4.1 Is the Unmoved Mover a Final Cause, an Efficient Cause, or Both?

While Chapters 1 and 2 have focused on Proclus’ integration of the intellect as prime mover in his system of movers, the question still arises regarding the prime mover’s causality not just in his own philosophy but also in his exegesis of Aristotle. For, as is widely acknowledged, one of the perennial questions of Aristotelian scholarship concerns the type of causal relationship between the prime mover and the universe. It seems well-established in Physics 8 and Metaphysics 12 that the unmoved mover is ultimately responsible for the eternal motion of the universe. Yet, it remains obscure how it causes this motion and whether the two accounts are even compatible. This ambiguity is fundamentally due to the limited description – especially in the Physics – of the unmoved mover’s mode of operation, which has led to fierce debates among scholars. Just to give a brief overview, in recent scholarship Judson (Reference Judson, Gill and Lennox1994; Reference Judson2019) has maintained that the two accounts are coherent and that Aristotle’s unmoved mover is an efficient cause insofar as it is a final cause – that is, by being an object of desire to the heaven it can be regarded as an efficient cause of the heaven’s desire and, thus, remotely of its motion. This view has been rejected by Gourinat (Reference Gourinat and Bonelli2012), who – like Manuwald (Reference Manuwald1989) before him – maintains that the unmoved mover is in both works only a final cause. In contrast to this position, Berti (Reference Berti2007) claims that the unmoved mover is solely an efficient cause of the heaven’s motion. Most importantly, the vast majority of scholars who assume the efficient causality of the prime mover only regard it as an efficient cause of motion, not of being.

The origins of the dispute regarding the causality of the Aristotelian prime mover can be traced back to antiquity. Particularly among late Neoplatonists the problem becomes a central concern in Aristotelian exegesis, arguably due to the need to harmonise Aristotle’s intellect with Plato’s demiurge and to account for the cause of the generation of the cosmos (Simpl. In Phys. 1360.24–31). Crucially, the issue is a major source of contention between Neoplatonists who believe there is an essential agreement between Plato and Aristotle and those who do not endorse this view. Unlike many scholars nowadays, the Neoplatonists ascribe to Aristotle a unitary and systematic theory of the unmoved mover, found not only in Physics 8 and Metaphysics 12 but also in the De caelo.Footnote 2 The most influential interpretation, especially in consideration of its medieval reception, is the one proposed by Ammonius and his pupil Simplicius. Both argue that Aristotle’s unmoved mover is not just a final cause but also an efficient cause of the cosmos’ motion and being – that is, it generates the cosmos. Especially the latter is in sharp contrast to the opinion of most modern scholars. What is precisely meant by this is obscured by the fact that Simplicius dedicates little space to the question and mostly offers us a few testimonies from Ammonius’ – now lost – book on this issue which was central to this debate.

Unlike Ammonius and Simplicius, Proclus criticises Aristotle’s unmoved mover for being exclusively a final cause and not an efficient cause of being as well:

And indeed the inspired Aristotle seems to me for this reason, in preserving his first principle free of multiplicity, to make it only the final cause of all things, lest in granting it to produce (ποιοῦν) all things, he should be forced to grant it activity towards what follows upon it (τὴν πρὸς τὰ μετ’ αὐτὸ ἐνέργειαν); for if it is only the final cause, then everything exercises activity towards it, but it towards nothing.

Thus, for Proclus, Aristotle’s intellect is ‘in no way productive’ (In Tim. [1.390.6]: ποιητικὸς δὲ μηδαμῶς). As encountered previously, this attitude is in line with his non-harmonist and more critical approach towards Aristotle. As one of the earliest extensive engagements with the causality of the unmoved mover, Proclus’ critique plays a pivotal role and prefigures many ancient and medieval discussions on this issue. Indeed, as I show, some of the arguments employed by Ammonius and Simplicius in defending the unmoved mover’s efficient causality are found in Proclus in a more elaborate way. The major difference is that Proclus, unlike Ammonius and Simplicius, does not ascribe the results of these arguments to Aristotle. As I emphasise, Proclus’ interpretation is closer to modern views on Aristotle and, indeed, should be preferred to Ammonius’/Simplicius’ reading as it is closer to the meaning of Aristotle’s text. I will also demonstrate that the way these authors interpret Aristotle is grounded in their general views on Aristotle’s relationship with Plato. For this, I offer the first in-depth comparison of these authors on such a challenging issue.

My objective in this chapter is threefold: (1) to set out Proclus’ criticism of Aristotle’s intellect through a detailed analysis of his objections; (2) to compare it with Ammonius’ and Simplicius’ position by focusing on their different strategies in reading Aristotle; and (3) to present Proclus’ own reasons for making the demiurge a final cause and efficient cause of being, which are connected to his critique. The chapter is split into four sections. I first set out briefly Aristotle’s own view on the causality of the intellect (4.2), before I move on to Proclus’ critique (4.3). I elucidate how this specific criticism is part of a general attack on Aristotelian metaphysics which Proclus regards as deficient. In defending his view of the demiurge’s causality, Proclus chides Aristotle numerous times for rejecting the efficient causality of the intellect. I reconstruct two central objections in which Proclus demonstrates that Aristotle’s own principles would have committed him to accept the intellect as efficient cause of being. Aristotle himself, however, did not draw this conclusion, as Proclus makes clear. Then (4.4) I set out the views of Ammonius and Simplicius, who regard Aristotle’s intellect as final cause as well as efficient cause of being. I show that they partly use the same arguments as Proclus with the crucial difference that these Neoplatonists ascribe them completely to Aristotle. As I demonstrate, their strategy of reading Aristotle differs from Proclus’ more critical position because of their commitment to harmonising Aristotle with Plato on fundamental issues which Proclus does not share. This emphasises that Aristotle’s authority is not the same in Proclus as in Ammonius and Simplicius. By reconstructing this late antique debate I render these different approaches to Aristotle among the Neoplatonists more palpable. Finally, (4.5) I discuss Proclus’ positive views on the subject matter. As I show, he backs up his view of the demiurge’s causality not only by his general metaphysical theory of causation found in the Elements of Theology but also by an exegesis of Plato’s Timaeus. The former offers an attractive theoretical solution to why we should assume that the intellect is both a final and an efficient cause.

4.2 Aristotle

I briefly outline in the following my own interpretation of Aristotle’s views. I do not have space to do justice to the complexity of this question nor to the wide variety of interpretations. It remains, nevertheless, necessary to introduce the discussion of the Neoplatonist positions with a treatment of Aristotle as it inevitably influences my analysis of them. Part of my intention is to show that the unmoved mover’s causality is just as controversial nowadays as it was in late antiquity. As it emerges, various points of contention are very similar and centred around the same passages. Since the prime mover’s final causality has rarely been called into question, the focus is on the prime mover’s efficient causality, which has been negated by Aristotle’s commentators since antiquity. The meaning of efficient causality in this context is often obscure in modern scholarship. The majority of scholars understand it as a cause of motion and not of being like some ancient commentators. Yet, whether this causation of motion implies a transmission of force or energy from the unmoved mover to the cosmos is a matter of debate.

Oddly enough for a treatise meant to explain the origin of the cosmos’ motion, Aristotle is surprisingly taciturn in Physics 8 when it comes to how exactly the unmoved mover brings it about.Footnote 3 Characterisations of the unmoved mover as either final or efficient cause seem vague. This issue becomes even more pressing if we consider Aristotle’s effort in Physics 2 to set out a nuanced theory of causality (which, however, applies primarily to natural substances).Footnote 4 Due to this perceived ambiguity, scholars like Manuwald (Reference Manuwald1989) and Gourinat (Reference Gourinat and Bonelli2012) have abandoned the identification of the unmoved mover with efficient causality. Yet, there still remain numerous scholars who take this very position (as we will see in the following sections). The picture differs in Metaphysics 12 where the prime mover is described as an object of desire and thought as well as something for the sake of which (οὗ ἕνεκα)Footnote 5: it moves as a beloved (12.7.1072b3: κινεῖ δὴ ὡς ἐρώμενον). These descriptions have led to the widespread view that the prime mover there is a final cause. How then are we supposed to square this position with the view offered in Physics 8?

There are strong reasons for assuming that both accounts of the unmoved mover in Physics 8 and Metaphysics 12 are essentially in agreement and complement each other, although the contexts and approaches clearly differ.Footnote 6 The argument for the unmoved mover in Metaphysics 12 is highly dependent on Physics 8 and, in fact, to a large degree unintelligible without the latter.Footnote 7 It is thus incorrect to claim that the ‘conceptions of the First Cause developed more or less independently in the Physics and Metaphysics’ (Wardy Reference Wardy1990: 123). Moreover, De motu animalium (1.698a7–11, 6.700b7–9) refers indiscriminately to both works for the underlying theory of motion without a hint of a substantial difference between them.Footnote 8 In the following, I consider three arguments for the efficient causality of the unmoved mover. The first evidence is the way the argument is sustained in Physics 8 (4.2.1). As further proof, I examine the infinite power argument of Physics 8.10 which strongly suggests an efficient causality of the unmoved mover and is, most importantly, also encountered in Metaphysics 12 (4.2.2) where we find further evidence for this type of causality (4.2.3).

Before I examine these two works, I would like to consider the claim that the prime mover cannot be both an efficient and final cause on general grounds. The widespread view that whatever is a final cause cannot be an efficient cause is based on an interpretation of GC 1.7.324b13–15:Footnote 9

Ἔστι δὲ τὸ ποιητικὸν αἴτιον ὡς ὅθεν ἡ ἀρχὴ τῆς κινήσεως. Τὸ δ’ οὗ ἕνεκα οὐ ποιητικόν. Διὸ ἡ ὑγίεια οὐ ποιητικόν, εἰ μὴ κατὰ μεταφοράν.

The thing which is efficient is a cause in the sense of that from which motion originates. The final cause is not efficient. Therefore, health is not efficient, except metaphorically.

Proponents of this interpretation are, for instance, Manuwald (Reference Manuwald1989: 16) and Gourinat (Reference Gourinat and Bonelli2012: 176), who regard this as evidence that the unmoved mover can be only a final cause.Footnote 10 In contrast to these scholars, Sedley (Reference Sedley, Frede and Charles2000: 345) and Judson (Reference Judson2019: 185–6) maintain that the passage does not apply to the unmoved mover. This is either because Metaphysics 12 simply goes beyond the doctrine of De generatione et corruptioneFootnote 11 or because Aristotle refers in the De generatione et corruptione passage to ‘those cases of being active which involve interaction, and by the same token he is thinking of final causes such as health which are clearly not active’ (Judson Reference Judson2019: 185).

While I sympathise with Sedley’s and Judson’s conclusion, that is, that the unmoved mover can have both types of causality, I do not think they offer strong arguments for rejecting the prima facie reading of 324b13–15. Rather, I take it that the point of the passage is to emphasise that being poiētikon (ποιητικόν) automatically entails being an origin of motion, whereas a final cause – since it is not strictly speaking producing something – does not have to be an origin of motion. According to GC 1.6.322b22–4, to be productive stricto sensu (κυρίως) implies a mutual contact between mover and moved object. This only applies to moved movers but not to unmoved movers who can only have non-reciprocal contact with the moved objects. Nevertheless, in an extended senseFootnote 12 a final cause can be productive and thus an origin of motion. A good example for this is the soul which Aristotle characterises as final, efficient and formal cause (DA 2.4.415b8–12). Additionally, in GC 2.9.335a30–2 he admits that there is an efficient cause for eternal beings, that is, the heaven and stars.

4.2.1 The Argument of Physics 8 Requires an Efficient Cause

The line of argumentation developed in Physics 8 generally suggests an investigation into the efficient cause of the cosmos’ motion since Aristotle is looking for the origin of motion and conducts his discussion in efficient terms. The view has been proposed by Broadie and Judson as an evident fact without much further investigation.Footnote 13 Aristotle himself refers in De generatione et corruptione (1.3.318a1–6) to the prime mover of the Physics as an efficient cause. Internal confirmation from Physics 8 for this view can be found in chapter 4. There Aristotle proves that everything in motion is moved by something (256a2–3: ἅπαντα ἂν τὰ κινούμενα ὑπό τινος κινοῖτο) – a phrase clearly indicating that efficient causality is discussed here, that is, the moving cause. More specifically, the preposition hupo (ὑπό) with the genitive indicates agency in this context.Footnote 14 At no point in the argument of chapter 4 does Aristotle distinguish between the causation of the unmoved mover and moved movers. Instead, he talks about causes of motion in general. However, elsewhere he entertains the possibility of only one-sided or non-reciprocal contact in the case of unmoved movers, which would imply that they bring about motion differently from moved movers. For instance, at 8.5 258a18–21 the unmoved part in a self-mover is presented as either being in reciprocal contact or only touching the moved thing while not being itself touched by it.Footnote 15 This presumably has to do with the unmoved mover’s immateriality. Even if the prime mover causes the cosmos’ motion either without any contact or by non-reciprocal contact, it still acts as an efficient cause of the motion and is, as such, treated together with other moving causes. There is no reason to assume that causing motion without contact or, at least, a non-reciprocal one excludes being an efficient cause. More puzzling is rather Aristotle’s view that motion can be caused with non-reciprocal contact in the first place. This is due to the non-/super-natural origin of motion in the cosmos.

However, Gourinat (Reference Gourinat and Bonelli2012) has recently rejected this interpretation: while a great deal of the argumentation in Physics 8 seems to be looking for an efficient cause of motion, he argues that the introduction of an unmoved mover changes the type of causation under discussion.Footnote 16 According to Gourinat, when Aristotle posits an unmoved mover – either as part of a self-moving animal or as the prime mover itself – he is no longer investigating the efficient cause of motion. He bases his claim on the consideration that unmoved movers cause motion differently than moved movers, which is grounded in a short passage from Physics 7.2:

Τὸ δὲ πρῶτον κινοῦν, μὴ ὡς τὸ οὗ ἕνεκεν, ἀλλ’ ὅθεν ἡ ἀρχὴ τῆς κινήσεως, ἅμα τῷ κινουμένῳ ἐστί (λέγω δὲ τὸ ἅμα, ὅτι οὐδέν ἐστιν αὐτῶν μεταξύ)· τοῦτο γὰρ κοινὸν ἐπὶ παντὸς κινουμένου καὶ κινοῦντός ἐστιν.

The prime mover [of a thing] – which does not supply that for the sake of which but the source of the motion – is always together with the moved object (by ‘together’ I mean that there is nothing between them). This is common to everything moved and moving.

Here Aristotle distinguishes between a proximate prime mover, which is moved, and the ultimate prime mover, which is unmoved.Footnote 17 Gourinat takes this to be a general distinction between the workings of moved movers and unmoved movers. The former act as efficient causes by transmitting motion via reciprocal contact. However, as outlined, the contact between an unmoved mover and moved thing is only one-sided, that is, the unmoved mover touches the moved thing but is not touched by it in turn. This heterogeneity between unmoved mover and moved thing – to be contrasted with the homogeneity between moved mover and moved thing – indicates to Gourinat a ‘causal heterogeneity’. He thus concludes that, unlike moved movers, unmoved movers do not cause motion as efficient causes but instead only as final causes.Footnote 18

I do not find this view convincing since Gourinat works with a very narrow understanding of efficient cause, which seems to imply that a mover is only an efficient cause if a contact on both sides of mover and moved occurs.Footnote 19 This is due to a tendentious reading of Physics 7.2 whereby moved movers are the only movers identified with this type of causation. Yet, in this passage Aristotle does not exclude that the prime unmoved mover is an efficient cause but only that the prime moved mover is a final cause. Aristotle’s whole point is to distinguish moved movers from unmoved movers by pointing out the former’s lack of final causality. Consequently, this does not entail that the prime unmoved mover is not an efficient cause.Footnote 20 More generally, Physics 8 should not be read by automatically importing doctrines from book 7 – whose standing in the Physics is questionable anyway – as book 8 offers a new start in the discussion. Rather, one has to consider his numerous expressions throughout book 8 which indicate that efficient causality is under discussion. A good example for this is found in the next section.

4.2.2 The Unmoved Mover Transmits Power (Physics 8.10 and Metaphysics 12.7)

The so-called infinite power argument in Physics 8.10 implies that the prime mover transmits power (dunamis) to the thing it moves and is thereby an efficient cause. This argument, which is taken up again in Metaphysics 12 has caused great puzzlement especially among scholars who regard the unmoved mover exclusively as a final cause.Footnote 21 As one of the most (in)famous arguments for the causal efficiency of the unmoved mover it has proven to be immensely influential (but also controversial) in late antiquity and the Middle Ages.Footnote 22 Aristotle sets out to prove through various reductiones ad impossibile the indivisibility of the unmoved mover via its lack of a magnitude:

(1) No finite thing can cause motion for an infinite time. (266a12–23)

(2) No infinite power can belong to a finite magnitude. (266a24–266b6)

(3) No finite power can belong to an infinite magnitude. (266b6–24)

These reductiones lead him to the following conclusion regarding the unmoved mover:

εἰ γὰρ μέγεθος ἔχει, ἀνάγκη ἤτοι πεπερασμένον αὐτὸ εἶναι ἢ ἄπειρον. ἄπειρον μὲν οὖν ὅτι οὐκ ἐνδέχεται μέγεθος εἶναι, δέδεικται πρότερον ἐν τοῖς φυσικοῖς· ὅτι δὲ τὸ πεπερασμένον ἀδύνατον ἔχειν δύναμιν ἄπειρον, καὶ ὅτι ἀδύνατον ὑπὸ πεπερασμένου κινεῖσθαί τι ἄπειρον χρόνον, δέδεικται νῦν. τὸ δέ γε πρῶτον κινοῦν ἀΐδιον κινεῖ κίνησιν καὶ ἄπειρον χρόνον. φανερὸν τοίνυν ὅτι ἀδιαίρετόν ἐστι καὶ ἀμερὲς καὶ οὐδὲν ἔχον μέγεθος.

For if it has magnitude, the magnitude must be either finite or infinite. That there cannot be an infinite magnitude has already been proved in the Physics. That a finite magnitude cannot have infinite power, and that something cannot be moved for an infinite time by a finite magnitude, has just been proved. But the first mover causes everlasting motion for an infinite time. Plainly, then, it is indivisible and without parts, and it has no magnitude.

Aristotle deduces that since the prime mover can be neither a finite nor an infinite magnitude it must be without magnitude. He does not attribute infinite power explicitly to the unmoved mover. However, one reason for excluding that the unmoved mover is a finite magnitude is the impossibility of infinite power residing in a finite magnitude. This in turn implies that the unmoved mover must have infinite power and therefore cannot be a finite magnitude. Otherwise, it is impossible to explain why infinite power is even a concern here and part of his argument. Similarly, Aristotle shows that a finite magnitude cannot move something infinitely. Again, here the implication is that the unmoved mover must move something for an infinite time and therefore cannot be a finite magnitude. Thus, both arguments contain attributes of the unmoved mover (i.e., infinite power and capacity to move something for an infinite time) which cannot belong to a finite magnitude. In fact, both are connected: the capacity to move something for an infinite time implies having an infinite power and vice versa.

The same attribution is found in Metaphysics 12.7 whose discussion is doubtless referring back to Physics 8.10:Footnote 23

δέδεικται δὲ καὶ ὅτι μέγεθος οὐδὲν ἔχειν ἐνδέχεται ταύτην τὴν οὐσίαν ἀλλ’ ἀμερὴς καὶ ἀδιαίρετός ἐστιν (κινεῖ γὰρ τὸν ἄπειρον χρόνον, οὐδὲν δ’ ἔχει δύναμιν ἄπειρον πεπερασμένον· ἐπεὶ δὲ πᾶν μέγεθος ἢ ἄπειρον ἢ πεπερασμένον, πεπερασμένον μὲν διὰ τοῦτο οὐκ ἂν ἔχοι μέγεθος, ἄπειρον δ’ ὅτι ὅλως οὐκ ἔστιν οὐδὲν ἄπειρον μέγεθος)·

And it has also been proved that this same substance can have no magnitude, but is partless and indivisible. For it causes motion for an infinite time, and nothing finite can have an infinite power. Now every magnitude is either infinite or finite; but it could not have a finite magnitude for this reason, nor an infinite one because there is no infinite magnitude of any sort.

Here too Aristotle connects moving something for an infinite time with having an infinite power to do so. The argument is used, as in Physics 8, for the purpose of demonstrating the unmoved mover’s lack of spatial extension. Just like there, it seems impossible for the same reasons not to read the passage as ascribing infinite power to the unmoved mover.

Unfortunately, Aristotle fails to explain in both passages how the prime mover uses this power to cause the cosmos’ motion. The discussion in Physics 8.10 seems to make clear that the power is somehow transmitted to an object and allows it to move in a broad sense: Aristotle uses not only the examples of heating, sweetening and throwing but causing motion in general (266a28: ὅλως κινοῦσα). In all of these cases the power or energy of the moving thing is transmitted to the moved object. However, Judson (Reference Judson, Gill and Lennox1994: 165–6) and Laks (Reference Laks, Frede and Charles2000: 241) point out that the unmoved mover is simply not the type of efficient cause that transmits its own motion or energy like, for example, a human wielding a stick.Footnote 25 This is because the unmoved mover is not spatially extended and moves the heaven by instilling desire through its own goodness. As such, the modus operandi of an efficient cause like the unmoved mover differs fundamentally from other efficient causes. While this leads Judson to conclude that the infinite power argument is simply incompatible with any account of the unmoved mover’s causation in the Physics and the Metaphysics, Laks only points out that the transmission of δύναμις must have a metaphorical sense here.Footnote 26 Both of these explanations are far from satisfying.Footnote 27 As I show below, the Neoplatonists offer an interesting solution to harmonising the infinite power argument with the prime mover’s final causality.

Since the infinite power argument suggests that the unmoved mover is somehow an efficient cause and not just a final cause, it is especially problematic for interpretations of the unmoved mover as an exclusively final cause, such as Gourinat’s (Reference Gourinat and Bonelli2012), who offers no explanation of how his interpretation relates to this argument.Footnote 28 Yet, it also seems hardly compatible with current accounts of the unmoved mover’s efficient causality, as proposed by Broadie, Berti or Judson. Broadie (Reference 222Broadie1993), for instance, ignores it altogether, as do also Ross (Reference Ross1924: II, 382) and Fazzo (Reference Fazzo2014: 341–2) in their comments on Metaphysics 12.7.Footnote 29 Additionally, the issue is aggravated by the argument’s presence in Physics 8 and Metaphysics 12.7 so that unlike, for instance, the much-disliked passage on the location of the unmoved mover – which only occurs in Physics 8 – this discussion cannot be simply explained away by assuming a development. In this way, both the overall structure of the argument in Physics 8 as well as the discussion of infinite power suggest that the unmoved mover is here conceived as an efficient cause. For Metaphysics 12, however, there is further proof that this type of causality should be attributed to the unmoved mover.

4.2.3 The Unmoved Mover as kinētikon and/or poiētikon (Metaphysics 12.6 and 10)

A crucial passage from Metaphysics 12.6 lends further support for this view:

Ἀλλὰ μὴν εἰ ἔστι κινητικὸν ἢ ποιητικόν, μὴ ἐνεργοῦν δέ τι, οὐκ ἔσται κίνησις· ἐνδέχεται γὰρ τὸ δύναμιν ἔχον μὴ ἐνεργεῖν. οὐθὲν ἄρα ὄφελος οὐδ’ ἐὰν οὐσίας ποιήσωμεν ἀϊδίους, ὥσπερ οἱ τὰ εἴδη, εἰ μή τις δυναμένη ἐνέσται ἀρχὴ μεταβάλλειν· οὐ τοίνυν οὐδ’ αὕτη ἱκανή, οὐδ’ ἄλλη οὐσία παρὰ τὰ εἴδη· εἰ γὰρ μὴ ἐνεργήσει, οὐκ ἔσται κίνησις. ἔτι οὐδ’ εἰ ἐνεργήσει, ἡ δ’ οὐσία αὐτῆς δύναμις· οὐ γὰρ ἔσται κίνησις ἀΐδιος· ἐνδέχεται γὰρ τὸ δυνάμει ὂν μὴ εἶναι. δεῖ ἄρα εἶναι ἀρχὴν τοιαύτην ἧς ἡ οὐσία ἐνέργεια.

Yet if there is something which can cause motion or act upon things, but is not active in some way, there will be no motion; for that which has a potentiality can fail to be active. Nor will it help, then, even if we posit substances which are eternal – as do those who posit the forms – unless there is some principle in them which is able to cause motion. Yet not even this will be sufficient, nor will another substance besides the forms; for unless it is active there will be no motion. Again, it will not be sufficient if it is active but its substance is potentiality; for there will not be eternal motion, since that which is potentially can fail to be. There must, therefore, be a principle of this sort, whose substance is activity.

Aristotle argues here that it is not sufficient for the unmoved mover to be a moving (kinētikon) or producing (poiētikon) cause in potentiality. Rather, it must be so in actuality in order to cause the eternal motion of the cosmos. At any rate, it is clear that the unmoved mover must be an efficient cause, as the expressions κινητικόν and ποιητικόν indicate. This is backed up by his reference to the forms in the next line: insofar as these do not even have potentially a source of motion (δυναμένη … ἀρχὴ μεταβάλλειν), they cannot account for the eternal motion. What Aristotle’s theory requires is thus clearly an efficient cause in actuality, that is, one that has actual infinite power.

The formulations κινητικόν and ποιητικόν recur in chapter 10 but this time without the disjunctive:

ἀλλὰ μὴν οὐδέν γ’ ἔσται τῶν ἐναντίων ὅπερ καὶ ποιητικὸν καὶ κινητικόν; ἐνδέχοιτο γὰρ ἂν μὴ εἶναι. ἀλλὰ μὴν ὕστερόν γε τὸ ποιεῖν δυνάμεως. οὐκ ἄρα ἀΐδια τὰ ὄντα. ἀλλ’ ἔστιν· ἀναιρετέον ἄρα τούτων τι. τοῦτο δ’ εἴρηται πῶς.

In fact, not one of the opposites will also be able to act upon things and able to cause motion; for it would be able not to be. In fact, acting upon things is posterior to potentiality. Therefore, the things which are will not be eternal. But they are. Therefore, one of these must be eliminated: it has been said how this is to be done.

Sedley (Reference Sedley, Frede and Charles2000: 344–6) and Judson (Reference Judson2019: 361–2) rightly see this passage as connected to chapter 6. Unlike there, Aristotle here refers implicitly to the unmoved mover as ποιητικὸν καὶ κινητικόν and not κινητικὸν ἢ ποιητικόν. While it is unclear whether there is a real difference between these formulations, I assume that the conjunction καί at 1075b31 makes clear that, in fact, the ἤ at 1071b12 presents an equivalence, not an alternative.Footnote 30 That is, the unmoved mover can be described correctly by both terms, κινητικόν and ποιητικόν. The proximity of the two terms is also indicated by a passage from De generatione et corruptione: ἐν ἅπασιν εἰώθαμεν τοῦτο λέγειν τὸ ποιοῦν, ὁμοίως ἔν τε τοῖς φύσει καὶ ἐν τοῖς ἀπὸ τέχνης, ὃ ἂν ᾖ κινητικόν (2.9.335b27–8). Thus, both passages strongly suggest that the unmoved mover is an efficient, that is, moving and producing, cause.

4.2.4 Conclusion

In conclusion, there is significant evidence in Physics 8 and Metaphysics 12 for understanding the prime mover not just as a final cause but also as an efficient one. The general argument and especially the infinite power argument of Physics 8 present the unmoved mover as an efficient cause of the cosmos’ eternal motion – even though the details of the causation remain obscure. This account is then further developed (or at least elaborated) in Metaphysics 12. It thus seems fallacious to view the prime mover as solely an efficient cause (Berti Reference Berti2007) or solely a final cause (Gourinat Reference Gourinat and Bonelli2012).

Yet, the lack of an explicit discussion of the prime mover’s efficient causality, as well as the ambiguity of some of the passages discussed, posed a difficulty for future exegetes. This left Aristotle’s texts susceptible to differing interpretations, as the survey of different positions in scholarship showed. For instance, it remains questionable whether the prime mover is (1) a final cause by being an efficient cause or (2) an efficient cause by being a final cause. Frede (Reference Frede, Frede and Charles2000: 43–7) and Menn (Reference Menn and Shields2012b: 447) opt for (1), while Judson (Reference Judson, Gill and Lennox1994: 164–7) and (Reference Judson2019: 185–6) goes for (2).Footnote 31 As I show, the Neoplatonists who believe that the prime mover has both types of causality believe that one type of cause implies the other and vice versa so that there is no subordination of one to the other. A major issue remains of precisely how we are to understand efficient causality in this context. In the next two sections, I analyse two different reactions to this issue.

4.3 Proclus’ Critique of Aristotle’s Intellect

In a number of passages from his commentaries on the Timaeus and the Parmenides, Proclus criticises Aristotle’s intellect as being only a final cause and lacking efficient/productive causality.Footnote 32 The latter is understood not just as causation of motion, as in most modern scholarship on Aristotle, but also of being. This is a very serious objection given Proclus’ Platonist conception of intellect as creative demiurge: ‘those, then, who make intellect a final but not a demiurgic cause possess only half the truth’ (In Parm. 4.842.20–2). Consequently, Aristotle’s prime mover is ἄγονος (842.26). The fundamentals of his critique are found in Proclus’ teacher Syrianus (see Section 4.3.3.4). However, it is in Proclus that we get the most extensive discussion.

In this section, I argue that

(1) Proclus’ critique is part of a more fundamental disagreement with Aristotle’s metaphysics.

(2) Consequently, Proclus maintains that Aristotle and Plato have different understandings of efficient causality and that Aristotle’s prime mover is not an efficient cause in the Platonic sense.

(3) Yet, Proclus believes that ultimately Aristotle’s arguments for establishing the existence of the prime mover commit him to conclusions more in line with Platonist doctrine. That is, if Aristotle had taken the premises of his arguments seriously, he would have been forced to conclude that the intellect is a cause of the cosmos’ being and not just of its motion.

(4) However, unlike Ammonius and Simplicius, Proclus does not believe that Aristotle actually drew these conclusions. Instead, Aristotle has compromised his metaphysics through a deficient understanding of the intellect’s causality. In this way, he is in disagreement with Plato’s concept of the demiurge.

Let us first consider Proclus’ general misgivings about Aristotelian metaphysics.

4.3.1 The Fundamental Deficiency of Aristotelian Metaphysics

In the following, I argue that, according to Proclus, Aristotle’s misunderstanding of the intellect’s causality is part of a general deficiency in Aristotle’s metaphysics. This, Proclus upholds, is caused by his confusion of the nature and the identity of the highest principle: Aristotle denies the existence of the One and instead mistakenly posits the intellect as first principle. Due to the parsimony of Proclus’ remarks,Footnote 33 this issue has not been appreciated enough in scholarship: rather, both Steel (Reference Steel, Pépin and Saffrey1987a) and d’Hoine (Reference d’Hoine2008) have emphasised that Proclus sees an interdependence between denying the intellect’s efficient causality and denying the existence of the paradigm.Footnote 34 Additionally, Steel suggests that for Proclus Aristotle’s rejection of the forms has ‘the most disastrous consequence’ (225: ‘la consequence la plus désastreuse’) of his inability to posit a higher principle than intellect. While this might be the case in the passage Steel focuses on (In Parm. 4.972.29–973.12; cf. In Tim. 2.91.4 [1.266.30]), I show that elsewhere Proclus presents the causal relationship differently: by denying the existence of the One and instead attributing some of its characteristics to the intellect, Aristotle rejects the intellect’s efficient causality.Footnote 35 In this way, Aristotle’s other metaphysical shortcomings follow from his rejection of the Platonic One and not vice versa, as in some of the texts on which Steel and d’Hoine base their analysis.

Aristotle’s repudiation of the One emerges more clearly from a passage in the commentary on the Timaeus where Proclus compares Aristotle with Plato and emphasises their differences:Footnote 36

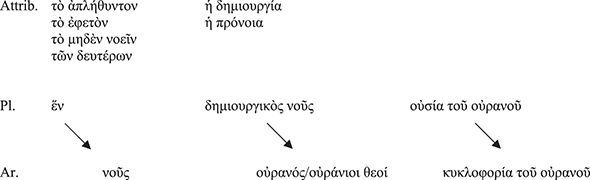

(1) ὅσα γὰρ τῷ ἑνὶ Πλάτων, ταῦτα τῷ νῷ περιτίθησι, τὸ ἀπλήθυντον, τὸ ἐφετὸν, τὸ μηδὲν νοεῖν τῶν δευτέρων· (2) ὅσα δὲ τῷ δημιουργικῷ νῷ ὁ Πλάτων, ταῦτα τῷ οὐρανῷ καὶ τοῖς οὐρανίοις θεοῖς Ἀριστοτέλης· παρὰ [τούτων] γὰρ εἶναι τὴν δημιουργίαν καὶ τὴν πρόνοιαν· καὶ (3) ὅσα τῇ οὐσίᾳ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ ὁ Πλάτων, ταῦθ’ οὗτος τῇ κυκλοφορίᾳ, τῶν μὲν θεολογικῶν ἀρχῶν ἀφιστάμενος, τοῖς δὲ φυσικοῖς λόγοις πέρα τοῦ δέοντος ἐνδιατρίβων.

(1) What Plato attributes to the One, he ascribes to the intellect, that is, non-multiplicity, being the object of desire and not having any of the secondary things as object of its thought; and (2) what Plato attributes to the demiurgic intellect, Aristotle ascribes to the heaven and the heavenly gods, for it is from them that creativity and providence take place; and (3) what Plato attributes to the essential nature of the heaven, this man ascribes to its circular movement, placing theological principles at a distance and spending more time on physical argumentation than he should.

Proclus describes here Aristotle’s tendency to ‘downgrade’ (metaphysical) attributes: (1) the characteristics of Plato’s One match those of Aristotle’s intellect, (2) those of Plato’s demiurgic intellect those of Aristotle’s heaven/heavenly bodies, and (3) those of Plato’s heaven those of Aristotle’s heavenly circular motion. This effectively leads to a misalignment of Plato’s and Aristotle’s principles (Figure 4.1).Footnote 37

The reason for that is said to be Aristotle’s distance from theological principles (τῶν μὲν θεολογικῶν ἀρχῶν ἀφιστάμενος) and undue focus on physical arguments (τοῖς δὲ φυσικοῖς λόγοις). Aristotle thus focused in his investigations too much on physical explanations instead of considering metaphysical causes. According to Proclus, this procedure led to his fallacious views and must be contrasted with Plato’s more adequate, theological approach to physics (In Tim. 1.3.13–4.14 [1.2.29–3.19], 1.302.7–9 [204.8–10], 2.32.6 [227.2–3]).

A few further remarks on (1) and (2) are necessary here. (1) is especially significant for Proclus’ interpretation of Aristotelian metaphysics, as it illuminates that, according to Proclus, the intellect is the highest principle in Aristotle: καὶ ὅ γε Ἀριστοτέλης – τοῦτο [sc. ὁ νοῦς ὁ ἐγκόσμιος] γὰρ ἀπεφήνατο εἶναι τὸ πρῶτον (In Tim. 2.147.4–5 [1.305.20–2]).Footnote 38 This is again emphasised in a rarely cited passage from the commentary on the Parmenides where Proclus points out Plato’s superiority in positing the One as first principle:

These doctrines are normally propounded by the majority of [Platonic] commentators (ἐξηγητῶν) about the One, and considering it the first principle, they say that it is not body, as the Stoics maintained, nor incorporeal soul, as Anaxagoras claimed, nor unmoved intellect (νοῦν ἀκίνητον), as Aristotle said later; by this, they claim, the philosophy of Plato differs from the others, in that it rises up to the cause above intellect (ὑπὲρ νοῦν αἴτιον ἀναδραμοῦσαν).

In the Platonic Theology, he also emphasises Plato’s uniqueness in this regard (1.3) and calls Aristotle’s view a Peripatetikē kainotomia (PT 2.4.31.21–2: Περιπατητικὴ καινοτομία), whereby the latter term negatively means a ‘departure from established (i.e., Platonico-religious) tradition’ or simply a ‘modernism’.Footnote 39 For Aristotle theology not only stops at the level of intellect but in fact coincides with its study (PT 1.3.12.23–13.5, esp. 13.4–5: εἰς δὲ ταὐτὸν ἄγουσι θεολογίαν δήπου καὶ τὴν περὶ τῆς νοερᾶς οὐσίας ἐξήγησιν). In the eyes of Proclus, Aristotle thus commits a grave mistake since the first principle is supposed to be the One/Good which transcends being and intellect altogether. The seriousness of this objection should not be downplayed, as for instance Baltes does.Footnote 40 Proclus’ interpretation of Aristotle’s highest principle mirrors Plotinus’Footnote 41 and Syrianus’ position,Footnote 42 both of which probably influenced him. At the same time his position must be contrasted with Ammonius’ and Simplicius’ view according to which Aristotle recognises the transcendent One.Footnote 43

Yet, most interestingly, Proclus claims that Aristotle does not simply reject the One but rather transfers some of its characteristics to the intellect. Accordingly, Aristotle’s intellect is similar to Plato’s One insofar as it is (i) non-multiplied, (ii) desired and (iii) does not think about lower beings. Proclus implies that these three characteristics should be attributed correctly to the One and not to the intellect. Rightly understood the intellect is not (i) non-multiplied but possesses multiplicity since its thinking involves at a minimal level a subject that thinks and an object that is thought.Footnote 44 Instead, (i) must be attributed to the One who is absolute unity.Footnote 45 Proclus’ objection to (iii) implies that Aristotle wrongly conceived the intellect’s thinking as exclusively self-centred and unconcerned with essences (or any other characteristics) of other beings. This brings Proclus’ reading close to many modern interpreters such as Ross (Reference Ross1924: I, cxli–iii), Guthrie (Reference Guthrie1981: 261–2) and Brunschwig (Reference Brunschwig2000).Footnote 46 Additionally, this objection fits well to Proclus’ observation that Aristotle’s intellect has no activity towards other beings (In Parm. 7.1169.4–9). Proclus believes (iii) must be denied of the intellect and instead applied to the One since the intellect has knowledge of lower beings and is concerned with them due to its providential nature. Indeed, as he argues at In Parm. 3.790.12–791.10 and 4. 964.16–25, if intellect has self-knowledge, as Aristotle holds, it knows itself as a cause, which implies knowing of what it is a cause. What about (ii)? Proclus, of course, holds fast to the idea that the intellect is epheton (ἐφετόν) – he even goes so far to say that it is desired by all beings (ET §34.38.3; discussed in Section 4.5.2). However, what he means here is that the intellect should not be seen as the ultimate object of desire like in Aristotle. This place should be reserved to the One or absolute Good, as he clarifies in In Tim. 1.4.1–2 [1.3.6], ET §8.8.31–2 and PT 2.9.59.13–16. Perhaps, this is why Proclus uses here the term with an article, that is, τὸ ἐφετόν (just as in τὸ ἀπλήθυντον and τὸ μηδὲν νοεῖν τῶν δευτέρων): the intellect clearly is an ἐφετόν but not the ἐφετόν.Footnote 47 Ultimately, this downgrading of attributes also makes it difficult to compare metaphysical principles, as the table reveals: Aristotle’s intellect is not equivalent to Plato’s demiurge, since it embodies certain characteristics of Plato’s One. Crucially, this seems to compromise any project of harmonising them from the beginning.

In the last part of (2), there is a puzzling interpretation of Aristotle who apparently claims that παρὰ [τούτων] [i.e., heaven and heavenly bodies] γὰρ εἶναι τὴν δημιουργίαν καὶ τὴν πρόνοιαν.Footnote 48 According to Proclus, Aristotle ascribes demiurgy and providence only to the heaven and not to the intellect as he should have.Footnote 49 The problem is that Aristotle obviously never refers to demiurgy or providence in explaining the nature or activity of the heaven. By demiurgy Proclus means a specific type of efficient causality, namely the one that brings about what is becoming/generated.Footnote 50 Since in Aristotle generation occurs only in the sublunary realm and is, most importantly, dependent on the circular motion of the heaven,Footnote 51 Proclus is able to claim that for Aristotle the heaven is ‘demiurgic’, whereas the intellect is not as it does not cause the cosmos’ being. What about providence? While Aristotle himself did not develop a theory of divine providence, Alexander filled this gap with his treatise On Providence.Footnote 52 There, the same view attributed here by Proclus to Aristotle is encountered: providence is exercised by the heaven over the sublunary realm and consists in safeguarding the regular generation and destruction as well as the eternity of species.Footnote 53 Given Alexander’s significance as a commentator and Proclus’ frequent references to the ‘Peripatetics’, he presumably has here Alexander’s interpretation of Aristotle in mind.Footnote 54

Proclus has made clear so far that Aristotle’s metaphysics departs in crucial points from Plato’s and has thus significant shortcomings. By denying the existence of the One and wrongly attributing some of its characteristics to the intellect, Aristotle fails to make the intellect an efficient cause of the cosmos’ being. Unlike Baltes (Reference Baltes1978: II, 69), who claims that this and the previous passage (2.131.11–132.14 [1.294.28–295.19]) ‘stand out in their effort to harmonise the teachings of both philosophers’ (‘zeichnen sich durch das Bemühen um Harmonisierung der Lehren der beiden Philosophen aus’), I see almost no harmonisation effort on Proclus’ behalf in 2.132.15–133.4 [1.295.20–7]. However, Proclus makes clear how Aristotle went wrong and implicitly offers a solution: if one ‘upgrades’ some of the attributes, for example, by attributing non-multiplicity to the One and so on, an agreement can be established.

He makes this explicit at In Parm. 4.973.6–12, where he states that the Peripatetics

declare that there is one thing only which is non-multiplied and unmoved cause as an object of desire (ἀπλήθυντον καὶ ἀκίνητον αἴτιον ὡς ὀρεκτόν); and they attribute (προσάπτοντες) to the intellect what we say of the cause which is situated above the intellect and intelligible number. Insofar as they consider the first principle in this way they were correct, for the beings must not be governed badly nor should multiplicity be the principle of the beings, but the One; but insofar as they postulate that the intellect and the One are the same thing, they are not correct.

Again, we have here the charge of falsely attributing non-multiplicity to the intellect. Interestingly, Proclus also adds an attribution Aristotle got right, namely the intellect as ἀκίνητον αἴτιον ὡς ὀρεκτόν – an expression which Proclus himself uses (e.g., ET §34.38.3). Proclus regards Aristotle’s intellect as incorporating attributes from both Plato’s One and demiurge. Thus, as Aristotle’s metaphysics presents itself, it is not in agreement with Plato. This explains, for instance, why Proclus elsewhere accuses Aristotle of possessing only half of the truth when denying the efficient causality of the intellect (In Parm. 4.842.20–2). Plato’s views therefore form an indispensable corrective lest the student of metaphysics embraces Aristotelian heterodoxy and καινοτομία. For by studying Plato’s metaphysics Aristotle’s intellect can be ‘purified’ of certain inappropriate attributes, such as non-multiplicity and ultimate final causality, in order to reach a correct conception thereof.

4.3.2 Aristotelian versus Platonic Efficient Causes

Besides Aristotle’s confusion of theological principles and their characteristics, Proclus also accuses Aristotle of misunderstanding what efficient causality is. Aristotle pays only lip-service to the efficient cause since he does not conceive it as a productive cause that brings about being. That is, Aristotle might attribute it to the intellect (as he does to nature), but his understanding of efficient causality is fundamentally misguided so that he effectively denies it of the intellect. Thus, Aristotle does not have an efficient cause in the sense Proclus has in mind. This critique occurs at the beginning of his commentary on the Timaeus:Footnote 55

(1) For although they [Plato’s successors] may perhaps make mention of the productive cause as well, as when they affirm that nature is the origin of motion, they still deprive it of efficacity and productivity in the strict sense (τὸ δραστήριον καὶ τὸ κυρίως ποιητικόν), since they do not agree that this [cause] embraces the reason-principles (λόγους) of those things that are created through it but allow that many things come about spontaneously too.

(2) That is in addition to their failure to agree on the priority of a productive cause to explain all physical things at once (πάντων ἁπλῶς τῶν φυσικῶν ποιητικὴν αἰτίαν ὁμολογεῖν προϋφεστάναι), only those that are bundled around in generation. For they openly deny that there is any productive [cause] of things everlasting (τῶν γε ἀϊδίων οὐδὲν ποιητικὸν εἶναί φασι διαρρήδην). Here they fail to notice that they are either attributing the whole complex of the heavens to spontaneous generation, or claiming that something bodily can be self-productive. (1.3.3–13[1.2.15–29])

Proclus puts forward two criticisms: (1) nature conceived only as origin of motion is not productive in the strict sense; (2) there is no single productive cause of physical reality since eternal physical beings lack such a cause. Proclus turns here Aristotle’s well-known criticism of Plato – namely that Plato was unable to make use of the efficient cause (and the final cause) (Met. 1.6; GC 2.9) – against Aristotle himself.Footnote 56

(1) Regardless of the specific discussion of nature here, it is important to note the underlying assumptions Proclus makes about efficient causality which are quite different from Aristotle’s.Footnote 57 What Proclus says here about nature’s efficient causality, applies a fortiori to higher causes.Footnote 58 Productivity or efficiency here means to be creative and to bring something into existence as well as to cause its being, and not merely to move something, as the choice of words such as δραστήριον, ποιητικόν and ποιουμένων indicates. This usage is primarily influenced by the definition of cause in the Philebus.Footnote 59 Moreover, it also implies transmitting certain properties to a lower being – just as nature is supposed to do via its logoi – as well as preserving and completing the effect.Footnote 60 The term ‘efficient cause’ becomes in this way a richer concept which accounts for a thing’s motion and being. Proclus here appears to be well aware that at least Aristotle’s conception of efficient causality is not the same as Plato’s. He thus departs from a widespread ancient and modern interpretation according to which one can find Aristotle’s causes in Plato.Footnote 61

(2) In the second part of the passage, Proclus complains of the lack of a productive cause of physical reality.Footnote 62 This includes a relevant claim to my discussion of the unmoved mover’s causality. Proclus maintains that Aristotle limits efficient causality to generated (ἐν γενέσει) beings, that is, to the sublunary realm (1.3.8–13 [1.2.24–9]). Most significantly, he then accuses Aristotle of denying that eternal beings (τῶν ἀϊδίων), that is, the celestial beings and the cosmos itself, have an efficient cause – a claim repeated later on in the commentary.Footnote 63 The reason, as becomes clear soon, is that Proclus takes Aristotle’s intellect not as an efficient cause of the cosmos’ being but only as an efficient cause of its motion. But the latter, as has been made clear, is not the type of efficient causality Proclus has in mind.

4.3.3 The Critique of Aristotle’s Intellect in the Commentary on the Timaeus 1

After these preliminary remarks on Aristotle’s metaphysics, specifically on the intellect and the nature of the efficient cause, I now turn to Proclus’ main criticism of Aristotle’s unmoved mover, which has to be read in conjunction with these general objections. In his criticism, Proclus shows that Aristotle’s commitment to both

(1) the intellect as cause of the cosmos’ essential desire and

(2) the intellect as cause of infinite power

leads to the conclusion that

(3) the intellect is the efficient cause of the cosmos’ being.

Aristotle’s mistake lies in not endorsing (3) although it necessarily follows from either (1) or (2).

The passage examined here (In Tim. 2.90.17–93.17 [1.266.21–268.23]) has received less attention in scholarship.Footnote 64 By analysing it in greater detail I bring to light Proclus’ lengthy critical engagement with Aristotle and offer insights into his views of Aristotle’s metaphysics. The text starts with a brief doxography (2.90.17–91.8 [1. 266.21–267.4]) and then offers four objections (2.91.8–93.17 [1.267.4–268.22]). The first two are the philosophically most interesting and discussed in detail in Sections 4.3.3.2 and 4.3.3.3.Footnote 65

4.3.3.1 Doxography (In Tim. 2.90.17–91.8 [1.266.21–267.4])

Let us start with the doxography:

ἀποροῦσι δέ τινες, ὅπως ὁ Πλάτων ἔλαβεν ὡς ὁμολογούμενον τὸ δημιουργὸν εἶναι τοῦ παντὸς εἰς παράδειγμα βλέποντα· μὴ γὰρ εἶναι δημιουργὸν εἰς τὸ κατὰ ταὐτὰ ἔχον ὁρῶντα· πολλοὶ γὰρ καὶ τούτου προεστᾶσι τοῦ λόγου τῶν παλαιῶν· οἱ μὲν γὰρ εἶναι δημιουργὸν Ἐπικούρειοι καὶ πάντη τοῦ παντὸς αἴτιον οὐκ εἶναί φασιν, οἱ δὲ ἀπὸ τῆς Στοᾶς εἶναι μέν, ἀχώριστον δὲ ὑφεστάναι τῆς ὕλης, οἱ δὲ Περιπατητικοὶ χωριστὸν μὲν εἶναί τι, ποιητικὸν δὲ οὐκ εἶναι, ἀλλὰ τελικόν· διὸ καὶ τὰ παραδείγματα ἀνεῖλον καὶ νοῦν ἀπλήθυντον προεστήσαντο τῶν ὅλων. Πλάτων δὲ καὶ οἱ Πυθαγόρειοι τὸν δημιουργὸν ὕμνησαν τοῦ παντὸς ὡς χωριστὸν καὶ ἐξῃρημένον καὶ πάντων ὑποστάτην καὶ πρόνοιαν τῶν ὅλων, καὶ μάλιστά γε εἰκότως·

Some people are perplexed about the way that Plato has taken as agreed that there is a demiurge of the universe who looks to a paradigm. For, they think, no demiurge looking to what remains the same exists. In fact many of the ancients were proponents of this argument. The Epicureans deny that a demiurge exists and state that there is no cause of the universe at all. The [philosophers] from the Stoa say he exists, but that he is inseparable from matter. The Peripatetics state that a separated entity exists, but that it is a final rather than an efficient cause. For this reason they have both destroyed the paradigms and placed a non-multiple intellect at the head of the universe. Plato and the Pythagoreans, however, have celebrated the demiurge of the universe as separate and transcendent and founder of all things and providence of the whole. And this is indeed an eminently reasonable view.

This doxographical account – which is in many respects representative of Proclus’ views on the history of philosophyFootnote 66 – presents the different opinions on the nature of god and his causation in an ascending order. Proclus does not focus on the divine in general but rather on the equivalent of the demiurge in the five philosophical schools he considers. Thus, the demiurge of the Timaeus, as creator of the universe (τοῦ παντός), separate (χωριστόν), transcendent (ἐξῃρημένον), founder of all things (πάντων ὑποστάτην) and providential towards the whole (πρόνοιαν τῶν ὅλων), is the benchmark for Proclus.Footnote 67 Specifically the last two characteristics, which emphasise the productive activity of the demiurge towards the cosmos,Footnote 68 are decisive in understanding Proclus’ position throughout this passage.

The survey starts with the Epicureans, who are doctrinally the furthest away from the truth espoused by the Plato and Pythagoreans, with whom the account culminates. Most importantly, the Peripatetics – including Aristotle – are presented as closest to Plato and the Pythagoreans, since they maintain that there is an entity which is separate from the cosmos (unlike the Stoics) and also its cause (like the Stoics but unlike the Epicureans). In contrast to In Tim. 2.132.15–16 [1.295.20–1], Proclus emphasises here the characteristics that Aristotle and the Peripatetics attributed correctly to the intellect, namely χωριστός and αἴτιον. These can be added to other correct attributes like ἀκίνητος and ὀρεκτός. Yet, their metaphysics is still deficient, very much along the lines discussed above (In Tim. 2.132.15–133.4 [1.295.20–7]). For they mistakenly attribute to this separate cause only final and not also efficient causality. For Proclus this has the consequence (διὸ) that they abolish the paradigm and posit a ‘non-multiplied intellect (νοῦν ἀπλήθυντον) in front of the whole’. Proclus claims here that, by denying the efficient causality of the intellect, the Peripatetics deny also the existence of the paradigmatic causes and posit the intellect as the first principle.Footnote 69 The latter, as has been seen, is the most serious error in the eyes of a Neoplatonist.

Here again, like in Section 4.3.1, it emerges that Proclus’ objections to the causality of Aristotle’s intellect are part of a general critique of Aristotle’s metaphysics. It is thus after this introductory doxography (In Tim. 2.90.17–91.8 [1.266.21–267.4]) that Proclus proceeds with his specific criticisms. Proclus’ goal in the first (2.91.8–16 [1.267.4–12]) and the second objection (2.91.17–92.9 [1.267.12–24]) is to show that Aristotle’s reasoning actually commits him to accept that the unmoved mover is a final as well as an efficient cause of being:

O1 Insofar as the intellect is a final cause, it is necessarily an efficient cause as well. If the intellect causes the cosmos’ essential desire, it also brings about the cosmos’ being.

O2 Insofar as the intellect possesses infinite power and transmits it to the universe, it is necessarily an efficient cause as well. If the intellect causes the cosmos’ eternal motion, it causes the cosmos’ eternal being.

4.3.3.2 First Objection (In Tim. 2.91.8–16 [1.267.4–12])

Let us have a closer look at the first objection.

[O1] εἰ γὰρ ἐρᾷ ὁ κόσμος – ὥς φησι καὶ Ἀριστοτέλης – τοῦ νοῦ καὶ κινεῖται πρὸς αὐτόν, πόθεν ἔχει ταύτην τὴν ἔφεσιν; (i) ἀνάγκη γάρ, ἐπεὶ μή ἐστι τὸ πρῶτον ὁ κόσμος, ἀπ’ αἰτίας ἔχειν τὴν ἔφεσιν ταύτην αὐτὸν τῆς εἰς τὸ ἐρᾶν κινούσης· κινητικὸν γὰρ τὸ ὀρεκτὸν τοῦ ὀρεκτικοῦ φησιν εἶναι καὶ αὐτός. (ii) εἰ δὲ τοῦτο ἀληθές, ὀρεκτικὸν δὲ ὁ κόσμος αὐτῷ τῷ εἶναι καὶ κατὰ φύσιν ἐκείνου, δῆλον ὅτι καὶ τὸ εἶναι αὐτοῦ πᾶν ἐκεῖθεν, ἀφ’ οὗ καὶ τὸ εἶναι ὀρεκτικόν ἐστι.

If the cosmos loves the intellect – as Aristotle says – and it comes into motion in relation to the intellect, where does it obtain this desire from? (i) It is necessary, since the cosmos is not that which is first, that it obtain this desire from a cause which moves it towards love. After all, he himself says that it is the object of desire that moves the desiring subject. (ii) If this is true and the cosmos is desiring of the intellect through its [i.e., the cosmos’] very being and in accordance with its nature, it is clear that its entire being comes from there, including also its being the desiring subject.

This objection is loosely based on Metaphysics 12.7 and repeats the charge made against the Peripatetics in the doxography that the intellect is not ποιητικόν. In brief, Proclus argues that if the intellect is the final cause (i.e., the object of desire) of the cosmos, as Aristotle maintains, it also needs to be the efficient cause of the cosmos’ being.Footnote 70 The argumentation proceeds in two steps. First (i), Proclus claims that the cosmos is not a first or principle (τὸ πρῶτον) – unlike the intellect – and as such is dependent on a cause (ἀπ’ αἰτίας) for having a certain desire. That is, insofar as the cosmos desires the intellect, the intellect must account for or cause that desire in the first place. Moreover, the intellect as cause of the desire moves the cosmos towards love (τῆς εἰς τὸ ἐρᾶν κινούσης). The reason, so Proclus, is that, according to Aristotle, himself the object of desire (ὀρεκτόν) and the cause of motion (κινητικόν), that is, the final cause and moving cause, coincide – at least in the case of the intellect. Qua object of desire the intellect causes the motion of the cosmos. Proclus’ interpretation matches modern accounts: Judson (Reference Judson2019: 185–6), for instance, claims that the unmoved mover is an efficient cause of the heaven’s desire, which, as proximate cause, brings about the heaven’s motion. So far, so Aristotelian, one could say.

Then, in the second step (ii), Proclus’ argument takes a decisively Neoplatonist turn. He states that if the object of desire is the cause of the desire in the desiring subject, and the desire for the intellectFootnote 71 in the cosmos is essential/due to its being (αὐτῷ τῷ εἶναι) and according to its nature (κατὰ φύσιν), then the intellect is not just the cause of the cosmos’ being desiderative but of the cosmos’ being (εἶναι) at all. In other words, if x’s desire of y is essential, and if y is the cause of x’s desire, then y is the cause of x’s being. Insofar as y causes not just a desire in x – as numerous other objects of desire would – but rather a desire inseparably linked to the being of and thus constitutive of x, y is also an efficient cause of x’s being. In turn, x only has an essential desire towards y, if y is the cause of x’s being. In any case, Proclus is here not committed to the blatantly false claim that every object of desire is causally responsible for the being of the desiring subject.Footnote 72

Two issues which are crucial for the success of the argument arise here and merit further investigation. First, it is not straightforward why Proclus assumes that the cosmos’ desire for the intellect is essential, as Aristotle does not express this explicitly. I take it that Proclus’ assumption is based on the view that eternal motion is a sine qua non for the cosmos’ existence, and in order to maintain it the cosmos has to continually desire the intellect. If the cosmos stops desiring the prime mover, it stops moving. In this way, its desire can be rightly regarded by Proclus as ‘essential’.

Secondly, what does Proclus mean by the term einai (εἶναι) – as in the intellect is the cause of the cosmos’ εἶναι – in this context? Does it denote existence, essence or being (as translated here) – or somehow all three? Although the meaning of this ambiguous term is crucial in understanding this and the following objection, scholarship is silent on this issue. Steel (Reference Steel, Pépin and Saffrey1987a) in his discussion of this text chooses the translation ‘existence’, as do also Sorabji (Reference Sorabji1988: 252) and d’Hoine (Reference d’Hoine and Falcon2016: 390). The problem is that usually the technical term for ‘existence’ is huparxis (ὕπαρξις) in Proclus, as when he discusses the ὕπαρξις τῶν εἰδῶν at In Parm. 4.880.19.Footnote 73 Steel is indeed aware of this and, thus, when he cites Proclus’ claim that sensibles get their desire ‘from the source of their ὕπαρξις and εἶναι’ (In Parm. 4.842.25), he renders ὕπαρξις as ‘existence’ and εἶναι as ‘being’. I assume that εἶναι does not refer here just to factual existence, whereby the attribution of εἶναι to cosmos simply means that the cosmos exists. Instead, it is a richer notion that includes the mode of existence as well as certain essential attributes, as the expression τὸ εἶναι αὐτοῦ πᾶν and τὸ εἶναι ὀρεκτικόν at 91.15–16 [267.11–12] seem to indicate. Parallel evidence from ET suggests the same (e.g., ET §28.32.29, §31.34.35, §34.36.24).Footnote 74 To put it in contemporary terms, εἶναι here has an existential and predicational dimension: due to the causation of the intellect the cosmos exists and does so in a certain way.Footnote 75 The best translation therefore seems to be ‘being’, as it is able to render the term’s ambiguity also in Proclus.

What do we make of Proclus’ objection here? Proclus might be right in claiming that Aristotle cannot regard the unmoved mover exclusively as a final cause, since causing the desire in the desiring subject can be considered as being an efficient cause. Indeed, as pointed out, this is the interpretation of the intellect endorsed by Judson (Reference Judson, Gill and Lennox1994: 164–5) and (Reference Judson2019: 185–6.) Yet, Proclus goes further than this by concluding that something that causes the cosmos’ essential desire also causes the cosmos’ being. If εἶναι here meant ‘existence’, the move would be warranted insofar as the unmoved mover would be the remote efficient cause of the cosmos’ existence by bringing about its essential desire and, thus, its eternal motion. But for Proclus, εἶναι seems to mean here more than factual existence. Thus the unmoved mover would not just be the reason why the cosmos exists full stop but rather why it exists in a certain way. Even here, however, Aristotle could agree: the desire-induced motion makes the cosmos what it is – namely a complex system of spheres that ultimately influence the sublunary realm.Footnote 76 In this way, the intellect would be the cause of the cosmos being in a certain way.Footnote 77

Yet, while this might be the case in the way the argument is presented here, it becomes clear from other passages that Proclus has a distinctly Neoplatonist conception of the intellect’s causality. In ET §34, he explains that ‘everything proceeds (πρόεισι) from intellect’ (38.3–4), including the cosmos. This procession has to be understood of course by considering Proclus’ understanding of the constitution of being, which is characterised by the triad μονή – πρόοδος – ἐπιστροφή.Footnote 78 According to this, an effect proceeds from its cause, which already contains it in a superior way (ET §7), in order to differentiate itself from it.Footnote 79 While I do not see any evidence that Proclus would believe that Aristotle agrees to this, Proclus’ specific objection in 2.91.8–16 [1.267.4–12] still stands as a line of argument that could be accepted by an Aristotelian.

4.3.3.3 Second Objection (In Tim. 2.91.17–92.9 [1.267.12–24])

From the fact that the intellect causes the cosmos’ essential desire the last objection concluded that it causes the cosmos’ being as well. The second objection reaches the same conclusion, that is, that the intellect is the cause of the cosmos’ being, by starting from the intellect’s causation of the cosmos’ eternal motion. Proclus’ reasoning here is based on the ‘infinite power argument’, where δύναμις is understood as a power to do something not as a potentiality to undergo something. Although we find a brief version of the argument in Syrianus (In Met. 117.25–118.11), Proclus seems to be the first to make extensive use of it by not only summarising the argument itself and its background, in EPFootnote 80 and elsewhere, but also by using it against Aristotle.Footnote 81

[2. Objection] πόθεν δὲ τὸ κινεῖσθαι ἐπ’ ἄπειρον πεπερασμένον ὄντα; πᾶν γὰρ σῶμα πεπερασμένην ἔχει δύναμιν, ὥς φησι. πόθεν οὖν τὴν ἄπειρον ἔσχε ταύτην τοῦ εἶναι δύναμιν τὸ πᾶν, εἴπερ μὴ ἐκ ταὐτομάτου κατὰ τὸν Ἐπίκουρον; ὅλως δέ, εἰ τῆς κινήσεως αἴτιος ὁ νοῦς τῆς ἀπείρου καὶ ἀδιακόπου καὶ μιᾶς, ἔστι τι τοῦ ἀιδίου ποιητικόν· εἰ δὲ τοῦτο, τί κωλύει καὶ ἀίδιον εἶναι τὸν κόσμον καὶ ἀπ’ αἰτίας εἶναι πατρικῆς; καὶ γὰρ ὡς τοῦ κινεῖσθαι δύναμιν ἄπειρον ἐκ τοῦ ὀρεκτοῦ λαμβάνει, δι’ ἣν ἐπ’ ἄπειρον κινεῖται, οὕτω καὶ τὴν τοῦ εἶναι δύναμιν ἄπειρον ἐκεῖθεν πάντως λήψεται διὰ τὸν λόγον ὅς φησιν ἐν πεπερασμένῳ σώματι μὴ εἶναί ποτε δύναμιν ἄπειρον.

From where, moreover, does the cosmos, though itself finite, derive its infinite motion? After all, as he [Aristotle] says, every body has a power that is finite. From where, then, does the universe derive this infinite power to exist, if it does not obtain it spontaneously in accordance with [the doctrine of] Epicurus? In general, if the intellect is cause of the infinite and uninterrupted and single motion, there exists an entity which is the efficient cause of that which is everlasting. If this is the case, what prevents the cosmos from being both everlasting and derived from the paternal cause? For just as it obtains from the object of desire an infinite power of motion, through which it moves to infinity, so it will certainly obtain the infinite power of being from there in virtue of the argument which states that there can never be an infinite power in a finite body.

In brief, Proclus again objects to reducing the unmoved mover to a final cause. Instead, it has to be an efficient cause as well, since it must cause the infinite being of the cosmos.

The argument compressed in the first three lines is:

(1) A finite magnitude has a finite power.

(2) Moving for an infinite period of time requires an infinite power.

(3) The cosmos is a finite magnitude and moves for an infinite period of time.

(4) Infinite power is either intrinsic (in certain unextended entities) or extrinsic (in magnitudes).

(5) Given (3), the cosmos’ infinite power is extrinsic.

In establishing that the cosmos’ eternal motion requires an external infinite power, the question poses itself as to the origin (πόθεν) of this infinite power. Before Proclus considers the two options, he claims that moving for an infinite period of time (τὸ κινεῖσθαι ἐπ’ ἄπειρον) implies being for an infinite period of time (τὴν ἄπειρον … ταύτην τοῦ εἶναι δύναμιν). This implication is absolutely crucial for Proclus, as it transforms the proof from an argument about motion to one about being.Footnote 82 Again, the same ambiguity concerning εἶναι arises. If it means ‘existence’ here, Proclus’ identification of moving for an infinite period of time with existing for an infinite period of time is warranted insofar as the cosmos cannot exist if it does not move continuously. A stand-still means, in fact, the end of the cosmos’ existence. Yet, considering the previous passage (In Tim. 2.91.8–16 [1.267.4–12]) as well as other related texts such as ET §31 and §34, εἶναι seems to have a broader meaning.

The background of the argument is Aristotelian and found in Physics 8.10 and Metaphysics 12.7.1073a5–11 which refers back to the Physics. As discussed in Section 4.2.3, in these passages Aristotle sets out to demonstrate the indivisibility of the prime mover. According to Proclus’ interpretation, Aristotle (1) attributes in these lines infinite power to the unmoved mover, which (2) is transmitted to the cosmos. While some commentators have questioned either (1) or (2), or both, since these claims are not mentioned explicitly by Aristotle, I believe Proclus’ interpretation is correct and a majority of modern scholars, for example, Judson (Reference Judson, Gill and Lennox1994; Reference Judson2019), Laks (Reference Laks, Frede and Charles2000) and Touzzo (Reference Tuozzo2011), essentially concur. In short, Aristotle wants to show that the prime mover must be without magnitude, since due to its lack of infinite power a (finite) magnitude is unable to cause an infinite motion. This, however, implies that the prime mover possesses infinite power. For how – on this reasoning – could it otherwise cause an infinite motion? Moreover, the causation of the cosmos’ infinite motion can be considered as a transmission of power, since Aristotle describes how a mover with its power acts on something in order to change it (Phys. 8.10 266a24–30). This description clearly implies also the workings of the prime mover.

Given the accuracy of Proclus’ reading, I claim that his ensuing objection is well-founded: as shown, many modern scholars have struggled to understand how the idea of the unmoved mover transmitting its infinite power to the universe can be squared with Aristotle’s view of the unmoved mover’s presumed mode of operation, that is, as an object of desire. Proclus, I argue, rightly recognises that this argument offers a strong foundation for assuming the intellect’s efficient causality. He is thus right in his objection: Insofar as we take Aristotle on his word and understand the unmoved mover as transmitting power to the universe – and there are, as I argued, strong textual reasons for assuming that –, the unmoved mover cannot be simply a final cause and also not just a moving cause. Instead, the argument requires a metaphysically richer notion of efficient causality – which Proclus and later commentators readily provide.

4.3.3.4 Conclusion

In order to assess Proclus’ approach, I have to consider first how much of the interpretative strategy and arguments are genuinely Proclean. As often with Proclus’ philosophy, including his criticisms of Aristotle, a strong influence by his teacher Syrianus is detectable.Footnote 83 After all, Proclus himself claims after presenting his objections of Aristotle’s intellect: ‘In relation to Aristotle, then, many refutations have been made by many people’ (In Tim. 2. 93.18–19 [1.268.23]).Footnote 84 As mentioned, Syrianus holds a very similar view of Aristotle’s intellect (e.g., In Met. 10.33–11.5Footnote 85; 175.21–23) and we find evidence for both of Proclus’ objections, O1 and O2.Footnote 86 Syrianus, like Proclus, claims that Aristotle failed to draw explicitly the conclusion from these two arguments that the intellect is an efficient cause of being: ‘to this extent he falls short of his father’s philosophy’ (tr. Dillon and O’Meara; 10.37: τοσοῦτον ἀπολείπεται τῆς πατρίου φιλοσοφίας).Footnote 87 Yet, since this conclusion follows from his own principles (118.27: ἐξ ὧν δίδωσιν), Aristotle is ‘forced to accept the same doctrine whether or not he wants’ (ibid.: εἰς ταὐτὸν ἐκείνῳ δόγμα καὶ ἑκὼν καὶ ἄκων καταναγκάζεται). Thus, based on the necessary implications of his arguments, Syrianus claims that Aristotle in this respect ‘says the same things as Plato in another way’ (27–8: τὰ αὐτὰ τρόπον ἕτερον ἐκείνῳ φθέγγεσθαι). Like Proclus and in contrast to Ammonius and Simplicius, Syrianus believes that, although Aristotle is committed through his own postulates to view the intellect as an efficient cause of being, he fails to take this position himself.Footnote 88 Syrianus states clearly that, once the conclusion has been drawn from Aristotle’s arguments, there is no doctrinal disagreement between Plato and Aristotle on the causality of the intellect and the intelligibles.Footnote 89 Thus, in contrast to Proclus, Syrianus emphasises the resulting agreement between Plato and Aristotle in this respect. At the same time, Syrianus makes clear that this agreement was not Aristotle’s intention. Instead, Aristotle has to be forced (καταναγκάζεται) to accept it.

It is likely that Proclus goes further in his criticism than Syrianus – although this cannot be conclusively determined given our limited access to Syrianus’ works.Footnote 90 At In Tim. 2.91.4–5 [1.266.30–267.1] and 2.132.15–133.4 [1.295.20–7] Proclus clearly presents Aristotle’s metaphysics as deficient for rejecting the One and the paradigm as well as attributing characteristics to the intellect which actually belong to the One. Some of the objections have no correspondent in Syrianus, although he also maintains that Aristotle rejects the One (In Met. 118.21–2). However, in his critique of the causality of Aristotle’s intellect Proclus greatly resembles Syrianus. Similarly to his teacher, Proclus criticises Aristotle by starting from Aristotle’s own premises. Proclus’ view is that by following Aristotle’s own reasoning – especially his infinite power argument – Aristotle should have committed himself to the position that the intellect is an efficient cause of the cosmos’ being. This is the main difference from modern versions of this interpretation. In both (a) and (b), as set out in Sections 4.3.3.2 and 4.3.3.3, Proclus reaches from unquestionably Aristotelian premises – the unmoved mover causes (a) the desire and (b) the eternal motion of the cosmos – the (questionably Aristotelian) conclusion that the unmoved mover is the cause of the cosmos’ being. Aristotle failed to reach this conclusion due to a limited understanding of efficient causality, as seen in the discussion of In Tim. 1.2.21–3.13 [1.2.15–29]. His understanding of the efficient cause primarily as a moving cause effectively denies the type of causality Proclus has in mind for the unmoved mover.

In my opinion, Proclus’ observation that Aristotle’s view of the first principles differs from Plato’s metaphysics just as the Aristotelian type of efficient causality differs from the Platonic one makes his exegesis of Aristotle more nuanced and closer to the original than the interpretations of Ammonius and Simplicius (especially, if one considers their shared Platonist commitments) who attribute a Platonic type of efficient cause to Aristotle’s intellect. By contrast, Proclus shows clearly that Aristotle’s intellect does not share the same characteristics as Plato’s demiurge. Yet, at the same time, he paradoxically contributes to the dissemination of this Platonising-creationist reading of Aristotle’s intellect, since his arguments are picked up by his pupil Ammonius – but with a different intention.

4.4 Ammonius and Simplicius on the Causality of Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover

In the following, I contrast Proclus’ interpretation with Ammonius’ and Simplicius’. Ammonius wrote a treatise on this issue, excerpts of which are preserved – and endorsed – by Simplicius’ commentary on the Physics. Since there is no in-depth analysis of Ammonius’ work, I first offer a reconstruction of its content, in which I also consider evidence from other commentaries by Ammonius’ pupils (4.4.1). Additionally, I set out Simplicius’ reasons for Aristotle’s reticence regarding the intellect’s causality, which, again, possibly mirror Ammonius’. This analysis allows me to situate the treatise within Ammonius’ intellectual climate (4.4.2). As I show, Ammonius’ main motivation for writing it was his desire to refute the interpretations of some Peripatetics, represented by Alexander, and some Neoplatonists, such as Syrianus and Proclus, which prevented the harmonisation of Plato and Aristotle on this issue. Finally, I reach a more general conclusion about the distinct approaches to Aristotle by Proclus and Ammonius/Simplicius (4.4.3).

4.4.1 Ammonius’ Treatise

In regard to their interpretation of Aristotle’s intellect, Syrianus and Proclus remained in opposition to other Neoplatonists. Those associated with the school of Alexandria took a different stance, which was strongly propagated by Ammonius, son of Hermias, in a treatise on this issue whose precise title is unknown.Footnote 91 Ammonius himself studied in Athens under Proclus – whom he greatly revered (In DI 1.7–11) – and had a personal connection to the Athenian school, since his father Hermias was a student of Syrianus and his mother Aedesia a relative of Syrianus. After his education in Athens, Ammonius left (around 470/5) for Alexandria where he had a rich teaching activity, especially on Aristotle (Phot. Bibl. §242.341b24: μᾶλλον δὲ τὰ Ἀριστοτέλους ἐξήσκητο), and counted among his pupils Simplicius, Philoponus, Olympiodorus and Asclepius.Footnote 92 While Ammonius’ commitment to Syrianus’ and Proclus’ type of Neoplatonism is debated, he undoubtedly broke with their anti-harmonist stance and (re-)established a more thorough harmony between Plato and Aristotle which is reflected in the writings of his students.Footnote 93 It is possible that Ammonius achieved this by simply returning to a position prevalent in the Athenian school under Plutarch of Athens until Syrianus became its head in AD 431/2. While I focus in this section mostly on Ammonius and Simplicius, I also refer to the writings of Ammonius’ other students, insofar as they are useful in reconstructing their teacher’s arguments or exegesis of a specific passage.Footnote 94 These philosophers too regard the Aristotelian god as a final cause and an efficient cause of being.Footnote 95

The most extensive evidence for Ammonius’ interpretation is preserved in a well-known passage at the end of Simplicius’ commentary on the Physics (1360.24–1363.24). The text can be divided in five parts. After briefly (i) introducing the problem and the goal of his discussion (1360.24–31), Simplicius (ii) underlines the final and efficient causality of the Platonic demiurge by referring to various passages (1360.31–1361.11). He then (iii) turns to Aristotle and demonstrates the efficient causality of the unmoved mover (1361.11–1362.10). Since this does not suffice, he shows in the next step (iv) that it is an efficient cause of the cosmos’ being (1362.11–1363.8). He (v) concludes with some final remarks on Ammonius’ book and the reasons for Aristotle’s reticence in calling the unmoved mover an efficient cause (1363.8–24). While the whole passage has attracted a certain attention in scholarship,Footnote 96 a close analysis of the procedure and the arguments is still outstanding as is also a discussion of its intellectual context. Such an analysis will help us in comparing the views of Ammonius/Simplicius with Proclus’.