In the first half of the twentieth century, racial covenants were a tool used by white people to claim neighborhoods as white spaces by adding language to housing deeds to prohibit people of color from purchasing or living in a particular house (unless they were domestic servants). These covenants were made unenforceable as a result of the Supreme Court’s decision in the Shelley v. Kraemer case in 1948 and illegal with the passing of the Fair Housing Act in 1968; however, recent research has shown that they cast a long shadow—for example, their impact on neighborhoods can still be felt in present-day health and well-being disparities.Footnote 1 Historians have long known about racial covenants but did not have a method to make visible the extent of such covenants across a community.Footnote 2

In 2016, the Mapping Prejudice Project (MPP), housed at the University of Minnesota, developed a methodology to fill the gap in historical research.Footnote 3 MPP is an example of a public humanities project at its best—it is deeply embedded in rigorous historical scholarship and seeks to bring that scholarship to a public audience.Footnote 4 After scanning thousands of property deeds and flagging potential racial language using optical character recognition, the flagged deeds need to be checked to see if the language is part of a racial covenant or other language; for example, does it contain language that only white people may live in the house or that Mrs. White was the buyer? MPP crowdsources this second part of the project inviting community members to participate in transcribing the deeds. Based on the information community members discover, MPP creates a map showing the spread of racial covenants over time.Footnote 5 Their work process makes this history relevant to a public audience and involves them in accomplishing the research.

Since the 2017–2018 academic year, St. Catherine University (St. Kate’s) has partnered with MPP to uncover the history of racial covenants in Ramsey County, where St. Kate’s is located, and to use a variety of disciplinary lenses to explore racial covenants’ enduring impact in our community. The Center for Community Work and Learning (CWL) and faculty from a range of departments built an interdisciplinary public humanities research project with significant student involvement and ample opportunities for community-engaged learning (also known as service-learning). The project is called “Welcoming the Dear Neighbor?” (WTDN)—a title that references the mission of the Sisters of St. Joseph, St. Kate’s founders, whose charism is “love of the dear neighbor without distinction.”Footnote 6

This article shares our experience and evidence of the impact on students across the university to show how this kind of public humanities work creates opportunities for faculty and staff scholarship and promotes high-impact practices, including collaborative research and community-engaged learning, for the mutual benefit of students, faculty, staff, and the community. We highlight opportunities and challenges for projects that aim to educate the campus and broader community about racial injustices within housing. We describe lessons learned and ideas for faculty and staff interested in starting similar efforts on their campuses. We conclude with both a qualitative case study of one student’s experience and quantitative evidence from student surveys to provide evidence of the project’s impact more broadly.

The project: Welcoming the Dear Neighbor?

St. Kate’s is a Catholic women’s college in St. Paul, Minnesota. Founded in 1905 by the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, its mission is to educate women to lead and influence. At St. Kate’s, 99.7% of undergraduate students identify as female in the College for Women. The College for Adults and the Graduate College are co-educational. In the College for Women, 48.6% of the students identify as Black, Indigenous, or People of Color. In 2023, 17.6% identified as Black or African American, 13.8% of the undergraduate population identified as Asian, and 12.6% as Hispanic/Latina. Pell Grant recipients make up 41.2% of the student body of the College for Women.Footnote 7

Though St. Kate’s has a long-standing tradition of community-engaged learning and students who are very interested in social justice, some faculty and students experienced barriers to this kind of public-facing work. Students have significant demands on their time from school, work, home, and community responsibilities, making it challenging to engage in work outside of class time and without pay. One attractive feature of the deed transcription project is that the work was often completed during class sessions, making it accessible to all students, as long as they were in class, whether in an in-person, virtual, or hybrid environment.

Initially, MPP focused on Hennepin County (home to the city of Minneapolis). While our students were enthusiastic about that project, they were often curious about Ramsey County—home to the city of St. Paul, St. Kate’s, and just across the Mississippi River from Minneapolis. A Public Policy student undertook initial archival work to uncover deeds around the St. Kate’s campus as her honors capstone project.Footnote 8 Building on this effort, D’Ann Urbaniak Lesch, director of CWL, initiated contact with Ramsey County to get the process started, which also led to the creation of the WTDN group. Unlike Hennepin County, Ramsey County’s deeds were not yet digitized, so though Ramsey County agreed to take on this work, the deeds needed to be scanned before the transcription work could begin.

In the meantime, WTDN’s faculty, staff, and students started to investigate the hidden histories of housing discrimination, segregation, and racism in St. Paul, and the larger county by conducting interdisciplinary research and collaborating with neighborhood and community organizations. Examples include history students who did archival work searching newspaper microfilm for articles about housing segregation; art students who made posters for the History Theater’s production of a play about housing discrimination; economics students who explored census data about Ramsey County neighborhood demographics; and sociology students who did interviews about families experiences with homeownership.

Since the inception of the project, more than 1,400 St. Kate’s students have participated in the WTDN project across the university—in courses ranging from the introductory first-year course to a capstone course in the Doctor of Physical Therapy program. Students span all degree levels, from associate and bachelor’s to graduate programs. Faculty and students from a wide range of disciplines have been involved, including sociology, communications, occupational therapy, social work, library science, MBA, art and art history, history, public health, data science, political science, and economics. All first-year seminar classes have a community-engaged learning project embedded in the class. In the fall of 2024, out of 30 first-year seminar sections, 20 will engage WTDN by participating in the deed transcription efforts. More than 400 students in the fall semester alone will be introduced to the project and invited to continue work with this multiyear effort.

In addition to deed transcription in classes and other community-engaged projects, students and faculty conduct research using the WTDN themes and/or the MPP data. These are opportunities for students to bring their research into the broader community and do projects that have a real-world impact. The university has a strong collaborative undergraduate research program that supports students who want to do research together with professors. Funding from CWL’s Assistantship Mentoring Program and the university’s Summer Scholars program provides paid opportunities for students. Some students enter this more in-depth research experience after completing the deed transcription work in class, while others learn about it from their faculty members or community presentations. Overall, 30 students have worked with faculty in the Economics, Political Science, Sociology, History, and Public Health departments in research projects beyond the deed transcription work, resulting in published papers and a multitude of presentations to community groups and conferences.Footnote 9

One example of the outward-facing work has been our partnership with a nearby St. Paul neighborhood, Como Park. St. Paul is organized into a series of neighborhood organizations that facilitate the city’s support of neighborhood initiatives. For the last three years, St. Kate’s has partnered with Como Park in District 10 to learn more about the history of places and people in the community and also worked together to reckon with histories of racism that exist in the neighborhood. Students in history, art, and political science have worked on this initiative. In addition to practicing methodologies outside their home disciplines, the students have also practiced constructive dialogue—providing the work that the neighborhood is asking for and challenging them to reckon with the hard parts of their history in more deliberate ways.

Lessons learned: Successes and challenges

The project has been a remarkable success—the connection to place, openness to faculty, staff, and student participation, and a willingness to think expansively have been key. The WTDN project is a local public humanities project about the community where our university is located and where many of our faculty, staff, and students live. Focusing on something so local has created a different kind of purpose and immediacy to the project. We are not just doing scholarly work for the sake of scholarly work, but also doing work to improve the place where we live and work each day. The localness of the project also allows for a different kind of participation. We take students to the archives, present to the schools and public spaces referenced in our research, and meet with neighbors living in neighborhoods impacted by what we are learning.

Rachel A. Neiwert, a historian working on the project, is a British historian by training, but she had struggled to engage students in collaborative research (because, as it turned out, students did not like looking through thousands of pictures brought back from the British Library). By working with the WTDN project, she was able to engage students in all parts of the research process. In fact, most of the faculty, staff, and students working with the WTDN projects have other areas of expertise and often do not even see themselves as humanities scholars. The WTDN project has been a way to break down the silos of work and expertise that the academy often privileges. We have developed new areas of expertise to support this work, and the work is stronger because of its interdisciplinary nature. It has been critical that our university supports this work by viewing it as a public scholarship that counts toward tenure and promotion.

While Neiwert would describe this as a public humanities project, economist Kristine West might see it more as a social science project where students can apply their analytic skills to investigate themes of economic inequality. The very notion of a public humanities project allows for an expansiveness in the kinds of questions, topics, and involvement from faculty, staff, and students because we are all learning from human experience regardless of our disciplinary background. Our research is richer when it brings in a variety of disciplinary perspectives and we do not limit ourselves by academic silos.

The project has also succeeded because it is collaborative. By collaborating with the MPP, housed at an R1 university, which is very different from our institution, we each gain new expertise and perspectives, share research material, and share our students as well. During COVID-19, graduate students working with MPP led deed transcription sessions with St. Kate’s students and St. Kate’s students have done internships with MPP. A strong partner was crucial for the work. It was also critical to have support from our own university through the CWL (now part of the Office of Scholarly Engagement). Lesch, the director, has been a tireless supporter and advocate for the project. Her in-depth knowledge of university faculty, staff, and university resources meant she could make connections and help hold the project together.

One of the challenges of this particular public humanities project is the nature of the project focus. Systemic racism within housing is a complex topic and one that people approach with a wide variety of lived experiences. For example, a specific issue was how to treat the language of the racial covenants in a way that was historically accurate and also respectful of the fact that the words used have been used to demean and diminish. The descriptions found in the racial covenants—and also promoted in advertisements of new housing developments—often used historical language that modern audiences would find unacceptable and inappropriate. For example, the words “negro” or “mongoloid” elicit understandably strong reactions. The team worked to respect historical accuracy—never changing the primary source material—while encouraging students and others who were engaged in deed coding to wrestle with the terminology used. At the start of each educational session, we named the challenge and noted that this project is one that examines harm done and harm that continues and asked students to think about what it means to be thoughtful about how we talk about and use language given this context.

COVID-19 was both a challenge and an opportunity—we had just delved into this project as the pandemic struck. As a higher education institution, we had to pivot to put curricular and co-curricular experiences online, which the racial covenant work fortunately fit into nicely. However, other considerations had to be made, such as how to facilitate discussions and how to continue to engage with the community outside of St. Kate’s. In addition, a few months after we were getting situated in the virtual public humanities space, George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis. This racial injustice was close to home—the next county over from St. Kate’s. MPP was now in the spotlight nationally and even internationally. How the creation of white spaces and policing contributed to this injustice was in the daily news. With even more impetus to untangle systemic racism and a lot more attention to historical injustice and present-day impacts, we continued our work but needed to recognize the shift in the landscape.

Lastly, there were challenges in motivating and contextualizing the deeds for students. Housing deeds are wordy and uninviting. Looking for a clause within a legal document as part of a process that many of our students had to go through (i.e., many did not own their own homes) was not immediately exciting. Though MPP’s online process made it accessible, there were still knowledge gaps and uncertainty. Faculty, staff, and student leaders reassured the student (and other) participants that they could do this, that they could ask questions, and that in the end, their work was also done by multiple other people, so they didn’t have to worry if they made a mistake. In many cases, doing the deeds transcription work together, during class time, allowed for a teamwork atmosphere with the experienced student researchers teaching students how to do the coding, and then encouraging them to ask questions as they all participated together, getting through as many deeds as they could in the time allotted.

Qualitative evidence: Student experience

A strength of the project is that it has become interwoven into the curricular and co-curricular experience in a way that can follow students through their college experience. Victoria Delgado-Palma, a triple major in International Studies (an interdisciplinary humanities major housed in the History department), Economics, and Political Science, describes her overall experience with the WTDN project as follows:

The Welcoming the Dear Neighbor? Project has really brought everything together. I find the theories that we study in class so much more relevant—because I see it all the time now! Without having the community engagement this wouldn’t have the same impact. I grew up here and, based on my background, I always knew discrimination and disparities existed but now I know that I can use my experiences and everything that I learned in classes to motivate my contribution and inspire change in my community.

Victoria was introduced to the project in her sophomore year and found connections throughout her next three years during which she engaged in multiple community-engaged learning assignments and collaborative undergraduate research, which culminated in a presentation at a prestigious national conference and a peer-reviewed publication. In the fall of 2020, Victoria was in a data visualization class taught by a professor in the Art department, where she was invited to participate in a community-engaged learning project, transcribing deeds. The next spring, in her economics class—held online during the pandemic—she encountered the work on covenants again when the class partnered with Ramsey County Office of Community & Economic Development. Victoria learned more about how the effort to map covenants informs local policy on everything from housing to incarceration.

Victoria built on these experiences when she undertook collaborative undergraduate research through the university’s Summer Scholars program. Together with a professor and student peer in economics, she partnered with teams from history, sociology, and public health and worked with community organizations, like District 10 Como Community Council, to develop an interdisciplinary and community-engaged research agenda. That fall, she took a course titled “The Economics of Race & Gender: Discrimination and Disparities,” deepening her knowledge of the theoretical underpinnings of housing discrimination. She went on to take a leadership role as a teaching assistant for data visualization and worked to introduce younger students to the project. All the while, Victoria was working on her own research and writing up her findings on racial segregation, which she presented at the Association for Public Policy and Management annual conference in Washington, DC.

Victoria’s experiences demonstrated much that has made our project successful and impactful. She reflected at a team meeting:

This experience really helped me to stay connected during the pandemic. This helped me apply what I learned in classes and shaped my career paths and goals. Now I’m thinking about doing something related to policy work—I want to give life to numbers because the numbers are people and lives. Finding ways to use data to create an actual impact on our communities here and anywhere else is exciting.

Victoria’s triple major already enmeshed her interdisciplinary humanities and social science ways of thinking. She carried those disciplinary foci into her collaborative research projects. While she was using census data to understand how children raised in the Como Park neighborhood—a neighborhood interesting because half is completely covered by covenants and the other half is not—improved their economic position over time, Neiwert’s history team was conducting oral history interviews with long-time residents of the neighborhood to understand how they made sense of the presence of racial covenants in their neighborhood’s past. At the end of the summer, our collective research findings offered the neighborhood a way to learn about its past and present. We shared our research findings with them by sending out students to community gatherings and creating storymaps and brochures for their neighborhood website. In November 2024, as a culmination of her work, Victoria will travel to Rome with West and Urbiank Lesch to accept the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities’ Uniservitate Global Service-Learning Award for the WTDN project.

Quantitative evidence: Survey data

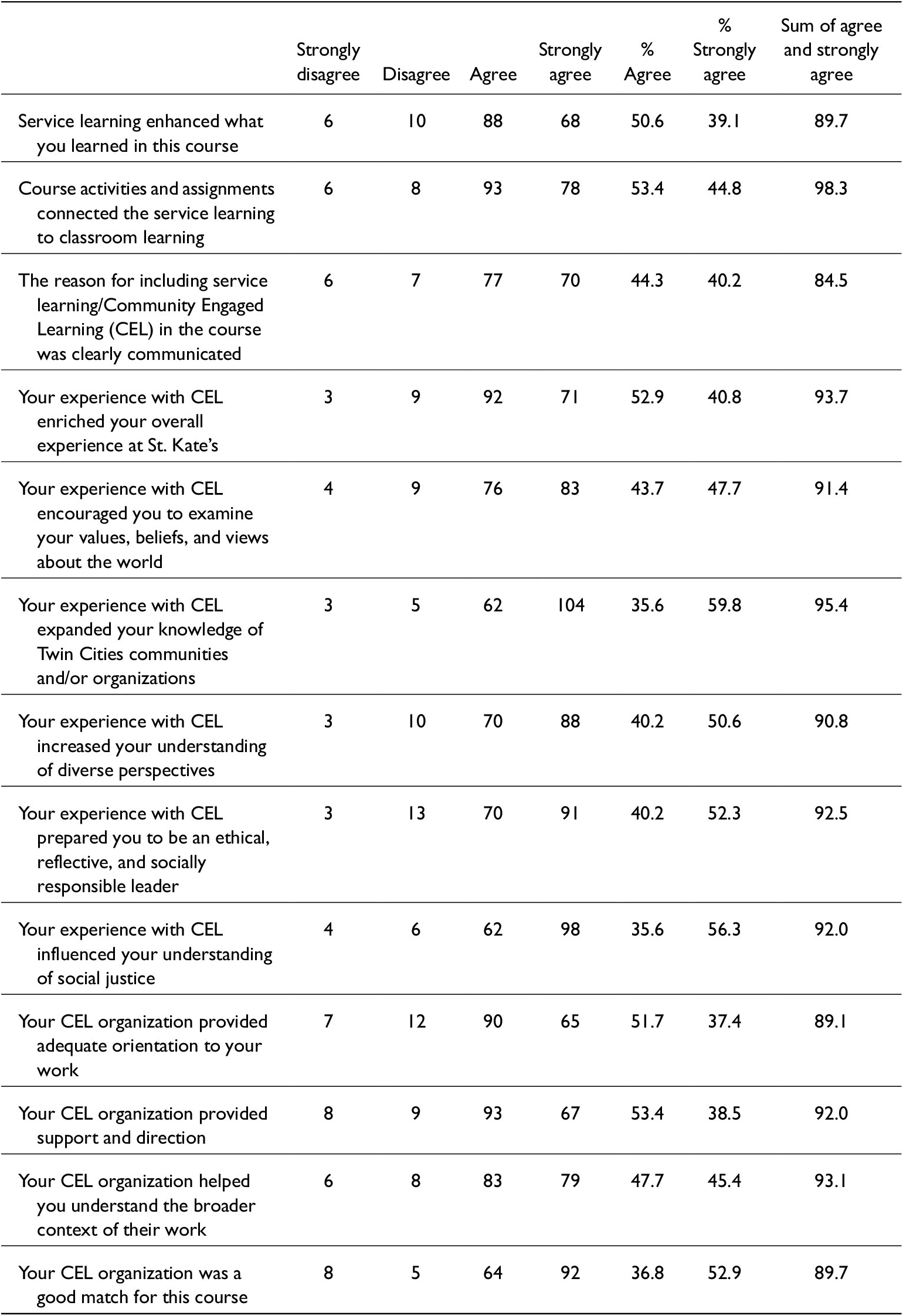

In addition to anecdotal evidence, quantitative evidence from student surveys shows the project’s impact. CWL collected survey data for 37 of the 90 classes that transcribed deeds between 2018 and 2024.Footnote 10 Table 1 provides summary statistics. The survey data show that students view experiential learning as impactful to their understanding of place and social justice. They felt strongly that the experiential learning prepared them to be an ethical, reflective, and socially responsible leader and increased their understanding of diverse perspectives.

Box 1. Student quotes from open-ended survey question

-

- Participating in the project of Mapping Prejudices has been a very grounding experience. It has helped to build upon my already forming understanding about the structural racism that people of color, especially Black and Indigenous people, have experienced throughout the history of the United States.

-

- Doing this service learning project opened my eyes to how intense segregation is/was. I never knew how segregated or racist different neighborhoods were according to where they are located.

-

- So, what Mapping Prejudice was to me was a realization that this was happening EVERYWHERE. It wasn’t a few houses here and there, it was entire neighborhoods. Legal racism, here in the land that was supposed to be “safe” for people of color migrating from the south. And, as I’m familiar with many of these neighborhoods, I can see clearly how these segregations still exist, even after these clauses were made illegal.

-

- Having the opportunity to take part in the Mapping Prejudice Project was an eye-opening experience that altered the way I think about the city that I was born and raised in.

Table 1. Student survey data

Note: Total survey responses: 174; percentage of WTDN students who completed the surveys: 11.68.

A full 98.3% of respondents answered either agree or strongly agree with the statement, “course activities and assignments connected the service learning to classroom learning”; in addition; well over 90% answered affirmatively regarding how the experience enriched their overall experience at the university, expanded their knowledge of the community, and helped them understand the broader context of what they were learning. Illustrative student comments provide context for these responses. One student explains that the experiential learning felt like it drove home deeper motivations for learning writing: “This really enriched my educational experience. I think it is important to learn about something that we may not have had access to otherwise. That’s what education is all about, after all.”

Open-ended questions show that students found the project to be eye-opening writing: “I certainly learned a lot more about the Twin Cities, things that may otherwise have been hidden from me. It actually challenged my worldview in a way, especially the way I view the places where I live and work.” Students also saw connections between experiential learning and their educational and career paths: “I believe it helped me grow in my understanding of the world, which will surely help me professionally in the future.”

There was one survey question that related (indirectly) to racial justice. When asked about whether the experience increased their understanding of diverse perspectives, 40.2% said they agreed and 50.6% said they strongly agreed. Less than 10% disagreed with this statement. In the open-ended responses, students often highlighted themes of racial awareness. Box 1 provides some examples of how students from one class (History of U.S. Women since 1920, taught in spring 2018) describe the impact.

Conclusion

WTDN’s successes include integrating the project into the curriculum at multiple levels—starting by introducing students to the work in our first-year seminar—as well as providing opportunities for student–faculty research collaborations that resulted in national presentations, peer-reviewed articles, and an international award for outstanding community engagement. The project’s challenges include navigating public humanities work in a virtual format—a necessity as the project spanned the COVID-19 epidemic but also as our university’s College for Adults moved fully online post-COVID-19—as well as tackling issues specific to racial justice in diverse environments where participants come to the work with a wide variety of lived experiences.

What started as an effort to bring the MPP to Ramsey County has turned into a signature part of St. Kate’s curricular array. Each fall, past student researchers present to the first-year seminar classes working with WTDN, and a new group of students is invited to participate. This public humanities work spans across our schools and colleges and St. Kate’s, which encourages us to live out our social justice mission in new ways. The project has created opportunities that allow for interdisciplinary research, helped students connect their learning to their community, invited students to participate in multiple disciplinary arenas, including the public humanities, and asked faculty and staff to imagine scholarship that looked beyond the academy. Most importantly, this work has more deeply connected us to the community in which we work, helping us to become better dear neighbors.

Author contribution

Writing - original draft: D.U.L., K.W., R.A.N.

Acknowledgments

The Welcoming the Dear Neighbor? project is an interdisciplinary collaboration that has benefited greatly from a list of faculty, students, and staff too long to include here. The authors are grateful for the support of the Sister Mona Riley Endowed Professorship in the Humanities (Neiwert) and the Endowed Professorship in the Sciences (West).

Funding statement

This work was funded by St. Catherine University through the Office of Scholarly Engagement, the Sr. Mona Riley Endowed Professorship in the Humanities, and the Endowed Professorship in the Social Sciences.