditionally (and stereotypically) to be perceived ‘as warm, people‐oriented, gentle, [and] kind’ whereas men are more usually seen as ‘tough, aggressive, and assertive’ (Banducci et al., Reference Banducci, Gidengil, Everitt, Semetko and Scammell2012, p. 165). This conclusion seems also supported from a descriptive standpoint, as supposed populists tend to be overwhelmingly male. For every Meloni, there are many Berlusconi, Grillo and Salvini. For every Le Pen, there are many Zemmour and Mélenchon.

Finally, since much of the populist, anti‐elite rhetoric negatively targets professional politicians – those that spent their entire career as politicians – we focus on the previous occupation of our fictional politicians. While cases abound of ‘professional’ politicians with a clear populist profile – from Salvini in Italy to Le Pen in France – the critique against ‘system’ elites remains a core feature of populist rhetoric. Surfing on the general discontent of the more cynical part of the electorate with ‘politicians’ as a social category (Fieschi & Heywood, Reference Fieschi and Heywood2004), populists often strive to frame their profile as not being part of traditional politics – for instance, highlighting their non‐political origins (e.g., in business, as for Trump). Therefore, framing a political figure as ‘not a professional politician’ should be expected to echo populist tropes (Peters & Pierre, Reference Peters and Pierre2019). To summarize, we expect as a ‘baseline’ trend that anti‐elitist and people‐centrist rhetoric as well as candidates on the right, more extreme, male, and who are not professional politicians, are more likely to be perceived as populist.

Citizen characteristics

Populism is likely to be in the eye of the beholder as well. We know what the characteristics of voters are that drive them to support populist actors (e.g., lower education, lack of political trust), but no study has yet investigated whether the same features drive citizens’ perceptions towards populism. Hence, we build our expectations on what previous literature has suggested regarding individual support for populism, and we integrate such evidence with novel expectations. In particular, we focus on three factors: cognitive, ideological and attitudinal. First and concerning cognitive factors, we believe that voters with lower levels of education and interest in politics are less likely to identify populism as such. The rationale for supporting this expectation comes from research in both cognitive and political psychology and recent trends in information processing. Research showed that low education is linked to voters with lower political knowledge, lesser systematic reasoning and weaker higher order and critical thinking (Galston, Reference Galston2001; Grönlund & Milner, Reference Grönlund and Milner2006; Miri et al., Reference Miri, David and Uri2007).

Among other dual models of reasoning, the elaboration‐likelihood model of persuasion (ELM: Petty & Cacioppo, Reference Petty and Cacioppo1986) formalizes explicitly the role of factual knowledge in reasoning. According to ELM, the capacity of individuals to engage in issue‐relevant thinking (‘elaboration’ in ELM) stems from a combination of high motivation (interest) and the ability to process the information received (O'Keefe, Reference O'Keefe, Dillard and Shen2013), itself a function of prior knowledge and education. In other terms, as described in the heuristic‐systematic model (Todorov et al. Reference Todorov, Chaiken, Henderson, Dillard and Shen2002), complementary to the ELM, high levels of understanding and previous knowledge about a matter are instrumental in evaluating the validity of new information. The role of education and knowledge as the catalyst for a ‘deeper’ evaluation of political information is supported by research investigating the processing of ‘extra‐factual’ information (Greenhill, Reference Greenhill2019). Notably, a positive association between low education levels and susceptibility to disinformation (Buchanan, Reference Buchanan2020; Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Ryu and Jeong2021), effectiveness of political persuasion and beliefs in conspiracy theories (van Prooijen, Reference Van Prooijen2017) has been shown – suggesting that low education and knowledge are associated with poorer information processing. Taken together, these research agendas suggest that high levels of education and interest provide incentives to think deeply about the matters at stake and new information, whereas low levels make individuals more likely to fall prey to manipulation and information distortions.

Hence, given the ‘thin’ and fluid character of populism, to the point that scholars themselves often disagree on its facets, we expect the evaluation of ‘populism’ across citizens to vary based on their education levels and political interest. For sure, we are not arguing that low levels of political sophistication are associated with weaker processing of populist information – actually, the reverse case could be made. Instead, our argument is that higher cognitive skills are required for the analytical side of information processing – that is, identifying populist rhetoric as such, regardless of whether this information was perceived positively or negatively (the evaluative side of information processing). In this sense, education can be expected to foster greater analytical skills, necessary for the correct identification of a phenomenon, regardless of its evaluation (and effectiveness).

Second and concerning ideological factors, we focus on citizens’ political preferences. Voters should be influenced by their own preferences so that ideological proximity with a candidate should lead to more positive evaluations. The rationale supporting this expectation is straightforward: Research in information processing, political cues and the moderating role of individual ideological profiles has shown that voters tend to engage in ‘motivated reasoning’ (Taber & Lodge, Reference Taber and Lodge2016), through which ideologically congruent information is evaluated more positively and incongruent information is discounted. For instance, people tend to read newspapers that are ideologically closer to them (Curini, Reference Curini2022), if only for a confirmation bias.

Indeed, studies showed that ideological proximity is a primary heuristic cue to infer judgments about political leaders (Knobloch‐Westerwick et al., Reference Knobloch‐Westerwick, Mothes, Johnson, Westerwick and Donsbach2015; Lockwood, Reference Lockwood2017). For example, comparing a series of surveys among U.S. respondents, Nai and Maier (Reference Nai and Maier2021) claimed that conservatives are more likely than liberals to evaluate Trump as scoring high in conscientiousness, but less likely to score him high on narcissism or psychopathy.

Hence, because ideological proximity should naturally lead to more positive evaluations, and populism can intrinsically be considered a normatively challenged concept, we expect heterogeneity in citizens’ evaluations of populism according to their relative ideological proximity (distance) from a given politician. Such a rationale reflects well‐known social identity dynamics, where the (political) out‐group is more likely to be assigned negative stereotypes (Mason, Reference Mason2018), and because the political out‐group is negatively construed it becomes automatically more salient and noteworthy (Soroka, Reference Soroka2014).

Finally, and concerning attitudinal factors, we focus here on two attitudes related to how citizens engage with politics: populist attitudes and trust in political institutions. Our argument is that populism is frequently seen as antithetic to the ‘liberal’ definition of democracy (Mueller, Reference Mueller2019; but see Mudde & Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2012), and that should be easily identifiable especially among the supporters of the latter (low populist attitudes, high trust), again according to the negativity bias (Soroka, Reference Soroka2014). Indeed, populist voters should be more likely to support populist candidates (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Zaslove et al., Reference Zaslove, Geurkink, Jacobs and Akkerman2021). Beyond the overlap of their (thin) ideological frames, consistent research on the role of personality traits in politics suggests the existence of congruence between the personality of leaders and their followers. According to the ‘homophily’ hypothesis, individuals with congruent personality profiles tend to be attracted to each other (Selfhout et al., Reference Selfhout, Burk, Branje, Denissen, van Aken and Meeus2010). In politics, this translates into voters being predisposed to like candidates with a character that matches theirs (Caprara & Vecchione, Reference Caprara and Vecchione2017).

In addition, the trust the people put in the parliament, usually the most important representative, a democratic institution in democracies, could influence their perception of populism. Previous studies have shown how trust in political institutions negatively correlates with populist attitudes (Eberl et al., Reference Eberl, Huber and Greussing2021). Consequently, we expect to find a sub‐group heterogeneity with respect to citizens’ populist attitudes and their relative degree of trust towards democratic institutions in general.

Method

Data and sample

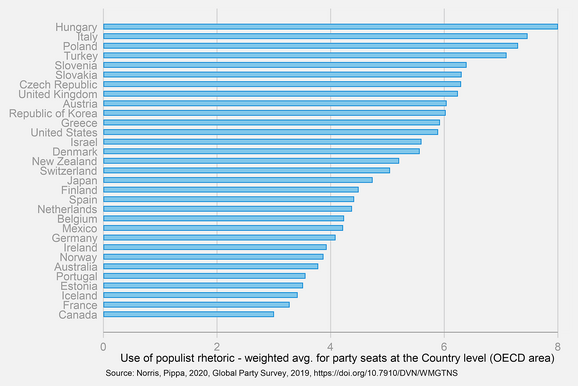

We test our hypotheses with experimental data gathered via a survey distributed by Demetra to a representative sample of Italian citizens (N = 1,000) in early 2022. As populism can assume diverse forms and vary on different degrees, we decided to focus on a country that experienced great variation in terms of populist political actors and topics discussed in the political arena. In the last decade, Italy saw the emergence of one of the most successful, standard case of a populist party, the M5S, a left‐inclining and widely heterogeneous party that since 2013 obtained many electoral victories (Mosca & Tronconi, Reference Mosca and Tronconi2019). On the other hand, right‐wing actors with different policy positions, such as on immigration and economic affairs, were identified as populist. For instance, both Forza Italia and the League were consistently accused, and more rarely praised, for their populism by scholars and media alike (Albertazzi & McDonnell, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2005; Bobba, Reference Bobba2019). Overall, according to our analysis of the database recently introduced by Norris (Reference Norris2020), Italy figures as second in terms of the use of populist rhetoric among OECD countries (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The relevance of populist rhetoric across OECD countries. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Italy is, hence, an interesting case for the investigation of how citizens identify populism. On the one hand, the large prevalence (and variety) of populism and populist actors in this country could make this case conservative. Certainly, it is much easier to identify phenomena when they clearly stand out from the norm. Similarly, identifying populists specifically in a setting where populism is prevalent should be comparatively harder than in other countries where populism is a more marginal phenomenon. Specifically, it should be harder in Italy, compared to other countries, to identify the presence of populism only based on ideological cues, given the widespread presence of populism on both political sides.

On the other hand, voters should be more familiar with the content of populist rhetoric, making it easier for them to identify it as such. Overall, Italy seems to represent both a hard‐case scenario likely to produce conservative estimates (for the identification of populism via ideological cues) and an easier scenario for the identification of populist rhetoric. While this likely makes it harder for our results to replicate fully outside of the Italian case, the variety of populism here offers a valuable setting for the unfolding of our conjoint design, making all combinations about equally likely.

Manipulation

We presented respondents with a vignette in a fully randomized conjoint framework. Conjoint designs allow researchers to study the independent effects on respondents’ preferences of many features of complex multidimensional objects (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014), as the evaluation of populism is. Indeed, conjoint analyses, and vignettes more broadly, are particularly useful when defining a concept theoretically is controversial, as clearly is the case for populism, and hence a bottom‐up approach – that is asking the people – may provide a decisive contribution (King & Wand, Reference King and Wand2007). Here, our results allow scholars to pinpoint more effectively the core and second‐order features of populism, adopting the novel perspective of which factors drive citizens to define a politician as populist. Moreover, such an approach is well suited to detect any systematic heterogeneity in respondents’ evaluations according to specific sub‐group characteristics, therefore allowing us to explore the possible role played by informative, ideological and attitudinal factors. Finally, by precisely abstracting away from real‐world contexts, an experiment like ours could prevent voters’ in‐built biases being quite as prevalent as they would be otherwise, improving the quality of the ‘signal’ we detect.

With respect to result estimation, following Leeper et al. (Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020) we computed the ‘marginal means’ (MM), which do not depend on an arbitrarily selected reference category, contrary to the ‘average marginal component effect’. This makes ‘marginal means’ more appropriate when the aim is to run a comparison of subgroup preferences. In particular, in our experiment we randomly generated two candidate profiles, displayed next to each other; respondents had to decide which of the two profiles they consider as ‘more populist.’ Based on these answers, we run a discrete‐choice conjoint analysis (Martini & Olmastroni, Reference Martini and Olmastroni2021). In our forced‐choice design with two alternatives, MM has a direct interpretation as probabilities, hence reflecting the probability of a profile being selected when it contains a certain level averaged over all remaining attributes. Moreover, since each respondent made two comparisons (i.e., two different sets of competing profiles), we account for the non‐independence of observations by using clustered standard errors at the respondent level.Footnote 2

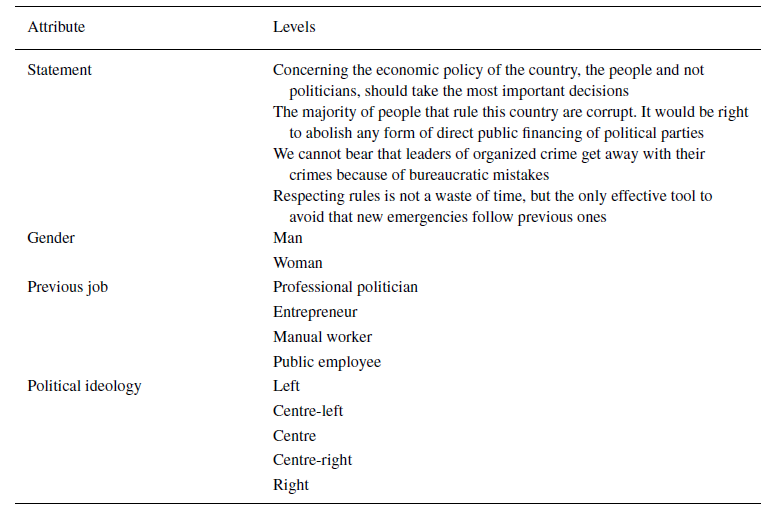

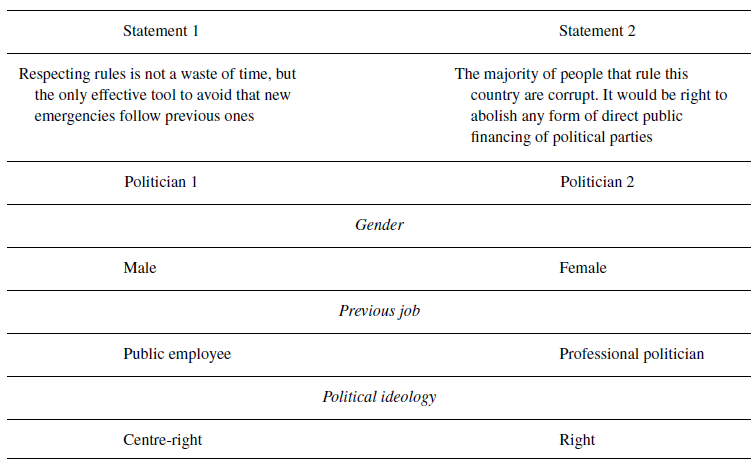

Each profile consists of attributes (e.g., gender) which can take different levels (e.g., male or female). Which level a certain attribute takes is fully randomized uniformly (i.e., with equal probabilities for all levels in a given attribute) and independently from one another (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins, Yamamoto, Druckman and Green2019). Following the different dimensions of candidate selection described above, we use four attributes for describing the candidate profiles. The first attribute is related to rhetoric. Here, we selected two highly populist and two not populist statements: as shown in Table 1, which lists all levels and attributes, we followed the mainstream literature on populism and selected an anti‐elite statement (‘all politicians are corrupted’) and a people‐centric claim (‘the people should decide on important political matters’). The selection is particularly based on previous studies on the core characteristics of populism (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004) and on how scholars have measured populist attitudes (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014). The other two statements are non‐populist, classic political claims about the need to respect rules and to assure that organized crime is prosecuted.Footnote 3 Finally, and as mentioned, the three other politicians’ attributes are related to their ideologies, previous job and gender.Footnote 4

Table 1. Statements and politicians’ attributes (conjoint profiles, independent randomization)

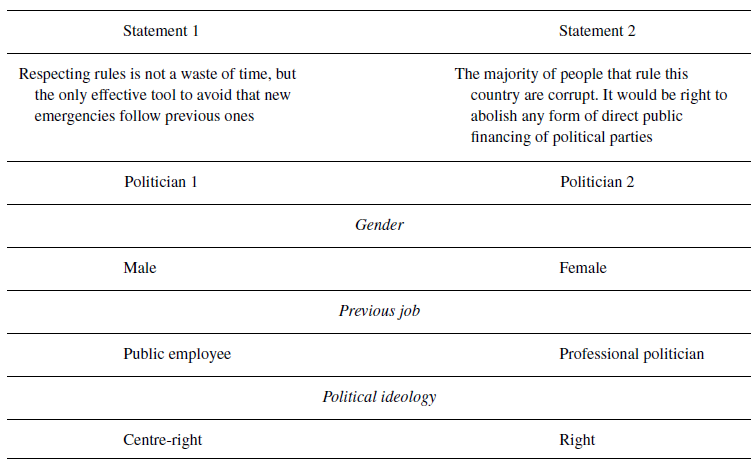

All the four statements we employ are political statements and, hence, beyond manipulating the presence of a populist frame, we inevitably vary as well their focal topic (i.e., corruption, crime, respect of laws, and economic policies). This may raise questions about information equivalence. However, a realistic setting with real political claims inevitably involves more than one dimension, and this solution is certainly preferable to a vignette with fake, neutral and mostly similar statements (Dafoe et al., Reference Dafoe, Zhang and Caughey2018). Summing up our approach, Table 2 presents an example of a possible comparison.

Table 2. Example of conjoint vignette

Measures

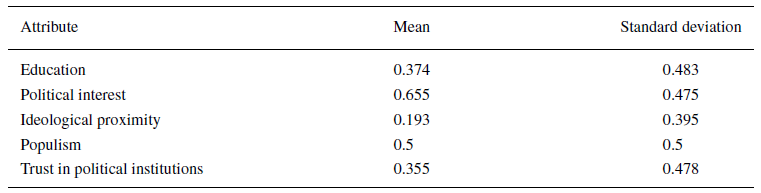

Before seeing the vignettes, respondents answered questions on their socio‐demographic status, and questions to identify their cognitive, ideological and attitudinal profiles. For cognitive attributes, we operationalized ‘level of education’ as a dummy variable, equals to 1 if the respondent has at least a college degree and 0 otherwise, while ‘political interest’ is a dummy, equals to 1 if the respondent is highly or quite interested in politics and 0 otherwise. Regarding ideological proximity, we first recoded the original 0–10 left‐right self‐placement question into a five‐categories variable to match the five ideological categories of the politicians presented in the vignette (0–2: left; 3–4: centre‐left; 5: centre; 6–7: centre‐right; 8–10: right). Hence, a respondent gets a value of 1 for ideological proximity if they share the same ideological position of the vignette politicians (i.e., right vs. right; centre‐right vs. centre‐right; etc.), and 0 otherwise.

Finally and concerning attitudinal attributes, we measured the populist attitudes of the respondents via two questions focusing on anti‐elite and people‐centric populism. Following Akkerman and colleagues’ survey (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014), we asked respondents how much (on a 0–4 scale) they agreed with the statements, ‘The people, and not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions’ and ‘What people call ‘compromise’ in politics is really just selling out on one's principles.’ Then, via a factor analysis, we computed a factor score to get a synthetic measure of populism for each respondent. Those respondents who were above the median value of the resulting populist score are then coded as 1 (i.e., high populism), and the remaining as 0 (i.e., low populism).Footnote 5 For trust in political institutions, we used a question related to trust in the Italian Parliament recoded as 1 if the respondent on a scale from 0 (no trust) to 10 (total trust) gives an answer larger or equal to 6, and 0 otherwise.Footnote 6 Table 3 summarizes the descriptive statistics of these variables.Footnote 7

Table 3. Characteristics of respondents: Descriptive statistics

Results and discussion

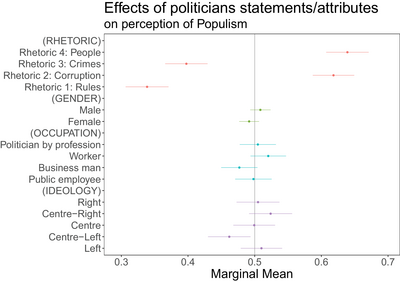

Figure 2 presents our MM analysis for all attributes, where the dependent variable is a dummy for whom of the two politicians in the vignette respondents consider more populist. As shown by the first attribute – the statement the politician makes – respondents identify a strong populist claim, on either economic policy or corruption, and either people‐centric or anti‐elite, to be a powerful driver in deciding whether a politician is populist. For example, averaging across the other features of the object included in the design, the MM for a politician's profile using the rhetorical sentence ‘People’ is 0.64 (i.e., a profile in which the rhetorical sentence of the politician is ‘People’ is selected with a probability of approximately 0.64). This translates into a 0.31 percentage points increase in being identified as populist compared to when a politician uses the rhetorical sentence ‘Rules’. Hence, rhetoric, and populist rhetoric, does matter. It is worth noticing that there is no significant difference between the effect of the two populist statements (i.e., ‘People’ and ‘Corruption’: difference: 0.02; SE 0.02; t‐value: −0.91). Hence, public perceptions confirm the intuition of previous literature about the dual, core nature of populism centred on anti‐elite and people‐centric positions.

Figure 2. Who is a populist? Note: Horizontal lines are 95 per cent confidence intervals based on respondent‐clustered standard errors. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Not only is rhetoric crucial for how the public identifies populism but is (almost) the only feature that matters. Looking at other variables, in almost every case the estimated impact is close to the benchmark of 0.5, therefore pointing to their substantial irrelevance. The only partial expectation is ideology: Politicians from the centre‐left are identified as less populist, compared to both the centre‐right and the two extremes, but not to their centrist counterparts.Footnote 8 Hence, it seems that both the ‘populist hype’ and the perception that populism is more diffused among extreme political actors play a role, although marginal, in forming citizens’ attitudes towards populism.Footnote 9 However, such an effect is considerably smaller than the one observed between populist and non‐populist statements.Footnote 10 Similarly, there are no differences between professional politicians and colleagues with other previous jobs. The same applies to gender, highlighting the irrelevance of such characteristics.

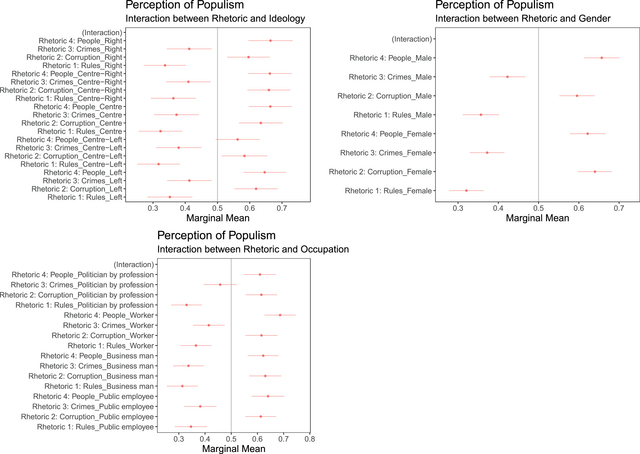

Hence, populism is essentially a rhetorical matter in the eye of the public and the relevance of rhetoric is not mediated by other attributes (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). In Figure 3, indeed, we assess the possible existence of heterogeneity across conjoint features, investigating if the causal effect of one attribute (in our case: politician's rhetoric) may vary depending on what value another attribute is held at. Figure 3 shows that the relevance of rhetoric is rather stable, irrespective of other attributes’ levels. In the top‐left graph, for instance, the interaction between rhetoric and politicians’ ideology shows no significant differences across the entire spectrum. Counterintuitively enough, this important finding supports the intuition that, at least in the eyes of citizens, populism is mainly a rhetorical phenomenon, largely disconnected and independent from political ideology, gender, and other personal traits of supposedly populist politicians.Footnote 11

Figure 3. Interactions between Rhetoric and politicians’ other attributes. Note: Horizontal lines are 95 per cent confidence intervals based on respondent‐clustered standard errors. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Sub‐group analysis

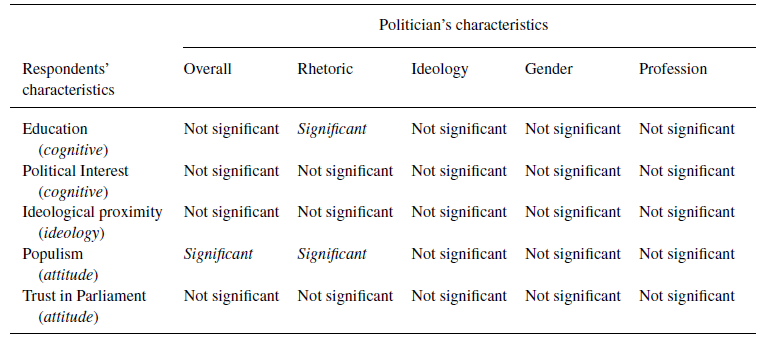

We now investigate whether there is any systematic heterogeneity in the evaluation of candidates among respondents. Following Leeper and co‐authors (Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020), we tested for group differences in preferences via an F‐test. Such an analysis runs a nested model comparison between a regression that includes interaction terms between a given subgrouping covariate (say education) and all feature levels (the rhetoric of a politician, her gender, etc.) and a model without such interactions. The former model generates estimates of level‐specific differences in preferences via the coefficients on the interaction terms. The nested model comparison, on the other side, provides an omnibus test of sub‐group differences. For example, this comparison can reveal if there are sizeable or only a few statistically apparent differences in preferences between two groups (e.g., high vs. low level of education). Formally, a nested model comparison provides an F‐test of the null hypothesis that all interaction terms are equal to zero (i.e., whether a model t that accounts for group differences better fits the data than a model of support with only conjoint features as predictors). Table 4 reports the main findings of such tests.

Table 4. Sub‐group characteristics: F‐test results

As shown, most citizens’ characteristics are not relevant in explaining how they identify populism. Contrary to our expectations, and to what previous literature has suggested regarding individual support for populism, for ideological proximity,Footnote 12 education, political interestFootnote 13 and trust in political institutions,Footnote 14 the resulting F‐test for the model comparison again gives us little reason to believe that there are sub‐group differences, at least at the 95 per cent confidence interval. That is, respondents largely agree on which dimensions are important in defining a populist politician, irrespective of the values of the above variables.

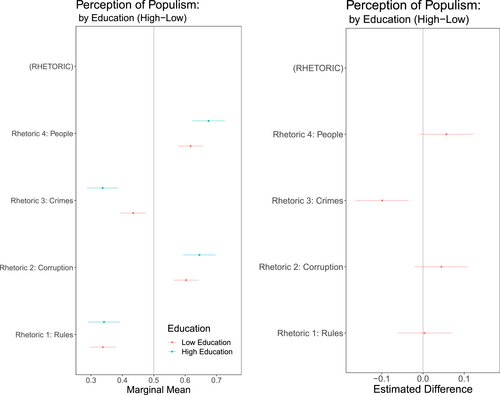

On the remaining respondents’ characteristics, we detect a significant effect of the education variable, but only on the rhetoric feature of politicians (see Table 4). As Figure 4 shows, respondents who have a college degree construe the non‐populist statement on crimes as significantly less populist than their less educated homologues. As we claimed, and supporting our theoretical expectation, education should foster greater analytical skills that drive highly educated respondents to identify a complex phenomenon as populism more accurately. In addition, they also seem more likely (see Figure 4) to identify as populist the statements on corruption and people (although the coefficients fall short of reaching statistical significance at the 95 per cent level, they are indeed in the right direction), hence again, not disproving the association between higher education and a more accurate identification of populism.

Figure 4. Conditional marginal means (left panel) and differences in conditional marginal means (right panel) of politicians’ rhetoric, by education. Note: Estimates are MM conditional on the respondents’ education. Horizontal lines are 95 per cent confidence intervals based on respondent‐clustered standard errors. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

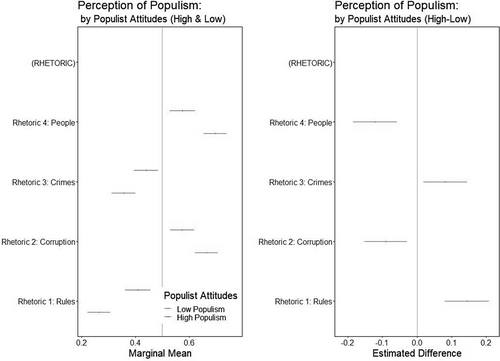

The only relevant sub‐group characteristic that shows an overall significant F‐test is that on populism, F(12, 3,976, p < 0.000). This cross‐respondent variation is entirely driven by differences in sensitivity to politicians’ employed rhetoric: F(4, 3,992, p < 0.000). Accordingly, Figure 5 shows the comparison of preferences as differences in sub‐group MM between the two groups (populist and non‐populist respondents) for the rhetorical features. The two groups have different preferences, as shown by the pairwise difference in means. In particular, populist respondents tend to interpret anti‐elite and people‐centric statements as far less populist compared to their non‐populist fellow citizens, while, and interestingly, the opposite happens with the other two non‐populist statements. A rhetoric framed on crimes and the rule of law is generally less likely to be perceived as populist (left‐hand panel), in particular for voters low in populist attitudes. Overall, voters high in populist attitudes have a much less polarized opinion about populist rhetoric, while being comparatively less likely to perceive as such populist statements framed in terms of people‐centrism and anti‐elitism.

Figure 5. Conditional marginal means (left panel) and differences in conditional marginal means (right panel) of politicians’ rhetoric, by populism. Note: Estimates are MM conditional on the populism rate of the respondent. Horizontal lines are 95 per cent confidence intervals based on respondent‐clustered standard errors. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

These findings provide engaging insights: first, the irrelevance of respondents’ personal traits and political attitudes (i.e., their cognitive and ideological profile) casts a shadow on the diffused perception among academics and the media that factors such as political ideology or trust matter in how people identify and relate to populism. From a normative standpoint, they also suggest (indirectly) that elitist interpretations of populism as a phenomenon affecting the uneducated masses, but only truly understood by enlightened elites, are likely simplistic. While our results do not speak in terms of differences in the effectiveness of populist tropes, they nonetheless seem to indicate that few are cognitive misers when it comes to identify them. Whether this result replicates in other contexts, notably where the prevalence of populism and populist tropes is less widespread than in the Italian case, remains an interesting empirical question.

Second, the fact that populist citizens are substantively less likely to identify populism according to the rhetoric employed by politicians, suggests that they might still see populism under a negative light and are hence not be willing to classify as populist anti‐elite or people‐centric statements that they mostly agree with. On the other hand, this result may indicate that they simply do not think that such statements are populist, and hence hold different ideas about what populism really represents. With this in mind, we should then expect populist voters to be less likely to identify populist cues – simply because they are naturally inclined not to perceive them as problematic.

Conclusion

Investigating the largely unexplored territory of how citizens identify populist politicians, our article provides novel, insightful results. First, rhetoric, and populist rhetoric in particular, does significantly matter for such identification patterns, as all other characteristics of politicians are largely inconsequential. Second, respondents’ own populist attitudes are crucial in determining how they identify populist politicians and populist rhetoric. Likely drawing from their political preferences, and yet influenced by the negative, broad stigmatization of populism, populist citizens conceive people‐centric and anti‐elite political claims as weaker predictors of the populism of a politician compared to non‐populist respondents. More generally, indeed, populist citizens show much less variation in their classification of the four statements. On the other hand, also education matters, though to a lower extent, as highly educated respondents identify populist and non‐populist statements in a more accurate way compared to less educated citizens. Interestingly enough, all other characteristics of respondents, such as political ideology and political interest do not show relevant differences across the sub‐groups.

These findings generate interesting implications for the literature on populism and on political behaviour more broadly. To some extent, citizens construe populism as previous literature has suggested concerning populism's core features. For them, populism is essentially a rhetorical phenomenon and they do distinguish between anti‐elite, people‐centric statements and non‐populist political claims. However, a counterintuitive, insightful finding this article generates is that rhetoric appears to be the only factor that explains citizens’ perceptions of populism, hence casting doubts on the literature about the ideological dimension of populism, such as the works on the ‘populist hype’. Indeed, it may be the case that such hype characterizes academic and media perceptions and discussion on populism, rather than public opinions.

To be sure, this does not mean that they are less likely to be influenced by populism and populist rhetoric. Indeed, Bos and colleagues (Reference Bos, Van Der Brug and de Vreese2013) show that less educated and more cynical citizens are more prone to be persuaded by populist politicians’ rhetoric, and strong evidence exists that lower education is associated with greater support for populist parties (Cordero et al., Reference Cordero, Zagórski and Rama2022; Schmuck & Matthes, Reference Schmuck and Matthes2015). In line with this literature, indeed, we have shown that more educated respondents seem better able to distinguish populist from non‐populist rhetoric. Rather, this increased persuasiveness could stem precisely from the fact that they are less likely to perceive populism as such – much in the same way as less educated people seem less likely to identify disinformation at face value.

Next, regarding the characteristics of citizens, what emerges as crucial are respondents’ populist attitudes. Aside from education, the implication here is that the cognitive and ideological profile of respondents is largely inconsequential, a result that contrasts with previous literature's emphasis on the importance of ideology, and political trust to explain populist attitudes. If these factors may matter to explain patterns of voting behavior, they are not relevant for the public's interpretation of who is a populist. This implies that evidently populist politicians do not really need to rely on a strong populist rhetoric to be ‘recognized’ by populist voters.

Following on this point, our investigation has significant implications within and beyond academic research as well. First, a systematic investigation of how the public defines populism, and whom they label as a populist tells a story about how politicians could avoid, or possibly seek, a recognized status of populist. Second, the assessment of which citizens’ characteristics lead them to see a certain degree of populism in political statements and politicians can further advance our knowledge about which potential voters populist politicians do, and possibly should, target. Furthermore, the use of a conjoint experiment to analyse attitudes towards populism may establish a novel approach to the study of populism, as previous studies have employed experimental approaches mostly to assess the effect of populist rhetoric on voters (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Van Der Brug and de Vreese2013, Reference Bos, Schemer, Corbu, Hameleers, Andreadis, Schulz, Schmuck, Reinemann and Fawzi2020) or which factors increase voters’ support of populist parties (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Rooduijn and Schumacher2016; Spruyt et al., Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Droogenbroeck2016).

Finally, although the focus on one single country may reduce the potential of generalization of our results and considering that our experimental approach guarantees internal, not external, validity, the Italian case remains, in our opinion, a particularly relevant one to investigate. From a substantive standpoint, Italy is often cited as an example of a political system with populist actors across the political spectrum (also historically), as well as a rather challenging party system – which makes the prevalence of the phenomenon stand out. From a methodological standpoint, the widespread presence of populism in the Italian case makes, as we have argued, the country as a ‘hard‐case scenario’ for an investigation into how and why voters perceive populism in political elites – and most notably for the link between ideological cues and the identification of populism, for which the Italian case should yield conservative estimates.

This comes, however, with a substantial limitation, when it comes to translate the results into other contexts: the lower the endemicity of populism in a given country, the higher the chances that idiosyncratic elements of political actors come into play – for instance, their political alignment. In a country where all political factions can turn populist, the role of their ideology is not likely to be particularly relevant for the voters, but when populism becomes rare who goes populist likely matters. With this in mind, future studies should try to replicate our investigation in other countries, testing whether our results hold in different political contexts – and likely considering the moderation role of political ideology, either in substantive terms or in terms of extremity. Furthermore, exploiting the potential of manipulation in experimental research, especially using conjoint designs, scholars could test whether other characteristics of politicians and citizens influence the latter's attitudes towards populism and associated identification patterns.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the financial support by the MIUR Grant ‘Dipartimenti di Eccellenza 2018‐2022’.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

Dataset and replication files are available here: http://www.luigicurini.com/scientific‐publications.html