1. Some Laws Should Not Exist

On a hot day in Tucson, Arizona, Alex crossed 1st Avenue mid-block and was stopped by police officers for jaywalking. When asked why he crossed, genuinely puzzled, he replied “To get to the other side?” He had not realized that crossing outside a designated corner was a legal violation. This is an example of a law that, being rarely followed and seldom enforced, one might say, should not exist. Others include: Michigan’s misdemeanor for the use of indecent language in the presence of women and children,Footnote 1 anti-sodomy laws in Texas,Footnote 2 and stringent health codes for New York City restaurants.Footnote 3

Enforcing laws that should not exist may sometimes yield funny stories, but often leads to terrifying outcomes. For example, in the mid-2000s, police officers in Shreveport, Louisiana selectively applied a largely ignored ban on sagging pants, leading to 96% of 726 arrests targeting Black men. Similarly, in 2022, the Pima County Attorney invoked a dormant 1864 statute to prosecute those who provided or facilitated abortions.Footnote 4 Call legal inflation the phenomenon of the persistence of laws that should not exist (because they are seldom observed and inconsistently enforced).

This paper offers a novel conceptualization of legal inflation and explores ways to address the resulting issues. I will argue that there is a relation between legal inflation and law evasion: the more laws that should not exist, the less legal compliance. The central challenge is identifying which laws generate inflation; call them defective laws. Liberal democracies mostly use deliberative processes to legislate. However, deliberation is unlikely to address legal inflation. I argue that widespread law evasion is a signal indicating that some laws should not exist. Liberal democracies can address this problem using a rule of obsolescence (Hart 1961: 103) that removes the laws that create legal inflation.

The next section provides a conceptualization of legal inflation and argues that, to combat it, one must identify the (defective) laws that cause this phenomenon. However, this is not an easy task. Section 3 casts doubt on whether democratic deliberation can effectively identify these laws. Section 4 invites us to consider an experimental method to distinguish inflationary laws: widespread law evasion (understood as widespread non-compliance and inconsistent enforcement) should be understood as social feedback indicating laws that should not exist. The fifth section encourages rethinking H.L.A. Hart’s (Reference Hart1961) rule of obsolescence to remove inflationary laws avoiding the problems of deliberation and protecting the legal system. Section 6 examines the shortcoming of using this rule as a complement to deliberation. I conclude that, if we rethink widespread legal evasion as feedback on legal inflation, citizens are more likely to live by the laws they truly want to follow.

2. Legal Inflation

2.1 A distinct concept

In economics, inflation refers to the general increase in prices over time, which is often caused by an excess supply of money in the economy. The concept captures the relationship between prices and purchasing power: as prices rise, the purchasing power of money decreases. When there is inflation, a buyer cannot purchase the same quantity of goods with the same amount of money as before. Put simply, when there is more money in circulation, the value of money tends to decrease. Similarly, I use the term legal inflation to describe the phenomenon of the “increase” of statutory lawsFootnote 5 over time, which often leads to a decrease in law compliance. The more laws there are in excess, the more compliance and enforcement tend to decrease. Put simply, the more laws there are, the less people tend to obey them.

This is certainly not the first attempt to theorize about an excess of laws, still, the phenomenon remains largely understudied. For example, Montesquieu (1989 [1748]: Chapter XXIX) claims that his goal is to demonstrate that legislators must be moderate. More recently, some legal scholars (mostly from former Soviet countries) talk about legislative inflation to evoke the phenomenon of an excess of legislation that undermines the efficiency of laws (Eng Reference Eng and Wintgens2002; Sulmane Reference Sulmane2011; Jonski and Rogowski Reference Jonski and Rogowski2022).Footnote 6 Similarly, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) uses the term regulatory inflation to describe excessive regulation, especially for business. Political philosophers have studied similar phenomena. Joel Feinberg (Reference Feinberg1984) inquires about the moral limits of criminal law, John Hasnas (Reference Hasnas2006) deals with excessive regulations of companies, and Douglas Husak (Reference Husak2008) warns us about the excess of enforcement in the USA.

With the term legal inflation, I intend to grasp a related but different phenomenon, which has two distinctive features. First, legal inflation is a particular kind of overregulation: the proliferation of laws that are rarely observed and inconsistently enforced. Such laws are metaphorically “in excess”. This differs from the standard account of overregulation, which emphasizes the enforcement of too many laws that tends to lead to overcriminalization (Husak Reference Husak2008). In contrast, legal inflation directs attention to laws that persist despite not being enforced or observed. To my knowledge, this specific phenomenon remains underexplored. Second, while philosophers have thought about an “excess” of laws from a particular moral standpoint, legal inflation identifies this “excess” of legislation from the nature of law; i.e. I intend to explore the limits of laws qua laws. The idea of legal inflation thus remains neutral regarding moral theories.

Claiming that there are laws “in excess” assumes that there is, at least hypothetically, a correct set of laws for a particular society.Footnote 7 David Estlund (Reference Estlund2007) emphasizes the democratic tendency to yield correct laws, which are those generally obeyed voluntarily (as opposed to being obeyed out of fear of punishment) and for which the few violations are enforced. Building on this framework, I define a correct set of laws as a set of laws that generates marginal non-compliance and consistent enforcement (i.e. the law is applied predictably and violations tend to be sanctioned). For our purposes, “correct” lacks a moral connotation – e.g. just or morally desirable. Call L E a correct set of laws that grounds a legal equilibrium: almost all the members of a society voluntarily comply with L E, while the marginal violations tend to be sanctioned.

Even if in practice this assumption might be controversial, as a hypothesis, it is not unreasonable. In fact, similar assumptions can be found in other theories. Hart holds that the minimal necessary and sufficient conditions of a legal system are law “must be generally obeyed, and … rules of recognition … must be effectively accepted … by its officials” (Hart Reference Hart1961: 116). John Austin (Reference Austin1832) assumes general obedience implies the existence of a sovereign. John Rawls’s (Reference Rawls1971) famously assumes full compliance to theorize about justice. Jim Leitzel holds that widespread compliance is the goal of every law and policy (Reference Leitzel2003: 13). If one accepts those assumptions, there is no reason not to accept the assumption of a legal equilibrium. Perhaps only a committed anarchist would deny the hypothetical existence of a legal equilibrium.

Yet, even if one accepts the assumption of a hypothetical legal equilibrium, one cannot assume that it is easily reached in practice. Some might argue that, even if it theoretically exists, it might be impossible to identify what laws are part of a correct set of laws and which ones are not. The framework of legal inflation may offer guidance for approaching this legal equilibrium in practice.

2.2 Defective laws

Defective laws may be defined as those that produce legal inflation. By assumption, they are the opposite of correct laws. What are their characteristics?

Legal theorists disagree about many things, but most converge on the idea that an essential feature of the law is that it grounds general obedience. John Austin, for instance, emphasizes that an imperfect law, “a law which wants a sanction, and which, therefore, is not binding” (Reference Austin1832: I.23), is not properly a law. Hart (1961: 117–123) argues that systematic disobedience is the main pathology of legal systems. Lon Fuller holds that “it may not be impossible for a man to obey a rule that is disregarded by those charged with its administration, but at some point, obedience becomes futile” (Reference Fuller1969: 39). Joel Feinberg claims that “sometimes the state goes on record through its statutes, in a way that might well please a conscientious citizen in whose name it speaks, but then through official evasion and unreliable enforcement, gives rise to doubts that the law means what it says” (Reference Feinberg1965: 407). Scott Shapiro even states that “all legal philosophers agree that legal systems exist only if they are generally efficacious, that is, they are normally obeyed” (Reference Shapiro2013: 202).

These converging voices provide strong reasons to believe that a good way to identify laws that should not exist is to identify laws that people tend to disobey and enforcers tend to neglect, laws that seem to exist only abstractly. Call them …

Defective laws: statutory laws that exhibit (i) widespread non-compliance and (ii) inconsistent enforcement (including selective enforcement, sporadic application or utter neglect).

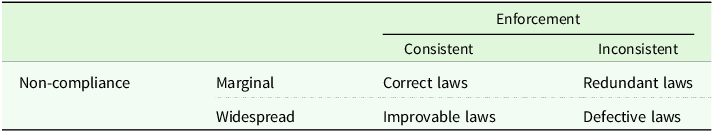

Defective laws must be distinguished from other types of laws based on two dimensions: degree of non-compliance (marginal or widespread) and enforcement patterns (consistent or inconsistent).Footnote 8 Table 1 classifies laws along these two dimensions.

Table 1. Categories of law according to non-compliance and enforcement

This paper focuses on defective laws due to their connection to legal inflation and the distinct challenges it poses. Before examining those laws in detail, I briefly outline the remaining categories to clarify how they differ from defective laws.Footnote 9

Redundant laws are those that exhibit marginal non-compliance (i.e. widespread compliance) but inconsistent enforcement (e.g. selective enforcement, sporadic application or utter neglect). When people comply with the laws in the absence of enforcement, such laws might be considered redundant. It seems unnecessary to keep laws mandating behaviours that people routinely follow, endorse and hardly breach. Curious examples include Idaho’s ban on giving alcohol to moose, prohibition of licking toads in California, or Alabama’s laws against making people laugh in church with fake moustaches. Redundant laws might have once been necessary, but appear rather dispensable to present sensitivities. Despite other problems that they may generate, their high levels of compliance prevent them from contributing to legal inflation, understood as a decline in legal compliance.

In the case of improvable laws, widespread non-compliance contrasts with consistent enforcement, a pattern that arises when violations escape law enforcement’s notice. Since non-compliance tends to be hidden, one might infer that rule-breakers acknowledge that the law is binding. These laws can be improved, as they primarily expose reporting incentive issues rather than fundamental opposition to the law.Footnote 10 Examples include laws against sexual violence or domestic violence. As surveys show, most sexual violence cases never reach courts, while reported cases tend to be prosecuted, investigated and sanctioned (Bureau of Justice Statistics 2024). In these cases, the law leads to widespread non-compliance yet shows consistent enforcement. The primary concern thus lies with victims’ reasons for not reporting. The secrecy of the non-compliance that occurs in the case of improvable laws creates a crucial distinction from defective laws, where non-compliance occurs publicly or is at least widely acknowledged. The visible defiance resulting from defective laws tends to erode general expectations about legal compliance, ultimately reducing overall obedience and fuelling legal inflation. In contrast, improvable laws rarely contribute to legal inflation so long as public enforcement remains consistent.

As with correct laws, whether a law is considered redundant, improvable or defective is independent of its moral desirability. Laws that are deemed just or unjust, moral or immoral, may belong to any of the four categories. If just laws are defective, however, they are unlikely to achieve their goals, as they fail to achieve compliance and consistent enforcement. Defective just laws may look good on paper but, in practical terms, they do not make societies more just. In the rest of this paper, I will only analyse the particularities of defective laws, the problems that they generate, and the case for their elimination.

2.3 The problems of legal inflation

Legal inflation poses two major risks for the legal system: arbitrariness and contagion.

Arbitrariness. Defective laws increase the possibility of abuses of power. The more defective laws there are, it is more likely that the enforcers choose what law to enforce with their limited time. Since it might not be possible to enforce all the laws, enforcers can choose which one of the laws they want to pay attention to. In those cases, they arbitrarily choose what law is more important to them. There is, however, an even more problematic dimension of arbitrariness. Often, these sorts of laws are created to target particular communities (Stuntz Reference Stuntz2000; Wylie et al. Reference Wylie, Milless, Sciarappo and Gantman2024). This might be the case of saggy pants in Shreveport, which justified the detention of several people that the police might have wanted to detain for other reasons (Monaghan Reference Monaghan2023: 70).

Contagion. Defective laws might trigger evasion of other laws. If people develop the habit of evading a particular law and they expect that other individuals do so as well, the norm of legal compliance (the norms that ground individual expectations that others comply with the law) is at stake (Mackie Reference Mackie and Tognato2018). At this point, the analogy with economic inflation is particularly appropriate: more laws decrease the obedience of the law. If one can violate that law, why can’t they violate other laws? Where is the limit of those laws that can be evaded systematically? More and more individuals may arbitrarily decide what laws to follow. The constant evasion of a particular law might spread to the rest of the laws. Citizens lose trust in law enforcement to impose any laws, not only those that are defective. Defective laws threaten to undermine the respect for the legal system in general (Alatas Reference Alatas1990; Johnston Reference Johnston2005; Bicchieri Reference Bicchieri2017; Munger Reference Munger2018).

Arbitrariness and contagion constitute important threats to the integrity of legal systems. It is important thus to combat legal inflation. But, how to do so?

3. The Deliberative Moment of Legislation

In a democracy, there are two “moments” in which one might be able to identify defective laws: the deliberative moment (when representatives make the laws) and the experimental moment (when people react to the laws that they have to live by). Can the deliberative moment identify defective laws?

3.1 The epistemic virtues of deliberation

The quintessential democratic mechanism to legislate is public deliberation. Political theorists often underline the epistemic virtues of democracy (Habermas Reference Habermas1996; Fishkin and Ackerman Reference Fishkin and Ackerman2004; Estlund Reference Estlund2007; Landemore Reference Landemore2013). Estlund, for example, holds that “democratically produced laws are legitimate and authoritative because they are produced by a procedure with a tendency to make correct decisions” (Reference Estlund2007: 6). Democratic institutions take into consideration every adult voice, let people listen to others’ ideas, debate freely, change minds in light of better arguments, and reach conclusions that express the aggregation of everyone’s preference. The likely result is a correct law that legitimately integrates citizens’ desires and provides moral reasons to obey (Estlund Reference Estlund2007: 23). Theorists of democracy argue that democratic deliberation is more likely to enact correct laws than defective laws.Footnote 11

This process does not only occur once; it is iterated. Even if we don’t share Estlund’s view about the epistemic virtues of deliberation at the moment of legislation, one could agree that repeated debates about the laws might make noticeable which laws are defective. Constant debates might detect defective laws in two ways: (A) those that might have slipped into legislation due to deliberative imperfections the first time and (B) those that might ground a legal equilibrium at t 1 but not at t 2. Cases A are straightforward. It is reasonable to acknowledge that it is very difficult to identify a defective law a priori, but, if voters are attentive to how people evade this law, then legislators might repeal it in subsequent deliberations. The iterated exchange of opinions would tend to correct the mistakes that deliberation did not detect in previous rounds. Cases B are more problematic. A law might be correct in one context but become defective in the future. Still, constant deliberation can detect that the law is defective and repeal it in the same way as cases A.

Different scholars defend the epistemic virtues of democracy to varying degrees and under different conditions: from highly idealized circumstances that allow deliberation to reach the truth (Habermas Reference Habermas1996) to the empirically motivated views of democratic collective intelligence (Landemore Reference Landemore2013). Nevertheless, those who defend the epistemic virtues of deliberation tend to agree that one of the main advantages of democratic regimes is to provide the framework through which voters can yield correct laws and prevent (or rectify) defective ones. Legal inflation might be a constant fight and a complete victory might be off the table but deliberative democracy might be our best tool against it.

3.2 Deliberation falls short

Empirical evidence shows that democratic deliberation does not suffice to detect defective laws (Downs Reference Downs1957; Pincione and Teson Reference Pincione and Teson2006; Caplan Reference Caplan2007; Brennan Reference Brennan2016). Democracies show at least three problems for the identification of defective laws: voters tend to be uninformed and partisan, and the moral vocabulary tends to be insufficient to grasp social transformations. I will not argue that democratic deliberation is harmful or useless, but only that it is unlikely to (timely) detect defective laws.

Rational Ignorance. Voters are seldom informed about the laws that they choose. This is not an anomaly or an intentional result, but a rational response to the incentives in electoral democracies. Some economists stress the rationality of remaining uninformed: “if time is money, acquiring political information takes time, and the expected personal benefit of voting is roughly zero; a rational, selfish individual chooses to be ignorant” (Caplan Reference Caplan2007: 94). Voters are not likely to pay the cost of acquiring information or the required skills to correctly understand laws and policies since their vote is unlikely to define the election. Put simply, the cost is bigger than the reward. If voters are uninformed about the laws in place and the actual consequences of laws, they will not be able to detect if they are correct or defective. Electoral democracy thus fails to set the proper incentives for encouraging voters to become informed in order to choose the correct legislator. Representatives are elected not because of the correctness of the laws that they promise to enact, but because of what they say. Politicians have incentives to promise and legislate whatever uninformed voters say that they prefer, even if their laws don’t yield the results that voters actually prefer.

Partisanship. Democratic deliberation renders voters partisan. In a diverse society, democracy does not lead to a rational and reasonable debate in which people identify the quality of the laws according to careful examinations of evidence and the strength of arguments. Conversely, people tend to identify opposing views as wrongful without considering the merits of their arguments. Jason Brennan observes that “deliberation … frequently exacerbates our biases and leads to greater conflict” (Reference Brennan2016: 67). Since individuals have a tendency to avoid conflict, they are led to talk and befriend people with similar ideas. They don’t engage with different points of view, which tends to increase the belief that what one believes is correct and opposing views are wrong and corrupt (Talisse Reference Talisse2019). When people don’t engage in argumentation, they fail to appropriately assess the laws. Voters simply consider the laws that they support correct and those that they disagree with wrongful. And those laws that are considered wrongful might lead to constant evasion. Therefore, it is likely that voters simply identify defective laws with laws from the “other side”.

Owl of Minerva (OM). One problematic aspect of deliberation that democratic theorists seldom address is the insufficiency of moral vocabulary to grasp moral change. Hegel (Reference Hegel1942) famously claims that actions precede the linguistic understanding of them. He evokes the image of the Owl of Minerva to illustrate the view that social and moral changes take place before individuals have the conceptual tools to grasp them (Hegel Reference Hegel1942: 13). People develop the appropriate vocabulary as they go. Without the adequate conceptual machinery, the change, even if in place, often remains partially unnoticed. For example, the term “state” was fundamental to understanding the relationship of representation between rulers and the governed. During the late Middle Ages, rulers imperfectly represented their subjects, but it was still unclear whether the sovereign was the ruler or the people. It was not until Machiavelli employed the term stato to refer to the required social conditions to preserve the status of the monarch that philosophers were able to conceive of the sovereign as a fictional person who represents the subjects through the ruler (Skinner Reference Skinner, Kalmo and Skinner2010). Call this problem the Owl of Minerva problem (OM). I argue that this is the most significant obstacle to deliberation in identifying defective laws.

These three problems might explain why emphasizing deliberation as the appropriate device for legislation might not lead to a legal equilibrium. In fact, democratic deliberation might fuel up legal inflation. Uninformed voters tend to applaud an array of contradictory laws. Partisan voters fail to agree on what laws they want and might take turns to legislate against each other. OM makes us understand why voters applaud legislation that they don’t follow in their everyday lives. We can thus expect that democratic deliberation fails to identify defective laws.

4. The Experimental Moment: Law Evasion

4.1 The experimentalist account of democracy

Elizabeth Anderson’s (Reference Anderson2006) experimentalist account of democracy emphasizes the ways in which citizens express their dissent to laws not only at the time of legislation but on the street once a law is in place. Yet, dissent comes in many forms. The classic channels of the expression of dissent are protests and civil disobedience.

Some expressions of dissent rely also on deliberation. Through protests, for example, people advance their justified opposition to particular laws or policies. Even though public protests contain important information about the law, they might exhibit similar problems of deliberation (most likely, rational ignorance, and partisanship) and are thus unlikely to help in the identification of defective laws. Civil (and uncivil) disobedience also expresses dissent against the laws (Lefkowitz Reference Lefkowitz2007; Brownlee Reference Brownlee2012) and shapes the behaviour of rulers (Pettit Reference Pettit2023). However, the communicative goals of civil disobedience depend on the awareness of breaking the rule for justified reasons. Giving reasons for one’s disobedience might still be subject to the problems of deliberation, inasmuch as some people might be uninformed about it, it might be viewed as part of a particular ideology, and it might be an inchoate justification that not everyone shared. Even if civil (and uncivil) disobedience is important feedback about the laws, as a justified action, it still falls prey to some of the problems of deliberation. This is not to claim that these forms of dissent are not important, but only to claim that they might present the same problems as deliberation regarding the identification of defective laws.

Are there non-deliberative mechanisms to gather information about the laws?

If there were a mechanism to capture information about what people do, rather than what they say, we could take a step forward in detecting defective laws. Instead of predicting which laws will be disobeyed, we should observe which ones are actually disobeyed. Viewing democracy through an experimentalist lens suggests alternative forms of feedback on laws, which, from this perspective, can be seen as legal experiments awaiting results.

4.2 Widespread law evasion as a marker of revealed social preferences

Jim Leitzel’s (Reference Leitzel2003) opens the door to think about a different kind of civil disobedience, one that most of the time lacks political or legal justification or even intention: law evasion (Leitzel Reference Leitzel2003: 3). Most of the time disobedience to the law lacks a clear purpose, and yet it might have the same effect as civil disobedience: someone showing her preference not to obey the law and willing to pay the price for it – if caught.Footnote 12 Law evasion might then be a way of dissent that flies under the radar. Drawing upon Leitzel’s analytical framework, I refer to widespread law evasion as the co-occurrence of widespread non-compliance and inconsistent enforcement. If civil disobedience is correctly acknowledged as a form of feedback to the laws, why isn’t widespread law evasion?

Admittedly, non-compliance should not automatically be interpreted as feedback about laws. Some level of disobedience always exists. Marginal violations provide little information about a law’s quality, as they occur even with correct laws. Only widespread non-compliance potentially signals substantive issues with the law. As said, these issues might refer to the lack of incentives to report (improvable laws), yet the marker becomes stronger when combined with inconsistent enforcement. This means that defective laws may offer genuine feedback about the content of the law.

A significant problem however is that widespread law evasion lacks clear intentions – as opposed to civil disobedience. There might be different reasons why a law l i generates widespread law evasion: individuals may violate laws because others disregard them (Bicchieri and Xiao Reference Bicchieri and Xiao2009), due to moral objections (Zuccarelli Reference Zuccarelli2024), or because the law creates practical burdens (Munger Reference Munger2018). If different people violate the law for different reasons, how can we consider their actions to be information about the laws?

Actions often reveal more about preferences than words. When we focus on what people do instead of what they say, we may capture their revealed preferences (Samuelson Reference Samuelson1948). In the same way that “revealed preference analysis is built upon the observation that a utility maximizer who purchases a consumption bundle x when bundle y was cheaper is revealing that x is preferred to y (i.e. x yields more utility than y )” (Dziewulskia et al. Reference Dziewulskia, Lanierb and Quah2024: 1), an analysis of revealed preferences within the legal context pays attention to what people do when they don’t comply with the law despite the threat of punishment. When people claim to support banning X-ing yet systematically engage in X-ing, their actions should count more than their words as information about their preferences. This suggests a sort of revealed social preference for violating rather than obeying the law under given conditions. Although widespread non-compliance alone cannot disclose individual reasons for disobedience, it strongly indicates a revealed social preference that the law should not exist. In this case, the repetitive violation of the law and its inconsistent enforcement is the way in which people express in actions dissent to some law that they say they support.Footnote 13

4.3 Forms of widespread law evasion

Widespread law evasion can take many forms. A social norm for speeding that normalizes speeding on the highway represents a widespread evasion of the law. Other examples are systematic bribes for bureaucrats, black markets and organized crime. Different moral judgments can be made about individuals who take part in the different forms of widespread law evasion. We would seldom compare driving 10 mph over the speed limit on I-5 to smuggling human beings over the border or to giving money to police officers to look the other way. At this point, it is important to differentiate between two levels of analysis. At the individual level, moderate speeding is not particularly morally troublesome, while smuggling human beings is. Philosophical analyses of law avoidance tend to remain at the individual level and inquire about what that says about moral agents. However, in the aggregate, at the social level, widespread law evasion requires a different analysis because it might provide information about the laws. In the following, I will briefly restate three recent analyses that suggest that, in the aggregate, widespread law evasion contains information about the law.

As said, Leitzel opens the door to consider widespread rule evasion as information about the quality of the laws and reasons for reform. He offers manifold examples to illustrate his thesis: from the rise of illegal abortion before Roe v. Wade to voluntary surrender by hundreds of marijuana users in Stockport, England in 2002. Yet, for Leitzel (Reference Leitzel2003: 23–27), the primary illustration of this phenomenon is price controls: price ceilings and price floors. Price ceilings (as long as they are above market equilibrium) tend to lead to undersupply of goods. As a reaction to this, unsatisfied customers and sellers figure out different ways to evade those controls.Footnote 14 A frequent unintended result of price controls are black markets in which goods are available at a higher price. High prices go against the purpose of the law and yet help individuals acquire the goods that are undersupplied. Price floors provide other examples. Leitzel recalls the example of a policy in “transitional Russia, which imposed a minimum price on imports to protect the domestic vodka industry … To elude the controls, some shopkeepers adopted ‘buy one, get one free’ promotions for foreign-produced vodka” (Reference Leitzel2003: 25). Through these and various other cases, Leitzel exemplifies different ways to evade the law that, without the rulebreakers’ intentions, indicate that the laws must change.

Another example of widespread law evasion is human smugglers and illegal abortions. Gloria Zuccarelli (Reference Zuccarelli2024) defends the permissibility of violating rules that lead to unjust results, especially on two fronts: backstreet abortions and human smuggling. Her thesis is that “smugglers and abortionists as examples of citizens fulfilling a duty to compensate for, or redress, an injustice. Indeed, smuggling and backstreet abortion are necessary where there is a systemic violation of a human right (to find refuge and to safely interrupt an unwanted pregnancy) by the states …” (Zuccarelli Reference Zuccarelli2024: 268). Zuccarelli’s argument is different from the one presented here. She focuses on the injustice of the law, rather than on the defectiveness of the law. Her argument aims for a morally stronger conclusion than mine. However, often widespread law evasion comes from a profound (yet seldom justified) sentiment that the law is unjust. Her argument is different on another front. She aims to determine the permissibility of those lawbreakers, hence it works at the individual level while, as said, my thesis aims to make judgements at the social level.

Now, when law enforcers constantly violate the law and citizens approve their actions, the marker of defective laws becomes even stronger: it is not only citizens who reveal a preference against the law but also public officials. This occurs in cases of widespread corruption. Building on Emanuela Ceva and Maria Paola Ferreti’s (Reference Ceva and Ferretti2021) idea of the heuristic dimension of some kinds of corruption, Mario Juarez-Garcia (Reference Juarez-Garcia2025) invites us to understand widespread corruption as information about the law. Citizens constantly bribing law enforcers and law enforcers constantly accepting bribes indicate, at least prima facie, that the law is defective. Juarez-Garcia does not deny that some cases of corruption result from morally deviant public officials, but when widespread corruption presents certain characteristics, there are strong reasons to believe that both citizens and public officials approve of the constant violation of the law (Juarez-Garcia Reference Juarez-Garcia2025: 979–980). This can lead to the problem of contagion creating an expectation in the society that any law can be violated and any law enforcer is corrupt. When that happens, the rule of law deteriorates quickly, a process of institutional corruption starts (Miller Reference Miller2017).

Black markets, backstreet abortion, human smuggling and widespread corruption are just some of the forms that widespread law evasion can take. At the individual level, some might be more morally permissible than others; we might agree with some of these forms and disagree with others. And yet, at the social level, with Leitzel (Reference Leitzel2003), Zuccarelli (Reference Zuccarelli2024) and Juarez-Garcia (Reference Juarez-Garcia2025), I argue that when these violations are widespread in a population, they must be considered information for changing the law – even if no one aims to do so. Leitzel formulates this point more eloquently: “in a curious twist of Adam Smith’s invisible hand, lawbreakers can improve society, even if serving the social good is the furthest thing from their minds” (Reference Leitzel2003: 3).

5. The Rule of Obsolescence

Even if widespread law evasion can be understood as information to remove defective laws and fight legal inflation, through what channels can this information modify legislation?

The problems of deliberation make it unlikely that, even with this information, lawmakers agree on removing defective laws. A non-deliberative mechanism to translate widespread law evasion into legislation might avoid these problems. A rule of obsolescence might serve this purpose.

5.1 The resurrection of the rule of obsolescence

In Roman Law, desuetudo referred to the view that a statute could lose its force through persistent disuse: widespread noncompliance could render a law obsolete and thus derogated.Footnote 15 Hart recasts this principle as a rule of obsolescence, which is the “provision … that no rule is to count as a rule of the system if it has long ceased to be efficacious [i.e., obeyed more often than not]” (1961: 103). A new version of the rule of obsolescence might require tracking evasion patterns to remove unobserved and unenforced laws, thereby tempering legal inflation.

The rule of obsolescence as applied in the case of old laws would remove laws such as the 1864 prohibition of abortion in the territory of Arizona before it was a state, but what about recent laws that trigger widespread law evasion? We should think about obsolescence as a feature of any law in place that leads to widespread law evasion regardless of how long it has been on the books. If l 1 was enacted in 1913 and l 2 in 2013 and both lead to widespread law evasion today, l 1 and l 2 are equally obsolete.

How would the rule of obsolescence look in practice? Consider society Z with a set of laws L Z containing l 1, l 2, l 3 and the rule of obsolescence R. If it is detected that in general the expectations of the citizens is that l 3 is constantly evaded, R would activate a mechanism that removes l 3.

It is important to precise two problematic aspects of the general form of the rule of obsolescence: (P1) widespread law evasion, as said, can take many forms, and (P2) how is it possible to detect different types of widespread law evasion? To deal with P1, legislators must think about each particular kind of law evasion and ways in which it can be detected, which may go from the observation that no one follows the law (e.g. jaywalking in Manhattan) to more complicated metrics to capture the law evasion (e.g. the number and frequency of court cases of corruption in Chicago). The full treatment of P1 falls beyond the scope of this paper; scholars might find reasons to figure out metrics to capture frequencies of law evasion more effectively and more precisely. The response to P1 directly affects how to deal with P2.

Some kinds of law evasion are easier to capture in a metric than others. Consider the case of old laws. The fact that in society Z, law l 3 has not led to any court cases in n number of years might be a good indicator that the law is not followed (or it is trivially followed and then there is no reason for it). If in Z, the rule of obsolescence states that a law that has not led to court cases in p number of years must be removed, and n ≥ p, then l 3 is removed. This might be the easiest case. The rule of obsolescence is likely to remove many laws that should have been removed before.

Now, consider the case of political corruption. In Z, l 2 constantly leads citizens to bribe police officers, yet a certain number m of corruption cases end up in trials. If in Z, the rule of obsolescence states that a certain number q of court cases of corruption regarding the enforcement of l i must be taken as evidence that the rule is obsolete, and m ≥ q, then the rule of obsolescence removes l 2. Cases of corruption remain difficult to detect due to the secretive nature of the act, nonetheless it tends to be the case that, as long as most people condemn corruption in general (even if not in the case of some laws), at least some cases of corruption will end up in court. The necessary number to activate the rule of obsolescence (p and q in these hypothetical examples) would vary depending on the type of law evasion it tries to capture and on how sensitive a society wants to be to law evasion.Footnote 16 As a speculation, in several cases, the number of court trials can be used as a proxy to measure widespread law evasion.

5.2 The rule of obsolescence protects democratic institutions

As said, legal inflation poses at least two important risks for legal systems: arbitrariness and contagion. The rule of obsolescence aims to mitigate these issues.

Legal inflation might lead to arbitrariness. When there are defective laws, enforcers can arbitrarily choose which one to enforce. The rule of obsolescence would temper the abuse of law by removing the justified reasons available to detain someone. The ban on saggy pants in Shreveport, the Prohibition laws enforced selectively on particular groups (Stuntz Reference Stuntz2000: 1875–1876), and ARS 13-3603 in Arizona are clear examples of how laws are used arbitrarily with political or racial purposes. The rule of obsolescence might constitute an important role in reinforcing the mechanisms that protect citizens against abuses of law enforcement.

The rule of obsolescence is however not necessary or sufficient to solve arbitrariness, even if it offers quicker channels to deal with those issues, especially in democracies that are prone to the problems of deliberation. This rule, however, is particularly well placed to deal with contagion.

The problem of contagion might be the most worrisome result of legal inflation. It threatens the very basis of democratic institutions by undermining general obedience and hence political stability. The rule of obsolescence aims to tackle defective laws that damage compliance before general disobedience spreads to the rest of the legal system. Its goal is to identify those laws that are defective before non-compliance and inconsistent enforcement become a norm that spreads to the rest of the set of laws. By isolating defective laws, the rule of obsolescence protects the norm of legal compliance, which is the main difference between modern and premodern states (North et al. Reference North, Wallis and Weingast2009).

5.3 The rule of obsolescence corrects democratic deliberation

As said, democratic deliberation is unlikely to detect defective laws mainly because of three problems: rational ignorance, partisanship and the Owl of Minerva problem (OM). A rule of obsolescence would mitigate these deficiencies of deliberation.

Whereas in the deliberative moment voters are rationally ignorant, at the experimental moment, citizens are local experts for the sole fact of being subject to particular laws. Voters have little incentive to seek information that goes beyond the spheres of personal life due to the low likelihood that their vote is decisive and the cost of information. In their interaction with the laws, however, citizens produce information about the desirability of such laws. They experience the law and express their preferences through actions. The rule of obsolescence will try to capture local knowledge about whether people comply with the laws or not in their daily lives. As it is, there is no mechanism to capture this local knowledge. The rule of obsolescence will act as a mechanism to collect and aggregate local information spread in the system about the desirability of the law. This might be an imperfect way to do so, but it is certainly a first step to collecting the preferences of citizens outside elections. In this respect, a rule of obsolescence may be understood as a sort of revealed social choice mechanism.

Whereas at the deliberative moment, people tend to become partisan in a diverse society, at the experimental moment, people simply act. In a diverse society, there are different ideas of what constitutes a defective law. Nevertheless, beyond our views about morality and justice, a reasonable indicator that law is defective qua law (not qua requirement of justice) is that those who are subject to it don’t abide by it, and those who must enforce it inconsistently punish lawbreakers. Widespread law evasion should be understood as the expression of a revealed social preference beyond moral disagreements. A rule of obsolescence would capture this general agreement in action despite deliberative disagreement and consider that actions are at least as important to understanding social preferences as words. However, this does not mean that the rule of obsolescence would have the last say on the matter. Legislators are always capable of discussing the law again and enacting it once more. Yet, as a matter of identifying a defective law, a rule of obsolescence is likely to do a better job than democratic deliberation as it avoids partisanship.

OM might be the most difficult problem to tackle through deliberative mechanisms. Since the rule of obsolescence aims to capture social preferences through actions, it might better address this problem. When people lack concepts to understand defective laws, they will fail to identify them. Since the rule of obsolescence does not capture deliberate preferences, it does not require new concepts to capture citizens’ new sensitivities to particular situations. The rule of obsolescence aims to capture the changes that people can only intuit but still not fully conceptually grasp in the moment of widespread non-compliance. Unlike OM, the rule of obsolescence intends to come before dusk.

The rule of obsolescence hence avoids the three main problems of democratic deliberation. The goal however is not to replace deliberation, but to create a complementary mechanism to consider people’s actions (not only their words). It captures the information created in the interaction with the laws to correct those that sound good on paper but are not complied with in practice. This would bolster democratic self-governance, understood as the system of government that aims to rule following citizens’ preferences, by increasing the preferences taken into account in legislation.

6. Shortcomings of the Rule of Obsolescence

Even if a rule of obsolescence helps mitigate legal inflation, it has clear limits and may even cause problems. This rule is not (6.1) necessary or sufficient for legal equilibrium, (6.2) may hinder legal ability to anticipate problems, (6.3) might be useless in case contagion has already occurred, and (6.4) may hinder moral progress.

6.1 Nor necessary or sufficient for legal equilibrium

It is easy to understand why a set of rules L E that grounds legal equilibrium can be obtained without the rule of obsolescence: lawmakers may simply be precise enough to read social preferences and express them into laws. Theoretically, the rule of obsolescence is not necessary for legal equilibrium. However, real legislators, even when well-intentioned, often lack full information about citizens’ preferences and social environments, which makes it unlikely that they can legislate the set of laws LE. Most likely, legislators try different laws hoping that they respond to people’s needs. In current electoral democracies, elections are the main mechanism to orient legislation toward citizens’ preferences. The rule of obsolescence could operate as a correcting mechanism for legal systems, automatically flagging laws that fail to secure widespread compliance and exhibit inconsistent enforcement. These laws would be identified as candidates for legislative review and potential repeal.

Furthermore, the rule of obsolescence is not sufficient for a legal equilibrium. Fighting legal inflation might prevent the excess of laws, but it is of no help to remove defective laws when there is a legal deficit – i.e. there is a lack of correct laws. To deal with a deficit, democratic deliberation might be the best hope to find the laws that are missing from the legal equilibrium. Part of the enterprise of political philosophy can be understood as a way to provide reasons to advance legislation that is missing from L E. The goal is to justify why it is important to enact a certain law. Despite the deficiencies of deliberation, this might be the only tool we have to try laws that might be correct. Yet, even if not sufficient for legal equilibrium, the rule of obsolescence plays a role in this picture, since it works as a corrective mechanism for cases in which, once enacted, justified laws unintendedly go against the (revealed) preferences of citizens.

6.2 Future problems

The rule of obsolescence is sensitive to the correctness of current laws yet not to that of future laws. This rule will tend to hinder preventive legislation that aims to tackle future problems. Consider the following case. At t1, the current set L E grounds legal equilibrium, yet, lawmakers foresee that there is a major ecological transformation that is likely to make it the case that, at t3, the set L F grounds a future legal equilibrium. If lawmakers legislate L F at t2 to anticipate a future legal equilibrium at t3, a rule of obsolescence might indicate that some laws are defective at t2 and they would be removed. The mechanism would be correct at t2, yet the lawmakers would be correct in anticipating major changes as well. We can see how this rule creates problems for legislators who aim to anticipate future changes.

In this example, there is an important assumption: the accuracy of the prediction. If we assume that the legislators’ prediction is accurate, then the rule of obsolescence is problematic. Yet, predictions are seldom exact. Shapiro reminds us “the future is often unclear and human beings do not have the ability to consider every single contingency, it often makes sense to wait until more information is available before deciding how to respond” (Reference Shapiro2013: 199). The rule of obsolescence provides an incentive for lawmakers to have the best prediction possible and find just the right time in which law will become relevant to the new context, or else avoid legislating for the future.

6.3 When contagion happened

The rule of obsolescence cannot work in a social environment in which contagion has already happened and citizens don’t follow the norm of legal compliance anymore (Mackie Reference Mackie and Tognato2018). In such a context, citizens expect that others violate at least some laws systematically. Citizens choose what laws to abide by, and often they are not the same. The absence of the norm of legal compliance makes formal legal systems unstable (North et al. Reference North, Wallis and Weingast2009; Mungiu-Pippidi Reference Mungiu-Pippidi2015). One might not meaningfully (perhaps only metaphorically) talk about legal inflation in such contexts. In those cases, the rule of obsolescence will not address the problem of generalized legal evasion since it would be impossible to isolate defective laws and remove them to protect the rest of the set of laws. The whole set of laws might be defective by then, and stronger measures should be taken to achieve legal compliance (Johnston Reference Johnston2005).

6.4 Impeding moral progress

If one acknowledges the possibility of moral progress (Buchanan and Powell Reference Buchanan and Powell2018), one might worry that the rule of obsolescence could hinder it. Assume that legislators know that a law leads to moral progress, yet a significant number of citizens reject it. The rule of obsolescence would allow these citizens to eliminate the law through widespread disobedience and collusion with law enforcers, bypassing democratic legislative channels. One might conclude that, in those cases, the rule of obsolescence facilitates the obstruction of moral progress.

To illustrate this worry, consider the following cases. In Society Z, legislators outlaw slavery, but most citizens and law enforcers evade the law until the rule of obsolescence removes the legal prohibition, impeding the abolition of slavery. This is a morally repugnant outcome. If this example seems outdated, consider a more recent troubling case: laws against sexual violence. If in Society Z rape is illegal, but the law is routinely violated while enforcers consistently turn a blind eye, the obsolescence rule would classify this law as defective and remove it. This is another repugnant outcome. In both scenarios, the obsolescence rule seems to facilitate injustice. This is a serious concern.

However, moral progress cannot be impeded where such progress is not possible due to abhorrent social norms. Empirically, laws are unlikely to change deeply entrenched social norms. Evidence shows that laws imposing behaviours that conflict with strong social norms frequently prove ineffective in achieving its intended outcomes, and may even produce counterproductive effects (Montesquieu 1989 [1748]; Stuntz Reference Stuntz2000; Boettke et al. Reference Boettke, Coyne and Leeson2008; Bicchieri Reference Bicchieri2017). Therefore, the rule of obsolescence would not exacerbate social problems when they are deeply rooted in abhorrent social norms.

On the contrary, the rule of obsolescence may carry out modest benefits in these situations. First, it safeguards the efficiency of a legal system. When rulers insist in enforcing defective laws, they may erode public trust (Stuntz Reference Stuntz2000), provoke covert resistance (e.g. post-Civil War discriminatory laws in the American South), or, worst-case, risk the problem of contagion. In such scenarios, the rule of obsolescence prevents contagion and helps preserve compliance with functioning laws. Second, laws often create the illusion that moral progress has been achieved. Without the rule of obsolescence, people may believe that moral progress is secured simply because the law remains on the books, while social norms continue to deteriorate on the street. The rule of obsolescence serves as a safeguard against this deception. When it removes a law, it highlights that significant behavioural change cannot be imposed solely through legislation; such transformation must first take root at the level of norms (Bicchieri Reference Bicchieri2017; Mackie Reference Mackie and Tognato2018). In this way, the rule of obsolescence may reveal that the law is not enough for moral progress and that work remains to be done. Different strategies and policies might foster moral progress by aiming to change the norms through non-coercive means (Bicchieri Reference Bicchieri2017).

Third, the rule of obsolescence may, at worst, delay efforts to advance moral progress, but it does not preclude them entirely. Legislators retain the power to reenact any law removed through this mechanism. Even when citizens strategically exploit the rule to protect immoral practices, lawmakers may persistently legislate their moral convictions. This flexibility proves particularly valuable during transitional periods, when a law’s defectiveness remains uncertain due to rising – but not yet widespread – compliance levels and a decreasingly inconsistent enforcement. These are critical moments when legislation must actively shape compliance and enforcement to transform social norms and advance moral progress. In such cases, the rule of obsolescence does not permanently impede moral progress, as it does not prevent the reintroduction of removed laws.

7. Conclusion

The conceptual framework of legal inflation helps us understand various legislative problems and the risks they pose to legal systems. These issues are seldom addressed. It also encourages readers to view widespread law evasion as a source of information about the law, an angle that some scholars have recently explored (Leitzel Reference Leitzel2003; Kang Reference Kang2024; Juarez-Garcia Reference Juarez-Garcia2025). The rule of obsolescence is an imperfect mechanism to capture this information without succumbing to the problems of deliberation. I do not claim that this is the only way to gather information about society’s experience with the law, or the only means to temper legal inflation, but it is a rule that could help protect democratic institutions from the risk of arbitrariness and contagion.

And yet, what if a legal equilibrium is not what citizens want? What if what they want is justice, not general compliance? As stated before, the problem of aiming for justice without a legal equilibrium is that, even if deliberate agreement appears around a set of perfectly just laws, if these laws are defective, they would be generally evaded. Defective perfectly just laws cannot promote justice. Now, citizens might prefer to have perfectly just laws on paper, even if they are not on the streets. That is a trade-off that some people may be willing to accept. Yet, they might need to give up on their hopes of building a just society with laws that most people evade.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editor of this journal, Peter Vanderschraaf, and the anonymous reviewers whose comments significantly improved this article. Early versions of this project were presented at several venues, including the Conference on Moral Progress at the Jean Beer Blumenfeld Center for Ethics (Georgia State University), the Philosophy, Politics, and Economics Society Meeting, the Junior Fellows Conference (Institute for Human Studies) and the New Orleans Political Economy Workshop (Murphy Institute, Tulane University). I am grateful to all participants for their feedback, particularly to Jason Lee Byas, Jeff Carrol, Andrew I. Cohen, Andrew Jason Cohen, Dan Engster, Dale Jamieson, Matthew Jeffers, Joe Heath, Sam Koreman, Victor Kumar, Michele Moody-Adams, Ryan Muldoon, Kirun Sankaran, Alexander Schaefer, David Schmidtz, John Thrasher, Chad Van Schoelandt and Matt Zwolinski. I owe special thanks to Jacob Barrett and Jake Monaghan for their valuable comments on early drafts. Finally, I am especially grateful to Mike Munger, whose encouraging words and consistent support to this project convinced me that it was worth pursuing.

Mario I. Juarez-Garcia is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy and Political Economy at Tulane University. He is a faculty member of the Murphy Institute’s Center for Ethics, and a fellow at the Research Center for Corruption Studies of the University of Geneva. He is the author of Moral Institutions: An Introduction to Philosophy, Politics, and Economics (Routledge, 2025), and, with Matt Zwolinski, the editor of Arguing About Political Philosophy (Routledge, 2025). His current research project aims to develop a non-ideal theory of political corruption.